Introducing Personal Teaching Environment for Nontraditional Teaching Methods

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- What is the structure of a PTE and how does it work?

- (2)

- What are nontraditional teaching methods’ advantages, frameworks, and successful implementation stories?

- (3)

- How would you categorize the tool types of nontraditional teaching methods to serve PTE applications?

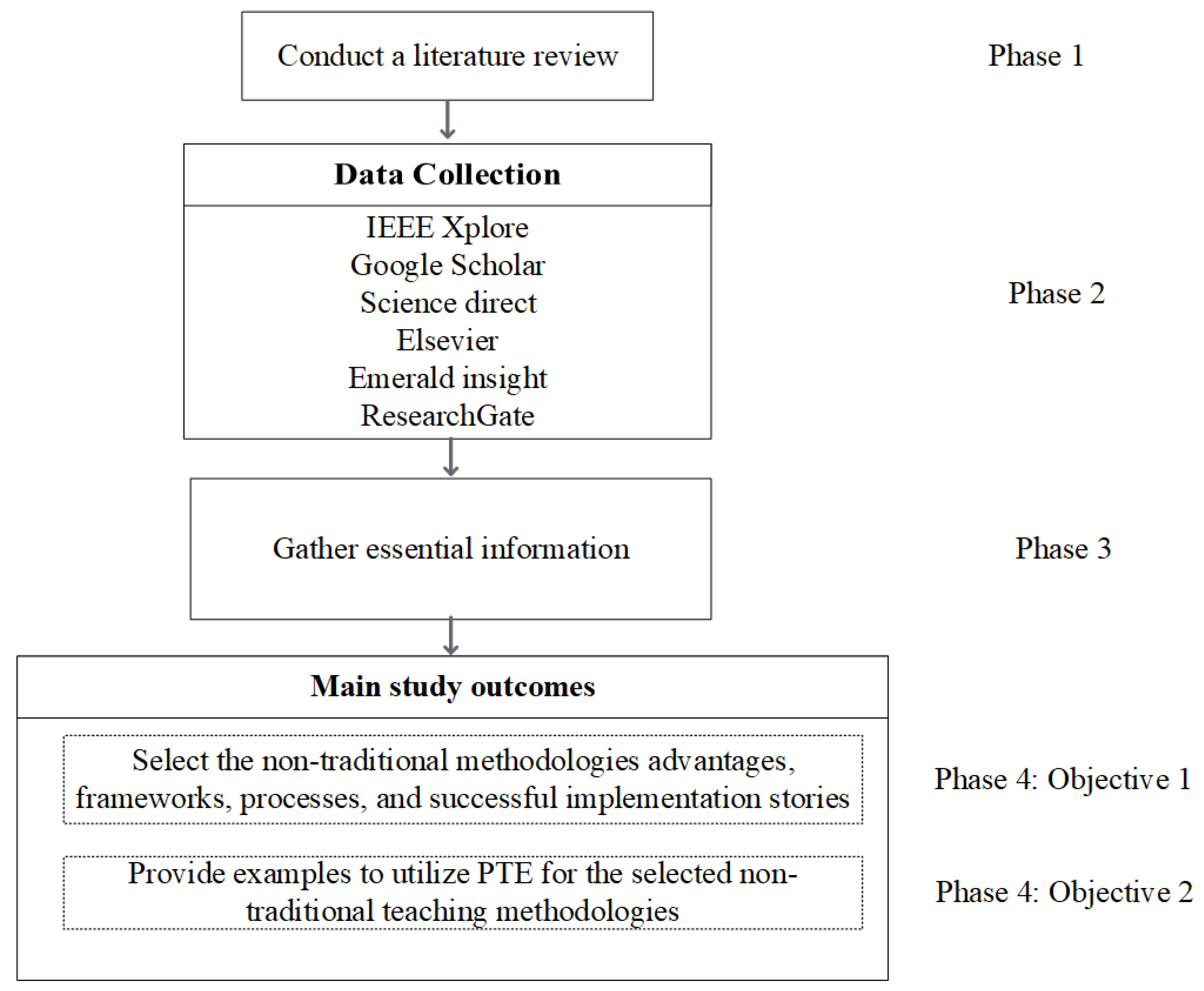

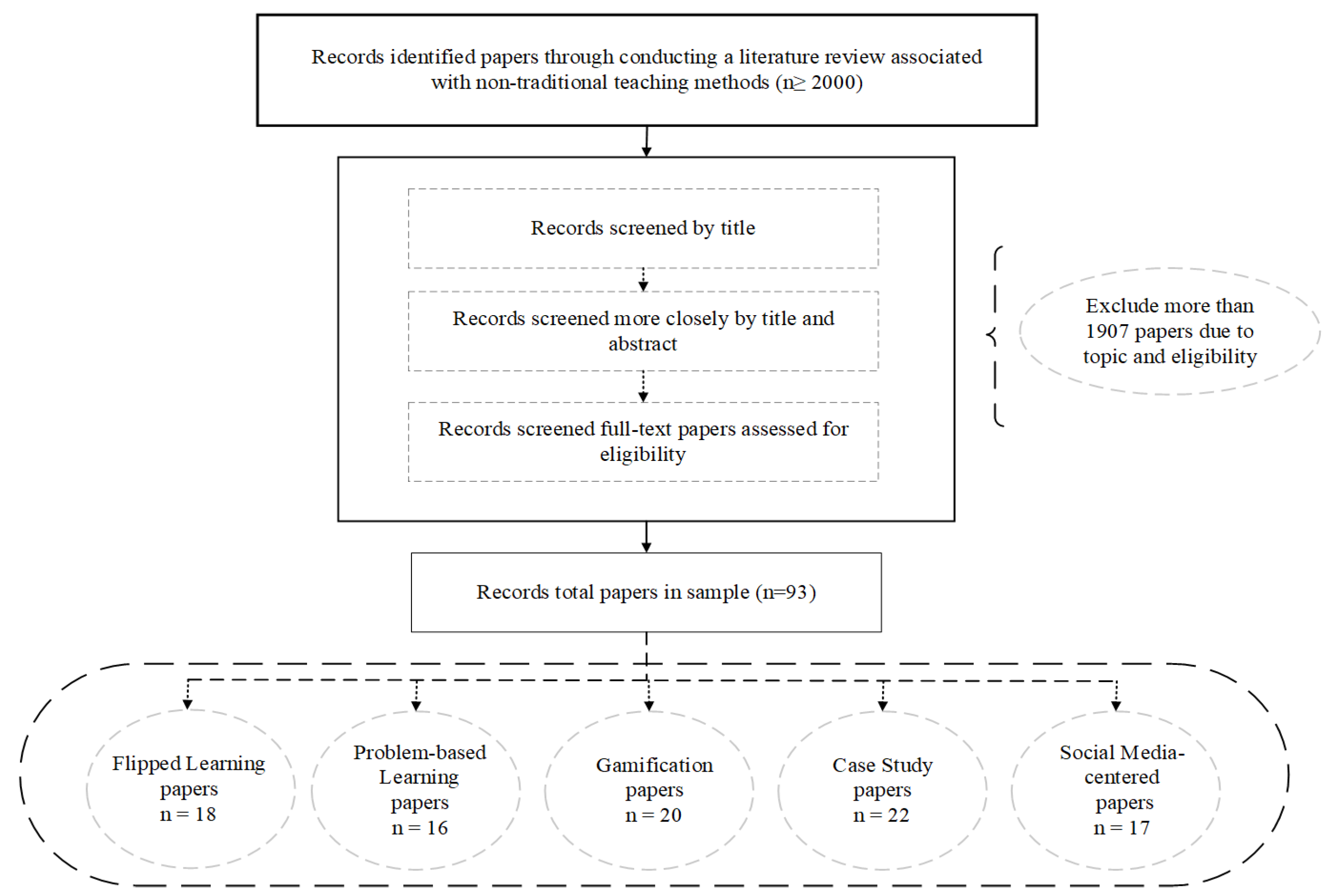

2. Methodology

- Scholarly references were highlighted and supplemented by academic publications from 2000 to 2020.

- Journal and conference papers were selected only if they contained at least one of the search terms in the title, abstract, or keywords to ensure data collection relevance.

- The only publications selected were ones that had nontraditional teaching method or personal teaching as a major or influential aspect of the research.

- Highly technical articles focused on technical aspects of PTE.

- The paper must be published in English language.

- The paper must have been published by one of the distinguished publishers such as IEEE.

- (1)

- There is not much information relating PTEs to nontraditional teaching methods.

- (2)

- The five frequently studied nontraditional teaching methods identified in the collected scholarly sources were: flipped learning, problem-based learning, gamification, case study, and social media-centered.

3. Personal Teaching Environment

3.1. Tools

3.2. Connections and Activities

3.3. Data Sources

- Data used for preparing learning content. The data sources in this regard can be a YouTube repository, word documents, online presentations, or audio files.

- Data used for student assessment. The data sources examples for this can be question banks provided by a book’s publisher or the teacher’s provided institution. Moreover, they could be repositories of open educational resources that could have been previously used by other teachers in web services such as Kahoot or Socrative.

- Students’ performance analysis data, obtained through collecting their static and dynamic data. Static data include their profiles, where they live, gender, past knowledge, etc. Dynamic data include their engagement in learning activities and their performance in assessment activities (for example, how long they read or watch a video).

- Data used for professional development. Data sources include professional websites (IEEE Xplore, ResearchGate, etc.). These databases can be used for research matters.

