A Review on Recent Advancements of Graphene and Graphene-Related Materials in Biological Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

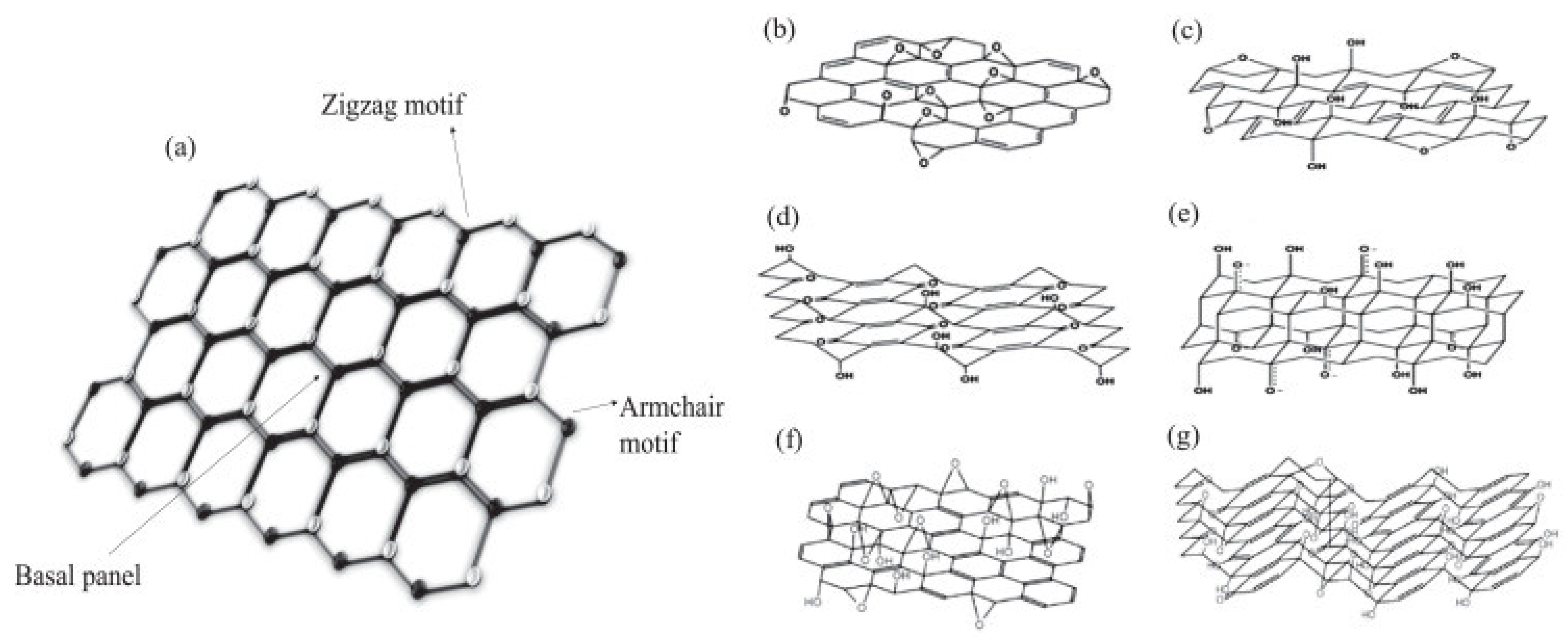

2. Graphene and Graphene-Related Materials

2.1. Overview on Graphene and Related Materials

2.2. Graphene and Related Materials, Characterization

2.2.1. Spectroscopical Techniques

2.2.2. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

2.2.3. Advanced Microscopic Techniques

2.2.4. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

3. Graphene and Graphene-Related Materials for Biological Applications

3.1. Interaction between Graphene and Related Materials and Biological Systems

3.2. Graphene and Related Materials as Drug Delivery Platforms

3.3. Graphene and Related Materials as Tool for Regenerative Medicine and Tissue Repair

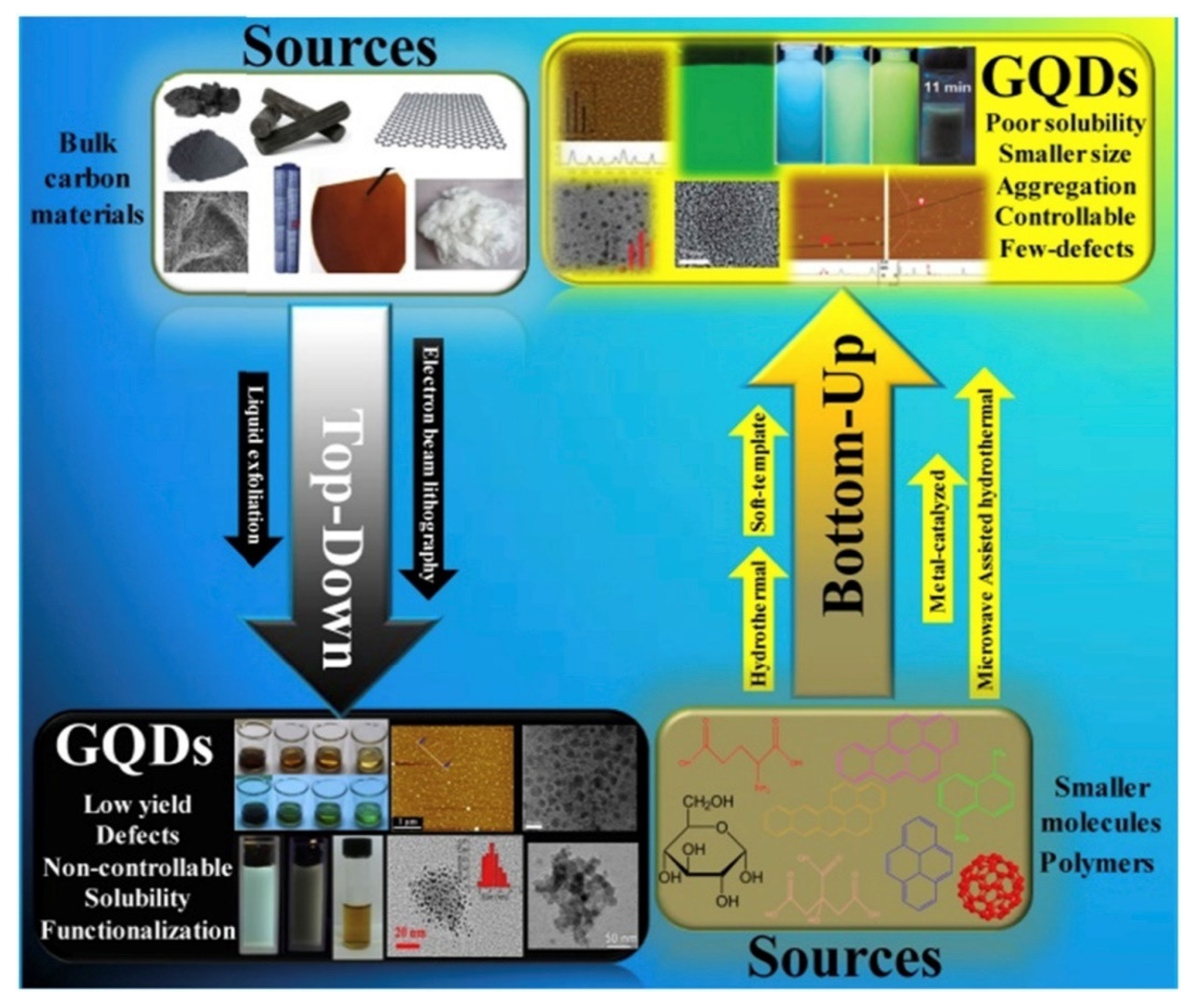

3.4. From Material to Supramolecular Cluster: Graphene Quantum Dots

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Emerich, D.F.; Thanos, C.G. Nanotechnology and medicine. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2003, 3, 655–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, S.-N.; Xie, N.; Feng, L.-C.; Zhong, J. Applications of nanostructured carbon materials in constructions: The state of the art. J. Nanomater. 2015, 2015, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candelaria, S.L.; Shao, Y.; Zhou, W.; Li, X.; Xiao, J.; Zhang, J.-G.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Li, J.; Cao, G. Nanostructured carbon for energy storage and conversion. Nano Energy 2012, 1, 195–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.J.; Weinberg, G.; Liu, X.; Timpe, O.; Schlögl, R.; Su, D.S. Nanoarchitecturing of activated carbon: Facile strategy for chemical functionalization of the surface of activated carbon. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2008, 18, 3613–3619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, D.; Kivioja, J. Graphene for energy solutions and its industrialization. Nanoscale 2013, 5, 10108–10126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graphene Flagship. Available online: https://graphene-flagship.eu/ (accessed on 17 December 2020).

- Yang, G.; Li, L.; Lee, W.B.; Ng, M.C. Structure of graphene and its disorders: A review. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2018, 19, 613–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Cui, L.; Liu, J. Review of functionalization, structure and properties of graphene/polymer composite fibers. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2016, 87, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorcelli, M.; Bartoli, M. Carbon Nanostructures for Actuators: An Overview of Recent Developments. Actuators 2019, 8, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavagna, L.; Massella, D.; Priola, E.; Pavese, M. Relationship between oxygen content of graphene and mechanical properties of cement-based composites. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2021, 115, 103851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavagna, L.; Marchisio, S.; Merlo, A.; Nisticò, R.; Pavese, M. Polyvinyl butyral-based composites with carbon nanotubes: Efficient dispersion as a key to high mechanical properties. Polym. Compos. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Sharma, K.; Dixit, A.R. A review of the mechanical and thermal properties of graphene and its hybrid polymer nanocomposites for structural applications. J. Mater. Sci. 2019, 54, 5992–6026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadkhah, M.; Saboori, A.; Fino, P. An overview of the recent developments in metal matrix nanocomposites reinforced by graphene. Materials 2019, 12, 2823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hidalgo-Manrique, P.; Lei, X.; Xu, R.; Zhou, M.; Kinloch, I.A.; Young, R.J. Copper/graphene composites: A review. J. Mater. Sci. 2019, 54, 12236–12289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartoli, M.; Giorcelli, M.; Jagdale, P.; Rovere, M.; Tagliaferro, A. A Review of Non-Soil Biochar Applications. Materials 2020, 13, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strongone, V.; Bartoli, M.; Jagdale, P.; Arrigo, R.; Tagliaferro, A.; Malucelli, G. Preparation and Characterization of UV-LED Curable Acrylic Films Containing Biochar and/or Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes: Effect of the Filler Loading on the Rheological, Thermal and Optical Properties. Polymers 2020, 12, 796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savi, P.; Yasir, M.; Bartoli, M.; Giorcelli, M.; Longo, M. Electrical and Microwave Characterization of Thermal Annealed Sewage Sludge Derived Biochar Composites. