1. Introduction

Sulfur hexafluoride (SF

6) is widely used as an insulating material and arc-quenching medium in gas-insulated switchgear (GIS) and high-voltage circuit breakers (CBs) because of its high dielectric strength and excellent heat-transfer capability [

1]. Although SF

6 has excellent insulating properties, it is also a powerful greenhouse gas with a high global-warming potential. Significant efforts have been made to reduce SF

6 emissions by introducing state-of-the-art SF

6-handling techniques [

2]. In parallel, the quest for SF

6 alternatives has been ongoing for more than two decades. SF

6 alternatives should have minimal or no global-warming potential, high dielectric strength, good arc-quenching capabilities, and chemical stability to meet the insulating-medium requirements of gas-insulated equipment. Possible candidates that have the above-mentioned characteristics have been narrowed down to buffer gases such as N

2, air, CO

2, rare gases, and their mixtures.

Nitrogen (N

2) is an inert and easily available gas and is considered one of the most important additives to SF

6. A small amount of SF

6 added to N

2 can increase the overall breakdown strength. The SF

6/N

2 mixture as a replacement for SF

6 has been more widely adopted in practical applications [

3]. However, in non-uniform fields, SF

6/CO

2 has higher dielectric strength and better insulation characteristics than SF

6/N

2, especially in gas-insulated transformers (GITs) because of gas/film insulation [

4]. CO

2 has attracted attention as a promising substitute for SF

6 in high-voltage circuit breakers because it has acceptable insulation and interrupting properties [

5,

6,

7]. CO

2 is also an important component of fluoronitriles/CO

2 gas mixtures and is a promising alternative to SF

6 in medium- and high-voltage switchgear [

8,

9].

Surface roughness or particle contamination generates high-field zones in gas-insulated switchgear. SF

6 is susceptible to these high-field zones, and breakdown may occur. For reliable and continuous GIS operation, it is necessary to investigate non-uniform field breakdown in SF

6 and its mixtures [

10]. A considerable amount of work has been carried out on the pre-breakdown and breakdown characteristics of SF

6 and its mixtures in uniform and non-uniform field conditions under different applied conditions [

11]. At low pressure and for small gaps (≤0.3 cm), breakdown in gaseous dielectric media occurs via streamers. Streamers are important, and their initiation, branching, and propagation play crucial roles in the breakdown process [

12].

Both experimental and numerical simulation approaches have been adopted to understand the dynamics of streamer discharge, but experimental approaches have some limitations in studying the microscopic characteristics of streamer discharge. Simulation is the best solution for understanding the physical mechanism responsible for the initiation, propagation, and branching of streamer discharge based on electron-beam data. Due to the stochastic nature of streamer discharge, 3D simulations may be needed. Generally, two kinds of simulation techniques are adopted for streamer discharge investigation: (1) fluid schemes and (2) particle schemes, or their combinations. Each approach is used to clarify the discharge mechanisms in SF

6 and its mixtures. Both 1D and 2D fluid models for streamer discharge in SF

6 in uniform and non-uniform field conditions with different applied conditions have been used to examine electrons and electric-field distribution [

13,

14]. The particle simulation technique was adopted to model positive and negative streamer discharge in SF

6 [

15]. A 3D particle-in-cell model was used to study streamer formation in electronegative gases under uniform field conditions [

16]. In [

17], a particle model with a 3D Poisson solver was built to study the avalanche-to-streamer transition in arbitrary gases. Streamer discharge development in an SF

6/N

2 mixture was studied using 1D and 2D axially symmetric fluid models [

18,

19]. The branching phenomenon of negative streamers in CO

2 at atmospheric pressure was studied using fluid and particle models without considering any discharge initiation mechanism [

20].

