Abstract

The main goal of this study is to analyze photobiomodulation therapy’s effectiveness on improving sports practice. Secondarily, the included studies were methodologically analyzed to verify their quality. A review and appraisal of literature found in Web of Science, ProQuest and Scopus databases was carried out. To evaluate the risk of bias of the included studies. The Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro) scale and PEDro Internal Validity Scale (IVS) checklists were used. The included randomized clinical trials were in English, conducted on humans and published since 2016. A total of 15 randomized clinical trials were included, 4 of which found an improvement in oxygen volume after an aerobic stress test, while 2 showed no change. Muscle damage decreased in five studies, however, in two of them muscle damage did not change. Blood lactate concentration decreased in two of the studies, while in three of them there was no difference. Muscle soreness was lower in three studies, however, in four of the articles no change was demonstrated. All selected studies were of good methodological quality. On the IVS, six RCTs had a high internal quality and nine of them moderate. Photobiomodulation therapy has a positive effect on sports performance. Scientific studies on the subject are limited and more research in this line is needed.

1. Introduction

Photobiomodulation (PBM) is a non-thermal treatment that uses sources of non-ionizing light, such as light-emitting diodes (LEDs), lasers and broad spectrum light in the visible to infrared portion of the spectrum. The use of PBM triggers reactions photophysically and photochemically in various tissues in the human body by interacting with chromophores [1].

The photoreceptors in the mitochondria are stimulated by light, which can trigger a stimulation or, contrarily, an inhibition of the cellular metabolism. The optimal doses are those that trigger therapeutic effects [2,3,4]. The PBM mechanism of action involves bioenergy, photochemistry and photobiology. Transcription factors and signaling pathways are activated when photons are absorbed by certain molecules within the neurons and the metabolic reaction speeds in the cells are changed. Additionally, the absorption of photons increases oxygen consumption which leads to greater activity in the mitochondria and oxidative phosphorylation. Therefore, there is additional adenosine triphosphate (ATP) manufactured, providing more energy for transduction in the neurons. The function of the brain is thus improved as blood flow to the brain is increased [2].

Within the realm of the possible therapeutic benefits of photobiomodulation, its effect on mitochondrial function is the best researched. In this regard, the mitochondrial electron transport chain complexes I, II, III and IV and succinate dehydrogenase have been shown to increase their activity. A greater level of ATP is seen through an increase in transmembrane protein complex IV, commonly referred to as the enzyme cytochrome C oxidase. Additionally, PBM activates transcription factors and signaling pathways which results in a greater gene expression related to the synthesis of proteins, migration and proliferation of cells, anti-inflammatory responses, antioxidant enzymes and antiapoptotic proteins [3].

Photobiomodulation therapy is commonly used in clinical practice to treat musculoskeletal disorders, with positive results shown in various clinical trials and systematic reviews [4]. However, widespread use of and strong scientific interest in the effects produced after the application of PBM in the field of sports performance also occur. The affirmative benefits of photobiomodulation on biological markers which relate to the reduction of oxidative stress, the modulation of inflammation and the damage to muscles have been shown in various studies [1].

Wasik et al. evaluated how peripheral blood cells, namely granulocytes, lymphocytes and erythrocytes, have their oxidative metabolism affected by the action of PBM. Samples of heparinized blood from fifteen participants were irradiated, with the results showing an increase in both the oxygen saturation and the partial pressure. Hence, the reactions induced photochemically in the aforementioned cells by PBM can improve the oxygen carrying capacity of the blood [5].

After strenuous exercise, elite athletes frequently suffer from muscle fatigue which is usually linked to oxidative muscle stress from the increased production of reactive oxygen species. This provokes a physical performance reduction and, possibly, injuries, hence the fastest and most effective healing treatment for the athlete is essential [6]. In sports performance, it was shown that the use of PBM before physical training could improve sports performance in top-grade athletes in addition to reducing the delay in muscle fatigue and preventing the anticipated rise in the level of blood lactate [5].

