Therapeutic Potential of Quercetin in the Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease: In Silico, In Vitro and In Vivo Approach

Abstract

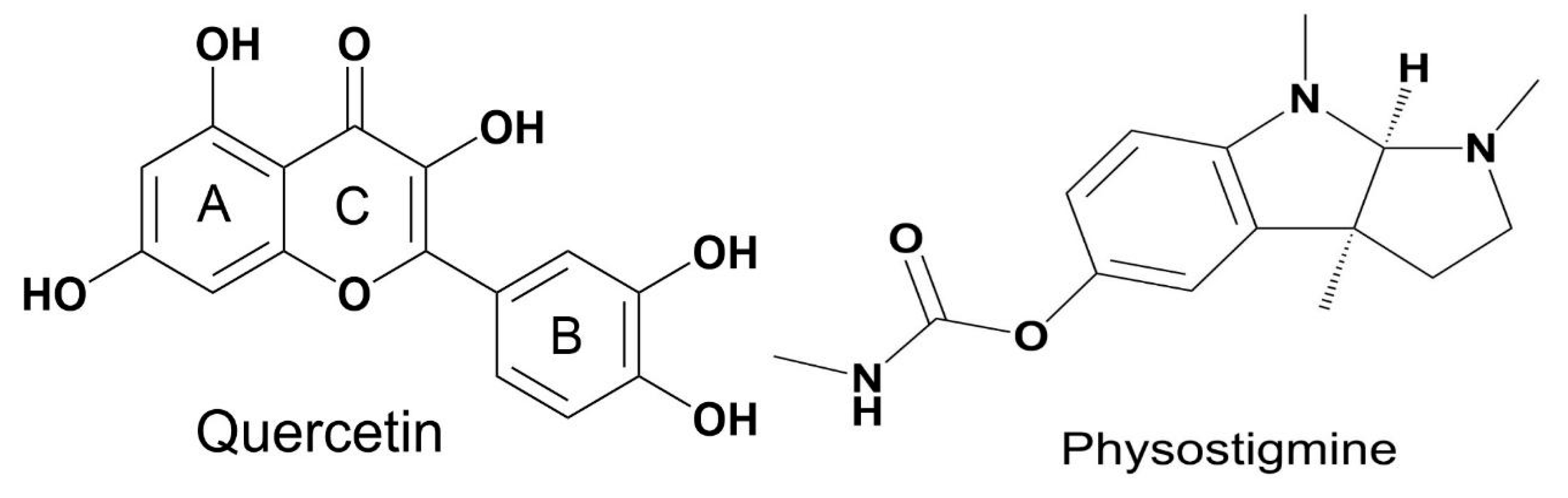

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Molecular Dynamics Procedures

