Featured Application

Despite their great artistic value, illustrated herbals are a type of manuscript that has received little scholarly attention. This work demonstrates how an in situ contactless multi-analytical approach, combining digital techniques with spectroscopies, can provide valuable insights into the materials used. The results lay an important foundation for the study of this type of heritage.

Abstract

Codex 462 of the Fondo Hortus Pisanus of the Biblioteca Universitaria of Pisa is a precious example of a 16th century illustrated herbal, Icones variarum plantarum, containing 35 tempera paintings by the German soldier Georg Dyckman, an amateur but highly talented artist. The manuscript was recently restored on the occasion of an international exhibition; the necessary preliminary studies for the restoration included a series of in situ diagnostic studies using contactless techniques (digital microscope, multispectral imaging, XRF, Raman and ER-FTIR). These analyses proved useful in deepening the knowledge of the materials and the execution technique of this type of illustrated herbals and in choosing the most appropriate solutions during the restoration phase. In view of the growing interest in this type of historical evidence, which involves both art history and the history of science, this study offers an interesting new perspective on the subject, useful both from a technical point of view for future conservation and for analytical and historical artistic studies.

1. Introduction

An herbal is a book, used since ancient times, that collects descriptions of plants and their pharmacological properties, often with names in different languages and information about their habitat [1,2,3]. These books have evolved over time: illustrated herbals are painted herbals, also called horti picti, or herbaria before the Renaissance; they are different from the collections of dried plants, called horti sicci [4,5]. As early as the sixth century, images played a vital role in scientific texts, where text and illustrations were closely intertwined. During the thirteenth century, herbal illustrations emerged that relied more on images than text. This culminated in the creation of botanical atlases—‘illustrated books’ that contained no text whatsoever [6]. Codex 462 of the Fondo Hortus Pisanus of the Biblioteca Universitaria of Pisa is a precious example of a 16th century illustrated herbal, Icones variarum plantarum, containing 35 tempera paintings by the German soldier Georg Dyckman, an amateur but highly talented artist. Between 1590 and 1591, the Flemish botanist Joseph Goedenhuize (who had Italianised his name to Giuseppe Casabona or Benincasa) went to the island of Crete, famous for its rich variety of plants and herbs with multiple virtues. He was in the service of the Medici court as prefect of the Giardino dei Semplici, and his aim was to study new spontaneous species to enrich the Tuscan Garden. Dyckman’s artistic skill depicted various spontaneous plants of the island [7]. The plates describe species collected by Casabona himself and then sent to the Grand Duke’s court and show how botanical iconography had begun to favor images drawn from life. The work had a considerable impact on the scientific community of the time; among the spontaneous plants depicted are the Paeonia peregrina M., the Euphorbia spinosa L. and several specimens of Ranunculus asiaticus L., which only later spread to Italy [8]. The true value of this work is that it is an original artifact, setting it apart from other illustrated herbals. Illustrated herbals were complex and expensive to produce. This is reflected in their limited and specific use, which is also why so few were copied in the first place. For example, of the approximately 250 Greek medical papyri discovered in Egypt, only two were illustrated: the Tebtunis Scroll and the Antinoopolis Codex [6]. Even masterpieces like the Codex Aniciae Julianae (also known as the Vienna Dioscorides, the oldest illustrated copy of Dioscorides of Anazarbus’s De Matter Medica) are later copies, though they serve as a testament to the high botanical and medical value of the original texts [9].

For a recent exhibition dedicated to “Arcimboldo—Bassano-Bruegel—Nature’s Time”, held during 11 March–29 June 2025 at Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna [10], the codex underwent a restoration intervention aimed at dry cleaning, repairing tears and losses of the paper, consolidation of pigments and the restoration of the original XVI century binding. Prior to this, it was analyzed to determine the materials used and the condition of the media and the paper-based support. Several contactless techniques were employed for this purpose at the “Biblioteca Universitaria of Pisa”, where the codex is housed. Specifically, optical analysis was performed on a large scale using Multispectral Imaging (MSI) and on a detailed level using a digital optical microscope (DINO-lite). The support and painting materials were then studied using elemental techniques such as X-ray fluorescence (XRF) and molecular techniques such as Raman spectroscopy and Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR). Thanks to this multidisciplinary approach, the state of conservation of the object and artist’s painting technique could be identified. Despite the artist not being a professional, precious pigments were found to have been used.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Herbal

