Impact of the Power-Dependent Beam Diameter during Electron Beam Additive Manufacturing: A Case Study with γ-TiAl

Abstract

1. Introduction

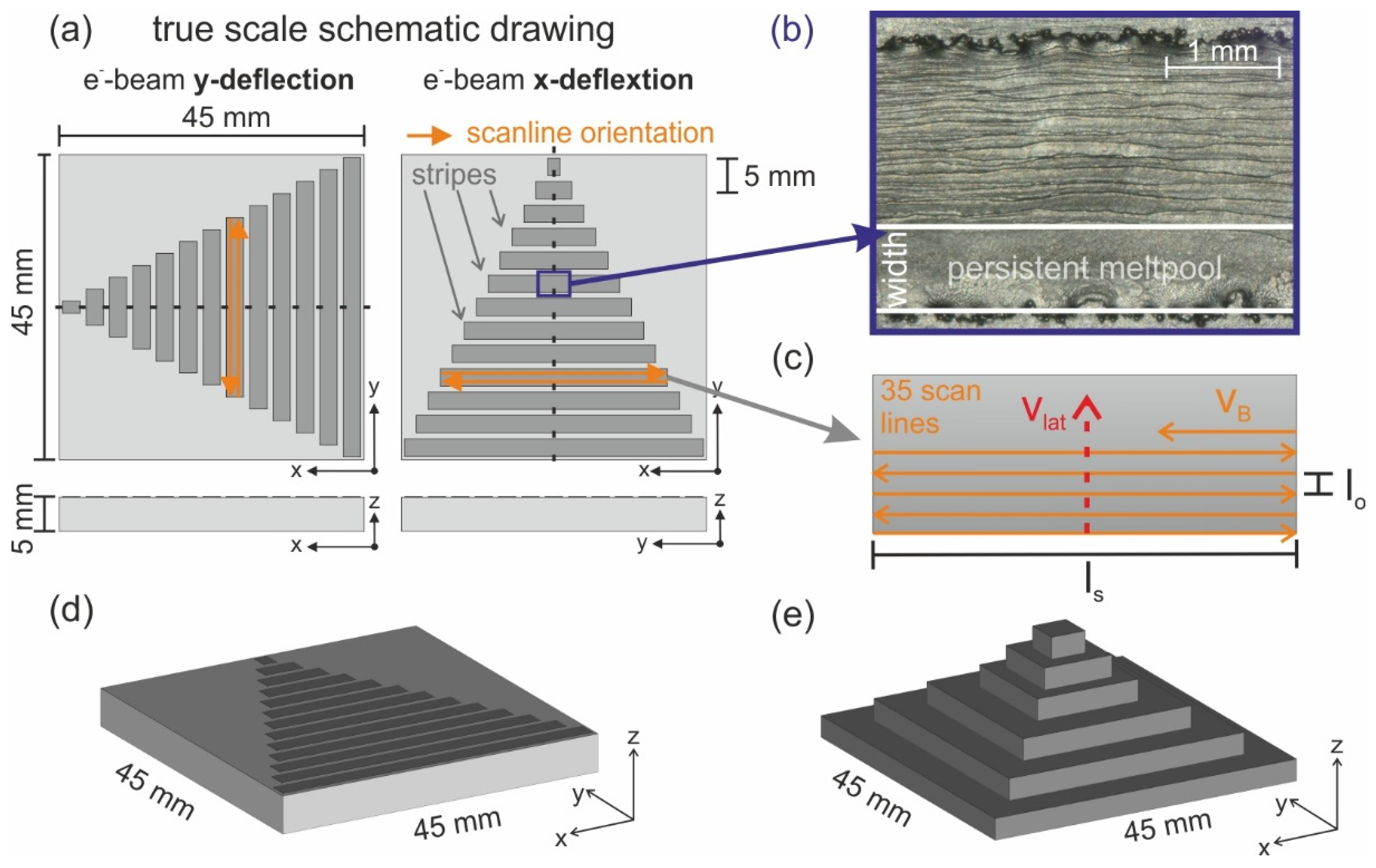

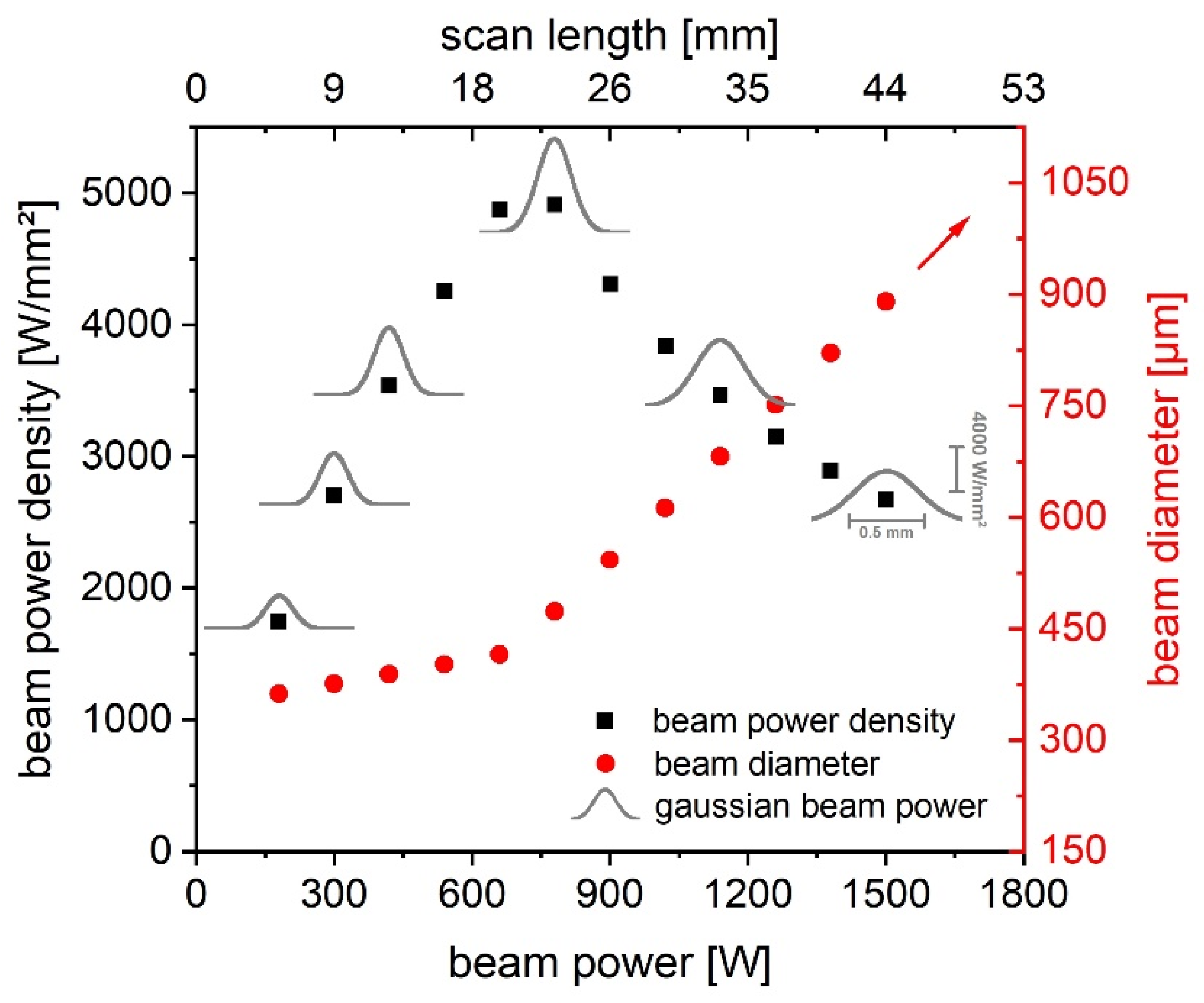

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

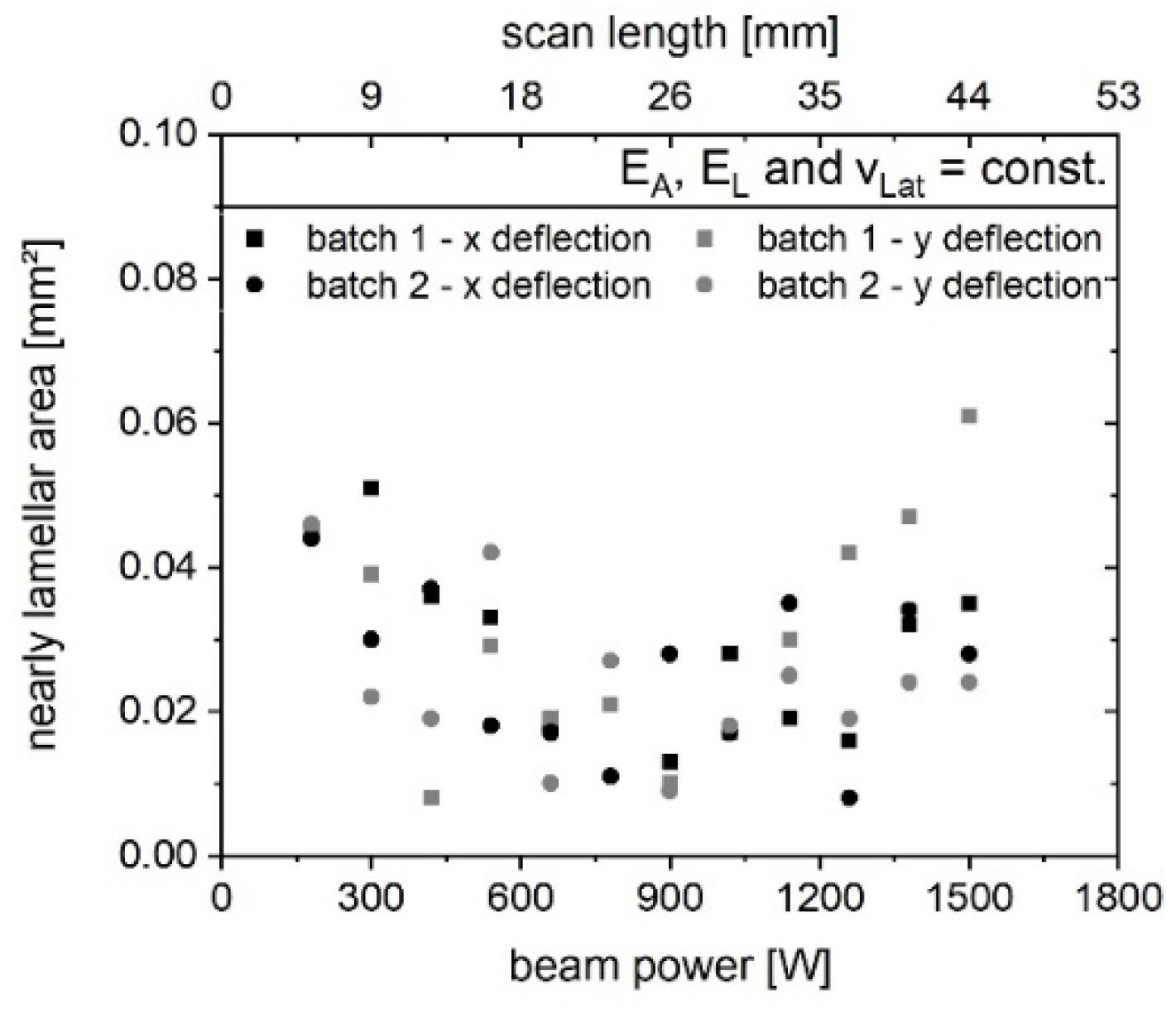

3.1. Characterization of the Melt Pool

3.2. Microstructure and Defects

3.2.1. Starting Area

3.2.2. Porosity and Aluminum Content

4. Discussion

4.1. Correlation between Melt Pool and Microstructure

4.2. Beam Diameter and Energy Input

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fu, Z.; Körner, C. Actual state-of-the-art of electron beam powder bed fusion. Eur. J. Mater. 2022, 2, 54–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowski, J.J.; Seifi, M. Metal Additive Manufacturing: A Review of Mechanical Properties. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 2016, 46, 151–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galati, M.; Iuliano, L. A literature review of powder-based electron beam melting focusing on numerical simulations. Addit. Manuf. 2018, 19, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breuning, C.; Arnold, C.; Markl, M.; Körner, C. A multivariate meltpool stability criterion for fabrication of complex geometries in electron beam powder bed fusion. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 45, 102051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, H.; Rafi, K.; Gu, H.; Starr, T.; Stucker, B. Analysis of defect generation in Ti–6Al–4V parts made using powder bed fusion additive manufacturing processes. Addit. Manuf. 