RecGen: No-Coding Shell of Rule-Based Expert System with Digital Twin and Capability-Driven Approach Elements for Building Recommendation Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

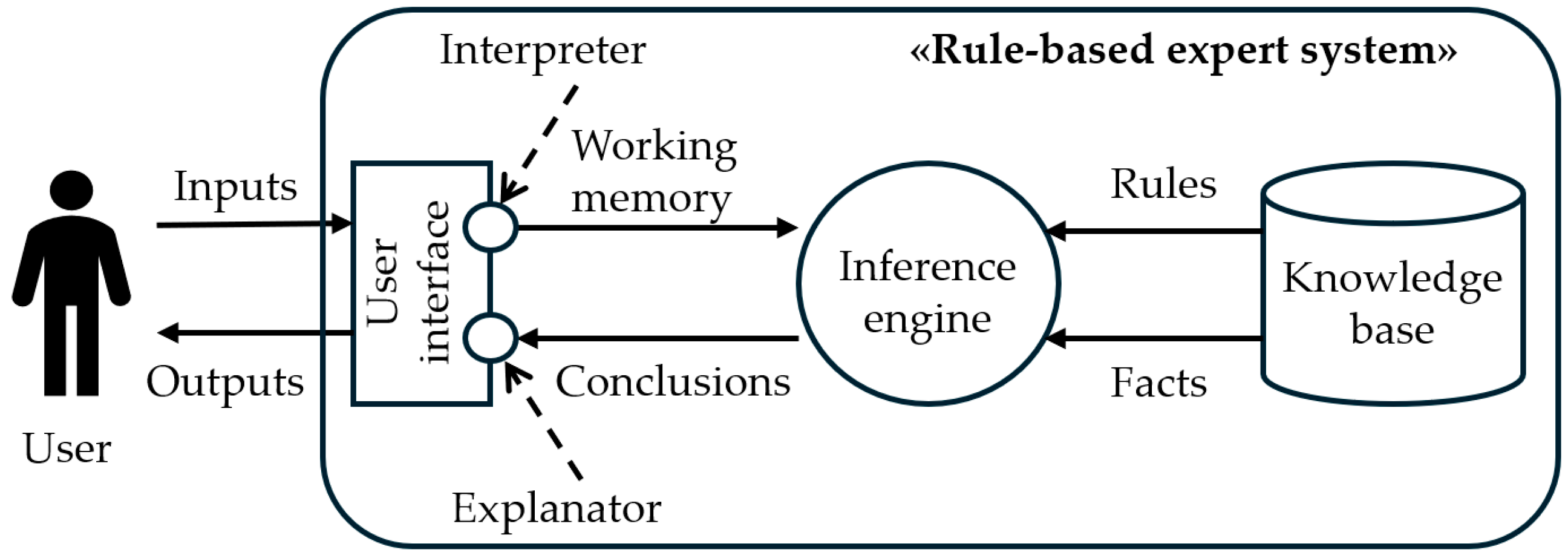

2.1. Traditional Architecture of Rule-Based Expert System

- A knowledge base—a database of expert knowledge, which is described by facts and rules. The rules are conditional statements to trigger conclusions.

- An inference engine—an artificial intelligence, which mimics an expert decision-making using rules predefined in the knowledge base. The inference engine analyzes a working memory, which describes a problem or a situation explained by a user.

- A user interface—an input–output terminal for the users of an expert system, which includes an interpreter to transform a user input to a format compatible with an inference engine and an explanator to translate an output of an expert system to a readable form for a user.

