Smart Low-Cost Control System for Fish Farm Facilities

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Identification of Critical Factors for Control Systems for Aquaculture

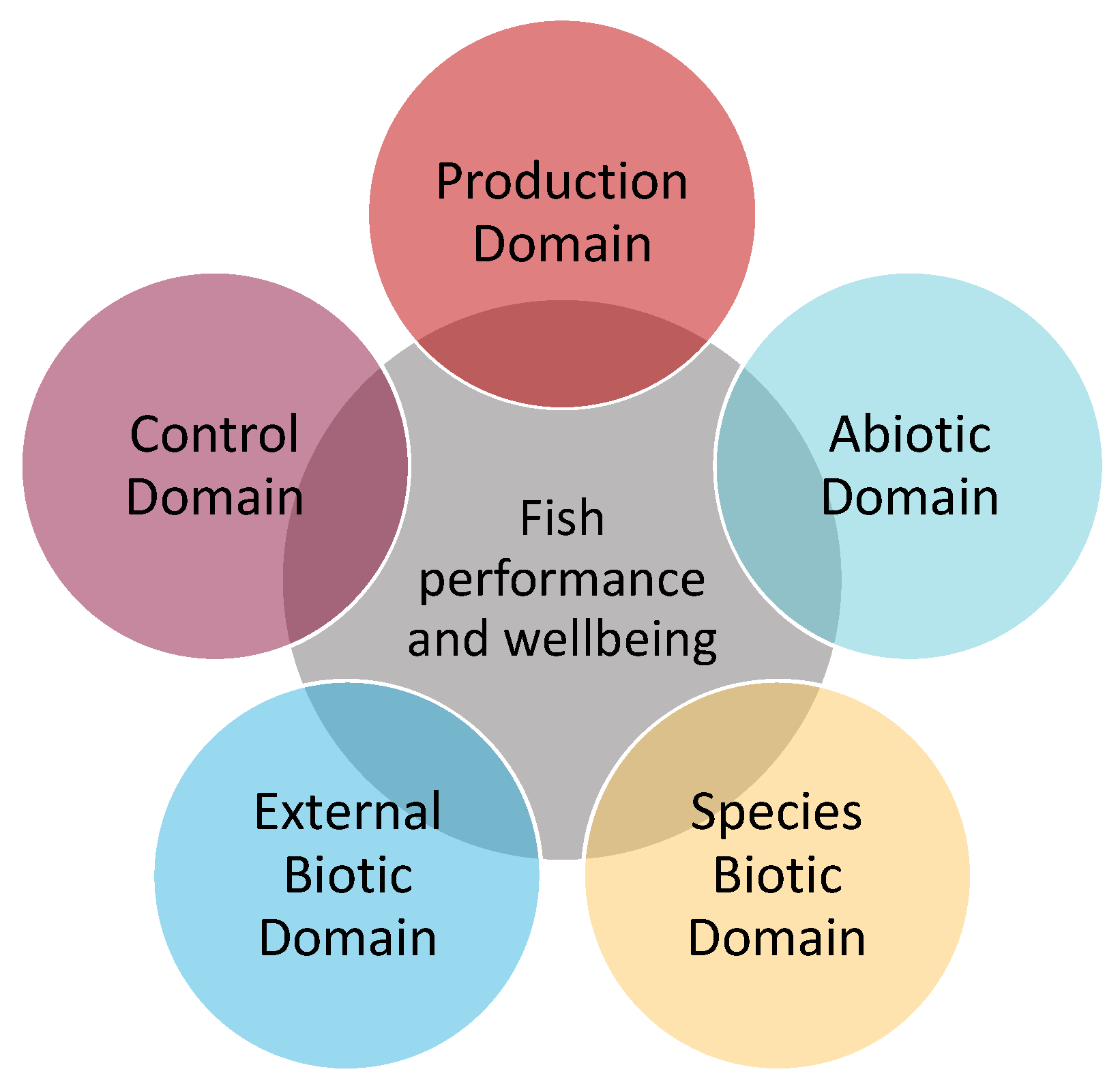

2.1. Factors Affecting Fish Wellbeing and Performance

- Production Domain: Factors derived from the way in which fish are produced in the facilities. Most of those factors are fixed and depend on the design and location of the production plant. Other factors are more flexible, such as feeding-related ones, and might be changed or improved.

- Biotic Domain: Factors dependent on the biotic part of the environment in which the facilities are located. All these factors are independent of the facilities and include water, atmosphere, and light factors. If facilities are located in open skies, barely any control or modification can be performed on these factors. Nonetheless, it is possible to modify these factors when facilities are indoors. More information is provided in the section titled Control Domain.

- Species Biotic Domain: Factors that depend on the grown species, including the growing stage and physiological and social factors. Even though most of them cannot be controlled or modified, some factors can be altered.

- External Biotic Domain: Factors depending on the presence and effects of other living beings found in the surroundings of the aquaculture facilities. It includes the effects of animals, plants, and bacteria, among others, on the fish. In general terms, the presence of the effect of external biotic factors can be controlled, minimized, or avoided.

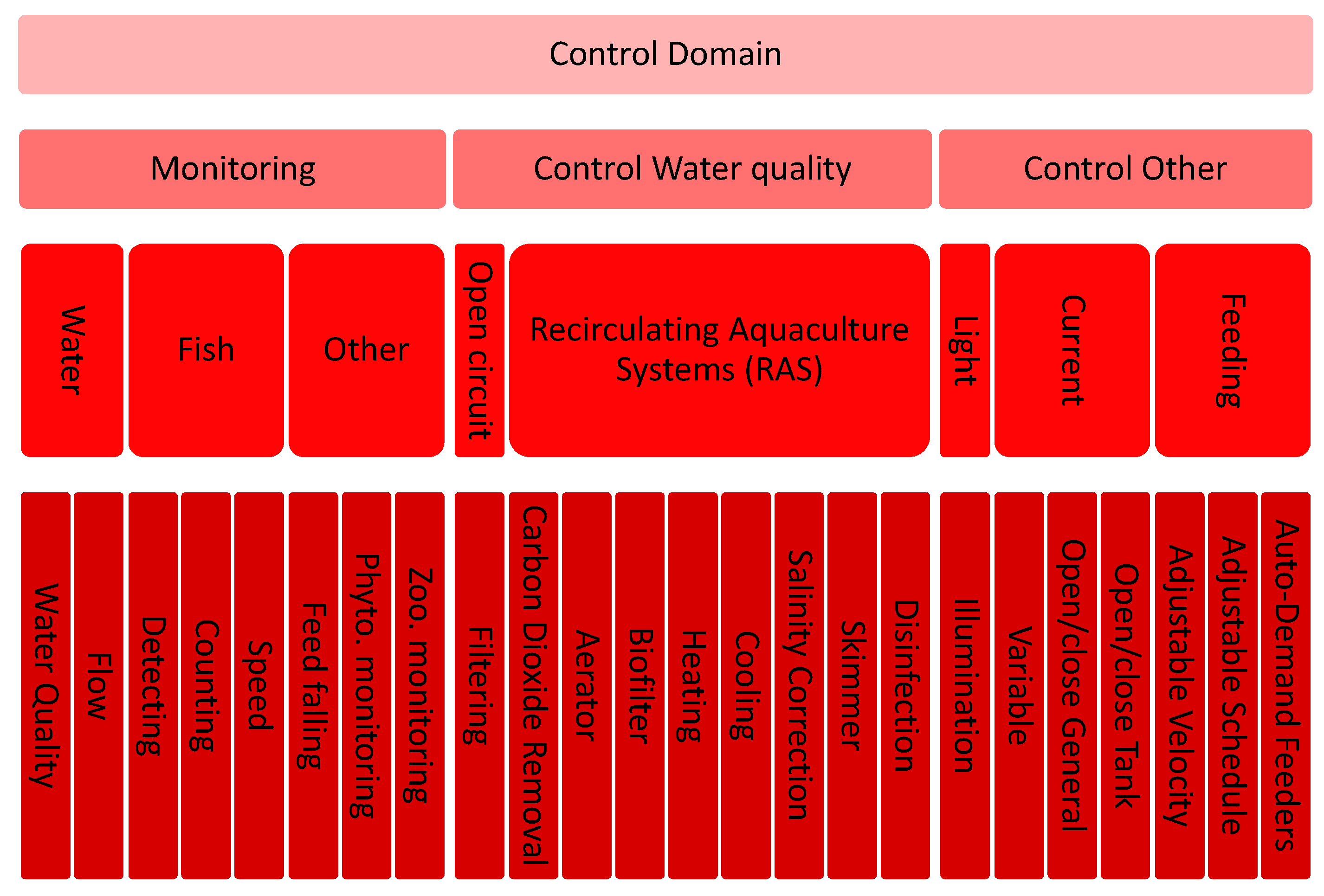

- Control Domain: Factors referring to the control actions that can be conducted on fish farms, including monitoring and modification of biotic, abiotic, and production domains. This is the core of aquaculture facilities’ smart, low-cost control systems. In the Domain, only the aspects related to the control of other domains are listed since the rest of the factors do not affect fish performance or well-being. These factors, such as monitoring, telecommunication, or computing technology, are defined in subsequent sections.

