Research on the Deviatoric Stress Mode and Control of the Surrounding Rock in Close-Distance Double-Thick Coal Seam Roadways

Abstract

1. Introduction

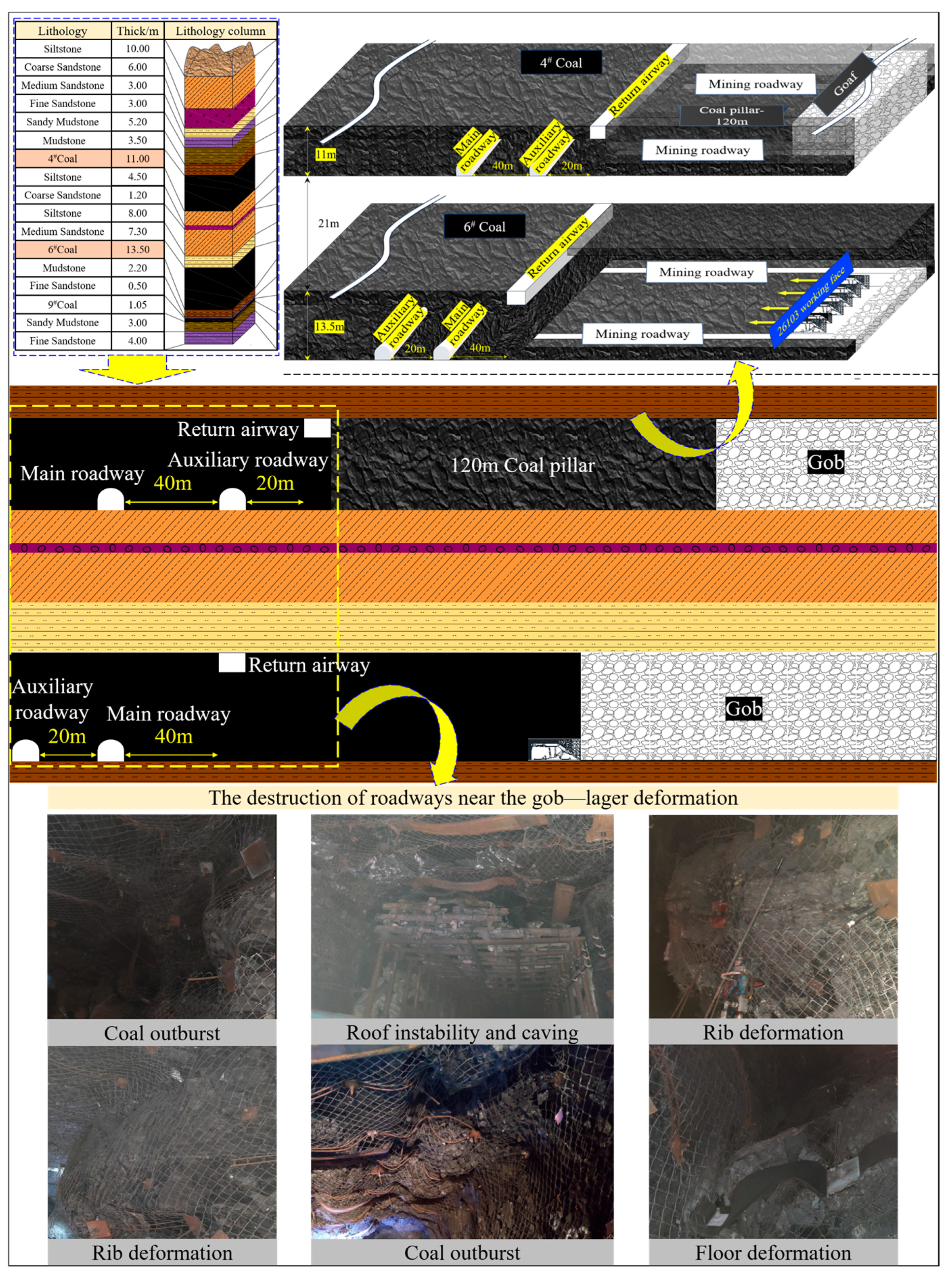

2. Engineering Background

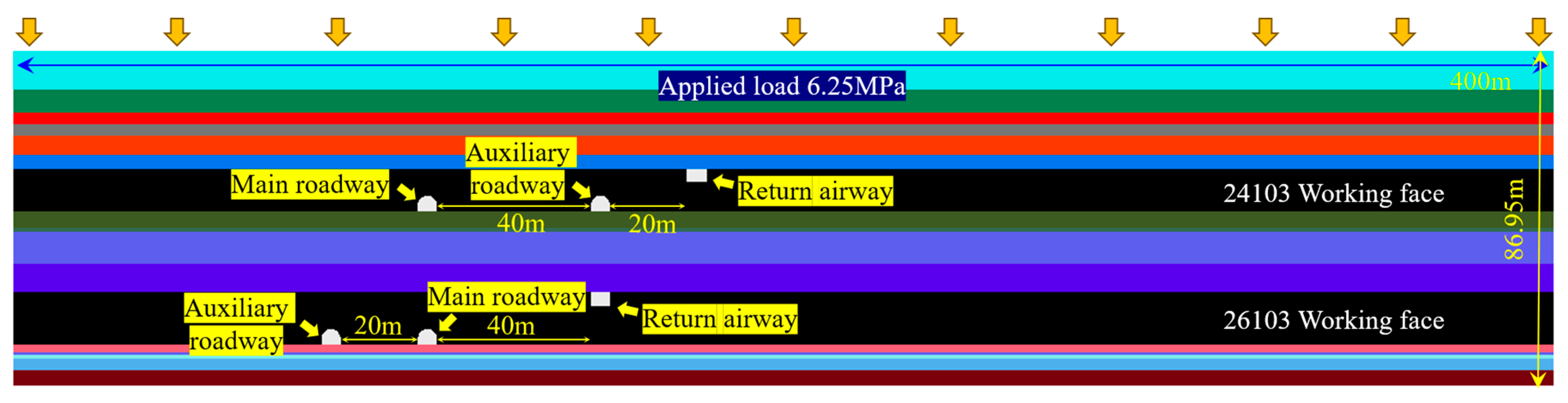

3. Simulation and Analysis of Stress Evolution of the Main Roadways in CSDECS

3.1. The Establishment of the Model

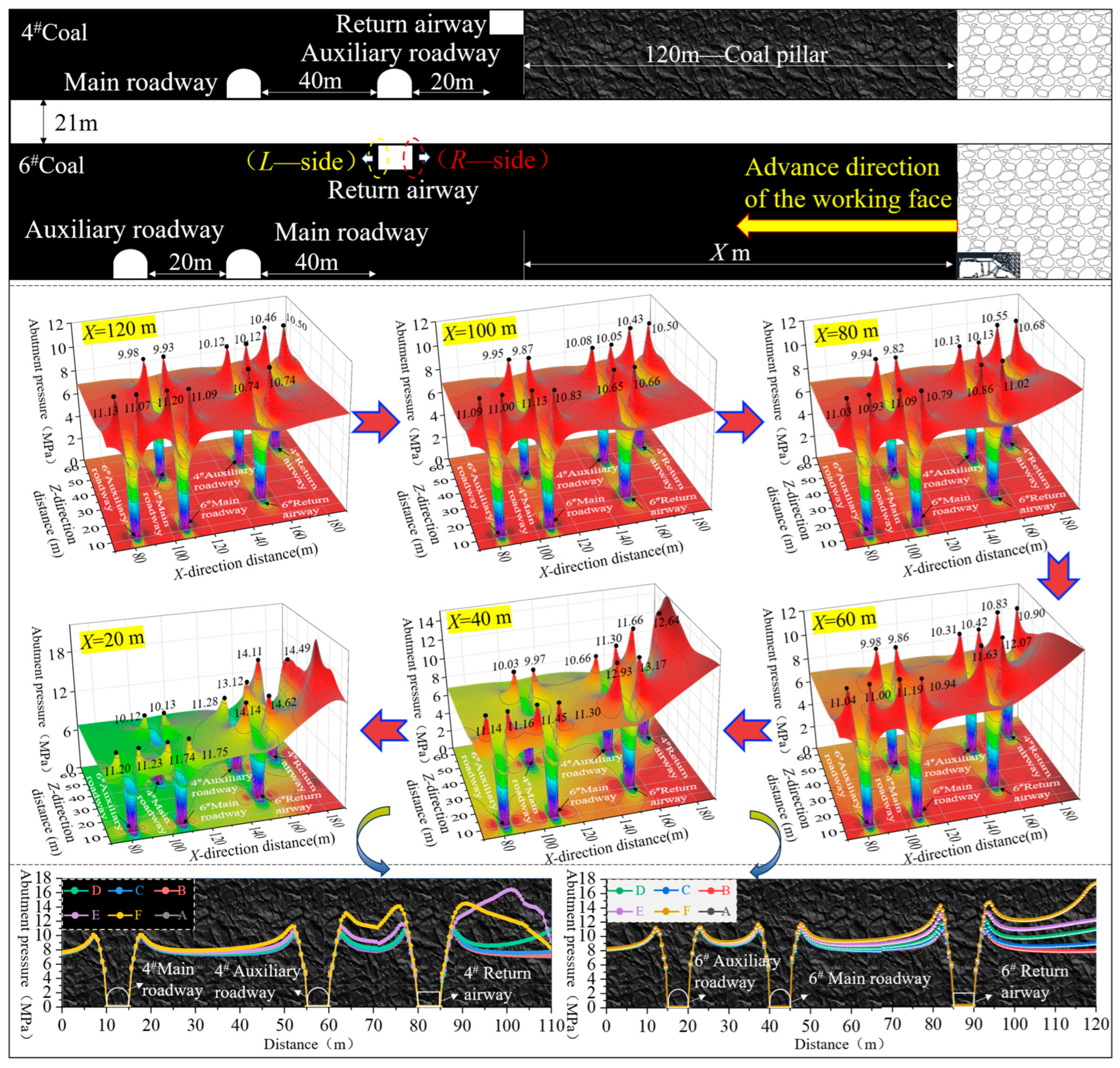

3.2. Evolution of the Abutment Pressure Field of the Main Roadway in CSDECS

- (1)

- As the WSP decreases, the outward shift of the peak abutment pressure in the return air roadways of the CSDECS becomes much higher than that in the surrounding rock of other roadways. The range of the fractured zone in the return air roadways of the two coal seams expands significantly. This indicates that, during the process of reducing the WSP, controlling the surrounding rock of the return airways of the CSDECS is the key research focus.

- (2)

- Since the 4# main roadway, 6# main roadway, and 6# auxiliary roadway are far from the 26103 panel, the MAP on the sides of these main roadways does not change significantly due to mining throughout the entire process. When the WSP is less than 40 m, the MAP on the sides of the 4# auxiliary roadway shows an asymmetric increase. Additionally, the stress increase on the M-S of the roadway (denoted as the R-side, and similarly hereafter) is about 1.8 MPa higher than on the NM-S (denoted as the L-side). Comparing the changes reveals that, since the 4# return airway is closest to the working face, it is significantly affected by mining activities. The MAP on the sides of the 4# return airway shows a marked asymmetric increase when the WSP is less than 80 m. The MAP on the R-side of the 4# return airway remains higher than on the L-side. While reducing the WSP, the MAP increases by approximately 33.5% and 38.1%, respectively, due to the effects of superimposed mining. Compared to the 4# return airway, as the WSP is less than 100 m, the MAP on sides of the 6# return airway also shows an asymmetric increase due to mining, with a higher stress increase than that observed on the 4# return airway.

