Overburden Damage in High-Intensity Mining: Effects of Lithology and Formation Structure

Abstract

1. Introduction

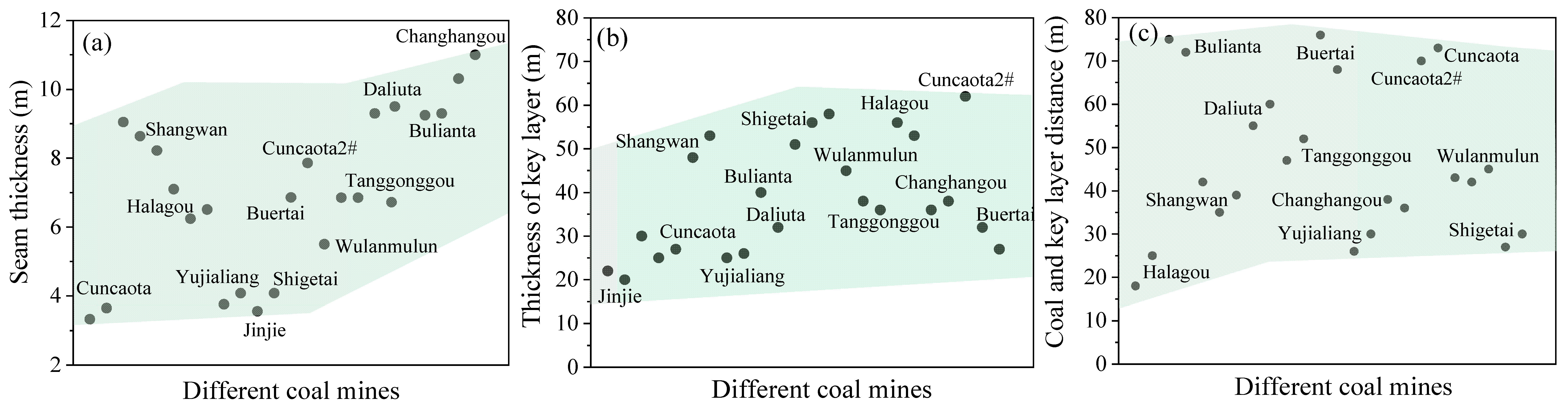

2. Characteristics of High Intensity Mining in Shendong Mining Area China

3. Scaled Model Research Plan

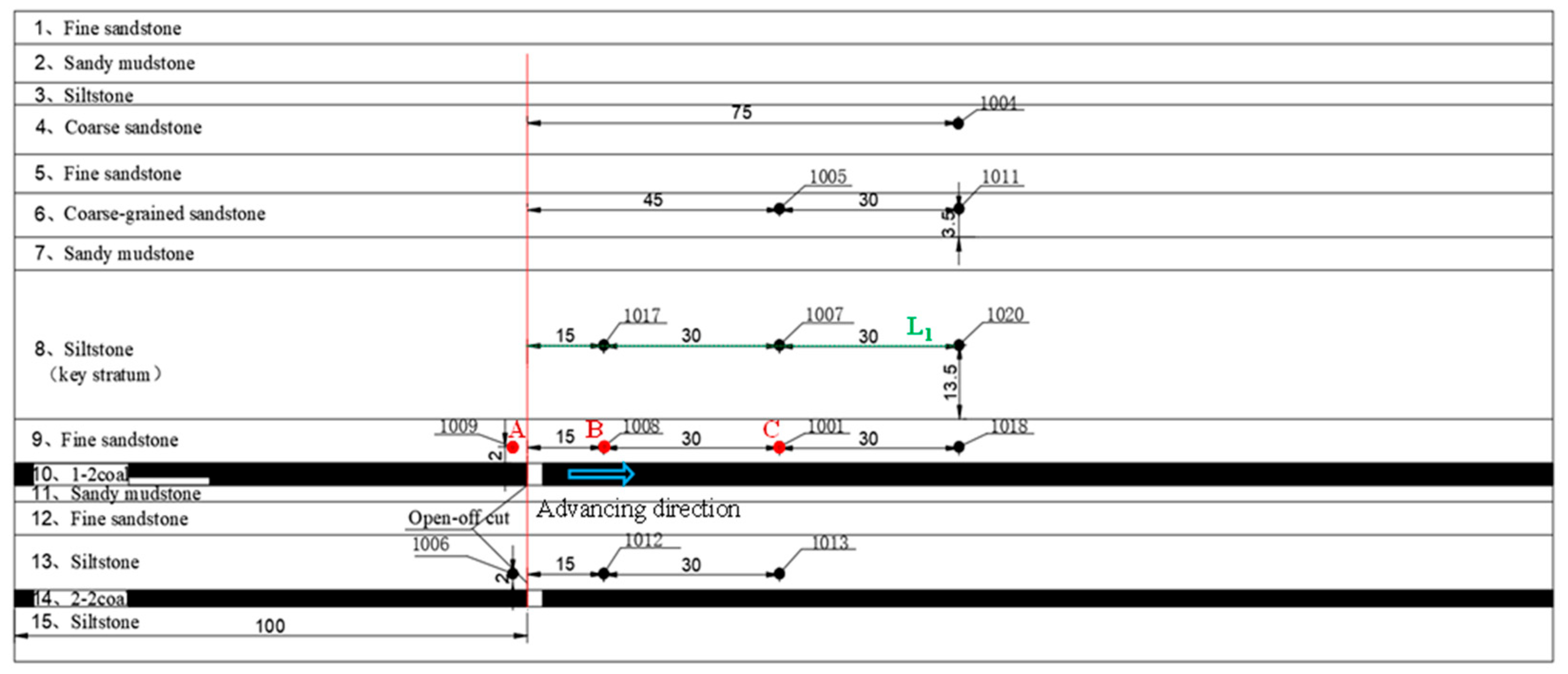

3.1. Physical Similarity Test Setup and Model Parameters

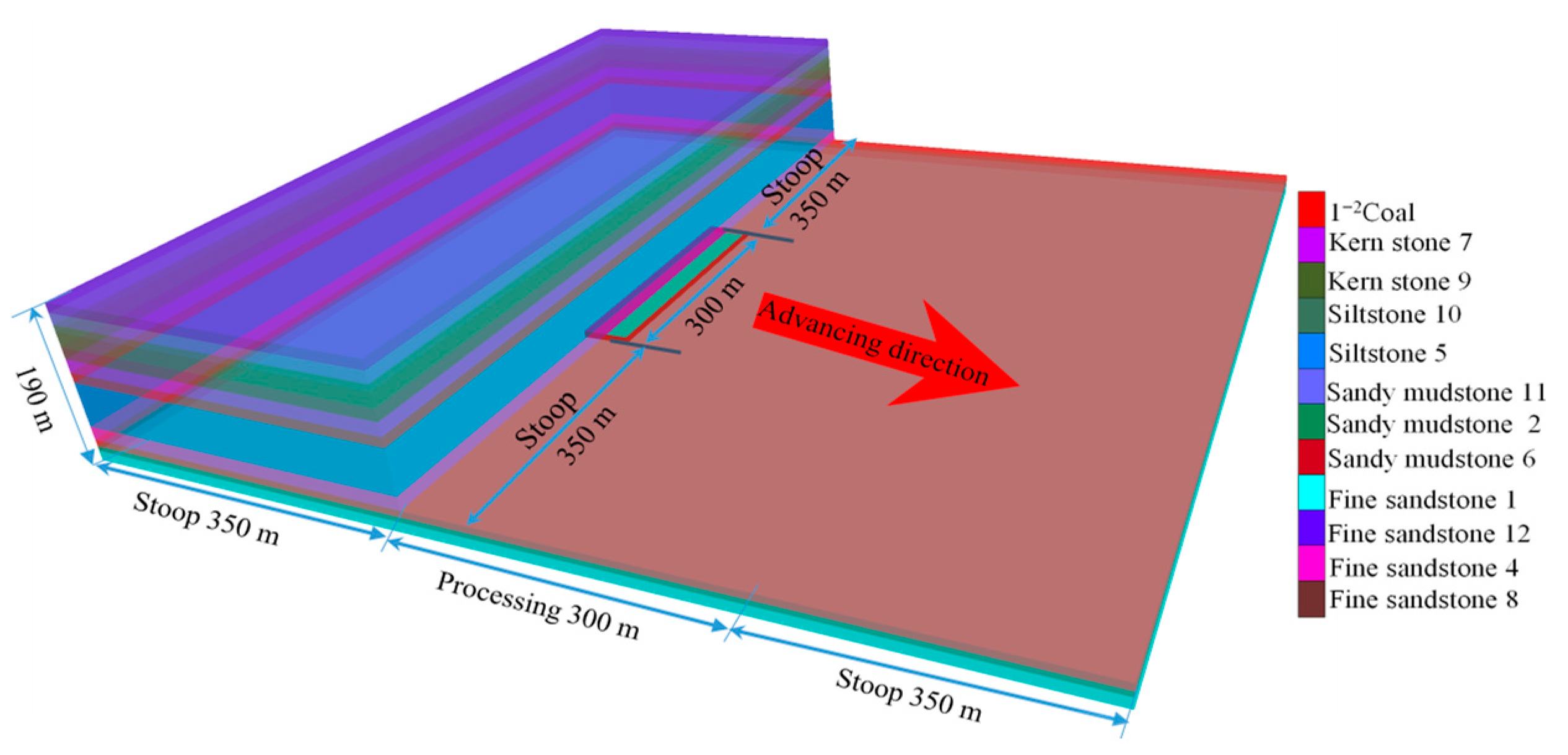

3.2. Numerical Simulations and Model Parameters

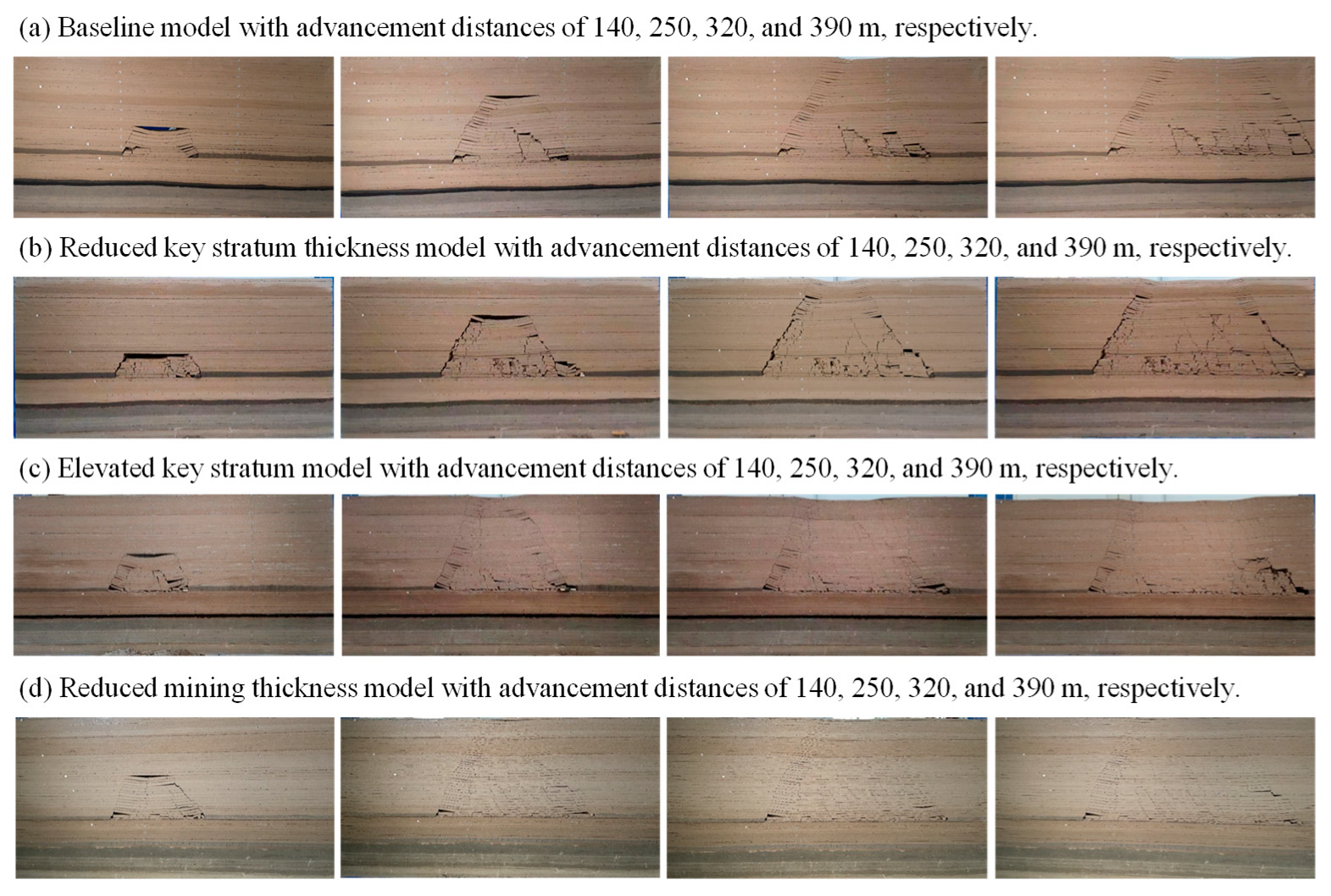

4. Experimental Observation of Overburden Damage Progression Under Different Lithology Combinations

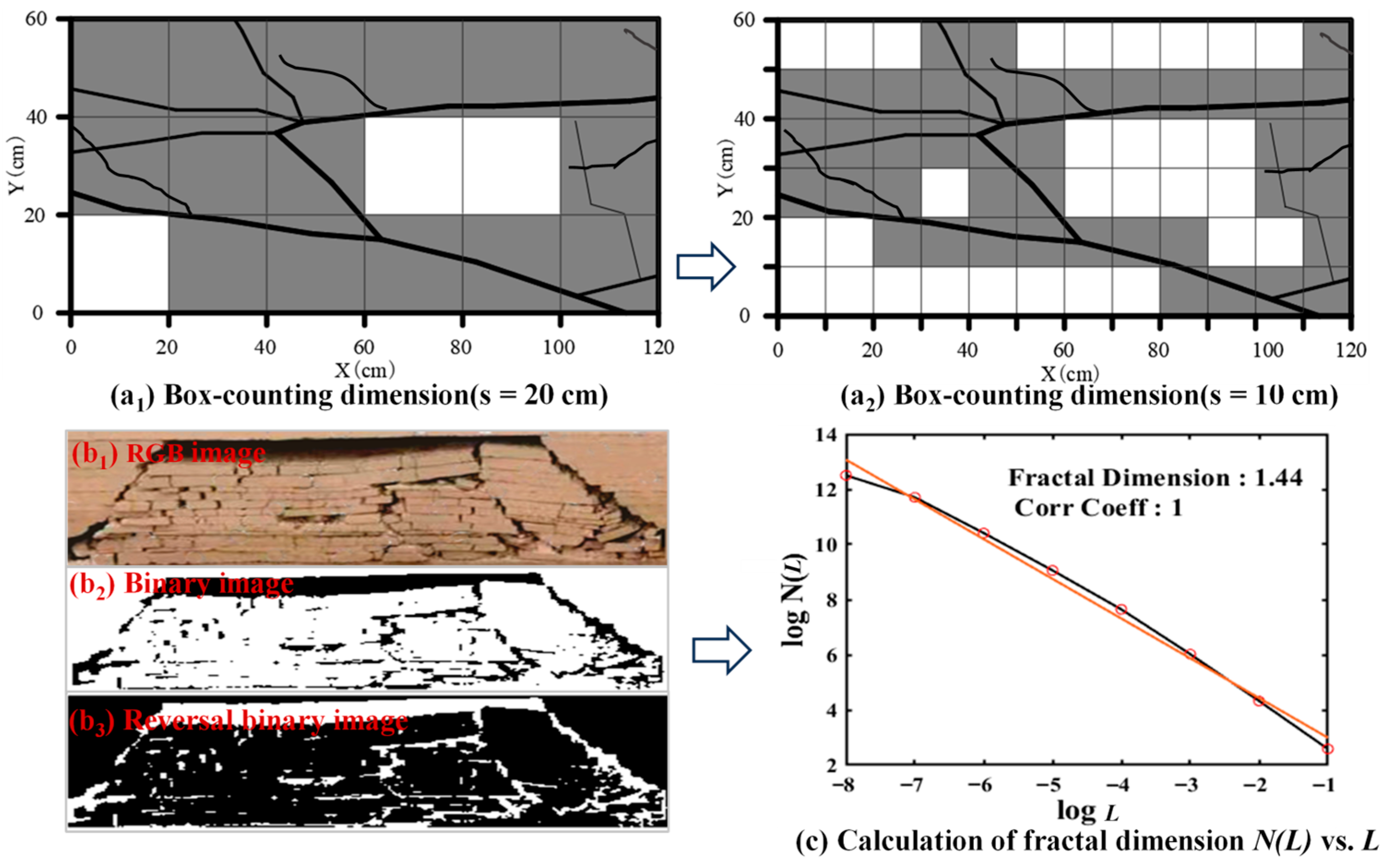

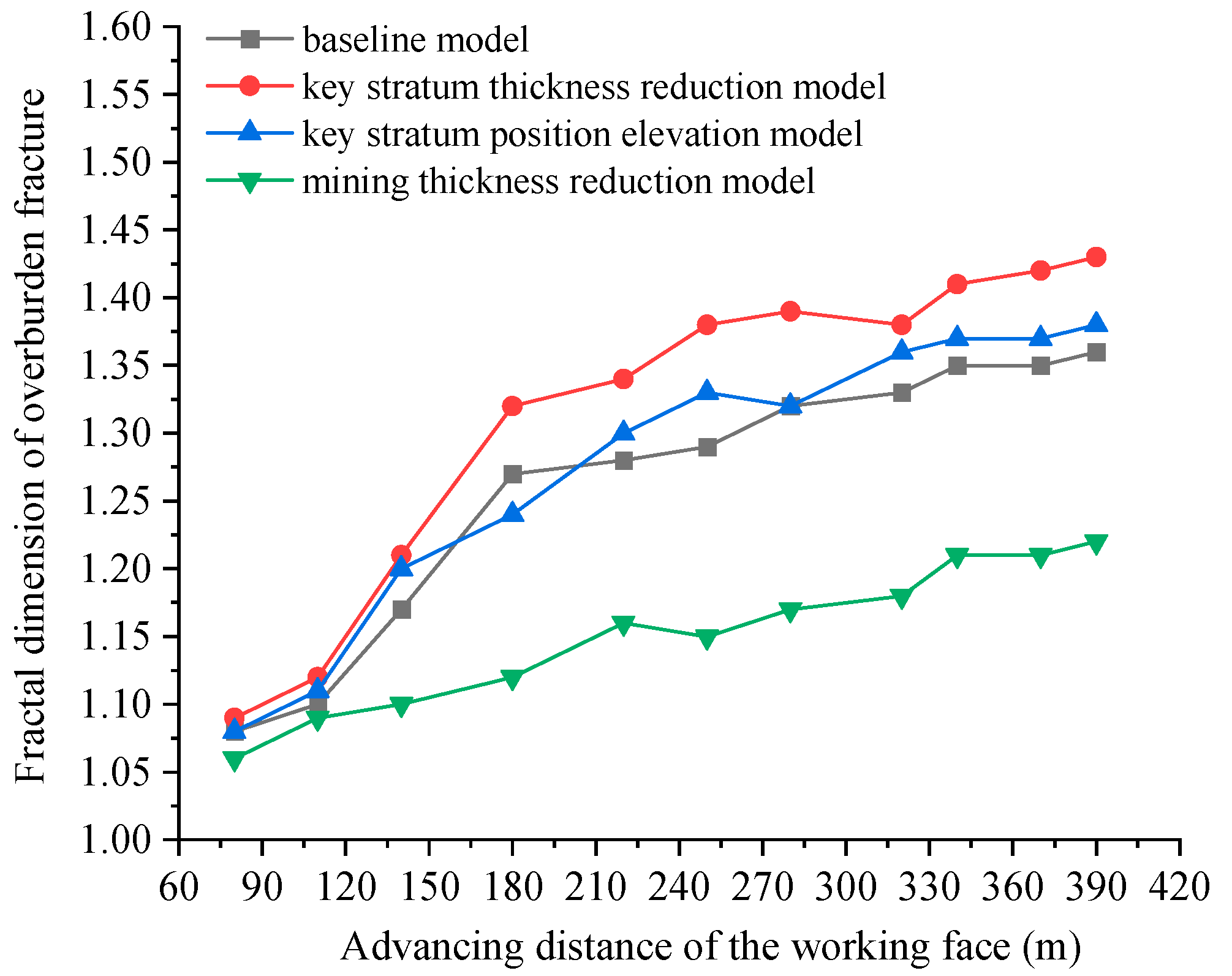

4.1. Quantification of Overburden Damage Based on Fractal Dimension of Fracture Network

4.2. Effect of Key Stratum Thickness

4.3. Effect of Key Stratum Location Conditions

