Abstract

At the end of any orthodontic treatment, retention is a necessary phase. Unfortunately, the current retention devices and the lack of proper oral hygiene on the part of patients lead to the accumulation of dental plaque, periodontal inflammation, and gingival retraction. Our retrospective study included 116 adult patients wearing various types of orthodontic retainers. To quantitatively determine the accumulation of dental plaque, we used the Quigley–Hein plaque index modified by Turesky and the Navy plaque index modified by Rustogi. Another studied parameter was related to the gingival recession associated with retention devices. We had investigated the correctness of patients’ dental hygiene, their preferences for auxiliary means of oral hygiene, the consistency with which they wear the mobile retainers, and respect the orthodontist’s instructions; we also investigated the inconveniences and the accidents that may occur during the retention period. Statistical analysis showed that plaque accumulation is significantly lower in the case of mobile retainer than fixed retainer wearers; the exception was the Hawley plate, where the interdental plaque was more than in all the other studied retainers. Periodontal recessions were more frequent in the case of fixed retainer wearing. Flossing was the most commonly used auxiliary mean for oral hygiene. The compliance of women in wearing vacuum-formed retainers was better than that of men. Patients with a class III history had more plaque accumulation, and class II/1 had the most problems related to detachment/damage of fixed retainers. Mobile retainers proved better results for oral hygiene, but fixed retainers cannot be waved.

1. Introduction

Periodontal disease is one of the oldest pathologies as it occurs in most people examined from the past to the present day, regardless of geographical location and age [1,2,3]. Periodontitis is an inflammatory condition that starts with the formation of dental plaque at the gingival margin. The microbial load of the dental plaque generates an inflammatory response that initially affects only the gingival margin; in conditions such as individual susceptibility, behavioral factors, or general pathologies, the supporting tissues are affected [4]. The loss of periodontal tissue is closely linked to inflammation and is influenced by infections and interactions between bacterial microorganisms like Fusobacterium nucleatum, Porphyromonas gingivalis, Tannerella forsythia, Filifactor alocis, Treponema denticola, and Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans [4,5]; nowadays, the determining role of the microbial factor and the immune response in the etiology of periodontal disease is supported [3].

In literature, there are controversial opinions on the effect of orthodontic retainers on the periodontium. Some authors found no significant difference between stainless steel fixed retainers bonded to the anterior teeth and canines only in terms of periodontal outcomes, at 12-month and 3-year follow-ups [6,7]. Periodontal damages caused by mandibular Hawley retainers comparatively with mandibular stainless steel fixed retainers proved no significant difference in a 3-year follow-up [7]. No significant difference in the survival rate of multistrand stainless steel fixed retainers and esthetic retainers made of polyethylene woven ribbon or polyethylene fiber-reinforced resin composite was found [8]. Orthodontic fixed retainers seem to be compatible with periodontal health or at least not related to severe detrimental effects on the periodontium. Other authors [8] found increased plaque accumulation, gingival recession, increase in periodontal pockets’ depth, marginal gingival recession, and calculus accumulation in fixed retainers wearers. The adherent microorganisms of the biofilm are different from the free planktonic bacteria because they could not be affected by antibiotics, disinfectants, and the body’s defense agents [9]. Other aggressive factors for periodontal tissues are tartar, incorrectly adapted fillings, inadequate prosthetic works, orthodontic braces, rings, and retainers [10,11,12].

Gingival recession is the movement of the free gingival margin in the apical direction from the enamel-cement junction. The etiology is multifactorial still, periodontal disease and mechanical trauma are causes for gingival recessions. Orthodontic treatment can help develop gingival recession [11]. One possible mechanism is the displacement of the teeth’ roots closer or even outside the alveolar cortex, leading finally to bone dehiscence; gingival margin without proper bone support migrates apically, and roots are exposed [8,12]. In addition, a fixed orthodontic appliance creates retentive areas for the bacterial plaque. Inadequate removal of bacterial plaque and gingival inflammation leads to periodontal degradation [11,13].

Mlinek et al. (1973) [14] quantified results came across, as in two types of gingival recession:

- smaller than 3 mm in both shallow and narrow dimensions;

- larger than 3 mm in both deep and wide dimensions.

Retention is an important treatment phase since the periodontal tissues are affected by the modified position of the teeth, and they need time to reorganize and settle after the active treatment [15]. The teeth may be in an unstable position which is vulnerable to the action of the soft tissues. Other reasons for recurrence are the continuous increase and constant change of occlusion ratios throughout a lifetime [16]. For artificial retention are used Hawley retainers (HRs), removable vacuum-formed retainers (VFRs), fixed oral retainers, and various functional orthodontic devices [16,17,18,19].

The Hawley retainer designed by Charles Hawley in 1920 (Figure 1) has proven its effectiveness for more than a century. Along with the retention, it can also be an active orthodontic instrument which, through the action of mechanical forces, produces small changes such as the closure of the remaining interdental spaces due to the anchoring by the orthodontic rings [18].

Figure 1.

Hawley retainer used in the study.

However, in an attempt to achieve a more aesthetic retention method in 1971 a transparent retainer was designed [20] (Figure 2). Vacuum-formed retainers (VFRs) are easier to make and cheaper than the Hawley retainers (HRs). The VFRs are easy to replace if they deteriorate or fracture. Patients’ compliance is much better when wearing VFRs because they do not interfere with the palate and cause vomiting reflex. Their occlusal thickness prevents vertical movements that are possible in the case of HRs [16,17,18,19,20].

Figure 2.

Inferior vacuum-formed retainer used in the study.

Fixed retainers (Figure 3) were introduced into clinical practice in the 1970s to prevent recurrences in the lower inter-canine zone are now commonly used [8,12]. Their advantages are aesthetics, effectiveness, the long-lasting, and the character of being fixed by which their behavior does not depend on the patient’s cooperation. The disadvantages are fragility, the vulnerable bonding technique, and the possibility of causing periodontal pathology due to a more difficult oral hygiene [8,12].

Figure 3.

Inferior fixed retainer used in the study.

