Assessment of Communication Quality through Work Authorization between Dentists and Dental Technicians in Fixed and Removable Prosthodontics

Abstract

:1. Introduction

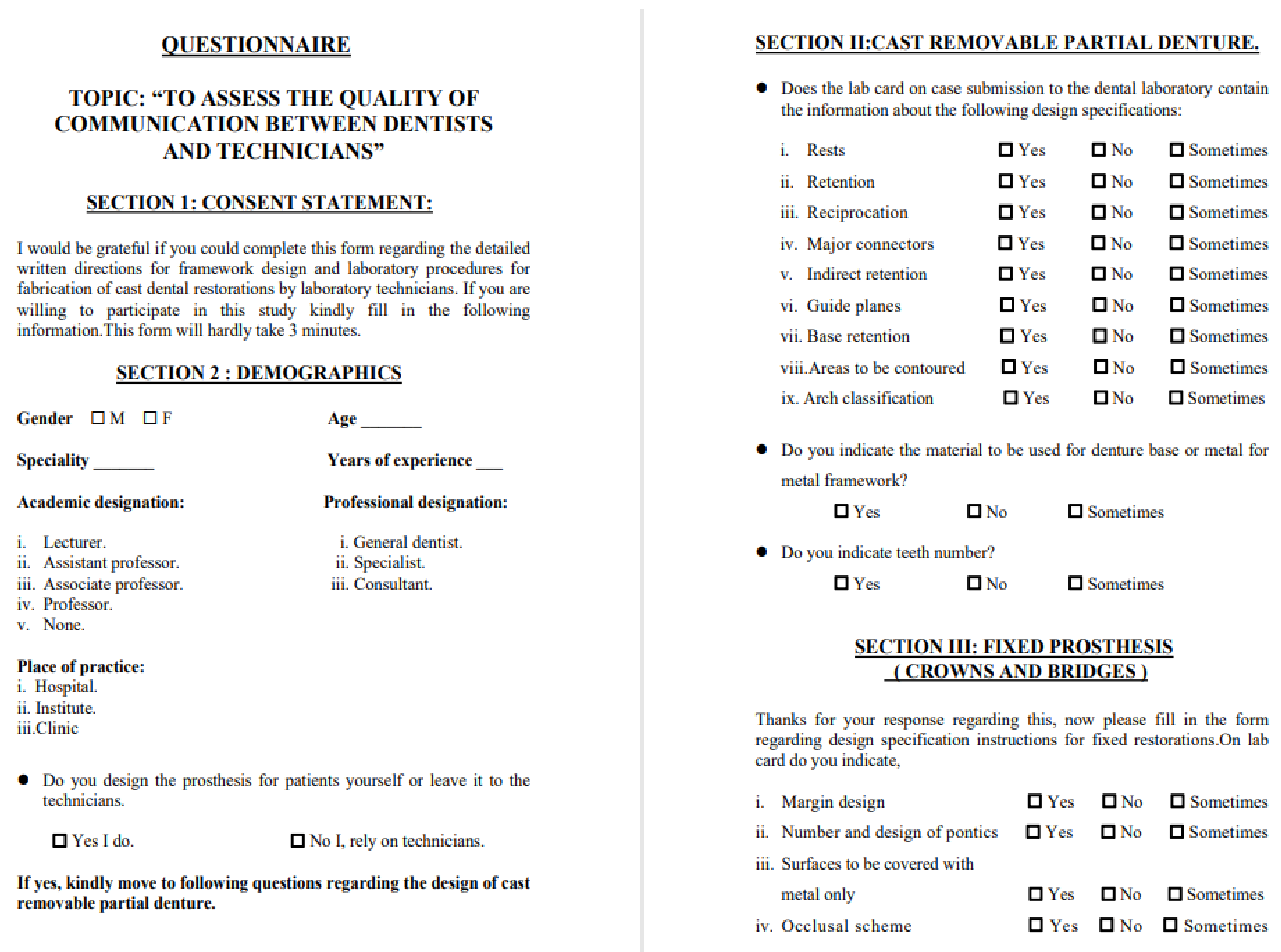

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Douglass, C.W.; Jette, A.M.; Fox, C.H.; Tennstedt, S.L.; Joshi, A.; Feldman, H.A.; McGuire, S.M.; McKinlay, J.B. Oral health status of the elderly in New England. J. Gerontol. 1993, 48, M39–M46. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/geronj/article-lookup/doi/10.1093/geronj/48.2.M39 (accessed on 9 February 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenkins, S.J.; Lynch, C.D.; Sloan, A.J.; Gilmour, A.S.M. Quality of prescription and fabrication of single-unit crowns by general dental practitioners in Wales. J. Oral Rehabil. 2009, 36, 150–156. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1365-2842.2008.01916.x (accessed on 9 February 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owall, B.; Budtz-Jörgensen, E.; Davenport, J.; Mushimoto, E.; Palmqvist, S.; Renner, R.; Afrodite, S.; Bernd, W. Removable partial denture design: A need to focus on hygienic principles? Int. J. Prosthodont. 2002, 15, 371–378. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12170852 (accessed on 10 February 2022). [PubMed]

