A Test Platform for Managing School Stress Using a Virtual Reality Group Chatbot Counseling System

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and Group Counseling

2.2. Immersive Technology Applied as a Psychological Treatment

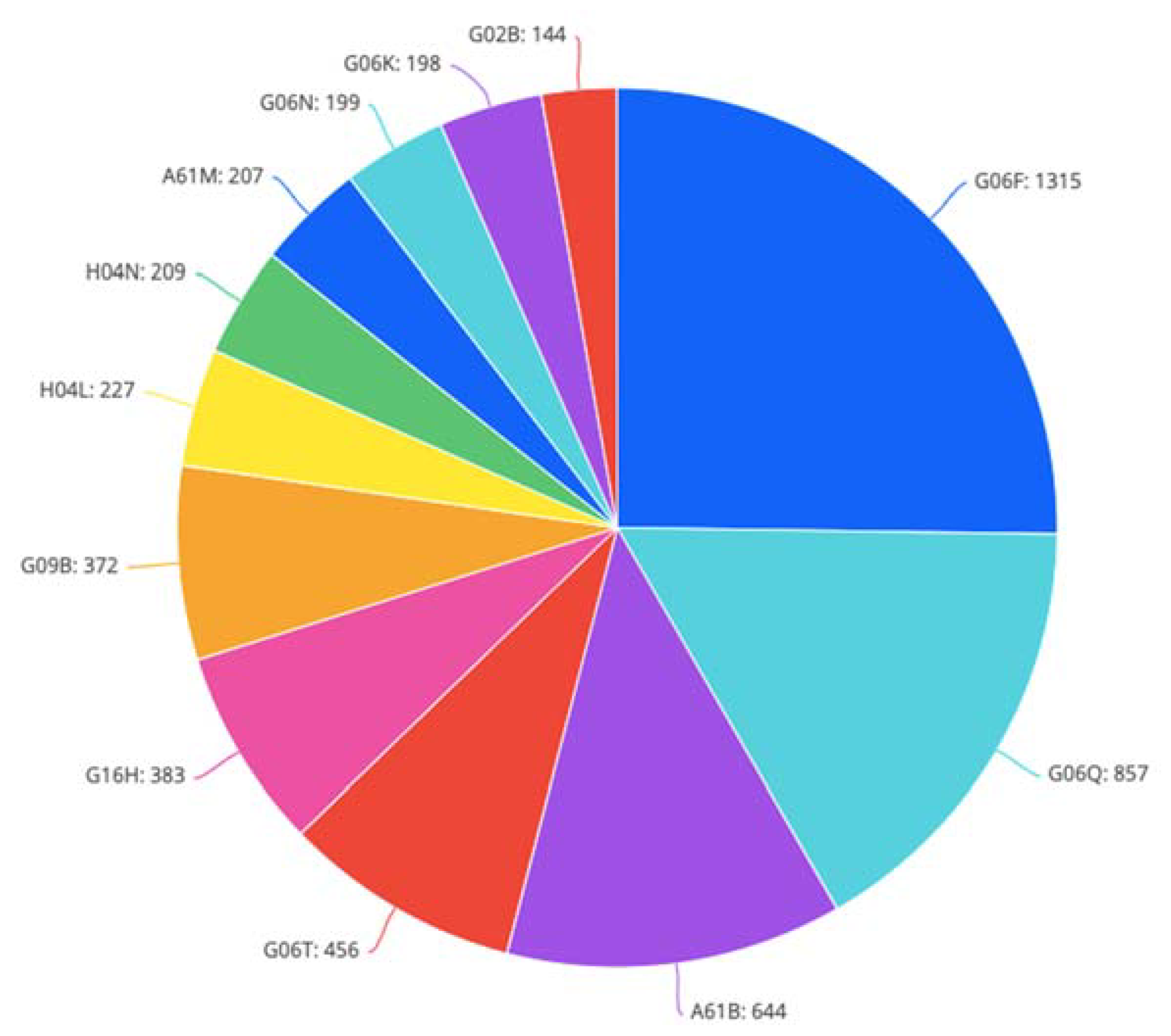

