Abstract

The transition to a net-zero economy requires a shift towards circular economy principles, particularly within the burgeoning electric vehicle sector. This paper presents a systematic literature review of 57 studies published between 2017 and the end of August 2025, examining methodologies for assessing the circularity of electric vehicles. The analysis reveals a predominant focus on environmental impact quantification through life cycle assessment and material flow analysis, with limited direct application of tailored circularity assessment tools. A significant knowledge gap is identified in the integration of environmental, economic, and social dimensions within electric vehicle circularity assessments. Furthermore, the absence of electric vehicle-specific assessment tools and the challenges associated with data reliability and indicator measurement are highlighted. The paper proposes the adoption of digital product passports and a dynamic systems view to enhance electric vehicle circularity assessments. This approach aims to provide a more comprehensive, multidisciplinary understanding of electric vehicle lifecycle impacts, facilitating informed decision-making for sustainable e-mobility.

1. Introduction

The transportation sector is undergoing a transition, increasingly adopting electric vehicles (EVs) over internal combustion engine vehicles to mitigate greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions associated with gasoline or diesel combustion [1]. Driven by the European Union’s (EU) ambitious policy targets, including net-zero by 2050 [2], at least 30 million electric vehicles (EVs) are expected to be in operation across the EU by 2030 [3]. The increasing global demand for lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) is projected to create a substantial volume of end-of-life (EoL) LIBs. This occurs when the nominal capacity of an LIB degrades to 80% of its original capacity [4]. The scale of this challenge is significant, with projections estimating that the total capacity of these EoL batteries will reach 185 GWh by 2030 [1]. Furthermore, the availability of raw materials essential for battery production is limited, and Europe is reliant on global supply chains for these crucial resources [5]. Another significant drawback of electric vehicles (EVs) is that the manufacturing process for producing their batteries requires substantial energy input [3].

Shifting from a linear “end-of-life” model, the circular economy (CE) emphasizes reducing, reusing, recycling, and recovering materials and energy across production, distribution, and consumption [6]. While often considered a modern concept, the CE has roots in Kenneth Boulding’s 1966 “closed economy” idea [7]. Although “more circular” is frequently equated with “more sustainable,” the CE definition remains ambiguous, complicating efforts to identify appropriate metrics [7]. According to [8], when adopting a practices- and paths-based approach to CE, environmental indicators and targets are essential, alongside a thorough analysis of circularity indicators, to ensure the economy becomes not only circular but also sustainable.

In the context of EVs, circularity has been increasingly defined with a focus on the unique characteristics of battery systems and their material intensity. Some studies [1,9,10] emphasize the importance of extending the life of lithium-ion batteries through reuse and repurposing, including second-life applications, before they enter recycling pathways. Refs. [3,5,11] build on this by framing circularity as the integration of design, use, and end-of-life strategies to minimize environmental impacts across the battery life cycle. Complementing these views, refs. [4,12] highlight the role of systemic strategies for raw material recovery from end-of-life batteries to reduce dependence on virgin resources and enable closed-loop supply chains.

The drivers for the adoption of CE can be grouped into several categories: political and economic advantages, social progress, environmental issues and resource depletion, regulatory obligations, self-realization, and market and competition (e.g., addressing the demands and expectations of stakeholders such as customers) [13]. Some researchers have examined the differences, similarities, and interrelations among the concepts of CE, sustainability, and sustainable development [13]. CE can be viewed as a method or a primary strategy for achieving sustainable development; however, when it comes to assessment methodologies, CE and sustainability indicators sometimes overlap [13].

A successful transition to the CE requires the ability to measure and report progress, which is essential for effective planning and continuous improvement [13]. Therefore, tools that facilitate the measurement of CE are crucial to ensure that the circular strategies and practices implemented in a specific context yield positive environmental outcomes, ultimately resulting in greater benefits than negative impacts [14]. The primary advantages of measuring CE include reduced environmental impacts, cost savings, enhanced external communication and collaboration—such as improved marketing and reputation among stakeholders and fostering positive relationships with customers—as well as internal benefits like facilitating learning processes and cultural shifts among employees, identifying new opportunities, and easier access to funding [13].

The growing interest in developing recycling technologies for lithium-ion battery (LIB) production within the mineral processing industry has led to advancements in new, more environmentally conscious recycling options [12]. However, the successful implementation of these technologies depends on the ability of recycled materials to demonstrate comparable or superior properties to their non-recycled counterparts, while also ensuring that the environmental damage associated with the recycling process does not exceed its benefits [12]. Furthermore, despite progress in mining and extraction technologies, the associated waste can result in significant environmental issues, including surface water contamination, toxic gas emissions, excessive energy consumption, and ecosystem degradation or landscape damage [12]. It is also important to note that increased circularity does not always equate to improvements in environmental sustainability [3]. Consequently, decisions regarding battery eco-design must be guided by robust and holistic analytical tools and indicators. These tools can assist industrial designers and manufacturers in making the most circular and environmentally sustainable choices on a case-by-case basis, taking an integrated life cycle perspective into account and considering potential trade-offs [3]. Applying CE principles to EV batteries not only tackles their current challenges but also alleviates the increasing demand for energy storage systems (ESS) by facilitating battery reuse in ESS applications [9].

Some studies differentiate assessment measurements into categories like circularity indicators, metrics, indices, and tools. For example, an “indicator” is a single, measurable value (quantitative or qualitative) reflecting progress or change, representing the smallest unit of information assessed under a CE goal, standard, or principal category (e.g., “total renewable energy consumed within the company”) [13]. However, this review includes all studies related to measuring any aspect of circularity or environmental impact within the EV field, aiming to provide a comprehensive literature review.

Recent research efforts have increasingly focused on applying CE strategies to EVs, with a particular emphasis on creating more sustainable practices for end-of-life (EoL) management. These strategies encompass various options, including advanced battery recycling, reusing batteries in secondary applications such as grid-scale energy storage, and detailed studies of battery state of health (SOH). Central to these efforts is the growing need to accurately quantify the circularity of EV batteries. This measurement relies on a range of key performance indicators to evaluate how well a system performs regarding resource use, waste reduction, and the overall lifespan of materials and products. Methodologies like Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) and Material Flow Analysis (MFA) are frequently used as tools to measure the impact of different designs and approaches. What is particularly notable in this context is the expanding scope of circularity measurement. Instead of limiting these evaluations to end-of-life processes, researchers are increasingly examining the design and manufacturing phases of the battery itself. This ensures that CE principles are not merely an afterthought but rather are integrated into the core architecture of the battery from the beginning.

From 2019 onwards, a considerable number of studies have investigated the circularity of EVs. Some studies have adapted existing assessment tools for different aspects of this analysis, while others have sought to develop novel tools specifically designed for the purpose. This review seeks to provide a comprehensive overview of the academic research conducted so far on measuring circularity in EVs, spanning their entire lifecycle from the extraction of raw materials to the final reuse or recycling stage. Accordingly, many literature review papers have emerged during the past few years that attempted to review the contribution of CE principals in the EV domain. A few of them focused on reviewing circularity assessment tool studies on EV. Table 1 provides an overview of the previously published literature review articles related to the circularity assessment analysis of electric vehicle domain.

Table 1.

An overview of the previously published literature review articles related to the circularity assessment analysis of the electric vehicle domain.

The literature reviews summarized in Table 1 revealed several key findings. Earlier studies generally took a broad approach, evaluating circularity assessment tools across various product categories, including those beyond the EV sector. For example, ref. [15] assessed LCA tools in diverse applications like rare earth elements, and reviewed research areas such as affiliations, countries, journals, and authors in the context of rare earth elements management. Ref. [5] concentrated on LCA challenges for EV batteries within the context of circular economy strategies, assessing existing LCA guidelines for addressing multifunctionality, material quality, and resource depletion and availability issues. Furthermore, Ref. [16] conducted a broad review of electronic waste, not limited to electric vehicles, and included both life cycle assessment and techno-economic assessment within its scope.

