1. Introduction

With the continuous advancement of science and technology, robotics is developing at an astonishing rate and is widely used in numerous fields, undertaking critical missions. Robots can replace highly repetitive and complex production tasks previously performed by humans, significantly improving production efficiency while ensuring consistent product quality. Moreover, robots can be deployed in hazardous environments, effectively enhancing operational safety [

1]. Due to their outstanding advantages in production, robots are now extensively applied in agriculture [

2], healthcare [

3], nuclear industry [

4], aerospace [

5], and many other fields.

Traditional calibrated systems refer to those where the system parameters (e.g., camera intrinsic and extrinsic parameters, distortion coefficients) are precisely calibrated using specific methods before processing image or sensor data. For visual systems, it is also necessary to calibrate the camera parameters and the hand–eye coordinate transformation. The accuracy of these parameters directly affects overall performance, imposing significant limitations in practical applications [

6]. To overcome the limitations of calibrated visual servoing, researchers have proposed uncalibrated visual servoing systems [

7,

8,

9,

10]. Uncalibrated visual servoing systems do not require parameter calibration but can accurately control robots by analyzing real-time image features, combining the robot’s current state information, and using advanced control algorithms to compute the system’s control input for the next time step. Compared to traditional calibrated systems, uncalibrated systems eliminate the need for precise geometric or kinematic model calibration, reducing system complexity and improving adaptability in practical applications.

With the deepening of research on uncalibrated visual servoing, Model-Free Adaptive Control (MFAC) has gradually gained attention due to its independence from system models. Model-Free Adaptive Control, as an advanced control methodology that does not rely on precise mathematical models of controlled objects, is fundamentally characterized by dynamically adjusting control strategies through online acquisition of system input–output data, rather than depending on a priori mechanistic models for control law design. Based on methodological differences, existing MFAC approaches can be primarily classified into two implementation paradigms. The first category encompasses dynamic linearization-based methods, which construct time-varying linear approximation models through online estimation techniques of pseudo-gradient or pseudo-Jacobian matrices. While these methods retain the structural assumption of local system linearization, they completely eliminate dependence on global model information. The second category comprises fully data-driven model-free methods. These approaches directly establish nonlinear mapping relationships based on input–output data or employ intelligent algorithms (such as neural networks, fuzzy logic systems, etc.) to generate control laws, thereby fundamentally circumventing the modeling process inherent in traditional control methodologies. For the quintessential nonlinear control problem of robotic motion control, scholars in the control field have proposed various specialized model-free adaptive control methods.

In [

11], a hybrid adaptive disturbance rejection control (HADRC) algorithm was proposed, which integrates dynamic linearization, disturbance observers, and fuzzy logic control to significantly improve the control performance of inflatable robotic arms. Dynamic linearization is suitable for multiple scenarios, disturbance observers enhance anti-disturbance capabilities, and fuzzy logic control effectively handles highly nonlinear and uncertain systems. In [

12], a neural network-based model-free control method was proposed, which uses neural network approximation techniques and position measurements to estimate uncertain Jacobian matrices, significantly improving the adaptability and accuracy of continuum robots in complex environments. Additionally, for the dynamic uncertainty and saturation constraints of rehabilitation exoskeleton robots, [

13] proposed a data-driven model-free adaptive containment control (MFACC) strategy, which linearizes the dynamic system into an equivalent data model and designs an improved model-free controller to enhance control performance in complex environments. For the nonlinear dynamics of NAO robots in robust walking, [

14] proposed a model-free method based on time-delay estimation (TDE) and fixed-time sliding mode control, which uses TDE to estimate system dynamics in real-time and combines a fixed-time observer with an improved exponential reaching law (MERL) to enhance the stability and trajectory tracking accuracy of the control system.

Although model-free control methods do not rely on precise system models and have shown significant advantages in handling complex dynamic systems, their overall performance still has limitations. First, these methods have limited adaptability to environmental changes, especially in highly nonlinear, uncertain, or strongly disturbed scenarios, where control accuracy and stability may be affected. Second, the design of model-free control often relies on empirical criteria and the selection of algorithm parameters, which poses certain limitations for complex control tasks in high-dimensional spaces. Additionally, traditional model-free control methods struggle to fully utilize large amounts of online data, limiting their potential for dynamic optimization and long-term performance improvement.

Reinforcement Learning (RL), with its core mechanism of autonomously learning optimal policies through interaction with the environment, provides a novel approach to overcome traditional challenges in robotic arm visual servoing [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. Its key advantages lie in eliminating the need for precise robot kinematics/dynamics models or cumbersome camera calibration, significantly reducing system complexity, as well as its exceptional capability in high-dimensional policy generation—enabling direct learning of complex control strategies from high-dimensional visual inputs (e.g., camera images). These strengths have led to the widespread application of RL in robotic arm visual servoing tasks, such as target localization, grasping, trajectory tracking, and obstacle avoidance [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24].

To address diverse task requirements, the RL algorithm framework has continued to evolve. Early value-based methods (e.g., Deep Q-Network (DQN) [

25]) successfully tackle simple tasks with discrete action spaces, such as image-based target localization, but struggle to handle the continuous action spaces required for robotic arm control, often resulting in non-smooth motions. To overcome these limitations, policy gradient-based Actor–Critic methods (e.g., Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (DDPG) [

26,

27], Soft Actor–Critic (SAC) [

28]) have emerged as the dominant approach. These methods directly output continuous actions and demonstrate superior performance in complex dynamic environments, including high-DoF precise positioning, smooth trajectory tracking, and multi-task learning. However, such methods heavily rely on online environment interaction for extensive trial-and-error learning, posing significant safety risks and high training costs when deployed on real robotic arms. Additionally, the sim-to-real transfer challenge further limits their practical efficiency.

To overcome the bottlenecks in data collection efficiency and security associated with online interaction, offline reinforcement learning (Offline RL) has emerged accordingly. Its core idea is to utilize a pre-collected static experience dataset for training, thereby completely avoiding the risks and costs of online interaction. Among various Offline RL solutions, the Twin Delayed Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient Algorithm with Behavior Cloning (TD3+BC) [

29] represents a simple yet effective representative approach. This method introduces a behavior cloning (BC) regularization term into the Twin Delayed Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient Algorithm (TD3) [

30] framework, which explicitly encourages the agent’s policy to imitate behaviors present in the dataset. This constrains the policy from deviating excessively from the dataset distribution, thereby effectively suppressing overestimation of Out-of-Distribution (OOD) actions.

However, the TD3+BC method has critical limitations that constrain its performance ceiling. First, it inherits the clipped double Q-learning mechanism from TD3, which uses the minimum value of the outputs from two critic networks as the final Q-value estimate. Although this mechanism effectively mitigates the overestimation bias caused by a single network, it tends to yield overly conservative Q-value estimates in offline settings. This leads to timid policy updates, ultimately slowing convergence and potentially resulting in suboptimal solutions. Second, the strength of its BC regularization term depends on the scale of Q-values. This adaptive weighting can be unstable in certain scenarios, leading to either excessive or insufficient constraints.

To address the conservatism issue of TD3+BC, several improvements have been proposed in the literature. For instance, Conservative Q-Learning (CQL) [

31] introduces an explicit regularization term in the learning objective to directly penalize high Q-values for OOD actions, thereby learning a conservative lower bound of the Q-function. However, this approach itself may cause severe underestimation. Implicit Q-Learning (IQL) [

32], on the other hand, takes a different path by entirely avoiding value function queries for OOD actions. Instead, it employs a technique called expectile regression to implicitly infer the Q-values of optimal actions, thereby achieving a better balance between mitigating extrapolation error and avoiding excessive conservatism. These methods collectively suggest that an ideal Offline RL algorithm must strike a more delicate balance between preventing overestimation and avoiding over-conservatism.

This study proposes an uncalibrated visual servoing control method for robotic manipulators based on improved offline reinforcement learning. The core innovation lies in the novel Multi-Network Mean Delayed Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient Algorithm with Behavior Cloning (MN-MD3+BC). This approach establishes multiple innovative mechanisms to achieve high-performance visual servoing control without system calibration.

The main contributions of this work are as follows:

- 1.

