Abstract

Traditional ethnographic methods have long been employed to study craft practices, yet they often fall short of capturing the full depth of embodied knowledge, material interactions, and procedural workflows inherent in craftsmanship. This paper introduces a digitally enhanced ethnographic framework that integrates Motion Capture, 3D scanning, audiovisual documentation, and semantic knowledge representation to document both the tangible and dynamic aspects of craft processes. By distinguishing between endurant (tools, materials, objects) and perdurant (actions, events, transformations) entities, we propose a structured methodology for analyzing craft gestures, material behaviors, and production workflows. The study applies this proposed framework to eight European craft traditions—including glassblowing, tapestry weaving, woodcarving, porcelain pottery, marble carving, silversmithing, clay pottery, and textile weaving—demonstrating the adaptability of digital ethnographic tools across disciplines. Through a combination of multimodal data acquisition and expert-driven annotation, we present a comprehensive model for craft documentation that enhances the preservation, education, and analysis of artisanal knowledge. This research contributes to the ongoing evolution of ethnographic methods by bridging digital technology with Cultural Heritage studies, offering a robust framework for understanding the mechanics and meanings of craft practices.

1. Introduction

Ethnography is the systematic study of individual cultures, exploring cultural phenomena from the viewpoint(s) of the subject(s) of the study. It involves immersing oneself in a particular setting, such as a community or organization, and collecting data through observations and interviews. Ethnography aims to understand the experiences, behaviors, beliefs, values, and social structures of the subjects of a study. Ethnography is a methodology used in anthropology and the social sciences to understand human behavior and cultural practices. Ethnography [1] identifies and describes the activities of social groups and their members as “textual reconstructions of reality” [2,3]. Ethnography has been applied in workshops, with examples in carpentry [4], glasswork [5], and textile manufacturing [6]. However, traditional ethnographic methods often struggle to fully capture the intricacies of craft knowledge, particularly the sensory and procedural dimensions that are crucial for understanding artisanal expertise.

Craft practices embody centuries of accumulated knowledge, passed down through generations via hands-on experience and tacit learning. Despite ethnography’s long-standing role in documenting cultural practices, current methodologies lack the tools to comprehensively capture the dynamic interactions between artisans, materials, and tools. This paper addresses this gap by introducing a digitally enhanced ethnographic framework.

Over the past few years, we formalized the collection of data and knowledge on craft practice and their documentation. This effort led to a protocol for representing and organizing knowledge and digital assets following international standards adopted by the Cultural Heritage (CH) community [7].

This work extends state-of-the-art ethnographic methods and knowledge organization to capture more information. This information is (a) sensory information and tacit knowledge that practitioners utilize to carry out craft actions and (b) physical information on the mechanics and material properties governing the negotiation between the maker and the material. Collecting this information and knowledge requires the interdisciplinary collaboration of a wide range of experts.

This study presents an interdisciplinary approach that integrates digital tools, such as Motion Capture (MoCap) and 3D scanning, with ethnographic techniques to analyze craft gestures, material transformations, and production workflows. We apply this methodology to eight European craft traditions—including glassblowing, tapestry weaving, woodcarving, porcelain pottery, marble carving, silversmithing, clay pottery, and textile weaving—to demonstrate its adaptability and effectiveness.

The entities involved in a crafting process are either endurants or perdurants, corresponding to continuants and occurrents [8] in Basic Formal Ontology, respectively. An endurant is an entity that persists, maintains its identity, and remains wholly present at any given time, even as it may change. Endurants are materials, tools, machines, workplaces, and craft products. Perdurants are events, actions, processes, natural phenomena, or changes that happen to or within endurants. Perdurants are entities that unfold or occur over time, representing events, processes, and changes. Perdurants have states; different states at different times represent the stages or aspects of the process or event.

By bridging ethnography with digital technologies, this study contributes to both CH preservation and the evolution of research methodologies, offering a robust model for understanding and documenting craft practices in the 21st century.

In this work, a tool is an object or body member employed to use an affordance it bears [9], e.g., scissors provide the affordance of cutting. A machine is an apparatus comprising Archimedean Simple Machines. A crafting process schema is a representative prescription for how activities should operate in a workflow to regularly achieve desired outcomes [10]. We refer to parts of a process schema or process as step schemas or steps, respectively, independently of their depth in the process schema or process.

1.1. Overview

When working in the field, it is important to decide where to focus attention [11] to ensure that data collection is structured and meaningful. In close collaboration with expert artisans [12], researchers select the object(s) and gesture(s) of observation and digitization, and based on this, determine the best view points and recording modalities (audio, video, thermal, force) to capture essential details. These decisions directly impact the effectiveness of the multimodal recording approach.

This context-sensitive methodological approach requires intensive dialogue between researchers and the craftspeople involved in the process. This ensures that the collected data align with the knowledge modeling process. It also relies on the co-presence of researchers and artisans, with a focused attention on the precision of micro-movements that define artisanal gestures. Following [4], we recommend that researchers plan to seek out the rich points that are the makings of ethnographic accounts. These rich points will later be used to structure the digital knowledge representation framework.

This ethnographic approach is based on a series of predefined procedures designed to be applied systematically in the field to ensure consistency in observation. These procedures are designed in detail in advance in the minds of researchers and then executed in the field to replicate the original design as closely as possible [1]. However, “participant observation” [13] (p. 5) should not be oriented only as data collection but rather considered as “a way of knowing from the inside” [13] (p. 5). This immersive engagement ensures that ethnographers do not simply record actions but also gain insight into their meaning, which is crucial for accurate semantic annotation.

1.2. Observation

Observation allows us to immerse ourselves in a craft and understand the context in which gestures are performed. Through both direct ethnographic observation and video analysis, we gain insights into the tacit and sensory knowledge embedded in craft actions.

There are two tasks in this step: (a) conducting real-time ethnographic observations to understand the craft, the performed actions, and the interactions between practitioners and objects, and (b) analyzing recorded video footage of the craft process to extract precise visual details of the practitioner’s gestures, tools, and material interactions. This two-tiered approach supports the later segmentation of actions and gestures, ensuring that each movement is meaningfully categorized and annotated within a structured knowledge model.

Furthermore, observations are not limited to visual data alone. Audio recordings capture important cues, such as the rhythmic patterns of tool interactions or verbal explanations by practitioners, which enrich the interpretation of recorded actions.

By linking ethnographic observation to MoCap, semantic annotation, and multimodal analysis, we create a comprehensive digital ethnographic framework that allows for both documentation and deeper analytical insights.

1.3. Contributions of This Work

This study contributes to the field of ethnography and CH documentation by bridging traditional ethnographic methods with advanced digital tools. By enhancing how craft practices are observed, recorded, and analyzed, our approach supports both the preservation of Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH) and the development of innovative research methodologies.

One of the key contributions of this work is the preservation of craft knowledge. The study provides a structured approach to documenting artisanal techniques, ensuring that they are recorded, studied, and made accessible. Although the use of moving images in ethnographic practices is well established, this research integrates multimodal data such as MoCap, 3D scanning, and a novel use of video recordings to create a richer and more immersive representations of craft traditions.

Additionally, another contribution of this research is the interdisciplinary collaboration enabled by bringing together ethnographers, digital humanists, engineers, and craft practitioners. Through this shared knowledge framework, experts from different domains can contribute to the study and preservation of craft techniques. The study also incorporates Life Course Theory (LCT) to examine how artisans develop their expertise over time, linking technical knowledge to personal narratives and career trajectories.

Further to the abovementioned contribution, the enhancement of ethnographic methods should also be highlighted. This research extends traditional ethnography by integrating structured workflows, digital tools, and expert-driven annotation, making ethnographic studies more systematic and reproducible. It provides a methodological foundation for future research, demonstrating how digital tools can complement and enhance traditional fieldwork.

On a technical level, the study introduces a digitally enhanced ethnographic framework that combines MoCap, 3D scanning, audiovisual recording, and semantic knowledge representation. It refines the traditional ethnographic approach by distinguishing between endurant entities, such as tools and materials, and perdurant entities, such as gestures and transformations, offering a hierarchical and systematic classification of craft knowledge.

The study also advances multimodal data collection and analysis by integrating both marker-based and markerless MoCap technologies to precisely track craft gestures. This enables the more detailed examination of the biomechanics of artisanal movements. Additionally, the use of video elicitation techniques allows practitioners to reflect on their movements, providing valuable insights into the cognitive and experiential aspects of craft practice.

To ensure the structured representation of craft knowledge, this research develops an ontology-based framework that facilitates searchability, retrieval, and reusability across different disciplines, including digital humanities, artificial intelligence, and education. This approach allows craft knowledge to be not only recorded but also systematically structured for computational analysis and future research applications.

The methodology proposed in this study was tested across eight European craft traditions, demonstrating its adaptability and scalability across different materials, tools, and cultural contexts. By applying this comparative perspective, the study highlights shared techniques and material behaviors across various craft domains.

