Comparison of Philosophical Dialogue with a Robot and with a Human

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Robots versus Other Artifacts

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants

3.2. Conditions

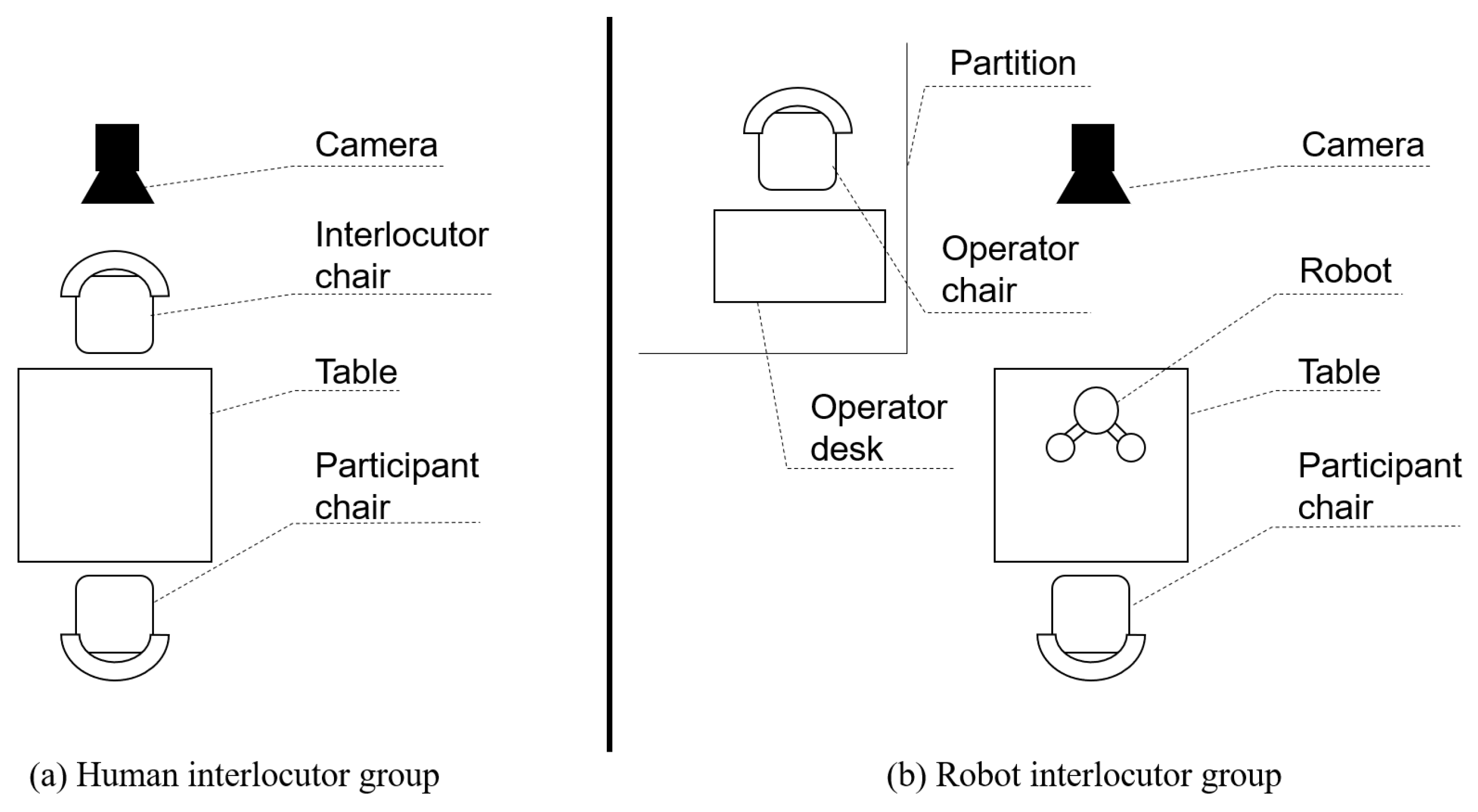

