Influence Analysis of Simulation Parameters on Numerical Prediction of Compressible External Flow Field Based on NACA0012 Airfoil under Hypersonic Speed

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- The influences of airfoil geometrical changes and attitudes on the external flow field properties, including temperature, temperature-related coefficients, force coefficients, and acoustic noise.

- The aerodynamic characteristics of the turbines and special purpose airfoils, the shapes of which are similar to NACA0012 airfoils.

- The investigation on related property prediction approaches.

2. CFD Simulations

- CPU: AMD Ryzen 7 5800X 8-core.

- RAM: Kingston DDR4 64G.

- SSD: Intel 760p 512G + Kingston A2000 1T.

- OS: WIN10 64 professional version.

- CFD simulation tool: Ansys fluent, double-precision, and 8-core parallel processing calculation.

2.1. Grid Strategy

2.1.1. NACA0012 Models and External Flow Field of the Computational Domain

- Airfoil tools, which refers to the UIUC Airfoil coordinates database and provides 132 data points. It should be noted that the ends of the established NACA0012 trailing edge based on Airfoil tools are not closed, and we need to connect the ends manually to form the blunt trailing edge. If the ends of the trailing edge are not connected, after being imported into meshing tools, a blunt elliptic shape will be formed at the trailing edge of the generated two-dimensional airfoil, failing mesh generation

- NACA 4-digit airfoil generator, which provides a maximum of 200 data points. It gives a close trailing edge option to form the sharp trailing edge.

- The definition formula, which is Equation (1), where x is the x-axis location and y is the y-axis location.

- The NACA4-digital generator.

- The definition formula applies 132 data points provided by Airfoil tools.

- The definition formula applies 200 data points provided by the NACA4 generator.

- The definition formula applies 264 data points. We double the 132 points provided by Airfoil tools to 264 points by adding the average value between two points.

- The definition formula applies 400 data points by doubling 200 points from NACA4.

2.1.2. Gird Division

2.1.3. Mesh Parameters

2.2. Numerical Methods

2.2.1. Turbulence Models

2.2.2. Flux Type

- ROE flux-difference splitting scheme [30]. At each face, the discrete flux is expressed as:

- AUSM flux-vector splitting scheme [31], which provides a numerical flux form to avoid using explicit artificial dissipation.

2.3. Numerical Simulations

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. NACA0012 Models

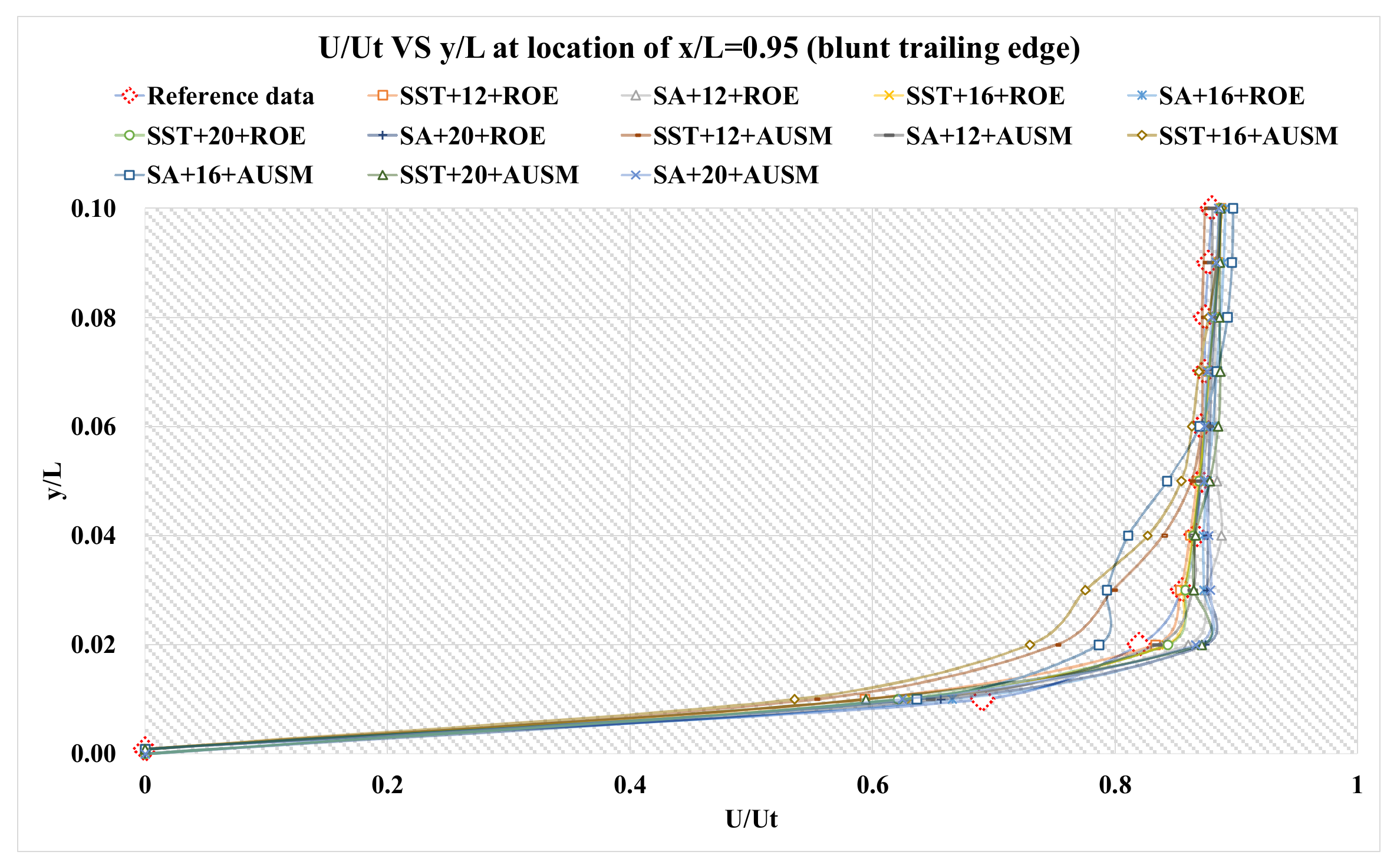

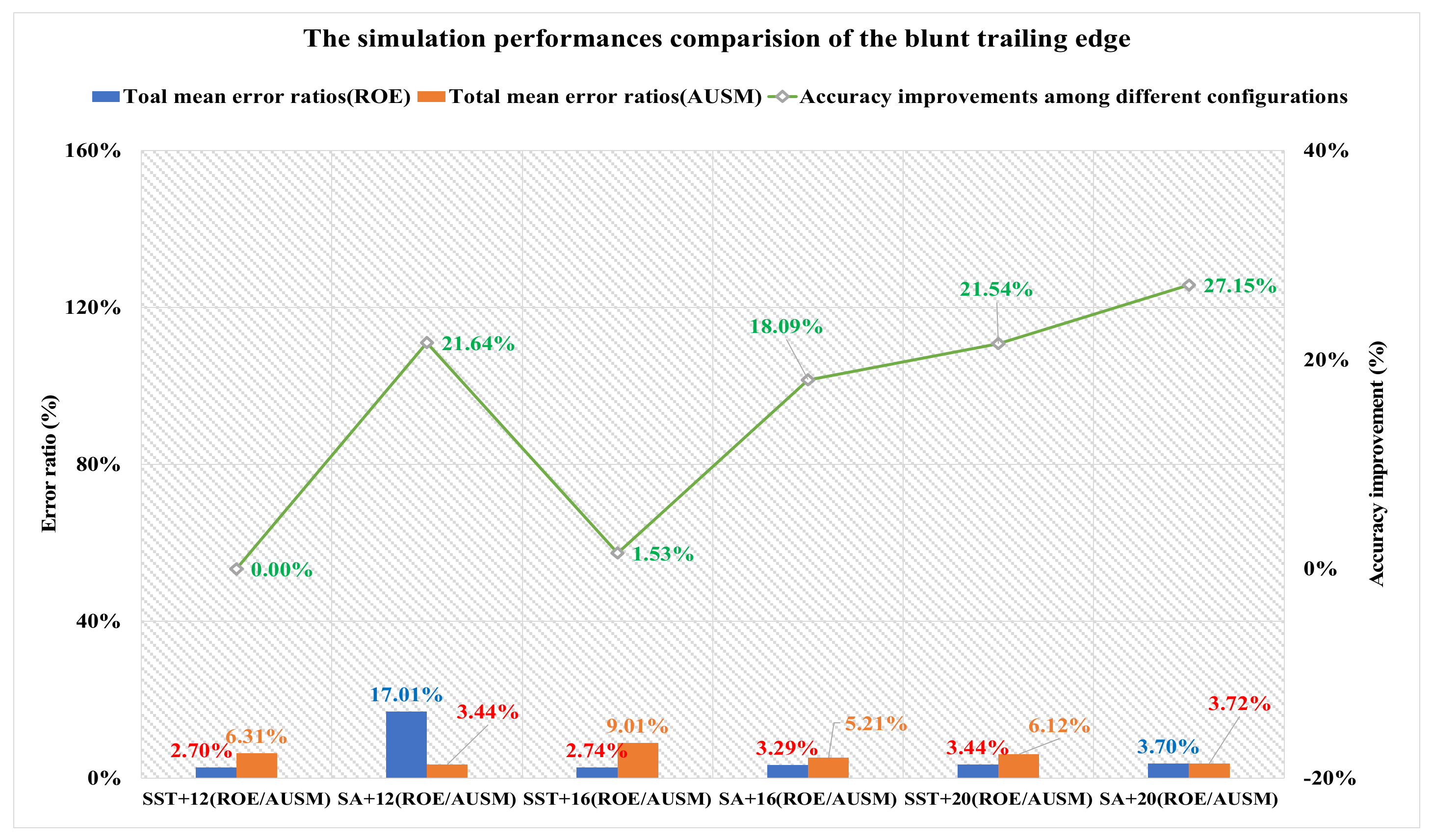

3.1.1. Results of the Blunt Trailing Edge

| Simulation Configurations | Mean Error Ratios under Different Configurations | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ROE | AUSM | |||||

| P/Pt | T/Tt | U/Ut | P/Pt | T/Tt | U/Ut | |

| SST + 12 m | 1.97% | 4.52% | 1.60% | 8.94% | 5.91% | 4.07% |

| SA + 12 m | 24.04% | 24.61% | 2.39% | 3.62% | 5.56% | 1.14% |

| SST + 16 m | 2.20% | 4.49% | 2.74% | 8.16% | 13.63% | 5.25% |

| SA + 16 m | 3.52% | 4.38% | 3.29% | 5.89% | 6.11% | 3.63% |

| SST + 20 m | 5.27% | 3.36% | 3.44% | 9.47% | 6.02% | 2.86% |

| SA + 20 m | 6.40% | 2.70% | 3.70% | 7.27% | 1.68% | 2.22% |

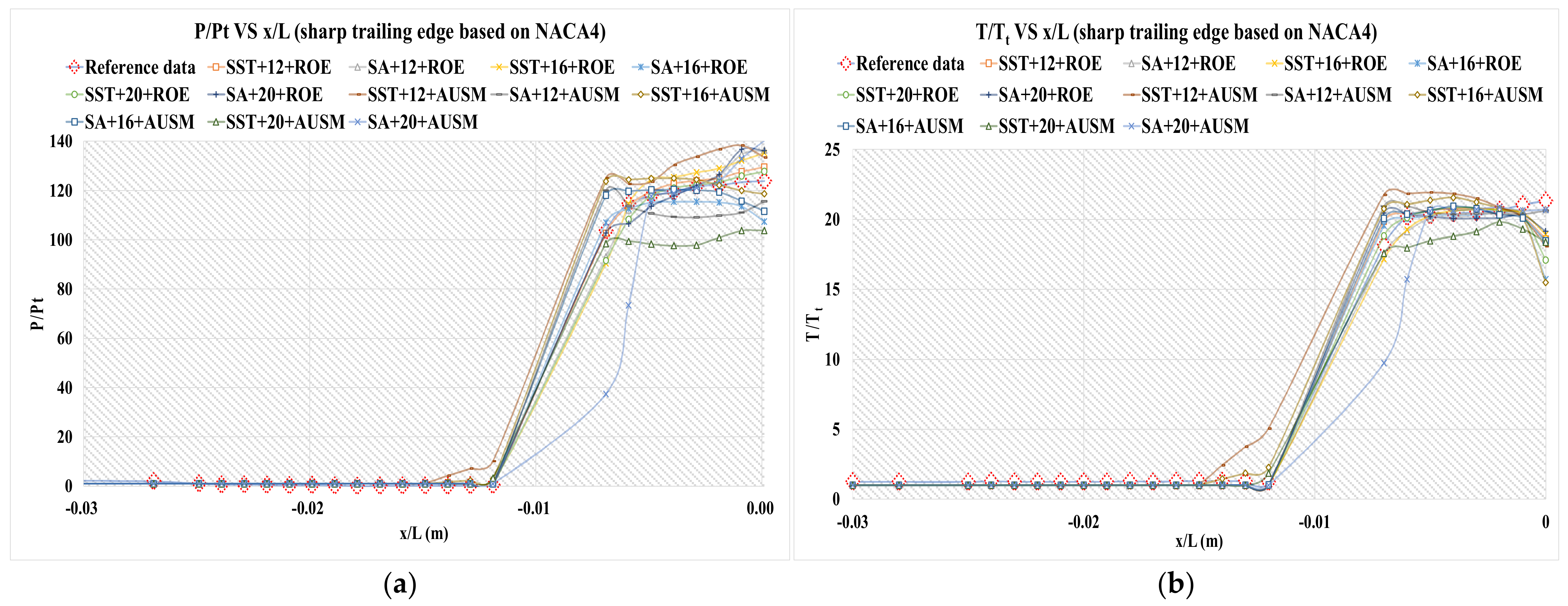

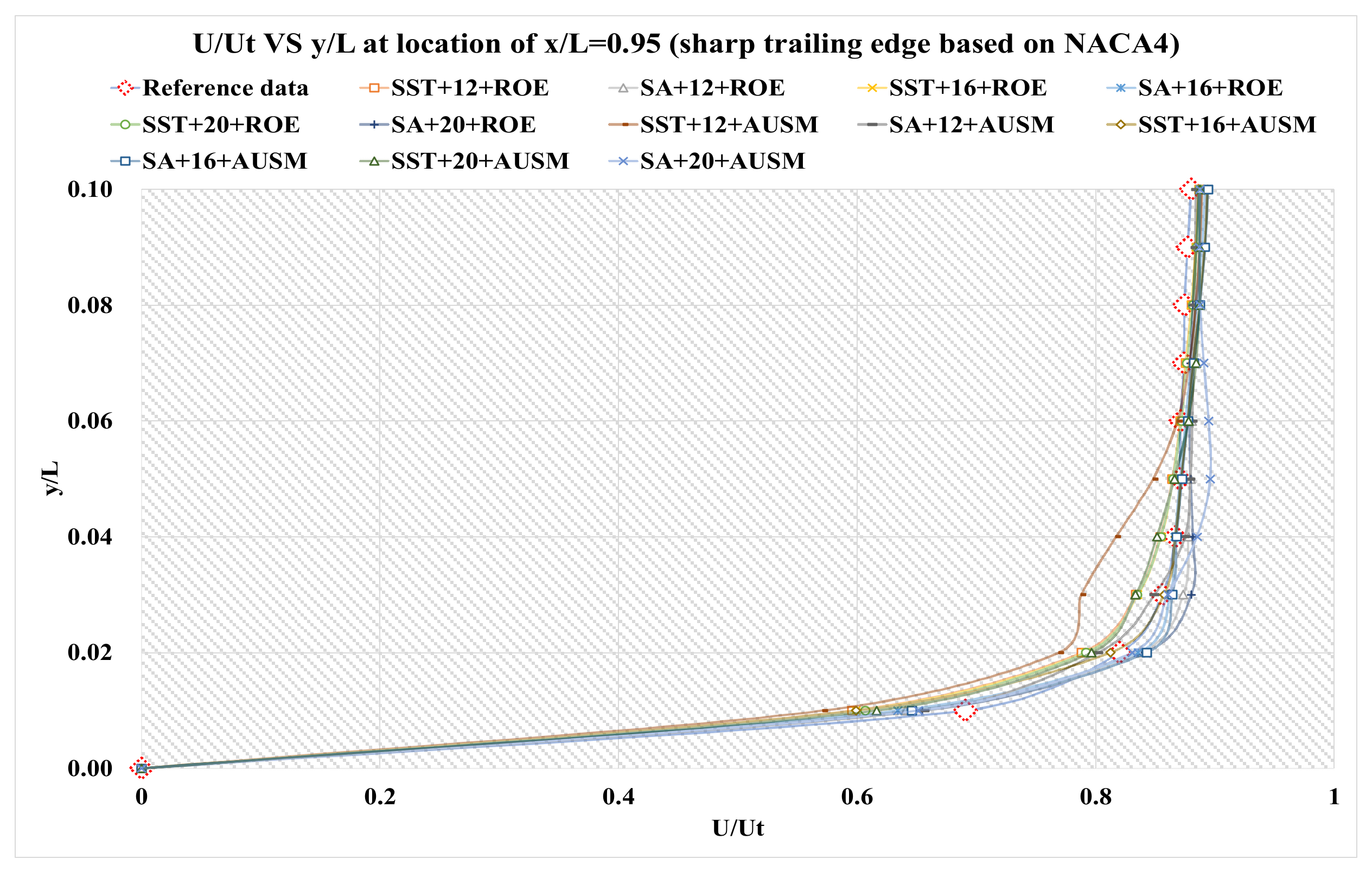

3.1.2. Results of the Sharp Trailing Edge Based on NACA4-Digital Generator

| Simulation Configurations | Mean Error Ratios under Different Configurations | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ROE | AUSM | |||||