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noori, A.; Bartoli, M.; Frache, A.; Piatti, E.; Giorcelli, M.; Tagliaferro, A. Development of Pressure-Responsive PolyPropylene and Biochar-Based Materials. Micromachines 2020, 11, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbalini, M.; Bartoli, M.; Tagliaferro, A.; Malucelli, G. Phytic Acid and Biochar: An Effective All Bio-Sourced Flame Retardant Formulation for Cotton Fabrics. Polymers 2020, 12, 811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrigo, R.; Bartoli, M.; Malucelli, G. Poly (lactic Acid)–Biochar Biocomposites: Effect of Processing and Filler Content on Rheological, Thermal, and Mechanical Properties. Polymers 2020, 12, 892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorcelli, M.; Bartoli, M. Development of Coffee Biochar Filler for the Production of Electrical Conductive Reinforced Plastic. Polymers 2019, 11, 1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartoli, M.; Giorcelli, M.; Rosso, C.; Rovere, M.; Jagdale, P.; Tagliaferro, A. Influence of Commercial Biochar Fillers on Brittleness/Ductility of Epoxy Resin Composites. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 3109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrigo, R.; Jagdale, P.; Bartoli, M.; Tagliaferro, A.; Malucelli, G. Structure–Property Relationships in Polyethylene-Based Composites Filled with Biochar Derived from Waste Coffee Grounds. Polymers 2019, 11, 1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Priyadarsini, S.; Mohanty, S.; Mukherjee, S.; Basu, S.; Mishra, M. Graphene and graphene oxide as nanomaterials for medicine and biology application. J. Nanostruct. Chem. 2018, 8, 123–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leachman, S.A.; Merlino, G. Medicine: The final frontier in cancer diagnosis. Nature 2017, 542, 36–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wender, P.A.; Miller, B.L. Synthesis at the molecular frontier. Nature 2009, 460, 197–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartoli, M.; Jagdale, P.; Tagliaferro, A. A Short Review on Biomedical Applications of Nanostructured Bismuth Oxide and Related Nanomaterials. Materials 2020, 13, 5234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivorra, M.; Paya, M.; Villar, A. A review of natural products and plants as potential antidiabetic drugs. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1989, 27, 243–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, H.; Abribat, T. The rise and rise of drug delivery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2005, 4, 381–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeWitt, N. Regenerative medicine. Nature 2008, 453, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarrintaj, P.; Mostafapoor, F.; Milan, P.B.; Saeb, M.R. Theranostic platforms proposed for cancerous stem cells: A review. Curr. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2019, 14, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Place, E.S.; Evans, N.D.; Stevens, M.M. Complexity in biomaterials for tissue engineering. Nat. Mater. 2009, 8, 457–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aminov, R.I. The role of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance in nature. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 11, 2970–2988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mintmire, J.W.; Dunlap, B.I.; White, C.T. Are fullerene tubules metallic? Phys. Rev. Lett. 1992, 68, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, J.-A.; Ruan, W.; Chou, M. Electron-phonon interactions for optical-phonon modes in few-layer graphene: First-principles calculations. Phys. Rev. B 2009, 79, 115443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dresselhaus, M.; Jorio, A.; Saito, R. Characterizing graphene, graphite, and carbon nanotubes by Raman spectroscopy. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 2010, 1, 89–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, K.Y. Electronic and Thermal Properties of Graphene. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.C.; Liu, W.-W.; Chai, S.-P.; Mohamed, A.R.; Lai, C.W.; Khe, C.-S.; Voon, C.; Hashim, U.; Hidayah, N. Synthesis of single-layer graphene: A review of recent development. Procedia Chem. 2016, 19, 916–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narita, A.; Wang, X.-Y.; Feng, X.; Müllen, K. New advances in nanographene chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 6616–6643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Fang, S.; Hu, Y.H. 3D Graphene Materials: From Understanding to Design and Synthesis Control. Chem. Rev. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brisebois, P.; Siaj, M. Harvesting graphene oxide–years 1859 to 2019: A review of its structure, synthesis, properties and exfoliation. J. Mater. Chem. C 2020, 8, 1517–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodie, B.C. XIII. On the atomic weight of graphite. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. 1859, 149, 249–259. [Google Scholar]

