1. Introduction

The European shipbuilding industry nowadays already faces competition from the Far East in a shipbuilding niche of passenger and cruise vessels and special purpose ships. Furthermore, it also faces the problem of the extremely high share of the shipping industry in terms of the rates of environmental pollution through greenhouse gas emissions and noise as a threat to living beings in waters [

1]. Therefore, the shipyard is expected to find solutions to build safe, energy-efficient and environmentally acceptable vessels with high operational and maintenance autonomy (Smart ships) constructed in a sustainable business environment [

2]. The market niches that the European shipbuilding industry is oriented to mostly have a demand for individual vessels or smaller serials of vessels, which additionally emphasises the shipbuilding company’s profitability risks concerning the high complexity of the shipbuilding process, the high ratio of working hours in the cost structure of the process and the high portion of working capital [

3]. The subjected challenges to competitiveness point to the necessity for improving shipyard’s production process [

4], management process [

5], as well as developing technical–technological solutions during a vessel’s design phase, thereby defining the efficient shipbuilding technological process [

6]. Adopting Industry 4.0 doctrines is part of the strategy that most countries with a tradition and influence in the shipbuilding and maritime industrial sector in general have taken on [

2], knowing that the digital technologies, development, research and innovation, are recognised as the most efficient tools for maintaining and, as expected, improving the competitiveness of the shipbuilding business systems [

3]. Some of the previous research has defined and recognised Artificial Intelligence (AI), the Cloud, Big Data analytics (BDA) and the Internet of Things (IoT) as leading technologies in transforming traditional shipyards into Smart businesses, i.e., Shipyard 4.0 [

3], while, for example, a Shipyard 4.0 case study by the Navantia shipyard in Spain emphasises Digital Twin or “ship zero” as the axis of the shipyard’s digital transformation [

7].

Digital Twin was initially introduced through the concept of monitoring the life cycle of the product (“Product Lifecycle Management”) and defined by joining three “entities”, i.e., (i) the physical product, (ii) its virtual equivalent and (iii) its data link (which actually represents digital technology, i.e., IT components) [

8,

9], which can be, according to its original definition, considered as “Digital Twin technology”, the core technology in realising Cyber-Physical Space [

10]. Digital Twin, as a common notion, represents the virtual replica of the product, process, manufacturing system [

11,

12,

13], object and other physical entities; such a replica is, with various sensors and software applications, connected to the physical entity, and with the data collected, it monitors the physical entity’s performance parameters in real time throughout the entire lifecycle [

10,

14,

15].