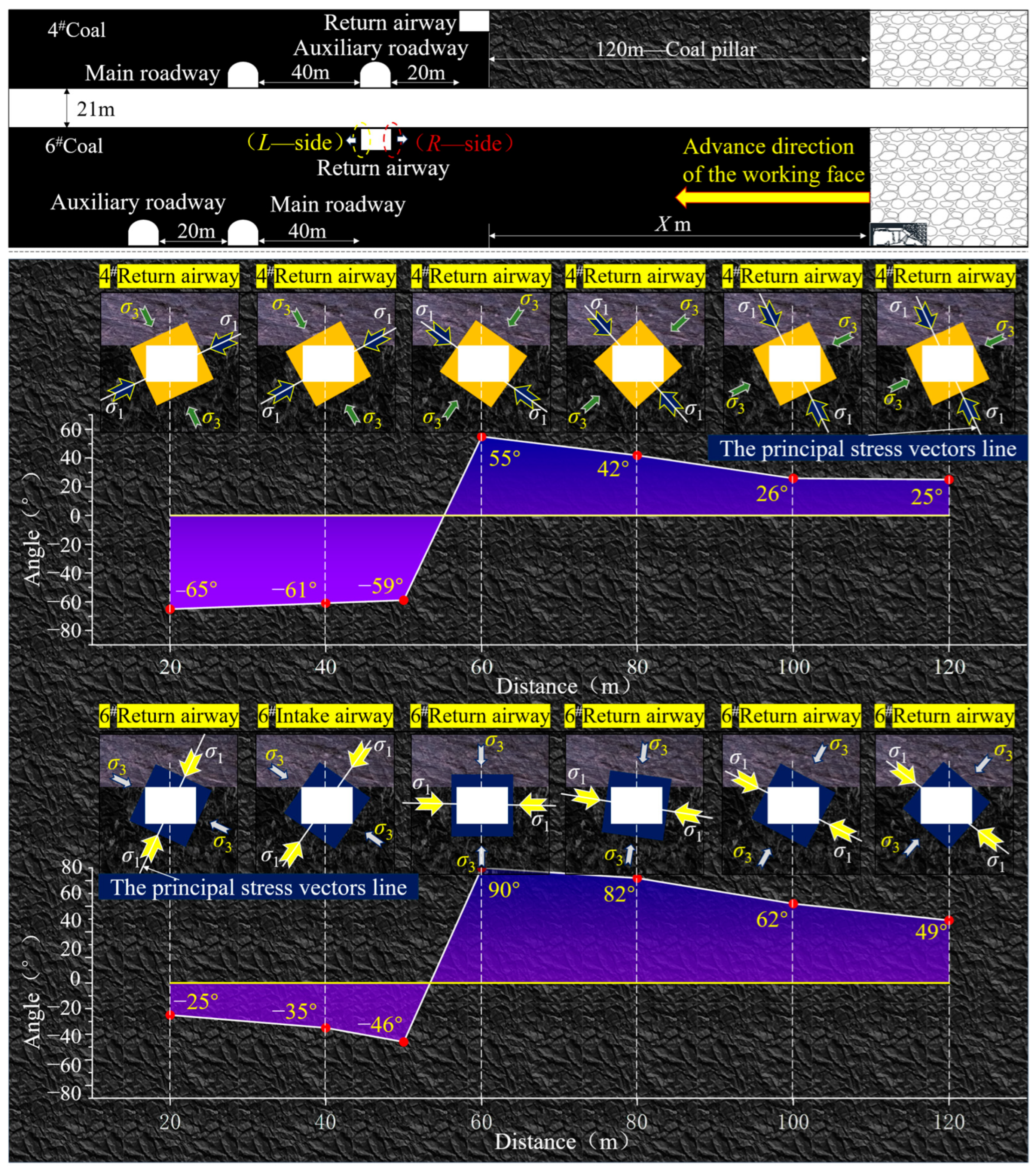

3.3. Evolution of Principal Stress Vector Deflection in the CSDECS

- (1)

- As the WSP decreases, the deflection patterns of the MPSV of the upper and lower coal seams are as follows: towards the solid coal side → nearly horizontal direction → towards the goaf side. The approximate trace of the spin of the MPSV resembles the shape of “︺”.

- (2)

- The angle α gradually increases, ranging from 25° to 65°, with a difference of 40°. The angle α in the lower coal seam first increases and then decreases, with a change magnitude greater than that of the upper seam. The lower coal seam exhibits greater variability, the physical essence of which stems from the multiple superposition, transfer, and redistribution processes of mining-induced stress. Specifically, the extraction of the upper seam causes the initial stress field to undergo its first redistribution, resulting in a pattern of low pressure in the goaf area and high pressure in the coal pillar zones. Simultaneously, the stress concentration effect induced by the coal pillars in the upper seam transfers downward to the lower coal seam. Although the lower seam has not yet been mined, its original in situ stress state has already been altered due to the influence of upper seam mining, disrupting the initial equilibrium. When mining advances to the lower seam, the stress field undergoes a second redistribution, particularly in areas affected by the remnant coal pillars from the upper seam. The longwall face in the lower seam is subjected to two superimposed stresses: one is the high stress transferred downward from the coal pillars of the upper seam, and the other is the front abutment pressure generated by the extraction of the lower seam itself. This dual stress superposition effect results in a stress environment significantly different from that of a single ultra-thick coal seam, thereby leading to stronger variability in the lower seam mining conditions.