The generation of free electrons is a prerequisite for streamer discharge initiation. Different mechanisms, such as photoionization, detachment of electrons from negative ions, hole emission, Auger release of free electrons, field emission, and field ionization, depend on the medium state, applied voltage, and electric-field distribution [

21]. For positive-polarity voltages, detachment of electrons from negative ions and photoionization are usually considered the primary free-charge generation mechanisms in SF

6 and its mixtures [

22]. In the case of electron detachment from negative ions, the source and density of negative ions are unknown for dc voltages [

22]. Photoionization has been implemented in previous simulation models as a source of free electrons ahead of positive streamer discharge, and many assumptions were made because no data is available for absorption coefficients, photon absorption lengths, and recombination coefficients for SF

6, CO

2, and pure N

2. It is therefore necessary to investigate other charge-generation mechanisms in such gases.

In this work, the initiation, branching, and propagation of streamer discharge in SF6 and its mixtures with N2 and CO2 are investigated using a 3D particle-in-cell Monte Carlo collision model. Field ionization is included as an electron-generation process, and the rate of field ionization is calculated using Zener’s model. The effects of voltage, pressure, and different mixing ratios on streamer discharge characteristics are observed. A needle-to-plane electrode configuration is adopted because of its relevance to protrusion defects in gas-insulated equipment. The electric-field and potential distributions at different times are also presented.

2. Three-Dimensional PIC/MCC Simulation Model with Field Ionization

Streamer discharge has a stochastic nature; therefore, a 3D simulation model is needed. Particle models with Monte Carlo collision techniques have been extensively used in the field of plasma physics, as they provide detailed information on the discharge process. In this work, a 3D particle-in-cell Monte Carlo collision model (PIC/MCC) is used. The model has been used before to study inception, branching, and propagation in air and N

2/O

2 under uniform and non-uniform fields for positive- and negative-polarity streamers [

23,

24,

25,

26]. A detailed description of the 3D model is available elsewhere, and the source code is available online [

26,

27]. Here, we briefly describe the model. In the model, electrons added as particles collide with background neutral molecules. Ions are added as immobile densities due to the short time scale of the discharge. The 3D model works under electrostatic conditions, and the effect of an external magnetic field is not considered. Two different schemes, velocity Verlet and leapfrog, are presented and compared for updating the velocity and position of particles. Both schemes are quite similar, except for differences in the calculation of the velocity and position of particles. The velocity Verlet scheme is used in the model, in which the position and velocity of particles are calculated at the same time, whereas in the leapfrog method, velocity and position are calculated with a time offset [

25].

Particle models include a large number of particles, each of which is tracked individually. Superparticles are used to represent such a large number of particles. The weight of superparticles can induce fluctuations, which cause numerical errors. To adjust the weights of superparticles, an adaptive particle management scheme is used in the model. In this technique, the number of particles defined in a cell is given a desired weight according to

Here,

is the desired number of particles,

is the desired weight,

is the particle number density of type

s in cell

i, and

is the volume of a grid cell. Particles weighing

merge, and particles weighing

split from neighboring particles. The new merged particles obtain their velocity from one of the merging particles, their average position, and a new weight that is equal to the sum of the merging particles. The splitting particles possess the same position and velocity as the original particle, but their weight becomes half that of the original particle [

25,

28]. Particle models take electron–neutral collisional cross-sections as input. Because of the low ionization degree in weakly ionized discharges, only electron–neutral collisions are considered, and electron–electron and electron–ion collisions are neglected in the model [

26]. The cross-sections of SF

6, N

2, and CO

2 used in the present model are available on Lxcat [

29]. The null-collision technique was implemented to model the collision process. The implementation of null-collision methods can be found in [

26,

30]. The electric field in electrostatic conditions is given by

is the electric potential and can be obtained using Poisson’s equation.

Here,

is the charge density. A nested-grid type of adaptive mesh refinement scheme is used in the model to avoid stochastic errors and to resolve space-charge layers with fine resolution [

31]. A 3D view and a schematic view of the computational domain used in the present model are shown in

Figure 1. The size of the computational domain is (0.5mm)

3. In the 3D model, the electrode is represented by generating multiple points on its surface, spaced at a specified distance (2 µm). The points on the surface of the electrode are closely spaced near the tip of the electrode, and the distance between the points increases away from the electrode tip to reduce computational cost. An iteration procedure is performed to update the charges on these points in order to obtain the closest value to the applied potential

V0 [

26]. The needle electrode consists of a cylindrical part (r

cylinder = 250 µm) that ends in a cone (h

cone = 500 µm) with a spherical-shaped tip (10 µm).