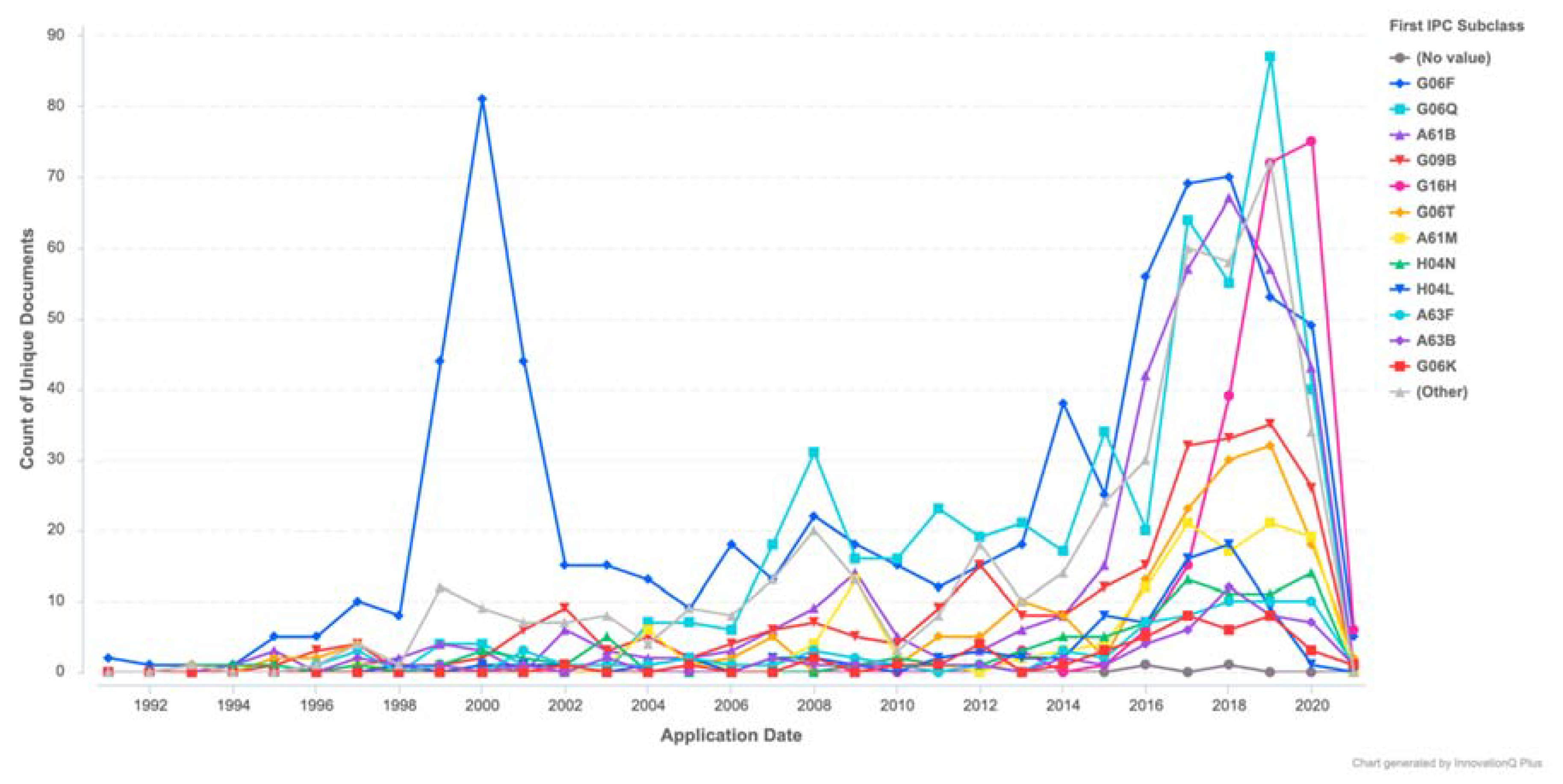

2.3. Patent Review

2.4. Chatbots

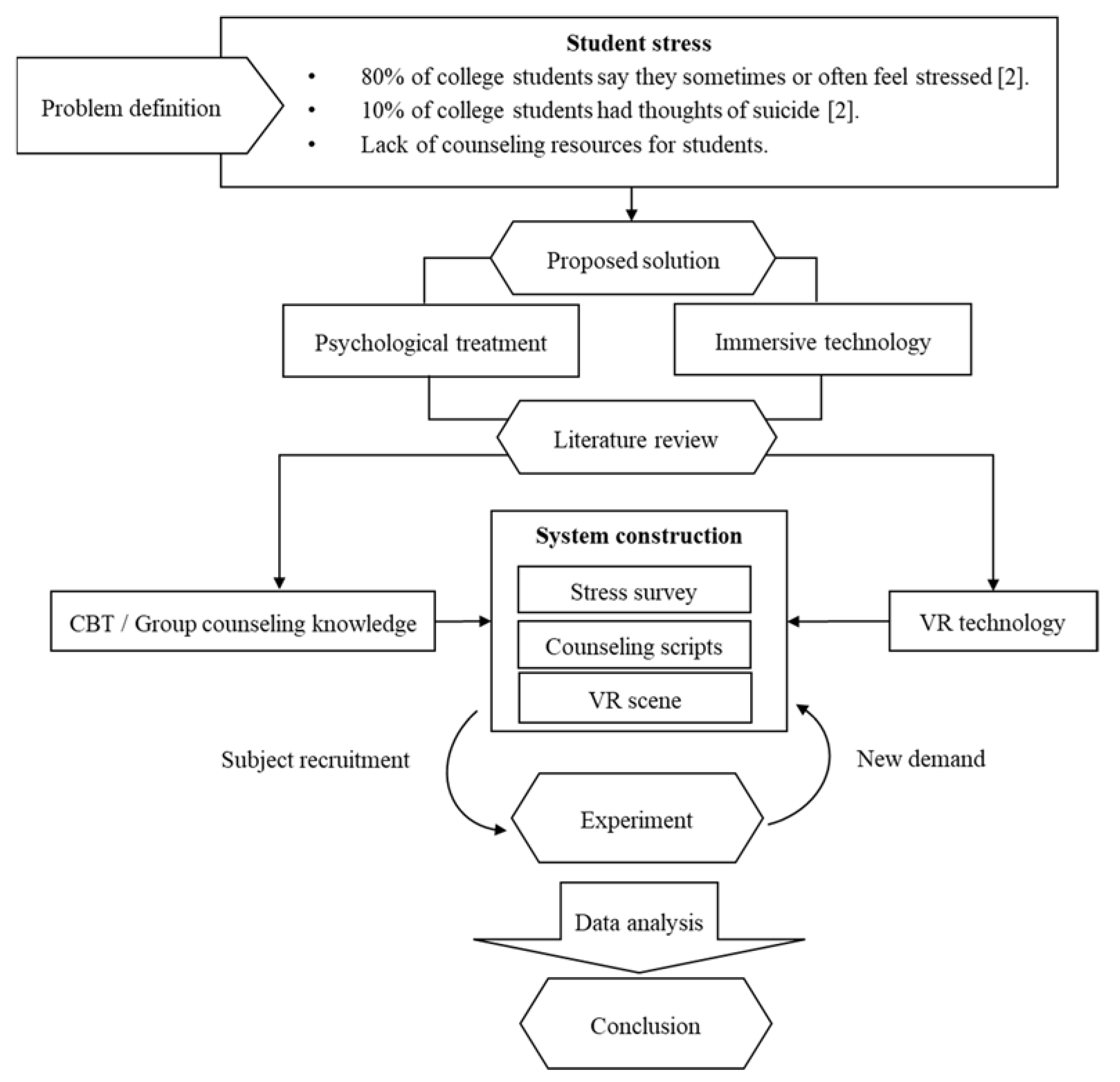

3. Methodology

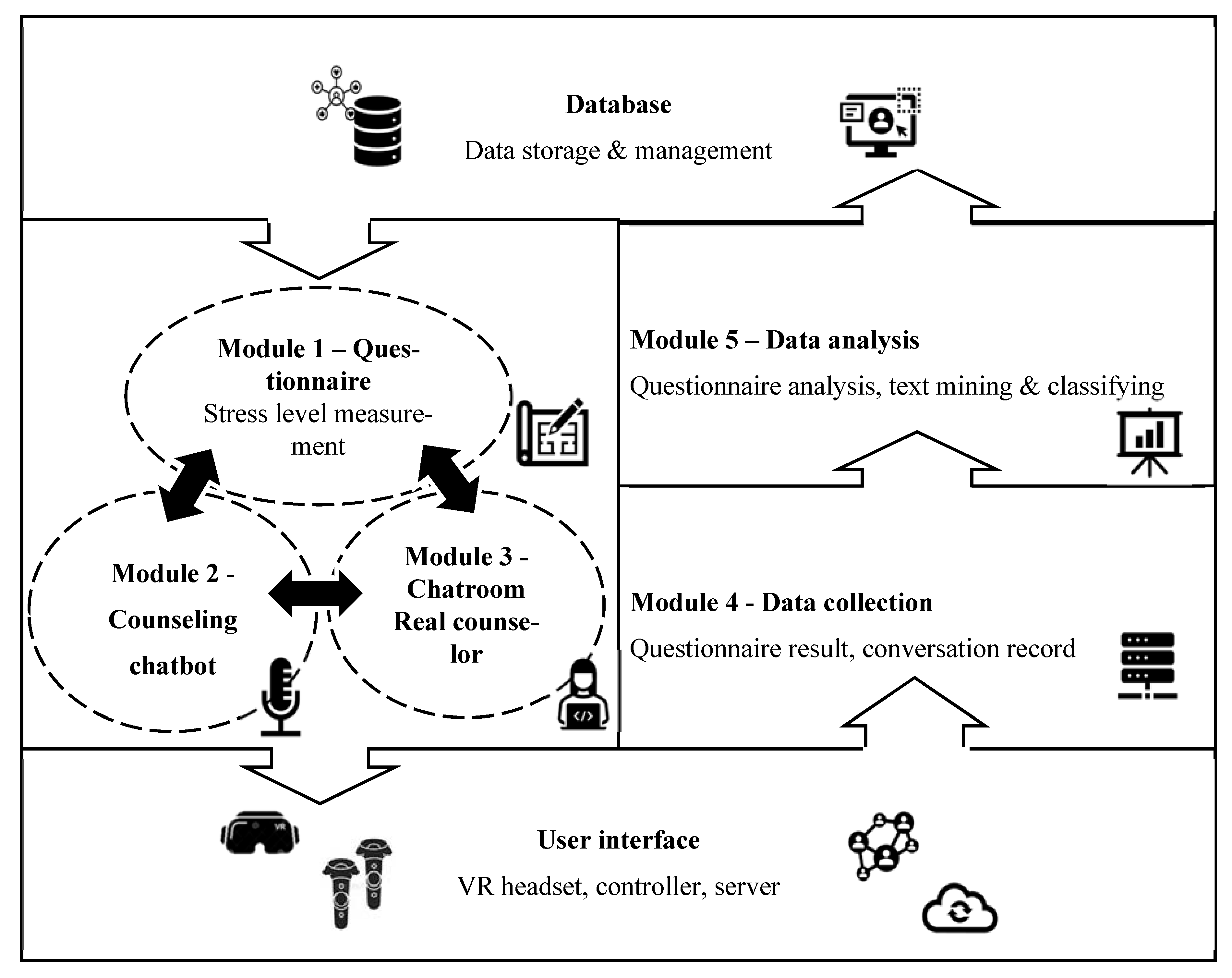

