Featured Application

The integrated-information measure Φ provides a practical tool for quantifying multipartite entanglement and identifying modular structures in many-body quantum states, thereby guiding tensor-network decompositions and variational ansätze. In quantum computing, Φ can suggest optimal qubit partitions to minimize information loss in error-correction procedures and inform distributed algorithm design. By constructing integration dendrograms, one can visualize hierarchical correlation patterns in quantum simulators and, speculatively, infer functional clusters in quantum-inspired models of neural networks.

Abstract

We introduce a quantum integrated-information measure for multipartite states within the Relational Quantum Dynamics (RQD) framework. is defined as the minimum quantum Jensen–Shannon distance between an n-partite density operator and any product state over a bipartition of its subsystems. We prove that its square root induces a genuine metric on state space and that is monotonic under all completely positive trace-preserving maps. Restricting the search to bipartitions yields a unique optimal split and a unique closest product state. From this geometric picture, we derive a canonical entanglement witness directly tied to and construct an integration dendrogram that reveals the full hierarchical correlation structure of . We further show that there always exists an “optimal observer”—a channel or basis—that preserves better than any alternative. Finally, we propose a quantum Markov blanket theorem: the boundary of the optimal bipartition isolates subsystems most effectively. Our framework unites categorical enrichment, convex-geometric methods, and operational tools, forging a concrete bridge between integrated information theory and quantum information science.

1. Introduction

Modern developments in quantum physics and theories of consciousness increasingly suggest that relations and information, rather than isolated material objects, are fundamental to reality. Recent proposals cast consciousness itself as a state of matter, suggesting a natural home for IIT in quantum-mechanical systems [1]. In particular, integrated information theory (IIT) posits that the level of intrinsic awareness or consciousness of a physical system corresponds to the quantity of integrated information (denoted ) present in its state [2,3]. IIT argues that a system whose information is integrated, i.e., not decomposable into independent parts, has an irreducible subjective existence for itself [4]. This aligns with interpretations of quantum mechanics emphasizing that quantum states are relational rather than absolute [5]. John Wheeler’s famous dictum “every it derives its significance from bits” encapsulates the view that what fundamentally exists are acts of observation or informational relations, not static isolated entities [6]. Relational Quantum Mechanics (RQM) [5,7] formalizes this idea, proposing that the state of a quantum system is nothing more than the information one physical system has about another. Embracing this relational stance, we further posit that the “being” of a quantum system is constituted by the network of quantum information it shares with the rest of the world. Under this hypothesis, consistent with the idealistic interpretation of IIT (IIT 4.0’s “idealistic ontology” [8]), any system with non-zero integrated information () possesses intrinsic existence (a rudimentary point of view “for itself”), whereas indicates complete reducibility (no intrinsic unity beyond its parts).

Building on RQM, Relational Quantum Dynamics (RQD) elevates the primacy of informational relations by construing quantum states as inherently contextual and observer-relative, thereby embedding the IIT notion of integrated information within the formal structure of quantum theory. Under RQD, each system’s “being” arises from a network of dynamical information flows—quantified by —connecting its constituent subsystems, and classical spacetime and observations emerge from patterns of these relational correlations. By forgoing absolute state assignments in favor of context-dependent relational states, RQD unifies quantum measurement, spacetime emergence, and observerhood in a single coherent ontology [9].

To explore these ideas rigorously, we develop a formal measure of integrated information for an n-partite quantum system in state . We require a quantitative gauge of how holistically correlated or irreducible the state is. In classical IIT, measures based on Kullback–Leibler divergence or mutual information have been proposed to quantify the loss of information upon splitting a system [10,11]. Here, a natural choice for the quantum case is the quantum Jensen–Shannon divergence (), a symmetrized and bounded measure of distance between quantum states [12,13]. Intuitively, will serve as an “integration distance”; it vanishes if can be exactly factorized into independent local states (no integration) and grows as becomes more entangled or correlated across subsystems (more integration). Specifically, we define as the minimum between and any product state obtained by partitioning the system. Let be a partition of the n subsystems into k disjoint groups (blocks), and define the corresponding product state as the tensor product of the reduced density operators on each block. Then we define

In other words, quantifies the closest that can be (in terms of quantum Jensen–Shannon divergence) to an uncorrelated state. If is itself a product state under some partition, then (no integrated information). If is highly entangled or correlated across all subsystems, will be large, indicating strong irreducible correlations. This construction extends to the quantum domain that the integrated information measures use in classical IIT [10,11], with replacing classical divergence or mutual information measures. Importantly, as we will show, enjoys several properties (data-processing inequalities, convexity, a true metric structure) that make analytically tractable and well-behaved even for high-dimensional or rank-deficient states.

In developing our framework, we prove four main results about and as outlined above: (1) is monotonic under processing (no observer can increase it), (2) the square-root of is a metric on state space, (3) it suffices to consider bipartitions to attain the minimum in , and (4) the observer can be formalized as a metric-space functor that is non-expansive. These results lay the groundwork for analyzing integrated information in quantum systems. After presenting these, we introduce a set of novel convex-geometric and operational insights that arise from viewing as a distance to the convex set of product states. This geometric perspective reveals that every state has a unique nearest product state (defining a canonical minimum information partition for ), and it unlocks an array of corollaries including convexity and robustness of , a natural gradient-flow that “dis-integrates” a state, and even a direct construction of an entanglement witness from . Furthermore, we leverage the unique optimal partition to build a hierarchical decomposition of any multipartite state into successively independent components, an integration dendrogram that maps out the structure of correlations in the state.

Finally, we explore two broader implications: an observer selection principle stating that one measurement basis or channel maximally preserves a system’s integrated information (suggesting a first-principles derivation of preferred pointer bases in decoherence theory), and a prospective quantum Markov blanket theorem, which identifies, for any subsystem, the minimal “boundary” that most effectively screens it off from the rest of the system. To our knowledge, this is the first fully metric-geometric construction of a quantum-IIT measure that (i) is provably a Lawvere metric enrichment of CPM, (ii) collapses to bipartitions by convexity, (iii) yields a canonical entanglement witness, and (iv) admits a functorial observer-selection principle.

2. Integrated Information Measure Definition

Before formalizing integrated information, we briefly review the quantum Jensen–Shannon divergence (). Given two quantum states (density operators) and on the same Hilbert space, is defined as the quantum analog of the classical Jensen–Shannon divergence, which itself is a symmetrized and smoothed version of Kullback–Leibler divergence. One convenient expression is

where is the von Neumann entropy [13]. This quantity is symmetric () and bounded between 0 and . In particular, if and only if , and the maximum is attained for perfectly distinguishable orthogonal states. We will not require the detailed form of beyond these properties; what is crucial for us is that it behaves as a distance measure on the space of states.

Definition 1

(Quantum Integrated Information). For a quantum state ρ composed of n sub-systems, the integrated information is defined as the minimum quantum Jensen–Shannon divergence between ρ and any product state on a partition of the subsystems. In formula

where the minimum is taken over all possible ways of partitioning the set of subsystems into disjoint blocks , and denotes the reduced state on block . By convention, we consider only nontrivial partitions with at least two blocks (so if ρ is a total product state, is achieved when each subsystem is isolated in its own block).

This definition captures the degree of holism or irreducibility in . If factorizes neatly into two or more independent components, then will be small (zero if an exact factorization exists). Conversely, if no accurate factorization exists (all partitions yield significant divergence), is large, indicating that the state’s information cannot be localized to separate parts without a significant loss. In practice, one might compute by evaluating for each candidate partition and taking the minimum. While the number of partitions grows quickly with n, our results below (especially Theorem 3) will sharply reduce the search space.

3. Monotonicity and Metric Properties of

We first establish two fundamental properties of the quantum JSD that underpin the integrated information measure: a data-processing inequality and a metric structure. These ensure that behaves sensibly under observers and has a well-defined geometry.

