CottonCapT6: A Multi-Task Image Captioning Framework for Cotton Disease and Pest Diagnosis Using CrossViT and T5

Abstract

1. Introduction

- A high-quality image–text dataset, CottonDP, was constructed to provide domain-specific image–text data for the diagnosis of cotton diseases and pests.

- A training strategy based on classification enhancement was designed. The core innovation of the framework is a two-stage training strategy. Firstly, the visual encoder was pretrained through the cotton pest classification task to learn the discriminant visual representation from local lesion microscopic features to global distribution. This enhanced visual perception was then transferred to the description generation task, significantly improving the semantic accuracy and interpretability of diagnostic descriptions.

- The model effectively describes the details of cotton pest and disease images, improves the accuracy of diagnosis, and is of great value for promoting the informatization and intelligent management of cotton planting.

2. Materials and Methods

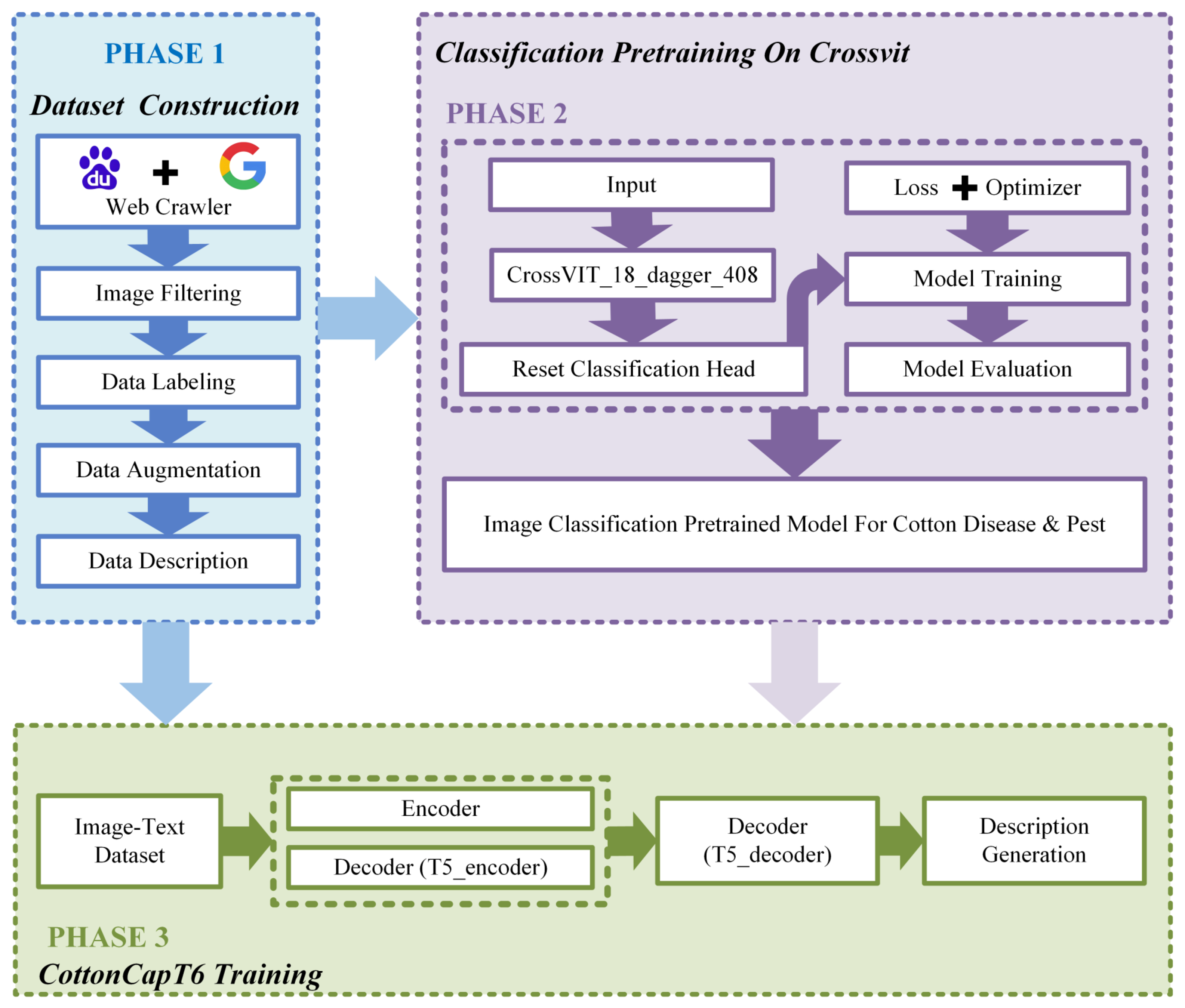

2.1. Research Framework

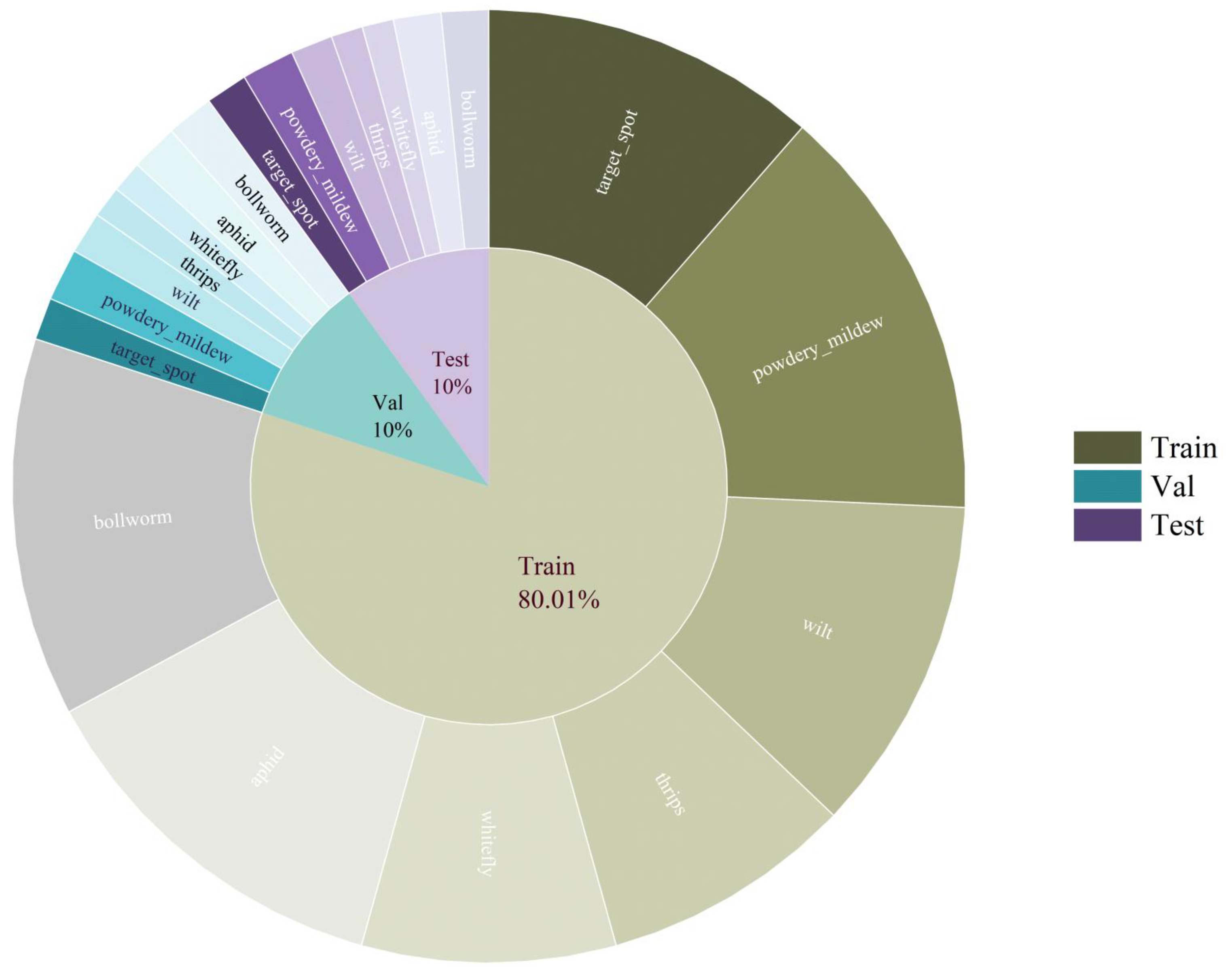

2.2. Dataset Construction

2.2.1. Data Collection

2.2.2. Image Preprocessing and Augmentation

2.2.3. Data Preprocessing for Classification Task

2.2.4. Data Preprocessing for Captioning Task

- Cotton target spot disease: brown circular lesions;

- Cotton whitefly: pale bodies and white wing covers.

- Cotton target spot disease: Small brown lesions on cotton leaves suggest target spot.

- Cotton whitefly: Cotton whiteflies show pale bodies and white wing covers.