- Stewart, C.A. An audit of dental prescriptions between clinics and dental laboratories. Br. Dent. J. 2011, 211, E5. Available online: http://www.nature.com/articles/sj.bdj.2011.623 (accessed on 20 February 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farah, J.W.; Dootz, E.; Mora, G.; Gregory, W. Insights of dental technicians: A survey of business and laboratory relations with dentists. Dentistry 1991, 8, 17–18, 20, 23. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1813276 (accessed on 14 February 2022).

- Sappe’, H.; Smith, D.S. Dental Laboratory Technology. Project Report Phase I with Research Findings. 1989. Available online: https://www.science.gov/topicpages/d/dental+laboratory+technology (accessed on 22 February 2022).

- Parry, G.R.; Evans, J.L.; Cameron, A. Communicating prosthetic prescriptions from dental students to the dental laboratory: Is the message getting through? J. Dent. Educ. 2014, 78, 1636–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeper, S.H. Dentist and laboratory: A “love-hate” relationship. Dent. Clin. N. Am. 1979, 23, 87–99. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/365636 (accessed on 23 February 2022). [CrossRef]

- Al-AlSheikh, H.M. Quality of communication between dentists and dental technicians for fixed and removable prosthodontics. King Saud Univ. J. Dent. Sci. 2012, 3, 55–60. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2210815712000194 (accessed on 13 February 2022). [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Haj-Ali, R.; Al Quran, F.; Adel, O. Dental laboratory communication regarding removable dental prosthesis design in the UAE. J. Prosthodont. 2012, 21, 425–428. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1532-849X.2011.00842.x (accessed on 20 February 2022). [CrossRef]

- Lynch, D.; Allen, P.F. Quality of written prescriptions and master impressions for fixed and removable prosthodontics: A comparative study. Br. Dent. J. 2005, 198, 17–20. Available online: http://www.nature.com/articles/4811947 (accessed on 21 February 2022). [CrossRef]

- Lynch, C.D.; Allen, P.F. A survey of chrome-cobalt RPD design in Ireland. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2003, 16, 362–364. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12956488 (accessed on 27 February 2022). [PubMed]

- Lynch, C.D.; Allen, P.F. Quality of materials supplied to dental laboratories for the fabrication of cobalt chromium removable partial dentures in Ireland. Eur. J. Prosthodont. Restor. Dent. 2003, 11, 176–180. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14737795 (accessed on 10 March 2022). [PubMed]

- Aquilino, S.A.; Taylor, T.D. Prosthodontic laboratory and curriculum survey. Part III: Fixed prosthodontic laboratory survey. J. Prosthet. Dent. 1984, 52, 879–885. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0022391384800256 (accessed on 1 March 2022). [CrossRef]

- Afsharzand, Z.; Rashedi, B.; Petropoulos, V.C. Communication between the dental laboratory technician and dentist: Work authorization for fixed partial dentures. J. Prosthodont. 2006, 15, 123–128. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1532-849X.2006.00086.x (accessed on 10 March 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juszczyk, A.S.; Clark, R.K.F.; Radford, D.R. UK dental laboratory technicians’ views on the efficacy and teaching of clinical-laboratory communication. Br. Dent. J. 2009, 206, E21. Available online: http://www.nature.com/articles/sj.bdj.2009.434 (accessed on 10 March 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azzopardi, L.; Zarb, M.; Alzoubi, E.E. Quality of communication between dentists and dental laboratory technicians in Malta. Xjenza 2020, 8, 39–46. Available online: www.xjenza.org (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Dolnicar, S.; Grün, B.; Leisch, F. Quick, simple and reliable: Forced binary survey questions. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2011, 53, 231–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itoh, H.; Baba, K.; Aridome, K.; Okada, D.; Tokuda, A.; Nishiyama, A.; Miura, H.; Igarashi, Y. Effect of direct retainer and major connector designs on RPD and abutment tooth movement dynamics. J. Oral Rehabil. 2008, 35, 810–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preshaw, P.M.; Walls, A.W.; Jakubovics, N.S.; Moynihan, P.J.; Jepson, N.J.; Loewy, Z. Association of removable partial denture use with oral and systemic health. J. Dent. 2011, 39, 711–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.F.; Ahmed Khan, F.N.; Lone, M.A.; Hussain, M.W.; Shaikh, M.A.; Shaikh, I.A. Knowledge and attitude regarding designing removable partial denture among interns and dentist; dental schools in Pakistan. J. Pak. Dent. Assoc. 2020, 29, 66–70. Available online: http://www.jpda.com.pk/knowledge-and-attitude-regarding-designing-removable-partial-denture-among-interns-and-dentist-dental-schools-in-pakistan/ (accessed on 10 March 2022). [CrossRef]