Codex 462 (see Figure S1 in Supplementary Materials) is a paper volume (440 × 294 mm; VIII, 27, VI cc) entitled Icones variarum plantarum. This work by Georg Dyckman contains 37 drawings: 35 in tempera, one in pencil (f. 26r) and one in pen (glued on f. 27r). Executed no earlier than 1590, it depicts botanical essences from Crete and the eastern Mediterranean. Blanc folii. II–VII, 1r, 2v, 3r, 4v, 5v, 6v, 7v, 8v, 9r, 11v, 17r, 18v, 22r, 23v, 25v, 26v, 27v, I–VI, where “r” and “v” mean, respectively, the recto (front) and the verso (back) of the folio. Handwritten notes listing the names of the species, probably written in a mid-17th-century hand [7], appear on almost all pages. Interestingly, in almost all the pages the botanical name is not always correct or up to date. Recently, researchers at the Botanical Garden of Pisa have verified and compared all the pages of the codex, associating each image with the correct botanical species according to the current scientific classification. The codex has a coeval limp vellum binding with traces of two deteriorated green linen ties. The Medici grand-ducal coat of arms in iron and gold appears in the center of the front cover. Originally from the Library of the Giardino dei Semplici in Pisa [11,12], the codex is currently held at the Biblioteca Universitaria of Pisa (inventory number # 349624).

2.2. The MSI Camera

For the MSI analysis, a system equipped with a high-resolution Moravian G2-8300 camera (Moravian Instruments, CZ-763 02 Zlin 4, Czech Republic) (CCD detector KAF-8300, imaging area 18.1 × 13.7 mm, pixel size 5.4 × 5.4 μm). The camera has a dynamic range of 16 bits. The sensor was cooled to minimize electronic noise during the acquisition process. Spectral resolution is obtained through the use of an interferential filter with a bandpass of ±25 nm around the central wavelengths of 400, 450, 500, 550, 600 and 650 nm within the visible spectrum. The same applies to wavelengths of 850, 950 and 1050 nm in the near-infrared range. The exposure and focusing characteristics were optimized for each band. The same lighting conditions were maintained for the visible and infrared image sequences. The diaphragm aperture was set to f/8 for all acquisitions.

2.3. Digital Optical Microscopy

Digital optical microscopy (Dino-Lite Europe, 1321 NN Almere, The Netherlands), both under visible light (Dino-Lite AM7915MZT) and UV fluorescence (Dino-Lite 400 nm + white), was performed by using a Dino-Lite digital microscope.

2.4. XRF Spectroscopy

X-ray fluorescence measurements were taken using a portable energy-dispersive X-ray fluorescence (ED-XRF) device, ELIO, manufactured by Bruker (Bruker Nano GmbH, 12489 Berlin, Germany). The instrument has an X-ray tube (50 keV, 300 mA max), a 1 mm collimator, a Rh anode and a large-area silicon drift detector with a resolution of 130 eV at the Mn Kα line energy. The measurement conditions were 90 s acquisition time, energy 40 keV and current 80 μA.

2.5. Raman Spectroscopy

The in situ micro-Raman measurements were performed using a B&W Tek Raman Plus instrument (B&W Tek, Newark, DE, 19713, USA). The radiation was at 785 nm. The instrument acquires the Raman spectrum between 80 and 3350 cm−1 with a resolution better than 3.5 cm−1. The laser power used during the measurements was set to a few milliwatts (less than 0.2 mW) to prevent pigment photodecomposition. Typical acquisition times were three accumulations with 10 s exposure times.

2.6. External Infrared Spectroscopy

External reflection infrared spectra (ER-FTIR) were collected using an Alpha Bruker portable spectrometer (Bruker Nano GmbH, 12489 Berlin, Germany) equipped with an external reflection module. Each spectrum was acquired within the 7000−375 cm−1 range, with 160 scans and resolution of 4 cm−1. The investigated area was approximately 20 mm2. No correction, except for a line smoothing and a normalization, was applied to the resulting spectra.

3. Results and Discussion

Adopting a multidisciplinary approach enabled us to gather useful information on the works under examination in a complementary manner. To make the results easier to understand, we organized the discussion by first reporting on the support and state of preservation, then on the multispectral imaging, and finally on the identification of the painting materials (pigments and binders).