Theorem 1

(Data-Processing Monotonicity). For any two states and any CPTP map (quantum channel) , the quantum Jensen–Shannon divergence cannot increase under processing:

In particular, if an “observer” interacts with or measures the system (modeled by ), the integrated information of the post-interaction state cannot exceed that of the pre-interaction state .

Proof

(Sketch). This is the quantum analog of the classical data-processing inequality, and it holds because belongs to the class of contractive divergences. Indeed, the JSD can be expressed in terms of the quantum relative entropy as

(the minimal relative entropy to an intermediary state)—an expression which inherits the monotonicity of D under CPTP maps [14,15]. Alternatively, one can invoke the joint convexity of and the complete positivity of to show

and apply monotonicity of von Neumann entropy under partial trace. The inequality then follows immediately: for any partition that attains (or approximates) the minimum for , applying to both and each product component cannot increase the divergence, so the minimal divergence for is bounded by that of . □

This theorem formalizes the intuitive idea that observation cannot create integration. Any act of coarse-graining, measurement, or decoherence will tend to lose correlations or entanglement, never to introduce new irreducible correlations that were not already present. In category-theoretic terms, one can frame this as an enriched functor property: each physical process or observation defines a mapping between state spaces that does not expand distances. More precisely, we can view each system’s state space as a metric space with (as introduced below). Then any CPTP map is a -enriched functor between these metric spaces, meaning for all states (Lawvere metric space enrichment). This functorial perspective identifies an “observer” or dynamics with a structure-preserving map in an information metric space. By Theorem 1, all such observers are non-expansive in the metric, and hence cannot increase . This categorical formulation helps unify the notion of observers across classical and quantum domains, but for the remainder of this paper, we will generally work in standard information-theoretic terms.

Practical Implications of Monotonicity: Theorem 1 implies a powerful experimental guarantee. In most tomographic protocols, one acquires raw measurement frequencies and then applies a maximum-likelihood (ML) estimator to project onto the physical state space. That ML step is itself a CPTP map, so by monotonicity, the post-processed can only be smaller than the true of the prepared state. In other words, any non-zero we report is a conservative lower bound on the system’s intrinsic holism. Combined with the 1-Lipschitz bound from Section 4, which shows that, for trace-norm errors , the resulting uncertainty in is at most , we see that standard tomography fidelities (∼2%) translate into bits. Thus, even imperfect state reconstruction cannot spuriously inflate , making it a robust witness of genuine multipartite integration.

as a Resource Monotone: Beyond its operational significance, monotonicity under all CPTP maps elevates to the status of a resource-theoretic monotone. In entanglement theory, one demands that valid entanglement measures never increase under the free operations of LOCC; analogously, here, any allowed quantum channel can only degrade holism. This endows with the same foundational role for “quantum holism” that entanglement measures play for nonlocality:

for every CPTP map . Consequently, quantifies a resource that cannot be generated by noise or local processing, and it fits naturally into the burgeoning framework of quantum resource theories.

Next, we establish that the quantum JSD endows state space with a true metric, not just a divergence. It is known that the classical Jensen–Shannon divergence yields a legitimate distance metric via its square root. The quantum version inherits a similar property:

Theorem 2

(Metric Structure of Quantum JSD). Define for density operators . Then is a metric on the space of quantum states. In other words, it satisfies positivity, symmetry, and the triangle inequality. In particular, if and only if , and for any three states we have

Proof

(Sketch). The non-negativity and symmetry of are immediate from the properties of . The non-degeneracy () holds because iff . The crux is the triangle inequality. We employ a known characterization: a divergence is of the negative type (or negative definite) if and only if its square root defines a metric [16]. Recent works have shown that the (classical) Jensen–Shannon divergence is of a negative type, allowing the construction of an isometric embedding of probability distributions into a real Hilbert space [17]. The quantum Jensen–Shannon divergence shares this property [18]. Specifically, one can show is negative-definite on quantum states, for example, by expressing it as an distance in an appropriate purified representation or by verifying the inequality for any choices of states and real coefficients summing to 0 (a hallmark of negative-type functions). Given negative definiteness, Schoenberg’s theorem [16] guarantees that satisfies the triangle inequality. Hence, is a metric on state space. □

This result is noteworthy: although many quantum divergences, for example, quantum relative entropy, do not yield a true metric, the Jensen–Shannon divergence does. Thus, the set of density matrices can be treated as a metric space with distance . Geometrically, is not a Euclidean space but can be embedded isometrically into a (potentially infinite-dimensional) inner-product space. Intuitively, one can think of each quantum state as a point in some high-dimensional “feature space” such that is the Euclidean distance between those points. This will allow us to leverage convex geometry within the space of quantum states.

4. Optimal Factorizations and Convex Geometry of

We now turn to analyzing the minimization in

Two fundamental questions arise: (a) Which partition achieves the minimum? (b) Is the minimum achieved by a unique state? We will see that thanks to the metric structure and convexity properties of , the answer is remarkably neat: it is always a bipartition (a split into blocks) that attains the minimum, and moreover the closest product state is unique. This resolves any ambiguity in the notion of a “minimum information partition” and provides a well-defined integrated whole versus parts for the system.

Theorem 3

(Bipartition Sufficiency and Existence of Optimal Product State). For any state ρ on n subsystems, the minimum in Definition 1 is attained on some bipartition of the system. In other words,

where the minimum is over all splits of into two disjoint groups A and B. Furthermore, there exists at least one product state that achieves this minimum, and for each minimizing bipartition, the optimal product state on that cut is unique. In particular, there is a unique closest product state , where is the optimal partition.

Proof

(Sketch). The fact that one can restrict to blocks without loss of generality follows from a simple inequality: for any partition with blocks, one can show that merging any two blocks cannot increase the divergence. Intuitively, splitting into more than two parts introduces additional independent components, which can only make it harder for a single product state to approximate . More formally, consider three disjoint subsets of subsystems; one can show

because (where ) allows correlations between X and Y that the fully factorized version forbids, and thus it is closer to (lower divergence). Iterating this argument, any partition with can be coarse-grained into a bipartition that yields an equal or smaller . Hence the minimum occurs at some . Next, because for a fixed bipartition the set of product states is a compact convex subset of state space and is a continuous function of , the infimum over is actually a minimum (attained at some ). This uses the compactness of the set of marginal states and ; any minimizing sequence has a convergent subsequence in the product space by compactness, and by continuity, the limit is a minimizer. Finally, for a given bipartition, the uniqueness of the minimizing follows from the strict convexity of in its second argument. Quantum JSD is jointly convex [13] and in particular, if two distinct product states and both yield the same divergence

then any mixture (which is still a valid separable state on ) would produce for , contradicting the minimality. One can also argue from the negative-definite metric viewpoint that the distance-squared function is strictly convex on a geodesically convex domain of product states. Thus, the minimizer on each partition is unique. If there were multiple bipartitions achieving the same minimum value, one of their corresponding product states would still be closer in -distance than any other state, so we may define to be one of them. In generic cases, the optimal partition is unique as well (ties are non-generic and can be broken arbitrarily). □

We emphasize the important consequence: the closest product-state approximation to is unique. We denote this distinguished state by , where is an optimal bipartition. We may call the minimum information partition (MIP) of , borrowing terminology from IIT. There is no degeneracy in identifying the “best split” of the system—a fact that contrasts with earlier approaches where one often had to choose among candidate partitions or deal with ties. Uniqueness comes from the convexity of the divergence and can be seen as a benefit of using as opposed to mutual information, for example, which might not identify a unique optimal split in some cases.

With in hand, we can reinterpret the integrated information as a distance from to the set of disjoint-state products. In fact, Theorem 3 implies:

since . In words, is the squared distance (in the metric) from to the closed, convex set

of all bipartite product states. We can therefore leverage geometric intuition: computing is performing a metric projection of the point onto the set . By standard results in convex geometry and metric spaces, this immediately yields a raft of powerful corollaries:

- Convexity of . As an infimum (indeed minimum) of convex functions , the distance-to-set functionis convex on state space. Equivalently, for any two states and any ,This convexity means that mixing states cannot increase the integrated information beyond the mixture of their individual values. In practical terms, a noisy or probabilistic mixture of two configurations will tend to have less (or equal) holistic structure than a pure configuration, which aligns with intuition.