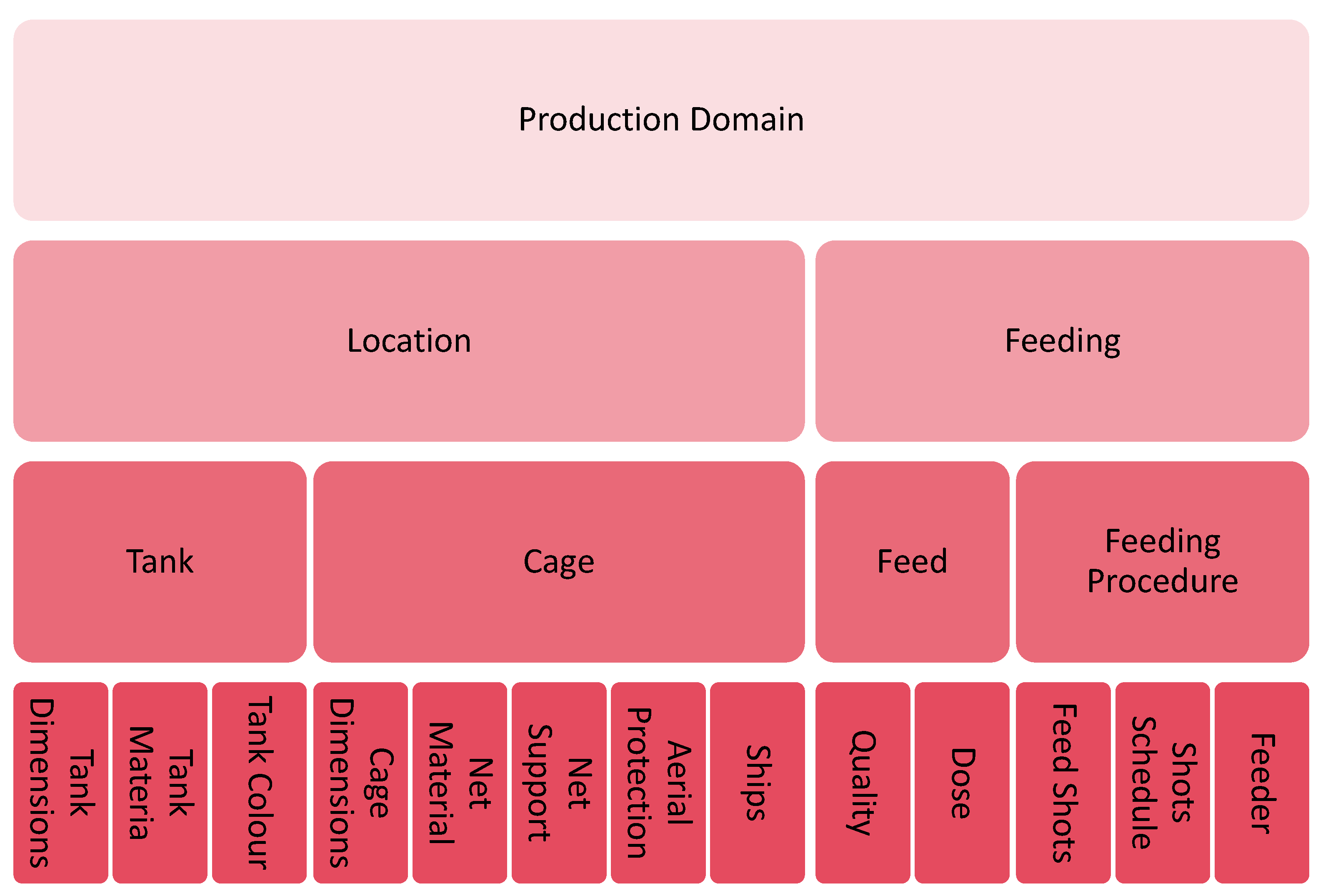

2.1.1. Factors of the Production Domain

2.1.2. Factors of the Species Abiotic Domain

2.1.3. Factors of the Species Biotic Domain

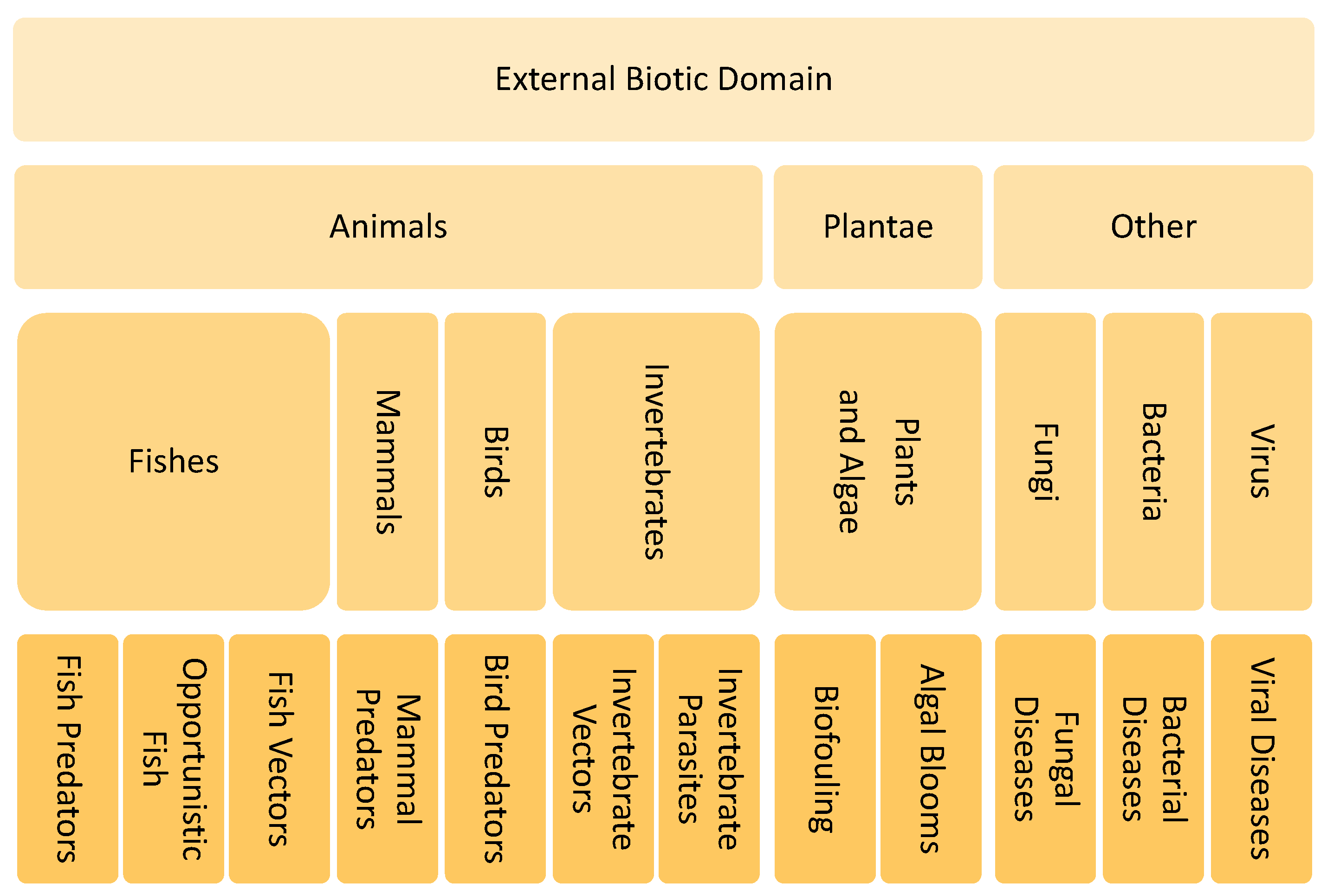

2.1.4. Factors of the External Biotic Domain

2.1.5. Factors of the Control Domain

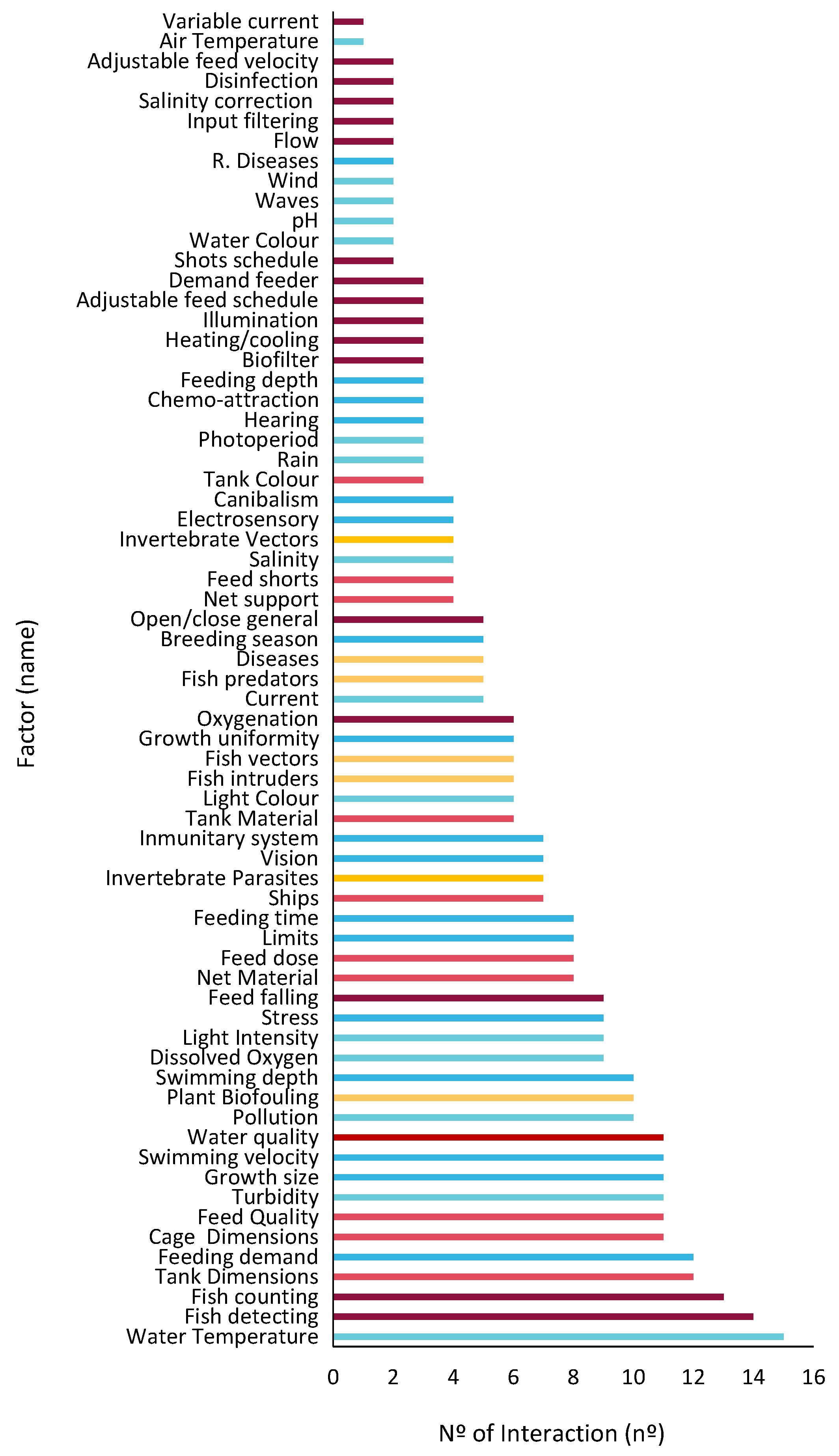

2.2. Interaction between Factors

3. Selected Factors for Smart Low-Cost Control Systems for Aquaculture

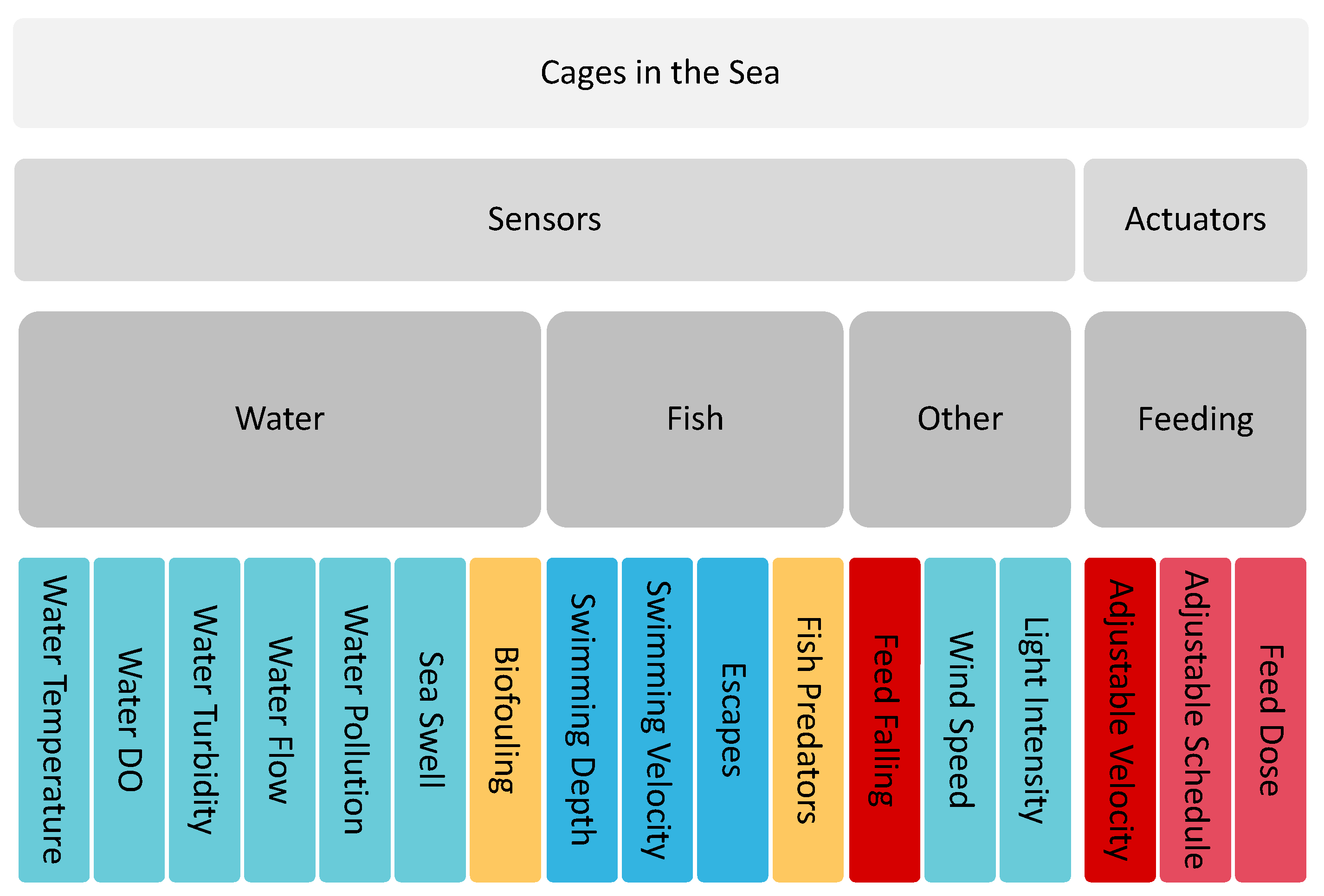

3.1. Selected Control Factors for Aquaculture Facilities with Cages in the Sea

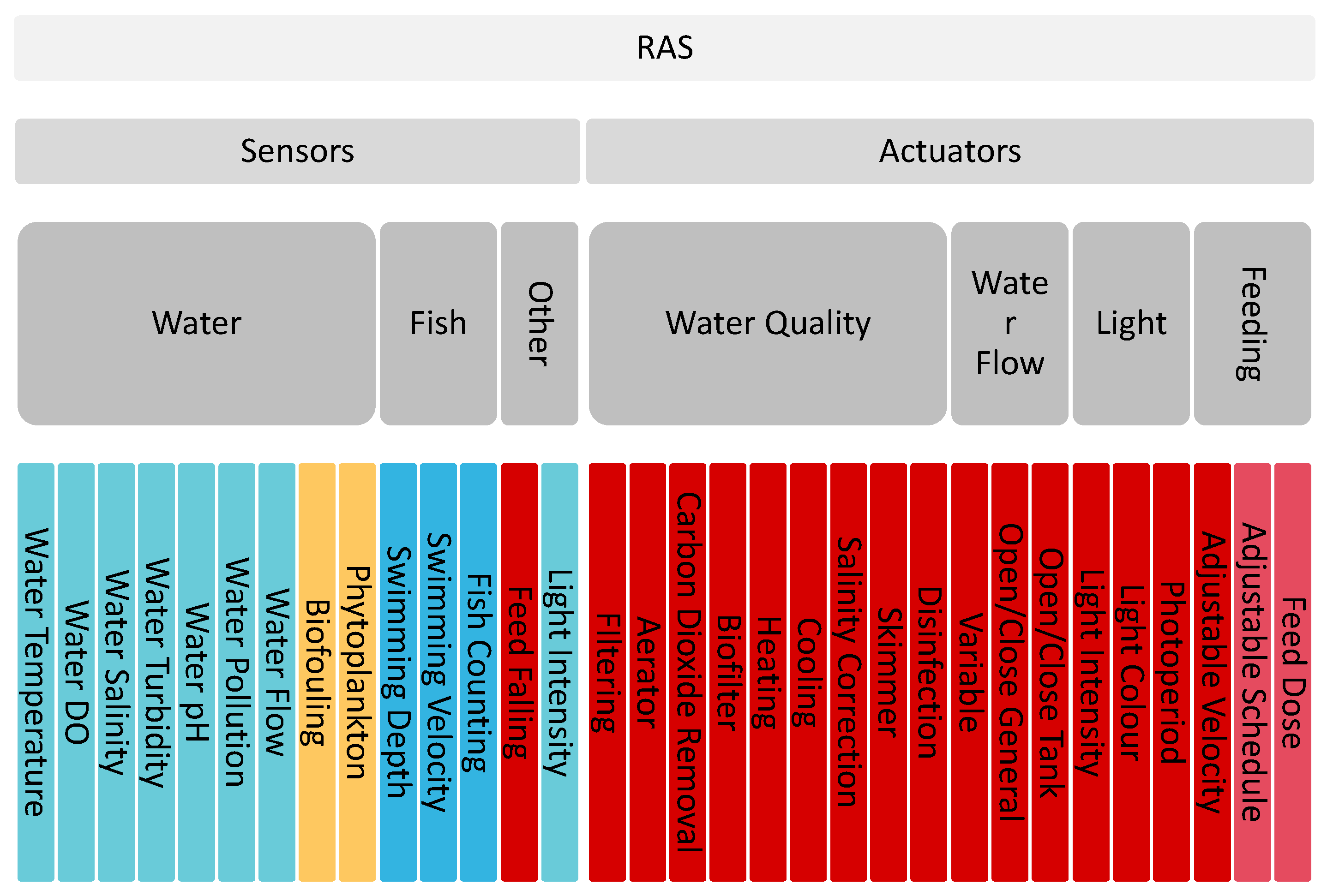

3.2. Selected Control Factors for RAS

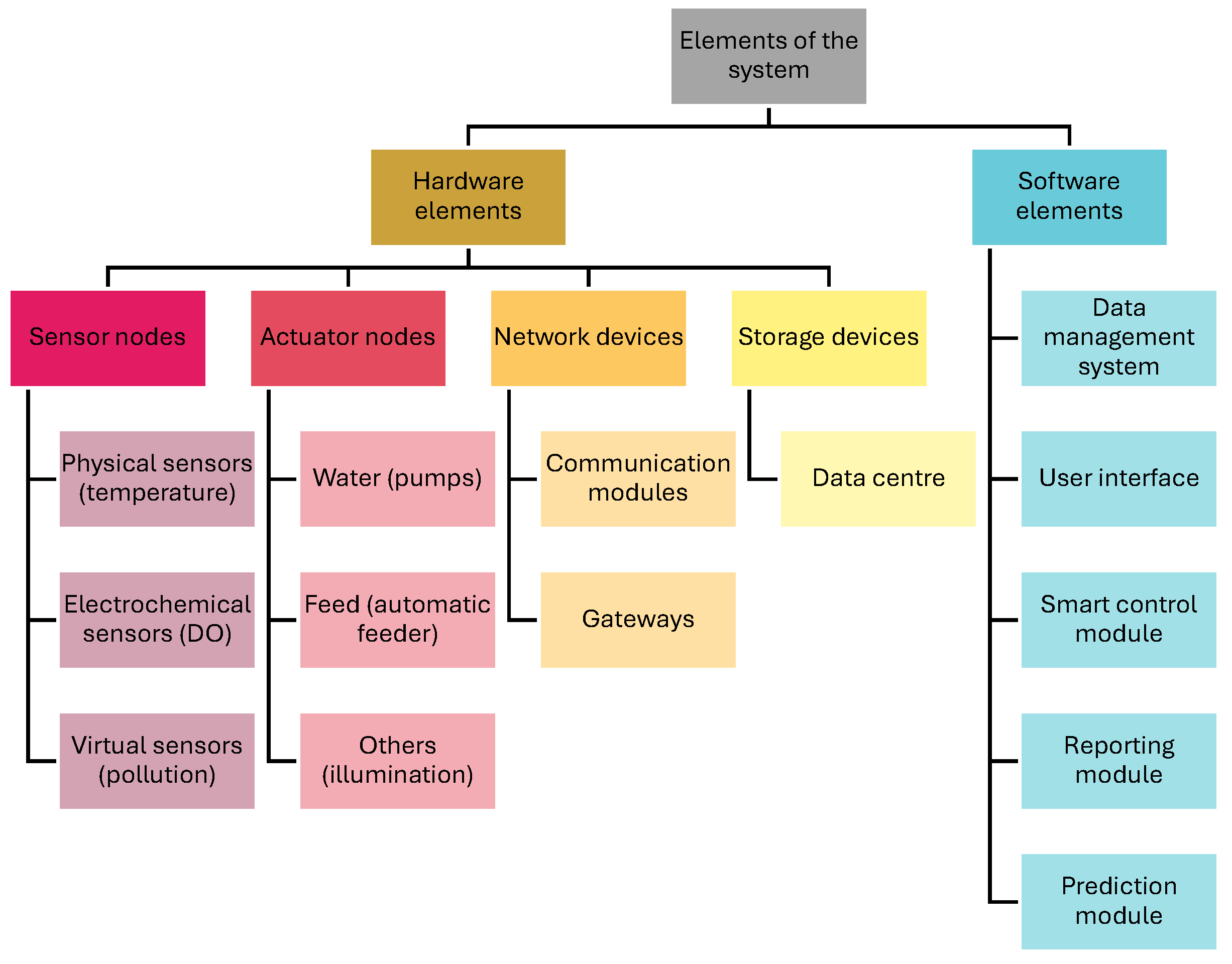

