Abstract

Microservice architecture has emerged as a powerful paradigm for cloud computing due to its high efficiency in infrastructure management as well as its capability of largescale user service. A cloud provider requires flexible resource management to meet the continually changing demands, such as auto-scaling and provisioning. A common approach used in both commercial and open-source computing platforms is workload-based automatic scaling, which expands instances by increasing the number of incoming requests. Concurrency is a request-based policy that has recently been proposed in the evolving microservice framework; in this policy, the algorithm can expand its resources to the maximum number of configured requests to be processed in parallel per instance. However, it has proven difficult to identify the concurrency configuration that provides the best possible service quality, as various factors can affect the throughput and latency based on the workloads and complexity of the infrastructure characteristics. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the applicability of an artificial intelligence approach to request-based auto-scaling in the microservice framework. Our results showed that the proposed model could learn an effective expansion policy within a limited number of pods, thereby showing an improved performance over the underlying auto expansion configuration.

1. Introduction

With the advancement and spread of Virtual Machine and container technology, the adoption of microservice computing models has increased substantially [1]. Microservice computing provides two main benefits to users: First, it is easy to scale when in use, as it is not difficult to develop idle VMs or containers. Second, because it is delegated to a cloud provider, there is no overhead related to infrastructure maintenance for users. Microservice also brings other advantages such as flexibility as well as the capability of immediate scalability to automatically add or remove resources depending on the incoming load. Some microservice frameworks use a resource-based Kubernetes Horizontal Pod Autoscaler (HPA) to drive expansion through CPU or memory utilization thresholds per instance. As a result, the Auto-Scaling function depends on each system component delivering fast and accurate calculations [2]. Commercially available microservice platforms are often characterized by workload-based expansion, where they provide additional resources as the incoming traffic increases. For example, AWS lambda initializes for each new request that comes in until the limit is reached [3]. Continually creating new requests in this way leads to a speed delay problem, because it is processed using the HPA method. To minimize this problem, one may use an open-source framework that supports parallel processing up to a predefined number of simultaneous requests per instance [4]. When so-called concurrency is reached, the Knative Pod Autoscaler (KPA) deploys additional pods to handle the extra loads. Simultaneous parameters can also be manually adjusted to use resources more efficiently and adjust automatic scaling systems to best suit individual workloads.

Existing research shows that the use of different workloads can affect microservice performance and cause latency differences up to a few seconds. Since this can have a significant impact on user experience, we proposed a reinforcement learning RL-based model that dynamically determines the optimal concurrency for individual workloads. In general, RL operates under the idea that agents can learn effective decision-making policies by experiencing a series of trial-and-error interactions with the environment, then evaluating the current state of the system dynamics in each iteration and determining the operation of opening the CPU core. After learning, the agent receives positive or negative rewards and consequently learns the advantages of each reward-status combination. Since reinforcement learning can adapt to changes in runtime without requiring prior knowledge of the incoming workloads, the RL algorithm has been adopted as a valid method in the field of VM auto expansion technology. Therefore, we evaluated the applicability of the established RL algorithm Q-learning to determine the level of concurrency with optimized performance. Specifically, we implemented a cloud-based framework and performed three consecutive experiments.

We analyzed the performance changes of various workload profiles in Auto-Scaling configurations. The results demonstrated the dependence of throughput as well as delay time during overload work; they also showed the possibility of improvement through adaptive expansion setting. Informed by these results, we reinforced the framework with intelligent RL-based logic to evaluate the ability of self-learning algorithms to make effective decisions in the microservice framework. The results showed that the proposed model can learn appropriate expansion policies within a limited time without prior knowledge of incoming workloads, thereby showing improved performance over basic automatic CPU expansion settings of the framework. Lastly, we proved that the proposed RL algorithm achieves better performance than all considered alternatives.

The rest of this work is organized as follows: Section 2 introduces the microservice platform, Q-learning, and the new Q-Learning theory, and this section reviews related work into both the intelligent microservice framework and cloud-based Auto-Scaling technology (Table 1). Section 3 proposes a Q-learning model to utilize these findings to improve the auto-scaling functionality of HPA as well as the general performance. Section 4 compares the performance of the existing HPA with the HPA applying the query algorithm and the performance of the HPA applying the proposed Quad Q Network. Finally, Section 5 provides the conclusions and limitations of this study, along with possible future research directions.

Table 1.

A Overview of Cloud computing & Reinforcement Learning Discussed in Section 2.

2. Literature Review: Related Work

2.1. Microservice Computing

As microservice computing continues to spread, scalability represents one of the key elements being researched, and there is high interest in providing various solutions and comparing their performance [4]. We benchmarked a variety of microservice platforms, including extensions focused on Amazon Lambda, Microsoft Azure Functions, Google Cloud Functions, and IBM Cloud Functions [5,6,7], and found that the open source serverless framework paid more attention to auto-scaling functions. Another comparison of qualitative and quantitative features of Kubless, OpenFaas, Apache Openwhisk, and Knative came to the same conclusion, although user control of custom service quality requirements was generally limited [8]. One study proposed an intelligent automatic expansion Kubernetes HPA to solve the computing resource management problems listed above [9]. This study used the Kubernetes concurrency level adjustment function to compare the performance of various workload scenarios and investigate the applicability of auto-scaling functions.