Participants, in a good state of health, and professional sports players have shown in various clinical research programs that when PBM is used before a training session the number of repetitions performed can be increased, the time to fatigue onset can be lengthened and the peak torque can be improved. Additionally, studies demonstrated that PBM can enhance gains in different areas of physical training abilities such as strength and cardiovascular training [5]. However, the specific effects that PBM produces in athletes and which benefits it can bring to different sports need to be clarified. The latest summary of research shows that the best effects of PBM therapy occur when the light is used before the exercise in direct contact with the skin using wavelengths from 655 to 950 nm. Furthermore, the majority of positive results happened with an energy dose ranging from 20 to 60 J for small muscular groups and 60 to 300 J for large muscular groups and maximal power output of 200 mW per diode [6,7,8,9].

Thus, a review of current scientific literature on PBM’s use and efficacy in sports as a whole and, in particular, its results in performance improvement and muscular recovery is the goal of the current study. The second objective will be to methodologically analyze the quality of the included studies.

2. Method

2.1. Design of the Study

A review of RCTs is the basis of this study. A methodology characteristic of a systematic review, including analyzing of the methodological quality of the selected RCTs, has been carried out. In addition, the PRISMA statement was followed, to methodologically increase the study’s quality.

2.2. Sources of Information and Search Strategy

The search of the literature took place in March, April and May 2022 using these sources of data: ProQuest, PubMed, Scopus and Web of Science (See Table 1).

Table 1.

Strategy followed to search the various sources of data.

The PICO strategy was used to formulate the study question and was based on the following elements:

- Population: Healthy adults over the age of 18.

- Intervention: Improvement of sports performance after the use of photobiomodulation.

- Comparison: Application or not of PBM therapy.

- Outcome: Effectiveness of PBM therapy on improving sports performance in healthy people.

2.2.1. PubMed

Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms were used for the PubMed search as well as key terms that were not available in MeSH such as “photobiomodulation”.

The keywords were “sport”, “exercise”, “endurance” and “blood samples”.

The Boolean operators were AND/OR.

The following parameters were used to limit the search strategy of this review: (i) text accessibility: free; (ii) type of article: RCTs; (iii) date of publication: 2017–2022; (iv) studies that have been carried out in humans; (v) language: English.

2.2.2. Web of Science (WoS)

The keywords “photobiomodulation”, “sport”, “exercise”, “endurance”, “performance” and “strength” were used in the WoS search.

The following parameters were used to limit the search strategy of this review: (i) text accessibility: free; (ii) type of article: RCTs; (iii) date of publication: 2017–2022; (iv) studies that have been carried out in humans; (v) language: English.

2.2.3. Scopus

The keywords “photobiomodulation”, “sport”, “exercise” and “endurance” were used in the Scopus search.

The following parameters were used to limit the search strategy of this review: (i) text accessibility: free; (ii) type of article: RCTs; (iii) date of publication: 2017–2022; (iv) studies that have been carried out in humans; (v) language: English.

2.2.4. ProQuest

The keywords “photobiomodulation”, “sport”, “exercise”, “endurance” and “strength” were used in the ProQuest search.

The following parameters were used to limit the search strategy of this review: (i) text accessibility: free; (ii) type of article: RCTs; (iii) date of publication: 2017–2022; (iv) studies that have been carried out in humans; (v) language: English.

2.3. Study Selection

Criteria for inclusion

- Publishing date: January 2017–May 2022.

- English language publication.

- Classified as RCTs.

- Access to the complete text available.

- Conducted in humans over the age of 18.

- Healthy individuals with no musculoskeletal injuries within at least the previous 3 months.

2.4. Exclusion Criteria

- Not meeting the inclusion criteria.

- Repeated in the databases.

- Lack of implementation of PBM therapy.

- No results shown or no interpretation of the data.

2.5. Article Selection

The review’s goal was to concentrate on photobiomodulation therapy (PBMT) in sports in general.

2.6. Evaluation of the RCTs’ Methodological Quality

The translated and adapted to Spanish PEDro scale was used to assess the RCTs’ methodological quality by assessing the validity of the articles [10]. By means of 11 items, this scale examines the internal and external validity of a study. Each fulfilled item adds 1 point to the total score, excluding the first, hence the overall rating ranges from 0 to 10 points [10].