2.2. In Vitro Tests

2.2.1. DPPH Antioxidant Assay

2.2.2. Inhibitory Enzymatic Evaluation in AChE

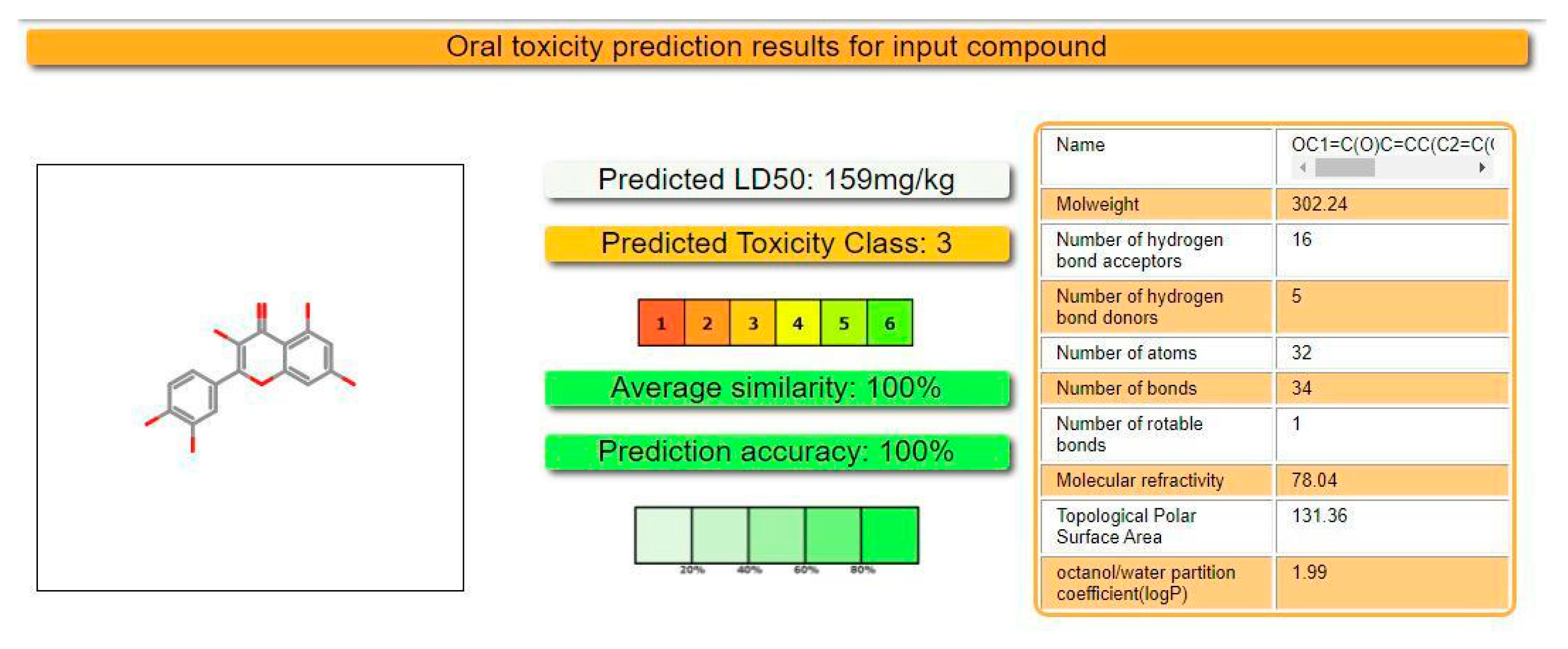

2.3. Prediction of Oral Toxicity

2.4. In Vivo Tests

2.4.1. Substances Used

2.4.2. Animals

2.4.3. Experimental Aquarium

2.4.4. Passive Avoidance Response Test

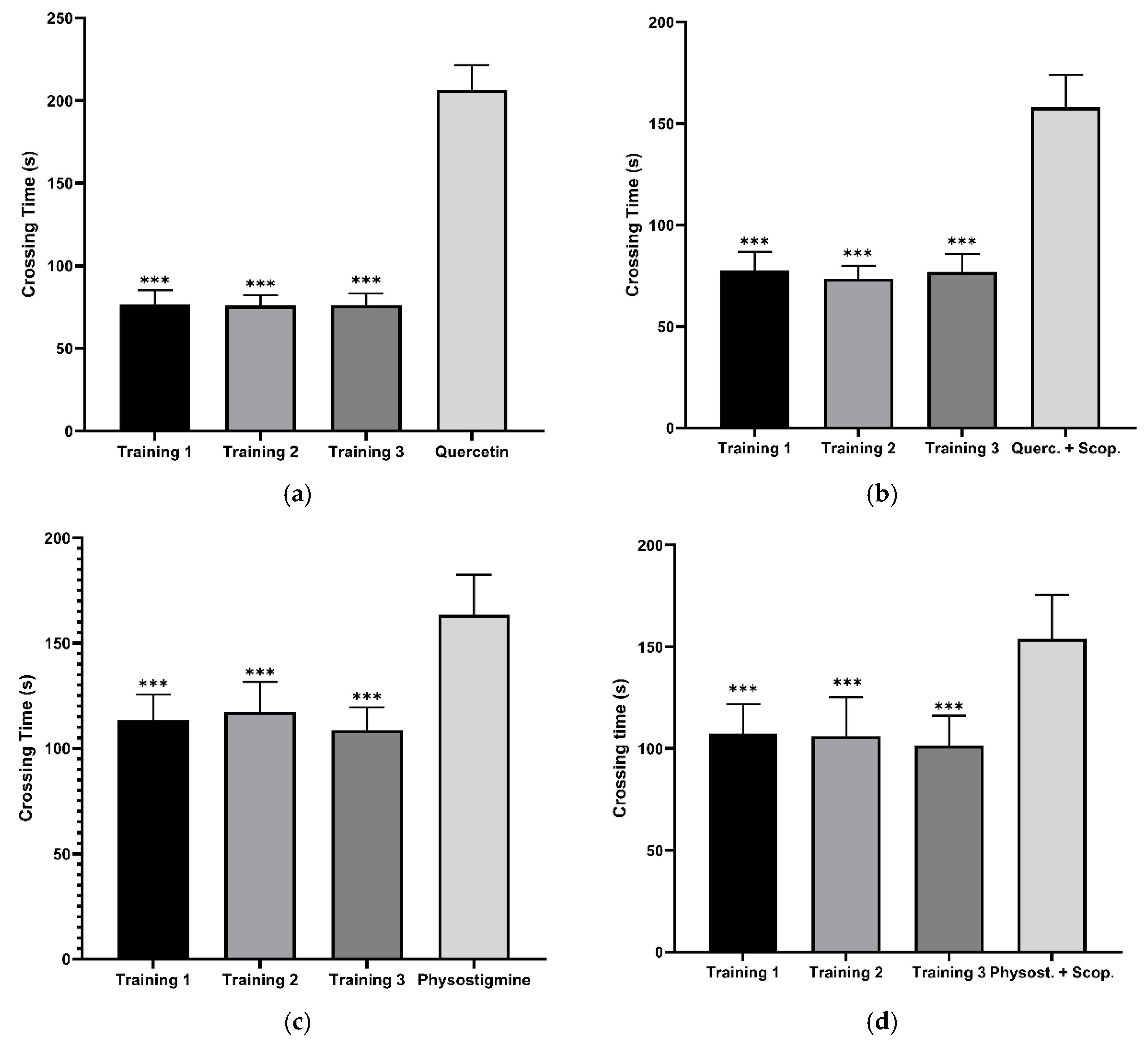

2.4.5. Experimental Procedure

2.4.6. Ethical Considerations and Experimental Design

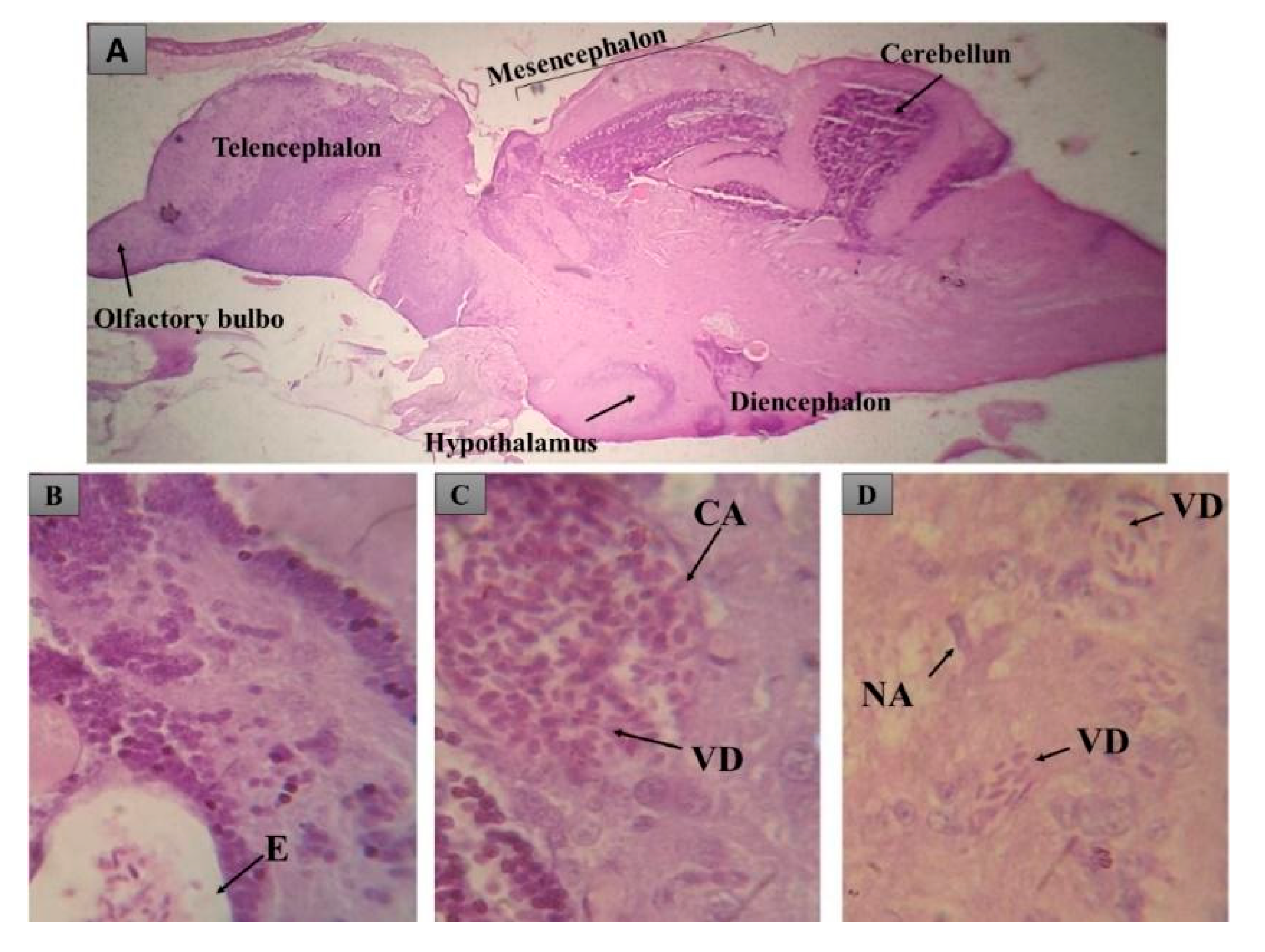

2.5. Histopathological Analysis

2.6. Evaluation of Histopathological Alterations

- a: first stage alterations

- b: second stage alterations

- c: third stage alterations

- na: number of alterations considered to be first stage

- nb: number of alterations considered to be second stage

- nc: number of alterations considered to be third stage

- N: number of fish analyzed per treatment

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

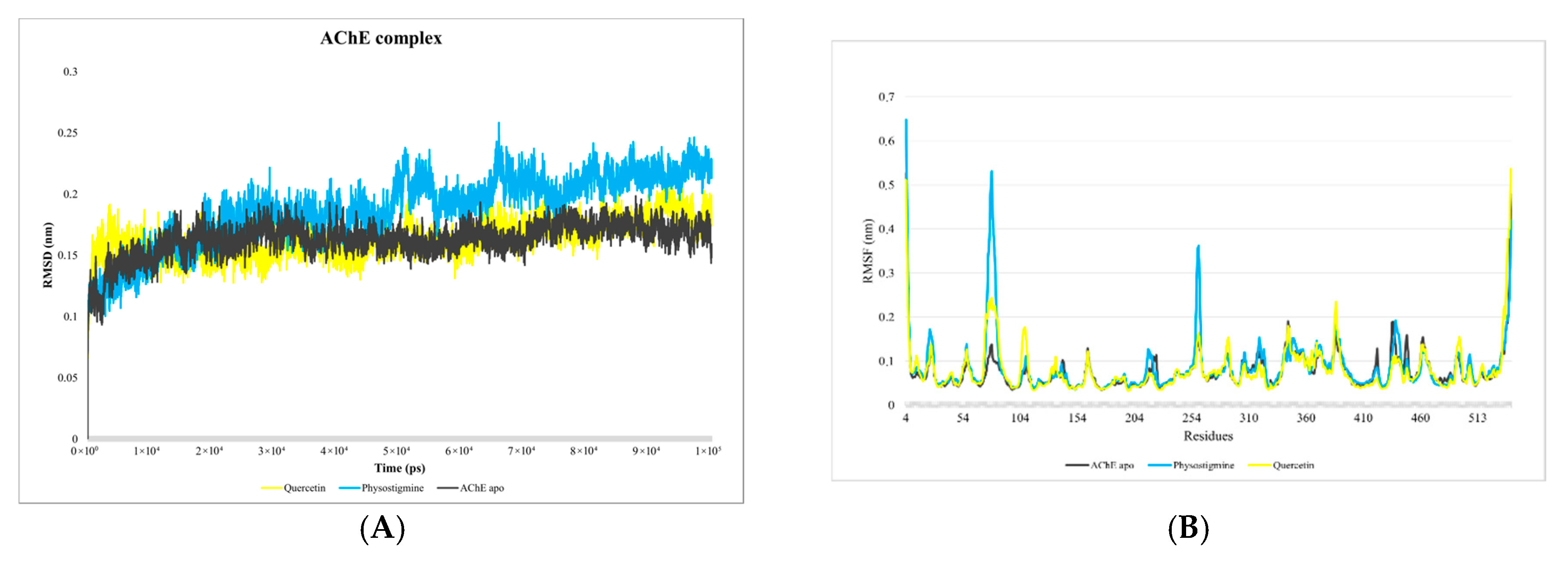

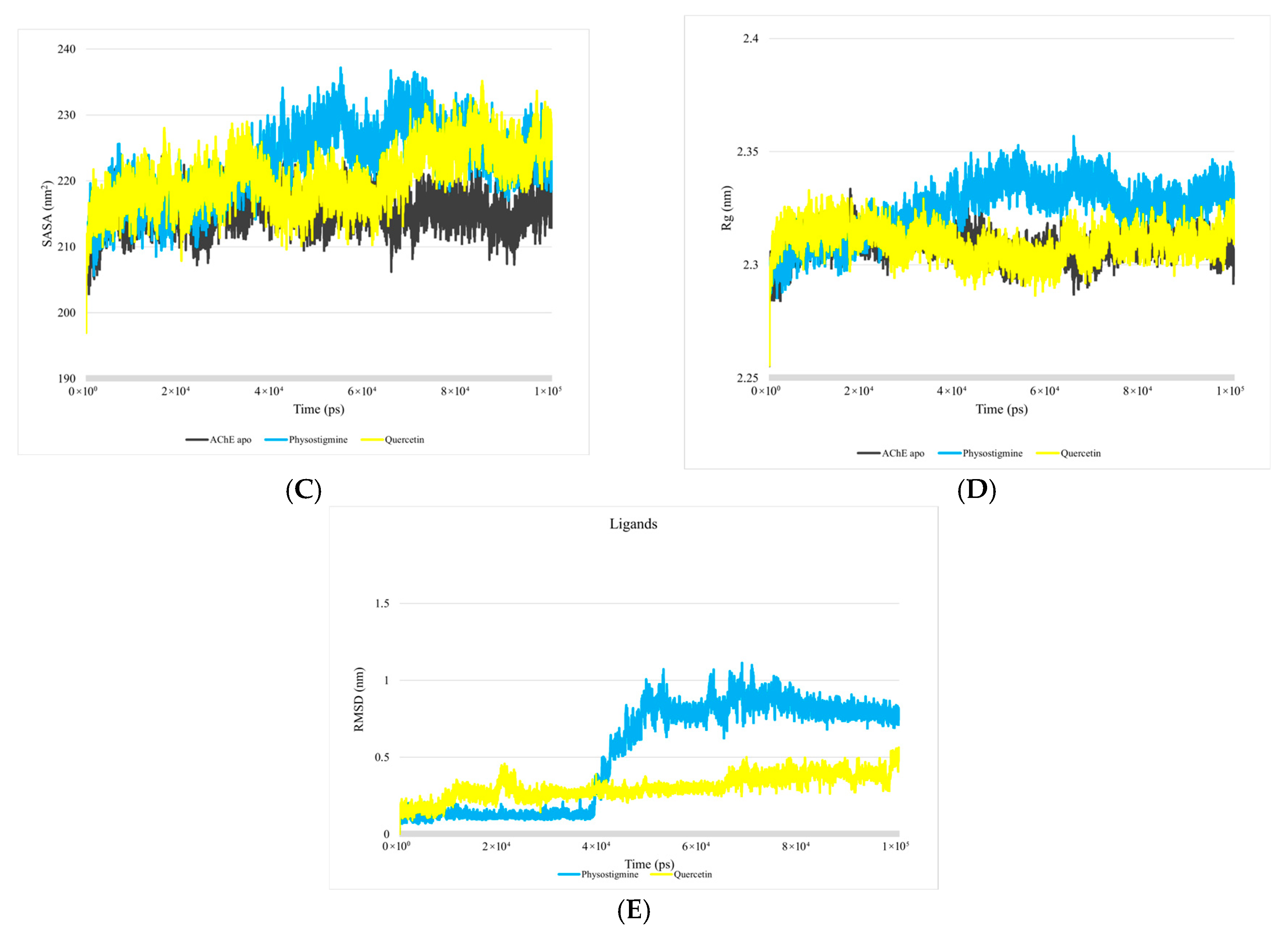

3.1. Analysis of Molecular Dynamics Simulations

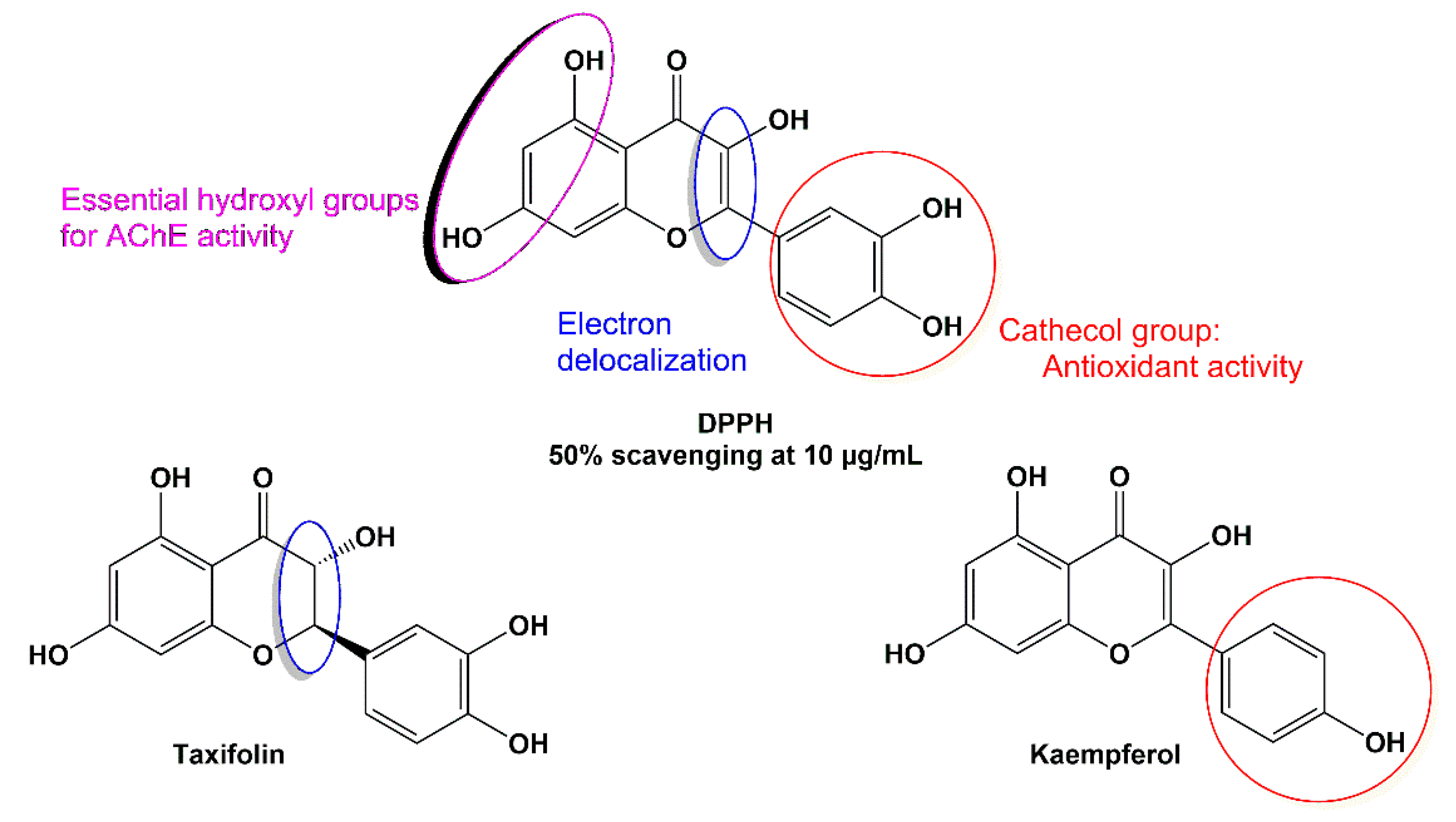

3.2. Results of In Vitro Tests

3.2.1. DPPH Antioxidant Activity Results

3.2.2. Inhibitory Activity on AChE

3.3. In Silico Evaluation of Lethal Dose

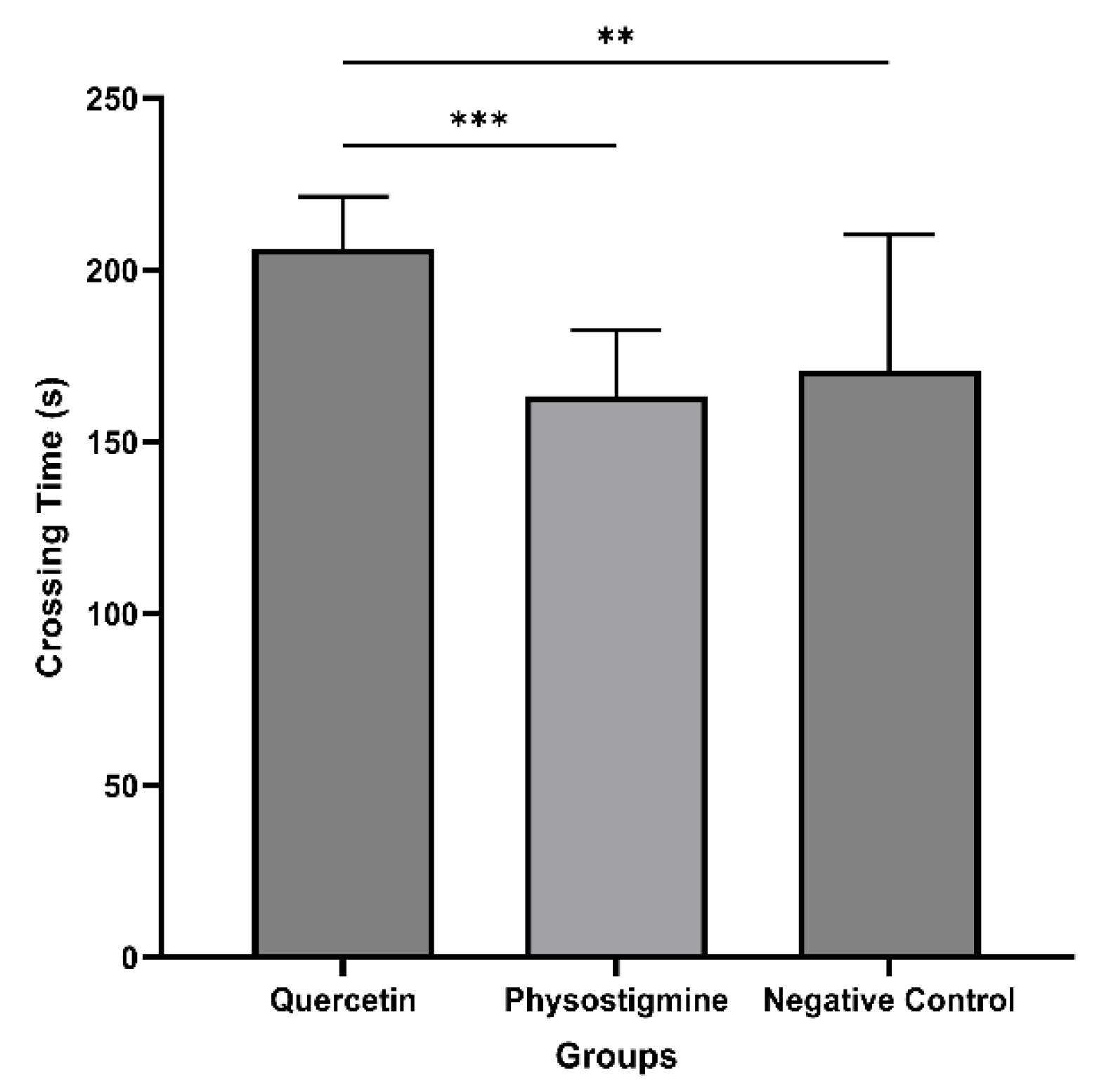

3.4. Evaluation of In Vivo Tests

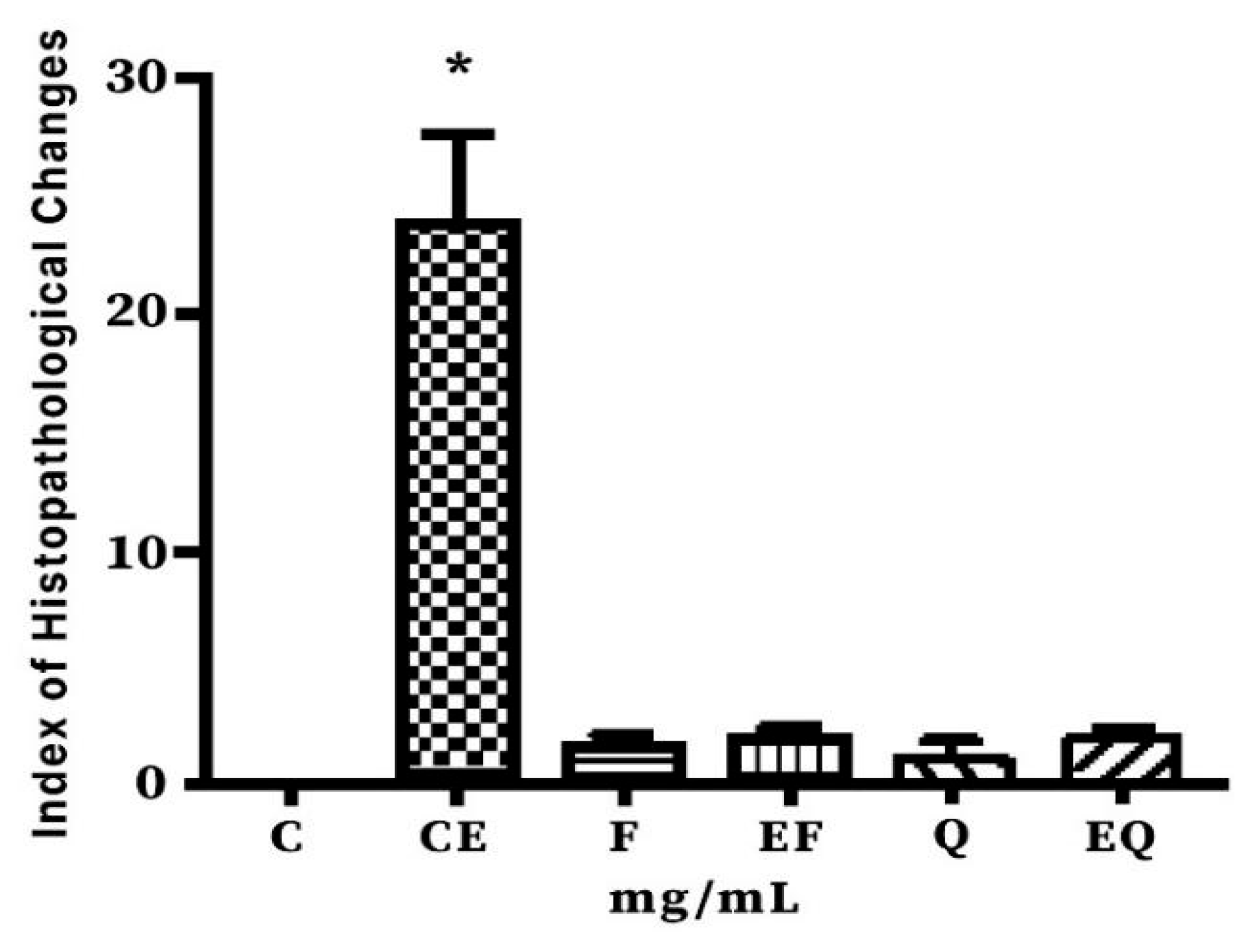

3.5. Histopathological Findings

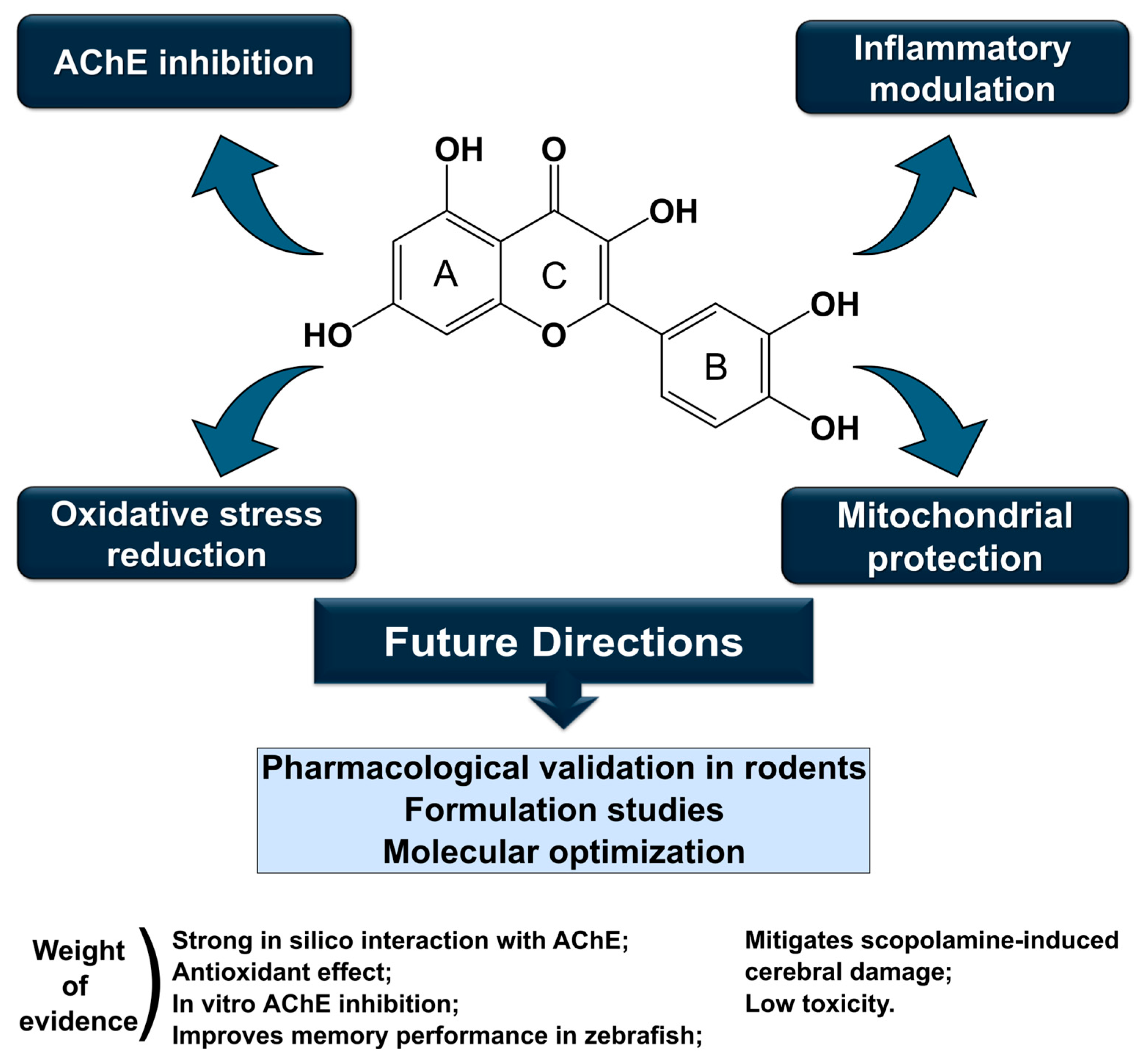

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| DPPH | Tests of antioxidant activity |

| ACHE | Acetylcholinesterase |

| Rg | Radius of gyration |

| iNOS | Nitric oxide synthase |

| NMDA | N-methyl D-aspartate |

| SASA | Solvent Access Surface Area |

| RMSD | Root Mean Square Deviation |

| RMSF | Root Mean Square Fluctuation |

| ATCI | Enzyme substrate acetylthiocholine iodide |

| DTNB | Colorimetric agent, 5,5′-dithiobis (2-nitrobenzoic) |