Two studies among the papers [11,17] specifically focused on reviewing sustainability assessments of EVs. Ref. [17] included sustainability assessment along with life cycle assessment in their keyword selection, and adopted a broad perspective, encompassing environmental, economic, and social sustainability aspects, and analyzed studies by classifying them by sustainability indicators, life cycle approaches, phases, data sources, regions, and vehicle technology and class. Ref. [11] focused on EV batteries, analyzing common CE strategies like recycling, reuse, and remanufacturing in LCA studies. They categorized environmental impacts in different LCA models and discussed challenges and best practices for the LCA of CE management strategies applicable to EV batteries.

Previous reviews have approached circularity from broader perspectives rather than concentrating specifically on electric vehicles. For example, some studies examined circularity assessment across diverse product domains beyond the EV sector [15,16], while others explored general circular economy concepts without a dedicated focus on CE assessment [11]. Even when EVs were considered, the scope was often limited: ref. [11] analyzed only EV batteries rather than the whole vehicle, Ref. [5] focused on standards and methodological challenges in applying LCA to EVs, and Ref. [17] reviewed LCA studies on lithium-ion batteries, discussing their scope and findings but without addressing circularity methodologies more broadly. In addition, these reviews primarily covered studies published only up to 2023. Collectively, this indicates that no systematic effort has been made to investigate methodologies and purposes of circularity assessment specifically within the EV domain.

The novelty of this paper lies in addressing this gap by exclusively focusing on measuring circularity in electric vehicles across the entire lifecycle—from raw material extraction to end-of-life reuse and recycling. This study systematically synthesizes existing methodologies dedicated to EV circularity measurement and critically evaluates the objectives they are designed to achieve. By narrowing the focus to product-level applications within the EV sector, the review offers a targeted and sector-specific perspective that has been largely absent in the literature, while also providing a methodologically comprehensive understanding of how circularity is assessed in practice.

This study provides a detailed examination of published articles from 2017 through the end of August 2025, focusing on the measurement and assessment of circularity within the electric vehicle domain. Accordingly, this literature review contributes to the research domain by:

- (1)

- providing a detailed analysis of all methodologies used in academic articles to measure or assess various aspects of circularity related to EVs;

- (2)

- highlighting the primary purpose of these measurements by categorizing both quantitative and qualitative methodologies, and

- (3)

- Identifying research gaps that offer potential for future advancements in measuring EV circularity.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 outlines the research design. Section 3 presents the descriptive and content analysis findings. Section 4 provides insights into the identified research gap and offers recommendations for future research. Finally, Section 5 summarizes the conclusions.

2. Research Design

2.1. Research Questions

Quantifying circularity is crucial for effective policy and business strategies [8,18]. As the phrase ‘you cannot manage what is not measured’ suggests, robust indicators are essential for guiding circularity efforts [8]. This requires measurement tools and the use of CE assessment concepts such as indicators, metrics, and indices, which provide valuable data for decision-making [13]. An indicator is typically defined as a single value (quantitative or qualitative) that assesses progress or change [13]. A comprehensive study of 38 circularity assessment tools is presented in [13], categorizing them based on features such as application level, sector specificity, unit of measurement, main purpose, stakeholders’ engagement, social dimension, and industrial symbiosis. Their review revealed diversity among CE assessment tools in terms of methodology, set of indicators, formulas for calculating the indicators, units of measurement, and main purpose of the assessment [13]. Examples of widely applied tools include the Material Circularity Indicator (MCI), circularity calculator, and circular economy toolkit [13].

Robust analytical tools and indicators are essential for making informed eco-design decisions in battery production. These tools guide industrial designers and manufacturers towards the most circular and environmentally sustainable choices by considering life cycle impacts and potential trade-offs [3]. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) is a widely used methodology for quantifying the environmental impacts of a product throughout its entire lifecycle, from raw material extraction to end-of-life disposal [3]. This approach encompasses all stages of the product’s journey, including mining, processing [3], transportation, use, and recycling. This review encompasses studies related to measuring any aspect of circularity or environmental impacts within the EV domain. In this context, the following unique research questions are proposed.

Research Question 1 (RQ1): What are the most effective methodologies for assessing the circularity performance of EVs and their components across the entire product lifecycle? (answered in Section 3.2.1).

Research Question 2 (RQ2): What are the primary objectives of current circularity assessment methodologies used for EVs? (answered in Section 3.2.2).

Research Question3 (RQ3): What are the main research gaps and future work avenues in the research field of assessing the circularity of EVs? (answered in Section 4).

2.2. Research Methodology and Boundaries

To provide reliable insights, publications indexed in Scopus and Web of Science were collected for this review study. Overall, 70 papers published between 2017 and the end of August 2025 were analyzed. All these papers were related to measuring or assessing circularity in EVs. In this study, the Scopus and Web of Science database were used since they provide a broad range of journal articles that are indexed with a strong emphasis on quality. This approach considered all related published articles, leading to more detailed insights into the research questions.

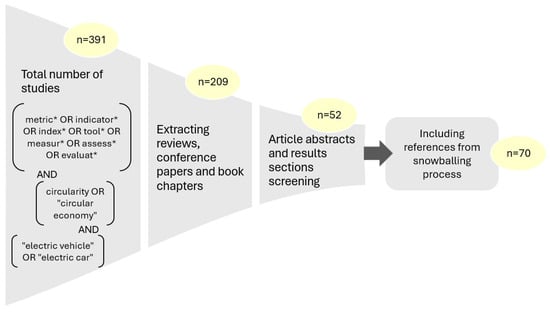

At the first step since we wanted to capture all database of articles related to the measuring or assessing circularity of EVs, the Scopus and Web of Science databases were searched using the following keywords: (TITLE-ABS-KEY(metric* OR indicator* OR index* OR tool* OR measur* OR assess* OR evaluat*) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(circularity OR “circular economy”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(“electric vehicle” OR “electric car”)). Keywords were searched for in the title, abstract, or keywords section of the papers. At this stage, 391 publications were identified, after removing the duplicates by comparing the outputs of the two databases.

Only full-text, peer-reviewed journal articles published in English were included from the initial search. To ensure the quality of the reviewed material, gray literature, web-based assessment approaches, conference papers, book chapters, and review articles were excluded. 209 articles remained because of this delimitation process.

In the initial screening of article abstracts and results sections, 157 papers were excluded for being irrelevant to the study’s focus or for lacking a circularity measurement. Only articles that measured at least one aspect of the CE at the product level were included. The large number of exclusions can be attributed to the frequent use of terms such as “measure,” “assess,” and “evaluate” in many articles, even when no actual circularity measurement was performed. Table 2 summarizes all selection criteria applied in this study.

Table 2.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria used in the systematic review process.

The risk of bias assessment was performed using all data retrieved from relevant databases. Two authors independently evaluated each included study, and any discrepancies were resolved through discussion to reach consensus. No automation tools or artificial intelligence were used in this process. Following the snow-balling process, 18 relevant articles were identified from the reference lists of key papers and subsequently included. This resulted in a final selection of 70 articles for the present literature review. The methodology for the systematic literature review is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

A schematic of the systematic literature review methodology. (The asterisk (*) represents a truncation symbol in the Scopus database, used to retrieve terms with different endings (e.g., evaluat* retrieves evaluate, evaluating, evaluation).

2.3. Coding Procedure

The coding procedure is a system that helps group and analyze data by assigning qualitative data to a set of labels. The following coding procedure demonstrates how each of the 70 papers were processed to extract relevant information that were essential in answering each of the defined research questions in Section 2.1 (see Supplementary File S1 for the complete list of papers and their categories).