- Staudenmaier, L. Verfahren zur darstellung der graphitsäure. Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges. 1898, 31, 1481–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- William, S.; Hummers, J.; Offeman, R.E. Preparation of graphitic oxide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1958, 80, 1339. [Google Scholar]

- Poh, H.L.; Šaněk, F.; Ambrosi, A.; Zhao, G.; Sofer, Z.; Pumera, M. Graphenes prepared by Staudenmaier, Hofmann and Hummers methods with consequent thermal exfoliation exhibit very different electrochemical properties. Nanoscale 2012, 4, 3515–3522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araújo, M.P.; Soares, O.; Fernandes, A.; Pereira, M.; Freire, C. Tuning the surface chemistry of graphene flakes: New strategies for selective oxidation. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 14290–14301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabó, T.; Berkesi, O.; Forgó, P.; Josepovits, K.; Sanakis, Y.; Petridis, D.; Dékány, I. Evolution of surface functional groups in a series of progressively oxidized graphite oxides. Chem. Mater. 2006, 18, 2740–2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavagna, L.; Meligrana, G.; Gerbaldi, C.; Tagliaferro, A.; Bartoli, M. Graphene and Lithium-Based Battery Electrodes: A Review of Recent Literature. Energies 2020, 13, 4867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerf, A.; He, H.; Riedl, T.; Forster, M.; Klinowski, J. 13C and 1H MAS NMR studies of graphite oxide and its chemically modified derivatives. Solid State Ion. 1997, 101, 857–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, S.; Karak, N. Alternative methods and nature-based reagents for the reduction of graphene oxide: A review. Carbon 2015, 94, 224–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guex, L.G.; Sacchi, B.; Peuvot, K.F.; Andersson, R.L.; Pourrahimi, A.M.; Ström, V.; Farris, S.; Olsson, R.T. Experimental review: Chemical reduction of graphene oxide (GO) to reduced graphene oxide (rGO) by aqueous chemistry. Nanoscale 2017, 9, 9562–9571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Tian, J.; Wang, L.; Sun, X. A method for the production of reduced graphene oxide using benzylamine as a reducing and stabilizing agent and its subsequent decoration with Ag nanoparticles for enzymeless hydrogen peroxide detection. Carbon 2011, 49, 3158–3164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, X.J.; Hiew, B.Y.Z.; Lai, K.C.; Lee, L.Y.; Gan, S.; Thangalazhy-Gopakumar, S.; Rigby, S. Review on graphene and its derivatives: Synthesis methods and potential industrial implementation. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2019, 98, 163–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, R.; Gómez-Aleixandre, C. Review of CVD synthesis of graphene. Chem. Vap. Depos. 2013, 19, 297–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khurana, G.; Misra, P.; Katiyar, R.S. Multilevel resistive memory switching in graphene sandwiched organic polymer heterostructure. Carbon 2014, 76, 341–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Li, D.; Fu, Q.; Pan, C. Conductive enhancement of copper/graphene composites based on high-quality graphene. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 80428–80433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Kim, H.; Hwang, S.; Choi, W.; Jeon, M. Dye-sensitized solar cells using graphene-based carbon nano composite as counter electrode. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2011, 95, 323–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Jing, H.W.; Chen, S.J.; Du, M.R.; Chen, W.Q.; Duan, W.H. Influence of ultrasonication on the dispersion and enhancing effect of graphene oxide–carbon nanotube hybrid nanoreinforcement in cementitious composite. Compos. Part B Eng. 2019, 164, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, B.; Xu, Q.; Hou, Y.; Seyedin, S.; Qin, S.; Wallace, G.G.; Beirne, S.; Razal, J.M.; Chen, J. Development of graphene oxide/polyaniline inks for high performance flexible microsupercapacitors via extrusion printing. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 28, 1706592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.N.; Keshavamurthy, R.; Haseebuddin, M.; Koppad, P.G. Mechanical properties of aluminium-graphene composite synthesized by powder metallurgy and hot extrusion. Trans. Indian Inst. Met. 2017, 70, 605–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melanitis, N.; Tetlow, P.L.; Galiotis, C. Characterization of PAN-based carbon fibres with laser Raman spectroscopy. J. Mater. Sci. 1996, 31, 851–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, F. Raman spectrum of graphite. J. Chem. Phys. 1970, 53, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Shukla, S.; Saxena, S. Spectroscopic investigation of confinement effects on optical properties of graphene oxide. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2011, 98, 073104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Yan, Z.; Yao, J.; Beitler, E.; Zhu, Y.; Tour, J.M. Growth of graphene from solid carbon sources. Nature 2010, 468, 549–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Wang, X.; Fang, D. A review on C1s XPS-spectra for some kinds of carbon materials. Fuller. Nanotub. Carbon Nanostruct. 2020, 28, 1048–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrengo, S.; Canteri, R.; Dell’Anna, R.; Minati, L.; Pasquarelli, A.; Speranza, G. XPS and ToF-SIMS investigation of nanocrystalline diamond oxidized surfaces. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2013, 276, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Tamijani, A.A.; Taylor, M.E.; Zhi, B.; Haynes, C.L.; Mason, S.E.; Hamers, R.J. Molecular Surface Functionalization of Carbon Materials via Radical-Induced Grafting of Terminal Alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 8277–8288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathnayake, R.M.N.M.; Wijayasinghe, H.W.M.A.C.; Pitawala, H.M.T.G.A.; Yoshimura, M.; Huang, H.-H. Synthesis of graphene oxide and reduced graphene oxide by needle platy natural vein graphite. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 393, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinský, P.; Macková, A.; Mikšová, R.; Kováčiková, H.; Cutroneo, M.; Luxa, J.; Bouša, D.; Štrochová, B.; Sofer, Z. Graphene oxide layers modified by light energetic ions. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 10282–10291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, A.J.; Wilson, N.R.; Kinloch, I.A.; Dryfe, R.A.W. Single stage electrochemical exfoliation method for the production of few-layer graphene via intercalation of tetraalkylammonium cations. Carbon 2014, 66, 340–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.-B.; Zheng, W.-G.; Yan, Q.; Yang, Y.; Wang, J.-W.; Lu, Z.-H.; Ji, G.-Y.; Yu, Z.-Z. Electrically conductive polyethylene terephthalate/graphene nanocomposites prepared by melt compounding. Polymer 2010, 51, 1191–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Müller, M.B.; Gilje, S.; Kaner, R.B.; Wallace, G.G. Processable aqueous dispersions of graphene nanosheets. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2008, 3, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.; Wei, X.; Kysar, J.W.; Hone, J. Measurement of the Elastic Properties and Intrinsic Strength of Monolayer Graphene. Science 2008, 321, 385–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, K.W.; Tam, H.-Y. TEM Morphology of Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) and its Effect on the Life of Micropunch. Transm. Electron Microsc. Theory Appl. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Suenaga, K.; Harris, P.J.; Iijima, S. Open and closed edges of graphene layers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009, 102, 015501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coats, A.; Redfern, J. Thermogravimetric analysis. A review. Analyst 1963, 88, 906–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavagna, L.; Musso, S.; Pavese, M. A facile method to oxidize carbon nanotubes in controlled flow of oxygen at 350 °C. Mater. Lett. 2021, 283, 128816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leenaerts, O.; Partoens, B.; Peeters, F. Water on graphene: Hydrophobicity and dipole moment using density functional theory. Phys. Rev. B 2009, 79, 235440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullick Chowdhury, S.; Lalwani, G.; Zhang, K.; Yang, J.Y.; Neville, K.; Sitharaman, B. Cell specific cytotoxicity and uptake of graphene nanoribbons. Biomaterials 2013, 34, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, Q.; Su, G.; Li, L.; Gilbertson, B.O.; Yu, L.H.; Zhang, Q.; Sun, Y.-P.; Yan, B. Size-Dependent Cell Uptake of Protein-Coated Graphene Oxide Nanosheets. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2012, 4, 2259–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Wu, Z.; Li, N.; Pu, Y.; Wang, B.; Zhang, T.; Tao, J. Advanced review of graphene-based nanomaterials in drug delivery systems: Synthesis, modification, toxicity and application. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2017, 77, 1363–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherian, R.; Ashtami, J.; Mohanan, P. Effect of surface modified reduced graphene oxide nanoparticles on cerebellar granule neurons. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2020, 58, 101706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, R.; Zhou, H.; Dang, W.; Long, Y.; Tong, C.; Xie, Q.; Daniyal, M.; Liu, B.; Wang, W. A DNAzyme-rGO coupled fluorescence assay for T4PNK activity in vitro and intracellular imaging. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2020, 310, 127884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Feng, L.; Liu, Z. Stimuli responsive drug delivery systems based on nano-graphene for cancer therapy. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2016, 105, 228–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Depan, D.; Shah, J.; Misra, R. Controlled release of drug from folate-decorated and graphene mediated drug delivery system: Synthesis, loading efficiency, and drug release response. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2011, 31, 1305–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, T.; Tsuchida, K. Recent advances in inorganic nanoparticle-based drug delivery systems. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2008, 8, 175. [Google Scholar]