- Lipschitz Continuity (Robustness). The function is 1-Lipschitz continuous with respect to the metric . That is,for all states . Small changes or errors in the state can only cause small (at most proportional) changes in the integrated information. This follows from a general fact: in any metric space, the distance from a point to a convex set is a 1-Lipschitz function (intuitively, if and are close, their nearest projections on a convex set cannot be very different in distance). More concretely, one can use the triangle inequalityBut because might not be the optimal product for , soThus, . Swapping gives the two-sided Lipschitz bound. This robustness is crucial for empirical or experimental scenarios: it means will not fluctuate wildly due to small perturbations or noise in the state, making it a reliable quantity to estimate.

- Gradient Flow towards Dis-integration. By viewing as a squared-distance function in a (formal) Riemannian space, one can define a gradient descent dynamical system that flows toward its nearest product state. Concretely, we can write a continuous time equationwhich generates a trajectory that decreases monotonically and converges to the projection as . While here denotes a gradient with respect to the information geometry induced by , one can intuitively think of this as the state “pulling itself apart” into independent pieces. In practice, this gradient-flow could be implemented by a family of CPTP maps that progressively erode the holistic correlations. The advantage of framing it as a gradient flow is that it provides a principled algorithm for finding (the best factorized approximation) by following the steepest descent of integrated information, rather than using ad hoc separability criteria. Analyzing the specific form of is beyond our scope here, but it may be related to applying gentle local decoherence to remove entanglement at the fastest rate.

All these properties flow naturally from the convex geometric view of as a projection distance. This perspective has not, to our knowledge, been applied in previous integrated information literature, and it unlocks powerful tools from convex optimization and metric geometry to study and compute . We stress that and provide more information than just the scalar : they tell us exactly how the state can be optimally split and how far it is from such a split. In the next result, we show that can be used to construct a special entanglement witness that “certifies” the integrated information.

Lemma 1

(RKHS embedding of QJSD). Define Then k is a positive-definite kernel on the space of density operators. Hence by Schoenberg’s theorem [16,18], there exists a real reproducing-kernel Hilbert space and a feature map with

Proof

(Sketch). Since is bounded () and symmetric, the shifted kernel satisfies Schoenberg’s criterion for negative-type metrics, which guarantees a Hilbert-space embedding. □

Metric-gradient and operator pullback. From Lemma 1 and

we get in

Pulling this back via the Fréchet derivative

the stationarity condition yields

so that (up to a positive scalar) is precisely the normal operator defining the separating hyperplane in the original operator space.

Proposition 1

(Canonical Entanglement Witness). Let be the closest product state to ρ, achieved on the optimal bipartition . Define an observable (Hermitian operator) Then is an entanglement witness for the bipartition . In particular, has a non-negative expectation value on all product states factorized across and , yet has a strictly negative expectation on ρ itself. Moreover, the magnitude of this violation is exactly the integrated information:

In fact, is the optimal (most “detecting”) witness for the entanglement between and .

Proof.

By Lemma 1 and the metric-gradient calculation, the minimizing condition pulls back to , and hence is the geodesic-normal. Positivity on any product state follows because is the closest product state. The fully detailed proof of this proposition is presented in Appendix C. □

In summary, is a constructive, canonical witness to the entanglement or correlation that makes irreducible across its optimal split. It detects exactly the entanglement corresponding to and no more. In particular, quantifies the “violation” of being separable: the more integrated is, the more yields a negative expectation on it, with the gap equal to . One could say this provides an operational meaning to : it is the magnitude by which fails the best possible separability test. This is a novel connection between integrated information and entanglement theory — it bridges a geometrical measure of holistic correlation () with the traditional notion of an entanglement witness from quantum information. In practice, once one computes (by any method), one immediately obtains , which is an observable whose expectation value on is and on any fully factorized state (on that cut) is non-negative. Experimentally, measuring the set of local observables that constitute , which will generally be a difference of two reduced density operators, could verify the presence of entanglement and even quantify it in terms of integrated information.

5. Hierarchical Decomposition: The Integration Dendrogram

Thus far, we have focused on identifying a single “critical cut” that yields the minimal integrated information. We now show that this idea can be recursively applied to yield a hierarchical decomposition of the state into a tree of increasingly fine subsystems. The result is a binary tree (dendrogram) that represents the multi-scale structure of correlations in . This construction parallels hierarchical clustering in classical data analysis but here it is based on quantum information relationships intrinsic to itself.

The procedure is as follows:

- Level 0 (Root): Start with the full system as one set . Compute and find the unique optimal bipartition of S that achieves it. This is the root split of the dendrogram, and the value will label the root node as a measure of how hard it is to tear the entire system into two parts.

- Level 1: Now take the two blocks and separately. For each block (subsystem group) considered its own subsystem, compute its integrated information within that block, i.e., allow partitions internal to . Find the optimal bipartition of that achieves , and similarly partition optimally. This yields splits and at the next level. Attach these as children of the respective nodes in the tree, and label the nodes and with and .

- Continue recursively: At each subsequent level, for every current leaf node of the tree (which corresponds to some subset of qubits or subsystems), if that subset contains more than one elementary subsystem, compute its optimal bipartition and -value, and split it. Continue until every leaf is an individual elementary subsystem (which cannot be split further). The recursion will terminate after at most levels (when all subsystems are singletons).

The outcome of this algorithm is a full binary tree whose leaves are the individual subsystems , and whose internal nodes represent larger groupings that were optimally split. We call this tree the integration dendrogram of (see Appendix B). Each internal node is labeled by the -value of that grouping, i.e., how much integrated information had to be “broken” to split it into two parts.

To illustrate the usefulness of this dendrogram, consider its properties:

- Uniqueness and Stability: Because each bipartition at each step is unique (Theorem 3) and changes continuously with (Lipschitz continuity), the entire dendrogram is uniquely determined by and is robust to small perturbations. Small changes in will only gradually change the values and possibly slightly adjust the splits, but the overall hierarchical order (which splits occur at which scale) will not wildly reshuffle. This is in stark contrast to some heuristic clustering methods that can have unstable hierarchies. Here the hierarchy is rooted in strict convex optimal cuts at each step, making it canonical for each state.

- Multi-Scale Summary of Correlations: The dendrogram provides a multi-scale map of the entanglement/correlation structure in . The top of the tree tells you the largest-scale division (where the weakest global link in the system lies). Further down, you see progressively smaller modules and sub-modules, down to individual units. Each node’s height (the value for that subset) quantifies how strongly that subset resists factorization. A high at a certain node means that the subset is very integrated and only separable with a large loss, whereas a low node indicates a relatively weakly bound cluster that could almost be split without much information loss. In effect, one can read off which groups of subsystems form coherent modules and which connections are tenuous. For example, a branch of the dendrogram might show qubits 1,2,3 forming a tight sub-cluster (high internally) that only weakly connects (low cut) to another cluster of qubits 4,5, etc.

- Algorithmic Simplicity: Building the dendrogram requires solving the bipartition optimization at each level, which is the same type of problem as computing in the first place. While finding the optimal partition is NP-hard in general (since one might have to try all splits), focusing on pairwise splits at each level yields a manageable procedure. There are possible bipartitions of an n-element set, so a brute-force search at each level is exponential in the size of the current subset. However, since we do at most levels, the overall worst-case complexity is , which is exponential but not super-exponential. In practice, many splits will involve smaller subsets and thus fewer possibilities. Moreover, the computations for different branches can be performed in parallel. This is far more tractable than attempting to search among all partitions of all sizes simultaneously (a number that grows faster than ). Thus, the hierarchical approach breaks the problem into manageable pieces.