3.4. The Evolution of ZDSC in CSDECS

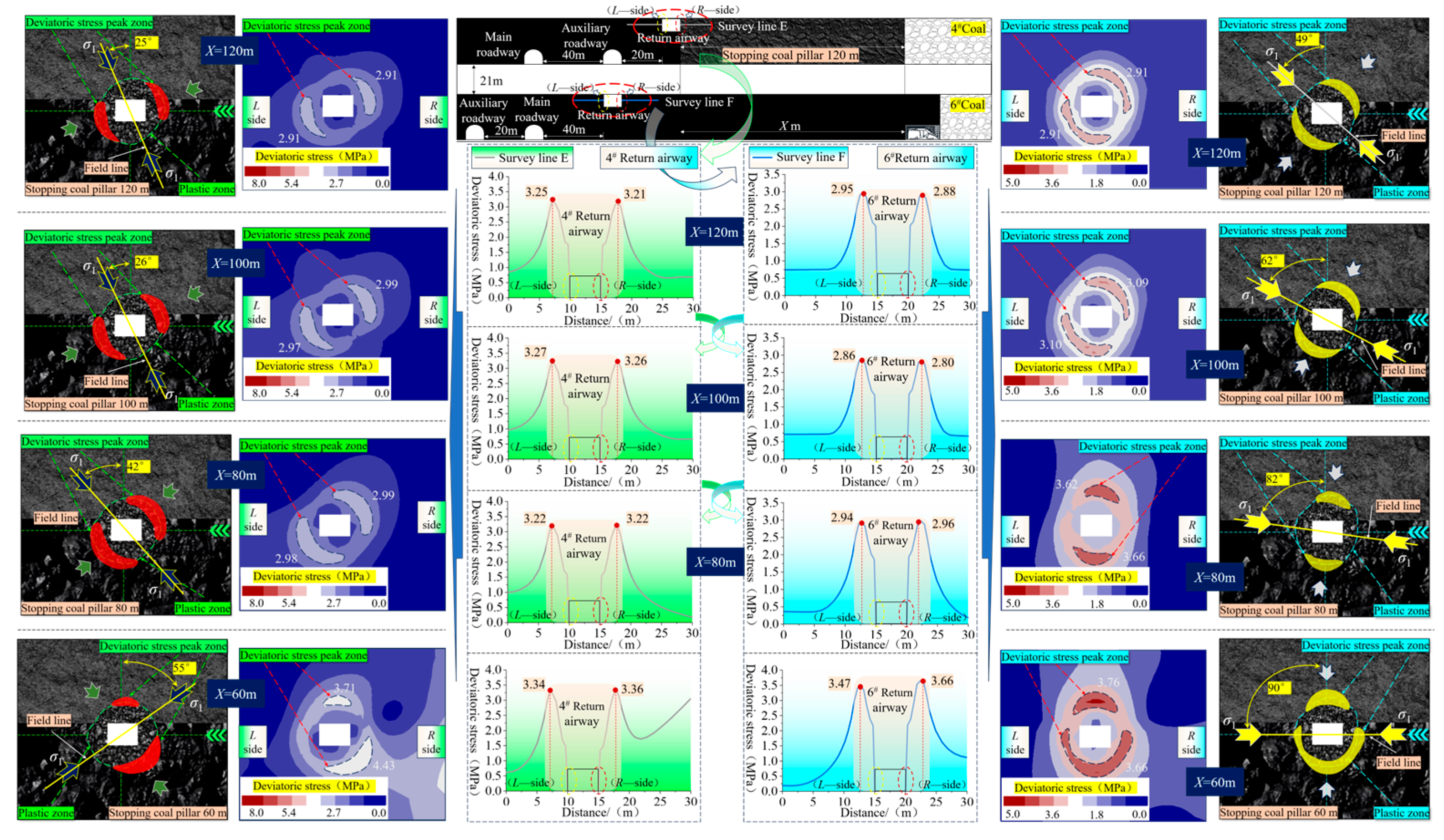

- (1)

- When the WSP (120 m to 20 m) is away from the return airway of the 4# coal seam, the deviatoric stress max values (DSMV) curves on sides of the airways exhibit significant asymmetric loading increase. The amplitude of the increase in the DSMV of the 4# coal seam’s return airway is notably higher than that of the 6# coal seam’s return airway, indicating that the shear failure degree of the 4# airway is much greater than the 6# airway.

- (2)

- The distribution of the DSMV of the return airway in the 4# coal seam exhibits a spatial dynamic evolution law with increasing mining disturbance. As the WSP is reduced from 120 m to 50 m, the ZDSC of the roadway surrounding rock rotates counter-clockwise. Its distribution is specifically as follows: “Both sides of the return airway → Transition area from the bottom corner on the L-side to the shoulder corner on the R-side → Transition area of the roof—Transition area of the bottom corner on the R-side → Transition area of the shoulder corner on the L-side—Transition area of the bottom corner on the R-side,” indicating that after the WSP is decreased, the plastic development trend does not exhibit a symmetrical form. Therefore, the traditional symmetrical support structure of the roadway cannot effectively control the deformation. Meanwhile, when the WSP is 40 m, the ZDSC undergoes a sudden change. The ZDSC of the R-side is connected with the stope, resulting in a sharp increase in peak deviatoric stress intensity and a significant expansion of the peak area range. When the WSP is reduced to 20 m, the ZDSC of the roadway connects with the stope. At this point, the mining influence has shifted to the L-side, while the R-side suffers damage from strong shear forces, causing the DSMV on the L-side to be higher than the other. As the WSP decreases from 50 m to 20 m, the ZDSC on the L-side does not shift, but its range and DSMV increase significantly. Conversely, the ZDSC of the R-side decreases, and the plastic undergoes significant expansion. Eventually, the R-side transforms from a plastic zone to a low-strength bearing zone, and the load-bearing capacity drops considerably. Ultimately, this leads to continuous asymmetric deformation of the roadway, causing support failure.

