Effects of Smartphone Use on Posture and Gait: A Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

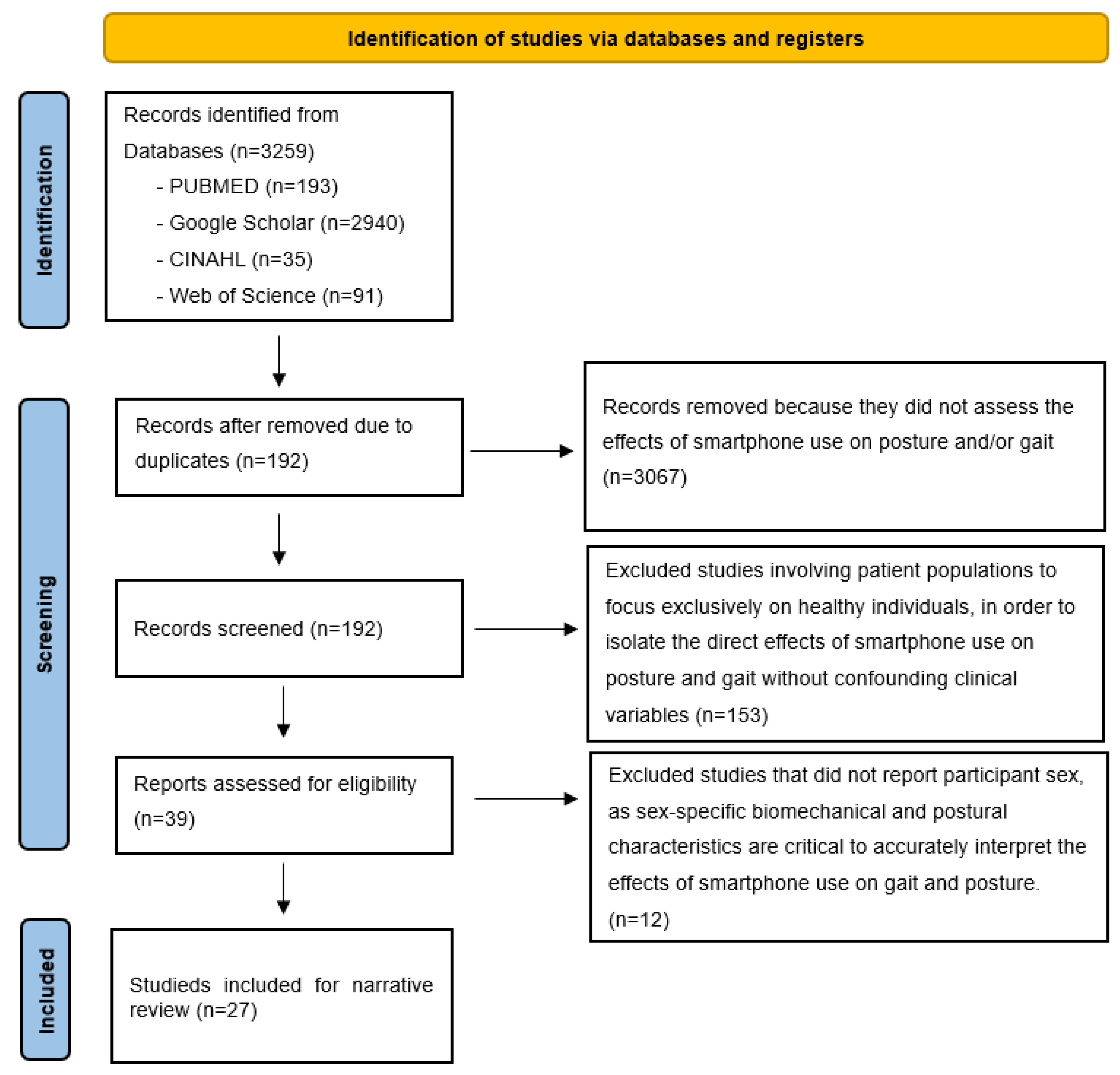

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

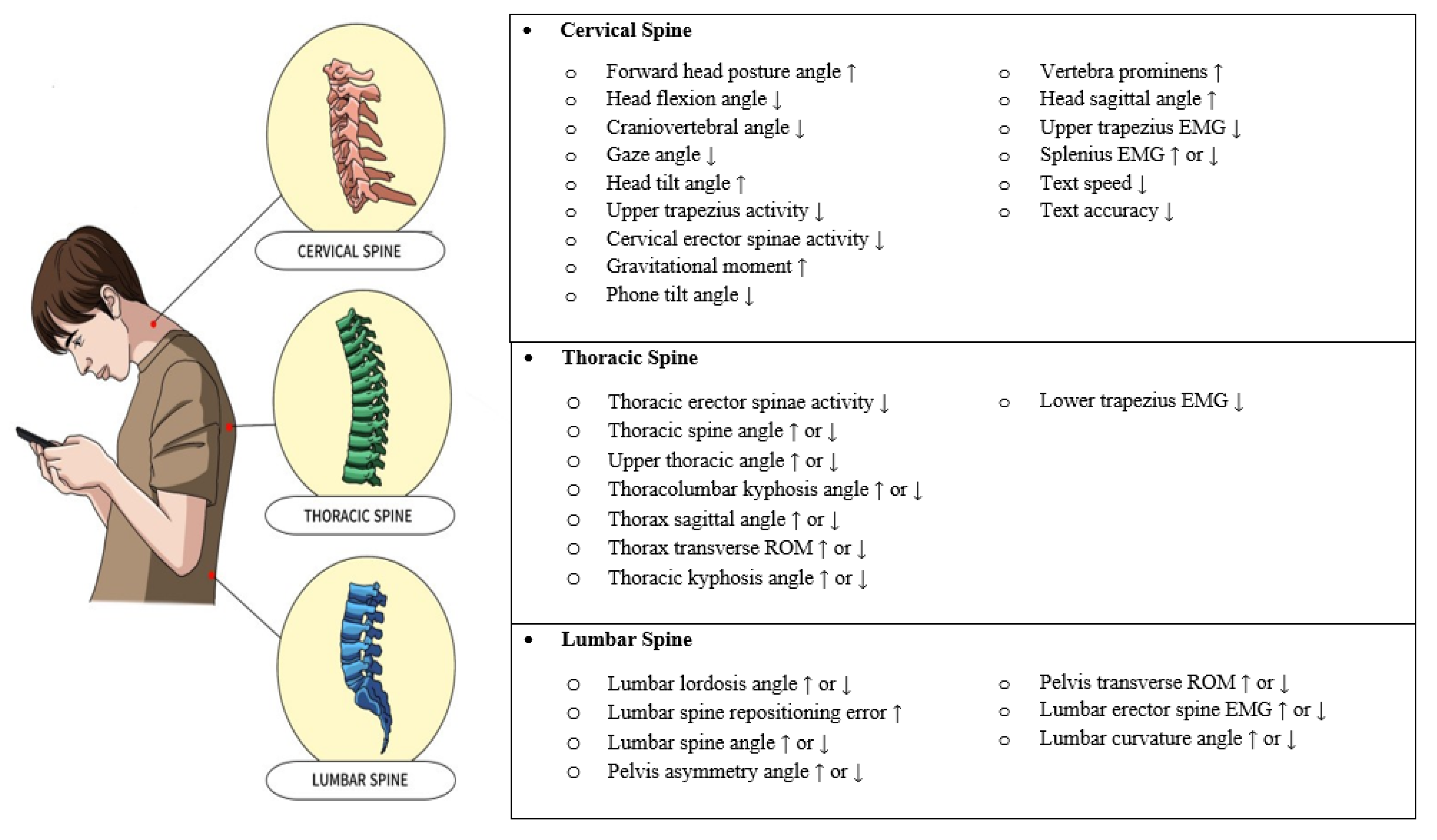

4.1. Effect of Smartphone Use on Static Posture

4.1.1. Effect of Smartphone Use on Cervical Spine Posture

4.1.2. Effect of Smartphone Use on Thoracic Spine Posture

4.1.3. Effect of Smartphone Use on Lumbar Spine Posture