Our retrospective study aimed to determine and quantify the impact of the most common orthodontic retainers on dental hygiene and periodontal tissues by the following variables:

- -

- the patient’s sex;

- -

- Turesky Modified Quigley–Hein Plaque Index (TMQHPI);

- -

- Rustogi Modification of the Navy Plaque Index (RMNPI);

- -

- gingival recession;

- -

- retainer’s type

- -

- initial orthodontic diagnosis

The studied hypotheses were:

- -

- orthodontic retainers negatively influence periodontal health;

- -

- patients with fixed retainers face more periodontal problems than those with mobile retainers;

- -

- periodontal pathology of orthodontic retention wearers differs depending on gender;

2. Material and Method

The Rustogi Modification of the Navy Plaque Index (RMNPI) [21] has been proved a very high precision in determining the dental hygiene status because of the detailed examination of the vestibular and oral surfaces of the teeth, divided into nine areas, 18 in total. The score is 0 if the bacterial plaque is not present; if BP exists, the score of the affected area is denoted by 1. The index per tooth = sum of all areas marked with 1. The third molars are not in the calculation. The index value is determined by dividing the sum of the indices calculated for every present tooth by the number of teeth. The value of RMNPI could be between 0 and 1, 0 signifying excellent dental hygiene, and 1 a lack of hygiene.

Turesky Modified Quigley–Hein Plaque Index (TMQHPI) is very sensitive to changes in dental hygiene [22]. To determine this index all the present teeth except the third molars are taken into account. The presence of bacterial plaque is determined by the examination of the vestibular and oral surfaces of the teeth, so the maximum number of investigated surfaces will be 56. The amount of bacterial plaque (BP) will be quantified as follows: 0 = absence of BP; 1 = BP as a discontinuous line at the gingival margin; 2 = BP as a continuous line less than 1 mm width at the cervical level; 3 = continuous BP greater than 1 mm in width but not reaching 1/3 of the surface; 4 = BP covering between 1/3 and 2/3 of the surface; 5 = BP surpassing more than 2/3 of the surface [22]. The average TMQHPI will be the total number of points for each tooth/total number of examined areas Index interpretation: <0–1—excellent hygiene; <1–2—good hygiene; <2–3—moderate hygiene; <3–4—poor hygiene; <4–5—absent hygiene.

We chose to use these two indices in determining the dental plaque because they are easy to evaluate, and their accuracy is high [21,22].

The recessions were determined on all the teeth included in retention systems as the shortest distance from the cementoenamel junction to the deepest curvature of the gingival margin by using a standard periodontal probe.

Our study included a group of 116 patients aged between 18.3 and 27.6 years, with a mean age of 23.8. The patients were from our town, Târgu Mureș, and its surroundings. The inclusion criteria were as follows:

- -

- the absence of gingival recessions before the orthodontic treatment;

- -

- fixed orthodontic appliance placed for at least one year;

- -

- patients who wearing a fixed or mobile restraint device at the time of the examination;

- -

- fixed retentions performed with multistranded wires. The balanced study group consisted of 45 men (38.79% of the total) and 71 women (61.21% of the total). The selected patients were asked to complete an 11-question questionnaire regarding their oral health status (Appendix A). The questionnaire aims to investigate the oral hygiene habits, to collect information about the retention type and the compliance of the patients wearing them. The questionnaire was designed according to our clinical experience and theoretical knowledge.

After the patient filled up the questionnaire, we performed the clinical examination using the dental mirrors, the Williams periodontal probes, and the plaque-revealing tablets. During the clinical examination the following indices were determined:

- -

- the Quigley–Hein plate index modified by Turesky

- -

- the Navy plaque index was modified by Rustogi. For determining the RMNPI we used the following strategy: the gumline areas were divided into subgroups A, B, C, and the interproximal tooth areas were assigned to subgroups D, F.

Based on a comprehensive study of the state-of-the-art power analysis research [23,24,25] and the supposed data distribution on other similar research (verified after we have already obtained the data) we established 100 as a minimal sample size. Finally, we have performed the study on a sample of 116 in case some data fail to pass the quality assessments (missing data, for instance).

For the verification of the normal distribution of percentages regarding the choice of an appropriate study design [26], we used the Shapiro–Wilk test (SW test) [27]. The selection of the SW test instead of the One-sample Kolmogorov–Smirnov test or the Lilliefors test was because Shapiro–Wilk test has the highest statistical power and works well with few data [28]. Even if it can be applied at different significance levels (e.g., 0.01, 0.1), we chose the significance level αsw = 0.05 considering it the most appropriate. As a good practice, we recommend the SW test together with the visual interpretation of the normality by using the QQ plot. We do not want to overcomplicate the statistics because the paper regards the medical staff, so we do not present the QQ plots [29] associated with the data. For detecting a significant difference between the values (extremely high and extremely low ones), it was applied the two-sided Grubbs outliers detection test [30] with the significance level αgr = 0.5 (considered the most appropriate value for the significance level). The choosing of the Grubbs test was based on the requirement of data normality, being for our data the most appropriate outliers detection test. The Grubbs test can detect a single extreme (low or high value) at one application; if the test detects an extreme value or a value statistically furthest from the rest at the first application, it could be repeated until no extremes are found. The minimal sample size requirement for the application of the test is 3.

The Pearson correlation coefficient [31] was used instead of Spearman Correlation Coefficient that we recommend for the nonparametric cases when the normal assumption fails.

3. Results

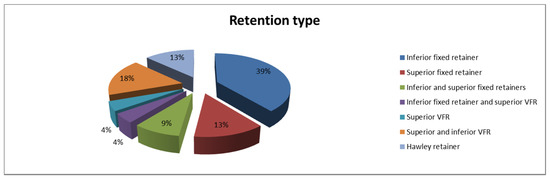

According to our analysis (Figure 4), male patients of the study group wore: inferior fixed retainer 39%, superior and inferior VFRs 18%, superior fixed retainer 13%, Hawley retainer 13%, inferior together with superior fixed retainers 9%, inferior fixed retainer together with superior VRF 4%, and only superior VFR 4%. Applying the SW test on data from Figure 4, the p-value = 0.06 was obtained; 0.06 > αsw indicated the passing of the normality assumption. The Grubbs test results indicate 39% as a statistically significantly higher value than the rest. Since the data passed the normality assumption, the mean was chosen as the central tendency indicator. The mean of the values is 14.29%, with a standard deviation (SD) = 12.02 and variance = 144.48.

Figure 4.

Male patients’ distribution according to retention type.