- (3)

- The distribution and patterns of the ZDSC of the return airway in the 6# coal seam differ significantly from the 4# coal seam. Specifically, when the WSP decreases from 120 m to 20 m, the ZDSC of the 6# airway rotates counterclockwise. Meanwhile, the ZDSC is approximately crescent-shaped. Its evolution law is “the transition area from the bottom corner on the L-side to the shoulder corner on the R-side → the roof–floor → the transition area from the shoulder corner on the L-side to the bottom corner on the R-side → the left and right sidewalls”. Since there is still a 20 m WSP of return airway in the 6# coal seam and the 4# coal seam, as the WSP decreases, the behavior of the ZDSC of the 6# return airway does not respond as significantly as that of the 4# return airway. As mining of the section progresses, the crescent-shaped ZDSC of the airway remains unchanged, indicating that the stability of the 6# airway is better than that of the 4# airway.

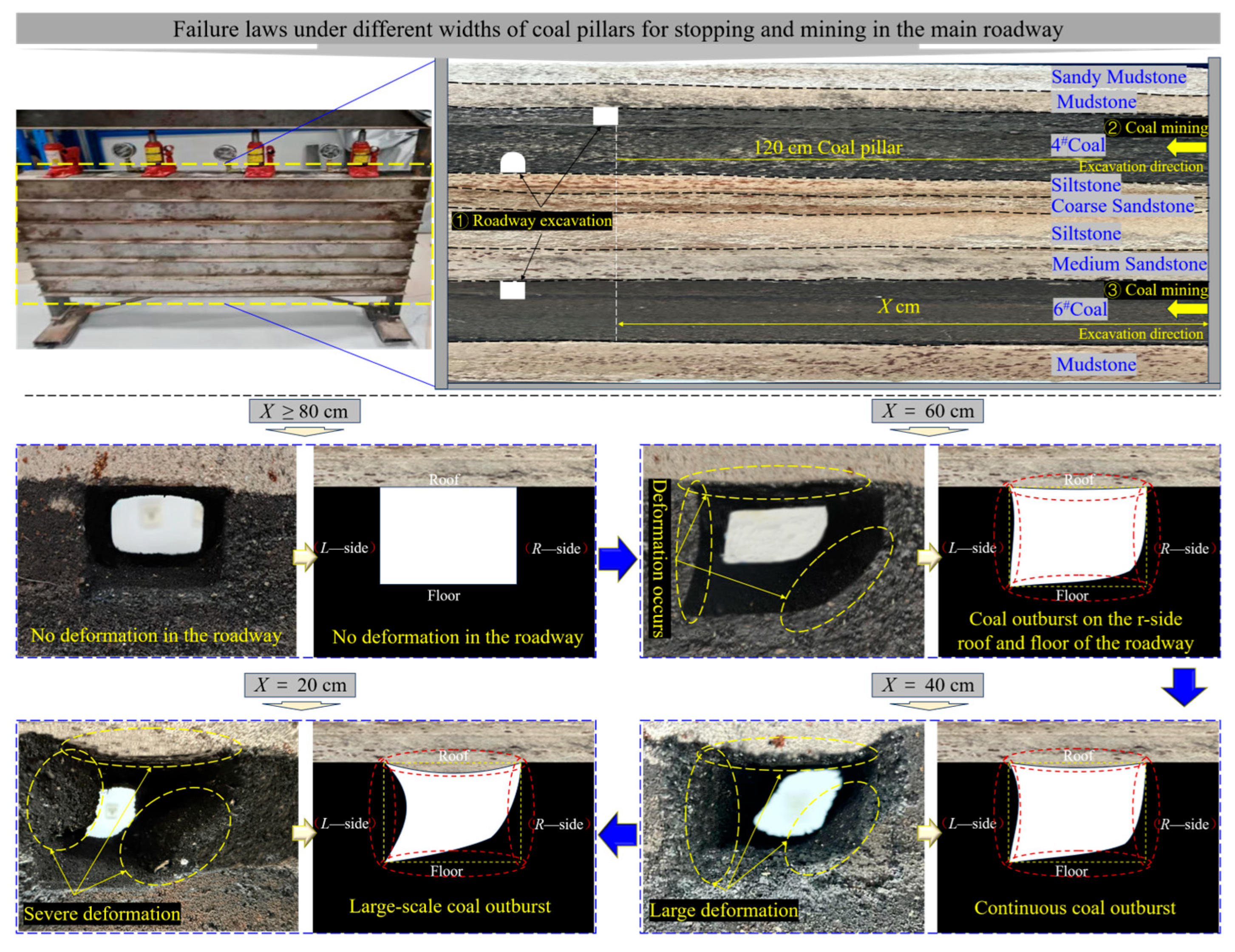

4. Similarity Test of Closely Spaced Double Extra-Thick Coal Seams

5. Evolution Mode of Partial Additional Load in the ZDSC in the Main Roadway of CSDECS

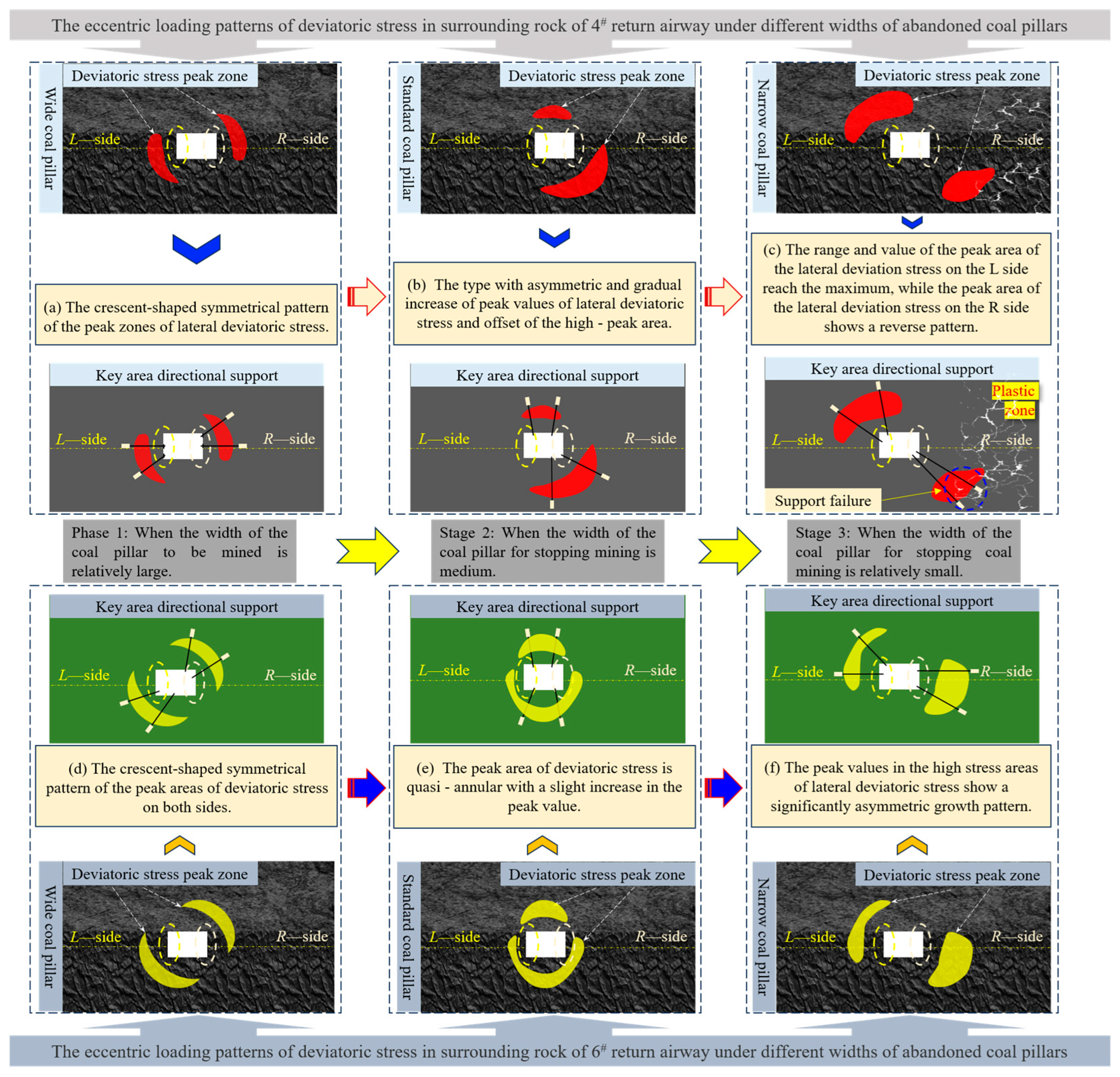

- (1)

- When the WSP is relatively large, the disturbance to the return air main roads of the two coal seams is relatively small. The ZDSC of the main roads exhibits a crescent-shaped, centrosymmetric distribution. The ZDSC of the return airway for the 4# coal seam is mainly distributed. In contrast, the ZDSC of the return air main road for the 6# coal seam is located in the transition zone from the bottom corner on the L-side to the top corner on the R-side. Additionally, the range of the ZDSC in the 6# return airway is larger than that of the 4# return airway. However, since the return airways of the two coal seams are both far from the working face and there is a sufficiently wide protective coal pillar to isolate the strong dynamic load impact caused by mining, the mining disturbance they experience is relatively small, and the conventional support can meet the requirements for the deformation stability of the roadways.

- (2)

- As the WSP decreases from a medium size, the level of mining disturbance on the return air roadways of the two coal seams gradually increases. The ZDSC of the roadways shifts from a centrally symmetric crescent shape to an asymmetric, expanding shape. Similarly, because of the spatial position difference between the two roadways, the levels of increased disturbance vary, and there are differences in the loading patterns of the