Subsequently, the evaluation of the internal validity of the RCTs was carried out using the Internal Validity Scale (IVS). The score includes the items from the PEDro scale that are selected to be the most representative for internal validity. The selected values are 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9 [10].

2.7. RCTs’ Qualitative Synthesis

The acquired score of each study shows its quality, therefore those studies presenting an excellent methodological quality acquired nine to ten points; those with six to eight points have a good methodological quality; those with four to five points have a normal quality and, lastly, those below four points have a poor methodological quality [10].

2.8. Management of the Identified Literature

The bibliographical references have been managed using Mendeley software.

3. Results

The results obtained from the included studies are specified below.

3.1. Study Selection

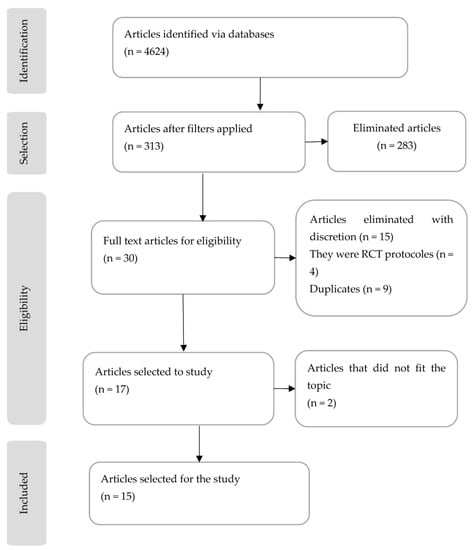

The searches performed in the 4 databases showed a total of 4624 articles: PubMed studies, Web of Science studies, Scopus studies and ProQuest studies.

All studies which did not follow the inclusion criteria were deleted and the titles and summaries of the found articles were read.

Finally, 15 randomized clinical trials were included in this review. The selection process for the articles is reflected in Figure 1 by means of a flow diagram in accordance with the guidelines and criteria set out in the PRISMA 2009 statement.

Figure 1.

Flow chart outlining the process for the selection and exclusion of the studies following the PRISMA statement.

3.2. Methodological Quality Evaluation

Subsequent to selecting the articles, an evaluation of the methodological quality was implemented using the two scales aforementioned for the randomized clinical trials. The results are provided in Table 2 and Table 3.

Table 2.

The RCTs’ quality assessed methodologically using the PEDro scale.

Table 3.

RCTs’ internal validity.

3.3. Study Characteristics

Table 4 explains the main characteristics of the included studies, including the type of study, the sample size, the intervention performed and the results obtained.

Table 4.

Breakdown of the main characteristics of studies in the review.

The characteristics and interventions of all included studies in this literature review are discussed below.

In the study by Marchi T. et al., 2017 [11] the groups performed a test consisting of five sets of ten repetitions of concentric and eccentric contractions of the elbow flexors with a 30 s rest between sets. The volunteers were encouraged to carry out the exercise using as much force as possible.

In the study by Miranda E. et al., 2018 [12], sixty-seven healthy volunteers followed a cardiovascular training protocol three times per week on a treadmill for twelve weeks. The control group received placebo treatment prior and subsequent to the sessions of training, while the group being experimented on received treatment before, after or before and after the training sessions.

Beltrame T. et al., 2018 [13] completed a study in which they investigated the effects of PBMT on cardiovascular exercise. Participants undertook a test on an ergometric bicycle to see if there were any significant changes in the level of oxygen consumption or in the level of blood lactate.

In the study by Follmer B. et al., 2018 [14], the muscle fatigue generated and the time to exhaustion were measured after strength training with either PBMT or placebo received before and after the sessions.

Peserico C. et al., 2019 [15] had the objective of studying running training’s influence, in conjunction with PBMT, on stamina and muscle pain over a period of eight weeks of training.

De Marchi T. et al., 2019 [16] investigated PBMT’s effects on the performance and recovery in indoor footballers in two games in an environment that was not controlled.

In the study by Da Rosa Orsatto L. et al., 2019 [17], PBMT’s effects on damage to muscle and fatigue in judo athletes were explored. Sixteen male judo athletes were submitted to the countermovement jump (CMJ) test prior to applying PBMT or a placebo.

