The Use and Impact of Virtual Reality Programs Supported by Aromatherapy for Older Adults: A Scoping Review

Abstract

Featured Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

- How have VR programs for older adults been supported by aromatherapy?

- What outcomes measures and outcomes of VR programs for older adults supported by aromatherapy have been reported in the literature?

Contributions

- Filling a Knowledge Gap: This review presents a unique synthesis of evidence on integrating VR and aromatherapy for older adults, addressing an understudied area in the literature.

- Innovative Approach: This review showcases the potential of combining VR and aromatherapy as a non-pharmacological innovative approach to improve the well-being and quality of life of older adults.

- Informing for Future Research and Practice: This review provides useful insights to guide the development and implementation of future VR studies.

2. Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

2.2.1. Participants

2.2.2. Concept

2.2.3. Context

2.3. Types of Studies

2.4. Research Team for the Scoping Review

2.5. Search Strategy

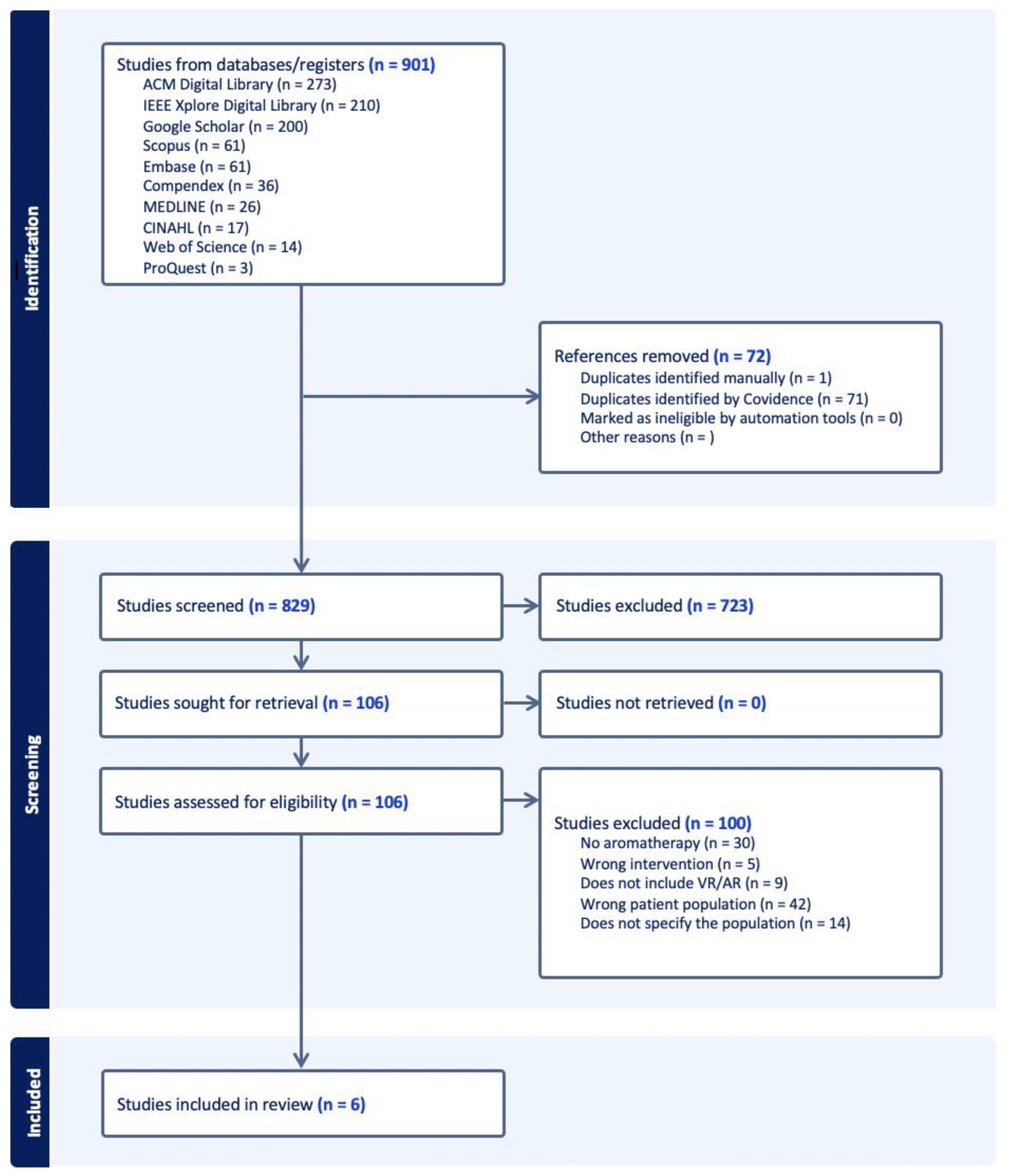

2.6. Study/Source of Evidence Selection

2.7. Data Extraction

2.8. Data Synthesis

2.9. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Design

3.2. Population, Sample Size, Setting

3.3. Interventions

3.4. Outcome Measures

3.5. Outcomes and Impacts

3.5.1. Improved Physical Awareness and Decreased Physiological Stress

3.5.2. Improved Mental and Emotional Well-Being

3.5.3. Engagement of VR Programs and Promoted Socialization

3.5.4. Enhanced Memory and Cognition

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Practical Implications

- Therapeutic and Recreational Integration: The combination of VR and aromatherapy has the potential to significantly enhance therapeutic and recreational interventions for older adults. Care providers should tailor personalized VR experiences with complementary aromatherapy scents based on individual preferences. For example, calming lavender scents for relaxation. These multisensory experiences can improve cognitive and emotional well-being, offering innovative ways to promote mental and physical health, especially in senior facilities like nursing homes and retirement communities.

- VR Aromatherapy Experience as a non-pharmacological approach: The congruence between VR content and aromas, such as the use of pine scents in forest environments, is essential for creating immersive experiences. Practitioners should consider the specific aromas used, the specific VR content, and how they match each other to maximize therapeutic benefits. For example, calming lavender and a garden for relaxation; pine and a forest for cognitive stimulation.