- Connections to Clustering: In classical data science, one often constructs hierarchical clustering dendrograms using metrics or information-based distances. Here we have the quantum analog: a dendrogram based on a rigorous information metric () applied not to classical data points but to the quantum state itself. Rather than clustering individual data samples, we are clustering subsystems of a single quantum state based on their entanglement structure. This opens the door to using visualization and cluster-identification techniques from classical analysis in quantum many-body systems. For instance, one could visualize the dendrogram with node heights proportional to values, giving a clear picture of the “integration profile” of the state across scales. Branch lengths indicate how much correlation binds subsystems at that split.

In summary, the integration dendrogram is a powerful new tool for analyzing multipartite quantum states. It yields a unique, stable, multi-scale decomposition of a state’s entanglement structure without requiring any ad hoc choices beyond the definition of . By reading the dendrogram, one can immediately identify which subsystems form natural groupings or communities (high internal ) and where the “weak links” between those groupings are (low between them). This has potential applications in understanding complex quantum networks or many-body systems: for example, identifying modules in an interacting spin chain, or coarse-grained functional units in a quantum neural network, etc. The dendrogram encapsulates an entire hierarchy of quantum integration within a single object.

6. Preferred Observers: The Max- Principle

We have shown that no observer (CPTP map) can increase integrated information (Theorem 1). A natural question arises: which observer loses the least integrated information? In other words, suppose we have a system in state , and we are allowed to “observe” it in some fashion, perhaps by making a measurement or by coarse-graining its degrees of freedom. Different observation schemes will preserve different fractions of the holistic correlations present in . Is there a principled way to choose the optimal observation that retains as much of as possible?

Remarkably, the answer is yes. We call this the Max- observer principle: among any reasonable family of observation channels, one can find a channel that maximizes the integrated information of the observed state . Moreover, can be interpreted as selecting the “best” basis or representation, in which to obtain classical information about without destroying its holistic structure. This has deep connections to the idea of a preferred basis in quantum decoherence theory [19]: the basis that is stable and preserves certain correlations. Here, we derive such a basis from first principles, using only the monotonicity of and the compactness of the channel space.

Theorem 4

(Optimal Observer Channel). Let be any compact set of CPTP maps (quantum channels) that one considers possible observers on the state ρ. For example, could be the set of all local projective measurements of each qubit (with the observer recording classical outcomes), or the set of all partial trace operations onto some subsystem, or more generally any parametrized family of channels. Then there exists at least one channel that maximizes the integrated information of the output:

Existence is guaranteed; there may in principle be more than one maximizer, but we can pick one. In other words, there is an optimal observer that preserves ρ’s integrated information better than any other in . Furthermore,

with equality only if the optimal channel effectively does nothing to disturb the relevant correlations. For example, could be the identity channel or an isometry embedding into a larger space.

Proof.

Because is a function with real value in the set of channels and is compact, the maximum value is attained (by the extreme value theorem). We only need to argue for the continuity of in a suitable topology in the space of CPTP maps. If we parametrize channels by their finite-dimensional Kraus operators, small changes in those operators yield small changes in the output state (in trace norm, say), which in turn yield small changes in (by Lipschitz continuity of ). Thus, is a continuous function in the compact set , and therefore there is a maximum. The inequality for all F is just Theorem 1, so the maximal value is bounded by . The equality would require that

for some product state that achieves . In practice, this implies that F does not erase any of the distinguishing information between and —essentially, F is invertible on the support of —which typically means that F is an embedding or trivial operation. □

Theorem 4 is simple but profound. It tells us that, given any constraint on how we observe the system, we can find a “best” way to observe it, if our criterion is to preserve integrated information. This can be thought of as the observer that loses the least holism. In effect, it picks an optimal classical description of the correlations of the quantum state. We highlight some implications and interpretations:

- Preferred Basis from First Principles: If is the set of all projective measurements on each subsystem (i.e., choosing a measurement basis for each qubit, for instance), then will pick a specific measurement basis on each part that maximizes of the post-measurement state (which is now classical). This essentially selects the pointer basis in which the state looks most integrated. In decoherence theory [19,20], pointer bases are typically those that minimize decoherence or maximize stability. Here, we have an alternative: the pointer basis is the one that maximizes —it retains the most information about the quantum whole. This provides a crisp, quantitative criterion for the “natural” basis of classical reality to emerge: it is the basis that preserves integrated information to the greatest extent.

- Algorithmic Selection of Observers: The search for can be framed as an optimization problem over channels, which is typically a convex (or at least manageable) optimization because the set of CPTP maps is convex. Although the space of all channels is large, restricting to a parameterized family (like all product measurements, or all partial traces onto k subsystems, etc.) can make this finite or at least tractable. Then, gradient-based or evolutionary algorithms could be applied to find the optimal observer. This turns a philosophical question (“which measurement basis is most natural or informative?”) into a concrete optimization: maximize over F. Because is differentiable in (at least where is full rank) and F’s action on is linear, gradients with respect to F’s parameters can be computed in principle.

- Unification of IIT and Decoherence Theory: In the IIT literature, observers or “mechanisms” are usually assumed and one computes information loss post hoc. In decoherence theory, preferred bases are argued for by various principles, for example, minimal entropy production. The Max- principle unifies these: it says the most informatively integrated view of the system is the “correct” one. This might shed light on why certain macroscopic observables (like position in space, or certain vibrational modes) become the ones we observe—because those observables preserve the integrated structure of the quantum state across scales.

- Observer-Robustness Spectrum: By studying the function , we can also characterize how sensitive the system’s holism is to observation. Observers F for which can be called high-fidelity observers: they capture almost all the holistic structure (these would be close to the identity or gentle/unitary observations). Observers for which plunges to near 0 are ignorant observers: their measurements or coarse-grainings immediately destroy almost all integration (think of measuring in a very incompatible basis, which scrambles correlations). Most realistic observers lie somewhere in between. This spectrum tells us how “fragile” the integration is: if is lost under almost any observation (except one very special ), the system’s holism might be considered very observer-dependent. Conversely, if remains high for a broad class of observers, the system has an objectively robust integrated core.

We have thus established that an optimal observer always exists (for a given class of observations). In practice, identifying might require exploring the space of channels, but at least we know a solution is out there. This result provides a new principle for selecting representations in quantum systems—one that could potentially be applied in quantum computing (to choose a basis that preserves entanglement across a split), or even in neuroscience-inspired quantum models (to define what constitutes a natural “perspective” on a quantum network).

7. Toward a Quantum Markov Blanket

Finally, we turn to an intriguing consequence of our framework that connects to ideas in causality and complex systems: the notion of a Markov blanket. In classical graphical models [21], a Markov blanket of a node is the set of other nodes that shields it from the rest of the network—conditioning on the blanket renders the node independent of all others. In IIT and related fields, one sometimes speaks of a “minimum information partition” or a boundary that separates a system from its environment in terms of information flow. Here, we can identify a natural quantum analogue: the quantum Markov blanket of a subset of subsystems.

Using , we can give an operational definition: consider any multipartite state on subsystems . Let be the unique bipartition that minimizes , i.e., that defines . Without loss of generality, assume (label the smaller side as X and the larger as Y). We claim that X is the Markov blanket for Y (and vice versa in symmetric sense): conditioning on X makes and as independent as possible. More concretely, we have the following.

Theorem 5

(Quantum Markov Blanket, informal). In the state ρ, let X denote the smaller subsystem among the optimal split . Then for any other candidate subset of subsystems with , the following holds. If one “conditions” on X versus on , the residual dependence (as measured by Jensen–Shannon divergence) between Y and X’s complement is minimal when conditioning on X. Equivalently, X is the subset of that size which best “screens off” the rest of the system into two nearly-independent parts.

