Abstract

The development of an appropriate ontology model is usually a hard task. One of the main issues is that ontology developers usually concentrate on classes and neglect the role of properties. This paper analyzes the role of an appropriate property set in providing multi-purpose ontology models with a high level of re-usability in different areas. In this paper, novel quality metrics related to property components are introduced and a conversion method is presented to map the base ontology into models for software development. The benefits of the proposed quality metrics and the usability of the proposed conversion methods are demonstrated by examples from the field of knowledge modeling.

1. Introduction

Ontology as a subfield of knowledge engineering is used for explicit standardized conceptualization of certain problem domains [1]. Ontology frameworks provide tools for semantic modelling and reasoning. Ontologies are increasingly used in various fields, such as knowledge management, information extraction, and the semantic web [2].

Ontology models can be implemented at different levels. Upper ontology [3] covers general concepts used in many application areas. Terms such as thing, human, and task refer to upper ontology entries. Domain ontology [4], on the other hand, involves specific concepts used in only a few application domains.

In the classic approach of Noy and McGuinness [5], an ontology can be used to:

- enable a shared understanding of the information structure;

- enable information reuse in applications;

- apply ontological structures at different stages of IS development, such as analysis, conceptualization, and design.

Nowadays, ontologies can be used as the main tool of automatized process control in many flexible environments.

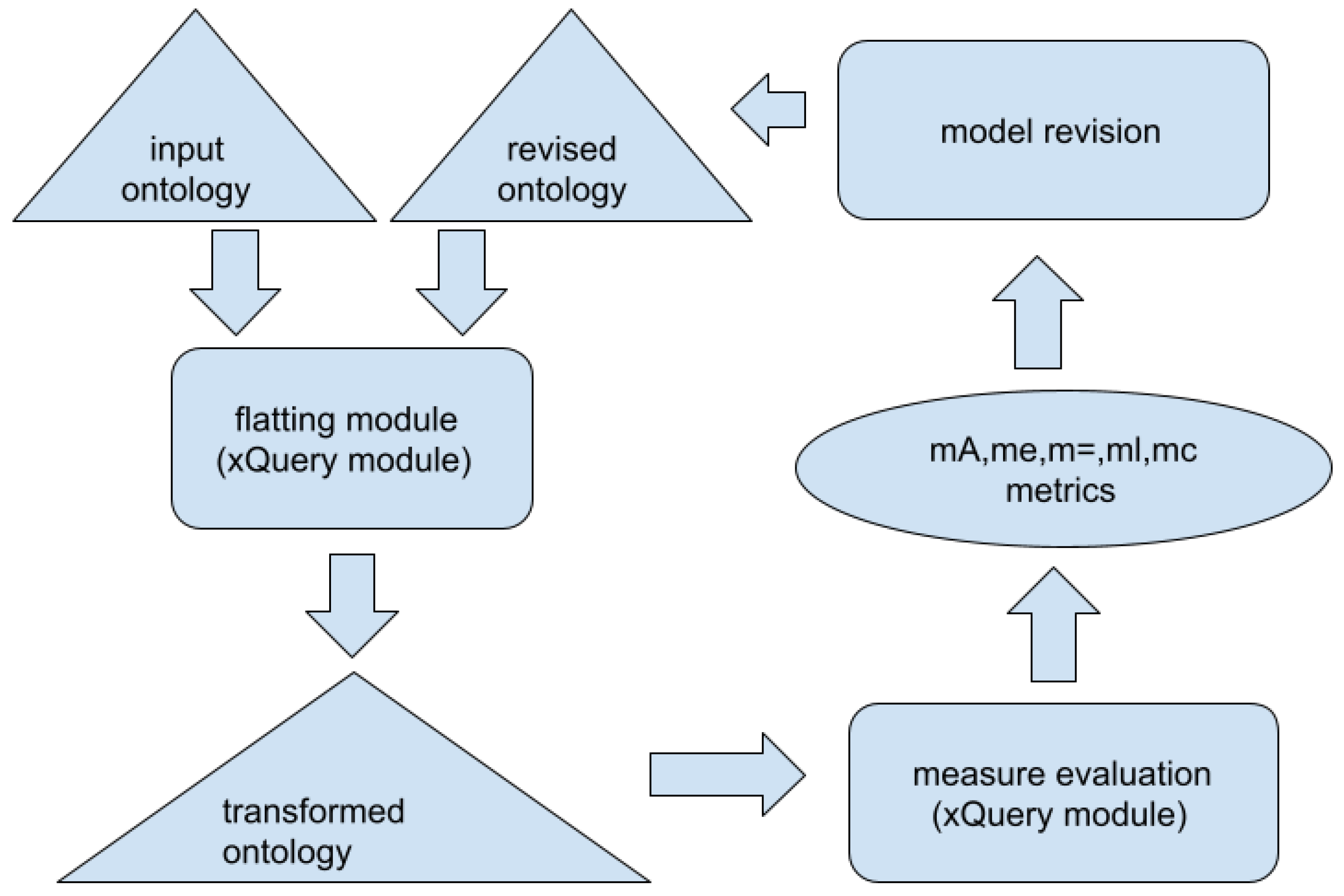

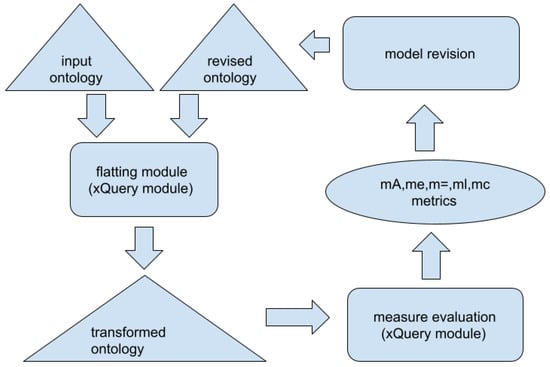

For many reasons, the development of an appropriate ontology model is usually a hard task. Many efforts have been directed to the creation of methodologies for guiding users in the development of ontologies. Methodological tools such as On-To-Knowledge [6] can help users to build ontologies from scratch. One issue during ontology development is the selection of appropriate components (classes and properties) [7]. By considering many ontology examples, it can be seen that authors usually concentrate on the class level. On the other hand, in other semantic modeling languages, such as the UML model or concept lattices, the attributes and properties play a key role in model structure. Our main motivation here is to show that only an appropriate set of related concepts and properties can provide a high level of interoperability and reusability in the created ontology models. To help designers use an appropriate set of properties, we introduce novel quality metrics based on property measures of the ontology models. In addition to a formal analysis, we present a methodology and program framework to perform the required transformation and calculations. The architecture of the developed framework is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Architecture of the evaluation framework.

In this paper, we first provide an overview of related ontology quality metrics and compare them with other dominant modeling approaches used in knowledge and software engineering. After a survey of related works, we introduce the formal model of the property-oriented ontology representation. This section presents five novel property-based quality metrics. The next section focuses on developing algorithms for metric calculation, and provides the implementation details of the methods. In the last section, we present test experiments on the ontology evaluation using the proposed methods.

2. Related Work

To manage the methodological gap between ontology and modeling schema, the DOGMA model [8] introduces a double articulation ontology model. The ontology has two main components: ontology base and ontology commitments. The ontology base contains the standard concept level model elements such as taxonomy and concept assertions. The second component is used to describe the domain-specific ontology rules. These rules can be used to determine the available properties and domain specific integrity constraints.

Considering the practical guidelines for ontology development, a design pattern-oriented method was proposed in [9]. The proposed modular design approach includes the following six main design patterns, covering the different key aspects of the ontology:

- Structural pattern,

- Syntactic pattern,

- Content pattern,

- Presentation pattern,

- Consideration pattern.

Considering the area of Software Engineering (SE) in general, there is a rich literature on the application of ontology tools in SE processes. One of the first proposals on ontology support [10] focused on the software quality issues. The main reason for the importance of ontology tools in SE is that experience shows lack of domain knowledge [11] to be a very risky situation in the software development process. The excellent survey of Ruiz and Hilera [12] presents all the important achievements of this research field. Their survey shows that the whole area of software development and software technology is involved in the development of ontology-based model extensions.

