Abstract

Background: Dentin adhesion is a basic aspect to consider in a root canal sealer. Calcium silicate-based cements are materials that have excellent biocompatibility and bioactivity. Bioactivity is closely related to dentin bond strength. One of the tests that is most used to evaluate the adhesive property of a sealing cement is the “push-out bond strength” test, which consists of applying tensile forces to the root to measure the resistance of the bonding of a material to root dentin. Aim: The aim of this systematic review is to perform a qualitative synthesis of available evidence on the adhesion of calcium silicate-based sealers to dentin. Methods: An advanced search of the literature was performed in five databases, limited to in vitro studies on human teeth published in the last 5 years. Results: 42 studies were eligible for the review, and data were collected according to the number of teeth studied, the canal preparation, the irrigant used, the mechanical test used, the root thirds and the type of sealer studied. A qualitative synthesis of the evidence is presented. Conclusions: TotalFill BC sealer and EndoSequence Root Repair Material appear as the calcium silicate-based materials with the highest bond strength to dentin. In addition, using 17% EDTA as a final irrigant increases the bond strength of calcium silicate-based sealers.

1. Introduction

In the root canal filling phase, the use of a sealing cement, which acts as an interface between the gutta-percha and the tooth structure, is essential [1]. Calcium silicate-based cements (CSCs) are materials that stimulate tissue regeneration and have a hydrophilic profile and excellent biocompatibility properties, due to their similarity to biological hydroxyapatite [2]. They have an intrinsic osteoinductive capacity, achieving a good hermetic seal due to the formation of a chemical bond with the tooth structure [2]. They have different levels of radiopacity and a great antibacterial capacity [2]. Among the most studied CSCs we can find Biodentine, EndoSequence BC Sealer, EndoSequence Root Repair Material, ProRoot MTA, and EndoSeal [3].

CSCs are also bioactive. Bioactivity is defined as a material’s ability to form hydroxyapatite on its surface and develop a mineral attachment or adhesion to the dentin substrate through the ionic interchange with surrounding tissue fluids [4]. Adhesion to dentin is a necessary characteristic for a root canal sealing cement. The aim is to achieve a three-dimensional union between gutta-percha, cement, and dentin, resulting in a hermetic seal of all the root canals. In this way, all anatomical irregularities of the root canal should be well filled to prevent any space or interface that could cause a bacterial or oral fluid filtration [1].

The challenge arises in achieving hermetic sealing when faced with undesirable conditions like perforations, resorptions, or open apices. Consequently, there is a demand for a restorative material capable of strong adherence to the dentin of the root canal. This material must also uphold the integrity of the material–dentin interface in static conditions and resist displacement. The effectiveness of this bond is influenced by the inherent properties of the materials involved and may also be influenced by the presence of the smear layer on the dentin surface. [5].

One of the tests most used to evaluate the adhesive property of a sealing cement is the so-called “push-out bond strength” test [6]. It consists of applying tensile forces to the root in its longitudinal axis to evaluate the share bond strength or dislocation resistance of a material [6]. The results depend on many variables such as the filling technique, tooth type, portion of the tooth studied, slice thickness, storage time, and loading speed [6]. The measurement is carried out in megapascals using a universal testing machine. Pressure is exerted with the plunger to separate the elements, and the measurements are recorded with computerized software [4].

Alternative methods for assessing the adhesive capability of a sealing cement include scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM). SEM enables the observation of high-magnification images (ranging from 50× to 10,000×). In this technique, an electron beam scans the surface of the sample, and the resulting signals are captured by a detector. Commonly used detectors in SEM include secondary electron detectors (ETD or SE1/SE2 in high vacuum or LFD in low vacuum) and backscattered electron detectors (BSED). While high vacuum provides superior magnification, it needs sample conductivity. As teeth and dental materials are non-conductive, preparing the sample involves applying a layer of gold (Au), which may potentially damage the sample [7]. CLSM operates with a laser beam serving as a light source and an electronic system for image processing. This technique utilizes extremely thin cross-sections (0.5–1.5 nm), resulting in high-resolution optical images. The elimination of light interference caused by different optical fields in the sample thickness contributes to the clarity of the images. The laser beam traverses a narrow space referred to as a pinhole, reflects off the sample, returns to the microscope for refocusing, and passes through the pinhole once more. The distinctiveness of the images is enhanced by the incorporation of fluorescent dyes into the root canal sealer [8].

Currently, there is a wide variety of CSCs, and there is no unified criteria regarding their bond strength. Accordingly, the aim of the present systematic review is to qualitatively assess the current state of the available in vitro evidence on CSC adhesion to dentin. The study’s specific objectives include identifying the CSCs which exhibit the highest bond strength to root dentin and identifying the influence of the irrigation protocol in CSC adhesion to dentin.

2. Materials and Methods

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA 2020 (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines [9]. The research question, based on the PICO model, was as follows: “What is the current state of the available in vitro evidence on the bond strength of CSCs to the dentin walls?”

2.1. Search Strategy

The electronic databases Medline (via PubMed), Web of Science, Scopus, Embase and Science Direct were searched. The search was conducted in September 2022 and updated in April 2023. The search strategy and data extraction were carried out by an individual examiner.

In each database, the following terms were used: “push out bond strength”, “calcium silicate-based cement”, “calcium silicate-based sealer”, “bioceramics”, “dentin adhesion”. The Boolean operators “AND” and “OR” were used to combine the terms and create the search strategy. The search was limited to articles published from 2018 to the present.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

In vitro studies that evaluated the bond strength of CSCs to dentin were eligible. Eligibility criteria were based on the PICO (population, intervention, comparison, results) strategy: P: extracted mature human teeth; I: calcium silicate sealers; C: control group; and O: bond strength values. Reviews, opinion articles, animal studies, studies that included artificial teeth, and studies that did not provide the mean and standard deviation of bond strength values were excluded.