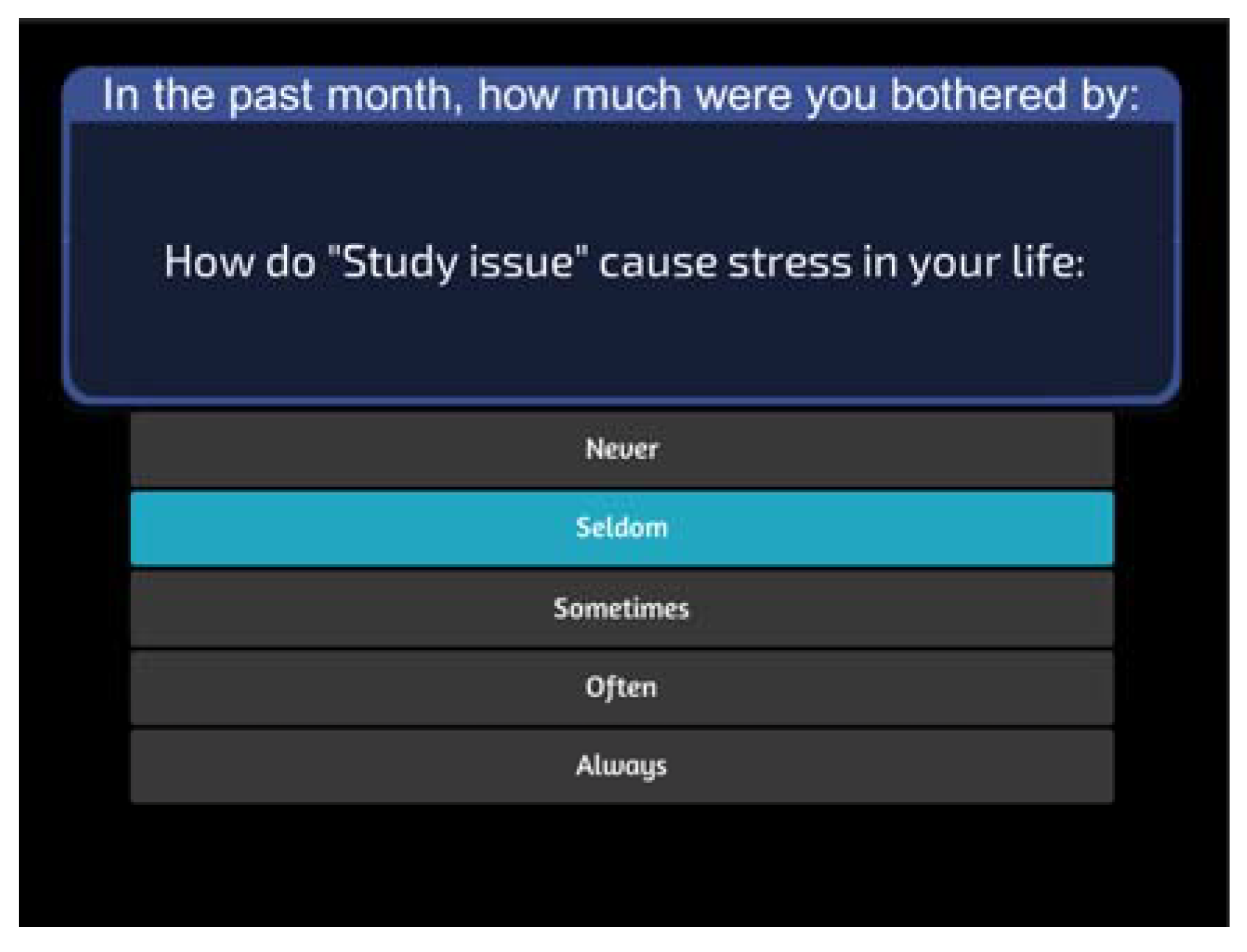

3.1. Module 1 Questionnaire: A Survey for Measuring Stress Level