A multi-critic network integration architecture is adopted, which uses the mean output of multiple critic networks as the final Q-value estimate. This effectively reduces the estimation bias inherent in single-critic methods and improves the accuracy and stability of value function estimation, providing a more reliable foundation for policy optimization.

- 2.

A behavior cloning regularization term is incorporated into the policy gradient update, forming a dual-driven optimization mechanism combined with traditional Q-value maximization objectives. This approach constrains policy deviations from the dataset distribution while balancing the conservatism of behavior cloning through Q-optimization objectives, thereby enhancing policy optimization potential without compromising safety.

- 3.

A data recombination technology-based offline pretraining framework is proposed, which enhances experience reuse efficiency by reorganizing and utilizing pre-constructed high-quality datasets. This technology maximizes the utility of limited datasets while improving training efficiency, providing sufficient data support for end-to-end control policy learning.

- 4.

An end-to-end direct mapping strategy from visual features to joint control commands is designed, completely eliminating the dependence on complex camera parameter calibration and hand–eye calibration processes required in conventional methods. This significantly reduces the system’s requirement for precise calibration and environmental prior knowledge, providing a new solution for visual servoing control in complex scenarios.

Compared with existing approaches, this solution maintains control precision while significantly reducing the system’s dependence on precise calibration and environmental prior knowledge, offering a novel and effective approach for visual servoing control of robotic manipulators in complex scenarios.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 describes the experimental platform and outlines theoretical foundations.

Section 3 details the proposed offline reinforcement learning adaptive controller and the MN-MD3+BC algorithm architecture.

Section 4 presents validation results through both MATLAB (version R2023a) simulations and WPR1 robotic arm experiments. Finally,

Section 5 provides concluding remarks on the research findings.

2. Related Work

This section introduces the Programmable Universal Machine for Assembly (PUMA560) simulation platform and the WPR1 robotic arm experimental platform, and briefly outlines the theoretical foundations of robotic arm control.

2.1. Experimental Platforms

2.1.1. PUMA560 Simulation Platform

The PUMA560 (Programmable Universal Machine for Assembly) is a classic six-degree-of-freedom industrial robotic arm introduced by Unimation in the 1970s (Danbury, CT, USA). Known for its flexibility, high precision, and modular design, the PUMA560 has been widely used in both industrial and research fields. It supports complex trajectory planning and manipulation tasks, offering a large workspace and excellent load capacity. In academic research, the PUMA560 is often used to validate robotic control algorithms, such as inverse kinematics, trajectory planning, and visual servoing, due to its standardized kinematic and dynamic models. Its model is integrated into tools such as the MATLAB Robotics Toolbox and ROS, making it a classic platform for robotic control and simulation research.

In this paper, the built-in PUMA560 model from the Robotics Toolbox is used. The first three joints of the PUMA560 control the end-effector position, while the last three joints control the end-effector spatial attitude. Since this study focuses on target position tracking, the end-effector spatial attitude is ignored, reducing the problem to a three-degree-of-freedom control task.

2.1.2. WPR1 Robotic Arm Experimental Platform

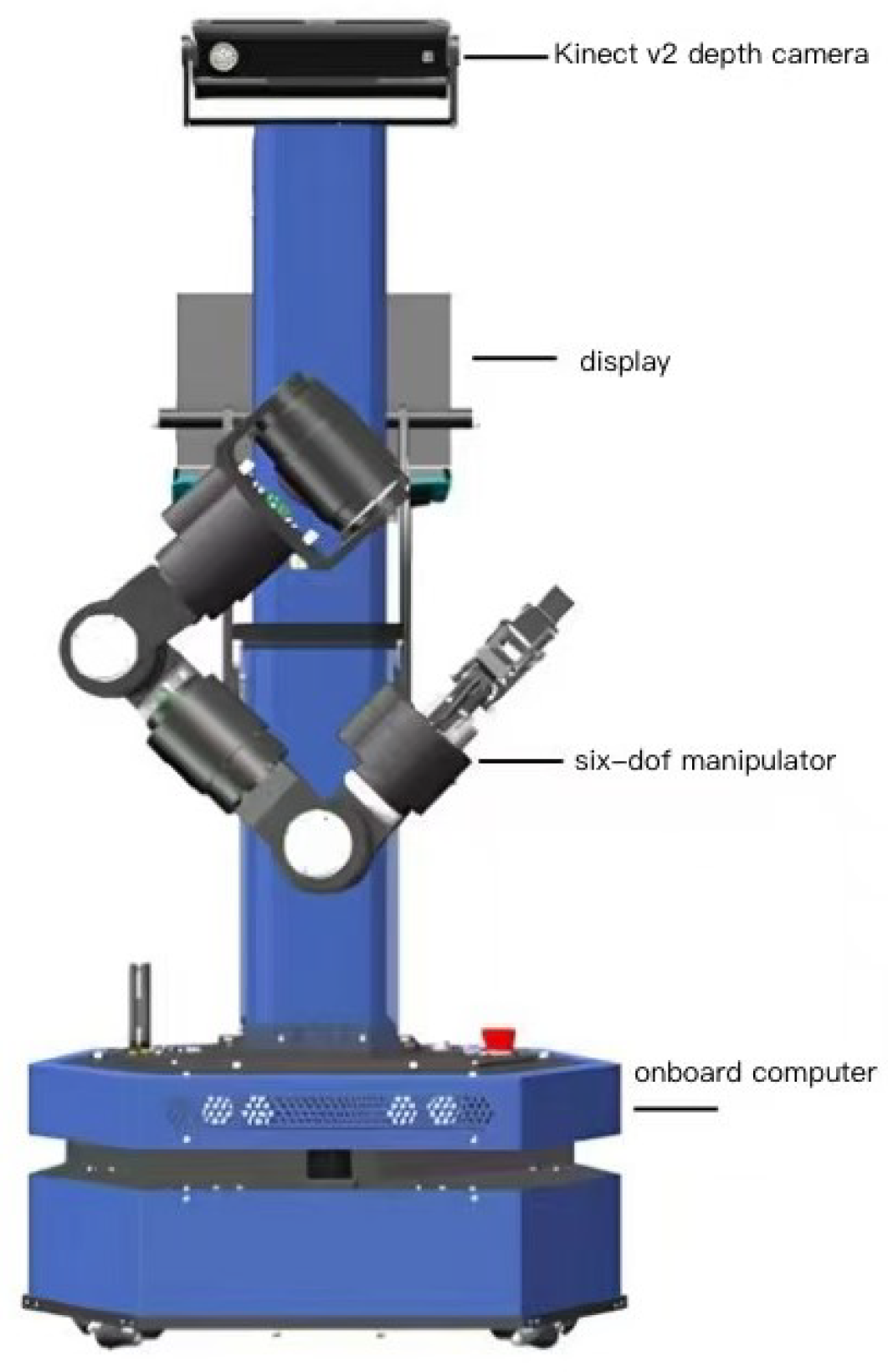

The WPR1 is a robotic arm platform designed for service-oriented applications, developed by Beijing Liubu Workshop Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China) Its main components include an onboard computer, a display, a high-precision six-degree-of-freedom robotic arm, and a wide-angle Kinect v2 depth camera (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). The robot features a safety-redundant design, ensuring high reliability while maintaining functional diversity. The WPR1 experimental platform is shown in

Figure 1.

The Kinect v2 depth camera is mounted at the top of the WPR1’s main body, providing a fixed-position setup. The six-degree-of-freedom robotic arm is installed in the middle of the main body, enabling an eye-to-hand visual servoing system. Additionally, the WPR1 is equipped with an onboard computer at the base and a micro-display at the top, allowing it to operate independently when powered on. The joint limits of the WPR1 robotic arm are listed in

Table 1.

2.2. D-H Parameter Method

The Denavit–Hartenberg (D-H) parameter method [

33] is a universal approach for modeling robotic arms. A robotic arm consists of a series of consecutive joints and links, and the D-H method standardizes the establishment of link coordinate systems by assigning a coordinate system to each link to describe its motion. The motion of the robotic arm in the workspace can be described using four parameters related to the

x and

z axes. This method simplifies the description of the transformation relationship between links using the following four parameters:

- (a)

Joint angle (): The rotation angle of joint about the -axis, defined as the joint angle. Rotating by makes the -axis and -axis parallel.