For the study group involving male patients, the fixed lower retainer was present in the highest percentage of 39% while the lowest percentage values of 4% were observed in the upper VFR and in using the lower fixed retainer and the upper VFR together.

83% of male patients have had at least one descaling since retention.57% of male patients stated that they used dental floss as an auxiliary means for oral hygiene; 30% used interdental brushes; 26% used oral mouthwash; 26% used the water flosser. 9% stated that they did not use any auxiliary method of oral hygiene but only regular toothbrushing.

In this group, 39 patients (87%) felt the need for a scaling procedure during retention time; 77% of them wore fixed retainers, 13% wore VRFs, and 10% were patients with Hawley retainers.

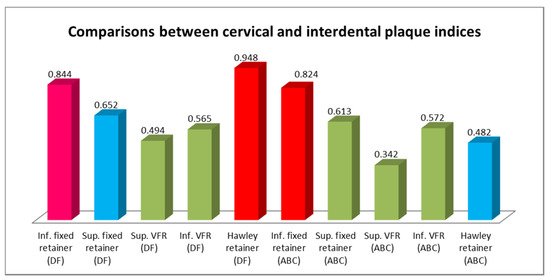

Figure 5 data passed the normality assumption, with SW test p-value = 0.74, αsw = 0.05 significance level, where 0.74 > αsw. In the case of the Navy plaque index modified by Rustogi, the male study group, for detecting values that are statistically significantly higher or lower than the rest of the values it was applied the two-sided Grubbs test since the data passed the normality assumption.

Figure 5.

Navy plaque index modified by Rustogi, male study group. DF = interproximal areas ABC = gumline areas.

At the first application of the test, it was not detected any extremely high or low-value just only a value, 0.948 (corresponding to Hawley retainer–DF) that was statistically furthest (higher) from the rest. After removing 0.948, applying the Grubbs test again it was detected 0.342 (Superior VFR–ABC) as a statistically furthest (lower) value from the rest. By consecutive application of the test were detected the following values in the order: 0.844 (Inferior fixed retainer-DF), 0.824 (Inferior fixed retainer-ABC), 0.652 (Superior fixed retainer-DF), 0.613 (Superior fixed retainer-ABC), 0.482 (Hawley retainer-ABC), and finally 0.494 (Superior VFR-DF). Regarding the Navy plaque index modified by Rustogi applied for the male study group, the statistically highest value was obtained when examining patients wearing Hawley retainer (DF). The statistically lowest value was obtained for Superior VFR–ABC.

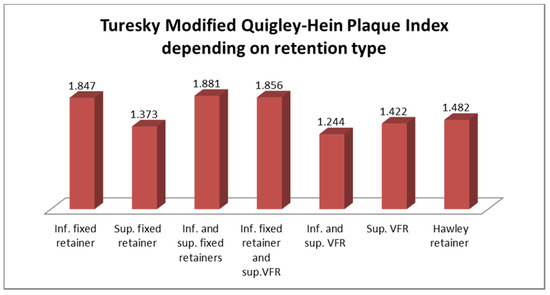

Figure 6 data passed the normality assumption, with SW test p-value = 0.123 (0.123 > αsw; αsw = 0.05). Based on this result it was applied the Grubbs test and the following values were statistically furthest from the rest: 1st application identified 1.244 (Inferior and superior VFR), followed by 1.373 (Superior fixed retainer), 1.422 (Superior VFR), 1.482 (Hawley retainer) and finally 1.881 (Inferior and superior fixed retainers). Regarding the Quigley–Hein plaque index modified by Turesky applied for the male study group, the highest value was obtained when examining patients wearing inferior and superior fixed retainers (it is the highest, but not statistically significantly higher than those others). The statistically lowest value was of Inf. and sup. VFR.

Figure 6.

Turesky Modified Quigley–Hein Plaque Index, male study group.

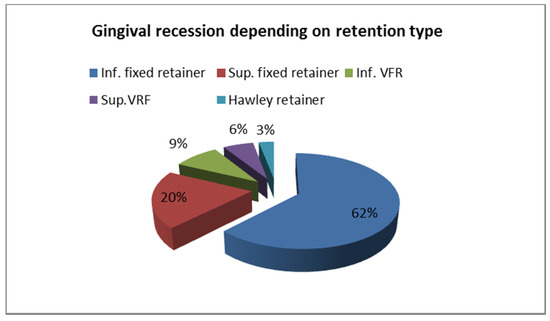

Regarding the gingival recessions (Figure 7) associated with retention devices in the group of male patients, 28 (62.2%) had gingival recessions of 1–3 mm in the lower arch, and 17 (37.7%) of them had recessions of 1–2.5 mm in the upper; 15 patients (33%) had gingival recessions in both dental arches at clinical examination.

Figure 7.

Gingival recession, male group.

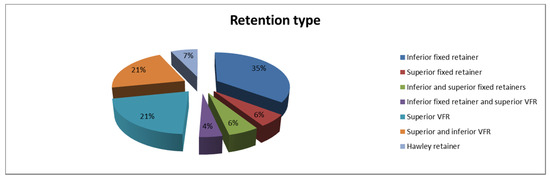

According to our analysis, female patients of the study group wore (Figure 8): inferior fixed retainer 35%, superior VFRs 21%, both inferior and superior VFRs 21%, Hawley retainer 7%, superior fixed retainer 6%, both inferior and superior fixed retainers 6%, and only 4% wore inferior fixed retainer together with superior VFR. The SW test with the significance level αsw = 0.05 was applied for the data presented in Figure 8; we get the p-value = 0.076, 0.76 > αsw indicated the passing of the normality assumption. The two-sided Grubbs outliers test indicated that no value is extremely high or low, just the value of 35% is furthest from the rest. The calculated mean was 14.29, SD = 11.66, and variance = 136.96.

Figure 8.

Female patients’ distribution according to retention type.

62% of female patients stated that they use dental floss as an auxiliary mean for oral hygiene; 35% used interdental brushes; 28% used an oral mouthwash; 19% used the water flosser. 2% stated that they do not use any auxiliary method of oral hygiene but only regular toothbrushing.

In this study group, 51 patients (72%) needed at least one scaling procedure during retention time; 80% of them wore fixed retainers, 12% wore VRFs, and 8% were patients with Hawley retainers (Figure 9 and Figure 10).