2.2. Rule-Based Expert System with Digital Twin Elements for Building Recommendation Systems

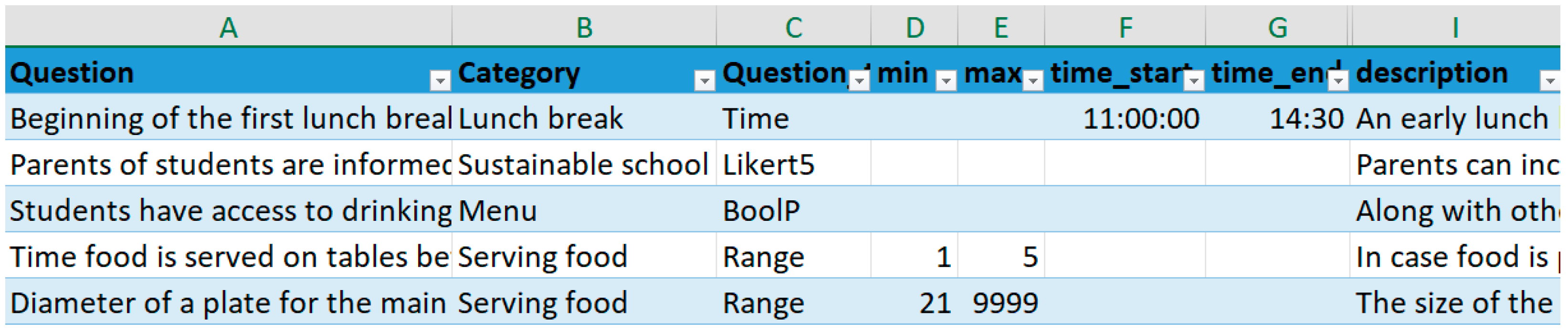

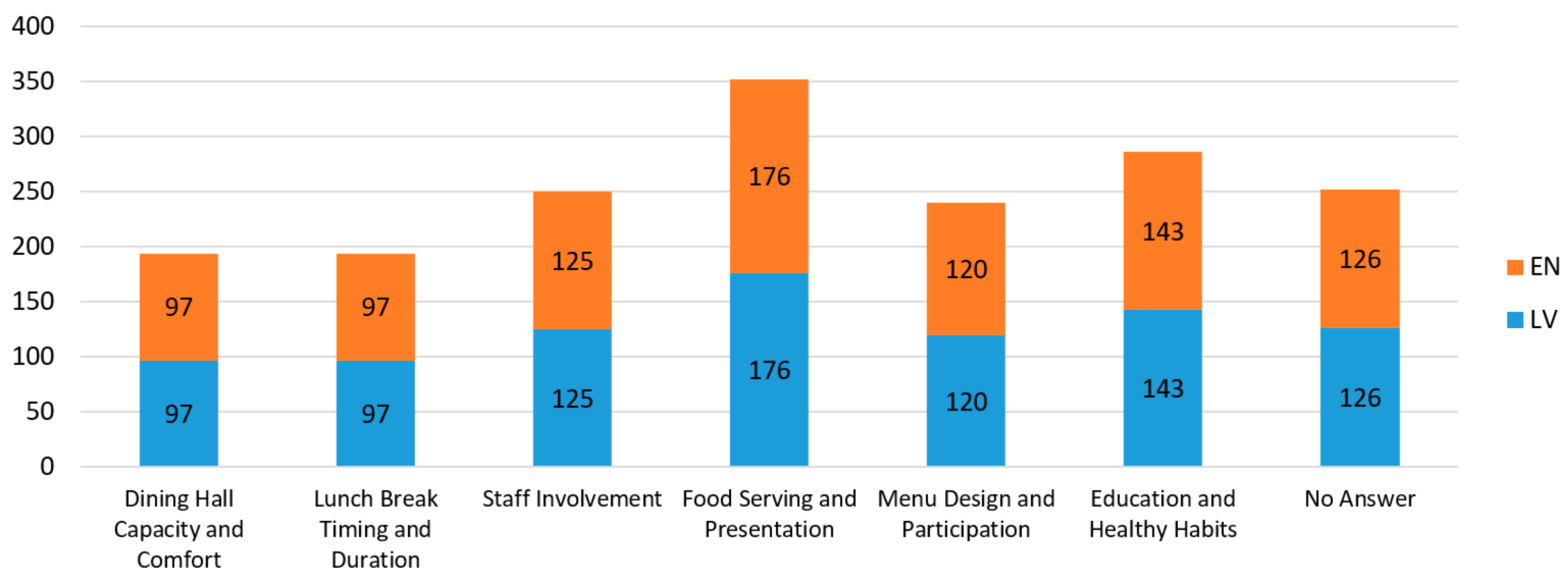

2.3. Validation Use-Case of RecGen Shell: Reduction in Plate Waste in Latvian Schools

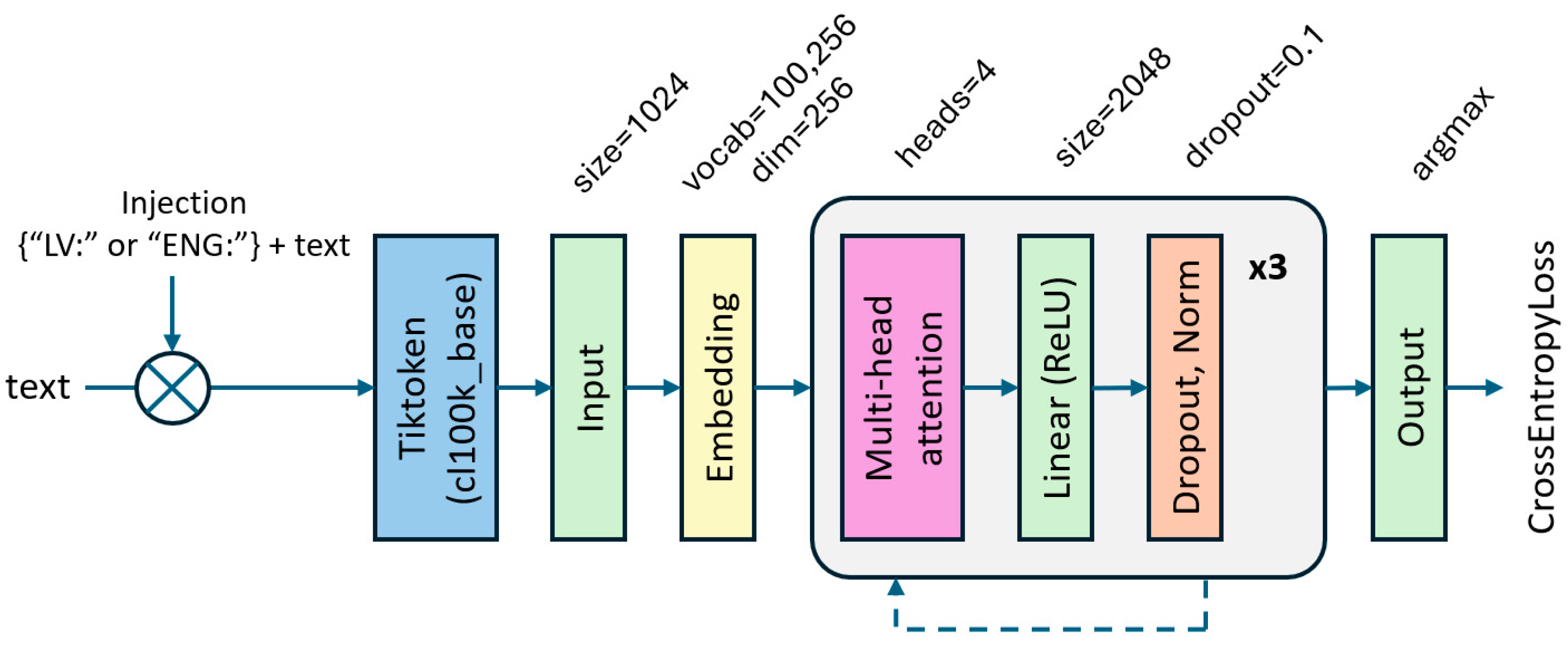

2.4. LLM Support to Filter Measurable Properties and Recommendations

3. Results

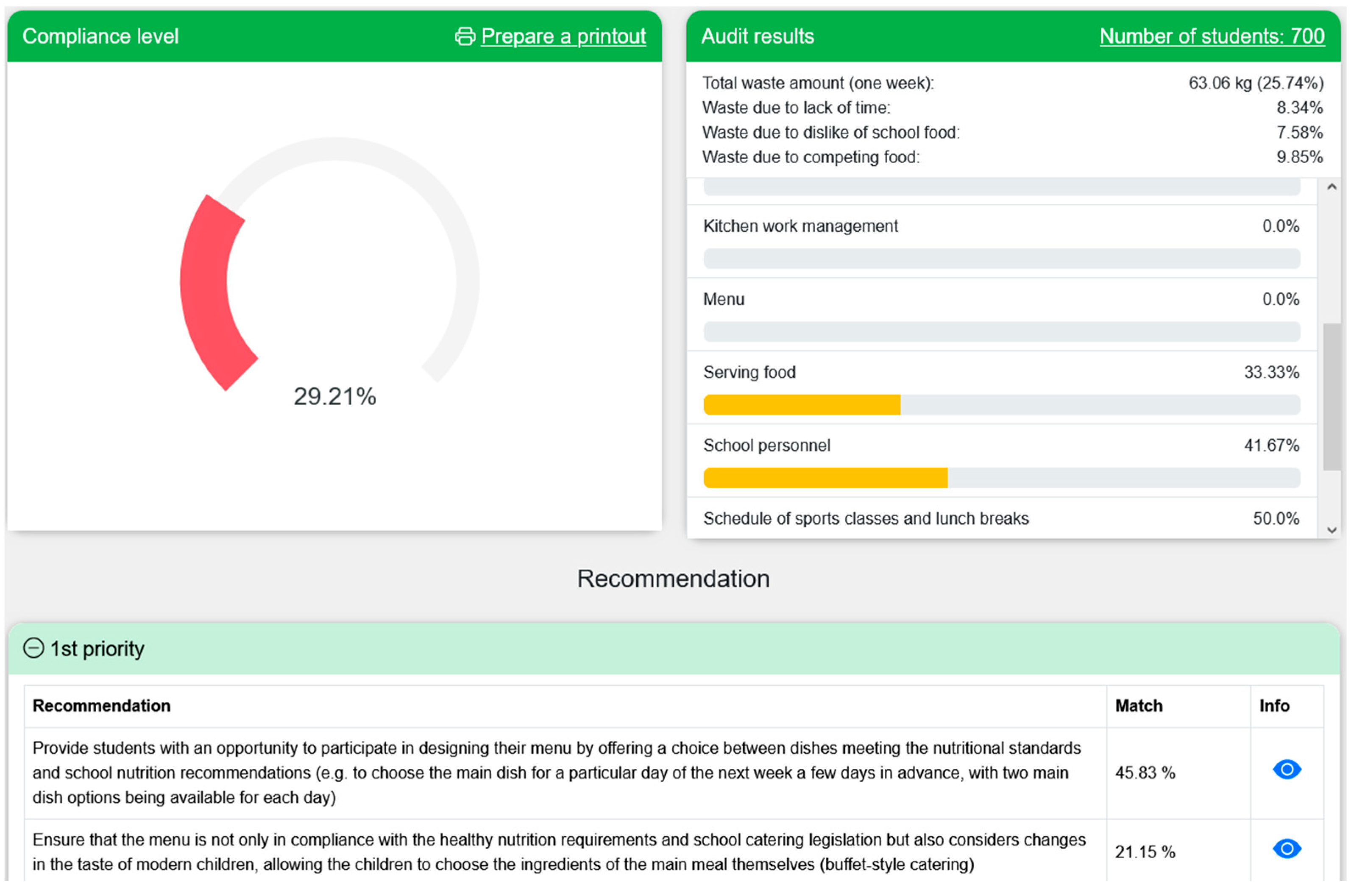

3.1. Expert System for Plate Waste Reduction

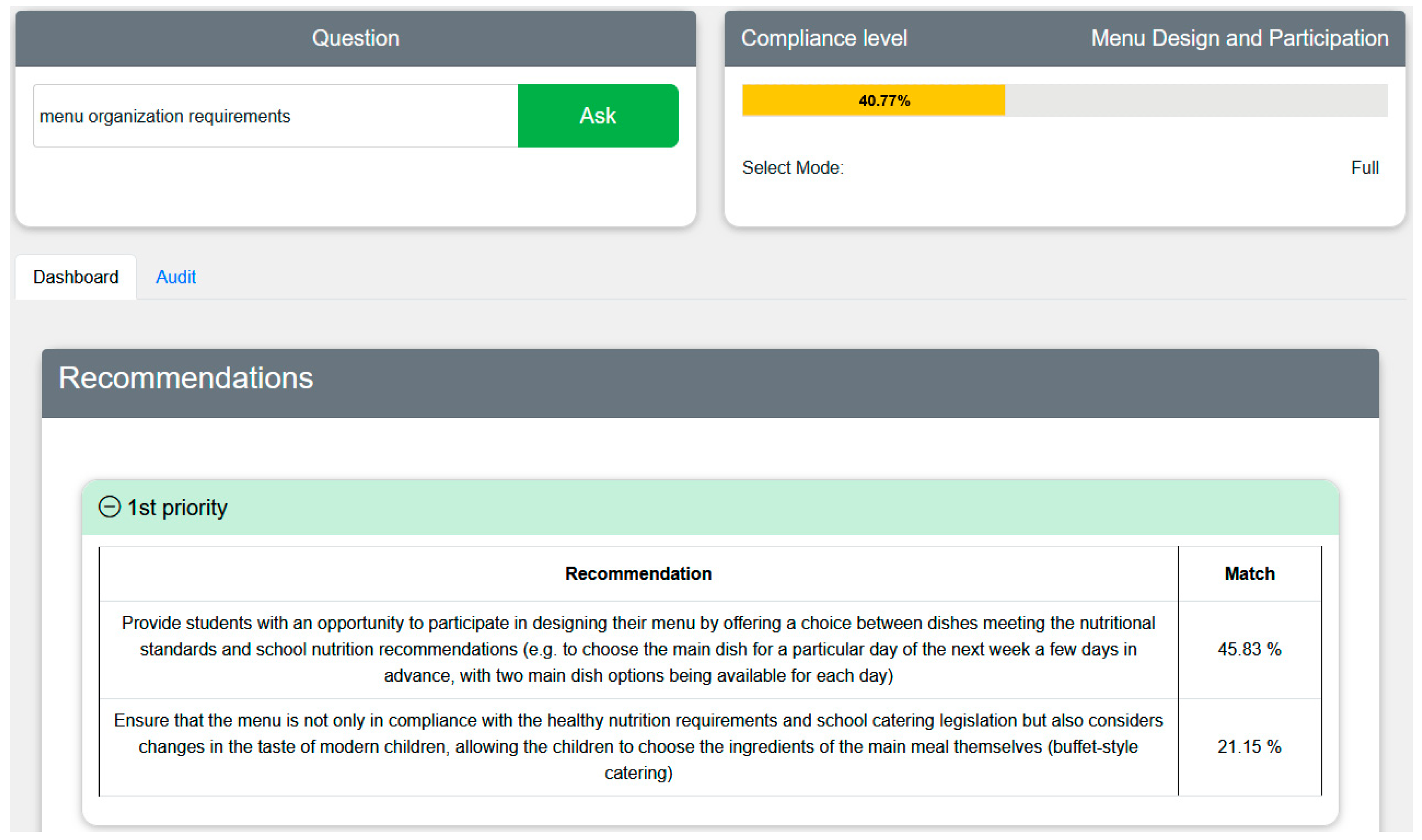

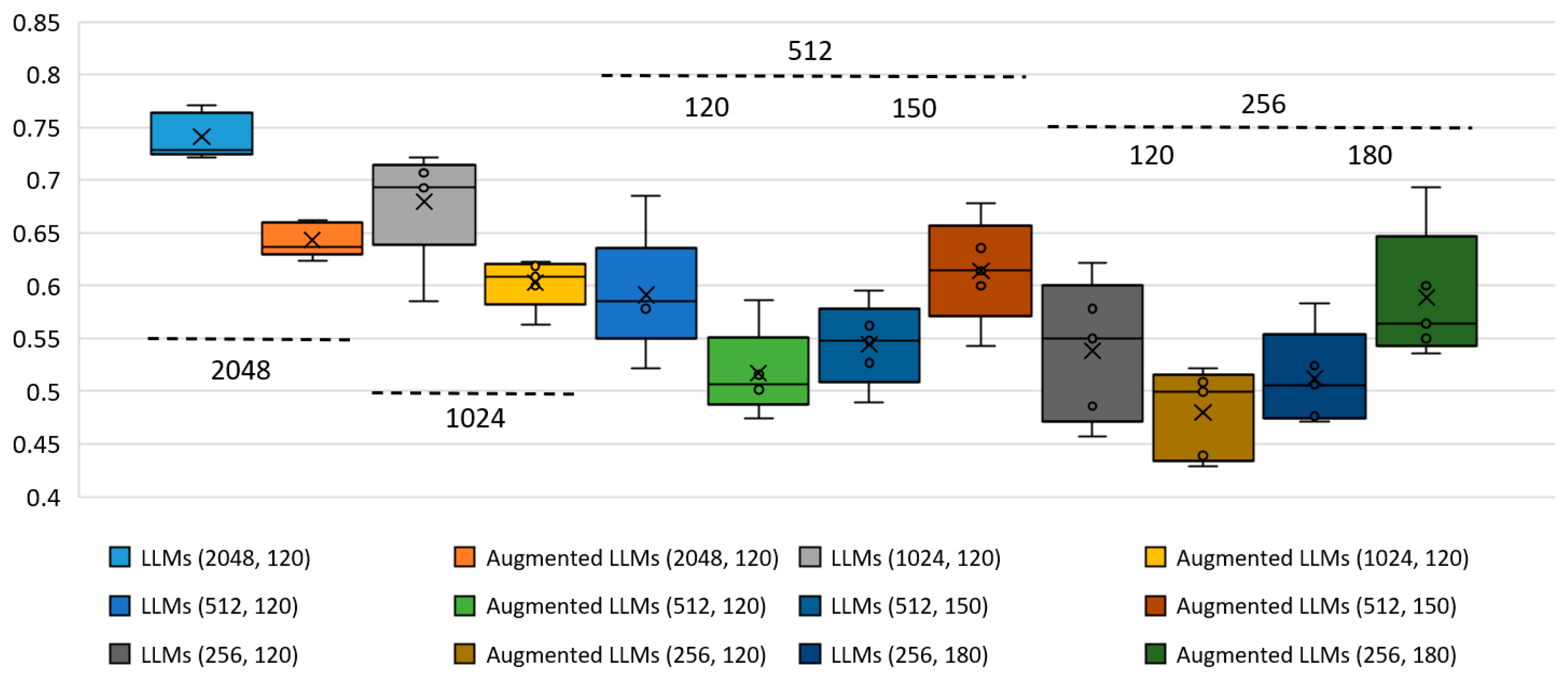

3.2. LLM Filter to Enhance User Experience

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Category | Examples of Questions (ENG) |

|---|---|

| Dining Hall Capacity and Comfort | 1. Dining table space per student, cm; 2. Do students eat less if the dining hall is too noisy or crowded? |

| Lunch Break Timing and Duration | 1. Duration of the lunch break; 2. What is the minimum duration required for a lunch break in schools? |

| Staff Involvement and Communication | 1. Motivate students to eat at lunch; 2. What strategies do schools use to involve staff in reducing food waste? |

| Food Serving and Presentation | 1. Average temperature of the soup served; 2. What’s the ideal plate size for a visually appealing dinner presentation? |

| Menu Design and Participation | 1. Catering system in the form of a buffet; 2. How does student feedback influence the school menu? |