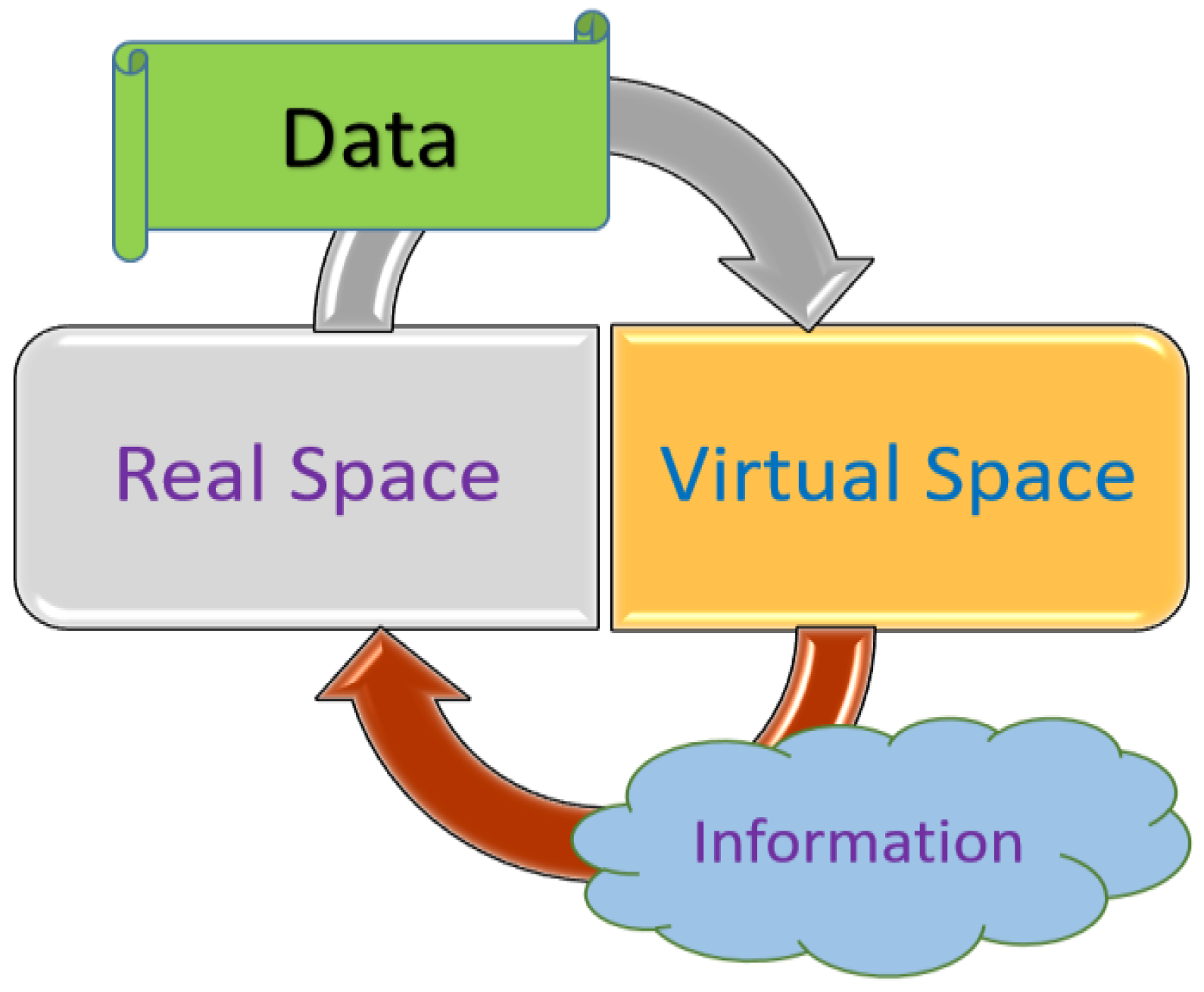

Figure 1 shows the Digital Twin conceptual model.

A Digital Twin is either created as the replica of the already realised physical entity [

16] or is developed along with the entity’s design process by using 3D modelling technology [

17]. In this study, the authors approached 3D modelling of the entity as the development of its Digital Twin, the same as has occurred in other researches on the topic of Digital Twin implementation in the shipbuilding processes [

1,

15].