Figure 9.

Navy plaque index modified by Rustogi, female study group. DF = interproximal areas ABC = gumline areas.

Figure 10.

Turesky Modified Quigley-Hein Plaque Index, female study group.

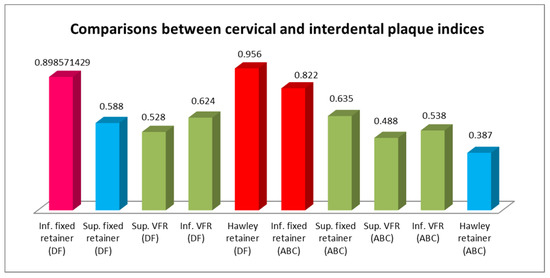

Figure 9 data passed the normality assumption, with SW test p-value = 0.41 (0.41 > αsw; αsw = 0.05). Based on this result it was applied the two-sided Grubbs test with αgr = 0.05 consecutively identifying the following values as statistically furthest from the rest. 1st application identified 0.956 (Hawley retainer-DF), followed by 0.898 (Inferior fixed retainer-DF), 0.822 (Inferior fixed retainer-ABC), 0.387 (Hawley retainer -ABC), 0.488 (Superior VFR-ABC), 0.528 (Superior VFR-DF), and finally 0.588 (Superior fixed retainer -DF). Regarding the Navy plaque index modified by Rustogi applied for the female study group, the statistically highest value was obtained when examining patients wearing Hawley retainer (DF). The statistically lowest value was obtained for the Hawley retainer (ABC).

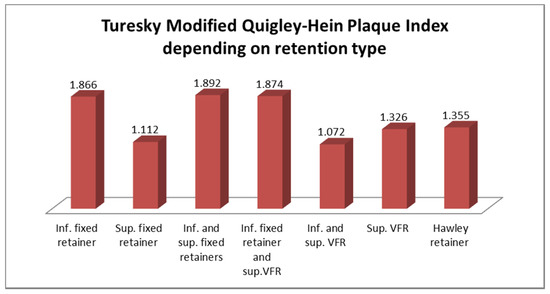

Figure 10 data passed the normality assumption, with SW test p-value = 0.7 (0.7 > αsw; αsw = 0.05). Based on this result it was applied the two-sided Grubbs test with αgr = 0.05 consecutively identifying the following values as statistically furthest from the rest. 1st application identified 1.072 (Inferior and superior VFR), followed by 1.112 (Superior fixed retainer), 1.326 (Superior VFR), 1.355 (Hawley retainer), and finally 1.892 (Inferior fixed retainer). Regarding the Turesky Modified Quigley-Hein Plaque Index applied for the female study group, the statistically highest value was obtained when examining patients wearing an Inferior fixed retainer. The statistically lowest value was obtained for the Inferior and superior VFR.

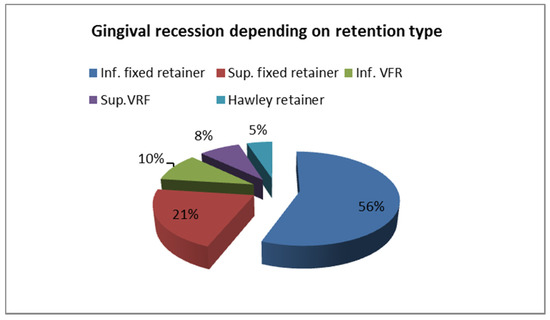

Regarding the gingival recessions (Figure 11) associated with retention devices of female patients, 41 (57.7%) had gingival recessions of 1–3 mm in the lower arch, and 21 (29.5%) of them had gingival recessions of 1–2.5 mm in the upper arch; 19 patients (26%) had gingival recessions in both dental arches at clinical examination.

Figure 11.

Gingival recession, female group.

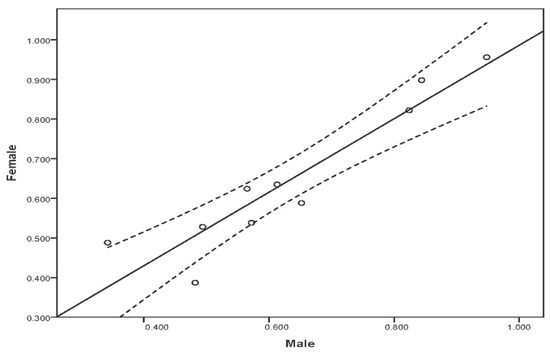

The existence of a linear correlation between Figure 5 and Figure 9 data of the RMNPI in male and female study groups was checked. Figure 12 presents the plotted regression line with the 95% confidence interval. Applying the Pearson correlation coefficient we get r = 0.93, with the 95% confidence interval, [0.74, 0.98]. Since r > 0 and 0.74 > 0, it can be concluded that exists a positive correlation; r indicates a very strong correlation (the visual interpretation of Figure 12 leads to the same conclusion). Table 1 illustrates the two indices’ values in the male and female groups.

Figure 12.

The regression line for male and female study group, applying the Navy plaque index modified by Rustogi.

Table 1.

RMNPI and TMQHPI in male and female groups.

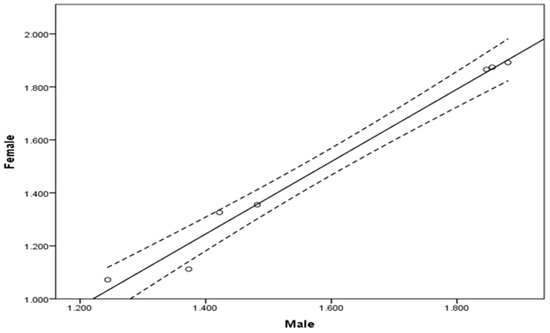

It was analyzed the existence of a linear correlation between Figure 6 and Figure 10 data of the TMQHPI in male and female study groups. Figure 13 presents the plotted regression line with the 95% confidence interval (dotted line). As a next step based on data normality it was decided for the calculus of the Pearson correlation coefficient, r = 0.99, with the 95% confidence interval, [0.94, 0.998]. As r > 0 and 0.94 > 0 it can be concluded that exists a positive correlation. r ∈ [0.9,1] indicates the existence of a very strong correlation (the visual interpretation of Figure 13 lead to the same conclusion).