4.1.4. Effect of Smartphone Use on Muscle Activation and Muscle Fatigue

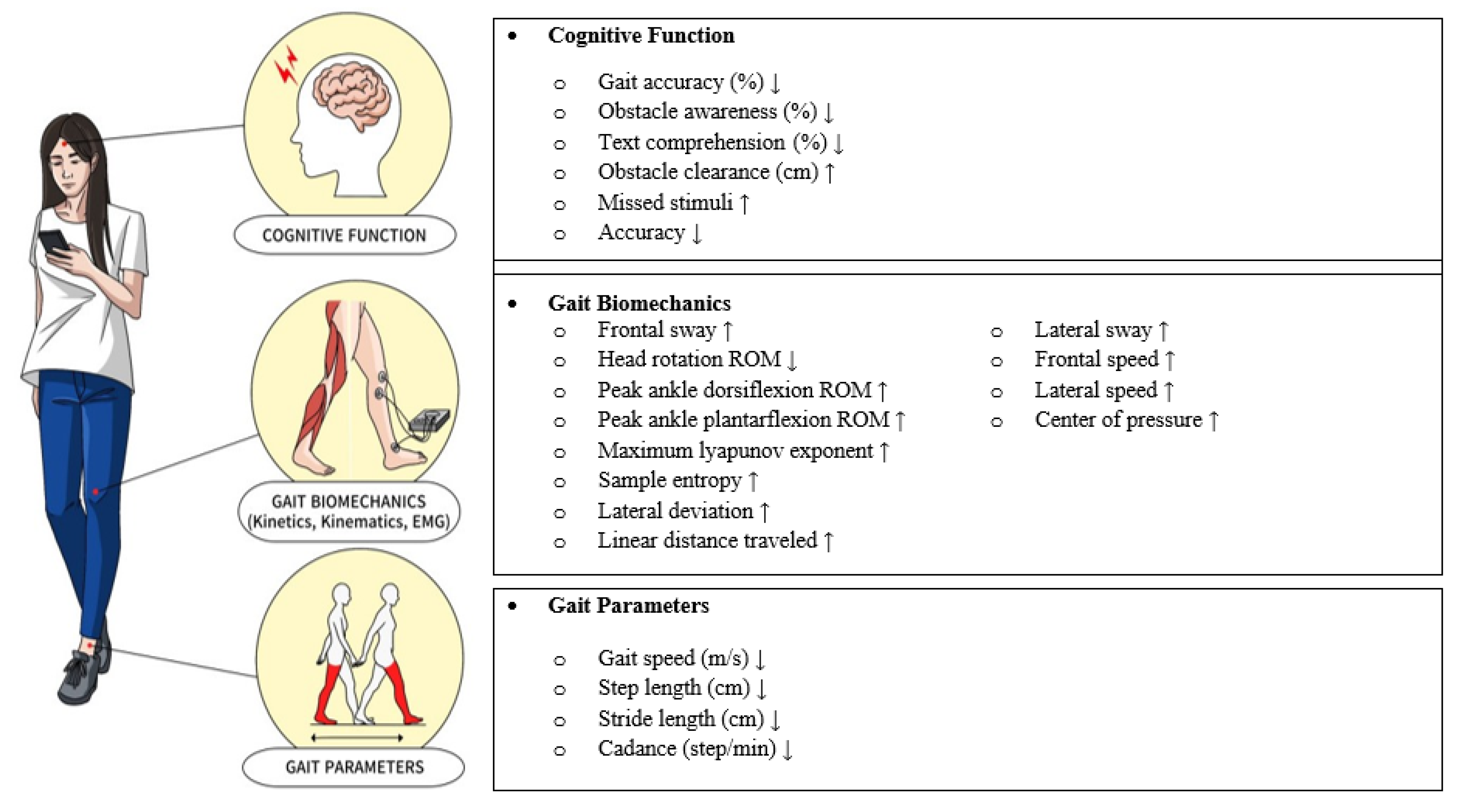

4.2. Smartphone and Gait

4.2.1. Effect of Smartphone Use on Walking Speed

4.2.2. Effect of Smartphone Use on Gait Biomechanics

4.2.3. Effect of Smartphone Use on Gait Parameters

4.2.4. Effect of Smartphone Use on Cognitive Function

4.3. Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FHP | Forward head posture |