2.2. Auto-Scaling

The auto-scaling of cloud resources has emerged as a subject of intensive research in recent years due to the fact that customized resource allocation is one of the key characteristics of increased adaptation to cloud computing [10]. Other taxonomies have been proposed to classify numerous techniques at the algorithm level, with Threshold-based Rules, Queuing Theory, and RL being the main categories. Various studies have also been conducted with a focus on public cloud providers such as Amazon ECS using Auto-Scaling [9]. Even with simplified implementations, developing appropriate threshold-based rules requires expert knowledge and precise application understanding [9,10,11,12,13].

In practice, we use the Kubernetes scaling engine, which makes appropriate automatic scaling decisions to handle the actual variations in incoming requests. It can also be set up for resource over-provisioning by introducing certain management parameters for cloud application providers. Providing adequate application expansion represents one of the most important elements for cloud providers, as flexible and skillful resource distribution is a key concept of cloud computing [11,12]. Auto-scaling has been classified and studied using basic theoretical models or methods.

Threshold-based: Studies focusing on threshold-based expansion rules have improved vertical and horizontal elasticity performance in cloud systems of lightweight virtualization technology [14,15,16]. Specifically, one study examined a resource utilization-based automatic expansion system that demonstrates Kubernetes’ VPA through its ability to dynamically adjust container allocation in the Kubernetes cluster without interruption [14]. Further, based on IBM’s principle of autonomous computing MAPE-K, an Elastic Docker study was conducted that autonomously supports the vertical elasticity of docker containers [15]. The above two papers integrated container movement and reviewed the possibility of vertical auto-scaling. Another study aimed to improve horizontal auto-scaling [16].

Reinforcement learning-based: One study combined two reinforcement learning (RL) approaches—Q-learning and state-compensation-state-behavior (SARSA) algorithms—with self-adaptive fuzzy logic controllers that lead to dynamic resource allocation to the virtual machine (VM) [17]. Another work provided a threshold-based solution for the automatic scaling of horizontal containers that uses Q-learning to adjust scaling thresholds [18]. In a different study, a group of dockers proposed different RL solutions (i.e., Q learning, Dyna-Q, and model-based) that utilize various levels of knowledge about system dynamics [19,20]. They conducted simulations and compared the behavior of their models with those of typical M/M/c queues.

RL provides an interesting approach to agent learning about the most suitable extension measures without prior knowledge [7]. In recent years, various studies have investigated the applicability of modeless RL algorithms such as Q-learning [10]. With the advent of container-based applications, this field has attracted greater attention. However, few studies have focused on areas that can mitigate the general auto-expansion problem of VM or container configurations. Therefore, the objective of the present study was to investigate the applicability of newly introduced Q learning to request-based automatic expansion in a server-free environment. Unlike previous studies on direct vertical or horizontal scaling using RL [13], we proposed a model that could learn effective scaling policies by adapting simultaneous request levels per container instance to specific workloads.

2.3. Container Computing

Over the past few years, various middleware frameworks of containers have been proposed in attempts to reduce the difference between the modern high computing needs with simultaneous interest in multiple applications and the hardware capabilities by IoT node/end user [21]. For example, small VMs supported in Spring and NodeJS, Python runtime environments, are designed to allow for programming and code mobility of sensors and other IoT devices [22,23,24,25]. The efficiency of applications depends heavily on resource virtualization technologies that limit hardware flexibility and depend on code [26]. As a result, there has recently been increased interest in lightweight virtualization solutions such as docker containers [27]. Although virtualized applications/services can be implemented more effectively with respect to hypervisor or VM-based virtualization technology, there is a need for lower overhead [28].

Containers can be defined as a collection of processes that are separated from the rest of the system encapsulating the associated dependencies [29]. Containers do not require a complete guest operating system (OS), so they are much lighter than VMs [30]. For example, a container can boot faster than a VM, in just a few seconds, and involves a resource set of less than 2GB, thus allowing it to scale to meet requirements as necessary [27].

Lightweight virtualization is highly related to microservice networks [31]. This is because it allows for the fast creation and booting of virtualized instances, the possibility of having many applications simultaneously running on the same host, and separation between instances running on the same host while reducing overhead costs. Further, container-based services do not imply strong dependence on a given platform, programming language, or specific application domain, so they have the flexibility to be developed once and deployed everywhere.

Research related to the implementation of smart containers, dockers, Apache, and Kubernetes is currently being actively conducted. For example, studies have proposed fuzzy enhancement learning strategies for microservice allocation [32]. Research has also been conducted to suggest cluster intelligence-based strategies that can contribute to scheduling in big data applications [33]. In both cases, the proposals are limited to the scheduling of smart containers in cloud computing, and no proposals have been presented for the scheduling of smart containers in intelligent auto-scaling. Therefore, previous studies have not been able to propose an essential solution for building an intelligent microphone service.

