Analysis of the Consistency of Prerequisites and Learning Outcomes of Educational Programme Courses by Using the Ontological Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Works

- ontological approach of the curriculum (curriculum or syllabus);

- ontological approach of the context of the implementation of the curriculum—educational organisation and educational process;

- extraction and structuring of educational content using semantic analysis.

- Rare use of inference (reasoning) capabilities and tools for executing smart documents for DL Query, SPARQL, as well as the description of inference rules of the SWRL language. Meanwhile, these elements are the greatest advantage of semantic technologies compared to all other points of view.

- The developed models only reflect the obvious structural connections between the elements of the educational programme and the context of its implementation, ignoring the relationship between the concepts lying in the domain of time.

- Neglecting the principle of object-oriented design when designing ontological models. When designing the class structure, it is advisable to use the top-down design principle and assign the most common classes in the hierarchy, additionally creating derived classes through the inheritance mechanism. Class properties—i.e., object properties and data properties—should also be defined at the highest possible level, specifying them in derived classes where necessary.

3. Research Questions

- Q1.

- Is it possible to build, using an object-oriented approach, a detailed ontological model of an educational programme that combines courses, skills, and training periods?

- Q2.

- Is it possible to automate the analysis of the consistency of course prerequisites and learning outcomes of an educational programme and its ontological model with the use of appropriate software?

- Q3.

- Can the developed ontological model of the educational programme be easily integrated with the Learning Management Systems software?

4. Methodologies Used

- The “transparency” of the data model, which provides for its expansion by adding new concepts and relationships throughout the system’s life cycle.

- The ability to model complex relationships and the use of logical inference.

- The usage of agreed (shared by all) terminology with precisely defined semantics.