By integrating ethnographic research with cutting-edge digital methodologies, this work contributes both to the documentation of ICH and the advancement of interdisciplinary research methodologies. The framework developed in this study provides a scalable and reproducible approach for future ethnographic research, ensuring that craft knowledge remains a living and evolving resource.

2. Related Work

In 1990, UNESCO published a data collection guide for data collection for the documentation of traditional crafts [14], identifying the essential elements to be recorded: artifacts, materials, tools, and crafting actions. The digitization methods reviewed are classified according to whether they record endurant or perdurant entities. In this section, we briefly review technologies that can be used in the service of ethnographic methods.

First, we review technologies for data collection that enable endurant entity documentation. These are called digitization modalities, and their representatives are imaging [15,16] and 3D technologies [17]. Then, we review technologies for the digitization of perdurants. These are classified as audiovisual and MoCap technologies.

Second, we review ethnographic works that use digital technologies for craft documentation.

The 3D digitization of endurants regards structures of a wide variance of spatial scales in indoor and outdoor environments. The advent of digital 3D reconstruction gave rise to the concept of digital twins and opened new dimensions in 3D and material documentation.

2.1. Digitization of Endurants

2.1.1. Photographic Digitization

Photographic documentation has been conventionally used in the documentation of tangible heritage since the twentieth century. Photography has been recommended for the documentation of heritage, in general, and crafts, in particular [14]. Photographs are essential in showing the appearance of craft products, materials, and tools.

Comprehensive guides to the photographic documentation of CH artifacts and sites can be found in [18,19,20]. Spectroscopic imaging methods provide insights into the chemical composition and physical properties of materials and artifacts [21,22,23,24].

To simplify digitization, it is important to classify the shape and material imaging target. We follow the Digitization Standards for the Canadian Museum of Civilization Corporation [25], an excellent reference for photographic documentation protocols, classified per the material and artifact type.

A special case of endurants is information carriers such as books and manuscripts. Their primary digitization is photographic. Subsequent analysis regards the extraction of their verbal content conventionally through Optical Character Recognition (OCR) and more advanced methods targeting manuscripts [26,27].

2.1.2. Three-Dimensional Digitization

The 3D digitization of endurants regards structures of a wide variance of spatial scales, in indoor and outdoor environments. The choice of the 3D scanning modality depends on the size, material, and environment type. In some cases, researchers may employ multiple scanning modalities, each operational on a specific scale. For example, rooms and outdoor areas require combining terrestrial laser scanning and aerial photogrammetry. For smaller artifacts, photogrammetric reconstruction and active illumination sensors are simple and widely accessible. Comprehensive reviews of 3D digitization technologies can be found in [17,28,29,30,31].

The field of 3D digitization encompasses a variety of techniques and modalities, each with its own set of distinct characteristics. Three-dimensional digitization, or 3D scanning, has attracted a growing interest in documenting structured scenes. Several 3D scanning modalities have been developed, distinguished by whether they require contact with the scanned surfaces and objects. Non-contact scanning modalities are more widely employed, as they use light as the operating principle of the sensor. They can be further classified according to the sensor type, that is, into passive or active illumination systems. Active sensors emit their electromagnetic energy for surface detection, while passive sensors utilize ambient light.

The most adopted and robust principles for the digitization of tangible CH are time-of-flight or laser scanning, e.g., [32]; structured light, e.g., [33]; and photogrammetry, e.g., [34]. A range of products employs these principles in variations, including digitization over time [35]. In photogrammetry, terrestrial and aerial photogrammetry often differ, with the latter using the Global Positioning System (GPS) coordinates of a drone sensor to assist reconstruction. Combinations of these principles are found in off-the-shelf devices, such as handheld scanners that combine trinocular photogrammetry with active illumination.

The available technologies vary based on resolution, accuracy, range, sampling rate, cost, operating conditions, skill requirements, the purpose of documentation, the material of the scanned object, weight, and ease of transport. Photogrammetric techniques provide more photorealistic texture than time-of-flight modalities but are less accurate. When accuracy is paramount, close access to the scanned object is required. If this is impossible or impractical, aerial scans can be used. In this case, though, time-of-flight techniques provide less accurate results if the sensor is airborne and thus not static. Hence, sensor sampling rate and scan duration are relevant, as a time-of-flight scans last much longer than the acquisition of photogrammetry images.

However, not all types of materials can be digitized using these methods. Artifacts made from challenging materials exist and require specific treatment. Challenging materials exhibit specular, shiny, transparent, and translucent properties because conventional 3D reconstruction methods operate only for approximately Lambertian (matte) surfaces. Some examples are glass artifacts and shiny metals. Their digitization requires novel techniques. We have developed two techniques for transparent [36] and shiny materials. The digitization of objects and workspaces follows the guidelines established in [37].

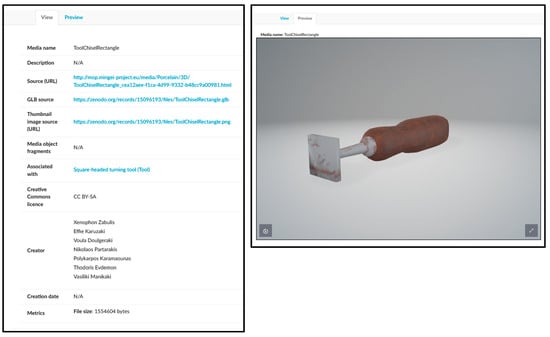

When it is difficult to perform digitization using scanning methods, modeling is possible, which refers to the computer-aided design of 3D tool models. Also, sometimes, models of tools are already available. A combination of methods is usually recommended depending on the digitization target, composition, and environment, and purpose for which the acquired digital media will be used.

2.2. Digitization of Perdurants

2.2.1. Audiovisual Digitization

The digitization of ICH efforts targets the audiovisual recording of performances [37,38,39,40,41,42]. Video recordings of performances, focusing on human motion, have been reported in [43,44,45,46]. Ethnographic documentaries are designed to provide an overview rather than a documentation of the craft. Recently, craft documentaries have focused on recording the audio and visual stimuli of crafting scenes in order to achieve better immersion in and understanding of the crafting workspace [4].

Video analysis has been widely used, given a few technical requirements. Video documentation of crafting actions and processes is used in ethnography, instructions, and documentaries [47,48]. In [48], audiovisual recording tools are proposed for the practitioner and the ethnographer (note-taking). In some cases, egocentric views [49,50] are employed, using a worn camera to capture the practitioner’s viewpoint. Video dictionaries of crafting gestures were proposed in [51].

2.2.2. Digitization of Sensory Experience

Audiovisual recordings can convey the sensations experienced by practitioners and used in craft practice [4]. Thus, they can promote the understanding of the sensory dimensions of craft practice [52]. As such, they play a key role in transmitting information that cannot be verbally represented [53]. The multimodality of these recordings is suitable for understanding what practitioners feel [52] and supplements other ethnographic methods [54].

Sensory ethnography has made important advances in motivating researchers to attend to the textures, scents, flavors, sights, and sounds of the human experience. With this in mind, audiovisual recordings can amplify [55] sensuous stimuli, and affective intensities can mobilize audiences [55] (p. 54). Pertinent video recording methods have developed from scholarship on corporeal, material, sensory, and affective matters [56].

2.3. Kinematic Digitization

Conventionally, the digitization of perdurants has focused on the actions performed by practitioners. Their digitization is possible through audio, video, and MoCap. In this work, we add the effects of practitioner actions on the treated materials and the transformations that materials undergo due to these actions. The motivation for this addition is a better understanding of the practitioners’ effort and the result of each crafting technique.

It is important to state that noninvasive technology should be used to ensure that the originality of the gesture is not affected by the capturing technologies. Furthermore, all recordings should be previewed with the practitioners to guarantee that this originality is judged upon by the person performing each action to ensure that if a deviation occurs, this will be compensated through a re-recording session.

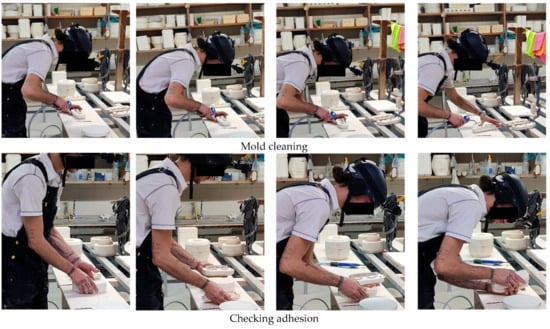

2.3.1. Images

When activities are considered, such as crafting actions, carefully selected photographs can serve as keyframes. When sequences of keyframes are juxtaposed in temporal order, they trigger visual perception to interpolate the motion between them [57], conveying the recorded motion or event. Selecting keyframes requires insight and judgment in order to choose the most indicative and educational ones. The selection of the camera viewpoint is also important in producing informative keyframes. Although keyframe sequences were necessary before video recorders, the effort placed upon their selection served an additional role. Keyframe sequences can be used to convey craft actions. Specifically, keyframes are systematically used in practical instructions relevant to body movement and actions in diverse contexts, from assembling furniture and electronics to safety instructions. It is important to state that when using wide-lens cameras to enlarge the recording area the resulting images and videos should be post-processed to deal with the lens distortion. This is something that does not require technical expertise, since most hardware and software providers provide this feature as a built-in hardware feature of the camera or a software post-processing method.

