Shared Product Architectures for Engineering-to-Order Buyers and Suppliers: Insights from a Case Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

- Does the described product architecture comprise a system decomposition that is mutually shared across the supplier and buyer?

- Does the described architecture comprise modules and interfaces that are financially driven by interorganisational alignment of key design characteristics?

- Does the architecture in question describe and financially quantify how a series of coordinated activities are consistent and mutually beneficial for both organisations?

2.1. Modular Product Architectures

2.2. Literature Discussion

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Case Context

3.2. Data Collection and Analysis

3.3. Use of Generative AI

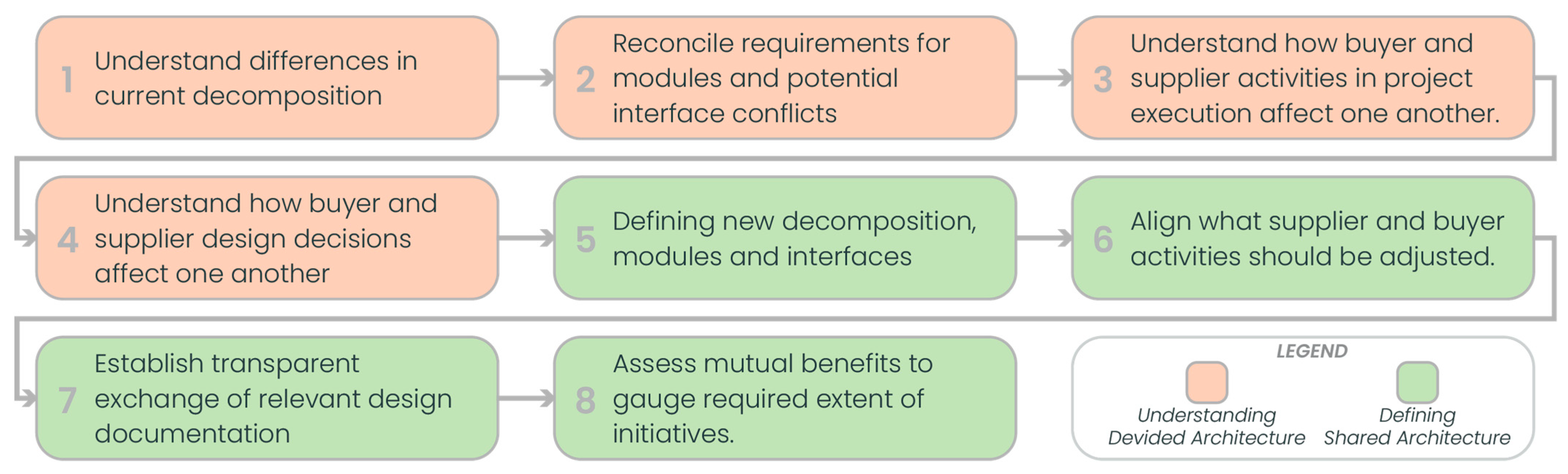

4. Proposed Framework

4.1. Foundational Theory for the Framework

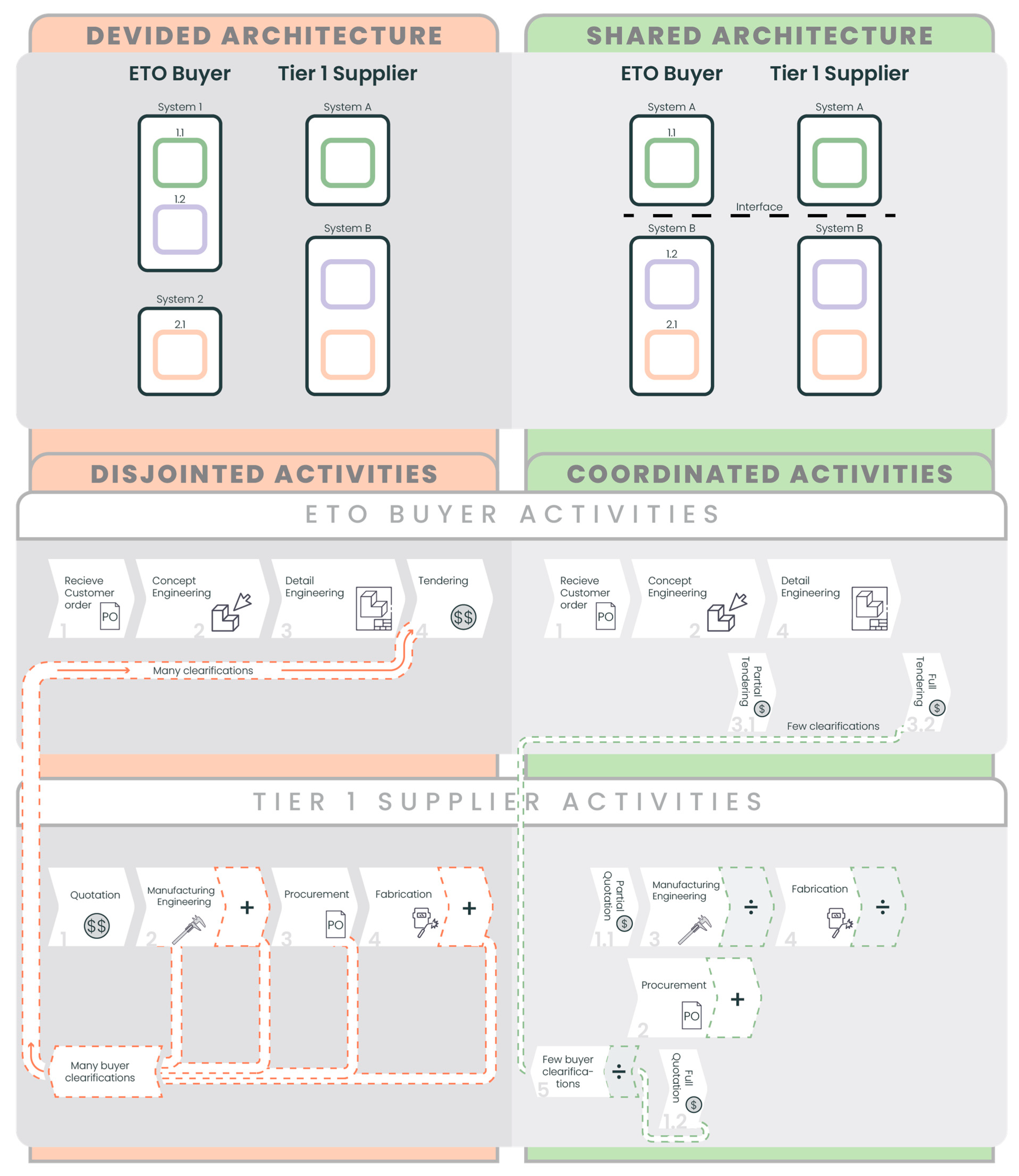

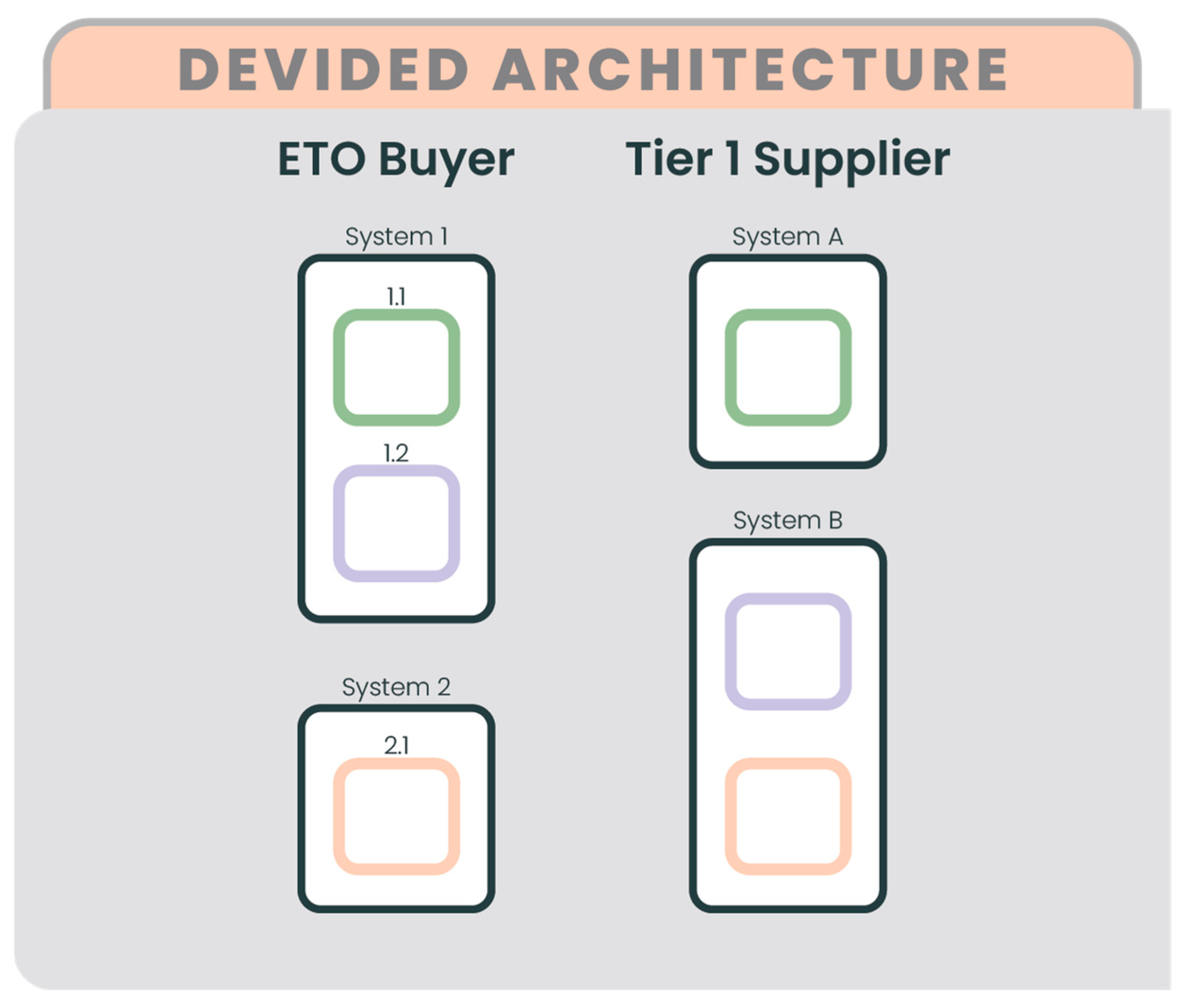

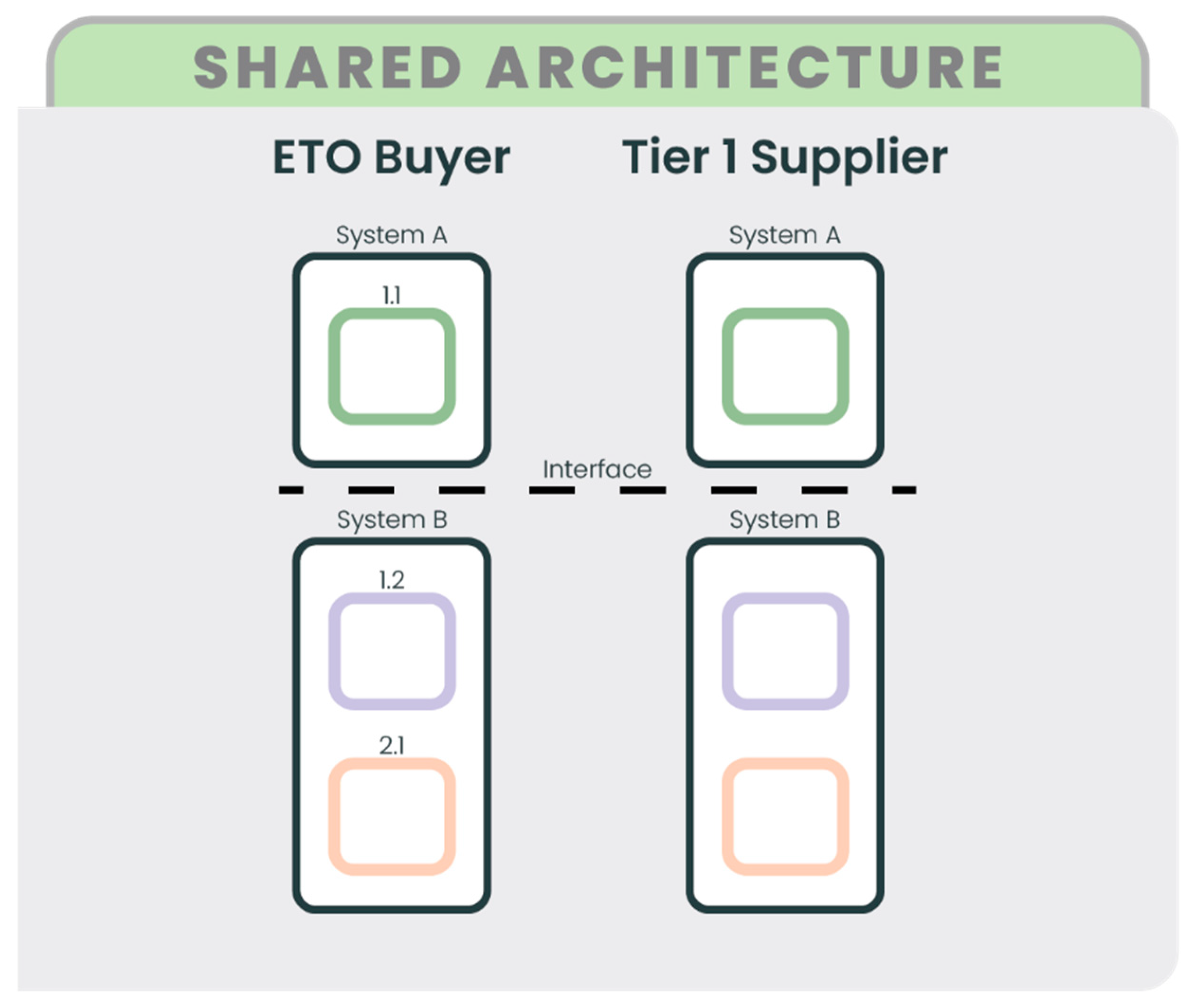

- Modelling of divided and shared architecture where modules, interfaces, and decomposition are not harmonised and harmonised, respectively, across buyer and supplier.

- Modelling of disjointed and coordinated activities describing the process architecture that is affected by the divided and shared architecture.

4.2. System Decomposition: Shared Across Organisations