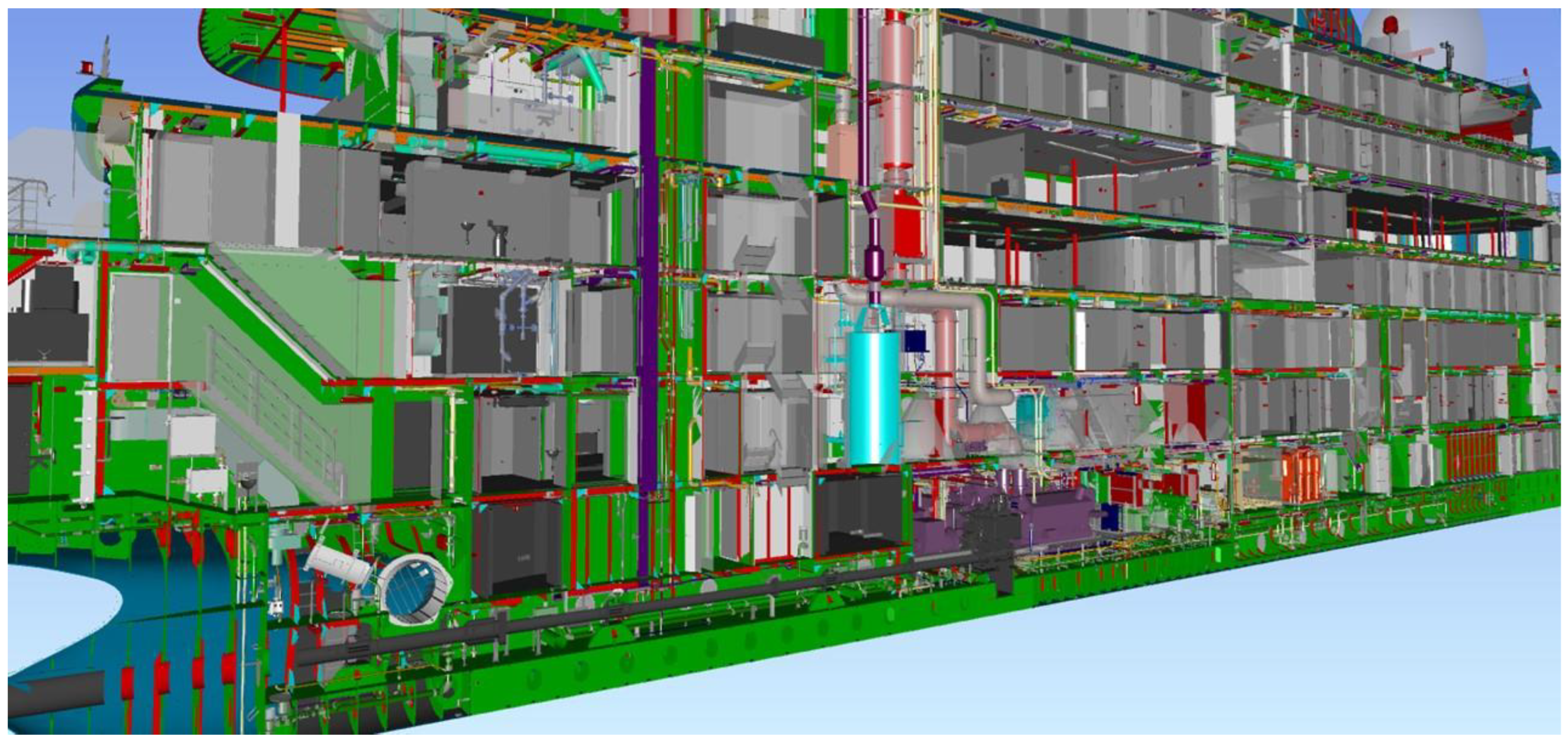

Modern software applications enable 3D modelling from the early beginnings of an entity’s development, i.e., the initial design phase, as well as interconnectivity with various software modules such as Assembly Planning or Material Planning, all as a prerequisite for prototyping the vessel in Digital Twin form and content; such a 3D model, i.e., Virtual Reality (VR), with the future upgrade to Augmented Reality (AR), enables all stakeholders involved (horizontal integration [

3,

7]) to define the best possible technical–technological solutions aiming to optimise the construction, exploitation and decommissioning of the entity [

9,

18]. A further precondition for creating a Digital Twin is the existence of an appropriate IT communication infrastructure (digital thread) that enables uninterrupted data flow, i.e., managing the same when integrating the virtual and real surroundings [

19,

20].

Due to the lack of quantitative research related to the improvements in shipbuilding processes by implementing digital technologies, and with accepting the thesis of Digital Twin’s primary importance of its role in Shipyard 4.0 [

7], including to the marketing and sales activities [

18], the main interest of this research is aimed towards the analysis of the impact of Digital Twin’s implementation to productivity in the process and contribution to the green transformation of the shipbuilding system.

Furthermore, there are very few analyses and researches considering the advanced outfitting in shipbuilding [

21]: very few discuss the approach of shipyards in different market niches towards outfitting activities’ distribution through the shipbuilding process [

22,

23,

24], whereby only a few investigate the potential advantages of implementing advanced outfitting in the earlier stages of ship construction, though they have analysed only a particular type of new builds [

25]. Following the subject gap that is shown after reviewing the literature, the main purpose of this study is to further research the eventual accomplishments in terms of the shipbuilding processes’ cost deductions by improving the advanced outfitting in the shipbuilding system within the market niche of cruises, i.e., passenger vessels.

Shipyards in general are looking to improve their competitiveness primarily by reducing supply and labour costs as well as construction time; in that respect, the advanced outfitting could offer a significant reduction in the number of man-hours engaged for the outfitting activities, as well as a decrease in the various types of costs, such as insurance, financing, energy, consumables and sickness leave. That being said, the authors’ intention is to respond, through this research, to the following questions:

Q1: Does the outfitting of new builds in earlier stages of construction improve the competitiveness of the shipbuilding system acting in the niche of passenger ships, i.e., cruise vessels?

Q2: Does the 3D modelling of the vessel in the Digital Twin form and content enable a larger scope of outfitting activities to be performed in earlier stages of construction?

The methodology of the research is based on a case study, i.e., the collection of statistical and empirical data gathered by one European shipyard, investigating distinctions in the realization of two new build projects considering the building duration between main events, the total number of man-hours spent on welding and outfitting activities, the electric energy consumption, as well as the injury frequency and severity rates; the basic difference in the realisation of subject vessels is that one is designed and built by using a 3D model but in the Digital Twin form and content.