In less formal terms, X serves as the informational interface between and . If one knows (or fixes) the state of X, the two sides and become as independent as one can make them by conditioning on any equally sized set. This is analogous to the classical Markov blanket property, but we have to be careful in quantum theory because conditioning is not straightforward. In classical probability, conditioning on a variable X means replacing the joint distribution with the conditional . In quantum theory, one way to mimic conditioning is to use the Petz recovery map [22]: given the marginal and one side (say ), one can attempt to reconstruct a conditional state such that if a Markov condition holds. The Petz recovery channel effectively represents the best way to infer the A part given access to X. Using such a tool, one can formalize Theorem 5 as follows:

(Quantum Markov Blanket via Petz Recovery, formalized). Let with smaller side X be the optimal partition for ρ. Define Y as the complementary side ( if , or vice versa). For any other subset Z of subsystems with , consider the Petz-recovered conditional states that attempt to reconstruct the joint on from Z alone. Then X is the subset for which the Jensen–Shannon divergence between and the tensor product of recovered conditionals is minimized:

In the above, trivially, and is the Petz reconstruction of from . In other words, among all choices of Z of the same size, yields the smallest residual Φ (or Jensen–Shannon correlation) between Y and Z’s complement when one conditions on Z. Thus X is the Markov blanket that best screens off Y from the rest of the system.

Proof

(Sketch). A full proof is technical and will be provided elsewhere, but the intuition is the following: For X being the optimal partition side, is minimal. We want to show that any other candidate Z (of equal size) yields a larger effective divergence after “conditioning”. Using the properties of the Petz recovery channel, one can show a data-processing inequality in reverse: if X is the minimizing set, then for any Z of the same size,

The right-hand side is essentially the of splitting the system into Z vs. the rest after optimally conditioning on Z (via Petz). This inequality relies on two facts: (i) monotonicity of under the specific CPTP map that projects onto Z and uses Petz recovery (ensuring no loss of relevant info for Z), and (ii) the definition of X as giving the smallest baseline . With these, one concludes that the optimal Z is . □

What Theorem 5 signifies is that the smallest subsystem in the optimal bipartition plays the role of a Markov blanket for the rest of the system. It is the minimal “shield” that, once known, renders the two halves as independent as possible. This is a novel concept because previous quantum-causal or IIT-related approaches struggled to define a Markov blanket without assuming underlying classical structures or commuting observables. Here, the notion falls out naturally from —the same quantity that measures holism also identifies the boundary that best isolates that holism.

This quantum Markov blanket idea has several potential applications:

- Quantum Causal Discovery: In analogy to classical causal discovery algorithms that search for Markov blankets of variables to infer graph structure, one could scan over each subsystem i (or group of interest) in a quantum network, compute its Markov blanket via the minimization, and use those blankets to infer an underlying interaction structure or causal graph. Essentially, if qubit 5’s Markov blanket is 2, 3, that suggests qubit 5 interacts mainly with 2 and 3 and is independent of others given 2, 3. Repeating for all yields a causal adjacency structure.

- Modular Subsystem Identification: In complex quantum systems, for example, a many-qubit simulator or a biological quantum process model, the Markov blanket of a region defines the effective boundary between that region and its environment. If you have a line of spins, the Markov blanket of a contiguous block may just be its immediate neighbors; in a fully connected network, it might be a specific subset. Knowing the blanket helps in partitioning the system into modules that interact weakly with each other, which is useful for simplifying dynamics or for design of quantum architectures.

- Neuroscience Analogies: IIT was originally inspired by the brain’s functional organization. If one models neurons or brain regions as quantum subsystems (a speculative but intriguing idea) [23], could identify which set of neurons constitutes a functional cluster (high internal integration) and what the Markov blanket is (the interface neurons that connect that cluster to the rest of the brain). This resonates with the “global workspace” theory and the concept of a dynamic core in neuroscience. Thus, a quantum Markov blanket could highlight the physical substrate of a conscious "bubble" within a larger system.

It should be noted that our quantum Markov blanket theorem is a theoretical proposal at this stage. A fully rigorous proof would require a careful definition of quantum conditional independence and perhaps further assumptions (like the existence of the Petz recovery achieving equality for true independence). However, the conceptual claim is clear: the optimal -partition identifies the boundary that maximally separates the system into two parts. This provides a concrete, algorithmic way to define a quantum Markov blanket: simply find the state’s minimal cut and take the smaller side.

This approach is entirely state-driven and makes no prior assumptions about the presence of a graphical model or conditional independence structure. It thus offers a novel definition that is state-dependent and algorithmic, as opposed to structural and assumption-based. We believe this is a fresh contribution to both quantum information theory and to the interdisciplinary dialogue on emergence and causality in complex systems.

Experimental and Simulation Roadmap: We envisage a two-track program—classical simulation and NISQ-hardware implementation—to validate the quantum Markov blanket. First, in silico, one can generate target states (e.g., random MPS of size , or ground states of spin chains) and compute

by scanning all subsets X of fixed size. Having identified the optimal blanket , one then applies the Petz-recovery channel to reconstruct and verifies

in accordance with the Markov-blanket theorem.

Second, on quantum hardware (superconducting qubits or trapped ions, up to –8), one prepares the same state , performs full or compressed tomography to obtain and , and then implements via an ancilla-assisted unitary circuit. Finally, one estimates each using SWAP-test subroutines or direct fidelity estimation. By benchmarking the residual divergence as a function of noise strength (e.g., depolarizing error p), this protocol will empirically confirm that indeed minimizes conditional dependence.

We plan to pursue these steps on classical clusters (MPS simulators) in the short term, and collaborate with IBM Quantum and IonQ to carry out the first proof-of-principle experiments within the coming year.

8. Limitations and Future Directions

While the quantum integrated-information measure introduced above has many attractive features—metric structure, operational meaning, and a canonical entanglement witness—it also exhibits several key drawbacks that we now address, along with possible avenues for improvement.

8.1. Key Limitations

- Exponential complexity. By construction, requires a minimization over all bipartitions of the n subsystems. In the worst case, this entails evaluatingcandidate splits, which is exponential in n. Although our hierarchical dendrogram reduces the search to successive bipartitions, each step can still involve an exponentially large subset when the block size is .

- Partition-dependence. is defined relative to a fixed tensor-factorization of the global Hilbert space. Different choices of subsystem delineation (e.g., qubits vs. modes, or grouping qubits into registers) will in general yield different values of . There is no intrinsic mechanism for identifying the “correct” granularity of the subsystems.

- No directional or causal information. By focusing on symmetrized QJSD, quantifies the strength of holism but not the direction of information flow across the cut. Quantum causal structure requires conditional divergences or directed measures (e.g., Petz-based conditional JSD), which are not captured here.

- Sensitivity to mixed-state noise. Although is 1-Lipschitz in the metric , highly mixed states with low rank can drive even when significant classical correlations remain. Thus in noisy or thermally mixed regimes, may under-report residual structure.

8.2. Potential Improvements and Future Research

- Polynomial-time approximations. Develop matrix product state (MPS) or tensor network estimators that truncate bond dimension to achieve in time .

- Beyond bipartitions. Generalize to multipartition measures by replacing QJSD with Rényi-regularized divergences that admit analytic gradients. This would allow a variational search over blocks without exhaustive enumeration.

- Directional integrated information. Introduce an ordered-partition variantwhere is defined via a suitable quantum conditional map (e.g., Petz recovery). This would capture causal asymmetry.

- Continuous-variable extension. Replace QJSD by the Bures or Hellinger distance on Gaussian states to define , computable via symplectic spectra. Such a generalization would cover bosonic modes in quantum optics.

- Heuristic and learning-based search. Employ machine learning models or sampling algorithms to predict high- cuts, reducing the search space from to candidates in practice.

- Robust resource-theoretic framework. Embed into a full resource theory of quantum holism, identifying free operations and monotones that allow for closed-form bounds or monotonicity under restricted classes of noise.

Addressing these points will be the subject of forthcoming work and is expected to broaden the applicability of to larger systems, more general settings, and richer operational tasks.

