The Influence of Monochromatic Illustrations on the Attention to Public Health Messages: An Eye-Tracking Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Problem Statement

Hypotheses

3. Materials and Methods

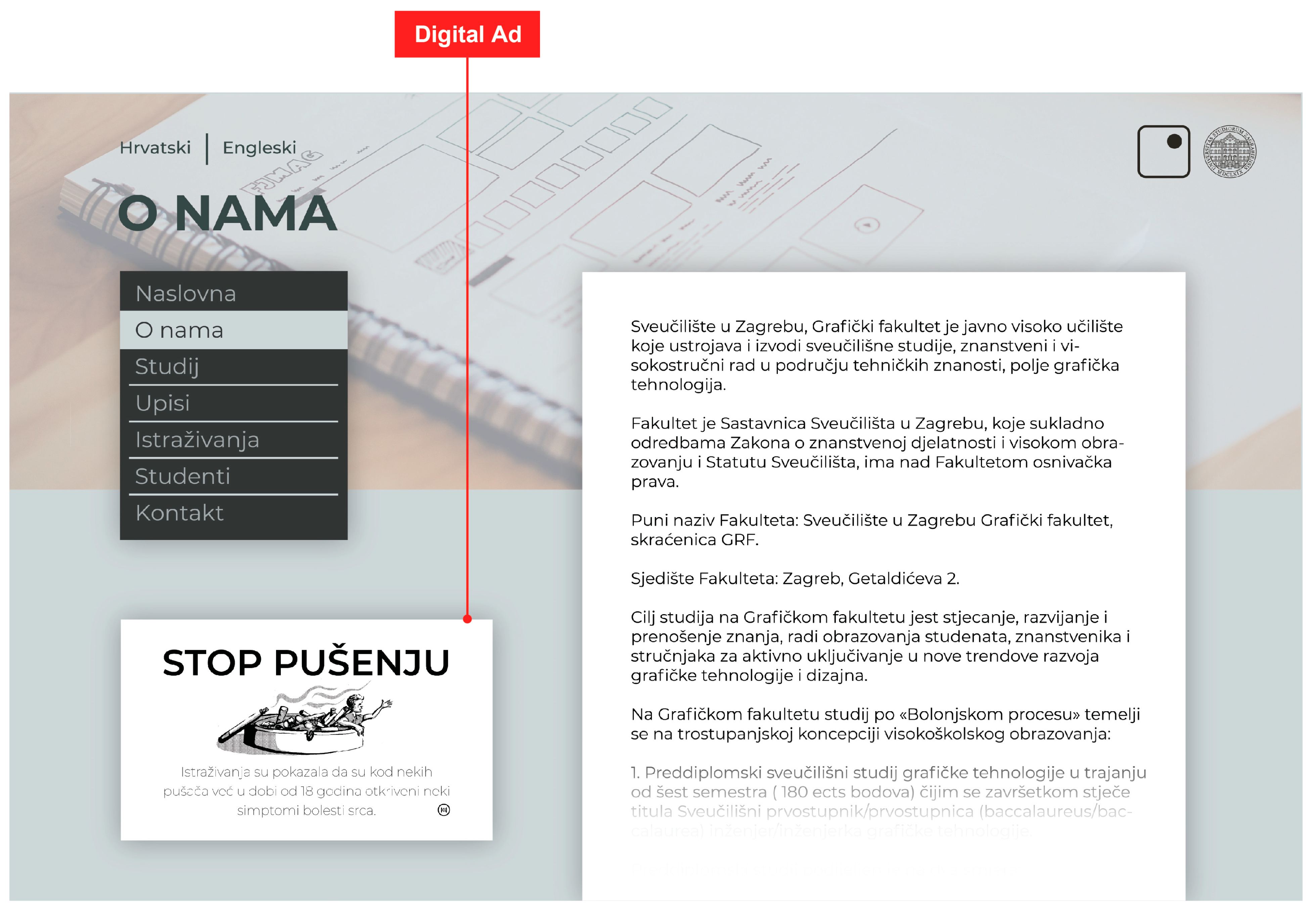

3.1. Stimuli Design

3.2. Participants

3.3. Equipment

3.4. Procedure

3.5. Dependent Measures

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zahmati, M.; Azimzadeh, S.M.; Sotoodeh, M.S.; Asgari, O. An eye-tracking study on how the popularity and gender of the endorsers affected the audience’s attention on the advertisement. Electron. Commer. Res. 2023, 23, 1665–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Keyzer, F.; Dens, N.; De Pelsmacker, P. The processing of native advertising compared to banner advertising: An eye-tracking experiment. Electron. Commer. Res. 2023, 23, 1921–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen-Sankey, J.; Weiger, C.; La Capria, K. Using Eye tracking to examine young adults’ visual attention to e-cigarette advertising features and associated positive e-cigarette perceptions. Ann. Behav. Med. 2024, 58, 445–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morin, C. The Neurophysiological Effect of Emotional Ads on the Brains of Late Adolescents and Young Adults. Ph.D. Thesis, Fielding Graduate University, Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; A/RES/70/1; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe. Alcohol as a Public Health Issue in Croatia: Situation Analysis and Challenges; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zoričić, Z.; Gašpar, V.; Ilić, S. Problems associated with drinking in young people in Croatia. Alcoholism 2008, 44, 29–35. [Google Scholar]

- Mišević, Ž.; Bogdan, A.; Mišević, M.; Ružić, T. Cultural patterns of drinking and alcoholism in north and south of Croatia. Interdiscip. Descr. Complex Syst. 2020, 18, 36–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leko Šimić, M.; Turjak, S. Croatian Students and Alcohol Consumption—Implications for Social Marketing. Ekon. Misao Praksa 2018, 27, 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Istenic, D.; Gavic, L.; Tadin, A. Prevalence of use and knowledge about tobacco products and their harmful effects among university students in southern Croatia. Healthcare 2023, 11, 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dragun, R.; Veček, N.N.; Marendić, M.; Pribisalić, A.; Đivić, G.; Cena, H.; Polašek, O.; Kolčić, I. Have lifestyle