RQ1: Different methodologies for measuring the circularity of EVs: Based on a preliminary review of the extracted methodologies, an initial categorization was developed. This categorization included a list of potential codes, such as “data collection methods” (e.g., surveys, interviews, observations), “analytical and mathematical models” (e.g., simulation and optimization techniques), “LCA models”, and “hybrid models”. The categorization was iteratively refined and expanded as the coding process progressed. Then, the methodology section of each article was carefully reviewed, and relevant passages describing research methods were identified and coded using the predefined categories. New categories were added as needed to capture unique or unexpected aspects of the methodologies. For example, ref. [3] applied Circularity Index (CI) and Product Circularity Indicator (PCI) for circularity assessment. Also, in their study, the Global Warming Potential (GWP) and Abiotic Depletion Potential of minerals (ADPm) were used for environmental performance measurement and life cycle assessment (LCA). As another example, Ref. [10] employed a qualitative model of expert and problem-centered interviews along with an exploratory workshop. An interview guide was developed to ensure a comprehensive and informed approach to gathering insights. Additionally, external experts from various sectors, including consultancy, clusters and associations, energy supply, LIB manufacturing, regulation, research and development, standardization, and repurposing, participated in an exploratory online workshop as part of a corresponding research project.

Finally, the coded data was analyzed to identify patterns, trends, and commonalities across the studies in Section 3.2.1.

RQ2: Primary objectives and limitations of current circularity assessment methodologies used for EVs: This procedure focuses on categorizing the primary purpose of each study within the literature review. An initial categorization was developed with the following main aspects:

- (1)

- Focusing on measurement tools: studies primarily focused on introducing a new tool or developing and/or validating existing tools specifically for assessing the circularity of EVs or their components.

- (2)

- Directly assessing EV circularity: studies that directly measured or assessed the circularity of EVs or their components using existing tools.

- (3)

- Using circularity assessment as a sub-tool: studies where circularity assessment was a secondary objective or used as a tool within a broader research scope.

For the coding process, each article was reviewed to determine its primary objective and categorized accordingly. If the study did not fit into the main categories, it was excluded from the database. For instance, the study of [3] was directly aiming at circularity assessment without focusing on the assessment tool analysis. Their main objective was to compare the circularity and environmental performance of lithium nickel manganese cobalt (NMC), and lithium iron phosphate (LFP) batteries subjected to two different recycling methods. Lifetime extension, improved energy efficiency, and material recovery ratios were also calculated to identify the optimal battery design. Therefore, this study would be clustered in the second category. On the other hand, the main objective of [10] was to evaluate EoL barriers. They investigate barriers, as well as necessary institutional framework conditions and organizational requirements for a successful market entry of SLB (second-life lithium-ion batteries) applications. As a result, this study belongs to the third category of indirect papers.

Finally, the categorized data was analyzed to determine the frequency and distribution of studies across the different categories in Section 3.2.2. This analysis provided insights into the predominant research focus within the literature on the assessment of EV circularity.

3. Descriptive and Content Analysis

This section presents a descriptive analysis of the reviewed articles, including the distribution of publication years and the most frequently cited journals. Furthermore, it will present the content analysis aligned with the identified research questions. Specifically, Section 3.2 will provide in-depth insights into contextual analyses, such as examining the methodologies employed, the intended purposes of circularity assessments, and identifying existing knowledge gaps.

3.1. Descriptive Analysis

This section analyzes the distribution of articles included in this review across different publication years and identifies the most frequently cited journals.

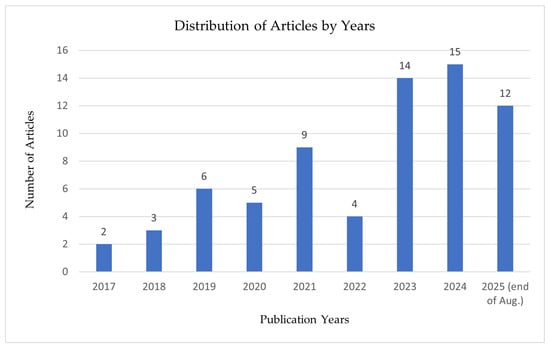

Figure 2 presents statistical data on the measurement of circularity in EVs based on articles published between 2017 and August 2025. A notable trend of increasing research activity is evident, with a significant jump in publications from 4 in 2022 to 14 in 2023, 15 in 2024 and 12 in 2025. This increase, evident in recent years, accounts for nearly 59% of all papers published in 2023 and beyond, highlighting the growing interest in and commitment to understanding and quantifying circularity within the EV sector.

Figure 2.

Distribution of articles by year.

The marked increase in CE practices in the EV sector during 2023 can be attributed to a convergence of external drivers and industry developments. Most notably, the enactment of the European Union’s battery regulation in July 2023 [19] set stricter sustainability standards for design, sourcing, recycling, and end-of-life management, creating strong incentives for automakers to adopt CE principles at scale. At the same time, the rapid growth in EV adoption—driven by government incentives, rising consumer demand, and technological advances—intensified concerns over critical raw material supply and battery waste, pushing industry players to secure resources through closed-loop systems [20].

Major manufacturers responded by accelerating investments in recycling infrastructure, redesigning products for durability and recyclability, and forming partnerships to ensure compliance and resilience [20]. This momentum did not end in 2023; similar patterns were observed in 2024 and 2025, as regulatory requirements tightened further and industry actors expanded their CE initiatives globally. These external pressures, coupled with the competitive need to demonstrate environmental responsibility, explain the surge in CE-related developments and publications observed in 2023.

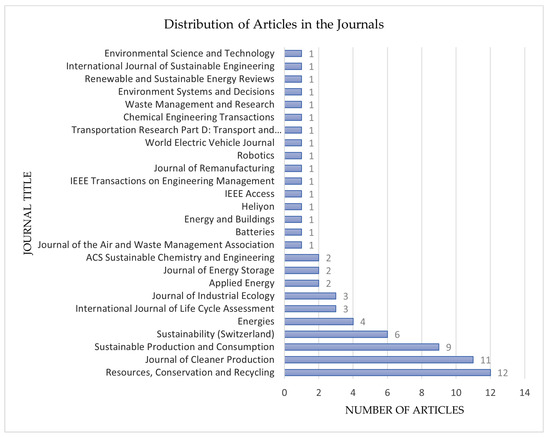

Figure 3 presents the distribution of publications on measuring circularity in EVs across academic journals. Resources, Conservation and Recycling and the Journal of Cleaner Production stand out as the most prominent outlets, publishing 12 and 11 articles, respectively—together accounting for nearly one-third of all contributions. Importantly, five of the 12 studies in this review that directly address circularity assessment tools for EVs were published in these two journals (about 42%). Sustainable Production and Consumption follows with nine publications, while Energies and Sustainability (Switzerland) contribute six and four, respectively. Both the International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment and the Journal of Industrial Ecology include three articles each. A smaller group of journals—such as Applied Energy, Journal of Energy Storage, and the ACS Sustainable Chemistry and Engineering—each contain two publications. The remainder, including Batteries, Energy and Buildings, and Journal of Remanufacturing, feature only a single article. Overall, the distribution underscores the central role of environmental science and sustainability journals in shaping the scholarly discourse on circularity measurement in the EV sector.

Figure 3.

Distribution of articles in the impact factored journals.

3.2. Content Analysis

3.2.1. Review of EV Circularity Assessment Methods

This section addresses Research Question 1, which focuses on reviewing and analyzing the various methodologies employed in the literature related to measuring the circularity of EVs at the product level. A notable observation is that a majority of the reviewed studies (61 out of 70, approximately 87%) primarily focus on the battery component of EVs, rather than assessing circularity across the entire vehicle.