3.2.1. Human Interlocutor Group

3.2.2. Robot Interlocutor Group

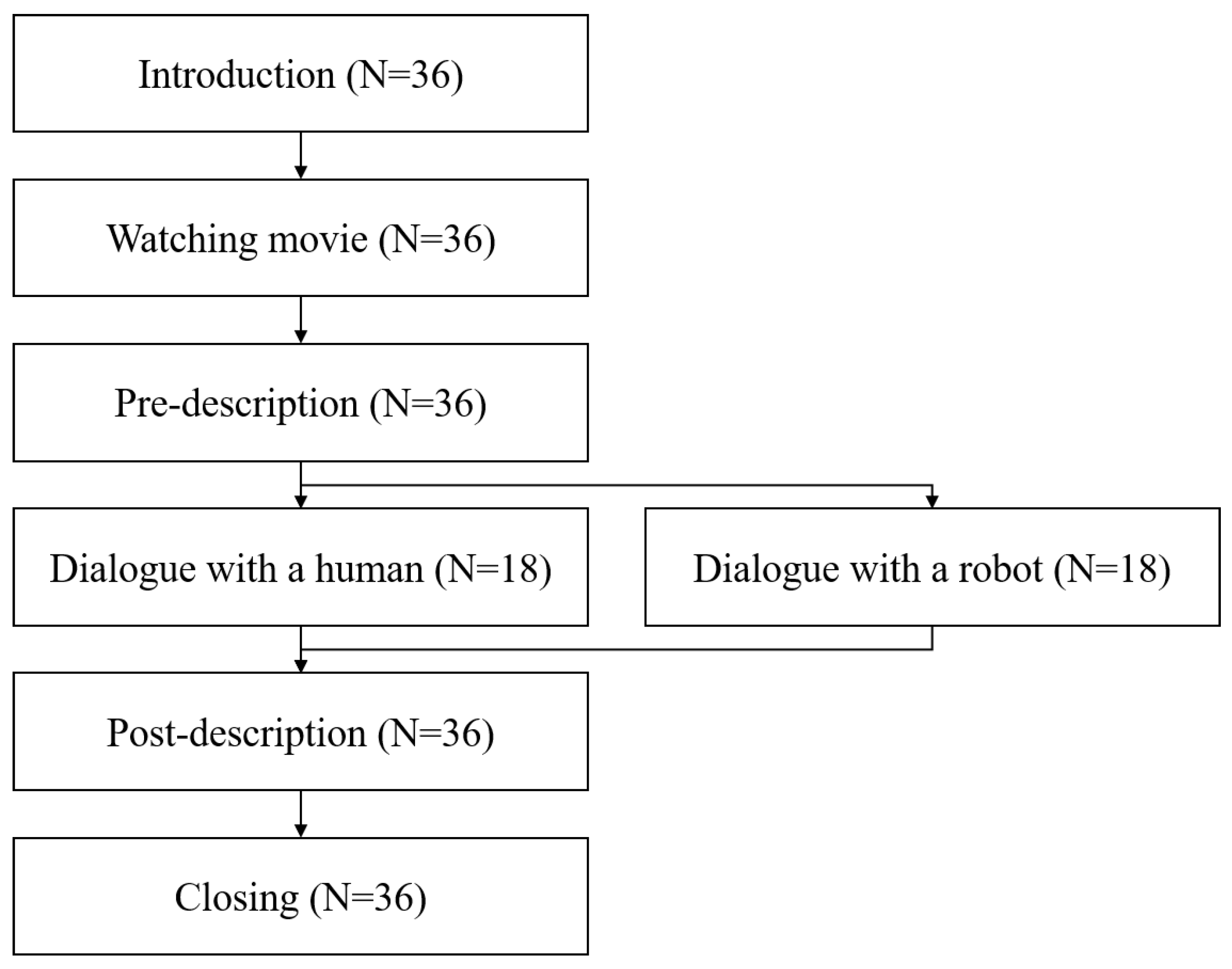

3.3. Procedure

3.4. Materials

3.4.1. Video Stimuli

3.4.2. Free Description Form

3.4.3. Dialogue Scenario

- A: Do you think that racism should not exist?