This paper presents the improvements achieved through implementing Digital Twin in the shipbuilding process of the observed shipyard due to the accomplishment of outfitting activities at a higher magnitude within the early stages of ship building. The article contributes scientifically through the aim of initiating the additional awareness of scholars and industry professionals considering the benefits of advanced outfitting applied at the highest applicable level at earlier stages of the shipbuilding project realization process, and thereby of the importance of its constant improvement. As a novelty, this study introduces Digital Twin (in the concept as accepted by authors) as the tool of the advanced outfitting improvement.

The stages of the Digital Twin ship observed for the purpose of this research were limited to those developed simultaneously with the design and construction processes of the physical entity, as described by Gierin et al. [

1], until the delivery of the vessel. Therefore, in order to avoid any doubt, the 3D ship model was not utilised as the Digital Twin, as it is commonly known, and in any case, it could not have been due to the fact that the vessel was not outfitted with sensors, actuators and related software tools that would enable data exchange between the physical entity and its virtual replica during the sea trials, operation and maintenance of the vessels. Nevertheless, data flow between the physical entity and its digital prototype during the construction process was bi-directional and not one-way in terms of the type of communication, i.e., the level of integration that refers to Digital Shadow and not Digital Twin [

16,

26]. Namely, the status of the entity’s outfitting spaces were reported by the production and technology departments on a daily basis, also for the purpose of ensuring eventual changes in the 3D model’s design were achieved in a timely manner, thereby avoiding potential repair activities that could occur due to, e.g., changes in the outfit caused either because of obstacles in supply or because of the client’s modifications.