| P/Pt | T/Tt | U/Ut | P/Pt | T/Tt | U/Ut | |

| SST + 12 m | 2.28% | 3.96% | 1.04% | 10.41% | 8.54% | 4.38% |

| SA + 12 m | 4.42% | 2.16% | 1.90% | 8.52% | 3.55% | 1.40% |

| SST + 16 m | 6.23% | 3.25% | 2.36% | 5.96% | 8.19% | 2.07% |

| SA + 16 m | 5.33% | 5.24% | 1.61% | 5.12% | 4.57% | 1.71% |

| SST + 20 m | 3.15% | 4.14% | 2.28% | 15.30% | 8.00% | 2.38% |

| SA + 20 m | 4.69% | 4.28% | 1.73% | 15.45% | 9.74% | 2.06% |

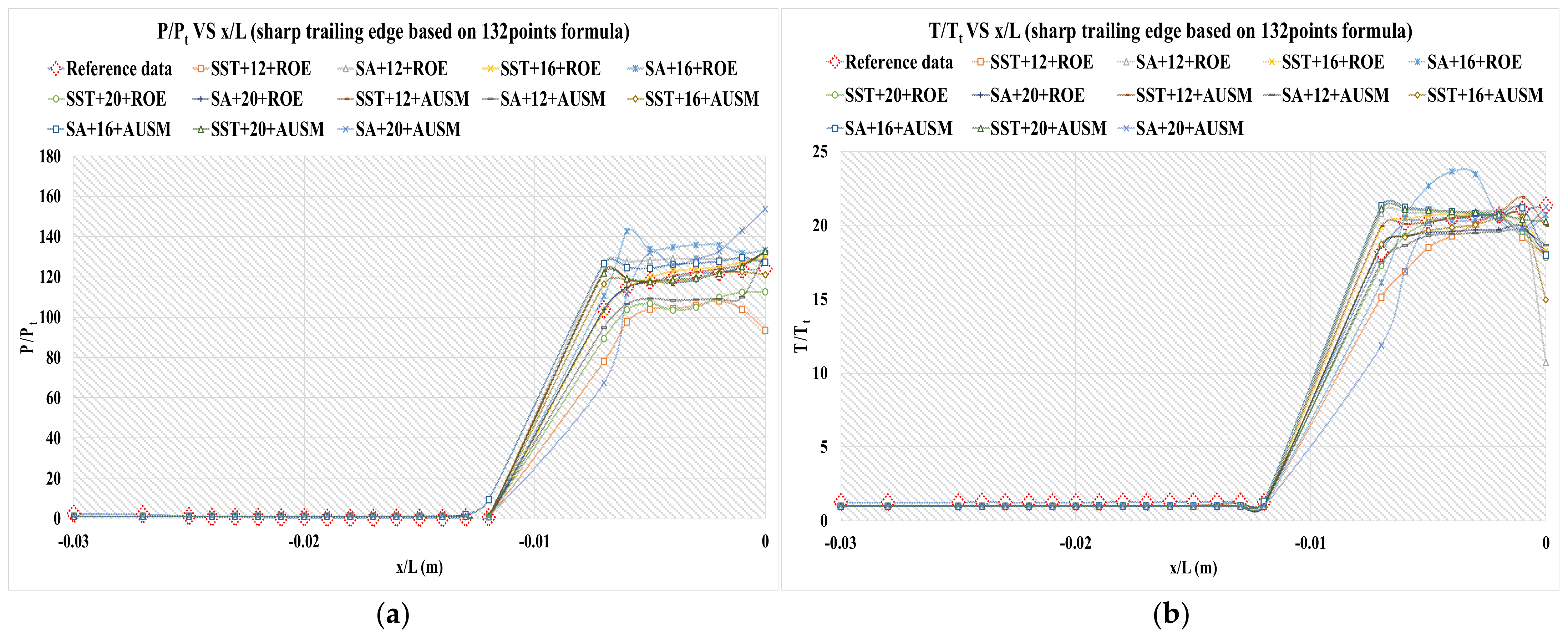

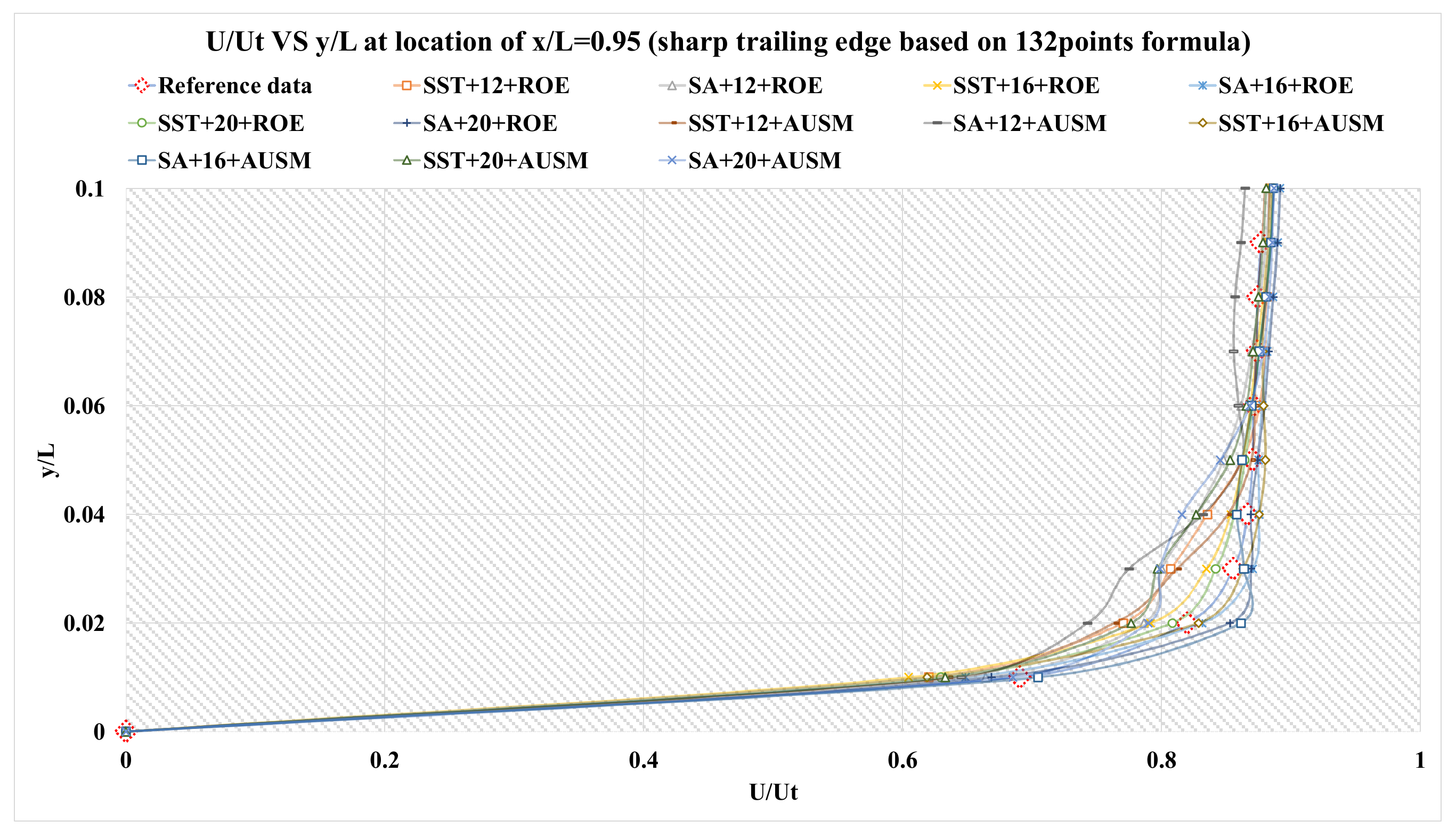

3.1.3. Results of the Sharp Trailing Edge Based on Definition Formula Applying 132 Points

| Simulation Configurations | Mean Error Ratios under Different Configurations | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ROE | AUSM | |||||

| P/Pt | T/Tt | U/Ut | P/Pt | T/Tt | U/Ut | |

| SST + 12 m | 16.13% | 9.27% | 2.95% | 4.32% | 2.88% | 2.21% |

| SA + 12 m | 8.58% | 9.70% | 2.41% | 8.91% | 6.31% | 3.91% |

| SST + 16 m | 2.14% | 4.21% | 1.57% | 2.78% | 6.14% | 1.78% |

| SA + 16 m | 11.85% | 8.20% | 1.66% | 7.32% | 5.83% | 1.26% |

| SST + 20 m | 11.00% | 4.36% | 1.61% | 4.14% | 4.64% | 2.83% |

| SA + 20 m | 1.76% | 5.58% | 1.59% | 13.73% | 7.50% | 2.34% |

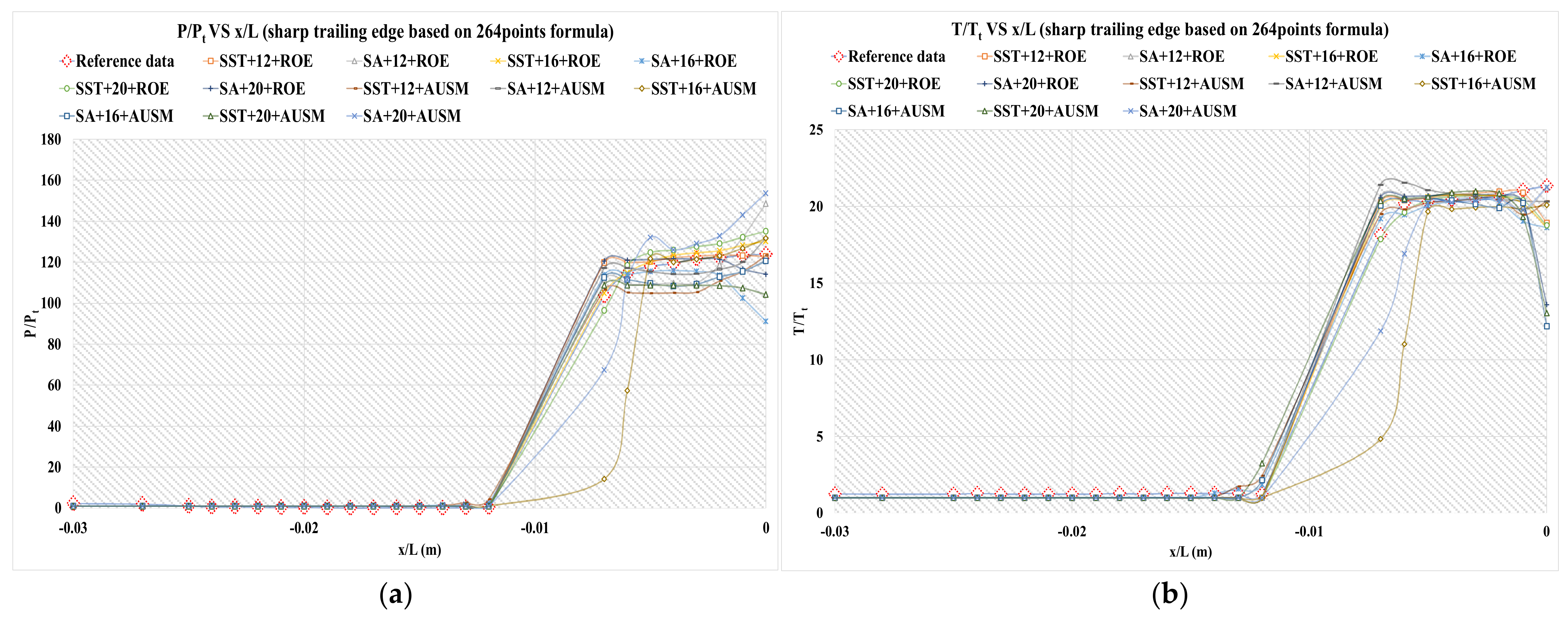

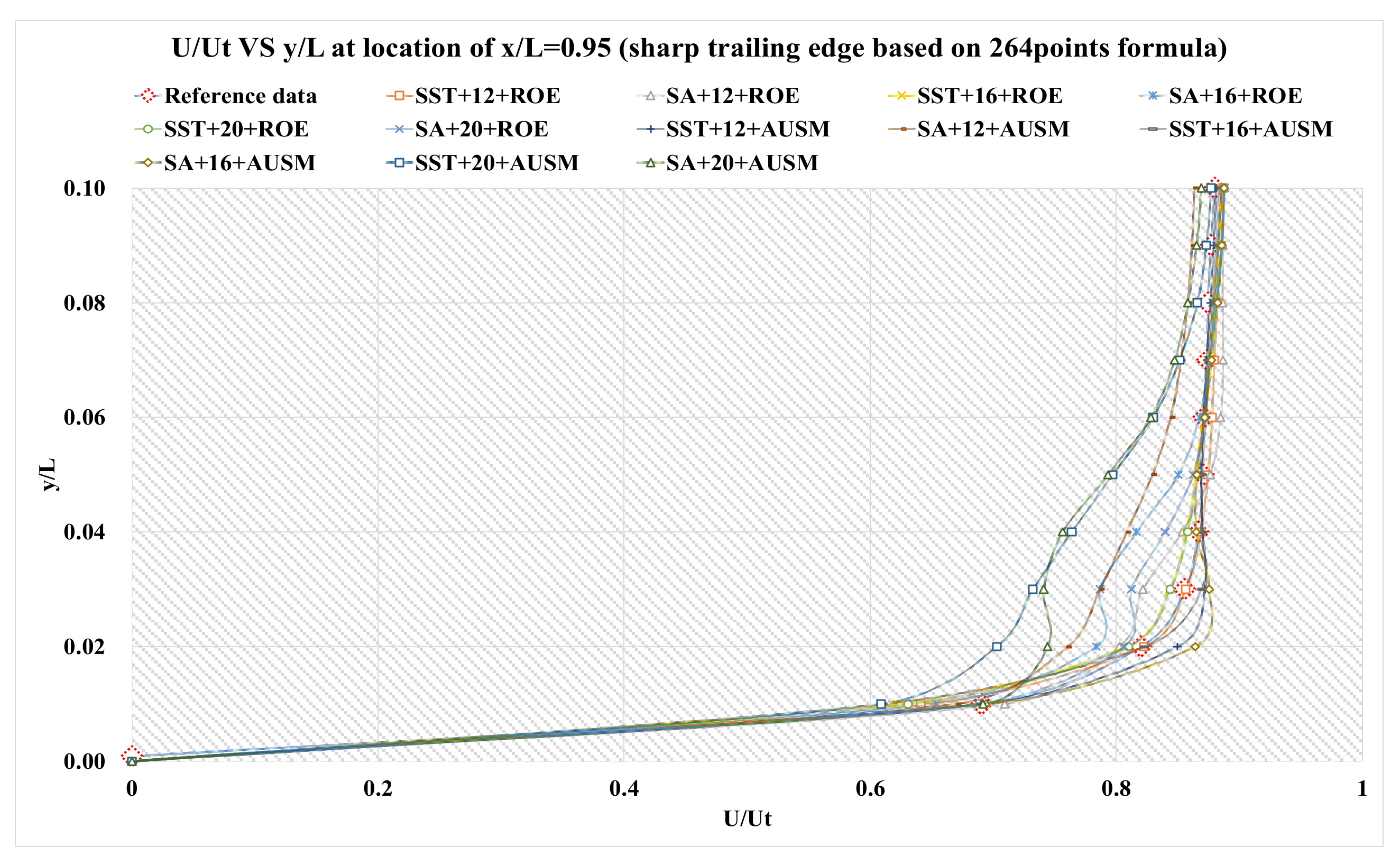

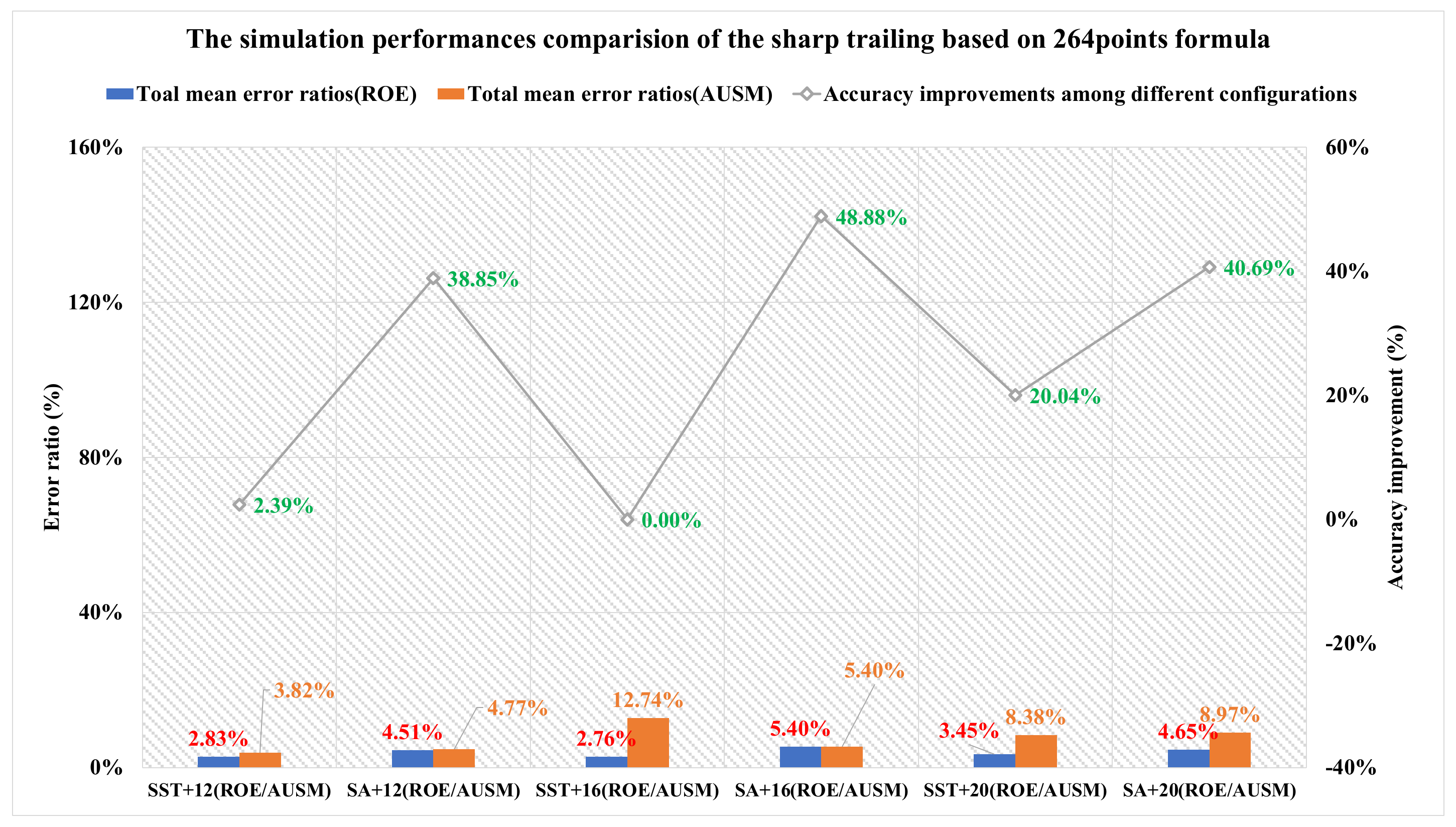

3.1.4. Results of the Sharp Trailing Edge Based on Definition Formula Applying 264 Points

| Simulation Configurations | Mean Error Ratios under Different Configurations | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ROE | AUSM | |||||

| P/Pt | T/Tt | U/Ut | P/Pt | T/Tt | U/Ut | |

| SST + 12 m | 3.44% | 3.81% | 1.23% | 7.95% | 2.81% | 0.70% |

| SA + 12 m | 8.42% | 3.39% | 1.73% | 5.19% | 5.03% | 4.08% |

| SST + 16 m | 2.62% | 4.00% | 1.65% | 18.77% | 17.84% | 1.62% |

| SA + 16 m | 8.82% | 4.45% | 2.92% | 6.81% | 8.17% | 1.23% |

| SST + 20 m | 6.03% | 2.75% | 1.56% | 9.67% | 8.47% | 6.99% |

| SA + 20 m | 5.11% | 7.58% | 1.26% | 13.73% | 7.50% | 5.67% |

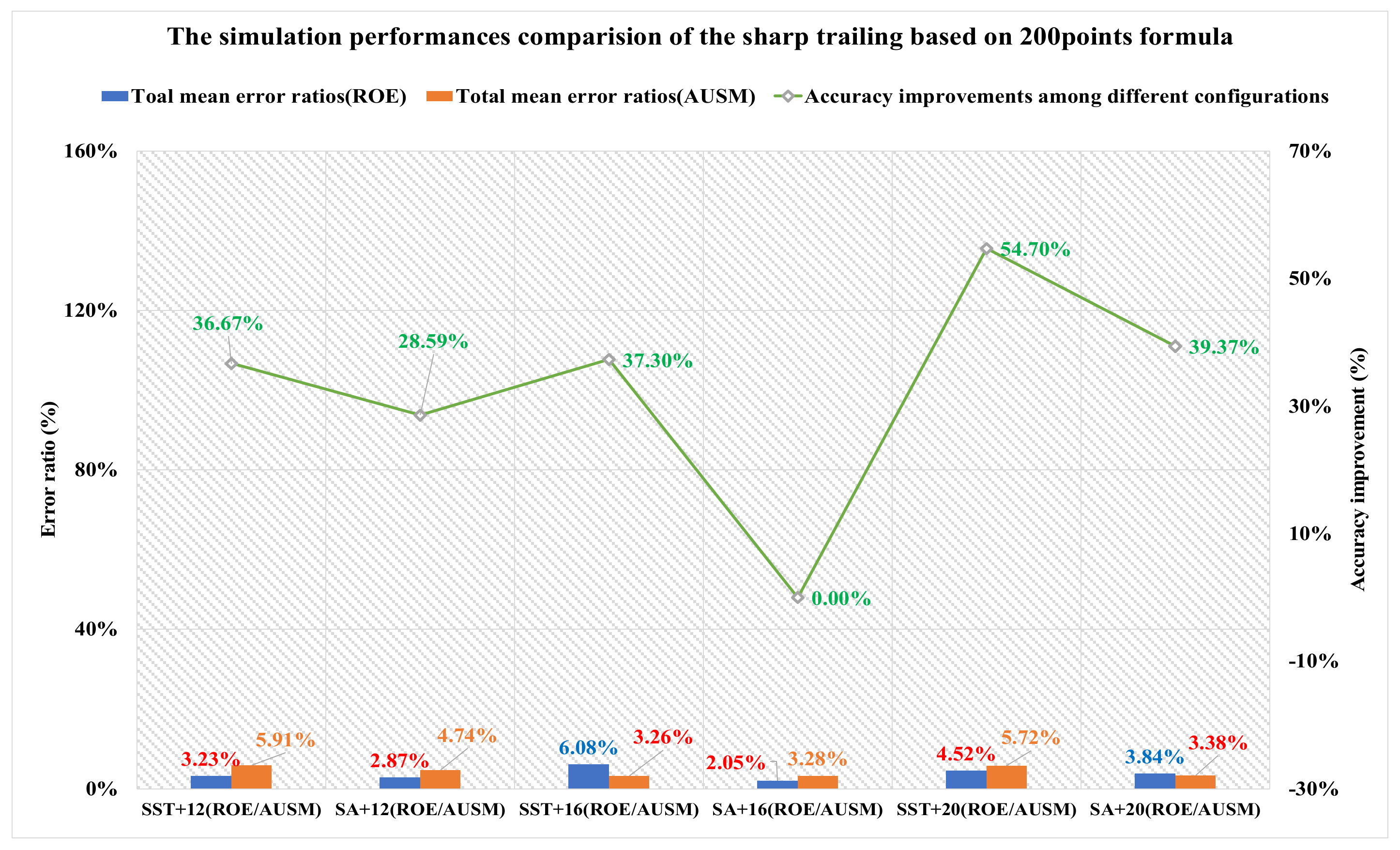

3.1.5. Results of the Sharp Trailing Edge Based on Definition Formula Applying 200 Points

| Simulation Configurations | Mean Error Ratios under Different Configurations | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ROE | AUSM | |||||