- Suggs, K.; Reuven, D.; Wang, X.-Q. Electronic properties of cycloaddition-functionalized graphene. J. Phys. Chem. C 2011, 115, 3313–3317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintana, M.; Spyrou, K.; Grzelczak, M.; Browne, W.R.; Rudolf, P.; Prato, M. Functionalization of graphene via 1, 3-dipolar cycloaddition. ACS Nano 2010, 4, 3527–3533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strom, T.A.; Dillon, E.P.; Hamilton, C.E.; Barron, A.R. Nitrene addition to exfoliated graphene: A one-step route to highly functionalized graphene. Chem. Commun. 2010, 46, 4097–4099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, A.E.R.; VanáTendeloo, G. Selective organic functionalization of graphene bulk or graphene edges. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 9330–9332. [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari, G.; Tiwari, R.; Sriwastawa, B.; Bhati, L.; Pandey, S.; Pandey, P.; Bannerjee, S.K. Drug delivery systems: An updated review. Int. J. Pharm. Investig. 2012, 2, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, C.; Guo, S.; Zhang, J. Interactions of graphene and graphene oxide with proteins and peptides. Nanotechnol. Rev. 2013, 2, 27–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, C. Self-assembly of graphene sheets actuated by surface topological defects: Toward the fabrication of novel nanostructures and drug delivery devices. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 505, 144008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, M.H.; Hanoon, F.H. Theoretical prediction of delivery and adsorption of various anticancer drugs into pristine and metal-doped graphene nanosheet. Chin. J. Phys. 2020, 68, 578–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauri, E.; Salvati, A.; Cataldo, A.; Mozetic, P.; Basoli, F.; Abbruzzese, F.; Trombetta, M.; Bellucci, S.; Rainer, A. Graphene-laden hydrogels: A strategy for thermally triggered drug delivery. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2021, 118, 111353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezzati, N.; Mahjoub, A.R.; Shokrollahi, S.; Amiri, A.; Abolhosseini Shahrnoy, A. Novel Biocompatible Amino Acids-Functionalized Three-dimensional Graphene Foams: As the Attractive and Promising Cisplatin Carriers for Sustained Release Goals. Int. J. Pharm. 2020, 589, 119857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Bary, A.S.; Tolan, D.A.; Nassar, M.Y.; Taketsugu, T.; El-Nahas, A.M. Chitosan, magnetite, silicon dioxide, and graphene oxide nanocomposites: Synthesis, characterization, efficiency as cisplatin drug delivery, and DFT calculations. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 154, 621–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trusek, A.; Kijak, E.; Granicka, L. Graphene oxide as a potential drug carrier—Chemical carrier activation, drug attachment and its enzymatic controlled release. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2020, 116, 111240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keizer, H.; Pinedo, H.; Schuurhuis, G.; Joenje, H. Doxorubicin (adriamycin): A critical review of free radical-dependent mechanisms of cytotoxicity. Pharmacol. Ther. 1990, 47, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.-W.; Li, J.; Dai, J.; Zhou, M.; Ren, H.; Zhang, L.; Hu, Q.; Kong, Z.; Liang, L. Molecular dynamics study on the adsorption and release of doxorubicin by chitosan-decorated graphene. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 248, 116809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanwal, U.; Irfan Bukhari, N.; Ovais, M.; Abass, N.; Hussain, K.; Raza, A. Advances in nano-delivery systems for doxorubicin: An updated insight. J. Drug Target. 2018, 26, 296–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayazi, H.; Akhavan, O.; Raoufi, M.; Varshochian, R.; Hosseini Motlagh, N.S.; Atyabi, F. Graphene aerogel nanoparticles for in-situ loading/pH sensitive releasing anticancer drugs. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2020, 186, 110712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anirudhan, T.S.; Chithra Sekhar, V.; Athira, V.S. Graphene oxide based functionalized chitosan polyelectrolyte nanocomposite for targeted and pH responsive drug delivery. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 150, 468–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omidi, S.; Pirhayati, M.; Kakanejadifard, A. Co-delivery of doxorubicin and curcumin by a pH-sensitive, injectable, and in situ hydrogel composed of chitosan, graphene, and cellulose nanowhisker. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 231, 115745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pourjavadi, A.; Asgari, S.; Hosseini, S.H. Graphene oxide functionalized with oxygen-rich polymers as a pH-sensitive carrier for co-delivery of hydrophobic and hydrophilic drugs. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2020, 56, 101542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alipour, N.; Namazi, H. Chelating ZnO-dopamine on the surface of graphene oxide and its application as pH-responsive and antibacterial nanohybrid delivery agent for doxorubicin. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2020, 108, 110459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sattari, S.; Tehrani, A.D.; Adeli, M.; Soleimani, K.; Rashidipour, M. Fabrication of new generation of co-delivery systems based on graphene-g-cyclodextrin/chitosan nanofiber. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 156, 1126–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Zhang, Q.X.; Wang, N.; Yang, Y.; Liu, J.; Yu, G.; Yang, X.; Xu, H.; Wang, H. A complex micellar system co-delivering curcumin with doxorubicin against cardiotoxicity and tumor growth. Int. J. Nanomed. 2018, 13, 4549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahanshahi, M.; Kowsari, E.; Haddadi-Asl, V.; Khoobi, M.; Bazri, B.; Aryafard, M.; Lee, J.H.; Kadumudi, F.B.; Talebian, S.; Kamaly, N.; et al. An innovative and eco-friendly modality for synthesis of highly fluorinated graphene by an acidic ionic liquid: Making of an efficacious vehicle for anti-cancer drug delivery. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 515, 146071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razaghi, M.; Ramazani, A.; Khoobi, M.; Mortezazadeh, T.; Aksoy, E.A.; Küçükkılınç, T.T. Highly fluorinated graphene oxide nanosheets for anticancer linoleic-curcumin conjugate delivery and T2-Weighted magnetic resonance imaging: In vitro and in vivo studies. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2020, 60, 101967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaboli, M.; Raissi, H.; Moghaddam, N.R.; Farzad, F. Probing the adsorption and release mechanisms of cytarabine anticancer drug on/from dopamine functionalized graphene oxide as a highly efficient drug delivery system. J. Mol. Liq. 2020, 301, 112458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Jia, Y.; Liu, C. Pluronic®® F127 stabilized reduced graphene oxide hydrogel for transdermal delivery of ondansetron: Ex vivo and animal studies. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2020, 195, 111259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahabi, M.; Raissi, H. Payload delivery of anticancer drug Tegafur with the assistance of graphene oxide nanosheet during biomembrane penetration: Molecular dynamics simulation survey. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 517, 146186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdoli, M.; Sadrjavadi, K.; Arkan, E.; Zangeneh, M.M.; Moradi, S.; Zangeneh, A.; Shahlaei, M.; Khaledian, S. Polyvinyl alcohol/Gum tragacanth/graphene oxide composite nanofiber for antibiotic delivery. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2020, 60, 102044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Jacobsen, J.; Larsen, S.W.; Genina, N.; Van de Weert, M.; Müllertz, A.; Nielsen, H.M.; Mu, H. Graphene oxide as a functional excipient in buccal films for delivery of clotrimazole: Effect of molecular interactions on drug release and antifungal activity in vitro. Int. J. Pharm. 2020, 589, 119811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Gan, J.; Li, R.; Duan, J.; Zhou, J.; Lv, M.; Qi, R. Controlled delivery of ketamine from reduced graphene oxide hydrogel for neuropathic pain: In vitro and in vivo studies. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2020, 60, 101964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pooresmaeil, M.; Javanbakht, S.; Behzadi Nia, S.; Namazi, H. Carboxymethyl cellulose/mesoporous magnetic graphene oxide as a safe and sustained ibuprofen delivery bio-system: Synthesis, characterization, and study of drug release kinetic. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2020, 594, 124662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Guo, W.; Li, L.; Yu, F.; Li, J.; Liu, L.; Fang, B.; Xia, L. Photothermally triggered biomimetic drug delivery of Teriparatide via reduced graphene oxide loaded chitosan hydrogel for osteoporotic bone regeneration. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 127413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munir, K.S.; Wen, C.; Li, Y. Carbon nanotubes and graphene as nanoreinforcements in metallic biomaterials: A review. Adv. Biosyst. 2019, 3, 1800212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, B.C.; Murray, E.; Wallace, G.G. Graphite oxide to graphene. Biomaterials to bionics. Adv. Mater. 2015, 27, 7563–7582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, M.; Wang, K.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, H.; Lu, X.; Duan, K. Molecular mechanisms of interactions between BMP-2 and graphene: Effects of functional groups and microscopic morphology. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 525, 146636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horch, R.E. Future perspectives in tissue engineering:‘Tissue Engineering’review series. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2006, 10, 4–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, S.R.; Li, Y.-C.; Jang, H.L.; Khoshakhlagh, P.; Akbari, M.; Nasajpour, A.; Zhang, Y.S.; Tamayol, A.; Khademhosseini, A. Graphene-based materials for tissue engineering. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2016, 105, 255–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