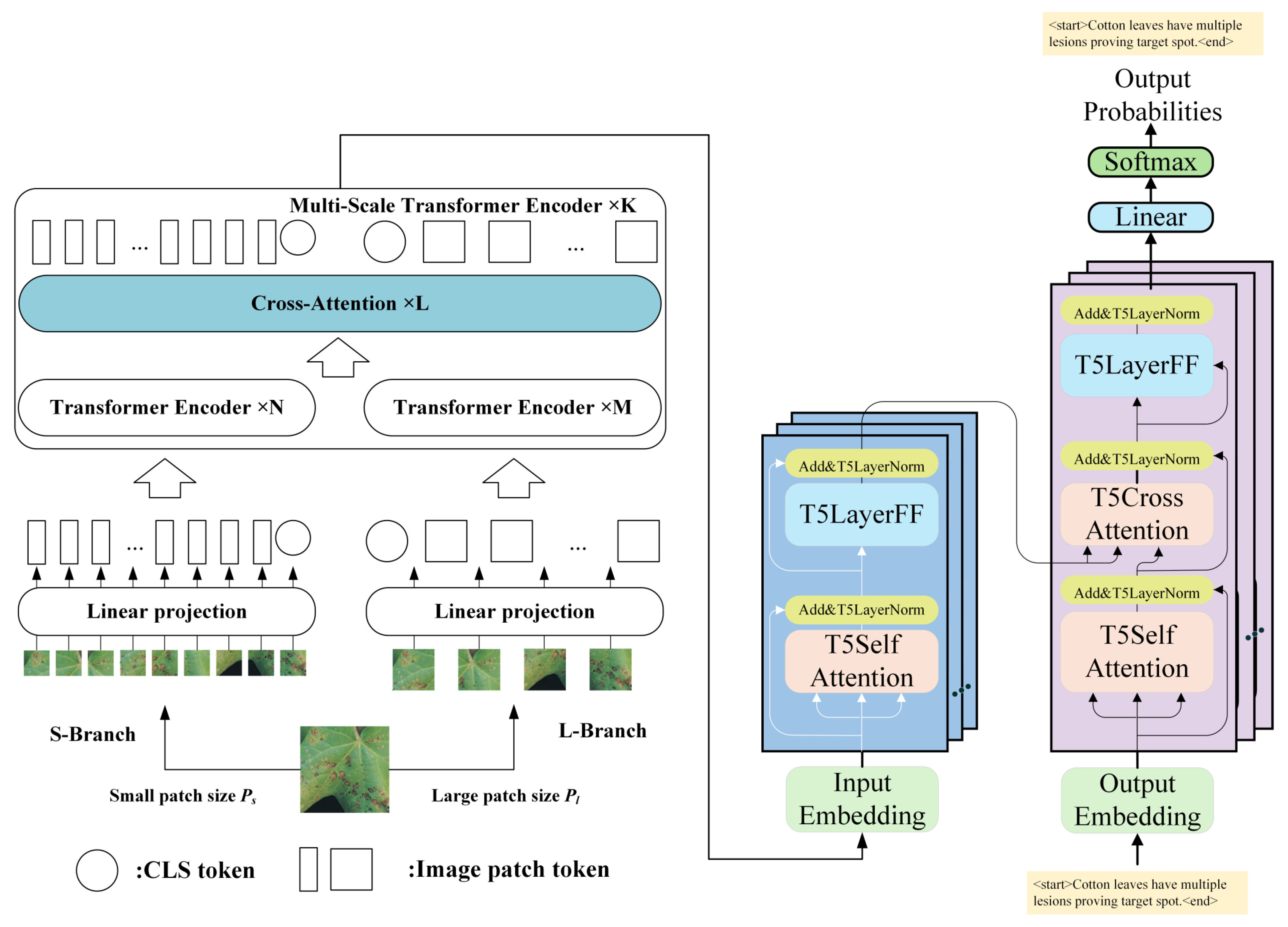

2.3. Model Architecture

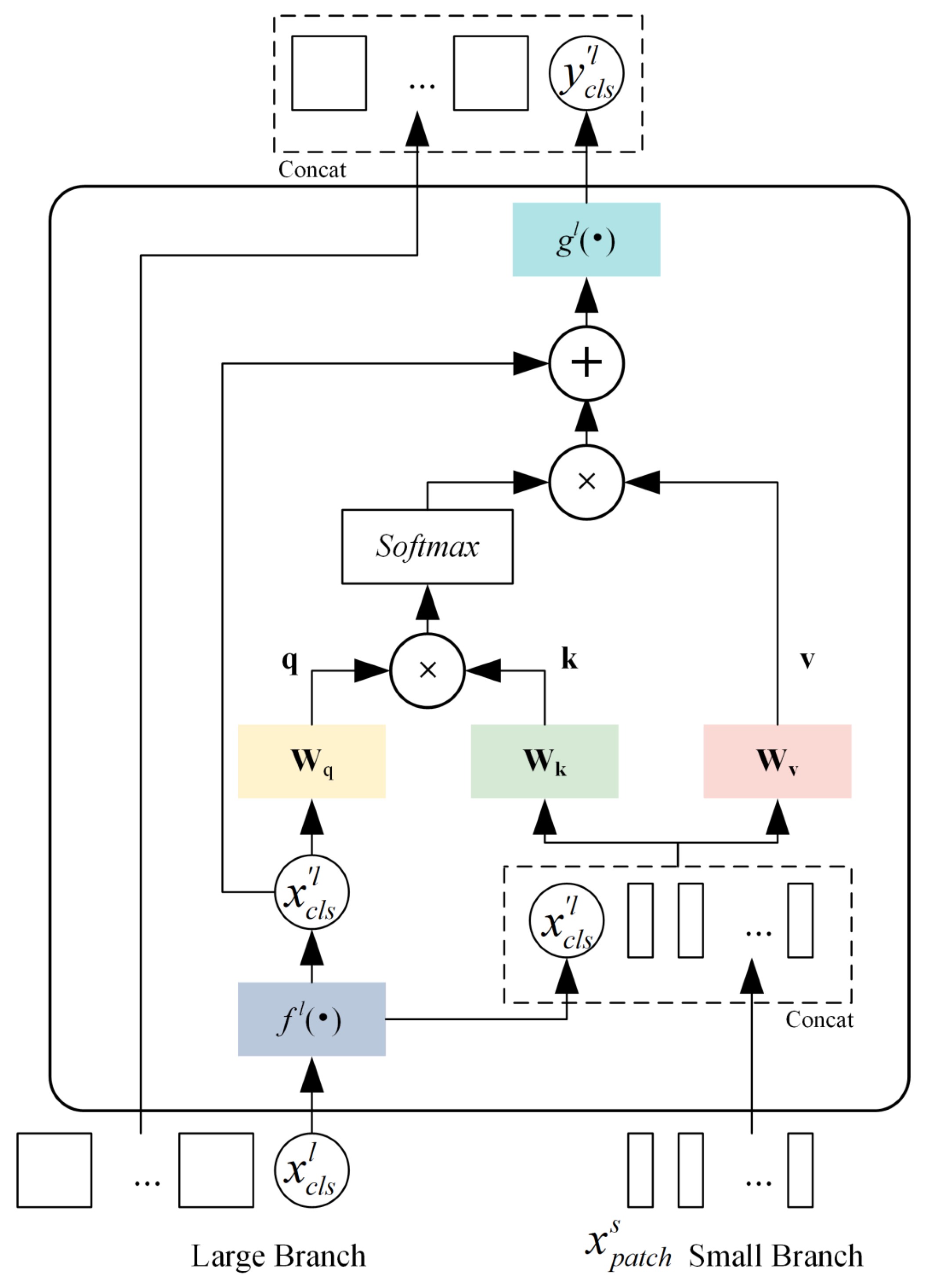

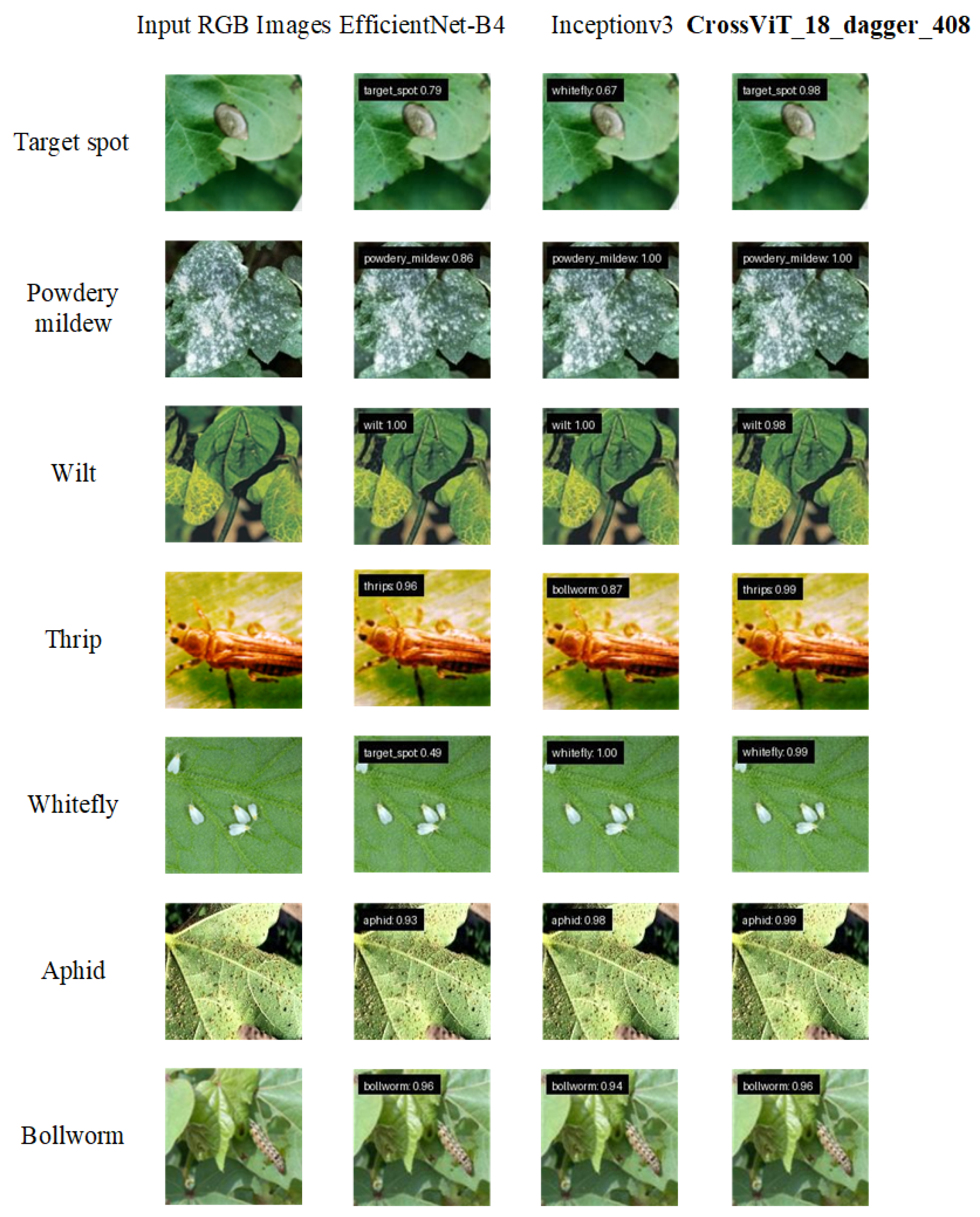

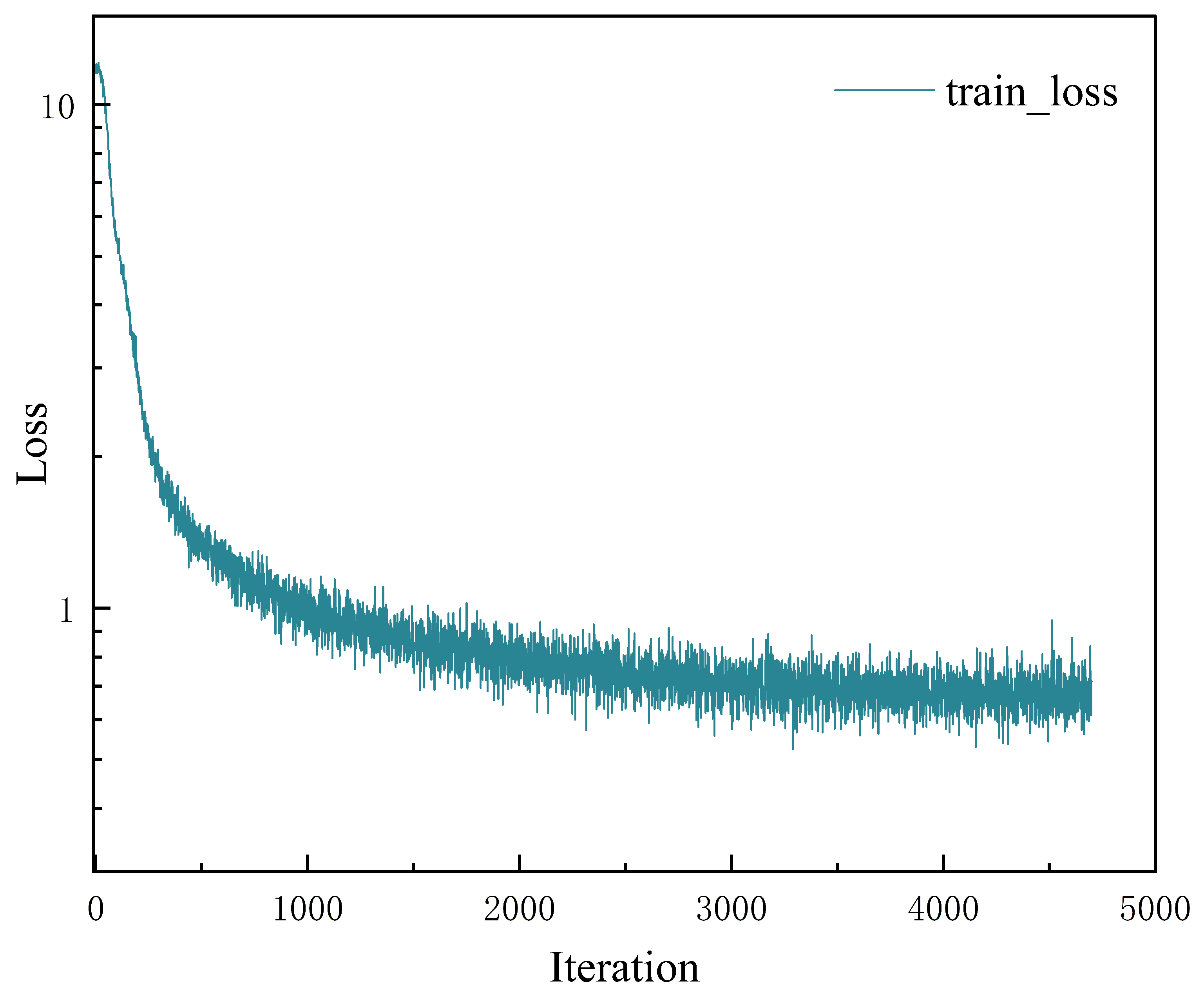

2.3.1. Classification Pretraining with CrossViT-18-Dagger-408

2.3.2. Captioning with T5 and Transfer Learning

- CrossViT-18-Dagger-408 Encoder

- T5 Decoder

2.3.3. Overall Pipeline and Model Architecture

2.4. Experimental Setup

2.5. Evaluation Indicators

3. Results

3.1. The Results of the Image Classification Task

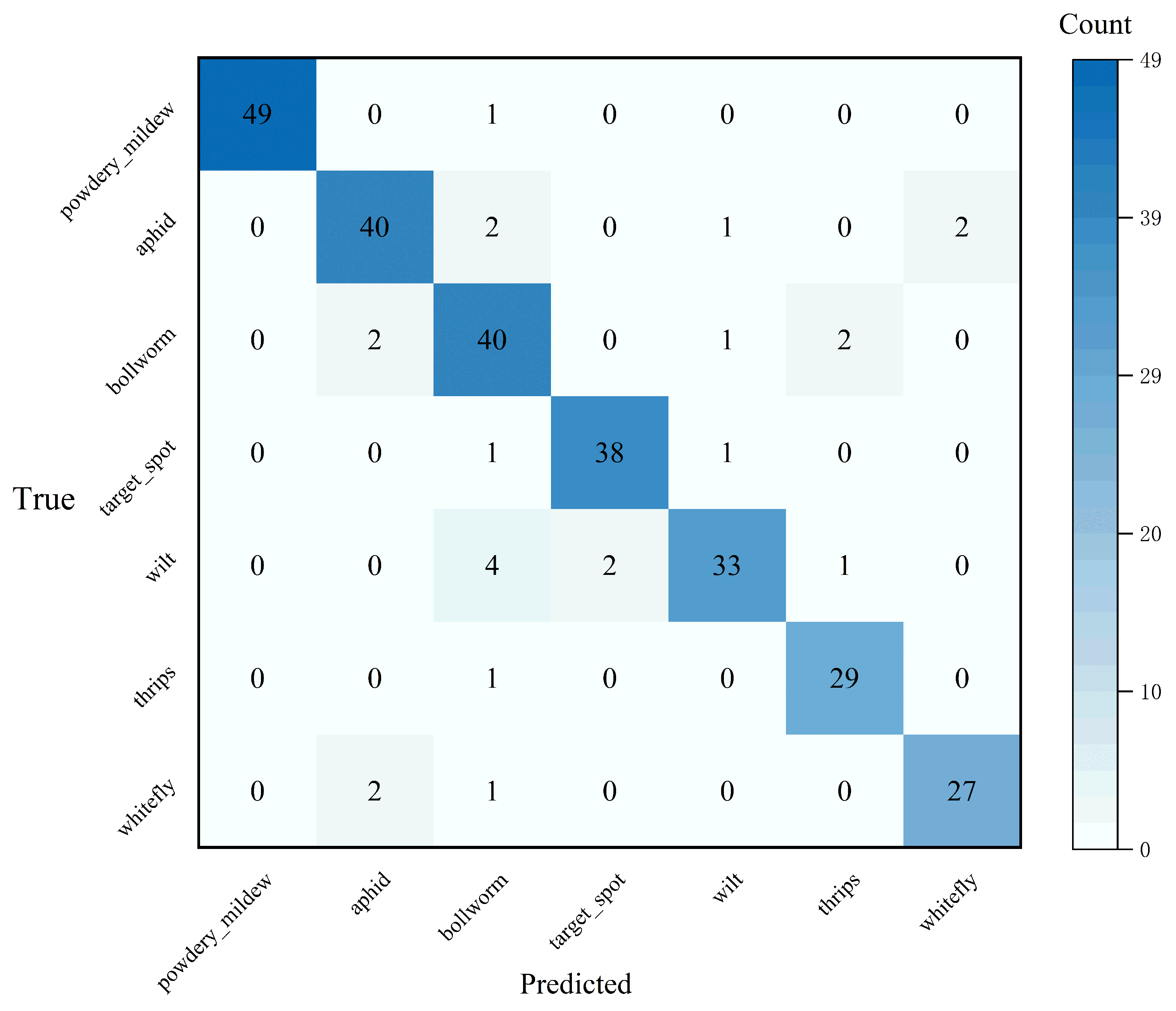

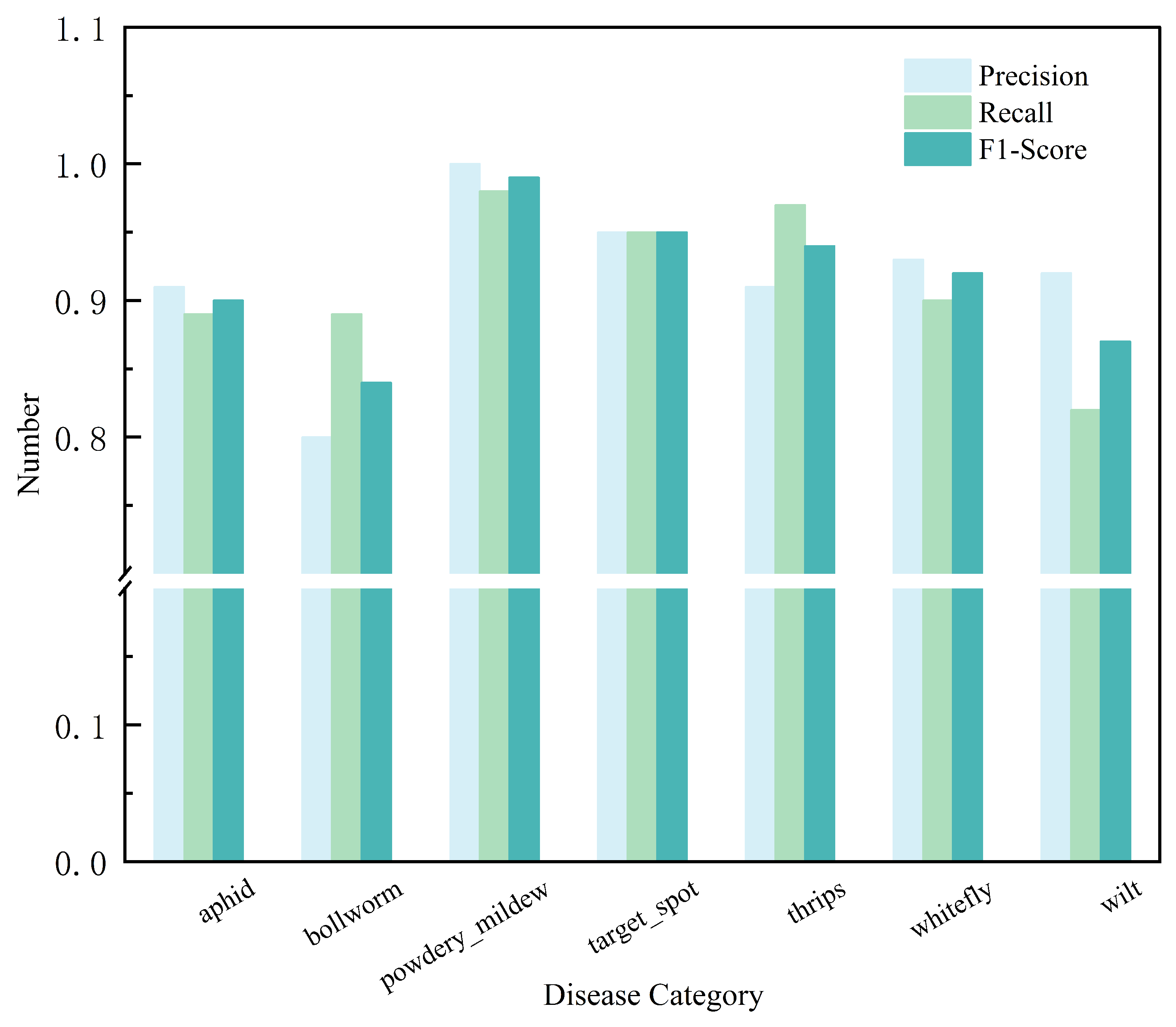

3.1.1. Quantitative Analysis of Image Classification Task

3.1.2. Qualitative Analysis of Image Classification Task

3.2. The Results of the Image Captioning Task

3.2.1. Quantitative Analysis of the Image Captioning Task

3.2.2. Qualitative Analysis of Image Captioning Task