2.3.2. Video

Conventional [47] and egocentric videos [49] document the action. Egocentric video from worn cameras shows the practitioner’s hands and approximates the practitioner’s viewpoint. While egocentric video approximates the practitioner’s viewpoint, it is unstable for viewing purposes.

Egocentric videos are captured by a wearable camera, usually worn on the head or the chest. They exhibit the advantage of approximating the visual field and attention of the practitioner. They provide a valuable perspective in understanding crafting [58].

Practitioner movements can be estimated from videos using Computer Vision (CV) techniques [59]. They are significantly less accurate than MoCap recordings and require sophisticated algorithmic post-processing. Their application domain is wide but hindered by occlusions. As such, they can be used in crafts that do not use large-scale machinery and in combination with complementary modalities, e.g., sound and markers.

A fixed viewpoint has the advantage of minimizing the intrusion of the video recording equipment. A wide-angle lens is useful to record the entire scene from a close distance. Practically, a small camera can be easily mounted at vantage viewpoints but also avoids getting in the way of practitioners. Fixed viewpoints are suitable for crafts exercised on a tabletop or workbench where all actions occur and gestures are not (self)-occluded by the practitioner. Active viewpoints, where the ethnographer chooses and changes the camera viewpoint at will, are the most informative because they exhibit the potential to capture the most informative view. Egocentric videos are captured by a wearable camera, usually worn on the head or the chest.

In this context, training datasets have been developed [60,61] that offer recordings of individual gestures, where an actor performs the gestures in a MoCap laboratory. The segmentation of the examples is provided by construction, as the training examples contain a gesture in each one. Markerless human motion estimation from video provides reliable results in unobstructed scenes [62].

2.3.3. MoCap

MoCap is a technology used to capture and record the movement of people or objects and translate it into digital data. The process involves placing markers or sensors on the subject’s body or object, which are then tracked by cameras or sensors to capture their motion. For craft practice recordings, the events of interest are practitioner postures and gestures. The main types of MoCap are optical and inertial. The choice of technique depends on the specific application and the requirements for accuracy, speed, and cost.

Inertial MoCap is more suitable than optical in the cluttered space of workshops due to its reduced installation requirements and independence to occlusions, magnetic field disruptions, and gimbal locks. On the other hand, it exhibits a high degree of pervasiveness, as a MoCap suit has to be worn by the practitioner. This is a significant drawback in crafts that involve human touch and tactile sensing (e.g., pottery), as MoCap gloves provide accurate readings [63,64] but have the limitation that they might obstruct the actions and sensations of the practitioner.

Optical MoCap is significantly less pervasive, as only markers are worn. This type of MoCap is more accurate than inertial, but it is sensitive to occlusions and requires a setup only possible when indoors or in spatially constrained environments. As such, optical MoCap is suitable for crafts exercised indoors without machinery that gives rise to occlusions, such as silversmithing, woodcarving, and knitting.

MoCap has been used to record and analyze practitioner motion in 3D. Multi-view optical MoCap has been proposed to capture crafting gestures in 3D [65]. RGB-D cameras were employed in [66]. Inertial MoCap accurately recorded articulated motion for crafting gestures in [67,68,69,70]. In [71], MoCap was employed for both hands and tools.

The digital assets are 4D motion recordings, called animations. The applicability of MoCap and video modalities depends on the type of environment. For the digitization of motion using video, markerless visual methods are employed [72]. Albeit significantly less accurate than MoCap, they solely require a camera and are the only way to treat archive video. Inertial MoCap is more suitable than optical in the cluttered space of workshops due to its reduced installation requirements and increased occlusion robustness.

2.3.4. Transformations

Continuous deformation measurements can be achieved through MoCap, strain gauges, and visual methods. Optical MoCap can be used by placing markers on the deformed material and analyzing their movement. Similarly, strain gauges attached to the material directly measure the amount of deformation the material undergoes. These two methods are pervasive in that they require the placement of markers or hardware on a material and may not always be applicable.

Visual methods can provide unobtrusive, continuous measurements. A depth or RGB-D camera provides direct measurements. Using conventional video, the deformation is inferred algorithmically [73,74]. In both techniques, the reconstruction is not fully 3D but 2.5D and specific to the camera view. The difference is that 3D reconstruction models the objects in three full dimensions, whereas 2.5D reconstruction represents a scene from a single perspective, with information about the distance from the viewpoint to the object points (a depth map); unlike 3D, 2.5D reconstruction does not provide information about the occluded parts of objects for the given perspective.

2.3.5. Environment Recordings

Regarding this subject, recording sensory experiences is more difficult and can greatly vary in ease between craft subjects. This work proposes self-reflective interviews that take into account the complexity of artisans’ sensory involvement with their materials and working tools. By confronting craft persons with their own recordings, we dive deeper into the craft practice to identify and textually document such experiences, and then have researchers back up these experiences, when possible, with scientific data from the literature.

2.4. Craft Documentation Technologies

2.4.1. Observation Tools

Verbal reports aim to access the cognitive processes behind actions. They are carried out either online, with the reporter talking as they work, or offline, where the reporter comments retrospectively on their performance, often prompted by an audio or video recording [75,76].

In [48], real-time verbal annotations of the ethnographer were encouraged for each recording session as soon as possible after it had ended. This urgency stems from the degradation of human memory, mainly when loaded with events and details. These annotations promote immediate reflection and a summary of actions, which assist in later assessment and comprehension.

In [77], it is proposed that logs can help researchers to search their digital records by content using a keyword search in the logs. Event logs summarize activities and short-term observations to create a narrative of the proceedings rather than a complete record. This has two outcomes: (1) an immediate review of the session that informs the next stage of the research and (2) the facilitation of a subsequent review of the material.

An ethnographic approach to understanding the crafting process considers it from a problem-solving viewpoint [78,79]. From this perspective, the abstraction of a process schema can be treated using activity and algorithmic modeling tools. Interviews are widely used in this context. Unstructured interviews are useful for establishing activity, rapport, and overviews [75].

Interview recordings contain information provided by practitioners about their work. Interviews play a significant role in gathering in-depth insights and understanding about the crafting process, artisans, practices, and beliefs as well as the cultural context surrounding the craft.

Craft ethnography recognizes the importance of capturing artisan experiences, stories, and knowledge. Interviews serve as a bridge between researchers and artisans, enabling the documentation of craft traditions while honoring the cultural context and preserving the authenticity of the craft practice.

LCT [80] is a sociological framework for analyzing career trajectories and professional biographies within a life course context. It conceptualizes an individual’s life as a sequence of social events and roles [81,82] shaped by historical, social, and personal factors [83].

