Non-Surgical Camouflage Treatment of a Skeletal Class III Patient with Anterior Open Bite and Asymmetry Using Orthodontic Miniscrews and Intermaxillary Elastics

Abstract

1. Introduction

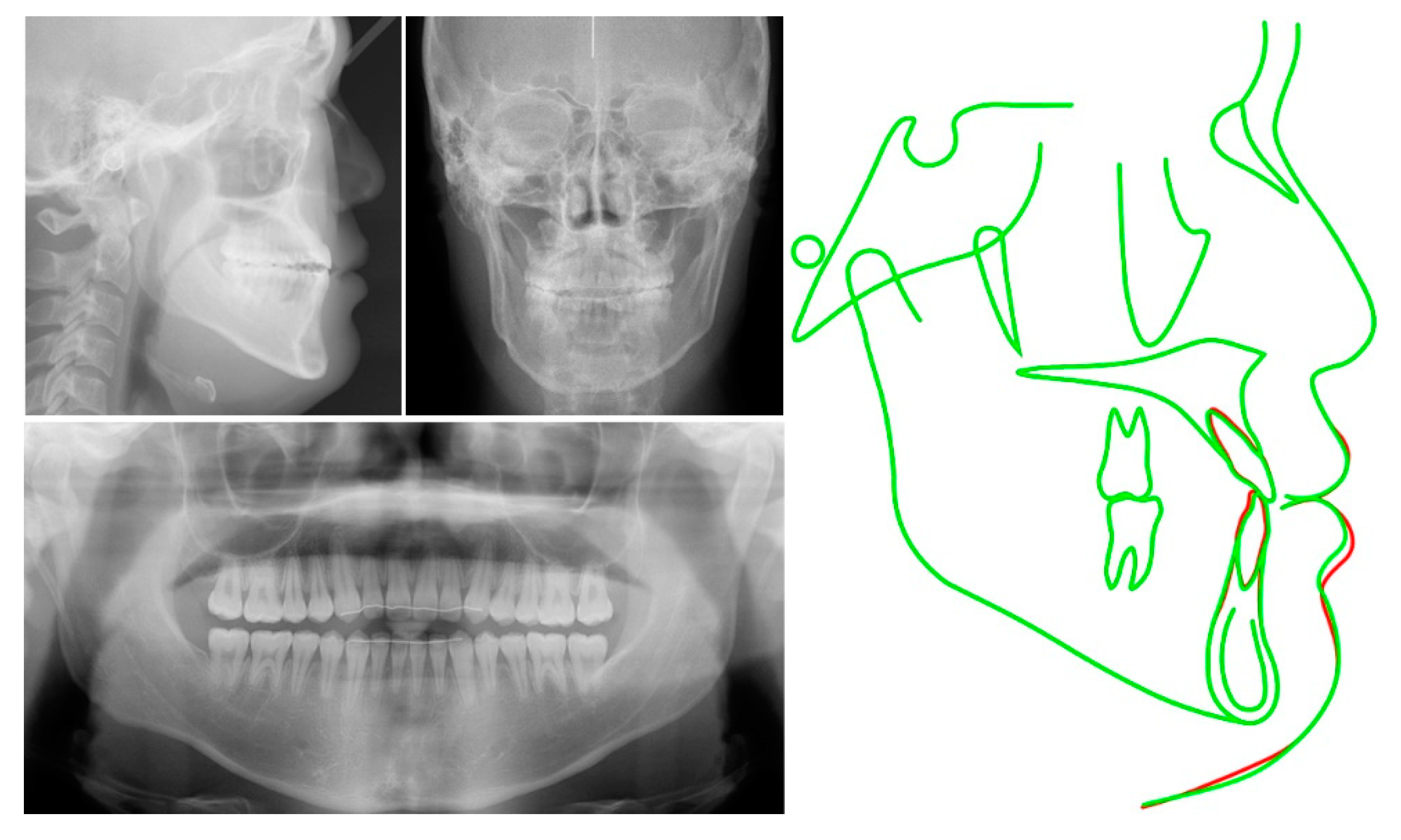

2. Case Report

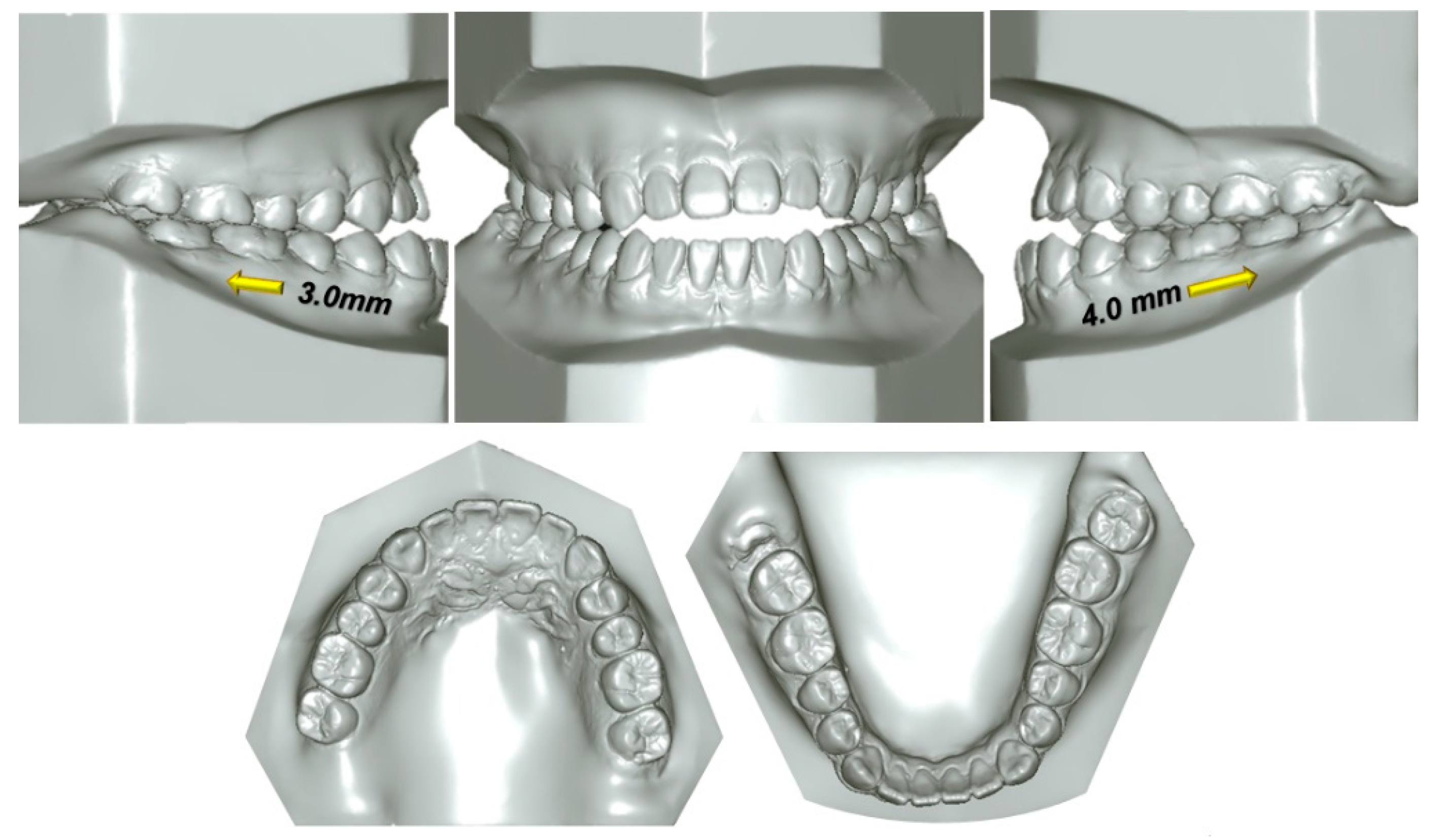