4.3. Modules and Interfaces: For Interorganisational Alignment of Key Design Characteristics

4.4. Coordinated Activities: Consistent Between Organisations

- Describing how the use of system decomposition can be shared across buyer and supplier.

- Describing how the module and interfaces can be driven by aligning key design characteristics inter-organisationally.

- Describing how the activities of both organisations can be kept consistent and mutually beneficial in order to facilitate the behavioural change that can be capitalised through the architecture.

5. Case Outcome

5.1. System Description and Decomposition

5.2. Architecture Impact on System Delivery Process

- When the supplier anticipates that they have to start from scratch on system A, they cannot look up which resources and how many were needed the last time they delivered a similar system. (In this scenario, only the tank in functional system 2 was changed, the pump and pressure vessel specs remained the same.) The fact that they cannot learn from previous resource-use means that they have to guess which resources to commit and therefore are forced to overestimate (e.g., materials, people, services, etc.). This involves spending time to get familiar with the system and conducting a quantity take-off for the cost estimate. In this case, the supplier was counting flanges and fittings on the P&IDs to estimate materials and fitter hours in their workshop. Overcommitting the resources in the estimate led to a quote that was higher than it needed to be. Practically speaking, when such significant time is spent obtaining these estimates, it takes time away from other activities.

- When quantity take-offs are what they spend their time on, the supplier does not have the time to ask different sub-suppliers to analyse which are better options for the project circumstances. For instance, if the project is cross-Atlantic, there would be no time to ask multiple local sub-suppliers for quotes for the large tank and compare those with the increased shipping costs of procuring it from a local sub-supplier and shipping it overseas.

- Similarly, they do not know the sub-systems well enough to identify which components they should prioritise procurement of due to long lead times. As an example, generally speaking, the tanks are a long lead-time item procured from a sub-supplier. With this in mind, it was identified that for units that combine both tanks as well as pumps, the work on such units could only commence once the tank had been supplied. This meant that not getting the tank order in early at the sub-supplier was halting the remaining work on the “combined units” such as system A. Again, even though only the tank design of functional system 2 was changed, and nothing on system A, the supplier still had to anticipate that system A was unique and therefore did not know the equipment well enough to commit early to their sub-suppliers.

- Additionally, when the people executing the project begin their work, the supplier is not be able to look to reuse best-solution principles for assembly from previous projects, since they again assume that all parts of the scope are new and unique. This meant that the number of fitter hours spent in the workshop was higher than it needed to be.

- Finally, a general comment was made that this discrepancy was causing the need for more clarifications during the delivery process between the buyer and supplier.

5.3. Shared Architecture Improvement Principles

- Due to the increased transparency in the tender material, the supplier can now utilise historical data for estimating the quantity and type of resources needed for a project. According to the supplier, using actual consumption data would lead to less over-commitment of materials and services and thus a more competitive quote for the buyer. For the supplier, on the one hand, the over-commitment of resources has typically had them say no to other projects only to find out that they did in fact have time in the end. Therefore, avoiding over-commitment and accepting more projects would increase their own utilisation, leading to increases in the supplier’s revenue. On the other hand, avoiding a too-low estimate means that they would avoid having to pay overtime to meet the project deadline, thus leading to lower internal costs for the supplier.