2.4.2. Representation

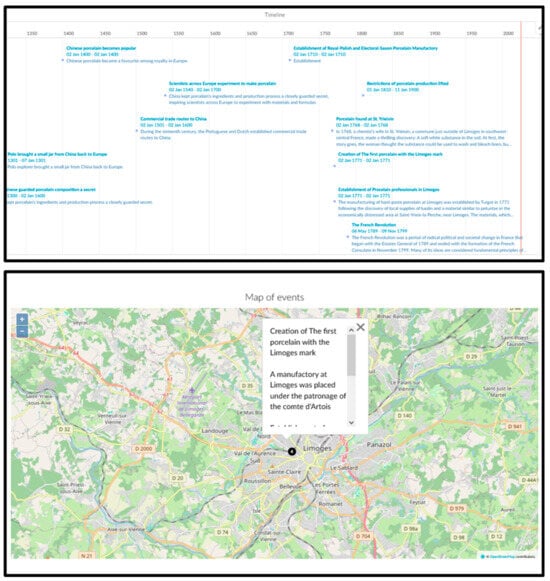

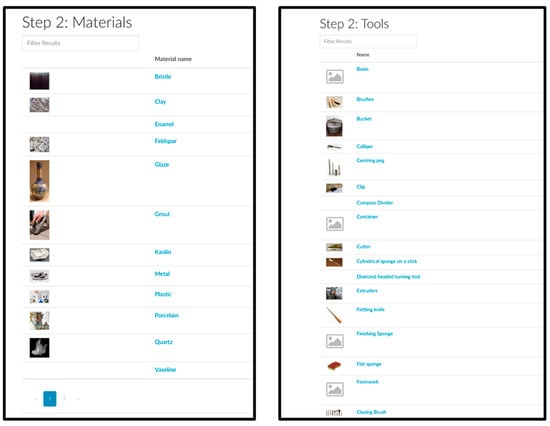

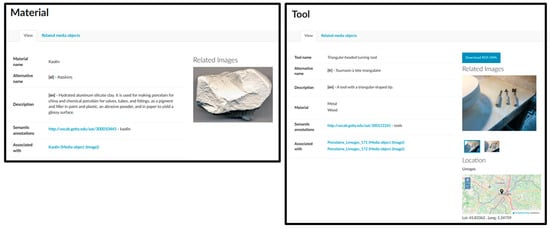

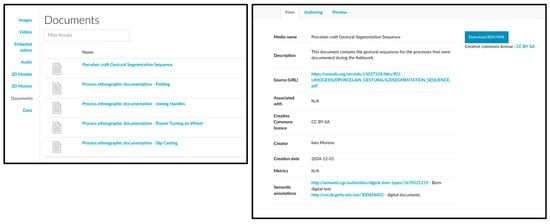

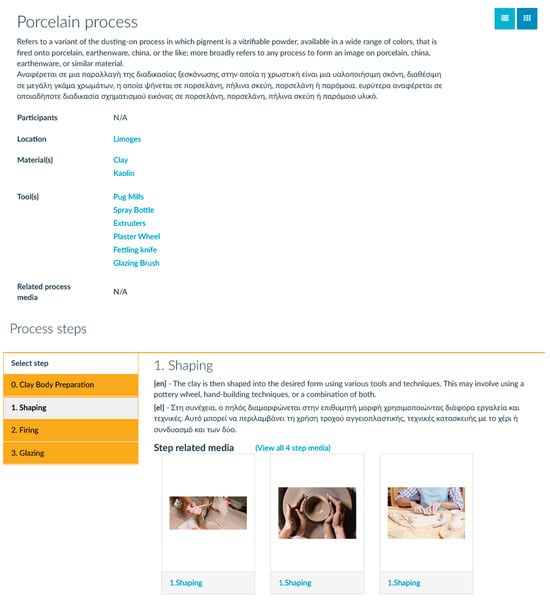

A protocol for the representation of traditional crafts and the tools to implement it are proposed in [7]. The proposed protocol is a method for systematically collecting and organizing digital assets and knowledge, representing them in a formal model, and utilizing them for research, education, and preservation. A set of digital tools accompanies this protocol, enabling the online curation of craft representations. Following this approach, knowledge about crafts is classified into two topics: (a) craft practice and (b) craft context.

Knowledge about craft practice regards the actions, tools, and materials involved in transforming materials into products. This knowledge also includes a wide range of elements relating to the education and training received by a practitioner, tacit knowledge gained from experience, material preparation recipes, and optimal sequence of process steps, which are not directly observable when looking at a practitioner working.

Craft context regards the history, traditions, and other contextual elements of the craft, such as the traditional motifs and aesthetics utilized in craft products. This knowledge can differentiate between the local expressions of a craft, as the materials, aesthetics, and local history may differ from one community to another.

In [37], it was pointed out that modeling crafting processes may have decision points (and, thus, alternate workflows) and parallel or combined activities conducted by one or more persons. Some steps take place only to handle exceptional events, such as a repairing a mistake or an accident. We follow this approach in modeling crafting processes with activity diagrams, and use it to convert them into interlinked semantic knowledge entities.

3. Proposed Method

In this work, a method is provided for recording craft gestures. Its objective is to outline the methodology and procedures for recording and analyzing professional gestures. This protocol guides the ethnographic capture and study of practitioners’ movements to gain insights into their expertise and the details of the human movement to be recorded.

3.1. Fundamental Concepts

Establishing trusted relationships with practitioners is considered a foundational element of this methodology. Before initiating any documentation, the research team should conduct preliminary visits to craft workshops and conduct informal discussions with artisans. These interactions are crucial in communicating the goals of the research, ensuring transparency, and fostering mutual respect. Informed consent should be obtained not only through formal channels but also through ongoing dialogue throughout the study. Craft practitioners should be treated not as subjects of observation but as collaborators whose input actively shapes the recording and interpretation processes. By involving practitioners in the planning, selection, and annotation of crafting actions, the research methodology is rooted in reciprocity and co-ownership, aligning with ethical standards in ethnographic research [84,85].

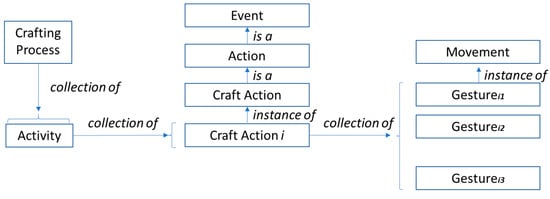

An action is an event that consists of doing something intentionally by some agent of action. Crafting actions refer to transforming materials into intermediate or final craft products. A gesture is an expressive or nuanced movement employed by an action. An action may employ multiple gestures. While actions are primarily functional, gestures can carry an element of personal style, tradition, or bodily adaptation to a tool or material. An activity is a set of actions. Actions and activities are events. A crafting process is a set of activities that transform materials into craft products. A workflow is an orchestrated and repeatable activity, enabled by organizing actions into processes. An overview of the aforementioned relationships is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Overview of fundamental principles employed by proposed representation.

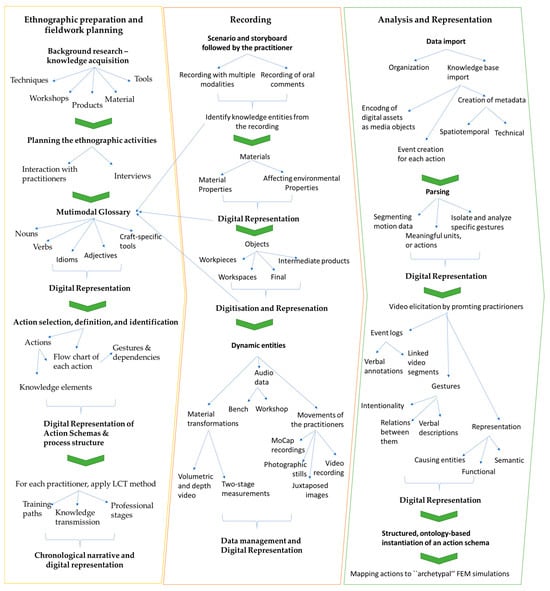

3.2. Overview of the Proposed Method

The proposed methodology is presented in Figure 2. It follows a structured, interdisciplinary approach to documenting, analyzing, and digitally representing traditional craft processes. It begins with ethnographic preparation and fieldwork planning, which lays the foundation for effective data collection. This phase involves conducting background research to understand the specific craft, including its techniques, tools, materials, workshops, and products. Prior knowledge is crucial as it helps researchers engage meaningfully with practitioners and accurately interpret their techniques. To facilitate interdisciplinary collaboration and ensure consistent terminology, a multimodal glossary is created. This glossary includes nouns and verbs describing manufacturing processes, craft-specific tools, and idioms unique to particular cultural or technical contexts. It is enriched with multimedia elements to illustrate nuanced concepts that may not be effectively conveyed through text alone. Additionally, the LCT method is employed to analyze how knowledge is transmitted, how practitioners develop expertise over time, and how professional trajectories evolve. This allows for a deeper understanding of how craft knowledge is acquired and sustained.

Figure 2.

Method overview.

Once the foundational knowledge has been established, the methodology moves into the recording and digital representation phase. Here, researchers work closely with practitioners to select and define key crafting actions. This process involves breaking down actions into their fundamental gestures and understanding their dependencies and sequential relationships. Flow charts and process diagrams are co-designed with practitioners to ensure they align with traditional ways of thinking about the craft. Digital representations of these action schemas help structure the documentation process. In the next step, researchers capture and digitize the craft process using a combination of audiovisual recording, MoCap, and other sensing modalities. A structured scenario and storyboard guide the recordings, ensuring consistency across different practitioners and settings. The recording setup is designed to capture not only the motions of the practitioner but also the transformations that occur in the materials they manipulate. This includes recording dynamic entities such as material deformations, changes in texture, and environmental interactions. Tools such as volumetric video, depth video, and photographic stills are used to document these transformations comprehensively. Furthermore, the digital representation extends beyond the practitioner’s movements to include objects, workpieces, and workspaces. These elements are digitized to provide a complete understanding of the crafting environment and its impact on the practitioner’s workflow.

After the recording phase, the analysis and representation step begins. The collected data are systematically organized and imported into a knowledge base, where they are annotated with metadata. Parsing techniques are applied to segment the motion data into meaningful units, allowing researchers to isolate and analyze specific gestures. This segmentation is crucial for developing structured representations of crafting actions. To enhance understanding, video elicitation techniques are employed, where practitioners watch and comment on their recorded actions. These verbal annotations provide insights into the cognitive processes, intentions, and decision-making strategies behind each movement. This phase also includes structured semantic annotation, linking gestures to broader action schemas and functional relationships.

The final step of the methodology involves the structured digital representation of craft knowledge. Actions are modeled within an ontology-based framework, ensuring that relationships between materials, tools, and gestures are clearly defined. These representations serve as a foundation for further analysis, training, and digital preservation. Additionally, actions are mapped to “archetypal” Finite Element Method (FEM)-based simulations, which allow researchers to model the physical principles underlying each craft action. This simulation-driven approach helps validate the documentation and enables practitioners to experiment with digital models of their work.