3.1. Support Characterization and State of Conservation

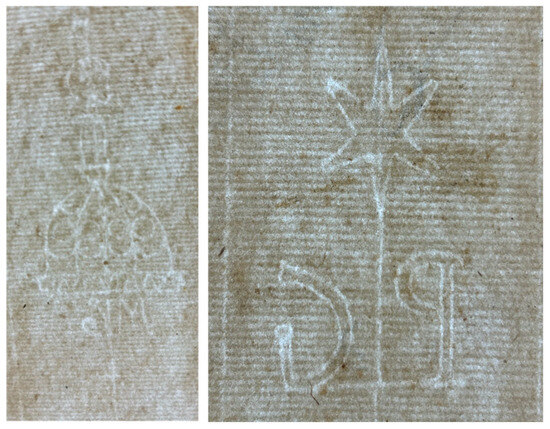

First, the codex was examined to assess its conservation condition. The handmade paper features watermarks characteristic of 16th-century North Europe paper manufacturing [13]. They became a distinctive feature of the paper, only becoming visible when held up to the light. They often displayed a variety of motifs, such as factory marks, regional symbols, and paper factory marks. The most common of these were pictorial, featuring factory monograms, national symbols, initials, surnames and place names. In the manuscript (Ms) 462, for example, the initials ‘G’ and ‘P’ can be seen alongside decorative elements (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Two watermarks identified in the paper are visible when backlit.

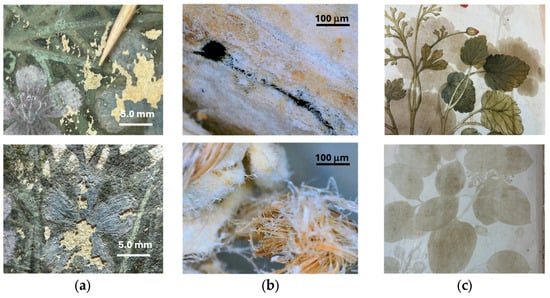

The conservation state is generally good; however, a careful analysis revealed flaking pigment and losses in the paint layer on some pages, most likely caused by poor adhesion (Figure 2a), whereas the support showed breakage of the sewing support cord and tears in the parchment cover (Figure 2b). Moreover, oxidation and localized color transfer on the verso of the page were observed in few pages (Figure 2c).

Figure 2.

Details of the Codex 462, showing different conservation issues: (a) Flaking pigment and losses; (b) unraveled points in the binding; (c) oxidation.

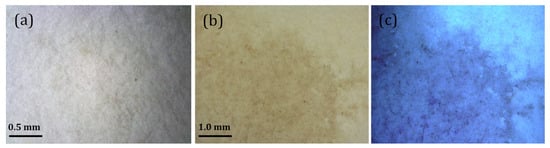

Digital optical microscopy analyses reveal an irregular paper texture, as depicted in Figure 3, with small fibers and particles creating an opaque and slightly porous appearance. The non-uniform distribution of the fibers creates a porous and rough texture, with small cavities and imperfections on the surface. The texture shows slight color variations, ranging from light beige to brown, due to the different density and orientation of the fibers in the raw paper. In some spots, darker stains can be observed (Figure 3b), probably formed on the paper as a result of aging through foxing processes. The observation under UV light (Figure 3c) of the stained areas reveals a bright fluorescence in the unstained areas, which is typical of cellulose and clearly reveals its fibrous structure. On the other hand, the stained areas appear darker, with reduced fluorescence. This difference in fluorescence between the stained and unstained areas suggests that the paper material has undergone a chemical alteration in the zones where the stain is present [14].

Figure 3.

Digital optical microscopy (OM) images captured under various conditions: (a) clean paper under visible light (70×), (b) brown spot under visible light, and (c) UV-induced fluorescence of the (b) image (54×). All the analyzed areas belong all to folio 21r.

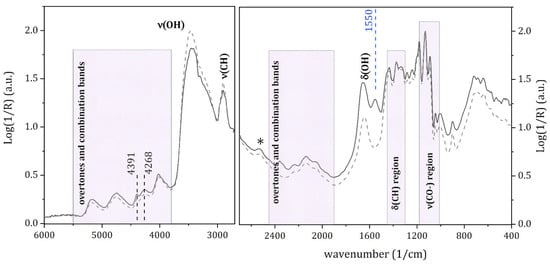

The ER-FTIR spectrum collected on paper shows the typical absorptions of cellulose, as illustrated in Figure 4, together with overtones and combination bands enhanced by the diffuse reflection. These signals are clearly observable in the NIR region and in the 2450–1900 cm−1 range. More particularly, the NIR region of cellulose typically exhibits first overtones of ν(OH), combination bands involving ν(OH) and ν(CH) and/or ν(CH) and δ(CH), possible second overtones of C-H stretching towards the higher wavenumbers, and combination bands involving O-H stretching and O-H deformation. For instance, according to literature [15,16], the distinctive absorption due to ν(OH) + ν(CH) is clearly detectable at ≈4391 cm−1, together with the one due to ν(CH) + δ(CH) and/or 2nd δ(CH) overtone at ≈4268 cm−1. In the 2450–1900 cm−1 region, cellulose exhibits combination bands primarily arising from C-H deformations combined with C-O or C-C stretching, O-H deformations combined with various skeletal stretching and bending modes, and possibly combinations of glucopyranose ring vibrational modes.