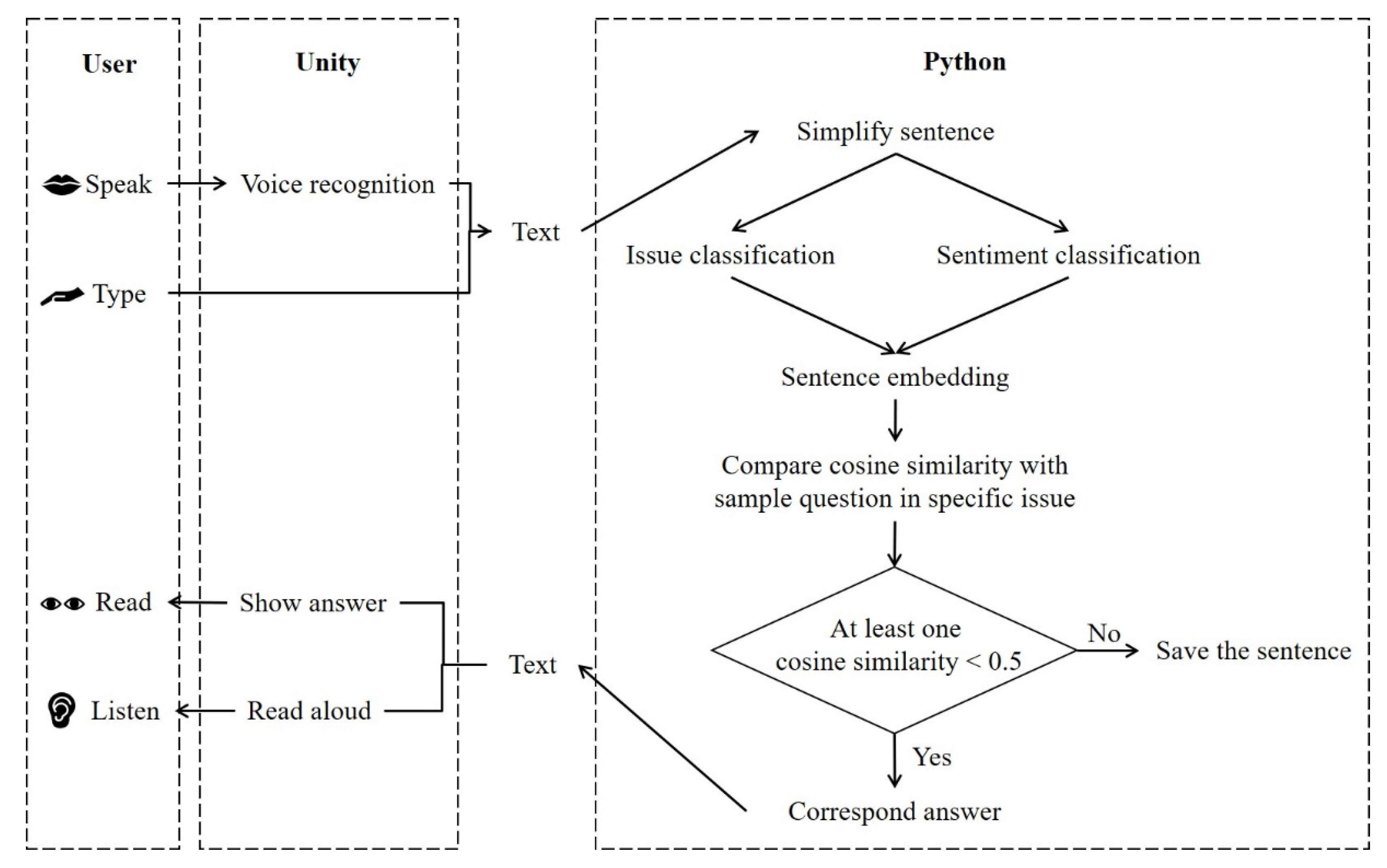

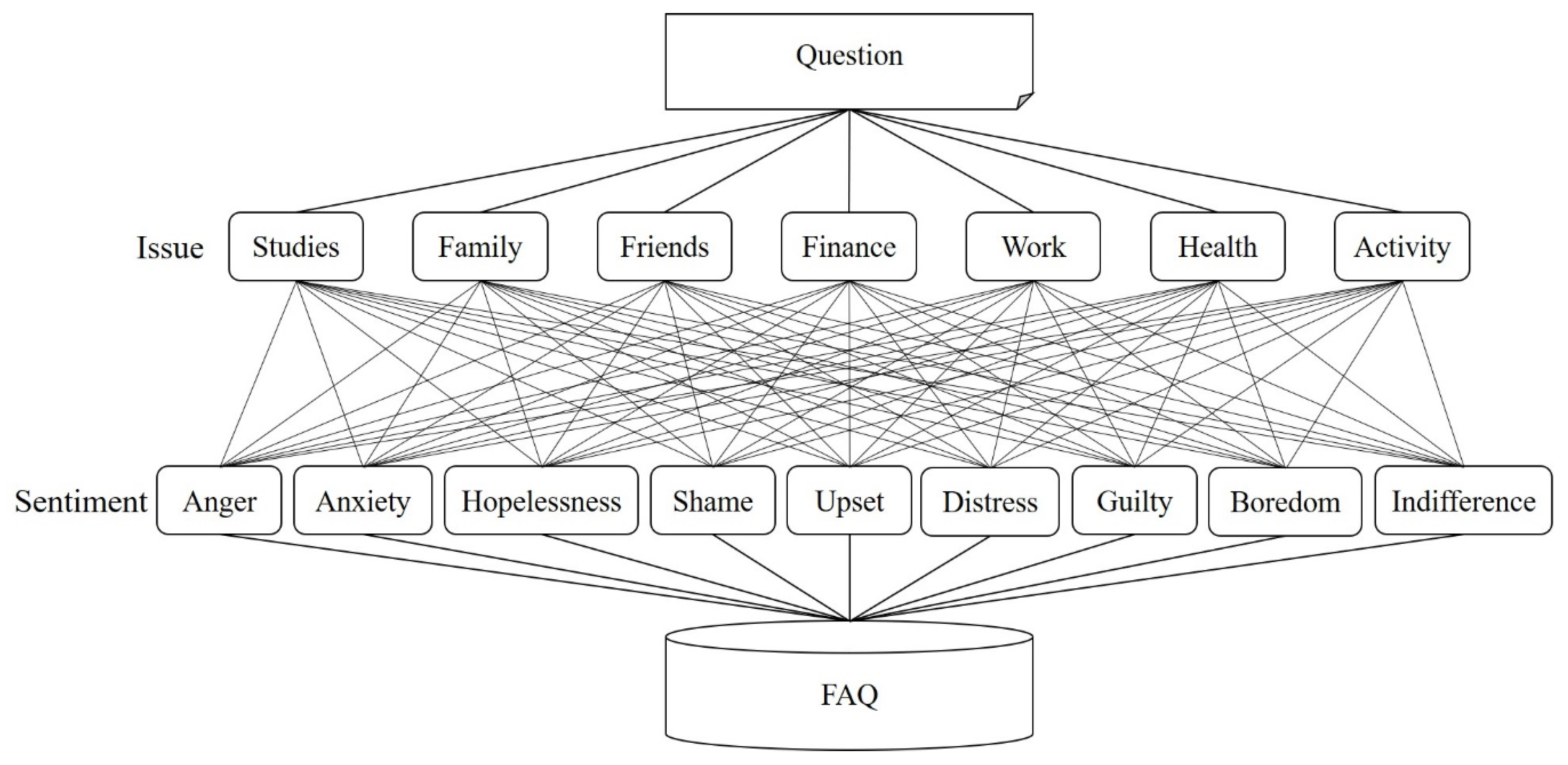

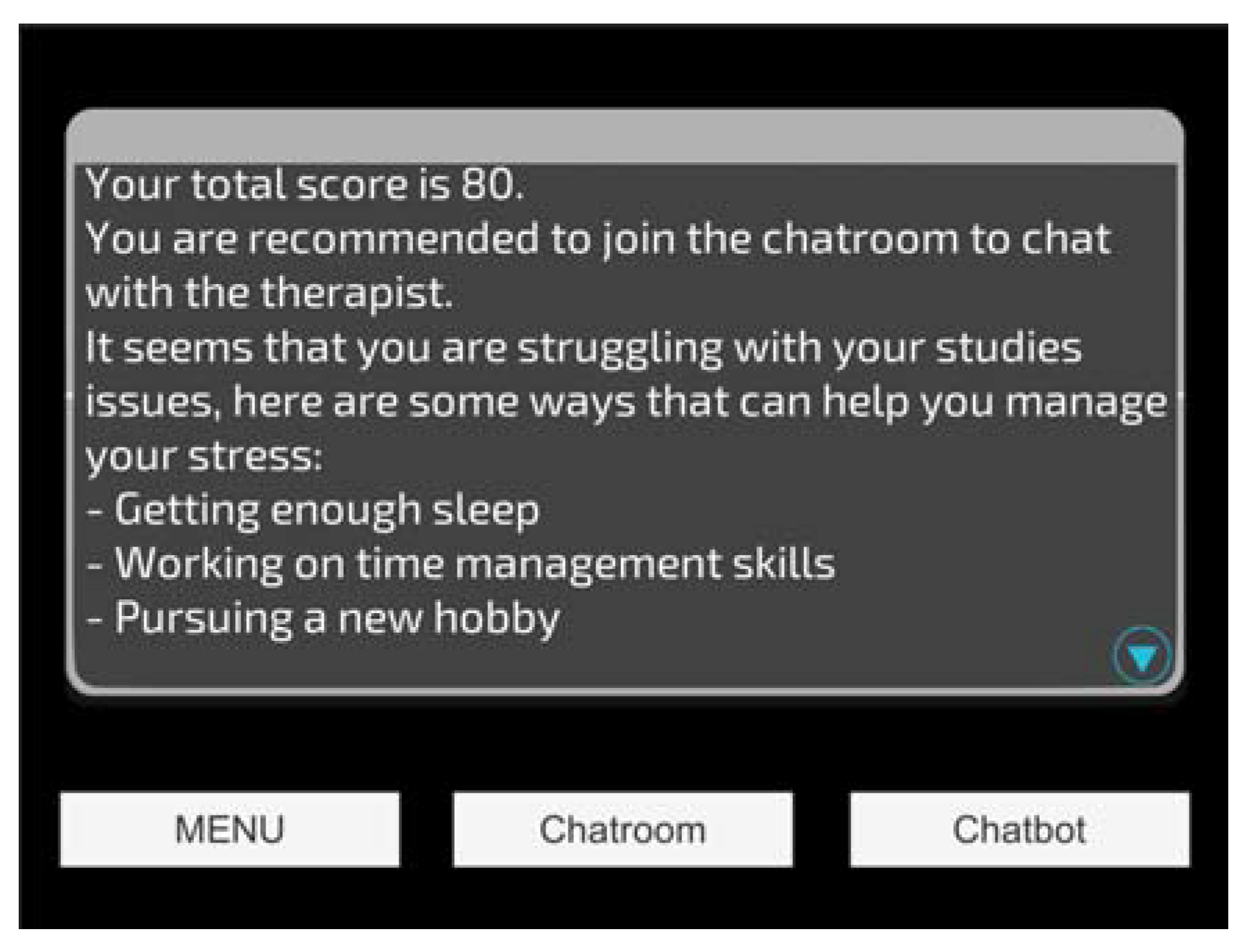

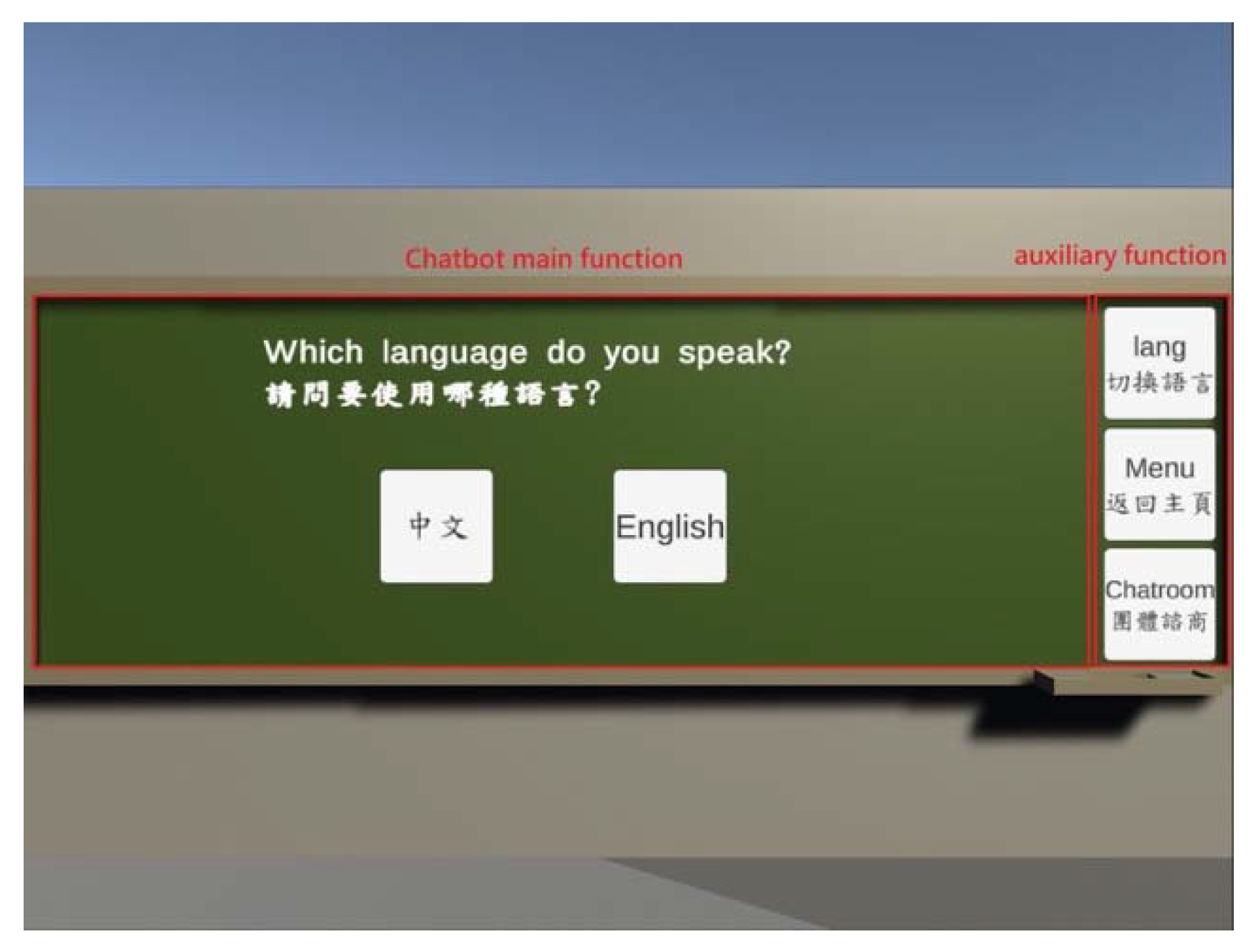