- B: (Answer)

- A: Uh-hah. For example, let us suppose that you are born as a human again in the next life. However, you don’t know what country you will be born in, your race, or your abilities yet. At this time, what rules do you think should be in the world?

- B: (Answer)

- A: I see. By the way, in the latter half of the video, many people were asserting their own opinions. What would you do if you disagreed with some of the rules that everyone decided?

- B: (Answer)

- A: I understand. Then, how can we decide what the proper rules are for everyone?

- B: (Answer)

- A: This is a difficult question. I think we need to look for other ways than talking together.

3.5. Environment

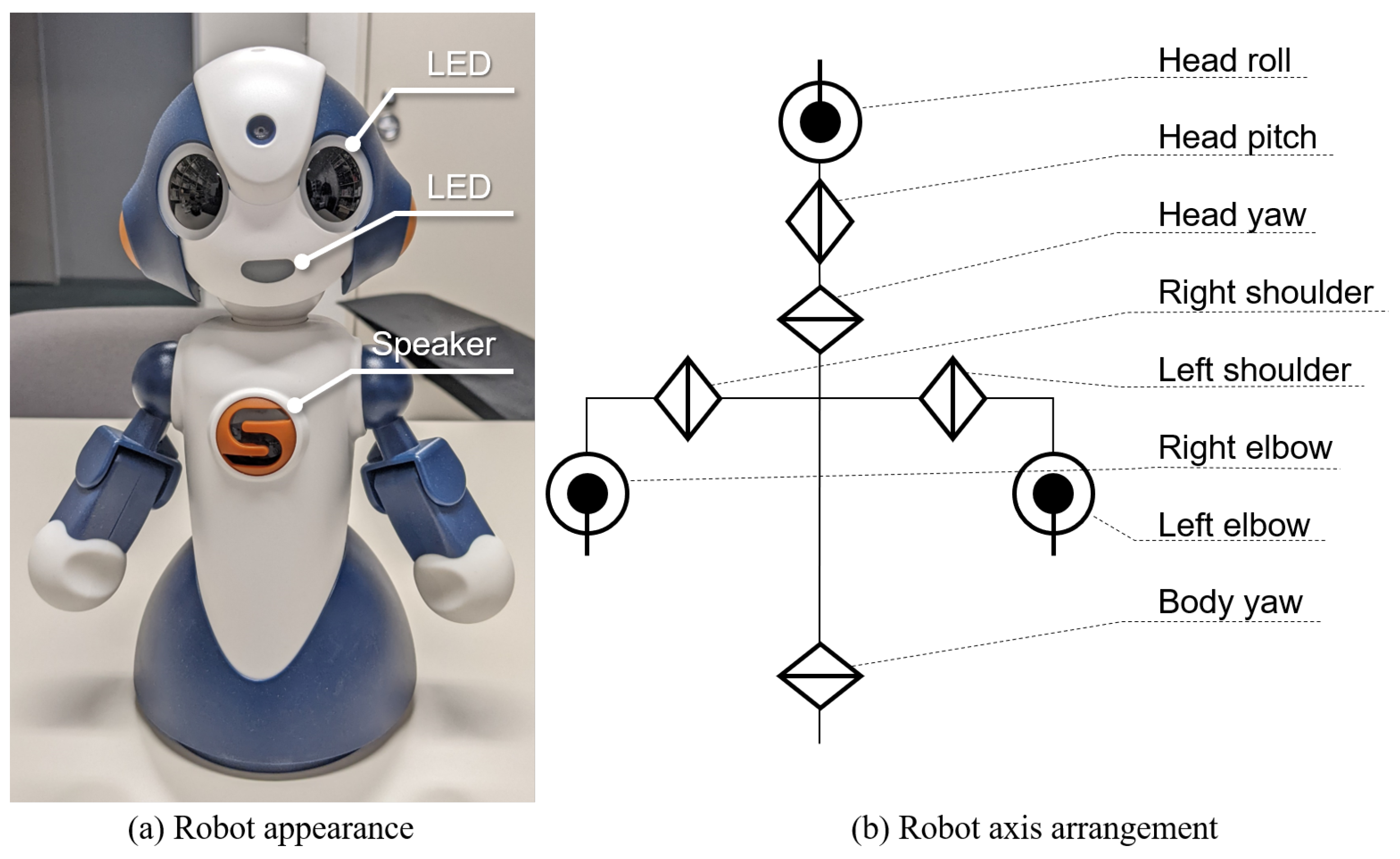

3.6. Robot

3.7. Measurements

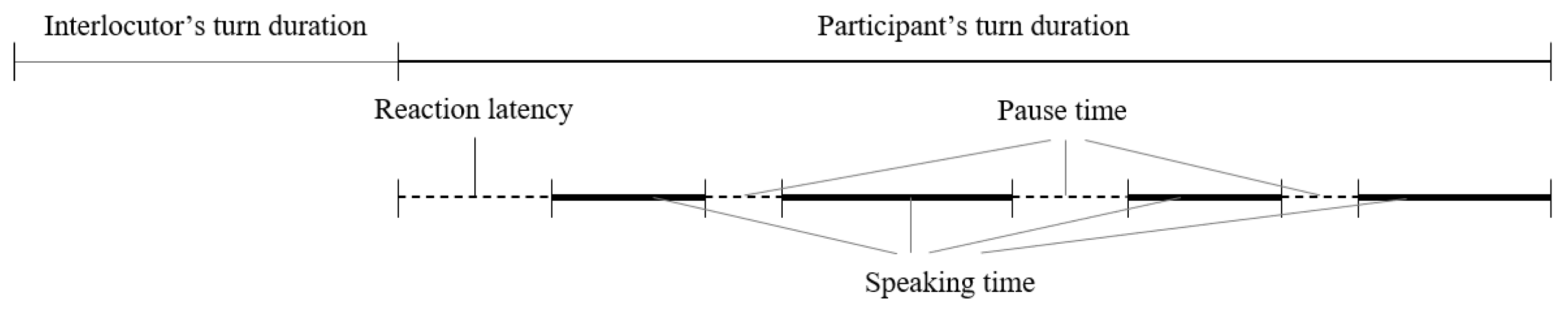

3.7.1. Speech Analysis

3.7.2. Free Description Analysis

- Hesitation: A description has phrases that indicate hesitation, such as “I felt nervous to talk with the listener” or “It was difficult to choose words due to the listener”.

- No hesitation: A description has phrases that indicate no hesitation, such as “I did not feel hesitation” or “It was easy to talk with the listener”.

- Both: A description has hesitation phrases and no-hesitation phrases.

- Unknown: A description has no mention of hesitation.

