Institutional Adoption and Implementation of Blended Learning in the Era of Intelligent Education

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- How are the courses transformed and applied during the institutional educational reform period?

- What are the effects of the transformed BL courses in improving learning performance?

- To what extent have the involved instructors gained professional development?

2. Literature Review

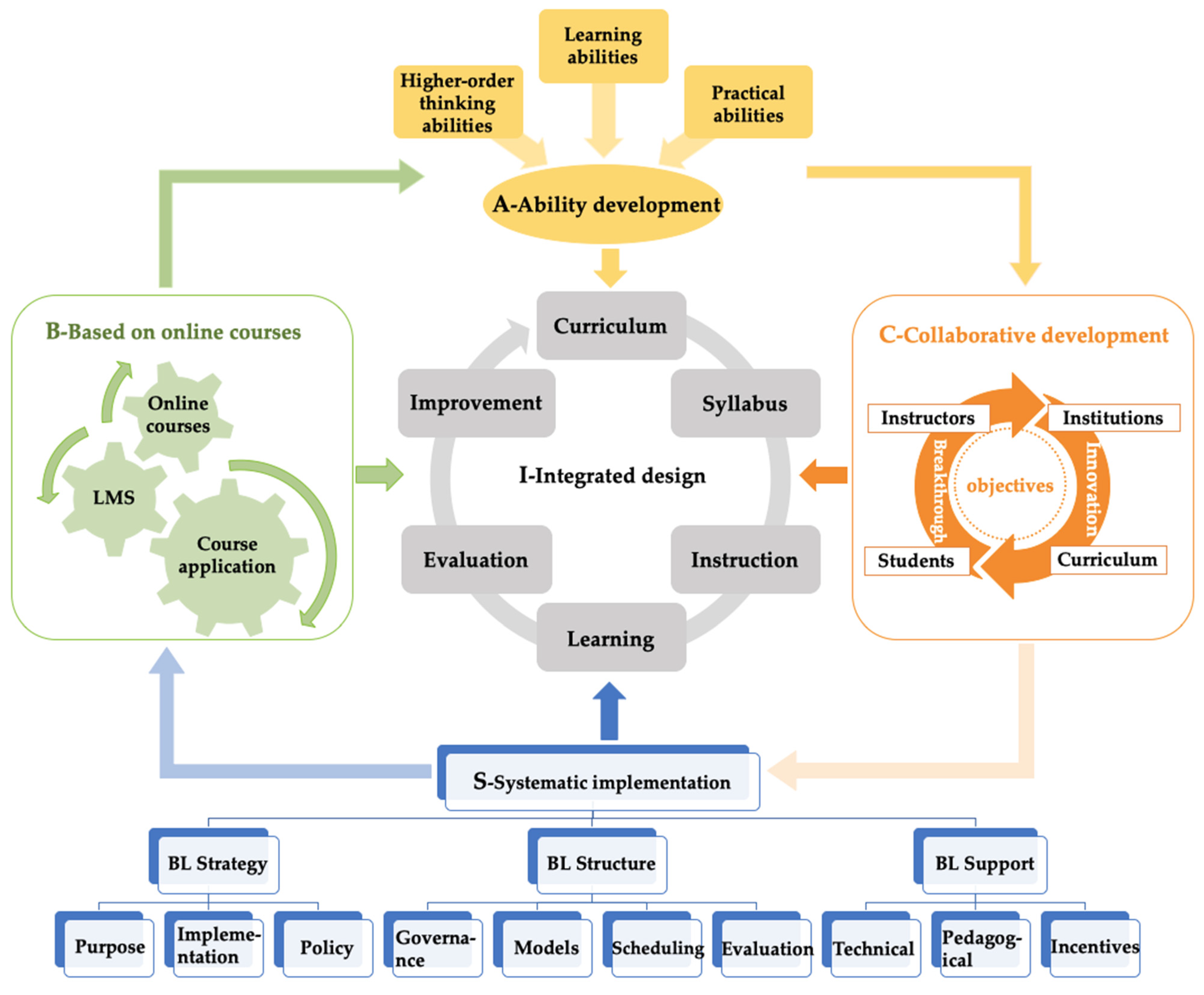

2.1. Blended Learning Strategy

2.2. Blended Learning Structure

2.3. Blended Learning Support

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Sample Description

3.3. Instruments

3.4. Data Collection and Analysis

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Fulfillment of the Intervention Objective