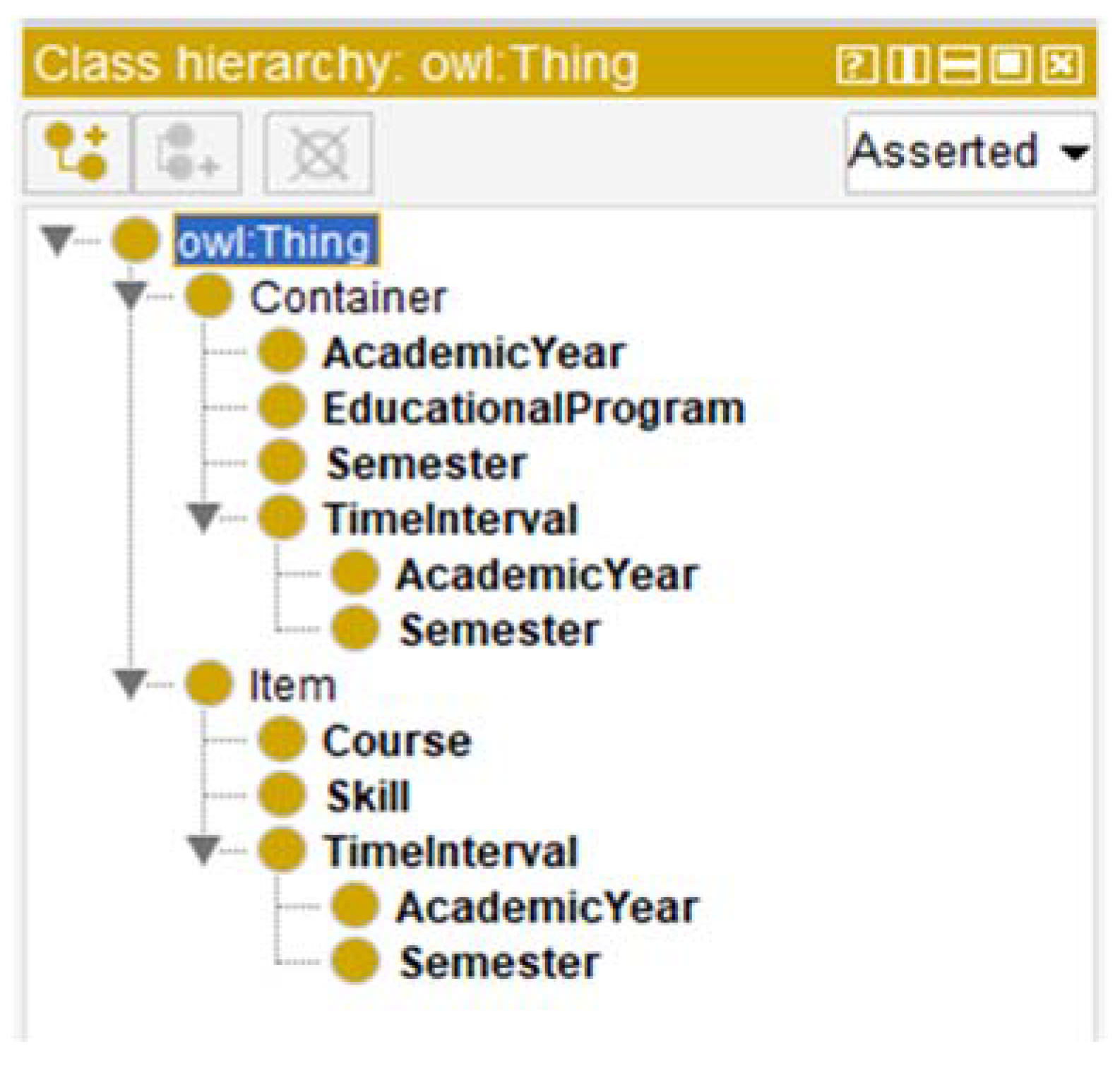

5. Development of an Ontological Model of an Educational Programme

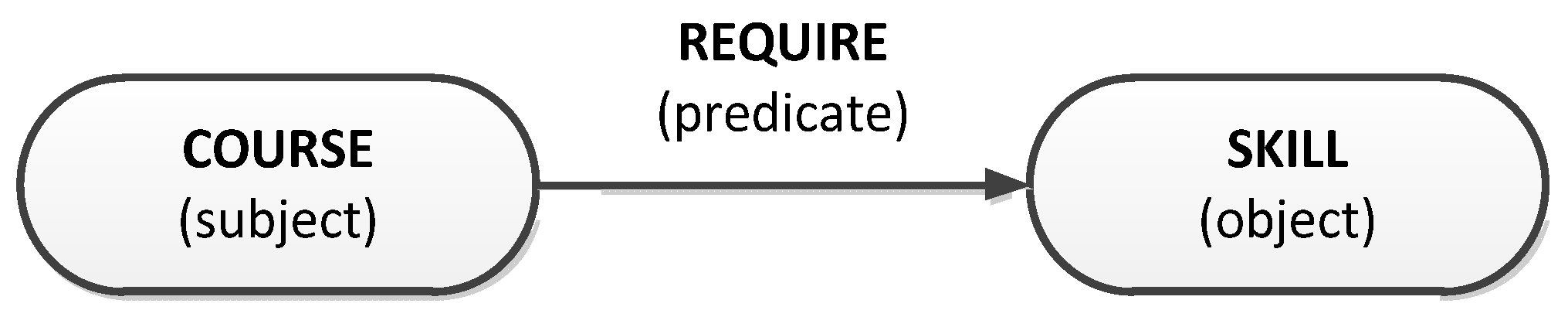

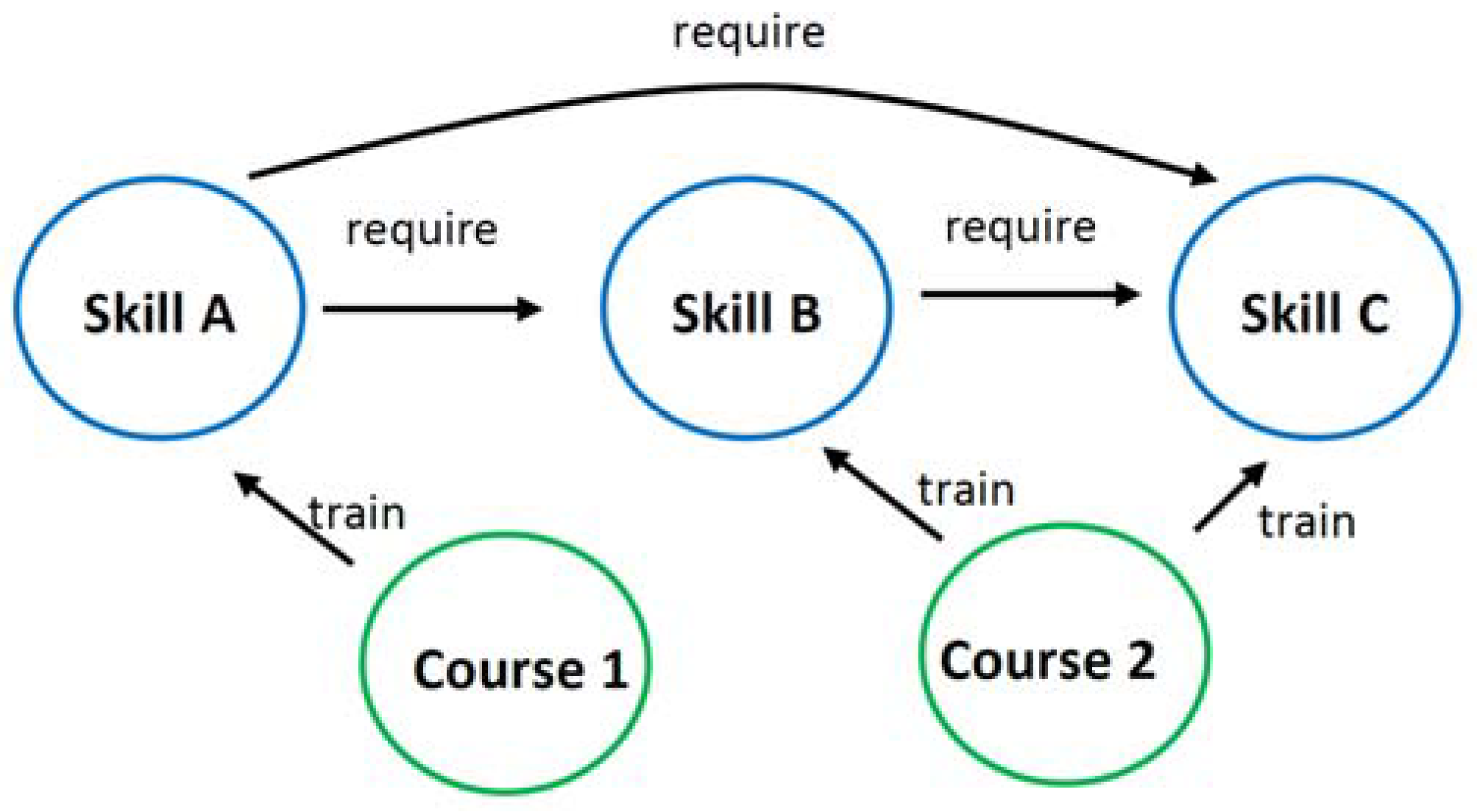

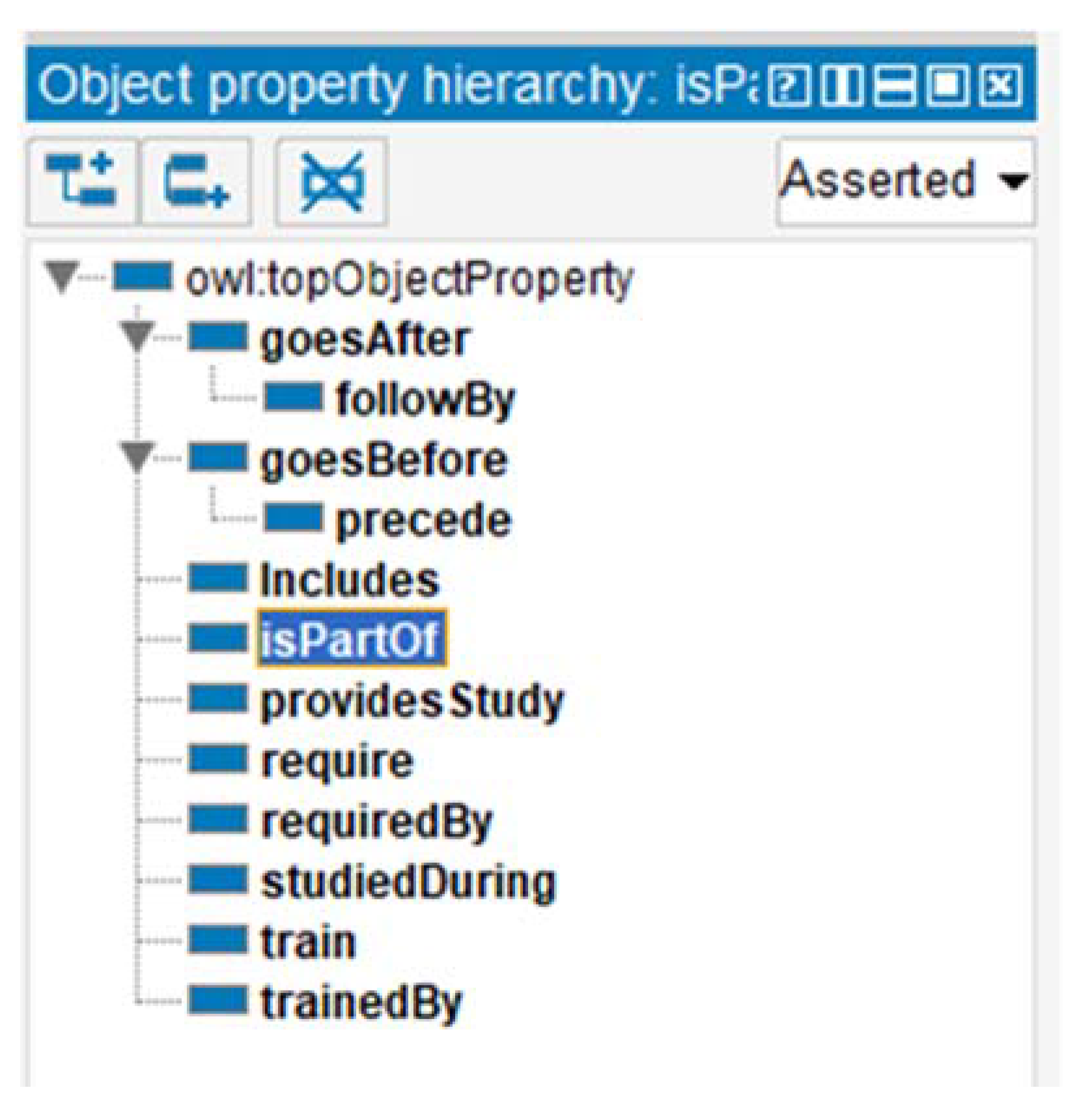

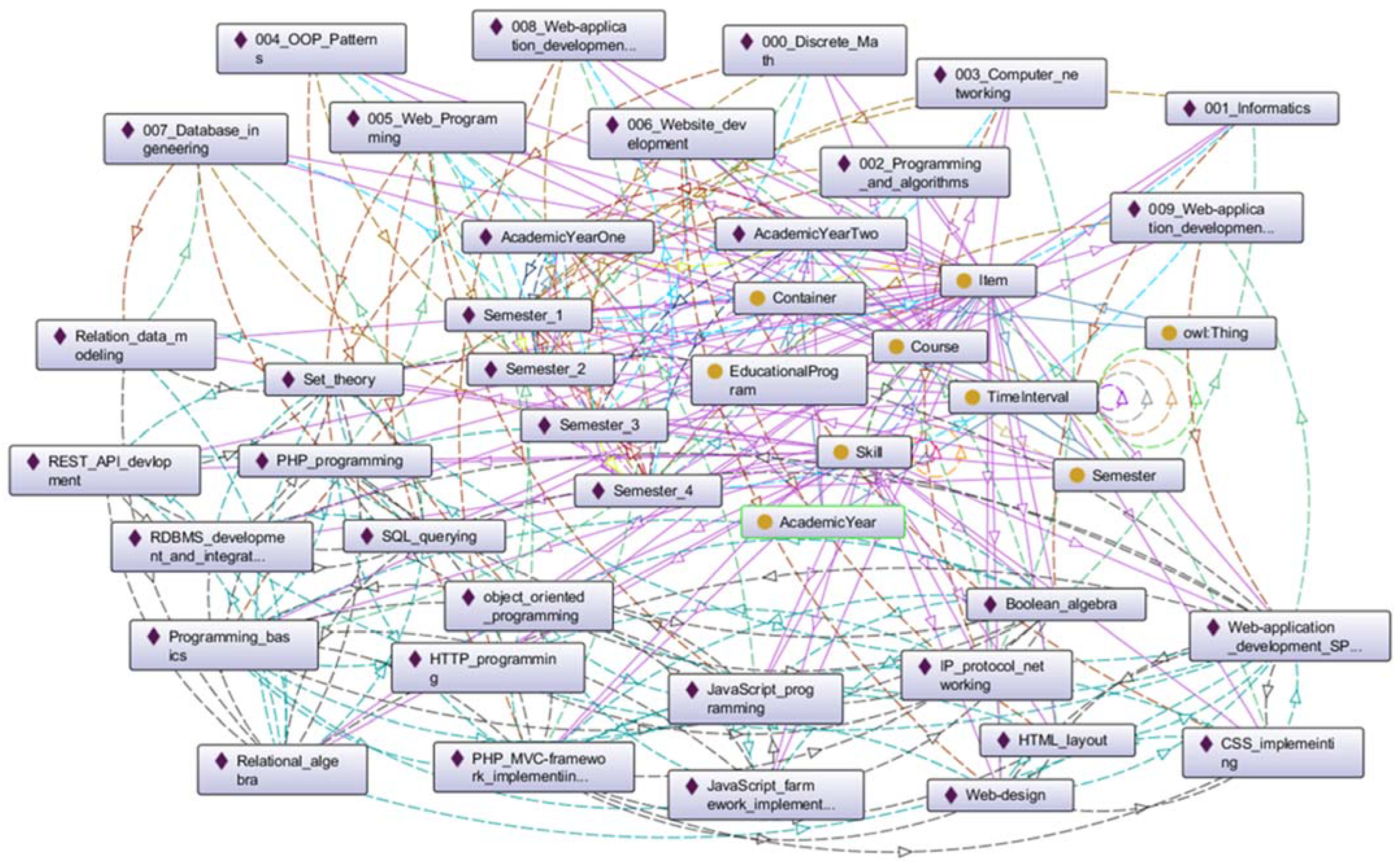

5.1. Skills and Courses Model

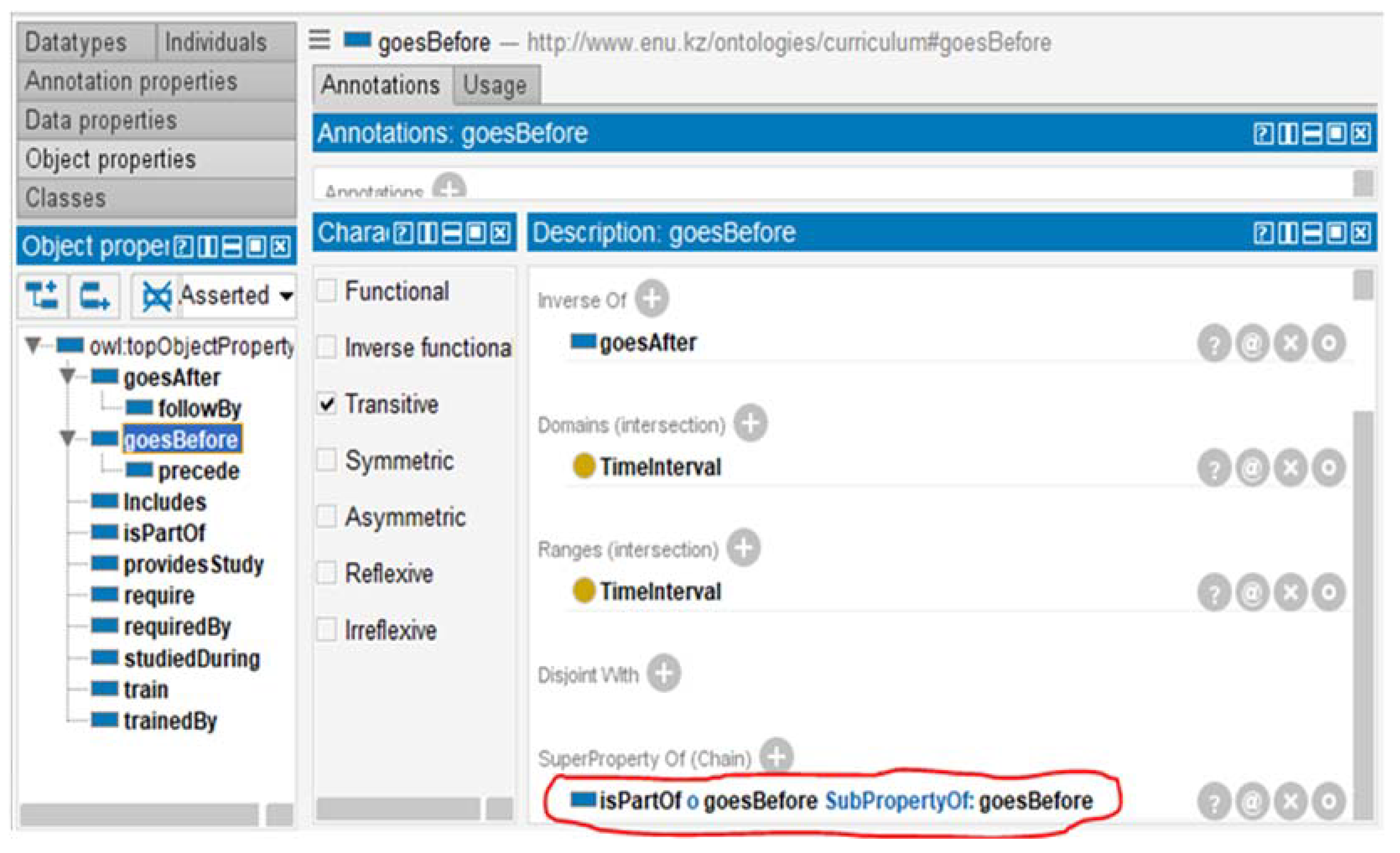

5.2. Model of Training Periods

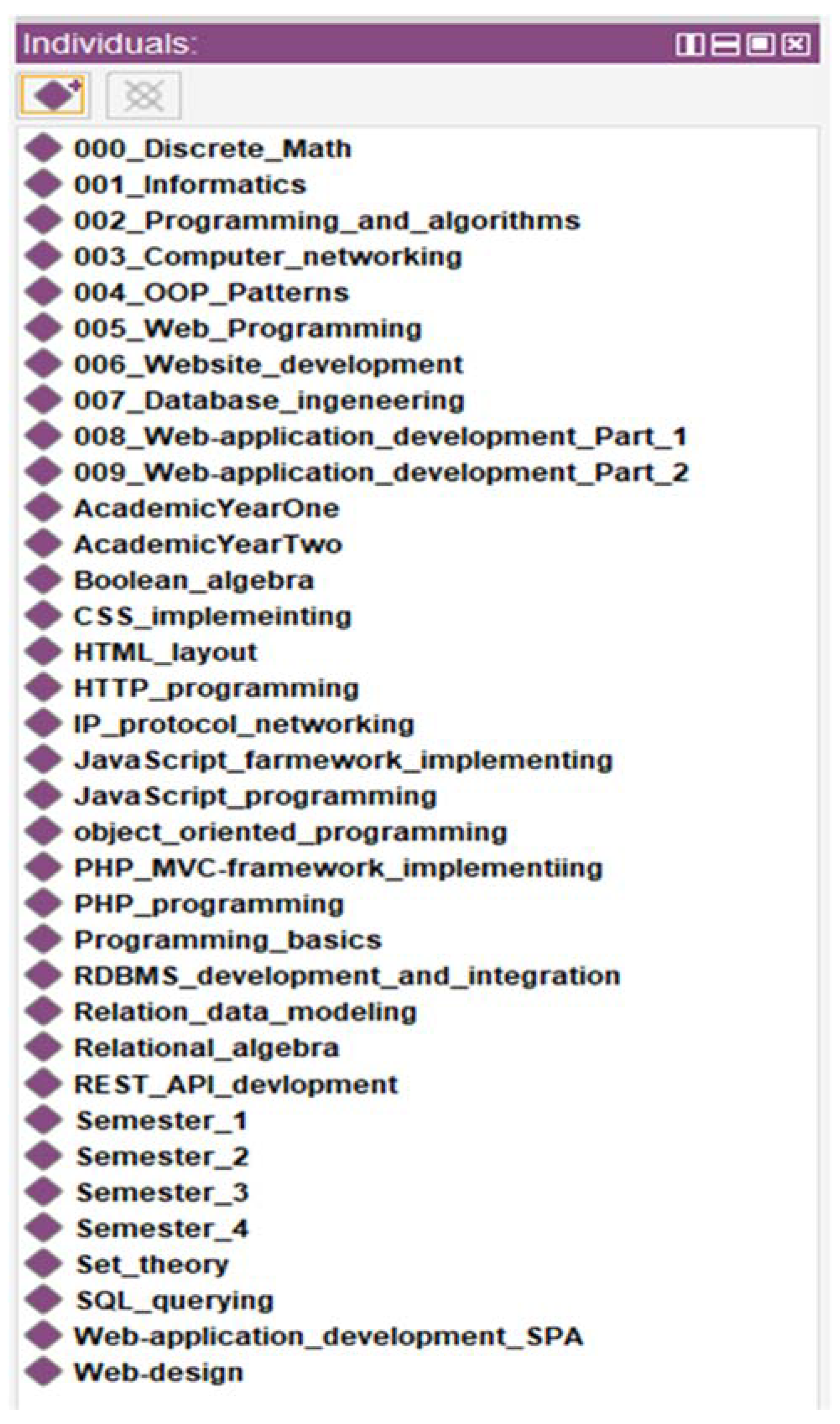

5.3. An Example of Ontological Model Developed

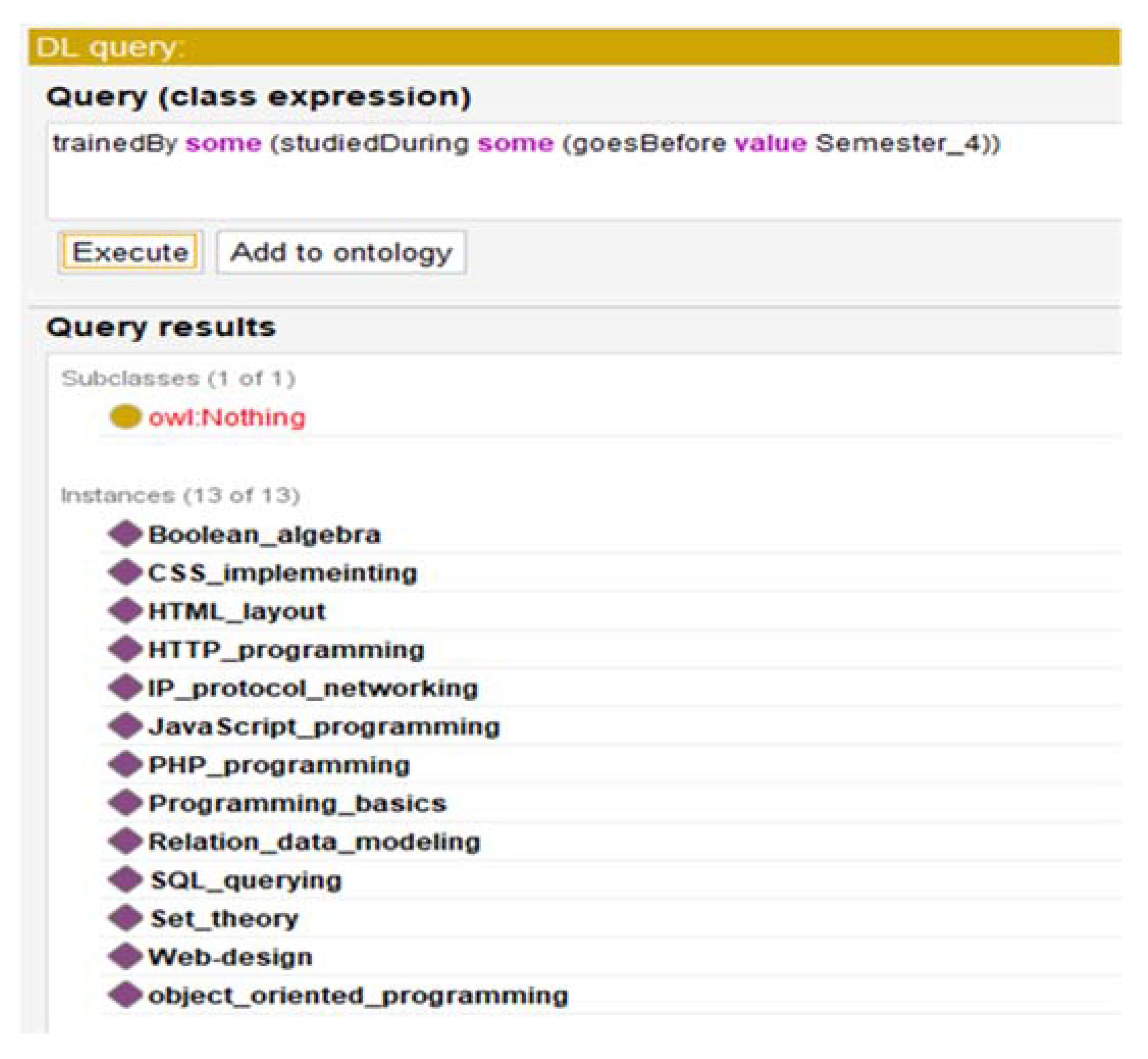

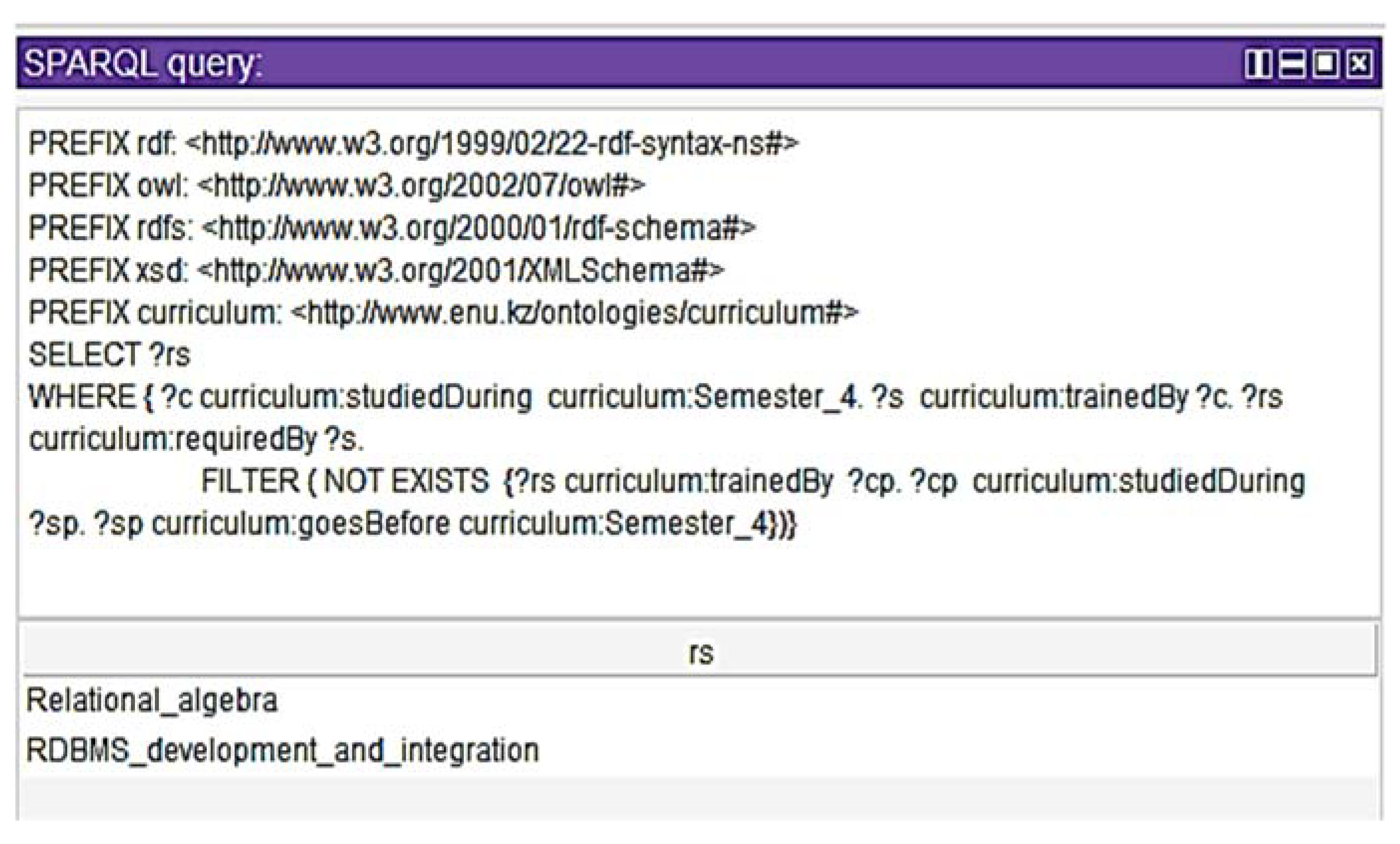

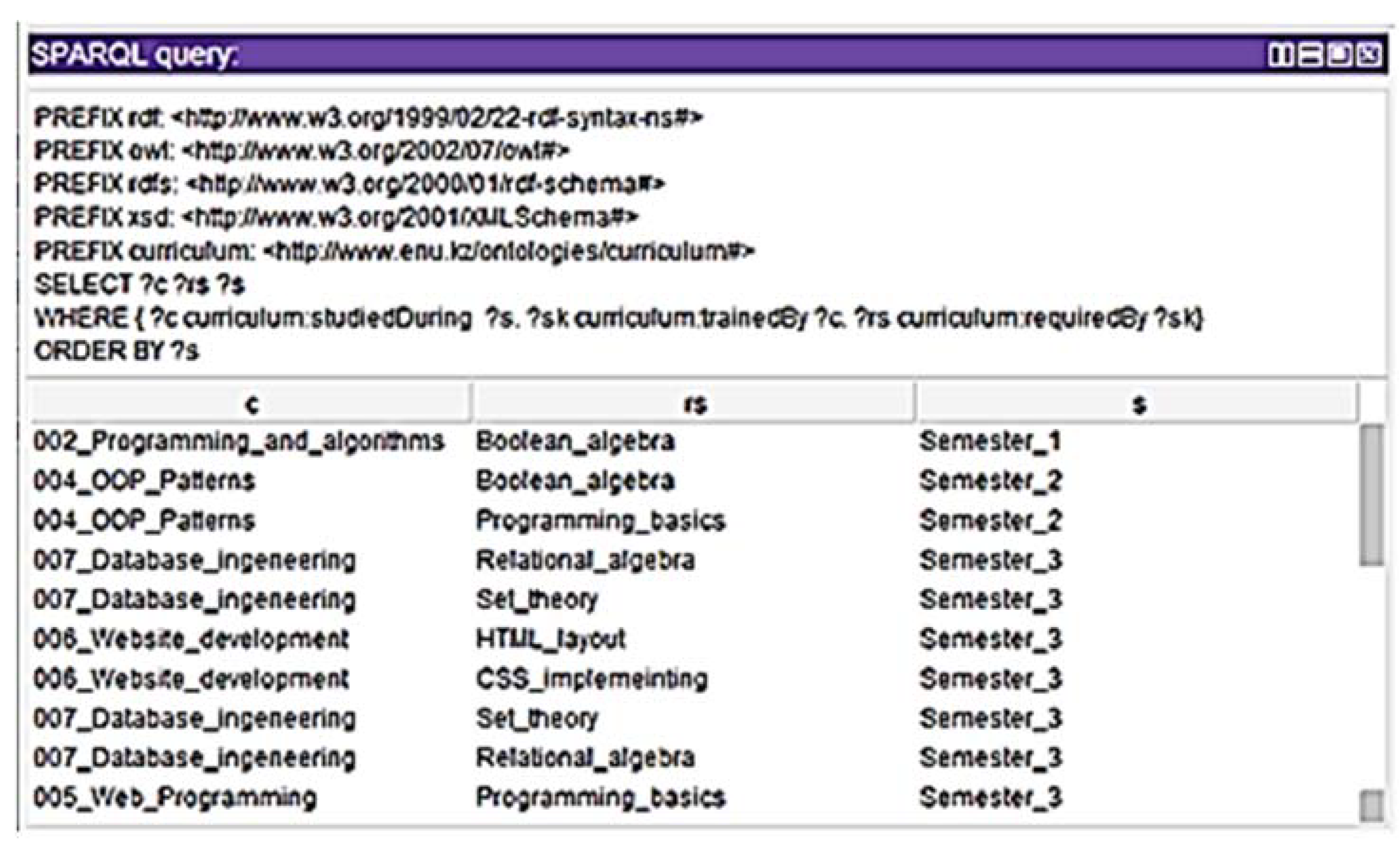

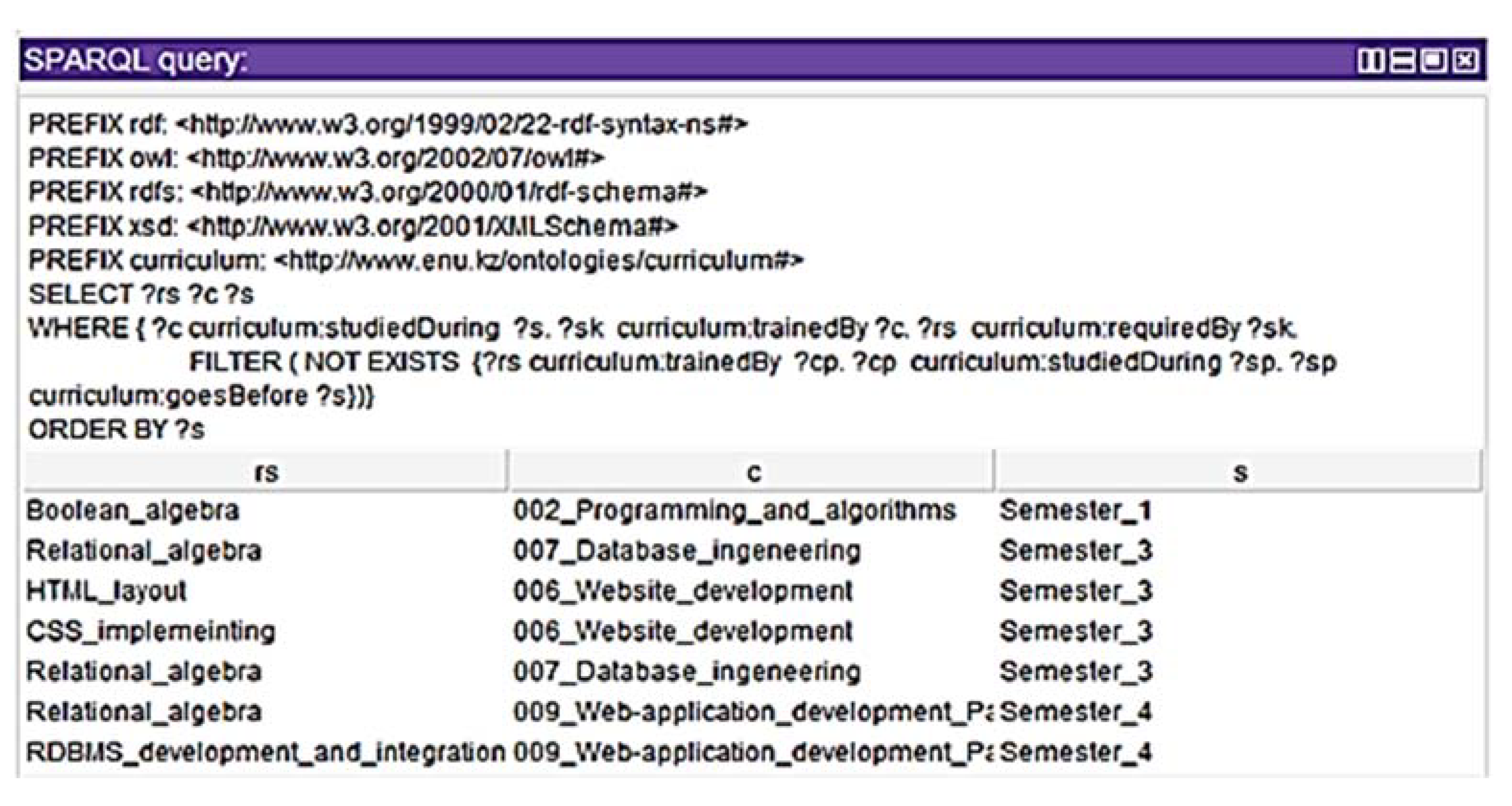

5.4. Analysis of the Consistency of Course Prerequisites and Learning Outcomes

6. Results and Discussion

- Q1.

- Is it possible to build, using an object-oriented approach, a detailed ontological model of an educational programme that combines courses, skills, and training periods?The answer to this research question is: YES, we did it. It should only be noted that for real cases (eg a four-year educational programme with a large number of courses, skills and training periods), the developed models are very complex and difficult to use.