| P/Pt | T/Tt | U/Ut | P/Pt | T/Tt | U/Ut | |

| SST + 12 m | 4.86% | 3.88% | 0.96% | 8.02% | 7.94% | 1.77% |

| SA + 12 m | 5.87% | 1.18% | 1.55% | 7.83% | 4.63% | 1.76% |

| SST + 16 m | 8.58% | 7.83% | 1.83% | 3.74% | 4.06% | 2.00% |

| SA + 16 m | 2.54% | 1.86% | 1.74% | 4.79% | 3.75% | 1.29% |

| SST + 20 m | 5.02% | 6.54% | 1.99% | 9.84% | 5.13% | 2.19% |

| SA + 20 m | 6.00% | 4.32% | 1.21% | 3.51% | 4.13% | 2.48% |

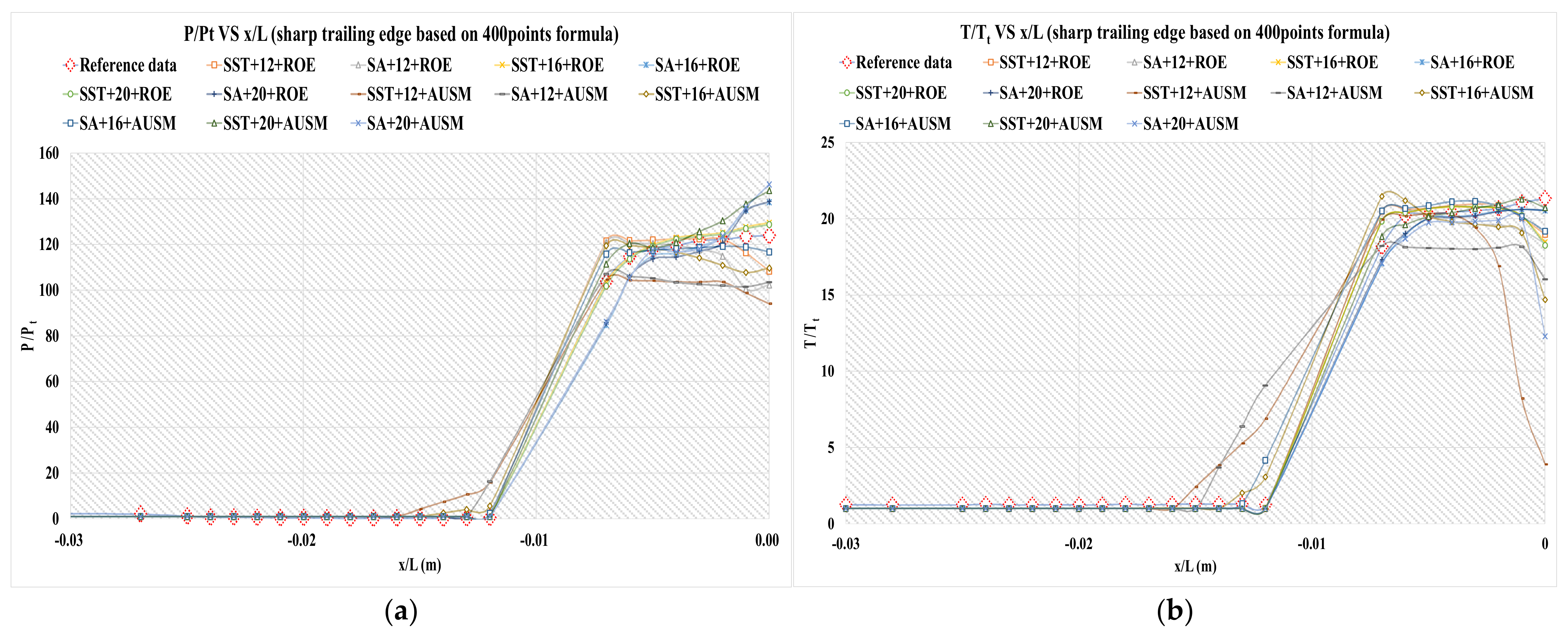

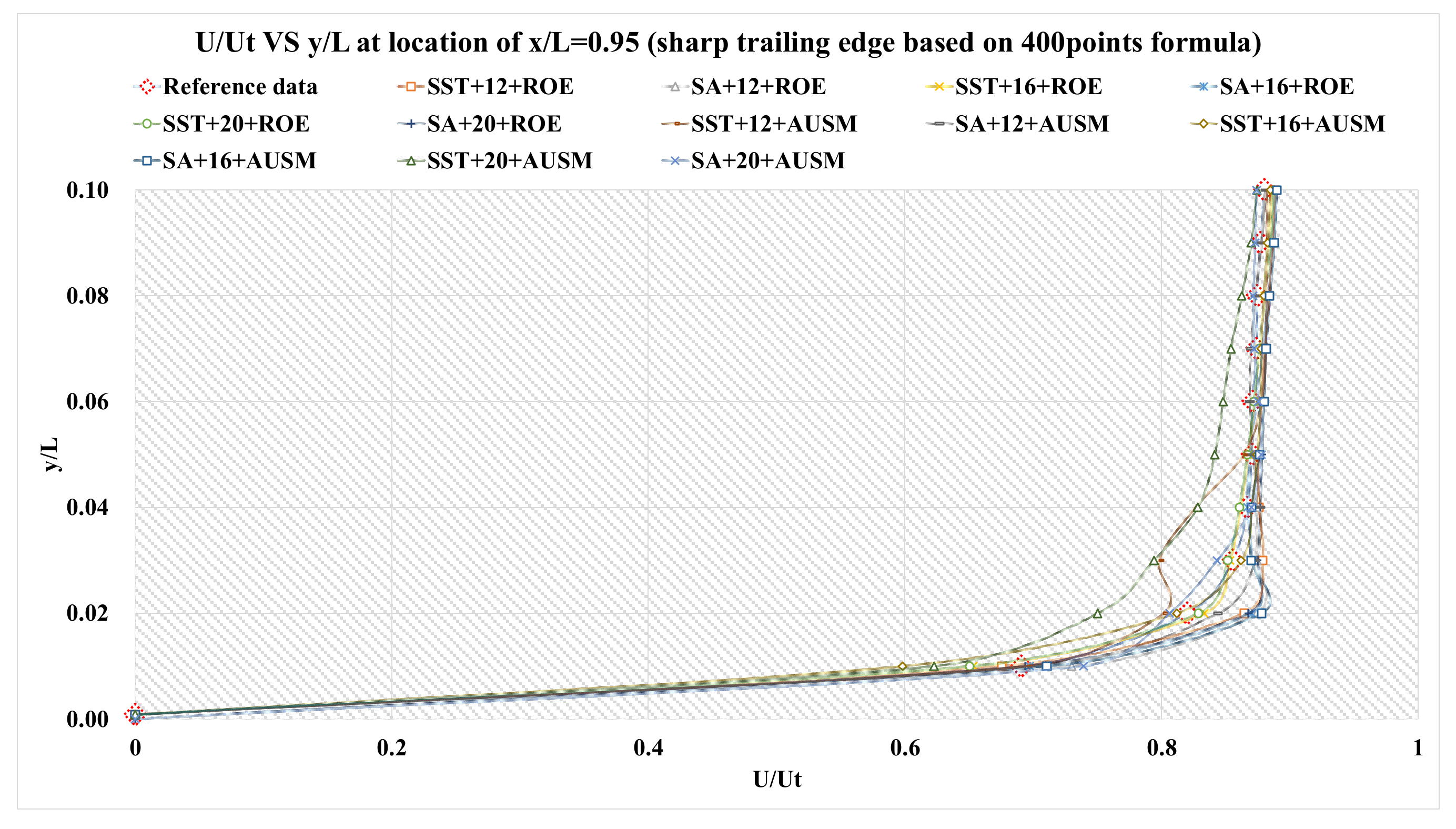

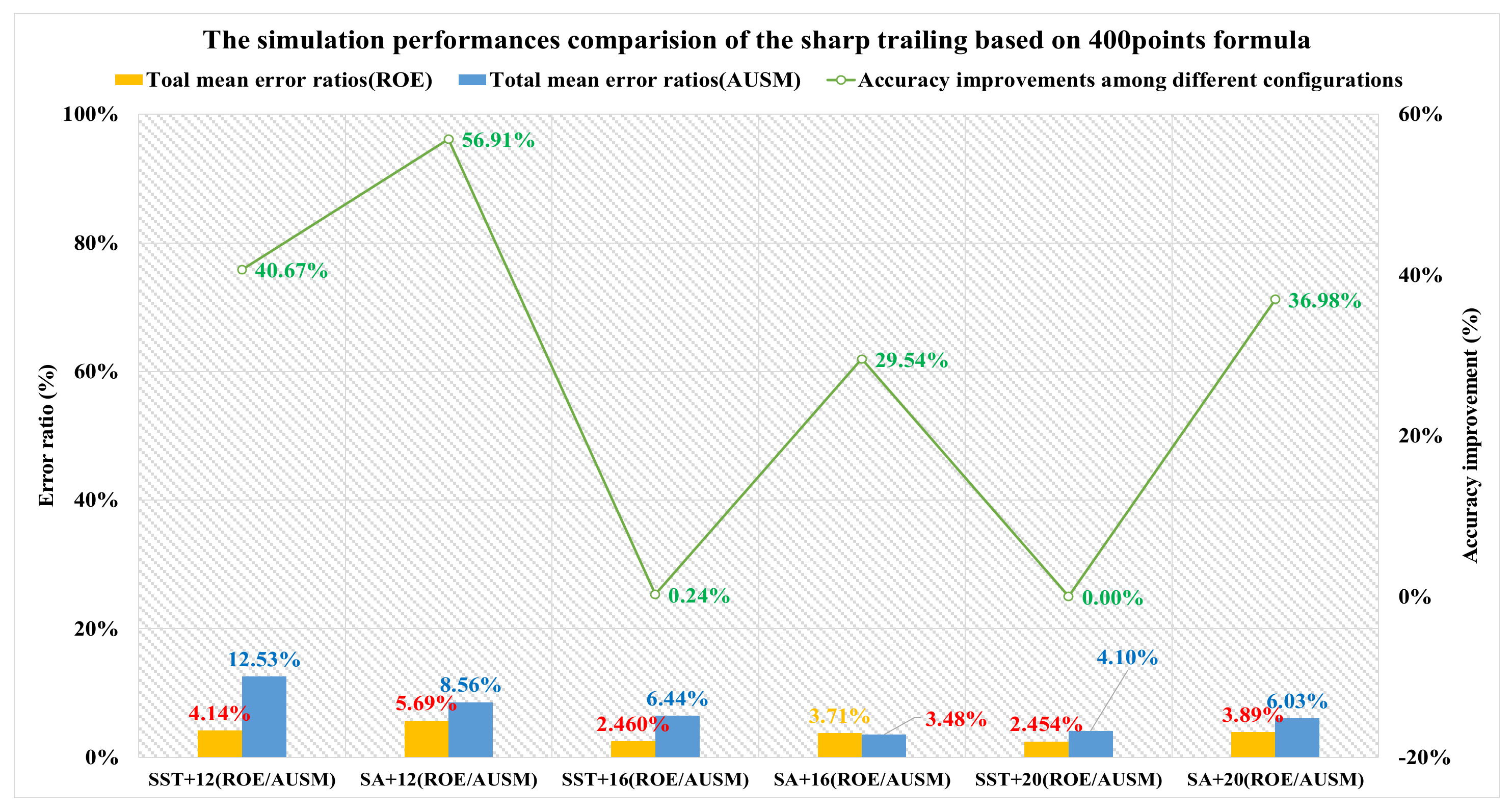

3.1.6. Results of the Sharp Trailing Edge Based on Definition Formula Applying 400 Points

| Simulation Configurations | Mean Error Ratios under Different Configurations | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ROE | AUSM | |||||