4.1.1. Achievement on Blended Learning Strategy

4.1.2. Achievement on Blended Learning Structure

4.1.3. Achievement on Blended Learning Support

4.2. Transformation of Institutional Courses

4.2.1. Course Transformation

4.2.2. Course Application

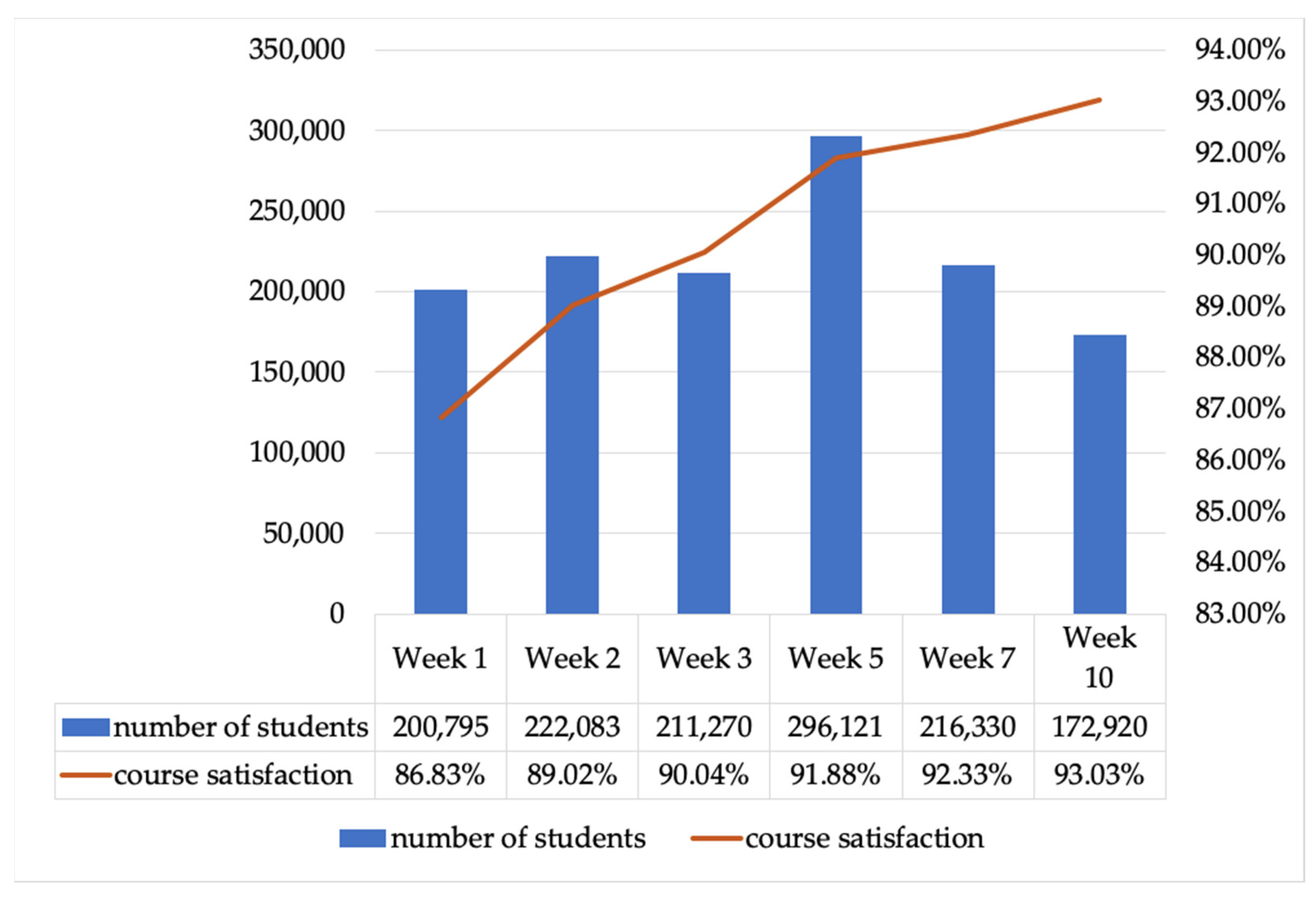

4.3. Improvement of Students’ Learning Performance

4.3.1. Effect in Improving Learning Performance

4.3.2. Students’ Satisfaction Rate of the BL Courses during School Closure Period

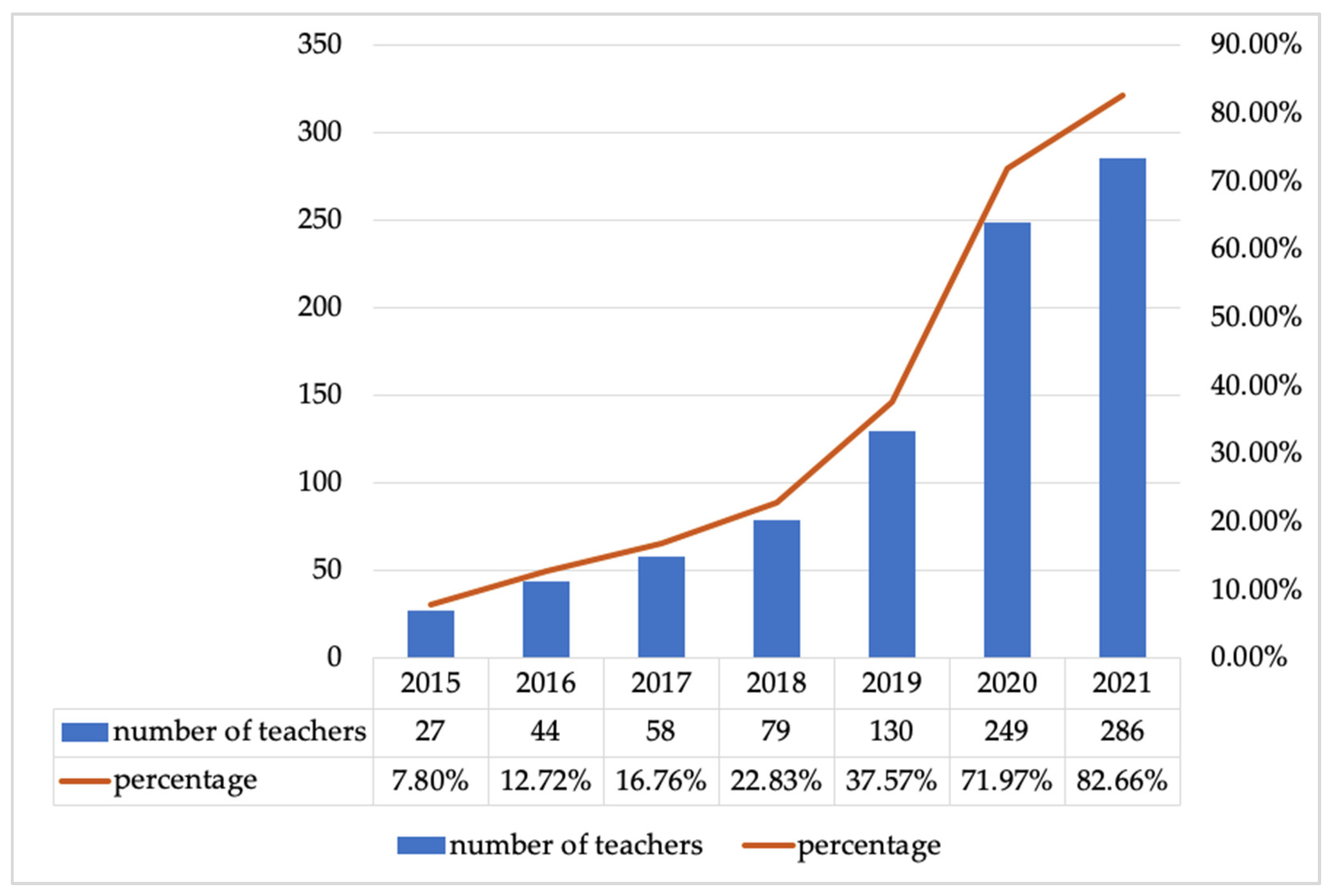

4.4. Development of Instructors’ Professional Skills

4.4.1. Instructors’ BL Projects and Publications

4.4.2. Instructors’ Perception on Professional Development

5. Conclusions and Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- The learning resources provided by the instructor are rich and novel, which can reflect the latest frontiers of the subject. 1 2 3 4 5

- This course has helped me improve my comprehensive ability to solve complex problems. 1 2 3 4 5

- This course is very useful for my study, develops my thinking ability and improves my sense of identity with my major. 1 2 3 4 5

- There are many interactive teaching activities between instructors and students, such as discussion, group work, etc. 1 2 3 4 5

- This course has helped me improve my thinking ability, such as in-depth analysis and questioning. 1 2 3 4 5