In the study by Tomazi S. et al., 2019 [1], a controlled (ergo-spirometry) intense progressive running test was carried out in top-level male football players in conjunction with PBMT or placebo to observe whether significant differences existed in the performance and recovery of the athletes.

Machado C. et al., 2020 [18] researched whether PBMT along with a static magnetic field improved the recovery and muscle damage in thirty healthy males after an eccentric strength test measured with an isokinetic dynamometer.

In the study by Leal Junior E. et al., 2020 [19], sixty untrained men were divided into groups to carry out eccentric strength tests after the application, or not, of PBMT combined with static magnetic fields or not, measured with an isokinetic dynamometer.

De Paiva P. et al., 2020 [20] used PBMT in combination with static magnetic fields, along with placebo therapy as a control, in sixty healthy men while using a treadmill to carry out three sessions weekly for twelve weeks.

The study by Dutra Y. et al., 2021 [21] investigated the effects, in thirteen healthy untrained men, of PBMT applied 30 min to 6 h before carrying out a test on a stationary bicycle, to see if changes of a significant nature were seen between the control and experimental groups.

In the study by Santos I. et al., 2020 [6], thirteen amateur indoor football players carried out three different tests, namely the countermovement jump (CMJ) test, the Illinois Agility test and the level 1 intermittent Yoyo recovery test. The experimental group received PBMT to observe whether there were changes in the performance of these players as regards the group used for control.

Lanferdini F. et al., 2021 [22] used a 3km run to research the effects of PBMT in twenty male endurance athletes. The metabolic effects and the perceived effort rating were compared between the experimental group which had been treated with PBMT and the control group which had been given a placebo treatment.

Lastly, Machado A. et al., 2022 [23] carried out a study to compare a group treated with PBMT and a control group treated with a placebo in a series of tests that combined sprints and squats to observe how performance improvement and recovery in healthy people were affected.

3.4. Effects of PBMT on Sports Performance

The studies were selected with the aim of determining the efficacy of photobiomodulation therapy application on sports performance in healthy people with no previous injury or pathology in at least the three-month period prior to the study.

The following sections present the results from the articles on the analyzed variables:

3.4.1. Muscle Damage

There were no differences in muscle damage in the groups after a training session in the studies by Da Rosa Orsatto L. et al., 2019 [17] and Dutra Y. et al., 2021 [21].

On the contrary, muscle damage, after a training session, was lower in people who had used PBMT in the studies by De Marchi T. et al., 2017 [11], De Marchi T. et al., 2019 [16], Tomazoni S. et al., 2019 [1], Machado C. et al., 2020 [18], Leal Junior E. et al., 2020 [19].

3.4.2. Oxygen Volume

Oxygen volume (VO2) did not improve in participants after a training session with PBMT applied before or after exercise according to Beltrame T. et al., 2018 [13] and Dutra Y. et al., 2021 [21].

On the other hand, improvements in VO2 were found in the studies by Miranda E. et al., 2018 [12], Tomazoni S. et al., 2019 [1], De Paiva P. et al., 2020 [20] and Lanferdini F. et al., 2021 [22].

3.4.3. Blood Lactate Concentration

In the studies by Beltrame T. et al., 2018 [13], Dutra Y. et al., 2021 [21], Santos I. et al., 2020 [6], there were no changes of any significance found in the blood lactate concentration in the experimental group with regard to the control group after the training session.

On the contrary, in the studies by De Marchi T. et al., 2019 [16] and Machado C. et al., 2020 [19], significant changes were found in the blood lactate concentration of the participants after a training session. The participants who received the PBMT intervention had a lower concentration of lactate in their blood compared to the placebo group.

3.4.4. Muscle Pain

Participants in the group used for control purposes and in the experimental group, in the studies by De Marchi T. et al., 2019 [16], Da Rosa Orsatto L. et al., 2019 [17], Santos I. et al., 2020 [6] and Machado A. et al., 2022 [23], had no significant differences in muscle pain after a training session.

However, the lessening of pain in muscles showed differences of a significant nature in those participants who received PBMT as regards the placebo group in the studies by Peserico C. et al., 2019 [15], Machado C. et al., 2020 [18] and Leal Junior E. et al., 2020 [19].