- When using historical data, the supplier also has to spend less time during the quotation process making the estimate, which frees up time for other strategic activities. It means that the supplier has time to ask different sub-suppliers to analyse which are better options for the project circumstances.

- Likewise, the fact that sub-systems are now known means, the supplier can now begin procurement with a long lead-time scope as one of the very first things in the delivery process. This in turn means that combined units are not getting unnecessarily halted.

- Furthermore, the supplier argues that best-solution principles for assembly from previous projects would be easier to identify, thus reducing the number of fitter hours spent in the workshop.

- Lastly, the supplier claims that there would be fewer clarifications from the buyer during the delivery process.

5.4. Shared Architecture Financial Effect of Improvement Principles

5.5. Comparison of Results to Previous Litterature

6. Discussion and Conclusions

6.1. Implications for Research

6.2. Implications for Practice

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wortmann, J.C. Production Management Systems for One-of-a-Kind Products. Comput. Ind. 1992, 19, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobday, M. The Project-Based Organisation: An Ideal Form for Managing Complex Products and Systems? Res. Policy 2000, 29, 871–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, C.; McGovern, T. Product Life Cycle Management in Engineer-to-Order Industries. Int. J. Technol. Manag. 2009, 48, 153–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, C.; Earl, C.F.; McGovern, T. An Analysis of Company Structure and Business Processes in the Capital Goods Industry in the UK. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2000, 47, 414–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, C. A Dynamic Analysis of a Green Closed-Loop Supply Chain with Different On-Line Platform Smart Recycling and Selling Models. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2025, 200, 110748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, R. Creating Modular Platforms for Strategic Flexibility. Des. Manag. Rev. 2004, 15, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.; Zha, X.; Ma, J.; Li, B.; Wang, X. Dynamic Optimal Control Strategy of CCUS Technology Innovation in Coal Power Stations Under Environmental Protection Tax. Systems 2025, 13, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hvam, L.; Herbert-Hansen, Z.N.L.; Haug, A.; Kudsk, A.; Mortensen, N.H. A Framework for Determining Product Modularity Levels. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2017, 9, 1687814017719420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foehr, M.; Gepp, M.; Vollmar, J. Challenges of System Integration in the Engineer-to-Order Business. In Proceedings of the Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society (IECON), Yokohama, Japan, 9–12 November 2015; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 73–79. [Google Scholar]

- Dědina, D.; Sanova, P. Creating a Competitive Advantage by Developing an Innovative Tool to Assess Suppliers in Agri-Food Complex. J. Cryptol. 2013, 5, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, T.; Davies, A.; Gann, D.M. Creating Value by Delivering Integrated Solutions. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2005, 23, 360–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haug, A. Improving the Design Phase Through Interorganisational Product Knowledge Models. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2013, 51, 626–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harlou, U. Developing Product Families Based on Architectures: Contribution to a Theory of Product Families; Technical University of Denmark: Kongens Lyngby, Denmark, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hubka, V.; Eder, W.E. Theory of Technical Systems: A Total Concept Theory for Engineering Design; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1988; ISBN 978-3-642-52123-2. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, G.Q.; Mak, K.L. Modelling the Customer—Supplier Interface over the World-Wide Web to Facilitate Early Supplier Involvement in the New Product Development. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part B J. Eng. Manuf. 2000, 214, 759–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.Q.; Mak, K.L. WeBid: A Web-Based Framework to Support Early Supplier Involvement in New Product Development. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2000, 16, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, M. Early Supplier Involvement (ESI) in Product Development; Universitaet St. Gallen—Hochschule fuer Wirtschafts-, Rechts-und Sozialwissenschaften: Gallen, Switzerland, 1996; ISBN 0-591-11461-5. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, M.-A.; Abdul-Nour, G. Integrating Modular Design Concepts for Enhanced Efficiency in Digital and Sustainable Manufacturing: A Literature Review. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 4539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steward, D.V. The Design Structure System: A Method for Managing the Design of Complex Systems. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 1981, EM-28, 71–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakala, P.K.; Allada, V. Effective Supplier Involvement in Product Development Projects. In Proceedings of the International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exposition, Chicago, IL, USA, 5–10 November; American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME): New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Askhøj, C.; Christensen, C.K.F.; Mortensen, N.H. Cross Domain Modularization Tool: Mechanics, Electronics, and Software. Concurr. Eng. 2021, 29, 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küchenhof, J.; Berschik, M.C.; Heyden, E.; Krause, D. Methodical Support for the New Development of Cyber-Physical Product Families. Proc. Des. Soc. 2022, 2, 495–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Zhao, G.; Wang, T. A General Framework of Mechatronic Modular Architecture. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2013, 5, 969304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruun, H.P.L.; Mortensen, N.H.; Harlou, U. Interface Diagram: Design Tool for Supporting the Development of Modularity in Complex Product Systems. Concurr. Eng. 2014, 22, 62–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breimann, R.; Fett, M.; Küchenhof, J.; Gomberg, I.; Kirchner, E.; Krause, D.; Trieu, H.K. A Method for Optimizing Product Architectures for the Management of Disturbance Factors. Procedia CIRP 2023, 119, 1041–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackl, J.; Krause, D.; Otto, K.; Windheim, M.; Moon, S.K.; Bursac, N.; Lachmayer, R. Impact of Modularity Decisions on a Firm’s Economic Objectives. J. Mech. Des. 2020, 142, 041403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuefle, M.; Muschik, S.; Bursac, N.; Krause, D. Coping Asynchronous Modular Product Design by Modelling a Systems-in-System. Proc. Des. Soc. 2022, 2, 2553–2562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erixon, G.; von Yxkull, A.; Arnström, A. Modularity-the Basis for Product and Factory Reengineering. CIRP Ann. 1996, 45, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Weck, O.L. Determining Product Platform Extent. In Product Platform and Product Family Design: Methods and Applications; Simpson, T.W., Siddique, Z., Jiao, J.R., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 241–301. ISBN 978-0-387-29197-0. [Google Scholar]