- (b)

Link offset (): The offset of joint along the -axis, describing the displacement from the origin of frame to the origin of frame along the -axis. Translating by makes the -axis and -axis collinear.

- (c)

Link length (): The length of link along the -axis, describing the distance between the -axis and -axis. Translating by makes the origins of the -axis and -axis coincide.

- (d)

Link twist (): The rotation angle of joint about the -axis, describing the rotation from frame to frame . Rotating the -axis about the -axis by aligns it with the -axis.

For prismatic joints, the link offset (

d) is the variable, while for revolute joints, the joint angle (

q) is the variable. In this paper, the MATLAB simulation is conducted specifically for the Puma560 model. Therefore, only the D-H parameters and joint motion ranges of the Puma560 are provided, as shown in the

Table 2.

2.3. Kinematic Analysis

Based on the D-H parameter method described in the previous section, the relationship between two consecutive links can be described using four parameters, which define the transformation matrix between link and link i. The transformation from coordinate frame to coordinate frame i is achieved through the following four standard steps: first, rotate by the joint angle about the -axis; second, translate by the distance along the -axis; then, translate by the distance along the -axis; and, finally, rotate by the angle about the -axis.

Following this procedure, the transformation matrix between two consecutive link frames,

and

i, can be established through a series of rotations and translations. The transformation matrix is given by Equation (

1):

From Equation (

1), the transformation matrix between two consecutive links can be accurately described. For a robotic arm with

M consecutive links, the end-effector pose relative to the base frame can be obtained by multiplying the transformation matrices of all links:

The transformation matrix in Equation (

2) contains

M joint variables. The actual values of these variables are obtained from joint sensors, and the transformation matrix for each link is calculated using Equation (

1). By multiplying these matrices, the pose of the end-effector frame relative to the base frame can be expressed as:

In Equation (

3),

R is the rotation matrix describing the orientation of the end-effector, and

P is the translation vector describing the position of the end-effector in space.

Based on the above conclusions, the homogeneous transformation matrix of the monocular camera relative to the base coordinate frame of the Puma560 in this paper is as follows:

2.4. Robotic Arm Visual Servoing Task

Robotic arm servoing tasks involve controlling the motion of the robotic arm to achieve precise manipulation of target objects, with applications in manufacturing, healthcare, and service industries. Kinematic modeling is a critical aspect of servoing tasks, as it describes the mapping between joint space and task space to achieve accurate end-effector positioning and spatial attitude control.

Using the D-H parameter method, the forward kinematics model can be established to compute the end-effector’s position and spatial attitude in task space based on joint angles. Conversely, inverse kinematics solves for the joint angles required to achieve a specific task, often requiring numerical methods due to the complexity of the robotic arm’s geometry.

In robotic arm servoing control, two main approaches are used: position-based servoing and vision-based servoing. Position-based servoing relies on precise geometric modeling and system calibration, using inverse kinematics to compute target joint angles and controllers to achieve desired trajectories. However, traditional methods are sensitive to model accuracy and calibration errors, limiting their performance in dynamic environments.

To address these limitations, vision-based servoing methods have been developed. Vision-based servoing uses real-time images from cameras to extract visual features and compare them with target features, adjusting the robotic arm’s motion based on the computed error. The integration of robot kinematics and vision-based servoing provides theoretical and technical support for complex tasks. However, in dynamic environments, traditional servoing methods may be affected by calibration errors, task complexity, and modeling limitations. As a result, data-driven methods such as reinforcement learning have gained attention, enabling robotic arms to learn control strategies directly from visual input, further improving the precision and adaptability of servoing tasks.

3. Methodology

For robotic arm visual servoing tasks, this paper proposes a visual servo control system framework based on the Multi-Network Mean Delayed Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient Algorithm with Behavior Cloning (MN-MD3+BC), designed to achieve efficient and precise control of complex tasks. The system fully leverages the advantages of offline reinforcement learning by employing offline policy optimization to reduce the risks and costs associated with direct training in real-world environments, while effectively addressing control challenges arising from the system’s nonlinear characteristics and environmental disturbances in robotic arm manipulation. This section will comprehensively present the algorithmic architecture of MN-MD3+BC and its implementation in robotic arm visual servoing tasks. Detailed explanations will focus on the core modules of the MN-MD3+BC algorithm, including (1) the neural network architecture design, (2) definitions of state space and action space, and (3) construction of the reward function.