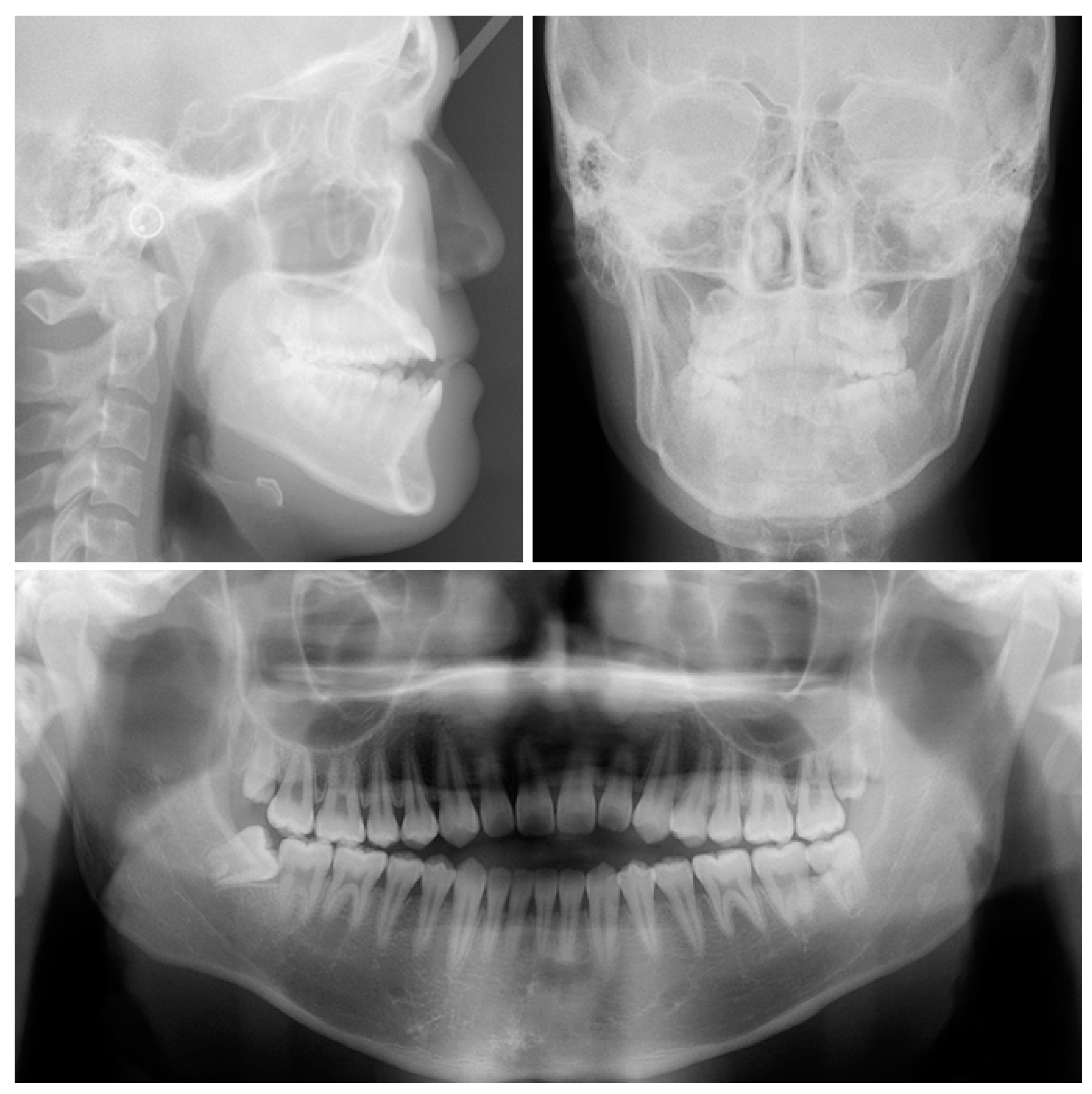

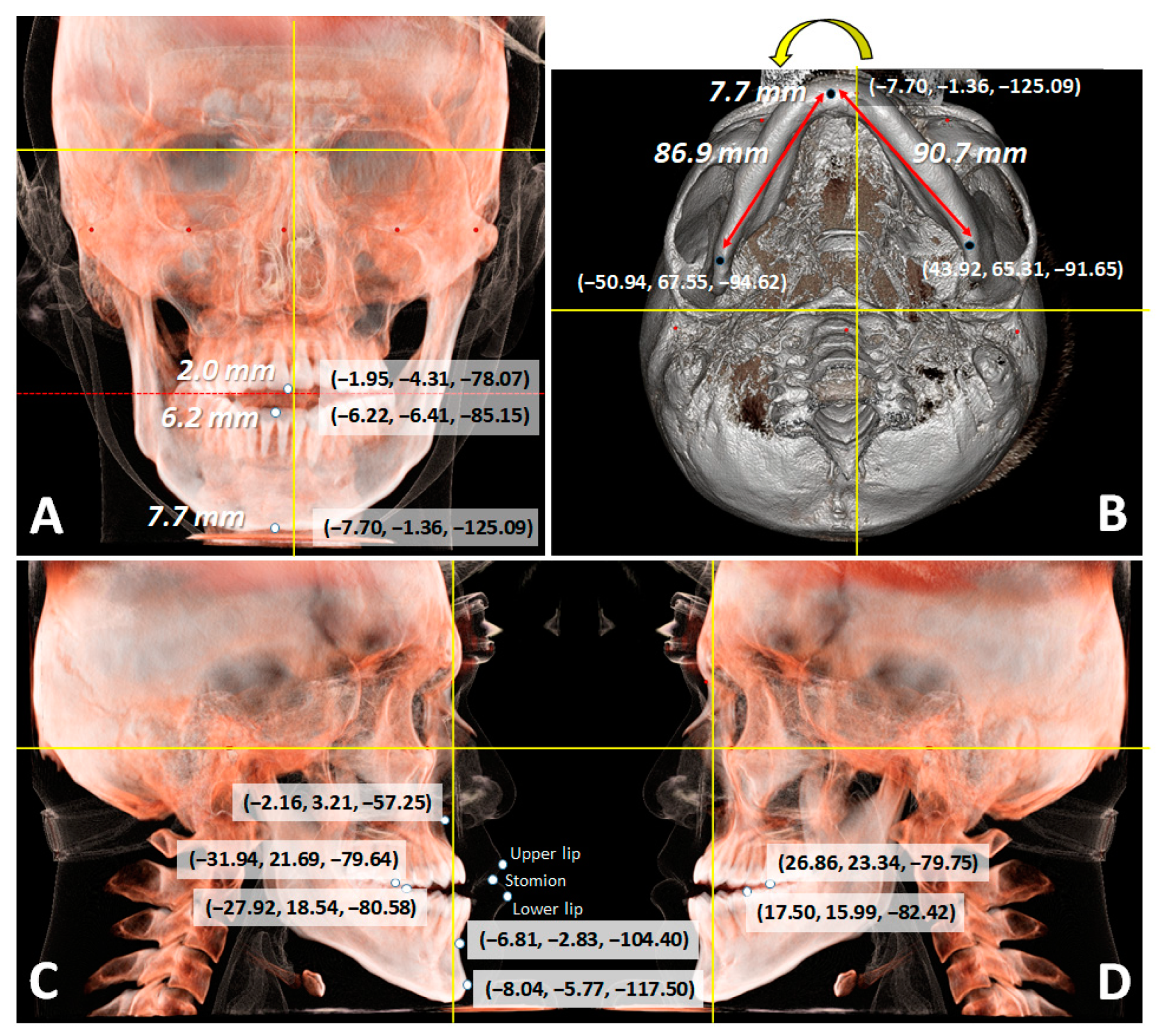

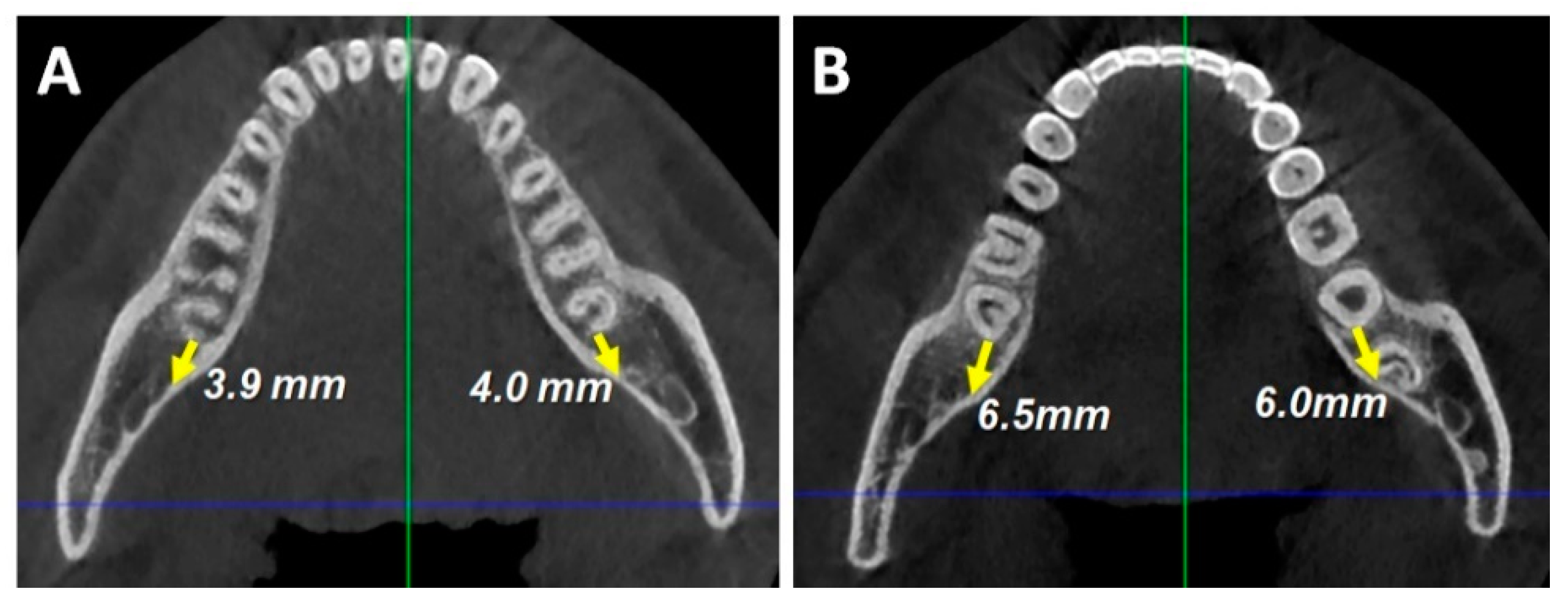

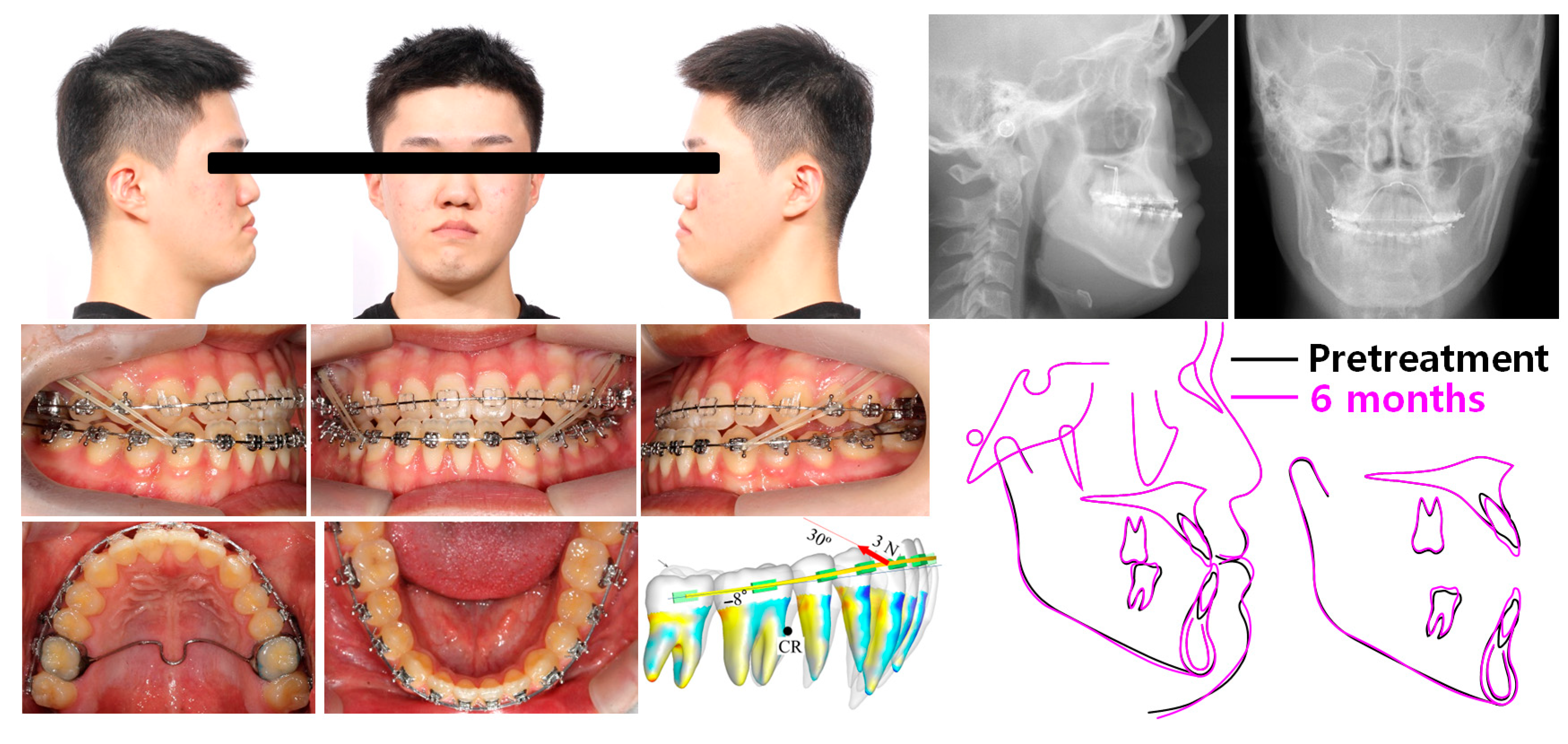

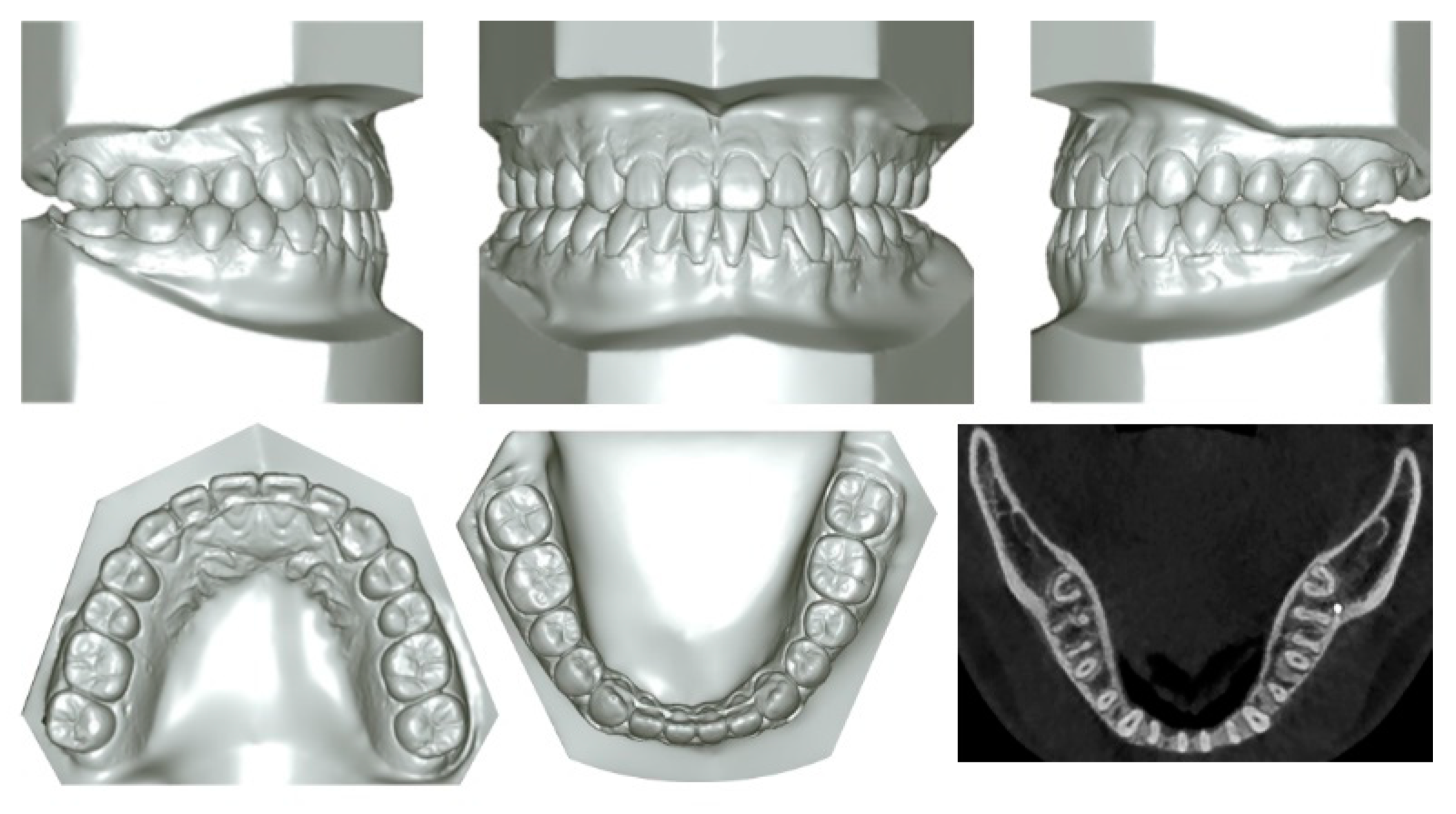

2.1. Diagnosis and Etiology

2.2. Treatment Objectives

2.3. Treatment Plan

2.4. Treatment Progress