- Enhancing Engagement and Socialization: VR and aromatherapy interventions can improve social interactions and emotional engagement. Studies indicate that these multisensory experiences encourage personal connections, reminiscences, and socialization, making them valuable for fostering social bonds among older adults, particularly those with mobility issues or cognitive impairments [36,37,39].

- Limited Clinical Implementation Evidence: The current body of research on VR and aromatherapy lacks robust clinical implementation evidence to fully support its widespread use in practice. For example, care staff should be adequately trained in the appropriate use of VR equipment, including setup, troubleshooting, and tailoring experiences to individual preferences. Similarly, the safe and effective application of aromatherapy requires knowledge of essential oil selection, dosage, and contraindications to prevent adverse reactions.

4.3. Theoretical Implications

- Multisensory Integration Theory [52]: The findings from the studies contribute to advancing multisensory integration theory and support the need to further explore how combining multiple sensory inputs—visual, auditory, and olfactory—can enhance the user experience and improve outcomes such as memory, stress reduction, and emotional well-being.

- Need-driven behavior model: More attention should be paid to theoretical advancements in VR technology and sensory therapy in future studies by investigating how technology like VR with aromatherapy can serve as a non-pharmacological approach to address unmet needs in people with dementia and reduce behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia. According to need-driven behavior theory, many challenging behaviors in dementia stem from unmet sensory, social, or emotional needs. By leveraging immersive VR experiences to stimulate sensory engagement and pairing them with the soothing effects of aromatherapy, these interventions can provide tailored sensory inputs, meeting individual needs and mitigating stress, agitation, or apathy. Future research should also investigate the effectiveness of such interventions across diverse populations and care settings, further validating their role in improving the quality of life for individuals with dementia.

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Patient and Public Involvement

References

- National Library of Medicine. Virtual Reality. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/mesh/2023512 (accessed on 3 June 2024).