4. Discussion

The aim of this literature review was to examine the current scientific evidence on the efficacy of PBMT application as a treatment in sport and sports performance. The search strategy resulted in 15 articles being selected, all of which were randomized clinical trials.

In 10 of the studies, significant differences were observed in at least one of the variables related to sports performance in the group which had received PBMT before or after training when compared to the group that had received placebo.

The study interventions can be divided into three different groups. The first group is formed by the intervention being a cardiovascular exercise test, the second group is based on the participants carrying out a strength exercise and in the third the participants had to combine cardiovascular and strength training in the session.

4.1. Cardiovascular Training

In five out of the eight studies in which the intervention is cardiovascular training, an increase in running performance in the group that received PBMT before the test is observed. This increase is due to better oxygen consumption which leads to a delay in time to exhaustion [1,12,16,20,22]. In one of the studies, there was a moderate change in pain reduction after a 5km run in the group that had received PBMT compared to the placebo group [15].

In two studies, in which the therapy was applied 6.5 h before the test, no significant changes were found between groups. Consequently, the lack of results may be due to the time frame for the application of the therapy and the start of the protocol [13,21].

4.2. Strength Training

Of the five studies in which the intervention consisted of a strength test with concentric and eccentric exercises measured using an isokinetic dynamometer, four were found to show significant changes in the group in which PBMT was used compared to the placebo group. In three of them, muscle damage after exercise was reduced [11,18,19] and, in the other, fatigue and time to exhaustion were observed to decrease [14].

In the study in which no significant differences were found in muscle damage between the experimental and control groups, different PBMT parameters were observed to reduce fatigue. Hence, future studies need to clarify what the appropriate parameters are in order to increase the quality of PBMT [17].

4.3. Combined Cardiovascular and Strength Training

Among the two studies in which the intervention was a combination of cardiovascular and strength exercise tests, neither demonstrated the effectiveness of PBMT, applied before or after exercise, for muscle recovery in high-intensity cardiovascular exercise [6,18].

However, one of the studies showed that muscle recovery is greater after strength training in the group that received PBMT when compared to the placebo group [18].

4.4. Effects and Benefits of PBMT on Sports Performance

Studies show that PBMT helps improve sports performance and accelerates recovery after exercise, in both strength and cardiovascular training, so it is a technique that can be used in numerous sports disciplines [20].

4.5. Characteristics PBMT Must Have to Improve Sports Performance

There are still many open questions about the application of PBMT in sports, but from all the studies reviewed the best results regarding muscle damage are obtained with a dose of between 10 and 60 Joules, and for a greater effect the therapy should be performed before and after exercise [8].

4.6. Strengths and Weaknesses of the Study

Some strengths should be mentioned. Good methodological quality in the clinical trials was ensured by the use of scales. The randomized clinical trials that were collected in this review were of high quality, and hence so were the results obtained. This study highlights the considerable lack of research to illuminate and improve this field of therapy. The demographic characteristics of the study samples were homogeneous (healthy people aged between 20 and 35 with no musculoskeletal injury at least three months prior to the intervention). However, some weaknesses must be acknowledged. There was a lack of scientific information on PBMT in sports. In some studies, the samples contained a low number of participants. The interventions in various studies were of short duration, with a low number of training sessions. The majority of the randomized clinical trial samples were healthy people but not top-level athletes, which could have interfered with the results.

4.7. Methodological Quality of the Obtained Results

The methodological quality of the studies was performed using two scales: the PEDro scale [10] and the IVS for randomized clinical trials.

In this literature review, 15 articles were selected, all randomized clinical trials, all having a good quality on the PEDro scale [10] and with nine of them obtaining a moderate validity and six a high validity on the IVS.

4.8. Future Research

After analyzing the results, it is clear that there is a scarcity of scientific evidence on this subject. Consequently, different lines of research are proposed:

- Implementation of RCTs to clarify PBM parameters such as the analysis of the optimal wavelengths, the optimal times and whether therapy should be performed before or after exercise.

- Implementation of RCT with samples from top-level athletes to see if there are differences from healthy untrained people.