4. Proposal for Smart Low-Cost Control Systems for Aquaculture

4.1. Proposal for Smart Low-Cost Control Systems for Aquaculture Facilities with Cages in the Sea

4.1.1. General Aspects

4.1.2. Sensors and Actuators

4.1.3. Nodes

4.1.4. Communication Protocol and Communication Technologies

4.1.5. DB, AI, and Other Information Sources

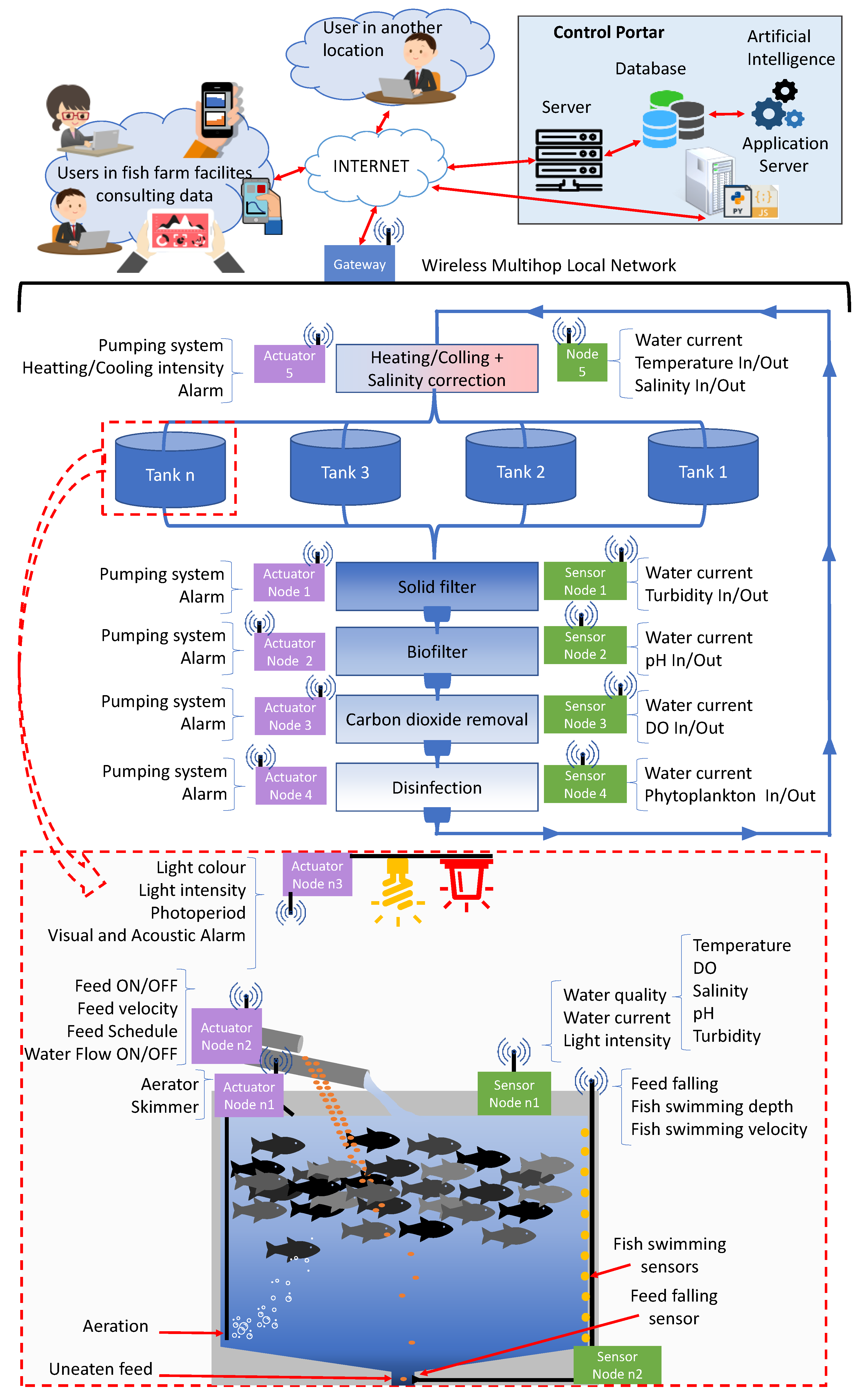

4.2. Adaptations for Smart Low-Cost Control Systems for Aquaculture Facilities with RAS

4.2.1. General Aspects

4.2.2. Sensors and Actuators

4.2.3. Communication Protocol and Communication Technologies

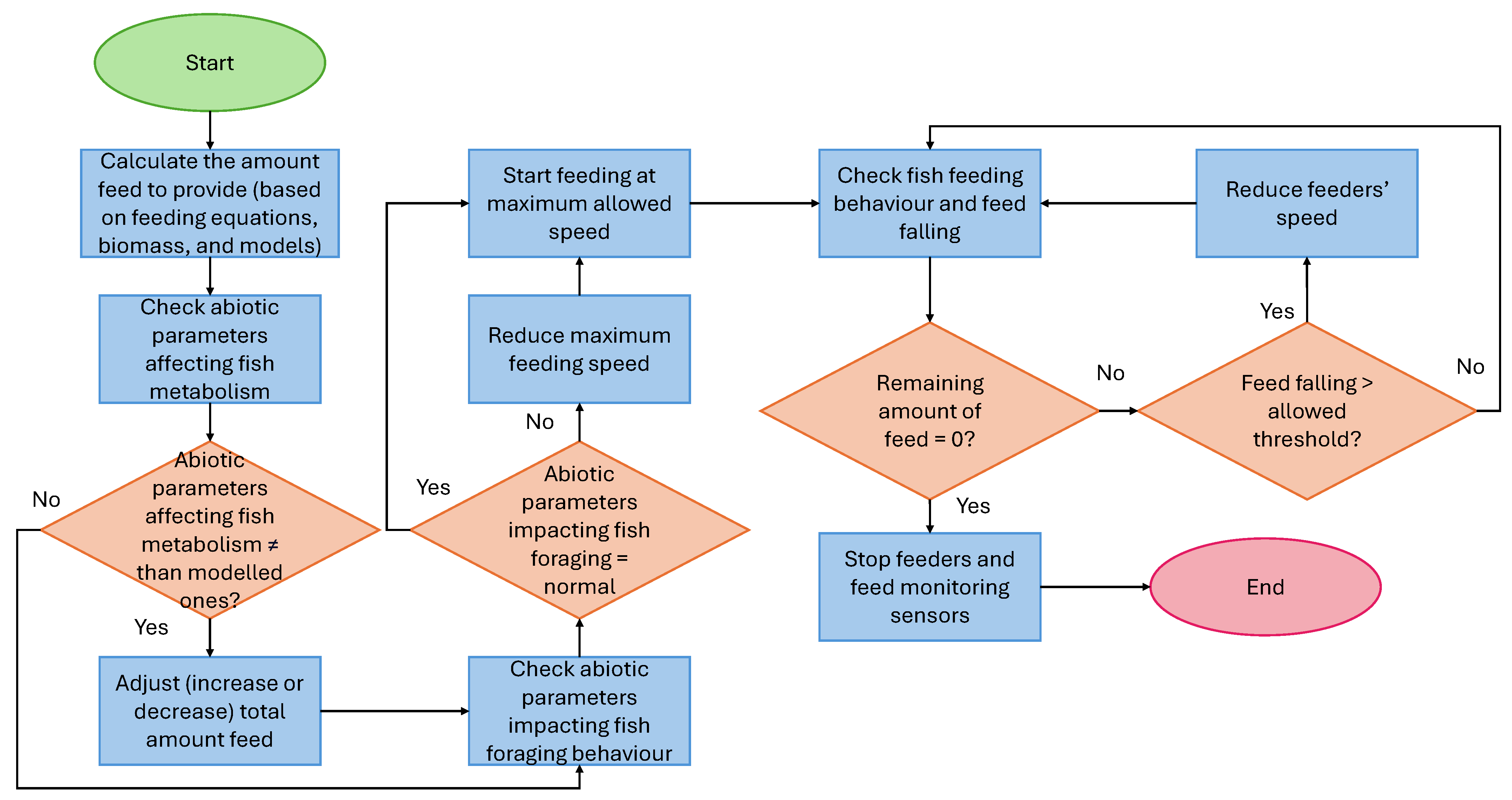

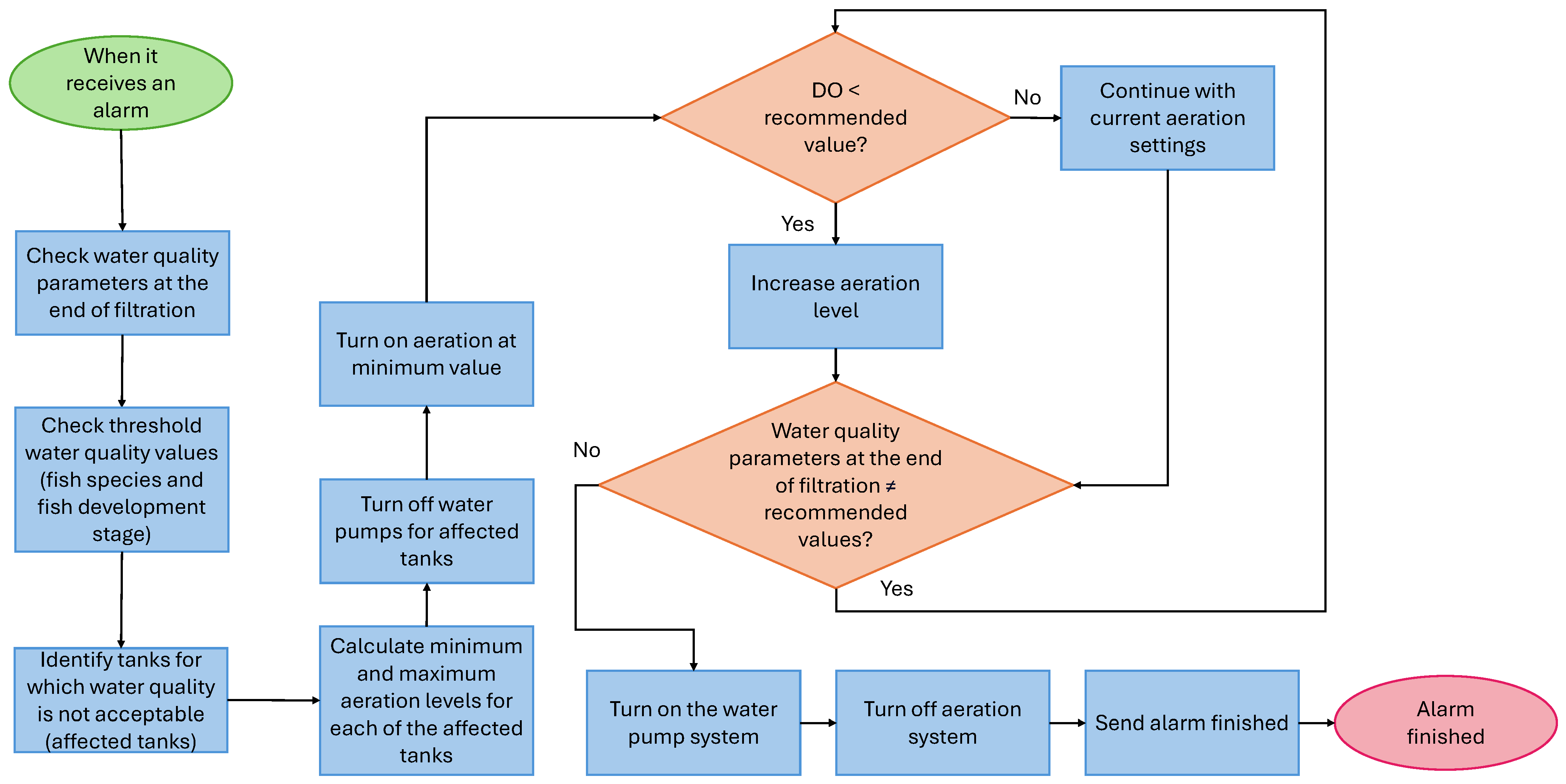