Figure 4.

ER-FTIR spectra collected on paper, acquired on folio 21r compared with those of the reference cellulose (dotted line). The * indicates the calcite combination band. The distinctive combination bands of cellulose together with the aromatic skeletal vibrations of lignin are indicated according to their attributions.

In addition, the weak signal at ≈2512 cm−1 can be assigned to the ν1 + ν4 of CO3= group in calcite [17], used as inorganic filler in paper [18]. It is interesting to note that the spectrum collected on the paper shows a clear absorption at ≈1550 cm−1 not ascribable to cellulose main vibrational modes. Based on the literature [19,20], this signal can be tentatively assigned to aromatic skeletal vibrations in lignin, a residue from the extraction of cellulose from wood. Moreover, a detailed observation of the δ(OH) of the absorbed water, ≈1640 cm−1, reveals the presence of few inflection points between 1800 and 1700 cm−1. To better highlight these inflection points, the 2nd derivative was applied (see Figure S2 in Supplementary Materials). This revealed superimposed signals attributable to ν(C=O) contributions, which can be related to the hydrolysis of hemiacetal bonds in cellulose, pointing out the presence of cellulose degradation products [21].

3.2. Multispectral Acquisitions

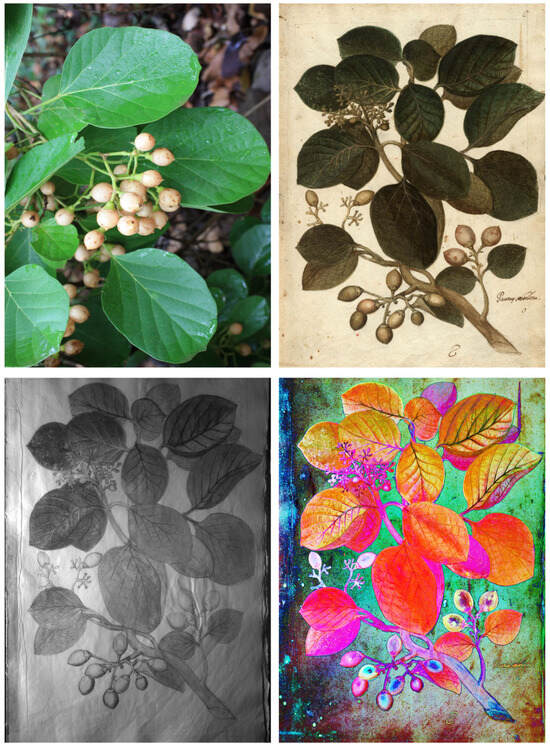

The MSI technique was used to analyze four herbal pages (8r, 12r, 18r and 21r). A multispectral set of nine images was acquired for each page and the resulting datasets were processed using advanced statistical methods, including the Chromatic Derivative Imaging (ChromaDI) method [22]. In this approach, the absolute value of the differences between the four images (IR–R, R–G, and G–B) is displayed in the R, G, and B channels, respectively. Here, IR stands for infrared (filter centered at 1050 nm), R for red (filtered at 650 nm), G for green (filtered at 550 nm) and B for blue (filtered at 450 nm). As the spectral width of the acquired band remains constant, it is possible to calculate an incremental ratio similar to a derivative. This processing technique has proven useful in highlighting the presence of color clusters or tone variations [23,24], particularly beneficial to perform the following punctual analysis (XRF, Raman, ER-FTIR) aimed at identifying the pigments. Figure 5 shows the results obtained on folio 8r, whereas the other MSI acquisitions are reported in the Supplementary Materials (Figures S3–S5). The MSI images are compared with a photograph of the botanical species in question (top left in Figure 5 and Figures S3–S5). Comparing this photograph with Dyckman’s drawing highlights the skill and attention to detail with which he depicted the plant.

Figure 5.

Starting from the top and proceeding clockwise, the photos of the botanical species Cordia myxa L., followed by RGB processing, IR acquisition, and ChromaDI processing of Folio 8r (r = recto).

In these pages, the analysis documents the presence of a preparatory drawing visible in the IR acquisition at 1050 nm revealing the artist’s original sketch (bottom right in Figure 5 and Figures S3–S5), which indicates a meticulous attention to detail.