4. Results

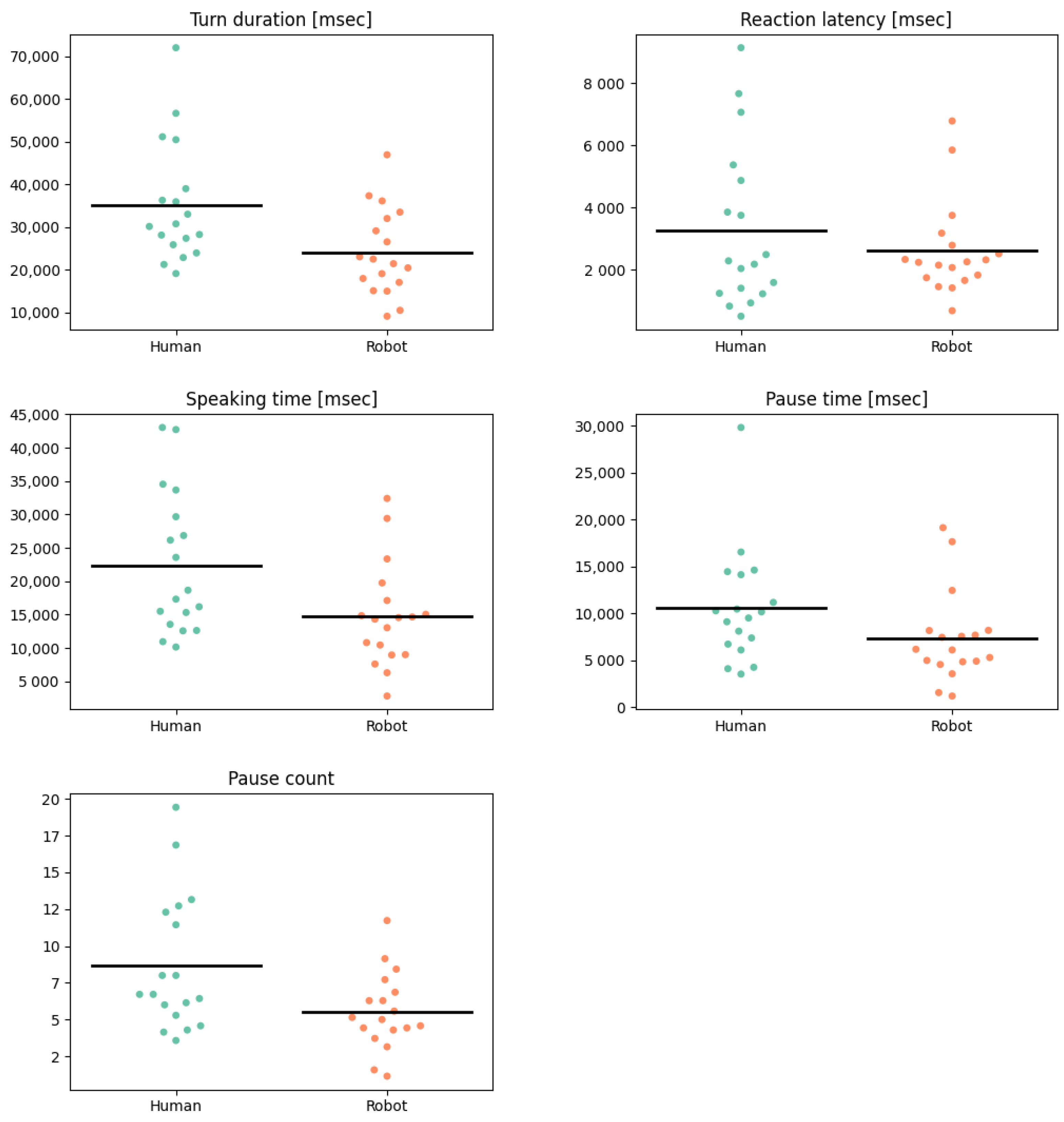

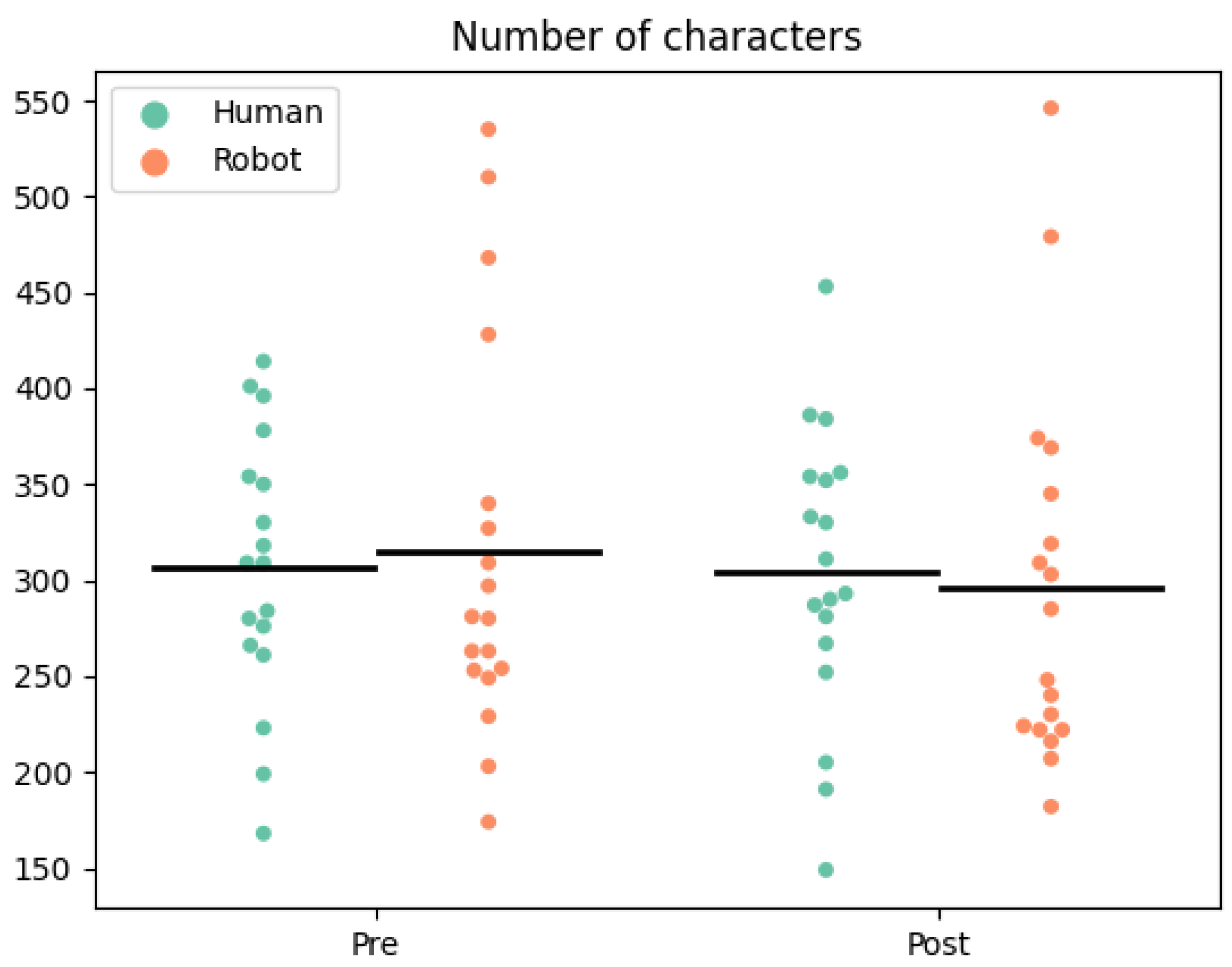

4.1. Speech Analysis

4.2. Free Description Analysis

Feeling of Hesitation

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Implications

5.2. Applications

5.3. Limitations and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rakoczy, M. Philosophical dialogue—Towards the cultural history of the genre. Ling. Posnan. 2017, 59, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Benson, H.H. Essays on the Philosophy of Socrates; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Overby, K. Student-Centered Learning. ESSAI 2008, 9, 154–196. [Google Scholar]