| Education and Healthy Habits | 1. Students’ awareness of healthy nutrition is sufficient; 2. How can schools help students learn the importance of not wasting food? |

| No Answer | 1. Feed stray cats with leftovers from the plate; 2. Reading a book during lunch? |

| Category | Examples of Recommendations (ENG) |

|---|---|

| Dining Hall Capacity and Comfort | 1. Ensure the permissible number of students in the dining hall; 2. Provide enough table space per student in the dining hall. |

| Lunch Break Timing and Duration | 1. Ensure that the lunch break begins no earlier than 10:30; 2. For students to finish their meal without rushing, no sports class must be before/after the lunch break. |

| Staff Involvement and Communication | 1. Involve a school personnel member (teacher or canteen employee) during the lunch break, thereby motivating students to eat or taste the food, explaining matters related to the food served and helping the students to replenish their lunch plates; 2. Improve communication and the information flow between school personnel and canteen personnel by introducing a digital system or tool that provides timely and accurate information on the number of students per meal. |

| Food Serving and Presentation | 1. Ensure that the temperature of the dishes served meets the requirements; 2. Serve the dishes upon the arrival of students at the canteen. |

| Menu Design and Participation | 1. Design a school menu in a creative way (e.g., involve students in coming up with funny or attention-grabbing names for “complex” dishes); 2. Provide an opportunity for student parents/guardians to familiarize themselves with the recipes of the dishes served at schools, thus encouraging the preparation of the same dishes in the families and the acceptance and recognition of the dishes by the students at the school. |

| Education and Healthy Habits | 1. Students need to be educated about a zero-waste lifestyle, thereby increasing their awareness of the ecological role of food waste and the negative environmental impact; 2. Design a training plan for school kitchen personnel to acquire, improve, or expand their skills and knowledge necessary for this profession (position). |

| No Answer | There are no recommendations that match your question. |

| Solution | Min | Mean | Median | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LLMs without injection (6 categories) | 0.725 | 0.753 | 0.766 | 0.767 |

| Augmented LLMs without injection (6 categories) | 0.629 | 0.647 | 0.642 | 0.670 |

| LLM with injection (6 categories) | 0.720 | 0.766 | 0.760 | 0.820 |

| Augmented LLM with injection (6 categories) | 0.635 | 0.652 | 0.645 | 0.677 |

| LLM with injection (7 categories) | 0.721 | 0.741 | 0.729 | 0.771 |

| Augmented LLM with injection (7 categories) | 0.624 | 0.643 | 0.636 | 0.662 |

References

- Ioshchikhes, B.; Frank, M.; Weigold, M. A Systematic Review of Expert Systems for Improving Energy Efficiency in the Manufacturing Industry. Energies 2024, 17, 4780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhu, C. Industrial Expert Systems Review: A Comprehensive Analysis of Typical Applications. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 88558–88584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes-Roth, F. Rule-Based Systems. Commun. ACM 1985, 28, 921–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, A. Rule-Based Expert Systems. In Handbook of Measuring System Design; Sydenham, P.H., Thorn, R., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2005; ISBN 0-470-02143-8. [Google Scholar]

- Colmerauer, A.; Roussel, P. The Birth of Prolog. In History of Programming Languages—II; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 1996; pp. 331–367. ISBN 0-201-89502-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudgick, J.A.T. A Comparative Study of Four Major Knowledge Representation Techniques Used in Expert Systems with an Implementation Prolog. Master’s Thesis, Rochester Institute of Technology, Rochester, NY, USA, 1987. Available online: https://repository.rit.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1581&context=theses (accessed on 27 August 2025).