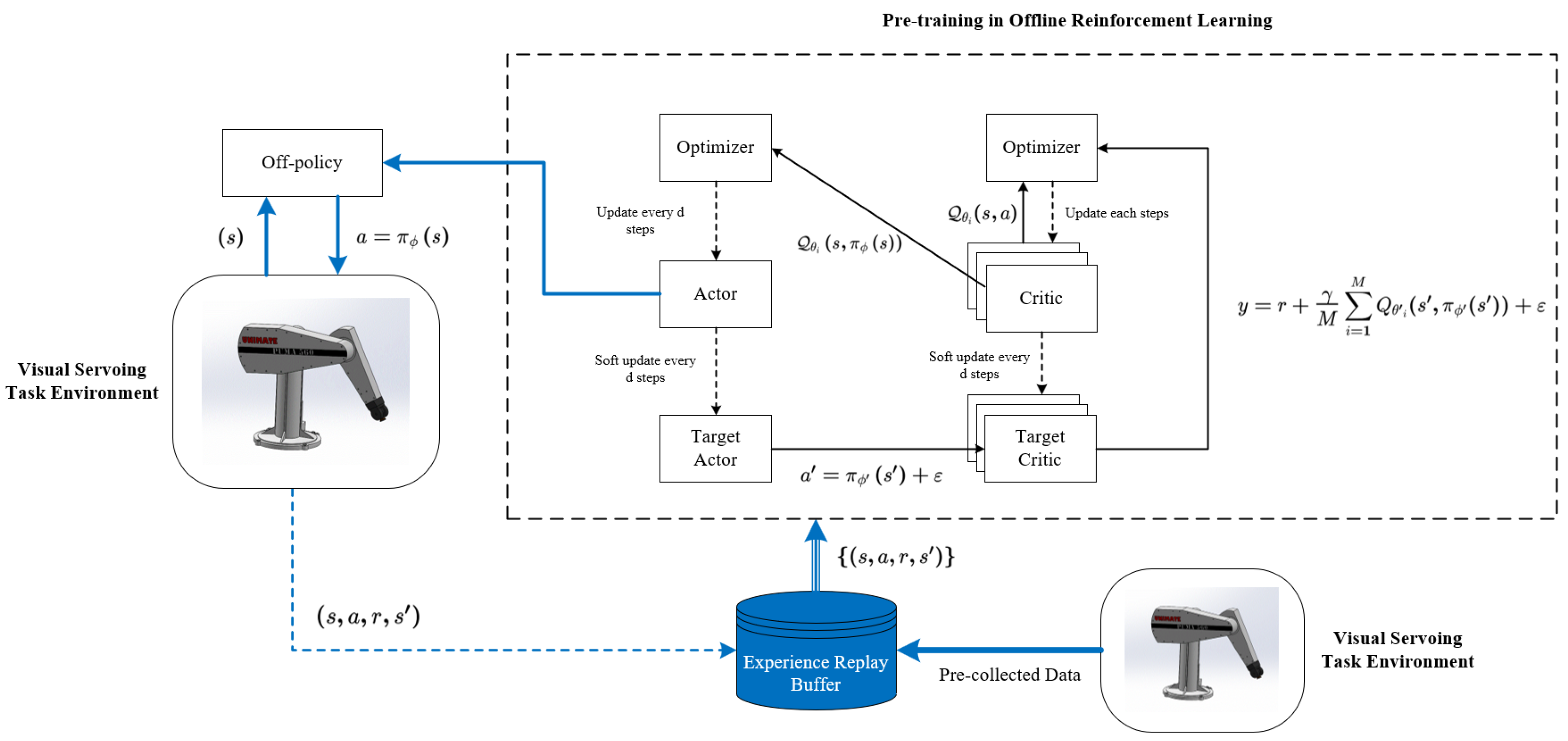

3.1. MN-MD3+BC Algorithm Architecture Framework

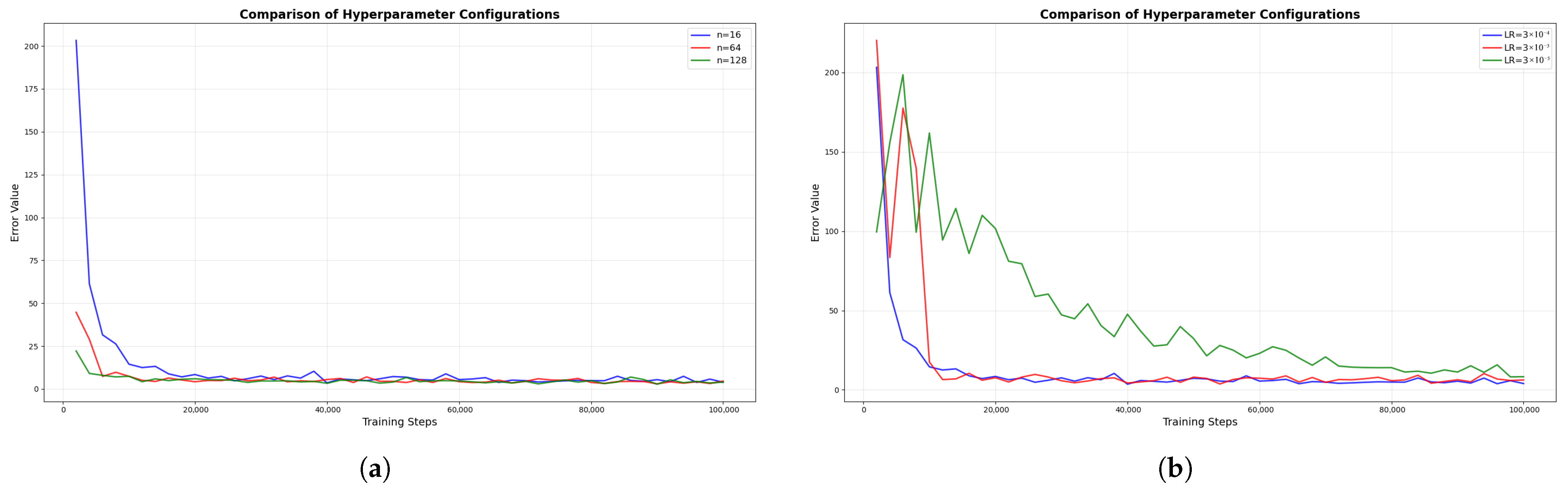

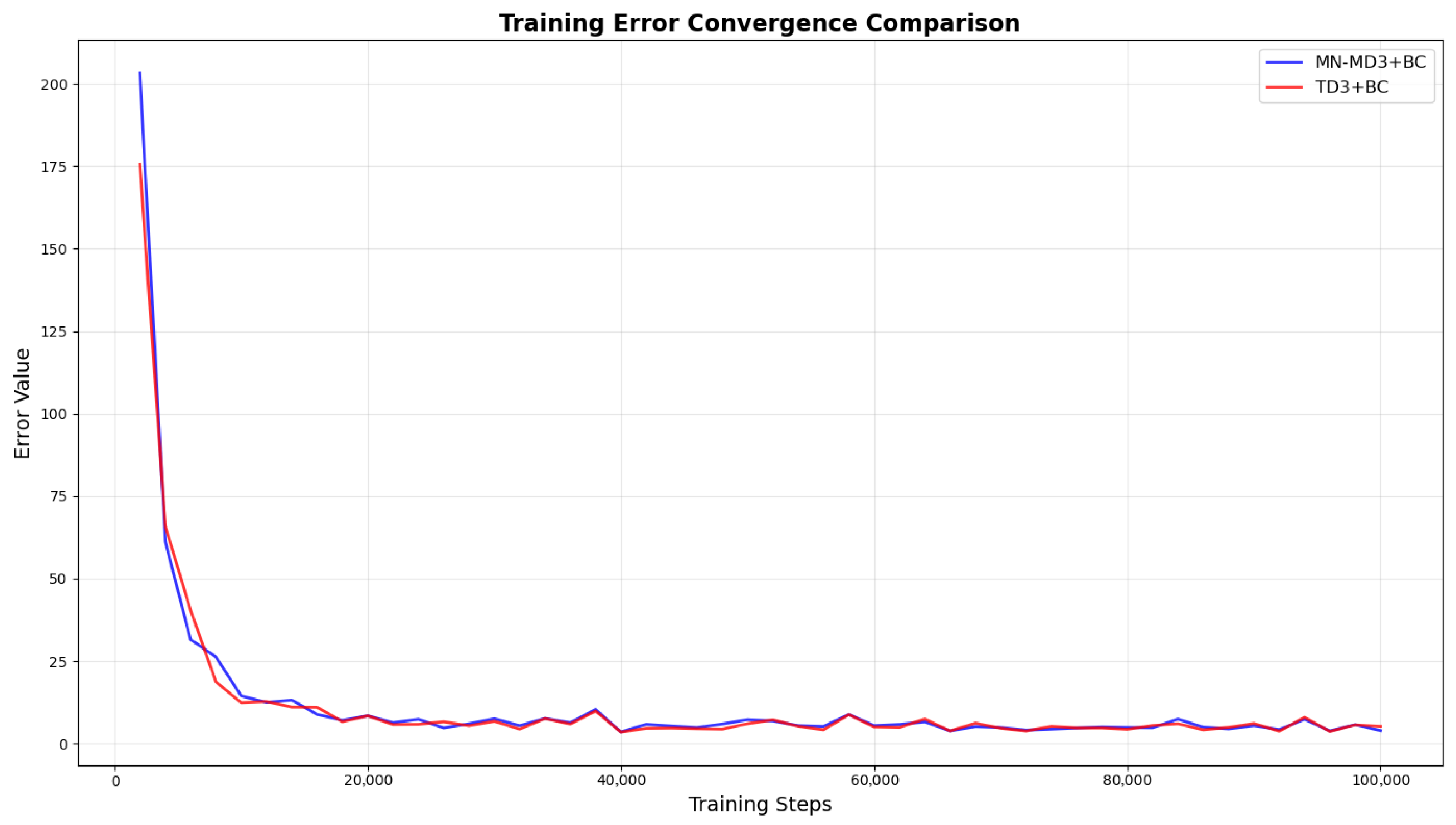

The MN-MD3+BC algorithm, building upon the TD3 framework, innovatively employs three Critic networks to enhance decision-making reliability (as shown in

Figure 2). The choice of three—rather than more—networks reflects a critical trade-off between performance and efficiency. Averaging across three networks effectively balances estimation bias and variance, providing sufficiently robust evaluation. Adding a fourth or more networks would yield negligible performance improvements, while significantly increasing computational costs and the risk of overfitting. Therefore, “three” represents the optimal number that maximizes robustness without compromising real-time performance.This architecture employs three independent critic networks to evaluate policies from multiple perspectives, utilizing mean value computation for target Q-value estimation, which effectively mitigates potential estimation biases inherent in single-critic approaches. The algorithm implements a dual-objective optimization mechanism that dynamically weights behavior cloning loss against Q-value maximization objectives. This design ensures policy constraints remain within dataset-supported boundaries while preserving exploration capabilities in high-performance regions. In practical control processes, this balance manifests as the decision network’s dual capability: it reliably tracks effective actions from demonstration data while autonomously optimizing more precise motion trajectories.