- Peter, B.R. Philosophical Counseling–Theory and Practice; Praeger: Westport, CT, USA; London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Sutet, M. Un Cafe pour Socrate; Robert Laffont: Paris, France, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, H.S. Unpleasant interactions. J. Int. Stud. 2020, 5, 95–104. [Google Scholar]

- Uchida, T.; Takahashi, H.; Ban, M.; Shimaya, J.; Minato, T.; Ogawa, K.; Yoshikawa, Y.; Ishiguro, H. Japanese Young Women did not discriminate between robots and humans as listeners for their self-disclosure-pilot study. Multimodal Technol. Interact. 2020, 4, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutlu, B.; Kanda, T.; Forlizzi, J.; Hodgins, J.; Ishiguro, H. Conversational gaze mechanisms for human-like robots. ACM Trans. Interact. Intell. Syst. (TiiS) 2012, 1, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeill, D. Hand and Mind: What Gestures Reveal about Thought; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Biau, E.; Soto-Faraco, S. Beat gestures modulate auditory integration in speech perception. Brain Lang. 2013, 124, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kidd, C.D.; Breazeal, C. Effect of a robot on user perceptions. In Proceedings of the 2004 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS) (IEEE Cat. No. 04CH37566), Sendai, Japan, 28 September–2 October 2004; Volume 4, pp. 3559–3564. [Google Scholar]

- Shinozawa, K.; Naya, F.; Yamato, J.; Kogure, K. Differences in effect of robot and screen agent recommendations on human decision-making. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2005, 62, 267–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fridin, M.; Belokopytov, M. Embodied robot versus virtual agent: Involvement of preschool children in motor task performance. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2014, 30, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, T.E. Young People and News: A Report from the Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public Policy, John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University; Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public Policy: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gentina, E.; Chen, R. Digital natives’ coping with loneliness: Facebook or face-to-face? Inf. Manag. 2019, 56, 103138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomura, T.; Kanda, T.; Suzuki, T. Experimental investigation into influence of negative attitudes toward robots on human–robot interaction. AI Soc. 2006, 20, 138–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reidenbach, R.E.; Robin, D.P. Toward the Development of a Multidimensional Scale for Improving Evaluations of Business Ethics. J. Bus. Ethics 1990, 9, 639–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iio, T.; Yoshikawa, Y.; Chiba, M.; Asami, T.; Isoda, Y.; Ishiguro, H. Twin-robot dialogue system with robustness against speech recognition failure in human-robot dialogue with elderly people. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Iio, T.; Yoshikawa, Y.; Ishiguro, H. Double-meaning agreements by two robots to conceal incoherent agreements to user’s opinions. Adv. Robot. 2021, 35, 1145–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawls, J. A Theory of Justice; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Aristotle; Sinclair, T.A.; Saunders, T.J. The Politics; Penguin Books: London, UK, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Matsui, Y.; Kanoh, M.; Kato, S.; Nakamura, T.; Itoh, H. A Model for Generating Facial Expressions Using Virtual Emotion Based on Simple Recurrent Network. J. Adv. Comput. Intell. Intell. Inform. 2010, 14, 453–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senft, G. Phatic communion. In Handbook of Pragmatics (Loose Leaf Installment); John Benjamins: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, R.; Gustafson, K.; Strangert, E. Modelling hesitation for synthesis of spontaneous speech. In Proceedings of the Speech Prosody 2006, Dresden, Germany, 2–5 May 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, M.B.; Stein, D.J. Social anxiety disorder. Lancet 2008, 371, 1115–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alden, L.E.; Taylor, C.T. Interpersonal processes in social phobia. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2004, 24, 857–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamide, H.; Arai, T. Perceived comfortableness of anthropomorphized robots in US and Japan. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 2017, 9, 537–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Złotowski, J.; Proudfoot, D.; Yogeeswaran, K.; Bartneck, C. Anthropomorphism: Opportunities and challenges in human–robot interaction. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 2015, 7, 347–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiroi, Y.; Ito, A. Influence of the Height of a Robot on Comfortableness of Verbal Interaction. IAENG Int. J. Comput. Sci. 2016, 43, 447–455. [Google Scholar]