5. Smart Control Algorithm for Aquaculture

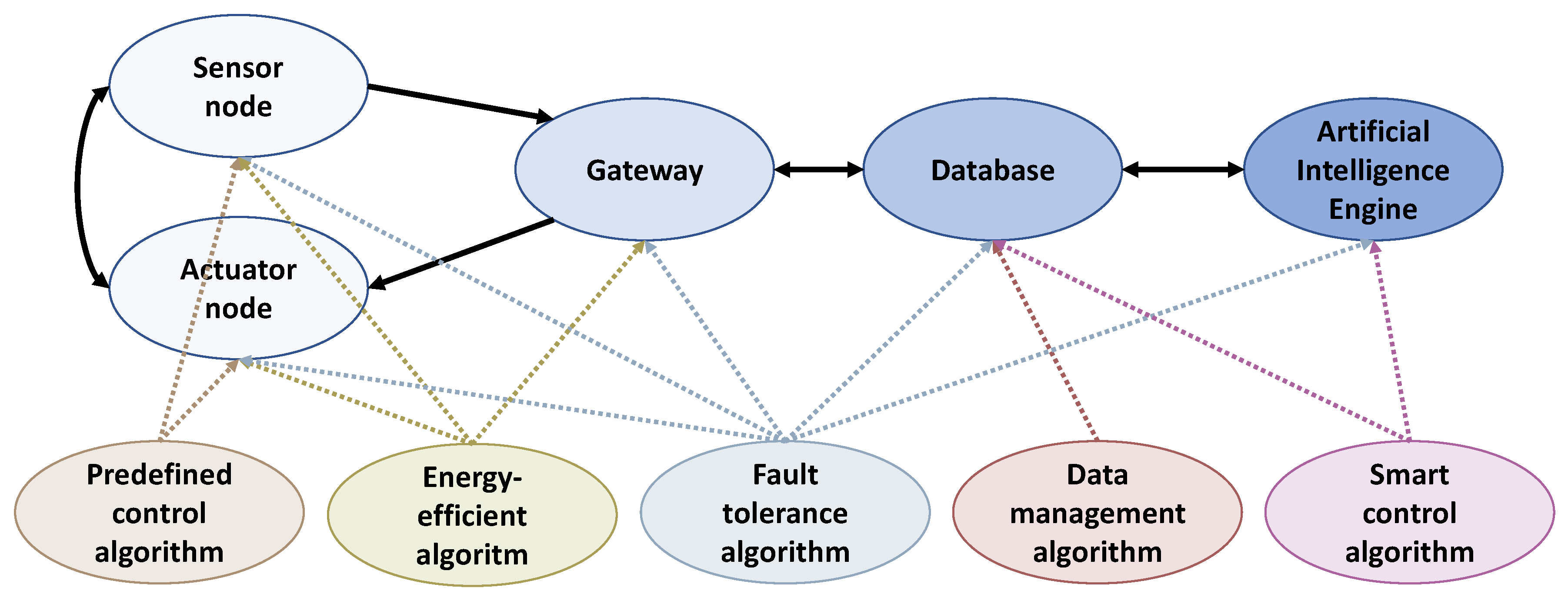

5.1. Included Algorithms in the Complete System

5.1.1. Predefined Control Algorithms

5.1.2. Energy Efficiency Algorithms

5.1.3. Fault-Tolerance Algorithms

- The algorithms relative to the failure in the network include using 3G/4G in the gateway of sea cages to ensure connectivity with the DB in case of failure of the LoRa network. If the gateway node does not receive any response from the DB when data are sent it supposes that the connectivity through LoRa is lost and the backup system based on 3G/4G starts to operate. Then, data are sent again with the new communication technology.

