The Impact of Karate and Yoga on Children’s Physical Fitness: A 10-Week Intervention Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

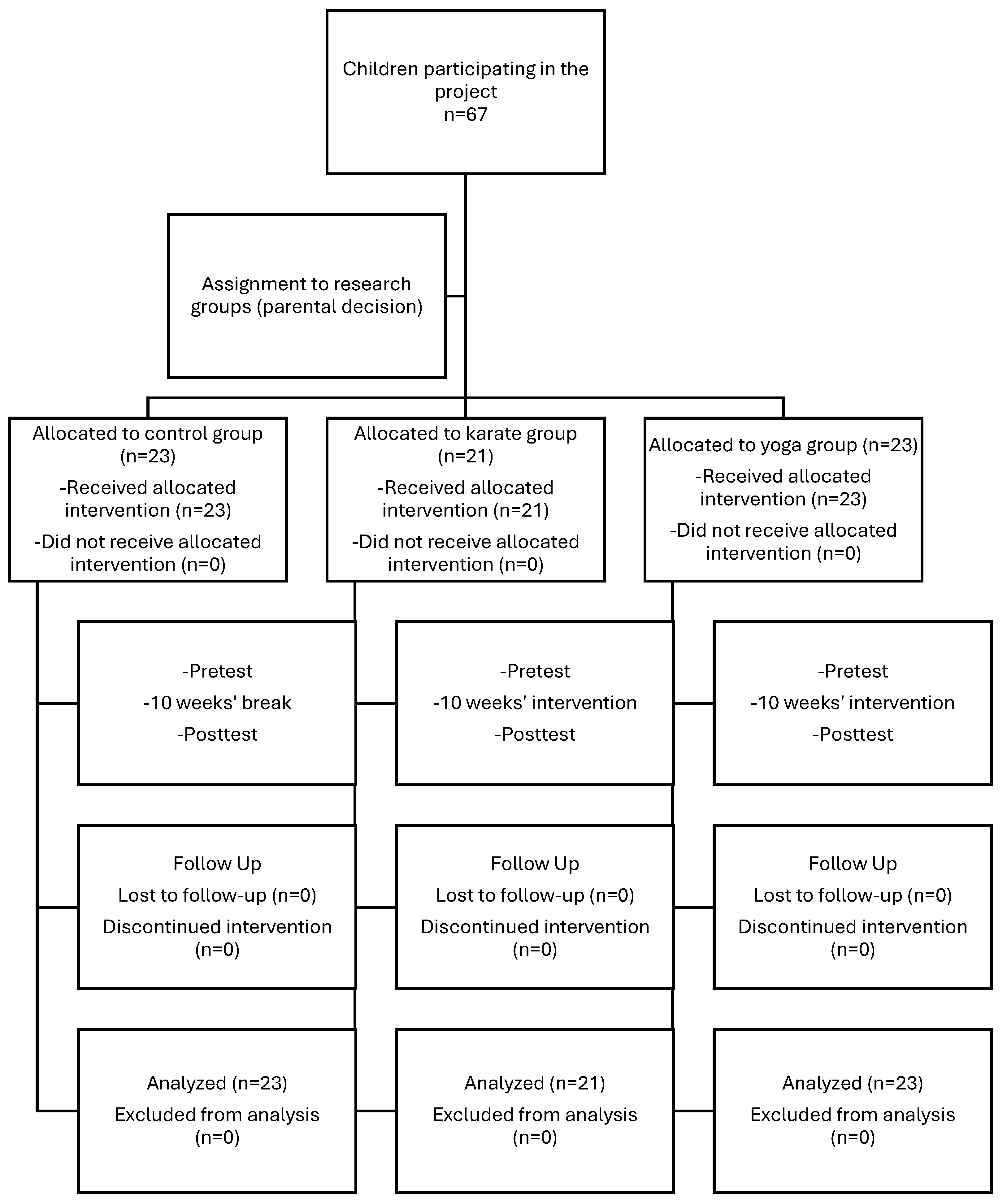

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Setting and Participants

2.2. Interventions

2.3. Assessment Methods

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chaddha, A.; Jackson, E.A.; Richardson, C.R.; Franklin, B.A. Technology to Help Promote Physical Activity. Am. J. Cardiol. 2017, 119, 149–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuksel, H.S.; Şahin, F.N.; Maksimovic, N.; Drid, P.; Bianco, A. School-Based Intervention Programs for Preventing Obesity and Promoting Physical Activity and Fitness: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kliziene, I.; Cizauskas, G.; Sipaviciene, S.; Aleksandraviciene, R.; Zaicenkoviene, K. Effects of a Physical Education Program on Physical Activity and Emotional Well-Being among Primary School Children. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alves, J.G.B.; Alves, G.V. Effects of Physical Activity on Children’s Growth. J. Pediatr. 2019, 95, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panhelova, N.; Panhelova, M.; Pyvovar, A.; Ruban, V.; Kravchenko, T.; Chuprun, N. The Influence of the Integrated Education Program on the Psycho-Physical Readiness of Children for School Education. Sport Tour. Cent. Eur. J. 2023, 6, 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidzan-Bluma, I.; Lipowska, M. Physical Activity and Cognitive Functioning of Children: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes Da Silva, S.; Arida, R.M. Physical Activity and Brain Development. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2015, 15, 1041–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthold, R.; Stevens, G.A.; Riley, L.M.; Bull, F.C. Global Trends in Insufficient Physical Activity among Adolescents: A Pooled Analysis of 298 Population-Based Surveys with 1·6 Million Participants. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2020, 4, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Guidelines on Physical Activity, Sedentary Behaviour and Sleep for Children under 5 Years of Age; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; ISBN 978-92-4-155053-6. [Google Scholar]