Figure 13.

The regression line male and female study group, Turesky Modified Quigley–Hein Plaque Index.

33% of men declare that they wear VFRs every night, 22% once every two nights, 17% once a week, and 28% do not wear them at all; the most common reason men wear them for less time than have been indicated is that they forget (48%). 45% of women said they wear VFRs every night, 18% once every two nights, 15% once a week, and 22% do not wear them at all; the common reasons for wearing less than indicated time are: they forgot (36%), or they did not like how it (them) felt (30%).

The questionnaire’s results indicated that most damages/detachments/fractures (75%) occurred in patients with lower retainers, 10% in upper retainers, 10% in VFRs, and only 5% in HRs wearers. Regarding the VFRs wear, 33% of men confess that they wear them every night, 22% once every two nights, 17% once a week, and 28% do not wear them at all; the most common reason men wear them for less time than have been indicated is that they forget (48%). 45% of women say they wear VFRs every night, 18% once every two nights, 15% once a week, and 22% do not wear them at all; the common reasons for wearing less than indicated time are: they forgot (36%), or they did not like how it (them) felt (30%).

Patients with a history of class III have more plaque accumulation (66%), and class II/1 had the most problems related to detachment/damage of fixed retainers (20%).

4. Discussions

In our detailed study, we examined the possible effects of the most commonly used orthodontic retainers on dental hygiene and marginal periodontium. We intended to identify the least harmful way of orthodontic retention for the periodontium. The most important effect of orthodontic retainers is to favor bacterial plaque deposits that maintain a chronic inflammatory periodontal condition which leads to gradual bone loss, gingival retractions, and tooth sensitivity [32,33].

Fixed orthodontic retainers were used for cases that need a long-term and recurrent contention in an arch. They include anterior mandibular or maxillary teeth; the cementation of the retainer on teeth is with modern adhesive techniques. The purposes of fixed retention are to keep the curvature of the frontal arch and maintain the teeth in the new and correct position established by the orthodontic treatment [33].

Our results showed that in the male group, the lower fixed retainers are the most harmful for the periodontium; they favor a massive accumulation of interdental and cervical BP. The value of BP in the cervical area ABC was 0.824 out of 1, the maximum score of RMNPI; the value of BP in the interdental areas DF was even bigger (0.844) and surpassed only by the value for the same tooth zones observed in the case of using the Hawley retainer (0.948). In the same group, the lowest values of cervical and interdental BP were found in upper VFR’s wearers (0.342, respectively 0.494). Investigate comparatively the plaque indices in cervical and interdental zones for each retainer type, the biggest difference was in the Hawley retainer wearers; the reason could be that the HRs’ wire anchoring system facilitates the BP accumulation at the interdental areas whilst the cervical areas are more accessible for self-cleaning.

In the case of male patients, the subjective need for descaling and professional hygiene was the highest (77%) for those who wore fixed retentions and the lowest (10%) for the Hawley retainer wearers.

For the female group, the highest values of cervical plaque in ABC areas were determined in the case of lower fixed retainer wearers (0.822), and the lowest in the case of Hawley retainer wearers (0.387). The highest values of interdental plaque (DF) were demonstrated, similar with the male group by the Hawley retainer’s wearers (0.956) and the lowest by those with upper VFRs (0.488). Superior VFRs cause less cervical and interdental plaque accumulation in both male and female groups.

By statistical means, it was found a very strong correlation between the values of the Navy plaque index modified by Rustogi in male and female study groups.

In the case of the Quigley–Hein plaque index modified by Turesky (TMQHPI) the highest value for the male group was demonstrated by patients wearing inferior and superior fixed retainers (1.881). TMQHPI values are also high when the lower retainer is used as a single element (1.847) or in combination with the upper VFR (1.856). However, TMQHPI values demonstrate the presence of good dental hygiene at the limit. The highest value of TMQHPI in female patients was also found in those with lower fixed retainers (1.866) and combinations of this with the upper retainer (1.892) and upper VFR (1.874). By analyzing the values of this index we can even support the positive effect of VFR in combating dental plaque formation because the lowest values of the averages (1.244 in the male group and 1.072 in the female group) were demonstrated by patients with both lower and upper VFRs.

In the case of female patients, the subjective need for descaling and professional hygiene was the highest (80%) for those who wore fixed retentions and the lowest (8%) for the Hawley retainer wearers.

A very strong correlation was found between the values of the Quigley–Hein plaque index modified by Turesky (TMQHPI) in male and female study groups.

Flossing is the most commonly used auxiliary means for oral hygiene in both male and female groups (57%, respectively 62%), followed by interdental brushes (30%, respectively 35%), mouthwash (26%, respectively 28%), and water flosser (26%, respectively 19%). 9% of the male group and 2% from the female group stated that they did not use any auxiliary method of oral hygiene but only regular tooth brushing.

According to the latest studies, it would be desirable to recommend to our patients with orthodontic retainers the use of electric and sonic toothbrushes [34,35,36]. The use of both rotating-oscillating heads and sonic action heads powered toothbrushes proved to be better than manual toothbrushes in managing oral hygiene, without causing damages to periodontal structures. It is still difficult to determine which one of these has more efficacity [34]. Better long-term results were in favor of sonic toothbrushes for both the gingival and bleeding indices [34,36]. The possibility of using kinds of toothpaste for home use with hyaluronic acid, vitamins E, lactoferrin, and paraprobiotics may help the hygiene of soft tissues along the edge of the retainers [37].

Levin et al. [38] had also demonstrated that lower retainers increased plaque accumulation, gingival recession, and gingival inflammation gingival revealed by bleeding on probing. Pandis et al. [39] highlighted the negative effects of long-term fixed retention in the lower arch: periodontal irritation, marginal gingival recession, plaque accumulation. Their results were related to the long-term wearing of fixed retainers rather than the bonding materials used [40]. As in our study, Butler and Dowling [41] found large accumulations of dental plaque in interproximal areas that are more difficult to clean. Multistranded wire retainers are bonded to each tooth separately, being effective for the prevention of individual dental rotations caused by the residual tension of the periodontal ligaments that tend to return the teeth to their original position. Their great advantage is the flexibility which allows the physiological movement of the bonded teeth [39].