| EMG | Electromyography |

| VAS | Visual analog scale |

| VP | Vertebra prominens |

| GN | Gaze neutral |

| S1H | Smartphone one-handed |

| S2H | Smartphone two-handed |

| CES | Cervical erector spinae |

| UT | Upper trapezius |

| B | Bimanual |

| AF | Asymmetric finger |

| S | Single-handed |

| AT | Asymmetric thumb |

| NF | Neck flexion |

| HF | Head flexion |

| GA | Gaze angle |

| VD | Viewing distance |

| TES | Thoracic erector spinae |

| LT | Lower trapezius |

| APDF | Amplitude probability distribution function |

| ROM | Range of motion |

| PPT | Pressure pain threshold |

| VT | Vertical |

| AP | Anteroposterior |

| ML | Mediolateral |

| NW | Normal walking |

| WLP | Walking while looking at the phone |

| WLLLP | While looking at the phone using one hand |

| WTP | Walking while talking on phone |

| WM | Walking while listening to music |

| RF | Rectus femoris |

| VM | Vastus medialis |

| TA | Tibialis anterior |

| GA | Gastrocnemius |

| BF | Biceps femoris |

| GM | Gluteus medius |

| TUG | Timed up and go |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| TEXT | Texting |

| TALK | Talking |

| OC | Obstacle crossing |

| COM | Center of mass |

| CC | Control |

| ICC | Individual conversation |

| GC | Gaming |

| GCC | Group conversation |

References

- Chen, Y.J.; Hu, C.Y.; Wu, W.T.; Lee, R.P.; Peng, C.H.; Yao, T.K.; Chang, C.M.; Chen, H.W.; Yeh, K.T. Association of smartphone overuse and neck pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Postgrad. Med. J. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.L.; Chen, K.H.; Cheng, Y.C.; Chang, C.C. Field Study of Postural Characteristics of Standing and Seated Smartphone Use. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Y.; Szeto, G.P.; Dai, J.; Madeleine, P. A comparison of muscle activity in using touchscreen smartphone among young people with and without chronic neck-shoulder pain. Ergonomics 2016, 59, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.E.; Kim, J.W.; Jee, Y.S. Relationship between smartphone addiction and physical activity in Chinese international students in Korea. J. Behav. Addict. 2015, 4, 200–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarraf, F.; Varmazyar, S. Comparing the effect of the posture of using smartphones on head and neck angles among college students. Ergonomics 2022, 65, 1631–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eitivipart, A.C.; Viriyarojanakul, S.; Redhead, L. Musculoskeletal disorder and pain associated with smartphone use: A systematic review of biomechanical evidence. Hong Kong Physiother. J. 2018, 38, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parr, N.D.; Hass, C.J.; Tillman, M.D. Cellular phone texting impairs gait in able-bodied young adults. J. Appl. Biomech. 2014, 30, 685–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, W.; Choi, S.; Han, H.; Shin, G. Neck Muscular Load When Using a Smartphone While Sitting, Standing, and Walking. Hum. Factors 2021, 63, 868–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowley, P.; Vuillerme, N.; Samani, A.; Madeleine, P. The effects of walking speed and mobile phone use on the walking dynamics of young adults. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.L.; Nguyen, H.T. User walking speed and standing posture influence head/neck flexion and viewing be8.havior while using a smartphone. Healthcare 2023, 11, 3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.L.; Chan, Y.C.; Alexander, H. Gender differences in neck muscle activity during near-maximum forward head flexion while using smartphones with varied postures. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 12994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshiki, S.; Tatsumi, H.; Tsutsumi, K.; Miyazaki, T.; Fujiki, T. Effects of smartphone use on behavior while walking. Urban Reg. Plan. Rev. 2017, 4, 138–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Anna, C.; Schmid, M.; Conforto, S. Linking head and neck posture with muscular activity and perceived discomfort during prolonged smartphone texting. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2021, 83, 103134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samaan, M.N.; Elnegmy, E.H.; Elnahhas, A.M.; Hendawy, A.S. Effect of prolonged smartphone use on cervical spine and hand grip strength in adolescence. Int. J. Multidiscip. Res. Dev. 2018, 5, 49–53. [Google Scholar]