4.4. Effect of Mining Thickness Conditions

4.5. Ratio of Fractured Zone Height to Mining Height

5. Effects of Formation Structure on Overburden Stress and Damage Evolution Based on Scenario Numerical Simulations

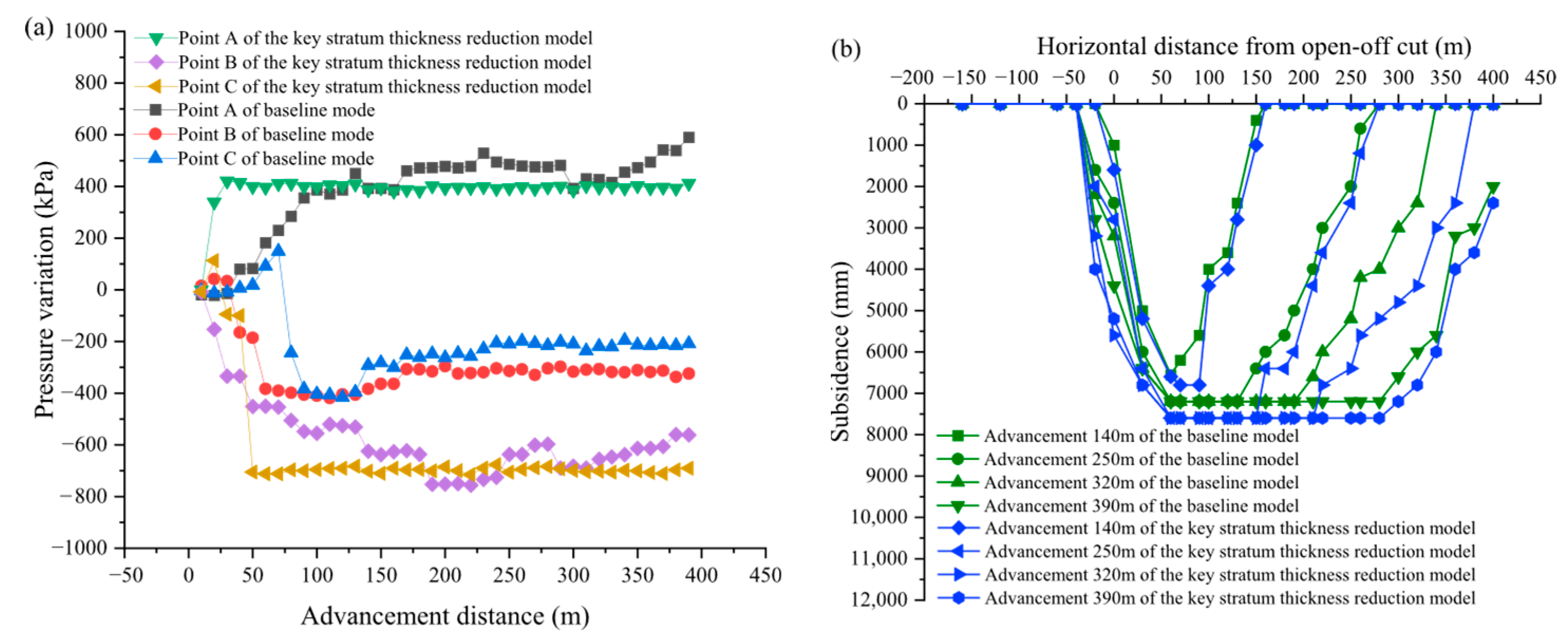

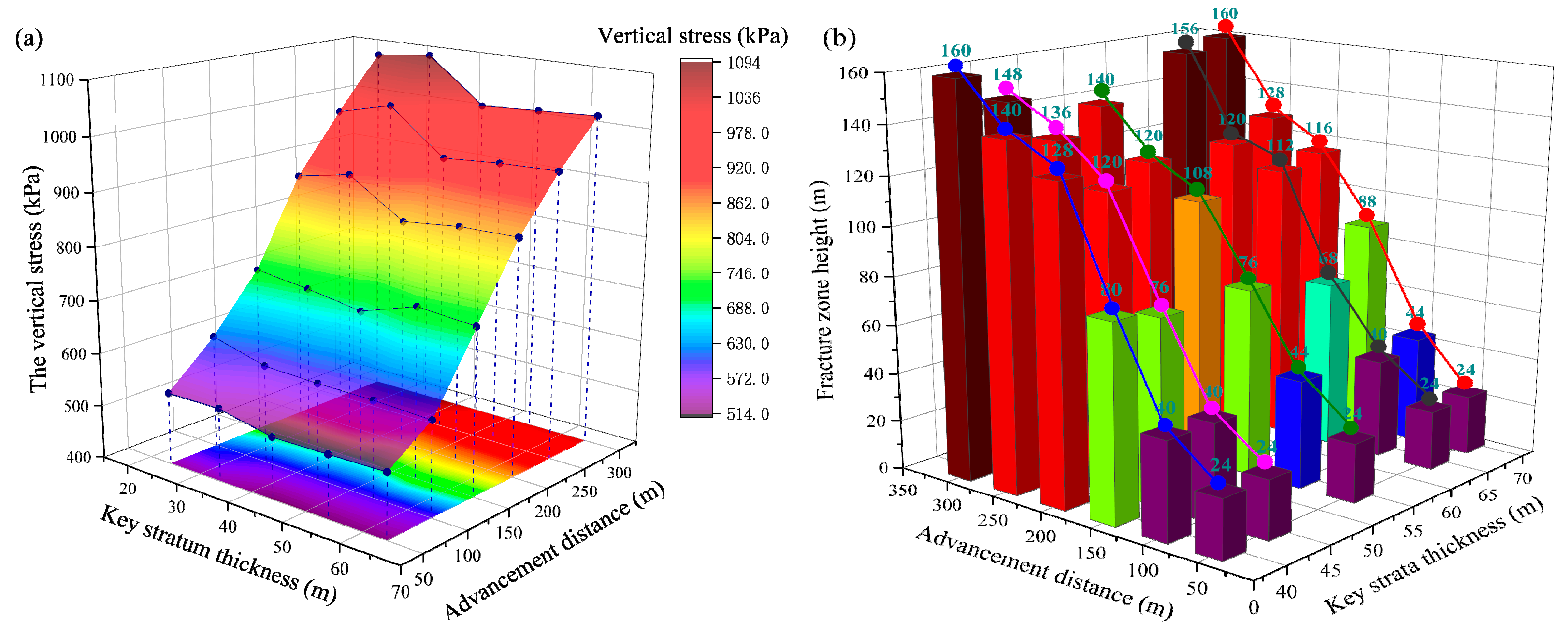

5.1. Effect of Key Stratum Thickness on Overburden Stress and Damage

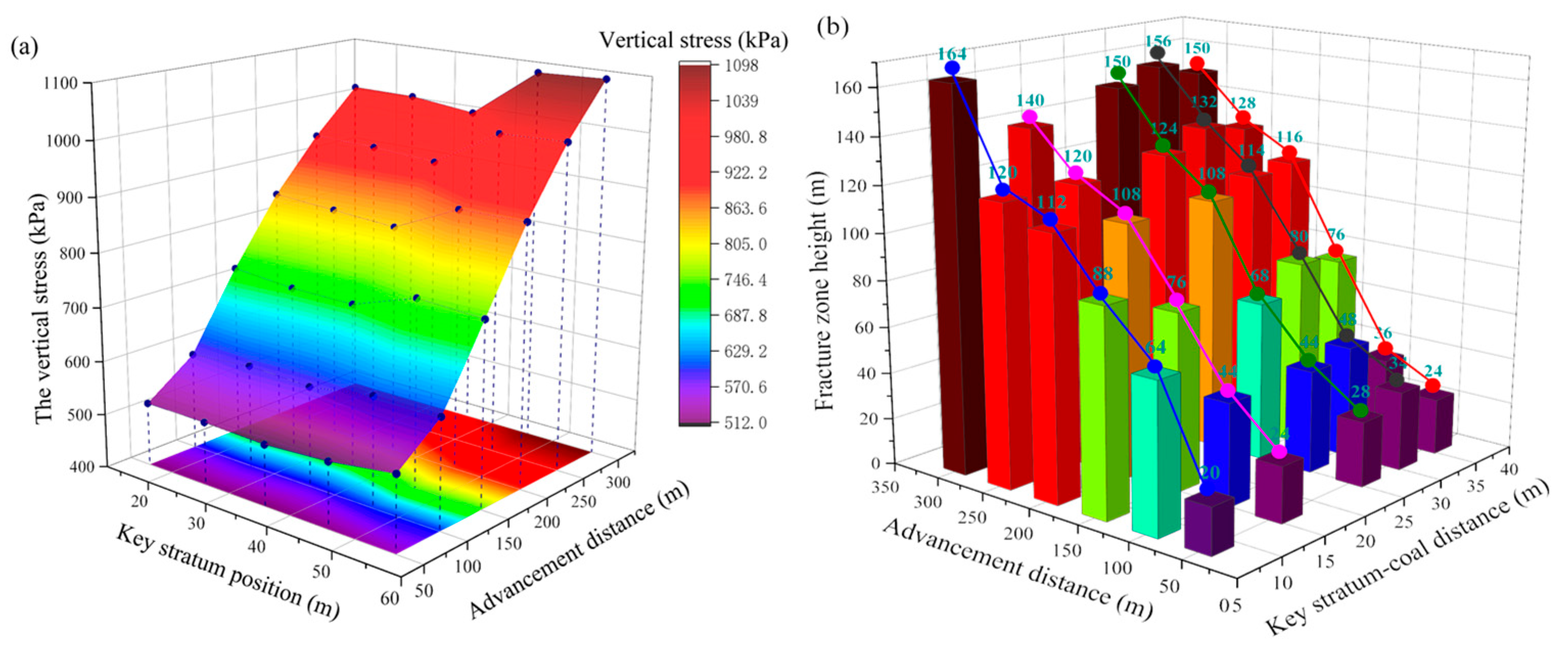

5.2. Effect of Key Stratum Location on Overburden Stress and Damage

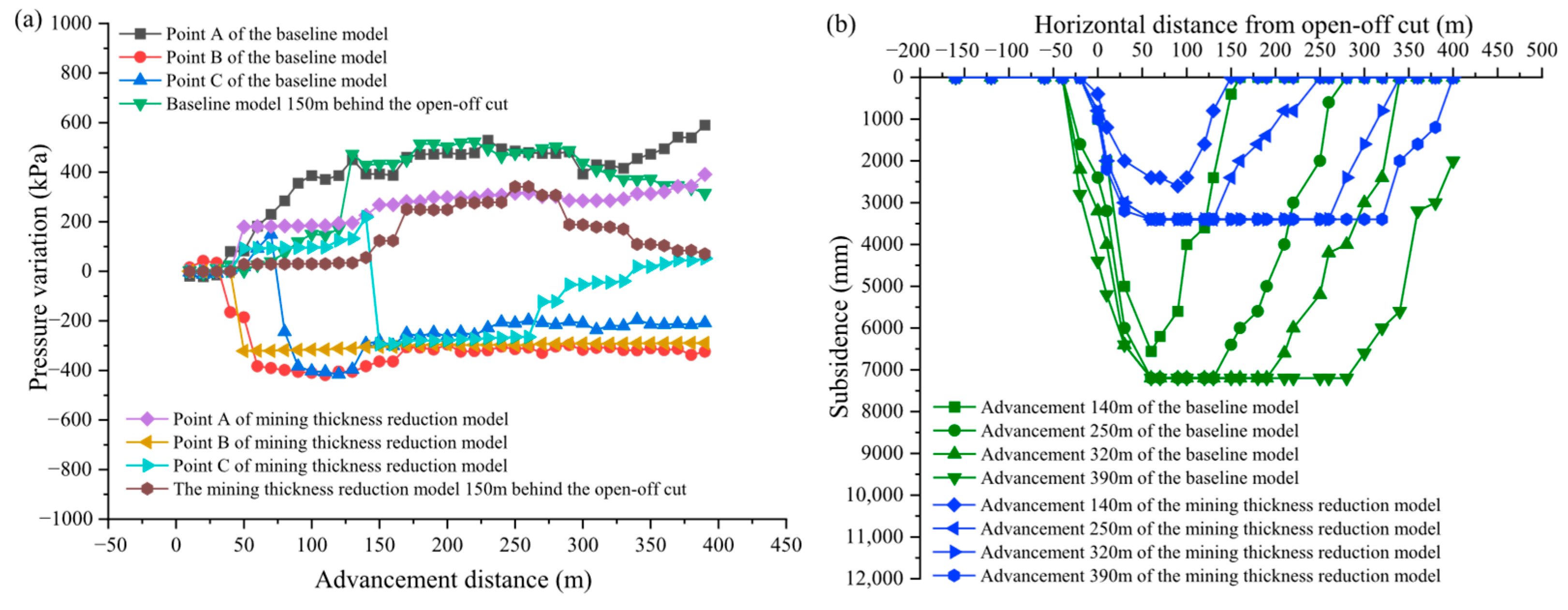

5.3. Effect of Mining Thickness on Overburden Stress and Damage

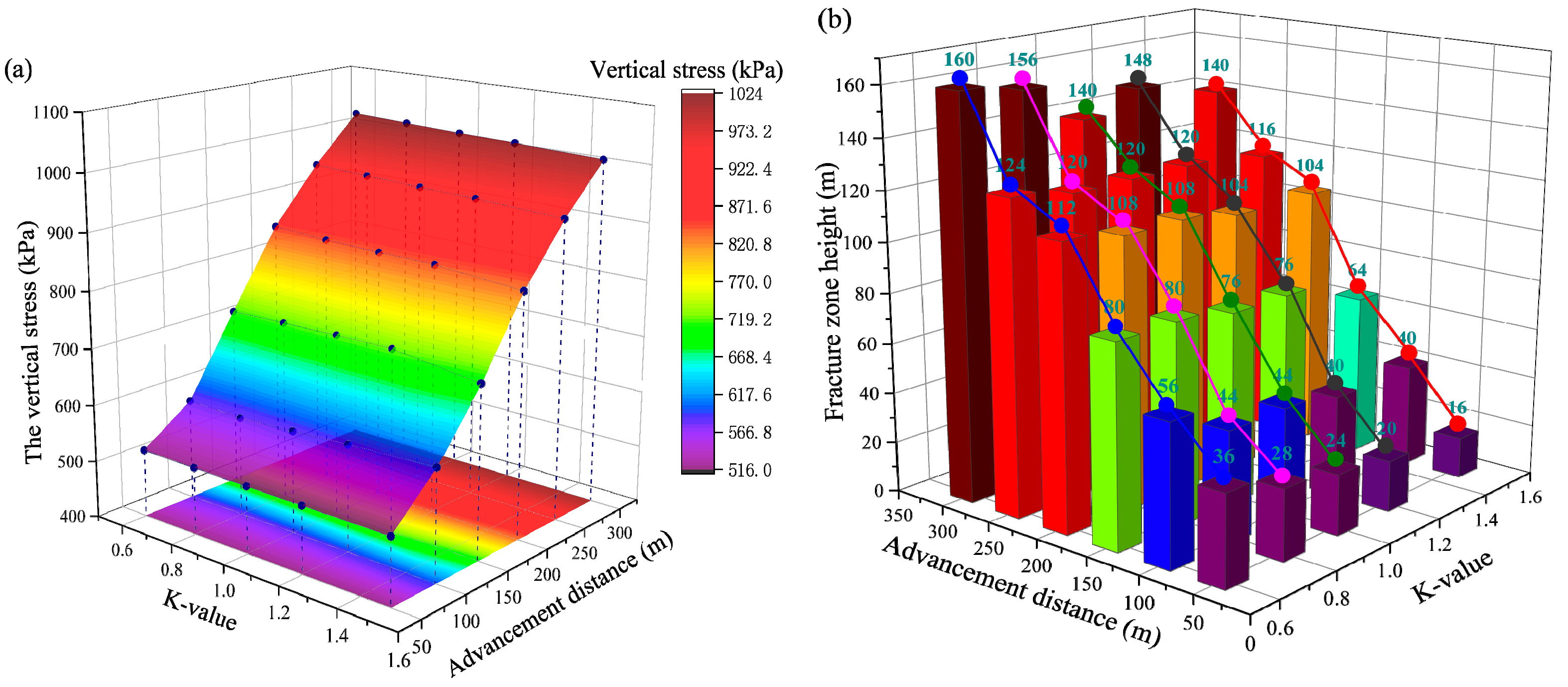

5.4. Effect of Key Stratum Hardness on Overburden Stress and Damage

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- A reduction in the thickness of the key stratum leads to the most severe overburden damage. The key stratum fractures earlier, and