- If connectivity with DB is not restored after changing the wireless technology, the gateway assumes that the failure is in the DB itself. Therefore, a message is sent to all the sensor and actuator nodes in order to run the predefined control algorithm and save all the gathered information.

- Another way in which a failure in the connectivity with the DB can be prevented from affecting the regular operation of the actuators is when a message from the DB is expected and not received. In that case, the gateway body assumes that the connectivity is lost and alerts the local nodes to use the predefined control algorithm and save all the gathered information.

- If a node does not receive the response when data are forwarded to the gateway, it automatically assumes that the connectivity with the gateway is lost and attempts to connect with the backup gateway. The redundancy of critical elements such as the gateway buoy is another example of fault tolerance mechanisms.

5.1.4. Data Management and Smart Control Algorithm

- The sensor-gathered data contain information on the value of the different monitored factors such as water temperature, swimming depth, and feed falling, among others. This can be considered the primary source of information.

- The actuator data indicate the operation modes of different actuators in the fish farm facilities. They might indicate the periods in which actuators were deactivated or activated. Since some actuators might operate at different velocities or ratios, data include the value in those cases. The schedule of feeders or photoperiod of lights is another type of information. Finally, the activation of the alarm is important information for the system. This can be considered the second information source, which is particularly important in the case of RAS facilities.

- The remote sensing data offer reliable information on water quality in areas beyond the fish farm facilities. This information is only useful in marine cages and can be essential for pollution monitoring. It is the third information source.

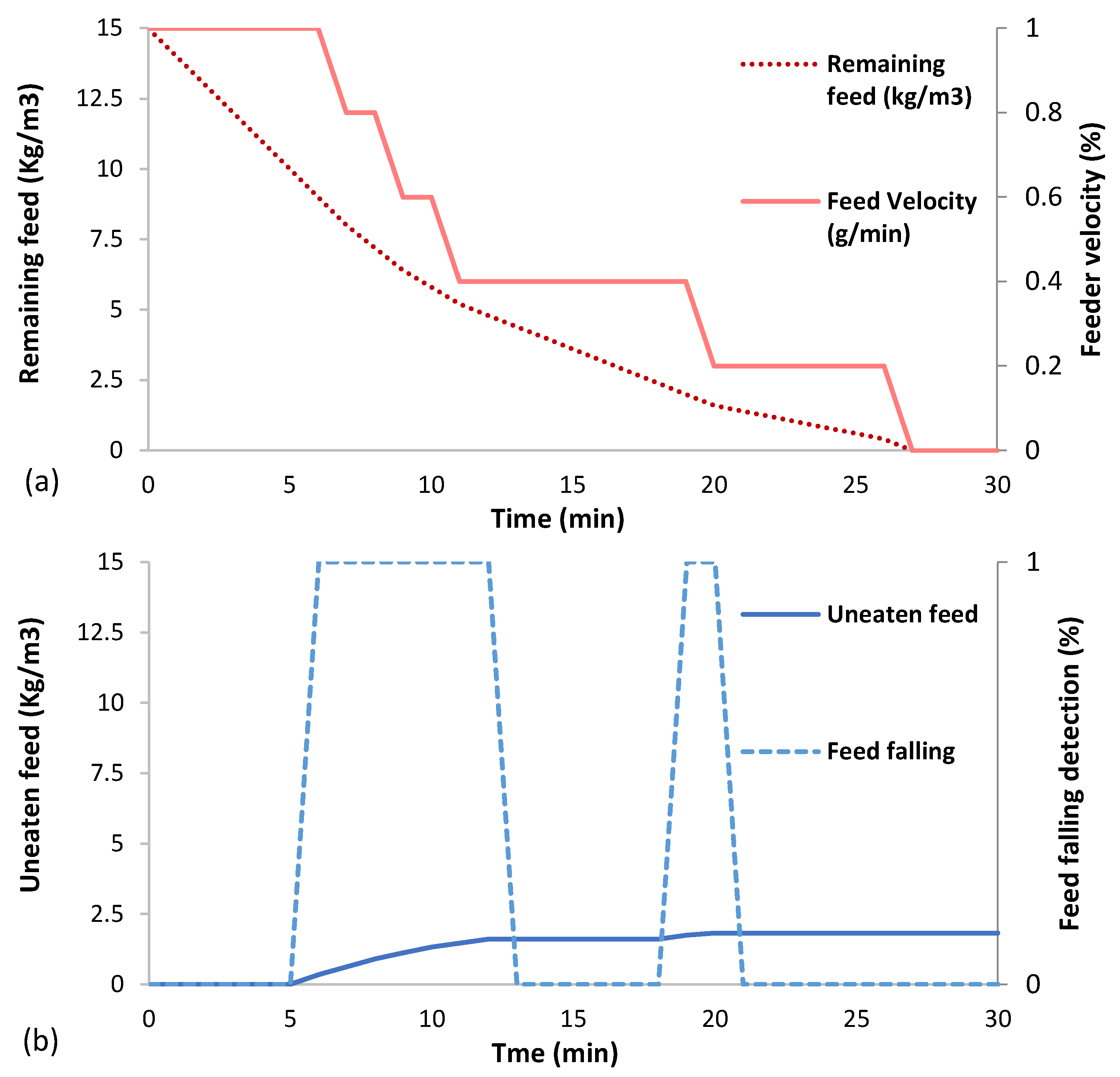

5.2. Example 1: Control Algorithm Operation in Sea Cages

- A reduction in the cost of feed, since 14.25 kg/m3 is used with the smart control algorithm against 15 kg /m3 with the predefined control algorithm. Considering that feed represents 70% of the costs of aquaculture production, saving 5% of the feed is an important economic saving.

- An improvement in feed utilization, considering that fish consumed the feed in a ratio of 13.82 kg /m3 when the fish farm received the information from the DB and the AI compared with the 13.18 kg /m3 when it did not receive it. This difference in feed consumption supposes better fish growth, which implies a better fish size at the harvest moment resulting in a higher market price of the produced fish.

- A reduction in environmental pollution due to uneaten food pellets, since 0.45 kg /m3 are deposited in the seabed when the system is fully operative. The value increases to 1.82 kg /m3 when predefined control algorithms regulate the feeding process. Uneaten feed is considered one of the most relevant environmental impacts of the aquaculture industry. A reduction in environmental impact supposes a greener and more sustainable production, better usage of resources, and cleaner oceans. In addition, the uneaten feed might unleash several pollution problems, which can affect fish, causing a decrease in fish welfare.

