Tuning of a Viscous Inerter Damper: How to Achieve Resonant Damping Without a Damper Resonance

Abstract

1. Introduction

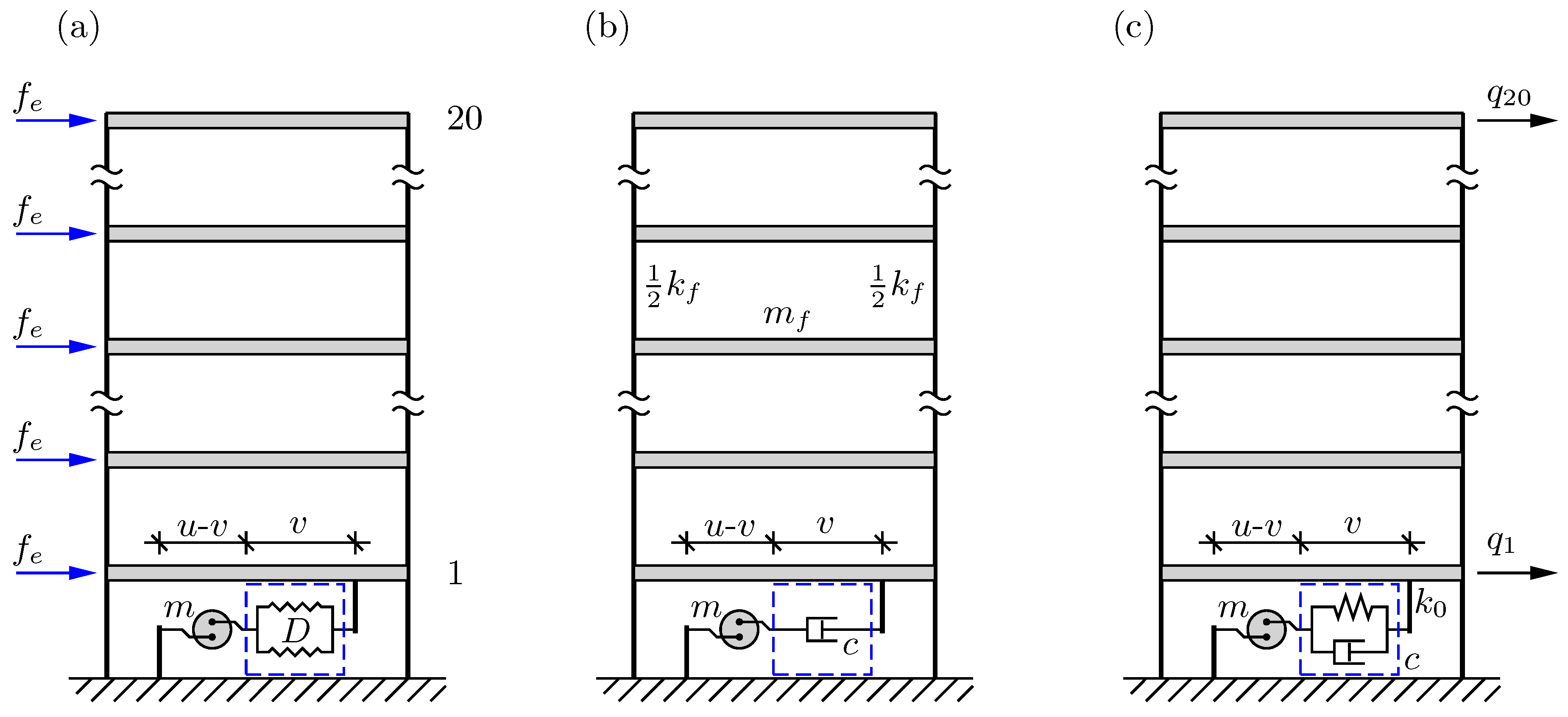

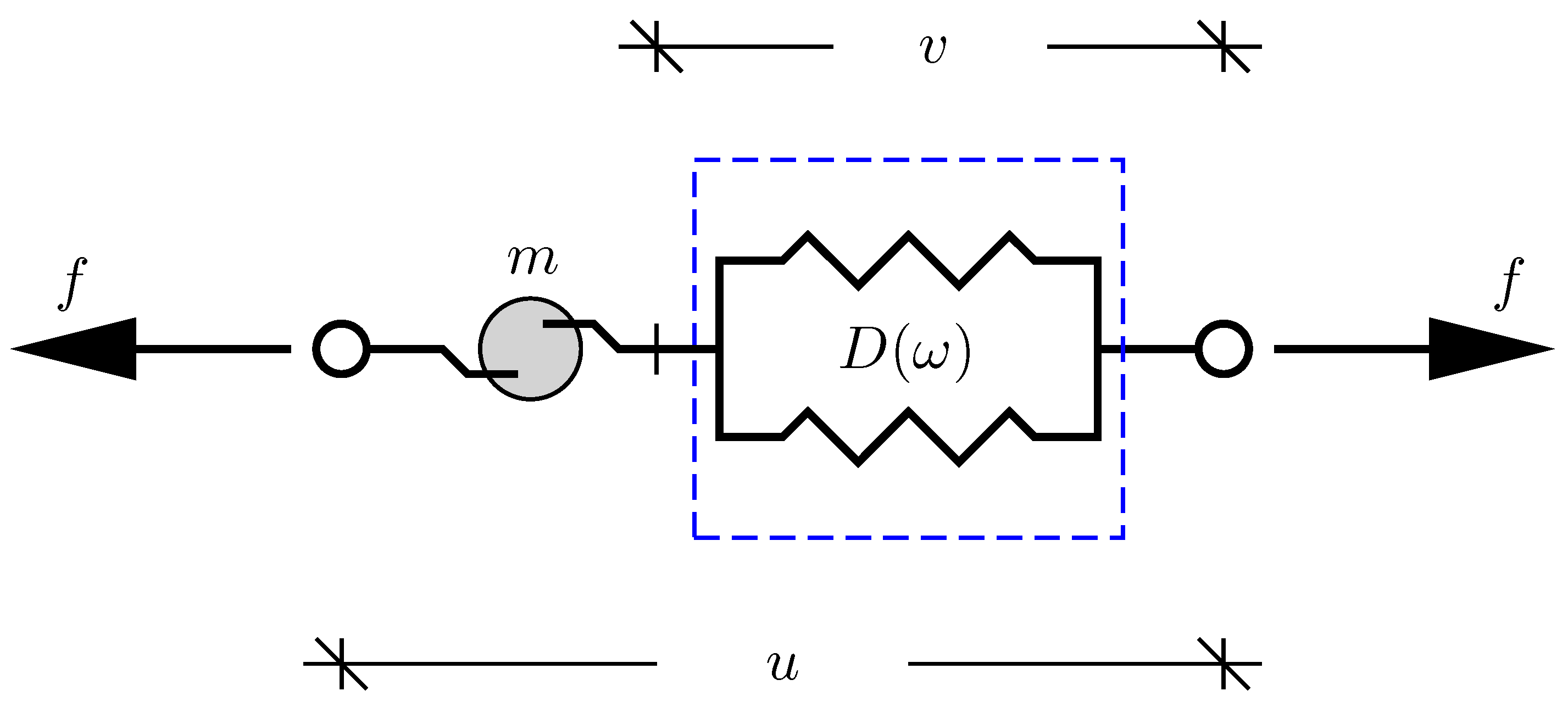

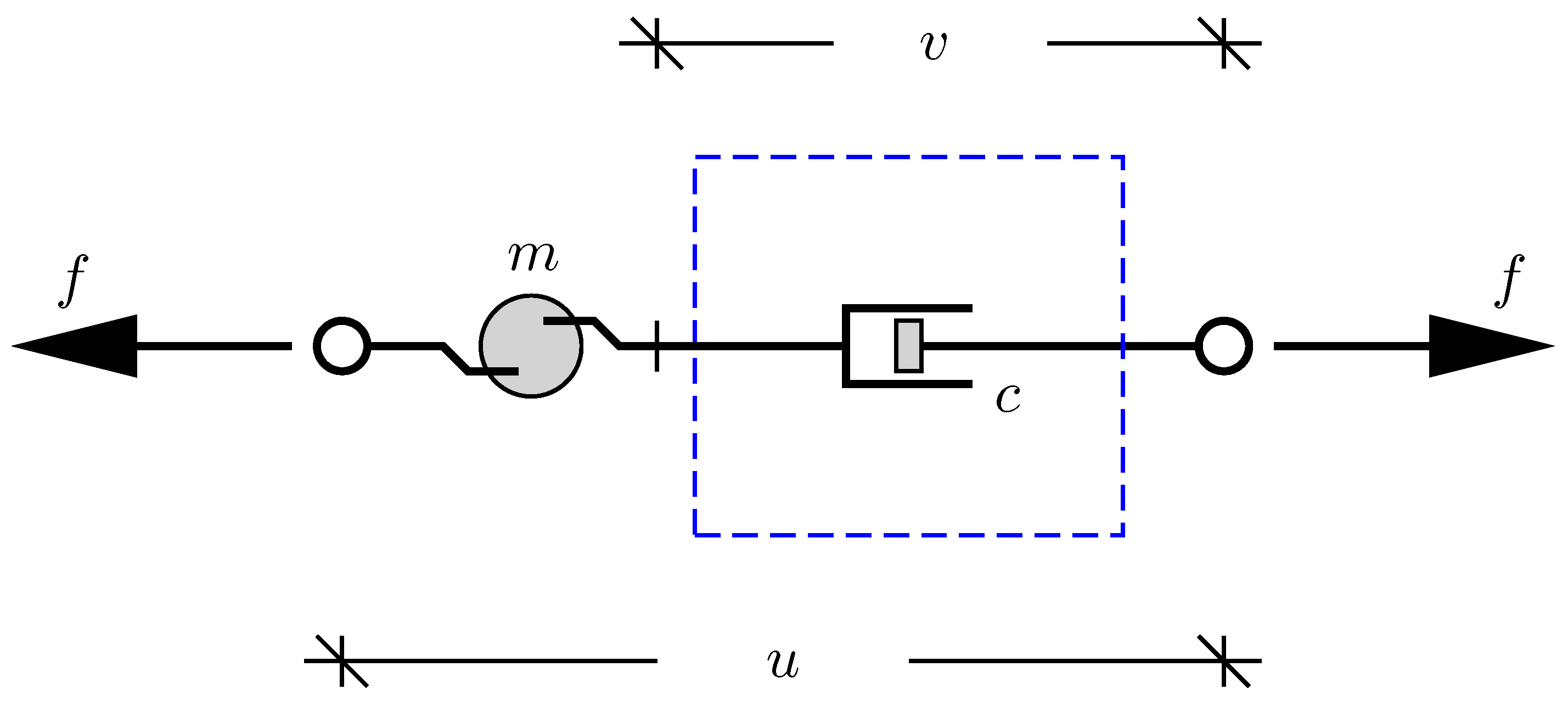

1.1. Inerter Dampers

1.2. Hybrid Mass and Inerter Dampers

1.3. Outline of Paper

2. Governing Equations of Motion

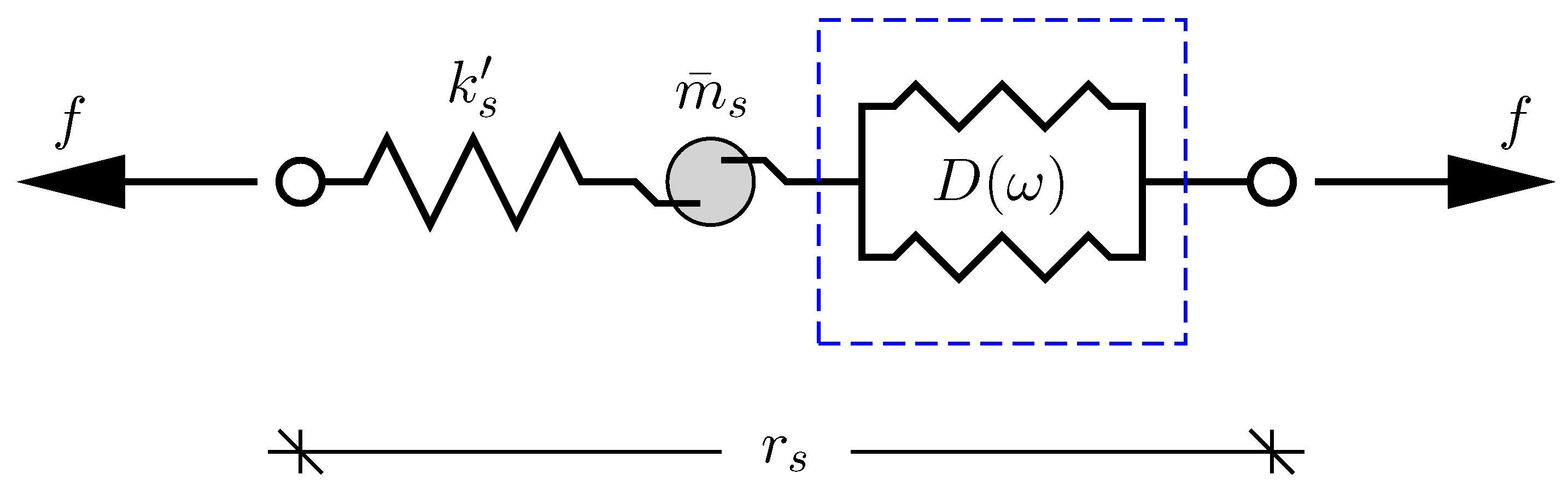

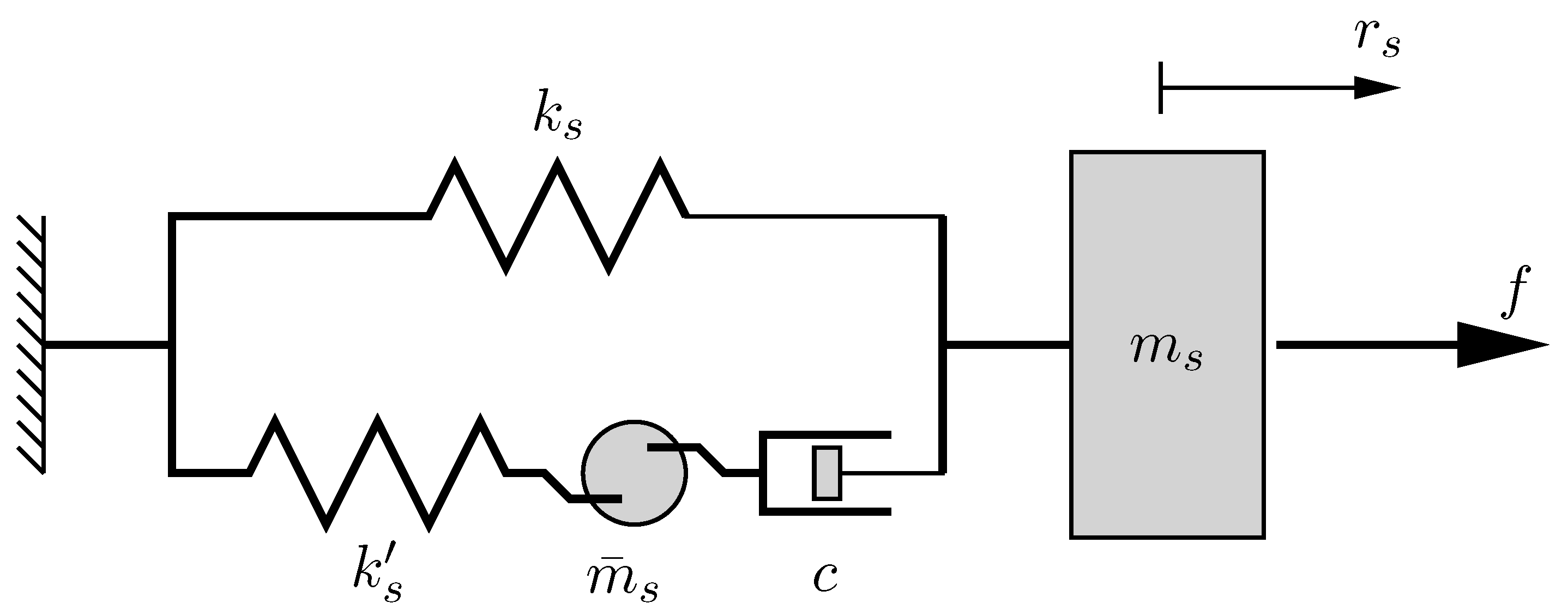