2.3. Data Extraction

The following data were extracted: publication data (author and year of publication), the type of teeth and sample size, the system used for root canal preparation, the irrigant used, the mechanical test used to study adhesion, the studied cements, and the bond strength results in megapascals.

2.4. Quality Assessment (Risk of Bias)

To evaluate the methodological quality of the included studies, the “modified CONSORT checklist for in vitro studies on dental materials” proposed by Faggion et al. (2012) was used [10]. The studies were evaluated individually to determine compliance/non-compliance with each of the 14 parameters considered in the quality assessment tool. Subsequently, the percentage of completed items was calculated (number of completed items/total number of items × 100).

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection and Flowchart

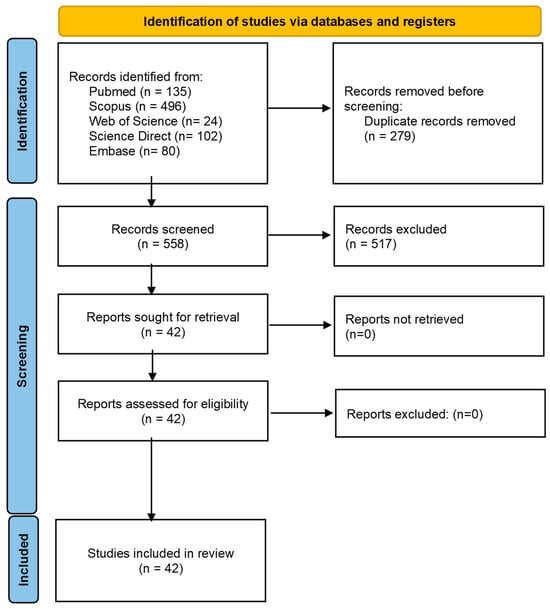

Figure 1 shows the flowchart of the search strategy. Initially, the search resulted in 837 published studies, including 135 identified in Pubmed, 496 in Scopus, 24 in Web of Science, 102 in Science Direct and 80 in Embase. A total of 279 duplicate studies were excluded. An analysis of titles and abstracts resulted in the exclusion of 517 articles, leaving 42 for full-text reading. Lack of compliance with the inclusion criteria was the main reason for the exclusion of articles. After a comprehensive reading of the remaining 42 articles, all of them were eligible for the review.

Figure 1.

Flowchart representing the study selection process. Based on the PRISMA 2020 flow diagram [9].

3.2. Study Methodology and Results

The data collected from the 42 included studies are summarized in Table 1. The number of teeth used for the studies ranged between 10 and 180. All included studies used the push-out bond strength (POBS) test and measured the bond strength in megapascals (MPa). The thickness of the slices varied between 1 mm and 3 mm and the ejection speed between 0.5 mm/min and 1 mm/min. A total of 26 articles compared the bond strength of CSCs with resin cements, while 16 articles compared the bond strength between different CSCs. The bond strength data are represented in Supplementary Table S1.

Table 1.

Methodological variables extracted from the included studies.

3.2.1. Sample

All selected articles used human teeth. In total, 8 of them used anterior teeth and 21 used posterior teeth. Furthermore, 13 articles did not mention the type of teeth evaluated.

3.2.2. Preparation of Root Canals

For root canal preparation, 19 articles used the ProTaper system (DENTSPLY Maillefer, Ballaigues, Switzerland), 7 articles used the Reciproc system (VDW GmbH, Munich, Germany) and 5 used Gates/Peeso burs. A small minority used manual instrumentation, the K3XF rotary system, Neo Endo Flex Rotary File System (Orikam Healthcare India Pvt Ltd., Gurugram, Haryana, India), cylindrical carbide or spherical diamond burs, the Wave One rotary system and Drills Largo.

3.2.3. Irrigant during Preparation

In total, 31 of the 42 selected articles used sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl) as an irrigant during root canal preparation in different quantities and at different percentages. One article used 17% EDTA, another article used only distilled water, and the rest of the articles used a combination of NaOCl, EDTA, distilled water, and/or saline.

3.2.4. Final Irrigant

As a final irrigant, ten articles used a combination of 17% EDTA and NaOCl only or also in combination with distilled water, saline solution or sterile water. Eleven articles used EDTA alone or in combination with distilled water or saline solution. Three articles used NaOCl in combination with CHX, distilled water and/or saline solution. Four articles used only distilled water, saline solution, or chlorhexidine as a final irrigant. Five articles did not mention what type of final irrigant they used.

On the other hand, nine articles used a different final irrigant depending on the intervention group that was studied. Within these groups are the following irrigants: saline solution, CHX, NaOCl, MA (maleic acid), EDTA, HEDP (etidronic acid), laser, sonic (S) and ultrasonic (US) activation, Qmix 2 in 1, blue methylene (+diode laser), curcumin (+fiber optics), toluidine blue (+diode laser), DMSO (dimethyl sulfoxide) and phosphoric acid.

3.2.5. Drying Protocol

Thirty-one articles used paper points for drying root canals. Four articles divided the sample according to the drying protocol and compared paper tips, 95% or 70% ethanol, and isopropyl alcohol, and seven articles did not mention what protocol they used.

3.2.6. Filling Technique

Six articles divided the sample according to the obturation technique, i.e., the cold lateral compaction technique, the thermoplastic injectable technique, the single cone technique and the hot vertical compaction technique.