A positive voltage is applied to the needle electrode, which is positioned at the center of the domain, while all sides of the domain are kept at zero potential. In the experiments, the bottom of the electrode is insulated within the electrical discharge chamber to prevent the formation of strong electric fields in that area. In the present 3D model, the implementation of dielectric insulation between the electrode and the bottom of the computational domain is not possible. However, grid refinement is not allowed to avoid discharges occurring in the bottom area of the simulation domain. The 3D code is parallelized using the message-passing interface (MPI) to further reduce computation time [

26].

(a) Field Ionization

Free-electron generation is a prerequisite for positive discharge initiation and growth. The generated electrons move toward the anode and form electron avalanches, which further transform into a streamer discharge if the streamer criterion is fulfilled. Field ionization, a direct ionization mechanism, is investigated in SF

6 and its mixtures with N

2 and CO

2 as a primary source of ionization. Collisional detachment of electrons from negative ions has been proposed as a charge-generating mechanism in SF

6. However, in the dc voltage case, the source and density of negative ions are still questionable. Moreover, collisional detachment cross-section data for SF

6 is limited and suggests that if

E/

N is not sufficiently high, the negative ions will not gain enough kinetic energy between collisions for detachment to occur, and the discharge initiation probability will be negligible [

22]. If the electric field is high enough in the range of MV/cm, i.e., in the case of sharper needle electrodes, field-induced charge generation could be possible [

32].

In the presence of high electric fields, electrons are elevated from the valence band to the conduction band in a neutral molecule, thus generating a free electron and a positive ion, as shown in

Figure 2. Field ionization has been proposed for pressurized dielectric media. It has been experimentally validated as a free-charge carrier-generating process in liquids, transformer oil, and supercritical media [

33,

34,

35,

36]. The rate of field ionization is calculated using Zener’s model, first proposed for breakdown in solid dielectrics [

37]. The charge density source term in Zener’s model was improved by density functional theory (DFT) and was implemented in transformer oil [

35]. The electric-field-dependent charge generation term

in Zener’s model is given by

Here,

is the applied electric field,

q is the electronic charge,

n0 is the ionizable density of impurity molecules,

m is the effective mass of the electron,

a is the separation distance between the molecules,

h is Planck’s constant, and

is the ionization potential. Due to a lack of comprehensive knowledge about gaseous-state theory, it is challenging to find the appropriate values of Zener’s parameters. The Zener parameters are appropriately selected by making some assumptions to make it work in SF

6 and its mixtures, as given in

Table 1. As shown in Equation (6), the generation term

is mainly affected by the ionization potential, ionizable density, separation distance between the molecules, and electric field. The source of free electrons is impurity molecules, of which a small amount with low ionization potential is added. These impurity molecules are ionized because of field ionization, and electrons and positive ions are generated from them.

It is important to note that field ionization is not a universally dominant mechanism in gaseous dielectrics but is most valid under specific conditions. In particular, it becomes relevant in highly non-uniform electric fields near sharp electrode tips, where the local field strength can reach several MV/cm. Under such conditions, neutral or impurity molecules may undergo field-assisted ionization, generating the initial electrons required for avalanche development. In contrast, at lower pressures or in quasi-uniform field configurations, processes such as photoionization and electron detachment from negative ions are generally considered to play a more significant role in sustaining positive streamer propagation. Therefore, in this work, field ionization is used primarily to investigate discharge initiation in strongly stressed, non-uniform fields, while acknowledging that its applicability is limited for uniform fields and reduced field strengths.

(b) Physical Mechanisms of Electrical Breakdown based on Field Ionization

The breakdown in compressed gases involves a series of physical processes, such as the generation of initial electrons, electron avalanche formation, transition into a streamer, streamer-to-leader transition, and stepped leader propagation across the gap. For smaller gaps (

Pd < 1 cm), breakdown occurs via streamers. A streamer is an important and decisive element in predicting the breakdown characteristics of any dielectric medium. The concept of field ionization is implemented to generate free electrons from low-density and low-ionization-potential impurity molecules in SF

6 and its mixture with N

2 and CO

2. In the case of a needle-to-plane electrode geometry, the electric field must be high enough at the needle electrode tip, typically 10