2.1. Inerter Damper Model

2.2. Limiting Eigenvalue Problems

2.3. Modal Representation

2.4. Residual Mode Correction

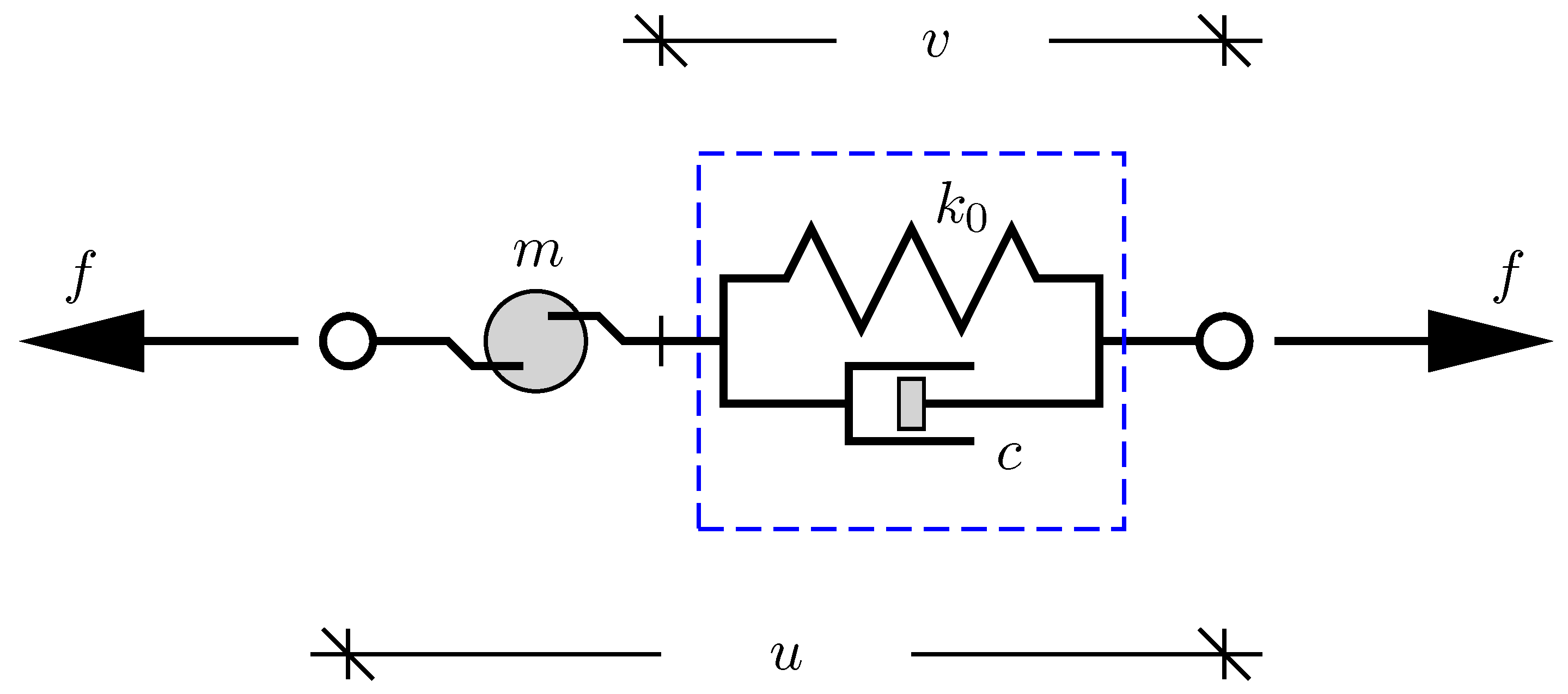

3. Viscous Inerter Damper

3.1. Single-Mode Model

3.2. Correction Coefficients

3.3. Optimal Mass Ratio

3.4. Optimal Damping

4. Damping of the Building Model

4.1. Modal Parameters

4.2. Tuning Parameters

4.3. Coupled Equations of Motion

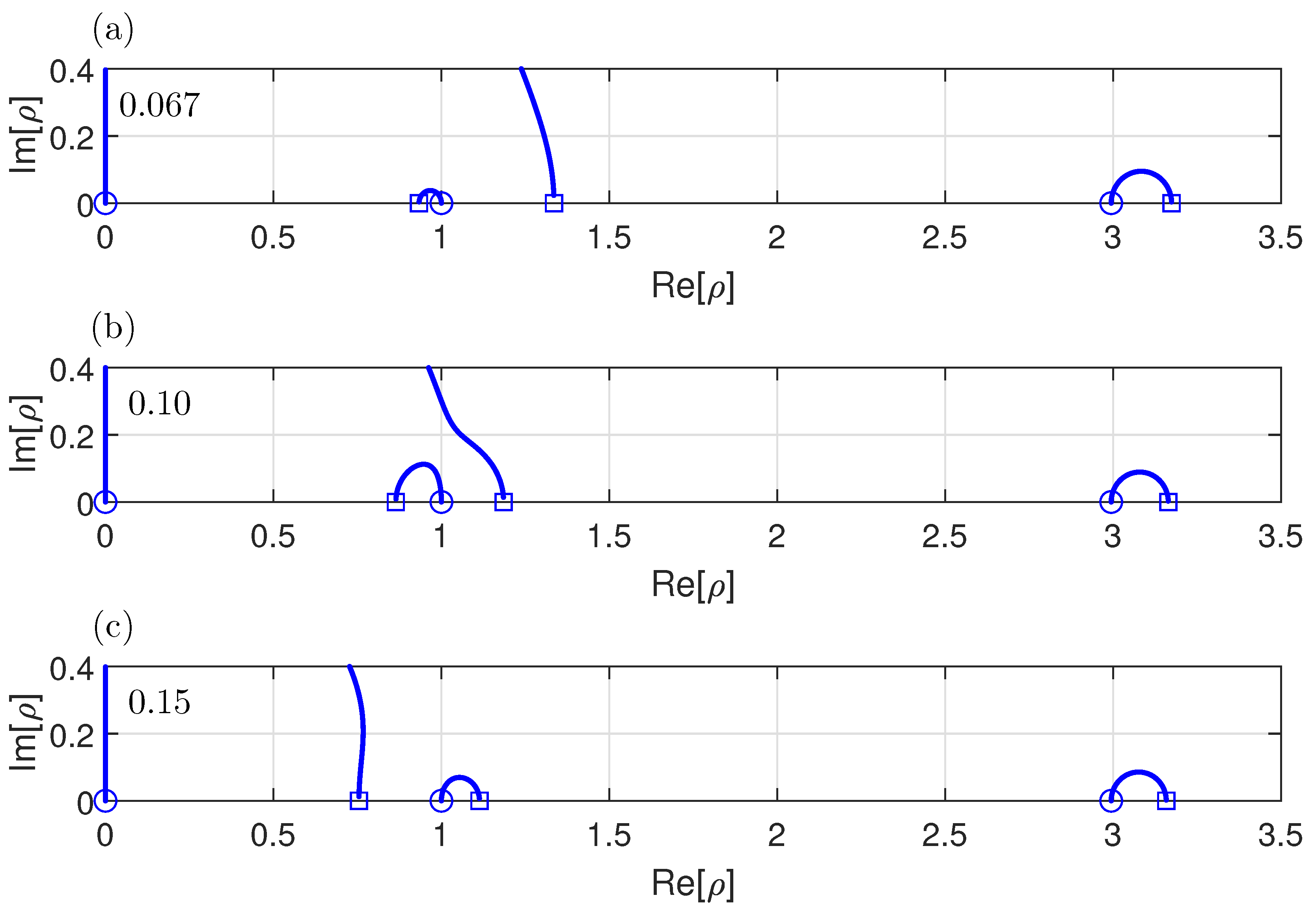