3.2.7. Adhesion Evaluation

In total, 100% of the articles used the push-out bond strength (POBS) test to evaluate dentin adhesion. Nine articles also used scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) was used in a single article. Furthermore, 1 mm, 1.5 mm, 2 mm and 3 mm slices were used. Most of the articles used 1 mm thick slices.

3.2.8. Sealer

The most evaluated bioceramic sealers were: EndoSequence BC, TotalFill BC, iRoot SP, BioRoot RCS, MTA Fillapez, Endoseal MTA, CeraSeal, GuttaFlow Bioseal and SureSeal Root. The list of all cements, their composition, their manufacturer, and the number of times studied is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

List of commercially available bioceramic materials studied.

3.2.9. Comparison with AH Plus

Twenty articles of the total selected compared the bond strength of bioceramics with AH Plus resin cement.

3.2.10. Repair Materials

A total of 11 repair materials were evaluated. The most evaluated were MTA, Biodentine and EndoSequence Root Repair (ERRM).

3.3. Quality Assessment

Table 3 presents the results of the quality assessment, indicating an average compliance of 78% among the included studies. The scores ranged from a minimum of 64% to a maximum of 91%. Across the 42 articles reviewed, a consistent pattern emerged in terms of data quality, with clear introductions, objectives, and/or hypotheses (items 1 and 2). Methodological data and results were systematically presented (items 3 and 4), while only 17 articles addressed the calculation of sample size (item 5).

Table 3.

Quality assessment of the included studies.

Notably, points 6 to 9, which pertain to the randomization process, were not fulfilled by any of the studies. However, all studies reported the statistical analyses performed, presenting results along with their significance levels or confidence intervals (items 10 and 11). Fifteen out of the 42 articles acknowledged and addressed possible limitations in their methodologies (item 12).

Concerning funding sources, with the exception of two studies, all articles disclosed any financial support received (item 13). Interestingly, none of the articles referenced an available protocol (item 14).

4. Discussion

4.1. Instrumentation Protocol

The system used by most of the selected articles was the ProTaper rotary system (Dentsply). Two articles used a different instrumentation protocol depending on the research group. When compared, it was seen that the resistance to dislodgment in the canals prepared with SAD (self-adjusting file system) was greater than in the canals prepared with rotary or reciprocating files. The SAF system is a cleaning, shaping and irrigation system that implements a single action. The increased bond strength may be due to the lack of areas not instrumented. The use of SAF did not allow areas where debris was left or compacted in the recesses of the canal [40].

However, root canals shaped with 6% conical instruments showed stronger bonding than those prepared with 4% conical instruments, although this disparity did not achieve statistical significance. This trend might be linked to an increased linear resistance, as canals prepared with 6% tapered instruments provide a greater surface area for potential chemical bonding to the root dentin [48].

4.2. Final Irrigant

The composition and structure of root dentin, along with its permeability and solubility characteristics, can undergo changes when irrigated with various chelating agents [16]. These alterations impact the bond strength of root canal filling materials to dentin, influencing the sealants’ interaction with dentin [16]. Enhancing the surface roughness of root dentin contributes to increased adhesion, which can be attributed to a higher surface energy and bonding area [16]. Furthermore, the choice of irrigant, its concentration, and application time can significantly influence dentin wettability [16].

In a comparison of nine articles that categorized samples based on the final irrigant used in each intervention group, it was observed that 17% EDTA as a final irrigant increased the adhesion strength of the CSCs [16,29,43,47]. The alkaline pH of EDTA induces an abundance of hydroxyl ions, leading to smear layer dissociation, reduced chelation with calcium ions, and a slow dissolution of inorganic and organic components, resulting in higher surface roughness and favorable wettability, all contributing to elevated bond strength values. Smear layer removal facilitates closer contact between the cement and root dentin, a prerequisite for optimal adhesion [16].

Additionally, the application of a diode laser after conventional irrigation (NaOCl + EDTA) increased bond strength values, likely due to morphological and chemical changes in the root dentin post irradiation [17]. Conversely, activating irrigants with sonic or ultrasonic devices showed no significant effects [40].

4.3. Drying Protocol

When comparing the conventional drying protocol (paper tips) with 70% isopropyl alcohol, it was observed that the canals dried with isopropyl alcohol exhibited higher bond strength values in each third, across all sealers assessed (EndoSequence BC, AH Plus, and MTA Fillapex) [31]. However, varying humidity levels, as explored by Cardoso et al. [19], using three drying protocols (paper tips; irrigation with 95% ethanol followed by paper tips; and irrigation with 70% ethanol followed by aspiration with a 30-gauge needle), did not influence the bond strength of Sealer Plus BC endodontic cement to the root canal walls when employing the single cone technique for canal filling.

In the evaluation of bioceramic cements, namely, iRoot SP, MTA Fillapex, Endoseal MTA, and SureSeal Root, it was found that the optimal humidity conditions for achieving ideal strength involved normal humidity using the conventional protocol (paper tips), enhancing the adhesive strength of the sealers [46,49]. Calcium silicate and calcium phosphate in the composition of CSCs rely on humidity for the hydration reaction, allowing the sealer to set and harden [19]. Excessive drying removes water from dentinal tubules, challenging the penetration of the hydrophilic sealer and compromising adhesion quality. Conversely, excess water can negatively impact adhesion, trapping water droplets at the dentin–cementum interface in completely wet root canals, leading to decreased adhesion. Extreme situations, such as dehydrated or excessively hydrated canals, interfere negatively with cement adhesion to dentinal walls [19].