the maximum subsidence decreases approximately 16.7%. Following the initiation of fracturing, an increase in key stratum thickness is associated with a reduction in the fracture zone height (by 8.3%) and a decrease in the volume of the plastic zone.

- (2)

- When the key stratum is positioned higher, the subsidence and its extent at 40 m above the coal seam increase, while they decrease at 100 m and 160 m above the coal seam, leading to a delay in key stratum fracturing. The height of the fracture zone initially decreases and then increases. As the working face advanced, the plastic zone volume initially increased, then decreased, and subsequently increased again.

- (3)

- A decrease in mining thickness induces amplified subsidence responses (about 20% increase) accompanied by enhanced fracture zone vertical propagation. The subsidence at 100 m and 160 m above the coal seam decreases, while it increases at 40 m above the coal seam. Additionally, the height of the fracture zone and the volume of the plastic zone increase with increasing mining thickness.

- (4)

- As the hardness of the key stratum increases, the fracturing of the key stratum is delayed. Correspondingly, both the height of the fracture zone and the volume of the plastic zone decreased with increasing key stratum hardness.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fan, J.S.; Yuan, Q.; Chen, J.; Ren, Y.W.; Zhang, D.D.; Yao, H.; Hu, B.; Qu, Y.H. Investigation of surrounding rock stability during proximal coal seams mining process and feasibility of ground control technology. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2024, 186, 1447–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghose, A.K. Underground methods of extraction of thick coal seams-a global survey. Min. Sci. Technol. 