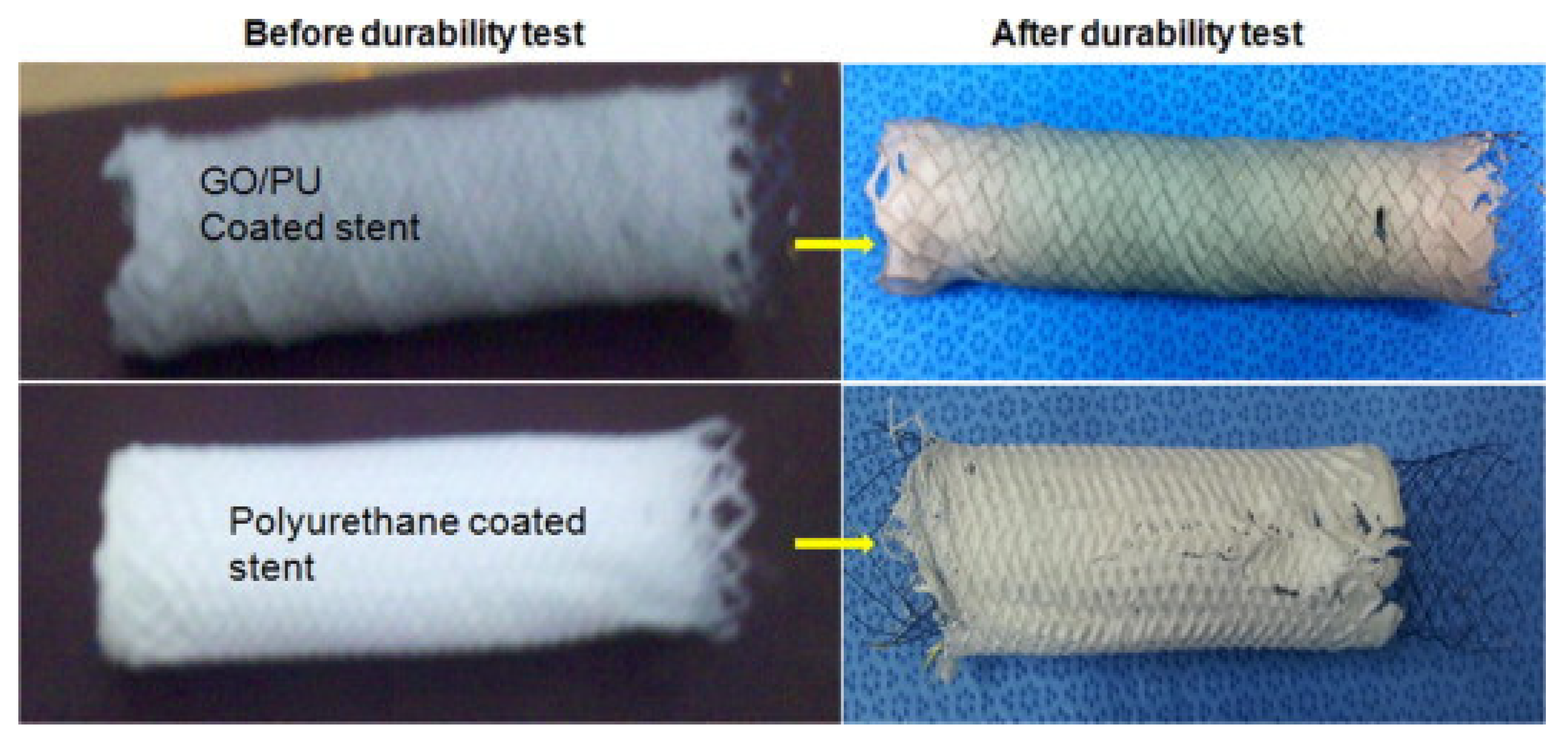

- Bahrami, S.; Solouk, A.; Mirzadeh, H.; Seifalian, A.M. Electroconductive polyurethane/graphene nanocomposite for biomedical applications. Compos. Part B Eng. 2019, 168, 421–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pant, H.R.; Pokharel, P.; Joshi, M.K.; Adhikari, S.; Kim, H.J.; Park, C.H.; Kim, C.S. Processing and characterization of electrospun graphene oxide/polyurethane composite nanofibers for stent coating. Chem. Eng. J. 2015, 270, 336–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, B.; Carroll, W. The evolution of cardiovascular stent materials and surfaces in response to clinical drivers: A review. Acta Biomater. 2009, 5, 945–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathmanapan, S.; Periyathambi, P.; Anandasadagopan, S.K. Fibrin hydrogel incorporated with graphene oxide functionalized nanocomposite scaffolds for bone repair—In vitro and in vivo study. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2020, 29, 102251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uhthoff, H.K.; Finnegan, M. The effects of metal plates on post-traumatic remodelling and bone mass. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Br. Vol. 1983, 65, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sansone, V.; Pagani, D.; Melato, M. The effects on bone cells of metal ions released from orthopaedic implants. A review. Clin. Cases Miner. Bone Metab. 2013, 10, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalili, R.; Zarrintaj, P.; Jafari, S.H.; Vahabi, H.; Saeb, M.R. Electroactive poly (p-phenylene sulfide)/r-graphene oxide/chitosan as a novel potential candidate for tissue engineering. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 154, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, E.; Li, T.; Chang, J.; Wu, C. Bioinspired multifunctional biomaterials with hierarchical microstructure for wound dressing. Acta Biomater. 2019, 100, 270–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Jyothirmayee Aravind, S.S.; Wu, H.; Forys, J.; Venkataraman, V.; Ramanujachary, K.; Hu, X. Tunable green graphene-silk biomaterials: Mechanism of protein-based nanocomposites. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2017, 79, 728–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daneshmandi, L.; Barajaa, M.; Tahmasbi Rad, A.; Sydlik, S.A.; Laurencin, C.T. Graphene-Based Biomaterials for Bone Regenerative Engineering: A Comprehensive Review of the Field and Considerations Regarding Biocompatibility and Biodegradation. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2020, 2001414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marques, P.A.; Gonçalves, G.; Singh, M.K.; Grácio, J. Graphene oxide and hydroxyapatite as fillers of polylactic acid nanocomposites: Preparation and characterization. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2012, 12, 6686–6692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chuan, D.; Fan, R.; Wang, Y.; Ren, Y.; Wang, C.; Du, Y.; Zhou, L.; Yu, J.; Gu, Y.; Chen, H. Stereocomplex poly (lactic acid)-based composite nanofiber membranes with highly dispersed hydroxyapatite for potential bone tissue engineering. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2020, 92, 108107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, J.M.; Pounder, R.J.; Dove, A.P. Synthesis of poly (lactide) s with modified thermal and mechanical properties. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2010, 31, 1923–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujishiro, S.; Kan, K.; Akashi, M.; Ajiro, H. Stability of adhesive interfaces by stereocomplex formation of polylactides and hybridization with nanoparticles. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2017, 141, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiesa, E.; Dorati, R.; Pisani, S.; Bruni, G.; Rizzi, L.G.; Conti, B.; Modena, T.; Genta, I. Graphene nanoplatelets for the development of reinforced PLA–PCL electrospun fibers as the next-generation of biomedical mats. Polymers 2020, 12, 1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahiri, D.; Dua, R.; Zhang, C.; De Socarraz-Novoa, I.; Bhat, A.; Ramaswamy, S.; Agarwal, A. Graphene Nanoplatelet-Induced Strengthening of UltraHigh Molecular Weight Polyethylene and Biocompatibility In vitro. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2012, 4, 2234–2241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, R.; Naskar, S.; Bhaskar, N.; Bose, S.; Basu, B. Modulation of Protein Adsorption and Cell Proliferation on Polyethylene Immobilized Graphene Oxide Reinforced HDPE Bionanocomposites. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 11954–11968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Tong, G.; Lin, D.; Chen, C.; Guo, H.; Xu, J.; Zhou, L. Graphene-reinforced metal matrix nanocomposites–a review. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2016, 32, 930–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Qin, L.; Yang, K.; Ma, Z.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, L.; Zhao, D. Materials evolution of bone plates for internal fixation of bone fractures: A review. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2020, 36, 190–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Teng, J.; Yu, J.-G.; Tan, A.-S.; Fu, D.-F.; Zhang, H. Fabrication of homogeneously dispersed graphene/Al composites by solution mixing and powder metallurgy. Int. J. Miner. Metall. Mater. 2018, 25, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khobragade, N.; Sikdar, K.; Kumar, B.; Bera, S.; Roy, D. Mechanical and electrical properties of copper-graphene nanocomposite fabricated by high pressure torsion. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 776, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Argumánez, A.; Llorente, I.; Caballero-Calero, O.; González, Z.; Menéndez, R.; Escudero, M.; García-Alonso, M. Electrochemical reduction of graphene oxide on biomedical grade CoCr alloy. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 465, 1028–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, H.P.; Xavior, M.A. Graphene reinforced metal matrix composite (GRMMC): A review. Procedia Eng. 2014, 97, 1033–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escudero, M.L.; Llorente, I.; Pérez-Maceda, B.T.; José-Pinilla, S.S.; Sánchez-López, L.; Lozano, R.M.; Aguado-Henche, S.; De Arriba, C.C.; Alobera-Gracia, M.A.; García-Alonso, M.C. Electrochemically reduced graphene oxide on CoCr biomedical alloy: Characterization, macrophage biocompatibility and hemocompatibility in rats with graphene and graphene oxide. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2020, 109, 110522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Hu, Y.; Gong, Z.; Liu, T.; Gong, T.; Liu, S.; Zhang, C.; Quan, L.; Kaveendran, B.; Pan, C. Fabrication of chitosan/heparinized graphene oxide multilayer coating to improve corrosion resistance and biocompatibility of magnesium alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2019, 104, 109947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heublein, B.; Rohde, R.; Kaese, V.; Niemeyer, M.; Hartung, W.; Haverich, A. Biocorrosion of magnesium alloys: A new principle in cardiovascular implant technology? Heart 2003, 89, 651–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golzar, H.; Mohammadrezaei, D.; Yadegari, A.; Rasoulianboroujeni, M.; Hashemi, M.; Omidi, M.; Yazdian, F.; Shalbaf, M.; Tayebi, L. Incorporation of functionalized reduced graphene oxide/magnesium nanohybrid to enhance the osteoinductivity capability of 3D printed calcium phosphate-based scaffolds. Compos. Part B Eng. 2020, 185, 107749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahin, M.; Munir, K.; Wen, C.; Li, Y. Nano-tribological behavior of graphene nanoplatelet–reinforced magnesium matrix nanocomposites. J. Magnes. Alloy. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lascano, S.; Chávez-Vásconez, R.; Muñoz-Rojas, D.; Aristizabal, J.; Arce, B.; Parra, C.; Acevedo, C.; Orellana, N.; Reyes-Valenzuela, M.; Gotor, F.J.; et al. Graphene-coated Ti-Nb-Ta-Mn foams: A promising approach towards a suitable biomaterial for bone replacement. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2020, 401, 126250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.; Du, Z.; Xiao, L.; Wei, F.; Yang, Y.; Li, M.; Qiu, Y.; Liu, J.; Chen, J.; Xiao, Y. Graphene oxide coated Titanium Surfaces with Osteoimmunomodulatory Role to Enhance Osteogenesis. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2020, 113, 110983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Goh, T.-W.; Yam, G.H.-F.; Thompson, B.C.; Hu, H.; Setiawan, M.; Sun, W.; Riau, A.K.; Tan, D.T.; Khor, K.A.; et al. A sintered graphene/titania material as a synthetic keratoprosthesis skirt for end-stage corneal disorders. Acta Biomater. 2019, 94, 585–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Chatterjee, K. Comprehensive review on the use of graphene-based substrates for regenerative medicine and biomedical devices. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 26431–26457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, X.; Liu, H.; Fan, Y. Graphene-based materials in regenerative medicine. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2015, 4, 1451–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morçimen, Z.G.; Taşdemir, Ş.; Erdem, Ç.; Güneş, F.; Şendemir, A. Investıgatıon of the Adherence and Prolıferatıon Characterıstıcs of SH-SY5Y Neuron Model Cells on Graphene Foam Surfaces. Mater. Today Proc. 2019, 19, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