3.4. Teaching Methods

4. Nontraditional Teaching Methods

5. Findings: Research Questions 2 and 3

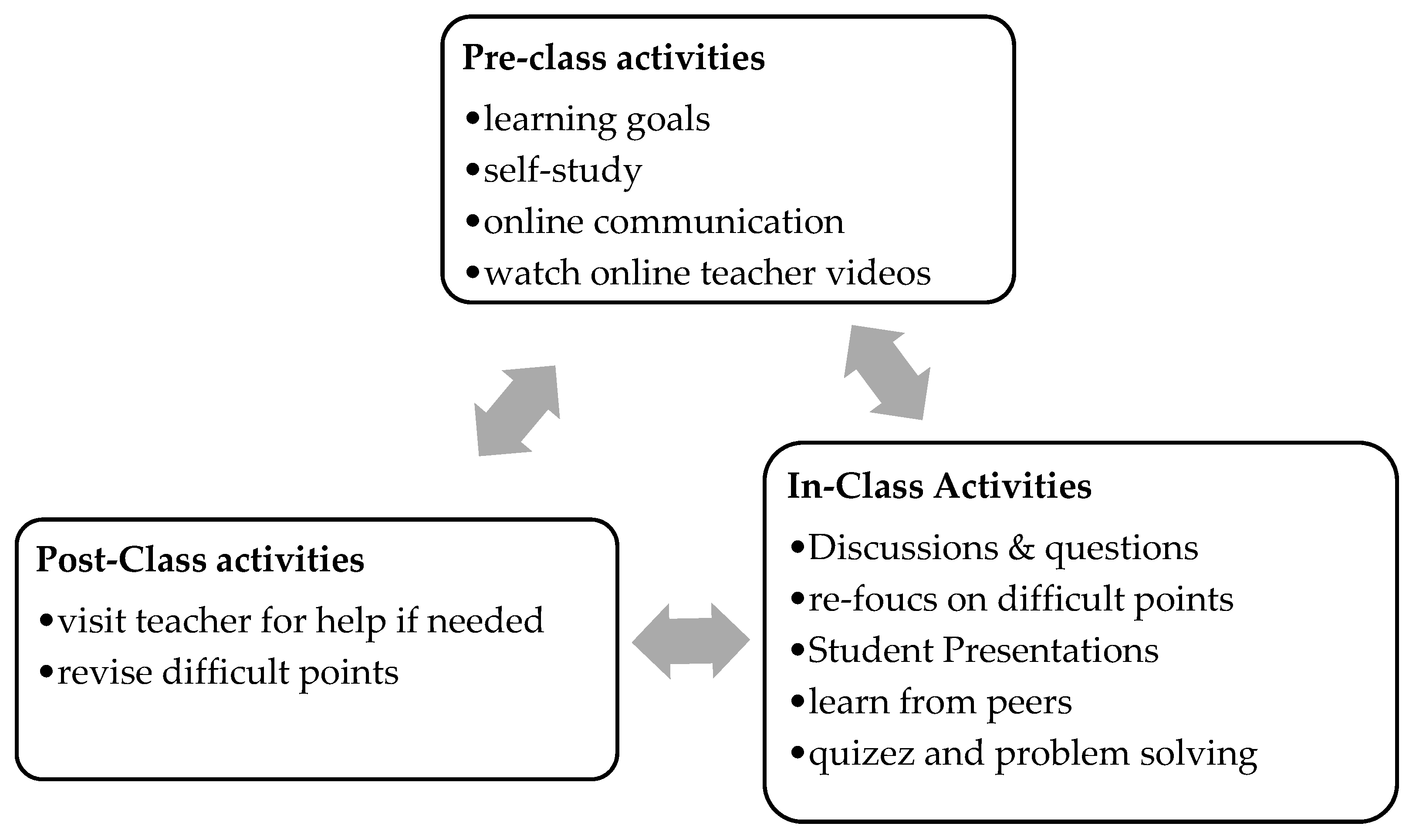

5.1. Flipped Classroom

5.2. Problem-Based Learning

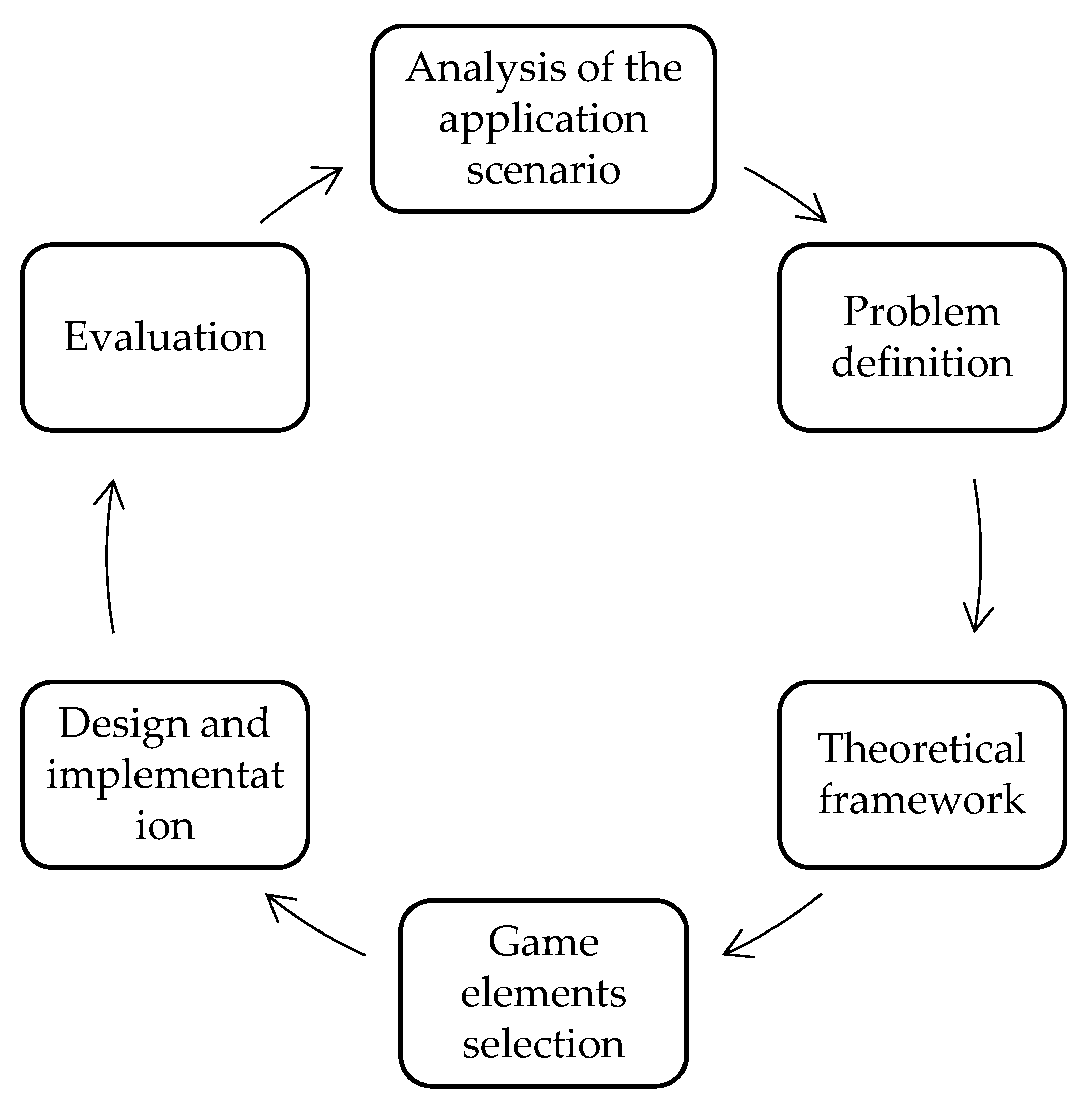

5.3. Gamification

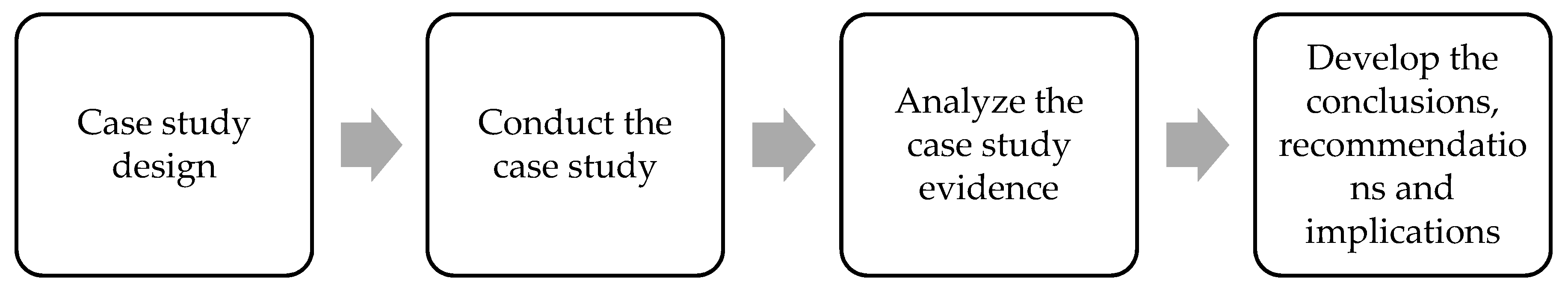

5.4. Case Study

5.5. Social Media-Centered

6. PTE Application on Nontraditional Teachings Methods

6.1. Flipped Classroom

6.2. Problem-Based Learning

6.3. Gamification

6.4. Case Study

6.5. Social Media-Centered

7. Conclusions and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mödritscher, F.; Neumann, G.; García-Barrios, V.M.; Wild, F. A Web Application Mashup Approach for eLearning—Open Research Online. 2008. Available online: http://oro.open.ac.uk/25898/ (accessed on 6 July 2022).

- Hoic-Bozic, N.; Dlab, M.H.; Mornar, V. Recommender System and Web 2.0 Tools to Enhance a Blended Learning Model. IEEE Trans. Educ. 2016, 59, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attwell, G. Personal Learning Environments—The future of eLearning ? Lifelong Learn. 2007, 2, 1–8. Available online: http://www.elearningeuropa.info/files/media/media11561.pdf (accessed on 6 July 2022).