habits and psychological well-being changed among adolescents and medical students due to COVID-19 lockdown in Croatia? Nutrients 2020, 13, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Modica, E. Evaluation of Perception to Different Stimuli by Cognitive and Emotional Reaction for Neuromarketing Application. Ph.D. Thesis, Sapienza University of Rome, Rome, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wakefield, M.; Germain, D.; Durkin, S.; Hammond, D.; Goldberg, M.; Borland, R. Do larger pictorial health warnings diminish the need for plain packaging of cigarettes? Addiction 2012, 107, 1159–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, T. Legibility and visual effectiveness of some proposed and current health warnings on cigarette packages. In Report of Research Done under Contract to the Bureau of Tobacco Control of Health Canada; Government of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1999; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, S.; Kalaji, M.; Niederdeppe, J. Does visual attention to graphic warning labels on cigarette packs predict key outcomes among youth and low-income smokers? Tob. Regul. Sci. 2018, 4, 18–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Süssenbach, P.; Niemeier, S.; Glock, S. Effects of and attention to graphic warning labels on cigarette packages. Psychol. Health 2013, 28, 1192–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huebner, C. Digital Advertising and the Marketing Mix: A review of current literature and implications for Higher Education Marketers. J. Mark. Commun. High. Educ. 2019, 1, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj Rocque, S.; Singh Sisodia, N. Digital advertising and its impact on the economy in the future. Cent. Asian J. Math. Theory Comput. Sci. 2023, 4, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, J.M.; Ciorciari, J.; Gountas, J. Consumer neuroscience and digital/social media health/social cause advertisement effectiveness. Behav. Sci. 2019, 9, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birnbaum, M.L.; Garrett, C.; Baumel, A.; Scovel, M.; Rizvi, A.F.; Muscat, W.; Kane, J.M. Using digital media advertising in early psychosis intervention. Psychiatr. Serv. 2017, 68, 1144–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sørum, H. Visual attention and recall in website advertisements: An eye tracking study. In Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 607, pp. 205–216. ISBN 9783319604916. [Google Scholar]