6–10

7 V/m, to trigger field ionization. As mentioned earlier, field ionization results in the generation of electrons and positive ions from neutral molecules. The mobility of electrons is five times higher than that of positive ions. Electrons quickly move toward the anode, creating electron avalanches and leaving a bunch of positive ions behind. Electrons reaching the anode are absorbed and removed from the computational domain. The asymmetry in electron and positive ion mobilities leads to the formation of space charge in a short time. The left-behind positive charges form a zone (zone 1) in front of the needle anode, where the sum of the net space charge and background field modifies the total field, as shown in

Figure 3. In the modified zone (zone 2), enhanced electric fields cause ionization of more molecules away from the needle electrode, which results in the formation of another zone, i.e., zone 3, with an enhanced electric field. The process continues, and a field wave propagates from the needle electrode across the gap over time.

3. Results and Discussion

The generation of free electrons is a prerequisite for positive streamer discharge inception and propagation. In this work, field ionization is investigated as a source of primary ionization in different gas mixtures. The 3D PIC/MCC simulation results of SF

6/N

2 and SF

6/CO

2 at atmospheric pressure in a 1 mm needle-to-plane gap for an anode potential of 4 kV are presented in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5. The curvature radius of the needle electrode tip was selected to be small, i.e., 10 µm, in order to generate the prerequisite field strength for field ionization in the vicinity of the needle tip. A 4 kV dc voltage was supplied to the needle electrode instantaneously. Initially, there were no free electrons in the computational domain, and discharge started from a seed containing 10

4 electron–ion pairs.

(a) Streamer initiation at different mixing ratios of SF6/N2

The SF

6/N

2 mixture is widely used in gas-insulated lines (GILs). A low percentage of SF6 (10–20%) added to N2 improves insulation properties and reduces costs.