- The evaluated PBM effects are combined with the effects of physical activity on biomechanical and fluid properties of blood and blood cells, such as erythrocyte deformability and aggregation, change in the concentration of basic plasma components (fibrinogen, albumins, globulins, testosterone, etc.), changes in blood flow (through vasodilatation and change in overall blood viscosity) changes in blood volume, changes in the endothelial cells of the vascular walls, changes in blood pressure, changes as a result of tissue hypoxia, interactions and different hemorheological changes. The multiple hemorheological, physiological and PBM effects during physical activity and their interconnectedness and strength make their differentiation very difficult. Hence, separating the PBM effect and pure physiological effects of applied physical activities would be of interest [24].

- Finally, other parameters such as pain, pain pressure threshold, elastic properties of tissue, circadian variation of blood pressure, quality of life and psychological factors should be further studied in athletes after a PBM intervention, as they have been shown to be improved after a whole-body PBM treatment in populations suffering from chronic pain [25,26,27].

5. Practical Applications

Current scientific literature shows that the application of photobiomodulation therapy before and/or after exercise seems effective for sports performance in both strength training and cardiovascular exercise training. This is because it favors the reduction of muscle damage, decreases the concentration of lactate in the blood, increases the volume of oxygen and decreases muscle pain after exercise, all of which lead to an improvement in sports performance and therefore better results in competition.

Based on our results, the application of PBMT as part of training in athletes may improve results and accelerate the recovery process, thus increasing their sports performance.

6. Conclusions

The effects of photobiomodulation therapy seem to help in the improvement of sports performance by increasing the volume of oxygen, reducing muscle damage, lowering the concentration of lactate in the blood and reducing muscle pain after exercise. However, because of the lack of studies in this line there is no certainty about the effect of photobiomodulation on sports performance and more studies are necessary to shed light in this regard.

The quality of the selected studies on photobiomodulation therapy in sports performance is good. The 15 selected randomized clinical trials have a good assessment of methodological quality on the PEDro scale, with 9 of them having a moderate IVS score and 6 of them high. The amount of scientific evidence regarding the optimal parameters for photobiomodulation therapy is limited, hence it must be clarified by new lines of research in this field of therapy in sports and more studies in this line are needed.