- Anderson, P. What is Web 2.0? Ideas, technologies and implications for education Policy and advice team leader and Web focus UKOLN Web 2. JISC Technol. Stand. Watch 2007, 63, 1–64. Available online: http://www.ictliteracy.info/rf.pdf/Web2.0_research.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Castañeda, L.; Adell, J. La Anatomía de los PLEs, Entornos Pers. Aprendiz. Claves Para El Ecosistema Educ. En Red 2013, 11–27. Available online: http://digitum.um.es/xmlui/handle/10201/30408 (accessed on 15 July 2021).

- Folgado, J.; Palos, P.; Aguayo, M. Motivaciones, Formación Y Planificación Del Trabajo En Equipo Para Entornos De Aprendizaje Virtual. Interciencia 2020, 45, 102–109. [Google Scholar]

- Xusanovich, R.I. Pedagogical Methods Of Teaching Mathematics In Distance Learning. Texas J. Multidiscip. Stud. 2022, 7, 352–355. Available online: https://zienjournals.com/index.php/tjm/article/view/1465 (accessed on 9 July 2022).

- Dowling, S. Digital Learning Spaces: An Alternative to Traditional Learning Management Systems. 2011. Available online: https://platform.almanhal.com/Files/2/38710 (accessed on 9 July 2022).

- Starichenko, B.; Antipova, E.; Slepukhin, A.; Semenova, I. Design of teaching methods using virtual educational environment. SHS Web Conf. 2018, 50, 01176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- White, D.C. Design and Implementation of a Personal Knowledge Integrator Federated with Personal Knowledge Environments. 2010. Available online: https://pleconference.citilab.eu/wp-content/uploads/2010/09/ple2010_submission_7.pdf (accessed on 9 July 2022).

- Martínez, C.C.; Roma, J.C.; Briongos, C.C.; Minguillón, J.; Peña-López, I. Analyzing Learner’s Participation in a WordPress-based Personal Teaching Environment. 2014. Available online: http://openaccess.uoc.edu/webapps/o2/bitstream/10609/36941/1/Casado_PLEconf2014_AnalyzingLearnersParticipation.pdf (accessed on 9 July 2022).

- Safapour, E.; Kermanshachi, S.; Taneja, P. A Review of Nontraditional Teaching Methods: Flipped Classroom, Gamification, Case Study, Self-Learning, and Social Media. Educ. Sci. 2019, 9, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rahmi, W.; Othman, M. The Impact of Social Media use on Academic Performance among university students: A Pilot Study. J. Inf. Syst. Res. Innov. 2013, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Faghihi, U.; Brautigam, A.; Jorgenson, K.; Martin, D.; Brown, A.; Measures, E.; Maldonado-Bouchard, S. How Gamification Applies for Educational Purpose Specially with College Algebra. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2014, 41, 182–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuwala, J.; Sztekler, K. Implementation of case study method as an effective teaching tool in engineering education. In Proceedings of the IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON), Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Spain, 17–20 April 2018; pp. 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safapour, E.; Kermanshachi, S. The Effectiveness of Engineering Workshops on Attracting Hispanic Female Students to Construction Career Paths. In Proceedings of the Construction Research Congress 2020: Safety, Workforce, and Education, Tempe, AZ, USA, 8–10 March 2020; pp. 753–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usher, A. What Nontraditional Approaches Can Motivate Unenthusiastic Students? Center on Education Policy: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, A.G.; Creedy, D.K.; Sidebotham, M. Efficacy of teaching methods used to develop critical thinking in nursing and midwifery undergraduate students: A systematic review of the literature. Nurse Educ. Today 2016, 40, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- el Geddawy, Y.; Mikic-Fonte, F.; Llamas-Nistal, M.; Caeiro-Rodriguez, M. A review of personal teaching environments to support teaching activities. In Proceedings of the IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference, EDUCON 2020, Tempe, AZ, USA, 8–10 March 2020; pp. 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claro, M.; Salinas, A.; Cabello-Hutt, T.; Martín, E.S.; Preiss, D.D.; Valenzuela, S.; Jara, I. Teaching in a Digital Environment (TIDE): Defining and measuring teachers’ capacity to develop students’ digital information and communication skills. Comput. Educ. 2018, 121, 162–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kompen, R.T.; Edirisingha, P.; Canaleta, X.; Alsina, M.; Monguet, J.M. Personal learning Environments based on Web 2.0 services in higher education. Telemat. Inform. 2019, 38, 194–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañeda, L.; Dabbagh, N.; Torres-Kompen, R. Personal Learning Environments: Research-Based Practices, Frameworks and Challenges. J. New Approaches Educ. Res. 2017, 6, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balliu, V. Modern Teaching Versus Traditional Teaching-Albanian Teachers Between Challenges and Choices. Eur. J. Multidiscip. Stud. 2017, 2, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dimitrios, B.; Labros, S.; Nikolaos, K.; Maria, K.; Athanasios, K. Traditional teaching methods vs teaching through the application of information and communication technologies in the accounting field: Quo vadis? Eur. Sci. J. 2013, 9, 73–101. [Google Scholar]

- Parasuram, R.; Huiting, X.; Wang, J.; Thirumarban, A.; Eng, H.J.K.; Lien, P.C. Effectiveness of using non–traditional teaching methods to prepare student health care professionals for the delivery of the Mental State Examination: A systematic review protocol. JBI Database Syst. Rev. Implement. Rep. 2014, 12, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lage, M.J.; Platt, G.J.; Treglia, M. Inverting the Classroom: A Gateway to Creating an Inclusive Learning Environment. J. Econ. Educ. 2000, 31, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabulut-Ilgu, A.; Cherrez, N.J.; Jahren, C.T. A systematic review of research on the flipped learning method in engineering education. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2018, 49, 398–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, S.C.; Song, Y. An experience of personalized learning hub initiative embedding BYOD for reflective engagement in higher education. Comput. Educ. 2015, 88, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savery, J.R. Overview of Problem-based Learning: Definitions and Distinctions. Interdiscip. J. Probl. Learn. 2006, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hmelo-Silver, C.E. Problem-Based Learning: What and How Do Students Learn? Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2004, 16, 235–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, S. A recipe for meaningful gamification. In Gamification in Education and Business; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deterding, S.; Dixon, D.; Khaled, R.; Nacke, L. From game design elements to gamefulness: Defining ‘gamification. In Proceedings of the International Academic MindTrek Conference: Envisioning Future Media Environments, Tampere, Finland, 28–30 September 2011; pp. 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rule, P.; John, V. Your Guide to Case Study Research; Van Schaik Publishers: Pretoria, South Africa, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, A.M.; Haenlein, M. Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of Social Media. Bus. Horiz. 2010, 53, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gikas, J.; Grant, M.M. Mobile computing devices in higher education: Student perspectives on learning with cellphones, smartphones & social media. Internet High. Educ. 2013, 19, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slomanson, W.R. Blended Learning: A Flipped Classroom Experiment. J. Legal Educ. 2014, 64, 93. Available online: https://heinonline.org/HOL/Page?handle=hein.journals/jled64&id=97&div=10&collection=journals (accessed on 6 July 2022).