- Li, G.; Li, X.; Chen, L. Effects of Virtual Reality-Based Interventions on the Physical and Mental Health of Older Residents in Long-Term Care Facilities: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2022, 136, 104378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laufer, Y.; Dar, G.; Kodesh, E. Does a Wii-Based Exercise Program Enhance Balance Control of Independently Functioning Older Adults? A Systematic Review. Clin. Interv. Aging 2014, 9, 1803–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergmann, J.; Krewer, C.; Bauer, P.; Koenig, A.; Riener, R.; Müller, F. Virtual Reality to Augment Robot-Assisted Gait Training in Non-Ambulatory Patients with a Subacute Stroke: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. Eur. J. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2018, 54, 397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campo-Prieto, P.; Cancela, J.M.; Rodríguez-Fuentes, G. Immersive Virtual Reality as Physical Therapy in Older Adults: Present or Future (Systematic Review). Virtual Real. 2021, 25, 801–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggio, M.G.; Latella, D.; Maresca, G.; Sciarrone, F.; Manuli, A.; Naro, A.; De Luca, R.; Calabrò, R.S. Virtual Reality and Cognitive Rehabilitation in People With Stroke: An Overview. J. Neurosci. Nurs. 2019, 51, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulaei, K.; Sharifi, H.; Bahaadinbeigy, K.; Dinari, F. Efficacy of Virtual Reality-Based Training Programs and Games on the Improvement of Cognitive Disorders in Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Psychiatry 2024, 24, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, L.N.; Kim, M.J.; Hwang, W.J. Potential of Augmented Reality and Virtual Reality Technologies to Promote Wellbeing in Older Adults. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 3556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, B.; Al-Wabel, N.A.; Shams, S.; Ahamad, A.; Khan, S.A.; Anwar, F. Essential Oils Used in Aromatherapy: A Systemic Review. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2015, 5, 601–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckle, J. The Role of Aromatherapy in Nursing Care. Nurs. Clin. N. Am. 2001, 36, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunning, T. Aromatherapy: Overview, Safety and Quality Issues. OA Altern. Med. 2013, 1, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Her, J.; Cho, M.-K. Effect of Aromatherapy on Sleep Quality of Adults and Elderly People: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis. Complement. Ther. Med. 2021, 60, 102739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, S.K.; Tse, M.Y.M. Aromatherapy: Does It Help to Relieve Pain, Depression, Anxiety, and Stress in Community-Dwelling Older Persons? BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 430195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehrabian, M.S.; Tirgari, P.B.; Azizzadeh Forouzi, M.M.; Tajadini, P.H.; Jahani, P.Y. Effect of Aromatherapy Massage on Depression and Anxiety of Elderly Adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. J. Ther. Massage Bodyw. Res. Educ. Pract. 2022, 15, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Luo, Y.; Hu, Q.; Tian, X.; Wen, H. Benefits in Alzheimer’s Disease of Sensory and Multisensory Stimulation. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2021, 82, 463–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ball, E.L.; Owen-Booth, B.; Gray, A.; Shenkin, S.D.; Hewitt, J.; McCleery, J. Aromatherapy for Dementia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 2020, 1–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flavián, C.; Ibáñez-Sánchez, S.; Orús, C. The Influence of Scent on Virtual Reality Experiences: The Role of Aroma-Content Congruence. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 123, 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toimela, N. Incorporating Scents into Virtual Experiences. Master’s Thesis, Tampere University, Tampere, Finland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kaimal, G.; Carroll-Haskins, K.; Ramakrishnan, A.; Magsamen, S.; Arslanbek, A.; Herres, J. Outcomes of Visual Self-Expression in Virtual Reality on Psychosocial Well-Being With the Inclusion of a Fragrance Stimulus: A Pilot Mixed-Methods Study. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 589461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.-P.; Lee, H.-Y.; Luo, X.-Y. The Effect of Virtual Reality Forest and Urban Environments on Physiological and Psychological Responses. Urban. For. Urban. Green. 2018, 35, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, V.Y.-W.; Huang, C.-M.; Liao, J.-Y.; Hsu, H.-P.; Wang, S.-W.; Huang, S.-F.; Guo, J.-L. Combination of 3-Dimensional Virtual Reality and Hands-On Aromatherapy in Improving Institutionalized Older Adults’ Psychological Health: Quasi-Experimental Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e17096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baragash, R.S.; Aldowah, H.; Ghazal, S. Virtual and Augmented Reality Applications to Improve Older Adults’ Quality of Life: A Systematic Mapping Review and Future Directions. Digit. Health 2022, 8, 205520762211320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakhan, S.E.; Sheafer, H.; Tepper, D. The Effectiveness of Aromatherapy in Reducing Pain: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Pain Res. Treat. 2016, 2016, 8158693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, H.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, D. Application of Virtual Reality Technology in Clinical Practice, Teaching, and Research in Complementary and Alternative Medicine. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2022, 2022, 1373170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, M.; Godfrey, C.; McInerney, P.; Munn, Z.; Tricco, A.; Khalil, H. Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews. In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Aromataris, E., Munn, Z., Eds.; JBI: Adelaide, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Levine, M.E. Modeling the Rate of Senescence: Can Estimated Biological Age Predict Mortality More Accurately Than Chronological Age? J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2013, 68, 667–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. World Health Organization Ageing. In Health at a Glance: Asia/Pacific 2020: Measuring Progress Towards Universal Health Coverage; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, S.; Bajorek, B. Defining “Elderly” in Clinical Practice Guidelines for Pharmacotherapy. Pharm. Pract. 2014, 12, 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. World Population Ageing 2019; United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Archer, N.S.; Bluff, A.; Eddy, A.; Nikhil, C.K.; Hazell, N.; Frank, D.; Johnston, A. Odour Enhances the Sense of Presence in a Virtual Reality Environment. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0265039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloqaily, M.; Bouachir, O.; Karray, F. Digital Twin for Healthcare Immersive Services: Fundamentals, Architectures, and Open Issues. In Digital Twin for Healthcare; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 39–71. [Google Scholar]