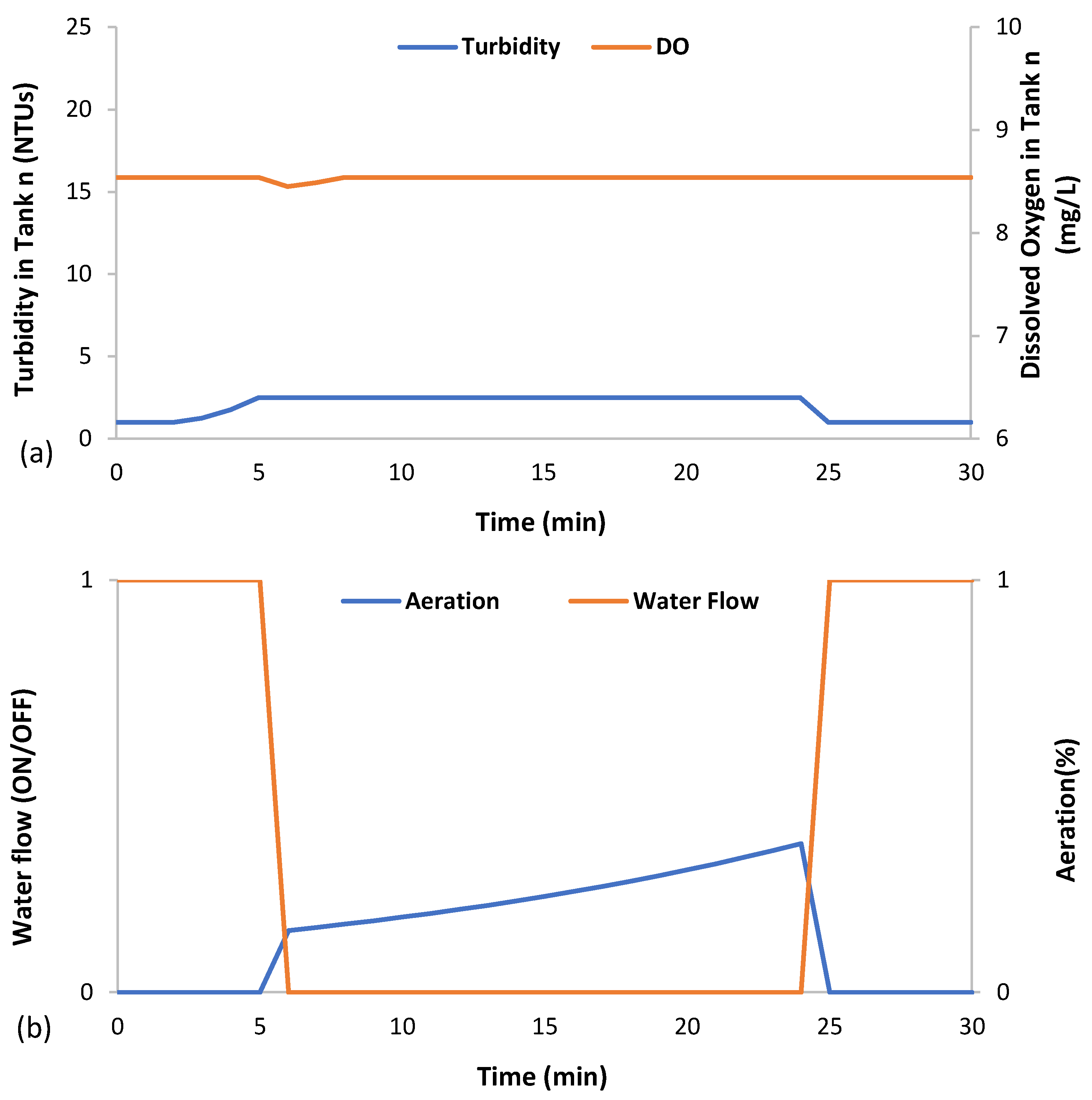

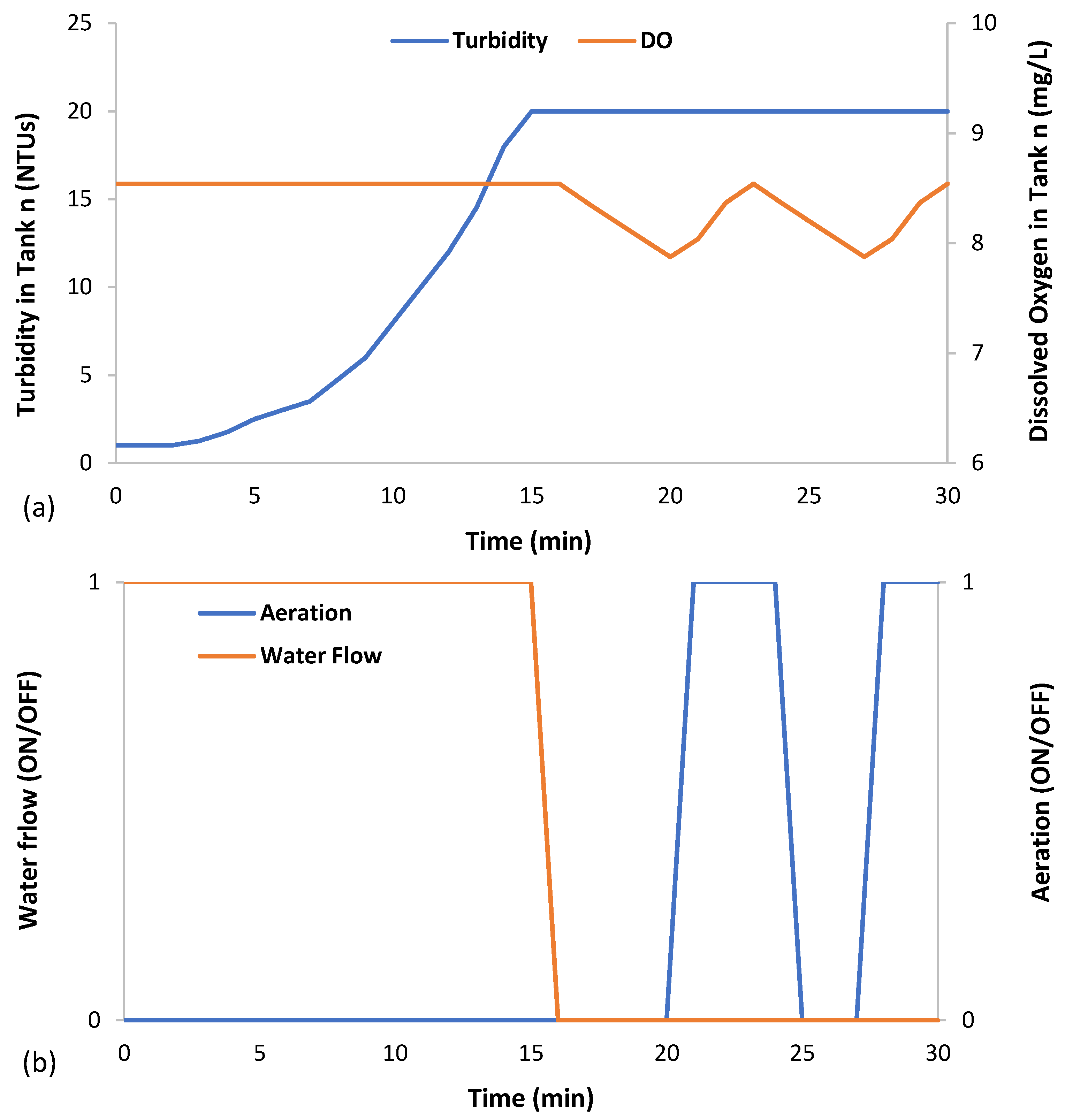

5.3. Example 2: Control Algorithm Operation in RAS

- An increase in fish welfare, since the water quality conditions in the tank in the first example are much better than in the second case. The reduced DO and high turbidity cause stress and alterations in the swimming patterns of fish. The turbidity in the first case represents 12.5% of the turbidity in the second case. The DO in the first case dropped by less than 2%. Meanwhile, the DO reduction is supposed to be 8% in the second case.

- An improvement in energy use, since the use of aeration, is more efficient in the first case. Even though aeration is activated for more time, 19 min in the first case compared with 7 min in the second case, the power consumption of the aeration system is much higher in the second case. The energy is reduced by 35% when the AI of the control system controls the situation compared with the predefined control algorithms.

- Finally, the fast action of workers due to the alarm helped to avoid further problems in the fish farm facilities in the first case. In the second case, no activation of the alarm is triggered by the AI. Thus, the turbidity reaches different parts of the water conditioning steps and the tanks. This supposes more maintenance tasks and can even cause the necessity of replacing elements of the facilities. Adequate maintenance based on the prediction of failures, thanks to the Smart Control System, reduces the time workers must dedicate to maintenance tasks. In this case, the use of the control system facilitates that the solid filters are fixed in the first minutes by simple action with no need to replace elements. This supposes economic savings for the company and better working conditions for operators.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture. 2022. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/cc0461en/cc0461en.pdf (accessed on 12 April 2022).

- Mohan, C.V.; Bhatta, R. Social and economic impacts of aquatic animal health problems on aquaculture in India. In Primary Aquatic Animal Health Care in Rural, Smallscale, Aquaculture Development; Arthur, J.R., Phillips, M.J., Subasinghe, R.P., Reantaso, M.B., MacRae, I.H., Eds.; FAO Fish Technical Paper Number 406; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2002; pp. 63–75. [Google Scholar]

- Waleed, A.; Medhat, H.; Esmail, M.; Osama, K.; Samy, R.; Ghanim, T.M. Automatic recognition of fish diseases in fish farms. In Proceedings of the 2019 14th International Conference on Computer Engineering and Systems (ICCES), Cairo, Egypt, 17 December 2019; pp. 201–206. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.V.; Loo, J.L.; Chuah, Y.D.; Tang, P.Y.; Tan, Y.C.; Goh, W.J. The use of vision in a sustainable aquaculture feeding system. Res. J. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2013, 6, 3658–3669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, P.; Guo, R.; Jin, S.; Liu, J.; Chen, L.; Ma, Z.; Liu, Y. Evaluation and analysis of water quality of marine aquaculture area. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolentino, L.K.; Chua, E.J.; Añover, J.R.; Cabrera, C.; Hizon, C.A.; Mallari, J.G.; Mamenta, J.; Quijano, J.F.; Virrey, G.; Madrigal, G.A.; et al. IoT-Based automated water monitoring and correcting modular device via LoRaWAN for aquaculture. Int. J. Comput. Digit. Syst. 2021, 10, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Amarnathvarma, A.; Thalluri, T.; Shin, K.J. Realization of water process control for smart fish farm. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Electronics, Information, and Communication (ICEIC), Barcelona, Spain, 19–22 January 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Itano, T.; Inagaki, T.; Nakamura, C.; Hashimoto, R.; Negoro, N.; Hyodo, J.; Honda, S. Water circulation induced by mechanical aerators in a rectangular vessel for shrimp aquaculture. Aquac. Eng. 2019, 85, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, R.J. Solar heating systems for recirculation aquaculture. Aquac. Eng. 2007, 36, 250–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, T.L.; Lund, J.W. Geothermal heating of greenhouses and aquaculture facilities. In Proceedings of the International Geothermal Conference, Reykjavík, Iceland, 14–17 September 2003; pp. 14–19. [Google Scholar]