| P/Pt | T/Tt | U/Ut | P/Pt | T/Tt | U/Ut | |

| SST + 12 m | 6.02% | 4.72% | 1.66% | 13.60% | 22.17% | 1.83% |

| SA + 12 m | 8.66% | 6.36% | 2.06% | 12.65% | 12.06% | 0.95% |

| SST + 16 m | 2.21% | 4.08% | 1.09% | 7.75% | 9.69% | 1.89% |

| SA + 16 m | 6.96% | 2.86% | 1.32% | 3.66% | 4.98% | 1.81% |

| SST + 20 m | 2.06% | 4.22% | 1.08% | 6.48% | 1.71% | 4.10% |

| SA + 20 m | 7.35% | 2.74% | 1.59% | 7.52% | 9.22% | 1.35% |

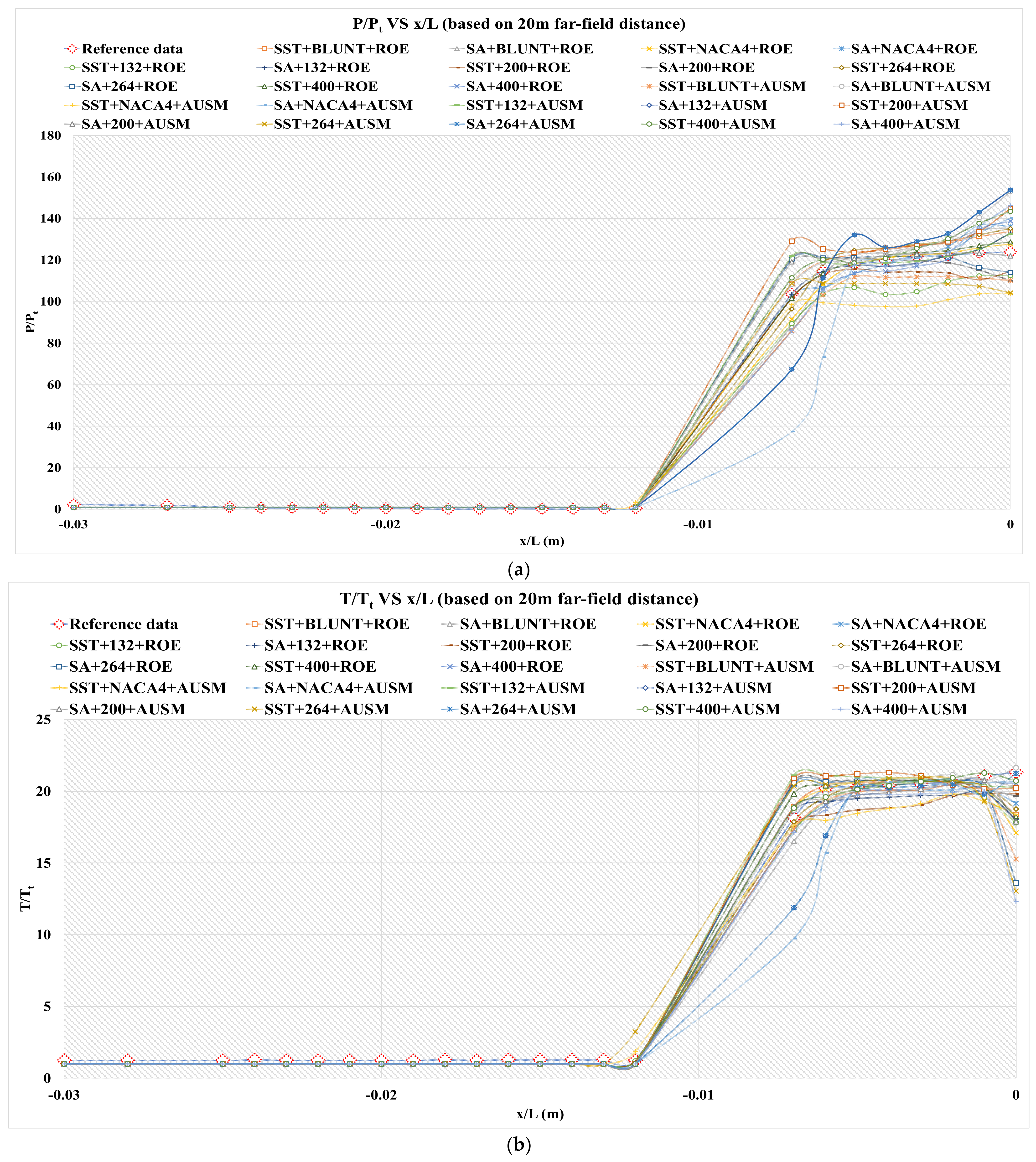

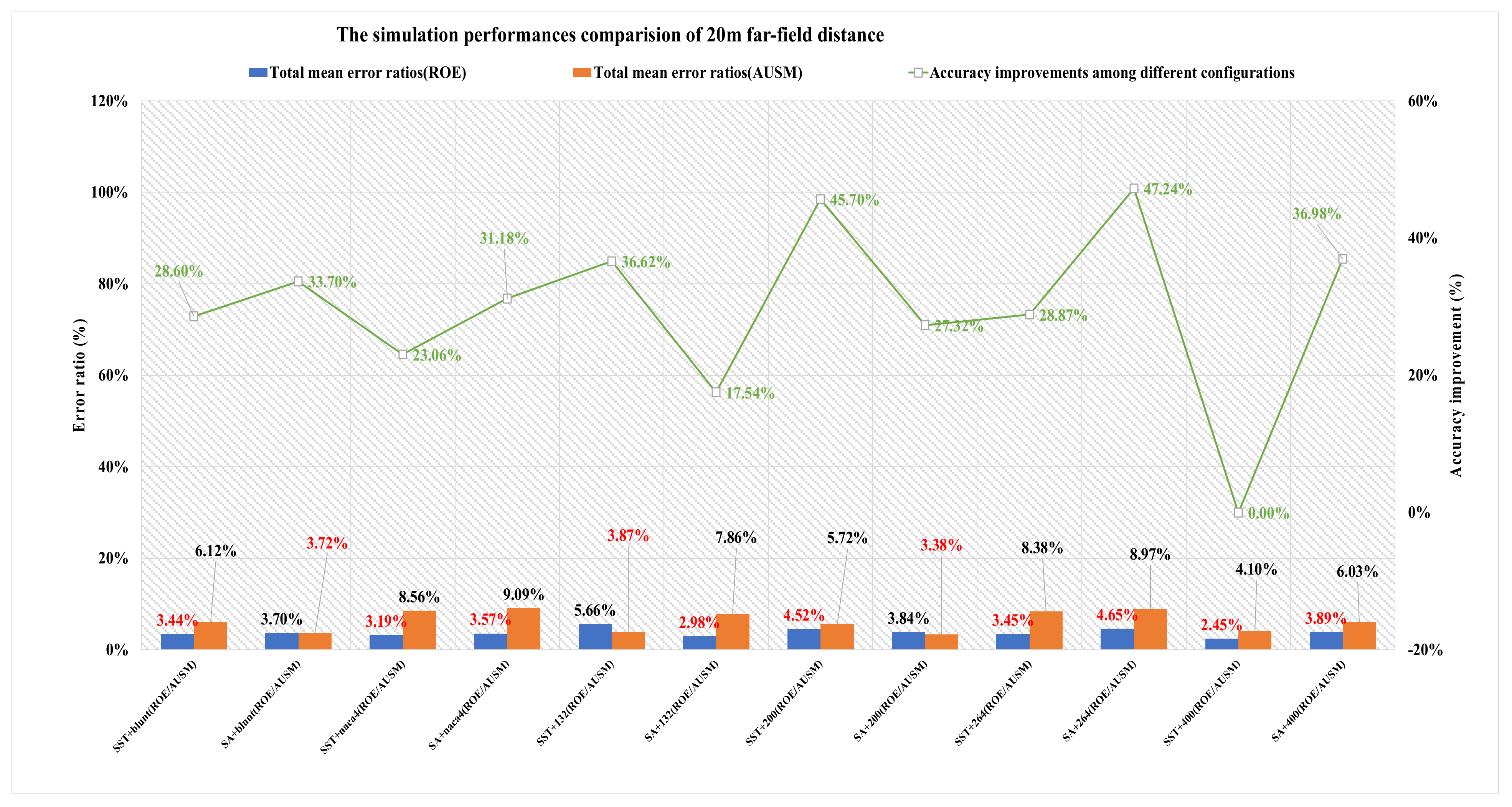

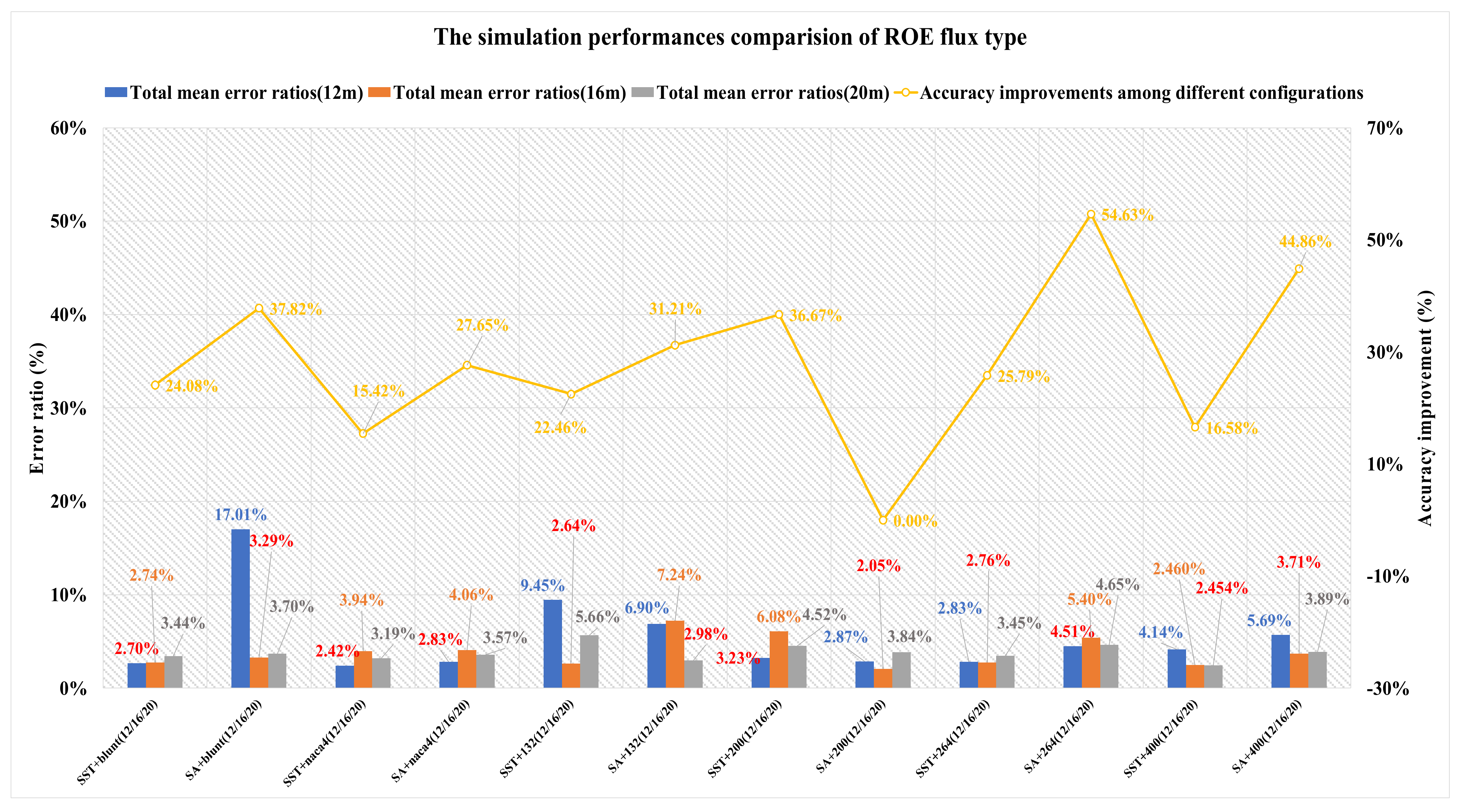

3.2. Far-Field Distance

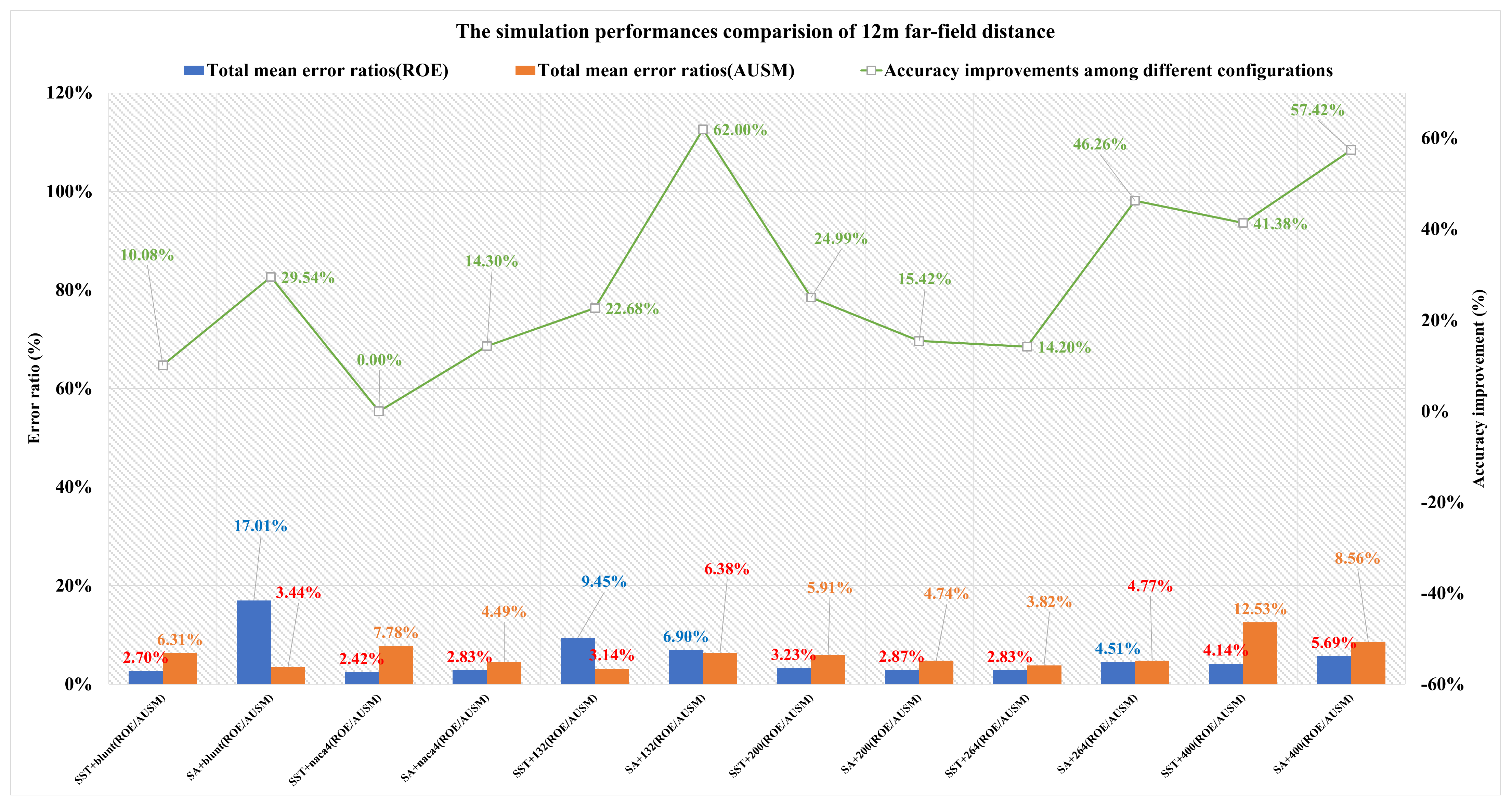

3.2.1. Results of 12 m Far-Field Distance

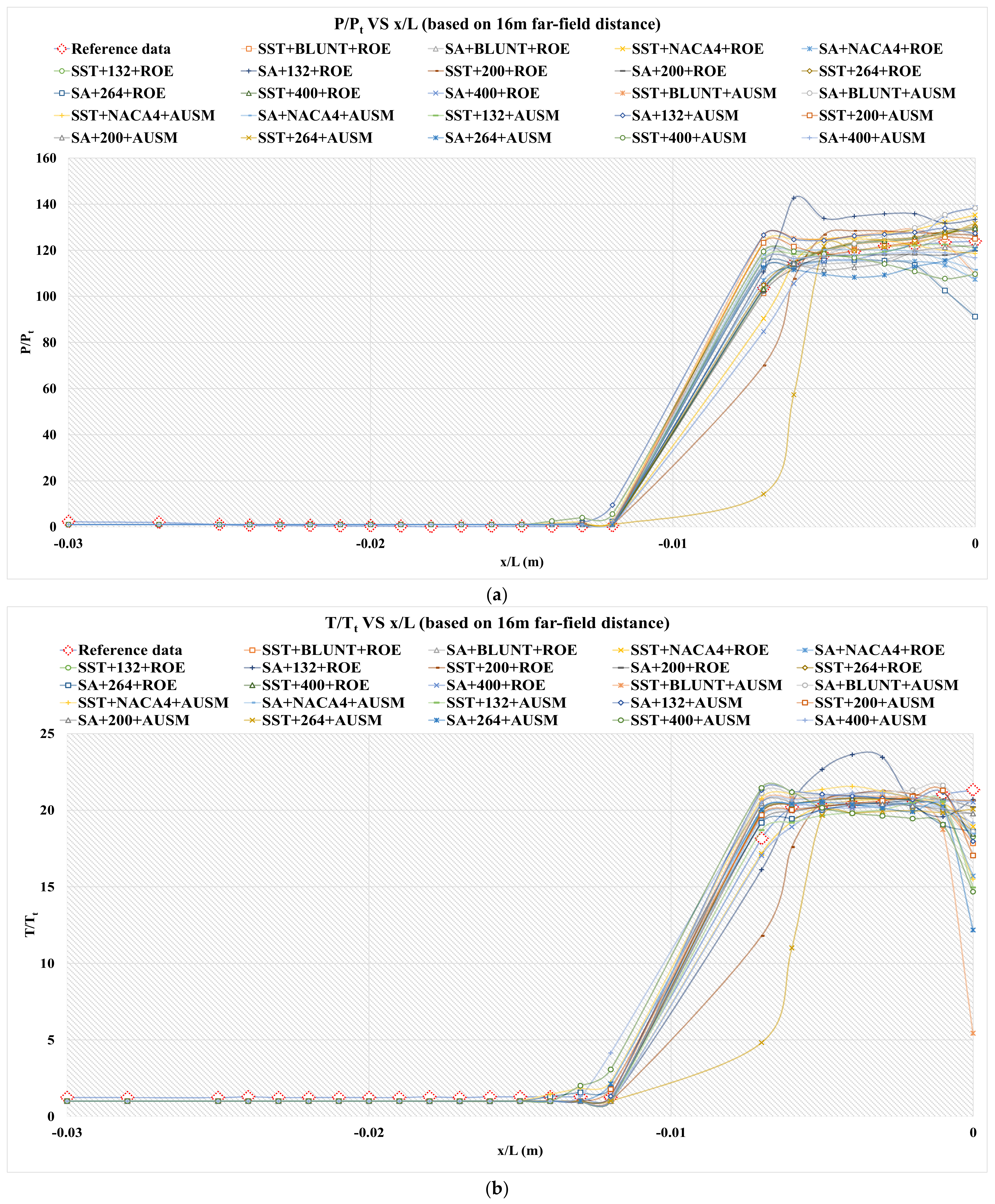

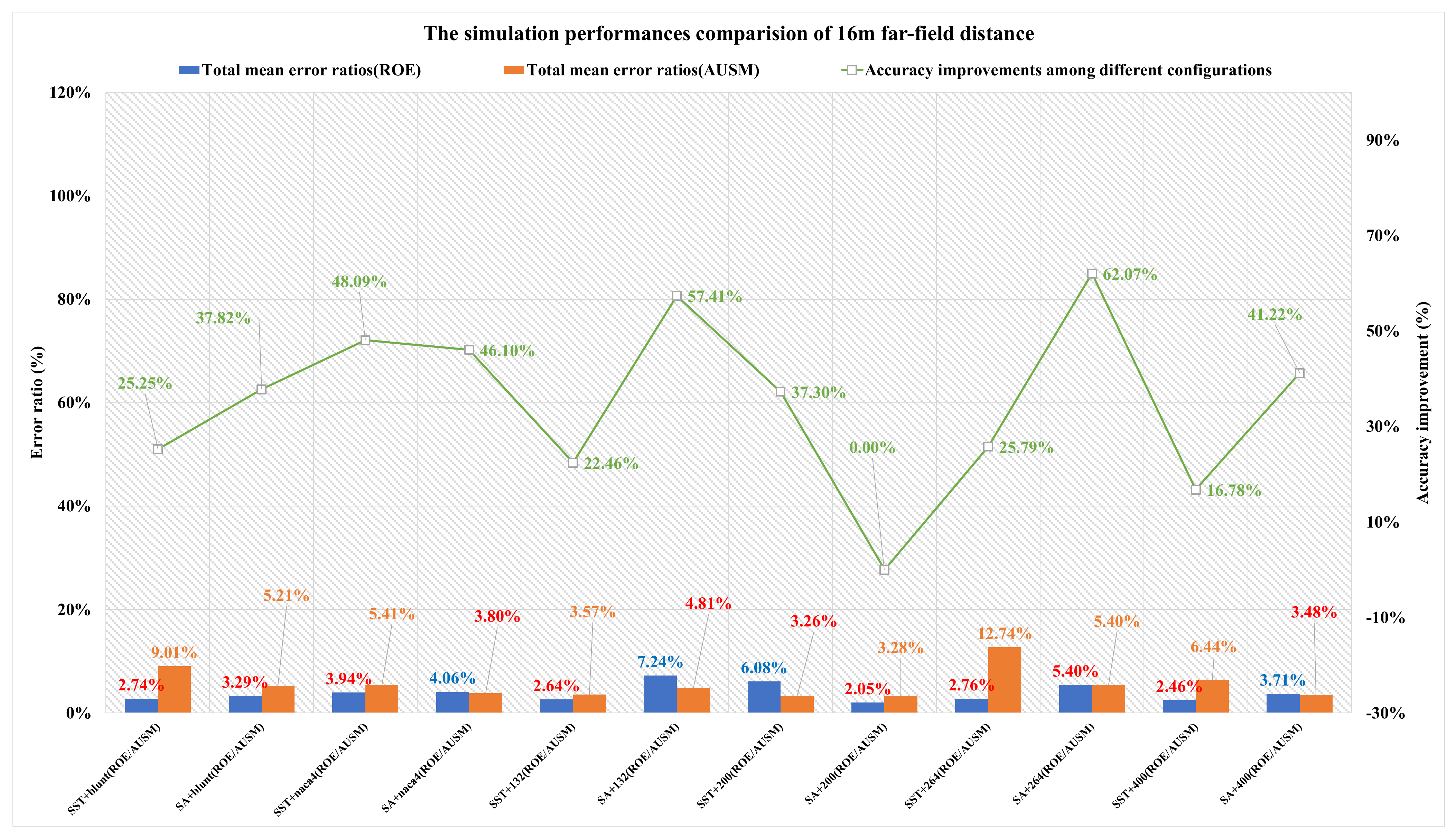

3.2.2. Results of 16 m Far-Field Distance

3.2.3. Results of 20 m Far-Field Distance

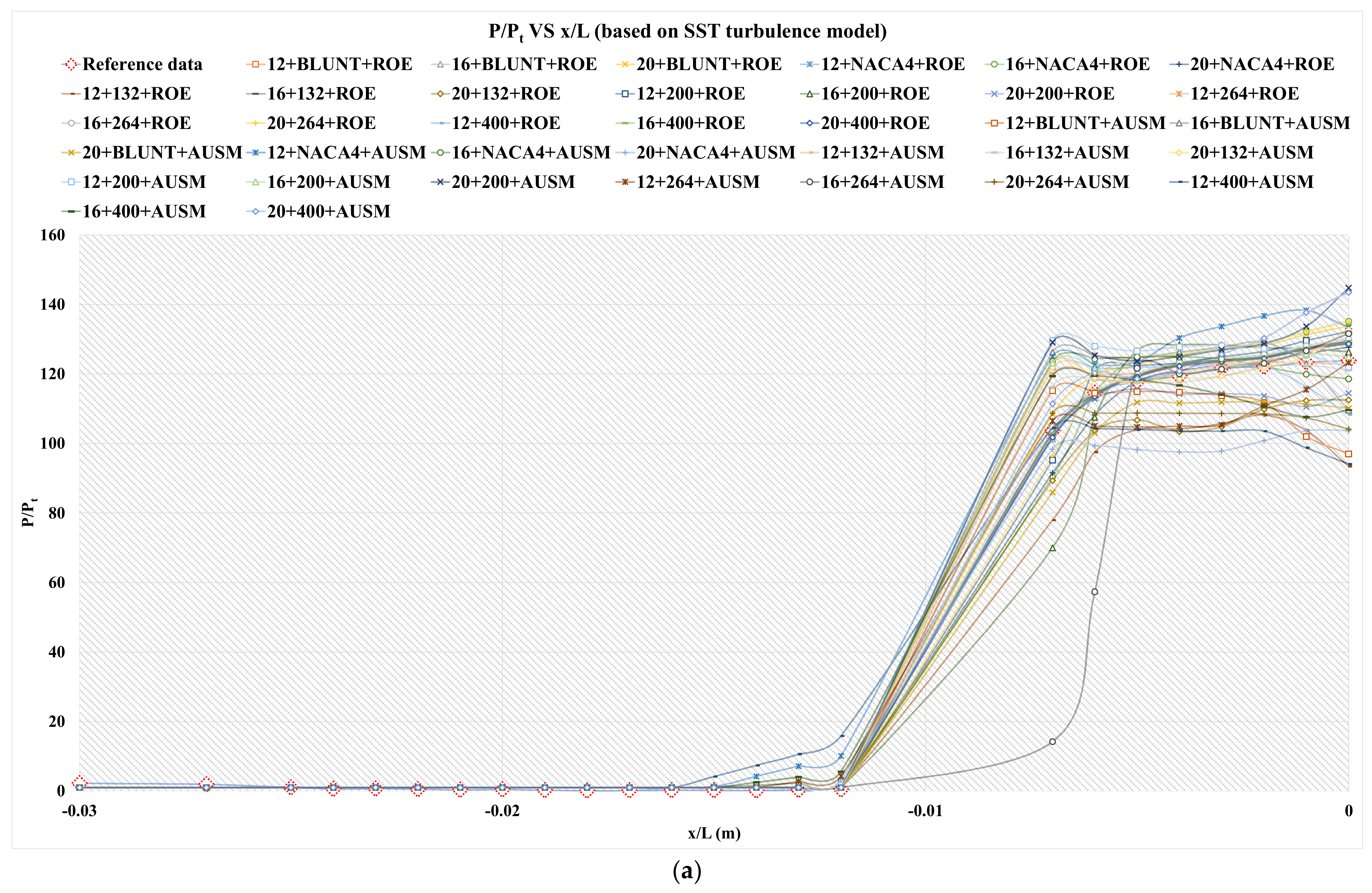

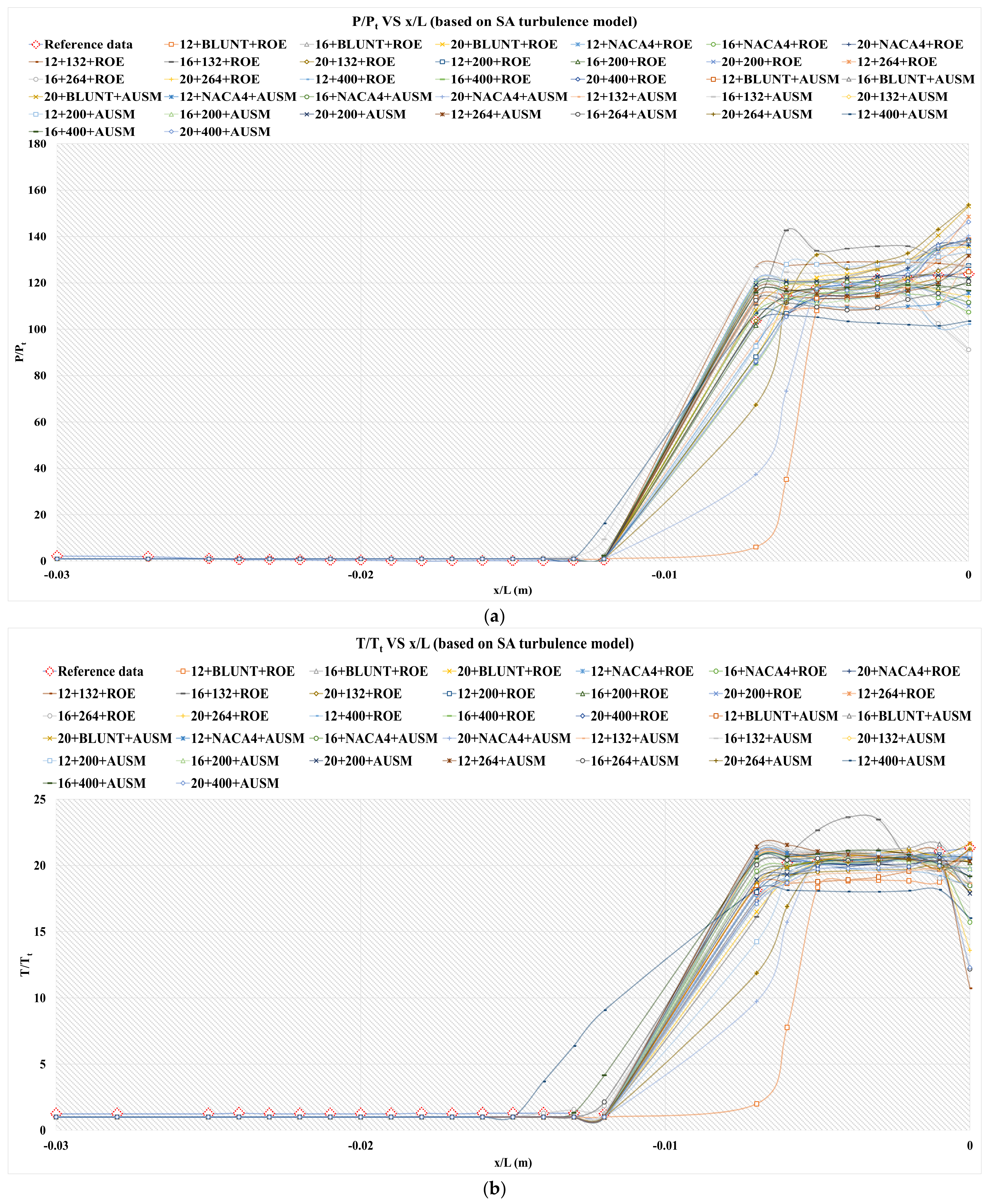

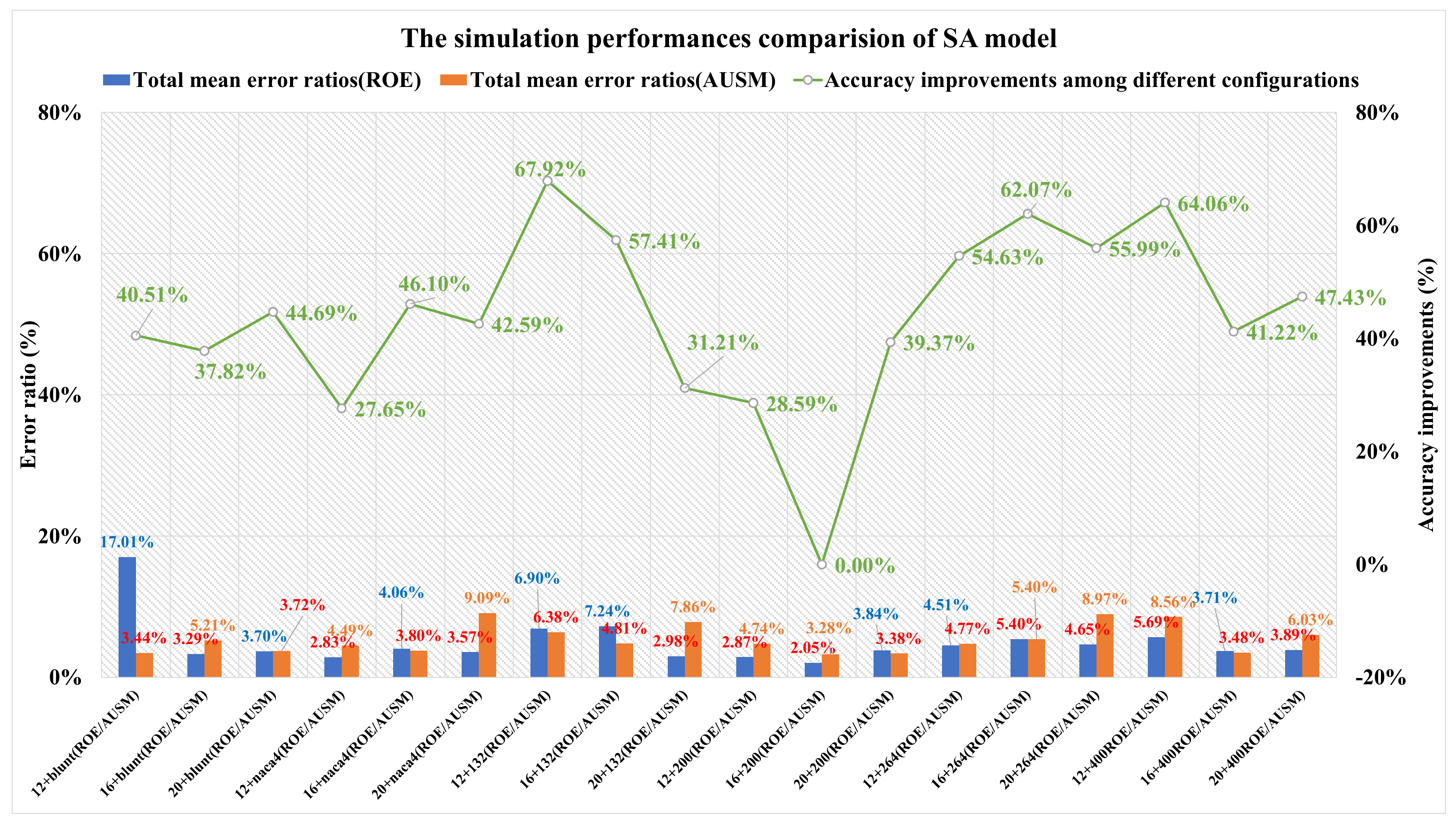

3.3. Turbulence Model

3.3.1. Results of SST k-Omega

3.3.2. Results of Spalart–Allmaras

3.4. Flux Type

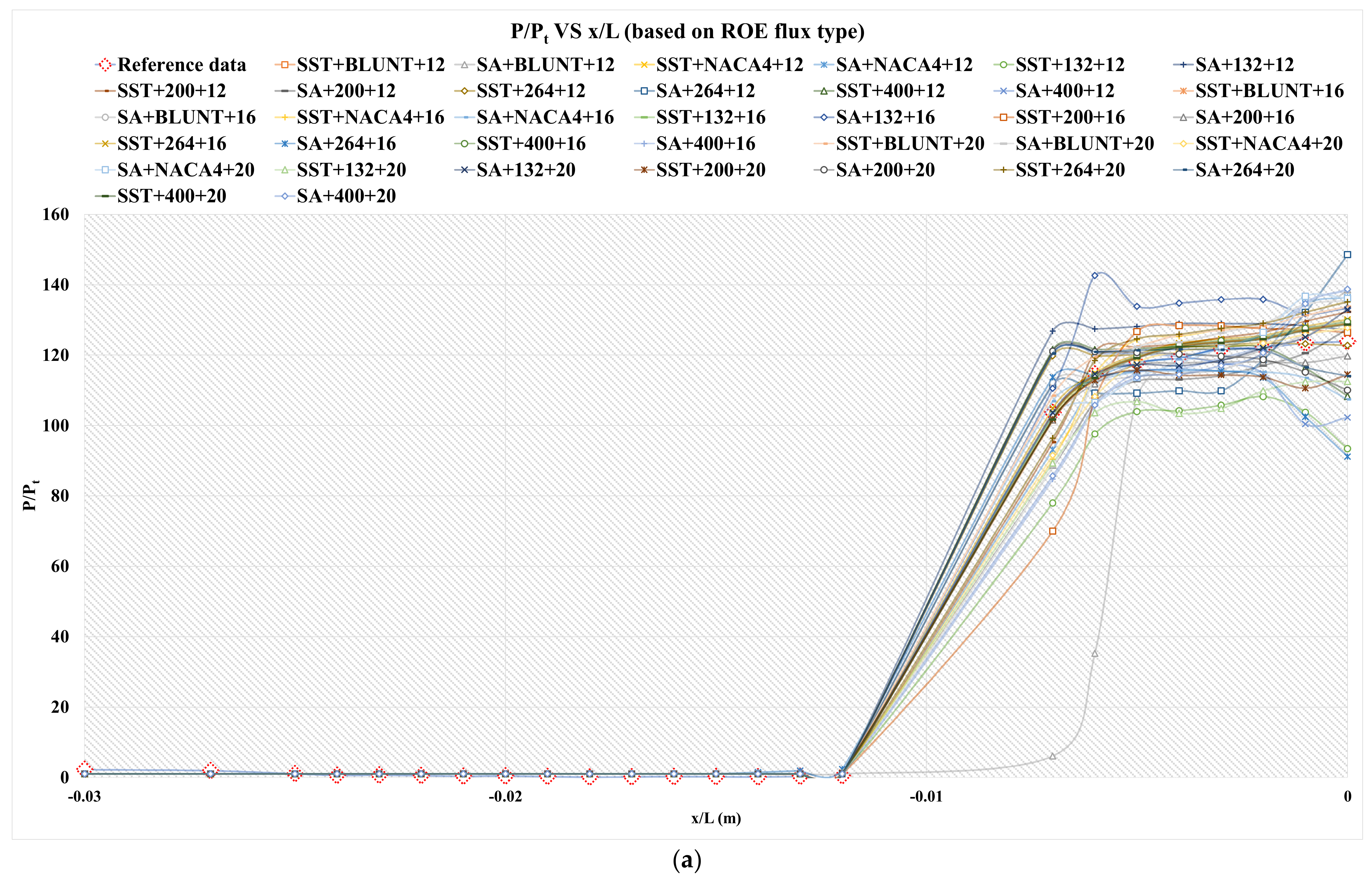

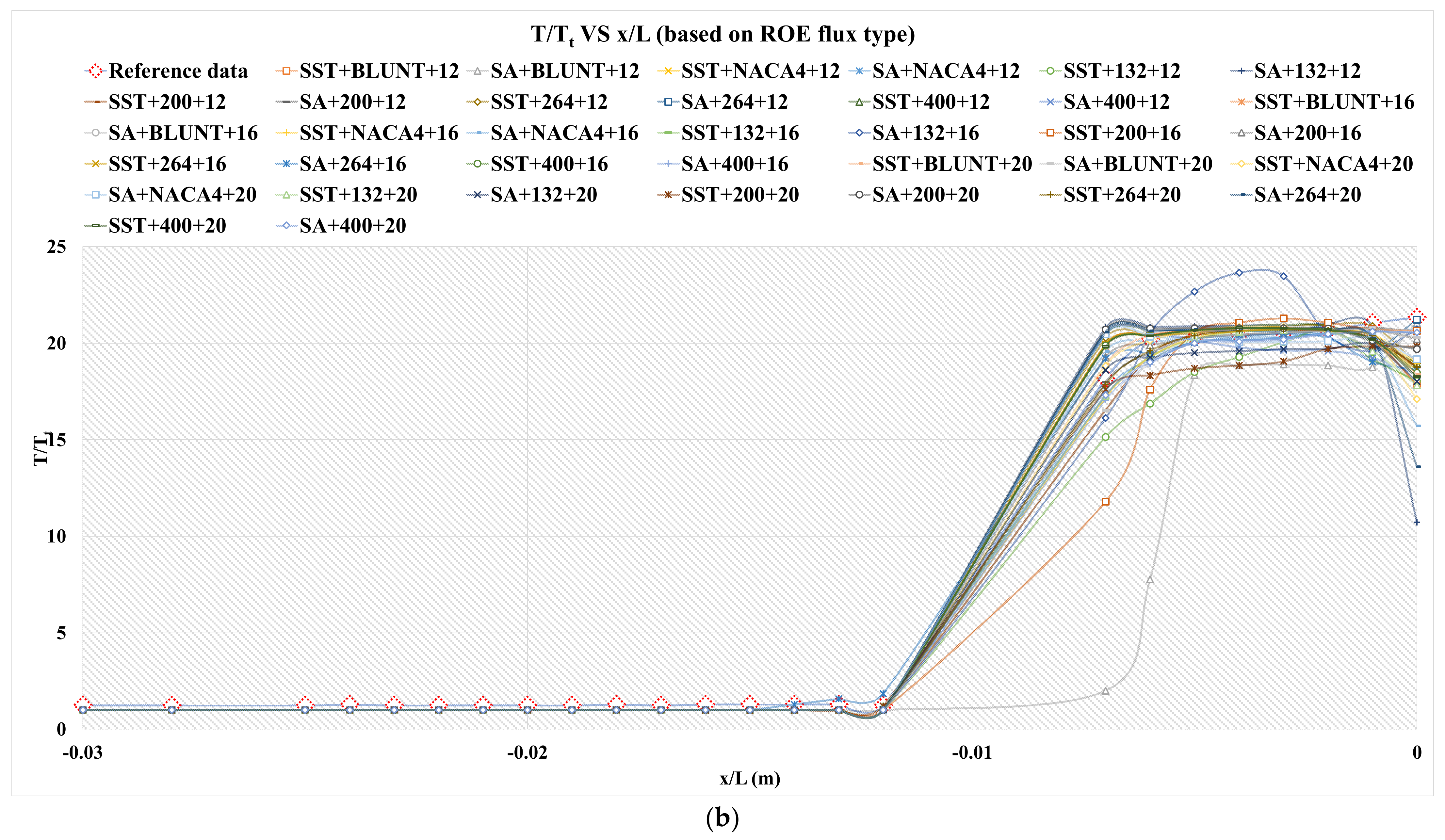

3.4.1. Results of ROE Flux Type

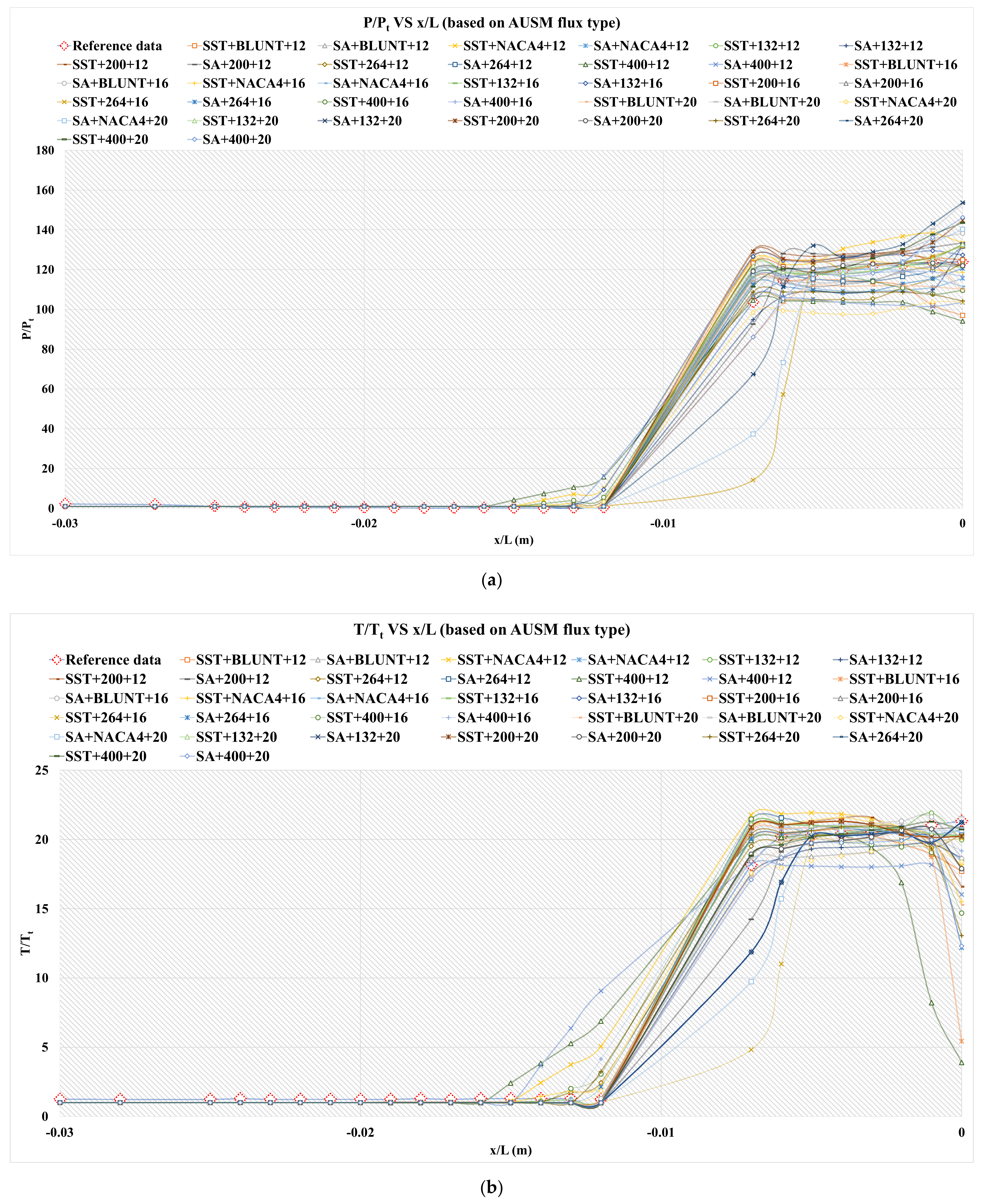

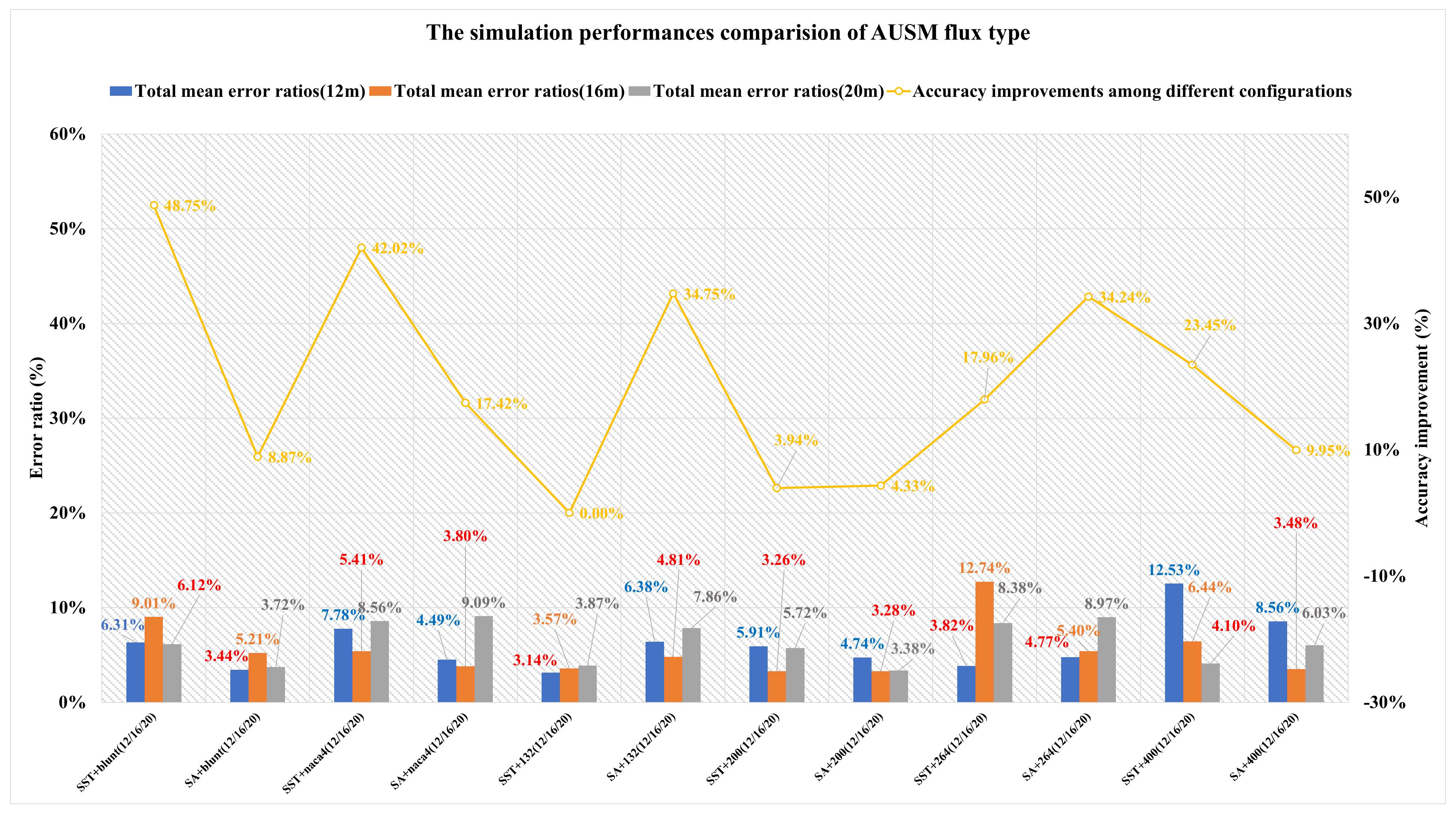

3.4.2. Results of AUSM Flux Type

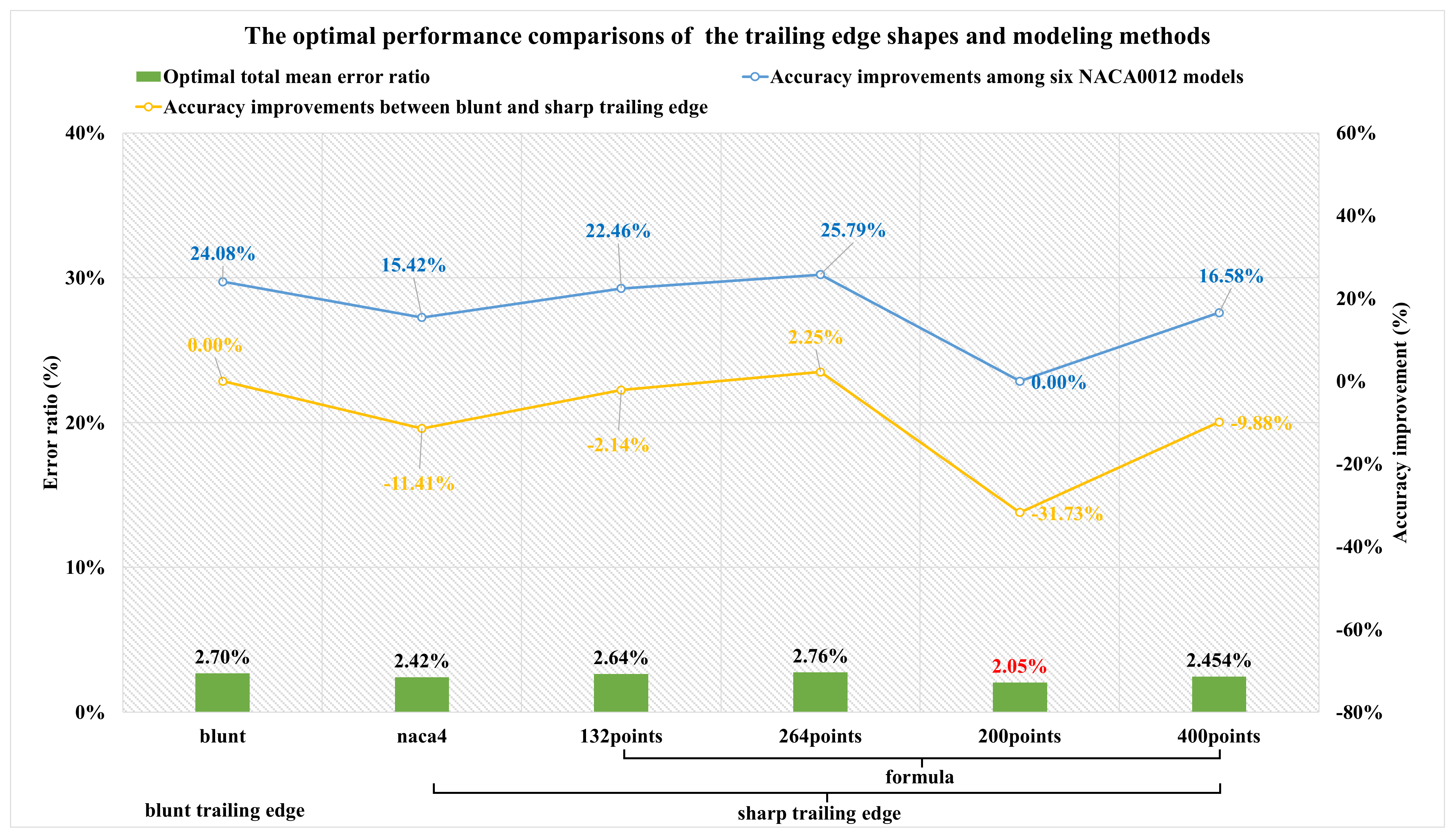

3.5. Discussion

4. Conclusions

- Unlike under incompressible external flow field, as to the trailing edge shape selection, the improper sharp trailing edge design could bring a larger error ratio than that of the blunt trailing edge shape. A similar situation exists for the modeling methods selection, in particular for the choice between the NACA4 and the definition formula. Except in a case where the definition formula adopts 200 points, NACA4 is preferred to establish the NACA0012 airfoil. Further, whether the adopted data points are from Airfoil tools or the NACA4 generator, the increase in the number of data points could not bring about an improvement in calculation accuracy. As to the far-field distance, the maximum far-field distance could not lead to the minimum simulation error ratio. Specifically, the numerical accuracy is promoted with the far-field distance increases from 12L to 16L; then that is decreased with the further from 16L to 20L and a 16L far-field distance is suggested. As to the turbulence model, the performance of SA adopting second-order upwind modified turbulent viscosity is better than that of SA adopting first-order. As for the flux type, the calculation accuracy of the ROE flux type is better than that of the AUSM flux type, and the unsuitable flux type selection could cause maximum accuracy loss.

- Despite the rise of the far-field distance, which would result in the aspect ratio addition on the condition it could be limited within a reasonable range, the simulation accuracy could be promoted as the far-field increases. The suggests that the maximum aspect ratio value is within 4800 and the minimum determinant value is above 0.82.

- In this paper, as shown in Table 25, the sharp trailing edge based on 200 points definition formula, a 16L far-field distance, SA turbulence model, and ROE flux type is the preferred simulation configuration and the optimal mean error ratios are (2.54%, 1.86%, 1.74%).

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, F.; Liu, H.; Zhang, S. Time-adaptive loosely coupled analysis on fluid–thermal–structural behaviors of hypersonic wing structures under sustained aeroheating. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2018, 78, 620–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, F.; Kong, W.; Sun, D.; Bai, J. Shock-stable flux scheme for predicting aerodynamic heating load of hypersonic airliners. Sci. China Ser. G Phys. Mech. Astron. 2019, 62, 984711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Zhang, G. Analysis of Influence of Different Parameters on Numerical Simulation of NACA0012 Incompressible External Flow Field under High Reynolds Numbers. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadikin, A.; Yunus, N.A.M.; Abd Hamid, S.A.; Ismail, A.E.; Salleh, S.; Ahmad, S.; Rahman, M.N.A.; Mahzan, S.; Ayop, S.S. A comparative study of turbulence models on aerodynamics characteristics of a NACA0012 airfoil. Int. J. Integr. Eng. 2018, 10, 134–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zheng, X.; Liu, Z.; Yang, Y.; Lei, J.-C.; Li, Z.