- Disease Image 1: The model-generated description includes keywords such as ‘target-pattern lesions,’ which are semantically consistent with the manually annotated terms ‘yellowish-brown spots’ and ‘round spores,’ accurately capturing the morphology and typical symptoms of the lesions, demonstrating strong semantic alignment capability.

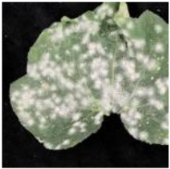

- Disease Image 2: The predicted text ‘Fuzzy white deposits on young leaves’ and the improved version ‘Fine white fungal growth accumulates…’ both accurately reflect the growth characteristics of powdery mildew, highly consistent with annotated information such as ‘white fungal hyphae’ and ‘leaf surface coverage.’

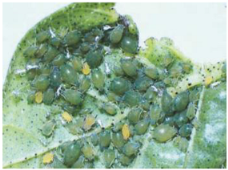

- Pest image 1: Descriptions such as ‘Cotton whiteflies producing waxy platelets on leaves’ and its enhanced version accurately identify key pest characteristics such as ‘whiteflies’ and their ‘waxy secretions.’

- Pest Image 2: Texts such as ‘Aphids fully cover top cotton leaf groups’ or ‘Dense aphid populations blanket…’ accurately depict the locations where aphids congregate and the forms of damage they cause, with complete keyword extraction and natural, fluent expression.

4. Discussion

- Category Confusion and Potential Mitigation Strategies

- Enhancing Caption Richness and Actionability

- Addressing Data Scarcity and Complexity through Augmentation

- Optimizing the Training Framework for Efficiency and Transferability

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CottonCapT6 | Cross Vision Transformer-18-Dagger-408 and Text-to-Text Transfer Transformer for Cotton Disease and Pest Image Captioning |

| CrossViT-18 Dagger-408 | Cross Vision Transformer-18 Dagger-408 |

| T5 | Text-to-Text Transfer Transformer |

| CIDEr | Consensus-based Image captioning Evaluation Score |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| CNN-LSTM | Convolutional Neural Network–Long Short-Term Memory |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| BLIP | Bootstrapping Language-Image Pretraining |

| UMLS | Unified Medical Language System |

| BLEU-4 | Bilingual Evaluation Understudy Score with precision—4-gram |

| VGG16 | Visual Geometry Group 16-layer Network |

| LLAMA-4 | Large Language Model Meta AI 4 |

| PromptCap | Prompt-based Captioning |

| BLIP-DP | Bootstrapping Language-Image Pretraining with Dynamic Prompting |

| LLM-based | Large Language Model-based |

| ID | Identification |

| ViT | Vision Transformer |

| CLS | Class |

| MLP | Multi-Layer Perceptron |

| ROUGE-L | Recall-Oriented Understudy for Gisting Evaluation—Longest Common Subsequence |