- Frenzl, B.; Stien, L.H.; Cockerill, D.; Oppedal, F.; Richards, R.H.; Shinn, A.P.; Bron, J.E.; Migaud, H. Manipulation of farmed Atlantic salmon swimming behaviour through the adjustment of lighting and feeding regimes as a tool for salmon lice control. Aquaculture 2014, 424, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Xu, D.; Lin, K.; Sun, C.; Yang, Y. Intelligent feeding control methods in aquaculture with an emphasis on fish: A review. Rev. Aquac. 2018, 10, 975–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.H.; Wu, Y.C.; Li, H.; Chen, J.J. Net Cage with Nervous System for Offshore Aquaculture. Sens. Mater. 2022, 34, 1771–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, W.; Raymond, D.; Parish, D.; Ashton, I.G.C.; Miller, P.I.; Campos, C.J.A.; Shutler, J.D. Design and operation of a low-cost and compact autonomous buoy system for use in coastal aquaculture and water quality monitoring. Aquac. Eng. 2018, 80, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, D.; Hernandez, D.; Oliveira, F.; Luís, M.; Sargento, S. A platform of unmanned surface vehicle swarms for real time monitoring in aquaculture environments. Sensors 2019, 19, 4695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Hassan, S.G.; Wang, L.; Li, D. Fault diagnosis method for water quality monitoring and control equipment in aquaculture based on multiple SVM combined with DS evidence theory. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2017, 141, 96–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Qi, C.; Pan, H. Design of remote monitoring system for aquaculture cages based on 3G networks and ARM-Android embedded system. Procedia Eng. 2012, 29, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odey, A.; Daoliang, L. AquaMesh-design and implementation of smart wireless mesh sensor networks for aquaculture. Am. J. Netw. Commun. 2013, 2, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiaoman, L.; Xia, L. Design of a ZigBee wireless sensor network node for aquaculture monitoring. In Proceedings of the 2016 2nd IEEE International Conference on Computer and Communications (ICCC), Chengdu, China, 14–17 October 2016; pp. 2179–2182. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, L.; Zhang, J.; Mark, X.; Fu, Z.; Chen, W.; Zhang, X. Developing WSN-based traceability system for recirculation aquaculture. Math. Comput. Model. 2011, 53, 2162–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abril, J.S.; Sosa, G.S.; Sosa, J. Design of a Wireless Sensor Network for Oceanic Floating Cages in Aquaculture. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 62nd International Midwest Symposium on Circuits and Systems (MWSCAS), Dallas, TX, USA, 4–7 August 2019; pp. 977–980. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, T.; Zhang, T.; Li, B.; Xiao, J.; Li, J.; Liu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Y. An Innovative Cluster Routing Method for Performance Enhancement in Underwater Acoustic Sensor Networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 11, 25337–25357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shetty, S.; Pai, R.M.; Pai, M.M.M. Design and implementation of aquaculture resource planning using underwater sensor wireless network. Cogent Eng. 2018, 5, 1542576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, R.A.; Ramli, R.; Jamari, Z.; Ku-Mahamud, K.R. Evolutionary algorithm with roulette-tournament selection for solving aquaculture diet formulation. Math. Probl. Eng. 2016, 2016, 3672758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, H.; Duan, Q. Application of a hybrid improved sparrow search algorithm for the prediction and control of dissolved oxygen in the aquaculture industry. Appl. Intell. 2022, 53, 8482–8502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shreesha, S.; Manohara, P.M.M.; Ujjwal, V.; Radhika, M.P.; Girisha, S. Behavioural Pattern Analysis of Fishes for Smart Aquaculture: An Object Centric Approach. In Proceedings of the TENCON 2021-2021 IEEE Region 10 Conference (TENCON), Auckland, New Zealand, 7–10 December 2021; pp. 917–922. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, B.; Zhao, Y.; Bi, C.; Cheng, Y.; Ren, X.; Liu, Y. Investigation of flow field and pollutant particle distribution in the aquaculture tank for fish farming based on computational fluid dynamics. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 200, 107243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minich, J.J.; Poore, G.D.; Jantawongsri, K.; Johnston, C.; Bowie, K.; Bowman, J.; Knight, R.; Nowak, B.; Allen, E.E. Microbial ecology of Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) hatcheries: Impacts of the built environment on fish mucosal microbiota. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 86, e00411-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.S.K.; Salin, K.R.; Yakupitiyage, A.; Tsusaka, T.W.; Shrestha, S.; Siddique, M.A.M. Effect of stocking density and tank colour on nursery growth performance, cannibalism and survival of the Asian seabass Lates calcarifer (Bloch, 1790) in a recirculating aquaculture system. Aquac. Res. 2022, 53, 2472–2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldham, T.; Oppedal, F.; Dempster, T. Cage size affects dissolved oxygen distribution in salmon aquaculture. Aquac. Environ. Interact. 2018, 10, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgazzar, H.M.A. Deformation of Nylon Net and Copper Alloy Net in Fish Cage Models Subjected to Current Velocity. Ph.D. Thesis, Pukyong National University, Busan, Republic of Korea, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Morro, B.; Davidson, K.; Adams, T.P.; Falconer, L.; Holloway, M.; Dale, A.; Aleynik, D.; Thies, P.R.; Khalid, F.; Hardwick, J.; et al. Offshore aquaculture of finfish: Big expectations at sea. Rev. Aquac. 2022, 14, 791–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloecher, N.; Floerl, O. Towards cost-effective biofouling management in salmon aquaculture: A strategic outlook. Rev. Aquac. 2021, 13, 783–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiñones, R.A.; Fuentes, M.; Montes, R.M.; Soto, D.; León-Muñoz, J. Environmental issues in Chilean salmon farming: A review. Rev. Aquac. 2019, 11, 375–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filiciotto, F.; Giacalone, V.M.; Fazio, F.; Buffa, G.; Piccione, G.; Maccarrone, V.; Di Stefano, V.; Mazzola, S.; Buscaino, G. Effect of acoustic environment on gilthead sea bream (Sparus aurata): Sea and onshore aquaculture background noise. Aquaculture 2013, 414, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, T.A.; Anderson, T.W.; Širović, A. Intermittent noise induces physiological stress in a coastal marine fish. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0139157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawood, M.A.; Koshio, S.; Esteban, M.Á. Beneficial roles of feed additives as immunostimulants in aquaculture: A review. Rev. Aquac. 2018, 10, 950–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuebutornye, F.K.; Abarike, E.D.; Lu, Y. A review on the application of Bacillus as probiotics in aquaculture. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2019, 87, 820–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Q.; Zhen, Y.; Qin, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Lan, T.; Huang, L.; Shen, P. Effects of dietary Metschnikowia sp. GXUS03 on growth, immunity, gut microbiota and Streptococcus agalactiae resistance of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Aquac. Res. 2022, 53, 1918–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidy, A.B.; Eliyani, Y.; Ruchimat, T. Effects of feed reduction on growth performance, water quality, and hematology status of african catfish, Clarias gariepinus reared in biofloc pond system. Indones. Aquac. J. 2022, 17, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliabad, H.S.; Naji, A.; Mortezaei, S.R.S.; Sourinejad, I.; Akbarzadeh, A. Effects of restricted feeding levels and stocking densities on water quality, growth performance, body composition and mucosal innate immunity of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) fry in a biofloc system. Aquaculture 2022, 546, 737320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Li, Z.; Li, F.; Xiang, J. Effects of starvation on survival, growth and development of Exopalaemon carinicauda larvae. Aquac. Res. 2015, 46, 2289–2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Srivastava, S.C. Improved feeding strategy to optimize growth and biomass for up-scaling rainbow trout Oncorhynchus mykiss (Walbaum 1792) farming in Himalayan region. Aquaculture 2021, 542, 736851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flood, M.J.; John Purser, G.; Carter, C.G. The effects of changing feeding frequency simultaneously with seawater transfer in Atlantic salmon Salmo salar L. smolt. Aquac. Int. 2012, 20, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tacon, A.G.; Metian, M. Feed matters: Satisfying the feed demand of aquaculture. Rev. Fish. Sci. Aquac. 2015, 23, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besson, M.; Vandeputte, M.; Van Arendonk, J.A.M.; Aubin, J.; De Boer, I.J.M.; Quillet, E.; Komen, H. Influence of water temperature on the economic value of growth rate in fish farming: The case of sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) cage farming in the Mediterranean. Aquaculture 2016, 462, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaharisis, L.; Tsironi, T.; Dimitroglou, A.; Taoukis, P.; Pavlidis, M. Stress assessment, quality indicators and shelf life of three aquaculture important marine fish, in relation to harvest practices, water temperature and slaughter method. Aquac. Res. 2019, 50, 2608–2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandvik, A.D.; Dalvin, S.; Skern-Mauritzen, R.; Skogen, M.D. The effect of a warmer climate on the salmon lice infection pressure from Norwegian aquaculture. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2021, 78, 1849–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, C.E.; Torrans, E.L.; Tucker, C.S. Dissolved oxygen and aeration in ictalurid catfish aquaculture. J. World Aquac. Soc. 2018, 49, 7–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran-Ngoc, K.T.; Dinh, N.T.; Nguyen, T.H.; Roem, A.J.; Schrama, J.W.; Verreth, J.A. Interaction between dissolved oxygen concentration and diet composition on growth, digestibility and intestinal health of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Aquaculture 2016, 462, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solstorm, D.; Oldham, T.; Solstorm, F.; Klebert, P.; Stien, L.H.; Vågseth, T.; Oppedal, F. Dissolved oxygen variability in a commercial sea-cage exposes farmed Atlantic salmon to growth limiting conditions. Aquaculture 2018, 486, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hines, C.W.; Fang, Y.; Chan, V.K.; Stiller, K.T.; Brauner, C.J.; Richards, J.G. The effect of salinity and photoperiod on thermal tolerance of Atlantic and coho salmon reared from smolt to adult in recirculating aquaculture systems. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2019, 230, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ytrestøyl, T.; Takle, H.; Kolarevic, J.; Calabrese, S.; Timmerhaus, G.; Rosseland, B.O.; Teien, H.C.; Nilsen, T.O.; Handeland, S.O.; Stefansson, S.O.; et al. Performance and welfare of Atlantic salmon, Salmo salar L. post-smolts in recirculating aquaculture systems: Importance of salinity and water velocity. J. World Aquac. Soc. 2020, 51, 373–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira-Davison, E.; Callan, C.K. Effects of photoperiod, light intensity, turbidity and prey density on feed incidence and survival in first feeding yellow tang (Zebrasoma flavescens) (Bennett). Aquac. Res. 2018, 49, 890–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ende, S.S.; Larceva, E.; Bögner, M.; Lugert, V.; Slater, M.J.; Henjes, J. Low turbidity in recirculating aquaculture systems (RAS) reduces feeding behavior and increases stress-related physiological parameters in pikeperch (Sander lucioperca) during grow-out. Transl. Anim. Sci. 2021, 5, txab223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Guo, H.; Ma, Z.; Jiang, S.; Wu, K.; Li, Y.; Qin, J.G. Effects of prey color, wall color and water color on food ingestion of larval orange-spotted grouper Epinephelus coioides (Hamilton, 1822). Aquac. Int. 2015, 23, 1377–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota, V.C.; Hop, J.; Sampaio, L.A.; Heinsbroek, L.T.; Verdegem, M.C.; Eding, E.H.; Verreth, J.A. The effect of low pH on physiology, stress status and growth performance of turbot (Psetta maxima L.) cultured in recirculating aquaculture systems. Aquac. Res. 2018, 49, 3456–3467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summerfelt, S.T.; Zühlke, A.; Kolarevic, J.; Reiten BK, M.; Selset, R.; Gutierrez, X.; Terjesen, B.F. Effects of alkalinity on ammonia removal, carbon dioxide stripping, and system pH in semi-commercial scale water recirculating aquaculture systems operated with moving bed bioreactors. Aquac. Eng. 2015, 65, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Przybyla, C.; Triplet, S.; Liu, Y.; Blancheton, J.P. Long-term effects of moderate elevation of oxidation–reduction potential on European seabass (Dicentrarchus labrax) in recirculating aquaculture systems. Aquac. Eng. 2015, 64, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazi, I.; Tolga Gonul, L.; Kucuksezgin, F. Sources and Characterization of Polycyclic Aromatic and Aliphatic Hydrocarbons in Sediments Collected near Aquaculture Sites from Eastern Aegean Coast. Polycycl. Aromat. Compd. 2021, 41, 1042–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masci, M.; Orban, E.; Nevigato, T. Organochlorine pesticide residues: An extensive monitoring of Italian fishery and aquaculture. Chemosphere 2014, 94, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clementson, L.A.; Parslow, J.S.; Turnbull, A.R.; Bonham, P.I. Properties of light absorption in a highly coloured estuarine system in south-east Australia which is prone to blooms of the toxic dinoflagellate Gymnodinium catenatum. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2004, 60, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trottet, A.; George, C.; Drillet, G.; Lauro, F.M. Aquaculture in coastal urbanized areas: A comparative review of the challenges posed by Harmful Algal Blooms. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 52, 2888–2929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvathy, A.J.; Das, B.C.; Jifiriya, M.J.; Varghese, T.; Pillai, D.; Rejish Kumar, V.J. Ammonia induced toxico-physiological responses in fish and management interventions. Rev. Aquac. 2023, 15, 452–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumann, M.; Brinker, A. Understanding and managing suspended solids in intensive salmonid aquaculture: A review. Rev. Aquac. 2020, 12, 2109–2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristiansen, T.; Faltinsen, O.M. Experimental and numerical study of an aquaculture net cage with floater in waves and current. J. Fluids Struct. 2015, 54, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johannesen, Á.; Patursson, Ø.; Kristmundsson, J.; Dam, S.P.; Klebert, P. How caged salmon respond to waves depends on time of day and currents. PeerJ 2020, 8, e9313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, Y.; Zhao, S.X.; Zheng, X.Y.; Li, W. Effects of fish nets on the nonlinear dynamic performance of a floating offshore wind turbine integrated with a steel fish farming cage. Int. J. Struct. Stab. Dyn. 2020, 20, 2050042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, C.W.; Xu, T.J. Numerical study on the flow field around a fish farm in tidal current. Turk. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2018, 18, 705–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skøien, K.R.; Alver, M.O.; Lundregan, S.; Frank, K.; Alfredsen, J.A. Effects of wind on surface feed distribution in sea cage aquaculture: A simulation study. In Proceedings of the 2016 European Control Conference (ECC), Aalborg, Denmark, 29 June–1 July 2016; pp. 1291–1296. [Google Scholar]

- Lien, A.M.; Schellewald, C.; Stahl, A.; Frank, K.; Skøien, K.R.; Tjølsen, J.I. Determining spatial feed distribution in sea cage aquaculture using an aerial camera platform. Aquac. Eng. 2019, 87, 102018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faruque, M.H.; Kabir, M.A. Climate change effects on aquaculture: A case study from north western Bangladesh. Int. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci 2016, 4, 550–556. [Google Scholar]