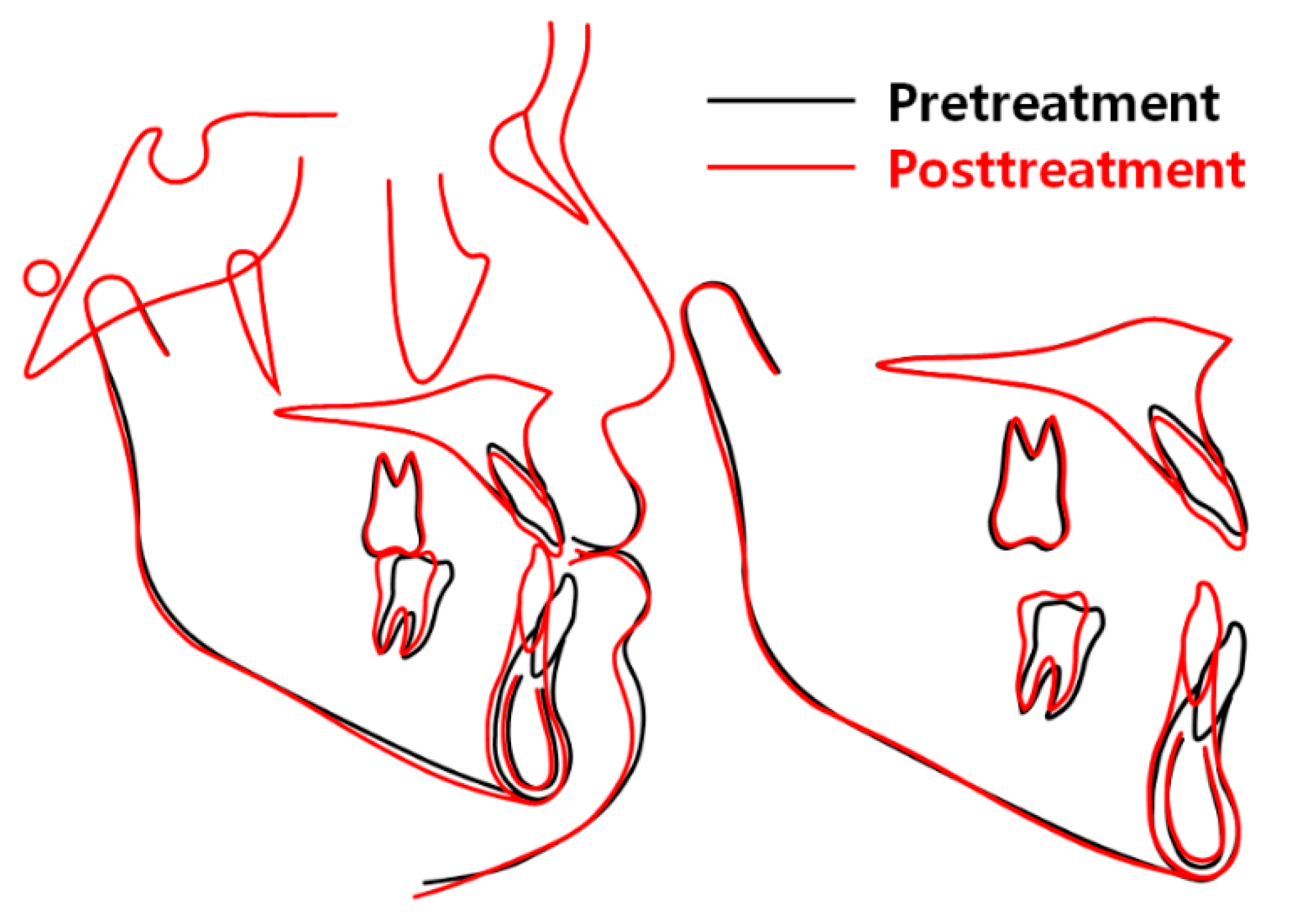

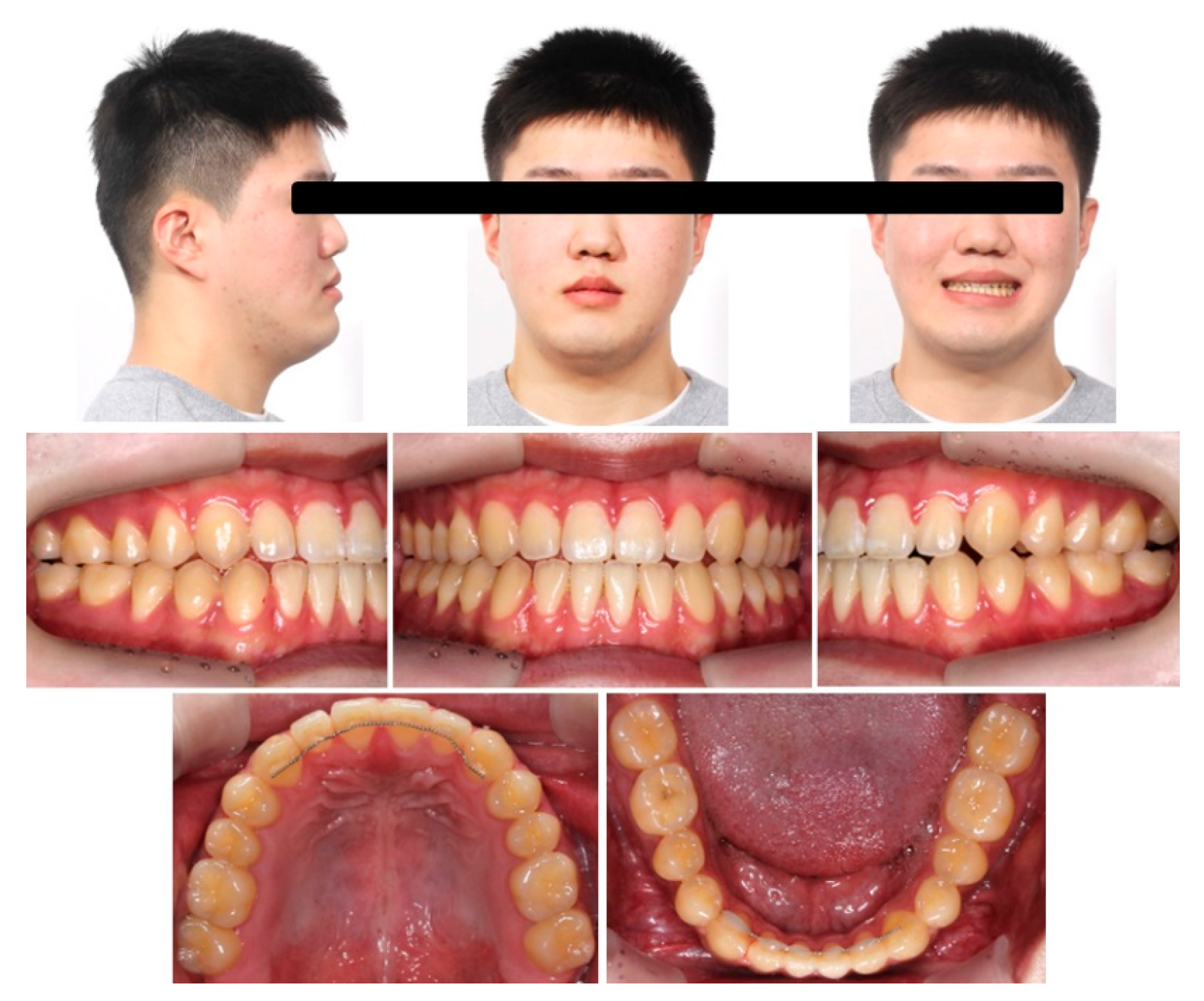

2.5. Treatment Results

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ellis, E., 3rd; McNamara, J.A., Jr. Components of adult Class III open-bite malocclusion. Am. J. Orthod. 1984, 86, 277–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnett, G.W.; Trevisiol, L.; Grendene, E.; McLaughlin, R.P.; D’Agostino, A. Combined orthodontic and surgical open bite correction: Principles for success. Part 1. Angle Orthod. 2022, 92, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnett, G.W.; D’Agostino, A.; Grendene, E.; McLaughlin, R.P.; Trevisiol, L. Combined orthodontic and surgical open bite correction: Principles for success. Part 2. Angle Orthod. 2022, 92, 431–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.H.; Papademetriou, M.; Gardiner, C.; Grubb, J. Anterior open bite correction with 2-jaw orthognathic surgery. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2019, 155, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proffit, W.R.; Bailey, L.J.; Phillips, C.; Turvey, T.A. Long-term stability of surgical open-bite correction by Le Fort I osteotomy. Angle Orthod. 2000, 70, 112–117. [Google Scholar]