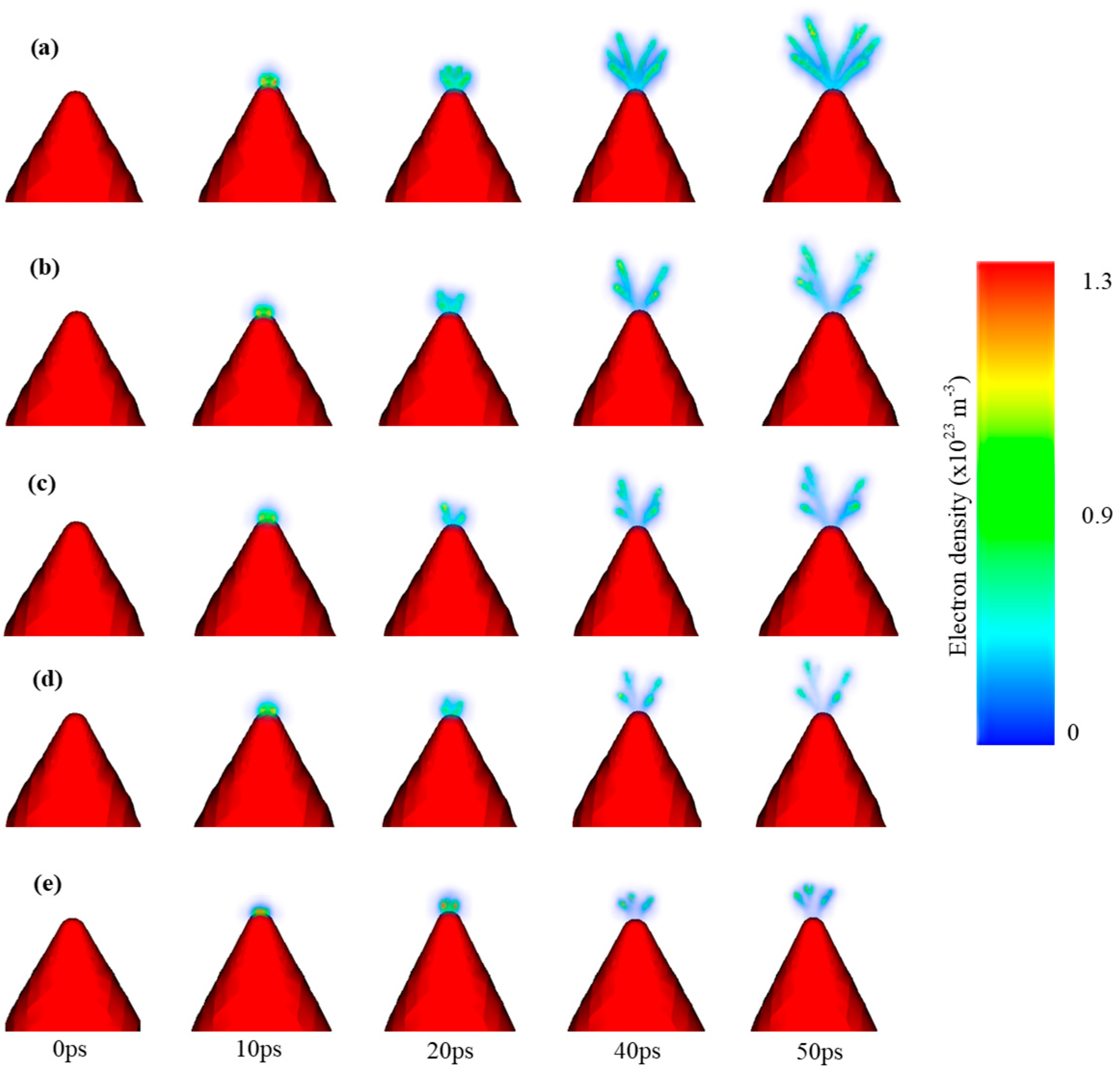

Figure 4 shows the simulation results of positive needle-to-plane streamer discharges in pure N

2, 10% SF

6-90% N

2, 20% SF

6-80% N

2, 50% SF

6-50% N

2, and pure SF

6 for a 4 kV voltage supplied to the needle electrode at atmospheric pressure. The discharge was observed until 50 ps. A filamentary-shaped streamer discharge appeared at the needle tip independent of the gas-mixing ratio. Up to 10 ps, a spherical-shaped inception cloud was formed, covering a small fraction of the needle tip, which further deformed into four main streamer channels by 20 ps. The size of the streamer head increased, and a flattened shape was observed just before the secondary branching. The main streamer channels evolving from the inception cloud further expanded into the gap with small, irregular streamer branches of shorter length. The small branches on the main streamer channel showed regular behavior across all gas-mixing ratios, and the length of the small branches increased with increasing SF

6 content. In pure N

2 and the N

2/SF

6 mixtures, deflection among the four main streamers was noticeable, while in pure SF

6, the discharge channels were more confined. The apparent luminosity of the discharge decreased with the increase in SF

6. With the increased content of SF

6 in the SF

6/N

2 mixture, the electron density in the streamer discharge decreased. The addition of SF

6 decreased the apparent length and increased the diameter of the streamers. Interestingly, the addition of SF

6 to N

2 did not have any effect on the initiation of the discharge, which might be due to the initial parameters used in the Zener model. The general morphology of the streamer discharge was quite similar across all gas-mixing ratios. A comparison of the simulation results with other simulation and experimental results is difficult due to incompatible gap sizes and electrode parameters.

The electric-field distribution for different gas-mixing ratios at different times is presented in

Figure 5. When a positive voltage was supplied to the needle electrode, a strong electric field was created near the electrode tip. In the presence of this high electric field, free electrons were liberated from impurity molecules and traveled toward the anode, forming an avalanche. While traveling toward the anode, these electrons collided with neutral molecules, and ionization occurred. Electrons reaching the anode were absorbed and removed from the domain, leaving a bunch of slow positive ions behind them. Due to the accumulation of positive ions, the electric field decreased near the anode and increased farther away, creating a new high-field zone away from the anode, as shown in

Figure 5. In this new high-field zone, new free electrons were generated, which further took part in ionization, and the process continued. With the propagation of the streamer discharge, the electric field at the head of the streamer channels decreased. On the main streamer channels, there were small electric-field-enhanced zones, causing the formation of small branches. These small branches on the main streamer channels remained for a short time and then quenched. The distribution of the electric field was shown until 50 ps. With increasing SF

6 content, the electric field decreased at the head of the main streamer channel.