2014, 1–4, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pobel, C.R.; Arnold, C.; Osmanlic, F.; Fu, Z.; Körner, C. Immediate development of processing windows for selective electron beam melting using layerwise monitoring via backscattered electron detection. Mater. Lett. 2019, 249, 70–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchner, A.; Klöden, B.; Luft, J.; Weißgärber, T.; Kieback, B. Process window for electron beam melting of Ti-6Al-4V. Powder Metall. 2015, 58, 246–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirka, M.M.; Lee, Y.; Greeley, D.A.; Okello, A.; Goin, M.J.; Pearce, M.T.; Dehoff, R.R. Strategy for Texture Management in Metals Additive Manufacturing. JOM 2017, 69, 523–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmer, H.; Bauereiß, A.; Singer, R.F.; Körner, C. Grain structure evolution in Inconel 718 during selective electron beam melting. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2016, 668, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotterbarm, M.R.; Rausch, A.M.; Körner, C. Fabrication of Single Crystals through a µ-Helix Grain Selection Process during Electron Beam Metal Additive Manufacturing. Metals 2020, 10, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pistor, J.; Breuning, C.; Körner, C. A Single Crystal Process Window for Electron Beam Powder Bed Fusion Additive Manufacturing of a CMSX-4 Type Ni-Based Superalloy. Materials 2021, 14, 3785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klassen, A.; Forster, V.E.; Juechter, V.; Körner, C. Numerical simulation of multi-component evaporation during selective electron beam melting of TiAl. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2017, 247, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wartbichler, R.; Clemens, H.; Mayer, S.; Ghibaudo, C.; Rizza, G.; Galati, M.; Iuliano, L.; Biamino, S.; Ugues, D. On the Formation Mechanism of Banded Microstructures in Electron Beam Melted Ti–48Al–2Cr–2Nb and the Design of Heat Treatments as Remedial Action. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2021, 23, 2101199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reith, M.; Franke, M.; Schloffer, M.; Körner, C. Processing 4th generation titanium aluminides via electron beam based additive manufacturing—Characterization of microstructure and mechanical properties. Materialia 2020, 14, 100902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everhart, W.; Dinardo, J.; Barr, C. The Effect of Scan Length on the Structure and Mechanical Properties of Electron Beam-Melted Ti-6Al-4V. Metall. Mat. Trans. A 2017, 48, 697–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederick, C.L.; Plotkowski, A.; Kirka, M.M.; Haines, M.; Staub, A.; Schwalbach, E.J.; Cullen, D.; Babu, S.S. Geometry-Induced Spatial Variation of Microstructure Evolution During Selective Electron Beam Melting of Rene-N5. Metall. Mat. Trans. A 2018, 49, 5080–5096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knörlein, J.; Franke, M.M.; Schloffer, M.; Körner, C. In-situ aluminum control for titanium aluminide via electron beam powder bed fusion to realize a dual microstructure. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 59, 103132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klassen, A.; Bauereiß, A.; Körner, C. Modelling of electron beam absorption in complex geometries. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2014, 47, 65307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galati, M.; Iuliano, L.; Salmi, A.; Atzeni, E. Modelling energy source and powder properties for the development of a thermal FE model of the EBM additive manufacturing process. Addit. Manuf. 2017, 14, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| γ-TiAl BMBF3 1 | Ti | Al | Nb | W | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| at.% | at.% | at.% | at.% | ||