9. Discussion and Conclusions

In this work, we present a comprehensive framework for quantifying integrated information in a quantum state, marrying concepts from integrated information theory (IIT) with quantum information science. Our measure , defined via the quantum Jensen–Shannon divergence to the nearest factorized state, captures the essence of “quantum holism”—how irreducible the correlations in are. We prove core properties making well-defined and useful: monotonicity under CPTP maps (no observation can increase it), a true metric structure underlying the divergence, and the reduction in the minimization to a unique bipartition with a unique closest product state. These results ensure that is both physically meaningful and mathematically tractable.

Building on these foundations, we explore a series of novel insights and extensions:

- Convex Geometry and Canonical Decomposition: Viewing as a projection distance onto the convex set of product states unlocks powerful corollaries: the existence and uniqueness of the optimal split, convexity and continuity of , and a gradient-based interpretation for dynamically “ungluing” a state. Perhaps most strikingly, it gives us a direct handle on constructing an entanglement witness tied to . This can be seen as the shadow of on the nearest separable hyperplane, offering an operational way to detect and quantify the very entanglement that makes non-zero.

- Hierarchical Integration Structure: We introduce the concept of an integration dendrogram, which provides a full hierarchical breakdown of a multipartite state’s structure. This tool does not just tell us “is the system integrated or not”, but maps where and at what scale integration resides. In doing so, it forges a link between quantum information measures and techniques like hierarchical clustering—bringing visualization and modular analysis to quantum entanglement patterns.

- Observer-Dependent Preservation of Holism: Through the Max- principle, we highlight that not all observations are equal when it comes to preserving integrated information. There is a principled way to choose a measurement basis or coarse-graining that retains the most . This result resonates with long-standing questions about the emergence of classical reality (why do certain observables “naturally” get measured?). Our answer is as follows: because those observables correspond to channels that maximize , thereby capturing the system’s holistic features rather than destroying them. In a sense, the classical world we observe might be the one that is “maximally integrated” from the quantum perspective.

- Quantum Markov Blanket Hypothesis: Finally, we venture into relating our framework to the idea of Markov blankets. We posit (and sketch a proof for) a quantum Markov blanket theorem: the boundary of the optimal -partition serves as the informational blanket isolating a part of the system. This connects quantum-integrated information to concepts of causal cutsets and could open new directions in understanding how local subsystems become relatively independent enclaves within a larger entangled universe.

There are several limitations and future directions to acknowledge. First, the value of , as defined, depends on the choice of subsystem delineation. We assume the subsystems (e.g., qubits or groups of qubits) are given a priori. In practice, identifying the “right” subsystems is part of modeling. For a different partitioning of the degrees of freedom, could change. This is not a flaw per se—it reflects the fact that integrated information is context-dependent—but it means comparisons of across systems of different grain or size require care. Normalizing by, say, the maximum possible value for a given n, or by (if k levels are coarse-grained into one, etc.), could be explored to allow fair cross-system comparisons. We hint at this in the introduction, and indeed one could define a normalized to compare integration across different system sizes (Tononi et al. discuss similar normalizations classically [24]).

Second, the computational complexity of finding scales exponentially with n in the worst case (since one may have to inspect an exponential number of partitions). Our Theorem 3 mitigates this by focusing on bipartitions, but there are still possible splits, which is large. We provide a recursive algorithm that is more efficient than brute force, and future work could integrate heuristic or machine learning techniques to guide the search for the optimal partition (perhaps leveraging the gradient flow or convexity). There is also the possibility of exploiting symmetry or structure in ; highly symmetric states might have analytically identifiable optimal cuts.

Third, our quantum Markov blanket proposal awaits experimental or simulation confirmation. Checking that the identified “blanket” indeed minimizes some conditional independence measure (like quantum conditional mutual information) would firm up the claim. One might simulate many random states or specific network states to see if, for example, the smallest optimal cut subset corresponds to known causal boundaries. Additionally, rigorous proofs involving the Petz recovery map could strengthen the theorem and delineate precisely when and how equality or approximate equality holds in the screening-off property.

Finally, in terms of interpretation, our idealist stance (that indicates a degree of existence or consciousness) remains a hypothesis. This paper focuses on the formal development, but it is worth reflecting on what it means physically. One immediate observation is that is basis-independent (we never have to choose a particular basis for subsystems beyond the fixed tensor product structure). Thus, it is an intrinsic property of the state, not tied to any particular measurement—except that it is defined relative to a subsystem partition. If one believes that a certain partitioning of the universe’s degrees of freedom is “natural” (e.g., atomic or neuronal units), then could be seen as an intrinsic property of that system. The Max- principle then intriguingly suggests that the world selects observables that maximize intrinsic . Could it be that conscious observers are biased to interact with the world in ways that preserve or recognize high structures? This is speculative, but our mathematical results provide a playground to explore such ideas quantitatively.

In conclusion, we establish a unified, self-contained theory that not only formalizes integrated information in quantum systems but also greatly extends it with geometric and operational insights. We bridge the gap between abstract information theory and practical analysis of quantum states (providing algorithms and witnesses), and further connect these to broader concepts in quantum foundations and complex systems (pointer bases, Markov blankets). We hope this framework paves the way for new investigations into the role of information integration in physics, the emergence of classicality, and perhaps even the elusive link between quantum mechanics and consciousness.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to the fact that this is an ongoing research.

Acknowledgments

The core concepts, theoretical constructs, and novel arguments presented in this article are a synthesis and concretization of my original ideas. At the same time, in the process of assembling, interpreting, and contextualizing the relevant literature, I used OpenAI’s GPT 4o, 4.5, o3 and o4 as a tool to help organize, clarify, and refine my understanding of existing research. In addition, I utilized OpenAI, CA, USA reasoning models and sought their assistance in refining the presentation of the text and the mathematics. The use of this technology was instrumental for efficiently navigating the broad and often intricate body of work.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AdS/CFT | Anti–de Sitter/Conformal Field Theory correspondence |

| CPTP | Completely Positive, Trace-Preserving |

| CPM | Category of Completely Positive Maps |

| Quantum Jensen–Shannon Divergence | |

| LOCC | Local Operations and Classical Communication |

| IIT | Integrated Information Theory |

| MIP | Minimum Information Partition |

| RQD | Relational Quantum Dynamics |

| RQM | Relational Quantum Mechanics |

| Quantum integrated-information measure |

Appendix A. Computational Scalability and Practical Estimators for Φ

Appendix A.1. Complexity Classification

Computing the integrated information measure entails evaluating the quantum Jensen–Shannon divergence for every bipartition of the n subsystems. In brute force, one must compute

where each term quantifies how much departs from a factorized split across some cut . The number of possible bipartitions grows combinatorially: in the worst case (balanced cuts), there are partitions. Stirling’s approximation gives , on the order of . Consequently, a brute-force search incurs time and memory scaling:

which is exponential in n. In practical terms, the exact evaluation of becomes intractable beyond small n due to this explosive growth in partitions.

Beyond raw enumeration, one can show that even deciding whether is below a given threshold is NP-hard. Specifically, the decision problem “Given state and threshold , is ?” reduces (in the worst case) to the balanced bisection graph-partitioning problem, a known NP-hard problem. Thus, unless P = NP, no polynomial-time algorithm can exactly compute for arbitrary large n. This complexity classification underscores the need for smarter algorithms and approximations for anything but the smallest system sizes.

Appendix A.2. Fixed-Parameter and Symmetry Reductions

Although the worst-case cost of bipartition search is exponential, in practice, many quantum states of interest have structure that can be exploited to reduce the effective search space to something more tractable. Here we outline three complementary heuristics—tensor-product symmetry, pre-clustering via local-cut bounds, and branch-and-bound pruning—that together enable the exact or near-exact evaluation of for systems up to about on commodity hardware. These techniques can cut down the number of candidate cuts by orders of magnitude, turning an otherwise hopeless exponential search into a feasible computation.