The presentation of the cement is another important consideration. A premixed bioceramic offers advantages such as reduced working time and immunity to manual mixing or changes in the powder–liquid ratio that could affect its physicochemical properties. In comparison to powder–liquid presentations, it may exhibit superior physicochemical properties concerning viscosity, solubility, and bond strength to root dentine [19].

It is noteworthy that while many studies only assess the sealer to examine the impact of humidity on the bond strength to root dentin, the behavior of these cements in clinical applications, particularly when used in conjunction with gutta-percha cones, should also be considered [19]. Consequently, the careful selection of the drying technique based on the type of cement used emerges as a critical step in endodontic treatment [46].

4.4. Filling Technique

Cold lateral compaction has demonstrated robust adhesion values in certain studies [37,42]. However, the thermoplastic injectable technique, specifically using the Calamus Flow Delivery System, has shown a weakening effect on the bond strength of EndoSequence BC [23]. This might be attributed to heightened sealer polymerization, as heat can expedite hydration reactions and the formation of hydroxyapatite. Calcium silicate-based sealers exhibit accelerated setting times with a subsequent decrease in flow rate. Consequently, this rapid setting results in increased stiffness, leading to a diminished bond strength [23].

Interestingly, the warm vertical compaction technique did not impact the bond strength when evaluating CeraSeal and BC HiFlow. However, it did have a negative effect on the bond strength of BioRoot [26]. Thermoplastic gutta-percha tends to shrink upon cooling, and this shrinkage can concentrate stress in the sealer, affecting its adhesion to the root dentin surface [26].

When it comes to filling without a gutta-percha cone, it has been observed that this approach yields a higher bond strength for cement sealers (CSCs) compared to samples filled with gutta-percha and cement. This difference is likely because sealers form more robust physical and chemical bonds with dentin than with gutta-percha. Additionally, the plastic deformation of gutta-percha can negatively impact resistance to dislocation [3].

4.5. Adhesive Strength Test

In the literature, the POBS assay stands out as one of the most frequently employed methods for studying the dislodgment resistance of cements. This test is particularly suitable for specimens with parallel sides, as dislocation occurs parallel to the dentin–material interface. Widely regarded as a reliable method, the POBS assay is employed to measure the bond strength of root canal filling materials [22].

On the other hand, nine articles utilized SEM, offering a valuable means of assessing the sealing capacity and adhesion of the sealer to the walls of the root dentin. SEM provides high magnification, enabling a detailed observation of surface morphology [11]. Furthermore, CLSM made an appearance in a single article.

The selected articles used 1 mm, 1.5 mm, 2 mm and 3 mm slices. According to Chen et al. [52], to correctly apply the push-out test, the thickness of the sample must be 0.6 times greater than the diameter of the seal to avoid influencing the values of the bond strength, that is, the thickness of the sample must be greater than 1.10 mm. They also proposed that the size of the plunger tip should be 0.85 times smaller than the size of the filling material [22]. The majority (25 articles) used the universal machine (Instron Corp., Norwood, MA, USA) (Schimadzu Corp., Tokyo, Japan) at a speed of 0.5 mm/min, while 16 articles used it at 1 mm/min. One article did not mention the speed used.

A notable challenge in push-out tests lies in the lack of standardization. Significant variability exists in both the parameters of the test itself, such as the diameter of the orifice of the base/tip of the applicator and the testing speed, and in the methods of sample preparation, including thickness, incubation time, and root canal diameter. These variations can introduce alterations in stress distribution patterns, contributing to the substantial discrepancies observed in numerical results obtained with the same materials [44].

4.6. CSC Sealers

CSC sealers including Ceraseal, EndoSequence BC, EndoSeal MTA, and BioRoot RCS, exhibited higher bond strengths compared to resin-based sealers like ADSEAL and RealSeal [11,22]. This difference is likely attributed to intrafibrillar apatite deposition. Variances in the chemical composition of CSC sealers can influence their interaction with root dentin, significantly impacting their adhesion [22]. Calcium silicate-based cements possess hydrophilic properties and an alkaline pH, rendering them insoluble in tissue fluids and resistant to shrinkage during setting. Moreover, the moisture environment within the tooth plays a crucial role in the adhesion between CSC and root canal dentin. These sealers also demonstrate potential bioactive properties, forming calcium hydroxide and hydroxyapatite upon contact with water [11].

Within the evaluated calcium silicate cements, TotalFill BC showcased the highest bond strength values when compared to BioRoot RCS, EndoCPM, Biodentine, and MTA [25,39]. TotalFill is a recognized CSC known for its biological properties (biocompatibility, bioactivity, and antibacterial activity) and favorable physicochemical attributes [21]. In contrast to conventional filling cements, TotalFill BC’s setting reaction is triggered by the moisture present in the dentinal tubules. This moisture prompts the sealer to form hydroxyapatite, ensuring optimal chemical adhesion between dentin and cement [21].

On the other hand, MTA Fillapex presented the lowest adhesion strength values when compared to Apexit Plus, AH Plus, TotalFill, Biodentine, Endoseal MTA and SureSeal Root [29,31,33,41]. MTA Fillapex is a cement based on the MTA formula. Its biggest difference is the resin matrix that it presents in its composition. It was created with the intention of combining the physicochemical properties of resins and the biological properties of MTA [48]. Its lower bond strength compared to other resin-based cements is because MTA does not bond to dentin, but the presence of the resins contained in MTA Fillapex increases the flow properties [53].