2.4. Basic Microservice Platform

The open source Microservice platform provides a set of Kubernetes-based middleware components that can support the deployment and service of serverless applications, including the ability to automatically scale resources as necessary [6]. When the service revision expands, the receiving gateway is structured to first forward the receiving request to the activator. The activator then reports the information to the auto regulator, which then instructs the distribution of the revised version to be expanded appropriately.

The fact that the request is buffered until the user pod of the revision is available might have negative effects in terms of waiting time, as the request is blocked during that time. By contrast, if one or more replicas remain active, the active program can be ignored, and the traffic can flow directly to the user’s pod to increase the efficiency.

When the request reaches the pod, it is channeled by the queue proxy container and then processed in the user container. The queue proxy only allows a specific number of requests to enter the user container at the same time, and queues requests exceeding this number if necessary. The number of parallel requests processed is specified by the concurrency parameters that have been configured for a particular revision. Depending on the concurrency set in the revision, the cue proxy can only simultaneously process that number of requests by the user container, thus queueing requests as necessary.

Each cue proxy measures the incoming load and then reports the average concurrency per second and the request on an individual port. The metrics for all queue proxy containers are scraped by the Autoscaler component, which determines the number of new pods to be added or removed to maintain the desired level of concurrency.

2.5. Reinforcement Learning

Reinforcement Learning (RL) refers to a collection of trials and errors in which agents are trained to interact with their environment and make good decisions by being given positive or negative feedback in the form of rewards for each action. The widely used RL algorithm is Q-learning without a model. Q-learning is a stepwise learning that can train the approximation of the optimal behavior value. The approximation of the Q value specifies the cumulative reward that can be expected when the agent starts with state (s), takes action (a), and then forever acts on the optimal policy afterward. By observing the actual reward in each iteration, the optimization of the Q-function is performed step by step.

RL describes how much newly observed information redefines old information, along with discount factors used to balance present and future rewards. Since RL is a trial-and-error method, the agent must choose between exploring new measures and using the current best option during training [9]. With a certain probability, the agent selects the task that is anticipated to maximize the expected return based on the optimal policy; i.e., the task with the highest Q value starting with s.

2.6. Introduction of Deep Q Network, Double DQN

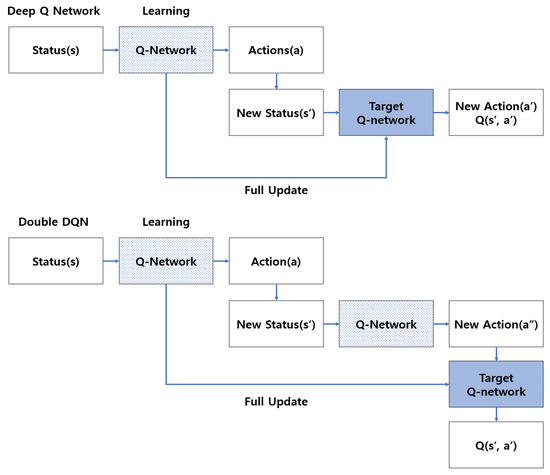

The Deep Q Network (DQN), a representative reinforcement learning algorithm, is based on the mathematical model definition of the Markov Decision Process (MDP), wherein an agent exploring an environment recognizes the current state and takes an action to obtain an optimal policy for a series of actions that maximizes the cumulative rewards. Figure 1 illustrates the application of the idea of the target network to DQN, which is expressed by updating the Q value in Q-Learning [34,35,36].

Figure 1.

Structure of learning using the target network in DQN & Double DQN.

The target network maintains a fixed value while the original Q Network learns, but it periodically resets to the original Q Network value. This can lead to effective learning because it can be close to the Q Network with such a fixed target network [37,38,39,40].

As shown in Figure 1, Double DQN is an algorithm that involves the use of two Q Networks to improve the accuracy of Q-learning before DQN. However, the fact that Q values tend to be overestimated is a limitation, as the accuracy of Q-learning is reduced. Double DQN is an algorithm developed by combining the above ideas in the existing DQN algorithm with two Q Networks. When the state value s′ is given in maxQ(s′,a′) in the existing Q-learning formula, a′ with the highest Q value in the Q Network is selected, after which the Q value is multiplied by γ to derive the target value that Q(s,a) should be close to [41,42]. The aspect that needs to be improved is that the same Q network is used in both the selection process and the process of obtaining the Q value. The Q value selected to use the maximum operation is generally a large value, and as learning progresses, the Q value increases more than necessary. As a result, when the Q value increases, the performance of the Q Network is greatly degraded. To prevent this, two Q Networks should be created and learned [43,44].

3. Introducing Intelligent Kubernetes Framework Design Methods and Workloads

For customized HPA-based auto-scaling technology, we designed an Intelligent Kubernetes framework that is based on Machine Learning algorithms and which can be expanded. This section describes the first experiment conducted to evaluate the performance of the HPA-based auto-scaling and methods used in the experiment to evaluate AI based auto-scaling. This section also introduces the Microservice Architecture monitoring system environment used to evaluate the auto-scaling performance.