- Merritt, D. Using Prolog’s Inference Engine. In Springer Compass International; Springer: New York, USA, 1989; pp. 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratko, I. Prolog Programming for Artificial Intelligence; International Computer Science Series; Addison-Wesley Publishing Company: Wokingham, UK, 1986; ISBN 0-20R-14224-4. [Google Scholar]

- Kahtan, H.; Zamli, K.Z.; Wan Ahmad Fatthi, W.N.A.; Abdullah, A.; Abdulleteef, M.; Kamarulzaman, N.S. Heart Disease Diagnosis System Using Fuzzy Logic. In Proceedings of the 2018 7th International Conference on Software and Computer Applications (ICSCA ’18), Kuantan, Malaysia, 8–10 February 2018; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 297–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantahun, Z. Application of Data Mining with Knowledge Based System for Diagnosis and Treatment of Cattle Diseases: The Case of International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) Animal Health Center Addis Ababa. Available online: http://repository.smuc.edu.et/handle/123456789/6429 (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- Barbedo, J.G.A. Expert Systems Applied to Plant Disease Diagnosis: Survey and Critical View. IEEE Lat. Am. Trans. 2016, 14, 1910–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikhkhoshkar, M.; El-Haouzi, H.B.; Aubry, A.; Hamzeh, F.; Rahimian, F. A Data-Driven and Knowledge-Based Decision Support System for Optimized Construction Planning and Control. Autom. Constr. 2025, 173, 106066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palazzo, L.; Dolcini, G.; Claudi, A.; Biancucci, G.; Sernani, P.; Ippoliti, L.; Salladini, L.; Dragoni, A.F. Spyke3D: A New Computer Games Oriented BDI Agent Framework. In Proceedings of the CGAMES’2013 USA, Louisville, KY, USA, 30 July–1 August 2013; pp. 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghany, H.A.; Sabry, I.; El-Assal, A. Applications and Analysis of Expert Systems: Literature Review. Benha J. Appl. Sci. 2023, 8, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovas, K.; Hatzilygeroudis, I. ACRES: A Framework for (Semi)Automatic Generation of Rule-based Expert Systems with Uncertainty from Datasets. Expert Syst. 2024, 41, e13723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stirna, J.; Grabis, J.; Henkel, M.; Zdravkovic, J. Capability Driven Development—An Approach to Support Evolving Organizations. In Lecture Notes in Business Information Processing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adib, M.; Zhang, X.Z. The Risk-Based Management Control System: A Stakeholders’ Perspective to Design Management Control Systems. Int. J. Manag. Enterp. Dev. 2019, 18, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdouw, C.; Tekinerdogan, B.; Beulens, A.; Wolfert, S. Digital Twins in Smart Farming. Agric. Syst. 2021, 189, 103046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flpp GitHub—Flpp20191/RecGen. Available online: https://github.com/flpp20191/RecGen (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Kodors, S.; Zvaigzne, A.; Litavniece, L.; Lonska, J.; Silicka, I.; Kotane, I.; Deksne, J. Plate Waste Forecasting Using the Monte Carlo Method for Effective Decision Making in Latvian Schools. Nutrients 2022, 14, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, H.; Liu, Z.; Qiu, C.; Huang, Y.; Tan, J. Prescriptive Maintenance for Complex Products with Digital Twin Considering Production Planning and Resource Constraints. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2023, 34, 125903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caron, P.; Daguet, E.; Dury, S. The Global Food System Is Not Broken but Its Resilience Is Threatened. In Resilience and Food Security in a Food Systems Context; Béné, C., Devereux, S., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 53–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dury, S.; Bendjebbar, P.; Hainzelin, E.; Giordano, T.; Bricas, N. (Eds.) Food Systems at Risk: New Trends and Challenges; FAO: Rome, Italy; CIRAD: Montpellier, France; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019; 128p. [CrossRef]

- HLPE. Food Losses and Waste in the Context of Sustainable Food Systems. A Report by the High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition of the Committee on World Food Security and Nutrition; Rome, Italy, 2014; 116p, Available online: https://www.fao.org/cfs/cfs-hlpe/publications/hlpe-8/en (accessed on 9 January 2025).

- LIFE FOSTER Home Page. Available online: https://www.lifefoster.eu/major-challenges-of-the-world-food-system/ (accessed on 9 January 2025).