It should be highlighted that the included studies did not assess the POBS of the tested sealers from the perspective of the differences in their composition, i.e., the proportion of calcium silicate, radiopacifier, fillers, etc. Variations in the materials’ composition may lead to changes in their physical–chemical properties. This has been described previously regarding CSCs’ biological properties, in the way that the inclusion of additives like resin may influence their cytocompatibility negatively [54]. Conclusions in this regard cannot be extracted from the evidence assessed in this systematic review.

4.7. Comparison with AH Plus

The resin-based sealer AH Plus, selected for comparison with CSCs, has been widely utilized in previous studies and is considered a gold-standard sealer, due to its excellent physicochemical properties and strong adhesion to dentin [19].

The observations indicate that AH Plus demonstrates greater bond strength compared to CSCs such as EndoSequence BC, EndoSeal MTA, Tech Biosealer Endo, GuttaFlow Bioseal, Endo CPM, Apexit Plus, BioRoot RCS, and MTA Fillapex [23,24,25,27,29,33,41,43,45]. This difference may be attributed to covalent bonds between the epoxy resin and the amino groups of dentin collagen, resulting in a stronger bond between AH Plus and dentin compared to the interaction of calcium silicates with dentin. The micromechanical interaction between the root canal wall and the calcium silicate-based sealer, facilitated by tag-like structures, and the chemical interaction via the “mineral infiltration zone”, establish a weaker bond with dentin compared to epoxy resins [25].

Contrastingly, Khurana et al. [31] and Kuden et al. [32] concluded that EndoSequence BC and BioRoot RCS exhibited higher adhesion strengths than AH Plus. The routine use of NaOCl and EDTA, employed to dissolve organic and inorganic components, plays a role in this variation. While NaOCl negatively affects resin cement adhesion, EDTA creates favorable conditions for resin infiltration by exposing dentin collagen. This sequential use of solutions may be effective for hydrophobic epoxy cements but may not be suitable for calcium silicate-based cement types [32]. Kuden et al. [32] proposed exploring alternative methods like photodynamic therapy for root canal disinfection when using calcium silicate cements, as NaOCl/EDTA reduces adhesion to dentin [32].

4.8. Repair Materials

The introduction of mineral trioxide aggregate (MTA) marked a significant advancement in endodontics, offering attributes like biocompatibility, low solubility, radiopacity, hard tissue inductive and conductive activity, and the ability to set in a wet environment [39]. MTA finds diverse clinical applications, including apexification, vital pulp therapy, the repair of perforations and resorptions, regenerative endodontics, and root canal obturation [44]. However, drawbacks include a prolonged setting time, handling challenges, tooth discoloration, and high cost [39].

Biodentine, with comparable mechanical properties and clinical applications to MTA, is a fast-setting calcium silicate-based product recommended as a dentin substitute. Notably, it offers superior color stability compared to MTA, contributing to better aesthetic outcomes [39].

CSCs were introduced to address MTA’s limitations in endodontics, serving as a root repair material and canal sealer. EndoSequence Root Repair Material (ERRM), a hydrophilic, insoluble, radiopaque calcium silicate-based nano-bioceramic material, stands out for its bioactive and bioresorbable nature. ERRM actively participates in the dynamic process of bone formation and resorption, promoting bone regeneration and facilitating the repair of periodontal tissue [13].

Studies, such as those by Paulo et al. [39], Kadic et al. [55], Al-Hiyasat et al. [56], Akcay et al. [57], and Marquezan et al. [35], have consistently shown that ERRM and Biodentine exhibit higher bond strength values compared to MTA. The nanosphere particles of ERRM, contributing to a greater surface area in contact with tissue fluids, and its consistent and favorable handling properties are cited as potential factors for its superior results [39]. Biodentine’s enhanced bonding strength is attributed to the addition of calcium chloride to its composition, which acts as a catalyst for tricalcium silicate hydration. This process leads to rapid crystallization and the formation of areas with heterogeneous density, facilitating ion and water diffusion, thereby improving biomineralization and bond strength [39,57].

Recent studies have explored the incorporation of additives such as hydroxyapatite, collagen, and calcium phosphate to enhance the bioactive potential of calcium silicate-based materials [58].

4.9. Limitations

Given the in vitro nature of the included studies, it is essential to recognize that generalizing and extrapolating the results to a clinical setting may be challenging. A limitation arises from the fact that these studies do not account for the influence of various potential external factors that could come into play in the clinical scenario. Thus, the clinical relevance of the present review remains limited. Expanding on the knowledge of the basic properties of calcium silicate-based materials, such as dentin adhesion, may act as a starting point for future research on their physical–chemical properties and the development of new material compositions with improved characteristics. Nevertheless, clinicians may benefit from considerations such as the differences observed between the tested materials or the influence of the irrigation protocol in dentin adhesion.

In the absence of a specific quality assessment tool tailored to the type of studies included in this review, the modified CONSORT checklist by Faggion et al. was employed. It is noteworthy that this checklist does not offer a quality indicator (such as high/medium/low) based on the compliance with the proposed items. However, to gauge an objective measure of quality, a percentage of compliance with the checklist items was calculated for each study. Remarkably, all the studies included and evaluated demonstrated a high percentage of compliance with the checklist items, implying a low risk of bias.

Due to the heterogeneity of the included studies, a quantitative synthesis or meta-analysis could not be performed. In addition, the qualitative synthesis was hindered due to the wide variety of materials and comparisons performed, added to the fact that various studies only assessed one material. This highlights the need for further studies in the field to confirm the existing results and to serve as contrasting evidence from which to draw specific conclusions.

4.10. Future Perspectives

Despite the great variety of endodontic CSCs and the large amount of research on them, more well-controlled clinical trials are still needed to provide high-level evidence, using more sensitive methods during the sectioning, storage, and treatment of samples.