1984, 2, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.; Tang, Y.; Huang, W.; Hou, K.; Luo, Y.; Liu, J. Research on the height of the water-conducting fracture zone in fully mechanized top coal caving face under combined-strata structure. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.H.; Hou, B.; Xia, Y.; Chen, M.; Tan, P.; Luo, R.K. Experimental research on hydraulic fracture propagation in integrated fracturing for layered formation with multi-lithology combination. J. China Coal Soc. 2021, 46, 377–384. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, P.L.; Jin, Z.M. Mechanical model study on roof control for fully mechanized coal face with large mining height. Chin. J. Rock. Mech. Eng. 2008, 27, 193–198. [Google Scholar]

- Gandhe, A.; Venkateswarlu, V.; Gupta, R.N. Extraction of coal under a surface water body-a strata control investigation. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2005, 38, 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.P.; Bian, K.; Cheng, J.L.; Qi, Y.M. Study of water-flow fractue-zone height based on the critical value of rock angular displacement. J. China Univ. Min. Technol. 2011, 40, 536–539. [Google Scholar]

- Peta, K.; Stemp, W.J.; Stocking, T.; Chen, R.; Love, G.; Gleason, M.A.; Houk, B.A.; Brown, C.A. Multiscale geometric characterization and discrimination of dermatoglyphs (fingerprints) on hardened clay—A novel archaeological application of the gelSight max. Materials 2025, 18, 2939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Jiang, C.B.; Jin, Z.; Wang, W.S.; Zhuang, W.J.; Yu, H. Three-dimensional physical model experiment of mining-induced deformation and failure characteristics of roof and floor in deep underground coal seams. Process Saf. Environ. Protect. 2021, 150, 400–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, F.Z.; Ma, K.; Tang, C.A.; Wang, S.J.; Guo, H.Y. Movement of overburden with different mining thickness and response characteristics of surrounding rock under multi-key layer structure. Coal Sci. Technol. 2022, 50, 211–218. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, Z.J.; Feng, X. Research on the influence of lithological combination characteristics on the height of water conducting fracture zones. Energy Technol. Manag. 2019, 44, 86–88. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, B.; Zuo, Y.J.; Lin, J.Y.; Sun, W.B.; Chen, B. Study on the activation characteristics of reverse faults by the combination structure of roof lithology. China Min. Mag. 2021, 30, 172–180. [Google Scholar]