In the majority of proposals, a separate domain ontology model is constructed covering the specific SE development phases. The constructed and validated ontology models are mapped manually or partially automatically into SE models. With regard to automatic mapping, the work of Bures [13] presents a method for code generation directly through a high-level and detailed ontology specification, resulting in good consistency of the generated code. A similar approach is presented in [14]; an ontology-oriented programming method is proposed in which the specification of a problem solution is expressed in the form of an ontology. Regarding the semi-automated integration approaches, the constructed ontology model can be used to generate standard SE design models. For example, in [15], the UML document was extended with annotations generated from the related ontology.

There have been proposals in the literature focusing on special schema-oriented extensions of the base ontology model. In [16], the conflicts caused by multiple inheritance were investigated in detail, with a a semi-automatic approach proposed to deal with such conflicts. The work of [17] highlighted the importance of integrating OOP concepts with standard knowledge engineering approaches. Based on these considerations, we focus here on the integration of ontological and schematic approaches. The goal of our work is to investigate the feasibility of a property-based ontology approach.

An important related modeling approach is the field of Formal Concept Analysis (FCA). FCA [18,19] provides tools to manage and investigate concept sets generated from an input formal context. A formal context is defined as a triplet , where I is a binary relation between G (a set of objects) and T (a set of attributes); is met if and only if the attribute is true for the object . Two derivation operators are introduced as mappings between the powersets of G and T. For ,

For a context , a formal concept is defined as a pair for which the following conditions are met:

- .

An important aspect in FCA is the fact that a concept is defined as a pair of related object and attribute sets. Thus, every concept is uniquely identified in its context by the corresponding object set or attribute set. Here, we note that the objects in FCA are the atoms in the concept lattice, i.e., they correspond to the individuals in the ontology model. Considering these attributes, we can generally consider them as predicates having true or false Boolean values. In this sense, FCA attributes may correspond to property–value pairs in ontology. Thus, as schematic models highlight the viewpoint that attributes (predicates, properties) are the key elements in identifying the concepts, in FCA the attributes must be first-order members of semantic models.

One of the first models integrating ontology and FCA methods was presented in [20]. Their proposed model was based on the following principles:

- Concepts are described by their properties;

- The concept hierarchy is determined by the properties;

- The same property sets mean the same concepts.

The construction of ahn ontology is controlled and supported by a corresponding concept lattice. Every ontology can be mapped to a unique context and FCA concept lattice. The ontology design tool can perform the following supporting actions:

- Visualization of the related FCA concept lattice;

- If two concepts are assigned to the same property set, an error message can be raised to modify the ontology;

- After selecting a set of properties, a new related concept is generated, the system determines its position in the taxonomy graph, and the new concept is inserted into the current concept lattice.

A similar integration approach was presented in [21] for constructing an ontology to describe the semantics of business actions. The target ontology was constructed in a distributed way by integrating local component descriptions. The input component models describe the relevant properties of the actions, then the integration module coverts them into concepts using the FCA engine.

In the proposal presented in [22], an FCA concept lattice based on property relationships was constructed to determine the taxonomy of the ontology classes. Each class was associated with the FCA concept having the largest number of shared properties.

Regarding applied cases, one of the first publications was the development of a clinical domain ontology [23]. This ontology was generated from a set of 368 textual patient discharge reports using natural language preprocessing modules to convert texts into terms and attributes. Later, several other application studies on ontology construction with FCA support were worked out, among others, in the fields of tourism [24] and naval operations [25].

Another important approach is the combination of direct rule-based languages with FCA to construct domain ontologies [26]. Rule-based language can be used to enrich an ontology with additional relationships and axioms [27].

Ontology is an actively investigated research domain. Considering recent works, we highlight the following fields:

- Integration of ontology into smart systems, such as e-tutor systems [28,29]

- Application of ontology-based tools in schematic modeling [30]

- Integration of ontology and machine learning methods [31]

- Ontology in knowledge mining [32].

Due to the complexity of ontological modeling and to the strong relationship and inference with other semantic modeling tools, there is a need to provide objective measures of the quality of ontological modeling and schema. In the literature, there are works analysing the requirements [33,34]; however, there is no general and widely accepted theoretical and technical foundation for the synthesis of these requirements. Thus, the development of efficient tools to support modeling of ontologies remains a real and relevant research topic in the knowledge engineering community. With regard to approaches proposed in the literature, it is apparent that the proposed metrics focus mainly on the structure of class relationships, and to an extent cover the distribution of instances [20].

Summarizing the previous works, we can highlight the following challenges:

- There is a need for better integration of different semantic modelling tools;

- The integration of ontology and OOP methods is an important problem domain;

- Ontology quality measures should be adapted to the special requirements of ontology–OOP model integration.

In the next section, an analysis of ontology quality metrics is presented; we then introduce a novel attribute-oriented ontology modeling approach that provides a set of related metrics.

3. Ontology Modeling and Quality Measures

3.1. Quality Metrics

There are many quality requirements of ontology models that should be considered during the ontology construction process. On the other hand, from the viewpoint of practical applications, better support for quality ontology development is a key factor in the desired success of the ontology model.

Considering the difficulties in practical ontology modeling, the following factors can be emphasized:

- Many developers come from the database domain, where a closed-world approach is the dominant model. In contrast, the ontology model uses an open-world approach, and explicit additional axioms must be created to provide a more suitable view.

- An ontology should cover a wide range of concepts, and global ontologies are usually constructed by many partial (domain-specific) ontology models having different granularity and functionality. Due to the large size of ontology models, an automatic integration tool that can discover hidden inconsistencies is usually required.

- Subjectivity., i.e., there are no golden rules and guidelines for ontology design, and there exist different approaches to ontology development (e.g., both inductive and deductive approaches [35], resulting in very different ontology models for the same domain).

- In many OOP models, the main relationship between classes is the specialization relationship. Child classes inherit the properties of the parent class automatically. In ontology modeling, the declaration of a domain axiom on a property does not mean an automatic inheritance; a separate subclass axiom must be added to the corresponding ontology.

In the next sections, we provide an overview of research results related to ontology quality. A common approach is to adapt the standard software quality metrics to ontology [35]. For example, [36] proposed following quality aspects: syntactic quality, semantic quality, pragmatic quality, and social quality. Considering the different approaches in the literature, we can categorize the ontology-specific quality aspects into the following three main areas [34,37]:

- schema and type definitions;

- the amount and the resolution of the data;

- clarity, compatibility, and usability.

Unfortunately, it is a difficult task to construct a common set of metrics which objectively describe all aspects of ontology quality. In the next section, we present the most commonly used examples, which generally emphasize important properties of the ontology.

3.1.1. Structural Measures

As ontology models are implemented using graphs, various authors have introduced metrics to measure the complexity and quality of the graph structure. The main aspects within structural metrics cover, among others, the balancing and density (richness) measures of the graph.

Using the notation of the formal ontology model presented in [37], the ontology O is provided by

where:

- C: the set of concepts;

- P: the set of relations;

- A: the set of properties;

- : concept taxonomy;

- : , which relates concepts non-taxonomically, that is, every property may have domain and range axioms;

- : , which relates concepts with literal values.

In the literature [37], the following quality measures are used for ontology evaluations:

- Relation Richness: where denotes the set of subclass relationships. An ontology that contains many relations other than class–subclass relations is richer than a taxonomy with only class–subclass relationships.

- Property Richness: It is assumed that as more properties are assigned to classes, more information can be conveyed in the ontology model.

- Inheritance Richness: , which is defined as the average number of subclasses per class.

- Class Richness: This value shows the ratio of the number of classes that have instances and the total number of classes.

- Average Population: where I is the number of instances; this shows the average number of instances for a class.