(b) Streamer initiation at different mixing ratios of SF6/CO2

SF

6/N

2 is widely applied as an arc-quenching medium in GILs. CO

2 and CO

2-based gas mixtures are the best candidates to replace SF

6 due to their high-voltage switching and insulation properties. Among these, SF

6/CO

2 has been identified as a suitable substitute for SF

6 in gas-insulated transformers (GITs), where non-uniform fields exist. The breakdown strength of SF

6/CO

2 (20%/80%) mixtures can be higher than that of pure SF

6 due to the corona stabilization effect under highly non-uniform field conditions present in GITs [

4]. The 3D PIC/MCC simulation results for SF

6/CO

2 gas mixtures at different mixing ratios are presented in

Figure 6 Three stages of streamer discharge were observed. At 0 ps, there were no free electrons in the computational domain, and no discharge occurred. Discharge was initiated from a seed placed at the needle tip. When a positive dc voltage was supplied to the needle electrode, a high electric field was generated near the needle electrode tip. Because of field ionization, free electrons were liberated from impurity molecules. Due to their high mobility, free electrons traveled toward the anode, forming electron avalanches, while positive ions were left behind. From 0 ps to 10 ps, the first stage of the streamer discharge, i.e., inception, a cloud appeared at the needle tip. Over time, the inception cloud deformed into the main streamer channels, i.e., the second stage of streamer discharge. Secondary branches appeared on both sides of the main streamer channels and propagated at the same speed into the gap. The length of the secondary branches on the main channels decreased with increasing SF

6 content. With the addition of SF

6, the apparent length of the overall streamer discharge decreased. Two-dimensional slices of the electric-field distribution at the needle tip along the streamer propagation for different gas-mixing ratios are presented in

Figure 7. The electric field first increased when 10% SF

6 was added to pure CO

2 and then decreased with further increases in SF

6 content. With increasing SF

6, the electric-field distribution turned into a ring shape around the main streamer channels. The main channels were more confined to each other in pure SF

6.

To further validate the simulation results, we qualitatively compared our findings with previously reported experimental studies on SF

6-based mixtures. Experimental investigations in needle–plane geometries have consistently shown that increasing the proportion of SF

6 reduces the apparent length of streamers and suppresses branching due to its strong electron-attachment properties [

4,

10,

11]. Similarly, Chalmers et al. [

10] and Malik and Qureshi [

11] reported that higher gas pressure significantly increases breakdown strength, thereby shortening the discharge channels, which aligns with our simulation results at 5 bar. Moreover, studies on CO

2 and SF

6/CO

2 mixtures [

12,

20] have shown more pronounced branching compared to SF6/N2, which agrees with the higher electron density and longer branches observed in our simulations for SF

6/CO

2. Although a quantitative comparison is challenging because of differences in geometry, voltage waveforms, and electrode gap distances, the qualitative agreement between the simulated streamer characteristics and the experimental trends increases confidence in the physical validity of the proposed model.

The findings of this study have direct relevance for the design and operation of high-voltage equipment. In gas-insulated switchgear (GIS) and circuit breakers (CBs), where compact geometries and non-uniform fields are common, the reduced streamer length and branching observed with increasing SF6 content explain why even small additions of SF6 to buffer gases such as N2 or CO2 can significantly improve insulation reliability. The stronger branching and higher electron densities observed in SF6/CO2 mixtures indicate that this mixture may be less favorable for applications where streamer suppression is critical, but it may still provide advantages in highly non-uniform field environments such as gas-insulated transformers (GITs), where corona stabilization effects are beneficial. These insights support the current industrial preference for SF6/N2 in GIS while highlighting specific scenarios where SF6/CO2 could be a viable alternative. Thus, the simulation results not only help clarify the fundamental discharge mechanisms but also provide guidance for selecting appropriate gas mixtures in eco-friendly high-voltage equipment.

(c) Influence of Pressure

The influence of pressure on the discharge evolution at the same voltage for different gas-mixing ratios of SF

6/N

2 and SF

6/CO

2 is presented in

Figure 8 and

Figure 9. Dielectric strength generally increased with the increase in pressure. The addition of SF6 resulted in further increases in the breakdown strength. The apparent discharge length and the number of streamer branches decreased considerably with the increase in pressure. The electron density in SF

6/CO

2 mixtures was higher than in SF

6/N

2 mixtures. In both SF

6/N

2 and SF

6/CO

2, increasing the SF

6 content decreased the discharge length and electron density.