On the other hand, to better address clinical challenges, efforts are necessary to improve the bioactivity of CSCs to improve their antimicrobial activity as well as reduce their setting time and solubility.

5. Conclusions

Calcium silicate-based cements and sealers, in general, tend to demonstrate a high bonding strength to root dentin. Notably, among the tested sealers, TotalFill BC sealer showed the highest bonding strength values based on the in vitro studies assessed. Similarly, among the tested cements, EndoSequence Root Repair Material exhibited the highest bonding strength values to root dentin. Furthermore, it was observed that using 17% EDTA as the final irrigant enhances the adhesion strength of CSCs.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/app14010104/s1, Table S1: POBS results from the included studies. References [3,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,35,36,37,39,40,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,52] are cited in the Supplementary Materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.R. and A.L.; data curation, J.L.S.; formal analysis, A.L.; funding acquisition, A.L.; investigation, N.R. and A.L.; methodology, N.R. and A.L.; project administration, A.L.; resources, J.L.S.; software, J.L.S.; supervision, J.L.S. and A.L.; visualization, J.L.S.; writing—original draft, N.R. and A.L.; writing—review and editing, J.L.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Rangel Cobos, O.M.; Luna Lara, C.A.; Téllez Garza, A.; Ley Fong, M.T. Obturación del sistema de conductos rootes: Revisión de literatura. Rev. ADM 2018, 75, 269–272. [Google Scholar]

- Llanos-Carazas, M.Y. Evolución de los cementos biocerámicos en endodoncia. Conoc. Para El Desarro. 2019, 10, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retana-Lobo, C.; Tanomaru-Filho, M.; Guerreiro-Tanomaru, J.M.; Benavides-García, M.; Hernández-Meza, E.; Reyes-Carmona, J. Push-Out Bond Strength, Characterization, and Ion Release of Premixed and Powder-Liquid Bioceramic Sealers with or without Gutta-Percha. Scanning 2021, 2021, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallittu, P.K.; Boccaccini, A.R.; Hupa, L.; Watts, D.C. Bioactive dental materials-Do they exist and what does bioactivity mean? Dent. Mater. 2018, 34, 693–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Páez Mejía, A.; Cano, C.O.; de Fátima Restrepo, L. Adhesión dental: Sustrato biológico e implicaciones clínicas. Rev. Fac. Odontol. 1992, 8, 21–38. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, J.; Kirkpatrick, T.; Roberts, H.W. Dislodgement pushout resistance of five bioceramic root-end filling materials. Dent. Mater. J. 2022, 41, 843–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paradella, T.C.; Bottino, M.A. Scanning Electron Microscopy in modern dentistry research. Braz. Dent. Sci. 2012, 15, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yolcu, E.N.; Tartuk, G.A.; Kaya, S.; Eskibağlar, M. The use of confocal laser scanning microscopy in endodontics: A literature review. Turk. Endod. J. 2021, 6, 55–60. [Google Scholar]

- PRISMA-P. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: Elaboration and explanation. BMJ 2016, 354, i4086. [Google Scholar]

- Faggion, C.M. Guidelines for reporting pre-clinical in vitro studies on dental materials. J. Evid. Based Dent. Pract. 2012, 12, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelrahman, M.H.; Hassan, M.Y. A comparative evaluation of the sealing ability of two calcium silicate based sealers and a resin epoxy-based sealer through scanning electron microscopy and bond strength: An in vitro study. Braz. J. Oral Sci. 2021, 20, e214073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aktemur, S.; Uzunoĝlu, E.; Purali, N. Evaluation of dentinal tubule penetration depth and push-out bond strength of AH 26, BioRoot RCS, and MTA Plus root canal sealers in presence or absence of smear layer. J. Dent. Res. Dent. Clin. Dent. Prospect. 2018, 12, 294–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alamoudi, R.A.; Abu Zeid, S.T. Effect of Irrigants on the Push-Out Bond Strength of Two Bioceramic Root Repair Materials. Materials 2019, 12, 1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Haddad, A.Y.; Kacharaju, K.R.; Haw, L.Y.; Yee, T.C.; Rajantheran, K.; Mun, C.S.; Ismail, M.F. Effect of Intracanal Medicaments on the Bond Strength of Bioceramic Root Filling Materials to Oval Canals. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2020, 21, 1218–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsubait, S.; Alsaad, N.; Alahmari, S.; Alfaraj, F.; Alfawaz, H.; Alqedairi, A. The effect of intracanal medicaments used in Endodontics on the dislocation resistance of two calcium silicate-based filling materials. BMC Oral Health 2020, 20, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anju, P.K.; Purayil, T.P.; Ginjupalli, K.; Ballal, N.V. Effect of Chelating Agents on Push-Out Bond Strength of NeoMTA Plus to Root Canal Dentin. Pesqui. Bras. Odontopediatria Clin. Integr. 2022, 22, e210058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bago, I.; Sandrić, A.; Beljic-Ivanovic, K.; Pažin, B. Influence of irrigation and laser assisted root canal disinfection protocols on dislocation resistance of a bioceramic sealer. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2022, 40, 103067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogari, D.F.; Alessa, M.; Aljaber, M.; Alghamdi, F.; Alamoudi, M.; Alhamed, M.; Alghamdi, A.J.; Elsherief, S.; Almalki, M.; Alhazzazi, T.Y. The Biological and Mechanical Effect of Using Different Irrigation Methods on the Bond Strength of Bioceramic Sealer to Root Dentin Walls. Cureus 2022, 14, e24022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, I.V.; Seixas-Silva, M.L.; Rover, G.; Bortoluzzi, E.A.; Garcia, L.F.R.; Teixeira, C.S. Influence of different root canal drying protocols on the bond strength of a bioceramic endodontic sealer. G. Ital. Endod. 2022, 36, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celik, D.; Ozalp Koca, A.T.; Kosar, T.; Tasdemir, T. The effects of final irrigants on the push-out bond strength of two calcium silicate-based root canal sealers: An in vitro study. Eur. Oral Res. 2021, 55, 146–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chisnoiu, R.M.; Moldovan, M.; Prodan, D.; Chisnoiu, A.M.; Hrab, D.; Delean, A.G.; Muntean, A.; Rotaru, D.I.; Pastrav, O.; Pastrav, M. In-Vitro Comparative Adhesion Evaluation of Bioceramic and Dual-Cure Resin Endodontic Sealers Using SEM, AFM, Push-Out and FTIR. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 4454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimpean, S.I.; Burtea, A.L.C.; Chiorean, R.S.; Dudescu, M.C.; Antoniac, A.; Robu, A. Evaluation of Bond Strength of Four Different Root Canal Sealers. Materials 2022, 15, 4966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dabaj, P.; Kalender, A.; Eldeniz, A.U. Push-Out Bond Strength and SEM Evaluation in Roots Filled with Two Different Techniques Using New and Conventional Sealers. Materials 2018, 11, 1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dem, K.; Wu, Y.; Kaminga, A.C.; Dai, Z.; Cao, X.; Zhu, B. The push out bond strength of polydimethylsiloxane endodontic sealers to dentin. BMC Oral Health 2019, 19, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donnermeyer, D.; Dornseifer, P.; Schäfer, E.; Dammaschke, T. The push-out bond strength of calcium silicate-based endodontic sealers. Head Face Med. 2018, 14, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falakaloğlu, S.; Gündoğar, M. Evaluation of the push out of bond strength of different bioceramic root canal sealers with different obturation techniques. G. Ital. Endod. 2022, 36, 151–157. [Google Scholar]