- Cohesion: This can be defined as the number of disjoint components of the ontology graph; a value of 1 signifies strong cohesion.

- Importance of a Class: This metric shows the importance of a class as the number of instances that belong to the subtree rooted at compared to the total number of instances.

- Fullness: The fullness of a class is defined as the actual number of instances that belong to the subtree rooted at compared to the expected number of instances under the subtree.

- Inheritance Richness: This shows the average number of subclasses per class in the subtree related to .

- Connectivity: This metric is defined for a class as the number of instances of other classes that are connected to instances of .

An alternative set of graph-oriented quality metrics has been proposed by [38], including the following heuristic elements:

- Number of objects: the number of individuals belonging to a class;

- Number of properties: the number of predicates belonging to a class;

- Number of children: the number of subclasses;

- Number of parents: the number of superclasses;

- Depth of inheritance tree: the length of the longest path in the covered subgraph;

- Centrality measure: how far the depth of the class is from the average depth of all classes;

- Density measure: the number of related classes.

As can be seen, these metrics are quantitative metrics against the schema of the ontology. The quality may relate to the integrity aspects of the ontology as well. A schema can be considered a low quality one when it contains a large number of conflicts [39]. This model distinguishes the following integrity measures:

- property assertion conflicts;

- class assertion conflicts;

- statement assertion conflicts.

Methods for checking integrity can be extended to the instance level as well [40].

3.1.2. Usability Metrics

The usability factor can be investigated from many different aspects. The usual categorization involves the following elements:

- Human aspects, i.e., the readability and understandability of the ontology;

- Compatibility aspects, i.e., are the instances derived from the same schema definition compatible with each others or not;

- Technical aspects, that is, applicability of the ontology must be measured considering the available software tools.

In [35], the following practical measures were proposed to evaluate the quality of ontology models:

- Computational efficiency (the size of the model);

- Adaptability (involving cohesion and coupling);

- Clarity (unambiguous naming);

- Accuracy (which shows the agreement between the constructed model and expert knowledge about the domain);

- Completeness (all relevant information is covered by the ontology model);

- Consistency (the ontology does not include or allow for any contradictions).

3.2. Key Issues in Ontology Design

Regarding the approaches proposed in the literature, it can be seen that the proposed metrics focus mainly on the structure of class relationships, and to an extent cover the distribution of the instances. In [20], it is stated that ontology design usually starts and stops with designing taxonomy. Our motivation here is to show that the properties or attributes are important factors of ontology quality. The attributes play an important role in data and knowledge modeling, as they convey the concrete data values, while classes can be considered as containers of the related attributes. The correctness of a data model is based primarily on the correct structure of the attributes. The proposed model to enhance the role of properties in ontologies is based on the adoption of a conceptual description following Formal Concept Analysis (FCA) for ontology modeling.

4. Property-Based Ontology Representation

4.1. Formal Model

In this section, we introduce a property-based ontology description approach for OWL ontologies. The input ontology model is provided by

where

- : the set of concepts;

- : the set of individuals;

- : the concept taxonomy relationship (acyclic);

- : the set of properties, where denotes the value set of property p; The properties can be used as follows:

- -

- in individual assertion triplets , in which case the value of p is equal to v and ;

- -

- in class axioms of the following forms:

- ∗

- p domain c ( or )

- ∗

- ∗

where the symbol v denotes the value of property p;

- : type assignment to the individuals.

Starting with the input ontology, the first step is to generate the related set of base properties, where every property–value pair found in the ontology corresponds to a base attribute:

We can extend the attribute set with generalization of the property values:

For an arbitrary and , the symbol is true if individual i meets property a. The attribute notation is true only if, for some value v, that property is met. In this case, the value of the property is not important.

In the next step, we introduce a new attribute property mapping:

where

The set corresponds to the intent set of the formal concepts in FCA. In order to determine the sets, we perform a sequence of specialization and generalization steps. In the case of specialization, the properties of parent concepts are inferred to the lower levels, that is, to the descendant concepts. The explicit specialization process is based on property-oriented class axioms in the ontology. Having an axiom or , we can conclude that

If , then

is met as well. The specialization process terminates when all of the individuals are processed. Thus, an updated set is obtained for every individual. The result is a context in which the objects correspond to the individuals. A row related to individual i contains the elements of .

As an example, let us take the following ontology fragment:

<DataPropertyAssertion>

<DataProperty IRI=‘‘#color’’/>

<NamedIndividual IRI=‘‘#chair1’’/>

<Literal datatypeIRI=‘‘PlainLiteral’’>brown</Literal>

</DataPropertyAssertion>

<DataPropertyAssertion>

<DataProperty IRI=‘‘#age’’/>

<NamedIndividual IRI=‘‘#peter1’’/>

<Literal datatypeIRI=‘‘integer’’>12</Literal>

</DataPropertyAssertion>

<DataPropertyAssertion>

<DataProperty IRI=‘‘#name’’/>

<NamedIndividual IRI=‘‘#peter1’’/>

<Literal datatypeIRI=‘‘PlainLiteral’’>Peter</Literal>

</DataPropertyAssertion>

<DataPropertyAssertion>

<DataProperty IRI=‘‘#age’’/>

<NamedIndividual IRI=‘‘#employee1’’/>

<Literal datatypeIRI=‘‘PlainLiteral’’>old</Literal>

</DataPropertyAssertion>

<DataPropertyAssertion>

<DataProperty IRI=‘‘#name’’/>

<NamedIndividual IRI=‘‘#employee1’’/>

<Literal datatypeIRI=‘‘PlainLiteral’’>Tom</Literal>

</DataPropertyAssertion>

<DataPropertyAssertion>

<DataProperty IRI=‘‘#age’’/>

<NamedIndividual IRI=‘‘#dog1’’/>

<Literal datatypeIRI=‘‘PlainLiteral’’>old</Literal>

</DataPropertyAssertion>

The related property set contains the following elements:

- = (#color, braun)

- = (#age, 12)

- = (#name, Peter)

- = (#age, old)

- = (#name, Tom).

The generated context table is shown in Table 1:

Table 1.

T1: Generated context table.

During the generalization process, we apply the following rule borrowed from the closed world assumption: if an attribute a is valid for every child concept of c, then the attribute is valid for c. This approach is used in FCA modeling as well, among others. In the generalization step, the attribute sets of the concepts are updated, starting with the individuals. For a concept c, the set of related attributes is calculated in the following way:

In the intersection operation, we use the following value level generalization step. If we have two attributes related to the same property (p) that have different values, we construct an attribute . This attribute means that the item has a property p with any value.

We distinguish two domain sets for any attribute a:

- declared domains

- inferred domains

A concept c is an element of the inferred domain of attribute a if

We assume that both domain sets contain the ⊤ concept as well, i.e., and . The domain set is equal to the union of the declared and inferred domains

After constructing the attribute sets for every concept and individual, the following consistency check can be performed:

- For every concept, the attribute set cannot be empty, i.e.,

- Different concepts must have different attribute sets, i.e.,

- Domain axioms of the form ’’ are assigned only to those concepts c which meet the condition that every individual or concept having the given attribute are subconcepts of c : .

If the generated ontology would hurt these rules, then the ontology design expert must update and improve the initial ontology. These rules ensure that the every concept has a corresponding and unique attribute set similar to the FCA approach.

4.2. Property-Based Metrics

The property-oriented ontology model provides an opportunity to introduce specific property-based quality metrics for ontologies. The main principle is that the property distribution in the taxonomy must be well balanced and consistent. To measure this quality, we propose the following measures:

- : the relative number of the properties. If the value is lower (near or below 1), there are too few properties. If the number is too high, most of the properties are not used in the taxonomy construction.

- : the ratio of concepts with empty local (not inherited) property sets. From the viewpoint of FCA, if this value is greater than 0, then the ontology is invalid.

- : the ratio of concepts having non-unique properties set. From the viewpoint of FCA, if this value is greater than 0, then the ontology is invalid.