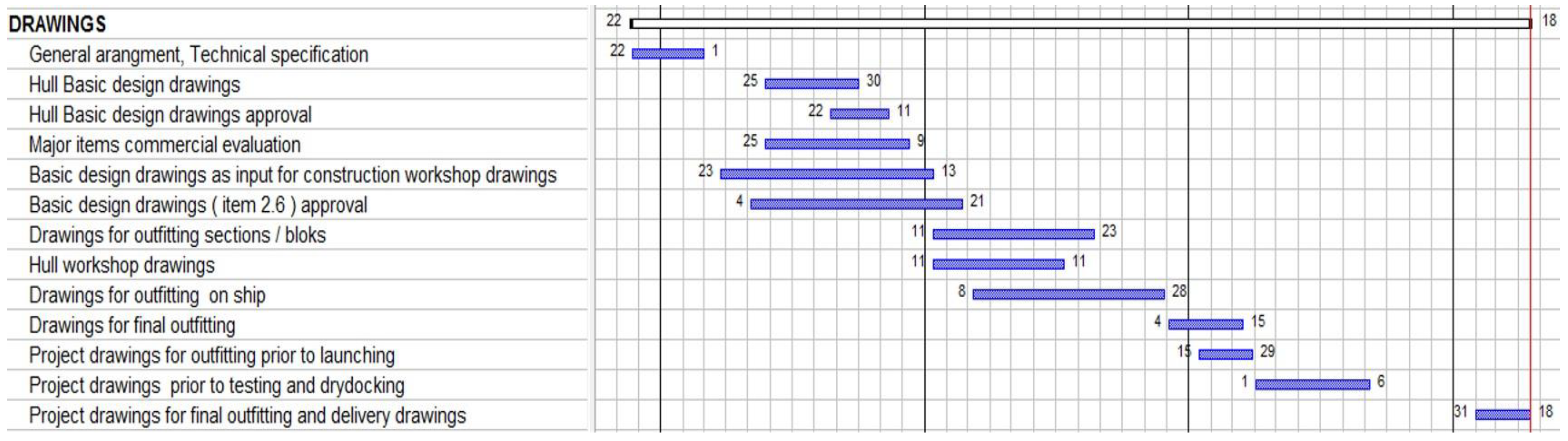

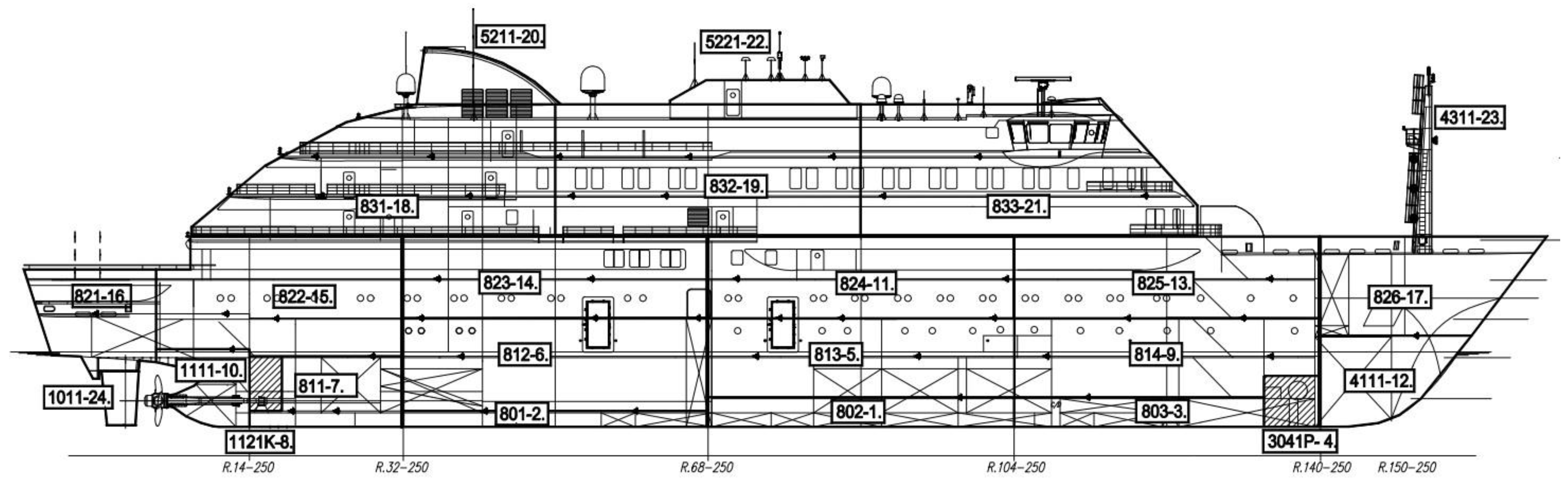

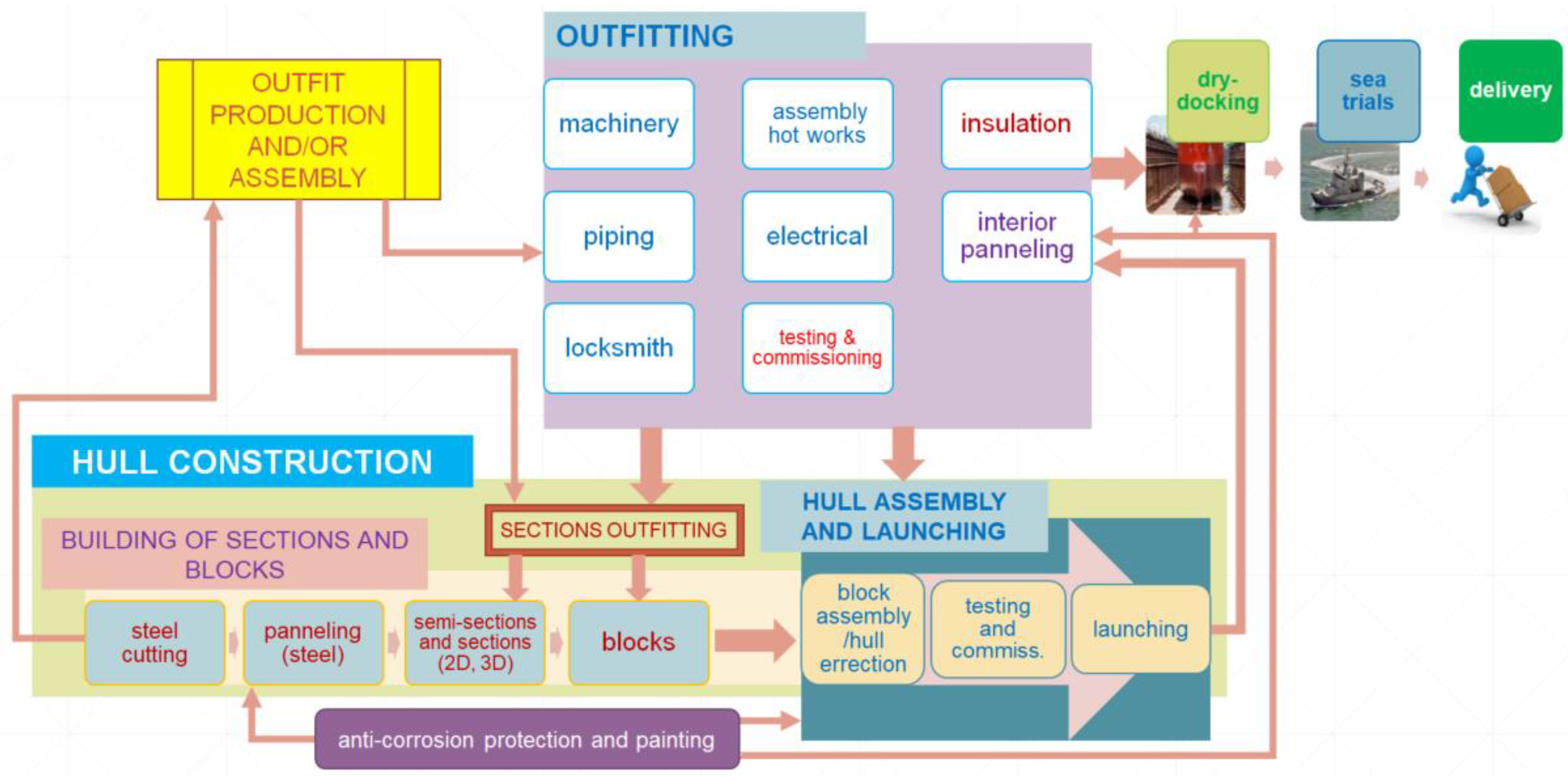

In the first part of this paper (second chapter), the realisation process of the shipbuilding projects in the observed shipyard is presented, with an explanation of the applicable shipbuilding and outfitting technologies. Furthermore, in the third chapter, the concept of advanced outfitting is explained, along with the impact on the shipyard’s production process. The fourth chapter describes the development of the Digital Twin and its contribution to increasing the scope of the advanced outfitting in relation to the scope of the outfitting after launching. Improvements achieved in the shipbuilding process by implementing the Digital Twin are presented and discussed through the fifth chapter. The sixth chapter, i.e., the conclusion, is dedicated to the findings and suggestions for further development, i.e., the research of Digital Twin’s implementation through the shipbuilding project’s realisation process.

3. Advanced Outfitting

According to the practical information of some international shipyards and professional literature sources, the work–cost ratio for the identical outfitting activity, depending on the shipbuilding construction stage where outfitting is implemented, varies from 1:3:5:7 [

23] (the cost of the specific outfitting activity performance for the on-block outfitting is three times higher than the cost of the same outfitting activity performed in the workshop or at the pre-assembly line, five times higher in outfitting on the berth, i.e., slipway (on-board outfitting), and seven times higher in outfitting on board after launching) up to 1:3:7:11 [

25].

Due to the increase in closed outfitting spaces, the access to the assembly position is harder, more overhead work is required, more additional and repair work occurs, and overlapping of the special outfitting professions and their systems’ routes (piping—cable trays—ventilation channels—exhausts, and the like) increases causing additional correction activities and new repairs; consequently, an increased number of working hours results in an increase in energy consumption for the work equipment and machinery.