| TNB | Thionitrobenzoic acid |

| LD50 | Median lethal dose |

| Format SMILES | simplified molecular-input line-entry system |

| EDTA solution | ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid |

| HAI | Histopathologic Alteration Index |

References

- Monteiro, A.R.; Barbosa, D.J.; Remião, F.; Silva, R. Doença de Alzheimer: Insights e novas perspectivas em fisiopatologia da doença, biomarcadores e fármacos modificadores da doença. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2023, 211, 115522. [Google Scholar]

- Better, M.A. Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement 2023, 19, 1598–1695. [Google Scholar]

- Villa, C.; Stoccoro, A. Epigenetic Peripheral biomarkers for early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Genes 2022, 13, 1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, E.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.Z. Updates in Alzheimer’s disease: From basic research to diagnosis and therapies. Transl. Neurodegener. 2024, 13, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampel, H.; Mesulam, M.-M.; Cuello, A.C.; Farlow, M.R.; Giacobini, E.; Grossberg, G.T.; Khachaturian, A.S.; Vergallo, A.; Cavedo, E.; Snyder, P.J.; et al. The cholinergic system in the pathophysiology and treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 2018, 141, 1917–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheignon, C.; Tomas, M.; Bonnefont-Rousselot, D.; Faller, P.; Hureau, C.; Collin, F. Oxidative Stress and the Amyloid Beta Peptide in Alzheimer’s Disease. Redox Biol. 2018, 14, 450–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkina, N.A.; Khudoerkov, R.M.; Zobov, V.V.; Strel’tsov, S.A.; Moiseeva, A.A.; Glukhareva, T.V.; Larkina, M.S.; Samonina, G.E.; Zefirov, N.S.; Strobykina, I.Y. Novel Multitarget Agents Based on Tacrine Conjugates with 2-Aryl-Hydrazinylidene-1,3-Diketones as Potential Anti-Alzheimer’s Disease Agents. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twarowski, B.; Herbet, M. Inflammatory processes in alzheimer’s disease—Pathomechanism, diagnosis and treatment: A review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.-R.; Huang, J.-B.; Yang, S.-L.; Hong, F.-F. Role of cholinergic signaling in Alzheimer’s disease. Molecules 2022, 27, 1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balázs, N.; Bereczki, D.; Kovács, T. Cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine for the treatment of Alzheimer and non-Alzheimer dementias. Ideggyogy. Szle. 2021, 74, 379–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Athar, T.; Al Balushi, K.; Khan, S.A. Recent advances on drug development and emerging therapeutic agents for Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2021, 48, 5629–5645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Honig, L.S.; Sabbagh, M.N.; van Dyck, C.H.; Sperling, R.A.; Hersch, S.; Matta, A.; Giorgi, L.; Gee, M.; Kanekiyo, M.; Li, D.; et al. Lecanemab in early Alzheimer’s disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, J.R.; Zimmer, J.A.; Evans, C.D.; Lu, M.; Ardayfio, P.; Sparks, J.; Wessels, A.M.; Shcherbinin, S.; Wang, H.; Nery, E.S.; et al. Donanemab in early symptomatic Alzheimer disease: The TRAILBLAZER-ALZ 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2024, 331, 48–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knopman, D.S.; Jones, D.T.; Greicius, M.D. Failure to demonstrate efficacy of aducanumab: An analysis of the EMERGE and ENGAGE trials as reported by Biogen, December 2019. Alzheimer’s Dementia 2023, 19, 700–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurya, P.K. Health benefits of quercetin in age-related diseases. Molecules 2022, 27, 2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, N.; Bell, L.; Lamport, D.J.; Williams, C.M. Dietary flavonoids and human cognition: A meta-analysis. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2022, 66, e2100976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajad, M.; Kumar, R.; Thakur, S.C. História em Perspectiva: Os principais atores patológicos e o papel dos fitoquímicos na doença de Alzheimer. IBRO Neurosci. Rep. 2022, 12, 377–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, H.; Ullah, H.; Aschner, M.; Cheang, W.S.; Akkol, E.K. Neuroprotective effects of quercetin in Alzheimer’s disease. Biomolecules 2019, 10, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, F.N.; de Lima, H.B.; de Souza, L.R.; Oliveira, G.S.; de Paula da Silva, C.H.; Pereira, A.C.; da Silva Hage-Melim, L.I. Design of Multitarget Natural Products Analogs with Potential Anti-Alzheimer’s Activity. Curr. Comput.-Aided Drug Des. 2022, 18, 120–149. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.; Rauscher, S.; Nawrocki, G.; Ran, T.; Feig, M.; De Groot, B.L.; Grubmüller, H.; MacKerell, A.D. CHARMM36m: An improved force field for folded and intrinsically disordered proteins. Nat. Methods 2017, 14, 71–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanommeslaeghe, K.; MacKerell, A.D., Jr. Automation of the CHARMM General Force Field (CGenFF) I: Bond perception and atom typing. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2012, 52, 3144–3154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brand-Williams, W.; Cuvelier, M.E.; Berset, C. Use of a free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 1995, 28, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, C.M.; Silva, H.R.; Vieira, G.M., Jr.; Ayres, M.C.; Costa, C.L.; Araújo, D.S.; Cavalcante, L.C.; Barros, E.D.; Araújo, P.B.; Brandão, M.S.; et al. Total phenols and antioxidant activity of five medicinal plants. Quim. Nova 2007, 30, 351–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, I.K.; van