4. Method Analysis

4.1. Ethnographic Preparation and Fieldwork Planning

Preparatory actions are proposed before engaging in fieldwork. The purpose of these actions is to ease and optimize the ethnographic tasks.

4.1.1. Background Research

Prior knowledge of a craft catalyzes ethnography with practitioners and is available through secondary sources. Background reading on the craft processes is recommended to create a solid engagement among researchers, anthropologists, and craft practitioners, facilitating the accurate analysis of the observed techniques. If the specific craft instance may not have been studied, similar ones may have. Social and historical context provides an understanding of the materials used, the motifs used to decorate artifacts, and the traditions related to the craft instance. A guide to conducting this background research and collecting contextualization information can be found in [7].

The next step concerns understanding the studied craft and developing a plan for the ethnographic activities. This understanding is achieved through interaction with practitioners in workshops and interviews. Practitioners explain and identify workspaces, actions, processes, tools, materials, and anticipated results, such as finished craft products, treated materials, etc. They explain material qualities and how these are perceived through the senses. They convey the criteria for judging the successful completion of actions and methods for correcting mistakes.

4.1.2. Multimodal Glossary for Craft Documentation

A multimodal glossary is authored with practitioners in order to facilitate collaboration and communicate outcomes across disciplines and general audiences. This glossary ensures that terminology remains consistent across disciplines and serves as a (crossdisciplinary) tool for effective communication and craft documentation. The verbal basis of this glossary is the nouns and verbs required to describe the manufacturing process, craft-specific tools, and idioms that are either culture- or craft-specific. In addition, adjectives describe qualities and perceptual properties.

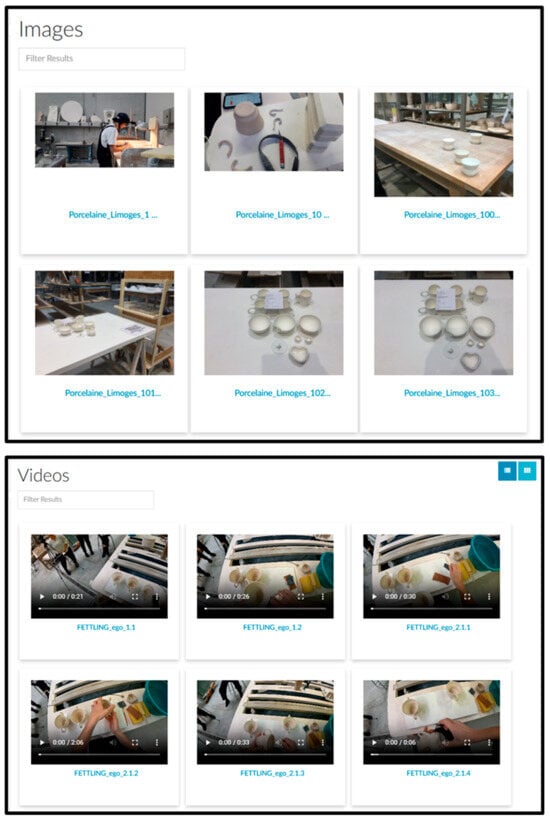

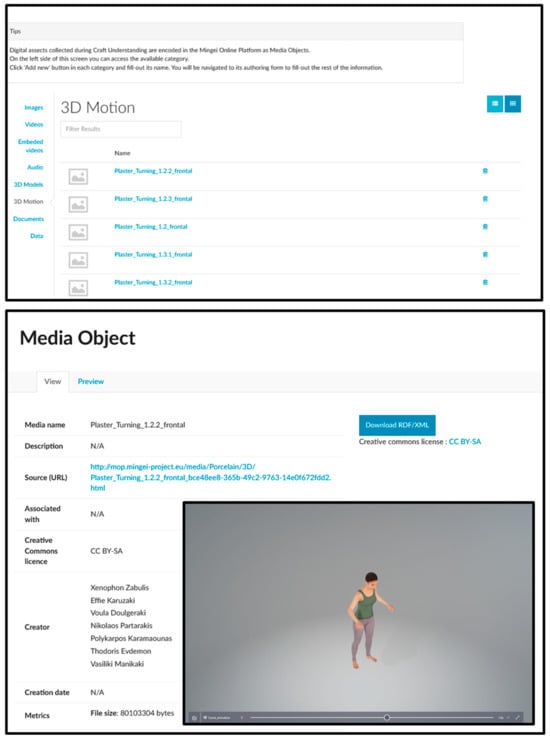

The multilingual glossary uses multimedia to illustrate the featured terms, facilitating the accurate documentation of craft nuances that may not be adequately conveyed through text alone. The terms and their definitions are multilingual and include idioms and emic names. Each entry is associated with a thesauric entry and digital assets that illustrate it. The MOP is used to register this information and these associations, as in [86]. The digital assets are acquired from ethnographic recordings and, when appropriate, from authoritative sources.

Each entry in the vocabulary is associated with an entry in the Getty AAT [87] or UNESCO thesaurus [88]. This association enables the multilingual representation of terms.

The forthcoming analysis of practitioner motion introduces a vocabulary of gestures. This kinematic vocabulary can overlap with the glossary discussed here, as particular gestures can be named in the context of a craft instance.

4.1.3. Action Selection, Definition, and Identification

The representative actions of the artisanal expertise are selected by the practitioners themselves, enabling the research team to better understand the execution, purpose and effects of their gestures. This helps us establish a vocabulary of the actions and gestures to be recorded and how each recording modality should be installed. To systematically document this selection, we create flow charts of the actions, prescribing the gestures, their order, and the causal relations between them. Co-designing this chart with practitioners is important in order to ensure it represents their mental models for the actions. Moreover, consulting mechanical engineering literature is required to map the prescribed actions and to know functional models that describe their behavior under the influence of practitioner actions.

At this stage, we use the chart and its annotating information to identify the following: (1) the body parts involved and the significance of each; (2) the characteristic gestures, visualizing their dependencies within the action; (3) the characteristic motions and their temporal expression. For each action, we identify the knowledge elements needed to describe the action. These are the causes, the affected entities, and the environmental conditions. We name and instantiate them in the MOP as knowledge entities. The MOP is a web-based authoring platform for the representation of traditional crafts. Its knowledge representation framework builds on top of the CIDOC-CRM, extending to support the representation of narrative, process schemas, and processes. The MOP has been being implemented as part of knowledge representation activities in traditional crafts for more than 5 years in the context of the EU-funded projects by Mingei [89] and Craeft [90]. Currently, the MOP has representations of more than ten traditional craft instances and is expanding [91].

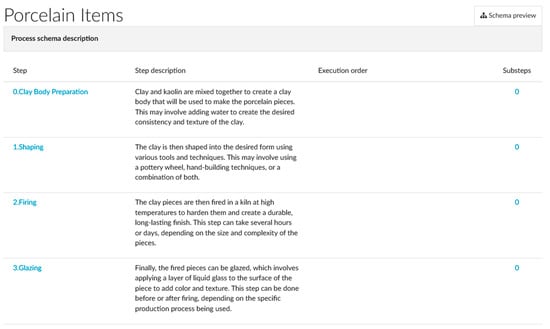

The planned action is represented as an action schema knowledge element. The action is represented as a knowledge element of the event type. These knowledge entities are instantiated in the MOP and the aforementioned entities are assigned to them. In addition, action events can be members of crafting process representations [37].

4.1.4. Documentation of Process Structure

We use a scenario structure to decompose the crafting process into actions. We segment the activity into actions based on the principle that an action is the unit activity identified by the practitioner [92]. Like the flow chart, the scenario is co-designed with the practitioners.

A rough outline of the scenario of each action is developed, using a “three-act structure” [93]. In the first act, “Setup”, we record the tools, materials, and workspace. In the second, “Negotiation”, we record the practitioner’s interaction with the transformed material. In the third act, “Resolution”, we record the outcome of the action. The scenario for the crafting processes concatenates individual action scenarios chronologically.

The scenario identifies the action-specific workspace, objects, and workpiece, describing how the action should be performed and its outcome. Additionally, the scenario may indicate challenging parts of actions to guide their recording. A storyboard can be optionally produced based on the scenario to facilitate recording.

At this stage, we connect the action event schemas and action events with transitions, as in [37]. The scenario is accompanied by a list of terms to be digitized in order to identify and enumerate the items in the scene.

4.1.5. Personal Context

The LCT approach of inquiry is employed for each practitioner. Focus is placed on training paths, knowledge transmission, and professional stages. This analysis enables us to understand the overlaps between their technical and social dimensions. The practitioner’s professional life is represented as a chronological narrative, using the method and online system proposed in [94].

4.1.6. Relationship Building and Ethical Engagement

An essential component of the ethnographic preparation involves the cultivation of respectful and collaborative relationships with craft practitioners. This is achieved through repeated visits, open-ended conversations, and the development of rapport prior to any formal documentation. By investing time in understanding the workshop dynamics, personal histories, and working rhythms of practitioners, the research team can ensure that documentation is not extractive but grounded in trust.