- Cieliebak, M.; Frei, A.K. Influence of flipped classroom on technical skills and non-technical competences of IT students. In Proceedings of the IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference, EDUCON, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 10–13 April 2016; pp. 1012–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roehl, A.; Reddy, S.L.; Shannon, G.J. Bridging the Field Trip Gap: Integrating Web-based Video as a Teaching and Learning Partner in Interior Design Education. J. Fam. Consum. Sci. 2013, 105, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roehl, A.; Reddy, S.L.; Shannon, G.J. The Flipped Classroom: An Opportunity To Engage Millennial Students Through Active Learning Strategies. J. Fam. Consum. Sci. 2013, 105, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.-H.; Wang, J.-P.; Wen, F.-J.; Wang, J.; Tao, J.-Q. Exploration and Practice of Blended Teaching Model Based Flipped Classroom and SPOC in Higher University. J. Educ. Pract. 2016, 7, 99–104. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1099547 (accessed on 6 July 2022).

- Moraros, J.; Islam, A.; Yu, S.; Banow, R.; Schindelka, B. Flipping for success: Evaluating the effectiveness of a novel teaching approach in a graduate level setting. BMC Med. Educ. 2015, 15, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mok, H.N. Teaching tip: The flipped classroom. J. Inf. Syst. Educ. 2014, 25, 7. Available online: https://ink.library.smu.edu.sg/sis_research/2363 (accessed on 6 July 2022).

- Raihanah, M.M. One Size Fits All?: SoTL and Flipped Learning. In e-Learning & Interactive Lecture: SoTL Case Studies in Malaysian HEIs; Embi, M.A., Ed.; Pusat Pengajaran & Teknologi Pembelajaran Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia: Bangi, Malaysia, 2015; pp. 234–238. [Google Scholar]

- Yen, T.-F. The Performance of Online Teaching for Flipped Classroom Based on COVID-19 Aspect. Asian J. Educ. Soc. Stud. 2020, 8, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergis, S.; Sampson, D.G.; Pelliccione, L. Investigating the impact of Flipped Classroom on students’ learning experiences: A Self-Determination Theory approach. Comput. Human Behav. 2018, 78, 368–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostaris, C.; Sergis, S.; Sampson, D.G.; Giannakos, M.; Pelliccione, L. Investigating the potential of the flipped classroom model in K-12 ICT teaching and learning: An action research study. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2017, 20, 261–273. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/jeductechsoci.20.1.261.pdf (accessed on 6 July 2022).

- Sajid, M.R.; Laheji, A.F.; Abothenain, F.; Salam, Y.; AlJayar, D.; Obeidat, A. Can blended learning and the flipped classroom improve student learning and satisfaction in Saudi Arabia? Int. J. Med. Educ. 2016, 7, 281–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, I.; Poikela, S. Evaluating Problem Based Learning Initiatives. In New Approaches to Problem-Based Learning: Revitalising Your Practice in Higher Education; Routledge: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Phumeechanya, N.; Wannapiroon, P. Design of Problem-based with Scaffolding Learning Activities in Ubiquitous Learning Environment to Develop Problem-solving Skills. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 116, 4803–4808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celik, P.; Onder, F.; Silay, I. The effects of problem-based learning on the students’ success in physics course. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 28, 656–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijsmans, P.; Schakel, A.H. The impact of attendance on first-year study success in problem-based learning. High. Educ. 2018, 76, 865–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherpereel, C.M.; Bowers, M.Y. Using critical problem based learning factors in an integrated undergraduate business curriculum: A business course success. Dev. Bus. Simul. Exp. Learn. Proc. Annu. ABSEL Conf. 2006, 33, 13–21. [Google Scholar]