ChromaDI processed images (bottom left in Figure 5 and Figures S3–S5) tend to highlight in different tones the possible use of multiple color shades that could have been used by the artist to render the plants under examination as realistically as possible. For instance, in the case of Cordia myxa L. species in folio 8r, the ChromaDI elaboration clearly shows the level of detail involved in creating the different shades of the plant’s particulars, such as the small white fruits in the bottom right-hand side. This drupe ranges, in fact, in color from light brown to tan or pink [25]. Moreover, this type of imaging processing allows to highlight the possible presence of biological attack; for instance, in the case of folio 8r the bright spots on the left-hand side of the foil that may be associated with the presence of mold. The contrast between the original sheet and book binding material is also evident (the left border of the folio in bluish shades). Similar observations can be performed for the other acquired folii. For instance, the various shades of green in the Ranunculus asiaticus L. leaves (see Figure S5) appear as different colors in ChromaDi. Similarly, the Malva arborea flower (Figure S4) has a high level of detail, which is unfortunately somewhat lost in the RGB image. The same applies to the Cichorium spinosum L. flowers (see Figure S3), which initially appear quite similar in RGB, but reveal a variety of nuances in the processed image.

3.3. Painted Areas: Binder and Pigment Identification

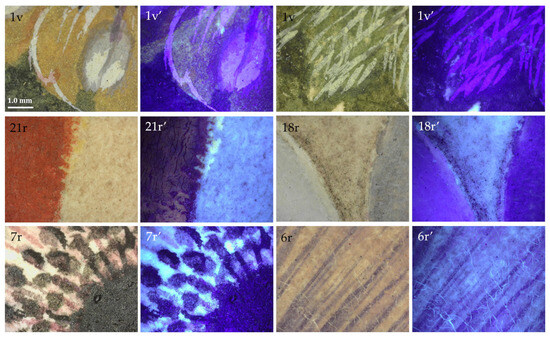

In general, the colored areas show, regardless of the color used, both a grainy and irregular texture, as well as smooth and homogeneous surfaces, as illustrated by digital optical microscopy images (Figure 6 and Figure S6 in Supplementary Materials). The first evidence could be related to the thick application of pigment or painting medium. Conversely, the second could indicate a thinner and more uniform application. This evidence is highlighted by the UV fluorescence digital microscopy images reported in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Visible light and UV fluorescence digital microscopy images (54×) of selected details. Each image is labeled with the folio number, specifying recto (r) or verso (v). Prime symbols (’) indicate images captured under UV fluorescence.

Numerous pigment particles are observed, unevenly dispersed within the paint binder. Their distribution creates a grainy and porous texture on the surface. Also, the streaks are enhanced, likely resulting from the color application technique and the direction of the brushstrokes. The brighter areas indicate a higher concentration of fluorescent compounds, attributable to the paint binder and/or cellulose.

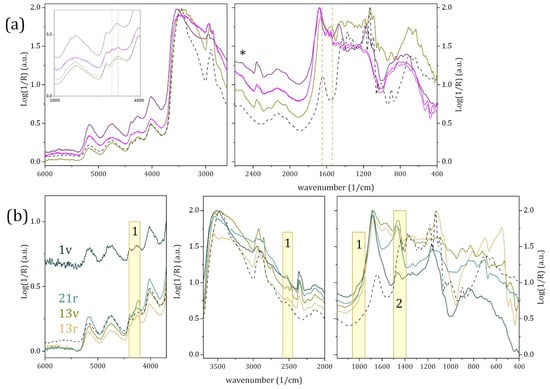

The ER-FTIR spectra collected from various colored areas all show considerable complexity, primarily due to spectral distortions induced by the simultaneous detection of reflected and diffused radiation. The obtained spectra can be classified into two main groups: the first characterized by more pronounced absorptions of the binder, the second dominated by signals from inorganic pigments. The spectra collected from purple, brown and pink areas belong to the first group, while those from green areas fall into the second. The spectra of the former group show the typical signals attributable to a proteinaceous binder namely, according to literature [26]: the amide I and II absorptions, at 1650 and 1540 cm−1 respectively, and the ν(CH) + δ(CH) combination bands, at 4430 and 4260 cm−1, as illustrated in Figure 7a.

Figure 7.

ER-FTIR spectra collected on: (a) purple, brown, and pink areas; (b) green areas. Orange dotted lines represent characteristic absorption and combination bands of proteinaceous materials. The asterisk (*) indicates the calcite combination band. Pale green areas represent regions where basic copper carbonate overtones and/or combination bands fall: (1) basic copper carbonate overtones, (2) basic copper carbonate combination bands. The black dashed line represents the reference cellulose. The folio numbers where the spectra were acquired are indicated next to each spectrum.