- Covidence: The World’s Number 1 Systematic Review Tool. Available online: https://www.covidence.org/ (accessed on 19 May 2024).

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrard, J. CHAPTER 5 Review Matrix Folder: How to Abstract the Research Literature. In Health Sciences Literature Review Made Easy; Jones & Bartlett Learning: Burlington, MA, USA, 2022; pp. 120–138. [Google Scholar]

- Abraham, N. Wonder VR: Interactive Storytelling through VR 360 Video with NHS Patients Living with Dementia. Contemp. Theatre Rev. 2020, 30, 474–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarles, C.; Klepacz, N.; van Even, S.; Guillemaut, J.-Y.; Humbracht, M. Bringing The Outdoors Indoors: Immersive Experiences of Recreation in Nature and Coastal Environments in Residential Care Homes. E-Rev. Tour. Res. 2020, 17, 706–721. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, M.-W.; Lee, I.-J. Applying Virtual Reality Technology and Physical Feedback on Aging in Spatial Orientation and Memory Ability. In International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 564–576. [Google Scholar]

- Vanzo, R.; Moore, M.; Mantell, B. Application of Simulated Nature Intervention Using Virtual Reality and Aromatherapy on Experiences of Residents in a Retirement Community. In Proceedings of the 2020 Graduate Showcase; James Medison University: Harrisonburg, PA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bagger, B.; Sillesen, A.; Jeppesen, E.M.; Kledal, T. Virtual Reality Technology and Digitalized Forest Bathing in Nursing Care—The Experience of Well-Being and Quality of Life. Nord. Sygeplejeforskning 2024, 14, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appel, L.; Appel, E.; Bogler, O.; Wiseman, M.; Cohen, L.; Ein, N.; Abrams, H.B.; Campos, J.L. Older Adults with Cognitive and/or Physical Impairments Can Benefit From Immersive Virtual Reality Experiences: A Feasibility Study. Front. Med. 2020, 6, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angulo-Milhem, S.; Verriele, M.; Nicolas, M.; Thevenet, F. Indoor Use of Essential Oils: Emission Rates, Exposure Time and Impact on Air Quality. Atmos. Environ. 2021, 244, 117863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheok, A.D.; Karunanayaka, K. Virtual Taste and Smell Technologies for Multisensory Internet and Virtual Reality; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; ISBN 978-3-319-73863-5. [Google Scholar]

- Sattayakhom, A.; Wichit, S.; Koomhin, P. The Effects of Essential Oils on the Nervous System: A Scoping Review. Molecules 2023, 28, 3771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, M. Olfaction, Emotion, and the Amygdala: Arousal-Dependent Modulation of Long-Term Autobiographical Memory and Its Association with Olfaction: Beginning to Unravel the Proust Phenomenon? Impulse Prem. J. Undergrad. Publ. Neurosci. 2004, 1, 1–58. [Google Scholar]