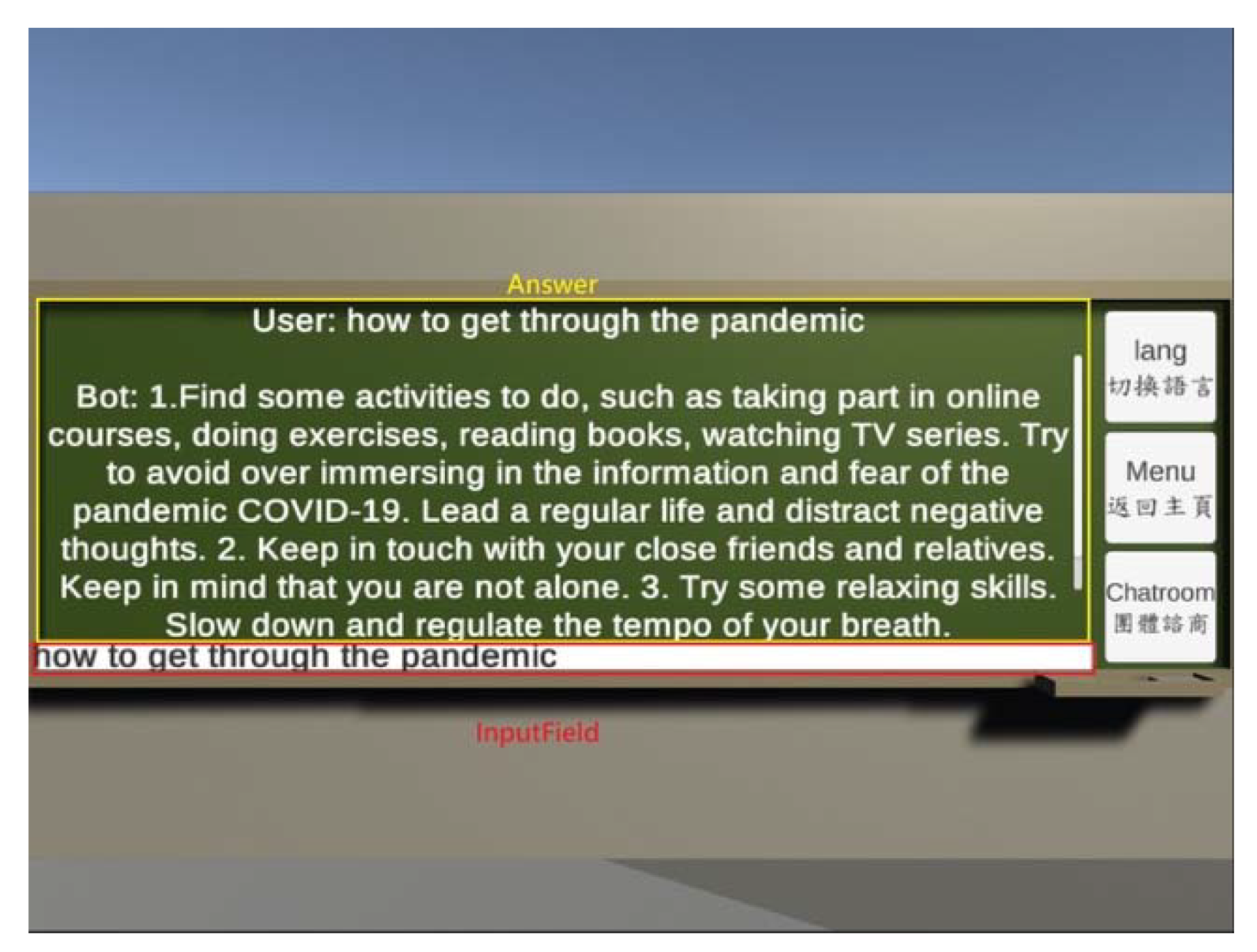

3.2. Module 2 Counseling Chatbot: A Knowledge-Based Chatbot

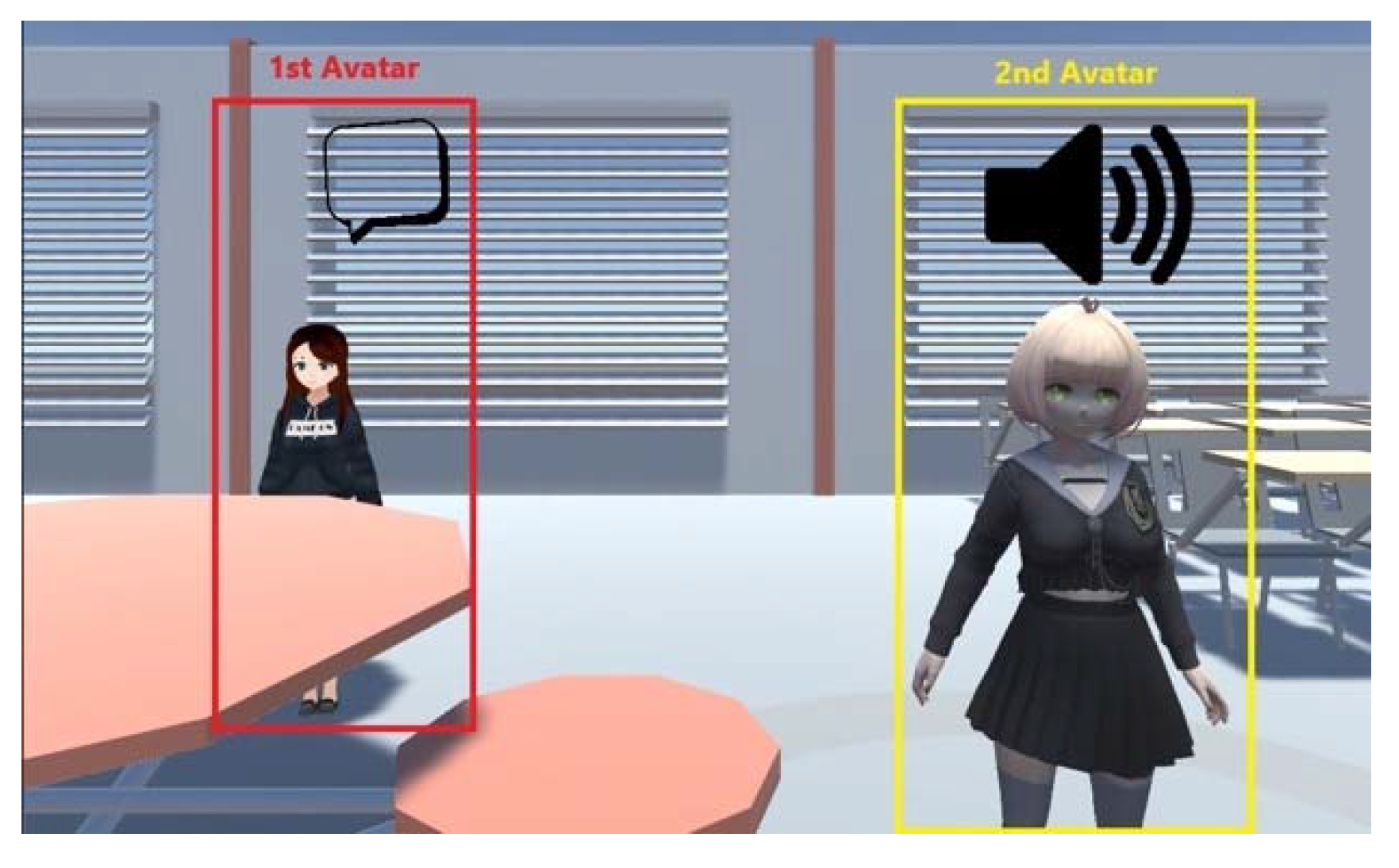

