Lippia citrodora (Lemon Verbena) Extract Helps Reduce Stress and Improve Sleep Quality in Adolescents in a Double-Blind Randomized Intervention Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Herb Extract

2.3. Randomization and Study Procedures

2.4. Study Variables

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

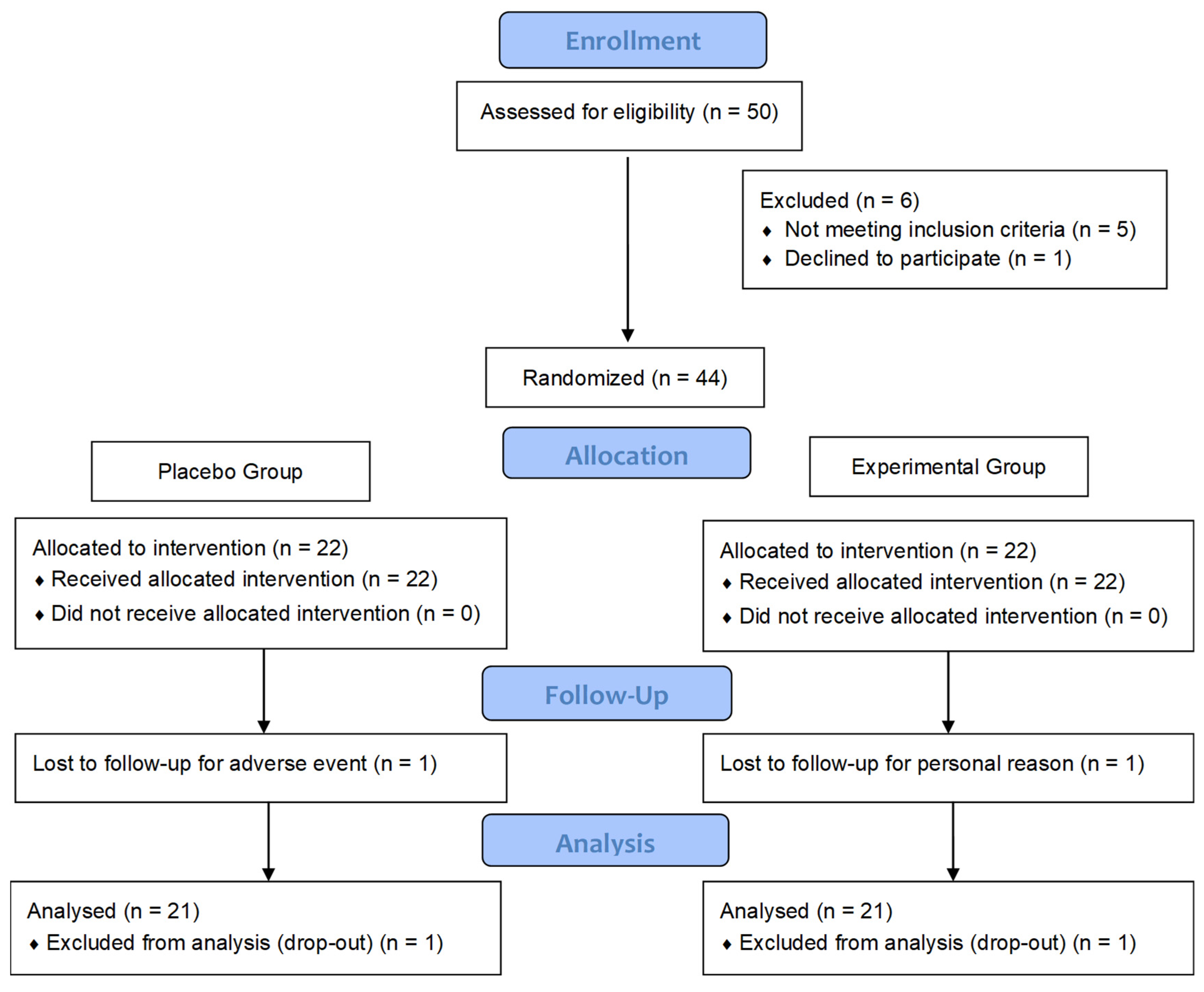

3.1. Participants

3.2. Adolescent Sleep Wake Scale (ASWS)

3.3. Perceived Stress Scale for Children (PSS-C)

3.4. Cortisol Levels

3.5. Psychologist Evaluation of the Treatment Efficacy

3.6. Parental Evaluation Questionnaire

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hirshkowitz, M.; Whiton, K.; Albert, S.M.; Alessi, C.; Bruni, O.; DonCarlos, L.; Hazen, N.; Herman, J.; Katz, E.S.; Kheirandish-Gozal, L.; et al. National Sleep Foundation’s sleep time duration recommendations: Methodology and results summary. Sleep Health 2015, 1, 40–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopasz, M.; Loessl, B.; Hornyak, M.; Riemman, D.; Nissen, C.; Piosczyk, H.; Volderholzer, U. Sleep and memory in healthy children and adolescents—A critical review. Sleep Med. Rev. 2010, 14, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruce, E.S.; Lunt, L.; McDonagh, J.E. Sleep in adolescents and young adults. Clin. Med. 2017, 17, 424–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.L.; Nie, X.Y.; Li, J.; Tao, Y.J.; Zhao, C.H.; Zhong, H.; Pan, C.W. Factors associated with sleep disorders among adolescent students in rural areas of China. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1152151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanbhog, M.S.; Medikonda, J. A clinical and technical methodological review on stress detection and sleep quality prediction in an academic environment. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2023, 235, 107521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basta, M.; Chrousos, G.P.; Vela-Bueno, A.; Vgontzas, A.N. Chronic insomnia and stress system. Sleep Med. Clin. 2007, 2, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, S.M. Insomnia: An integrative approach to stress-induced insomnia. Holist. Nurs. Pract. 2011, 25, 266–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiera, M.; Faraci, F.; Mannino, G.; Vantaggiato, L. The impact of the pandemic on psychophysical well-being and quality of learning in the growth of adolescents (aged 11–13): A systematic review of the literature with a PRISMA method. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1384388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruni, O.; Breda, M.; Nobili, L.; Fietze, I.; Capdevila, O.R.S.; Gronfier, C. European expert guidance on management of sleep onset insomnia and melatonin use in typically developing children. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2024, 183, 2955–2964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Liu, C.; Wang, Y.; Wang, P.; Li, Y.; Li, B. Herbal Medicine for Anxiety, Depression and Insomnia. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2015, 13, 481–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Yan, Y.; Wu, Y.; Yang, H.; Zhu, P.; Yan, F.; Zhao, R.; Tian, P.; Wang, T.; Fan, Q.; et al. Medicinal herbs for the treatment of anxiety: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Pharmacol. Res. 2022, 179, 106204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trompetter, I.; Krick, B.; Weiss, G. Herbal triplet in treatment of nervous agitation in children. Wien. Med. Wochenschr. 2013, 163, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Kean, J.D.; Kaufman, J.; Lomas, J.; Goh, A.; White, D.; Simpson, D.; Scholey, A.; Singh, H.; Sarris, J.; Zangara, A.; et al. A Randomized Controlled Trial Investigating the Effects of a Special Extract of Bacopa monnieri (CDRI 08) on Hyperactivity and Inattention in Male Children and Adolescents: BACHI Study Protocol (ANZCTRN12612000827831). Nutrients 2015, 7, 9931–9945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deshpande, S.N.; Simkin, D.-R. Complementary and Integrative Approaches to Sleep Disorders in Children. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2023, 32, 243–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Rodríguez, A.; Martínez-Olcina, M.; Mora, J.; Navarro, P.; Caturla, N.; Jones, J. Anxiolytic effect and improved sleep quality in individuals taking Lippia citrodora extract. Nutrients 2022, 14, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Piñero, S.; Muñoz-Carrillo, J.C.; Echepare-Taberna, J.; Muñoz-Cámara, M.; Herrera-Fernández, C.; García-Guillén, A.I.; Ávila-Gandía, V.; Navarro, P.; Caturla, N.; Jones, J.; et al. Dietary Supplementation with an Extract of Aloysia citrodora (Lemon verbena) Improves Sleep Quality in Healthy Subjects: A Randomized Double-Blind Controlled Study. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabti, M.; Sasaki, K.; Gadhi, C.; Isoda, H. Elucidation of the molecular mechanism underlying Lippia citrodora(Lim.)-induced relaxation and anti-depression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dyk, T.; Becker, S.; Byars, K. Rates of Mental Health Symptoms and Associations with Self-Reported Sleep Quality and Sleep Hygiene in Adolescents Presenting for Insomnia Treatment. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2019, 15, 1433–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essner, B.; Noel, M.; Myrvik, M.; Palermo, T. Examination of the Factor Structure of the Adolescent Sleep–Wake Scale (ASWS). Behav. Sleep Med. 2014, 12, 296–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornienko, D.S.; Rudnova, N.A.; Tarasova, K.S. Psychometric properties of the Perceived Stress Scale for Children (PSS-C). Clin. Psychol. Spec. Educ. 2024, 13, 129–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, B.P. The Perceived Stress Scale for Children: A Pilot Study in a Sample of 153 Children. Int. J. Pediatr. Child Health 2014, 2, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual, M.E.; Slowing, K.; Carretero, E.; Sánchez Mata, D.; Villar, A. Lippia: Traditional uses, chemistry and pharmacology: A review. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2001, 76, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razavi, B.M.; Zargarani, N.; Hosseinzadeh, H. Anti-anxiety and hypnotic effects of ethanolic and aqueous extracts of Lippia citriodora leaves and verbascoside in mice. Avicenna J. Phytomed. 2017, 7, 353–365. [Google Scholar]