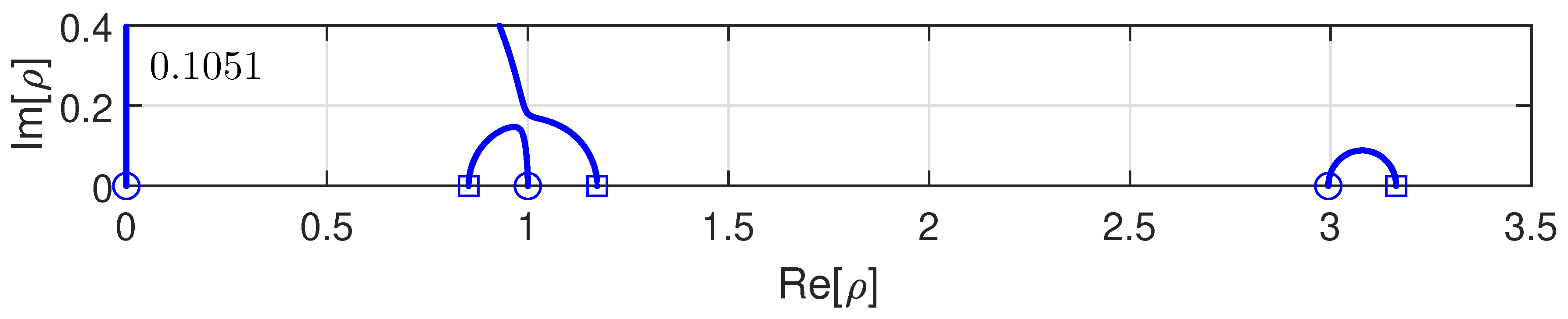

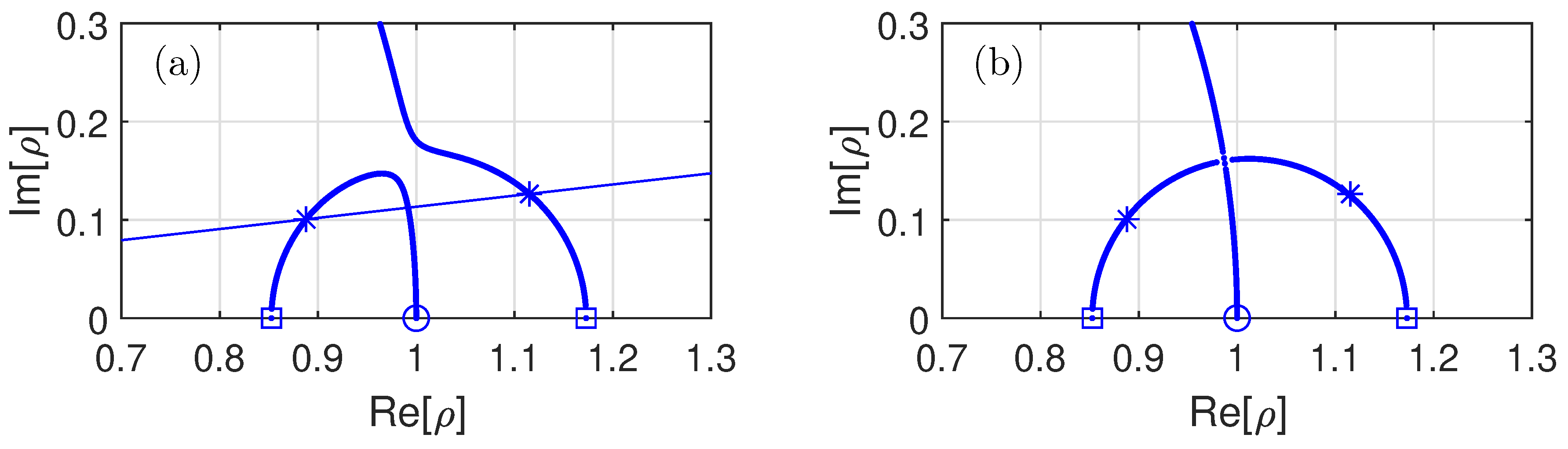

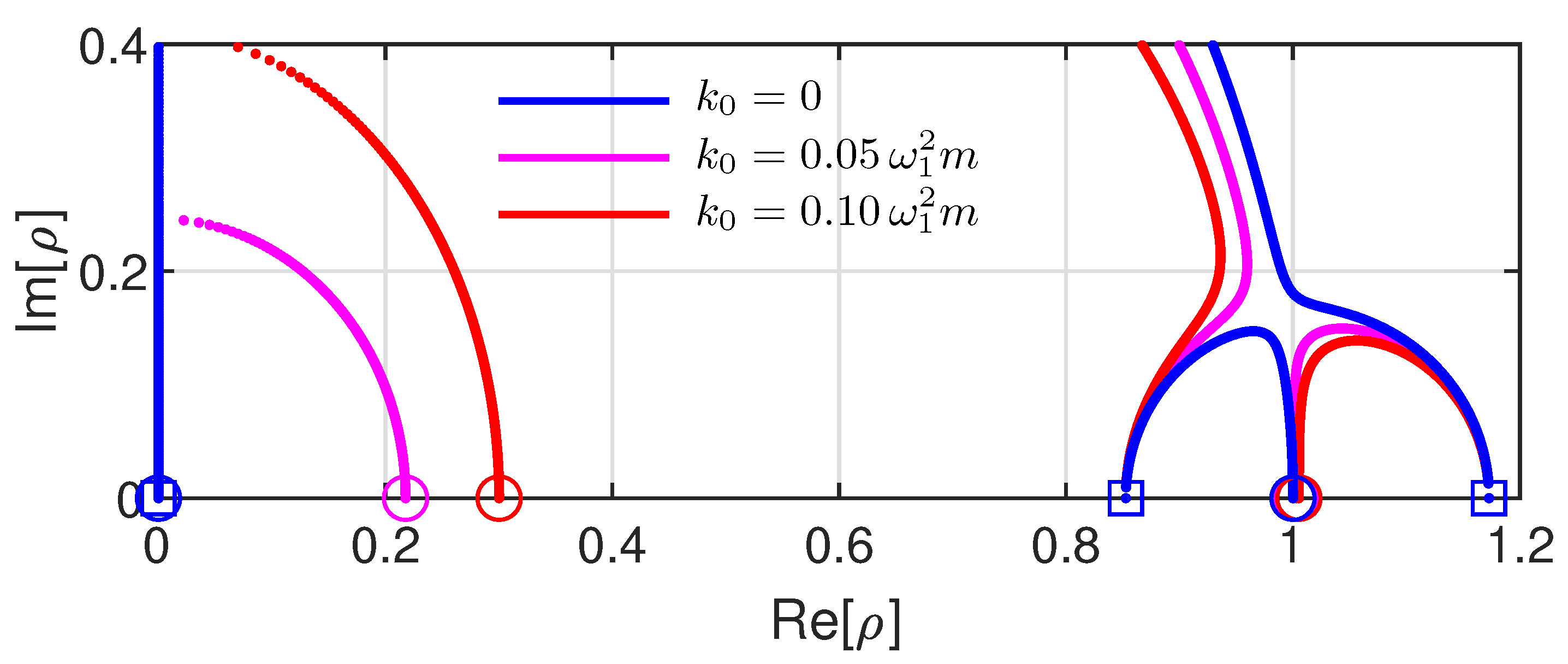

4.4. Root Locus Analysis

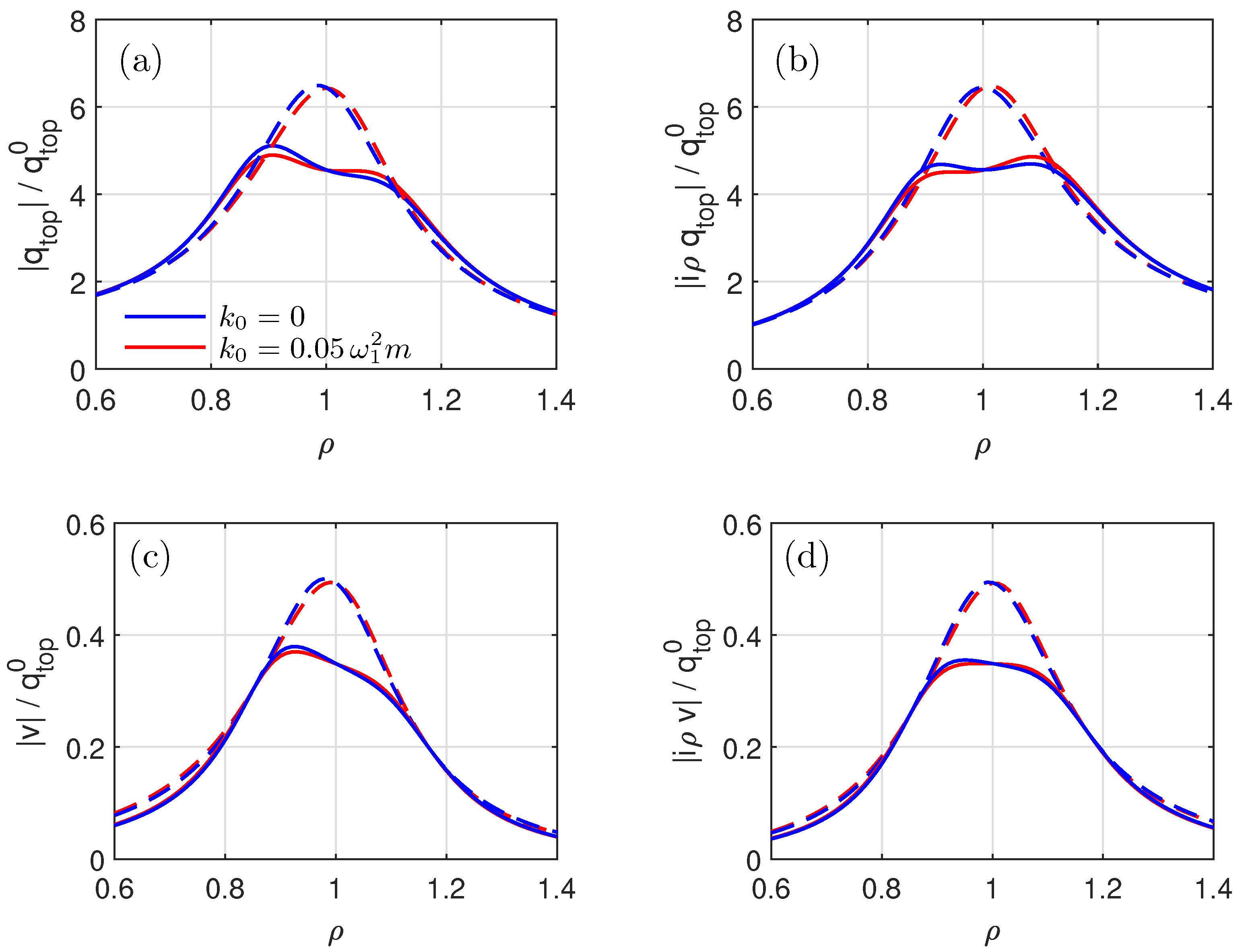

4.5. Frequency Response Analysis

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Den Hartog, J. Mechanical Vibrations, 4th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Warburton, G.B. Optimum absorber parameters for various combinations of response and excitation parameters. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 1982, 10, 381–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, R.; Soong, T.T. Parametric study and simplified design of tuned mass dampers. Eng. Struct. 1998, 20, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C. Mass dampers and their optimal designs for building vibration control. Eng. Struct. 1999, 21, 454–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, A.Y.; Shang, G. Vibration control in a 101-story building using a tuned mass damper. J. Appl. Sci. Eng. 2014, 17, 141–156. [Google Scholar]

- Elias, S.; Matsagar, V. Research developments in vibration control of structures using passive tuned mass dampers. Annu. Rev. Control 2017, 44, 129–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, S.; Matsagar, V. Wind response control of tall buildings with a tuned mass damper. J. Build. Eng. 2018, 15, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, M.; Alipour, A. Methodologies to mitigate wind-induced vibration of tall buildings: A state-of-the-art review. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 33, 101582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krenk, S. Frequency analysis of the tuned mass damper. J. Appl. Mech. 2005, 72, 936–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krenk, S.; Høgsberg, J. Tuned mass absorber on a flexible structure. J. Sound Vib. 2014, 333, 1577–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M. Synthesis of mechanical networks: The inerter. IEEE Trans. Automat. Contr. 2002, 47, 1648–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marian, L.; Giaralis, A. The tuned mass-damper-inerter for harmonic vibrations suppression, attached mass reduction, and energy harvesting. Smart Struct. Syst. 2017, 19, 665–678. [Google Scholar]