3.1. Proposed Microservice Architecture for Auto-Scaling Performance Evaluation

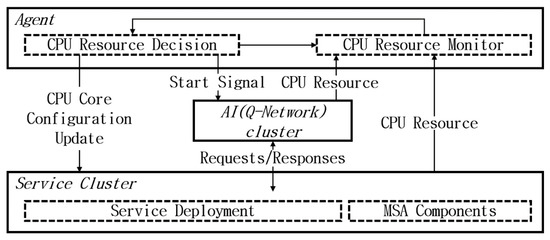

Microservice computing is used for customized applications that have a variety of resource requirements. For example, high traffic loads require significant memory and computing power high parallel analysis operations to process video materials such as Netflix and YouTube videos. Meanwhile, applications like chatbots tend to be low in computing intensity. However, as the number of users increases, the number of requests also increases, thereby requiring more responses. To investigate the auto-scaling impact of various workloads, a synthesized and reliable workload profile that can simulate microservice applications needs to be created. In this study, an API YAML (API Version: v1bera1, Kind: Deployment) file was created to specify a target port. A load operation was then run on the PHP-Apache server. Figure 2 illustrates the Intelligence Microservice Architecture proposed in this study.

Figure 2.

Proposed Intelligence Microservice Architecture for Auto-Scaling Performance Evaluation.

Two separate clusters were set up using Kubernetes to test the auto-scaling capabilities in a high-performance computing environment (Intel i9 X processor, 128GB RAM, NVIDIA GPU RTX 3090 * 2). The sample services used in the experiment were distributed to the service cluster. Each cluster is designed to provide sufficient capacity to host all components as well as avoid performance limitations. Based on the collected metrics, the agent manages the activities of the two clusters, such as updating the configuration of the sample service and adjusting the process flow of the experiment by acting as a Kubernetes user. The existing HPA controls the statuses of the deployed Kubernetes services and enables automatic scaling of additional pods.

ML’s Reinforcement Learning method was used to update the auto-scaling configuration of the service in each iteration to create a new output each time. To comprehensively test the auto-scaling function, we increased the number of copies of the receiving gateways to process load balancing, while focusing only on the auto-scaling function. We also experimentally investigated the Auto-Scaling method using the existing reinforcement learning algorithm and the newly proposed Q Network algorithm.

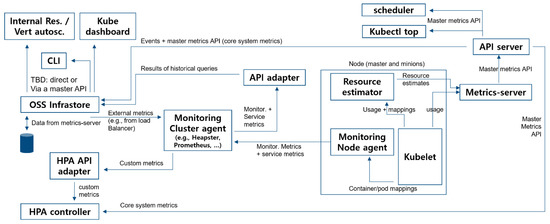

3.2. Customized Kubernetes Environmental Monitoring Architecture

The application performance within the Kubernetes cluster was examined as depicted in Figure 3 below with an architecture designed to monitor the designated Kubernetes environment.

Figure 3.

Customized Kubernetes Environmental Monitoring Architecture.

Using the Open-Source Service (Basic Kubernetes monitoring program), we examined the application performance within the Kubernetes cluster as an architecture to monitor the designated Kubernetes environment. The basic process flow is shown in Figure 3. These metrics (Kubelet, Resource Estimator, and Metrics Server) are used in the core system components, such as the scheduling logic and simple basic UI components. The monitoring pipelines used to collect and expose various metrics in the system to end users via adapters are the Horizontal Pod Autoscaler and the Infrastructure. Two types of metrics are used: system metrics and service metrics. System metrics can be used by all monitored entities, such as CPU and memory usage per container and node. Meanwhile, service metrics are explicitly defined in the application code and exported. Both metrics can be used in the user’s container or system infrastructure components (master components such as API servers, add-on pods running on the master, and add-on pods running on the user nodes).