- Ragone, M.; Sella, M.; Pastore, A.; Consolini, A. Sedative and Cardiovascular Effects of Aloysia citriodora Palau, on Mice and Rats. Lat. Am. J. Pharm. 2010, 29, 79–86. [Google Scholar]

- Cleary, M.A.; Richardson, C.; Ross, R.J.; Heussler, H.S.; Wilson, A.; Downs, J.; Walsh, J. Effectiveness of current digital cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia interventions for adolescents with insomnia symptoms: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Sleep Res. 2025, e14466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Mental Health of Adolescents. 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Merino-Casquero, A.; Andrade-Gómez, E.; Fagundo-Rivera, J.; Fernández-León, P. Beyond Confinement: A Systematic Review on Factors Influencing Binge Drinking Among Adolescents and Young Adults During the Pandemic. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breda, M.; Belli, A.; Esposito, D.; Di Pilla, A.; Melegari, M.G.; DelRosso, L.; Malorgio, E.; Doria, M.; Ferri, R.; Bruni, O. Sleep habits and sleep disorders in Italian children and adolescents: A cross-sectional survey. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2023, 19, 659–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsao, H.S.; Gjelsvik, A.; Sojar, S.; Amanullah, S. Sounding the alarm on sleep: A negative association between inadequate sleep and flourishing. J. Pediatr. 2021, 228, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2006 Sleep in America poll—Teens and Sleep. Sleep Health 2015, 1, e5. [CrossRef]

- Wheaton, A.G.; Jones, S.E.; Cooper, A.C.; Croft, J.B. Short sleep duration among middle school and high school students—United States, 2015. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2018, 67, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorós-Reche, V.; Morales, A.; Francisco, R.; Delvecchio, E.; Mazzeschi, C.; Godinho, C.; Pedro, M.; Molina, J.; Espada, J.P.; Orgilés, M. Three Years after the Pandemic: How Has the Mental Health of Children and Adolescents Evolved? A Longitudinal Study in Italy, Spain, and Portugal. Span. J. Psychol. 2025, 28, e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, N.L.; Nicoletta, A.; Ellis, J.M.; Everhart, D.E. Validating the Adolescent Sleep Wake Scale for use with young adults. Sleep Med. 2020, 69, 217–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kornienko, D.S.; Rudnova, N.A.; Veraksa, A.N.; Gavrilova, M.N.; Plotnikova, V.A. Exploring the use of the perceived stress scale for children as an instrument for measuring stress among children and adolescents: A scoping review. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1470448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Placebo Group | Experimental Group |

|---|---|---|

| Number of subjects | 21 (50%) | 21 (50%) |

| Male/female (%) | Male 6 (28.6%) | Male 13 (61.9%) |

| Female 15 (71.4%) | Female 8 (38.1%) | |

| Age, years | 13.94 ± 1.01 | 14.33 ± 1.08 |

| Number participants per pubertal stage (pre/early/mid/late/post-pubertal) | Pre-puberty 1 (4.8%) | Pre-puberty 0 (0%) |

| Early puberty 0 (0%) | Early puberty 2 (9.5%) | |

| Mid-puberty 3 (14.3%) | Mid-puberty 3 (14.3%) | |

| Late puberty 11 (52.4%) | Late puberty 11 (52.4%) | |

| Post-puberty 6 (28.6%) | Post-puberty 5 (23.8%) |

| Study Group | Baseline | Month 1 | Month 2 | Final |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (total) | 3.2 ± 0.1 | 3.4 ± 0.1 | 3.4 ± 0.1 | 3.5 ± 0.1 |

| Experimental (total) | 3.2 ± 0.1 | 4.1 ± 0.1 *** | 4.3 ± 0.1 **** | 4.5 ± 0.1 **** |