- FAO. Global Food Losses and Food Waste—Extent, Causes and Prevention; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2011; ISBN 978-92-5-107205-9. [Google Scholar]

- García-Herrero, L.; De Menna, F.; Vittuari, M. Food Waste at School. The Environmental and Cost Impact of a Canteen Meal. Waste Manag. 2019, 100, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasavan, S.; Ali, N.I.B.M.; Ali, S.S.B.S.; Masarudin, N.A.B.; Yusoff, S.B. Quantification of Food Waste in School Canteens: A Mass Flow Analysis. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 164, 105176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wunderlich, S.M.; Martinez, N.M. Conserving Natural Resources through Food Loss Reduction: Production and Consumption Stages of the Food Supply Chain. Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 2018, 6, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahia, E.M.; Mourad, M. Food Waste at the Consumer Level. In Preventing Food Losses and Waste to Achieve Food Security and Sustainability; Burleigh Dodds Science Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2019; ISBN 978-0-429-26662-1. [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat. Food Waste and Food Waste Prevention—Estimates. In Statistics Explained; Eurostat: Luxembourg, 2024; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Food_waste_and_food_waste_prevention_-_estimates (accessed on 19 July 2025).

- Derqui, B.; Fernandez, V.; Fayos, T. Towards More Sustainable Food Systems. Addressing Food Waste at School Canteens. Appetite 2018, 129, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonska, J.; Kodors, S.; Deksne, J.; Litavniece, L.; Zvaigzne, A.; Silicka, I.; Kotane, I. Reducing Plate Waste in Latvian Schools: Evaluating Interventions to Promote Sustainable Food Consumption Practices. Foods 2025, 14, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prescott, M.P.; Burg, X.; Metcalfe, J.J.; Lipka, A.E.; Herritt, C.; Cunningham-Sabo, L. Healthy Planet, Healthy Youth: A Food Systems Education and Promotion Intervention to Improve Adolescent Diet Quality and Reduce Food Waste. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutinen, U.M. Assumptions About Consumers in Food Waste Campaigns: A Visual Analysis. In Food Waste Management: Solving the Wicked Problem; Närvänen, E., Mesiranta, N., Mattila, M., Heikkinen, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 225–256. ISBN 978-3-030-20561-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malefors, C.; Sundin, N.; Tromp, M.; Eriksson, M. Testing Interventions to Reduce Food Waste in School Catering. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 177, 105997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyse, R.; Jackson, J.; Stacey, F.; Delaney, T.; Ivers, A.; Lecathelinais, C.; Sutherland, R. The Effectiveness of Canteen Manager Audit and Feedback Reports and Online Menu-Labels in Encouraging Healthier Food Choices within Students’ Online Lunch Orders: A Pilot Cluster Randomised Controlled Trial in Primary School Canteens in New South Wales, Australia. Appetite 2021, 169, 105856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serebrennikov, D.; Katare, B.; Kirkham, L.; Schmitt, S. Effect of Classroom Intervention on Student Food Selection and Plate Waste: Evidence from a Randomized Control Trial. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0226181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, C.-M.; Chih, C.; Teng, C.-C. Food Waste Management: A Case of Taiwanese High School Food Catering Service. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St Pierre, C.; Sokalsky, A.; Sacheck, J.M. Participant Perspectives on the Impact of a School-Based, Experiential Food Education Program across Childhood, Adolescence, and Young Adulthood. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2024, 56, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elnakib, S.A.; Quick, V.; Mendez, M.; Downs, S.; Wackowski, O.A.; Robson, M.G. Food Waste in Schools: A Pre-/Post-Test Study Design Examining the Impact of a Food Service Training Intervention to Reduce Food Waste. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardner, G.; Burton, W.; Sinclair, M.; Bryant, M. Interventions to Strengthen Environmental Sustainability of School Food Systems: Narrative Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, S.M.; Olds, D.A.; Wolfe, K.L. The Impact of a Portion Plate on Plate Waste in a University Dining Hall. J. Foodserv. Manag. Educ. 2021, 15, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Malefors, C.; Secondi, L.; Marchetti, S.; Eriksson, M. Food Waste Reduction and Economic Savings in Times of Crisis: The Potential of Machine Learning Methods to Plan Guest Attendance in Swedish Public Catering during the Covid-19 Pandemic. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2021, 82, 101041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voysey, I.; Thuruthel, T.G.; Iida, F. Autonomous Dishwasher Loading from Cluttered Trays Using Pre-trained Deep Neural Networks. Eng. Rep. 2020, 3, e12321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malefors, C.; Svensson, E.; Eriksson, M. Automated Quantification Tool to Monitor Plate Waste in School Canteens. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2023, 200, 107288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SzereMeta Spak, M.D.; ColMenero, J.C. University Restaurants Menu Planning Using Mathematical Modelling. J. Food Nutr. Res. 2021, 60, 38–48. [Google Scholar]

- Sigala, E.G.; Gerwin, P.; Chroni, C.; Abeliotis, K.; Strotmann, C.; Lasaridi, K. Reducing Food Waste in the HORECA Sector Using AI-Based Waste-Tracking Devices. Waste Manag. 2025, 198, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Jin, H.; Meng, D.; Wang, J.; Tan, J. A Comprehensive Survey on Process-Oriented Automatic Text Summarization with Exploration of LLM-Based Methods. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2403.02901v2. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Gao, X.; Jia, K.; Pan, J.; Bi, Y.; Dai, Y.; Sun, J.; Wang, M.; Wang, H. Retrieval-Augmented Generation for Large Language Models: A Survey. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2312.10997v5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laudon, K.C.; Laudon, J.P. Management Information Systems: Managing the Digital Firm, 11th ed.; Pearson Education: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010; Chapter 11.4. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, H. How Short or Long Should Be a Questionnaire for Any Research? Researchers’ Dilemma in Deciding the Appropriate Questionnaire Length. Saudi J. Anaesth. 2022, 16, 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, L.; Zheng, Z.; Qiu, Z.; Wang, H.; Gu, H.; Shen, T.; Qin, C.; Zhu, C.; Zhu, H.; Liu, Q.; et al. A Survey on Large Language Models for Recommendation. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.19860v5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Zhang, L.; Gulla, J.A. Pre-train, Prompt and Recommendation: A Comprehensive Survey of Language Modelling Paradigm Adaptations in Recommender Systems. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.03735v3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.-W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1810.04805v2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 30 (NeurIPS 2017); Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 6000–6010. [Google Scholar]