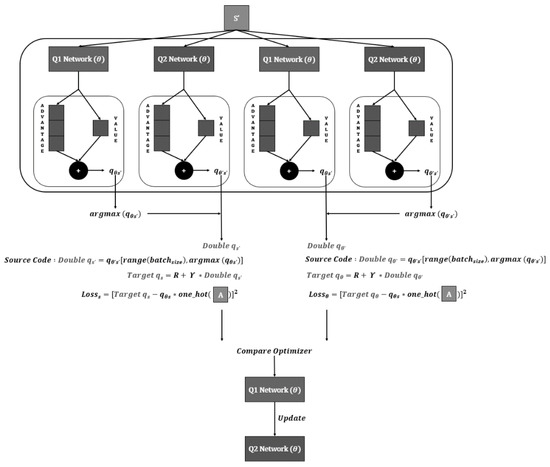

3.3. Customized New Q Network Algorithm Applied to the Experiment

This study introduced a Quad Q Network algorithm that performs Compare Optimizer work on algorithms combining the ideas of Dueling DQN algorithm with existing double DQN algorithms. The existing method of combining Dueling DQN and Double DQN derives the Double qs value by substituting the argmax equation based on the calculated qθ’s value of the Q1 Network in the Dueling DQN with the qθ’s’ value through the new Q2 Network to go through the Double DQN process. Although this algorithm—which operates through the fusion of the Dueling method and the Double method—is structurally complex, it is expected to lead to high performance; however, there is one problem: It is impossible to determine the performance when combining the argmax value based on the Q value calculated by the Q1 Network with the Q2 Network, and it is better to combine the argmax value based on the Q2 Network with the Q1 Network. Therefore, after obtaining the value opposite to the existing value, we strengthened the Q network through the comparison process, thus reducing the loss value and increasing the compensation. The proposed algorithm provides a basis for selecting a Q value that derives excellent performance through comparison and selection of each loss value. This process can describe the structure of a Quad Q Network using four Q networks, then represent it as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Quad Q Network algorithm structure that derives Target Q values with the structures of the Quad Q Network with four Q Networks.

4. Experiment and Results

To determine the performance of intelligent microservices, we first conducted a baseline experiment comparing different workloads in terms of relative performance. This section simulates the application’s existing Horizontal Pod Autoscaler, the Autoscaler applying reinforcement learning to HPA, and the Autoscaler incorporating the proposed reinforcement learning algorithm. In the existing HPA work, the CPU allocation gradually increased for each new experiment, starting with the number of cores. To maximize each core, the response to the request was simulated by applying a load. The time using each core was measured while the maximum number of cores was limited to 10. The detailed experimental results are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

HPA-based auto-scaling performance test results.

Since there is no intelligent algorithm in the existing HPA work that is suitable for predicting overload with relation to the target share, the number of cores is opened one by one with the existing method. The work was confirmed to be gradually carried out. The number of cores started with one. All cores were opened in 4 min and 24 s. This method requires improvement because it is ineffective in responding to more traffic requests.

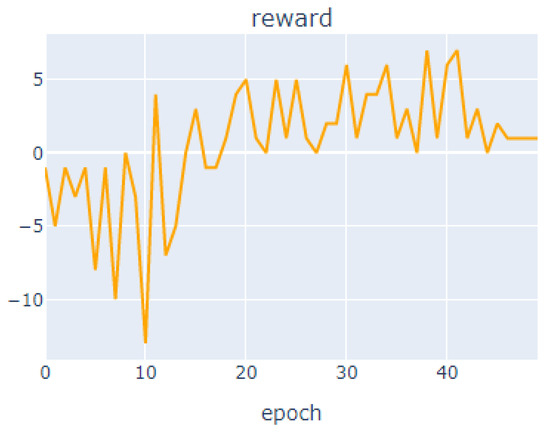

To solve this problem, in Autoscaler work equipped with AI algorithms, the DQN algorithm has been embedded in the existing HPA method to make the most of each core. The learning procedure is as follows. The input data value was set as the percentage loaded on the CPU, which is the target value. And the compensation system aimed to reduce overload by expanding the Pod as quickly as possible. The target value was reduced to a minimum, and reaching the target quickly was set as the best compensation value. To prevent the use of the core without limitation, the CPU load was continuously checked. In addition, penalties were set up to prevent unnecessary use of pods. If CPU resources are needed when opening the core, +1 point is given. If CPU resources were optimized when opening the core, −1 point is given. If it was difficult to judge, the learning was conducted by setting it to +0 point. The learning results are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Deep Q Network-based intelligent autoscaler compensation value result.

The highest value was derived from the 41st out of the 50 total number of learning, with a compensation value of 7, and overall, the compensation value is upward. The same load was given to the intelligent Autoscaler to perform simulations in a similar manner to the previous environment. The maximum number of cores was limited to 10. The time used for each core was measured. The detailed experimental results are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

DQN-based auto-scaling performance test results.

The Autoscaler equipped with AI algorithms began with one core according to the target share. CPU allocation was rapidly increased for each new experiment. Since there was an intelligent algorithm suitable for predicting overload, the Autoscaler quickly opened the cores, rather than proceeding according to the one-by-one system. It was also confirmed that the work proceeded radically. The number of cores began with one. All cores were opened in one minute and one second. This method helps stabilize the system by predicting a response to a future request according to the value loaded on the target.

Using this process, we proved that the AI Autoscaler had remarkable performance compared to the existing HPA. We also compared its performance with that of the Autoscaler equipped with concepts aiming to strengthen the Q Network process in the DQN structure.