- Dinh, H.Q.; Walker, N.; Hodges, L.F.; Song, C.; Kobayashi, A. Evaluating the Importance of Multi-Sensory Input on Memory and the Sense of Presence in Virtual Environments. In Proceedings of the IEEE Virtual Reality (Cat. No. 99CB36316), Houston, TX, USA, 13–17 March 1999; pp. 222–228. [Google Scholar]

- Tomono, A.; Kanda, K.; Otake, S. Effect of Smell Presentation on Individuals with Regard to Eye Catching and Memory. Electron. Commun. Jpn. 2011, 94, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, M.; Goncalves, G.; Monteiro, P.; Coelho, H.; Vasconcelos-Raposo, J.; Bessa, M. Do Multisensory Stimuli Benefit the Virtual Reality Experience? A Systematic Review. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2022, 28, 1428–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, M.J.; Herrera, N.S.; Moore, A.G.; McMahan, R.P. A Reproducible Olfactory Display for Exploring Olfaction in Immersive Media Experiences. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2016, 75, 12311–12330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gates, N.J.; Sachdev, P.S.; Fiatarone Singh, M.A.; Valenzuela, M. Cognitive and Memory Training in Adults at Risk of Dementia: A Systematic Review. BMC Geriatr. 2011, 11, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.-T. Effects of Semi-Immersive Virtual Reality Exercise on the Quality of Life of Communi-ty-Dwelling Older Adults: Three-Month Follow-up of a Randomized Controlled Trial. Digit. Health 2024, 10, 20552076241237391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-kfairy, M.; Alomari, A.; Al-Bashayreh, M.; Alfandi, O.; Tubishat, M. Unveiling the Metaverse: A Survey of User Perceptions and the Impact of Usability, Social Influence and Interoperability. Heliyon 2024, 10, e31413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maneemai, O.; Cujilan Alvarado, M.C.; Calderon Intriago, L.G.; Donoso Triviño, A.J.; Franco Coffré, J.A.; Pratico, D.; Schwartz, K.; Tesfaye, T.; Yamasaki, T. Sensory Integration: A Novel Approach for Healthy Ageing and Dementia Management. Brain Sci. 2024, 14, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author, Year, Country | Aim | Design | Population | Settings | Aromatherapy | VR Intervention | Outcome Measures | Results | Impacts |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kang (2023) Taiwan [37] | To assess whether multisensory stimulation during wheelchair use enhances spatial perception and memory in older adults. | Quantitative, RCT | Older adults (N = 6); 3 Females; Mean age 70 | Not specified | Fruit scent and meat aroma | HMD paired with Xiaomi VR glasses | Spatial orientation perception (Cosine Similarity theorem) Shape perception Memory capacity (four-item questionnaire) | Physical feedback and multisensory stimulation during wheelchair operation improved spatial orientation perception, shape perception, and memory for older adults compared to video watching alone. | Exposure to external stimuli helps older adults remember their surroundings more effectively, and incorporating olfactory stimulation further strengthens the connection between physical awareness and memory capacity. |

| Cheng (2020) Taiwan [21] | To evaluate the effectiveness of combining VR and aromatherapy in reducing stress and enhancing happiness, sleep, meditation, and life satisfaction among older adults. | Quantitative, quasi-experimental | Older adults (N = 48); 24 for each group; Mean Age: 83.03 (81.92 in the control group) | Nursing home | Not specified | 3D VR helmets | Happiness (Oxford Happiness Inventory) Stress (PSS-14) Sleep (Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index) Meditation (EOM-DM scale) Life satisfaction (Life Satisfaction Index A) | Significant improvements in happiness, stress reduction, sleep quality, meditation, and life satisfaction were observed, with similar results found among adults aged 80 and older. | The combination of 3D VR and aromatherapy enhances psychological health in older adults, with 3D VR offering greater learning opportunities than aromatherapy alone. |

| Vanzo (2020) USA [38] | To understand the sensory and occupational experiences of individuals living in retirement communities. | Mixed design, pre-post design and interviews | Older adults (N = 11); gender and age not given | Retirement Communities | Nature-based aromas (not specified) | All-In-One Oculus Quest VR headset | Stress (PSS-14) Heart rate Blood pressure | Decreases in heart rate and blood pressure were observed, while perceived stress may not show significant changes due to the limited sensitivity of the PSS-14 scale. An essential oils diffuser, paired with therapeutic-grade essential oils, is sufficient to deliver the olfactory component of the experience. | VR and aromatherapy may be effective tools for reducing physiological stress in older adults living in retirement communities. |