| batch 1 | nom. | bal. | 47.5 | 5.5 | 0.5 |

| batch 1 | measured | bal. | 47.5 | 5.6 | 0.4 |

| batch 2 | nom. | bal. | 47.5 | 5.7 | 0.5 |

| batch 2 | measured | bal. | 46.8 | 5.7 | 0.5 |

| Scan Length | Beam Current | Beam Power | Beam Velocity |

|---|---|---|---|

| mm | mA | W | mm/s |

| 1.8 | 1.0 | 60 | 479 |

| 5.3 | 3.0 | 180 | 1412 |

| 8.8 | 5.0 | 300 | 2344 |

| 12.3 | 7.0 | 420 | 3276 |

| 15.9 | 9.0 | 540 | 4235 |

| 19.4 | 11.0 | 660 | 5167 |

| 22.9 | 13.0 | 780 | 6099 |

| 26.5 | 15.0 | 900 | 7058 |

| 30.0 | 17.0 | 1020 | 7990 |

| 33.5 | 19.0 | 1140 | 8922 |

| 37.1 | 21.0 | 1260 | 9881 |

| 40.6 | 23.0 | 1380 | 10,813 |

| 44.1 | 25.0 | 1500 | 11,745 |

| Property | Value |

|---|---|

| Thermal diffusivity 2 [m2/s] | 6 × 10−6 |

| Density 2 [kg/m3] | 3533 |

| Specific heat 2 [J/(kg·K)] | 1160 |

| Absorption coefficient | 0.85 |

| Preheat temperature [K] | 1023 |

| Liquidus temperature 2 [K] | 1832 |

| Beam diameter (4σ) [µm] | 340 µm or Equation (5) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Reith, M.; Breuning, C.; Franke, M.; Körner, C. Impact of the Power-Dependent Beam Diameter during Electron Beam Additive Manufacturing: A Case Study with γ-TiAl. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 11300. https://doi.org/10.3390/app122111300

Reith M, Breuning C, Franke M, Körner C. Impact of the Power-Dependent Beam Diameter during Electron Beam Additive Manufacturing: A Case Study with γ-TiAl. Applied Sciences. 2022; 12(21):11300. https://doi.org/10.3390/app122111300

Chicago/Turabian StyleReith, Marcel, Christoph Breuning, Martin Franke, and Carolin Körner. 2022. "Impact of the Power-Dependent Beam Diameter during Electron Beam Additive Manufacturing: A Case Study with γ-TiAl" Applied Sciences 12, no. 21: 11300. https://doi.org/10.3390/app122111300

APA StyleReith, M., Breuning, C., Franke, M., & Körner, C. (2022). Impact of the Power-Dependent Beam Diameter during Electron Beam Additive Manufacturing: A Case Study with γ-TiAl. Applied Sciences, 12(21), 11300. https://doi.org/10.3390/app122111300