- The course set high standards and I had to work hard to meet them. 1 2 3 4 5

- The course assessment covers academic papers/research reports, tests and other kinds of assessments, which require great efforts to complete. 1 2 3 4 5

Appendix B

- Department

- Gender

- Education Degree: bachelor’s master’s doctoral

- Teaching Age: <5 years 6–10 years 11–20 years >21 years

- Professional Title:Teaching assistant Assistant Professor Associate Professor Professor

- Start BL course in: 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 not yet

- Number of classes involved in my BL courses in the previous schooling year0 1 2 3 4 5 >5

- Number of BL related papers published as 1st author0 1 2 3 4 5 >5

| No. | Blended Learning Reform Activities | (A) Participation | (B) Impact on Professional Development | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Very Small | Small | Medium | Big | Very Big | ||

| 9 | the institutional BL policy | |||||||

| 10 | feedback from school inspection and/or peers | |||||||

| 11 | feedback from students | |||||||

| 12 | LMS for BL course implementation | |||||||

| 13 | the institutional BL community of practice (the Wechat Group) | |||||||

| 14 | the BL lectures, workshops, and salons | |||||||

| 15 | BL course transformation with institutional funding | |||||||

| 16 | BL course transformation without institutional funding | |||||||

| 17 | provincial BL reform projects and/or provincial award on teaching competitions | |||||||

Appendix C

- Curriculum introduction should cover curriculum objectives, teaching and learning hours, credits, focal and difficult points, teaching approaches, assessment methods, teaching staff, etc.

- Self-regulated learning guidance should contain learning content, resources, and assessment methods. It is suggested that 20–50% of the course hours be allocated for self-regulated learning conducted out of class.

- Blended Learning Design should ensure a cohesive link between in- and out-of-class learning, and a cohesive link between online and face-to-face learning. It is recommended that instructors use case-based instruction, heuristic instruction, flipped classroom, etc. to implement the BL design.

- Online interaction and discussion should be mainly conducted on LMS forums; meanwhile, instructors are supposed to involve themselves in such interaction.

- Course assessment should cover both formative and summative assessments. Formative assessment should ensure its quantity and variety. A minimum of one formative assessment (e.g., group work, in-class presentation, etc.) that examines the fulfillment of MOE’s first-class curriculum evaluation standard (IHC) is required. Meanwhile, the weight of the summative assessment should not outweigh that of the formative assessment.