This section focuses specifically on methodologies considered in the reviewer articles used to measure EV circularity. Methodologies presented in other sections of the articles relevant to other aspects of EV research, were excluded from this analysis. Table 3 presents the final categorization of the reviewed articles in this study related to research question 1. In this review, the scope was not restricted to studies explicitly labeled as “circular economy assessment”. Instead, all works aiming to measure or evaluate CE-related strategies through their methods were included. As a result, a range of approaches beyond the commonly adopted assessment models, such as LCA and MFA, were encountered. To structure this diversity, categorizations similar to those used in other systematic reviews of circularity assessment [21,22] were drawn upon. In addition, distinctions between quantitative and qualitative assessment models have been introduced and discussed in broader review studies on circularity assessment [13,23], which further support the chosen classification approach.

It can be highlighted that LCA is the most widely used methodology, accounting for 36 out of the total studies. This suggests that LCA is considered the primary framework for assessing the environmental impacts and resource use associated with EVs, aligning with its established role in environmental impact assessment. However, MFA is used in a relatively small number of studies (6). This suggests that MFA while facing challenges in data collection and analysis for complex systems like EVs, may find greater application in predicting future EV demand.

In addition, as noted in Table 3, the significant number of studies employing “combined assessment tools” (11) is noteworthy. This indicates a growing trend towards integrating multiple assessment methods to gain a more comprehensive understanding of EV circularity. These combined methods frequently incorporated Life Cycle Assessment (LCA), often paired with complementary techniques such as the Product Circularity Index (PCI) [3], Life Cycle Costing (LCC) [24,25], Material Circularity Indicator (MCI) ([25,26], Substance Flow Analysis (SFA) and Human Health Risk Assessment (HHRA) [27], or Material Flow Analysis (MFA) [28,29,30,31,32]. One used MFA in conjunction with their novel multi-layer material flow analysis model, MATILDA [33], while another combines MCI with Circular Transition Indicators (CTI) [26].

The use of “analytical and mathematical models” in eight studies suggests a focus on quantitative analysis and optimization of circularity strategies. The presence of eight studies utilizing qualitative methods indicates a growing recognition of the importance of stakeholder perspectives and social considerations in assessing EV circularity.

Table 3 also reveals an evolution in methodological approaches. LCA dominated early research (2017–2021) with 23 publications. From 2022 onwards, MFA gained prominence. More recently, between 2023 and 2025, a shift toward hybrid approaches, incorporating multiple assessment tools and mathematical and simulation techniques, is evident.

Table 3.

An overview of the methodologies related to the circularity assessment analysis of the EV domain.

Table 3.

An overview of the methodologies related to the circularity assessment analysis of the EV domain.

| Methodologies | Number of Articles | References |

|---|---|---|

| Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) | 36 | [1,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68] |

| Material Flow Analysis (MFA) | 6 | [69,70,71,72,73,74] |

| Other assessment tools (GREET) | 1 | [75] |

| Analytical and mathematical models | 8 | [4,76,77,78,79,80,81,82] |

| Combined assessment tools | 11 | [3,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33] |

| Qualitative methods | 8 | [10,83,84,85,86,87,88,89] |

Samani et al. [7] in their study talked about LCA methodological limitations in general in comparison to circularity assessment tools such as Material Circularity Index (MCI). A central critique is that LCA was originally designed for a linear economy, assessing systems from cradle to grave, rather than cradle to cradle. This means that anthropogenic stock and dissipation flows, which are crucial to understanding circularity, are not fully captured within conventional LCA models. Although recycling and energy recovery steps are sometimes included in LCA, the methodology does not adequately reflect circular strategies such as product lifetime extension, maintenance, or reuse. By contrast, tools like MCI are specifically designed to capture aspects of material preservation and cycling efficiency.

Another limitation of LCA mentioned in [7,11], lies in its dependence on assumptions and methodological choices that strongly influence results. For instance, the definition of functional units, system boundaries, and allocation procedures—particularly for multi-product systems or recycling scenarios—can lead to highly divergent outcomes. Even though some standardized approaches exist, there is still no consensus on how to allocate burdens and benefits across multiple life cycles. This lack of harmonization creates uncertainty in interpreting LCA results for circular systems. In contrast, circularity indicators are often simpler to apply and communicate, though they risk overlooking broader environmental trade-offs [7].

Finally, based on [7], traditional LCA approaches face challenges in handling the complexity of multiple life cycles, products, functions, and strategies simultaneously. Attributional LCA typically models a product system in isolation, while consequential LCA attempts to assess system-wide changes, yet neither approach fully resolves the challenge of integrating circularity strategies such as repair, refurbish, or repurpose. Moreover, LCA primarily evaluates potential environmental impacts in categories like global warming potential or resource depletion, but it rarely accounts for functionality over time, a key element of circularity. Circularity assessments, while less comprehensive environmentally, emphasize product utility, longevity, and material cycling, making them more suited for evaluating strategies that maintain or enhance product functions. This misalignment highlights why LCA, while useful as a complementary framework, is not always sufficient on its own for assessing circularity [7,40].

In addition, Husmann et al. [5] provide some insights about LCA limitations particularly in the context of EVs. One significant challenge is handling multifunctionality at the End-of-Life (EoL) stage of batteries. As battery recycling becomes more common due to regulatory pressure, LCA models must account for the dual function of recycling processes—waste treatment and secondary material production. This dual role complicates how environmental impacts and benefits are allocated across products. A similar complexity arises in secondary material production, where recycling often yields multiple materials. Properly allocating environmental burdens among these co-products requires transparent and consistent methodologies, which are currently lacking or underdeveloped in many LCA frameworks.

A third challenge that [5] mentioned, emerges from product-level multifunctionality, particularly when batteries are repurposed for second-life applications such as stationary energy storage or used in vehicle-to-grid (V2G) systems. These applications add new functions to the battery’s life cycle while delaying recycling and material recovery, creating trade-offs that are difficult to quantify in LCA. Additionally, material quality poses a limitation—secondary materials may differ in performance from primary ones, yet most LCA studies fail to incorporate these quality differences, leading to skewed results. Lastly, inadequate resource indicators hinder the assessment of circular economy strategies. While policy frameworks emphasize efficient resource use, LCAs often overlook impacts related to resource depletion, especially concerning critical and strategic materials. This gap restricts LCA’s ability to fully capture the environmental trade-offs involved in transitioning to electromobility [5,63].

3.2.2. Review of EV Circularity Assessment Purposes

This section focuses on addressing the second research question of this literature review: analyzing the different objectives of publications related to measuring or assessing circularity of EVs. To achieve this, we first categorized the purpose of these 70 papers into three main clusters and then analyzed each category separately.

- -

- Papers that are directly related to circularity assessment tools of EVs

Twelve papers directly address circularity assessment of EVs. These papers include those introducing a new measurement tool, as well as those analyzing or improving existing tools. Details of these publications are provided in Table 4.

Table 4.

An overview of the purposes related to the circularity assessment analysis of electric vehicle domain.

It is evident that the literature lacks studies that test or validate assessment tools for electric vehicles (EVs) or compare different assessment tools applicable to EVs.

- -

- Papers aimed at assessing the circularity of EVs

The next category is related to papers that focus on evaluating EV circularity by applying current assessment tools such as LCA or MFA without concentrating on analyzing the assessment method itself. This constitutes the largest segment, with 49 out of 70 papers (approximately 70%). We further subdivide this category into two main groups.

The first, and most substantial group (42 papers), focuses on quantifying environmental impacts associated with EVs, including Global Warming Potential (GWP), Abiotic Depletion Potential (ADPm), water footprint, resource utilization, and recycled content standards. A significant portion (33 papers) within this group employs a cradle-to-grave LCA approach, primarily to assess End-of-Life (EoL) scenarios such as recycling, repurposing, and disassembly. The second group investigates the social, economic, and demand-related aspects of Circular Economy (CE) implementation in the EV sector. Finally, some studies, for example [38], are related to both categories by examining the circular business model (CBM) of battery leasing for Battery Electric Vehicles (BEVs), comparing its economic and environmental impacts with those of the linear model of battery sales.