de Meent, M.; Ingkaninan, K.; Verpoorte, R. Screening for acetylcholinesterase inhibitors from Amaryllidaceae using silica gel thin-layer chromatography in combination with bioactivity staining. J. Chromatogr. A 2001, 915, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drwal, M.N.; Banerjee, P.; Dunkel, M.; Wettig, M.R.; Preissner, R. ProTox: A web server for the in silico prediction of rodent oral toxicity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, W53–W58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, P.; Dehnbostel, F.O.; Preissner, R. Prediction Is a Balancing Act: Importance of Sampling Methods to Balance Sensitivity and Specificity of Predictive Models Based on Imbalanced Chemical Data Sets. Front. Chem. 2018, 6, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, P.; Eckert, A.O.; Schrey, A.K.; Preissner, R. ProTox-II: A webserver for the prediction of toxicity of chemicals. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, W257–W263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, P.; Kemmler, E.; Dunkel, M.; Preissner, R. ProTox 3.0: A webserver for the prediction of toxicity of chemicals. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, W513–W520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherkasov, A.; Muratov, E.N.; Fourches, D.; Varnek, A.; Baskin, I.I.; Cronin, M.; Dearden, J.; Gramatica, P.; Martin, Y.C.; Todeschini, R.; et al. QSAR modeling: Where have you been? Where are you going to? J. Med. Chem. 2013, 57, 4977–5010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tropsha, A. Best practices for QSAR model development, validation, and exploitation. Mol. Inform. 2010, 29, 476–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekins, S. The role of computational toxicology in drug discovery and development. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2019, 18, 305–321. [Google Scholar]