-X. Research on Climb-cruise Global Trajectory Optimization for RBCC Hypersonic Vehicle. Missiles Space Veh. 2018, 47, 1–8. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Vassberg, J.C.; Jameson, A. In pursuit of grid convergence for two-dimensional Euler solutions. J. Aircr. 2010, 47, 1152–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Diskin, B.; Thomas, J.L.; Rumsey, C.L.; Schwoppe, A. Grid-convergence of Reynolds-averaged Navier-stokes solutions for benchmark flows in two dimensions. AIAA J. 2016, 54, 2563–2588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, P.B.; Paulson, V.; Madhanraj, V.; Shah, D.A. Heat transfer and temperature effects on a dimpled NACA0012 airfoil with various angles of attack. Int. J. Ambient Energy 2018, 39, 783–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, P.B.; Shah, D.A. Effect of square dimples on the temperature distribution and heat transfer coefficient of an NACA0012 airfoil. Int. J. Ambient Energy 2019, 40, 754–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, D.R.; Devi, P.B.; Gopalsamy, M. Investigation on effect of square dimples on NACA0012 airfoil with various Reynolds numbers. Int. J. Ambient Energy 2021, 42, 397–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekka, N.; Bessaih, R.; Sellam, M.; Chpoun, A. Numerical study of heat transfer around the small scale airfoil using various turbulence models. Numer. Heat Transf. Part A Appl. 2009, 56, 946–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinz, D.F.; Alighanbari, H.; Breitsamter, C. Influence of heat transfer on the aerodynamic performance of a plunging and pitching NACA0012 airfoil at low Reynolds numbers. J. Fluids Struct. 2013, 37, 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Lai, Y.; Wang, L.; Wu, H.; Li, L. Study on the icing characteristics of typical wind turbine. J. Hebei Univ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 40, 9–14. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.K. Numerical simulation of Aeroacoustic Noise at Low Mach Number Flows by Using the Finite Difference Lattice Boltzmann Method. J. Adv. Mar. Eng. Technol. 2004, 28, 717–727. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, H.K.; Lee, Y.H.; Tsutahara, M.; Shikata, K.; Kim, E.R.; Kim, Y.T. Computation OF Aerodynamic Sounds AT Low Mach Numbers Using Finite Difference Lattice Boltzmann Method. Korean Soc. Comput. Fluids Eng. 2005, 10, 8–15. [Google Scholar]

- Rattanasiri, P.; Perrin, R. Influence of the Wavelength of Cut-In Sinusoidal Trailing Edge Shape to the Aerodynamics Characteristic of the Airfoil. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 886, 012020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrin, R.; Rattanasiri, P.; Lamballais, E.; Yooyen, S. Influence of the trailing edge shape on the aerodynamic characteristics of an airfoil at low Re number using RANS. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 886, 012021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.P. Evaluation of Jameson-Schmidt-Turkel dissipation scheme for hypersonic flow computations. J. Aircraft. 1996, 33, 286–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delery, J.; Coet, M.C. Experiments on Shock-Wave/Boundary-Layer Interactions Produced by Two-Dimensional Ramps and Three-Dimensional Obstacles. In Hypersonic Flows for Reentry Problems Désidéri; Glowinski, J.A., Périaux, R.J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Kussoy, M.I.; Horstman, C.C. Documentation of Two- and Three-Dimensional Hypersonic Shock Wave/Turbulent Boundary Layer Interaction Flows. In NASA Technical Memorandum 101075; NASA Ames Research Center: Moffett Field, CA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.; Zhang, G. An Effective Simulation Scheme for Predicting the Aerodynamic Heat of a Scramjet-Propelled Vehicle. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 9344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICEM. CFD Hexa 2D Airfoil Meshing. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EknKVAJGEJ8&t=58s (accessed on 9 May 2022).

- Ansys, Inc. Ansys Fluent Theory Guide; Ansys, Inc.: Canonsburg, PA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Schlichting, H.; Gersten, K. Boundary-Layer Theory, 7th ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1979; ISBN 0070553343. [Google Scholar]