References

- Al-Samarraie, H.; Saeed, N. A systematic review of cloud computing tools for collaborative learning: Opportunities and challenges to the blended-learning environment. Comput. Educ. 2018, 124, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boelens, R.; De Wever, B.; Voet, M. Four key challenges to the design of blended learning: A systematic literature review. Educ. Res. Rev. 2017, 22, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, C.R. Blended learning systems: Definition, current trends, and future directions. In The Handbook of Blended Learning Environments: Global Perspectives, Local Designs; Bonk, C.J., Graham, C.R., Eds.; Jossey-Bass/Pfeiffer: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2006; pp. 2–12. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, C.R.; Robison, R. Realizing the transformational potential of blended learning: Comparing cases of transforming blends and enhancing blends in higher education. In Blended Learning: Research Perspectives; Picciano, A.G., Dziuban, C.D., Eds.; The Sloan Consortium: Needham, MA, USA, 2007; pp. 83–110. [Google Scholar]

- The Ministry of Education’s Policy on Strengthening the Development and Application of the Open Online Courses in Universities. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/gongbao/content/2015/content_2883243.htm (accessed on 10 December 2015).

- Rasheed, R.A.; Kamsin, A.; Abdullah, N.A. Challenges in the online component of blended learning: A systematic review. Comput. Educ. 2020, 144, 103701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, C.R.; Woodfield, W.; Harrison, J.B. A framework for institutional adoption and implementation of blended learning in higher education. Internet High. Educ. 2013, 18, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picciano, A.G. Blending with Purpose: The Multimodal Model. J. Res. Cent. Educ. Technol. 2009, 5, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, C.R.; Allen, S.; Ure, D. Benefits and challenges of blended learning environments. In Encyclopedia of Information Science and Technology; Khosrow-Pour, M., Ed.; Idea Group: Hershey, PA, USA, 2005; pp. 253–259. [Google Scholar]

- Garrison, D.R.; Kanuka, H. Blended learning: Uncovering its transformative potential in higher education. Internet High. Educ. 2004, 7, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, N. Perspectives on blended learning in higher education. Int. J. E-Learn. 2007, 6, 81–94. [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly, R. Harmonizing technology with interaction in blended learning problem-based learning. Comput. Educ. 2010, 42, 350–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moskal, P.; Dziuban, C.; Hartman, J. Blended learning: A dangerous idea? Internet High. Educ. 2013, 18, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owston, R. Blended learning policy and implementation: Introduction to the special issue. Internet High. Educ. 2013, 18, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemiec, M.; Otte, G. An administrator’s guide to the whys and hows of blended learning. J. Asynchronous Learn. Netw. 2010, 14, 91–102. [Google Scholar]

- Heilporn, G.; Lakhal, S. Fostering student engagement in blended courses: A qualitative study at the graduate level in a business faculty. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2021, 19, 100569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, T. Hitting the nail on the head: The importance of specific staff development for effective blended learning. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2012, 49, 389–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, T.K.F. Digital support for student engagement in blended learning based on self-determination theory. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 124, 106909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kırkgöz, Y. A case study of teachers’ implementation of curriculum innovation in English language teaching in Turkish primary education. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2008, 24, 1859–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhonen, H.; Pakarinen, E.; Lerkkanen, M. Do teachers’ professional vision and teaching experience always go hand in hand? Examining knowledge-based reasoning of Finnish Grade 1 teachers. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2021, 106, 103458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korr, J.; Derwin, E.B.; Greene, K.; Sokoloff, W. Transitioning an adult-serving university to a blended learning model. J. Contin. High. Educ. 2012, 60, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, M.H. Factors Influencing Faculty Adoption of Web-Based Courses in Instructor Education Programs within the State University of New York. Ph.D. Dissertation, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksburg, VA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- The Ministry of Education’s Requirement on Developing China’s First-Class Courses—Spare No Effort to Develop Five Categories of First-Class Courses Based on the “IHC” Standard. Available online: https://www.sohu.com/a/277556023_323819 (accessed on 11 November 2018).