In addition to the signals due to the proteinaceous binder, a weak signal at ≈2512 cm−1 is clearly observable in all analyzed areas, tentatively attributable to the ν1 + ν3 combination band of the CO3= group in calcite. Since this signal is also present in the spectra collected from the support, as mentioned in the previous paragraph, it is presumable that it originates from the calcite contained in the paper rather than from the use of “Bianco di San Giovanni” in the paint layer. The spectra collected on the green areas exhibit the typical absorption of basic copper carbonate (i.e., malachite and azurite): the fundamental vibrational mode ν3—together with the overtones and combination bands 3ν3 and ν + δ(OH), ν1 + ν3 and/or 2ν2 + ν4 and ν1 + ν4 of CO3=, as reported in Figure 7b. An unambiguous assignment is very difficult, as these signals overlap with absorptions from the binder and other components of the paint layer. As can be clearly seen from the digital optical images acquired (Figure S5), the mixing of green and blue pigments was adopted to obtain dark green-bluish hue.

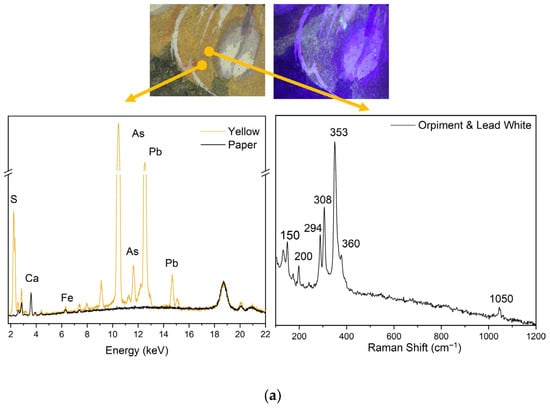

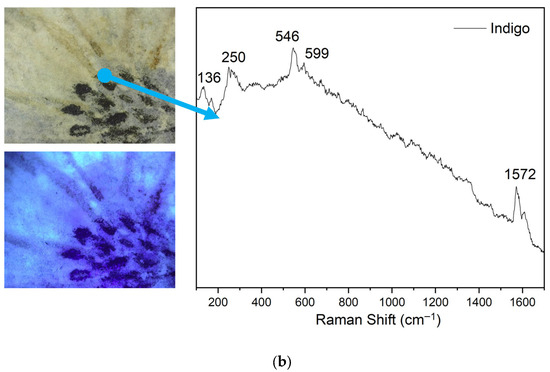

However, in terms of pigment identification, combining complementary techniques enabled us to identify or confirm the presence of a wide range of pigments, some of which were of great value, such as Vermillion, Ultramarine and Orpiment. This suggests that, despite the artist being an amateur, the commissioned work was considered to be of great importance. The intention was to create a significant piece of artwork and not only to document the collected plants. The obtained results are summarized in Table 1. Figure 8 and Figure S7 report some of the realized XRF and Raman measurements: in particular, Figure 8a shows a comparison of the XRF spectra acquired from a yellow area (a detail of a flower petal) and the undepicted paper support. The lines for sulfur (S), arsenic (As) and lead (Pb) are significantly more intense. A Raman spectrum acquired from the same area confirms the presence of orpiment (As2S3) and white lead (PbCO3) [27]. Figure 8b shows the Raman spectrum obtained from a flower pistil. The characteristic indigo (C16H10N2O2) bands are clearly visible [28].

Table 1.

List of the identified pigments in the Ms 462.

Figure 8.

XRF and Raman spectra taken on Ms 462: (a) Folio 1 versus detail macro RGB and UV fluorescence images of a yellow spot; (b) Folio 7 recto detail macro RGB and UV fluorescence images of a blue spot.