- Masek, A.B.; Yamin, S.B. Problem Based Learning: A review of the monitoring and assessment model. In Proceedings of the IEEE 2010 2nd International Congress on Engineering Education (ICEED 2010), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 8–9 December 2010; pp. 171–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widyatiningtyas, R.; Kusumah, Y.S.; Sumarmo, U.; Sabandar, J. The impact of problem-based learning approach to senior high school students’ mathematics critical thinking ability. J. Math. Educ. 2015, 6, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moeller, S.; Spitzer, K.; Spreckelsen, C. How to configure blended problem based learning-results of a randomized trial. Med. Teach. 2010, 32, e328–e346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, C.E.; Tucker, C.S. The effects of player type on performance: A gamification case study. Comput. Human Behav. 2019, 91, 333–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göksün, D.O.; Gürsoy, G. Comparing success and engagement in gamified learning experiences via Kahoot and Quizizz. Comput. Educ. 2019, 135, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainuddin, Z.; Shujahat, M.; Haruna, H.; Chu, S.K.W. The role of gamified e-quizzes on student learning and engagement: An interactive gamification solution for a formative assessment system. Comput. Educ. 2020, 145, 103729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurgelaitis, M.; Čeponienė, L.; Čeponis, J.; Drungilas, V. Implementing gamification in a university-level UML modeling course: A case study. Comput. Appl. Eng. Educ. 2019, 27, 332–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landers, R.N.; Armstrong, M.B. Enhancing instructional outcomes with gamification: An empirical test of the Technology-Enhanced Training Effectiveness Model. Comput. Human Behav. 2017, 71, 499–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamari, J.; Shernoff, D.J.; Rowe, E.; Coller, B.; Asbell-Clarke, J.; Edwards, T. Challenging games help students learn: An empirical study on engagement, flow and immersion in game-based learning. Comput. Human Behav. 2016, 54, 170–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Er, E.; Orey, M. An exploratory study of student engagement in gamified online discussions. Comput. Educ. 2018, 120, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burguillo, J.C. Using game theory and Competition-based Learning to stimulate student motivation and performance. Comput. Educ. 2010, 55, 566–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonaci, A.; Klemke, R.; Lataster, J.; Kreijns, K.; Specht, M. Gamification of MOOCs Adopting Social Presence and Sense of Community to Increase User’s Engagement: An Experimental Study. In European Conference on Technology Enhanced Learning; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 11722 LNCS, pp. 172–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanmugam, M.; Abdullah, Z.; Mohamed, H.; Aris, B.; Zaid, N.M.; Suhadi, S.M. The affiliation between student achievement and elements of gamification in learning science. In Proceedings of the 2016 4th International Conference on Information and Communication Technology ICoICT, Bandung, Indonesia, 25–27 May 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lascano, S.K.; Núñez, J.H.; Esparragoza, I.E.; Schmidt, L.C.; Nagel, R.L. A Case Study Approach for Teaching Students Sustainability from a Global Perspective. Rev. Iberoam. Tecnol. del Aprendiz. 2015, 10, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iahad, N.A.; Mirabolghasemi, M.; Mustaffa, N.H.; Latif, M.S.A.; Buntat, Y. Student Perception of Using Case Study as a Teaching Method. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 93, 2200–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ruggiero, J.A. ‘Ah Ha...’ Learning: Using Cases and Case Studies to Teach Sociological Insights and Skills. Sociol. Pract. 2002, 4, 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tellis, W.M. Application of a Case Study Methodology. Qual. Rep. 1997, 3, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 1st ed.; Sage Publications: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Shankararaman, V.; Gottipati, S.; Megargel, A. Mini-Case Study Pedagogy: Experience from a Technical Course in an Information Systems Program. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference (FIE 2019), Covington, KY, USA, 16–19 October 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popil, I. Promotion of critical thinking by using case studies as teaching method. Nurse Educ. Today 2011, 31, 204–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, A.; Vinh, M.; Shaver, G.M.; Meckl, P.; Firebaugh, S. Case-based instruction: Improving students’ conceptual understanding through cases in a mechanical engineering course. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2014, 51, 659–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Diao, Y.; Zhang, J. Social media: Communication characteristics and application value in distance education. In Proceedings of the 2011 International Conference on Electrical and Control Engineering (ICECE), Yichang, China, 16–18 September 2011; pp. 6774–6777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelly, M.; Mataillet, H. Social media and the impact on education: Social media and home education. In Proceedings of the 2012 International Conference on E-Learning and E-Technologies in Education (ICEEE 2012), Lodz, Poland, 24–26 September 2012; pp. 236–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nini, E. Private open source social networking media for education. In Proceedings of the 2015 5th International Conference e-Learning, ECONF, Manama, Bahrain, 18–20 October 2015; pp. 220–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawot, N.I.M.; Ibrahim, R. A review of features and functional building blocks of social media. In Proceedings of the 2014 8th Malaysian Software Engineering Conference MySEC 2014, Langkawi, Malaysia, 23–24 September 2014; pp. 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sifi, S.; Alouane, R. Esprit-social network: An internal collaborative platform for the students of ESPRIT. In Proceedings of the IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON), Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 10–13 April 2016; pp. 563–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tess, P.A. The role of social media in higher education classes (real and virtual)—A literature review. Comput. Human Behav. 2013, 29, A60–A68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, S.; Waycott, J.; Kurnia, S.; Chang, S. Understanding students’ perceptions of the benefits of online social networking use for teaching and learning. Internet High. Educ. 2015, 26, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laserna, M.S.S.; Miguel, M.C. Social media as a teaching innovation tool for the promotion of interest and motivation in higher education. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Symposium on Computers in Education (SIIE 2018), Jerez, Spain, 19–21 September 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermudez, C.M.; Prasad, P.W.C.; Alsadoon, A.; Hourany, L. Students perception on the use of social media to learn English within secondary education in developing countries. In Proceedings of the IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON), Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 10–13 April 2016; pp. 968–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celik, I.; Akilli, G.K.; Onuk, T.C. Social media for academics: Motivation killer or booster? In Proceedings of the IEEE 14th International Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies ICALT, Athens, Greece, 7–10 July 2014; pp. 480–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, J.L.; Verleger, M.A. The flipped classroom: A survey of the research. In Proceedings of the 120th ASEE Annual Conference and Exposition, Atlanta, GA, USA, 23–26 June 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fassbinder, A.G.d.; Moreira, D.; Cruz, G.; Barbosa, E.F. Tools for the flipped classroom model: An experiment in teacher education. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference (FIE 2015), El Paso, TX, USA, 21–24 October 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehring, J. Present Research on the Flipped Classroom and Potential Tools for the EFL Classroom. Interdiscip. J. Pract. Theory Appl. Res. 2016, 33, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainuddin, Z.; Halili, S.H. Flipped Classroom Research and Trends from Different Fields of Study. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 2016, 17, 313–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakosimos, K.E. Example of a micro-adaptive instruction methodology for the improvement of flipped-classrooms and adaptive-learning based on advanced blended-learning tools. Educ. Chem. Eng. 2015, 12, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasnim, W.N.; Hussin, W.; Harun, J.; Shukor, N.A. Problem Based Learning to Enhance Students Critical Thinking Skill via Online Tools. Asian Soc. Sci. 2018, 15, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hmelo-Silver, C.E.; Lajoie, S.P.; Chan, L.-K.; Khurana, C.; Lu, J.; Cruz-Panesso, I.; Wiseman, J. Using online digital tools and video to support international problem-based learning. In Proceedings of the Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Hilton Waikoloa Village, AK, USA, 3–6 January 2018; pp. 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, H. Utilizing Computer-mediated Communication Tools for Problem-based Learning. Int. Forum Educ. Technol. Soc. 2009, 12, 205–213. [Google Scholar]

- Maican, C.; Lixandroiu, R.; Constantin, C. Interactivia.ro—A study of a gamification framework using zero-cost tools. Comput. Human Behav. 2016, 61, 186–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soboleva, E.V.; Galimova, E.G.; Maydangalieva, Z.A.; Batchayeva, K.K.M. Didactic Value of Gamification Tools for Teaching Modeling as a Method of Learning and Cognitive Activity at School. Eurasia J. Math. Sci. Technol. Educ. 2018, 14, 2427–2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiryakova, G.; Angelova, N.; Yordanova, L. Gamification in education. In Proceedings of the 9th International Balkan Education and Science Conference, Edirne, Turkey, 16–18 October 2014; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Bullon, J.J.; Encinas, A.H.; Sánchez, M.J.S.; Martinez, V.G. Analysis of student feedback when using gamification tools in math subjects. In Proceedings of the IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON), Canary Islands, Spain, 17–20 April 2018; pp. 1818–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prud’homme-Généreux, A. Assembling a case study tool kit: 10 tools for teaching with cases. Education 2016, 20, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, K.; Varma, V. A study of the effectiveness of case study approach in software engineering education. In Proceedings of the 20th Conference on Software Engineering Education & Training (CSEET′07), Dublin, Ireland, 3–5 July 2007; pp. 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, I.; Shankararaman, V. Case studies in computing education: Presentation, evaluation and assessment of four case study-based course design and delivery models. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference, Madrid, Spain, 22–25 October 2015; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y. Improving software engineering courses with case study approach. In Proceedings of the 2010 5th International Conference on Computer Science & Education, Hefei, China, 24–27 August 2010; pp. 1633–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, J.A.N.; Khan, N.A. Exploring the role of social media in collaborative learning the new domain of learning. Smart Learn. Environ. 2020, 7, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baruah, T.D. Effectiveness of Social Media as a tool of communication and its potential for technology enabled connections: A micro-level study. Int. J. Sci. Res. Publ. 2012, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Reimers, F.; Schleicher, A.; Saavedra, J.; Tuominen, S. Supporting the Continuation of Teaching and Learning during the COVID-19 Pandemic; OECD: Paris, France, 2020; Volume 1, pp. 1–38. [Google Scholar]