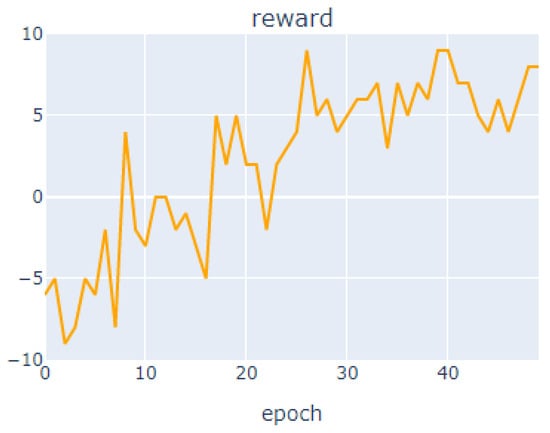

As shown in Figure 6 at the top, the highest value was derived with the compensation value 9 at the 26, 39, and 40th out of the total number of learning, and better performance was derived than before. In Autoscaler work equipped with new AI algorithms, CPU allocation increased faster than it previously did for each new experiment, starting with one core. To make the most of the cores, the response to each request was loaded to perform simulations in a manner similar to the previous environment. The maximum number of cores was also limited to 10. The time used for each core was then measured. The detailed experimental results are summarized in Table 4.

Figure 6.

Quad Q Network-based intelligent autoscaler compensation value result.

Table 4.

Improved DQN-based auto-scaling performance test results.

The Autoscaler equipped with new AI algorithms has an intelligent algorithm that is more suitable for predicting overloads. It can perform tasks by opening the cores very effectively due to its excellent prediction of performance loads. It was also confirmed that the work proceeded radically, starting with one core. All cores were opened in 59 s. This method helps stabilize the system by making more effective predictions based on the value loaded on the target.

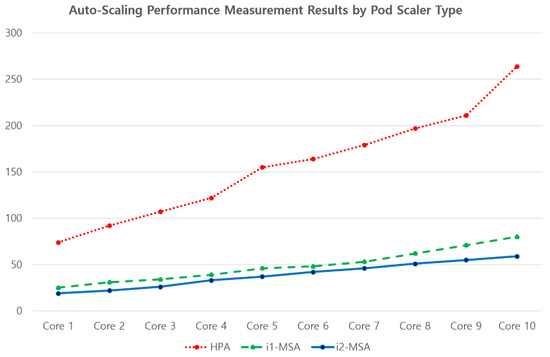

Figure 7 above depicts the Auto-Scaling Performance Measurement Results by Pod Scaler Type. The results for HPA, i1-MSA (Intelligent Autoscaler Mounted), and i2-MSA (Improved DQN Algorithm) are also shown. The performances of the Autoscalers equipped with AI algorithms were found to be significantly higher than that of HPA, with the Autoscaler equipped with the newly developed DQN algorithm showing the best performance.

Figure 7.

Auto-Scaling Performance Measurement Results by Pod Scaler Type.

5. Conclusions

With the advent of the microservice framework, auto-scaling capabilities that meet various demands have emerged as a major area of interest. Numerous expansion mechanisms have been developed. This study focused on request-based expansion, where we first investigated the performance and efficiency of core expansion for requests by mounting AI algorithms. The results of the experiments showed significant differences in throughput as well as deviations in maximum moisture from average latency. Therefore, the presence or absence of AI algorithms can affect performance. To flexibly adjust the auto-scaling settings to meet the particular requirements of a given situation, we designed RL models based on Q-learning and evaluated their applicability to learn effective scaling policies during runtime. Further, based on other algorithms with an enhanced Q Network, we showed that the proposed model could effectively and appropriately adjust the number of cores within a limited time, thereby outperforming the average throughput of the default HPA. Given these results, the presented research makes a significant contribution to existing work in the fields of both microservice frameworks and RL-based auto-scaling applications.

Based on the experimental results, we identified the following limitations of this approach: First, the maximum number of cores was limited to 10. There was no experiment investigating unexpected variables depending on the increasing load and whether it could perform better in a real-life environment that required a larger amount of traffic work. We developed the RL approach to learn core expansion policies mainly by testing the load on the target. However, it is necessary to analyze the extent to which the resource use ratio of individual components can affect performance. Therefore, there is a need for a comprehensive study to find the combination of usage levels that is capable of achieving the best possible performance in all microservices.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.K. and J.K.; Methodology, Y.K. and J.P.; Software, Y.K. and J.P.; Validation, J.P. and J.Y.; Formal analysis, J.P.; Investigation, J.Y.; Resources, J.Y. and J.K.; Data curation, J.P. and J.Y.; Writing—original draft preparation, Y.K.; Writing—review and editing, J.K. and J.Y.; Visualization, J.Y.; Supervision, J.K. and J.Y.; Project administration, J.K.; Funding acquisition, J.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was also supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (No. NRF-2021R1I1A3060565). This work was supported by Institute of Information & communications Technology Planning & Evaluation (IITP) grant funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (No. 2021-0-02068, Artificial Intelligence Innovation Hub).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Amaral, M.; Polo, J.; Carrera, D.; Mohomed, I.; Unuvar, M.; Steinder, M. Performance Evaluation of Microservices Architectures Using Containers. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE 14th International Symposium on Network Computing and Applications, Cambridge, MA, USA, 28–30 September 2015; pp. 27–34. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Kulkarni, S.G.; Ramakrishnan, K.K.; Li, D. Understanding Open Source Serverless Platforms: Design Considerations and Performance. In Proceedings of the 5th International Workshop on Serverless Computing (WOSC ’19), UC Davis, CA, USA, 9–13 December 2019; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 37–42. [Google Scholar]