- Brühl, M.; Hmida, J.; Tomschi, F.; Cucchi, D.; Wirtz, D.C.; Strauss, A.C.; Hilberg, T. Smartphone use-influence on posture and gait during standing and walking. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Shin, G. Head flexion angle when web-browsing and texting using a smartphone while walking. Appl. Ergon. 2019, 81, 102884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Lee, D.; Park, J. Effect of the cervical flexion angle during smartphone use on muscle fatigue of the cervical erector spinae and upper trapezius. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2015, 27, 1847–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapanya, W.; Puntumetakul, R.; Swangnetr Neubert, M.; Boucaut, R. Influence of neck flexion angle on gravitational moment and neck muscle activity when using a smartphone while standing. Ergonomics 2021, 64, 900–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eardley, R.; Roudaut, A.; Gill, S.; Thompson, S.J. Investigating how smartphone movement is affected by body posture. In Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Montreal, QC, Canada, 21–26 April 2018; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.F.; Szeto, G.; Madeleine, P.; Tsang, S. Spinal kinematics during smartphone texting—A comparison between young adults with and without chronic neck-shoulder pain. Appl. Ergon. 2018, 68, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.H.; Jung, M.H.; Yoo, K.T. An analysis of the activity and muscle fatigue of the muscles around the neck under the three most frequent postures while using a smartphone. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2016, 28, 1660–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuchi, C.A.; Fukuchi, R.K.; Duarte, M. Effects of walking speed on gait biomechanics in healthy participants: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst. Rev. 2019, 8, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pakdee, S.; Sengsoon, P. Changes in gait pattern during smartphone and tablet use. Iran. Rehabil. J. 2020, 18, 475–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alapatt, L.J.; Peel, N.M.; Reid, N.; Gray, L.C.; Hubbard, R.E. The effect of age on gait speed when texting. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schabrun, S.M.; van den Hoorn, W.; Moorcroft, A.; Greenland, C.; Hodges, P.W. Texting and walking: Strategies for postural control and implications for safety. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e84312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasovsky, T.; Lanir, J.; Felberbaum, Y.; Kizony, R. Mobile phone use during gait: The role of perceived prioritization and executive control. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruyneel, A.V.; Duclos, N.C. Effects of the use of mobile phone on postural and locomotor tasks: A scoping review. Gait Posture 2020, 82, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Sun, Y.; Lang, C.; Wen, Y. The impact of using mobile phones on gait characteristics: A narrative review. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 5783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.H.; Lo, O.Y.; Kay, T.; Chou, L.S. Concurrent phone texting alters crossing behavior and induces gait imbalance during obstacle crossing. Gait Posture 2018, 62, 422–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- In, T.S.; Jung, J.H.; Jung, K.S.; Cho, H.Y. Spinal and pelvic alignment of sitting posture associated with smartphone use in adolescents with low back pain. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.M.; Kang, S.Y.P.; Lee, S.G.P.; Jeon, H.S.P. The effects of smartphone gaming duration on muscle activation and spinal posture: Pilot study. Physiother. Theory Pract. 2017, 33, 661–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.O.; Kang, M.H.; Kim, J.S.; Oh, J.S. The effects of gait with use of smartphone on repositioning error and curvature of the lumbar spine. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2015, 27, 2507–2508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Choi, S.; Kim, M.; Kim, E.; Shin, G. Changes in low back muscle activity and spine kinematics in response to smartphone use during walking. Spine 2021, 46, E426–E432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sajewicz, J.; Dziuba-Sękonsina, A. Texting on a smartphone while walking affects gait parameters. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hollman, J.H.; Kovash, F.M.; Kubik, J.J.; Linbo, R.A. Age-related differences in spatiotemporal markers of gait stability during dual task walking. Gait Posture 2007, 26, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarvestan, J.; Aghaie Ataabadi, P.; Svoboda, Z.; Alaei, F.; Graham, R.B. The effects of mobile phone use on motor variability patterns during gait. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0267476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, A.C.; Breloff, S.P. The effect of various cell phone related activities on gait kinematics. J. Musculoskelet. Res. 2020, 22, 3n04. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessari, G.M.; Melo, S.J.; Lino, T.B.; Junior, S.A.S.; Christofoletti, G. Effects of smartphone use on postural control and mobility: A dual-task study. Braz. J. Mot. Behav. 2023, 17, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamberg, E.M.; Muratori, L.M. Cell phones change the way we walk. Gait Posture 2012, 35, 688–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourra, G.N.; Sénécal, S.; Fredette, M.; Lepore, F.; Faubert, J.; Bellavance, F.; Cameron, A.F.; Labonté-LeMoyne, É.; Léger, P.M. Using a smartphone while walking: The cost of smartphone-addiction proneness. Addict. Behav. 2020, 106, 106346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashish, R.; Toney-Bolger, M.E.; Sharpe, S.S.; Lester, B.D.; Mulliken, A. Texting during stair negotiation and implications for fall risk. Gait Posture 2017, 58, 409–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silsupadol, P.; Teja, K.; Lugade, V. Reliability and validity of a smartphone-based assessment of gait parameters across walking speed and smartphone locations: Body, bag, belt, hand, and pocket. Gait Posture 2017, 58, 516–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, S.; Kim, C.; Song, S.; Lee, G. Changes in gait pattern during multitask using smartphones. Work 2015, 53, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cevik, S.; Kaplan, A.; Katar, S. Correlation of cervical spinal degeneration with rise in smartphone usage time in young adults. Niger. J. Clin. Pract. 2020, 23, 1748–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuang, L.; Wang, L.; Xu, D.; Wang, Z.; Liang, R. Association between excessive smartphone use and cervical disc degeneration in young patients suffering from chronic neck pain. J. Orthop. Sci. 2021, 26, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author | Population (M/F) | Methods (Interventions) | Main Outcome Measures | Alteration of Parameters | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Faeze [5] (2022) | 26/54 Age: 21 years | Participants sat on a chair with and without backrest support. | Head tilt angle Neck tilt angle Gaze angle Forward head posture | Posture condition: Standing Head tilt: moderate (107.1°) Neck tilt: moderate (27.6°) FHP: moderate (14.9 cm) Gaze angle: highest (67.1°) Posture condition: sitting without backrest Head tilt: highest (109.6°) Neck tilt: lowest (22.0°) FHP: worst (15.9 cm) Gaze angle: high (66.6°) Posture condition: sitting with backrest Head tilt: lowest (100.6°) Neck tilt: optimal (32.5°) FHP: best (13.8 cm) Gaze angle: lowest (58.2°) | Using a smartphone significantly affects neck pressure, with noticeable differences in angles depending on the position. |

| Marina [14] (2018) | 42/18 Age: 17 years | Nerve conduction velocity was measured for the right and left median nerves. | Hand grip EMG Goniometer Visual analog scale Forward Head Posture | Prolonged smartphone use (>4 h/day): FHP angle: 61.2° → 52.5° Neck pain (VAS): 1.7 → 6.13 Ulnar nerve conduction velocity: decreased Median nerve conduction velocity: no change Hand grip strength: no change | Prolonged smartphone use in adolescents decreases ulnar nerve conduction velocity, increases forward head posture, and causes neck pain, without affecting hand grip strength or median nerve conduction velocity. |