- . This measures shows the average length of the local (not empty) property sets. A high value means that many attributes are not relevant in the taxonomy construction.

- : This value shows the total distance between the declared and inferred domain concepts. The distance function is defined as the length of the shortest path in taxonomy graph between the elements. In the best case, is equal to 0.

As an example, we compare two schema descriptions; the first is an ontology oriented model, while the second is example of the UML-OOP model.

In this example, we first take a sample ontology found on the internet [41]. For the sake of simplicity, we use only the following concept taxonomy fragment:

Person

Employee

Professor

AssistantProfessor

AssociateProfessor

Lecturer

Assistant

Student

UndergraduateStudent

GraduateStudent

Organization

EducationOrganization

Department

Program

Course

Seminar

The list of related properties in the ontology, where the first argument denotes the declared domain and the second argument, is the range parameter.

advisor(Student, Professor)

affiliateOf(Organization, Person)

affiliatedOrganization(Organization, Organization)

alumnus(Organization, Person)

emailAddress(Person, .STRING)

head(Organization, Person)

listedCourse(Program, Course)

name(Person, .STRING)

takesCourse(Student, Course)

teacherOf(Department, Course)

The ontology schema does not contain any individual declarations; thus, the set contains only the ⊤ concept for every attribute a. The proposed metrics have the following values for this sample ontology:

- .

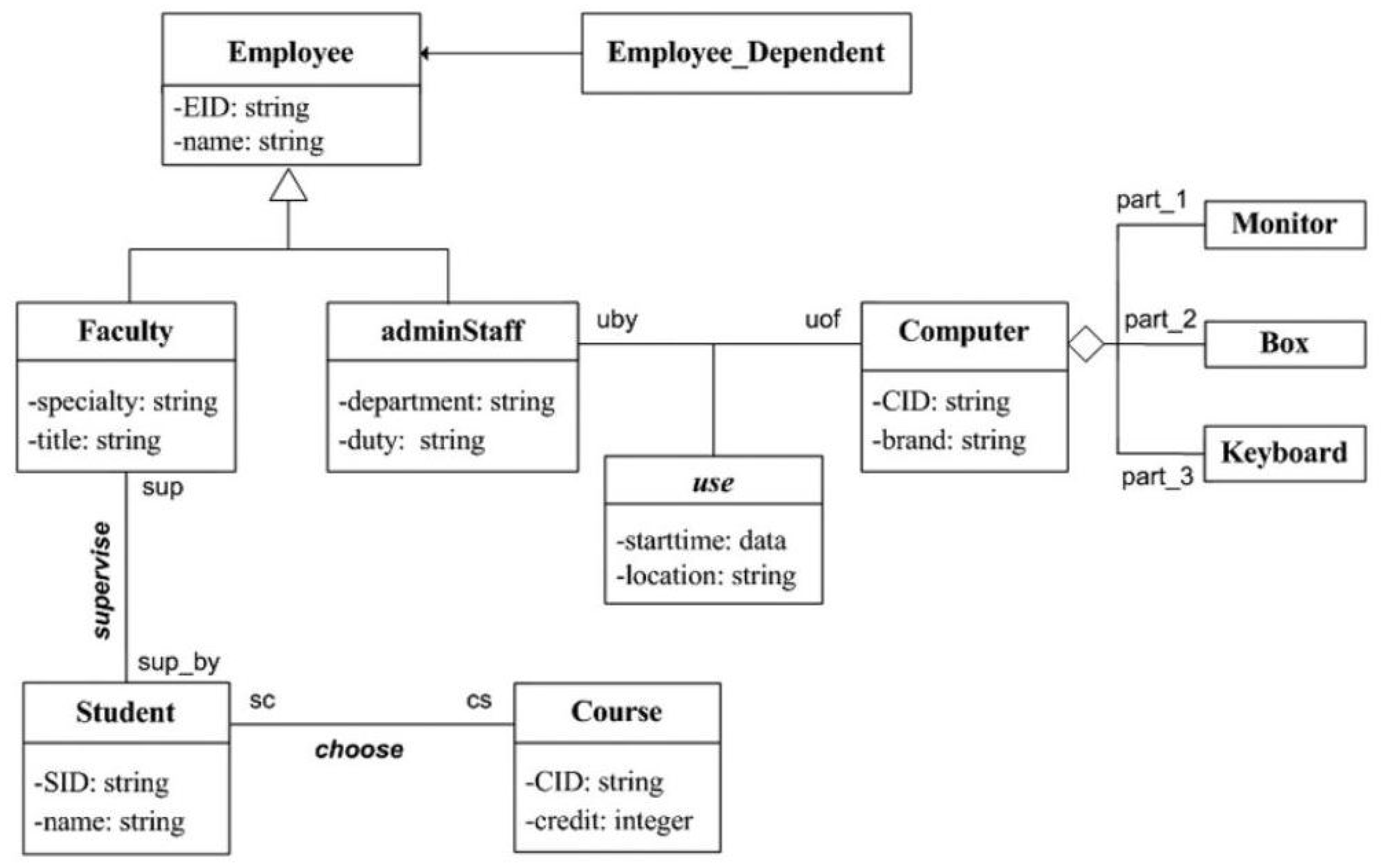

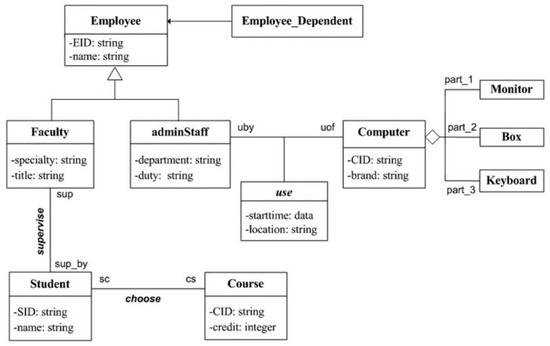

The second example schema is the UML class diagram presented in Figure 2. If we consider this UML diagram as an ontology model, we have the following metric values:

Figure 2.

UML class diagram of a university (source: [42]).

- .