Both groups can be further categorized based on their scope: studies assessing EVs in general, and those comparing impact assessments across different EoL scenarios, battery products, or vehicle models. Table 5 provides an overview of the publications within each comparative analysis type for the environmental impact and resource use assessment categories. Table 6 provides an overview of social and economic impact assessment publications.

Table 5.

An overview of environmental impact and resource use assessment publications.

Table 6.

An overview of social and economic impact assessment publications.

- -

- Papers using circularity assessment tools combined with another approach

The final group of nine papers utilizes EV circularity metrics as a component of broader research goals. While all assess aspects of circularity, their primary focus lies in areas such as: developing dynamic models to predict the recovery potential of neodymium from rare earth permanent magnets in end-of-life products [69]; determining the optimal sizing for Battery Energy Storage Systems (BESS) using repurposed EV batteries [46]; and analyzing the complexities of raw material recovery processes [4]. More generally, these papers explore various end-of-life (EoL) strategies for EVs, including disassembly and recycling methodologies [10,24,77,78,84,85].

4. Research Findings, Gaps, and Future Opportunities

This review highlights the approaches used to evaluate circularity in electric vehicles and the purposes these methods serve. The findings show that LCA is the most frequently applied methodology, and as a result, research in this field has been predominantly directed toward impact assessment objectives. Since these two research questions are closely connected, the research gaps identified from the literature have been clustered into smaller categories, which are outlined in the following paragraphs.

4.1. The Absence of EV-Specific Circularity Assessment Frameworks

A key gap identified in this paper is the absence of circularity assessment methods designed specifically for electric vehicles (EVs). Such tailored methods are essential due to the unique characteristics of EVs and their supply chains. While Section 3.2 highlights 48 studies addressing circularity assessment in EVs, most of these rely on established tools such as Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) and Material Flow Analysis (MFA). Their primary focus is often on evaluating environmental impacts, rather than on developing dedicated assessment frameworks for EVs. Although LCA is the most widely used approach, it faces limitations in modeling complex processes such as open-loop recycling. As suggested by several studies (e.g., [7,18]), combining LCA with circularity assessment tools may provide more reliable results. Notably, only nine studies (see Section 3.2.2) explicitly focus on circularity measurement tools for EVs, and even these are largely adaptations of existing methods. Overall, the literature review indicates a critical need to translate circular economy (CE) principles into a comprehensive, sector-specific definition and framework for EVs.

Achieving EV-specific circularity measurement requires effective management of material and energy flows throughout their entire lifecycle. EV supply chains are complex, global, and highly dependent on critical raw materials such as lithium, cobalt, nickel, and rare earth elements—resources often concentrated in geographically limited and geopolitically sensitive regions [2,51]. Current challenges include poor supply chain traceability, limited transparency, and variations in recycling potential and environmental impact across different cathode chemistries [3]. Further barriers arise from data confidentiality and intellectual property concerns, which restrict the availability of reliable information. In addition, EVs typically have long service lives (10–15+ years), yet large-scale real-world data on battery degradation, second-life performance, and recycling efficiency remain scarce [9]. This lack of longitudinal evidence increases uncertainty when modeling future circularity scenarios.

Digital Product Passports (DPPs) can help overcome these data management challenges. DPPs are defined as unique product identifiers containing a product-specific dataset that may serve to promote circular information flows and to bridge information gaps across value chains, thereby enabling the exchange of information along products’ lifecycles. Comprehensive EV circularity assessment requires lifecycle-wide data, beginning with a detailed bill of materials that specifies mass, composition, and recycled content. Use-phase information—such as lifetime, mileage, state-of-health, degradation, and repair history—is essential to capture how effectively vehicles and batteries are utilized [9]. At end-of-life, routing data on repair, repurposing, recycling, or disposal must also be recorded. Recycling-specific metrics, including process type, recovery yields, material purity, and comparative energy intensity of virgin versus recycled materials, are crucial for evaluating loop quality and linking circularity with energy savings [12]. Finally, traceability through EV passports ensures that these datasets are consistently tracked across the value chain, enabling reliable and standardized measurement of circularity.

Most of the studied frameworks rely on spreadsheets or web portals, which require extensive manual data entry [90]. For electric vehicles, using a DPP ensures transparency across the value chain by making standardized data on materials, components, and manufacturing easily accessible. It enables accurate measurement of circularity by tracking recycled content, reuse potential, and recyclability of parts, while also enhancing lifecycle management—particularly for critical components such as batteries and electronics [90]. In addition, the DPP supports regulatory compliance and improves material recovery by helping recyclers identify and efficiently extract valuable resources such as lithium, cobalt, and rare earth elements. The proposed DPP model would improve product understanding and strengthen decision-making processes, including those related to purchasing new or used products, as well as facilitating repairs and recycling. It can also provide comprehensive product information throughout the entire lifecycle, thereby enhancing circular economy (CE) strategies, promoting the use of secondary raw materials, reducing greenhouse gas emissions, and minimizing the extraction of natural resources.

While DPPs offer significant potential for improving the assessment of circularity in electric vehicles (EVs), their practical implementation faces several challenges. A key concern is determining what types of data should be collected—particularly from EV batteries during the use phase—and how this data can be systematically updated throughout the product’s entire life cycle. The absence of a unified structure across studies and industries risks fragmentation and hinders interoperability [91]. This underscores the need for regulatory frameworks and industry-wide standards that define core data requirements and ensure consistency. Addressing this challenge requires coordinated collaboration among stakeholders, supported by digital technologies such as IoT sensors, blockchain-based ledgers, and cloud infrastructures. The use of decentralized identifiers linked to verifiable data registries could further enhance traceability, while reliability can be reinforced through standardized data validation protocols, third-party verification, and periodic audits [92].

Beyond data collection, integrating diverse supply chain actors into a DPP framework presents different challenges. Variations in technological maturity, regulatory environments, and infrastructure create barriers to effective adoption [90,93]. The recycling sector, in particular, faces additional data management challenges, including security, fraud prevention, and the risk of exposing sensitive customer or business information. Finally, across the EV value chain, stakeholders are often reluctant to share data due to intellectual property concerns, privacy risks, and the absence of adequate incentives or agreed-upon sharing standards [93,94]. To overcome these barriers, it is essential to design secure, incentive-driven frameworks that balance transparency with data protection, and to promote real-time monitoring and traceability systems that improve both trust and the overall integrity of DPPs.

4.2. Limited Multidimensional and Stakeholder-Inclusive Approaches

Another important gap highlighted by this review is the lack of comprehensive and systematic circularity assessment models for electric vehicles (EVs). As shown in Section 3.2, only nine studies addressed social and economic aspects, and even these were limited in scope. Similar shortcomings are found in other circularity assessments [6,13], which often neglect the balance between environmental quality, economic prosperity, and social equity [6]. Focusing on only one or two dimensions risks implementing CE strategies that are not truly sustainable, particularly when social aspects are overlooked.

Socio-economic development is a key driver of CE, covering consumer behavior and mindset, labor practices, human rights, education, equity, and transparency [6,13]. Capturing these dimensions requires the active involvement of a broad range of stakeholders. As noted by [13], CE can only be effectively implemented when all key actors—consumers, suppliers, governments, universities, research institutions, employees, investors, and designers—actively contribute to reshaping business models and influencing behavior.

Each of these stakeholder groups plays a critical role in advancing circularity within the EV sector. Their decisions are interdependent and should therefore be addressed collectively. Future research should move beyond technical and environmental assessments to embrace multi-dimensional transitions. This system view should consider the various actors involved throughout the EV lifecycle, including, but not limited to:

- Manufacturers/brand owners, responsible for digital product passports (DPPs).

- Consumers, whose purchasing and disposal behavior affect circularity.

- Supporting agents, such as suppliers, recyclers, and policymakers, who enable circular practices.