- Siiskonen, M.; Malmqvist, J.; Folestad, S. Pharmaceutical Product Modularization as a Mass Customization Strategy to Increase Patient Benefit Cost-Efficiently. Systems 2021, 9, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siiskonen, M.; Govender, R.; Malmqvist, J.; Folestad, S. Modelling the Cost-Benefit Impact of Integrated Product Modularisation and Postponement in the Supply Chain for Pharmaceutical Mass Customisation. J. Eng. Des. 2023, 34, 865–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakkanen, J.; Juuti, T.; Lehtonen, T. Brownfield Process: A Method for Modular Product Family Development Aiming for Product Configuration. Des. Stud. 2016, 45, 210–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, G.O.; Bertram, C.A.; Mortensen, N.H. Towards Best Practices in the Engineer-To-Order Business: A Framework for the Structured Analysis of Commissioning Processes. Proc. Des. Soc. Des. Conf. 2020, 1, 1017–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgue, O.; Paissoni, C.; Panarotto, M.; Isaksson, O.; Andreussi, T.; Viola, N. Design for Test and Qualification Through Activity-Based Modelling in Product Architecture Design. J. Eng. Des. 2021, 32, 646–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elstner, S.; Krause, D. Towards an Early Consideration of Ramp-Up Phase in the Product Development of Complex Products. In Proceedings of the 12th International Design Conference, Dubrovnik, Croatia, 21–24 May 2012; Volume 70, pp. 859–868. [Google Scholar]

- Halfmann, N.; Elstner, S.; Krause, D. Product and Process Evaluation in the Context of Modularization for Assembly. In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Engineering Design (ICED 11), Impacting Society Through Engineering Design, Lyngby/Copenhagen, Denmark, 15–18 August 2011; Volume 5, pp. 271–281. [Google Scholar]

- Rong, Z.; Yang, Z.; Li, Y.; Chen, K.; Dan, B. Modular Product Design Based on the Supply Chain Network. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2017, 9, 1687814017732308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosch, M.; Beckmann, G.; Krause, D. Approach to Visualize the Supply Chain Complexity Induced by Product Variety. In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Engineering Design (ICED 11), Impacting Society Through Engineering Design, Lyngby/Copenhagen, Denmark, 15–18 August 2011; Volume 5, pp. 249–258. [Google Scholar]

- Blees, C. Eine Methode Zur Entwicklung Modularer Produktfamilien [A Method for Developing Modular Product Families]. Ph.D. Thesis, Hamburg University of Technology, Hamburg, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Greve, E.; Fuchs, C.; Hamraz, B.; Windheim, M.; Schwede, L.-N.; Krause, D. Investigating the Effects of Modular Product Structures to Support Design Decisions in Modularization Projects. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management, Singapore, 14–17 December 2020; pp. 295–299. [Google Scholar]

- Krause, D.; Beckmann, G.; Eilmus, S.; Gebhardt, N.; Jonas, H.; Rettberg, R. Integrated Development of Modular Product Families: A Methods Toolkit. In Advances in Product Family and Product Platform Design: Methods & Applications; Simpson, T.W., Jiao, J.R., Siddique, Z., Hölttä-Otto, K., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 245–269. ISBN 978-1-4614-7937-6. [Google Scholar]