| Placebo (males) | 3.3 ± 0.1 | 3.5 ± 0.3 | 3.6 ± 0.2 | 3.4 ± 0.3 |

| Experimental (males) | 3.3 ± 0.1 | 4.0 ± 0.1 | 4.2 ± 0.1 * | 4.4 ± 0.1 ** |

| Placebo (females) | 3.2 ± 0.1 | 3.4 ± 0.3 | 3.4 ± 0.3 | 3.5 ± 0.4 |

| Experimental (females) | 3.1 ± 0.1 | 4.2 ± 0.2 **** | 4.3 ± 0.2 **** | 4.6 ± 0.2 **** |

| Study Group | Baseline | Month 1 | Month 2 | Final |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo | 18.2 ± 0.6 | 18.1 ± 0.7 | 17.9 ± 0.6 | 17.2 ± 0.7 |

| Experimental | 18.0 ± 0.6 | 15.9 ± 1.0 * | 14.9 ± 0.8 ** | 12.9 ± 0.8 *** |

| Placebo (males) | 17.7 ± 1.2 | 17.3 ± 0.9 | 17.8 ± 1.5 | 17.2 ± 0.9 |

| Experimental (males) | 16.8 ± 0.6 | 14.3 ± 1.2 | 14.0 ± 1.0 * | 11.5 ± 0.7 *** |

| Placebo (females) | 18.5 ± 0.7 | 18.4 ± 0.8 | 17.9 ± 0.6 | 17.2 ± 0.9 |

| Experimental (females) | 19.8 ± 0.8 | 18.4 ± 1.3 | 16.3 ± 1.1 ** | 15.3 ± 1.3 * |

| Study Group | Baseline | Month 1 | Month 2 | Final |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo | 0.56 ± 0.03 | 0.57 ± 0.04 | 0.57 ± 0.04 | 0.61 ± 0.05 |

| Experimental | 0.57 ± 0.04 | 0.62 ± 0.03 | 0.54 ± 0.04 | 0.45 ± 0.03 * |

| Placebo (males) | 0.56 ± 0.06 | 0.55 ± 0.09 | 0.52 ± 0.05 | 0.58 ± 0.09 |

| Experimental (males) | 0.51 ± 0.04 | 0.63 ± 0.05 | 0.49 ± 0.04 | 0.41 ± 0.03 |

| Placebo (females) | 0.55 ± 0.04 | 0.59 ± 0.05 | 0.59 ± 0.06 | 0.62 ± 0.07 |

| Experimental (females) | 0.68 ± 0.06 | 0.61 ± 0.05 | 0.63 ± 0.08 | 0.51 ± 0.05 * |

| Result | % Placebo Subjects | % Experimental Subjects |

|---|---|---|

| Completely disagree | 29% | 0% |

| Disagree | 52% | 14% |

| Agree | 19% | 62% |

| Completely agree | 0% | 24% |

| Final decision if treatment is efficient | Disagree | Agree |

| Placebo Group Results | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Items | % of Subjects per Each Score | % of Subjects Answering > 6 | Median Value | ||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | ||||

| 01 | How much do you think the food supplement improves the quality of your child’s sleep? | 0% | 5% | 14% | 19% | 24% | 29% | 5% | 5% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 5% | 4 |

| 02 | How much do you think the food supplement helps your child fall asleep more easily (reducing the time it takes to fall asleep)? | 0% | 5% | 14% | 29% | 19% | 29% | 0% | 5% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 5% | 4 |

| 03 | How much do you think the supplement helps your child increase the average number of hours of uninterrupted sleep? | 0% | 5% | 14% | 29% | 14% | 29% | 5% | 5% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 5% | 4 |

| 04 | How much do you think the food supplement helps your child fall back asleep more easily if he/she wakes up during the night? | 0% | 5% | 24% | 14% | 29% | 19% | 5% | 5% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 5% | 4 |

| 05 | How much do you think the food supplement improves your child’s morning behavior (reducing irritability and increasing energy)? | 0% | 10% | 24% | 19% | 29% | 5% | 14% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 3 |

| 06 | How much do you think the food supplement reduces your child’s stress and improves his/her emotional wellbeing? | 0% | 10% | 24% | 14% | 24% | 14% | 14% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 4 |

| 07 | How much do you think the food supplement helps to improve your child’s behavior at school? | 0% | 10% | 29% | 29% | 14% | 14% | 5% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 3 |