| Bagger (2024) Denmark [39] | To explore the experiences of mobility-constrained older adults testing VR-natureTM with forest-themed sensory stimulation (image, sound, smell) and assess its potential relevance in nursing care. | Qualitative | Older adults with physical constraints (N = 15); 8 Females; Mean Age 83.5 (71-98) | Not specified | Pine needles and essential oils | VR-NatureTM | Well-being and quality of life (interviews) | Feeling one with nature: Participants felt a sense of harmony with nature, reporting relaxation and immersion. Fluidity of space and time: Many experienced shifts in time perception, describing the experience as soothing and hypnotic. Reexperience and anticipations: VR evoked vivid memories, inspiring joyful and reflective storytelling; some faced uncomfortable memories. Changing mood with nature: Noticeable mood enhancements were reported post-experience, with participants feeling uplifted and relaxed. | VR forest bathing with aromatherapy reduces anxiety and agitation while enhancing emotional well-being in elderly individuals. It offers older adults with physical constraints in retirement communities the opportunity to experience nature virtually. Aromatherapy evokes memories and emotional connections, positively influencing mood in elderly individuals. |

| Abraham (2020) UK [35] | To explore whether custom VR 360 reduces social isolation and enhance patient well-being. | Qualitative | Older adults with dementia (N = 4); gender and age not given | NHS | Scents of pine | Bespoke VR-360 | Subject well-being (observations) | Multisensory stimuli enhance patient immersion and well-being through live interaction. Bespoke VR videos, tailored to individual needs, alleviate boredom and evoke a sense of wonder. This person-centered approach also promotes autonomy and agency in decision-making. | VR 360 provides older adults with a sense of calm and relief from the hospital environment, improving subjective well-being and reducing distress, restlessness and agitation. Tailored VR activities evoke joyful responses, engage memories, and allow patients to virtually access natural settings like forests, creating comforting, immersive experiences through multisensory engagement. |

| Scarles (2020) UK [36] | To explore how VR and multisensory stimulation engage individuals in virtual natural environment. | Qualitative | Older adults (N = 10); 5 females; age not given | Care home | Aromas in virtual green environment (woodland) | VR headset | Adoption and engagement (interviews and observations) | The successful co-creation of prototype experiences received positive feedback from participants and caregivers. VR and MSSE content provide a strong sense of place and facilitate recall. The combination of digital presence and physical, sensory objects enhances engagement for older adults in recreational experiences. However, VR is less effective for social interaction compared to MSSE. | Embodied performances and memories fostered connections within the immersive environment, sparked conversations about past experiences and travel desires, and provided vulnerable individuals with opportunities to transition from indoors to the outdoors. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hung, L.; Wong, J.; Wong, K.L.Y.; Son, R.C.E.; Van, M.; Mortenson, W.B.; Lim, A.; Boger, J.; Wallsworth, C.; Zhao, Y. The Use and Impact of Virtual Reality Programs Supported by Aromatherapy for Older Adults: A Scoping Review. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 188. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15010188

Hung L, Wong J, Wong KLY, Son RCE, Van M, Mortenson WB, Lim A, Boger J, Wallsworth C, Zhao Y. The Use and Impact of Virtual Reality Programs Supported by Aromatherapy for Older Adults: A Scoping Review. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(1):188. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15010188

Chicago/Turabian StyleHung, Lillian, Joey Wong, Karen Lok Yi Wong, Rynnie Cin Ee Son, Mary Van, W. Ben Mortenson, Angelica Lim, Jennifer Boger, Christine Wallsworth, and Yong Zhao. 2025. "The Use and Impact of Virtual Reality Programs Supported by Aromatherapy for Older Adults: A Scoping Review" Applied Sciences 15, no. 1: 188. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15010188

APA StyleHung, L., Wong, J., Wong, K. L. Y., Son, R. C. E., Van, M., Mortenson, W. B., Lim, A., Boger, J., Wallsworth, C., & Zhao, Y. (2025). The Use and Impact of Virtual Reality Programs Supported by Aromatherapy for Older Adults: A Scoping Review. Applied Sciences, 15(1), 188. https://doi.org/10.3390/app15010188