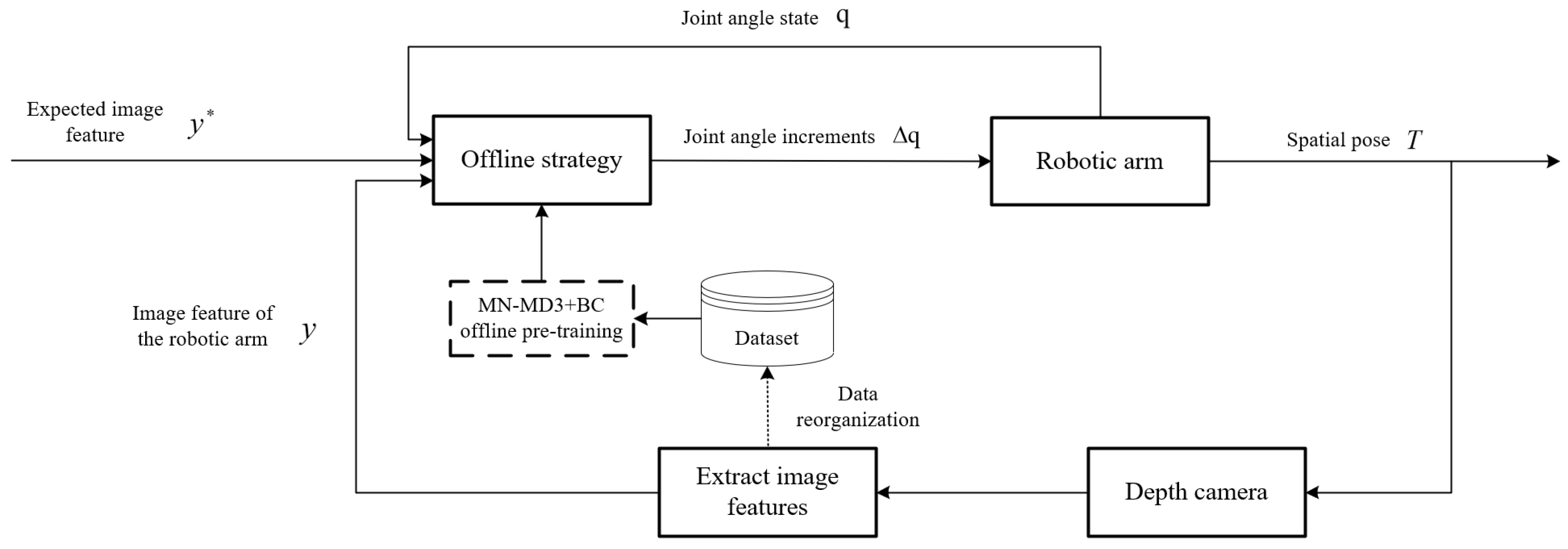

In the robotic arm visual servoing control process (as shown in

Figure 3), the system first extracts image features from camera-captured images. These extracted image features, combined with desired image features and current joint angles, form the state information that is fed into the policy network. The policy network then computes the joint angle variations based on the trained offline policy. These computed joint angle variations are subsequently executed by the robotic arm to perform the required movement. Following the arm’s motion, the system captures new image features again and repeats the aforementioned steps. This cyclic process continues iteratively until the visual servoing control task is successfully completed.

3.2. Network Structure Design

The network architecture of the Twin Delayed Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (TD3) algorithm [

30] consists of one policy network (Actor), two independent value networks (Critic), and their corresponding target networks. The policy network takes the current environmental state as input and outputs optimal continuous actions for environmental interaction. The Critic networks receive both state and action as inputs to independently estimate the Q-value of actions.

In conventional Actor–Critic frameworks, the Actor and Critic networks typically employ relatively consistent architectures, where the Critic network serves as an approximation of the state-action value function to evaluate actions generated by the Actor policy network. However, to address the overestimation bias inherent in traditional methods, TD3 adopts the Double Q-learning approach by utilizing two separate Critic networks to independently estimate Q-values and using their minimum for target updates. Although this design effectively mitigates overestimation bias, it may result in persistently low value estimation of actions output by the Actor network, thereby affecting the algorithm’s convergence speed and the conservativeness of the policy.

To address this limitation, we extend the TD3 framework by introducing

M Critic networks with corresponding target networks. Instead of taking the minimum Q-value, we compute the mean across all Critic networks:

where

M denotes the number of Critic networks,

r denotes the reward value corresponding to the current action,

denotes the discount factor, and

denotes next state after taking the action. In this and the following equations,

and

denote the parameters of the Actor and Critic networks, respectively, while

and

represent the parameters of their corresponding target networks.

Furthermore, for target policy regularization, noise is incorporated into the target policy:

where

represents target policy regularization noise.

The Critic network parameters

are updated by minimizing the following loss function:

where

denotes a mini-batch of size

N sampled from the experience replay buffer.

Although the TD3 algorithm has demonstrated excellent performance in online reinforcement learning, its core design relies on continuous interaction with the environment, which makes it unsuitable for direct application in offline reinforcement learning. In offline scenarios, the TD3 algorithm requires generating new actions during policy updates. However, these generated actions may deviate from the distribution of the offline dataset, leading to the distributional shift problem. Specifically, this shift can cause the value function to erroneously overestimate the policy’s performance, resulting in performance degradation or even policy collapse. To address the distributional shift issue in offline reinforcement learning, we have introduced Behavioral Cloning (BC) into the policy update process. The BC loss constrains the learned policy to remain close to the behavioral policy that generated the dataset:

The combined policy loss becomes a multi-objective optimization problem:

where

is a weighting factor that controls the relative importance of the behavior cloning term. The value of

c is set to 2.5 in this paper.

The target networks undergo soft updates as follows:

where

is the learning rate for target network updates.

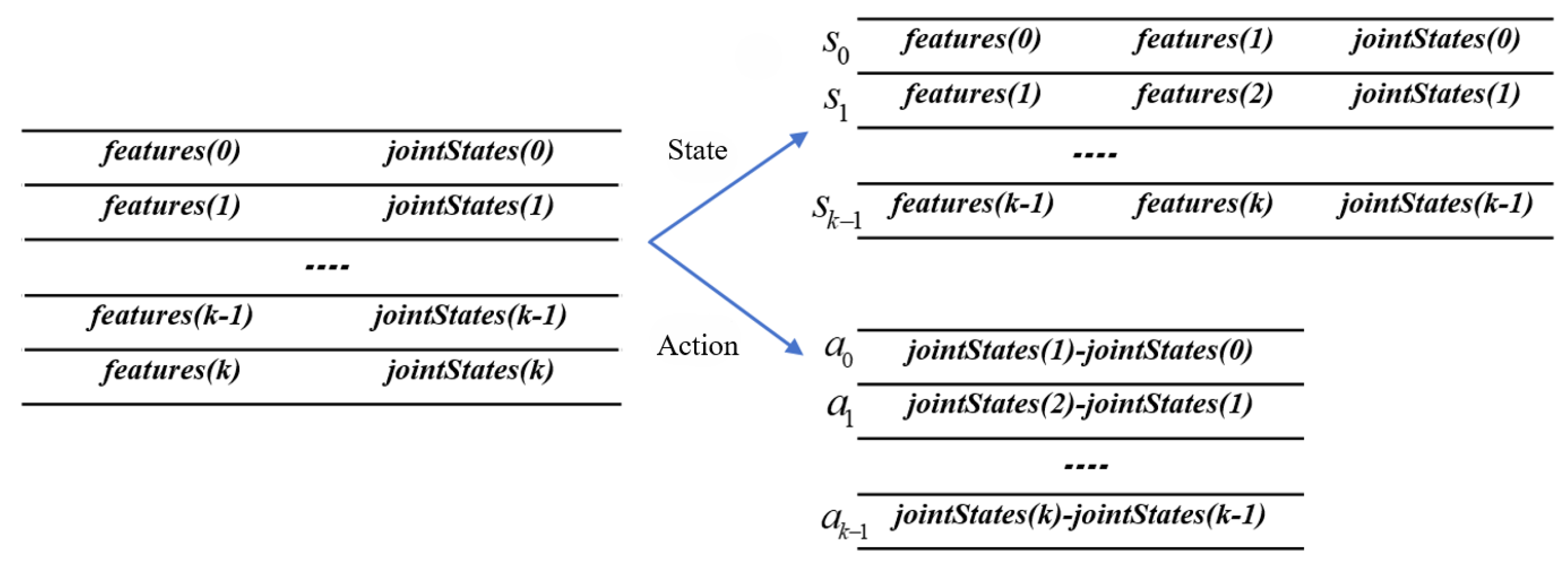

3.3. State Space Definition

The state space of a robotic arm refers to the observed state information during its operation, encompassing both environmental states and the robotic arm’s own states. In the context of robotic arm control problems, the state space may include the robotic arm’s joint angles, the position of the end-effector, the position of the target point, and so forth. These elements serve as input variables that enable the robotic arm to acquire state information, based on which, along with the current policy, it selects appropriate actions to execute and subsequently obtains corresponding reward values.