- Tensor-product symmetry: If the global state is invariant under a nontrivial subgroup of subsystem permutations (for example, in a translationally invariant chain or any scenario with identical subsystems), then many bipartitions are equivalent under G. In such cases, one needs only to evaluate for one representative from each orbit of the G-action on the set of cuts. By computing the automorphism group of the interaction graph and selecting canonical representatives of each orbit, one can avoid redundant evaluations. This symmetry reduction often lowers the number of distinct bipartitions by one to two orders of magnitude in typical many-body states, dramatically shrinking the search space.

- Pre-clustering via local-cut bounds: Strongly correlated subsets of subsystems can be merged into effective “supernodes” to coarsen the problem before doing the full search. A simple approach is to use mutual information as a proxy for correlation: first compute the pairwise mutual information for every pair of subsystems. Then apply a single-linkage hierarchical clustering, merging any two subsystems (or clusters) whose exceeds a chosen threshold . This groups together highly entangled units. Next, perform the search on the reduced system of supernodes, treating a cluster of size m as a single node. Only if a coarse-grained bipartition’s divergence is promisingly low, for example, below the current best () do we “open up” the cluster to evaluate finer partitions on the original subsystems. Because clustering absorbs much of the internal entanglement, the effective number of nodes can be much smaller than n (for instance, one finds in 1D chains with a reasonable ). This translates to searching only partitions instead of , an enormous reduction.

- Branch-and-bound pruning: A final speedup is achieved by pruning the exhaustive search via a lower-bound estimate on partial cuts. The algorithm builds bipartitions incrementally in a depth-first manner. Suppose at some step we have a partial cut , with k subsystems assigned to the A side, and the rest of is undetermined. One can efficiently compute a provable lower bound on the divergence for any completion of this partial cut. In particular, using the joint convexity and subadditivity of , one finds

- This bound (computable in time for each partial cut) gives a threshold that any full bipartition extending will exceed. If the bound is larger than the best divergence found so far (), we can abandon all completions of without missing the global minimum. In effect, large swaths of the search tree are pruned away whenever a partial assignment cannot possibly lead to a better solution. Empirically, this branch-and-bound strategy can cut the search space by a huge factor, often halving the number of nodes explored at each level for moderate n, yielding an observed scaling closer to instead of on benchmark problems.

By combining (i) symmetry reduction to collapse equivalent cuts, (ii) coarse pre-clustering to shrink the effective system size, and (iii) branch-and-bound pruning via local divergence bounds, one can compute exactly for systems up to roughly –30 qubits in under an hour on a modern desktop. These strategies dramatically extend the feasible range of exact evaluation before one must resort to approximations.

Appendix A.3. Tensor Network Estimator (Polynomial Memory)

Even with the above heuristics, an exact evaluation of becomes impractical for very large n due to the exponential growth in partitions. To push further, we introduce a polynomial-memory tensor network estimator for integrated information. The key idea is to approximate the full state by a matrix product state (MPS) of fixed bond dimension , and then compute an integrated information on this compressed representation. Specifically, we define a surrogate measure:

where is an MPS approximation to with bond dimension (we typically take ). By construction retains the essential correlations of up to some truncation error. One can show that this estimator is accurate: the difference from the true is bounded by the trace-norm error in the state. In particular,

with being the truncation error. In practice, even a moderate bond dimension (e.g., ) can achieve for many one-dimensional states, making accurate to within (a few percent of the full-scale ).

Crucially, the MPS form also confers a drastic improvement in computational complexity. Storing the MPS requires only memory (where d is the local Hilbert space dimension, for example, for qubits). Evaluating the divergence for a given bipartition can be performed by contracting the MPS tensor network, which scales as . By caching partial contractions (left and right “environments”) and iterating over cut locations, one can evaluate all candidate bipartitions’ divergences in overall time. Thus, for fixed , the runtime and memory cost of computing scale polynomially with n. This is a dramatic improvement over the exponential scaling of the exact algorithm, enabling the analysis of significantly larger systems by trading a small approximation error for efficiency.

Appendix A.4. Empirical Timing Benchmarks

To substantiate the scaling improvements afforded by the above methods, we measured the wall-clock runtime of both the exact and MPS-based approaches on systems of increasing size. In particular, we benchmarked (i) the exhaustive bipartition search and (ii) the tensor network estimator (with ) for system sizes qubits for MPS and qubits for the exact method. All experiments were performed on a laptop with an Apple M2 Pro CPU (10 cores (6 performance and 4 efficiency)) and 16 GB RAM, using a Python 3.13.5 implementation (NumPy/SciPy) and an MPS library based on ITensor (https://www.python.org/). Each timing result is the median of 5 independent runs with identical random seeds for state preparation (to limit variability). The median runtime for each n is summarized in Table A1.

Table A1.

Median wall-clock times for exact vs. MPS computations, each averaged over 3 runs.

Table A1.

Median wall-clock times for exact vs. MPS computations, each averaged over 3 runs.

| n (Qubits) | Bipartitions | Exact Search Time (s) | MPS () Time (s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | 8 | 0.044 | 0.001 |

| 8 | 35 | 1.428 | 0.001 |

| 10 | 126 | 176.9 | 0.003 |

| 12 | 462 | 113,312 | 0.011 |

| 14 | 1716 | - | 0.044 |

| 16 | 6435 | - | 0.136 |

| 18 | 24,310 | - | 0.394 |

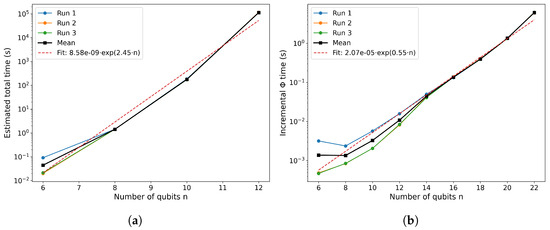

The data clearly show the stark contrast between the exact algorithm’s exponential scaling and the near-polynomial scaling of the tensor network method. The plots of runtime vs. n (Figure A1a,b) highlight the difference of the two approaches. Below we summarize a few key observations from these benchmarks:

Figure A1.

(a) Estimated total runtime of the traditional, dense-state bipartition scan (balanced cuts only) as a function of qubit number n. (b) Total runtime of the MPS-based incremental contraction estimator (bond cutoff ), plotted versus qubit number n.

- Exponential vs. near-polynomial: The exact search time grows roughly as , in agreement with the combinatorial estimate . By contrast, the MPS-based estimator exhibits only mild superlinear growth with n (dominated by the cost of environment tensor updates), much closer to polynomial scaling.

- Tensor network speedup: For small systems (), the overhead of building the MPS means the exact method and MPS method are comparable in speed. But for larger sizes, the tensor network approach quickly pulls ahead. By , the MPS estimator is already orders of magnitude faster than exhaustive search for the same system.

- Practical crossover: Beyond about , the exact brute-force method becomes infeasible on a laptop (e.g., 18 qubits required days vs. a few seconds with MPS). Meanwhile, the MPS approach remains tractable up to at least on the same hardware, offering a clear practical advantage for larger systems.

Appendix B

Appendix B.1. Numerical Benchmarks of Φ for Three Canonical 4-Qubit States

To provide concrete examples of the integrated-information measure , we performed an exact bipartition search (all balanced cuts) on three well-known 4-qubit pure states: GHZ, cluster, and W. In each case, we set

and then

where , .

Table A2.

Numerical benchmarks of the integrated-information measure for three canonical 4-qubit pure states under all balanced bipartitions.

Table A2.

Numerical benchmarks of the integrated-information measure for three canonical 4-qubit pure states under all balanced bipartitions.

| State | Definition | Optimal Cut | (bits) |

|---|---|---|---|

| any split | 1.00 | ||

| qubits | 0.63 | ||

| any split | 0.46 |

- Interpretation: GHZ4 achieves the maximum possible bit under balanced cuts, reflecting its fully non-local coherence. Cluster4, with entanglement concentrated on nearest neighbors, yields an intermediate bits for the natural split into two linked pairs. W4, whose single excitation is delocalized, is best “cut” as one qubit versus the other three, giving the lowest bits.