- Tatler, B.W.; Kirtley, C.; Macdonald, R.G.; Mitchell, K.M.A.; Savage, S.W. The active eye: Perspectives on eye movement research. In Current Trends in Eye Tracking Research; Horsley, M., Eliot, M., Knight, B., Reilly, R., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 3–16. ISBN 9783319028682. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatraman, V.; Dimoka, A.; Vo, K.; Pavlou, P.A. Relative effectiveness of print and digital advertising: A memory perspective. J. Mark. Res. 2021, 58, 827–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, S.D.; Deitz, G.D.; Huhmann, B.A.; Jha, S.; Tatara, J.H. An eye-tracking study of attention to brand-identifying content and recall of taboo advertising. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 111, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Carmona, D.; Cruces-Montes, S.; Marín-Dueñas, P.P.; Serrano-Domínguez, C.; Paramio, A.; García, A.Z. Do you see it clearly? The effect of packaging and label format on google ads. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 1648–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segijn, C.M.; Voorveld, H.A.M.; Vakeel, K.A. The role of ad sequence and privacy concerns in personalized advertising: An eye-tracking study into synced advertising effects. J. Advert. 2021, 50, 320–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsharif, A.H.; Salleh, N.Z.M.; Al-Zahrani, S.A.; Khraiwish, A. Consumer behaviour to be considered in advertising: A systematic analysis and future agenda. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champlin, S.; Lazard, A.; Mackert, M.; Pasch, K.E. Perceptions of design quality: An eye tracking study of attention and appeal in health advertisements. J. Commun. Healthc. 2014, 7, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, J.; Ye, H.; Zhang, J.; Topoglu, Y.; Suri, R.; Ayaz, H. The face of bad advertising: Assessing the effects of human face images in advertisement design using eye-tracking. In Advances in Neuroergonomics and Cognitive Engineering; Ayaz, H., Asgher, U., Paletta, L., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 143–148. ISBN 978-3-030-80285-1. [Google Scholar]

- Peker, S.; Dalveren, G.G.M.; İnal, Y. The effects of the content elements of online banner ads on visual attention: Evidence from an-eye-tracking study. Future Internet 2021, 13, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieters, R.; Wedel, M. Attention Capture and Transfer in Advertising: Brand, Pictorial, and Text-Size Effects. J. Mark. 2004, 68, 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodrich, K. Anarchy of effects? Exploring attention to online advertising and multiple outcomes. Psychol. Mark. 2011, 28, 417–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Malley, D.; Latimer, A.; Berenbaum, E. Using eye tracking technology to determine the most effective viewing format and content for osteoporosis prevention print advertisements. J. Appl. Biobehav. Res. 2011, 16, 167–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strasser, A.A.; Tang, K.Z.; Romer, D.; Jepson, C.; Cappella, J.N. Graphic warning labels in cigarette advertisements. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2012, 43, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casado-Aranda, L.-A.; Sánchez-Fernández, J.; Ibáñez-Zapata, J.-Á. Evaluating communication effectiveness through eye tracking: Benefits, state of the art, and unresolved questions. Int. J. Bus. Commun. 2023, 60, 24–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, W.J. Attitudes and opinions. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1966, 17, 475–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, J.M.; Ciorciari, J.; Gountas, J. Consumer neuroscience for marketing researchers. J. Consum. Behav. 2018, 17, 239–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowska, A.; Olejnik-Krugly, A. Do background colors have an impact on preferences and catch the attention of users? Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resnick, M.; Albert, W. The impact of advertising location and user task on the emergence of banner ad blindness: An eye-tracking study. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2014, 30, 206–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gidlöf, K.; Holmberg, N.; Sandberg, H. The use of eye-tracking and retrospective interviews to study teenagers’ exposure to online advertising. Vis. Commun. 2012, 11, 329–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonetti, A.; Bigne, E. Does banner advertising still capture attention? An eye-tracking study. Spanish J. Mark. ESIC 2023, 28, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, B.T.; Luke, S.G. Best practices in eye tracking research. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2020, 155, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, G.; Corcoran, C.; Tatlow-Golden, M.; Boyland, E.; Rooney, B. See, like, share, remember: Adolescents’ responses to unhealthy-, healthy- and non-food advertising in social media. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, H.; Ju, H.W.; Johnson, K.K.P. Beyond visual clutter: The interplay among products, advertisements, and the overall webpage. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2021, 15, 804–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bočaj, N.; Ahtik, J. Effects of visual complexity of banner ads on website users’ perceptions. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 13317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.; Kwon, J.; Nam, S. Research on effective advertising types in virtual environment. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 7063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, M.L.; Tsai, M.J.; Yang, F.Y.; Hsu, C.Y.; Liu, T.C.; Lee, S.W.Y.; Lee, M.H.; Chiou, G.L.; Liang, J.C.; Tsai, C.C. A review of using eye-tracking technology in exploring learning from 2000 to 2012. Educ. Res. Rev. 2013, 10, 90–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrychowicz-Trojanowska, A. Basic terminology of eye-tracking research. Appl. Linguist. Pap. 2018, 25, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filiopoulou, D.; Rigou, M.; Faliagka, E. Display ads effectiveness: An eye tracking investigation. In Advances in E-Business Research Series; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2019; pp. 205–230. ISBN 9781522572626. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.W.; Ahn, J.H. Attention to banner ads and their effectiveness: An eye-tracking approach. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2012, 17, 119–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krugman, D.M.; Fox, R.J.; Fletcher, J.E.; Rojas, T.H. Do adolescents attend to warnings in cigarette advertising? An eye-tracking approach. J. Advert. Res. 1994, 34, 39–52. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y.; Qi, W.; Qin, J. Research on the memory of online advertising based on eye-tracking technology. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 15th International Conference on e-Business Engineering (ICEBE), Xi’an, China, 12–14 October 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA; pp. 324–328. [Google Scholar]