For the calibration-free visual servoing task investigated in this study, environmental state perception primarily relies on visual sensor information. Specifically, the system employs a depth camera as the visual sensor, with acquired image features including the pixel’s horizontal coordinate u, the pixel’s vertical coordinate v, and the pixel’s depth value . These features collectively constitute the state space representation of the system. The robotic arm’s own state refers to the changing state of its structure, specifically the angle values of each joint. Due to the issue of degrees of freedom in robotic arms, a high degree of freedom robotic arm can have multiple inverse solutions for the same end-effector position. Therefore, the current joint angle values are necessary to seek the optimal policy that enables reaching the next position with minimal movement.

Since this paper focuses on the problem of tracking the target position of the robotic arm’s end-effector, the issue of the end-effector’s orientation is temporarily disregarded. The tracking of the robotic arm’s target position is a stochastic and continuous process, and the sole introduction of the current target position is not applicable to all tracking tasks. Consequently, this paper introduces the expected image feature of the target at the next moment into the state space. This feature value can be calculated through pre-set parameters or an independent target prediction algorithm, satisfying the requirements of positioning and tracking tasks. The state space is defined as:

where:

denotes the current image features with pixel coordinates and depth from the depth camera;

represents the expected target image features;

is the joint angle vector with n degrees of freedom.

3.4. Action Space Definition

To accomplish the robotic arm target tracking task, it is necessary to ensure that the end-effector of the robotic arm follows the movement of the target. The required state information, including environmental data and the joint angles of the robotic arm, has already been acquired. The action space should aim to minimize the distance between the end-effector position and the target position by providing the required joint angle changes for the next time step. These changes are then accumulated to the current joint angles, enabling the robotic arm to continuously adjust its angles and, consequently, the position of the end-effector. The action space defines the joint angle increments for trajectory tracking:

where each

is bounded by the mechanical constraints

.

3.5. Reward Function Design

The key to robotic arm target tracking lies in the acquisition of reward values, which represent the objective of the task and drive the learning strategy of the robotic arm. Without proper rewards, the arm would engage in endless, aimless movements. Therefore, designing an appropriate reward function is one of the critical elements in solving reinforcement learning problems.

In this section, with the task background of uncalibrated visual target tracking by a robotic arm, the reward function design must be based on the relative distance between the end-effector features and target features in the visual sensor’s frame, while also considering the magnitude of actions. Consequently, the proposed reward function consists of two components: distance reward and action reward, as expressed in the following equation:

with feature distance computed as:

where

The values of and , set to 10 and 1, respectively, are weighting coefficients that prioritize tracking precision.

is the joint angle change vector.

3.6. Algorithm Training Process

In order to more clearly understand the implementation process, we propose the following pseudo code (Algorithm 1) for the training process of the MN-MD3+BC algorithm.

| Algorithm 1 MN-MD3+BC training procedure |

Initialize: Actor network parameters and target M Critic networks and targets Experience replay buffer with normalized dataset for step to do Sample mini-batch Update Critic networks by minimizing Equation ( 7) if step then Update Actor network via Equation ( 9) Soft update target networks: end if end for