4. Conclusions

From the outset, illustrated herbals were primarily conceived as visual resources. This particular type of reference work reinforced information typically obtained through writing or direct experience. During the late medieval and early modern periods, they became an increasingly important scientific tool, facilitating memorization and research while enabling the creation of idealized visualizations that abstracted botanical variability. This paper presents the key findings of the study of Ms 462, an exceptional example of hortus pictus, a painted herbal. Observations using a digital optical microscope revealed the artist’s meticulous attention to detail. Multispectral imaging confirms this expertise and suggests that a detailed preparatory drawing was used to create the pictures. Chemical and physical analyses revealed a diverse palette of pigments, some of which are characteristic of illuminated manuscripts, thereby enhancing the work’s value. The presence of a proteinaceous binder lends weight to the tempera hypothesis. The analyses also highlighted several conservation issues that are important for the work’s proper preservation. These results represent a significant advancement in the study of this type of artwork. While it is part of the library’s collection, its unique characteristics distinguish it from more renowned illuminated manuscripts. This information will be invaluable for future comparisons with similar works not yet enough investigated.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/app151910626/s1, Figure S1: Photograph of the front cover of the manuscript; Figure S2: 2nd derivative was applied in the 1800–1400 cm−1 range on the ER-FTIR spectrum of paper. Signals of oxidation products were identified in the 1750–1700 cm−1 range. Moreover, the broad absorption at 1550 cm−1, can be tentatively ascribed to the superimposition of ν(C=O) lignin signals; Figure S3: Starting from the top and proceeding clockwise, the photos of the botanical species Malva arborea L., followed by RGB processing, IR acquisition, and ChromaDI processing of pag 12v; Figure S4: Starting from the top and proceeding clockwise, the photos of the botanical species Cichorium spinosum L. (asteraceae), followed by RGB processing, IR acquisition, and ChromaDI processing of pag 18r; Figure S5: Starting from the top and proceeding clockwise, the photos of the botanical species Ranunculus asiaticus L. (Ranuncolaceae), followed by RGB processing, IR acquisition, and ChromaDI processing of pag 21r. Figure S6: digital optical images (70×) of yellow, red and purple flowers, green leaves; Figure S7: Raman (a–f) and XRF (g,h) spectra acquired on different colored spots. Each image is labeled with the folio number, specifying recto (r) or verso (v). Numerous pigment particles can be observed, unevenly dispersed within the paint binder. The distribution of pigment particles creates a grainy and porous texture on the sur-face. Also, the streaks are enhanced, they are probably due to the color application technique and the direction of the brushstrokes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.G., S.L. and P.T.; methodology, C.G., S.L., L.N. and P.T.; software, S.L., G.L., L.N., V.P. and P.T.; validation, C.G., S.L. and P.T.; formal analysis, S.L., G.L., L.N., V.P. and P.T.; investigation, C.G., S.L., G.L., L.N., and P.T.; resources, S.L. and P.T.; data curation, S.L., G.L., L.N., V.P. and P.T.; writing—original draft preparation, C.G., S.L., G.L., L.N., and P.T.; writing—review and editing, C.G., S.L., G.L., L.N., V.P. and P.T.; visualization, S.L., G.L., L.N., V.P. and P.T.; supervision, S.L. and P.T.; project administration, C.G., S.L. and P.T.; funding acquisition S.L. and P.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data are available upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the staff of Biblioteca Universitaria of Pisa for their valuable collaboration.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MSI | Multispectral Imaging |

| XRF | X-ray fluorescence |

| ER-FTIR | External Reflection Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy |

| CCD | Charge coupled device |

| Ms | Manuscript |

| r/v | Recto/verso |

| ChromaDI | Chromatic Derivative Imaging |

References

- Anderson, F.J. An Illustrated History of The Herbals; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, M. Medieval Herbals: The Illustrative Traditions; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana. Natural history illustrations in Michael Boym’s Chinese atlas (Borg. cin. 531) and Flora Sinensis/Csillag, Eszter. In Miscellanea Bibliothecae Apostolicae Vaticanae XXVI; Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana: Cortile del Belvedere, Vatican City, 2020; pp. 115–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasi, T.L. The Renaissance Herbal; The New York Botanical Garden: Bronx, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Back, P. The Illustrated Herbal; Frances Lincoln: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Griebeler, A. Production and design of early illustrated herbals. Word Image 2022, 38, 104–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasi, T.L.; Hirchauer, G. The Flowering of Florence: Botanical Art for the Medici; The National Gallery of Art: Washington, DC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Galasso, G.; Conti, F.; Peruzzi, L.; Ardenghi, N.M.G.; Banfi, E.; Grapow, L.C.; Albano, A.; Alessandrini, A.; Bacchetta, G.; Ballelli, S.; et al. An updated checklist of the vascular flora alien to Italy. Plant Biosyst. Int. J. Deal. All Asp. Plant Biol. 2018, 152, 556–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janick, J.; Stolarczyk, J. Ancient Greek Illustrated Dioscoridean Herbals: Origins and Impact of the Juliana Anicia Codex and the Codex Neopolitanus. Not. Bot. Horti Agrobot. Cluj-Napoca 2012, 40, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kunst Historisches Museum—Arcimboldo—Bassano—Bruegel, Nature’s Time Exhibition, 11 March–29 June 2025. Available online: https://www.khm.at/en/exhibitions/arcimboldo-bassano-bruegel (accessed on 5 August 2025).[Green Version]