| Han [16] (2019) | 15/13 Age: 23 years | Participants engaged in upright walking under three conditions: (1) walking without using a smartphone, (2) one-handed smartphone browsing while walking, and (3) two-handed texting while walking. | Head flexion angle | Walking while texting (two-handed): Head flexion angle: highest (38.5°) Neck load: increased demand Head motion variation: minimal dynamic range Walking while browsing (one-handed): Head flexion angle: moderate (31.1°) Neck load: elevated but less than texting Head motion variation: moderate reduction Walking upright (no smartphone): Head flexion angle: neutral (−1.2°) Neck load: lowest Head motion variation: natural oscillation maintained | Smartphone use while walking increases head flexion angle by 38.5 deg (two-handed texting), 31.3 deg (one-handed web-browsing), and by −1.2 deg (upright). |

| Bruhl [15] (2023) | 21 (M) Age: 25 years | Participants maintained a neutral gaze (straight ahead) and performed reading tasks on a smartphone: using one hand using both hands. | Kyphosis angle Lordosis angle VP flexion Lateral deviation | Spinal posture (standing and walking): VP flexion: increased (S1H: +6.2°, S2H: +4.8° vs. GN) Thoracic kyphosis angle: increased (S1H: +9.7°, S2H: +12.5° vs. GN) Lumbar lordosis angle: no change Lateral deviation (frontal plane): no change | Smartphone use induced increased VP flexion and kyphosis angle. Smartphone use during walking induced higher kyphosis angle. |

| Tapanya [18] (2021) | 16/16 Age: 21 years | Before being tested, participants were randomly assigned to one of four neck flexion angles: 0°, 15°, 30°, or 45°. | Gravitational moment Head tilt angle Forward head distance Craniovertebral angle Gaze angle Phone tilt angle Cervical erector spinae EMG Upper trapezius EMG | Neck flexion: 0° → 15° → 30° → 45° Gravitational moment: 2.13 → 6.80 Nm Forward head distance: 10.01 → 14.99 cm CES EMG: 7.4% → 13.9% in MVC UT EMG: 3.97% → 1.80% in MVC Neck discomfort: 2.0 → 3.6 cm in VAS Phone tilt angle: 75.9° → 22.1° | Using a smartphone while in a flexed neck posture increases the biomechanical burden on cervical kinematics, as well as gravitational moments and neck muscle loading, potentially increasing the risk of musculoskeletal discomfort. |

| Eardley [19] (2018) | 10/10 Age: 30 years | A range of four hand grip types was assessed, depending on interaction (touchscreen, stylus, and keyboard), across three postures: sitting at a table with arms resting; standing; and lying supine (on the back). | Hand grip Hand movement | Body posture: Lying down Most phone movement (Alpha ↑, Beta ↑, Gamma ↑); least secure and comfortable posture Body posture: Single-handed (S) grip Greatest instability Body posture: Sitting at a table Moderate movement; better body support, but higher arm restriction Body posture: Symmetric bimanual (B) and asymmetric finger (AF) grips More stable than S (single-handed) Body posture: Standing Least phone movement; best for comfort and device security Body posture: AF (asymmetric finger) grip Rated most secure, followed by B (symmetric bimanual) By hand grip (across all postures) S (single-handed): most movement across all axes (Alpha, Beta, Gamma) Least secure, least comfortable AF (asymmetric finger): least movement overall, most preferred, most stable grip especially effective in standing posture B (symmetric bimanual) and asymmetric thumb (AT): moderate movement; balanced trade-off between control and flexibility | Hand movements are affected by grip type and smartphone size. Lying down body posture had the most movement followed by sitting and standing. |

| Yan [20] (2018) | 15/22 Age: 24 years | Participants completed text-entry tasks (texting with one hand, two hands, and typing on a desktop keyboard) for 10 min per task, with 5 min rest intervals between tasks. | Word speed Accuracy Cervical spine angle Thoracic spine angle Lumbar spine angle | Bilateral texting vs. unilateral texting Cervical flexion angle: increased in bilateral texting (4°) Cervical right rotation: decreased in bilateral texting (2–4°) Postural variability (cervical): higher in unilateral texting Smartphone texting vs. computer typing Cervical and thoracic flexion: higher during smartphone texting Lumbar flexion: more in computer typing Frequency and range of cervical motion: lower in smartphone texting Participants with chronic neck–shoulder pain vs. healthy controls Cervical side flexion (right): slightly higher in the pain group Postural change range (cervical rotation): greater in the pain group | Texting on a smartphone is associated with a more static and flexed spinal posture compared to typing on a desktop, with bilateral texting increasing cervical flexion and unilateral texting causing asymmetrical posture. |

| Chen [29] (2023) | 30/30 Age: 22 years | The study comprised 18 trial sessions, during which data were collected on neck flexion, head flexion, gaze angle, and viewing distance during smartphone use. Participants performed tasks in three postures and two hand-use conditions, with each combination repeated three times. | Upper thoracic angle Head flexion Neck flexion Gaze angle Viewing distance | Standing vs. walking (slow vs. normal) NF: standing (37.7°) NF: walking at slow (31.7°) NF: walking at normal (32.1°) HF: no change GA: no change VD: interaction with hand use (see below) Two-handed texting vs. one-handed browsing NF: increased in two-handed HF: increased in two-handed GA: increased in two-handed VD: incresed in two-handed when standing, but decreased during walking Sex differences: decreased in NF, HF, GA in women VD: decreased in women due to shorter arm length | Smartphone use during walking increased cervical kyphosis compared to standing. Two-handed texting increased neck flexion, head flexion, and gaze angle compared to one-handed browsing. |

| Choi [21] (2016) | 8/7 Age: 24 years | A single group of participants adopted three neck postures (maximum flexion, moderate flexion, and neutral), while the muscle activity and fatigue of 15 participants were measured via surface EMG. | Splenius capitis EMG Upper trapezius EMG | EMG activity Splenius capitis EMG: no change Upper trapezius EMG: no change Muscle fatigue Right splenius capitis: highest in maximum bending Left splenius capitis: highest in maximum bending Left upper trapezius: highest in maximum bending | Smartphone use during maximum bending posture increased levels of fatigue in splenius capitis and upper trapezius compared to the middle bending posture. No differences in muscle activity of splenius capitis and upper trapezius among three postures. |