|

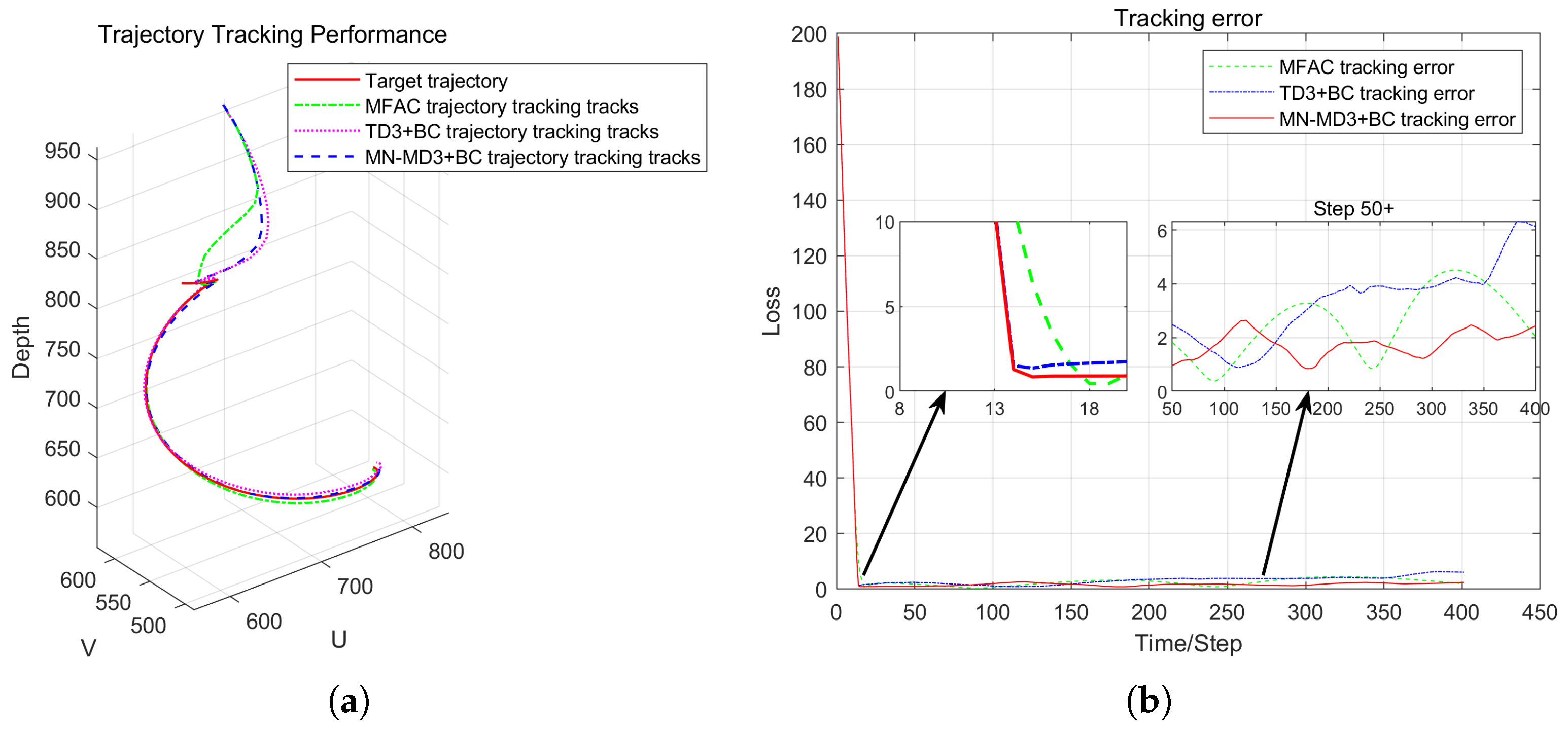

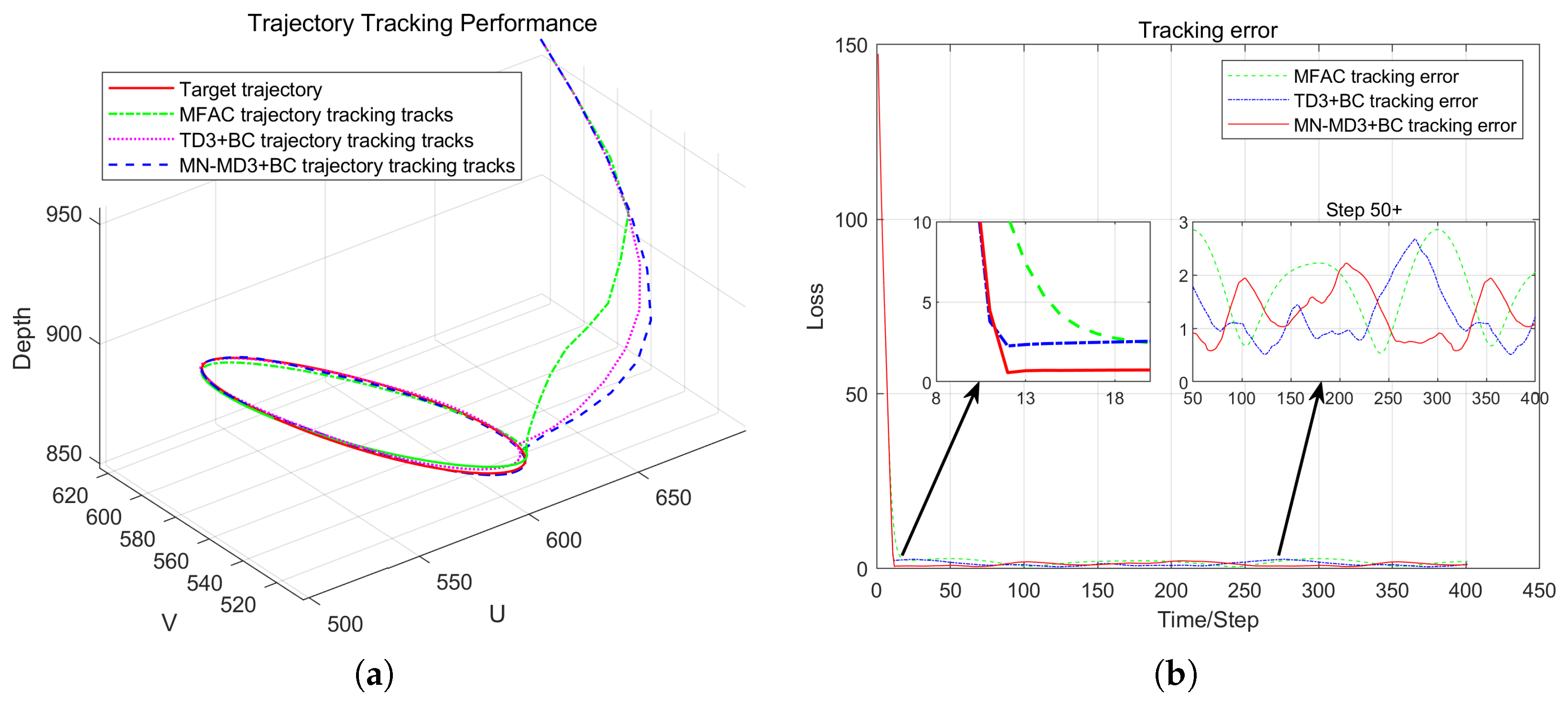

5. Conclusions

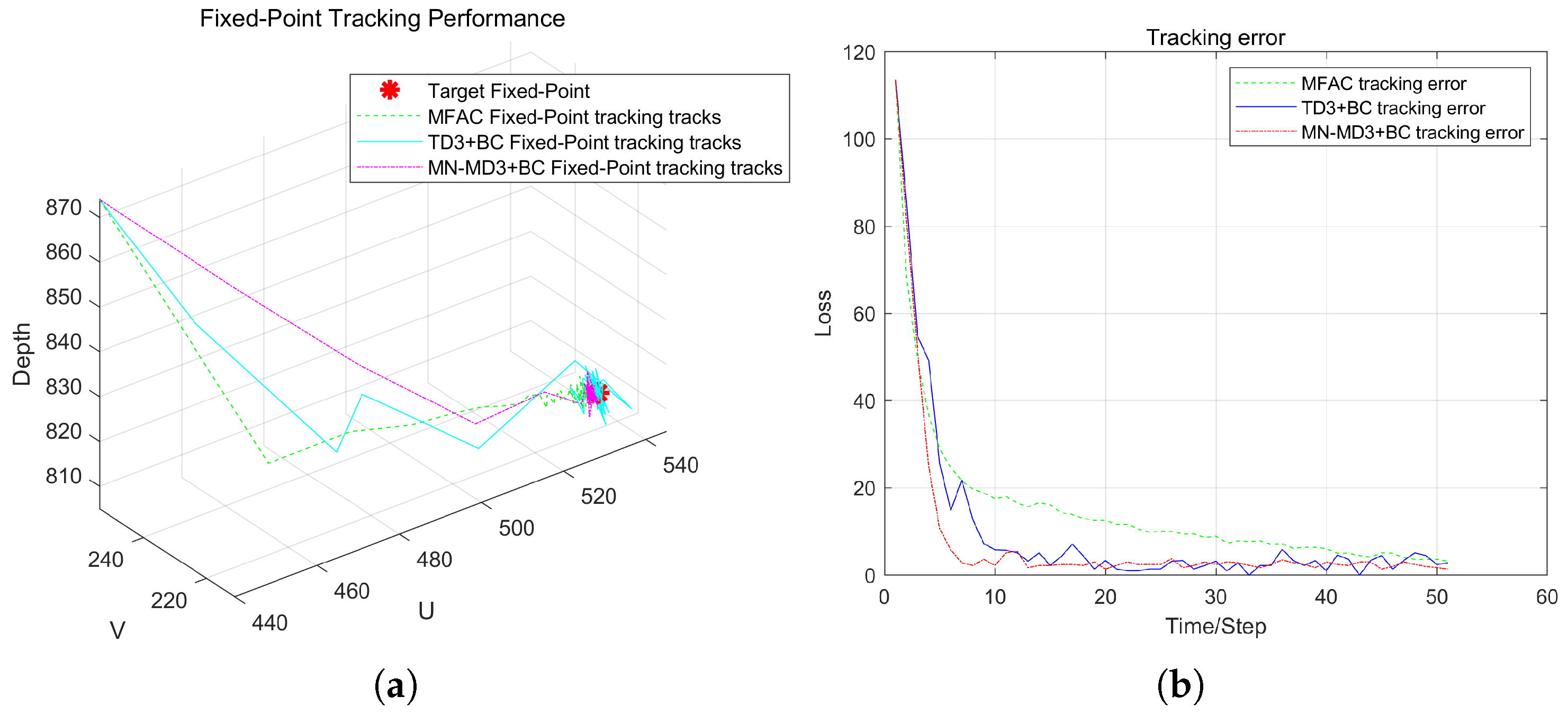

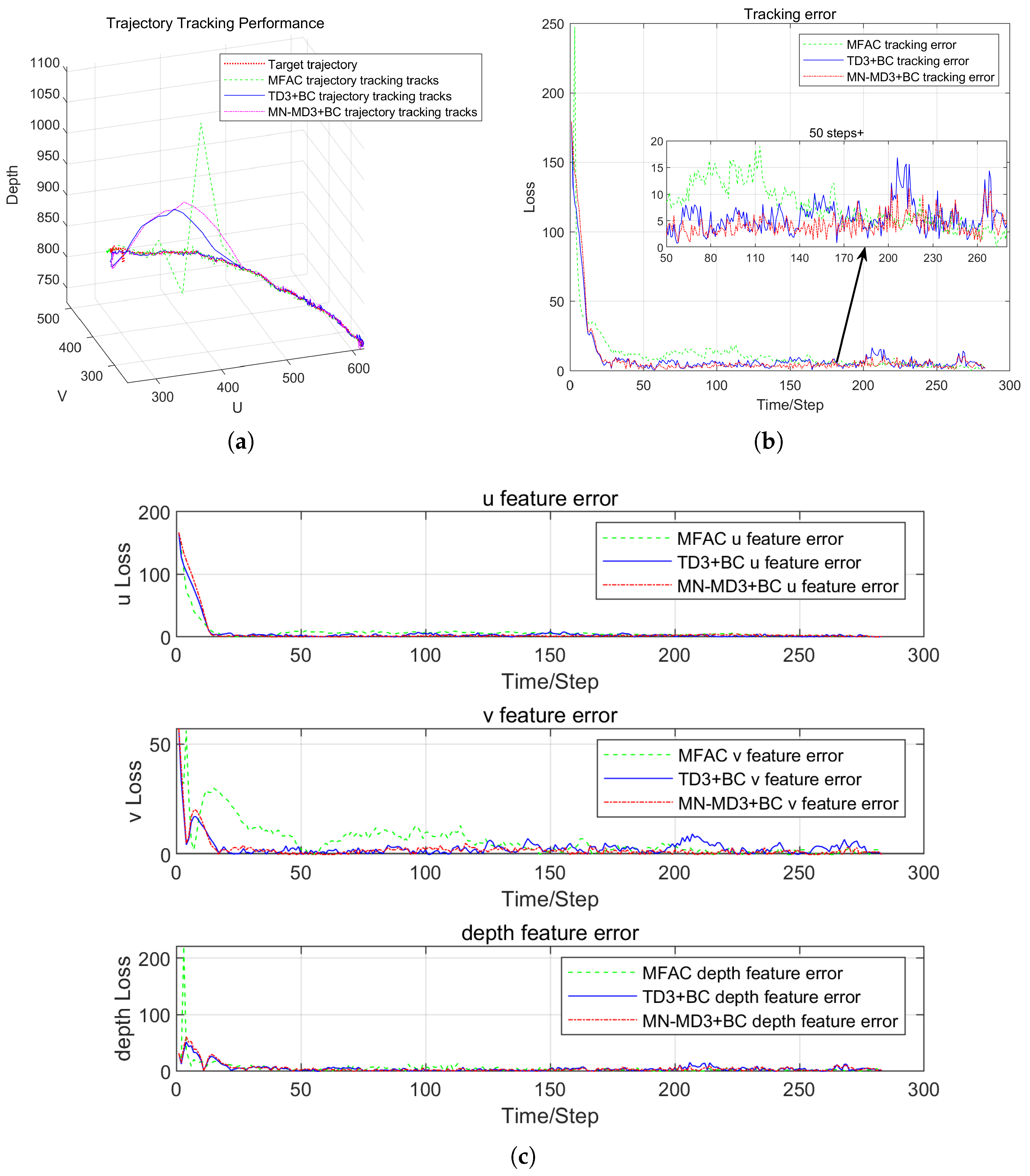

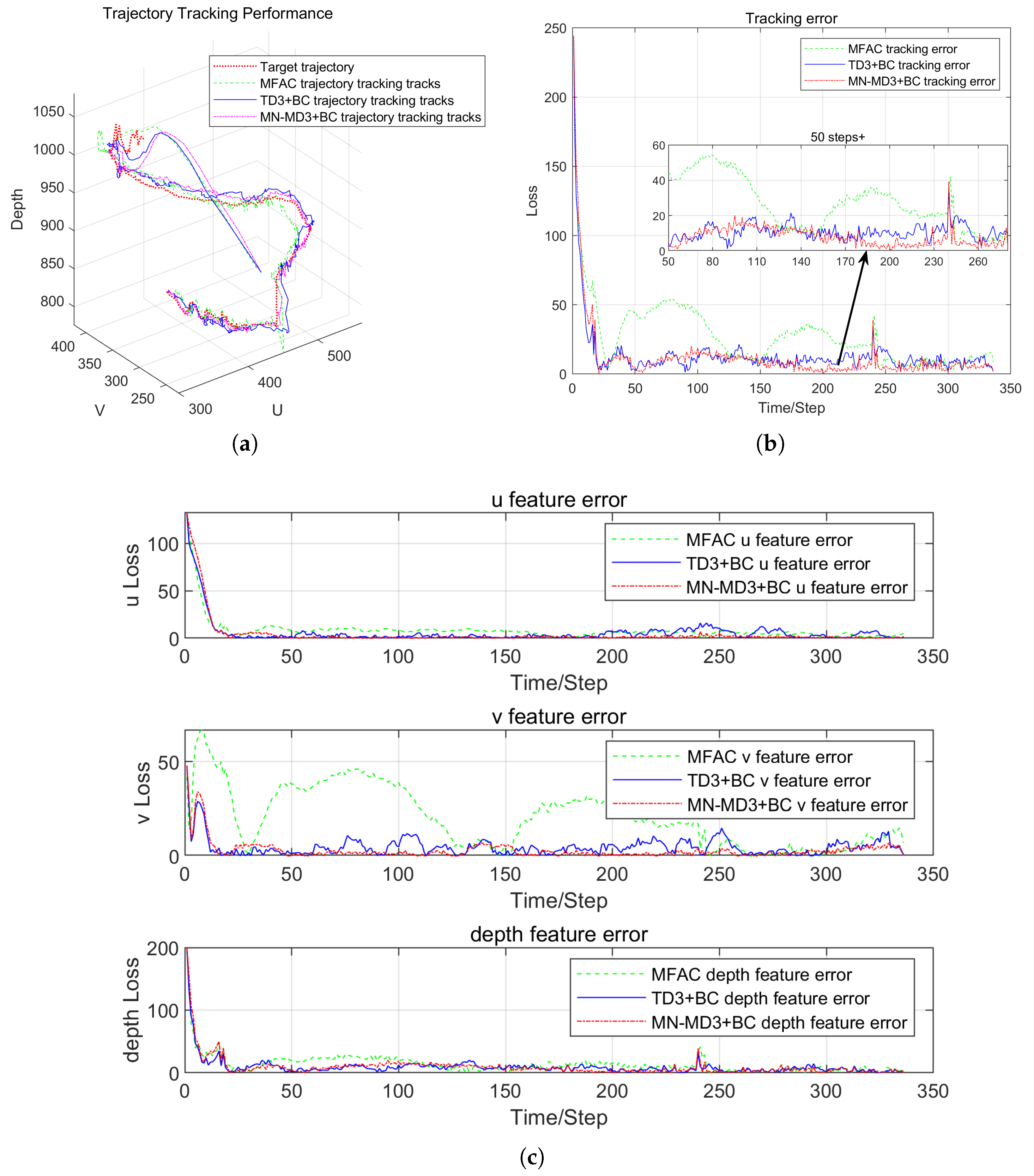

Different from the existing methods for designing robotic arm vision controllers based on online reinforcement learning, this paper proposed a deterministic policy gradient offline reinforcement learning algorithm based on multi-evaluation network averaging (MN-MD3+BC algorithm) from the perspective of real-world applications, in response to the problems of training inefficiency and underutilized data faced by online reinforcement learning in a high-dimensional state space. The algorithm made targeted improvements on the basis of the TD3+BC offline reinforcement learning algorithm, especially achieving breakthroughs in performance optimization in the uncalibrated visual servoing task. The MN-MD3+BC algorithm improves the accuracy of the value evaluation by means of multi-evaluating network averaging, and at the same time enhances the robustness of the strategy, effectively avoiding the common overestimation bias problem of traditional reinforcement learning algorithms in the process of strategy convergence. Compared with online reinforcement learning, the algorithm substantially reduces the dependence on real-time environment interaction during the training process by pre-training the policy network offline, which enhances the practicality in real robotic arm control tasks.

In order to verify the performance of the proposed algorithm, comparative experiments were conducted in Matlab custom simulation environment and on the actual WPR1 robotic arm experimental platform. The experimental results showed that the MN-MD3+BC algorithm exhibits significant advantages in terms of tracking accuracy, error convergence speed, and system stability compared with the traditional model-free control method. Especially when dealing with visual servo tasks such as complex trajectories and sharp turns, the MN-MD3+BC algorithm is able to converge to the target trajectory more quickly and with smaller error fluctuations, showing better robustness and control performance.