| METEOR | Metric for Evaluation of Translation with Explicit Ordering |

| ResNet-101 | Residual Network-101 |

| EfficientNet-B4 | Efficient Network-B4 |

| Inceptionv3 | Inception Version 3 |

| MobileNetV2 | Mobile Network Version 2 |

| ViT-B/16 | Vision Transformer Base with 16 × 16 Patch Size |

References

- Su, Y.; Wei, X.; Wang, Z.; Gao, L.; Zhang, Z. Cotton production in the Yellow River Basin of China: Reforming cropping systems for ecological, economic stability and sustainable production. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2025, 9, 1615566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Wang, G.; Du, H.; Liu, J.; Yang, Q. The Effect of Agricultural Mechanization Services on the Technical Efficiency of Cotton Production. Agriculture 2025, 15, 1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Tong, J.; Fang, Z. Assessing the drivers of sustained agricultural economic development in China: Agricultural productivity and poverty reduction efficiency. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishshash, P.; Nirob, A.S.; Shikder, H.; Sarower, A.H.; Bhuiyan, T.; Noori, S.R.H. A comprehensive cotton leaf disease dataset for enhanced detection and classification. Data Brief 2024, 57, 110913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamilaris, A.; Prenafeta-Boldú, F.X. Deep learning in agriculture: A survey. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2018, 147, 70–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarekegn, A.N.; Ullah, M.; Cheikh, F.A. Deep learning for multi-label learning: A comprehensive survey. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.16549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, G.D.; Chaudhuri, U.; Varela, S.; Ahuja, N.; Leakey, A.D. Machine learning-enabled computer vision for plant phenotyping: A primer on AI/ML and a case study on stomatal patterning. J. Exp. Bot. 2024, 75, 6683–6703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juneja, M.; Saini, S.K.; Chanana, C.; Jindal, P. MRI-CropNet for Automated Cropping of Prostate Cancer in Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2024, 136, 1183–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinyals, O.; Toshev, A.; Bengio, S.; Erhan, D. Show and tell: A neural image caption generator. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015; pp. 3156–3164. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, K.; Ba, J.; Kiros, R.; Cho, K.; Courville, A.; Salakhudinov, R.; Bengio, Y. Show, attend and tell: Neural image caption generation with visual attention. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Lille, France, 6–11 July 2015; pp. 2048–2057. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Zitnick, C.L. Mind’s eye: A recurrent visual representation for image caption generation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015; pp. 2422–2431. [Google Scholar]

- Alzubi, J.A.; Jain, R.; Nagrath, P.; Satapathy, S.; Taneja, S.; Gupta, P. Deep image captioning using an ensemble of CNN and LSTM based deep neural networks. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 2021, 40, 5761–5769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, R.V.; Mohanty, A.; Tyagi, S.; Mishra, S.; Satapathy, S.K.; Mohanty, S.N. A hybrid deep learning framework with CNN and Bi-directional LSTM for store item demand forecasting. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2022, 103, 108358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Q.; Jin, H.; Wang, Z.; Fang, C.; Luo, J. Image captioning with semantic attention. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 4651–4659. [Google Scholar]

- Kamal, M.S.; Nimmy, S.F.; Islam, M.R.; Naseem, U. Explainable Medical Image Captioning. In Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference, Singapore, 5–9 May 2025; pp. 2253–2261. [Google Scholar]

- Abed, E.A.; Aguili, T. Automated Medical Image Captioning Using the BLIP Model: Enhancing Diagnostic Support with AI-Driven Language Generation. Diyala J. Eng. Sci. 2025, 18, 228–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Aboubakar, B.O.; Bhatti, M.; Talpur, B.A.; Ali, Y.A.; Al-Razgan, M.; Ghadi, Y.Y. Optimizing image captioning: The effectiveness of vision transformers and VGG networks for remote sensing. Big Data Res. 2024, 37, 100477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Hong, D.; Ge, S.; Luo, C.; Jiang, K.; Jin, H.; Wen, C. Rs-moe: A vision-language model with mixture of experts for remote sensing image captioning and visual question answering. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2025, 63, 5614918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Lu, X.; Zheng, L.; Sun, M.; Chen, S.; Chen, B.; Lv, C. Application of multimodal transformer model in intelligent agricultural disease detection and question-answering systems. Plants 2024, 13, 972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.I.; Lee, J.H.; Jang, S.H.; Oh, S.J.; Doo, I.C. Crop disease diagnosis with deep learning-based image captioning and object detection. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 3148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quoc, K.N.; Thu, L.L.T.; Quach, L.D. A Vision-Language Foundation Model for Leaf Disease Identification. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.07019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Xu, Z.; Pan, X.; Hu, Y.; Qin, C.; Goldstein, T.; Xu, R. Blip3-o: A family of fully open unified multimodal models-architecture, training and dataset. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.09568. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, B.; Wu, H.; Xu, W.; Dai, X.; Hu, H.; Lu, Y.; Zeng, M.; Liu, C.; Yuan, L. Florence-2: Advancing a unified representation for a variety of vision tasks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 4818–4829. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Y.; Dong, X.; Zhao, K.; Sirishantha, G.M.A.D.; Xiao, Y.; Yu, P.; Wang, Q. Plant Disease Phenotype Captioning Via Zero-Shot Learning with Semantic Correction Based on Llm. SSRN 2024, 5093837. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.; Hua, H.; Yang, Z.; Shi, W.; Smith, N.A.; Luo, J. Promptcap: Prompt-guided image captioning for vqa with gpt-3. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Paris, France, 1–6 October 2023; pp. 2963–2975. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.F.R.; Fan, Q.; Panda, R. Crossvit: Cross-attention multi-scale vision transformer for image classification. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 357–366. [Google Scholar]