- Q2.

- Is it possible to automate the analysis of the consistency of course prerequisites and learning outcomes of an educational programme and its ontological model with the use of appropriate software?The answer to this question is also: YES. Specialized software was used in the work not only to build the model, but also to explore it quite easily and automatically. A special query language for logical reasoning was used: SPARQL.

- Q3.

- Can the developed ontological model of the educational programme be easily integrated with the Learning Management Systems software?The answer to this question is: NO. LMSs mostly use relational database management systems in the data layer. Meanwhile, SPARQL queries cannot be easily implemented in this technology, i.e., in Structured Query Language (SQL). The implementation or integration of both technologies will require separate research.

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kurzaeva, L.V.; Povitukhin, S.A.; Usataya, T.V.; Usatiy, D.U. The Development of Ontological Model for Increasing the Competitiveness of University Graduates in Information Technologies. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1691, 012003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksenov, A.; Borisov, V.; Shadrin, D.; Porubov, A.; Kotegova, A.; Sozykin, A. Competencies Ontology for the Analysis of Educational Programs. In Proceedings of the Ural Symposium on Biomedical Engineering, Radioelectronics and Information Technology (USBEREIT) 2020 Conference, Yekaterinburg, Russia, 14–15 May 2020; Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/9117793 (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- Sánchez Gálvez, L.A.; Anzures García, M.; Campos Gregorio, Á. Weighted Bidirectional Graph-Based Academic Curricula Model to Support the Tutorial Competence. Computación y Sistemas 2020, 24, 619–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandić, M. Semantic Web Based Software Platform for Curriculum Harmonization. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Web Intelligence, Mining and Semantics, Novi Sad, Serbia, 25–27 June 2018; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protégé. Available online: https://protege.stanford.edu/ (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- Piedra, N.; Caro, E.T. LOD-CS2013: Multileaming through a Semantic Representation of IEEE Computer Science Curricula. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON), Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Spain, 17–20 April 2018; pp. 1939–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quezada-Sarmiento, P.A.; Elorriaga, J.A.; Arruarte, A.; Jumbo-Flores, L.A. Used of Web Scraping on Knowledge Representation Model for Bodies of Knowledge as a Tool to Development Curriculum. In Trends and Applications in Information Systems and Technologies; Rocha, Á., Adeli, H., Dzemyda, G., Moreira, F., Ramalho Correia, A.M., Eds.; WorldCIST 2021. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing (AISC 2021); Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 1366, pp. 611–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aeiad, E.; Meziane, F. An Adaptable and Personalised E-Learning System Applied to Computer Science Programmes Design. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2018, 24, 1485–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgueño, L.; Ciccozzi, F.; Famelis, M.; Kappel, G.; Lambers, L.; Mosser, S.; Paige, R.F.; Pierantonio, A.; Rensink, A.; Salay, R.; et al. Contents for a Model-Based Software Engineering Body of Knowledge. Softw. Syst. Model. 2019, 18, 3193–3205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stancin, K.; Poscic, P.; Jaksic, D. Ontologies in Education—State of the Art. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2020, 25, 5301–5320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demchenko, Y.; Stoy, L. Research Data Management and Data Stewardship Competences in University Curriculum. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON), Vienna, Austria, 21–23 April 2021; pp. 1717–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, H.-S.; Kim, J.-M. Semantic Model of Syllabus and Learning Ontology for Intelligent Learning System. In Computational Collective Intelligence. Technologies and Applications; Hwang, D., Jung, J.J., Nguyen, N.T., Eds.; ICCCI 2014; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; Volume 8733, pp. 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demchenko, Y.; Comminiello, L.; Reali, G. Designing Customisable Data Science Curriculum Using Ontology for Data Science Competences and Body of Knowledge. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Big Data and Education, London, UK, 30 March–1 April 2019; pp. 124–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katis, E.; Kondylakis, H.; Agathangelos, G.; Vassilakis, K. Developing an Ontology for Curriculum and Syllabus. Lect. Notes Comput. Sci. 2018, 11155, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seitz, P. Curriculum Alignment among the Intended, Enacted, and Assessed Curricula for Grade 9 Mathematics. J. Can. Assoc. Curric. Stud. 2017, 15, 72–94. [Google Scholar]