Author Contributions

Authors Contributions: Study conception: S.N.-L. and A.G.-M., design: S.N.-L. and A.G.-M., acquisition of data: A.G.-M., analysis and interpretation of data: S.N.-L., A.G.-M., M.C.-C., M-A.-G, D.H.-H., J.J.P.-M. and D.A.-N.; drafting of manuscript, S.N.-L., A.G.-M., M.C.-C., M-A.-G, D.H.-H., J.J.P.-M., D.A.-N. and L.P.; critical revision, S.N.-L., A.G.-M., M.C.-C., M.A.-G., D.H.-H., J.J.P.-M., D.A.-N. and L.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study has been partially funded by the University Chair in Clinical Psychoneuroimmunology (University of Granada and PNI Europe).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data associated with this study are present in the paper. All requests for other materials will be reviewed by the corresponding author to verify whether the request is subject to any intellectual property or confidentiality obligations.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Tomazoni, S.S.; Machado, C.D.S.M.; De Marchi, T.; Casalechi, H.L.; Bjordal, J.M.; Carvalho, P.D.T.C.D.; Leal-Junior, E.C.P. Infrared Low-Level Laser Therapy (Photobiomodulation Therapy) before Intense Progressive Running Test of High-Level Soccer Players: Effects on Functional, Muscle Damage, Inflammatory, and Oxidative Stress Markers—A Randomized Controlled Trial. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 6239058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, A.S.; Lee, T.L.; Yeung, M.K.; Hamblin, M.R. Photobiomodulation improves the frontal cognitive function of older adults. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2019, 34, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zomorrodi, R.; Loheswaran, G.; Pushparaj, A.; Lim, L. Pulsed Near Infrared Transcranial and Intranasal Photobiomodulation Significantly Modulates Neural Oscillations: A pilot exploratory study. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 6309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Souza Guimarães, L.; Costa, L.D.C.M.; Araujo, A.C.; Nascimento, D.P.; Medeiros, F.C.; Avanzi, M.A.; Leal-Junior, E.C.P.; Costa, L.O.P.; Tomazoni, S.S. Photobiomodulation therapy is not better than placebo in patients with chronic nonspecific low back pain: A randomised placebo-controlled trial. Pain 2021, 162, 1612–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Paiva, P.R.V.; Casalechi, H.L.; Tomazoni, S.S.; Machado, C.D.S.M.; Miranda, E.F.; Ribeiro, N.F.; Pereira, A.L.; da Costa, A.S.; Dias, L.B.; Souza, B.C.G.; et al. Effects of photobiomodulation therapy in aerobic endurance training and detraining in humans: Protocol for a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Medicine 2019, 98, e15317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, I.A.D.; Lemos, M.D.P.; Coelho, V.H.M.; Zagatto, A.M.; Marocolo, M.; Soares, R.N.; Barbosa Neto, O.; Mota, G.R. Acute Photobiomodulation Does Not Influence Specific High-Intensity and Intermittent Performance in Female Futsal Players. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rampazo, É.P.; de Andrade, A.L.M.; da Silva, V.R.; Back, C.G.N.; Liebano, R.E. Photobiomodulation therapy and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation on chronic neck pain patients: Study protocol clinical trial (SPIRIT Compliant). Medicine 2020, 99, e19191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ailioaie, L.M.; Litscher, G. Photobiomodulation and Sports: Results of a Narrative Review. Life 2021, 11, 1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanin, A.A.; Verhagen, E.; Barboza, S.D.; Pena Costa, L.O.; Leal-Junior, C.P. Photobiomodulation therapy for the improvement of muscular performance and reduction of muscular fatigue associated with exercise in healthy people: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lasers Med. Sci. 2018, 33, 181–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, C.; Sherrington, C.; Moseley, A.; Elkins, M.; Herbert, R. Reliability of the PEDro scale for rating quality of randomized controlled trials. Phys. Ther. 2003, 83, 713–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Marchi, T.; Schmitt, V.M.; Machado, G.P.; de Sene, J.S.; de Col, C.D.; Tairova, O.; Salvador, M.; Leal-Junior, E.C.P. Does photobiomodulation therapy is better than cryotherapy in muscle recovery after a high-intensity exercise? A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Lasers Med. Sci. 2017, 32, 429–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, E.F.; Tomazoni, S.S.; de Paiva, P.R.V.; Pinto, H.D.; Smith, D.; Santos, L.A.; de Tarso Camillo de Carvalho, P.; Leal-Junior, E.C.P. When is the best moment to apply photobiomodulation therapy (PBMT) when associated to a treadmill endurance-training program? A randomized, triple-blinded, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Lasers Med. Sci. 2018, 33, 719–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltrame, T.; Ferraresi, C.; Parizotto, N.A.; Bagnato, V.S.; Hughson, R.L. Light-emitting diode therapy (photobiomodulation) effects on oxygen uptake and cardiac output dynamics during moderate exercise transitions: A randomized, crossover, double-blind, and placebo-controlled study. Lasers Med. Sci. 2018, 33, 1065–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Follmer, B.; Dellagrana, R.A.; Rossato, M.; Sakugawa, R.L.; Diefenthaeler, F. Photobiomodulation therapy is beneficial in reducing muscle fatigue in Brazilian jiu- jitsu athletes and physically active men. Sport Sci. Health 2018, 14, 685–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peserico, C.S.; Zagatto, A.M.; MacHado, F.A. Effects of endurance running training associated with photobiomodulation on 5-km performance and muscle soreness: A randomized placebo-controlled controlled trial. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Marchi, T.; Leal-Junior, E.C.P.; Lando, K.C.; Cimadon, F.; Vanin, A.A.; da Rosa, D.P.; Salvador, M. Photobiomodulation therapy before futsal matches improves the staying time of athletes in the court and accelerates post-exercise recovery. Lasers Med. Sci. 2019, 34, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Rosa Orssatto, L.B.; Detanico, D.; Kons, R.L.; Sakugawa, R.L.; da Silva, J.N.; Diefenthaeler, F. Photobiomodulation therapy does not attenuate fatigue and muscle damage in judo athletes: A randomized, triple-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, C.D.S.M.; Casalechi, H.L.; Vanin, A.A.; de Azevedo, J.B.; de Carvalho, P.D.T.C.; Leal-Junior, E.C.P. Does photobiomodulation therapy combined to static magnetic field (PBMT-sMF) promote ergogenic effects even when the exercised muscle group is not irradiated? A randomized, triple-blind, placebo-controlled trial. BMC Sport. Sci. Med. Rehabil. 2020, 12, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal-Junior, E.C.P.; de Oliveira, M.F.D.; Joensen, J.; Stausholm, M.B.; Bjordal, J.M.; Tomazoni, S.S. What is the optimal time-response window for the use of photobiomodulation therapy combined with static magnetic field (PBMT-sMF) for the improvement of exercise performance and recovery, and for how long the effects last? A randomized, triple-blinded, placebo-controlled trial. BMC Sport. Sci. Med. Rehabil. 2020, 12, 64. [Google Scholar]