- Wagenmann, S.; Krause, A.; Rall, J.; Kaeske, J.; Schoeck, M.; Bursac, N.; Albers, A. Reference Architecture for Metadata Management—A Case Study on Data Mining in the Development of Cyber-Physical Systems. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management (IEEM), Singapore, 18–21 December 2023; pp. 1057–1061. [Google Scholar]

- Mortensen, N.H.; Hansen, C.L.; Løkkegaard, M.; Hvam, L. Assessing the Cost Saving Potential of Shared Product Architectures. Concurr. Eng. 2016, 24, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, K.; Hölttä-Otto, K.; Simpson, T.W.; Krause, D.; Ripperda, S.; Ki Moon, S. Global Views on Modular Design Research: Linking Alternative Methods to Support Modular Product Family Concept Development. J. Mech. Des. 2016, 138, 071101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küchenhof, J.; Krause, D. Initial Integral Product and Assembly Structuring: A Case Study. Proc. Des. Soc. Des. Conf. 2020, 1, 2305–2314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küchenhof, J.; Tabel, C.; Krause, D. Assessing the Influence of Generational Variety on Product Family Structures. Procedia CIRP 2020, 91, 796–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacono, J.C.; Brown, A.; Holtham, C. The Use of the Case Study Method in Theory Testing: The Example of Steel Emarketplaces. Electron. J. Bus. Res. Methods 2011, 9, 57–65. [Google Scholar]

- Voss, C.; Tsikriktsis, N.; Frohlich, M. Case Research in Operations Management. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2002, 22, 195–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat Industrial Producer Price Index Overview. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Industrial_producer_price_index_overview (accessed on 6 October 2024).

- Baldwin, C.Y.; Clark, K.B. Modularity in the Design of Complex Engineering Systems. In Complex Engineered Systems: Science Meets Technology; Braha, D., Minai, A.A., Bar-Yam, Y., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; pp. 175–205. ISBN 978-3-540-32834-6. [Google Scholar]

- Jiao, R.J.; Simpson, T.W.; Siddique, Z. Product Family Design and Platform-Based Product Development: A State-of-the-Art Review. J. Intell. Manuf. 2007, 18, 5–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisner, H. Systems Engineering: Building Successful Systems; Morgan & Claypool Publishers: San Rafael, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Philbin, S.P. Managing Complex Technology Projects. Res. Technol. Manag. 2008, 51, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadows, D.H. Thinking in Systems: A Primer; Earthscan: London, UK, 2009; ISBN 978-1-84407-726-7. [Google Scholar]

- Eppinger, S.D. A Planning Method for Integration of Large-Scale Engineering Systems. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Engineering Design, Tampere, Finland, 19–21 August 1997; Volume 97, pp. 199–204. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez, R.; Mahoney, J.T. Modularity, Flexibility, and Knowledge Management in Product and Organization Design. Strateg. Manag. J. 1996, 17, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEC 81346-1:2009; Industrial Systems, Installations and Equipment and Industrial Products-Structuring Principles and Reference Designations-Part 1: Basic Rules. IEC & ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009.

- Mueller, G.O.; Mangum, W.D.; Mortensen, N.H. A Method for Revealing Misalignment in Engineer-To-Order Products and Process Structures. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Mass Customization and Personalization–Community of Europe (MCP-CE 2020), Novi Sad, Serbia, 23–25 September 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez, R. Product and Process Architectures in the Management of Knowledge Resources. In Resources, Technology and Strategy; Taylor and Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2005; pp. 99–120. ISBN 0203982258. [Google Scholar]

- Bertram, C.A. Variation Management in Project-Based Design. Ph.D. Thesis, Technical University of Denmark, Kongens Lyngby, Denmark, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hvam, L.; Mortensen, N.H.; Riis, J. Product Customization; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; 283p. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q. Risk, Risk Aversion and the Optimal Time to Produce. IIE Trans. 2007, 39, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, A.J.; Kochhar, A.K. Manufacturing Best Practice and Performance Studies: A Critique. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2002, 22, 289–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador, F.; Villena, V.H. Supplier Integration and NPD Outcomes: Conditional Moderation Effects of Modular Design Competence. J. Supply Chain. Manag. 2013, 49, 87–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Huo, B.; Zhang, M.; Wang, B.; Zhao, X. The Impact of Modular Designs on New Product Development Outcomes: The Moderating Effect of Supply Chain Involvement. SCM 2018, 23, 444–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeishi, A. Knowledge Partitioning in the Interfirm Division of Labor: The Case of Automotive Product Development. Organ. Sci. 2002, 13, 321–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, M.; Squire, B. Modularization and the Impact on Supply Relationships. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2007, 27, 1192–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertram, C.A.; Mueller, G.O.; Løkkegaard, M.; Mortensen, N.H.; Hvam, L. Why Engineer-To-Order Portfolio Rationalization Stalls: Challenges in Standardization, Modularization, Platform Design and Mass Customization. Proc. Des. Soc. Des. Conf. 2020, 1, 2265–2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enz, M.G.; Lambert, D.M. Measuring the Financial Benefits of Cross-Functional Integration Influences Management’s Behavior. J. Bus. Logist. 2015, 36, 25–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Job Position | Method | Purpose | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Buyer, Category manager 1 | Interviews | Preparation and context. Understanding past tender material, financial data, and system design. | 2 h |