- Smirnov, N.N.; Penyazkov, O.G.; Sevrouk, K.L.; Nikitin, V.F.; Stamov, L.I.; Tyurenkova, V.V. Detonation onset following shock wave focusing. Acta Astronaut. 2017, 135, 114–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Launder, B.E.; Spalding, D.B. The Numerical Computation of Turbulent Flow. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 1974, 3, 269–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menter, F.R. Two-equation eddy-viscosity turbulence models for engineering applications. AIAA J. 1994, 32, 1598–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Spalart, P.; Allmaras, S. A one-equation turbulence model for aerodynamic flows. In Proceedings of the 30th Aerospace Sciences Meeting and Exhibit, Reno, NV, USA, 6–9 January 1992; p. 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, J.M.; Smith, W.A. Preconditioning applied to variable and constant density flows. AIAA J. 1995, 33, 2050–2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roe, P.L. Characteristic-based schemes for the Euler equations. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 1986, 18, 337–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liou, M.S. A sequel to ausm: Ausm+. J. Comput. Phys. 1996, 129, 364–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yan, C.; Ke, L.; Zhang, S. Research on scheme effect of computational fluid dynamics in aerothermal. J. Beijing Univ. Aeronaut. Astronaut. 2003, 11, 1022–1025. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansys, Inc. Ansys Fluent User’s Guide; Ansys, Inc.: Canonsburg, PA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox, D.C. Turbulence Modeling for CFD; DCW Industries, Inc.: La Canada, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Barth, T.; Jespersen, D. The design and application of upwind schemes on unstructured meshes. In Proceedings of the 27th Aerospace Sciences Meeting, Reno, NV, USA, 9–12 January 1989; p. 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mesh (Cells) | x/L (m) (P/Pt, T/Tt and Error Ratios) | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −0.007 | −0.006 | −0.005 | −0.004 | −0.003 | −0.002 | −0.001 | 0 | |||||||||

| 103.63 | 18.15 | 114.55 | 20.19 | 117.87 | 20.28 | 119.40 | 20.43 | 121.74 | 20.52 | 122.10 | 20.66 | 123.39 | 21.04 | 123.83 | 21.33 | |

| 418,000 | 86.04 | 14.35 | 124.12 | 20.75 | 126.77 | 20.91 | 129.01 | 20.98 | 130.89 | 20.03 | 133.31 | 19.86 | 135.94 | 19.67 | 140.97 | 18.45 |

| 16.97% | 20.95% | 8.35% | 2.77% | 7.55% | 3.09% | 8.05% | 2.71% | 7.51% | 2.39% | 9.18% | 3.89% | 10.17% | 6.52% | 13.84% | 13.49% | |

| 588,000 | 102.66 | 19.86 | 113.79 | 20.36 | 119.55 | 20.64 | 122.78 | 20.77 | 124.02 | 20.76 | 125.06 | 20.69 | 127.61 | 20.22 | 129.58 | 18.60 |

| 0.93% | 9.41% | 0.67% | 0.85% | 1.43% | 1.76% | 2.83% | 1.69% | 1.87% | 1.17% | 2.42% | 0.14% | 3.42% | 3.91% | 4.64% | 12.76% | |

| 828,000 | 86.46 | 14.67 | 123.44 | 20.27 | 126.56 | 20.40 | 128.30 | 20.53 | 130.73 | 20.65 | 132.99 | 20.72 | 135.59 | 20.62 | 140.80 | 19.16 |

| 16.57% | 19.16% | 7.76% | 0.39% | 7.38% | 0.59% | 7.45% | 0.49% | 7.38% | 0.63% | 8.91% | 0.26% | 9.88% | 2.01% | 13.70% | 10.18% | |

| Mesh (Cells) | x/L (m) (P/Pt, T/Tt and Error Ratios) | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −0.007 | −0.006 | −0.005 | −0.004 | −0.003 | −0.002 | −0.001 | 0 | |||||||||

| 103.63 | 18.15 | 114.55 | 20.19 | 117.87 | 20.28 | 119.40 | 20.43 | 121.74 | 20.52 | 122.10 | 20.66 | 123.39 | 21.04 | 123.83 | 21.33 | |

| 418,000 | 89.78 | 14.77 | 126.25 | 21.28 | 127.33 | 20.75 | 128.96 | 20.67 | 131.02 | 20.83 | 133.96 | 20.91 | 135.24 | 20.03 | 140.09 | 18.51 |

| 13.36% | 18.63% | 10.21% | 5.40% | 8.03% | 2.30% | 8.01% | 1.19% | 7.62% | 1.51% | 9.71% | 1.19% | 9.60% | 4.81% | 13.13% | 13.21% | |

| 588,000 | 90.39 | 17.18 | 114.58 | 19.26 | 124.38 | 20.27 | 125.35 | 20.61 | 127.31 | 20.70 | 128.97 | 20.70 | 132.19 | 20.45 | 135.21 | 18.93 |

| 12.77% | 5.35% | 0.02% | 4.58% | 5.53% | 0.06% | 4.99% | 0.89% | 4.57% | 0.89% | 5.63% | 0.15% | 7.13% | 2.80% | 9.19% | 11.24% | |

| 828,000 | 90.57 | 14.90 | 125.90 | 20.44 | 126.45 | 20.44 | 128.39 | 20.57 | 130.53 | 20.69 | 132.47 | 20.69 | 134.90 | 20.57 | 139.35 | 18.97 |

| 12.60% | 17.91% | 9.91% | 1.26% | 7.28% | 0.78% | 7.53% | 0.69% | 7.22% | 0.82% | 8.49% | 0.13% | 9.32% | 2.26% | 12.53% | 11.07% | |

| Mesh (Cells) | x/L (m) (P/Pt, T/Tt and Error Ratios) | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −0.007 | −0.006 | −0.005 | −0.004 | −0.003 | −0.002 | −0.001 | 0 | |||||||||