Furthermore, the more closed spaces there are, and the simultaneous performance of different outfitting activities there are within the same, result in a much higher necessity for temporary illumination and ventilation, which are significant electric energy consumers. Therefore, shipyards continuously strive to decrease the number of outfitting activities after launching, in favour of increasing the number of outfitting activities at the earliest possible stage of the shipbuilding process [

25]. Even though outfitting in the early phases of the ship’s construction requires a higher level of planning, and workshop and technological documentation preparation, resulting in a longer design period and therefore a later start of steel cutting, it is expected for a shorter ship construction period to be achieved, thereby keeping the same or even shortening the ship’s delivery term, all accomplished with a lower number of outfitting working hours [

23,

24,

25].

However, some international shipyards recognise the benefits of advanced outfitting, mostly when building cargo vessels, with a ratio of realised savings of 1:3:8 (three times more cost for the same on-block outfitting activity than for the workshop or pre-assembly workshop outfitting, and eight times more for on-board outfitting); in the construction of cruise vessels, due to the large interior surfaces (passenger cabins, public spaces, ship crew area), and due to the strong involvement of the subcontractors (usually a „turnkey“ contract deal), some shipyards prefer to keep the brunt of the outfitting on board, mostly because of a less complicated transfer of responsibility between the shipyard and subcontractors following the work completion phase progress [

24]. The last especially refers to assembly-type shipyards. Furthermore, some naval shipyard producers redirect even more of the focus of the outfitting activities into the construction phase while the ship is on the berth, or even to a larger extent to the phase after launching. The reason for that, according to their assertions, is the complexity of the naval vessel systems (much higher quantity of pipes, ten times longer electric cables and complex arming systems) and the necessity for a longer stay on the outfitting quay due to the complex inspections and testing of the outfit and ship systems in the sea [

24].