| Buyer, Category director 1 | Interview | 1 h | |

| Buyer, Senior Engineer 1 | Interviews | 3 h | |

| Buyer, Department manager 1 | Interviews | 3 h | |

| Buyer, Category manager 1 | Meetings | Introduction to concept of shared architecture—Supplier A. | 2 h |

| Buyer, Department manager 1 | |||

| Supplier A, Senior Engineer 1 | |||

| Supplier A, Project Manager 1 | |||

| Supplier A, Project Manager 2 | |||

| Buyer, Category manager 1 | Meetings | Introduction to concept of shared architecture—Supplier B. | 2 h |

| Buyer, Department manager 1 | |||

| Supplier B, Senior Engineer 1 | |||

| Supplier B, Project Manager 1 | |||

| Supplier B, Chief Operating Officer 1 | |||

| Buyer, Category manager 1 | Workshop | Analysing buyer and supplier cost/time drivers, delivery process, and identifying improvement/alignment areas—Supplier A. | 4.5 h |

| Buyer, Senior Engineer 1 | |||

| Buyer, Department manager 1 | |||

| Supplier A, Senior Engineer 1 | |||

| Supplier A, Project Manager 1 | |||

| Supplier A, Project Manager 2 | |||

| Buyer, Category manager 1 | Workshop | Analysing buyer and supplier cost/time drivers, delivery process, and identifying improvement/alignment areas—Supplier B. | 4.5 h |

| Buyer, Senior Engineer 1 | |||

| Buyer, Department manager 1 | |||

| Supplier B, Senior Engineer 1 | |||

| Supplier B, Project Manager 1 | |||

| Supplier B, Chief Operating Officer 1 | |||

| Buyer, Category manager 1 | Workshop | Investigating operability and feasibility of the shared architecture—Supplier B. | 4.5 h |

| Buyer, Senior Engineer 1 | |||

| Buyer, Department manager 1 | |||

| Supplier A, Senior Engineer 1 | |||

| Supplier A, Project Manager 1 | |||

| Supplier A, Project Manager 2 | |||

| Buyer, Category manager 1 | Workshop | Investigating operability and feasibility of the shared architecture—Supplier B. | 4.5 h |

| Buyer, Senior Engineer 1 | |||

| Buyer, Department manager 1 | |||

| Supplier B, Senior Engineer 1 | |||

| Supplier B, Project Manager 1 | |||

| Supplier B, Chief Operating Officer 1 | |||

| Buyer, Category manager 1 | Interviews | Discuss/observe adoption of shared architecture. | 2 h |

| Buyer, Senior Engineer 1 | Interview | 1 h | |

| Buyer, Department manager 1 | Interviews | 4 h |

| Metric | Equation | Calculation | Financial Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Equation (2) | ~10% reduction in total cost of the project | ||

| Equation (1) | ~35% reduction in total cost of the project |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sohrt, M.; Blinkenberg, W.; Mortensen, N.H. Shared Product Architectures for Engineering-to-Order Buyers and Suppliers: Insights from a Case Study. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 9357. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15179357

Sohrt M, Blinkenberg W, Mortensen NH. Shared Product Architectures for Engineering-to-Order Buyers and Suppliers: Insights from a Case Study. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(17):9357. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15179357

Chicago/Turabian StyleSohrt, Mikkel, Willads Blinkenberg, and Niels Henrik Mortensen. 2025. "Shared Product Architectures for Engineering-to-Order Buyers and Suppliers: Insights from a Case Study" Applied Sciences 15, no. 17: 9357. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15179357

APA StyleSohrt, M., Blinkenberg, W., & Mortensen, N. H. (2025). Shared Product Architectures for Engineering-to-Order Buyers and Suppliers: Insights from a Case Study. Applied Sciences, 15(17), 9357. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15179357