- Hall Jr, R.O.; Yackulic, C.B.; Kennedy, T.A.; Yard, M.D.; Rosi-Marshall, E.J.; Voichick, N.; Behn, K.E. Turbidity, light, temperature, and hydropeaking control primary productivity in the c olorado river, g rand c anyon. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2015, 60, 512–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mapunda, J.; Mtolera, M.S.; Yahya, S.A.; Golan, M. Light colour affect the survival rate, growth performance, cortisol level, body composition, and digestive enzymes activities of different Snubnose pompano (Trachinotus blochii (Lacépède, 1801) larval stages. Aquac. Rep. 2021, 21, 100804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, W.; Han, D.; Zhu, X.; Yang, Y.; Jin, J.; Xie, S. Comparative study on dietary protein requirements for juvenile and pre-adult gibel carp (Carassius auratus gibelio var. CAS III). Aquac. Nutr. 2017, 23, 755–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, S.R.; Helfrich, L.A.; Kuhn, D.; Schwarz, M.H. Understanding Fish Nutrition, Feeds, and Feeding; College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, Virginia Tech: Blacksburg, VA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mramba, R.P.; Kahindi, E.J. Pond water quality and its relation to fish yield and disease occurrence in small-scale aquaculture in arid areas. Heliyon 2023, 9, e16753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koven, W.; Nixon, O.; Allon, G.; Gaon, A.; El Sadin, S.; Falcon, J.; Besseau, L.; Escande, M.; Agius, R.V.; Gordin, H.; et al. The effect of dietary DHA and taurine on rotifer capture success, growth, survival and vision in the larvae of Atlantic bluefin tuna (Thunnus thynnus). Aquaculture 2018, 482, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaon, A.; Tandler, A.; Nixon, O.; El Sadin, S.; Allon, G.; Koven, W. The combined DHA and taurine effect on vision, prey capture and growth in different age larvae of gilthead sea bream (Sparus aurata). Aquaculture 2021, 545, 737181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapozhnikova, Y.P.; Gasarov, P.V.; Makarov, M.M.; Kulikov, V.A.; Yakhnenko, V.M.; Glyzina, O.Y.; Tyagun, M.L.; Belkova, N.L.; Wanzenböck, J.; Sullip, M.K.; et al. The effects of sound pollution as a stress factor for the Baikal coregonid fish. Limnol. Freshw. Biol. 2018, 2, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahavadiya, D.; Sapra, D.; Rathod, V.; Sarman, V. Effect of biotic and abiotic factors in feeding activity in teleost fish: A review. J. Entomol. Zool. Stud. 2018, 6, 387–390. [Google Scholar]

- Kjetså, M.H.; Ødegård, J.; Meuwissen, T.H.E. Accuracy of genomic prediction of host resistance to salmon lice in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) using imputed high-density genotypes. Aquaculture 2020, 526, 735415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palaiokostas, C. Predicting for disease resistance in aquaculture species using machine learning models. Aquac. Rep. 2021, 20, 100660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, D.; Elayan, H.; Benelli, G.; Stefanini, C. Together we stand–analyzing schooling behavior in naive newborn guppies through biorobotic predators. J. Bionic Eng. 2020, 17, 174–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebauer, T.; Gebauer, R.; Císař, P.; Tran, H.Q.; Tomášek, O.; Podhorec, P.; Prokešová, M.; Rebl, A.; Stejskal, V. The Effect of Different Feeding Applications on the Swimming Behaviour of Siberian Sturgeon: A Method for Improving Restocking Programmes. Biology 2021, 10, 1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Wang, G.; Du, L.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, Z. Recent advances in intelligent recognition methods for fish stress behavior. Aquac. Eng. 2021, 96, 102222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y.J.; Ji, C.Y.; Zhang, B.; Gu, J.L. Representation of freshwater aquaculture fish behavior in low dissolved oxygen condition based on 3D computer vision. Mod. Phys. Lett. B 2018, 32, 1840090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Wang, Z.; Wu, S.; Miao, Z.; Du, L.; Duan, Y. Automatic recognition methods of fish feeding behavior in aquaculture: A review. Aquaculture 2020, 528, 735508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, B.W.; Shelton, A.O.; Anderson, J.H.; Ford, M.J.; Ward, E.J. Ecological implications of changing hatchery practices for Chinook salmon in the Salish Sea. Ecosphere 2019, 10, e02922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otieno, N.E.; Wasonga, D.V.; Imboko, D. Pond-adjacent grass height and pond proximity to water influence predation risk of pond fish by amphibians in small fish ponds of Kakamega County, western Kenya. Hydrobiologia 2021, 848, 1795–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paladini, G.; Longshaw, M.; Gustinelli, A.; Shinn, A.P. Parasitic diseases in aquaculture: Their biology, diagnosis and control. In Diagnosis and Control of Diseases of Fish and Shellfish; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 37–107. [Google Scholar]

- Bui, S.; Dempster, T.; Remen, M.; Oppedal, F. Effect of ectoparasite infestation density and life-history stages on the swimming performance of Atlantic salmon Salmo salar. Aquac. Environ. Interact. 2016, 8, 387–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannister, J.; Sievers, M.; Bush, F.; Bloecher, N. Biofouling in marine aquaculture: A review of recent research and developments. Biofouling 2019, 35, 631–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rolton, A.; Rhodes, L.; Hutson, K.S.; Biessy, L.; Bui, T.; MacKenzie, L.; Symonds, J.E.; Smith, K.F. Effects of Harmful Algal Blooms on Fish and Shellfish Species: A Case Study of New Zealand in a Changing Environment. Toxins 2022, 14, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, M.A.; Akter, S.; Khan, M.M.; Rahman, M.K. Relation between aquaculture with fish disease & health management: A review note. Bangladesh J. Fish. 2019, 31, 253–260. [Google Scholar]

- Huan, J.; Li, H.; Wu, F.; Cao, W. Design of water quality monitoring system for aquaculture ponds based on NB-IoT. Aquac. Eng. 2020, 90, 102088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prapti, D.R.; Mohamed Shariff, A.R.; Che Man, H.; Ramli, N.M.; Perumal, T.; Shariff, M. Internet of Things (IoT)-based aquaculture: An overview of IoT application on water quality monitoring. Rev. Aquac. 2022, 14, 979–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Liu, Y.; Yu, H.; Fang, X.; Song, L.; Li, D.; Chen, Y. Computer vision models in intelligent aquaculture with emphasis on fish detection and behavior analysis: A review. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2021, 28, 2785–2816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, B.; Zhou, X.; Li, D.; Duan, Q. FishTrack: Multi-object tracking method for fish using spatiotemporal information fusion. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 238, 122194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, J.; Xu, L. An automated fish counting algorithm in aquaculture based on image processing. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Forum on Mechanical, Control and Automation (IFMCA 2016), Shenzhen, China, 30–31 December 2016; pp. 358–366. [Google Scholar]

- Rasdi, N.W.; Arshad, A.; Ikhwanuddin, M.; Hagiwara, A.; Yusoff, F.M.; Azani, N. A review on the improvement of cladocera (Moina) nutrition as live food for aquaculture: Using valuable plankton fisheries resources. J. Environ. Biol. 2020, 41, 1239–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, R.; Wei, Y.; An, D.; Li, D.; Ta, X.; Wu, Y.; Ren, Q. A review on the research status and development trend of equipment in water treatment processes of recirculating aquaculture systems. Rev. Aquac. 2019, 11, 863–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, Z.; Li, K.; Li, T.; Yan, L.; Jiang, H.; Liu, L. Effects of light intensity and photoperiod on the growth performance of juvenile Murray cods (Maccullochella peelii) in recirculating aquaculture system (RAS). Aquac. Fish. 2023, 8, 274–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godoy-Olmos, S.; Jauralde, I.; Monge-Ortiz, R.; Milián-Sorribes, M.C.; Jover-Cerdá, M.; Tomás-Vidal, A.; Martínez-Llorens, S. Influence of diet and feeding strategy on the performance of nitrifying trickling filter, oxygen consumption and ammonia excretion of gilthead sea bream (Sparus aurata) raised in recirculating aquaculture systems. Aquac. Int. 2022, 30, 581–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.C.; Sheu, R.K.; Peng, W.Y.; Wu, J.H.; Tseng, C.H. Video-based parking occupancy detection for smart control system. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sifakis, N.; Kalaitzakis, K.; Tsoutsos, T. Integrating a novel smart control system for outdoor lighting infrastructures in ports. Energy Convers. Manag. 2021, 246, 114684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambali, M.F.H.; Patchmuthu, R.K.; Wan, A.T. IoT Based Smart Poultry Farm in Brunei. In Proceedings of the 2020 8th International Conference on Information and Communication Technology (ICoICT), Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 24–26 June 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Abdelhakim, A.I.; Helal, H.S. Scheduling a smart hydroponic system to raise water use efficiency. Misr J. Agric. Eng. 2022, 39, 493–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abinaya, M.; Survenya, S.; Shalini, R.; Sharmila, P.; Baskaran, J. Design and Implementation of Aquaculture Monitoring and Controlling System. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Computation of Power, Energy, Information and Communication (ICCPEIC), Chennai, India, 27–28 March 2019; pp. 232–235. [Google Scholar]

- Parra, L.; Sendra, S.; García, L.; Lloret, J. Design and deployment of low-cost sensors for monitoring the water quality and fish behavior in aquaculture tanks during the feeding process. Sensors 2018, 18, 750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, W.; Føre, M.; Urke, H.A.; Ulvund, J.B.; Bendiksen, E.; Alfredsen, J.A. New concept for measuring swimming speed of free-ranging fish using acoustic telemetry and Doppler analysis. Biosyst. Eng. 2022, 220, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubina, N.A.; Cheng, S.C.; Chang, C.C.; Cai, S.Y.; Lan, H.Y.; Lu, H.Y. Intelligent Underwater Stereo Camera Design for Fish Metric Estimation Using Reliable Object Matching. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 74605–74619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sendra, S.; Lloret, J.; Jimenez, J.M.; Parra, L. Underwater acoustic modems. IEEE Sens. J. 2015, 16, 4063–4071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Mejía, J.A.; Sendra, S.; Ivars-Palomares, A.; Lloret, J. Intelligent Heterogeneous Wireless Sensor Networks in Precision Agriculture. In Proceedings of the 19th International Symposium on Wireless Communication Systems, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 14–17 July 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Mohseni, F.; Saba, F.; Mirmazloumi, S.M.; Amani, M.; Mokhtarzade, M.; Jamali, S.; Mahdavi, S. Ocean water quality monitoring using remote sensing techniques: A review. Mar. Environ. Res. 2022, 180, 105701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, L.; Rocher, J.; Escrivá, J.; Lloret, J. Design and development of low cost smart turbidity sensor for water quality monitoring in fish farms. Aquac. Eng. 2018, 81, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, F.; Tzortziou, M.; Hu, C.; Mannino, A.; Fichot, C.G.; Del Vecchio, R.; Najjar, R.G.; Novak, M. Remote sensing retrievals of colored dissolved organic matter and dissolved organic carbon dynamics in North American estuaries and their margins. Remote Sens. Environ. 2018, 205, 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, L.; Ahmad, A.; Sendra, S.; Lloret, J.; Lorenz, P. Combination of Machine Learning and RGB Sensors to Quantify and Classify Water Turbidity. Chemosensors 2024, 12, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, M.; Sendra, S.; Lloret, G.; Lloret, J. Monitoring and control sensor system for fish feeding in marine fish farms. IET Commun. 2011, 5, 1682–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.-Y.; Cheng, C.-Y.; Cheng, S.-C.; Cheng, Y.-H.; Lo, W.-C.; Jiang, W.-L.; Nan, F.-H.; Chang, S.-H.; Ubina, N.A. A low-cost AI buoy system for monitoring water quality at offshore aquaculture cages. Sensors 2022, 22, 4078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Parra, L.; Sendra, S.; Garcia, L.; Lloret, J. Smart Low-Cost Control System for Fish Farm Facilities. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 6244. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14146244

Parra L, Sendra S, Garcia L, Lloret J. Smart Low-Cost Control System for Fish Farm Facilities. Applied Sciences. 2024; 14(14):6244. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14146244

Chicago/Turabian StyleParra, Lorena, Sandra Sendra, Laura Garcia, and Jaime Lloret. 2024. "Smart Low-Cost Control System for Fish Farm Facilities" Applied Sciences 14, no. 14: 6244. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14146244

APA StyleParra, L., Sendra, S., Garcia, L., & Lloret, J. (2024). Smart Low-Cost Control System for Fish Farm Facilities. Applied Sciences, 14(14), 6244. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14146244