- McGrath, G.; Brenner, P.R. Serverless computing: Design, implementation, and performance. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 37th International Conference on Distributed Computing Systems Workshops (ICDCSW), Atlanta, GA, USA, 5–8 June 2017; pp. 405–410. [Google Scholar]

- Akbulut, A.; Perros, H.G. Software Versioning with Microservices through the API Gateway Design Pattern. In Proceedings of the 2019 9th International Conference on Advanced Computer Information Technologies (ACIT), Ceske Budejovice, Czech Republic, 5–7 June 2019; pp. 289–292. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd, W.; Ramesh, S.; Chinthalapati, S.; Ly, L.; Pallickara, S. Serverless Computing: An Investigation of Factors Influencing Microservice Performance. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Cloud Engineering, Orlando, FL, USA, 17–20 April 2018; pp. 159–169. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Li, M.; Zhang, Y.; Ristenpart, T.; Swift, M. Peeking behind the curtains of serverless platforms. In Proceedings of the 2018 USENIX Annual Technical Conference, USENIX ATC 2018, Boston, MA, USA, 11–13 July 2020; pp. 133–145. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.; Satyam, K.; Fox, G. Evaluation of production serverless computing environments. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 11th International Conference on Cloud Computing (CLOUD), San Francisco, CA, USA, 2–7 July 2018; pp. 442–450. [Google Scholar]

- Palade, A.; Kazmi, A.; Clarke, S. An Evaluation of Open Source Serverless Computing Frameworks Support at the Edge. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE World Congress on Services (SERVICES), Milan, Italy, 8–13 July 2019; pp. 206–211. [Google Scholar]

- Tseng, F.H.; Tsai, M.S.; Tseng, C.W.; Yang, Y.T.; Liu, C.C.; Chou, L.D. A Lightweight Auto-Scaling Mechanism for Fog Computing in Industrial Applications. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2018, 14, 4529–4537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Gupta, P.; Jyoti, K.; Nayyar, A. Research on Auto-Scaling of Web Applications in Cloud: Survey, Trends and Future Directions. Scalable Comput. Pract. Exp. 2019, 20, 399–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Al-Dhuraibi, Y.; Paraiso, F.; Djarallah, N.; Merle, P. Elasticity in cloud computing: State of the art and research challenges. IEEE Trans. Serv. Comput. 2017, 11, 430–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lorido-Botran, T.; Miguel-Alonso, J.J.; Lozano, J.A. A Review of Auto-scaling Techniques for Elastic Applications in Cloud Environments. J. Grid Comput. 2014, 12, 559–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucia, S.; Somaya, J.; Niklas, K. AI-based Resource Allocation: Reinforcement Learning for Adaptive Auto-scaling in Serverless Environments. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/ACM 21st International Symposium on Cluster, Cloud and Internet Computing (CCGrid), Melbourne, Australia, 10–13 May 2021; pp. 804–811. [Google Scholar]

- Rattihalli, G.; Govindaraju, M.; Lu, H.; Tiwari, D. Exploring potential for non-disruptive vertical auto scaling and resource estimation in kubernetes. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Cloud Computing (CLOUD), Milan, Italy, 8–13 July 2019; pp. 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Dhuraibi, Y.; Paraiso, F.; Djarallah, N.; Merle, P. Autonomic Vertical Elasticity of Docker Containers with ELASTICDOCKER. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Cloud Computing, CLOUD, Honolulu, CA, USA, 25–30 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Toka, L.; Dobreff, G.; Fodor, B.; Sonkoly, B. Adaptive AI-based auto-scaling for Kubernetes. In Proceedings of the 2020 20th IEEE/ACM International Symposium on Cluster, Cloud and Internet Computing (CCGRID), Melbourne, Australia, 11–14 May 2020; pp. 599–608. [Google Scholar]

- Arabnejad, H.; Pahl, C.; Jamshidi, P.; Estrada, G. A Comparison of Reinforcement Learning Techniques for Fuzzy Cloud Auto-Scaling. In Proceedings of the 17th IEEE/ACM International Symposium on Cluster, Cloud and Grid Computing (CCGRID), Madrid, Spain, 14–17 May 2017; pp. 64–73. [Google Scholar]

- Horovitz and Arian, y. Efficient Cloud Auto-Scaling with SLA Objective Using Q-Learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE 6th International Conference on Future Internet of Things and Cloud (FiCloud), Barcelona, Spain, 6–8 August 2018; pp. 85–92. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, F.; Nardelli, M.; Cardellini, V. Horizontal and Vertical Scaling of Container-Based Applications Using Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE 12th International Conference on Cloud Computing (CLOUD), Milan, Italy, 8–13 July 2019; pp. 329–338. [Google Scholar]