- Arka, J.D.; Prabhat, K.M.; Nilabjendu, G.; Awanindra, P.S.; Ranjan, K.; Subhashish, T.; Rana, B. Evaluation of energy accumulation, strain burst potential and stability of rock mass during underground extraction of a highly stressed coal seam under massive strata-a field study. Eng. Geol. 2023, 322, 107178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.Y.; Zuo, Y.J.; Wang, H.; Yu, M.L.; Shui, Y.; Dai, Y.J.; Liu, R.B. Research on roof mining effect under different lithological combinations. J. Guizhou Univ. Nat. Sci. 2019, 36, 44–49. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, S.Y.; Cao, D.T.; Zhou, H.Y.; Yang, C.W.; Liu, J.G. Restrictive function of lithology and its composite structure on deformation and failure depth of mining coal seam floor. J. Min. Saf. Eng. 2014, 31, 90–96. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, R.; Mandal, P.K.; Singh, A.K.; Kumar, R.; Maiti, J.; Ghosh, A.K. Upshot of strata movement during underground mining of a thick coal seam below hilly terrain. Int. J. Rock. Mech. Min. Sci. 2008, 45, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.S.; Gao, Y.F.; Sun, Z.J.; Liu, S.Y. Analysis of spatial effect and layer effect in numerical calculation of mining subsidence. Rock. Soil. Mech. 2004, 25, 940–942. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Wang, J.P.; Chen, Y.D.; Lei, M.X.; Yang, D.P.; Yang, K.P.; Yuan, Y.H. Study on effect of interburden on movement of overburden in multiple coal seams. Coal Sci. Technol. 2020, 48, 246–255. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.M.; Liu, C.Y.; Huang, B.X.; Yang, J.X. Mining height effect of overlying strata breakage and water flowing fracture evolution in steep seam. J. Hunan Univ. Sci. Technol. Nat. Sci. Ed. 2012, 27, 10–15. [Google Scholar]

- He, C.C.; Xu, J.L.; Wang, F.; Wang, F. Movement boundary shape of overburden strata and its influencing factors. Energies 2018, 11, 742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.C.; Li, X.L.; Qin, Q.Z.; Wang, Y.B.; Gao, X. Study on overlying strata movement patterns and mechanisms in super-large mining height stopes. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2023, 82, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.L.; Guo, J.P.; Lu, X.W.; Ding, K.P.; Yuan, R.F.; Wang, D.C. Simulation and on-site detection of the failure characteristics of overlying strata under the mining disturbance of coal seams with thin bedrock and thick alluvium. Sensors 2024, 24, 1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakhno, I.; Zuievska, N.; Xiao, L.; Zuievskyi, Y.; Sakhno, S.; Semchuk, R. Prediction of water inrush hazard in fully mechanized coal seams’ mining under aquifers by numerical simulation in ANSYS software. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 4302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.; Zhang, X.; Ke, F.; Liu, J.; Yao, Q.; Luo, H.; Li, X.; Xu, Y. Evolution of overlying strata bed separation and water inrush hazard assessment in fully mechanized longwall top-coal caving of an ultra-thick coal seam. Water 2025, 17, 850. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.G.; Qin, X.F.; Liu, S.T.; Su, H.J.; Yang, Z.B.; Zhang, G.C. Study on overburden fracture and structural distribution evolution characteristics of coal seam mining in deep large mining height working face. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, T.; Li, Z.L.; Liu, K.; Zhu, Y.Z.; Jia, W.J. Overburden failure and fracture propagation behavior under repeated mining. Min. Metall. Explor. 2025, 42, 219–234. [Google Scholar]

| Test | Key Stratum Thickness (cm) | Key Stratum Location | Mining Thickness (cm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 27 | 8 cm from coal seam | 4 |

| 2 | 16 | 8 cm from coal seam | 4 |

| 3 | 27 | 29 cm from coal seam | 4 |

| 4 | 27 | 8 cm from coal seam | 2 |

| Layer No. | Lithology | Layer Thickness (m) | Bulk Modulus (GPa) | Shear Modulus (GPa) | Cohesion C (MPa) | Internal Friction Angle φ (°) | Matching Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1/5/9/12 | Fine sandstone | 12/14/16/12 | 2.8 | 5.79 | 7.3 | 21 | 664 |

| 2/7/11 | Sandy mudstone | 14/12/6 | 1.64 | 3.28 | 5.5 | 21 | 964 |

| 3/8/13/15 | Siltstone | 8/54/20/20 | 2.8 | 8.7 | 6 | 22 | 674 |

| 4/6 | Coarse sandstone | 18/16 | 4 | 8.1 | 4.6 | 33 | 764 |

| 10/14 | Coal | 8/6 | 2.8 | 5.79 | 7.3 | 21 | 664 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Teng, T.; Xu, Z.; Wang, Y. Overburden Damage in High-Intensity Mining: Effects of Lithology and Formation Structure. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 10518. https://doi.org/10.3390/app151910518

Teng T, Xu Z, Wang Y. Overburden Damage in High-Intensity Mining: Effects of Lithology and Formation Structure. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(19):10518. https://doi.org/10.3390/app151910518

Chicago/Turabian StyleTeng, Teng, Zhuhe Xu, and Yuxuan Wang. 2025. "Overburden Damage in High-Intensity Mining: Effects of Lithology and Formation Structure" Applied Sciences 15, no. 19: 10518. https://doi.org/10.3390/app151910518

APA StyleTeng, T., Xu, Z., & Wang, Y. (2025). Overburden Damage in High-Intensity Mining: Effects of Lithology and Formation Structure. Applied Sciences, 15(19), 10518. https://doi.org/10.3390/app151910518