- Percie du Sert, N.; Hurst, V.; Ahluwalia, A.; Alam, S.; Avey, M.T.; Baker, M.; Browne, W.J.; Clark, A.; Cuthill, I.C.; Dirnagl, U. The ARRIVE guidelines 2.0: Updated guidelines for reporting animal research. PLoS Biol. 2020, 18, e3000410. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.-H.; Lee, Y.; Kim, D.; Jung, M.W.; Lee, C.-J. Scopolamine-induced learning impairment reversed by physostigmine in zebrafish. Neurosci. Res. 2010, 67, 156–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melo, N.C. Estudos Químicos e Farmacológicos das Atividades Antidepressiva, Ansiolítica e de Toxicidade Aguda do Extrato Hidroetanólico das Folhas de Aloysia polystachya (Griseb.) Moldenke em Modelo de Danio rerio (Hamilton, 1822). Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade Federal do Amapá, Macapá, Brazil, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Poleksic, V.; Mitrovic-Tutundzic, V. Fish gills as a monitor of sublethal and chronic e effects of pollution. In Sublethal and Chronic Effects of Pollutants on Freshwater Fish; Müller, R., Lloyd, R., Eds.; Fishing New Books ltd. Farnham: Oxford, UK, 1994; pp. 339–352. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, W.; Ma, X.; Yang, H.; Luan, Y.; Ai, H. Molecular engineering and activity improvement of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors: Insights from 3D-QSAR, docking, and molecular dynamics simulation studies. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2022, 116, 108239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boulaamane, Y.; Kandpal, P.; Chandra, A.; Britel, M.R.; Maurady, A. Chemical library design, QSAR modeling and molecular dynamics simulations of naturally occurring coumarins as dual inhibitors of MAO-B and AChE. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2023, 42, 1629–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kua, J.; Zhang, Y.; McCammon, J.A. Studying Enzyme Binding Specificity in Acetylcholinesterase Using a Combined Molecular Dynamics and Multiple Docking Approach. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 8260–8267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Sun, Y.; Lu, X.; Yang, F.; Li, T.; Deng, C.; Song, J.; Huang, X. Assessment of the anti-inflammatory mechanism of quercetin 3,7-dirhamnoside using an integrated pharmacology strategy. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2023, 102, 1534–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boumezber, S.; Yelekçi, K. Screening of novel and selective inhibitors for neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) via structure-based drug design techniques. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2022, 41, 3607–3629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Raman, C.S.; Glaser, C.B.; Blasko, E.; Young, T.A.; Parkinson, J.F.; Whitlow, M.; Poulos, T.L. Crystal Structures of Zinc-free and -bound Heme Domain of Human Inducible Nitric-oxide Synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 21276–21284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isika, D.K.; Sadik, O.A. Selective Structural Derivatization of Flavonoid Acetamides Significantly Impacts Their Bioavailability and Antioxidant Properties. Molecules 2022, 27, 8133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Yang, W.; Chen, X.; Xiao, J. Inhibition of flavonoids on acetylcholine esterase: Binding and structure-activity relationship. Food Funct. 2014, 5, 2582–2589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Mai, X.; Wu, X.; Hu, X.; Luo, X.; Zhang, G. Exploring the Inhibition of Quercetin on Acetylcholinesterase by Multispectroscopic and In Silico Approaches and Evaluation of Its Neuroprotective Effects on PC12 Cells. Molecules 2022, 27, 7971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou Samra, M.; Chedea, V.S.; EconomouAbou Samra, M.; Chedea, V.S.; Economou, A.; Calokerinos, A.; Kefalas, P. Antioxidant/prooxidant properties of model phenolic compounds: Part I. Studies on equimolar mixtures by chemiluminescence and cyclic voltammetry. Food Chem. 2011, 125, 622–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, C.; Liu, X.; Chang, Y.; Wang, R.; Lv, T.; Cui, C.; Liu, M. Investigation of the anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities of luteolin, kaempferol, apigenin and quercetin. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2021, 137, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, M.; Ebrahimie, E.; Lardelli, M. Using the zebrafish model for Alzheimer’s disease research. Front. Genet. 2014, 5, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.N.; Yeong, K.Y. Scopolamine, a Toxin-Induced Experimental Model, Used for Research in Alzheimer’s Disease. CNS Neurol. Disord.-Drug Targets 2020, 19, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucida, H.; Primadini, Y. A Study on the Acute Toxicity of Quercetin Solid Dispersion as a Potential Neph-ron-Protector. Rasayan J. Chem. 2019, 12, 727–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harishkumar, R.; Reddy, L.P.K.; Karadkar, S.H.; Al Murad, M.; Karthik, S.S.; Manigandan, S.; Selvaraj, C.I.; Christopher, J.G. Toxicity and selective biochemical assessment of quercetin, gallic acid, and curcumin in zebrafish. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2019, 42, 1969–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aly, A.M. Assessment The Functional Properties of Different Parts of Graviola and Its Application in A Bakery Product. Egypt. J. Chem. 2023, 66, 581–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.; Lee, C.-J.; Choi, J.; Hwang, J.; Lee, Y. Anxiolytic effects of an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, physostigmine, in the adult zebrafish. Anim. Cells Syst. 2012, 16, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richetti, S.; Blank, M.; Capiotti, K.; Piato, A.; Bogo, M.; Vianna, M.; Bonan, C. Quercetin and rutin prevent scopolamine-induced memory impairment in zebrafish. Behav. Brain Res. 2011, 217, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tongjaroenbuangam, W.; Ruksee, N.; Chantiratikul, P.; Pakdeenarong, N.; Kongbuntad, W.; Govitrapong, P. Neuroprotective effects of quercetin, rutin and okra (Abelmoschus esculentus Linn.) in dexamethasone-treated mice. Neurochem. Int. 2011, 59, 677–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, J.; Xie, J.; Yang, L.; Xing, Y.; Li, Z. The effects of quercetin on immunity, antioxidant indices, and disease resistance in zebrafish (Danio rerio). Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 46, 759–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, R.J.; Ellis, A.E. The anatomy and physiology of teleosts. In Fish Pathology, 3rd ed.; Roberts, R.J., Ed.; W. B. Saunders: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2012; pp. 12–54. [Google Scholar]