- OECD. OECD Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS): Instructor Questionnaire; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2008; pp. 2–23.

- Han, X.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, L. Towards a framework for an institution-wide quantitative assessment of teachers’ online participation in blended learning implementation. Internet High. Educ. 2019, 42, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, C.; Mildenberger, T. Facilitating flexible learning by replacing classroom time with an online learning environment: A systematic review of blended learning in higher education. Educ. Res. Rev. 2021, 34, 100394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, W.W.; Graham, C.R.; Spring, K.A.; Welch, K.R. Blended learning in higher education: Institutional adoption and implementation. Comput. Educ. 2014, 75, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Jian, L.; Hu, K. Formative Assessment as an Online Instruction Intervention: Student Engagement, Outcomes, and Perceptions. Int. J. Distance Educ. Technol. 2021, 19, 50–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferriman, N. The impact of blended e-learning on undergraduate academic essay writing in English (L2). Comput. Educ. 2013, 60, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, K.M.Y.; Geng, S.; Li, T. Student enrollment, motivation and learning performance in a blended learning environment: The mediating effects of social, teaching, and cognitive presence. Comput. Educ. 2019, 136, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melton, B.; Graf, H.; Chopak-Foss, J. Achievement and satisfaction in blended learning versus traditional general health course designs. Int. J. Sch. Teach. Learn. 2009, 3, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Q.; Rienties, B.; Toetenel, L.; Ferguson, R.; Whitelock, D. Examining the designs of computer-based assessment and its impact on student engagement, satisfaction, and pass rates. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 76, 703–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owston, R.; York, D.; Murtha, S. Student perceptions and achievement in a university blended learning strategic initiative. Internet High. Educ. 2013, 18, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, W.W.; Graham, C.R. Institutional drivers and barriers to faculty adoption of blended learning in higher education. Brit J. Educ. Tech. 2016, 47, 748–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.K.; Kim, S.M.; Khera, O.; Getman, J. The experience of three flipped classrooms in an urban university: An exploration of design principles. Internet High. Educ. 2014, 22, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manski, C.F. Identification of endogenous social effects: The reflection problem. Rev. Econ. Stud. 1993, 60, 531–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Category | Stage 1: Exploration (2015–2016) | Stage 2: Early Implementation (2017–2018) | Stage 3: Mature Implementation (2019–2021) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strategy | |||

| Purpose | Less F2F 1 time | Ss’ abilities Ts’ development | Ss’ abilities Ts’ p development |

| Implementation | <5% of courses involved | 18% of courses involved | 59% of courses involved 20–50% online |

| Policy | Institutional policy (V1 2) | Institutional policy (V2) | Institutional BL policy (V3) |

| Structure | |||

| Governance | LMS 3 school inspection | LMS school inspection | LMS school inspection Video surveillance Ss survey |

| Models | Standard 151 (V1) | Standard 151 (V2) | Standard 151 (V3) |

| Scheduling | OL 4 curriculum schedule | OL curriculum schedule BL curriculum schedule | BL curriculum schedule |

| Evaluation | Small-scale Ss survey | Large-scale Ss survey Formative evaluation | Large-scale Ss survey Formative evaluation Summative evaluation |

| Support | |||

| Technical | LMS | LMS BL Community of Practice | LMS BL Community of Practice |

| Pedagogical | 6 BL lectures 5 BL workshops 22 BL salons | 8 BL lectures 6 BL workshops 25 BL salons Fund/arrange BL trainings | One-to-one expert guidance 4 BL lectures Fund BL trainings |

| Incentives | Fund 53 BL courses Fund provincial projects Teaching hrs counted as double | Fund 13 BL courses Fund provincial projects Teaching hrs counted as double | Fund provincial projects Teaching hrs counted as double Teaching hrs of credited BL courses counted as double |

| LMS | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moodle | 31 | 19 | 72 | 39 | 41 | 511 | 400 |

| iCourse | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 8 | 19 |

| Zhihuishu | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 12 | 15 | 22 |