Advanced outfitting generally refers to installing the elements of a certain vessel’s system into the outfit assembly or the complete outfit block assembly (including flooring, ladders, railings and more—mostly applicable to engine room components), which is, later on during the shipbuilding process, installed into a 2D section, a larger erected section or into a ship (on the berth or after launching); the sanitary (wet) module and passenger cabin module or the crew cabin module are also considered as part of the outfit block assembly. Furthermore, advanced outfitting refers to installing the outfit assemblies and outfit block assemblies, machines, piping, electrical components and other ship equipment into 2D sections and larger erected sections, all before being lifted onto the slipway. The last refers to installing the outfit assemblies and outfit block assemblies, machines, piping, electrical components and other ship outfits into the ship while on the slipway or after launching [

24]. Advanced outfitting in relation to the shipbuilding stages is presented in

Figure 5.

Along with the previously mentioned advantages of advanced outfitting, further advantages are the reduced need for temporary ventilation and illumination, scaffolding and vertical transport. Advanced outfitting also engages more low-skilled workers, enabling the better redistribution of high-profile skilled workers within the production process. Advanced outfitting reduces the danger of work injuries, upgrades the working culture and raises adherence to working instructions and procedures, resulting in a higher-quality product.

5. Results and Discussion

As the result of the outfitting activities being performed in earlier stages of the cruise vessel’s construction, particularly during the blocks erection (on-block outfitting phase), the analysis of the collected data (

Table 3) shows a significant reduction in the number of working hours for outfitting, up to 30%, depending on the profession. There are about 10% savings in the total number of ship outfitting working hours on average. It can be noticed that the research results show no improvement in reducing the number of working hours for piping assembly; on the contrary, an increase of almost 18% occurred. The reason is that pipe assembly works were a focus of advanced outfitting from the very beginning of the development and the application of the subject technological approach in question to the shipbuilding process, regardless of the production program of the shipyard [

24]. Hence, the scope of advanced outfitting with the piping components has increased throughout history and is perfected in performance. However, the application of a virtual ship model, today in Digital Twin form, achieves a significant reduction in the consumption of working hours to eliminate errors in assembly, both in pipe assembly activities and all other outfitting professions, with an emphasis on locksmith work—or a 90% improvement—all as a result of redirecting the activities of advanced outfitting towards the blocks erection phase. Empirical and statistical data of the observed shipyard indicate that, today, it completes approximately 70% of the total ship outfitting in the phase of construction before lifting blocks onto the slipway, with a tendency for further growth, compared to the indicators before applying the 3D ship model in the form of a digital prototype—approximately 31% in the construction of a cargo vessel [

23], or an average of 40% (Europe) up to 50% (Japan) in the construction of a cruise vessel [

24].

Separating welding devices for the MIG procedure, along with the ventilation and lighting equipment required for outfitting space working conditions, as the significant consumers of electrical energy (statistic indicators of the shipyard), the consumption of electrical energy during the outfitting process and shipbuilding process (EEC

DT) can be defined by the following equation and based on the selected indicators:

where

V stands for the ship space total volume,

WH the total welding hours, K

arc the coefficient of effective welding work of the electric arc,

PWA the welding machine electric power,

PLBL the electric power of illumination required to illuminate 1 m

3 of outfitting space within the block erection stage,

PFBL the power of ventilation devices required for the defined air exchange within 1 m

3 in the outfitting space in the block erection phase,

DBL the duration of the on-block outfitting process, K

NBBL the coefficient of parallel block outfitting in their erection phase,

PLBO the illumination electric power required to illuminate 1 m

3 of outfitting ship space after launching,

PFBO the electric power of ventilation devices required for the defined air exchange in 1 m

3 of ship space after launching, and

DBO the duration of on-board outfitting after launching. Two coefficients are defined related to engaging devices providing temporary energy during the performance of outfitting activities on board after launching: K

IBO, the empirically assessed coefficient of outfitting intensity according to the scope of activities of related technological outfitting phases and K

CBO, an empirically assessed coefficient of the ship spaces according to the complexity of the outfitting works.

According to (1), during the cruise ship outfitting and building, and concerning the consumers surveyed by this research, electrical energy was consumed according to the following:

According to (2), electrical energy consumption during the outfitting process and shipbuilding process (EECDT) equalled 4,469,804.08 kWh.