Adopting such a systems perspective allows circularity assessments to capture the full EV lifecycle rather than isolated elements. Multidisciplinary approaches supported by tools like digital product passports can provide robust life cycle data, improve decision-making, and reduce both greenhouse gas emissions and resource use. For companies, stakeholder engagement also delivers additional benefits, including employee motivation, stronger organizational identity, and improved usability of assessment tools [7,8,95]. Finally, because stakeholders can be engaged at different stages—during tool design, indicator selection, or practical application—the resulting assessments are more likely to be both comprehensive and operational.

Nevertheless, measuring socio-economic indicators remains a challenge. Metrics such as skills development and circular job creation are often too generic, difficult to monitor, and lack clear evidence linking CE with social equity [13,95]. Other obstacles include limited data availability, the high costs and time demands of real-world data collection, poor information exchange, and confidentiality concerns [13].

4.3. Narrow and Fragmented Focus on Batteries over Whole-Systems

Another gap regarding creating a comprehensive measurement should be addressed by considering EVs as a whole, rather than focusing only on their batteries or battery cells. Approximately 87% of the research in the literature emphasizes EV battery cells and modules, leaving other crucial areas underexplored. The primary reasons for this imbalance are that the lithium-ion battery is both the most resource-intensive and environmentally burdensome component of an EV, largely due to the extraction and processing of critical raw materials. Currently, it is typically the most expensive part of the vehicle, which makes circular strategies particularly appealing from an economic standpoint. In addition, policies such as the EU Battery Regulation in 2023 [19] mandate recycled content, carbon footprint reporting, and take-back schemes, further driving researchers and industry toward battery-focused assessments.

However, this narrow emphasis on batteries overlooks the broader system-level challenges of EV circularity. Components such as electric motors, power electronics, lightweight alloys, and advanced electronics also play a critical role in resource consumption and end-of-life management. Despite their importance, these areas remain underrepresented in current studies, which limits our understanding of the circularity potential of EVs as integrated systems.

To address this imbalance, future research should shift toward comprehensive frameworks that evaluate the circularity of entire EV systems. This involves developing standardized methodologies for measuring resource efficiency, modeling trade-offs across recycling and reuse pathways, and integrating design-for-circularity principles into manufacturing. Collaboration among automakers, policymakers, and recycling industries will be essential to ensure that such strategies are not only technically sound but also scalable and economically viable.

4.4. Lack of Design for Circularity: Modularity and Standardization in EV Batteries

Given the substantial investment in electric vehicles and battery technologies, precise measurement and monitoring of progress toward circular economy goals is imperative. One significant gap in current EV battery circularity assessments is the limited consideration of modularity and standardization. Modularity refers to designing battery packs as separable units, while standardization involves using common interfaces, components, and processes across products. Both principles are crucial enablers of design for circularity, as they simplify disassembly, repair, and replacement—making operations faster, safer, and more cost-effective. However, the current literature reveals that existing circularity assessment frameworks lack systematic methods for evaluating these two aspects. More broadly, design for circularity means rethinking product lifecycles from the outset by embedding reuse, repurposing, and recycling into the design process [96].

In practice, modularity and standardization in EV battery design are central to achieving circularity because they enable more efficient repair, reuse, and recycling. Modular pack designs, for example, allow degraded cells or modules to be individually replaced, extending first-life usage and postponing end-of-life (EoL) processing [96]. This not only enhances resource efficiency but also reduces lifecycle costs for both manufacturers and consumers. Furthermore, modularity supports second-life applications: used packs can be dismantled into modules and reassembled into stationary energy storage systems, creating additional value while decreasing demand for raw materials [40]. Standardization amplifies these benefits by enabling recyclers to automate disassembly and sorting processes. In the absence of standardized formats, battery disassembly processes are predominantly manual, which is especially costly in regions with high labor expenses, ultimately undermining the profitability of circular strategies [96].

Designing for circularity also creates other efficiencies across recycling processes. A battery designed with standardized formats and disassembly features enables “direct recycling,” in which electrodes and other components are separated with minimal contamination and recovered at high purity [96]. This contrasts with current shredding-based methods, which mix materials and complicate recovery. On a systemic level, circular business models (CBMs) built around these design principles enable cross-company collaborations that enhance collection rates and optimize repurposing and recycling processes. For example, South Korea has launched public–private partnerships to develop a sustainable EV battery ecosystem, showing how standardization can unlock broader economic and environmental benefits [97].

However, challenges remain significant. A major barrier is the rapid pace of technological innovation in EV batteries, with frequent changes in chemistries and architectures complicating recycling and reuse strategies [97]. Processes designed for one generation of batteries may not apply to newer models, which makes it difficult to develop long-term, cost-efficient recycling technologies. In addition, secrecy among EV and battery manufacturers, while beneficial for competition, hinders the sharing of data and standards needed for efficient circular practices [97]. In addition, design for circularity faces a balance between safety, performance, and disassembly requirements. Features such as externally triggerable opening mechanisms or water-soluble binders could ease separation of components, but they must not compromise safety during first and second life operations [96]. Similarly, while repurposing batteries for stationary energy storage offers clear benefits, the process involves remanufacturing, reassembly, and integration steps that add environmental and logistical burdens [40]. These trade-offs show that modularity, standardization, and circularity are not one-size-fits-all solutions, but rather enablers of flexible “R-strategies” (repair, refurbish, remanufacture, recycle) that must be tailored to future material streams and market conditions [96].

Future studies should focus on building assessment frameworks with clear metrics to evaluate modularity and standardization in battery circularity, providing a common basis for comparison across designs and markets. Parallel research on design innovation can explore practical solutions—such as reversible adhesives, standardized fastening systems, and smart connectors—that improve disassembly without compromising safety or performance. To guide decision-making, these insights should be integrated into lifecycle modeling, enabling predictive analysis of how modular and standardized designs affect costs, environmental impacts, and second-life applications across diverse contexts. Together, these efforts can create actionable pathways for manufacturers, policymakers, and recyclers to align innovation with circular economy goals.

5. Conclusions

This literature review has comprehensively examined the current landscape of circularity assessment methodologies and purposes within the electric vehicle (EV) sector. The results demonstrate that current approaches to assessing circularity in the EV sector remain fragmented. While methods such as LCA and MFA are widely used, they focus primarily on environmental impacts and fall short of capturing the multidimensional nature of circularity. Dedicated, EV-specific frameworks that integrate social and economic perspectives are still lacking, leaving research and practice without consistent and holistic tools.

From the synthesis of the literature, three overarching gaps become evident:

- Data limitations: Insufficient lifecycle-wide, transparent, and reliable information flows hinder robust assessment.

- Narrow scope: Most frameworks exclude social and economic pillars, which are essential for just and scalable circularity transitions.

- Fragmentation: A lack of standardized, sector-specific frameworks prevents meaningful comparison and benchmarking across studies.

To address these shortcomings, future research should prioritize:

- Developing EV-specific circularity frameworks that combine environmental, social, and economic dimensions.

- Embedding Digital Product Passports (DPPs) to improve data traceability, interoperability, and real-time monitoring.

- Adopting systems perspectives that capture the interdependence of multiple stakeholders across the EV value chain.