Practitioners are invited to participate in shaping the narrative and structure of their craft’s documentation. Their perspectives inform not only the selection of key actions and gestures but also the vocabulary and frameworks used in their representation. Informed consent is treated as an ongoing, negotiated process rather than a one-time formality. It includes verbal and written consent and should be revisited at key stages of documentation and publication. Techniques such as video elicitation and self-confrontation interviews further empower practitioners to reflect on and contribute to the interpretation of their work. This relational approach is critical to avoiding the pitfalls of observational extractivism, as documented in studies of ethnographic work with Indigenous and non-Indigenous artisan communities alike [95,96]. It ensures that practitioners feel that they are respected, their knowledge is valued, and their agency is preserved throughout the process.

To ensure that documentation is non-intrusive and respectful, the selection of equipment and recording methods should be discussed with artisans in advance. For instance, when body-worn sensors are used, practitioners should be invited to rehearse with the equipment and provide feedback on comfort and naturalness. Any discomfort or reluctance will lead to adjustments in the documentation method. This iterative adaptation helps ensure that the recordings reflect authentic practices while minimizing disruption.

Artisans should actively contribute to the co-design of the process diagrams, multimodal glossaries, and annotation vocabularies. During video elicitation sessions, they can reflect on their gestures and narrate their thought processes, which informs not only the interpretation of their movements but also the design of future recording protocols. These collaborative strategies foster a sense of co-ownership and affirm the practitioner’s role as a knowledge-holder rather than merely a subject of study.

Ethical considerations extend to data management. All recorded data should be anonymized when necessary and stored with restricted access. Practitioners can be given the option to use pseudonyms, and any identifying features can be excluded from public-facing datasets when requested. The digital materials are then archived in compliance with Creative Commons licensing and accompanied by documentation explaining their intended use and origin.

4.2. Recording

The scenario and storyboard are followed by the practitioner(s) in the recording. The practitioner follows the scenario, and the process is recorded from the prescribed modalities. Oral comments that will facilitate later analysis are also noted during the recording. The knowledge entities documented from the recording assets are preliminarily identified as those that need to be completed.

4.2.1. Materials and Objects

We digitize the materials and the objects to simulate and understand their role in the physical phenomena governing the transformations in crafting processes.

Materials

Materials are digitized through their properties and the environmental properties that affect them. They are retrieved from authoritative academic databases or measured. Common material properties in crafts are density, plasticity, elasticity, damage behavior, and melting and freezing points. Materials are isotropic or anisotropic, referring to the uniformity in the physical properties of materials in different directions. Glass and metals are isotropic materials, while marble and wood are anisotropic. Semantically, materials are annotated with thesaurus references. Predefined materials are automatically referenced in the Getty thesaurus.

Objects

Objects are the workpieces, workspaces, tools, and final and intermediate products involved in the represented actions. Digitizing their geometry employs the technologies reviewed in Section 2. All objects are photographically documented to capture their conventional appearance and weighted to estimate their momentum when needed (calculated by multiplying the mass of the object with its speed). Workpieces may be digitized multiple times at intermediate stages of their processing and final state.

As knowledge elements, objects are represented through their 3D geometry, material properties, and state. An object’s state includes the dynamic properties of the object, such as its location and geometry. Objects are semantically annotated with their common names using the thesaurus references collected in Section 4.2. Moreover, they are annotated with the materials they are composed of, associating them with the corresponding knowledge entities instantiated in Section 4.3. A knowledge element is created automatically and encapsulates this information, linking to the corresponding knowledge elements.

4.2.2. Dynamic Entities

Craft practices embody dexterity and are characterized by skilled hand gestures, tool manipulations, and interactions with craft objects. For the digitization of such attributes, it is essential to document not only the final, materialistic outcomes of the craft process but also the process through which these outcomes occur. This includes photographic stills, video, and sound recordings, as well as material deformation.

Stills

Photographic stills are recorded in order to capture key moments of the crafting process, highlighting characteristic gestures, tools, and materials. These stills can be acquired individually or extracted from the captured videos. The juxtaposition of images provides visual summaries of craft gestures, which are then annotated to illustrate specific points, enhance clarity, and focus on important details.

Practitioners’ Motion

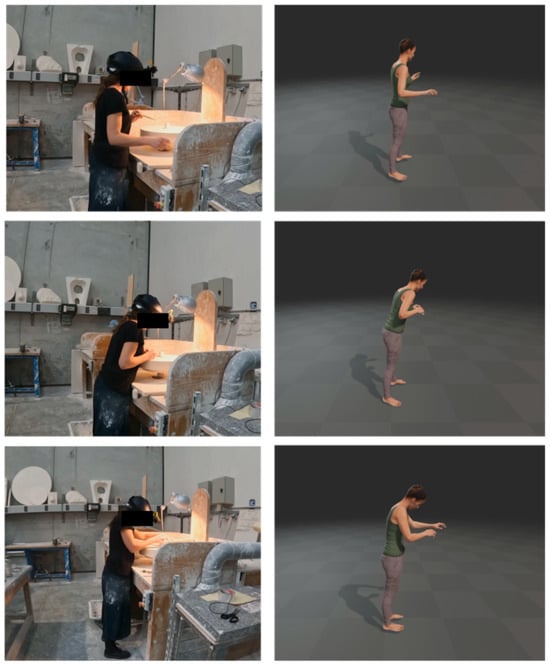

To meaningfully digitize craft practices, it is essential to go beyond static representations and capture the dynamic, embodied nature of manual work. This includes the recording of body postures, as well as the gestures of the craft practitioner involved in the crafting process, through video and other motion-capturing techniques. This provides rich information on the way that expertise is enacted through movement, meaning the way that hands interact with tools and work objects, how actions evolve, etc. This information can lead to valuable observations concerning the modeling of the temporal and spatial dimensions of the respective craft, facilitating its preservation and transmission.

Concerning the motion-capturing process and the video modality (here, RGB-only), two different cameras are deployed, one with an egocentric (mounted on the head of the practitioner) and one with an exocentric view. The egocentric view captures the dexterous movement of the hands, as well as the specific tools used and everything that is in the visual field of the craft practitioner. On the other side, the exocentric view can record the ample movements of the craftsperson and their interaction with the environment or their collaboration with other practitioners.

In some cases, Inertial Measurement Units are also deployed through a MoCap suit with sensors, able to record the postures and craft movements through accelerations and rotations. This type of motion-capturing is not dependent on occlusions or limitations in the workspace, but is sometimes prone to magnetic field disturbances, making the MoCap process challenging. To facilitate the processing of the recorded data, the two videos are synchronized through an external time code generator. Finally, to verify the recording of data enough to be used in machine learning, each craft routine is recorded at least five times, providing the observed variations in the craft process, even for the same practitioner.

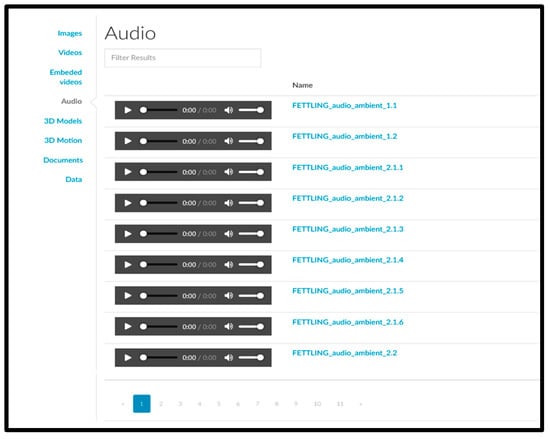

Environment Audio/Video

Along with the two video views, two microphones are also utilized, one stereo and one contact, to complement the video in the case of video occlusions and provide information on the sound of the used materials and tools.

More specifically, the stereo microphone is used to capture the sound of the tools during their use, also allowing the craftsperson to narrate during the craft process. On the other hand, the contact microphone is placed on top of the material of the respective craft (i.e., wood, marble) or the craftsperson’s workbench to capture the sound results of the interaction of a tool with the craft material through vibrations.

Transformations of Material

Digitizing material transformations assesses the “negotiation” between the maker and the material [97]. It provides insights into the mechanics of the crafting process. A quality which is often crucial in crafts is the pressure applied with or without the usage of the tool which results in a transformation. This is difficult to measure, and alternative approaches are taken, such as capturing the result of an action rather than the pressure applied during action.

Volumetric and depth video streams capture deformation across time, although they can be challenging due to occlusions. Two-stage measurements digitize the structure before and after an action. By comparing the two 3D models, the amount and location of material deformation are found. The choice of technique depends on the specific crafting action and the desired level of accuracy.