| 103.63 | 18.15 | 114.55 | 20.19 | 117.87 | 20.28 | 119.40 | 20.43 | 121.74 | 20.52 | 122.10 | 20.66 | 123.39 | 21.04 | 123.83 | 21.33 | |

| 418,000 | 80.46 | 14.88 | 108.04 | 20.47 | 121.67 | 20.93 | 123.84 | 21.02 | 126.03 | 21.05 | 127.14 | 20.89 | 129.25 | 20.07 | 132.35 | 16.86 |

| 22.36% | 18.03% | 5.68% | 1.39% | 3.23% | 3.18% | 3.72% | 2.90% | 3.52% | 2.58% | 4.12% | 1.09% | 4.75% | 4.62% | 6.88% | 20.95% | |

| 588,000 | 91.52 | 18.83 | 108.25 | 20.12 | 117.87 | 20.65 | 120.98 | 20.83 | 122.30 | 20.83 | 123.39 | 20.61 | 125.88 | 20.26 | 127.74 | 17.11 |

| 11.69% | 3.76% | 5.50% | 0.34% | 0.00% | 1.79% | 1.32% | 1.99% | 0.46% | 1.52% | 1.05% | 0.26% | 2.01% | 3.71% | 3.15% | 19.78% | |

| 828,000 | 80.37 | 15.02 | 114.19 | 20.30 | 120.59 | 20.62 | 123.00 | 20.73 | 125.09 | 20.75 | 126.76 | 20.67 | 128.71 | 20.41 | 131.48 | 17.51 |

| 22.44% | 17.24% | 0.31% | 0.57% | 2.31% | 1.67% | 3.02% | 1.49% | 2.75% | 1.12% | 3.81% | 0.02% | 4.31% | 3.04% | 6.17% | 17.88% | |

| Mesh (Cells) | x/L (m) (Cp, Entropy and Error Ratios) | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.7 | |||||||||

| 1.8378 | 10.15 | 0.168 | 10.15 | 0.0871 | 10.15 | 0.055 | 10.15 | 0.0369 | 10.15 | 0.0248 | 10.15 | 0.0163 | 10.15 | 0.0121 | 10.15 | |

| 418,000 | 1.8102 | 10.6753 | 0.1662 | 10.6076 | 0.0837 | 10.6431 | 0.0604 | 10.6786 | 0.0388 | 10.6632 | 0.0294 | 10.6742 | 0.0209 | 10.5563 | 0.0159 | 10.5885 |

| 1.51% | 5.18% | 1.10% | 4.51% | 3.9% | 4.86% | 9.88% | 5.21% | 5.09% | 5.06% | 18.42% | 5.16% | 28.38% | 4.00% | 31.03% | 4.32% | |

| 588,000 | 1.8411 | 10.6302 | 0.168 | 10.5612 | 0.0843 | 10.5504 | 0.0552 | 10.5615 | 0.0378 | 10.5637 | 0.0281 | 10.4773 | 0.0199 | 10.4811 | 0.0151 | 10.5035 |

| 0.17% | 4.73% | 0.03% | 4.05% | 3.29% | 3.94% | 0.25% | 4.05% | 2.45% | 4.08% | 13.04% | 3.23% | 22.49% | 3.26% | 24.74% | 3.48% | |

| 828,000 | 1.8178 | 10.6543 | 0.1679 | 10.5722 | 0.088 | 10.5842 | 0.0596 | 10.6036 | 0.0386 | 10.6012 | 0.0291 | 10.6474 | 0.0207 | 10.5471 | 0.0158 | 10.5645 |

| 1.09% | 4.97% | 0.09% | 4.16% | 0.99% | 4.28% | 8.42% | 4.47% | 4.38% | 4.45% | 17.2% | 4.9% | 27.16% | 3.91% | 30.28% | 4.08% | |

| Mesh (Cells) | x/L (m) (Cp, Entropy and Error Ratios) | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.7 | |||||||||

| 1.8378 | 10.15 | 0.168 | 10.15 | 0.0871 | 10.15 | 0.055 | 10.15 | 0.0369 | 10.15 | 0.0248 | 10.15 | 0.0163 | 10.15 | 0.0121 | 10.15 | |

| 418,000 | 1.9731 | 10.6615 | 0.1563 | 10.5732 | 0.0801 | 10.5754 | 0.0573 | 10.5825 | 0.0341 | 10.5817 | 0.028 | 10.5884 | 0.0198 | 10.5071 | 0.0153 | 10.5385 |

| 7.36% | 5.04% | 6.99% | 4.17% | 8.07% | 4.19% | 4.16% | 4.26% | 7.67% | 4.25% | 12.62% | 4.32% | 21.66% | 3.52% | 26.70% | 3.83% | |

| 588,000 | 1.9624 | 10.5037 | 0.1574 | 10.4682 | 0.0807 | 10.465 | 0.0536 | 10.4675 | 0.0345 | 10.4707 | 0.0253 | 10.4624 | 0.0174 | 10.4611 | 0.0127 | 10.4525 |

| 6.78% | 3.48% | 6.33% | 3.13% | 7.40% | 3.1% | 2.59% | 3.13% | 6.71% | 3.16% | 1.96% | 3.08% | 7.12% | 3.07% | 5.13% | 2.98% | |

| 828,000 | 1.922 | 10.6047 | 0.1674 | 10.5682 | 0.0857 | 10.573 | 0.0563 | 10.5615 | 0.0379 | 10.5767 | 0.0279 | 10.5814 | 0.0197 | 10.5011 | 0.0152 | 10.5335 |

| 4.58% | 4.48% | 0.37% | 4.12% | 1.65% | 4.17% | 2.34% | 4.05% | 2.50% | 4.2% | 12.22% | 4.25% | 21.05% | 3.46% | 25.62% | 3.78% | |

| Mesh (Cells) | x/L (m) (Cp, Entropy and Error Ratios) | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.7 | |||||||||

| 1.8378 | 10.15 | 0.168 | 10.15 | 0.0871 | 10.15 | 0.055 | 10.15 | 0.0369 | 10.15 | 0.0248 | 10.15 | 0.0163 | 10.15 | 0.0121 | 10.15 | |

| 418,000 | 1.8013 | 10.6803 | 0.1695 | 10.6196 | 0.089 | 10.6522 | 0.0598 | 10.6816 | 0.0395 | 10.6702 | 0.0297 | 10.6764 | 0.0207 | 10.5693 | 0.0158 | 10.5975 |

| 1.99% | 5.22% | 0.84% | 4.63% | 2.18% | 4.95% | 8.76% | 5.24% | 6.95% | 5.13% | 19.79% | 5.19% | 27.09% | 4.13% | 30.72% | 4.41% | |

| 588,000 | 1.8154 | 10.6602 | 0.1675 | 10.5702 | 0.0864 | 10.5614 | 0.0579 | 10.5785 | 0.0374 | 10.5767 | 0.0279 | 10.5873 | 0.02 | 10.5011 | 0.0153 | 10.5355 |

| 1.22% | 5.03% | 0.34% | 4.14% | 0.87% | 4.05% | 5.32% | 4.22% | 1.20% | 4.2% | 12.35% | 4.31% | 23.04% | 3.46% | 26.53% | 3.8% | |

| 828,000 | 1.8394 | 10.6673 | 0.1689 | 10.5882 | 0.0885 | 10.5922 | 0.0595 | 10.6166 | 0.0392 | 10.6182 | 0.0295 | 10.6534 | 0.0206 | 10.5501 | 0.0158 | 10.5765 |

| 0.09% | 5.1% | 0.49% | 4.32% | 1.61% | 4.36% | 8.21% | 4.6% | 6.14% | 4.61% | 18.66% | 4.96% | 26.67% | 3.94% | 30.22% | 4.2% | |

| x/L (m) | Reference Data | Far-Field Distances | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of Upwind Order | |||||||

| P/Pt | Numerical Results Of P/Pt, T/Tt and Error Ratios | ||||||

| T/Tt | 12 m | 16 m | 20 m | ||||

| First-Order | Second-Order | First-Order | Second-Order | First-Order | Second-Order | ||

| −0.007 | 103.63 | 81.68 | 93.15 | 63.99 | 106.92 | 107.09 | 102.75 |

| 21.18% | 10.11% | 38.25% | 3.18% | 3.34% | 0.85% | ||

| 18.15 | 15.34 | 17.55 | 12.08 | 19.57 | 19.59 | 20.47 | |

| 15.51% | 3.29% | 33.47% | 7.81% | 7.95% | 12.78% | ||

| −0.006 | 114.55 | 106.49 | 112.16 | 101.22 | 112.50 | 106.96 | 106.52 |

| 7.04% | 2.09% | 11.64% | 1.79% | 6.63% | 7.01% | ||

| 20.19 | 18.71 | 19.13 | 17.15 | 20.03 | 19.92 | 20.33 | |

| 7.31% | 5.24% | 15.03% | 0.79% | 1.32% | 0.68% | ||

| −0.005 | 117.87 | 114.80 | 117.71 | 118.76 | 115.21 | 105.16 | 113.59 |

| 2.60% | 0.13% | 0.76% | 2.26% | 10.78% | 3.63% | ||

| 20.28 | 20.36 | 20.06 | 20.02 | 20.26% | 19.86 | 20.20 | |

| 0.36% | 1.10% | 1.28% | 0.09% | 2.11% | 0.41% | ||

| −0.004 | 119.40 | 110.43 | 119.13 | 117.55 | 115.48 | 105.66 | 117.72 |

| 7.51% | 0.22% | 1.55% | 3.28% | 11.50% | 1.41% | ||

| 20.43 | 20.78 | 20.17 | 20.13 | 20.33 | 19.62 | 20.06 | |

| 1.72% | 1.24% | 1.47% | 0.50% | 3.95% | 1.78% | ||

| −0.003 | 121.74 | 110.71 | 122.20 | 120.54 | 115.45 | 106.74 | 122.04 |

| 9.07% | 0.37% | 0.99% | 5.17% | 12.33% | 0.25% | ||

| 20.52 | 20.86 | 20.30 | 20.30 | 20.31 | 19.58 | 20.08 | |

| 1.67% | 1.09% | 1.07% | 1.03% | 4.58% | 2.17% | ||

| −0.002 | 122.10 | 112.04 | 125.88 | 125.16 | 115.19 | 110.22 | 126.47 |

| 8.25% | 3.09% | 2.51% | 5.66% | 9.74% | 3.58% | ||

| 20.66 | 20.79 | 20.55 | 20.53 | 20.47 | 20.02 | 20.11 | |

| 0.63% | 0.54% | 0.64% | 0.94% | 3.10% | 2.70% | ||

| −0.001 | 123.39 | 112.79 | 134.72 | 134.83 | 113.54 | 118.13 | 136.72 |

| 8.59% | 9.18% | 9.27% | 7.99% | 4.27% | 10.80% | ||

| 21.04 | 20.39 | 20.64 | 20.44 | 20.10 | 20.44 | 20.29 | |

| 3.12% | 1.91% | 2.85% | 4.48% | 2.89% | 3.59% | ||

| 0 | 123.83 | 112.42 | 136.43 | 136.33 | 107.39 | 122.88 | 137.17 |

| 9.22% | 10.17% | 10.09% | 13.28% | 0.77% | 9.96% | ||

| 21.33 | 19.33 | 20.71 | 20.07 | 15.72 | 14.71 | 19.16 | |

| 9.34% | 2.91% | 5.89% | 26.30% | 31.03% | 10.16% | ||

| Parameters | Values | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turbulence Models | SST k-omega | Spalart-Allmaras | ||

| Materials | Density: Ideal-gas Viscosity: Sutherland law Cp (j/kg-k): 1006.43 | Density: Ideal-gas Viscosity: Sutherland law Cp (j/kg-k): 1006.43 | ||

| Initial conditions | Mach number: 10 Static pressure: 576 Pa Static Temperature: 81.2 K | Mach number: 10 Static pressure: 576 Pa Static Temperature: 81.2 K | ||

| Boundary conditions | INLET: pressure far field | Intensity and Viscosity ratio 1% and 1 | INLET: pressure far field | Turbulent Viscosity ratio 1 |

| OUTLET: pressure outlet | Intensity and Viscosity ratio 1% and 1 | OUTLET: pressure outlet | Turbulent Viscosity ratio 1 | |

| WALL: no-slip, isothermal wall, 311 K | WALL: no-slip, isothermal wall, 311 K | |||

| Solver | Density-based solver Flux: ROE/AUSM | Density-based solver Flux: ROE/AUSM | ||

| Spatial discretization | Gradient: least-squares cell-based Gradient limiter: TVD slope limiter Flow: second-order upwind Turbulent kinetic energy: second-order upwind Specific dissipation rate: second-order upwind | Gradient: least-squares cell-based Gradient limiter: TVD slope limiter Flow: second-order upwind Modified turbulent viscosity: second-order upwind | ||

| Naca0012 Models | x/L (m) (P/Pt, T/Tt and Error Ratios) | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −0.007 | −0.006 | −0.005 | −0.004 | −0.003 | −0.002 | −0.001 | 0 | |||||||||

| 103.63 | 18.15 | 114.55 | 20.19 | 117.87 | 20.28 | 119.40 | 20.43 | 121.74 | 20.52 | 122.10 | 20.66 | 123.39 | 21.04 | 123.83 | 21.33 | |

| Blunt trailing edge (Airfoil tools) | 103.18 | 19.92 | 114.22 | 20.42 | 119.39 | 20.67 | 122.54 | 20.79 | 123.76 | 20.77 | 124.79 | 20.68 | 127.22 | 20.15 | 128.97 | 17.89 |

| 0.44% | 9.73% | 0.28% | 1.13% | 1.29% | 1.93% | 2.63% | 1.79% | 1.65% | 1.19% | 2.20% | 0.08% | 3.10% | 4.24% | 4.15% | 16.11% | |

| Sharp trailing edge (NACA4) | 102.66 | 19.86 | 113.79 | 20.36 | 119.55 | 20.64 | 122.78 | 20.77 | 124.02 | 20.76 | 125.06 | 20.69 | 127.61 | 20.22 | 129.58 | 18.60 |

| 0.93% | 9.41% | 0.67% | 0.85% | 1.43% | 1.76% | 2.83% | 1.69% | 1.87% | 1.17% | 2.42% | 0.14% | 3.42% | 3.91% | 4.64% | 12.76% | |

| Sharp trailing edge (132 points definition formula) | 77.97 | 15.13 | 97.58 | 16.86 | 103.96 | 18.50 | 104.21 | 19.28 | 105.75 | 20.05 | 108.20 | 20.66 | 103.79 | 19.77 | 93.43 | 18.03 |

| 24.76% | 16.63% | 14.81% | 16.50% | 11.80% | 8.79% | 12.72% | 5.61% | 13.14% | 2.30% | 11.39% | 0.02% | 15.89% | 8.88% | 24.55% | 15.46% | |

| Sharp trailing edge (264 points definition formula) | 119.80 | 20.26 | 119.73 | 20.40 | 120.27 | 20.52 | 122.17 | 20.75 | 122.91 | 20.86 | 123.40 | 20.96 | 123.19 | 20.89 | 122.81 | 18.93 |

| 15.61% | 11.64% | 4.52% | 1.03% | 2.04% | 1.18% | 2.32% | 1.59% | 0.96% | 1.66% | 1.06% | 1.44% | 0.17% | 0.73% | 0.82% | 11.22% | |

| Sharp trailing edge (200 points definition formula) | 95.25 | 16.55 | 121.04 | 19.38 | 122.33 | 20.45 | 123.19 | 20.62 | 125.00 | 20.67 | 126.53 | 20.65 | 129.63 | 20.27 | 132.27 | 18.76 |

| 8.09% | 8.82% | 5.67% | 3.99% | 3.79% | 0.81% | 3.17% | 0.95% | 2.67% | 0.70% | 3.62% | 0.06% | 5.06% | 3.67% | 6.81% | 12.04% | |

| Sharp trailing edge (400 points definition formula) | 121.54 | 20.48 | 121.59 | 20.59 | 121.84 | 20.68 | 122.37 | 20.86 | 122.41 | 20.94 | 122.24 | 20.89 | 116.32 | 20.06 | 108.33 | 18.96 |

| 17.28% | 12.80% | 6.14% | 1.96% | 3.37% | 1.96% | 2.49% | 2.13% | 0.55% | 2.06% | 0.11% | 1.09% | 5.73% | 4.69% | 12.52% | 11.08% | |

| Naca0012 Models | x/L (m) (P/Pt, T/Tt and Error Ratios) | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −0.007 | −0.006 | −0.005 | −0.004 | −0.003 | −0.002 | −0.001 | 0 | |||||||||

| 103.63 | 18.15 | 114.55 | 20.19 | 117.87 | 20.28 | 119.40 | 20.43 | 121.74 | 20.52 | 122.10 | 20.66 | 123.39 | 21.04 | 123.83 | 21.33 | |

| Blunt trailing edge (Airfoil tools) | 101.31 | 19.82 | 113.30 | 20.39 | 119.08 | 20.68 | 122.32 | 20.80 | 123.57 | 20.79 | 124.63 | 20.71 | 127.14 | 20.19 | 128.99 | 17.84 |

| 2.24% | 9.22% | 1.09% | 0.97% | 1.03% | 1.94% | 2.45% | 1.85% | 1.50% | 1.29% | 2.07% | 0.21% | 3.04% | 4.05% | 4.16% | 16.35% | |

| Sharp trailing edge (NACA4) | 90.39 | 17.18 | 114.58 | 19.26 | 124.38 | 20.27 | 125.35 | 20.61 | 127.31 | 20.70 | 128.97 | 20.70 | 132.19 | 20.45 | 135.21 | 18.93 |

| 12.77% | 5.35% | 0.02% | 4.58% | 5.53% | 0.06% | 4.99% | 0.89% | 4.57% | 0.89% | 5.63% | 0.15% | 7.13% | 2.80% | 9.19% | 11.24% | |

| Sharp trailing edge (132 points definition formula) | 102.85 | 19.87 | 114.09 | 20.38 | 119.60 | 20.66 | 122.73 | 20.78 | 123.93 | 20.76 | 124.90 | 20.68 | 127.38 | 20.17 | 129.25 | 18.28 |

| 0.75% | 9.48% | 0.40% | 0.96% | 1.47% | 1.83% | 2.79% | 1.73% | 1.79% | 1.17% | 2.29% | 0.09% | 3.23% | 4.13% | 4.37% | 14.30% | |

| Sharp trailing edge (264 points definition formula) | 104.92 | 19.96 | 114.86 | 20.39 | 120.17 | 20.63 | 123.37 | 20.75 | 124.58 | 20.73 | 125.60 | 20.66 | 128.18 | 20.19 | 130.14 | 18.62 |

| 1.25% | 9.97% | 0.27% | 0.97% | 1.96% | 1.70% | 3.32% | 1.58% | 2.33% | 1.03% | 2.86% | 0.01% | 3.88% | 4.07% | 5.10% | 12.68% | |

| Sharp trailing edge (200 points definition formula) | 70.01 | 11.80 | 107.59 | 17.60 | 126.72 | 20.55 | 128.40 | 21.06 | 128.32 | 21.28 | 127.55 | 21.06 | 127.29 | 20.72 | 126.41 | 20.64 |

| 32.44% | 35.01% | 6.08% | 12.84% | 7.51% | 1.31% | 7.54% | 3.09% | 5.40% | 3.70% | 4.46% | 1.93% | 3.16% | 1.55% | 2.08% | 3.21% | |

| Sharp trailing edge (400 points definition formula) | 103.15 | 19.88 | 114.13 | 20.37 | 119.72 | 20.64 | 122.89 | 20.77 | 124.09 | 20.75 | 125.08 | 20.67 | 127.59 | 20.18 | 129.49 | 18.46 |

| 0.46% | 9.53% | 0.37% | 0.91% | 1.57% | 1.78% | 2.92% | 1.68% | 1.93% | 1.12% | 2.44% | 0.05% | 3.40% | 4.12% | 4.57% | 13.42% | |

| Naca0012 Models | x/L (m) (P/Pt, T/Tt and Error Ratios) | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −0.007 | −0.006 | −0.005 | −0.004 | −0.003 | −0.002 | −0.001 | 0 | |||||||||