- De Paiva, P.R.V.; Casalechi, H.L.; Tomazoni, S.S.; Machado, C.D.S.M.; Ribeiro, N.F.; Pereira, A.L.; De Oliveira, M.F.D.; Alves, M.N.D.S.; Dos Santos, M.C.; Takara, I.E.T.; et al. Does the combination of photobiomodulation therapy (PBMT) and static magnetic fields (sMF) potentiate the effects of aerobic endurance training and decrease the loss of performance during detraining? A randomised, triple-blinded, placebo-controlled trial. BMC Sport. Sci. Med. Rehabil. 2020, 12, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutra, Y.M.; Claus, G.M.; Malta, E.D.S.; Seda, D.M.d.F.; Zago, A.S.; Campos, E.Z.; Ferraresi, C.; Zagatto, A.M. Photobiomodulation 30 min or 6 h Prior to Cycling Does Not Alter Resting Blood Flow Velocity, Exercise-Induced Physiological Responses or Time to Exhaustion in Healthy Men. Front. Physiol. 2021, 11, 607302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanferdini, F.J.; Silva, E.S.; Boeno, F.P.; Sonda, F.C.; Rosa, R.G.; Quevedo, R.; Baroni, B.M.; Reischak-Oliveira, A.; Vaz, M.A.; Peyré-Tartaruga, L.A. Effect of photobiomodulation therapy on performance and running economy in runners: A randomized double-blinded placebo-controlled trial. J. Sport. Sci. 2021, 39, 1348–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machado, A.F.; Leal-Junior, E.C.P.; Batista, N.P.; Espinoza, R.M.; Hidalgo, R.B.; Carvalho, F.A.; Micheletti, J.K.; Vanderlei, F.M.; Pastre, C.M. Photobiomodulation therapy applied during an exercise-training program does not promote additional effects in trained individuals: A randomized placebo-controlled trial. Braz. J. Phys. Ther. 2022, 26, 100388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivanov, I. Hemorheological Alterations and Physical Activity. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 10374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Ledesma, S.; Carroll, J.; Burton, P.; Ana, G.-M. Short-Term Effects of Whole-Body Photobiomodulation on Pain, Quality of Life and Psychological Factors in a Population Suffering from Fibromyalgia: A Triple-Blinded Randomised Clinical Trial. Pain Ther. 2022, 12, 225–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Ledesma, S.; Carroll, J.; González-Muñoz, A.; Pruimboom, L.; Burton, P. Changes in Circadian Variations in Blood Pressure, Pain Pressure Threshold and the Elasticity of Tissue after a Whole-Body Photobiomodulation Treatment in Patients with Fibromyalgia: A Tripled-Blinded Randomized Clinical Trial. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Ledesma, S.; Gonzalez-Muñoz, A.; Carroll, J.; Burton, P. Short- and Long-Term Effects of Whole-Body Photobiomodulation on Pain, Functionality, Tissue Quality, Central Sensitisation and Psychological Factors in a Population Suffering from Fibromyalgia: Protocol for a Triple-Blinded Randomised Clinical Trial. Ther. Adv. Chronic Dis. 2022, 13, 204062232210780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).