- Kudo, T. Subword Regularization: Improving Neural Network Translation Models with Multiple Subword Candidates. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.10959v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, T.; Schlinger, E.; Garrette, D. How Multilingual Is Multilingual BERT? arXiv 2019, arXiv:1906.01502v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Znotiņš, A.; Barzdiņš, G. LVBERT: Transformer-Based Model for Latvian Language Understanding. In Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence and Applications; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Jiao, X.; Yin, Y.; Shang, L.; Jiang, X.; Chen, X.; Li, L.; Wang, F.; Liu, Q. TinyBERT: Distilling BERT for Natural Language Understanding. arXiv 2020, arXiv:1909.10351v5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinton, G.; Vinyals, O.; Dean, J. Distilling the Knowledge in a Neural Network. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1503.02531v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ester, M.; Kriegel, H.-P.; Sander, J.; Xu, X. A Density-Based Algorithm for Discovering Clusters in Large Spatial Databases with Noise. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (KDD-96), Portland, Oregon, 2–4 August 1996; AAAI Press: Menlo Park, CA, USA, 1996; pp. 226–231. [Google Scholar]

- Allahyari, M.; Pouriyeh, S.; Assefi, M.; Safaei, S.; Trippe, E.D.; Gutierrez, J.B.; Kochut, K. A Brief Survey of Text Mining: Classification, Clustering and Extraction Techniques. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1707.02919v2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Architecture Module | Description | Related Sources |

|---|---|---|

| System input terminal and AI support | Guest attendance forecasting for school kitchens in COVID or flu seasons to optimize food production. Prediction data can be derived from dishwashing systems, with plate counting by computer vision. | Refs. [44,45] |

| System input terminal | The expert system can be connected to food waste trackers to collect feedback from students on the reasons of plate waste, enabling it to generate recommendations for reducing waste. | Ref. [46] |

| System input terminal and AI support | The expert system can be integrated with mobile applications or web surveys to gather data on students’ dietary preferences. This data can be used to generate school menus or recommend specific dishes for inclusion/exclusion in the menu. | Ref. [47] |

| System input terminal and AI support | Waste-tracking devices can transfer data to improve school menu based on food waste classification and monitor KPI “Daily per-meal food waste”. | Refs. [47,48] |

| LLM support | Text summarization is a valuable feature when multiple recommendations are provided to users. Depending on their level of details, some recommendations may overlap and can be effectively summarized. | Ref. [49] |

| AI and LLM support | Clustering algorithms and LLMs can filter questions and recommendations according to specific requests of users. Another approach is the application of the technology “Retrieval-Augmented Generation” (RAG). RAG can search appropriate recommendations using distance algorithms and summarize answers using LLM with a possibility to review source texts. | Section 2.4, [50] |

| The Number of Perceptrons (Dim_Feedforward) | Training Parameters | MB Allocated |

|---|---|---|

| 2048 | 30,927,366 (100%) | 118 (100%) |

| 1024 | 28,826,375 (93%) | 110 (93%) |

| 512 | 27,775,751 (90%) | 106 (90%) |

| 256 | 27,250,439 (88%) | 104 (88%) |

| Task | mBERT | LVBERT |

|---|---|---|

| POS (Accuracy) | 96.6 | 98.1 |

| NER (F1-score) | 79.2 | 82.6 |

| UD (LAS) | 85.7 | 89.9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kodors, S.; Apeinans, I.; Zarembo, I.; Lonska, J. RecGen: No-Coding Shell of Rule-Based Expert System with Digital Twin and Capability-Driven Approach Elements for Building Recommendation Systems. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 10482. https://doi.org/10.3390/app151910482

Kodors S, Apeinans I, Zarembo I, Lonska J. RecGen: No-Coding Shell of Rule-Based Expert System with Digital Twin and Capability-Driven Approach Elements for Building Recommendation Systems. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(19):10482. https://doi.org/10.3390/app151910482

Chicago/Turabian StyleKodors, Sergejs, Ilmars Apeinans, Imants Zarembo, and Jelena Lonska. 2025. "RecGen: No-Coding Shell of Rule-Based Expert System with Digital Twin and Capability-Driven Approach Elements for Building Recommendation Systems" Applied Sciences 15, no. 19: 10482. https://doi.org/10.3390/app151910482

APA StyleKodors, S., Apeinans, I., Zarembo, I., & Lonska, J. (2025). RecGen: No-Coding Shell of Rule-Based Expert System with Digital Twin and Capability-Driven Approach Elements for Building Recommendation Systems. Applied Sciences, 15(19), 10482. https://doi.org/10.3390/app151910482