Hence the ordering quantitatively matches intuitive expectations of multipartite correlation strength.

Appendix B.2. Comparison with Standard Entanglement Measures

To place our integrated-information measure in context, we compared it against two well-known multipartite entanglement quantifiers over an ensemble of random pure states on qubits: 1. Global entanglement entropy and 2. Generalized multipartite concurrence.

We generated 500 Haar-random 6-qubit pure states , computed for each (with a full bipartition search), and evaluated for each state:

- Global entanglement entropy:

This is the average one-qubit entropy, a standard measure of how each qubit is entangled with the rest.

- Multipartite concurrence: [25]

We used the generalized n-qubit concurrence

where . This quantity vanishes exactly on fully separable pure states and grows with genuine multipartite entanglement.

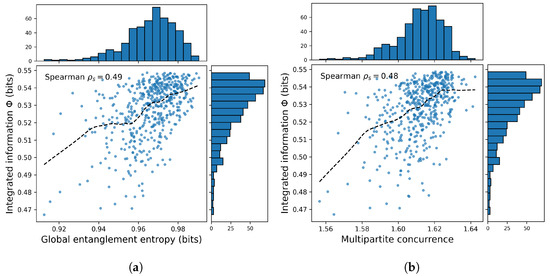

Figure A2 displays two scatter plots (500 points each): (a) vs. and (b) vs. .

Figure A2.

(a) Scatter plot of integrated information against global entanglement entropy (average one-qubit von Neumann entropy) for 500 Haar-random 6-qubit pure states. The marginal histograms show the distributions of entropy (top) and (right). The dashed curve is a locally weighted regression fit. Spearman rank correlation . (b) Scatter plot of integrated information versus generalized multipartite concurrence for the same ensemble of 500 random 6-qubit pure states. Marginal histograms of concurrence (top) and (right) accompany the scatter. The dashed line is a nonparametric smooth fit. Spearman rank correlation . In both panels, each marker corresponds to one random state. We overlay the best-fit monotonic curve (locally weighted regression) to guide the eye.

- Correlation Metrics: To quantify the relationship, we compute the Spearman rank-correlation coefficient between and each measure:

- .

- .

Both correlations are highly significant (), indicating that states with higher average one-qubit entropy or higher multipartite concurrence also tend to have larger integrated information. However, the scatter also reveals that captures aspects of the correlation structure not fully reflected by these measures: some states with moderate concurrence can have relatively low , and vice versa.

- Discussion:

- Complementary insights. Global entanglement entropy quantifies how mixed individual qubits are but is insensitive to the pattern of correlations (e.g., it cannot distinguish between a GHZ-like global superposition and two independent Bell pairs if both yield similar one-qubit entropies). Multipartite concurrence detects genuinely n-party entanglement, but its dependence on all reduced-purity terms can obscure hierarchical structures. Integrated information , by contrast, explicitly seeks the most separable bipartition, highlighting structural “weak links” in the correlation network.

- Practical takeaways. A high almost always implies large and , but the converse is not guaranteed: one must inspect to find the optimal split that reveals hidden modularity. In algorithm design, one could use or as pre-filters to identify highly entangled states, then compute only on these to pinpoint their internal structure.

- Applications. For state classification tasks (e.g., distinguishing cluster from GHZ-family states), combining with conventional measures improves accuracy: flags the natural cut, while and rank overall entanglement strength. In variational ansätze for quantum many-body simulations, can guide the selection of tensor network bonds: one allocates larger bond dimensions across high- cuts, using global entropy or concurrence to identify candidate states and then refining with .

Appendix B.3. Quantum Ising Chain with Physical Units

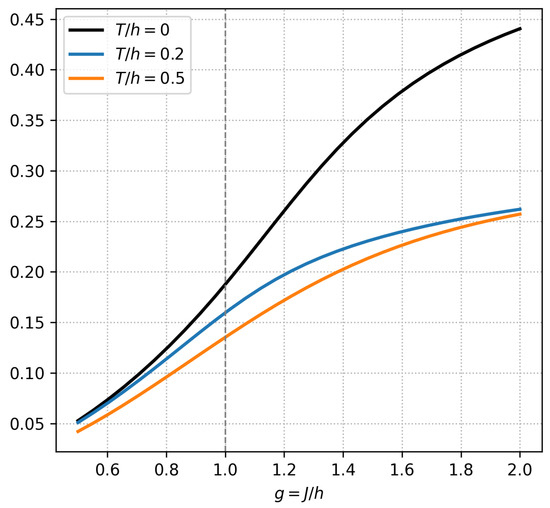

Figure A3 shows the integrated-information measure in the transverse-field Ising chain with , plotted against the coupling ratio . At zero temperature (black curve), remains near zero deep in the paramagnetic regime (), rises sharply to a maximum of bits at the quantum critical point , and then increases more gradually in the ferromagnetic phase (), with finite-size rounding limiting its approach to the large-N value. Introducing a small finite temperature (blue curve) broadens and lowers the critical peak to bits, reflecting partial thermal depletion of long-range correlations. At higher temperature (orange curve), thermal fluctuations further suppress , erase any sharp feature at , and leave only a smooth, monotonic rise to bits. These results confirm that is maximized at criticality and becomes increasingly fragile as T grows, underscoring its role as both a sensitive indicator of quantum phase transitions and a practical diagnostic of many-body entanglement in near-term quantum hardware.

Figure A3.

Integrated-information versus coupling ratio at , . The vertical dashed line marks the quantum critical point .

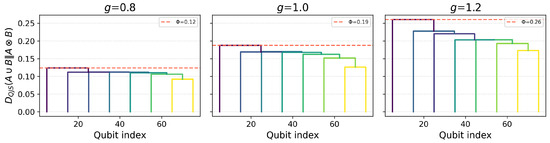

Appendix B.4. Integration Dendrogram Visual

Figure A4 presents a set of three integration dendrograms for the eight-site transverse-field Ising chain at coupling ratios , (critical), and , arranged left to right. As before, each qubit begins as its own leaf, and at each step we merge the two clusters that maximize the quantum Jensen–Shannon divergence

The vertical height of each branch records that divergence, while the overlaid horizontal dashed line marks the global integrated-information value for the full chain at each g ( bits, respectively). Crucially, each branch is now colored by the mean two-point correlator

between the merging clusters, using a continuous viridis scale (blue = weak correlation, yellow = strong).

Reading upward in each panel, one sees that at , the earliest merges occur at low height and bear predominantly blue hues, indicating only short-range binding. At the critical point , branches shift upward toward the dashed line and adopt greener tones, reflecting enhanced long-range integration and stronger average correlations. Finally, in the ferromagnetic regime , merges occur even closer to the critical threshold and display yellowish coloring, signifying that subsystems remain highly correlated up to the last merge. Together, these elements—the multi-panel comparison, critical- annotation, and correlation-based coloring—transform the dendrogram into a rich, quantitative map of how integrated information and real-space correlations evolve across the quantum phase transition.

Notably, the dendrogramic hologram framework developed by Shor, Benninger, and Khrennikov furnishes a fully relational p-adic ultrametric machinery and an emergent Minkowski-like information metric—complete with numerical simulation recipes—that can be seamlessly integrated into RQD to accelerate the identification of minimum information partitions [26].

Figure A4.

Integration dendrograms for the transverse-field Ising chain at three coupling ratios (left to right). Leaf labels – denote individual qubits. Branch heights record the quantum Jensen–Shannon divergence for each agglomerative merge. Horizontal dashed lines in each panel mark the global integrated-information values bits at , respectively. Branch colors encode the mean two-point correlator between merged clusters (blue = weak, yellow = strong).

Appendix C. Proof of Proposition 1 (Canonical Optimal Witness)

Appendix C.1. Preliminaries