- Baatrup, E. Structural and functional effects of heavy metals on the nervous system, including sense organs, of fish. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Comp. Pharmacol. 1991, 100, 253–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaleem, M.A.; Al-Kuraishy, H.M.; Al-Gareeb, A.I.; Albuhadily, A.K.; Alrouji, M.; Yassen, A.S.A.; Alexiou, A.; Papadakis, M.; Batiha, G.E.-S. Molecular Signaling Pathways of Quercetin in Alzheimer’s Disease: A Promising Arena. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2024, 45, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adnan, M.; Siddiqui, A.J.; Bardakci, F.; Surti, M.; Badraoui, R.; Patel, M. Neuroprotective potential of quercetin in Alzheimer’s disease: Targeting oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and amyloid-β aggregation. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1593264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.-W.; Chen, J.-Y.; Ouyang, D.; Lu, J.-H. Quercetin in animal models of Alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review of preclinical studies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safarzadeh, E.; Ataei, S.; Akbari, M.; Abolhasani, R.; Baziar, M.; Asghariazar, V.; Dadkhah, M. Quercetin ameliorates cognitive deficit, expression of amyloid precursor gene, and pro-inflammatory cytokines in an experimental models of Alzheimer’s disease in Wistar rats. Exp. Gerontol. 2024, 193, 112466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishihira, J.; Nishimura, M.; Kurimoto, M.; Kagami-Katsuyama, H.; Hattori, H.; Nakagawa, T.; Muro, T.; Kobori, M. The effect of 24-week continuous intake of quercetin-rich onion on age-related cognitive decline in healthy elderly people: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group comparative clinical trial. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 2021, 69, 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishimura, M.; Ohkawara, T.; Nakagawa, T.; Muro, T.; Sato, Y.; Satoh, H.; Kobori, M.; Nishihira, J. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study evaluating the effects of quercetin-rich onion on cognitive function in elderly subjects. Funct. Foods Health Dis. 2017, 7, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, G.; Hong, M.; Lee, J.; Lee, H.J.; Ji, Y.; Kang, J.; Baik, M.-H.; Lim, M.H. Structure–activity relationships and accelerated molecular dynamics reveal key catechol interactions of flavones/flavonols with acetylcholinesterase. Chem. Sci. R. Soc. Chem. 2020, 11, 10243–10254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.J.; Cheang, L.C.; Wang, M.W.; Lee, S.M. Quercetin exerts a neuroprotective effect through inhibition of the iNOS/NO system and pro-inflammation gene expression in PC12 cells and in zebrafish. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2010, 27, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Zhao, X.; Ma, Y.; Zhai, G.; Li, L.; Lou, H.; Gao, Y. Enhancement of Oral Bioavailability of Quercetin by Metabolic Inhibitory Nanosuspensions Compared to Conventional Nanosuspensions. Drug Deliv. 2021, 28, 1226–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Restrepo, F.; Sabogal-Guáqueta, A.M.; Cardona-Gómez, G.P. Quercetin ameliorates Alzheimer’s disease pathology and protects cognitive and emotional function in aged triple transgenic Alzheimer’s disease model mice. Neuropharmacology 2015, 93, 134–145. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, L.G.; Garrick, J.M.; Roquè, P.J.; Pellacani, C.; Pizzol, F.D. Mechanisms of neuroprotection by quercetin: Counteracting oxidative stress and more. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2016, 2016, 2986796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peluzio, M.D.C.G.; Martinez, J.A.; Milagro, F.I. The biological activities, chemical stability, metabolism and delivery systems of quercetin: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 56, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Souza, F.N.; Oliveira, N.K.S.; de Lima, H.B.; Silva, A.G.; Cruz, R.A.S.; Oliveira, F.R.; Federico, L.B.; Hage-Melim, L.I.S. Therapeutic Potential of Quercetin in the Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease: In Silico, In Vitro and In Vivo Approach. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 10340. https://doi.org/10.3390/app151910340

Souza FN, Oliveira NKS, de Lima HB, Silva AG, Cruz RAS, Oliveira FR, Federico LB, Hage-Melim LIS. Therapeutic Potential of Quercetin in the Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease: In Silico, In Vitro and In Vivo Approach. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(19):10340. https://doi.org/10.3390/app151910340

Chicago/Turabian StyleSouza, Franciane N., Nayana K. S. Oliveira, Henrique B. de Lima, Abraão G. Silva, Rodrigo A. S. Cruz, Fabio R. Oliveira, Leonardo B. Federico, and Lorane I. S. Hage-Melim. 2025. "Therapeutic Potential of Quercetin in the Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease: In Silico, In Vitro and In Vivo Approach" Applied Sciences 15, no. 19: 10340. https://doi.org/10.3390/app151910340

APA StyleSouza, F. N., Oliveira, N. K. S., de Lima, H. B., Silva, A. G., Cruz, R. A. S., Oliveira, F. R., Federico, L. B., & Hage-Melim, L. I. S. (2025). Therapeutic Potential of Quercetin in the Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease: In Silico, In Vitro and In Vivo Approach. Applied Sciences, 15(19), 10340. https://doi.org/10.3390/app151910340