ZDSC. Specifically, the ZDSC of the 4# return air roadway shifts from both sides toward the transition zone in the right-hand roof corner. While the ZDSC of the 6# return air roadway deviates from the “transition area between the L-side bottom corner and the R-side top corner” to the “roof and floor,” forming a “quasi-annular high-deviatoric-stress area.” The counterclockwise deflection angles of the ZDSC of the 4# return air roadway differ from those in the 6# coal seam, indicating that the plastic zones develop along divergent paths after mining. Therefore, the key support areas should concentrate on the distribution range of the ZDSC.

- (3)

- As the WSP is relatively small, further reducing the WSP intensifies the mining disturbance on the return air roadways of the coal seams. The differences in the evolution of the ZDSC are significant. The ZDMV of the L-side in 4# the return air roadway reaches its max, while the ZDSC on the R-side shows a reversal. Furthermore, these peak areas are primarily distributed in the transition zones between the roadway side and the roof, as well as between the roadway side and the floor, with the peak areas moving outward and increasing simultaneously. The reversal of the deviatoric stress peak area on the R-side indicates that this side is connected with the stope. At the same time, both the peak value and the range of the ZDSC of the L-side increase, suggesting that the mining influence has shifted from the R-side to the L-side of the roadway. Conversely, the deviatoric stress peak areas around the 6# return air roadway exhibit significant asymmetric growth, and the shape of the peak area does not reverse, indicating that the 4# return air roadway is more severely affected by mining.

- (4)

- The disparity arises from the mechanical effect that prior extraction of the 4# coal seam induces stress release in the goaf and stress concentration in coal pillars, which transfers downward and causes heterogeneous stress disturbances in the 6# coal seam. During the mining of the 6# coal seam, as the 26103 panel advances beneath these pillars, the concentrated stress superimposes with mining-induced stress, resulting in a significant increase in the roadway. The difference in stress distribution primarily stems from the mining sequence and spatial positioning: stress transfer in th 4# coal seam is dominated by downward transmission from coal pillars, while the 6# coal seam experiences a more complex and intense perturbation due to the superposition of its own mining stress and residual stress from the upper layer.