- Suresan, V.; Mantri, S.; Deogade, S.; Sumathi, K.; Panday, P.; Galav, A.; Mishra, K. Denture hygiene knowledge, attitudes, and practices toward patient education in denture care among dental practitioners of Jabalpur city, Madhya Pradesh, India. J. Indian Prosthodont. Soc. 2016, 16, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudd, R.W.; Rudd, K.D. A review of 243 errors possible during the fabrication of a removable partial denture: Part I. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2001, 86, 251–261. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S002239130123025X (accessed on 10 March 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mamoun, J.S. The path of placement of a removable partial denture: A microscope based approach to survey and design. J. Adv. Prosthodont. 2015, 7, 76. Available online: https://jap.or.kr/DOIx.php?id=10.4047/jap.2015.7.1.76 (accessed on 10 March 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- American Dental Association. Statement of Prosthetic Care and Dental Laboratories; Merican Dental Association: Chicago, IL, USA, 2011; Volume 159. [Google Scholar]

- Sadek, S.A.; Dehis, W.M.; Hassan, H. Different materials used as denture retainers and their colour stability. Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 2018, 6, 2173–2179. Available online: https://spiroski.migration.publicknowledgeproject.org/index.php/mjms/article/view/oamjms.2018.415 (accessed on 10 March 2022). [CrossRef]

- Tulbah, H.; AlHamdan, E.; AlQahtani, A.; AlShahrani, A.; AlShaye, M. Quality of communication between dentists and dental laboratory technicians for fixed prosthodontics in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Dent. J. 2017, 29, 111–116. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1013905217300378 (accessed on 17 March 2022). [CrossRef]

- Halawani, S.; Al-Harbi, S. Marginal adaptation of fixed prosthodontics. Int. J. Med. Dev. Ctries. 2017, 1, 78–84. Available online: https://www.ejmanager.com/fulltextpdf.php?mno=287543 (accessed on 17 March 2022). [CrossRef]

- Piloto, P.; Alves, A.; Correia, A.; Campos, J.; Fernandes, J.; Vaz, M.; Viriato, N. Metal ceramic fixed partial denture: Fracture resistance. Biodent Eng. 2010, 2010, 125–128. Available online: http://bibliotecadigital.ipb.pt/handle/10198/1723 (accessed on 15 March 2022).

- Elshahawy, W.; Watanabe, I. Biocompatibility of dental alloys used in dental fixed prosthodontics. Tanta Dent. J. 2014, 11, 150–159. Available online: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1687857414000407 (accessed on 15 March 2022). [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mohammed, A.O.; Mohammed, G.S.; Mathew, M.; Alzarea, B.; Bandela, V. Shade Selection in Esthetic Dentistry: A Review. Cureus 2022, 14, e23331. Available online: https://www.cureus.com/articles/90547-shade-selection-in-esthetic-dentistry-a-review (accessed on 10 March 2022). [CrossRef]

- Warreth, A.; Elkareimi, Y. All-ceramic restorations: A review of the literature. Saudi Dent. J. 2020, 32, 365–372. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1013905220300110 (accessed on 15 March 2022). [CrossRef]

- Carr, A.B.; McGivney, G.P.; Brown, D.T. Removable Partial Prosthodontics; Elsevier Mosby: Maryland Heights, MO, USA, 2005; Volume 11. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, G.J. Improving dentist-technician interaction and communication. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2009, 140, 475–478. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0002817714621024 (accessed on 14 March 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Demographics | n% | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 173 (38.2%) |

| Female | 280 (61.8%) | |

| Specialty | Dentistry | 437 (96.5%) |

| Others | 16 (3.5%) | |

| Academic Designation | Lecturer | 63 (13.9%) |

| Assistant Professor | 58 (12.8%) | |

| Associate Professor | 12 (2.6%) | |

| Professor | 9 (2.0%) | |

| Non-teaching dentist | 311 (68.7%) | |

| Professional Designation | General Dentist | 414 (91.4%) |

| Specialist | 23 (5.1%) | |

| Consultant | 16 (3.5%) | |

| Place of Practice | Hospital | 198 (43.7%) |

| Institute | 247 (54.5%) | |

| Clinic | 8 (1.8%) |

| Variables | Yes | No | Sometimes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rests | 310 (68.4%) | 98 (21.9%) | 39 (8.7%) |