4.2.3. Data Management

Multiple media types are collected. The digital file types contain audio, video, MoCap recordings, photographs, and documents. Digital file organization is primarily event-oriented and secondarily medium-oriented. A folder for the ethnographic session (event) is organized into sub-folders for each recording modality. Digital assets are stored in these sub-folders. Their file naming convention identifies the recording modality and session. File metadata contain creation and modification dates. A spreadsheet registers participant names, IDs, and practitioner names or pseudonyms. An individual folder for this spreadsheet, session notes, fieldwork diaries, and logs is maintained during the ethnographic sessions. Organizing the data into a spreadsheet enables the automation of knowledge element creation later.

Digital assets are hosted on platforms like Zenodo due to the high costs associated with large-capacity online storage [98]. Additionally, using an online repository instead of dedicated web server storage provides several key advantages. As a cloud-based service, Zenodo ensures high availability and global accessibility. It incorporates backup and redundancy mechanisms to safeguard data integrity and continuous access. Security is also a priority, with features such as encryption, access controls, and regular updates. Furthermore, Zenodo assigns DOIs to uploaded assets and provides access analytics, facilitating asset distribution and usage tracking. It also supports compliance with Creative Commons licenses and adheres to relevant industry regulations, ensuring that data management aligns with legal and professional standards.

4.3. Analysis and Representation

The analysis of ethnographies targets the analytic identification and representation of crafting actions and their elements. Similarly to [48], we parse recordings into event logs and review them with the practitioner. We propose an action-centric representation of the crafting process, where actions are semantically and physically represented as events.

Parsing involves identifying meaningful components in a scene, such as objects, actions, and spatial relationships. Parsing enables the association of movements with entries in the gesture and action vocabularies. Articulating motion into actions facilitates understanding because individual gestures are isolated, studied, and practiced. Using these recording segments as action references, crafting processes are understood as action sequences, rather than continuous streams of human movements.

Our inquiries aim at the causes of each crafting action in order to identify the physical entities that bring about the changes induced by that action. These entities are events, constraints, or potentials, such as forces (incl. gravity), heat, moisture, chemical agents, or time. Per action, the physical entities involved are identified and semantically annotated. We additionally inquire about subjective events, such as the force exercised, the stimuli attended, the intention, and the expected outcome of the action.

4.3.1. Data Import

The data collected in Section 5 are organized and imported into the knowledge base. Spatiotemporal and technical metadata are automatically created for the assets. The digital assets are encoded as media objects. An event is created for each action.

The preliminary organization of entities in Section 4.2. enables the automation of knowledge instantiation. If needed, data entry forms are available for introducing additional or editing existing knowledge elements, as detailed in [7,37]. An “umbrella” event is created, and the generated action events are related by having occurred during it.

The encoding of digital assets, metadata, and semantic annotations follows the CIDOC-CRM [99]. All digital assets are viewed online and available to the ethnographer and practitioner.

4.3.2. Parsing—Segmentation of Craft Routines

In this step, the segmentation of continuous motion into meaningful snippets that correspond to respective craft actions or gestures is conducted. This process allows the researchers to focus on specific parts of interest, facilitating their documentation, analysis, and reuse. In the use cases in this work, segmentation was partially defined by the available contextual information, the tools, work objects, and the general spatial arrangement of the respective craft working stations. Segmentation is not treated as a purely technical task, but as an iterative process that starts from a detailed discussion with each craftsperson and an exchange among ethnographers and technical-oriented experts. The main actions and gestures are identified through these discussions and directed in the recordings themselves.

Parsing is performed with the practitioner. Practitioner input is integrated into each data interpretation stage, particularly during segmentation, ensuring that the contextual meaning behind each action is accurately captured and reflected in the simulation. During parsing, the ethnographer’s notes help determine action boundaries and are cross-referenced with video segments to refine segmentation and interpretation. AnimIO [100] is used to delimit motion recordings into segments and annotate the motion data of the recorded action.

4.3.3. Video Elicitation

As mentioned earlier, the segmentation and annotation of the recorded data is an iterative process that starts with thorough discussions with the respective craft practitioners and concludes by showing the egocentric recordings to the respective craftspeople for the real-time narration of the crafting process, their decisions, their actions, and their intentions.

We use video elicitation techniques to prompt practitioners to verbalize their actions and gestures while watching the recorded videos. Specifically, we use event logs as a record that can be referred to when studying and sharing data [48]. Event logs are verbal annotations that describe the contents of an ethnographic video, temporally corresponding to segments of said video [48]. Event logs promote immediate reflection and a summary of actions, which assist in later assessment and comprehension. The logs summarize the activities in the corresponding video segment.

The content of these logs is derived from the practitioners’ responses to prompts for verbalizing their actions and gestures. In addition, the practitioners are invited to describe the gesture and intentionality of each action through the relations between them. This self-confrontation interview method [101] prompts detailed discussion because participants relive the activity while watching and thinking about themselves working. The imagery re-immerses the practitioners in their activity, confronting them with the recorded gestures [50], and triggering comments on intentions, goals, and decision-making processes. Moreover, we found out that recording is a way for practitioners to observe themselves and further understand how their work is perceived.

The practitioner’s comments are compiled into text and associated with each action. This technique enables access to the practitioner’s cognitive processes, intentions, and decision-making while performing specific gestures. Verbalization adds a valuable layer of insight, enhancing our understanding of the practitioners’ movements beyond what is visible in the recordings alone.

In the video elicitation interview, we accompany practitioners through the process of articulating and analyzing their intentions in detail. Moreover, we pose open-ended questions to stimulate detailed verbalization of the practitioner’s actions and the meaning behind their movements. This way, we explore the practitioner’s perceptions of hierarchical structures within their movement repertoire and how they prioritize different gestures.

We collect the verbal descriptions of the recorded technical acts in an interview with the practitioner after the recording. The main questions are as follows:

- What are the characteristics of the action performed?

- Is the action recording accurate and in accordance with the action you perform in your daily practice? Do you observe any deviations due to the usage of capturing equipment?

- What are the gestures that comprise this specific action?

- What is the variability of the gestures from one practitioner to another?

- Are there other actions in which this gesture is used?

- What kind of tools are used, and what are their characteristics?

The temporal annotation and synchronization of recordings are facilitated by the AnimIO software v1.0 [99], which was used earlier in the process to create motion segments. This segmentation triggers the partitioning of the recorded data channels based on action timestamps. The outcome is a set of timestamps delimiting actions in the video. The resultant segments are annotated as media object segments. An action event is instantiated in the knowledge base and the corresponding media object segments are linked to it as its recordings. The knowledge elements representing the objects involved in the action are also linked to this event.

Event logs obtain an immediate review of the session to facilitate the subsequent material review. We recommend authoring event logs either during observation or as soon as possible after it. The purpose of this is to counter the decay of human memory, as details will have already been forgotten when the video is reviewed.

4.3.4. Representation of a Craft

Representing causing entities as knowledge elements associates their functional and semantic counterparts. The result is a structured, ontology-based instantiation of an action schema. In the ontology, causing entities are represented as events that affect the object (physical entities) in the simulated scene.

We identify and model the causes of actions, such as forces, motions, friction, heat, moisture, ventilation, chemical agents, and others, based on the video elicitation responses. Following [37], actions are classified as additive/subtractive, interlocking, and free-forming. These causal relationships are validated by analyzing video recordings alongside MoCap data, allowing for the identification of key physical variables such as applied force, friction coefficients, and material deformation. Although identifying causing entities is straightforward, their quantification can be challenging. For example, muscle forces exerted by the practitioner are difficult to measure. Instead, modeling tool motion as the causing entity is more efficient. This is due to the fact that tool motion can be measured easily with computational methods from the video.

An online platform documents these knowledge entities as objects, events, and the relations between them. The semantic annotation of the knowledge elements provides linguistic references and thesaurus organization for the represented knowledge. Completing the online template triggers the instantiation of the corresponding knowledge elements.

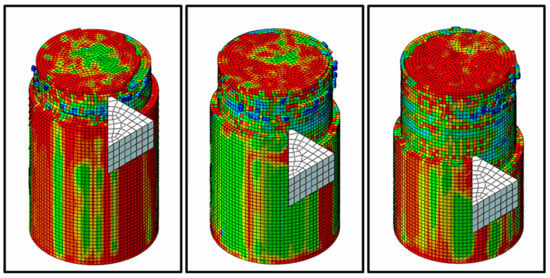

In addition, we investigate the similarity of the described gestures with similar gestures found in other crafts. In [102], actions are mapped to “archetypal” FEM-based simulations, abstracting elementary crafting actions. The schema translates these archetypes into executable simulations with specific objects, shapes, gestures, and materials. The 3D models are converted from surface to volumetric meshes to be used in simulations [92]. These elements are enriched with attributes that represent physical material properties. In this way, we can validate the representations. A simulation of the execution of an action is a virtual action.

5. Use Cases

The method proposed by this work was formulated by working closely on eight diverse European craft practices—glassblowing, tapestry weaving, woodcarving, porcelain production, marble carving, silversmithing, pottery, and wool textile crafts.

These practices, spanning France, Greece, and Spain, offered insight into shared technical knowledge, corporeal engagement, and the dynamic relationship between material, tool, and body. The comparative approach fostered inter-professional dialogue and highlighted commonalities across disciplines, allowing us to address a wide range of ethnographic interests/concerns in our proposed methodology.