6. Engineering Tests and Mine Pressure Monitoring

6.1. Support Strategy and Scheme for the 4# Return Airway

6.2. Mine Pressure Monitoring

7. Discussion

- (1)

- Different research indicators are selected, each representing distinct physical implications (as shown in Table 2). After comprehensive consideration, deviatoric stress is adopted as the primary research indicator. This is because it can not only characterize the stress state at a point but also represent the shear failure in the deep rock mass.

- (2)

- The research on the influence of different WSP in the underlying mining face of CSDECS on the stability of the main roadway is still lacking. Meanwhile, at present, most of the research on the setting of the width of coal pillars left during stopping mining in roadways and the control deformation is limited to the analysis of the evolution of the vertical stress of the roadway surrounding rock, and the surrounding rock control schemes are mostly symmetrical.

- (3)

- The traditional symmetrical support system for roadways lacks an understanding of “the influence of the deflection of the principal stress and the distribution of the ZDSC on the key control area of the roadway“. Therefore, through the research on the influence of different WSP left during stopping mining in the underlying face of CSDECS on the stability of the roadway, this paper obtains the deflection law of the principal stress vector and the deviatoric stress peak area’s incremental loading mode, determines the key control direction of the roadway, and proposes a partitioned asymmetric support method for roadways based on the deviatoric stress incremental loading mode. This method makes up for the limitation of using the traditional symmetrical support method for roadways regardless of the size of the coal pillars left during stopping mining and is of great significance for guiding engineering practice.

8. Conclusions

- (1)

- During the advancing process of the lower seam face in CSDECS, the orientation of the maximum principal stress in both the upper and lower seams deviates, following an approximate “︺”-shaped trajectory: the maximum principal stress vector line first “\”→ then “—” → last “/”.

- (2)

- The evolution of the ZDSC and the main roadways in the adjacent working faces all shows three-stage characteristics. For the 4# coal seam, it is characterized by crescent-shaped symmetry → slow and asymmetric increase of the peak value and the offset of the ZDSC → the ZDSC on the NM-S reaches the maximum while the M-S shows the reverse trend. For the 6# coal seam, it is characterized by crescent-shaped symmetry → quasi-annular distribution with a slight increase in the peak value → significant and asymmetric increase of the peak values.

- (3)

- By studying the ZDSC loading patterns under different WSP, key control areas were identified. Reinforcement support was applied at corresponding locations, ensuring gateway stability while optimizing the WSP to 50 m (a reduction of 30 m), significantly improving the resource recovery rate.

- (4)

- Based on the loading patterns of ZDSC corresponding to different WSP, an asymmetric support method for different zones was proposed. The approach breaks through the traditional symmetric support form and provides important guidance for engineering practice.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, X.L.; Chen, S.J.; Li, Z.H.; Wang, E.Y. Rockburst mechanism in coal rock with structural surface and the microseismic (MS) and electromagnetic radiation (EMR) response. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2021, 124, 105396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, F.; Yin, H.; Ren, H.; Cheng, W.; Tai, S.; Miao, T.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, B. Trapezoidal Failure Behavior and Fracture Evolution Mechanism of Overburden in Extra-thick Coal Mining in Weakly Cemented Strata. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2024, 57, 11239–11260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Guo, X.; Wu, X.; Chen, S.; Zhang, N. Fractal characteristics of overburden fissures in shallow thick coal seam mining in loess gully areas. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0274209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Zhang, P.; Wu, R.; Fu, M.; Ou, Y. Research on the overburden deformation and migration law in deep and ex-tra-thick coal seam mining. J. Appl. Geophys. 2021, 190, 104337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, X.; Li, C.; Li, J.; Wu, L. Law of strata pressure behavior of surrounding rock in nearby goaf roadway for ex-tra-thick coal seams of Datong mine area. Front. Earth Sci. 2023, 10, 1015378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Li, G.-C.; Li, Y.-Q.; Zhang, Q.-C.; Zhu, C.-Q. Stress evolution characteristics of the intensively mining-induced surrounding roadways within an extra-thick coal seam: A case study from the Tashan coal mine, China. J. Cent. South Univ. 2023, 30, 3840–3854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, R.; Liu, S.; Wang, H.; Li, Z.; Huang, P.; Dou, H. Research on the deformation mechanism and ACC control technology of gob-side roadway in an extra-thick coal seam with varying thickness. Energy Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 1913–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Zhao, W.; Wang, J.; Jiang, M.; Shen, F.; Zhang, Y.; Miao, C. Research on Failure Mechanism and Stability Control Technology of Dynamic Pressure Roadway in Ultra-Thick Coal Seams Under a High Depth of Cover. Min. Metall. Explor. 2023, 40, 1955–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Lu, G.; Xia, H.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Y. Control of the chamber in extra-thick coal seam based on fracture characteristics of coal rock and mass. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2020, 2020, 1529797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, J.; Chen, A.; Li, X.; Bian, H.; Zhou, G.; Wu, Z.; Tang, J. Analysis of surrounding rock control technology and its application on a dynamic pressure roadway in a thick coal seam. Energies 2022, 15, 9040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Jiang, Z.; Xie, S. Mechanism and key parameters of stress load-off by innovative asymmetric hole-constructing on the two sides of deep roadway. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol. 2023, 10, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.Y.; Li, W.S.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, L.J.; Ren, S.A. Research on the instability mechanism and control of main road way in thick and extra-thick coal seam mining. J. Min. Saf. Eng. 2025, 42, 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.J. Study on Optimization of End-mining Coal Pillar in Top-coal Caving Mining of Extremely Thick Coal Seam. Coal Technol. 2019, 38, 26–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Wang, W.; Ge, J.; Yang, Z.; Qi, Q. Development characteristics of the rock fracture field in strata overlying a mined coal seam group. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0268955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Sun, Y.; Xu, J.; Zhao, L. Study on the evolution of fractures in overlying strata during repeated mining of coal seams at extremely close distances. Front. Earth Sci. 2024, 12, 1472939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, R.; Cao, S.; Li, Y.; Li, G. Development of overburden fractures for shallow double thick seams mining. J. China Coal Soc. 2018, 43, 2261–2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Kang, Q.; Yin, S.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Gao, L. Stratification Failure Mechanism of Coal Pillar Floor Strata with Different Strength in Short Distance Coal Seams. Geofluids 2022, 2022, 2598738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Kong, D.; Li, P.; Wen, Z.; Li, F.; Zuo, Y.; Wu, G. The migration and evolution law of overlying strata and the instability and failure characteristics of end face roof under the condition of ascending mining in close distance coal seam: Case study. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2024, 165, 108809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.; Zheng, X.; Wang, E.; Kang, Q.; Zhang, X. Non-uniform failure and differential pressure relief technology of roadway under ir-regular goafs in deep close-distance coal seams. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 18527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, D.; Wu, Y.; Chen, H.; Chu, X.; Li, Y. Instability mechanism and prevention technology of roadway in close distance and extra thick coal seam under goaf. J. China Coal Soc. 2019, 44, 2682–2690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.; Ren, Y.; Chen, D.; Guo, W.; Li, S.; Li, Y.; Ma, X.; Ye, Q.; Chang, J.; Liang, D.; et al. A case study on coordinated asymmetric support-relief control for roadway surrounding rock under multiple dynamic pressures in thick coal seams. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2025, 179, 109821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Chen, D.; Xie, S. Failure analysis and innovative pressure load-off control technology of deep coal roadway both ribs: A case study. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2024, 158, 107976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Liu, C.; Zhao, G. Study on Coal Pillar Setting and Stability in Downward Mining Section of Close Distance Coal Seam. Energies 2024, 17, 5441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Guo, F.; Li, Z.; Ma, X.; Xie, S.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Z. Study on the influence and control of stress direction deflection and partial-stress boosting of main roadways surrounding rock and under the influence of multi-seam mining. Energies 2022, 15, 8257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Li, Z.; Xie, S.; Wang, Z.; Jiang, Z.; Jia, Q.; Wang, Y. The J2 evolution model and control technology of the main roadway sur-rounding rock under superimposed influence of double-coal seam mining. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 17569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z. Elasticity; Beijing Higher Education Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2006. [Google Scholar]