| 103.63 | 18.15 | 114.55 | 20.19 | 117.87 | 20.28 | 119.40 | 20.43 | 121.74 | 20.52 | 122.10 | 20.66 | 123.39 | 21.04 | 123.83 | 21.33 | |

| Blunt trailing edge (Airfoil tools) | 108.52 | 18.91 | 119.50 | 20.41 | 122.48 | 20.57 | 125.76 | 20.69 | 127.09 | 20.68 | 128.25 | 20.63 | 131.32 | 20.18 | 133.78 | 18.38 |

| 4.72% | 4.17% | 4.32% | 1.10% | 3.91% | 1.42% | 5.33% | 1.28% | 4.39% | 0.80% | 5.04% | 0.18% | 6.43% | 4.11% | 8.04% | 13.80% | |

| Sharp trailing edge (NACA4) | 91.52 | 18.83 | 108.25 | 20.12 | 117.87 | 20.65 | 120.98 | 20.83 | 122.30 | 20.83 | 123.39 | 20.61 | 125.88 | 20.26 | 127.74 | 17.11 |

| 11.69% | 3.76% | 5.50% | 0.34% | 0.00% | 1.79% | 1.32% | 1.99% | 0.46% | 1.52% | 1.05% | 0.26% | 2.01% | 3.71% | 3.15% | 19.78% | |

| Sharp trailing edge (132 points definition formula) | 89.36 | 17.27 | 103.65 | 19.27 | 106.78 | 20.20 | 103.44 | 20.58 | 104.84 | 20.67 | 109.86 | 20.63 | 112.39 | 19.59 | 112.52 | 17.82 |

| 13.76% | 4.85% | 9.51% | 4.55% | 9.41% | 0.42% | 13.37% | 0.77% | 13.89% | 0.74% | 10.03% | 0.16% | 8.92% | 6.90% | 9.13% | 16.46% | |

| Sharp trailing edge (264 points definition formula) | 96.46 | 17.86 | 118.46 | 19.60 | 124.65 | 20.38 | 125.91 | 20.63 | 127.61 | 20.71 | 129.05 | 20.66 | 132.71 | 20.40 | 135.12 | 18.76 |

| 6.91% | 1.61% | 3.41% | 2.92% | 5.75% | 0.49% | 5.45% | 1.00% | 4.82% | 0.91% | 5.69% | 0.03% | 7.11% | 3.05% | 9.12% | 12.03% | |

| Sharp trailing edge (200 points definition formula) | 101.81 | 17.61 | 112.84 | 18.33 | 115.73 | 18.70 | 114.26 | 18.84 | 114.35 | 19.06 | 113.74 | 19.70 | 110.60 | 19.83 | 114.50 | 19.83 |

| 1.75% | 3.00% | 1.49% | 9.23% | 1.82% | 7.81% | 4.30% | 7.75% | 6.07% | 7.14% | 6.85% | 4.66% | 10.37% | 5.75% | 7.54% | 7.02% | |

| Sharp trailing edge (400 points definition formula) | 101.74 | 19.83 | 113.53 | 20.38 | 119.14 | 20.67 | 122.29 | 20.80 | 123.51 | 20.78 | 124.54 | 20.70 | 126.93 | 20.19 | 128.71 | 18.26 |

| 1.83% | 9.25% | 0.89% | 0.96% | 1.08% | 1.90% | 2.42% | 1.81% | 1.45% | 1.24% | 1.99% | 0.16% | 2.86% | 4.05% | 3.94% | 14.39% | |

| Simulation Configurations | Mean Error Ratios under Different Configurations | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ROE | AUSM | |||||

| P/Pt | T/Tt | U/Ut | P/Pt | T/Tt | U/Ut | |

| SST + blunt | 1.97% | 4.52% | 1.6% | 8.94% | 5.91% | 4.07% |

| SA + blunt | 24.04% | 24.61% | 2.39% | 3.62% | 5.56% | 1.14% |

| SST + NACA4 | 2.28% | 3.96% | 1.04% | 10.41% | 8.54% | 4.38% |

| SA + NACA4 | 4.42% | 2.16% | 1.9% | 8.52% | 3.55% | 1.4% |

| SST + 132 points | 16.13% | 9.27% | 2.95% | 4.32% | 2.88% | 2.21% |

| SA + 132 points | 8.58% | 9.70% | 2.41% | 8.91% | 6.31% | 3.91% |

| SST + 200 points | 4.86% | 3.88% | 0.96% | 8.02% | 7.94% | 1.77% |

| SA + 200 points | 5.87% | 1.18% | 1.55% | 7.83% | 4.63% | 1.76% |

| SST + 264 points | 3.44% | 3.81% | 1.23% | 7.95% | 2.81% | 0.7% |

| SA + 264 points | 8.42% | 3.39% | 1.73% | 5.19% | 5.03% | 4.08% |

| SST + 400 points | 6.02% | 4.72% | 1.66% | 13.60% | 22.17% | 1.83% |

| SA + 400 points | 8.66% | 6.36% | 2.06% | 12.65% | 12.06% | 0.95% |

| Simulation Configurations | Mean error Ratios under Different Configurations | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ROE | AUSM | |||||

| P/Pt | T/Tt | U/Ut | P/Pt | T/Tt | U/Ut | |

| SST + blunt | 2.20% | 4.49% | 1.53% | 8.16% | 13.63% | 5.25% |

| SA + blunt | 3.52% | 4.38% | 1.98% | 5.89% | 6.11% | 3.63% |

| SST + NACA4 | 6.23% | 3.25% | 2.36% | 5.96% | 8.19% | 2.07% |

| SA + NACA4 | 5.33% | 5.24% | 1.61% | 5.12% | 4.57% | 1.71% |

| SST + 132 points | 2.14% | 4.21% | 1.57% | 2.78% | 6.14% | 1.78% |

| SA + 132 points | 11.85% | 8.20% | 1.66% | 7.32% | 5.83% | 1.26% |

| SST + 200 points | 8.58% | 7.83% | 1.83% | 3.74% | 4.06% | 2.00% |

| SA + 200 points | 2.54% | 1.86% | 1.74% | 4.79% | 3.75% | 1.29% |

| SST + 264 points | 2.62% | 4.00% | 1.65% | 18.77% | 17.84% | 1.62% |

| SA + 264 points | 8.82% | 4.45% | 2.92% | 6.81% | 8.17% | 1.23% |

| SST + 400 points | 2.21% | 4.08% | 1.09% | 7.75% | 9.69% | 1.89% |

| SA + 400 points | 6.96% | 2.86% | 1.32% | 3.66% | 4.98% | 1.81% |

| Simulation Configurations | Mean Error Ratios under Different Configurations | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ROE | AUSM | |||||

| P/Pt | T/Tt | U/Ut | P/Pt | T/Tt | U/Ut | |

| SST + blunt | 5.27% | 3.36% | 1.68% | 9.47% | 6.02% | 2.86% |

| SA + blunt | 6.40% | 2.70% | 2.01% | 7.27% | 1.68% | 2.22% |

| SST + NACA4 | 3.15% | 4.14% | 2.28% | 15.30% | 8.00% | 2.38% |

| SA + NACA4 | 4.69% | 4.28% | 1.73% | 15.45% | 9.74% | 2.06% |

| SST + 132 points | 11.00% | 4.36% | 1.61% | 4.14% | 4.64% | 2.83% |

| SA + 132 points | 1.76% | 5.58% | 1.59% | 13.73% | 7.50% | 2.34% |

| SST + 200 points | 5.02% | 6.54% | 1.99% | 9.84% | 5.13% | 2.19% |

| SA + 200 points | 6.00% | 4.32% | 1.21% | 3.51% | 4.13% | 2.48% |

| SST + 264 points | 6.03% | 2.75% | 1.56% | 9.67% | 8.47% | 6.99% |

| SA + 264 points | 5.11% | 7.58% | 1.26% | 13.73% | 7.50% | 5.67% |

| SST + 400 points | 2.06% | 4.22% | 1.08% | 6.48% | 1.71% | 4.1% |

| SA + 400 points | 7.35% | 2.74% | 1.59% | 7.52% | 9.22% | 1.35% |

| Simulation Configurations | Mean error Ratios under Different Configurations | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ROE | AUSM | |||||

| P/Pt | T/Tt | U/Ut | P/Pt | T/Tt | U/Ut | |

| 12 + blunt | 1.97% | 4.52% | 1.60% | 8.94% | 5.91% | 4.07% |

| 16 + blunt | 2.20% | 4.49% | 1.53% | 8.16% | 13.63% | 5.25% |

| 20 + blunt | 5.27% | 3.36% | 1.68% | 9.47% | 6.02% | 2.86% |

| 12 + NACA4 | 2.28% | 3.96% | 1.04% | 10.41% | 8.54% | 4.38% |

| 16 + NACA4 | 6.23% | 3.25% | 2.36% | 5.96% | 8.19% | 2.07% |

| 20 + NACA4 | 3.15% | 4.14% | 2.28% | 15.30% | 8.00% | 2.38% |

| 12 + 132 points | 16.13% | 9.27% | 2.95% | 4.32% | 2.88% | 2.21% |

| 16 + 132 points | 2.14% | 4.21% | 1.57% | 2.78% | 6.14% | 1.78% |

| 20 + 132 points | 11.00% | 4.36% | 1.61% | 4.14% | 4.64% | 2.83% |

| 12 + 200 points | 4.86% | 3.88% | 0.96% | 8.02% | 7.94% | 1.77% |

| 16 + 200 points | 8.58% | 7.83% | 1.83% | 3.74% | 4.06% | 2.00% |

| 20 + 200 points | 5.02% | 6.54% | 1.99% | 9.84% | 5.13% | 2.19% |

| 12 + 264 points | 3.44% | 3.81% | 1.23% | 7.95% | 2.81% | 0.7% |

| 16 + 264 points | 2.62% | 4.00% | 1.65% | 18.77% | 17.84% | 1.62% |

| 20 + 264 points | 6.03% | 2.75% | 1.56% | 9.67% | 8.47% | 6.99% |

| 12 + 400 points | 6.02% | 4.72% | 1.66% | 13.60% | 22.17% | 1.83% |

| 16 + 400 points | 2.21% | 4.08% | 1.09% | 7.75% | 9.69% | 1.89% |

| 20 + 400 points | 2.06% | 4.22% | 1.08% | 6.48% | 1.71% | 4.1% |

| Simulation Configurations | Mean Error Ratios under Different Configurations | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ROE | AUSM | |||||

| P/Pt | T/Tt | U/Ut | P/Pt | T/Tt | U/Ut | |

| 12 + blunt | 24.04% | 24.61% | 2.39% | 3.62% | 5.56% | 1.14% |

| 16 + blunt | 3.52% | 4.38% | 1.98% | 5.89% | 6.11% | 3.63% |

| 20 + blunt | 6.40% | 2.70% | 2.01% | 7.27% | 1.68% | 2.22% |

| 12 + NACA4 | 4.42% | 2.16% | 1.90% | 8.52% | 3.55% | 1.40% |

| 16 + NACA4 | 5.33% | 5.24% | 1.61% | 5.12% | 4.57% | 1.71% |

| 20 + NACA4 | 4.69% | 4.28% | 1.73% | 15.45% | 9.74% | 2.06% |

| 12 + 132 points | 8.58% | 9.70% | 2.41% | 8.91% | 6.31% | 3.91% |

| 16 + 132 points | 11.85% | 8.20% | 1.66% | 7.32% | 5.83% | 1.26% |

| 20 + 132 points | 1.76% | 5.58% | 1.59% | 13.73% | 7.50% | 2.34% |

| 12 + 200 points | 5.87% | 1.18% | 1.55% | 7.83% | 4.63% | 1.76% |

| 16 + 200 points | 2.54% | 1.86% | 1.74% | 4.79% | 3.75% | 1.29% |

| 20 + 200 points | 6.00% | 4.32% | 1.21% | 3.51% | 4.13% | 2.48% |

| 12 + 264 points | 8.42% | 3.39% | 1.73% | 5.19% | 5.03% | 4.08% |

| 16 + 264 points | 8.82% | 4.45% | 2.92% | 6.81% | 8.17% | 1.23% |

| 20 + 264 points | 5.11% | 7.58% | 1.26% | 13.73% | 7.50% | 5.67% |

| 12 + 400 points | 8.66% | 6.36% | 2.06% | 12.65% | 12.06% | 0.95% |

| 16 + 400 points | 6.96% | 2.86% | 1.32% | 3.66% | 4.98% | 1.81% |

| 20 + 400 points | 7.35% | 2.74% | 1.59% | 7.52% | 9.22% | 1.35% |

| Simulation Configurations | Mean Error Ratios under Different Configurations | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 m | 16 m | 20 m | |||||||

| P/Pt | T/Tt | U/Ut | P/Pt | T/Tt | U/Ut | P/Pt | T/Tt | U/Ut | |

| SST + blunt | 1.97% | 4.52% | 1.60% | 2.20% | 4.49% | 1.53% | 5.27% | 3.36% | 1.68% |

| SA + blunt | 24.04% | 24.61% | 2.39% | 3.52% | 4.38% | 1.98% | 6.40% | 2.70% | 2.01% |

| SST + NACA4 | 2.28% | 3.96% | 1.04% | 6.23% | 3.25% | 2.36% | 3.15% | 4.14% | 2.28% |

| SA + NACA4 | 4.42% | 2.16% | 1.90% | 5.33% | 5.24% | 1.61% | 4.69% | 4.28% | 1.73% |

| SST + 132 points | 16.13% | 9.27% | 2.95% | 2.14% | 4.21% | 1.57% | 11.00% | 4.36% | 1.61% |

| SA + 132 points | 8.58% | 9.70% | 2.41% | 11.85% | 8.20% | 1.66% | 1.76% | 5.58% | 1.59% |

| SST + 200 points | 4.86% | 3.88% | 0.96% | 8.58% | 7.83% | 1.83% | 5.02% | 6.54% | 1.99% |

| SA + 200 points | 5.87% | 1.18% | 1.55% | 2.54% | 1.86% | 1.74% | 6.00% | 4.32% | 1.21% |

| SST + 264 points | 3.44% | 3.81% | 1.23% | 2.62% | 4.00% | 1.65% | 6.03% | 2.75% | 1.56% |

| SA + 264 points | 8.42% | 3.39% | 1.73% | 8.82% | 4.45% | 2.92% | 5.11% | 7.58% | 1.26% |

| SST + 400 points | 6.02% | 4.72% | 1.66% | 2.21% | 4.08% | 1.09% | 2.06% | 4.22% | 1.08% |

| SA + 400 points | 8.66% | 6.36% | 2.06% | 6.96% | 2.86% | 1.32% | 7.35% | 2.74% | 1.59% |

| Simulation Configurations | Mean Error Ratios under Different Configurations | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 m | 16 m | 20 m | |||||||

| P/Pt | T/Tt | U/Ut | P/Pt | T/Tt | U/Ut | P/Pt | T/Tt | U/Ut | |

| SST + blunt | 8.94% | 5.91% | 4.07% | 8.16% | 13.63% | 5.25% | 9.47% | 6.02% | 2.86% |

| SA + blunt | 3.62% | 5.56% | 1.14% | 5.89% | 6.11% | 3.63% | 7.27% | 1.68% | 2.22% |

| SST + NACA4 | 10.41% | 8.54% | 4.38% | 5.96% | 8.19% | 2.07% | 15.30% | 8.00% | 2.38% |

| SA + NACA4 | 8.52% | 3.55% | 1.40% | 5.12% | 4.57% | 1.71% | 15.45% | 9.74% | 2.06% |

| SST + 132 points | 4.32% | 2.88% | 2.21% | 2.78% | 6.14% | 1.78% | 4.14% | 4.64% | 2.83% |

| SA + 132 points | 8.91% | 6.31% | 3.91% | 7.32% | 5.83% | 1.26% | 13.73% | 7.50% | 2.34% |

| SST + 200 points | 8.02% | 7.94% | 1.77% | 3.74% | 4.06% | 2.00% | 9.84% | 5.13% | 2.19% |

| SA + 200 points | 7.83% | 4.63% | 1.76% | 4.79% | 3.75% | 1.29% | 3.51% | 4.13% | 2.48% |

| SST + 264 points | 7.95% | 2.81% | 0.70% | 18.77% | 17.84% | 1.62% | 9.67% | 8.47% | 6.99% |

| SA + 264 points | 5.19% | 5.03% | 4.08% | 6.81% | 8.17% | 1.23% | 13.73% | 7.50% | 5.67% |

| SST + 400 points | 13.60% | 22.17% | 1.83% | 7.75% | 9.69% | 1.89% | 6.48% | 1.71% | 4.10% |

| SA + 400 points | 12.65% | 12.06% | 0.95% | 3.66% | 4.98% | 1.81% | 7.52% | 9.22% | 1.35% |

| Parameters | Values | Optimal Mean Error Ratios of P/Pt | Optimal Mean Error Ratios of T/Tt | Optimal Mean Error Ratios of U/Ut | Optimal Total Mean Error Ratios | Maximum Accuracy Decline Degree Between Optimal Results | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trailing edge shapes | Blunt trailing edge | Airfoil tools | 1.97% | 4.52% | 1.60% | 2.70% | 31.73% (Between blunt and sharp) | |

| SST + 12 m + ROE | ||||||||

| Sharp trailing edge | NACA4 generator | 2.28% | 3.96% | 1.04% | 2.42% | 34.76% (Among sharp trailing edge modeling methods) | ||

| SST + 12 m + ROE | ||||||||

| Definition formula | 132 points | 2.14% | 4.21% | 1.57% | 2.64% | |||

| SST + 16 m + ROE | ||||||||

| 264 points | 2.62% | 4.00% | 1.65% | 2.76% | ||||

| SST + 16 m + ROE | ||||||||

| 200 points | 2.54% | 1.86% | 1.74% | 2.05% | ||||

| SA + 16 m + ROE | ||||||||

| 400 points | 2.06% | 4.22% | 1.08% | 2.454% | ||||

| SST + 20 m + ROE | ||||||||

| Far-field distances | 12 m | 2.28% | 3.96% | 1.04% | 2.42% | 19.88% (Among three distances) | ||

| SST + NACA4 + ROE | ||||||||

| 16 m | 2.54% | 1.86% | 1.74% | 2.05% | ||||

| SA + 200 points + ROE | ||||||||

| 20 m | 2.06% | 4.22% | 1.08% | 2.45% | ||||

| SST + 400 points + ROE | ||||||||

| Turbulence models | SST | 2.28% | 3.96% | 1.04% | 2.42% | 18.45% (Between SST and SA) | ||

| 12 m + NACA4 + ROE | ||||||||

| SA | 2.54% | 1.86% | 1.74% | 2.05% | ||||

| 16 m + 200 points + ROE | ||||||||

| Flux types | ROE | 2.54% | 1.86% | 1.74% | 2.05% | 53.2% (Between ROE and AUSM) | ||

| SA + 200 points + 16 m | ||||||||

| AUSM | 4.32% | 2.88% | 2.21% | 3.14% | ||||

| SST + 132points + 12 m | ||||||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, L.; Zhang, G. Influence Analysis of Simulation Parameters on Numerical Prediction of Compressible External Flow Field Based on NACA0012 Airfoil under Hypersonic Speed. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 6083. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12126083

Yang L, Zhang G. Influence Analysis of Simulation Parameters on Numerical Prediction of Compressible External Flow Field Based on NACA0012 Airfoil under Hypersonic Speed. Applied Sciences. 2022; 12(12):6083. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12126083

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Lu, and Guangming Zhang. 2022. "Influence Analysis of Simulation Parameters on Numerical Prediction of Compressible External Flow Field Based on NACA0012 Airfoil under Hypersonic Speed" Applied Sciences 12, no. 12: 6083. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12126083

APA StyleYang, L., & Zhang, G. (2022). Influence Analysis of Simulation Parameters on Numerical Prediction of Compressible External Flow Field Based on NACA0012 Airfoil under Hypersonic Speed. Applied Sciences, 12(12), 6083. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12126083