- Inventario della Galleria e del Giardino dei Semplici di S.A.S. in Pisa. ASP, Università, 531, 5, cc. 31-32 e sgg. Available online: https://www.internetculturale.it/it/16/search/detail?instance=&case=&id=oai%3Awww.internetculturale.sbn.it%2FTeca%3A20%3ANT0000%3AIT-PI112_MS.HORTUS_PISANUS.462&qt= (accessed on 1 February 2025).[Green Version]

- Sbrana, C. Per una ricostruzione dell’antica biblioteca del Giardino dei Semplici di Pisa. Nuovi elementi. Physis Riv. Internazionale Stor. Della Sci. 1982, 24, 423–434. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Xiaojie, X. Regional Characteristics of 16th- and 17th-Century European Printing Paper. In Paper Stories—Paper and Book History in Early Modern Europe; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, M.; Relvas, C.; Figueira, F.; Campelo, J.; Candeias, A.; Caldeira, A.T.; Ferreira, T. Analytical and Microbiological Characterization of Paper Samples Ex-hibiting Foxing Stains. Microsc. Microanal. 2015, 21, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, F.; Altaner, C.M. Molecular deformation of wood and cellulose studied by near infrared spectroscopy. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 197, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, M.; Emsley, A.M.; Herman, H.; Heywood, R.J. Spectroscopic studies of the ageing of cellulosic paper. Polymer 2001, 42, 2893–2900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miliani, C.; Rosi, F.; Daveri, A.; Brunetti, B.G. Reflection infrared spectroscopy for the non-invasive in situ study of artists’ pigments. Appl. Phys. A 2012, 106, 295–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gettens, R.J.; Fitzhugh, E.W.; Feller, R.L. Calcium carbonate whites. Stud. Conserv. 1974, 19, 157–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukir, A.; Hajji, L.; Zghari, B. Effect of moist and dry heat weathering conditions on cellulose degradation of historical manuscripts exposed to accelerated ageing: 13C NMR and FTIR spectroscopy as a non-invasive monitoring approach. J. Mater. Environ. Sci. 2018, 9, 641–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamburini, D.; Łucejko, J.J.; Zborowska, M.; Modugno, F.; Cantisani, E.; Mamoňová, M.; Colombini, M.P. The short-term degradation of cellulosic pulp in lake water and peat soil: A multi-analytical study from the micro to the molecular level. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2017, 116, 243–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łojewska, J.; Miśkowiec, P.; Łojewski, T.; Proniewicz, L.M. Cellulose oxidative and hydrolytic degradation: In situ FTIR approach. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2005, 88, 512–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legnaioli, S.; Lorenzetti, G.; Cavalcanti, G.H.; Grifoni, E.; Marras, L.; Tonazzini, A.; Salerno, E.; Pallecchi, P.; Giachi, G.; Palleschi, V. Recovery of Archaeological Wall Paintings Using Novel Multispectral Imaging Approaches. Herit. Sci. 2013, 1, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuena, M.; Buemi, L.P.; Nodari, L.; Subelytė, G.; Stringari, L.; Campanella, B.; Lorenzetti, G.; Palleschi, V.; Tomasin, P.; Legnaioli, S. Portrait of an artist at work: Exploring Max Ernst’s surrealist techniques. Herit. Sci. 2022, 10, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poggialini, F.; Campanella, B.; Giostrella, C.; Lorenzetti, G.; Palleschi, V.; Raneri, S.; Legnaioli, S. Non-Invasive Investigation of 19th-Century Photographs: Enrico Van Lint’s Historical Collection in Pisa. Heritage 2025, 8, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, F.; Abbate, G.; Alessandrini, A.; Blasi, C. An Annotated Checklist of the Italian Vascular Flora; Palombi Editore: Roma, Italy, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Nodari, L.; Ricciardi, P. Non-invasive identification of paint binders in illuminated manuscripts by ER-FTIR spectroscopy: A systematic study of the influence of different pigments on the binders’ char-acteristic spectral features. Herit. Sci. 2019, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgio, L.; Clark, R.J.H. Library of FT-Raman spectra of pigments, minerals, pigment media and varnishes, and supplement to existing library of Raman spectra of pigments with visible excitation. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2001, 57, 1491–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandenabeele, P.; Moens, L. Micro-Raman spectroscopy of natural and synthetic indigo samples. Analyst 2003, 128, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).