| Xuetang | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 9 |

| Xueyin | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 8 |

| Total | 31 | 19 | 72 | 42 | 62 | 543 | 458 |

| LMS | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moodle | 20,415 | 8596 | 43,712 | 6141 | 20,003 | 117,211 | 79,555 |

| iCourse | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 37,351 | 62,966 | 117,020 |

| Zhihuishu | 0 | 0 | 0 | 110 | 46,551 | 63,684 | 59,598 |

| Xuetang | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8727 | 7300 | 23,898 | 3524 |

| Xueyin | 0 | 0 | 0 | 277 | 3396 | 5800 | 6635 |

| Total | 20,415 | 8596 | 43,712 | 15,255 | 114,601 | 273,559 | 266,332 |

| 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Online 1 | 1168 | 2996 | 5756 | 6170 | 8783 | 23,361 | 22,913 | 71,147 |

| Total 2 | 115,034 | 115,604 | 115,967 | 122,733 | 136,844 | 149,577 | 148,159 | 903,918 |

| OL/Total | 1.02% | 2.59% | 4.96% | 5.03% | 6.42% | 15.62% | 15.47% | 7.87% |

| Categories | Fall Semester of 2019 | Fall Semester of 2020 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BL (M) | Non-BL (M) | Sig. | BL (M) | Non-BL (M) | Sig. | |

| Innovation | 4.618 | 4.611 | 0.828 | 4.682 | 4.612 | 0.002 * |

| Higher-order | 4.6095 | 4.597 | 0.694 | 4.6495 | 4.617 | 0.223 * |

| Challenge | 4.577 | 4.543 | 0.321 * | 4.697 | 4.6425 | 0.045 * |

| Total | 4.6025 | 4.5855 | 0.593 | 4.6725 | 4.623 | 0.032 * |

| Year | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level | ||||||||

| School | 31 | 25 | 18 | 9 | 18 | 26 | 23 | |

| Provincial | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 7 | 14 | |

| Publication | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| National | 1 | 1 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 10 | 13 | 53 |

| International | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Category | Indicator | Involvement | Perception on Gains (M) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Ts | Percentage | |||

| Strategy | The institutional BL policy | 285 | 82.37% | 3.44 |

| Structure | Feedback from school inspection and/or peers | 249 | 71.97% | 3.40 |

| Feedback from students | 288 | 83.24% | 3.55 | |

| Support | LMS for BL course implementation | 264 | 76.30% | 3.55 |

| The institutional BL community of practice (the Wechat Group) | 197 | 56.94% | 3.32 | |

| The BL lectures, workshops, and salons | 237 | 68.50% | 3.60 | |

| BL course transformation with institutional funding | 66 | 19.08% | 3.64 | |

| BL course transformation without institutional funding | 224 | 64.74% | 3.21 | |

| Provincial BL reform projects and/or provincial award in teaching competitions | 92 | 26.59% | 3.64 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, C.; Wen, M.; Tong, K.; Chen, Z.; Wen, Q.; Yang, T.; Liu, Q. Institutional Adoption and Implementation of Blended Learning in the Era of Intelligent Education. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 8846. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12178846

Zhang C, Wen M, Tong K, Chen Z, Wen Q, Yang T, Liu Q. Institutional Adoption and Implementation of Blended Learning in the Era of Intelligent Education. Applied Sciences. 2022; 12(17):8846. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12178846

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Chunhui, Mingang Wen, Kuang Tong, Zexuan Chen, Qing Wen, Tingting Yang, and Qijun Liu. 2022. "Institutional Adoption and Implementation of Blended Learning in the Era of Intelligent Education" Applied Sciences 12, no. 17: 8846. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12178846

APA StyleZhang, C., Wen, M., Tong, K., Chen, Z., Wen, Q., Yang, T., & Liu, Q. (2022). Institutional Adoption and Implementation of Blended Learning in the Era of Intelligent Education. Applied Sciences, 12(17), 8846. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12178846