| Jung [30] (2021) | 16/9 Age: 18 years | Participants sat on a height-adjustable chair with hips and knees at 90° for 30 min in a habitual sitting posture. Pelvic asymmetry, thoracolumbar kyphosis, and lumbar lordosis were assessed using 3D motion capture. | Lumbar lordosis angle Pelvic asymmetry angle Thoracolumbar kyphosis angle | Smartphone use for 30 min in sitting posture: Thoracolumbar kyphosis: increased in both groups (Low back pain > control) Effect size: 2.11 (low back pain) Effect size: 1.25 (control) Lumbar lordosis: decreased in both groups (Low back pain > control) Eeffect size: 2.54 (low back pain) Effect size: 1.61 (control) Pelvic asymmetry: no change | Thoracolumbar kyphosis tends to increase during smartphone use, particularly in adolescents with lower back pain. |

| Park [31] (2017) | 18 (M) Age: 21 years | Surface EMG (Noraxon, Scottsdale, AZ, USA) and digital cameras (Sony, Tokyo, Japan) were used to measure muscle activity and angular changes in the neck and trunk during 16 min of smartphone use. | Neck angle Cervical and thoracic angle Trunk angle Cervical erector spinae EMG Thoracic erector spinae EMG Lower trapezius EMG | Smartphone gaming (16 min sitting, unsupported posture): Neck flexion angle: 66.0° → 90.3° Trunk flexion angle: 104.0° → 81.7° (more flexion) CES EMG amplitude: increased TES and LT EMG amplitude: decreased UT EMG amplitude: no change 10% APDF (CES): indicating greater sustained load 10% APDF (TES, LT): indicating load transfer to passive structures Pain (VAS): in both neck (4.2) and trunk (2.2) | Smartphone use caused flexed neck and trunk postures, reduced thoracic erector spinae and lower trapezius muscle activity, and induced pain. |

| Lee [17] (2015) | 8/6 Age: 22 years | Each participant sat with their back against a wall, holding a smartphone with both hands. The muscle fatigue of the neck and shoulders was measured using EMG at 0°, 30°, and 50° cervical flexion angles. | Cervical angle Upper trapezius EMG Cervical erector spinae EMG Pressure pain threshold | Cervical flexion angle conditions: 0°, 30°, 50° (10 min smartphone use) Muscle fatigue: median frequency was reduced (fatigued) Right UT EMG: 42.5 → 26.3 Hz Left UT EMG: 38.2 → 18.7 Hz R/L CES EMG: no change Pressure pain threshold: decreased (more sensitive) Right UT PPT: 15.9 → 14.7 lb Left UT PPT: 16.6 → 15.1 lb R & L CES PPT: no change | Increased cervical flexion angle during smartphone use induced upper trapezius muscle fatigue and pain measured by an algometer (pressure pain threshold). |

| Yoon [32] (2015) | 18/2 Age: 28 years | Participants walked on a treadmill for 20 min while using a smartphone. Lumbar repositioning error was measured via an electronic goniometer, and lumbar curvature was assessed using a spinal mouse, before and immediately after the task. | Lumbar spine repositioning error Lumbar curvature angle | Walking on treadmill for 20 min while using smartphone Lumbar repositioning error: increased (3.02 → 6.07) Lumbar curvature: no change | Walking while using a smartphone leads to increased lumbar repositioning errors immediately after the activity, though lumbar curvature remains unchanged. |

| Choi [33] (2021) | 11/9 Age: 21 years | Participants walked on a treadmill under five different conditions: (1) normal walking without smartphone use (control), (2) one-handed smartphone browsing, (3) two-handed texting, (4) walking with one arm bound, and (5) walking with both arms bound. | Head sagittal angle Thorax sagittal angle Pelvis sagittal angle Thoracic kyphosis angle Lumbar lordosis angle Thorax transverse ROM Pelvis transverse ROM Lumbar erector spinae EMG | Browsing + walking/texting + walking vs. normal walking Lumbar erector spinae EMG: incrased by 16.5% during browsing, and 31.8% during texting Spinal sagittal kinematics: increased in thoracic kyphosis during texting (+1.5°), and browsing (+1.1°) Lumbar lordosis ROM: increased in texting (+1.4°), and browsing (+0.9°) Head flexion angle: increased in texting (39.3° vs. 0.4°) Pelvis and thorax transverse ROM: decreased during texting in thorax by 28.8% less (6.4° vs. 9.2° normal) Thorax ROM: decreased during texting by 28.8% (6.4° vs. 9.2° normal) Pelvis ROM: decreased during texting by 11.8% during texting (8.2° vs. 9.3° normal) | Smartphone use caused more thoracic kyphosis and lumbar lordosis. Smartphone use during walking increased lumbar erector spinae muscle activity by 16.5% (browsing) and 31.8% (texting). |

| Author | Population (M/F) | Methods (Interventions) | Main Outcome Measures | Alteration of Parameters | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Krasovsky [26] (2021) | 14/15 Age: 26 years | Participants completed walking trials while texting or reading. | Gait speed Stride length Stride time Gait speed variability Words Text comprehension Task workload | Texting vs. reading during walking (dual-task condition): Gait speed: decreaed Stride length: decreased Stride time: slower rhythm Gait speed variability: decreased stability Text comprehension: decreased Perceived workload: higher in texting A dual-task condition was correlated with perceived task prioritization (r = 0.39–0.50) and cognitive flexibility (r = 0.55) | Smartphone use (texting) during walking results in decreased gait speed, increased gait variability, decreased text comprehension, and increased task workload. |

| Sajewicz [34] (2023) | 20/22 Age: 21 years | Participants completed four walking conditions: (1) walking without a phone at a comfortable velocity, (2) walking without a phone at a fast velocity, (3) walking with a phone at a comfortable velocity, and (4) walking with a phone at a fast velocity. | Step length Step width Cadence Gait speed | Texting while walking vs. walking Step length: decreased Comfortable speed: 70.6 → 65.5 cm Fast speed: 81.3 → 74.4 cm Gait speed: decreased Comfortable speed: 1.36 → 1.27 m/s Fast speed: 1.87 → 1.67 m/s Cadence: decreased at fast speed while texting Step width: decreased at comfortable speed while texting | Smartphone use (texting) during walking induces decreased step length, step width, cadence, and gait speed. |