| Retention | 301 (67.3%) | 111 (24.8%) | 35 (7.8%) |

| Reciprocation | 227 (52.4%) | 152 (35.1%) | 54 (12.5%) |

| Major connectors | 269 (60.2%) | 128 (28.6%) | 50 (11.2%) |

| Indirect retention | 242 (55.0%) | 144 (31.8%) | 54 (12.3%) |

| Guide planes | 228 (51.8%) | 144 (32.7%) | 68 (15.5%) |

| Base retention | 256 (58.2%) | 140 (31.8%) | 44 (10.0%) |

| Areas to be contoured | 228 (51.8%) | 111 (25.2%) | 101 (23.0%) |

| Arch classification | 270 (61.4%) | 88 (20.0%) | 82 (18.6%) |

| Material to be used for denture base or metal for metal framework? | 323 (72.3%) | 48 (10.7%) | 76 (17.0%) |

| Indicate teeth number? | 379 (83.7%) | 32 (7.2%) | 31 (7.0%) |

| Variables | Yes (n%) | No (n%) | Sometimes (n%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Margin design | 296 (67.7%) | 75 (17.2%) | 66 (15.1%) |

| Number and design of pontics | 325 (73.5%) | 73 (16.5%) | 44 (10.0%) |

| Surfaces to be covered with metal only | 281 (64.9%) | 74 (17.1%) | 78 (18.0%) |

| Occlusal scheme | 274 (62.0%) | 78 (17.2%) | 90 (20.4%) |

| Shade | 365 (82.6%) | 35 (7.9%) | 42 (9.5%) |

| Bisque trial | 202 (46.2%) | 146 (33.4%) | 89 (20.4%) |

| Type of porcelain glaze | 184 (41.6%) | 185 (41.9%) | 73 (16.5%) |

| Ceramo-metal coping design | 188 (42.5%) | 183 (41.4%) | 71 (16.1%) |

| Type of metal alloy | 171 (39.1%) | 204 (46.7%) | 62 (14.2%) |

| Do you ask for a metal trial? | 302 (69.1%) | 49 (11.2%) | 86 (19.7%) |

| Do you communicate with the technician directly? | 348 (79.6%) | 31 (7.1%) | 58 (13.3%) |

| Are you satisfied with the restoration design you receive? | 182 (42.3%) | 61 (14.2%) | 187 (43.5%) |

| Do you change your dental laboratory frequently? | 67 (15.6%) | 290 (67.4%) | 73 (17.0%) |

| Variables | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Std. Error | Beta | |||

| Gender | −0.056 | 0.030 | −0.086 | −1.831 | 0.068 |

| Age | −0.007 | 0.005 | −0.083 | −1.430 | 0.153 |

| Specialty | 0.129 | 0.080 | 0.075 | 1.610 | 0.108 |

| Experience | 0.004 | 0.007 | 0.033 | 0.576 | 0.565 |

| Academic designation | 0.027 | 0.010 | 0.136 | 2.764 | 0.006 |

| Professional designation | −0.030 | 0.038 | −0.040 | −0.784 | 0.434 |

| Place of practice | −0.028 | 0.029 | −0.046 | −0.954 | 0.340 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Afzal, H.; Ahmed, N.; Lal, A.; Al-Aali, K.A.; Alrabiah, M.; Alhamdan, M.M.; Albahaqi, A.; Sharaf, A.; Vohra, F.; Abduljabbar, T. Assessment of Communication Quality through Work Authorization between Dentists and Dental Technicians in Fixed and Removable Prosthodontics. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 6263. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12126263

Afzal H, Ahmed N, Lal A, Al-Aali KA, Alrabiah M, Alhamdan MM, Albahaqi A, Sharaf A, Vohra F, Abduljabbar T. Assessment of Communication Quality through Work Authorization between Dentists and Dental Technicians in Fixed and Removable Prosthodontics. Applied Sciences. 2022; 12(12):6263. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12126263

Chicago/Turabian StyleAfzal, Hadiqa, Naseer Ahmed, Abhishek Lal, Khulud A. Al-Aali, Mohammed Alrabiah, Mai M. Alhamdan, Ahmed Albahaqi, Abdulaziz Sharaf, Fahim Vohra, and Tariq Abduljabbar. 2022. "Assessment of Communication Quality through Work Authorization between Dentists and Dental Technicians in Fixed and Removable Prosthodontics" Applied Sciences 12, no. 12: 6263. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12126263

APA StyleAfzal, H., Ahmed, N., Lal, A., Al-Aali, K. A., Alrabiah, M., Alhamdan, M. M., Albahaqi, A., Sharaf, A., Vohra, F., & Abduljabbar, T. (2022). Assessment of Communication Quality through Work Authorization between Dentists and Dental Technicians in Fixed and Removable Prosthodontics. Applied Sciences, 12(12), 6263. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12126263