For industry and policymakers, the review points to actionable priorities: (i) establishing harmonized standards for circularity data collection and reporting, (ii) incentivizing transparent data sharing across the EV value chain, and (iii) embedding circularity requirements into regulatory frameworks that go beyond batteries to encompass the entire vehicle system. By aligning technological innovation with governance and stakeholder collaboration, the EV sector can move from fragmented assessments toward a systemic, measurable, and actionable circular economy transition.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/app151910622/s1, File S1: Manuscript-supplementary.xlsx. References cited in this file are included in the main reference list.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.G., N.P. and F.P.A.; methodology, P.G. and F.P.A.; software, F.P.A.; validation, N.P., P.G. and F.P.A.; formal analysis, F.P.A.; investigation, F.P.A.; resources, F.P.A.; data curation, F.P.A.; writing—original draft preparation, F.P.A.; writing—review and editing, P.G., N.P., F.P.A. and V.H.; visualization, F.P.A.; supervision, P.G. and N.P.; project administration, P.G.; funding acquisition, P.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This publication has been partially supported by the European Union’s Horizon Programme, under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 101073508 (iCircular3).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LCA | Life cycle assessment |

| CE | Circular economy |

| EV | Electric vehicle |

| EoL | End-of-life |

| MFA | Material Flow Analysis |

References

- Kang, H.; Jung, S.; Kim, H.; An, J.; Hong, J.; Yeom, S.; Hong, T. Life-cycle environmental impacts of reused batteries of electric vehicles in buildings considering battery uncertainty. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 207, 114936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrara, S.; Bobba, S.; Blagoeva, D.; Alves, D.; Cavalli, A.; Georgitzikis, K.; Grohol, M.; Itul, A.; Kuzov, T.; Latunussa, C.; et al. Supply Chain Analysis and Material Demand Forecast in Strategic Technologies and Sectors in the EU-A Foresight Study; JRC Science for Policy Report; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picatoste, A.; Schulz-Mönninghoff, M.; Niero, M.; Justel, D.; Mendoza, J.M.F. Comparing the circularity and life cycle environmental performance of batteries for electric vehicles. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2024, 210, 107833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratap, B.; Mohan, T.K.; Amit, R.; Venugopal, S. Evaluating circular economy strategies for raw material recovery from end-of-life lithium-ion batteries: A system dynamics model. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2024, 50, 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husmann, J.; Beylot, A.; Perdu, F.; Pinochet, M.; Cerdas, F.; Herrmann, C. Towards consistent life cycle assessment modelling of circular economy strategies for electric vehicle batteries. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2024, 50, 556–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchherr, J.; Reike, D.; Hekkert, M. Conceptualizing the circular economy: An analysis of 114 definitions. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 127, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samani, P. Synergies and gaps between circularity assessment and Life Cycle Assessment (LCA). Sci. Total. Environ. 2023, 903, 166611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, M.V.; Salvador, R.; Pieroni, M.; Piekarski, C.M. How to measure circularity? State-of-the-art and insights on positive impacts on businesses. Environ. Dev. 2024, 50, 100989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Deng, X.; Wang, F.; Deng, Z.; Lin, X.; Teodorescu, R.; Pecht, M.G. A Review of Second-Life Lithium-Ion Batteries for Stationary Energy Storage Applications. Proc. IEEE 2022, 110, 735–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prenner, S.; Part, F.; Jung-Waclik, S.; Bordes, A.; Leonhardt, R.; Jandric, A.; Schmidt, A.; Huber-Humer, M. Barriers and framework conditions for the market entry of second-life lithium-ion batteries from electric vehicles. Heliyon 2024, 10, e37423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picatoste, A.; Justel, D.; Mendoza, J.M.F. Circularity and life cycle environmental impact assessment of batteries for electric vehicles: Industrial challenges, best practices and research guidelines. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 169, 112941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Li, W.; Poulet, T.; Basarir, H.; Karrech, A. Life cycle assessment of recycling lithium-ion battery related mineral processing by-products: A review. Miner. Eng. 2024, 208, 108600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrispim, M.C.; Mattsson, M.; Ulvenblad, P. The underrepresented key elements of Circular Economy: A critical review of assessment tools and a guide for action. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 35, 539–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadé, M.; Erradhouani, B.; Pawlak, S.; Appendino, F.; Peuportier, B.; Roux, C. Combining circular and LCA indicators for the early design of urban projects. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2022, 27, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prados, T.M.; Barroso, T.L.C.T.; Forster-Carneiro, T.; Lovón-Canchumani, G.A.; Colpini, L.M.S. Life cycle assessment and circular economy in the production of rare earth magnets: An updated and comprehensive review. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2024, 27, 471–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sherif, D.M.; Abouzid, M.; Saber, A.N.; Hassan, G.K. A raising alarm on the current global electronic waste situation through bibliometric analysis, life cycle, and techno-economic assessment: A review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 40778–40794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onat, N.C.; Kucukvar, M. A systematic review on sustainability assessment of electric vehicles: Knowledge gaps and future perspectives. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2022, 97, 106867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corona, B.; Shen, L.; Reike, D.; Carreón, J.R.; Worrell, E. Towards sustainable development through the circular economy—A review and critical assessment on current circularity metrics. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 151, 104498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament; Council of the European Union. Regulation (EU) 2023/1542 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 12 July 2023 on Batteries and Waste Batteries, Amending Regulation (EU) 2019/1020 and Repealing Directive 2006/66/EC. 2023. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2023/1542/oj/eng (accessed on 14 June 2025).