| Crowley [9] (2021) | 11/9 Age: 27 years | Participants repeated six conditions consisting of self-selected normal and fast overground walking while texting on a mobile phone, talking or performing no concurrent task. | Gait speed Variability in trunk acceleration Sample entropy Maximum Lyapunov exponent | Walking only vs. walking while texting Root mean square ratio: Vertical (VT) at fast speed: increased Anteroposterior (AP): decreased Mediolateral (ML): no change Sample entropy (SaEn): VT axis: decreased while texting AP, ML axes: increased with speed Max Lyapunov exponent: VT and AP axes: increased while texting ML axis: non-significant | Higher gait speed induces increased sample entropy and trunk acceleration (vertical axis) and decreased the proportion of acceleration (anteroposterior axis). Walking while texting increased the maximum Lyapunov exponent along the vertical and anteroposterior axes. These findings indicate reduced dynamic stability of the trunk, and increased trunk variability. |

| Alapatt [24] (2020) | 308 5 age groups: 20–29, 30–39, 40–49, 50–59, ≥60 years | Participants completed five walking conditions: (1) walking on a treadmill at a regular pace, (2) walking on a treadmill while using a mobile phone with one hand, (3) walking on a treadmill in a low-light condition, (4) walking on a treadmill while listening to favorite music using a headset, and (5) walking on a treadmill while engaged in a real voice call in their official language. | Gait speed | Walking vs. walking while texting by age groups Gait speed: decreased during walking while texting across all age groups Total population: 1.47 → 1.16 m/s (22.3%) Age ≥ 60: 1.42 → 1.00 m/s (30.4%) Age 50–59: 1.47 → 1.07 m/s (25.9%) Texting accuracy: an error rate was increased with age Age < 30: 0% errors Age 50–59: 62.7% errors Age ≥ 60: 81.0% errors | Gait speed was decreased while texting with increasing age; a percentage reduction in gait speed by 11% (20–29 yrs), 11% (30–39 yrs), 17% (40–49 yrs), 26% (50–59 yrs), 30% (≥60 yrs). |

| Hollman [35] (2007) | 25/35 3 age groups: 25 years 48 years 81 years | Gait parameters were quantified using GaitRite (CIR Systems, Franklin, NJ, USA). In the dual-task condition, participants were required to spell five-letter words in reverse while walking across a walkway. | Gait speed Stride variability | Dual-task walking (backward spelling) vs. normal walking Gait speed: decreased (all age groups) Older adults: 20%↓ Middle-aged adults: 7%↓ Younger adults: 8%↓ Stride-to-stride variability in gait speed: increased Older adults: 2.9%↑ Middle-aged adults: 1.5%↑ Younger adults: no change Cognitive performance (spelling errors): similar across groups (non-significant), but in older adults: Cognitive error↑: Gait velocity↓ (r=–0.49) Cognitive error↑: Gait variability↑(r=0.53) | Dual-task walking results in decreased gait speed, and increased stride-to-stride variability in gait speed. Stride velocity variability was increased in older adults compared to younger groups. |

| Schabrun [25] (2014) | 7/19 Age: 29 years | Participants walked on an 8.5 walkway ground under three walking conditions: (1) walking without the use of a phone, (2) reading text on a mobile phone, or (3) typing text on a mobile phone. | Lateral foot position Gait speed Joint ROM Stride length Stride frequency Lateral deviation | Walkig vs. reading vs. texting while walking Walking speed: texting < reading < control↓ Stride length and frequency: decreased while texting Lateral deviation: increased in an order of texting > reading > control Head flexion ROM: increased in both reading and texting while walking (~30°) Neck ROM (all planes): decreased by Texting < reading < walking Thorax ROM: decreased during texting Head–thorax ROM: increased (more head ROM) Pelvis–thorax ROM: decreased | Smartphone use (texting or reading) during walking results in greater lateral foot position, slower gait speed, greater head rotation ROM, less neck ROM, and more lateral deviation from a straight line. |

| Sarvestan [36] (2022) | 15/14 Age: 28 years | Participants walked on a treadmill under six conditions: (1) normal walking, (2) normal walking in low-light conditions, (3) walking while looking at a phone, (4) walking while looking at a phone in low-light conditions, (5) walking and talking on a phone, and (6) walking and listening to music. | Joint angle Joint angle variability Center of pressure EMG of gluteus medius, rectus femoris, vastus medialis, biceps femoris, medial gastrocnemius, tibialis anterior | Normal walking vs. walking while looking at phone (WLP) vs. walking while looking at phone in low light conditions (WLLLP) vs. walking while talking on phone (WTP) vs. walking while listening to music (WM) Hip joint angle variability (λS, λL): increased in WLP and WLLLP Pelvis angle variability (λS, λL): increased in sagittal plane (WLLLP > NW, WM, WTP) Lower limb muscle activation variability (RF, VM, TA, GA, BF, GM): no change COM trajectory variability (λS, λL): no change | Smartphone use (condition 3) results in higher joint angle variability in the hip and pelvis. No center of mass position and EMG activation was observed between walking task conditions. |

| Brennan [37] (2020) | 7/7 Age: 20 years | Participants completed five walking conditions of one single-task walking and four dual-task conditions: (1) walk + converse, (2) walk + read (simple), (3) walk + read (difficult), and (4) walk + text. Gait analysis was recorded with a motion capture system and peak sagittal plane lower extremity joint angles, gait velocity, and stride length were calculated. | Gait joint kinematics Gait speed Stride length | Walk+converse; walk+read; walk+text; normal walking Gait speed: decreased by task difficulty Single task: 1.41 m/s → walk + text: 1.04 m/s Stride length: decreased Single task: 1.29 m → walk + text: 1.09 m Peak hip flexion (initial contact): decreased Single task: 30.27° → walk + text: 27.27° Peak hip extension (terminal stance): de creased Single task: 13.08° → walk + text: 10.36° Peak plantarflexion (pre-swing): decreased Single task: 27.67° → walk + text: 19.83° Peak dorsiflexion (terminal stance): in creased Single task: 7.86° → walk + text: 9.87° | Smartphone use alters sagittal gait kinematics, reduces gait speed and stride length. |