If the occlusion is not stable at the end of the orthodontic treatment, later changes in the position of the anterior teeth can lead to altered aesthetics of the frontal area that cause dissatisfaction for both doctor and patient. Fixed contention in the anterior frontal arch ensures the stability over time of the results of the active orthodontic treatment [39].

Our study showed that gingival recessions for 62% of male patients and 56% of female patients occur while wearing the lower fixed retainer. A study [42] performed by the “Third National Health, Nutrition Examination Survey” found similar results: men had higher gingival recessions and much more tartar accumulation compared to women, mainly due to a much larger size of their teeth [43]. The lowest values of gingival recessions in both male and female groups were in patients wearing Hawley retainers (3% for males and 5% for women). There are still many studies that contradict the opinion that long-term fixed retainers cause gingival retractions and periodontal damages [6,12,44].

Other issues are related to damage/detachment/fracture in orthodontic retainers. These accidents make the periodontal tissue reorganize to the status before wearing the orthodontic appliance, with harmful effects on periodontium: gingival recessions, bone resorptions, etc. We found that most damages/detachments/fractures (75%) occurred in patients with fixed lower retainers and only 5% in HRs wearers. A similar study showed that these accidents lead to additional costs for the patients; the authors proposed that all the responsibility for retention should be transferred to the patient by applying a mobile retention device, or that the fixed retainers should be removed after a few years [45].

Al-Nimri et al. [6] demonstrated that multistranded wire retainers fractured more frequently than the round wire retainers, even if the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.352). The same authors also concluded that using multistrand wire retainer, the distal surfaces of the lower anterior teeth have more plaque accumulations than using round wire retainers, even if they were more efficient for incisor alignment. The reasons for the failure of fixed retainers are separations between the wire and the bonding material used or between the tooth’s enamel and the bonding material [12], the wire’s breakage, or the inadvertent tooth movement with fixed lingual retainers [46].

Moshkelgosha et al. [47] demonstrated that polyethylene VFRs are not indicated in clinical situations when greater wear resistance is needed; in such conditions, it is better to use polymethyl-methacrylate-based devices like Hawley retainers that are more resistant to wear and breakage. Their results support the results of our study.

The patient’s non-compliance in case of VFRs will also lead to unfavorable consequences for the periodontium, relapse of orthodontic treatments. Only a third of men declare that they wear them every night, and the common reason men wear them lesser is that they forget. Women, on the other hand, seem to have a greater sense of responsibility, almost a half say they wear VFRs every night, and the common reasons for wearing less are they forgot or did not like how it (them) felt.

Pratt et al. [48] found in a comparative study between VRFs and HRs better compliance with VFRs for the first two years after debonding. Compliance with VFRs decreased much faster than with HRs; at any time longer than two years after debonding, the patient’s compliance was greater with HRs, and overall compliance was better with Hawley retainers. These results discourage orthodontists who recommend VFRs instead of Hawley retainers. The preference to recommend VRFs for esthetic reasons was not justified because most patients were not concerned about the esthetic aspect of the retainer, or even if so, the perceptions of VFRs and HRs were equal [48].

In another study, Almuqbil and Banabilh found that 15% of patients with VFRs who did not comply reported the loss of the retainers. For those who did not comply with mobile retainers, the majority said it affected their eating (84.3%), speech (56.9%), comfort (47.1%), and breath odor (43.1%) [49]. The compliance decreased with increasing the time since the fixed orthodontic appliance was de-bonded [49]. The participants were more compliant with HRs than with VFRs. However, VFRs provide better relapse prevention of incisor irregularity than HRs in both arches so, they are more useful in orthodontic practice [50].

The results proved strong correlations between male and female groups regarding the two investigated plaque indices. Another study comparatively investigates the prevalence of dental plaque in adults by using the TMQHPI and Löe–Silness gingivitis index found no significant differences for dental plaque and gingivitis scores irrespective of gender [51]. Our results are different from other findings of a review article published in 2021 that concluded men are more likely to ignore oral health, have poorer oral hygiene habits than women, and have higher rates of periodontal disease [52]. Women demonstrate better oral health behaviors than men. Men and women disproportionately develop periodontal diseases because of biological and gender-related reasons that include immune system factors, hormone differences, and poorer oral hygiene habits of men [52].

According to the initial orthodontic anomaly, those with a history of class III have more plaque accumulation, and class II/1 had the most problems related to detachment/damage of fixed retainers.

Comparing the two types of orthodontic retainers, both mobile and fixed ones have advantages and disadvantages. The great advantage of fixed retainers is that being bonded, the patient wears them; the weak spot is that the accumulation of dental plaque is much more than in mobile retainers. The vacuum-formed retainers used together have the lowest plaque index score of all retention devices, but the main disadvantage is the non-compliance of patients who forget to wear them.

The present study contributes to the increase in reference data in the literature, supporting future research in this field. The limitation of our study is the small number of subjects due to pandemic conditions that restricted the clinic activity because of the high infection rate with the COVID-19 virus.

5. Conclusions

Plaque accumulation was more, and gingival recessions occurred most often in the case of patients wearing fixed inferior retainers. Oral hygiene of the group with fixed orthodontic retainers was compromised, while the hygiene of the group with mobile orthodontic retainers was better. Investigated plaque indices showed a higher score in the case of fixed retainers. Usage of the Hawley plate resulted in the highest accumulation of interdental plaque of all studied retainers. Mobile retainers are superior for maintaining oral hygiene, but the benefits of fixed retainers are not to be ignored.

Flossing was the most commonly used auxiliary means for oral hygiene. Compliance of women in wearing vacuum-formed retainers is better than that of men. Patients with a class III history had more plaque accumulation, and class II/1 had the most problems related to detachment/damage of fixed retainers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.M.B. and A.V.; methodology, S.M.B., A.B. and E.S.B.; software, L.B.I. and D.I.C.; validation, S.M.B. and A.V.; formal analysis, L.B.I.; investigation, S.M.B., E.S.B. and D.I.C.; resources, A.B.; data curation, L.B.I.; writing—original draft preparation, A.B.; writing—review and editing, E.S.B.; visualization, S.M.B. and L.B.I.; supervision, S.M.B. and A.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of SC Algocalm SRL, Târgu-Mures, Romania, 899/1 February 2021.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting reported results can be found by contacting Anamaria Bud, anamaria.bud@umfst.ro.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest regarding this manuscript.