- Rakić, J.G.; Hamrik, Z.; Dzielska, A.; Felder-Puig, R.; Oja, L.; Bakalár, P.; Nardone, P.; Ciardullo, S.; Abdrakhmanova, S.; Adayeva, A.; et al. A Focus on Adolescent Physical Activity, Eating Behaviours, Weight Status and Body Image in Europe, Central Asia and Canada; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Weaver, R.G.; Tassitano, R.M.; Tenório, M.C.M.; Brazendale, K.; Beets, M.W. Temporal Trends in Children’s School Day Moderate to Vigorous Physical Activity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Regression Analysis. J. Phys. Act. Health 2021, 18, 1446–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutkowski, T.; Sobiech, K.A.; Chwałczyńska, A. The Effect of 10 Weeks of Karate Training on the Weight Body Composition and FFF Index of Children at the Early School Age with Normal Weight and Overweight. Arch. Budo 2020, 16, 211. [Google Scholar]

- Hedderson, M.M.; Bekelman, T.A.; Li, M.; Knapp, E.A.; Palmore, M.; Dong, Y.; Elliott, A.J.; Friedman, C.; Galarce, M.; Gilbert-Diamond, D.; et al. Trends in Screen Time Use Among Children During the COVID-19 Pandemic, July 2019 Through August 2021. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2256157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nigg, C.; Weber, C.; Schipperijn, J.; Reichert, M.; Oriwol, D.; Worth, A.; Woll, A.; Niessner, C. Urban-Rural Differences in Children’s and Adolescent’s Physical Activity and Screen-Time Trends Across 15 Years. Health Educ. Behav. 2022, 49, 789–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radesky, J.S.; Christakis, D.A. Increased Screen Time: Implications for Early Childhood Development and Behavior. Pediatr. Clin. N. Am. 2016, 63, 827–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.C.; Harvey, D.J.; Shields, R.H.; Shields, G.S.; Rashedi, R.N.; Tancredi, D.J.; Angkustsiri, K.; Hansen, R.L.; Schweitzer, J.B. The Effects of Yoga on Attention, Impulsivity and Hyperactivity in Pre-School Age Children with ADHD Symptoms. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2018, 39, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaskaran, S. A Comparitive Study on Self Confidence and Stress Tolerance Among Karate Players And Kho-Kho Players. A Glob. J. Soc. Sci. 2023, 6, 11–14. [Google Scholar]