- Sampaio Cintra, R.; Veiga Avila, L.; Schvartz, M.A.; Filho, W.L.; Anholon, R.; Salati Marcondes de Moraes, G.H.; Mairesse Siluk, J.C.; da Silva Lisboa, G.; Dib Khaled, N.N. Analysis of the Life Cycle and Circular Economy Strategies for Batteries Adopted by the Main Electric Vehicle Manufacturers. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roos Lindgreen, E.; Salomone, R.; Reyes, T. A critical review of academic approaches, methods and tools to assess circular economy at the micro level. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos Gonçalves, P.V.; Campos, L.M.S. A systemic review for measuring circular economy with multi-criteria methods. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 31597–31611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khadim, N.; Agliata, R.; Marino, A.; Thaheem, M.J.; Mollo, L. Critical review of nano and micro-level building circularity indicators and frameworks. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 357, 131859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teunissen, F.; van Bergen, E. Demonstrating the Lessons Learned for Lightweighting EV Components through a Circular-Economy Approach. World Electr. Veh. J. 2024, 15, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, R.; Golkaram, M.; Vogels, J.T.W.E.; Ligthart, T.; Someren, E.; Ferjan, S.; Lennartz, J. BEVSIM: Battery electric vehicle sustainability impact assessment model. J. Ind. Ecol. 2023, 27, 1266–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz-Mönninghoff, M.; Neidhardt, M.; Niero, M. What is the contribution of different business processes to material circularity at company-level? A case study for electric vehicle batteries. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 382, 135232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, R.; Al Alam, A.; Abu Sayeed, K.M.; Ahmed, S.A.; Haque, N.; Hossain, M.M.; Sujauddin, M. Patching sustainability loopholes within the lead-acid battery industry of Bangladesh: An environmental and occupational health risk perspective. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2024, 48, 435–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, D.A.; Eyckmans, J.; Van Acker, K. The impact of demand-side strategies to enable a more circular economy in private car mobility. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2024, 49, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, J.; Kendall, A.; Slattery, M. Electric vehicle lithium-ion battery recycled content standards for the US—Targets, costs, and environmental impacts. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 185, 106488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.A.; Nazzal, M.A.; Darras, B.M.; Deiab, I.M. A Comprehensive Sustainability Assessment of Battery Electric Vehicles, Fuel Cell Electric Vehicles, and Internal Combustion Engine Vehicles through a Comparative Circular Economy Assessment Approach. Sustainability 2022, 15, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen-Tien, V.; Dai, Q.; Harper, G.D.; Anderson, P.A.; Elliott, R.J. Optimising the geospatial configuration of a future lithium ion battery recycling industry in the transition to electric vehicles and a circular economy. Appl. Energy 2022, 321, 119230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobba, S.; Bianco, I.; Eynard, U.; Carrara, S.; Mathieux, F.; Blengini, G.A. Bridging tools to better understand environmental performances and raw materials supply of traction batteries in the future EU fleet. Energies 2020, 13, 2513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, F.A.; Billy, R.G.; Müller, D.B. Evaluating strategies for managing resource use in lithium-ion batteries for electric vehicles using the global MATILDA model. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2023, 193, 106951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chayutthanabun, A.; Chinda, T.; Papong, S. End-of-life management of electric vehicle batteries utilizing the life cycle assessment. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 2024, 75, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wüstenhagen, S.; Kirschstein, T. Substitution of Conventional Vehicles in Municipal Mobility. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestri, L.; Forcina, A.; Silvestri, C.; Arcese, G.; Falcone, D. Exploring the Environmental Benefits of an Open-Loop Circular Economy Strategy for Automotive Batteries in Industrial Applications. Energies 2024, 17, 1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mafrici, S.; Madonna, V.; Meano, C.M.; Hansen, K.F.; Tenconi, A. Switched Reluctance Machine for Transportation and Eco-Design: A Life Cycle Assessment. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 68334–68344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Salazar, M.; Kormazos, G.; Jienwatcharamongkhol, V. Assessing the economic and environmental impacts of battery leasing and selling models for electric vehicle fleets: A study on customer and company implications. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 422, 138356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akasapu, U.; Hehenberger, P. A design process model for battery systems based on existing life cycle assessment results. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 407, 137149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrålsen, B.; O’bOrn, R. Use of life cycle assessment to evaluate circular economy business models in the case of Li-ion battery remanufacturing. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2023, 28, 554–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, B.; Chowdhury, N.A.; Diaz, L.A.; Jin, H.; Saha, A.K.; Shi, M.; Klaehn, J.R.; Lister, T.E. Electrochemical leaching of critical materials from lithium-ion batteries: A comparative life cycle assessment. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2023, 193, 106973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey, I.; Vallejo, C.; Santiago, G.; Iturrondobeitia, M.; Lizundia, E. Environmental Impacts of Graphite Recycling from Spent Lithium-Ion Batteries Based on Life Cycle Assessment. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 14488–14501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz-Mönninghoff, M.; Bey, N.; Nørregaard, P.U.; Niero, M. Integration of energy flow modelling in life cycle assessment of electric vehicle battery repurposing: Evaluation of multi-use cases and comparison of circular business models. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 174, 105773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadhukhan, J.; Christensen, M. An in-depth life cycle assessment (Lca) of lithium-ion battery for climate impact mitigation strategies. Energies 2021, 14, 5555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinne, M.; Elomaa, H.; Porvali, A.; Lundström, M. Simulation-based life cycle assessment for hydrometallurgical recycling of mixed LIB and NiMH waste. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 170, 105586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusenza, M.A.; Guarino, F.; Longo, S.; Ferraro, M.; Cellura, M. Energy and environmental benefits of circular economy strategies: The case study of reusing used batteries from electric vehicles. J. Energy Storage 2019, 25, 100845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobba, S.; Mathieux, F.; Ardente, F.; Blengini, G.A.; Cusenza, M.A.; Podias, A.; Pfrang, A. Life Cycle Assessment of repurposed electric vehicle batteries: An adapted method based on modelling energy flows. J. Energy Storage 2018, 19, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusenza, M.A.; Guarino, F.; Longo, S.; Mistretta, M.; Cellura, M. Reuse of electric vehicle batteries in buildings: An integrated load match analysis and life cycle assessment approach. Energy Build. 2019, 186, 339–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Yilmaz, H.Ü.; Wang, Z.; Poganietz, W.-R.; Jochem, P. Greenhouse gas emissions of electric vehicles in Europe considering different charging strategies. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2020, 87, 102534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusenza, M.A.; Bobba, S.; Ardente, F.; Cellura, M.; Di Persio, F. Energy and environmental assessment of a traction lithium-ion battery pack for plug-in hybrid electric vehicles. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 215, 634–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemechu, E.D.; Sonnemann, G.; Young, S.B. Geopolitical-related supply risk assessment as a complement to environmental impact assessment: The case of electric vehicles. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2015, 22, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Ramírez, M.C.; Ferreira, V.J.; García-Armingol, T.; López-Sabirón, A.M.; Ferreira, G. Battery manufacturing resource assessment to minimise component production environmental impacts. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; You, F. Comparative life cycle assessment of three recycling approaches for electric vehicle lithium-ion battery after cascaded use. CET J.-Chem. Eng. Trans. 2020, 81, 1123–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Picirelli de Souza, L.; Silva Lora, E.E.; Escobar Palacio, J.C.; Rocha, M.H.; Grillo Renó, M.L.; Venturini, O.J. Comparative environmental life cycle assessment of conventional vehicles with different fuel options, plug-in hybrid and electric vehicles for a sustainable transportation system in Brazil. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 203, 444–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioakimidis, C.S.; Murillo-Marrodán, A.; Bagheri, A.; Thomas, D.; Genikomsakis, K.N. Life cycle assessment of a lithium iron phosphate (LFP) electric vehicle battery in second life application scenarios. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayyas, A.; Omar, M.; Hayajneh, M.; Mayyas, A.R. Vehicle’s lightweight design vs. electrification from life cycle assessment perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 167, 687–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raugei, M.; Winfield, P. Prospective LCA of the production and EoL recycling of a novel type of Li-ion battery for electric vehicles. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 213, 926–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Luo, X.; Zhang, Z.; Meng, F.; Yang, J. Life cycle assessment of lithium nickel cobalt manganese oxide (NCM) batteries for electric passenger vehicles. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 273, 123006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Yu, J. A comparative life cycle assessment on lithium-ion battery: Case study on electric vehicle battery in China considering battery evolution. Waste Manag. Res. 2020, 39, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, N.; Meiklejohn, E.; Overton, B.; Robinson, F.; Farjana, S.H.; Li, W.; Staines, J. A physical allocation method for comparative life cycle assessment: A case study of repurposing Australian electric vehicle batteries. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 174, 105759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; You, F. Comparative Life-Cycle Assessment of Li-Ion Batteries through Process-Based and Integrated Hybrid Approaches. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 5082–5094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chordia, M.; Nordelöf, A.; Ellingsen, L.A.-W. Environmental life cycle implications of upscaling lithium-ion battery production. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2021, 26, 2024–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, J.F.; Weil, M. Providing a common base for life cycle assessments of Li-Ion batteries. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 171, 704–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitcharangsie, S.; Paengkanya, S.; Papong, S. Environmental trade-offs of EV battery end-of-life options in Thailand: A life cycle assessment with sensitivity to electricity mix and battery degradation. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2025, 59, 63–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eduardo, S.; Recklies, E.A.; Nikolic, M.; Severengiz, S. A Comparative Life Cycle Assessment of End-of-Life Scenarios for Light Electric Vehicles: A Case Study of an Electric Moped. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olguín, F.P.; Iskakov, G.; Kendall, A. Trade, extended use, and end of life in the Global South: A regionally expanded electric vehicle life cycle assessment. J. Ind. Ecol. 2025, 29, 1167–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puricelli, S.; Eid, M.; Casadei, S.; Dolci, G.; Lixi, S.; van den Oever, A.; Rigamonti, L.; Grosso, M. Life cycle assessment of a partially renewable blend for bi-fuel passenger cars and comparison with petrol and battery electric cars. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 505, 145347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spindlegger, A.; Slotyuk, L.; Jandric, A.; De Souza, R.G.; Prenner, S.; Part, F. Environmental performance of second-life lithium-ion batteries repurposed from electric vehicles for household storage systems. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2025, 54, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maani, T.; Mathur, N.; Rong, C.; Sutherland, J.W. Estimating potentially recoverable Nd from end-of-life (EoL) products to meet future U.S. demands. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2023, 190, 106864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurdiawati, A.; Agrawal, T.K. Creating a circular EV battery value chain: End-of-life strategies and future perspective. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 185, 106484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huster, S.; Glöser-Chahoud, S.; Rosenberg, S.; Schultmann, F. A simulation model for assessing the potential of remanufacturing electric vehicle batteries as spare parts. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 363, 132225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]