Appendix A

Name Age Sex

- 1.

- What kind of retainer do you have?

- A.

- Hawley retainer

- B.

- Fixed retainer

- C.

- VFR

- 2.

- How long have you had the retainer?

- 3.

- Have you had any dental scaling while wearing the retainer?

- 4.

- If yes, specify the number of scalings performed:

- 5.

- What auxiliary means of oral hygiene do you use?

- A.

- Dental floss

- B.

- Mouthwash

- C.

- Water irrigator

- D.

- Interdental brushes

- 6.

- Have you noticed a greater accumulation of dental plaque after applying the retainer?

- A.

- Yes

- B.

- No

- 7.

- Does the retainer make you brush/clean your teeth more often than you usually do?

- A.

- Yes

- B.

- No

- 8.

- How much time do you spend cleaning, brushing the area where the retainer is applied?

- A.

- As much as for the other dental areas

- B.

- 1–2 min more because it is a food retention area

- 9.

- Have you had problems since you wear your retainer?

- A.

- No.

- B.

- Yes, the retainer came off my teeth

- C.

- Yes, it has deteriorated/fractured

- D.

- Yes, it was not effective, the teeth returned partially/totally to the initial position

- 10.

- How often do you wear the retainer(s) at night?

- A.

- Never: if so, how long have you given up wearing them? ...............

- B.

- Once a month

- C.

- Once a week

- D.

- Every night

- E.

- Every two nights

- F.

- Another answer ....................

- 11.

- If you do not wear the retainer(s) as often as you have been trained, which is the reason?

- A.

- I don’t like the way it looks (they look)

- B.

- I don’t like how it feels (they feel)

- C.

- I forgot to wear it/them

- D.

- It’s (there are) a headache, a waste of time

- E.

- I lost it/them

- F.

- Retainer(s) no longer fit

- G.

- It affects (they affect) my speech

- H.

- Another answer ...............

References

- Nazir, M.A. Prevalence of periodontal disease, its association with systemic diseases and prevention. Int. J. Health Sci. 2017, 11, 72–80. [Google Scholar]

- Raitapuro-Murray, T.; Molleson, T.I.; Hughes, F.J. The prevalence of periodontal disease in a Romano-British population c. 200–400 AD. Br. Dent. J. 2014, 217, 459–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Locker, D.; Slade, G.D.; Murray, H. Epidemiology of periodontal disease among older adults: A review. Periodontology 1998, 16, 16–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Könönen, E.; Gursoy, M.; Gursoy, U.K. Periodontitis: A Multifaceted Disease of Tooth-Supporting Tissues. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibertoni, F.; Sommer, M.E.L.; Esquisatto, M.A.M.; Amaral, M.E.C.D.; Oliveira, C.A.; Andrade, T.A.M.; Mendonça, F.A.S.; Santamaria, M., Jr.; Felonato, M. Evolution of Periodontal Disease: Immune Response and RANK/RANKL/OPG System. Braz. Dent. J. 2017, 28, 679–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Nimri, K.; Al Habashneh, R.; Obeidat, M. Gingival health and relapse tendency: A prospective study of two types of lower fixed retainers. Aust. Orthod. J. 2009, 25, 142–146. [Google Scholar]

- Artun, J.; Spadafora, A.T.; Shapiro, P.A. A 3-year follow-up study of various types of orthodontic canine-to-canine retainers. Eur. J. Orthod. 1997, 19, 501–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartal, Y.; Kaya, B. Fixed Orthodontic Retainers: A Review. Turk. J. Orthod. 2019, 32, 110–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, K.; Parida, S.; Mangwani, N.; Dash, H.R.; Das, S. Isolation and characterization of biofilm-forming bacteria and associated extracellular polymeric substances from oral cavity. Ann. Microbiol. 2013, 63, 1553–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirajuddin, S.; Narasappa, K.M.; Gundapaneni, V.; Chungkham, S.; Walikar, A.S. Iatrogenic Damage to Periodontium by Restorative Treatment Procedures: An Overview. Open Dent. J. 2015, 9, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talic, N.F. Adverse effects of orthodontic treatment: A clinical perspective. Saudi Dent. J. 2011, 23, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bucur, S.M.; Chiarati, C.R.; Avino, P.; Migliorino, I.; Kartal, Y.; Cocoș, D.I.; Bud, E.S.; Bud, A.; Vlasa, A. Retrospective study regarding the status of the superficial marginal periodontium in adult patients wearing orthodontic retainers. Rom. J. Oral Rehabil. 2021, 13, 194–201. [Google Scholar]

- Hănțoiu, T.; Monea, A.; Lazăr, L.; Hănțoiu, L. Clinical evaluation of periodontal health during orthodontic treatment with fixed appliances. Acta Med. Marisiensis 2015, 60, 265–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mlinek, A.; Smukler, H.; Buchner, A. The use of free gingival grafts for the coverage of denuded roots. J. Periodontol. 1974, 44, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riedel, R.A. A review of the retention problem. Angle Orthod. 1960, 30, 179–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alassiry, A.M. Orthodontic Retainers: A Contemporary Overview. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2019, 20, 857–862. [Google Scholar]