- Rae, I.; Takayama, L.; Mutlu, B. The influence of height in robot-mediated communication. In Proceedings of the 2013 8th ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction (HRI), Tokyo, Japan, 3–6 March 2013; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Alhasan, H.S.; Wheeler, P.C.; Fong, D.T. Application of Interactive Video Games as Rehabilitation Tools to Improve Postural Control and Risk of Falls in Prefrail Older Adults. Cyborg Bionic Syst. 2021, 2021, 9841342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Ma, L.; Yang, J.; Wu, J. Human Somatosensory Processing and Artificial Somatosensation. Cyborg Bionic Syst. 2021, 2021, 9843259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group | N | Mean | SD | U | p | Cohen’s d | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turn duration | Human | 18 | 35,111 | 14,049 | 81 | 0.010 | * | 0.906 |

| Robot | 18 | 24,022 | 10,108 | |||||

| Reaction latency | Human | 18 | 3243 | 2591 | 162 | 1.000 | 0.299 | |

| Robot | 18 | 2607 | 1524 | |||||

| Speaking time | Human | 18 | 22,389 | 10,650 | 89 | 0.016 | * | 0.830 |

| Robot | 18 | 14,692 | 7667 | |||||

| Pause time | Human | 18 | 10,599 | 6119 | 106 | 0.064 | 0.596 | |

| Robot | 18 | 7322 | 4797 | |||||

| Pause count | Human | 18 | 8.65 | 4.61 | 97 | 0.041 | * | 0.834 |

| Robot | 18 | 5.52 | 2.62 |

| Category | Group | N | Typical Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hesitation | Human | 7 | - In conversations about discrimination and politics, there is a diversity of ideas, and we need to be mindful of the other person’s thoughts when we speak. (5/7) |

| Robot | 10 | - No facial expressions, gestures, pauses before speech starts, eye contact, etc. (10/10) - It was difficult to grasp the robot’s intent of the questions and to predict the robot’s responses. (5/10) - The robot said too much clearly. (2/10) | |

| No-hesitation | Human | 7 | - The interlocutor had a listening attitude and was basically neutral and did not give a critical response. Furthermore, the interlocutor was not a person concerned. (2/7) - Since the interlocutor was not an acquaintance, it was not necessary to be concerned about the afterward relationship. (1/7) |

| Robot | 5 | - Robot’s pause and backchannels were good. (2/5) - It looks pretty. (1/5) | |

| Both | Human | 1 | - It’s not often that I get a chance to talk to a stranger about something like this, so I was a bit nervous at first, wondering what I would be asked. (1/1) - I didn’t find it difficult to talk, but I was worried about whether I could convey what I wanted to say to the human interlocutor. (1/1) |

| Robot | 3 | I didn’t feel hesitation talking to a robot, but I felt it uncomfortable different from talking with a human being. (2/3) | |

| Unknown | Human | 3 | - Whether to feel hesitation depends on the relationship with the interlocutor or the situation of interaction. (3/3) |

| Robot | 0 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Someya, Y.; Iio, T. Comparison of Philosophical Dialogue with a Robot and with a Human. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 1237. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12031237

Someya Y, Iio T. Comparison of Philosophical Dialogue with a Robot and with a Human. Applied Sciences. 2022; 12(3):1237. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12031237

Chicago/Turabian StyleSomeya, Yurina, and Takamasa Iio. 2022. "Comparison of Philosophical Dialogue with a Robot and with a Human" Applied Sciences 12, no. 3: 1237. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12031237

APA StyleSomeya, Y., & Iio, T. (2022). Comparison of Philosophical Dialogue with a Robot and with a Human. Applied Sciences, 12(3), 1237. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12031237