- Grazziotin-Soares, R.; Dourado, L.G.; Gonçalves, B.L.L.; Ardenghi, D.M.; Ferreira, M.C.; Bauer, J.; Carvalho, C.N. Dentin Microhardness and Sealer Bond Strength to Root Dentin are Affected by Using Bioactive Glasses as Intracanal Medication. Materials 2020, 13, 721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gündoğar, M.; Sezgin, G.P.; Erkan, E.; Özyılmaz, Ö.Y. The influence of the irrigant QMix on the push-out bond strength of a bioceramic endodontic sealer. Eur. Oral Res. 2018, 52, 64–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashem, M.; El-Hejazi, A.A.; Niaz, M.O.; Alsadon, O.; Alolayani, B.M.; Fouad, H. Bond strength of root canal filling with root dentin previously treated with either photobiomodulation or photodynamic therapy: Effect of disinfection protocols. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2020, 30, 101733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, M.M.; Abdelrahman, M.H.; El-Mallah, S. Bond strength and solubility of a novel polydimethylsiloxane-gutta percha calcium silicate-containing root canal sealer. Dent. Med. Probl. 2019, 56, 161–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khurana, N.; Chourasia, H.R.; Singh, G.; Mansoori, K.; Nigam, A.S.; Jangra, B. Effect of Drying Protocols on the Bond Strength of Bioceramic, MTA and Resin-based Sealer Obturated Teeth. Int. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2019, 12, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Küden, C.; Karakaş, S.N. Effect of three different photosensitizers in photodynamic therapy on bond strength of a calcium silicate-based sealer to root dentin. Aust. Endod. J. 2022, 49, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurup, D.; Nagpal, A.K.; Shetty, S.; Mandal, T.K.; Anand, J.; Mitra, R. Data on the push–out bond strength of three different root canal treatment sealers. Bioinformation 2021, 17, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindblad, R.M.; Lassila, L.V.J.; Vallittu, P.K.; Tjäderhane, L. The effect of chlorhexidine and dimethyl sulfoxideon long-term sealing ability of two calcium silicatecements in root canal. Dent. Mater. 2021, 37, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marquezan, F.K.; Kopper, P.M.P.; Dullius, A.I.S.; Ardenghi, M.; Grazziotin-Soares, R. Effect of Blood Contamination on the Push-Out Bond Strength of Calcium Silicate Cements. Braz. Dent. J. 2018, 29, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moinuddin, M.K.; Prasad, L.K.; Ramachandruni, N.; Kamishetty, S.; Cherkupalli, R.C. Comparison of Push-out Bond Strength of Three Different Obturating Systems to Intraroot Dentin: An In vitro Study. Contemp. Clin. Dent. 2019, 10, 631–636. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nouroloyouni, A.; Samadi, V.; Salem Milani, A.; Noorolouny, S.; Valizadeh-Haghi, H. Single Cone Obturation versus Cold Lateral Compaction Techniques with Bioceramic and Resin Sealers: Quality of Obturation and Push-Out Bond Strength. Int. J. Dent. 2023, 2023, 3427151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oktay, E.A.; Ersahan, S.; Gokyay, S. Effect of intracanal medicaments used in endodontic regeneration on the push-out bond strength of a calciumphosphate-silicate-based cement to dentin. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2018, 34, 310–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulo, C.R.; Marques, J.A.; Sequeira, D.B.; Diogo, P.; Paiva, R.; Palma, P.J.; Santos, J.M. Influence of Blood Contamination on Push-Out Bond Strength of Three Calcium Silicate-Based Materials to Root Dentin. Dentin. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 6849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawar, A.M.; Kfir, A.; Metzger, Z.; Bhardwaj, A.; Yohana, Y.; Wahjuningrun, D.A.; Luke, A.M.; Pawar, B.A. Can Type of Instrumentation and Activation of the Final Irrigant Improve the Obturation Quality in Oval Root Canals? A Push-Out Bond Strength Study. Biology 2022, 11, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prado, M.C.; Carvalho, N.K.; Vitti, R.P.; Ogliari, F.A.; Sassone, L.M.; Silva, E.J.N.L. Bond Strength of Experimental Root Canal Sealers Based on MTA and Butyl Ethylene Glycol Disalicylate. Braz. Dent. J. 2018, 29, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Putrianti, A.; Usman, M.; Nazar, K.; Meidyawati, R.; Suprastiwi, E.; Mahardhini, S. Effect of cold lateral versus warm vertical compaction obturation on the push-out bond strength of BioRoot, a calcium silicate-based sealer. Int. J. App Pharm. 2020, 12, 77–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rifaat, S.; Rahoma, A.; Alkhalifa, F.; AlQuraini, G.; Alsalman, Z.; Alwesaibi, Z.; Taymour, N. Push-Out Bond Strength of EndoSeal Mineral Trioxide Aggregate and AH Plus Sealers after Using Three Different Irrigation Protocols. Eur. J. Dent. 2022, 17, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, M.N.M.; Bruno, K.F.; Alencar, A.H.G.; Silva, J.D.S.; Siquiera, P.C.; Decurcio, D.A.; Estrela, C. Comparative analysis of bond strength to root dentin and compression of bioceramic cements used in regenerative endodontic procedures. Restor. Dent. Endod. 2021, 46, e59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, D.; Kataki, R.; Das, L.; Jain, K. Influence of 2% chlorhexidine on the dislodgement resistance of AH plus, bioroot RCS, and GuttaFlow 2 sealer to dentin and sealer-dentin interface. J. Conserv. Dent. 2022, 25, 642–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarrafan, A.; Soleymani, A.; Bagheri Chenari, T.; Seyedmajidi, S. Comparison of push-out bond strength of endodontic sealers after root canal drying with different techniques. Clin. Exp. Dent. Res. 2023, 9, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sfeir, G.; Bukiet, F.; Hage, W.; El Hachem, R.; Zogheib, C. Impact of final irrigation protocol on the push-out bond strength of two types of endodontic sealers. Materials 2023, 16, 1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasavi, N.; Sirisha, K. Micro-push-out bond strength of Mineral—Based root canal sealer in canals with different tapers. J. Oral Res. 2021, 10, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.S.; Bai, W.; Wang, Y.; Liang, Y.H. Effect of different dentin moisture on the push-out strength of bioceramic root canal sealer. J. Dent. Sci. 2023, 18, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaghmoor, R.B.; Platt, J.A.; Spolnik, K.J.; Chu, T.M.G.; Yassen, G.H. Effect of Hydrogel-Based Antibiotic Intracanal Medicaments on Push-Out Bond Strength. Eur. J. Dent. 2020, 14, 575–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeter, K.Y.; Güneş, B.; Terlemez, A.; Şeker, E. The Effect of Nonthermal Plasma on the Push-Out Bond Strength of Two Different Root Canal Sealers. Niger. J. Clin. Pract. 2020, 23, 811–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, B.; Haapasalo, M.; Mobuchon, C.; Li, X.; Ma, J.; Shen, Y. Cytotoxicity and the Effect of Temperature on Physical Properties and Chemical Composition of a New Calcium Silicate-based Root Canal Sealer. J. Endod. 2020, 46, 531–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez Vázquez, P.; Estévez Luaña, R.; Valencia de Pablo, O.; Cisneros Cabello, R. Importancia de la activación de la irrigación durante el tratamiento de conductos: Una revisión de la literatura. Cient. Dent. 2015, 12, 61–69. [Google Scholar]