- Yıldız, M. The Effect of Karate Practice on Stress And Self Confidence Levels: An Empirical Practice Among Sedentary Teenagers. Int. J. Eurasian Educ. Cult. 2022, 7, 1385–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Huang, X. The Effects of a Yoga Intervention on Balance and Flexibility in Female College Students during COVID-19: A Randomized Controlled Trial. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0282260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, M.; Bhat, A. Creative Yoga Intervention Improves Motor and Imitation Skills of Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder. Phys. Ther. 2019, 99, 1520–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noetel, M.; Sanders, T.; Gallardo-Gómez, D.; Taylor, P.; del Pozo Cruz, B.; van den Hoek, D.; Smith, J.J.; Mahoney, J.; Spathis, J.; Moresi, M.; et al. Effect of Exercise for Depression: Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials. BMJ 2024, 384, e075847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzęk, A.; Knapik, A.; Brzęk, B.; Niemiec, P.; Przygodzki, P.; Plinta, R.; Szyluk, K. Evaluation of Posturometric Parameters in Children and Youth Who Practice Karate: Prospective Cross-Sectional Study. Biomed. Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 5432743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alesi, M.; Bianco, A.; Padulo, J.; Vella, F.P.; Petrucci, M.; Paoli, A.; Palma, A.; Pepi, A. Motor and Cognitive Development: The Role of Karate. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2014, 4, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karpowicz, K.; Krych, K.; Karpowicz, M.; Nowak, W.; Gronek, P. The Relationship between CA Repeat Polymorphism of the IGF-1 Gene and the Structure of Motor Skills in Young Athletes. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2018, 1, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hrycyna, M.; Dąbrowska, S. Ocena sprawności fizycznej chłopców w wieku 10–12 lat. [Assessment of physical fitness of boys aged 10–12 years]. Aktywność Fiz. Zdr. Phys. Act. Health 2022, 17, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Remiszewska, M.; Miller, J.F. The Level of Somatic Development and Physical Fitness of Podlaskie Reginal Junior Olympic Taekwondo Team Members. Pol. J. Appl. Sci. 2019, 5, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madigan, S.; Browne, D.; Racine, N.; Mori, C.; Tough, S. Association Between Screen Time and Children’s Performance on a Developmental Screening Test. JAMA Pediatr. 2019, 173, 244–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biddle, S.J.H.; Asare, M. Physical Activity and Mental Health in Children and Adolescents: A Review of Reviews. Br. J. Sports Med. 2011, 45, 886–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartkowiak, S.; Konarski, J.M.; Strzelczyk, R.; Janowski, J.; Karpowicz, M.; Malina, R.M. Physical Fitness of Rural Polish School Youth: Trends Between 1986 and 2016. J. Phys. Act. Health 2021, 18, 789–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, E.T.-C.; Tomkinson, G.R.; Huang, W.Y.; Wong, S.H.-S. Temporal Trends in the Physical Fitness of Hong Kong Adolescents Between 1998 and 2015. Int. J. Sports Med. 2023, 44, 728–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini, H.; Habibi, S.; Islamoglu, A.H.; Isanejad, E.; Uz, C.; Daniyari, H. COVID-19 Pandemic-Induced Physical Inactivity: The Necessity of Updating the Global Action Plan on Physical Activity 2018-2030. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2021, 26, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amini, H.; Isanejad, A.; Chamani, N.; Movahedi-Fard, F.; Salimi, F.; Moezi, M.; Habibi, S. Physical Activity during COVID-19 Pandemic in the Iranian Population: A Brief Report. Heliyon 2020, 6, e05411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guthold, R.; Stevens, G.A.; Riley, L.M.; Bull, F.C. Worldwide Trends in Insufficient Physical Activity from 2001 to 2016: A Pooled Analysis of 358 Population-Based Surveys with 1·9 Million Participants. Lancet Glob. Health 2018, 6, e1077–e1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jodkowska, M.; Korzycka, M. Aktywność Fizyczna Dzieci w Wieku Wczesnoszkolnym w Świetle Badań COSI 2016; Fijałkowska, W., Ed.; ImiDZ: Warsaw, Poland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Nałęcz, H. Zdrowie i Zachowania Zdrowotne Młodzieży Szkolnej w Polsce; Instytut Matki i Dziecka: Warsaw, Poland, 2014; pp. 119–125. [Google Scholar]

- Żukowska, H.; Szark-Eckardt, M. Changes in The Level of Fitness and Physical Development in Children From First-Grade Swimming Classes Compared to Peers. J. Kinesiol. Exerc. Sci. 2017, 27, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutkowski, T.; Sobiech, K.A.; Chwałczyńska, A. The Effect of Karate Training on Changes in Physical Fitness in School-Age Children with Normal and Abnormal Body Weight. Physiother. Quart. 2019, 27, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Garcia, P.; Mora-Gonzalez, J.; Migueles, J.H.; Rodriguez-Ayllon, M.; Esteban-Cornejo, I.; Cadenas-Sanchez, C.; Plaza-Florido, A.; Gil-Cosano, J.J.; Pelaez-Perez, M.A.; Garcia-Delgado, G.; et al. Effects of Exercise on Body Posture, Functional Movement, and Physical Fitness in Children With Overweight/Obesity. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2020, 34, 2146–2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, Y.; Yavaşoğlu, B.; Beykumül, A.; Pekel, A.Ö.; Suveren, C.; Karabulut, E.O.; Ayyıldız Durhan, T.; Çakır, V.O.; Sarıakçalı, N.; Küçük, H.; et al. The Effect of 10 Weeks of Karate Training on the Development of Motor Skills in Children Who Are New to Karate. Front. Physiol. 2024, 15, 1347403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Age (years) | Height (m) | Weight (kg) | BMI Percentile | BMI | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Karate | Yoga | Control | Karate | Yoga | Control | Karate | Yoga | Control | Karate | Yoga | Control | Karate | Yoga | |