| Paper Type | Studied Methods | References |

|---|---|---|

| Systematic review | Flipped classroom, gamification, case study, and social media-centered | [12] |

| Report—evaluative | Flipped classroom, problem-based learning, social media-centered and gamification | [17] |

| Systematic review | Problem-based learning, and case study | [18] |

| Type | Example |

|---|---|

| Blogs | MicroBlog, Edutopia, Wabisabilearning |

| Wikis | Wikipedia |

| Social media network | Facebook, Twitter, WhatsApp |

| Content Communities | Youtube, TeacherTube, SlideShare |

| Activities | Tool Type | Tool Example | Explanation of Use | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preclass Activities | Capture | Android Camera Laptop Camera Zoom Application | Teachers can use these tools to record lectures that highlight critical ideas, explain the subject, and facilitate the pace of a given curriculum map. | [84,85,86,87,88] |

| Edit | Adobe Premiere Vimeo Corel VideoStudio | These editing tools are for making videos look more professional by trimming the unwanted parts. | [84,85,86,87,88] | |

| Publish | YouTube Teacher Tube | These tools work as platforms for hosting videos by uploading them and interacting with the comments of students under the video. | [84,85,86,87,88] | |

| Find | YouTube Google Search | These tools work as databases of videos that can be useful for the teaching and learning of the teacher and students. | [84,85,86,87,88] | |

| Share | Facebook | These tools are used to share videos with students. Teachers need to make it engaging and clear. | [85,86,87] | |

| In-Class Activities | Quizzes, Questions | Kahoot! Quizzes Socrative | These tools can be used to build a quiz or use an existing one already in the database to make the quiz fun and interactive. Once the quiz code is shared, students can be encouraged to take a quiz during the class. | [84,85,86,87,88] |

| Discussions | Zoom Microsoft Teams Cisco Webex | Teachers can use these tools to divide the students into small discussion groups to work on shared tasks. Teachers can start with all students on the same video call, and with a simple click of a button, split students up into small groups to discuss a topic. These tools promote online collaborative learning. | [84,85,86,87,88] | |

| Presentation | PowerPoint Prezi | Teachers can illustrate the difficult parts through presentation tools and comment on a student’s presentation as a feedback feature. | [84,85,86,87,88] | |

| Post Class Activities | Calendar | Google Calendar | Teachers can share important dates and office hours available for after-class questions and discussions with students. | [85,87] |

| Chat | Telegram | Teachers can simply ask their students questions to be answered through the chat tools. This function is useful for brainstorming and online exercise activities. | [85,87] | |

| Material share | Dropbox Google Drive | Teachers can upload all the materials needed for the subject to these tools and share them with students. Additionally, they can edit or delete them anytime, and access students’ documents and presentations. | [84,85,87,88] |

| Activities | Tool Type | Tool Example | Explanation of Use | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Define the problem and identify learning issues | Search | Google search Bing Khan academy | Teachers can use these tools to search for information regarding the problem design. | [89,90,91] |

| Processing | Word Google docs | Teachers can use these tools to write down the problem description and identify the learning outcomes. Moreover, they can read and edit students’ work on the same tool. | [89] | |

| Presentation | PowerPoint Prezi | Teachers can illustrate the problem, the materials required to follow through with presentation tools, and comment on student’s presentation as a feedback feature. | [89,91] | |

| Share | Facebook | Teachers can share ideas with the students’ groups and comment on their questions. | [89,91] | |

| Material | Dropbox Google Drive | Teachers can use these tools as free online tools to save the data needed for facilitating the process of solving a problem. They can also share docs, presentations, audios, and videos with students via two-way communication. | [89,91] | |

| Resources | MERLOT YouTube Khan academy | Multimedia teaching and learning repository, loaded with a lot of material that can be offered to students to aid with the solutions. | [89,91] | |

| To-Do List | Microsoft To Do Google Tasks | These tools help teachers and students focus on the target and be aware of the deadlines. | [89] | |

| Divide students into groups or individuals | Discussions | Zoom Cisco Webex Blogger | Teachers need to observe students’ discussion meetings or blogs to support them and guide them through the learning process. Zoom and Cisco are free tools for online video conferencing. Blogger can help the teacher reach students’ discussions and brainstorming posts. | [89,91] |

| Chat | Messenger | For immediate help, these tools are freely available to chat with students’ teams, and teachers will observe so they can answer questions. | [89,91] | |

| Creating questions Observe students learning to make suggestions Give feedback | Questions | Kahoot! Quizzes Socrative | Teachers can use these tools to understand students’ knowledge during the learning process to make sure that they are on the right track. | [84,89,91] |

| Brainstorming Mind Maps | Ideaboardz Mindmap | Teachers can aid problem-solving mind maps of students to help them represent their thinking and to make it easier to observe students’ thinking, as it facilitates the brainstorming process by visualization. It plays a vital role in the analysis of the problem and the identification of potential solutions. | [89,91] | |

| Flowcharts | App. Diagrams Lucidchart | Teachers can aid flowcharts of students to illustrate what happens at each stage of the problem-solving process and how each event affects other events and their decisions. | [89] | |

| Assessment of the students | Presentation Discussion | Prezi Zoom | Teachers can use these tools for formative and summative assessment of students by presenting the work and discussing the alternative solutions. | [89,91] |

| Activities | Tool Type | Tool Example | Explanation of Use | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Problem Definition, describe the game elements and set up a points system | Search | Google Bing | Teachers can use these tools to search for information regarding the design of the game. | [92,93,94] |

| Processing | Word | Teachers need to write down the ideas and the planning required to build the game, collect all found data and information in a document file to see the whole image of the description of the game elements, and set up the goals. | [92,93,94,95] | |

| Retrieve | Dropbox Google Drive | Teachers may use these tools to retrieve a previous game design or data that they might need while building the new game. | [93,94,95] | |

| Discuss | Blogs | Teachers may need the help of peers and teachers that use the same methodology. They can do that with the help of finding a Facebook group or a blog that shares some information about the subject that the teacher is trying to build. | [92,93,94,95] | |