- Bay, E. Developing a Scale on “Factors Regarding Curriculum Alignment”. J. Educ. Train. Stud. 2016, 4, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijngaards-de Meij, L.; Merx, S. Improving Curriculum Alignment and Achieving Learning Goals by Making the Curriculum Visible. Int. J. Acad. Dev. 2018, 23, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaltry, C. A New Model for Organizing Curriculum Alignment Initiatives. Adv. Physiol. Educ. 2020, 44, 658–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Zhang, W.; He, Y.; Wen, J.; Li, M. Design and Implementation of Curriculum Knowledge Ontology-Driven SPOC Flipped Classroom Teaching Model. Educ. Sci. Theory Pract. 2018, 18, 1351–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsayed, E. Interaction with Content through the Curriculum Lifecycle. In Proceedings of the 2009 Ninth IEEE International Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies, Riga, Latvia, 15–17 July 2009; pp. 730–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmiento, C.; Duarte, O.; Barrera, M.; Soto, R. Semi-Automated Academic Tutor for the Selection of Learning Paths in a Curriculum: An Ontology Based Approach. In Proceedings of the IEEE 8th International Conference on Engineering Education, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 7–8 December 2016; pp. 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katis, E. Semantic Modeling of Educational Curriculum and Syllabus. Master’s Thesis, School of Applied Technology, Create, Greece, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, H.; Kim, J. An Ontological Approach for Semantic Modeling of Curriculum and Syllabus in Higher Education. Int. J. Inf. Educ. Technol. 2016, 6, 365–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raud, Z.; Vodovozov, V.; Petlenkov, E.; Serbin, A. Ontology-Based Design of Educational Trajectories. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 59th International Scientific Conference on Power and Electrical Engineering of Riga Technical University (RTUCON), Riga, Latvia, 12–13 November 2018; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Liu, Q.; Zhou, W.; Mao, G.; Huang, J.; Huang, H. A Semantic Web-Based Recommendation Framework of Educational Resources in E-Learning. Technol. Knowl. Learn. 2018, 25, 811–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulakakis, Y.; Vassilakis, K.; Kalogiannakis, M.; Panagiotakis, S. Ontological approach of Educational Resources: A Proposed Implementation for Greek Schools. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2016, 22, 1737–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouf, S.; Abd Ellatif, M.; Salama, S.E.; Helmy, Y. A Proposed Paradigm for Smart Learning Environment Based on Semantic Web. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 72, 796–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrhar, K.; Douimi, O.; Abik, M.; Benabdellah, N.C. Towards a Semantic Integration of Data from Learning Platforms. IAES Int. J. Artif. Intell. (IJ-AI) 2020, 9, 535–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renzella, J.; Cain, A.; Schneider, J.-G. Verifying Student Identity in Oral Assessments with Deep Speaker. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2021, 3, 100044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadir, A.C.; Aliane, H.; Guessoum, A. Ontology Learning: Grand Tour and Challenges. Comput. Sci. Rev. 2021, 39, 100339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapia-Leon, M.; Rivera, A.C.; Chicaiza, J.; Luján-Mora, S. Application of Ontologies in Higher Education: A Systematic Mapping Study. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON), Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Spain, 17–20 April 2018; pp. 1344–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Qi, W. Temporal Tracking and Early Warning of Multi Semantic Features of Learning Behavior. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2022, 3, 100045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kay, J.; Bartimote, K.; Kitto, K.; Kummerfeld, B.; Liu, D.; Reimann, P. Enhancing Learning by Open Learner Model (OLM) Driven Data Design. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2022, 3, 100069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggs, J. Enhancing Teaching through Constructive Alignment. High. Educ. 1996, 32, 347–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggs, J. What the Student Does: Teaching for Enhanced Learning. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 1999, 18, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggs, J.; Tang, C.S.K. Train-The-Trainers: Implementing Outcomes-Based Teaching and Learning in Malaysian Higher Education. Malays. J. Learn. Instr. 2011, 8, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viswanathan, N.; Meacham, S.; Adedoyin, F.F. Enhancement of Online Education System by Using a Multi-Agent Approach. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2022, 3, 100057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Hafeez, Y.; Humayun, M.; Jamail, N.S.M.; Aqib, M.; Nawaz, A. Enabling Recommendation System Architecture in Virtualized Environment for E-Learning. Egypt. Inform. J. 2022, 23, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, R.S.; Gašević, D.; Karumbaiah, S. Four Paradigms in Learning Analytics: Why Paradigm Convergence Matters. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2021, 2, 100021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiyanthuduwage, S.R. A Review: Status Quo and Current Trends in E-Learning Ontologies. In Mobility for Smart Cities and Regional Development—Challenges for Higher Education; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dushutina, E.V. Curriculum Development Approach—The Case of Computing Education. In Knowledge in the Information Society; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 151–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praserttitipong, D.; Srisujjalertwaja, W. Elective Course Recommendation Model for Higher Education Program. Songklanakarin J. Sci. Technol. 2018, 40, 1232–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spasennikov, V.; Morozova, A. Accreditation Examination of Developing Professional Competencies at the University: A Mathematical Model. In Proceedings of the International Science and Technology “Conference FarEastCon 2019”, Vladivostok, Russia, 29 October 2019; pp. 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clear, A.; Clear, T.; Vichare, A.; Charles, T.; Frezza, S.; Gutica, M.; Lunt, B.; Maiorana, F.; Pears, A.; Pitt, F.; et al. Designing Computer Science Competency Statements: A Process and Curriculum Model for the 21st Century. In Proceedings of the ITiCSE ’20: Innovation and Technology in Computer Science Education, Trondheim, Norway, 17–18 June 2020; pp. 211–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekmanova, G.; Nazyrova, A.; Omarbekova, A.; Sharipbay, A. The Model of Curriculum Constructor. In Proceedings of the Computational Science and Its Applications—ICCSA 2021—21st International Conference, Cagliari, Italy, 13–16 September 2021; pp. 459–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nazyrova, A.; Milosz, M.; Bekmanova, G.; Omarbekova, A.; Mukanova, A.; Aimicheva, G. Analysis of the Consistency of Prerequisites and Learning Outcomes of Educational Programme Courses by Using the Ontological Approach. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 2661. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13042661

Nazyrova A, Milosz M, Bekmanova G, Omarbekova A, Mukanova A, Aimicheva G. Analysis of the Consistency of Prerequisites and Learning Outcomes of Educational Programme Courses by Using the Ontological Approach. Applied Sciences. 2023; 13(4):2661. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13042661

Chicago/Turabian StyleNazyrova, Aizhan, Marek Milosz, Gulmira Bekmanova, Assel Omarbekova, Assel Mukanova, and Gaukhar Aimicheva. 2023. "Analysis of the Consistency of Prerequisites and Learning Outcomes of Educational Programme Courses by Using the Ontological Approach" Applied Sciences 13, no. 4: 2661. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13042661

APA StyleNazyrova, A., Milosz, M., Bekmanova, G., Omarbekova, A., Mukanova, A., & Aimicheva, G. (2023). Analysis of the Consistency of Prerequisites and Learning Outcomes of Educational Programme Courses by Using the Ontological Approach. Applied Sciences, 13(4), 2661. https://doi.org/10.3390/app13042661