| Stratum | Thickness/mm | Ratio | Sand/kg | Lime/kg | Gypsum/kg | Water/kg | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Immediate floor | 100 | 6:0.5:0.5 | 13.1 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.53 |

| 2 | 6# Coal | 130 | 8:0.7:0.3 | 20.5 | 1.8 | 0.8 | 1.96 |

| 3 | Medium Sandstone | 70 | 7:0.6:0.4 | 9.4 | 0.79 | 0.79 | 1.17 |

| 4 | Siltstone | 80 | 6:0.5:0.5 | 10.8 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 1.28 |

| 5 | Siltstone (Sandstone) | 50 | 6:0.5:0.5 | 6.7 | 0.56 | 0.56 | 1.07 |

| 6 | 4# Coal | 110 | 8:0.7:0.3 | 17.3 | 1.5 | 0.7 | 1.68 |

| 7 | Mudstone | 30 | 6:0.5:0.5 | 4.3 | 0.36 | 0.36 | 0.9 |

| 8 | Sandy Mudstone | 30 | 6:0.5:0.5 | 4.3 | 0.36 | 0.36 | 1.03 |

| Stress Value Scale | Intrinsic Nature | Physical Significance | Application | Evaluation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual stress component (σxx, σyy, σzz, τxz, τxy, τyz, τzx, τzy, and τyx) | Components of the stress tensor | Stress in a specific direction within a given coordinate system | Original data describing the stress state | It does not fully characterize the stress state at a point |

| Single principal stress (σ1, σ2, and σ3) | Eigenvalues of the stress tensor | Extreme values of the stress state at a point | Applied to strength theories based on maximum tensile/compressive and shear stresses. | It does not fully characterize the stress state at a point |

| Principal deviatoric stress S1 | Eigenvalues of the deviatoric stress tensor | Extreme values of the stress component causing shape distortion | Fundamental for calculating J2 in plasticity analysis. | It can characterize the stress state at a point |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, D.; Tang, J.; He, W.; Gao, C.; Wang, C. Research on the Deviatoric Stress Mode and Control of the Surrounding Rock in Close-Distance Double-Thick Coal Seam Roadways. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 10416. https://doi.org/10.3390/app151910416

Chen D, Tang J, He W, Gao C, Wang C. Research on the Deviatoric Stress Mode and Control of the Surrounding Rock in Close-Distance Double-Thick Coal Seam Roadways. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(19):10416. https://doi.org/10.3390/app151910416

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Dongdong, Jiachen Tang, Wenrui He, Changxiang Gao, and Chenjie Wang. 2025. "Research on the Deviatoric Stress Mode and Control of the Surrounding Rock in Close-Distance Double-Thick Coal Seam Roadways" Applied Sciences 15, no. 19: 10416. https://doi.org/10.3390/app151910416

APA StyleChen, D., Tang, J., He, W., Gao, C., & Wang, C. (2025). Research on the Deviatoric Stress Mode and Control of the Surrounding Rock in Close-Distance Double-Thick Coal Seam Roadways. Applied Sciences, 15(19), 10416. https://doi.org/10.3390/app151910416