- Swinnen, K.; Politis, C.; Willems, G.; De Bruyne, I.; Fieuws, S.; Heidbuchel, K.; van Erum, R.; Verdonck, A.; Carels, C. Skeletal and dento-alveolar stability after surgical-orthodontic treatment of anterior open bite: A retrospective study. Eur. J. Orthod. 2001, 23, 547–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beane, R.A., Jr. Nonsurgical management of the anterior open bite: A review of the options. Semin. Orthod. 1999, 5, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umemori, M.; Sugawara, J.; Mitani, H.; Nagasaka, H.; Kawamura, H. Skeletal anchorage system for open-bite correction. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 1999, 115, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamamci, N.; Başaran, G.; Sahin, S. Nonsurgical correction of an adult skeletal class III and open-bite malocclusion. Angle Orthod. 2006, 76, 527–532. [Google Scholar]

- Kuroda, S.; Sakai, Y.; Tamamura, N.; Deguchi, T.; Takano-Yamamoto, T. Treatment of severe anterior open bite with skeletal anchorage in adults: Comparison with orthognathic surgery outcomes. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2007, 132, 599–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.C.; Lee, H.A.; Choi, N.C.; Kim, D.H. Open bite correction by intrusion of posterior teeth with miniscrews. Angle Orthod. 2008, 78, 699–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chae, J.M.; Park, J.H.; Kojima, Y.; Tai, K.; Kook, Y.A.; Kyung, H.M. Biomechanical analysis for total distalization of the mandibular dentition: A finite element study. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2019, 155, 388–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Yu, J.; Chae, J.M. Lateral open bite and crossbite correction in a Class III patient with missing maxillary first premolars. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2017, 152, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daher, W.; Caron, J.; Wechsler, M.H. Nonsurgical treatment of an adult with a Class III malocclusion. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2007, 132, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.H.; Heo, S.; Tai, K.; Kojima, Y.; Kook, Y.A.; Chae, J.M. Biomechanical considerations for total distalization of the mandibular dentition in the treatment of Class III malocclusion. Semin. Orthod. 2020, 26, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burford, D.; Noar, J.H. The causes, diagnosis and treatment of anterior open bite. Dent. Update 2003, 30, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.H. Anterior openbite and its treatment with multiloop edgewise archwire. Angle Orthod. 1987, 57, 290–321. [Google Scholar]

- Hollander, Z.; Fraser, A.; Paredes, N.; Bui, J.; Chen, Y.; Moon, W. Nonsurgical maxillary orthopedic protraction treatment for an adult patient with hyperdivergent facial morphology, Class III malocclusion, and bilateral crossbite. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2022, 162, 264–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, H.N.; Lim, S.Y.; Kwon, S.M.; Cha, J.Y. Camouflage treatment for skeletal Class III patient with facial asymmetry using customized bracket based on CAD/CAM virtual orthodontic system. Angle Orthod. 2020, 90, 607–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, D.D.; Oliveira, B.F.; Mordente, C.M.; Godoy, G.M.; Soares, R.V.; Seraidarian, P.I. Successful and stable orthodontic camouflage of a mandibular asymmetry with sliding jigs. J. Orthod. 2018, 45, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, K.; Ojima, K.; Dan, C.; Upadhyay, M.; Alshehri, A.; Kuo, C.L.; Mu, J.; Uribe, F.; Nanda, R. Evaluation of open bite closure using clear aligners: A retrospective study. Prog. Orthod. 2020, 24, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venugopal, A.; Srirengalakshmi, M.; Marya, A.; Manzano, P. Periodontally compromised severe skeletal Class III with open bite corrected by orthodontic camouflage using temporary anchorage devices. APOS Trends Orthod. 2020, 10, 253–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobral, M.C.; Habib, F.A.; Nascimento, A.C. Vertical control in the Class III compensatory treatment. Dent. Press J. Orthod. 2013, 18, 141–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kondo, E.; Aoba, T.J. Nonsurgical and nonextraction treatment of skeletal Class III open bite: Its long-term stability. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2000, 117, 267–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, Y.J.; Kim, D.J.; Nam, J.; Chung, C.J.; Kim, K.H. Cephalometric configuration of the occlusal plane in patients with anterior open bite. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2016, 149, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Brito Vasconcelos, J.; de Almeida-Pedrin, R.R.; Poleti, T.M.F.F.; Oltramari, P.; de Castro Conti, A.C.F.; Bicheline, M.H.B.; Lindauer, S.J.; de Almeida, M.R. A prospective clinical trial of the effects produced by the extrusion arch in the treatment of anterior open bite. Prog. Orthod. 2020, 20, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, S.; Park, J.H.; Lee, M.Y.; Kim, J.S.; Jung, S.P.; Chae, J.M. Maxillary incisor position-based orthodontic treatment with miniscrews. Semin. Orthod. 2022, 28, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, J.K.; Kwon, O.W.; Sung, J.H. A cephalometric analysis on esthetic facial soft tissue of Korean young adult female. Korean J. Orthod. 1997, 27, 245–258. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.H.; Choy, K.C.; Kim, H.G.; Park, K.H. Cephalometric norms of the hard tissues of Korean for orthognathic surgery. J. Korean Assoc. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2001, 27, 221–230. [Google Scholar]