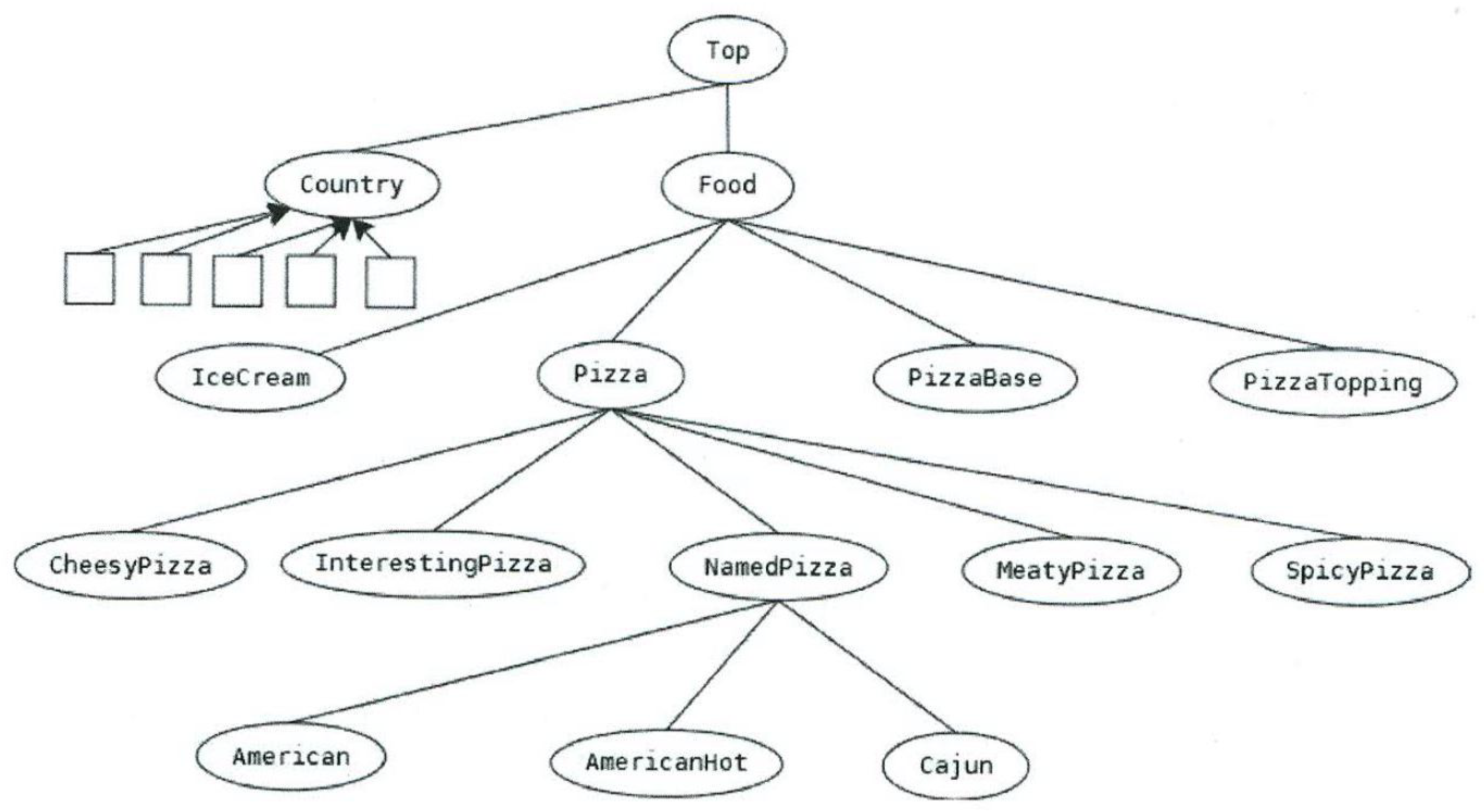

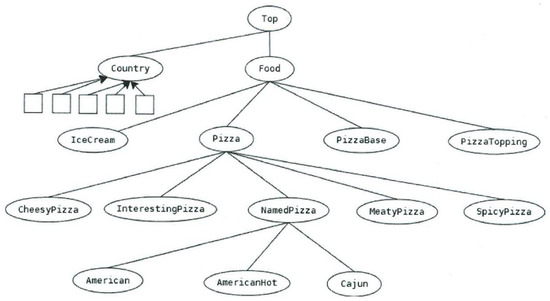

The third example is the standard pizza ontology [43] presented in Figure 3. The presented reduced ontology contains only fourteen concepts, while the depth of the taxonomy hierarchy is 4. The ontology contains three properties. The first step of ontology processing is to generate the corresponding properties. In this reduced ontology, fifteen attributes were generated from the properties. In the specialization process, eight concepts were extended with inherited attributes (the most widely used derived attribute is ’hasBase some PizzaBase’). In the subsequent generalization phase, the ’NamedPizza’ concept is extended with three new attributes. The resulted ontology can be characterized by the following measures:

Figure 3.

Fragment of the pizza ontology [43].

The fourth example is a large-scale Java project, the source code of the Apache Jena framework (http://jena.apache.org/, (accessed on 26 October 2022). The framework contains 5881 Java source files. We have implemented a class analyzer application using the Reflection API to extract the class definitions. We identified 6264 classes for further analysis. The class/data member/method structure is considered here as a concept/attribute structure. In the processing method, the following simplifications were implemented:

- The data types and signatures in attributes and methods are ignored;

- All attributes and methods are assumed to be public;

- The embedded classes are ignored.

From all source files, we extracted the following data:

- name: fully qualified name of the Java class

- attributes: attribute names

- methods: method names

- parent: name and package of the parent class

- implements: list of interfaces which has implemented in the given class.

The names of the classes are not necessary unique; therefore, it is necessary to consider the fully qualified names of the classes. The main characteristic parameters of the Jena Apache framework source code is summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Metric values.

The attribute-level quality of the Apache Jena framework can be provided by the following parameters:

4.3. Property Relevance

The investigation of attribute relevance is a standard method in data mining, especially in the classification domain, where the correlation between the attribute and the target variable determines the importance of the attribute [44]. The relevance ordering of the attributes can be used, among others, in data reduction or data representation. If we consider the FCA approach, we can see that in FCA every attribute has the same importance, and all possible formal concepts are contained in the generated concept sets. In practical applications, only a small subset of concepts is used and recognized. The selected concepts have a larger practical importance, however. This simplified concept model is represented in the semantic models constructed for the application programs; thus, the generated schema should express the relevance value of the involved concepts. Applying this idea to the constructed ontologies, we can introduce an importance measure for the attributes and properties.

In FSA, for every attribute a there exists a concept c, where

This concept meets the condition

This concept is the unique suprenum of attribute a. In ontology or other schema modeling, this concept c may be missing. In this case, attribute a may be less important than the attributes with a unique suprenum in the ontology.

Based on this consideration, for a property p in the ontology we can define the relevance factor as

Symbol means that the property part of a is equal to p. This measure shows how far the suprenum concepts of a are from the optimal position. In the best case, the suprenum of every attributes related to p is the child node of the top element. In this model, a lower value means a higher importance.

Here, we take the properties defined in the reduced pizza ontology (Section 4.2). Based on the generated property-oriented ontology representation, we obtain the following relevance values:

- hasCountryOfOrigin,

- -

- : hasCountryOfOrigin value America,

- hasBase,

- -

- : hasBase some PizzaBase,

- hasTopping,

- -

- : hasTopping some FruitTopping,

- -

- : hasTopping some CheeseTopping,

- -

- : hasTopping some ⊤,

- -

- : hasTopping some MeatTopping,

- -

- : hasTopping some MozzarellaTopping,

- -

- : hasTopping some PeperoniSausageTopping,

- -

- : hasTopping some TomatoTopping,

- -

- : hasTopping some HotGreenPepperTopping,

- -

- : hasTopping some JalapenoPepperTopping,

- -

- : hasTopping some OnionTopping,

- -

- : hasTopping some PrawnsTopping,

- -

- : hasTopping some TobascoPepperSouceTopping,

- -

- : hasTopping some SpicyTopping,

Based on calculations, the property hasBase has the largest importance in the presented example ontology. The property hasTopping has a relatively high importance as well, while hasCountryOfOrigin is a property with low importance.

5. Implementation and Evaluation Tests

The program framework constructed to analyse OWL XML documents contains three program modules. The first module is the flattening unit, which converts the input OWL/XML desription into a simplified XML format. The second program unit calculates the property oriented metrics related to the simplified ontology document. The third unit can be used to generate the extended closed-world oriented view of the input ontology.

5.1. Flatting Module

The schema-oriented ontology view focuses on only two main aspects of the ontology model: the property–object relationship and the specialization–generalization relationship. In this modeling approach, the other ontology elements do not play a direct key role. To extract the relevant elements, we perform a preprocessing step that generates a simplified representation of the input ontology. This flattening process converts the complex structures into a set of simple structures. The resulting description contains:

- Spezialization relations (SubClassOf, ClasssAssertion)

- Property-based relations (ObjectSomeValuesFrom, DataSomeValuesFrom, ObjectAllValuesFrom, DataAllValuesFrom, DataPropertyAssertion).

The flattening process introduces temporal classes to substitute for complex class expressions. The transformation process generates new concepts for these constructional expressions. Then, all occurrences of the complex expression are replaced with a reference to the corresponding new concept. This substitution step can be used to reduce the depth of the global ontology. The transformation rules implemented in the flattening process are summarized in Table 3 and Table 4.

Table 3.

Transformation rules used in preprocessing.

Table 4.

Transformation rules used in prepocessing.

The conversion program manipulates the ontology description on the base XML level. The transformation module was developed in the XQuery language using the eXist-db exist-db.org/exist/apps/homepage/index.html development framework. The XQuery language provides a number of important features for efficient management of XML documents, including XPath-based data selection, control flow of functional programming, and data updating. The code snippet in List (Section 5.1) presents the conversion code fragment used for processing the element ObjectInverseOf.