The proposed MN-MD3+BC algorithm not only overcomes the limitations of traditional calibration-based methods but also effectively addresses challenges faced by online reinforcement learning in real-time control tasks, offering an efficient and practical offline reinforcement learning solution. Through simulations and physical experiments, the research outcomes provide new insights and references for future studies in the field of visual servoing control for robotic manipulators, demonstrating significant theoretical value and application potential. However, several challenges remain before the method can be deployed in real industrial settings. First, although offline reinforcement learning reduces dependence on environmental interaction, its performance is highly reliant on the diversity and coverage of the training data, which may lead to limited generalization capability when encountering unseen working conditions. Furthermore, since behavior cloning strategies may cause policy updates to rely excessively on historical data, the exploratory ability of the policy in unfamiliar environments could be constrained. In particular, the scalability of the algorithm under more challenging multi-target scenarios and dynamically changing lighting conditions requires further validation. Although the experimental setup already includes motion-induced jitter noise and the algorithm exhibits inherent robustness to some extent, its target recognition and decision-making mechanisms may need adjustments when handling multiple targets with different shapes and priorities simultaneously. Significant illumination variations may also affect the stability of visual feature extraction. While the training data incorporated a certain degree of lighting diversity, the algorithm’s performance under extreme illumination conditions still warrants systematic evaluation. Therefore, future research will focus on enhancing the algorithm’s generalization in complex scenarios—particularly its adaptability and robustness in multi-target collaboration and dynamically changing lighting conditions—while optimizing the exploration–exploitation trade-off to achieve a more efficient and reliable visual servoing control system.