| Mean + SD | 11.39 (1.12) | 11.33 (1.06) | 10.78 (0.80) | 1.46 (0.08) | 1.55 (0.06) | 1.41 (0.06) | 40.16 (6.39) | 46.79 (7.40) | 38.83 (5.28) | 31.61 (14.55) | 38.81 (14.15) | 37.43 (12.23 | 18.78 (1.87) | 19.45 (2.14) | 19.44 (1.67) |

| p-value * | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.17 | 0.46 | 0.56 | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.22 | 0.07 | 0.20 | 0.99 | <0.001 | 0.22 | 0.65 |

| Min | 10.00 | 10.00 | 10.00 | 1.35 | 1.45 | 1.32 | 31.00 | 36.20 | 31.00 | 12.00 | 11.00 | 14.00 | 16.53 | 15.46 | 15.87 |

| Max | 13.00 | 13.00 | 12.00 | 1.65 | 1.68 | 1.54 | 53.30 | 61.00 | 48.50 | 71.00 | 68.00 | 66.00 | 24.67 | 23.83 | 23.39 |

| Control | Karate | Yoga | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Post | p Value | Baseline | Post | p Value | Baseline | Post | p Value | |

| Run 50 m | 31.48 (10.90) | 29.52 (11.57) | 0.18 | 38.81 (12.78) | 46.00 (12.19) | 0.02 | 35.78 (14.79) | 46.57 (18.91) | <0.001 |

| Jump | 36.65 (11.96) | 35.52 (12.64) | 0.03 | 41.76 (9.50) | 51.14 (8.87) | <0.001 | 44.74 (12.89) | 53.00 (10.74) | <0.001 |

| Run, endurance | 48.04 (16.62) | 47.13 (17.24) | 0.65 | 54.95 (14.84) | 63.71 (13.18) | <0.001 | 47.96 (16.27) | 61.00 (14.32) | <0.001 |

| Hand strength | 52.13 (7.59) | 50.91 (7.37) | <0.001 | 49.76 (4.87) | 51.24 (6.53) | 0.78 | 51.17 (7.67) | 55.43 (11.35) | 0.14 |

| Hanging | 39.78 (13.37) | 39.96 (12.04) | 0.88 | 41.95 (11.28) | 50.33 (10.13) | <0.001 | 47.30 (9.42) | 56.70 (15.19) | <0.001 |

| Run, agility | 38.30 (10.46) | 35.22 (11.84) | 0.10 | 49.48 (10.54) | 59.52 (8.20) | <0.001 | 35.22 (16.37) | 46.96 (15.13) | <0.001 |

| Sit-ups | 36.78 (10.67) | 38.00 (10.88) | 0.36 | 40.48 (7.74) | 44.90 (7.01) | <0.001 | 39.91 (9.84) | 45.70 (9.95) | <0.001 |

| Forward bend | 40.13 (4.36) | 38.70 (4.18) | <0.001 | 38.00 (6.64) | 43.95 (5.65) | <0.001 | 40.13 (8.80) | 46.78 (7.27) | <0.001 |

| Total | 40.42 (5.23) | 39.37 (5.94) | <0.001 | 44.40 (4.08) | 51.35 (4.93) | <0.001 | 42.78 (6.51) | 51.52 (6.32) | <0.001 |

| F | p | Groups | Mean Difference | SE | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total All | 35.91 | <0.001 | Control vs. Karate | −8.00 | 1.25 | −6.38 | <0.001 |

| Control vs. Yoga | −9.79 | 1.23 | −7.99 | <0.001 | |||

| Karate vs. Yoga | −1.79 | 1.25 | −1.42 | 0.33 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rutkowski, T.; Chwałczyńska, A. The Impact of Karate and Yoga on Children’s Physical Fitness: A 10-Week Intervention Study. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 435. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15010435

Rutkowski T, Chwałczyńska A. The Impact of Karate and Yoga on Children’s Physical Fitness: A 10-Week Intervention Study. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(1):435. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15010435

Chicago/Turabian StyleRutkowski, Tomasz, and Agnieszka Chwałczyńska. 2025. "The Impact of Karate and Yoga on Children’s Physical Fitness: A 10-Week Intervention Study" Applied Sciences 15, no. 1: 435. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15010435

APA StyleRutkowski, T., & Chwałczyńska, A. (2025). The Impact of Karate and Yoga on Children’s Physical Fitness: A 10-Week Intervention Study. Applied Sciences, 15(1), 435. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15010435