- Papageorgiou, C.; Smith, M.C. Laboratory experimental testing of inerters. In Proceedings of the 44th IEEE Conference on Decision and Control, Seville, Spain, 15 December 2005; pp. 3351–3356. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, F.; Borchsenius, F.; Distl, J.; Braun, C. Performance of numerically optimized tuned mass damper with inerter (TMDI). Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 6204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazar, I.; Neild, S.; Wagg, D. Using an inerter-based device for structural vibration suppression. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 2014, 43, 1129–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Chen, M.Z. Performance evaluation for inerter-based dynamic vibration absorbers. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2015, 99, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Chen, M.; Shu, Z.; Huang, L. Analysis and optimisation for inerter-based isolators via fixed-point theory and algebraic solution. J. Sound Vib. 2015, 346, 17–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krenk, S.; Høgsberg, J. Tuned resonant mass or inerter-based absorbers: Unified calibration with quasi-dynamic flexibility and inertia correction. Proc. Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2016, 472, 20150718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krenk, S. Resonant inerter based vibration absorbers on flexible structures. J. Frankl. Inst. 2019, 356, 7704–7730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, C.; Zhang, R.; Luo, H.; Li, C.; Shen, H. Demand-based optimal design of oscillator with parallel-layout viscous inerter damper. Struct. Control Health Monit. 2018, 25, e2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zhao, Z.; Pan, C.; Ikago, K.; Xue, S. Damping enhancement principle of inerter system. Struct. Control Health Monit. 2020, 27, e2523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Lombardi, L.; De Luca, F.; Farbiarz, Y.; Blandon, J.J.; Lara, L.A.; Rendon, J.F.; Jiang, J.Z.; Neild, S. Optimal design of inerter-integrated vibration absorbers for seismic retrofitting of a high-rise building in Colombia. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2019, 1264, 012031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.; Niyitangamahoro, A.; Feng, Z.; Zhu, H. Tuned inerter dampers for civil structures subjected to earthquake ground motions: Optimum design and seismic performance. Eng. Struct. 2019, 198, 109470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barredo, E.; Rojas, G.; Mayén, J.; Flores-Hernández, A. Innovative negative-stiffness inerter-based mechanical networks. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2021, 205, 106597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, S.; Banerjee, A.; Adhikari, S. The optimal design of negative stiffness inerter passive dampers for structures. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2023, 258, 108551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Zhang, R.; Jiang, Y.; De Domenico, D.; Pan, C. Displacement-dependent damping inerter system for seismic response control. Appl. Sci. 2019, 10, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Qiao, H.; De Domenico, D.; Zhu, Z.; Xie, Z. Wind-induced response control of high-rise buildings using inerter-based vibration absorbers. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 5045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Zhang, Z.; Hua, X. Equal modal damping-based optimal design of a grounded tuned mass-damper-inerter for flexible structures. Struct. Contr. Health Monit. 2022, 29, e3106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Angelis, M.; Giaralis, A.; Petrini, F.; Pietrosanti, D. Optimal tuning and assessment of inertial dampers with grounded inerter for vibration control of seismically excited base-isolated systems. Eng. Struct. 2019, 196, 109250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Zuo, L.; Wang, X.; Peng, J.; Wang, W. Exact H2 optimal solutions to inerter-based isolation systems for building structures. Struct. Contr. Health Monit. 2019, 26, e2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, R.; De Domenico, D.; Pan, C. Optimal design based on analytical solution for storage tank with inerter isolation system. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2020, 129, 105924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jangid, R.S. The role of a simple inerter in seismic base isolation. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marian, L.; Giaralis, A. Optimal design of a novel tuned mass-damper–inerter (TMDI) passive vibration control configuration for stochastically support-excited structural systems. Probabilistic Eng. Mech. 2014, 38, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giaralis, A.; Marian, L. Use of inerter devices for weight reduction of tuned mass-dampers for seismic protection of multi-story building: The Tuned Mass-Damper-Interter (TMDI). In Proceedings of the SPIE Smart Structures and Materials + Nondestructive Evaluation and Health Monitoring, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 20–24 March 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Giaralis, A.; Petrini, F. Wind-induced vibration mitigation in tall buildings using the tuned mass-damper-inerter. J. Struct. Eng. 2017, 143, 04017127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giaralis, A.; Taflanidis, A. Optimal tuned mass-damper-inerter (TMDI) design for seismically excited MDOF structures with model uncertainties based on reliability criteria. Struct. Contr. Health Monit. 2018, 25, e2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Domenico, D.; Ricciardi, G. An enhanced base isolation system equipped with optimal tuned mass damper inerter (TMDI). Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 2018, 47, 1169–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Domenico, D.; Impollonia, N.; Ricciardi, G. Soil-dependent optimum design of a new passive vibration control system combining seismic base isolation with tuned inerter damper. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2018, 105, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, F.; Huber, P.; Borchsenius, F.; Braun, C. Performance of TMDI for tall building damping. Actuators 2020, 9, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barredo, E.; Blanco, A.; Colín, J.; Penagos, V.; Abúndez, A.; Vela, L.; Meza, V.; Cruz, R.; Mayén, J. Closed-form solutions for the optimal design of inerter-based dynamic vibration absorbers. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2018, 144, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Chen, L.; Lee, H.P.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, X. A review of the inerter and inerter-based vibration isolation: Theory, devices, and applications. J. Frankl. Inst. 2022, 359, 7677–7707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Bi, K.; Hao, H. Inerter-based structural vibration control: A state-of-the-art review. Eng. Struct. 2021, 243, 112655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krenk, S.; Høgsberg, J. Equal modal damping design for a family of resonant vibration control formats. J. Vib. Control 2013, 19, 1294–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Høgsberg, J.; Lossouarn, B.; Deü, J.F. Tuning of vibration absorbers by an effective modal coupling factor. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2024, 268, 109009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Høgsberg, J.; Krenk, S. Calibration of piezoelectric RL shunts with explicit residual mode correction. J. Sound Vib. 2017, 386, 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raze, G.; Dietrich, J.; Kerschen, G. Tuning and performance comparison of multiresonant piezoelectric shunts. J. Intell. Mater. Syst. Struct. 2022, 33, 2470–2491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Høgsberg, J. Consistent frequency-matching calibration procedure for electromechanical shunt absorbers. J. Vib. Control 2020, 26, 1133–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Géradin, M.; Rixen, D. Mechanical Vibrations: Theory and Application to Structural Dynamics, 2nd ed.; John Wiley: Chichester, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Høgsberg, J.; Krenk, S. Linear control strategies for damping of flexible structures. J. Sound Vib. 2006, 293, 59–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| (1) | Choose m and determine |

| (2) | Solve (9) and determined and from (31) |

| (3) | Determine from (34) and from (35) |

| (4) | Update from (38) and |

| (5) | Repeat (2) to (4) until has converged |

| j | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

| 1.00 | 2.99 | 4.97 | 6.92 | 8.82 | 10.68 | 12.47 | 14.19 | 15.83 | 17.37 | |

| 1.000 | 0.113 | 0.042 | 0.022 | 0.015 | 0.011 | 0.008 | 0.007 | 0.006 | 0.006 | |

| 0.853 | 1.17 | 3.16 | 5.23 | 7.27 | 9.26 | 11.2 | 13.1 | 14.8 | 16.5 | |

| 0.185 | 0.259 | 9.37 | 29.6 | 61.6 | 106.87 | 168.35 | 250.1 | 358.3 | 502.1 |

| 0.1051 | 0.1025 | 4.1440 | 0.1025 | 0.2264 |

| 0.1126 | 0.1159 | 0.1190 | |

| 0.1126 | 0.1106 | 0.1084 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Høgsberg, J. Tuning of a Viscous Inerter Damper: How to Achieve Resonant Damping Without a Damper Resonance. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 676. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15020676

Høgsberg J. Tuning of a Viscous Inerter Damper: How to Achieve Resonant Damping Without a Damper Resonance. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(2):676. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15020676

Chicago/Turabian StyleHøgsberg, Jan. 2025. "Tuning of a Viscous Inerter Damper: How to Achieve Resonant Damping Without a Damper Resonance" Applied Sciences 15, no. 2: 676. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15020676

APA StyleHøgsberg, J. (2025). Tuning of a Viscous Inerter Damper: How to Achieve Resonant Damping Without a Damper Resonance. Applied Sciences, 15(2), 676. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15020676