- Raffel, C.; Shazeer, N.; Roberts, A.; Lee, K.; Narang, S.; Matena, M.; Liu, P.J. Exploring the limits of transfer learning with a unified text-to-text transformer. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2020, 21, 1–67. [Google Scholar]

| Image | Description |

|---|---|

|

1. Cotton leaves have multiple lesions proving target spot. 2. Multiple lesions on cotton leaves indicate target spot. 3. Cotton foliage shows several spots suggesting target spot disease. |

|

1. Cotton leaves show a white powdery coating, diagnosed as powdery mildew. 2. On cotton leaves, a white powdery coating appears, identified as powdery mildew. 3. Cotton foliage exhibits a whitish powder-like layer, diagnosed as powdery mildew. |

|

1. Cotton leaves appear purplish-red, diagnosed as wilt disease. 2. Purplish-red coloration appears on cotton leaves, which is diagnosed as wilt disease. 3. Cotton foliage shows a reddish-purple hue, identified as a symptom of wilt disease. |

|

1. Tiny black insects are congregating inside the cotton flower buds, diagnosed as thrips. 2. Inside the cotton flower buds, small black insects are gathering, identified as thrips. 3. Tiny dark insects were found clustered in the cotton flower, confirmed as thrips. |

|

1. Cotton whiteflies produce waxy platelets on leaves. 2. Waxy platelets are produced by cotton whiteflies on the leaves. 3. Cotton whiteflies secrete waxy particles on the leaves. |

|

1. The green insects are feeding on cotton leaves, thus identified as cotton aphids. 2. On cotton leaves, green insects are feeding, which have been identified as aphids. 3. Green bugs are munching on the cotton leaves, confirmed as cotton aphids. |

|

1. The boll has a small hole with a green insect emerging, possibly a bollworm. 2. From a small hole in the boll, a green insect emerges, possibly a bollworm. 3. The boll shows a tiny opening, and a green larva is coming out, possibly a bollworm. |

| Parameters | Image Classification Pretraining | Image Captioning Training |

|---|---|---|

| learning rate | 1 × 10−4 | 3 × 10−5 |

| optimizer | Adam | Adam |

| batch size | 16 | 64 |

| epochs | 10 | 10 |

| Model | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | F1-Score (%) | Accuracy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ResNet-101 | 81.00 | 78.90 | 79.00 | 80.50 |

| EfficientNet-B4 | 84.00 | 80.00 | 82.00 | 82.14 |

| Inceptionv3 | 88.00 | 87.00 | 87.00 | 86.79 |

| MobileNetV2 | 80.10 | 78.50 | 78.00 | 78.10 |

| VGG16 | 82.00 | 80.00 | 80.00 | 80.86 |

| SwinTransformer | 80.00 | 78.00 | 78.00 | 79.50 |

| ViT-B/16 | 91.00 | 89.00 | 90.00 | 90.60 |

| CrossViT_18_dagger_408 | 92.00 | 91.00 | 91.00 | 91.43 |

| Model | BLEU1 (%) | BLEU2 (%) | BLEU3 (%) | BLEU4 (%) | ROUGE-L (%) | METEOR (%) | CIDEr (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNN+LSTM | 65.6 | 50.5 | 42.1 | 36.6 | 55.5 | 34.1 | 135.3 |

| CNN+LSTM+Attention | 72.1 | 59.0 | 51.3 | 45.3 | 64.4 | 37.3 | 170.8 |

| CNN+Transformer | 68.5 | 54.0 | 46.5 | 40.5 | 60.0 | 36.5 | 165.0 |

| CNN+T5 | 70.0 | 58.5 | 51.0 | 44.5 | 63.0 | 38.0 | 180.0 |

| CrossViT+Transformer | 72.0 | 60.5 | 53.0 | 47.0 | 66.5 | 41.5 | 195.0 |

| CrossViT+T5 | 72.5 | 61.0 | 53.7 | 48.0 | 67.0 | 41.8 | 196.0 |

| CottonCapT6 | 72.9 | 61.7 | 54.4 | 48.7 | 67.4 | 42.0 | 197.2 |

| Image | Results |

|---|---|

|

1. Cotton leaves display target-pattern lesions indicating target spot. 2. Cotton leaves reveal target-pattern lesions indicating target spot. |

|

1. Fuzzy white deposits on young leaves, indicating powdery mildew colonization. 2. Fine white fungal growth accumulates on young leaves, suggesting active powdery mildew colonization. |

|

1. The cotton leaf is showing a large area of purple-red coloration, which has been diagnosed as wilt disease. 2. The cotton leaf exhibits extensive purple-red hues, diagnosed as wilt disease. |

|

1. Tiny black and small insects are on the cotton plant, diagnosed as thrips. 2. The cotton plant is infested with tiny black insects, confirmed as thrips. |

|

1. Cotton whiteflies produce waxy platelets on leaves. 2. Waxy platelets are produced by cotton whiteflies feeding across leaf surfaces. |

|

1. Aphids fully cover the top cotton leaf groups. 2. Dense aphid populations blanket the upper cotton leaves. |

|

1. The green worm is seen feeding on the cotton bolls, which might be bollworm. 2. The green worm feeding on the cotton bolls is likely a bollworm. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, C.; Meng, X.; Bai, B.; Qiu, H. CottonCapT6: A Multi-Task Image Captioning Framework for Cotton Disease and Pest Diagnosis Using CrossViT and T5. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 10668. https://doi.org/10.3390/app151910668

Zhao C, Meng X, Bai B, Qiu H. CottonCapT6: A Multi-Task Image Captioning Framework for Cotton Disease and Pest Diagnosis Using CrossViT and T5. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(19):10668. https://doi.org/10.3390/app151910668

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Chenzi, Xiaoyan Meng, Bing Bai, and Hao Qiu. 2025. "CottonCapT6: A Multi-Task Image Captioning Framework for Cotton Disease and Pest Diagnosis Using CrossViT and T5" Applied Sciences 15, no. 19: 10668. https://doi.org/10.3390/app151910668

APA StyleZhao, C., Meng, X., Bai, B., & Qiu, H. (2025). CottonCapT6: A Multi-Task Image Captioning Framework for Cotton Disease and Pest Diagnosis Using CrossViT and T5. Applied Sciences, 15(19), 10668. https://doi.org/10.3390/app151910668