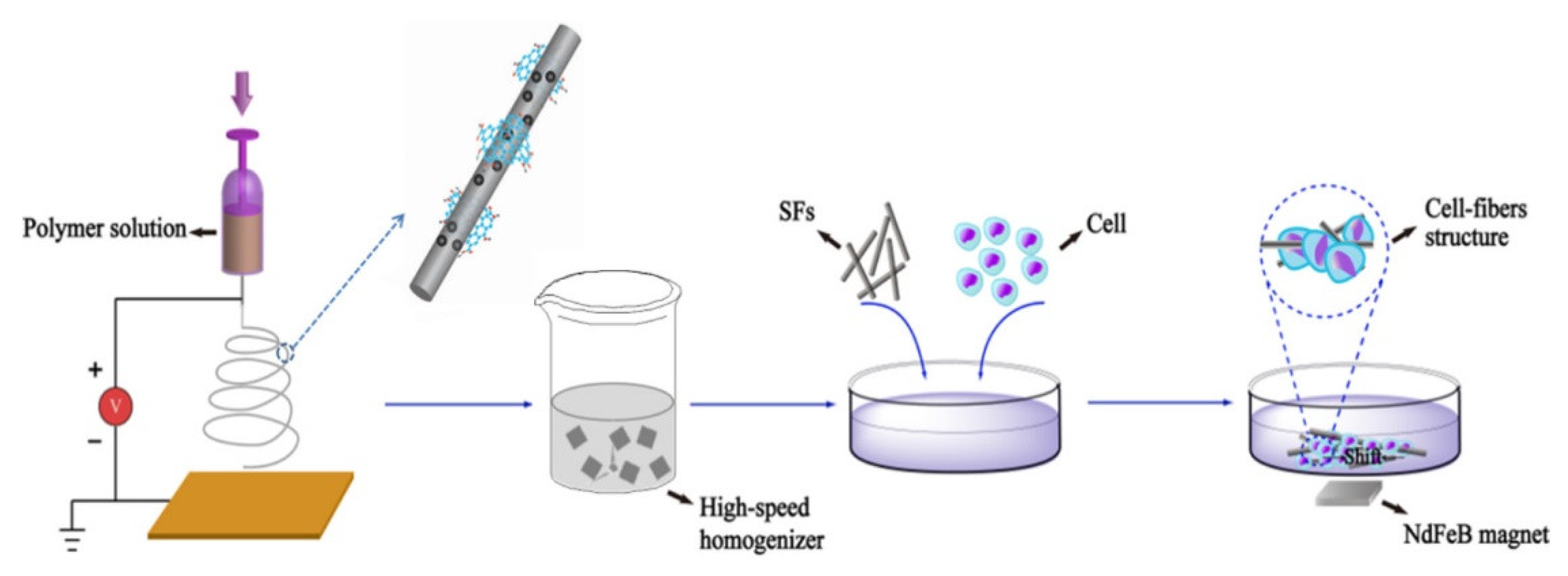

- Feng, Z.-Q.; Shi, C.; Zhao, B.; Wang, T. Magnetic electrospun short nanofibers wrapped graphene oxide as a promising biomaterials for guiding cellular behavior. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2017, 81, 314–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, G.; Kumar, N.; Srivastava, A. Highly elastic, electroconductive, immunomodulatory graphene crosslinked collagen cryogel for spinal cord regeneration. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2021, 118, 111518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekuła-Stryjewska, M.; Noga, S.; Dźwigońska, M.; Adamczyk, E.; Karnas, E.; Jagiełło, J.; Szkaradek, A.; Chytrosz, P.; Boruczkowski, D.; Madeja, Z.; et al. Graphene-based materials enhance cardiomyogenic and angiogenic differentiation capacity of human mesenchymal stem cells in vitro—Focus on cardiac tissue regeneration. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2021, 119, 111614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambrano-Andazol, I.; Vázquez, N.; Chacón, M.; Sánchez-Avila, R.M.; Persinal, M.; Blanco, C.; González, Z.; Menéndez, R.; Sierra, M.; Fernández-Vega, Á.; et al. Reduced graphene oxide membranes in ocular regenerative medicine. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2020, 114, 111075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, C.R.; Kondiah, P.P.; Choonara, Y.E.; Du Toit, L.C.; Ally, N.; Pillay, V. Hydrogel Biomaterials for Application in Ocular Drug Delivery. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ginestra, P. Manufacturing of polycaprolactone—Graphene fibers for nerve tissue engineering. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2019, 100, 103387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polo, Y.; Luzuriaga, J.; Iturri, J.; Irastorza, I.; Toca-Herrera, J.L.; Ibarretxe, G.; Unda, F.; Sarasua, J.-R.; Pineda, J.R.; Larrañaga, A. Nanostructured scaffolds based on bioresorbable polymers and graphene oxide induce the aligned migration and accelerate the neuronal differentiation of neural stem cells. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2021, 31, 102314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.; Choi, J.H.; Kim, S.; Jang, I.; Jeong, S.; Lee, J.Y. Micropatterned conductive hydrogels as multifunctional muscle-mimicking biomaterials: Graphene-incorporated hydrogels directly patterned with femtosecond laser ablation. Acta Biomater. 2019, 97, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Techaniyom, P.; Tanurat, P.; Sirivisoot, S. Osteoblast differentiation and gene expression analysis on anodized titanium samples coated with graphene oxide. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 526, 146646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacon, M.; Bradley, S.J.; Nann, T. Graphene quantum dots. Part. Part. Syst. Charact. 2014, 31, 415–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasouni, A.; Chatzimitakos, T.; Stalikas, C. Bioimaging applications of carbon nanodots: A review. C J. Carbon Res. 2019, 5, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, P.; Tang, L.; Teng, K.S.; Lau, S.P. Graphene quantum dots from chemistry to applications. Mater. Today Chem. 2018, 10, 221–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Gao, W.; Gupta, B.K.; Liu, Z.; Romero-Aburto, R.; Ge, L.; Song, L.; Alemany, L.B.; Zhan, X.; Gao, G. Graphene quantum dots derived from carbon fibers. Nano Lett. 2012, 12, 844–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, R.; Xiang, C.; Lin, J.; Peng, Z.; Huang, K.; Yan, Z.; Cook, N.P.; Samuel, E.L.; Hwang, C.-C.; Ruan, G. Coal as an abundant source of graphene quantum dots. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiti, S.; Kundu, S.; Roy, C.N.; Das, T.K.; Saha, A. Synthesis of excitation independent highly luminescent graphene quantum dots through perchloric acid oxidation. Langmuir 2017, 33, 14634–14642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, J.; Zhu, Y.; Yang, X.; Zong, J.; Zhang, J.; Li, C. One-pot hydrothermal synthesis of graphene quantum dots surface-passivated by polyethylene glycol and their photoelectric conversion under near-infrared light. New J. Chem. 2012, 36, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Li, Z.; Zhu, X.; Hu, N.; Wei, H.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, Y. Hydrothermal/Solvothermal Synthesis of Graphene Quantum Dots and Their Biological Applications. Nano Biomed. Eng. 2013, 5, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.L.; Ji, J.; Fei, R.; Wang, C.Z.; Lu, Q.; Zhang, J.R.; Jiang, L.P.; Zhu, J.J. A facile microwave avenue to electrochemiluminescent two-color graphene quantum dots. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2012, 22, 2971–2979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, S.; Shao, M.; Lee, S.-T. Upconversion and downconversion fluorescent graphene quantum dots: Ultrasonic preparation and photocatalysis. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 1059–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Hu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Shi, G.; Deng, L.; Hou, Y.; Qu, L. An electrochemical avenue to green-luminescent graphene quantum dots as potential electron-acceptors for photovoltaics. Adv. Mater. 2011, 23, 776–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, D.; Zhang, J.; Li, Z.; Wu, M. Hydrothermal route for cutting graphene sheets into blue-luminescent graphene quantum dots. Adv. Mater. 2010, 22, 734–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Lin, L.; Chen, X. Fluorescent Graphene Quantum Dots for the Determination of Metal Ions. In Novel Nanomaterials for Biomedical, Environmental and Energy Applications; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 215–239. [Google Scholar]

- Mintz, K.J.; Bartoli, M.; Rovere, M.; Zhou, Y.; Hettiarachchi, S.D.; Paudyal, S.; Chen, J.; Domena, J.B.; Liyanage, P.Y.; Sampson, R.; et al. A deep investigation into the structure of carbon dots. Carbon 2021, 173, 433–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritter, K.A.; Lyding, J.W. The influence of edge structure on the electronic properties of graphene quantum dots and nanoribbons. Nat. Mater. 2009, 8, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Song, Y.; Zhao, X.; Shao, J.; Zhang, J.; Yang, B. The photoluminescence mechanism in carbon dots (graphene quantum dots, carbon nanodots, and polymer dots): Current state and future perspective. Nano Res. 2015, 8, 355–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Dong, H.; Pang, B.; Shao, F.; Zhang, C.; Yu, L.; Dong, L. Theoretical study on the optical and electronic properties of graphene quantum dots doped with heteroatoms. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018, 20, 15244–15252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.; Liao, L.; Xu, X.; Zou, M.; Liu, F.; Li, N. The electron-transfer based interaction between transition metal ions and photoluminescent graphene quantum dots (GQDs): A platform for metal ion sensing. Talanta 2013, 117, 152–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shang, W.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, M.; Fan, Z.; Sun, Y.; Han, M.; Fan, L. The uptake mechanism and biocompatibility of graphene quantum dots with human neural stem cells. Nanoscale 2014, 6, 5799–5806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, T.; Wang, X.; Yang, L.-Y.; He, H.; Ba, X.-X.; Zhao, J.; Jiang, F.-L.; Liu, Y. Red, yellow, and blue luminescence by graphene quantum dots: Syntheses, mechanism, and cellular imaging. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 24846–24856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campuzano, S.; Yáñez-Sedeño, P.; Pingarrón, J.M. Carbon dots and graphene quantum dots in electrochemical biosensing. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannazzo, D.; Pistone, A.; Salamò, M.; Galvagno, S.; Romeo, R.; Giofré, S.V.; Branca, C.; Visalli, G.; Di Pietro, A. Graphene quantum dots for cancer targeted drug delivery. Int. J. Pharm. 2017, 518, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Na, X.; Wang, H.; Wang, C.; Yuan, Z.; Zhu, B.-W.; Tan, M. The effects of carbon dots produced by the Maillard reaction on the HepG2 cell substance and energy metabolism. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 6487–6495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Advantages | Disadvantages | |

|---|---|---|

| Graphene |

|

|

| GO |

|

|

| rGO |

|

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Catania, F.; Marras, E.; Giorcelli, M.; Jagdale, P.; Lavagna, L.; Tagliaferro, A.; Bartoli, M. A Review on Recent Advancements of Graphene and Graphene-Related Materials in Biological Applications. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 614. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11020614

Catania F, Marras E, Giorcelli M, Jagdale P, Lavagna L, Tagliaferro A, Bartoli M. A Review on Recent Advancements of Graphene and Graphene-Related Materials in Biological Applications. Applied Sciences. 2021; 11(2):614. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11020614

Chicago/Turabian StyleCatania, Federica, Elena Marras, Mauro Giorcelli, Pravin Jagdale, Luca Lavagna, Alberto Tagliaferro, and Mattia Bartoli. 2021. "A Review on Recent Advancements of Graphene and Graphene-Related Materials in Biological Applications" Applied Sciences 11, no. 2: 614. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11020614

APA StyleCatania, F., Marras, E., Giorcelli, M., Jagdale, P., Lavagna, L., Tagliaferro, A., & Bartoli, M. (2021). A Review on Recent Advancements of Graphene and Graphene-Related Materials in Biological Applications. Applied Sciences, 11(2), 614. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11020614