- Kovačević, D.; Brozović, M. Noticeability and recall of visual elements on packaging. In Proceedings of the 9th International Symposium on Graphic Engineering and Design, Novi Sad, Serbia, 8–10 November 2018; Kašiković, N., Ed.; Faculty of Technical Sciences: Novi Sad, Serbia, 2018; pp. 261–266. [Google Scholar]

- Guixeres, J.; Bigné, E.; Azofra, J.M.A.; Raya, M.A.; Granero, A.C.; Hurtado, F.F.; Ornedo, V.N. Consumer neuroscience-based metrics predict recall, liking and viewing rates in online advertising. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pieters, R.; Wedel, M.; Zhang, J. Optimal feature advertising design under competitive clutter. Manag. Sci. 2007, 53, 1815–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, S.; Huang, Z.; Scott, N.; Zhang, Z.; Shen, Z. Web advertisement effectiveness evaluation: Attention and memory. J. Vacat. Mark. 2019, 25, 130–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Carmona, D.; Muñoz-Leiva, F.; Liébana-Cabanillas, F.; Nieto-Ruiz, A.; Martínez-Fiestas, M.; Campoy, C. The effect of consumer concern for the environment, self-regulatory focus and message framing on green advertising effectiveness: An eye tracking study. Environ. Commun. 2021, 15, 813–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sałabun, W.; Karczmarczyk, A.; Mejsner, P. Experimental study of color contrast influence in Internet advertisements with eye tracker usage. In Neuroeconomic and Behavioral Aspects of Decision Making; Springer Proceedings in Business and Economics; Nermend, K., Łatuszynska, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 365–375. ISBN 9783319629377. [Google Scholar]

- Bol, N.; Van Weert, J.C.M.; Loos, E.F.; Romano Bergstrom, J.C.; Bolle, S.; Smets, E.M.A. How are online health messages processed? Using eye tracking to predict recall of information in younger and older adults. J. Health Commun. 2016, 21, 387–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.C.; Tsai, C.L.; Tang, T.W. Exploring advertising effectiveness of tourist hotels’ marketing images containing nature and performing arts: An eye-tracking analysis. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ad Topic | Statistic | TFF | FB | TFD | FC | TVD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol | Mean (SD) | 4.03 (0.45) | 9.71 (1.21) | 1.20 (0.15) | 5.43 (0.61) | 1.35 (0.17) |

| Smoking | Mean (SD) | 3.98 (0.44) | 7.68 (0.82) | 1.21 (0.16) | 5.28 (0.63) | 1.41 (0.18) |

| ANOVA results | F-value | 0.12 | 2.14 | 1.74 | 0.43 | 0.72 |

| p-value | 0.91 | 0.15 | 0.19 | 0.084 | 0.79 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Milošević, M.; Kovačević, D.; Brozović, M. The Influence of Monochromatic Illustrations on the Attention to Public Health Messages: An Eye-Tracking Study. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 6003. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14146003

Milošević M, Kovačević D, Brozović M. The Influence of Monochromatic Illustrations on the Attention to Public Health Messages: An Eye-Tracking Study. Applied Sciences. 2024; 14(14):6003. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14146003

Chicago/Turabian StyleMilošević, Marina, Dorotea Kovačević, and Maja Brozović. 2024. "The Influence of Monochromatic Illustrations on the Attention to Public Health Messages: An Eye-Tracking Study" Applied Sciences 14, no. 14: 6003. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14146003

APA StyleMilošević, M., Kovačević, D., & Brozović, M. (2024). The Influence of Monochromatic Illustrations on the Attention to Public Health Messages: An Eye-Tracking Study. Applied Sciences, 14(14), 6003. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14146003