| Resources | Khan Academy Question banks YouTube | These tools provide teachers with many resources, materials, videos, and questions that may help in the planning of the game design. Teachers can also provide their students with such resources for preparing them for the quizzes and a better learning experience. | [92,93,94,95] | |

| Calendar | Google Calendar | Teachers can share the important dates of upcoming assignments, quizzes, or exams with students. | [93,94] | |

| Design the game and select the game elements | Create, Edit | Kahoot! Quzizz Socrative GimKit | For creating the game, teachers need the help of some free tools built for gamification. These tools use music, images, and a colorful interface to get students excited about the task at hand. Some tools such as Kahoot! allow teachers to include YouTube videos to add some information to each question. Each question may have a timer or a stopwatch. | [92,93,94,95] |

| Share | Facebook | Teachers can share the QR code or the link of the quiz with students so they complete them at a specific time. | [92,93,94,95] | |

| Observe and communication | Chat | Zoom Microsoft Teams | Teachers can use gamification in class or using online tools such as Zoom to facilitate the reach for all students. | [92,93,94] |

| Assessment and Feedback | Capture Analysis Scores Rewards Grading | Kahoot! Quzizz Socrative GimKit | These tools allow students to receive points for every correct answer and also receive extra points for answering faster than others. Teachers can use the leaderboard and the analysis that tools create to grade the students and reward them. | [92,93,94,95] |

| Activities | Tool Type | Tool Example | Explanation of Use | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identify a problem to investigate | Search cases | thecasecentre.org apus.libanswers Bing | The problem should be challenging and complex enough to yield multiple solutions. The teacher can search these databases for ideas and useful information. | [66,72,73,97,98] |

| Video illustrating | YouTube TeacherTube | Teachers can find or record a video and upload it to these tools that illustrate the problem in hand to students to summarize the case. | [66,72,97,98,99] | |

| Processing | Google docs Word | Teachers can use it to observe and correct student’s mistakes in their documents. | [66,72,98,99] | |

| To-do List Calendar | Google Calendar | Teachers will need these tools to identify the case milestones for the students. Additionally, teachers can share with students the critical dates and office hours available for questions and discussions | [66,98,99] | |

| Resources | Encyclopedia | It consists of a massive amount of data that can be useful for writing a case study analysis. | [66,72,98,99] | |

| Share | Facebook | Teachers can use these tools to share essential data regarding the case (e.g., videos, documents, and useful websites) | [66,98] | |

| Observe students learning | Writing check | Grammarly | This tool can help a lot at the stage of writing a text. The teacher can use it both ways for checking his/her mistakes and while assessing students writing with many suggestions. | [66,97,98] |

| Plagiarism check | Quetext | Teachers may use this tool to check for plagiarized content. | [66,73,98,99] | |

| Surveys Questionnaire | Google Form | Teachers can use surveys for collecting important feedback from students and to check the results collected by the students according to their proposed solutions for guidance. | [66,73,98,99] | |

| Interview Discussion Chat | Zoom Blogger | Teachers can use Zoom as an interview method. Teachers can extend the discussion by commenting and asking questions in blogs or Facebook groups. Alternatively, they can use a quick chat to guide the group on a specific topic. | [66,72,73,97,98,99] | |

| Presenting solutions and assessment | Questions | Kahoot! Socrative | Teachers can make the presentation of the work funny by starting with answering questions using gamification tools such as Kahoot! | [66,72,73,97,98,99] |

| Rubric | Quickrubric rubric-maker iRubric | These tools are a scoring guide used to assess the quality of students’ constructed responses. Teachers can use them for the formative or summative assessment of the students. | [66,73,98,99] |

| Activities | Tool Type | Tool Example | Explanation of Use | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teaching networks | Connect with peers | Classroom 2.0 | Teachers can connect through using Classroom 2.0. It is a social network for teachers. Teachers can chat, send messages, and exchange ideas on how to best teach students. | [82,83,84,85,86,89] |

| Academia.edu ResearchGate | Teachers can use it to connect with peers whose primary goal is to share research papers or follow researchers to read their new research or to collaborate. | |||

| A professional social forum for searching with the same interest for potential collaborations. Teachers can message the targeted person through their profiles. | ||||

| VoiceThread | Teachers can upload and share images, videos, and documents with students or peers. Teachers can have an online conversation about each other’s posts through audio, video, or text comments. | |||

| Create and publish content | Capture | Android Camera Laptop Camera Zoom application | Teachers can use these tools to record lectures that highlight critical ideas explaining the subject. | [82,83,84,86] |

| Publish | YouTube TeacherTube Vimeo | YouTube has a special section dedicated to teachers and how to teach with it. TeacherTube has tabs for documents and audio, and they are one of the more useful resources within it. | [82,83,84,86] | |

| Share | Facebook | Teachers can use these tools to share created content with a group of students. | [82,83,84,86] | |

| Listening and responding | Read and comment | Facebook Blogger YouTube | All the social media tools now can connect and communicate through many features such as commenting and liking posts and sharing. Teachers can use these features to reach and comment on posts that need collaboration. | [82,86] |

| Dashboards | TweetDeck | With this tool, teachers can view multiple timelines in one easy interface, schedule tweets for posting in the future, and build tweet collections. | [84,86,89] | |

| Video conferencing | Zoom Application Microsoft Teams | Teachers can use these tools to discuss with peers or students. | [84,87] | |

| Content analyzing and comparing | Charts Data analysis | Facebook page analysis | Teachers can create a page to see the students’ engagement and analyze the views and comments among the different posts for future improvements. | [84,86,91] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

El Geddawy, Y.; Mikic-Fonte, F.A.; Llamas-Nistal, M.; Caeiro-Rodríguez, M. Introducing Personal Teaching Environment for Nontraditional Teaching Methods. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 7596. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12157596

El Geddawy Y, Mikic-Fonte FA, Llamas-Nistal M, Caeiro-Rodríguez M. Introducing Personal Teaching Environment for Nontraditional Teaching Methods. Applied Sciences. 2022; 12(15):7596. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12157596

Chicago/Turabian StyleEl Geddawy, Yasser, Fernando A. Mikic-Fonte, Martín Llamas-Nistal, and Manuel Caeiro-Rodríguez. 2022. "Introducing Personal Teaching Environment for Nontraditional Teaching Methods" Applied Sciences 12, no. 15: 7596. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12157596

APA StyleEl Geddawy, Y., Mikic-Fonte, F. A., Llamas-Nistal, M., & Caeiro-Rodríguez, M. (2022). Introducing Personal Teaching Environment for Nontraditional Teaching Methods. Applied Sciences, 12(15), 7596. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12157596