| Giovanna [38] (2023) | 20/25 Age: 22 years | Participants performed a balance task on a force platform. The impact of smartphone use was assessed during both a static test (on the force platform) and a dynamic test (Timed Up and Go; TUG). Participants were instructed to text a message and talk on a phone while standing or walking, and various variables were measured during the TUG test. | BMI Mini-mental state examination score Frontal assessment battery score Time of using the smartphone Postural balance (frontal sway, lateral sway, center of pressure sway) Frontal speed Lateral speed | No phone vs. texting vs. talking on the phone (tasks performed during standing or walking) Static standing postural control test Frontal sway: increased No phone: 1.9 cm Texting: 2.7 cm Talking: 3.9 cm Lateral sway: increased No phone: 1.7 cm Talking: 2.8 cm Center of pressure sway area: increased No phone: 2.3 cm2 Talking: 5.9 cm2 Dynamic walking test TUG test completion time: increased No phone: 9.2 s Texting: 11.8 s Talking: 11.1 s Number of steps: increased No phone: 13.2 Texting: 15.5 Talking: 14.9 | Smartphone use (texting or talking) reduces both static (force plate) and dynamic (TUG) postural control tasks. |

| Lamberg [39] (2012) | M:13 Age: 26 years | Participants performed a dual task, such as talking or texting on a cell phone while walking, which may interfere with working memory and result in walking errors. At baseline, participants visually located a target 8 m ahead. | Gait speed Linear distance travel Lateral angular deviation from the start line | Walking while texting (TEXT) or talking (TALK) vs. walking without phone (WALK) Gait velocity: decreased TEXT: 33% (7.0 → 4.7 m/s) TALK: 16% (7.5 → 6.3 m/s) WALK: no change Lateral deviation: increased TEXT: 61% (68 → 108 cm) TALK: no change WALK: no change Linear distance traveled: increased TEXT: 13% (7.5 → 8.5 m) TALK: no change WALK: no change | Smartphone use reduces gait speed (texting: 33%; talking: 16%) and increases lateral deviation (61%) and linear distance traveled (13%). |

| Chen [29] (2018) | 5/5 Age: 21 years | Participants engaged in two tasks: (1) walking and crossing an obstacle set at 10% of the participant’s height and (2) walking and crossing the same obstacle while responding to a text message. Whole-body motion data were collected using a 10-camera motion capture system. | Gait speed Obstacle clearance Postural sway | Obstacle crossing while texting (OC + texting) vs. obstacle crossing only (OC) Toe–obstacle clearance: increased Leading foot: 15.7 → 19.1 cm Trailing foot: 18.7 → 24.8 cm Foot placement: decreased Leading foot: 25.4 → 21.2 cm Trailing foot: no change Gait speed: decreased Approaching stride: 1.22 → 1.11 m/s Crossing stride: 1.10 → 0.94 m/s Peak COM forward velocity: 1.4 → 1.3 m/s Mediolateral COM distance: 4.5 → 6.2 cm | Smartphone use (texting) during crossing over the obstacle decreases gait speed, increases toe–obstacle clearances, and induces higher postural sway in the frontal plane. |

| Mourra [40] (2020) | 20/28 Age: 25 years | Participants were selected to represent a range of smartphone-addiction proneness. Four smartphone-use conditions were simulated: (1) a control condition with no smartphone use, (2) an individual conversation condition, (3) a gaming condition, and (4) a group conversation condition. | Smartphone-addiction proneness scale Walking performance (missed stimuli and accuracy) | Walking performance measures (direction recognition task). Control (CC) vs. Individual conversation (ICC) vs. Gaming (GC) vs. Group conversation (GCC) Accuracy: decreased CC (baseline): 89% ICC: 86% GC: 81% (lowest) GCC: 84% Number of missed stimuli: decreased CC: 0.04 ICC: 1.40 GC: 2.42 (highest) GCC: 1.67 Psychological mediation: Emotional arousal (SAM scale): increased by GC > GCC > ICC > CC Arousal (mediated accuracy): decreased Arousal (missed stimuli): increased | Smartphone use while walking decreased accuracy on smartphone tasks and increases the number of missed stimuli. Higher smartphone addiction proneness scores were also prone to missing stimuli on smartphone use tasks. |

| Hashish [41] (2017) | 7/13 Age: 39 years | Participants performed a series of walking trials that included a step-deck obstacle, consisting of at least three trials while texting and three trials without texting. | Gait speed Step width | Texting while ascending/descending stairs vs. no texting Stair ascent: decreased Ascent speed: 70→60 cm/s Dual-step toe clearance (vertical): 9→8 cm Dual-step toe clearance: 13→11 cm Forefoot toe distance dual-step: 28→24 cm Forefoot toe distance single-step: 6→5 cm Stair descent: decreased Descent speed: 82 → 71 cm/s Single-step heel clearance vertical: 18→17cm Single-step heel clearance forefoot:34→29cm Dual-step heel clearance forefoot: 27→21 cm Step width: no change | Smartphone use (texting) reduced gait speed (ascending and descending) and step foot clearance. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, I.G.; Son, S.J. Effects of Smartphone Use on Posture and Gait: A Narrative Review. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 6770. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15126770

Lee IG, Son SJ. Effects of Smartphone Use on Posture and Gait: A Narrative Review. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(12):6770. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15126770

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, In Gyu, and Seong Jun Son. 2025. "Effects of Smartphone Use on Posture and Gait: A Narrative Review" Applied Sciences 15, no. 12: 6770. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15126770

APA StyleLee, I. G., & Son, S. J. (2025). Effects of Smartphone Use on Posture and Gait: A Narrative Review. Applied Sciences, 15(12), 6770. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15126770