- Sanz, J.L.; Soler-Doria, A.; López-García, S.; García-Bernal, D.; Rodríguez-Lozano, F.J.; Lozano, A.; Llena, C.; Forner, L.; Guerrero-Gironés, J.; Melo, M. Comparative Biological Properties and Mineralization Potential of 3 Endodontic Materials for Vital Pulp Therapy: Theracal PT, Theracal LC, and Biodentine on Human Dental Pulp Stem Cells. J. Endod. 2021, 47, 1896–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadic, S.; Baraba, A.; Miletic, I.; Ionescu, A.; Brambilla, E.; Ivanisevic Malcic, A.; Gabric, D. Push-out bond strength of three different calcium silicate-based root-end filling materials after ultrasonic retrograde cavity preparation. Clin. Oral Investig. 2018, 22, 1559–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hiyasat, A.S.; Yousef, W.A. Push-Out Bond Strength of Calcium Silicate-Based Cements in the Presence or Absence of a Smear Layer. Int. J. Dent. 2022, 2022, 7724384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akcay, H.; Arslan, H.; Akcay, M.; Mese, M.; Sahin, N.N. Evaluation of the bond strength of root-end placed mineral trioxide aggregate and Biodentine in the absence/presence of blood contamination. Eur. J. Dent. 2016, 10, 370–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Gironés, J.; Alcaina-Lorente, A.; Ortiz-Ruiz, C.; Ortiz-Ruiz, E.; Pecci-Lloret, M.P.; Ortiz-Ruiz, A.J.; Rodríguez-Lozano, F.J.; Pecci-Lloret, M.R. Biocompatibility of a HA/β-TCP/C Scaffold as a Pulp-Capping Agent for Vital Pulp Treatment: An In Vivo Study in Rat Molars. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).