(: ObjectInverseOf :)

for $c in $output_doc//ObjectInverseOf

let $p := $c/ObjectProperty/@IRI/string()

let $pu:= concat(‘‘Inv_’’,$p)

return (

update replace $c with <ObjectProperty IRI=‘‘{$pu}’’ />

,

if ( not ($output_doc//Declaration/ObjectProperty[@IR/string() = $pu ]))

then

update insert <Declaration> <ObjectProperty IRI=‘‘{$pu}’’/>

</Declaration> into $output_doc

else ()

)

The conversion program builds a simplified ontology description containing no complex class expressions and no data type expressions. The program eliminates all irrelevant information items from the initial ontology description. An example (Section 5.1) demonstrates the flattening process on a simplified input ontology. The ontology fragment contains, among others, the important class constructor elements (ObjectIntersectionOf; ObjectAllValuesFrom; ObjectUnionOf; ObjectInverseOf; DataSomeValuesFrom). In this list, we omit the usual Declaration elements in order to keep the list short.

The flattening module generates the input format for ontology metric evaluation. It can be considered as a preparation module that performs many transformation steps in order to provide efficient metric evaluation. The main benefits of the flattening process are as follows:

- Eliminating of irrelevant ontology components;

- Direct supporting the proposed metrics;

- Explicit representation of derived concepts;

- Lower execution cost in metric calculations.

<Ontology>

<DataPropertyDomain>

<DataProperty IRI=‘‘#hasAge’’/>

<Class IRI=‘‘#Human’’/>

</DataPropertyDomain>

<SubClassOf>

<Class IRI=‘‘/pizza.owl#Capricciosa’’/>

<ObjectAllValuesFrom>

<ObjectInverseOf>

<ObjectProperty IRI=‘‘/pizza.owl#hasTopping’’/>

</ObjectInverseOf>

<ObjectUnionOf>

<Class IRI=‘‘/pizza.owl#AnchoviesTopping’’/>

<Class IRI=‘‘/pizza.owl#CaperTopping’’/>

</ObjectUnionOf>

</ObjectAllValuesFrom>

</SubClassOf>

<EquivalentClasses>

<Class IRI=‘‘#Teenager’’/>

<ObjectIntersectionOf>

<Class IRI=‘‘#Person’’/>

<DataSomeValuesFrom>

<DataProperty IRI=‘‘#hasAge’’/>

<DatatypeRestriction>

<Datatype abbreviatedIRI=‘‘xsd:integer’’/>

<FacetRestriction facet=‘‘XMLSchema#maxExclusive’’>

<Literal datatypeIRI=‘‘XMLSchema#integer’’>20</Literal>

</FacetRestriction>

<FacetRestriction facet=‘‘XMLSchema#minExclusive’’>

<Literal datatypeIRI=‘‘XMLSchema#integer’’>12</Literal>

</FacetRestriction>

</DatatypeRestriction>

</DataSomeValuesFrom>

</ObjectIntersectionOf>

</EquivalentClasses>

</Ontology>

The resulting flattened form contains the following elements:

Ontology>

<SubClassOf>

<Class IRI=‘‘/pizza.owl#Capricciosa’’/>

<ObjectSomeValuesFrom>

<ObjectProperty IRI=‘‘Inv_/pizza.owl#hasTopping’’/>

<Class IRI=‘‘1’’/>

</ObjectSomeValuesFrom>

</SubClassOf>

<Declaration>

<ObjectProperty IRI=‘‘Inv_/pizza.owl#hasTopping’’/>

</Declaration>

<Declaration>

<Class IRI=‘‘1’’/>

</Declaration>

<SubClassOf>

<Class IRI=‘‘#Teenager’’/>

<Class IRI=‘‘#Person’’/>

</SubClassOf>

<SubClassOf>

<Class IRI=‘‘#Teenager’’/>

<DataSomeValuesFrom>

<DataProperty IRI=‘‘#hasAge’’/>

<Datatype IRI=‘‘dt_1’’/>

</DataSomeValuesFrom>

</SubClassOf>

<SubClassOf>

<Class IRI=‘‘#Teenager’’/>

<Class IRI=‘‘#Human’’/>

</SubClassOf>

</Ontology>

5.2. Ontology Evaluation

The ontology evaluation module takes the simplified ontology XML file as input and generates the following output items:

- attribute set;

- context for CL construction

- metric values.

The module was implemented in XQuery language. The algorithm of the evaluation module is summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Transformation rules used in the evaluation process.

After obtaining the specialization graph, the engine performs both the attribute specialization and attribute generalization processes. The specialization process uses the following inference rule:

The reverse process, generalization, uses the following rule:

During the generalization process, we introduce a new attribute to denote that the class has a property p with an arbitrary value. The resulting description for the input data introduced in the example (Section 5.1) is presented in the next example (Section 5.2). The objects for the FCA context are provided in the classes subtree, with the corresponding attributes listed in the <attr> element. The metric values are shown under the <metrics> element.