- Mai, W.; He, J.; Meng, H.; Jiang, Y.; Huang, C.; Li, M.; Yuan, K.; Kang, N. Comparison of vacuum-formed and Hawley retainers: A systematic review. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2014, 145, 720–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Yu, Y.C.; Liu, M.Y.; Chen, L.; Li, H.W.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, Y.; Ao, D.; Tao, R.; Lai, W.L. Survival time comparison between Hawley and clear overlay retainers: A randomized trial. J. Dent. Res. 2011, 90, 1197–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalha, A.S. Hawley or vacuum-formed retainers following orthodontic treatment? Evid. Based Dent. 2014, 15, 110–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaida, L.L.; Bud, E.S.; Halitchi, L.G.; Cavalu, S.; Todor, B.I.; Negrutiu, B.M.; Moca, A.E.; Bodog, F.D. The Behavior of Two Types of Upper Removable Retainers-Our Clinical Experience. Children 2020, 7, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rustogi, K.N.; Curtis, J.P.; Volpe, A.R.; Kemp, J.H.; McCool, J.J.; Korn, L.R. Refinement of the Modified Navy Plaque Index to increase plaque scoring efficiency in gumline and interproximal tooth areas. J. Clin. Dent. 1992, 3 (Suppl. C), C9–C12. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Deinzer, R.; Jahns, S.; Harnacke, D. Establishment of a new marginal plaque index with high sensitivity for changes in oral hygiene. J. Periodontol. 2014, 85, 1730–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasileiou, K.; Barnett, J.; Thorpe, S.; Young, T. Characterizing and justifying sample size sufficiency in interview-based studies: Systematic analysis of qualitative health research over a 15-year period. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krejcie, R.V.; Morgan, D.W. Determining Sample Size for Research Activities. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1970, 30, 607–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smeden, M.; Moons, K.G.M.; Groot, J.A.H.; Collins, G.S.; Altman, D.G.; Eijkemans, M.J.C.; Reitsma, J.B. Sample size for binary logistic prediction models: Beyond events per variable criteria. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 2019, 28, 2455–2474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iantovics, L.B.; Rotar, C.; Morar, F. Survey on establishing the optimal number of factors in exploratory factor analysis applied to data mining. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 2019, 9, e1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, S.S.; Wilk, M.B. An analysis of variance test for normality (complete samples). Biometrika 1965, 52, 591–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razali, N.; Wah, Y.B. Power comparisons of Shapiro-Wilk, Kolmogorov-Smirnov, Lilliefors and Anderson-Darling tests. J. Stat. Model. Anal. 2011, 2, 21–33. [Google Scholar]

- Makkonen, L. Bringing closure to the plotting position controversy. Commun. Stat.–Theory Methods 2008, 37, 460–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, V.; Lewis, T. Outliers in Statistical Data, 3rd ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Stigler, S.M. Francis Galton’s Account of the Invention of Correlation. Stat. Sci. 1989, 4, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jati, A.S.; Furquim, L.Z.; Consolaro, A. Gingival recession: Its causes and types, and the importance of orthodontic treatment. Dental Press J. Orthod. 2016, 21, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juloski, J.; Glisic, B.; Vandevska-Radunovic, V. Long-term influence of fixed lingual retainers on the development of gingival recession: A retrospective, longitudinal cohort study. Angle Orthod. 2017, 87, 658–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preda, C.; Butera, A.; Pelle, S.; Pautasso, E.; Chiesa, A.; Esposito, F.; Oldoini, G.; Scribante, A.; Genovesi, A.M.; Cosola, S. The Efficacy of Powered Oscillating Heads vs. Powered Sonic Action Heads Toothbrushes to Maintain Periodontal and Peri-Implant Health: A Narrative Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petker, W.; Weik, U.; Margraf-Stiksrud, J.; Deinzer, R. Oral cleanliness in daily users of powered vs. manual toothbrushes—A cross-sectional study. BMC Oral. Health 2019, 19, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Digel, I.; Kern, I.; Geenen, E.M.; Akimbekov, N. Dental Plaque Removal by Ultrasonic Toothbrushes. Dent. J. 2020, 8, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butera, A.; Gallo, S.; Maiorani, C.; Preda, C.; Chiesa, A.; Esposito, F.; Pascadopoli, M.; Scribante, A. Management of Gingival Bleeding in Periodontal Patients with Domiciliary Use of Toothpastes Containing Hyaluronic Acid, Lactoferrin, or Paraprobiotics: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 8586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, L.; Samorodnitzky-Naveh, G.R.; Machtei, E.E. The association of orthodontic treatment and fixed retainers with gingival health. J. Periodontol. 2008, 79, 2087–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandis, N.; Vlahopoulos, K.; Madianos, P.; Eliades, T. Long-term periodontal status of patients with mandibular lingual fixed retention. Eur. J. Orthod. 2007, 29, 471–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artun, J.; Zachrisson, B. Improving the handling properties of a composite resin for direct bonding. Am. J. Orthod. 1982, 81, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, J.; Dowling, P. Orthodontic bonded retainers. J. Ir. Dent. Assoc. 2005, 51, 29–32. [Google Scholar]

- Albandar, J.M.; Kingman, A. Gingival recession, gingival bleeding, and dental calculus in adults 30 years of age and older in the United States, 1988–1994. J. Periodontol. 1999, 70, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, S.J. Range and mean distribution frequency of individual tooth width of the maxillary anterior dentition. Pract. Proced. Aesthet. Dent. 2007, 19, 209–215. [Google Scholar]

- Booth, F.A.; Edelman, J.M.; Proffit, W.R. Twenty-year follow-up of patients with permanently bonded mandibular canine-to-canine retainers. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2008, 133, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerlund, A.; Daxberg, E.L.; Liljegren, A.; Oikonomou, C.; Ransjö, M.; Samuelsson, O.; Sjögren, P. Stability and Side Effects of Orthodontic Retainers—A Systematic Review. Dentistry 2014, 4, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaughnessy, T.G.; Proffit, W.R.; Samara, S.A. Inadvertent tooth movement with fixed lingual retainers. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2016, 149, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshkelgosha, V.; Shomali, M.; Momeni, M. Comparison of Wear Resistance of Hawley and Vacuum Formed Retainers: An in-vitro Study. J. Dent. Biomater. 2016, 3, 248–253. [Google Scholar]

- Pratt, M.C.; Kluemper, T.; Lindstrom, A.F. Patient compliance with orthodontic retainers in the postretention phase. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2011, 140, 196–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almuqbil, S.; Banabilh, S. Postretention phase: Patients’ compliance and reasons for noncompliance with removable retainers. Int. J. Orthod. Rehabil. 2019, 10, 18–22. [Google Scholar]

- Outhaisavanh, S.; Liu, Y.; Song, J. The origin and evolution of the Hawley retainer for the effectiveness to maintain tooth position after fixed orthodontic treatment compare to vacuum-formed retainer: A systematic review of RCTs. Int. Orthod. 2020, 18, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Handelman, C.S.; Eltink, A.P.; BeGole, E. Quantitative measures of gingival recession and the influence of gender, race, and attrition. Prog. Orthod. 2018, 19, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipsky, M.S.; Su, S.; Crespo, C.J.; Hung, M. Men and Oral Health: A Review of Sex and Gender Differences. Am. J. Mens. Health 2021, 15, 15579883211016361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).