- Fudalej, P. Long-term changes of the upper lip position relative to the incisal edge. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2008, 133, 204–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deguchi, T.; Kurosaka, H.; Oikawa, H.; Kuroda, S.; Takahashi, I.; Yamashiro, T.; Takano-Yamamoto, T. Comparison of orthodontic treatment outcomes in adults with skeletal open bite between conventional edgewise treatment and implant-anchored orthodontics. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2011, 139, S60–S68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, B.J.; Lee, K.J.; Cha, J.Y.; Lee, J.S.; Mo, S.S.; Yu, H.S. Stability of the maxillary and mandibular total arch distalization using temporary anchorage devices (TADs) in adults. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 2898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, F.; Duan, Y. Camouflage treatment in adult skeletal Class III cases by extraction of two lower premolars. Korean J. Orthod. 2010, 40, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farret, M.M.; Farret, M.M.; Farret, A.M. Skeletal Class III and anterior open bite treatment with different retention protocols: A report of three cases. J. Orthod. 2012, 39, 212–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enacar, A.; Ugur, T.; Toroglu, S. A method for correction of open bite. J. Clin. Orthod. 1996, 30, 43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Chia, M.S.Y.; Naini, F.B.; Gill, D.S. The etiology, diagnosis and management of mandibular asymmetry. Ortho. Update 2008, 1, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, E.J. Long-term stability after treatment with removable appliances. Br. J. Orthod. 1983, 10, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albaker, B.; Rabie, B.; Wong, R. A new skeletal retention system for retaining anterior open bites. APOS Trends Orthod. 2013, 3, 49–53. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, J.R. Treatment of a twice-relapsed anterior open bite using temporary anchorage devices, myofunctional therapy, and fixed passive self-ligating appliances. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2020, 157, 832–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Norm | T1 | T2 (6 Months) | T3 (15 Months) | T4 (22 Months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNA (°) | 82.4 | 81.7 | 81.7 | 81.4 | 81.4 |

| SNB (°) | 80.4 | 85.4 | 85.4 | 84.6 | 84.6 |

| ANB (°) | 2.0 | −3.7 | −3.7 | −3.2 | −3.2 |

| AO-BO (mm) | −2.2 | −9.8 | −8.5 | −6.6 | −5.2 |

| APDI | 85.9 | 92.4 | 92.3 | 91.4 | 90.8 |

| ODI | 73.3 | 55.8 | 55.2 | 55.5 | 55.1 |

| SN-MP (°) | 30.2 | 29.5 | 30.0 | 31.2 | 31.2 |

| AFH (mm) | 136.4 | 140.8 | 141.1 | 143.0 | 142.8 |

| PFH (mm) | 95.4 | 99.2 | 98.5 | 99.2 | 98.9 |

| FHR (%) | 70.2 | 70.5 | 69.8 | 69.4 | 69.3 |

| U1 to FH (°) | 116.0 | 127.6 | 121.8 | 126.5 | 127.5 |

| IMPA (°) | 96.6 | 86.7 | 82.1 | 72.5 | 76.2 |

| U1 to L1 (°) | 124.0 | 123.0 | 132.8 | 136.7 | 133.0 |

| MxOP to FH (°) | 14.0 | −3.5 | 1.5 | 2.2 | 1.1 |

| MnOP to FH (°) | 14.0 | 7.8 | −0.9 | −0.9 | 0.3 |

| UL to EL (mm) | 1.0 | −4.8 | −2.4 | −2.8 | −2.7 |

| LL to EL (mm) | 1.0 | −1.3 | 1.4 | 0.3 | −1.1 |

| NLA (°) | 100.0 | 99.5 | 91.6 | 92.7 | 92.8 |

| Z angle (°) | 75.0 | 85.7 | 81.0 | 83.1 | 85.9 |

| Variables | T1 (x, y, z) | T3 (x, y, z) |

|---|---|---|

| U1MP | (−1.95, −4.31, −78.07) | (−2.04, −3.66, −81.29) |

| L1MP | (−6.22, −6.41, −85.15) | (−1.82, −0.90, −79.89) |

| RU6CP (right) | (−31.94, 21.69, −79.64) | (−31.43, 22.41, −80.25) |

| LU6CP (left) | (26.86, 23.34, −79.75) | (25.86, 23.42, −81.27) |

| RL6CP (right) | (−27.92, 18.54, −80.58) | (−28.35, 20.14, −79.59) |

| LL6CP (left) | (17.50, 15.99, −82.42) | (22.63, 21.56, −79.98) |

| Point A | (−2.16, 3.21, −57.25) | (−1.03, 3.25, −58.82) |

| Point B | (−6.81, −2.83, −104.40) | (−4.98, −1.87, −103.55) |

| Pogonion | (−8.04, −5.77, −117.50) | (−6.13, −5.20, −119.91) |

| Menton | (−7.70, −1.36, −125.09) | (−5.46, 0.09, −126.68) |

| Gonion (right) | (−50.94, 67.55, −94.62) | (−49.93, 69.01, −94.76) |

| Gonion (left) | (43.92, 65.31, −91.65) | (44.47, 65.37, −93.14) |

| Stomion | (−2.69, −14.54, −77.29) | (−1.37, −14.40, −80.00) |

| UL | (−2.05, −19.23, −71.22) | (−0.84, −19.52, −72.61) |

| LL | (−3.41, −22.19, −84.05) | (−0.64, −20.06, −87.60) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Seo, Y.-J.; Park, J.H.; Chang, N.-Y.; Chae, J.-M. Non-Surgical Camouflage Treatment of a Skeletal Class III Patient with Anterior Open Bite and Asymmetry Using Orthodontic Miniscrews and Intermaxillary Elastics. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 4535. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13074535

Seo Y-J, Park JH, Chang N-Y, Chae J-M. Non-Surgical Camouflage Treatment of a Skeletal Class III Patient with Anterior Open Bite and Asymmetry Using Orthodontic Miniscrews and Intermaxillary Elastics. Applied Sciences. 2023; 13(7):4535. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13074535

Chicago/Turabian StyleSeo, Ye-Ji, Jae Hyun Park, Na-Young Chang, and Jong-Moon Chae. 2023. "Non-Surgical Camouflage Treatment of a Skeletal Class III Patient with Anterior Open Bite and Asymmetry Using Orthodontic Miniscrews and Intermaxillary Elastics" Applied Sciences 13, no. 7: 4535. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13074535

APA StyleSeo, Y.-J., Park, J. H., Chang, N.-Y., & Chae, J.-M. (2023). Non-Surgical Camouflage Treatment of a Skeletal Class III Patient with Anterior Open Bite and Asymmetry Using Orthodontic Miniscrews and Intermaxillary Elastics. Applied Sciences, 13(7), 4535. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13074535