<result>

<classes>

<Class IRI=‘‘/pizza.owl#Capricciosa’’ type=‘‘c’’ id=‘‘1’’ depth=‘‘1’’>

<attr><a nn=‘‘Inv_/pizza.owl#hasTopping:1’’>1</a></attr>

<parent/><children/></Class>

<Class IRI=‘‘/pizza.owl#AnchoviesTopping’’ type=’’c’’ id=‘‘2’’ depth=‘‘1’’>

<attr/><parent/><children/></Class>

<Class IRI=‘‘/pizza.owl#CaperTopping’’ type=‘‘c’’ id=‘‘3’’ depth=‘‘1’’>

<attr/><parent/><children/></Class>

<Class IRI=‘‘#Teenager’’ type=’’c‘‘ id=‘‘4’’ depth=‘‘2’’>

<attr><a nn=‘‘#hasAge:dt_1’’>3</a></attr>

<parent><c>5</c><c>6</c></parent><children/></Class>

<Class IRI=‘‘#Person’’ type=‘‘c’’ id=‘‘5’’ depth=‘‘1’’>

<attr><a m=‘‘u’’ nn=‘‘#hasAge:dt_1’’>3</a></attr>

<parent/><children><c>4</c></children></Class>

<Class IRI=‘‘#Human’’ type=‘‘c’’ id=‘‘6’’ depth=‘‘1’’>

<attr><a m=‘‘u’’ nn=‘‘#hasAge:dt_1’’>3</a></attr>

<parent/><children><c>4</c></children></Class>

<Class IRI=‘‘1’’ type=‘‘c’’ id=‘‘7’’ depth=‘‘1’’>

<attr/><parent/><children/></Class>

</classes>

<attributes>

<Attrib id=‘‘1’’>Inv_/pizza.owl#hasTopping:1</Attrib>

<Attrib id=‘‘2’’>Inv_/pizza.owl#hasTopping:*</Attrib>

<Attrib id=‘‘3’’>#hasAge:dt_1</Attrib>

<Attrib id=‘‘4’’>#hasAge:*</Attrib>

</attributes>

<metrics>

<m_a>0.285714285714285714</m_a>

<m_em>0.714285714285714286</m_em>

<m_eq>0.428571428571428571</m_eq>

<m_l>0.571428571428571429</m_l>

<m_c>0</m_c>

</metrics>

</result>

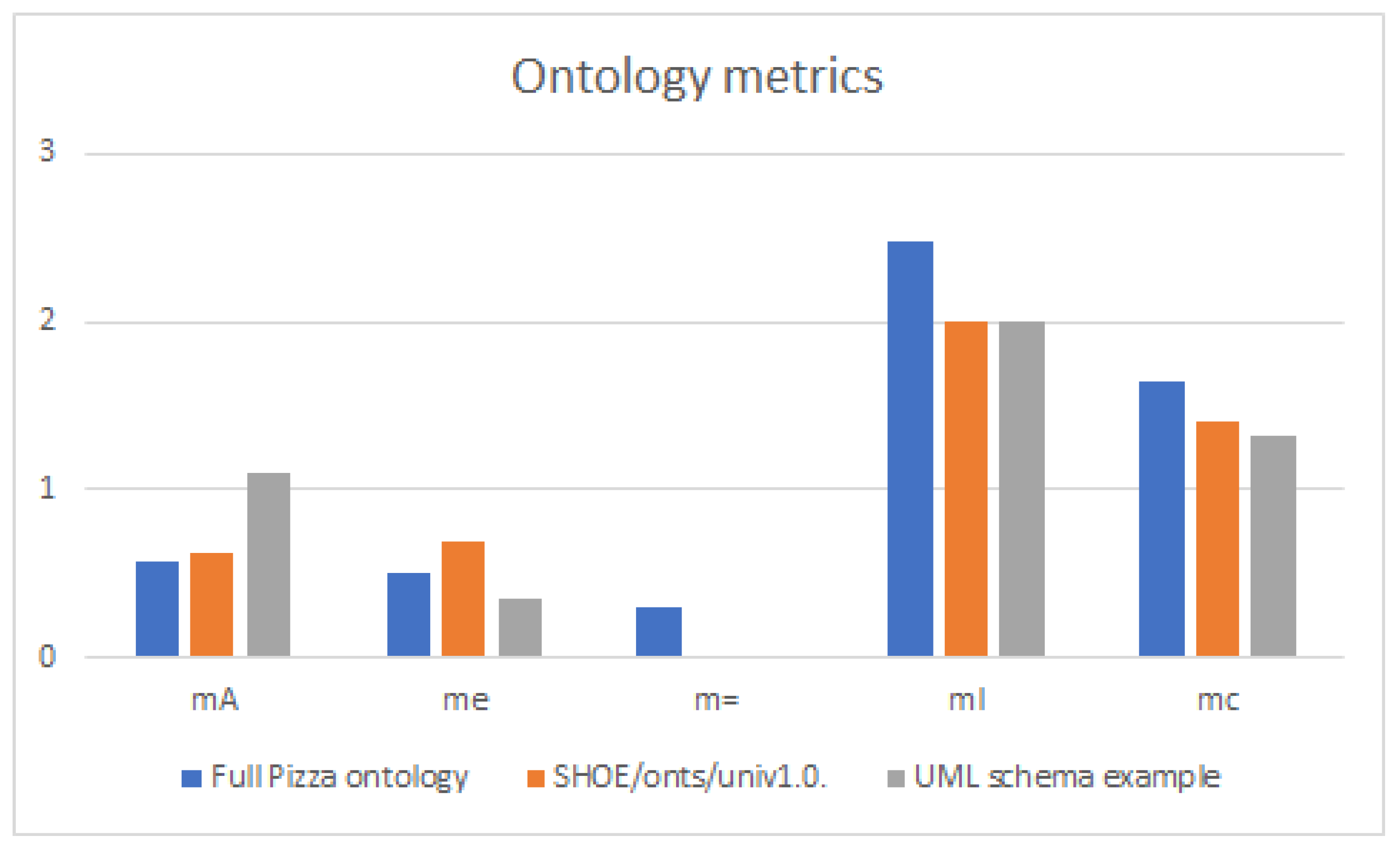

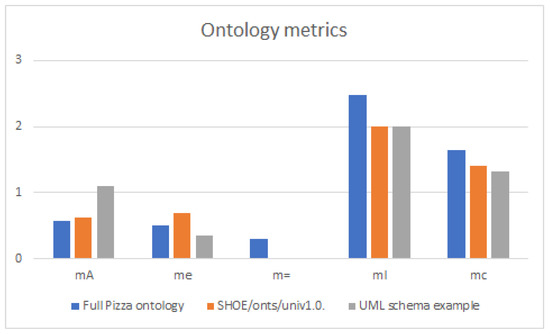

In the experimental phase, we test a number of freely available online ontology sources for metric comparison. The test results are summarized in Figure 4 and Table 6.

Figure 4.

Ontology metrics diagram.

Table 6.

Ontology metrics.

Based on the test results, the evaluation of the tested ontology models can be summarized as follows:

- (1)

- Regarding the parameter, the best value is for the UML schema example, the standard ontology examples contain too few properties.

- (2)

- In the case of parameter , all models contain concepts with empty property sets; the best value is calculated for the UML model.

- (3)

- Considering , both UML model and SHOE ontology have optimal values.

- (4)

- Regarding the parameter , all three models have very similar values, which are relatively low values.

- (5)

- For the measure , while there are no great differences, there is a relatively large distance between the declared and inferred concepts. The best value is again found for the UML model.

Based on the measured values, the usual ontology models appear to be weaker than the UML-oriented models from the viewpoint of property usage; these models should be extended in order to apply them as input for software or database development. With the help of the proposed measures, we can highlight the weakness of the usual ontology design approach for cases in which the resulting models cannot provide enough information for complex applications to support decision-making.

Summarizing the presented results, the main the goal of the proposed methodology is to highlight the importance of properties in ontology models and to measure the attribute-oriented quality of the prepared ontology. The key contributions cover the following elements:

- Our analysis shows available ontology quality tests using only a simple property-based measure (number of properties);

- We argue that a high-quality, multi-purpose, and reusable ontology model can be used in many application domains, such as software development, that require an appropriate property set;

- We introduce five novel property-based quality metrics for ontology models;

- As the performed tests show, the proposed metrics are suitable for showing the key differences of different semantic models;

- The introduced metrics can be used to measure the quality level of ontology models under development.

In addition to the presented benefits, the proposed methodology has limitations, which can be summarized as follows:

- The presented method is only a measure to show the quality of the ontology, and cannot provide direct routines to perform the corrections;

- In the case of complex ontologies, the evaluation of the model may take a longer time.

6. Conclusions

To help designers use an appropriate set of properties in ontology modeling, the present paper introduces novel quality metrics based on property usage parameters for ontology modeling. With an optimal structure, an ontology can be used as a direct tool in fields such as software and database development. This paper presents a detailed analysis of the proposed measures, along with test applications using examples of different sizes. The tested examples show the clear benefits of the proposed quality metrics in ontology modeling; these metrics can provide significant support in the development of multi-purpose ontology models.

The proposed metrics can help ontology designers to produce an ontology which can be applied in different knowledge management applications. Thanks to a more balanced class structure, the resulted ontology is suitable for both software engineering and knowledge management. Prospective application areas for future ontologies include semantic web decision support systems, biology, intelligent e-tutor systems, and engineering applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A. and L.K.; methodology, A.A. and L.K.; software, L.K.; validation, A.A. and L.K.; formal analysis, A.A. and L.K.; Writing—original draft preparation, A.A. and L.K.; Writing—review and editing, A.A. and L.K.; funding acquisition, A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Symbol | Notation |

| UML | Unified Modelling Language |

| SE | Software Engineering |

| FCA | Formal Concept Analysis |

| OWL | Web Ontology Language, ontology standard |

| XML | Extensible Markup Language, data format standard |

| XQuery | XML manipulation language |

References

- Welty, C. Ontology research. AI Mag. 2003, 24, 11–14. [Google Scholar]

- Vrandečić, D. Ontology evaluation. In Handbook on Ontologies; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 293–313. [Google Scholar]

- Niles, I.; Pease, A. Towards a standard upper ontology. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Formal Ontology in Information Systems, Ogunquit, ME, USA, 17–19 October 2001; pp. 2–9. [Google Scholar]

- Guarino, N. Formal ontology and information systems. In Proceedings of the FOIS’98 Conference, Trento, Italy, 6–8 June 1998; pp. 12–19. [Google Scholar]