If the cruise vessel project had been realised without the use of a digital ship prototype, the electrical energy consumption (EEC), analysed by the same consumers as in (1), would be calculated according to the following:

where R

PV is the coefficient of welding hours spent according to the CGT of the passenger vessel,

CGTCV the compensated gross tonnage of the cruise vessel,

DBLPV the on-block outfitting duration according to its share in the overall outfitting and construction duration of the passenger vessel, and

DBOPV the duration of on-board outfitting according to its share in the total duration of the process of outfitting and building a passenger vessel.

According to (3), EEC would be:

According to (4), if the cruise vessel project had been realized without the implementation of a 3D model in the form of Digital Twin, electrical energy consumption would have equalled 6,082,058.23 kWh

The difference in electrical energy consumption (ΔEEC) resulting in the parallel “construction” of a digital ship prototype is as follows:

which makes a difference in consumption of 1,612,254.15 kWh, representing 20% electrical energy savings only in relation to the analysis of part of the direct energy consumption through the building of the observed ship [

29].

Although research on the human role in the Smart Factory environment is in its infancy [

30] and, in fact, analyses of the impact of Industry 4.0 technologies on occupational safety and health are yet to come [

31], designing and building a ship prototype in a virtual surrounding enables the defining of technology for outfitting by performing the same work to a high degree of completion within more favourable working conditions, e.g., open outfitting spaces with a much higher share of continuous natural ventilation and natural light and thus a low level of temporary energy “obstacles” (cables, ventilation ducts), and avoiding overhead work, which ultimately results in an approximately 43% reduction in the incidence of injuries at work, with almost five times fewer severe injuries at work (

Table 4).

6. Conclusions

Current trends in the maritime market define sustainability as a major factor in competitiveness, with demands on energy-efficient and environmentally friendly vessels manufactured in the same environment. Today’s shipbuilding industry is focused on the growing presence of research, development and innovation activities in its business for the purposes of technical and technological improvements in the production process, aiming to achieve cost reductions and energy savings, and having available the digital technologies of Industry 4.0 as appropriate tools above all.

This research presents the importance of 3D modelling in a virtual environment by comparing the process of building and outfitting a passenger vessel and a cruise vessel in the observed shipyard. The research analysis is focused on a change in the number of working hours engaged for the outfitting activities and a change in the electric energy consumption during the shipbuilding process. Designing and building a ship in parallel through its 3D model in the Digital Twin form allowed ship outfitting in the earlier stages of construction up to a level of approximately 70%, which improved the productivity in the project realisation process by approximately 20%. Furthermore, 20% savings in electrical energy consumption were achieved only in relation to the scope of this research, thus reducing CO2 emissions by 1140 t over two years. Additionally to that, as the result of advanced outfitting improvement, the injury frequency rate decreased by about 43% and the injury severity rate reduced by five times.

Even though quantitative analysis of the savings considering the vessel’s insurance, fire and safety protection as well as financing costs were not included in this research, their significance are presumed; therefore, further study of this subject is recommended.

Although the proportion of errors in assembly activities was significantly reduced, from 50% to as much as 90%, depending on the outfitting profession, further improvements are possible by applying Augmented Reality (AR), in which direction further research is proposed to be performed. Furthermore, based on the realised savings in the number of outfitting working hours, it is assumed that the duration of the project realisation process is shortened; following that, this research should be expanded in order to define the method of process duration determination while considering the expected extension of the preparatory (design) phase. Additionally, this paper does not consider the impact of the need for earlier outfit procurement regarding the usual construction intervals between the main events (milestones) and the associated contractual payment schedule; therefore, the authors propose further analysis to adjust cash flow to meet outfitting dynamics.

This study targets in particular shipbuilding systems with cruise vessel, naval and/or mega-yacht new build programs because in the majority of shipyards within the subject market niche, outfitting activities are performed in the later stages of the building process, mainly on board on the berth/slipway or even after launching. One of the reasons for the division of such outfitting activities is either because of the complexity of piping and electrical systems, as well as the commissioning program at the quay (navy vessels), the large number of modifications in outfitting (mega-yachts) or the high ratio of subcontracted works on a turnkey basis (cruise vessels). Moreover, due to the afore mentioned payment schedule that is contractually commonly applied, i.e., 5 times 20%, whereby the instalment distribution is in relation to the main events, shipyards are aiming to reach the steel cutting milestone, as well as the keel laying and launching events, as early as possible, with an increase in savings (man-hours, energy, etc.) that could be achieved by implementing advanced outfitting in the earlier stages of ship construction, particularly during the sections and blocks erection. Therefore, this paper addresses and intends to contribute to the shipbuilding industry in general, irrespective of the chosen market niche(s).