| 08 | How much do you think the supplement helps your child to concentrate better in class? | 0% | 10% | 33% | 24% | 14% | 14% | 5% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 3 |

| 09 | How much do you think the food supplement helps to improve your child’s performance and academic results at school? | 0% | 10% | 38% | 19% | 14% | 10% | 5% | 5% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 5% | 3 |

| 10 | Would you buy the product? | 10% | 19% | 14% | 24% | 10% | 14% | 5% | 0% | 5% | 0% | 0% | 5% | 3 |

| Experimental Group Results | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Items | % of Subjects per Each Score | % of Subjects Answering > 6 | Median Value | ||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | ||||

| 01 | How much do you think the food supplement improves the quality of your child’s sleep? | 0% | 0% | 0% | 5% | 14% | 14% | 24% | 10% | 19% | 5% | 10% | 44% | 6 |

| 02 | How much do you think the food supplement helps your child fall asleep more easily (reducing the time it takes to fall asleep)? | 0% | 0% | 0% | 14% | 10% | 10% | 19% | 10% | 24% | 5% | 10% | 49% | 6 |

| 03 | How much do you think the supplement helps your child increase the average number of hours of uninterrupted sleep? | 0% | 0% | 0% | 10% | 10% | 19% | 5% | 19% | 10% | 19% | 10% | 58% | 7 |

| 04 | How much do you think the food supplement helps your child fall back asleep more easily if he/she wakes up during the night? | 0% | 0% | 0% | 14% | 19% | 10% | 5% | 14% | 24% | 5% | 10% | 53% | 7 |

| 05 | How much do you think the food supplement improves your child’s morning behavior (reducing irritability and increasing energy)? | 0% | 0% | 0% | 10% | 19% | 10% | 24% | 5% | 14% | 10% | 10% | 39% | 6 |

| 06 | How much do you think the food supplement reduces your child’s stress and improves his/her emotional wellbeing? | 0% | 0% | 0% | 14% | 10% | 10% | 29% | 24% | 5% | 0% | 10% | 39% | 6 |

| 07 | How much do you think the food supplement helps to improve your child’s behavior at school? | 0% | 0% | 0% | 14% | 29% | 14% | 14% | 10% | 5% | 0% | 14% | 19% | 5 |

| 08 | How much do you think the supplement helps your child to concentrate better in class? | 0% | 0% | 0% | 14% | 24% | 10% | 24% | 10% | 5% | 5% | 10% | 30% | 6 |

| 09 | How much do you think the food supplement helps to improve your child’s performance and academic results at school? | 0% | 0% | 0% | 14% | 24% | 5% | 14% | 14% | 14% | 5% | 10% | 43% | 6 |

| 10 | Would you buy the product? | 0% | 0% | 0% | 5% | 24% | 10% | 19% | 0% | 29% | 5% | 10% | 44% | 6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Navarro, P.; García, A.; Villa, R.; Nobile, V.; Parisi, O.I.; Lirangi, C.; Amone, F.; D’Ambrosio, E.; Caturla, N.; Jones, J. Lippia citrodora (Lemon Verbena) Extract Helps Reduce Stress and Improve Sleep Quality in Adolescents in a Double-Blind Randomized Intervention Study. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 5856. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15115856

Navarro P, García A, Villa R, Nobile V, Parisi OI, Lirangi C, Amone F, D’Ambrosio E, Caturla N, Jones J. Lippia citrodora (Lemon Verbena) Extract Helps Reduce Stress and Improve Sleep Quality in Adolescents in a Double-Blind Randomized Intervention Study. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(11):5856. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15115856

Chicago/Turabian StyleNavarro, Pau, Adrián García, Roberta Villa, Vincenzo Nobile, Ortensia Ilaria Parisi, Chiara Lirangi, Fabio Amone, Erminia D’Ambrosio, Nuria Caturla, and Jonathan Jones. 2025. "Lippia citrodora (Lemon Verbena) Extract Helps Reduce Stress and Improve Sleep Quality in Adolescents in a Double-Blind Randomized Intervention Study" Applied Sciences 15, no. 11: 5856. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15115856

APA StyleNavarro, P., García, A., Villa, R., Nobile, V., Parisi, O. I., Lirangi, C., Amone, F., D’Ambrosio, E., Caturla, N., & Jones, J. (2025). Lippia citrodora (Lemon Verbena) Extract Helps Reduce Stress and Improve Sleep Quality in Adolescents in a Double-Blind Randomized Intervention Study. Applied Sciences, 15(11), 5856. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15115856