- Noy, N.; McGuinness, D. Ontology Development 101: A Guide to Creating Your First Ontology; Stanford University: Stanford, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Fensel, D.A.; van Harmelen, F.A.H.; Akkermans, J.M.; Klein, M.; Broekstra, J.; Fluit, C.; van der Meer, J.; Schnurr, H.-P.; Studer, R.; Davies, J.; et al. On-to-knowledge: Ontology-based tools for knowledge management. In Proceedings of the eBusiness and eWork2000 Conference, Madrid, Spain, 18–20 October 2000; pp. 18–20. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A.; Anand, P. State of art in ontology development tools. Int. J. 2013, 2, 96–101. [Google Scholar]

- Spyns, P.; Meersman, R.; Jarrar, M. Data modelling versus ontology engineering. ACM Sigmod Rec. 2002, 31, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sir, M.; Bradac, Z.; Fiedler, P. Ontology versus Database. IFAC Pap. 2015, 48, 220–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehm, B.; In, H. Identifying Quality Requirements Conflicts. In Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Requirements Engineering, Colorado Springs, CO, USA, 15–18 April 1996; pp. 25–35. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, K.M.D.; Villela, K.; Rocha, A.R.; Travassos, G.H. Use of Ontologies in Software Development Environments. In Ontologies for Software Engineering and Technology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz, F.; Hilera, J.R. Using ontologies in software engineering and technology. In Ontologies for Software Engineering and Software Technology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; pp. 49–102. [Google Scholar]

- Bures, T.; Denney, E.; Fischer, B.; Nistor, E.C. The Role of Ontologies in Schema-Based Program Synthesis. 2004; pp. 25–35. Available online: https://ntrs.nasa.gov/citations/20040152152 (accessed on 1 October 2022).

- Goldman, N.M. Ontology-oriented programming: Static typing for the inconsistent programmer. In Proceedings of the International Semantic Web Conference, Sanibel Island, FL, USA, 20–23 October 2003; pp. 850–865. [Google Scholar]

- Wouters, B.; Deridder, D.; Van Paesschen, E.V. The use of ontologies as a backbone for use case management. In Proceedings of the European Conference on ObjectOriented Programming (ECOOP), Sophia Antipolis and Cannes, France, 12–16 June 2000; Volume 182, pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Tamma, V.A.M.; Bench-Capon, T. Supporting inheritance mechanisms in ontology representation. In Proceedings of the Knowledge Acquisition, Modeling and Management, 12th International Conference, EKAW 2000, Juan-les-Pins, France, 2–6 October 2000; pp. 140–155. [Google Scholar]

- Ghassan, B. An OO model for incremental hierarchical KA. In Proceedings of the Knowledge Engineering and Knowledge Management. Ontologies and the Semantic Web, 13th International Conference, EKAW, Siguenza, Spain, 1–4 October 2002; pp. 14–20. [Google Scholar]

- Ganter, B.; Wille, R. Formal Concept Analysis: Mathematical Foundation; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kovács, L. An Algorithm using Context Reduction for Efficient Incremental Generation of Concept Set. Fundam. Informaticae 2019, 165, 287–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obitko, M.; Snasel, V.; Smid, J. Ontology Design with Formal Concept Analysis; Technical University of Ostrava: Ostrava, Czech Republic, 2004; pp. 111–119. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, X.; Zhao, W. An Incremental and FCA-based Ontology Construction Method for Semantics-based Component Retrieval. In Proceedings of the Seventh International Conference on Quality Software (QSIC 2007), Portland, OR, USA, 11–12 October 2007; pp. 309–315. [Google Scholar]

- Jridi, J.E.; Lapalme, G. FCA-Based Concept Detection in RosettaNet PIP Ontology. 2013. Available online: https://ceur-ws.org/Vol-1058/paper3.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2022).

- Jiang, G.; Ogasawara, K.; Endoh, A.; Sakurai, T. Context-based Ontology building support in clinical domains using formal concept analysis. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2003, 71, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, S.; Cai, Z. Using the Format Concept Analysis to construct the tourism information ontology. In Proceedings of the Seventh International Conference on Fuzzy Systems and Knowledge Discovery, FSKD 2010, Yantai, China, 10–12 August 2010; pp. 2941–2944. [Google Scholar]

- Ning, L.; Guanyu, L.; Li, S. Using Formal Concept Analysis for maritime ontology building. In Proceedings of the 2010 International Forum on Information Technology and Applications, Kunming, China, 16–18 July 2010; pp. 159–162. [Google Scholar]

- Haav, H.M. A semi-automatic method to Ontology design by using FCA. In Proceedings of the CLA 2004 International Workshop on Concept Lattices and their Applications, Ostrava, Czech Republic, 23–24 September 2004; pp. 13–24. [Google Scholar]

- Priya, M.; Kumar, C.A. A survey of state of the art of Ontology construction and merging using formal concept analysis. Indian J. Sci. Technol. 2015, 8, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahayu, N.W.; Ferdiana, R.; Kusumawardani, S.S. A systematic review of ontology use in E-Learning recommender system. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2022, 3, 100047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhakal, S.; Zhang, L.; Lv, X. Ontology-based semantic modelling to support knowledge-based document classification on disaster-resilient construction practices. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2022, 22, 2059–2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djenouri, Y.; Belhadi, H.; Akli-Astouati, K.; Cano, A.; Lin, J.C.W. An ontology matching approach for semantic modeling: A case study in smart cities. Comput. Intell. 2022, 38, 876–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Chen, R.; Tong, Q.; Qin, Z.; Shi, Q.; Duan, L. An ontology-based deep belief network model. Computing 2022, 104, 1017–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murali, E.; Anouncia, S.M. An Ontology-based Knowledge Mining Model for Effective Exploitation of Agro Information. IETE J. Res. 2022, 1, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiura, N.; Shigeta, Y.; Fukuta, N.; Izumi, N.; Yamaguchi, T. Towards on-the-fly ontology construction–focusing on ontology quality improvement. In Proceedings of the European Semantic Web Symposium, Heraklion, Greece, 10–12 May 2004; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Stvilia, B. A model for ontology quality evaluation. First Monday 2007, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlomani, H.; Stacey, D. Approaches, methods, metrics, measures, and subjectivity in ontology evaluation: A survey. Semant. Web J. 2014, 1, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Burton-Jones, A.; Storey, V.C.; Sugumaran, V.; Ahluwalia, P. A semiotic metrics suite for assessing the quality of ontologies. Data Knowl. Eng. 2005, 55, 84–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tartir, S.; Arpinar, I.B.; Moore, M.; Sheth, A.P.; Aleman-Meza, B. OntoQA: Metric-based ontology quality analysis. In Proceedings of the IEEE ICDM 2005 Workshop on Knowledge Acquisition from Distributed, Autonomous, Semantically Heterogeneous Data and Knowledge Sources, Houston, TX, USA, 17 November 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, M.T.; Toussaint, Y. Introducing Metrics in the Lattice to Build Ontology. 2014. Available online: http://www.semantic-web-journal.net/content/introducing-metrics-lattice-build-ontology (accessed on 1 October 2022).

- Arpinar, I.B.; Giriloganathan, K.; Aleman-Meza, B. Ontology Quality by Detection of Conflicts in Metadata. 2006. Available online: https://ceur-ws.org/Vol-179/eon2006arpinaretal.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2022).

- Tartir, S.; Arpinar, I.B.; Sheth, A.P. Ontological evaluation and validation. In Theory and Applications of Ontology: Computer Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 115–130. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://www.cs.umd.edu/projects/plus/SHOE/onts/univ1.0.html (accessed on 1 October 2022).

- Tong, Q.; Zhang, F.; Cheng, J. Construction of RDF(S) from UML Class Diagrams. J. Comput. Inf. Technol. 2014, 22, 237–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pizza Ontology. 2016. Available online: https://github.com/owlcs/pizza-ontology/blob/master/pizza.owl (accessed on 1 October 2022).

- Błaszczyński, J.; Słowiński, R.; Susmaga, R. Rule-based estimation of attribute relevance. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Rough Sets and Knowledge Technology, Banff, AB, Canada, 9–12 October 2011; pp. 36–44. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).