- Naranjo, P.G.; Pooranian, Z.; Shamshirband, S.; Abawajy, J.H.; Conti, M. Fog over Virtualized IoT: New Opportunity for Context-Aware Networked Applications and a Case Study. Appl. Sci. 2017, 7, 1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Morabito, R.; Farris, I.; Iera, A.; Taleb, T. Evaluating performance of containerized IoT services for clustered devices at the network edge. IEEE Internet Things J. 2017, 4, 1019–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Levis, P.; Culler, D. MatÉ: A tiny virtual machine for sensor networks. SIGARCH Comput. Archit. News 2002, 30, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, F.; Fennell, L.; Schindelhauer, C.; Thiemann, P.; Ernst, G.; Haussmann, E.; Rührup, S.; Uzmi, Z.A. Optimized java binary and virtual machine for tiny motes. In International Conference on Distributed Computing in Sensor Systems; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 15–30. [Google Scholar]

- Alessandrelli, D.; Petraccay, M.; Pagano, P. T-res: Enabling reconfigurable in-network processing in iot-based wsns. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE International Conference on Distributed Computing in Sensor Systems, Cambridge, MA, USA, 20–23 May 2013; pp. 337–344. [Google Scholar]

- Gusev, A.; Ilin, D.; Nikulchev, E. The Dataset of the Experimental Evaluation of Software Components for Application Design Selection Directed by the Artificial Bee Colony Algorithm. Data 2020, 5, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez de Prado, R.; García-Galán, S.; Muñoz-Expósito, J.E.; Marchewka, A.; Ruiz-Reyes, N. Smart Containers Schedulers for Microservices Provision in Cloud-Fog-IoT Networks. Challenges and Opportunities. Sensors 2020, 20, 1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Docker. Docker Containers. Available online: https://www.docker.com/ (accessed on 4 December 2019).

- Morabito, R.; Kjallman, J.; Komu, M. Hypervisors vs. lightweight virtualization: A performance comparison. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Cloud Engineering, Tempe, AZ, USA, 9–13 March 2015; pp. 386–393. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Masfary, O.; Antonopoulos, N. Energy performance assessment of virtualization technologies using small environmental monitoring sensors. Sensors 2012, 12, 6610–6628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Mengchu, Z. Evolving Container to Unikernel for Edge Computing and Applications in Process Industry. Processes 2021, 9, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plauth, M.; Feinbube, L.; Polze, A. A performance survey of lightweight virtualization techniques. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Service-Oriented and Cloud Computing, Oslo, Norway, 27–29 September 2017; pp. 34–48. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph, C.T.; Martin, J.P.; Chandrasekaran, K.; Kandasamy, A. Fuzzy Reinforcement Learning based Microservice Allocation in Cloud Computing Environments. In Proceedings of the TENCON 2019—2019 IEEE Region 10 Conference (TENCON), Kochi, India, 17–20 October 2019; pp. 1559–1563. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B.; Li, J.; Lin, W.; Bai, W.; Li, P.; Gao, Q. K-PSO: An improved PSO-based container scheduling algorithm for big data applications. Int. J. Netw. Manag. 2020, 31, e2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, C.J.C.H. Learning from Delayed Rewards; King’s College: Cambridge, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, L. Reinforcement Learning for Robots Using Neural Networks. Ph.D. Thesis, School of Computer Science, Carnegie-Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Mnih, V.; Kavukcuoglu, K.; Silver, D.; Rusu, A.A.; Veness, J.; Bellemare, M.G.; Graves, A.; Riedmiller, M.; Fidjeland, A.K.; Ostrovski, G.; et al. Human-level control through deep reinforcement learning. Nature 2015, 518, 529–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mnih, V.; Kavukcuoglu, K.; Silver, D.; Graves, A.; Antonoglou, I.; Wierstra, D.; Riedmiller, M. Playing Atari with Deep Reinforcement Learning. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1312.5602. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Schaul, T.; Hessel, M.; Van Hasselt, H.; Lanctot, M.; De Freitas, N. Dueling Network Architectures for Deep Reinforcement Learning. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1511.06581. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton, R.S.; Barto, A.G. Introduction to Reinforcement Learning; MIT Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Xing, J.G.; Qian, S. Selectivity Enhancement in Electronic Nose Based on an Optimized DQN. Sensors 2017, 17, 2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Li, L.; Lv, Y.; Wang, F.-Y. Traffic signal timing via deep reinforcement learning. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 2016, 3, 247–254. [Google Scholar]

- Genders, W.; Razavi, S. Using a deep reinforcement learning agent for traffic signal control. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1611.01142. [Google Scholar]

- Hasselt, H.V.; Guez, A.; Silver, D. Deep reinforcement learning with double q-learning. In Proceedings of the Thirtieth AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, Phoenix, AZ, USA, 12–17 February 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hessel, M.; Modayil, J.; van Hasselt, H.; Schaul, T.; Ostrovski, G.; Dabney, W.; Horgan, D.; Piot, B.; Azar, M.; Silver, D. Rainbow: Combining improvements in deep reinforcement learning. In Proceedings of the Thirty-Second AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, San Francisco, CA, USA, 2–7 February 2017. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).