5.1. Use Case Selection

Glassblowing in Nancy, France, has been recognized by UNESCO for its rich heritage. The region is home to over 150 craftspeople, multiple crystal manufacturers, and specialized training centers. Cerfav plays a central role in safeguarding and innovating glassmaking techniques. This project documented the making of a glass tumbler, a fundamental exercise for apprentice glassblowers. The study also tested video elicitation, providing artisans with new perspectives on their gestures and improving interdisciplinary collaboration between ethnographers and engineers.

Aubusson tapestry weaving, a UNESCO-listed craft, thrives in the Creuse region of France. This traditional practice involves a complex production chain, from wool processing to tapestry restoration. This project focused on the “warping process”, where weavers separate warp threads with a foot treadle, pass the weft through, and use a beater to ensure even tension. The study also explored sustainability within the craft, considering the entire wool production cycle and its implications for ICH.

Yecla, Spain, is renowned for its industrial furniture production and traditional woodcarving. CETEM, a key institution in wood and furniture manufacturing research, provides industrial and craft training, ensuring the preservation of woodcarving techniques. Yecla furniture carries a quality certification, emphasizing the region’s commitment to craftsmanship. This project documented techniques used in creating sculptures from repurposed wood, reflecting both heritage and innovation.

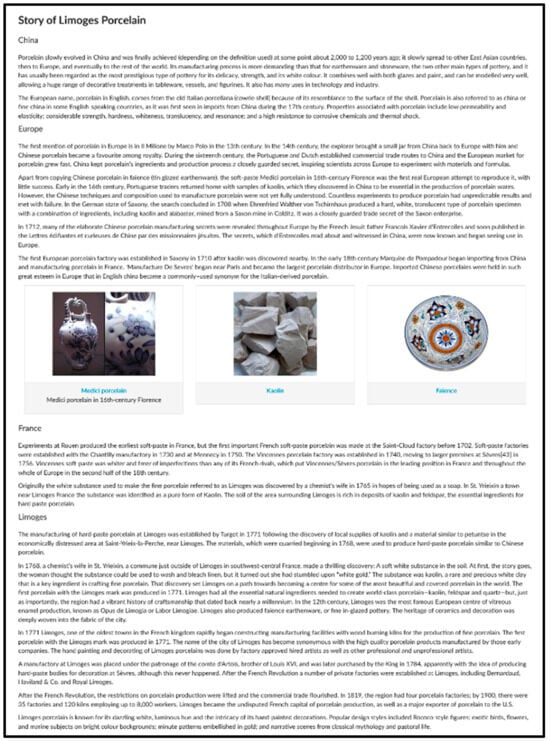

Limoges, designated as a UNESCO Creative City of Crafts and Folk Art, has been a center for porcelain production since the 18th century. Porcelain activity is supported by a network of manufacturers, craft professionals, research centers, and educational institutions. The CRAEFT project focused primarily on shaping gestures—such as plaster turning, slip-casting, handle joining, and fettling—which were documented in collaboration with the École Nationale Supérieure d’Art et de Design in Limoges. This distinctive context enabled the observation of both traditional and contemporary approaches to porcelain craft.

Marble carving in Tinos, Greece, boasts a long-standing tradition, deeply embedded in the island’s cultural identity. Tinos is home to skilled artisans who pass down knowledge through hands-on apprenticeships. Our documentation emphasized carving gestures, tool handling, and the adaptation of traditional techniques to contemporary artistic and architectural contexts.

Epirus, Greece, is renowned for its intricate silversmithing traditions, blending Byzantine and Ottoman influences. This study examined metalworking techniques, including forging, engraving, and filigree. The research also addressed the role of guilds and family workshops in sustaining craftsmanship and adapting to modern markets.

Margarites, located in Rethymnon, Crete, is a historic pottery village with a legacy of ceramic craftsmanship dating back centuries. The Kerameion workshop, among the most prominent in the area, preserves and innovates traditional clay pottery techniques. This project documented the shaping, drying, and firing processes used to create both functional and decorative ceramics. Particular attention was given to the artisans’ dexterity in wheel-throwing and hand-sculpting, as well as the integration of natural pigments and glazing techniques passed down through generations.

Traditional wool textile weaving on Crete remains an essential craft, particularly in rural areas where handlooms are still in use. This study focused on the intricate techniques of warp and weft weaving, pattern creation, and the use of natural dyes derived from local flora. Women artisans, often the primary custodians of this craft, demonstrated the careful process of preparing and spinning wool before weaving it into elaborate textiles used for garments, blankets, and decorative pieces. This craft represents a crucial aspect of Crete’s cultural identity, balancing preservation with modern adaptations for contemporary markets. This comparative study of representative craft instances demonstrates the interconnectedness of European artisanal traditions and their evolution in response to technological and cultural shifts.

5.2. Mechanical Characterization of Use Cases

Mechanical characterization typically involves studying the mechanical properties and behaviors of materials. These properties are crucial in understanding material behavior under different conditions and loads.

This project focused on simulating and preserving traditional crafts through three core actions: digital reenactment, craft-specific simulators, and archetypal action principles. These actions encompass additive/subtractive (material addition or removal), interlocking (intricate material weaving), and free-form (flexible material shaping) techniques. Hands and feet serve as crucial tools and sensors in crafting. The eight crafts in focus each demand distinct mechanical skills. These skills are improved through various programs and experiences, inspired by established mentoring networks.

Table 1 offers a concise overview of how traditional crafts engage with specific mechanical actions. Craftsmanship often involves intricate and varied mechanical processes, from adding and subtracting materials to interlocking or free-form shaping them. Understanding the mechanical properties of various materials is crucial for artisans in traditional crafts. Below, we provide information about the properties of materials frequently employed in traditional crafts, ranging from glass to clay, emphasizing their distinctive attributes and behaviors.

Table 1.

Mechanical principles per craft instance.

Glassblowing: In glassblowing, artisans shape the glass by adding and subtracting material; mechanical characterization involves studying the tensile strength of the glass rods used, modeling the thermal expansion of the glass during the blowing process, and characterizing the brittleness of the glass to prevent breakage during shaping. Glassblowers master the art of transforming molten glass into mesmerizing, flowing shapes. They do this through precise 3D and 2D transformations, creating stunning glassware, sculptures, and installations.

Aubusson Tapestry: For tapestries, where materials are interlocked, mechanical characterization focuses on the tensile properties of the textile threads, modeling the load-bearing capacity of the interlocking patterns, and characterizing the elasticity of the threads to ensure the tapestry’s structural integrity. Aubusson tapestries traditionally involve the use of various materials, such as the following: (1) Wool is the primary material used for weaving Aubusson tapestries. It provides warmth, durability, and vibrant colors to the tapestry. (2) Silk is a natural fiber produced by silkworms and is known for its softness, sheen, and luxurious feel. (3) Cotton threads or fabric may be used as the tapestry’s base or backing material, providing structure, stability, etc.

Woodcarving: In woodcarving, artisans showcase their mastery by delicately subtracting material from wood. They intricately carve patterns and motifs, enhancing the wood’s beauty. They sculpt and shape wood forms with precision. In woodcarving, which involves shaping wood in a free-form manner, mechanical characterization includes modeling the stress distribution in carved wood, characterizing its hardness for carving tool selection, and analyzing the impact of moisture content on the wood’s dimensional stability.

Porcelain Pottery: Mechanical characterization involves modeling clay shrinkage during firing, assessing porcelain’s compressive strength for stability, and studying glaze thermal expansion for proper pottery fit. Porcelain pottery also includes free-form crafting. Artisans use mass-preserving, free-form 3D and 2D transformations to create unique pieces, giving free rein to their artistic expression. Clay particles stick together due to electrical forces, making them cohesive and allowing them to maintain their shape when molded. Although the mechanical characterization of porcelain, including the firing and glazing stages, can be carried out on the basis of other studies conducted as part of the project, these aspects were not studied in the ethnography conducted in Limoges.

Marble Crafts: Marble is a natural stone known for its elegance and durability. For marble crafts, which involve carving and shaping marble, mechanical characterization includes modeling the hardness and abrasion resistance of different types of marble, characterizing the tensile strength of marble slabs for large sculptures, and studying the fracture toughness of marble to prevent cracks during carving.

Silver: In silversmithing, artisans work with silver, and mechanical characterization includes understanding how silver can be shaped and its properties like flexibility for jewelry-making and jewelry. This involves studying how silver wires can be pulled into thin threads and how silver components hold up when bent and formed.

Clay: For clay pottery, which involves shaping clay in a free-form manner, mechanical characterization includes modeling the plasticity and workability of different clay types, characterizing the thermal properties of the clay to determine firing temperatures, and analyzing the porosity of clayware for glaze absorption and water retention. Clay is a versatile material with various types, each having slightly different properties. Clay can be shaped when mixed with water. This property is known as plasticity and makes clay suitable for pottery and sculpture.