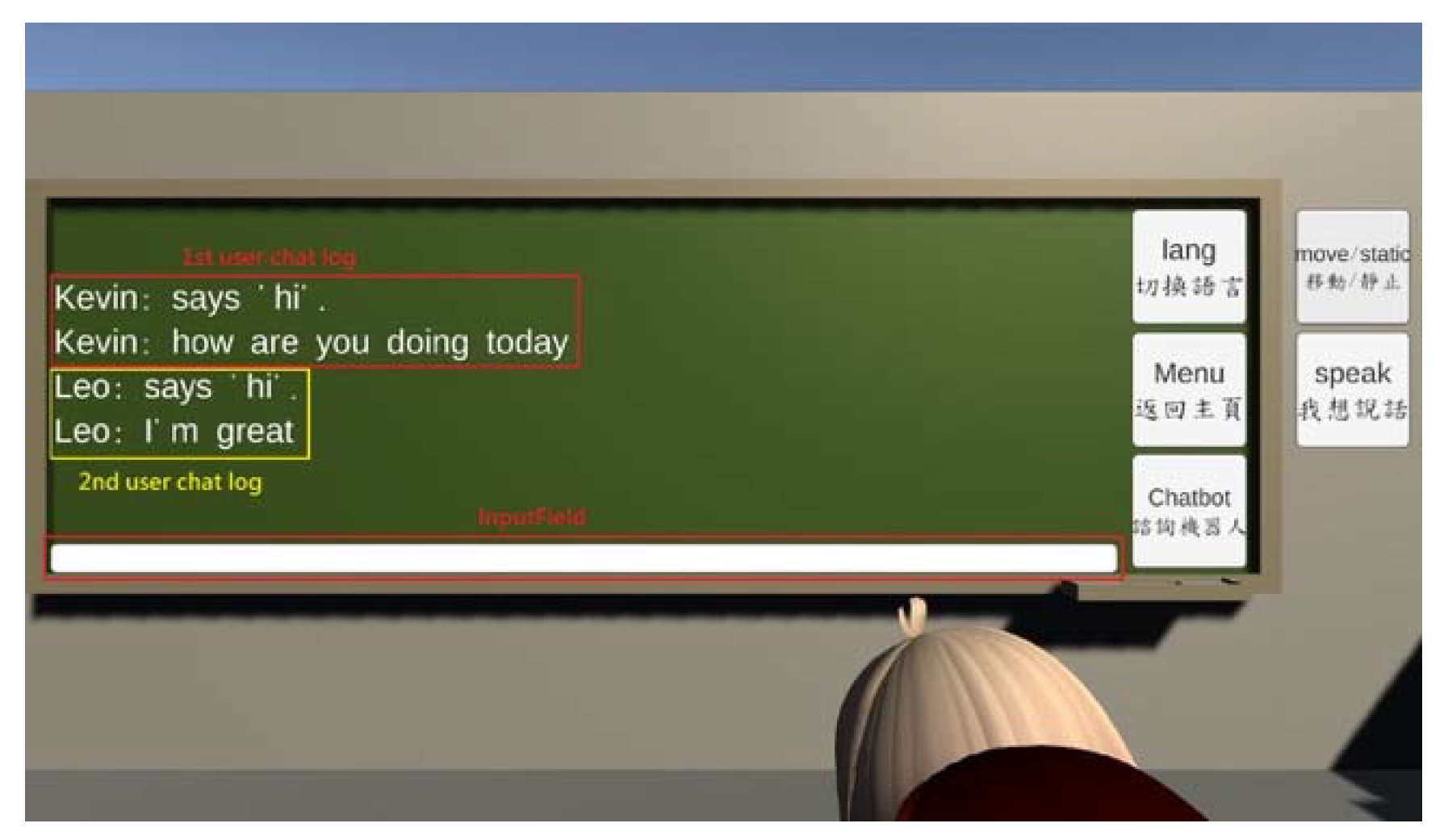

3.3. Module 3 VR-Enabled Chatroom: A Group Therapy VR Interface with a Real Counselor

4. Case Demonstration

4.1. Offline Survey Result

4.2. Online VR Group Counseling System Demonstration

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

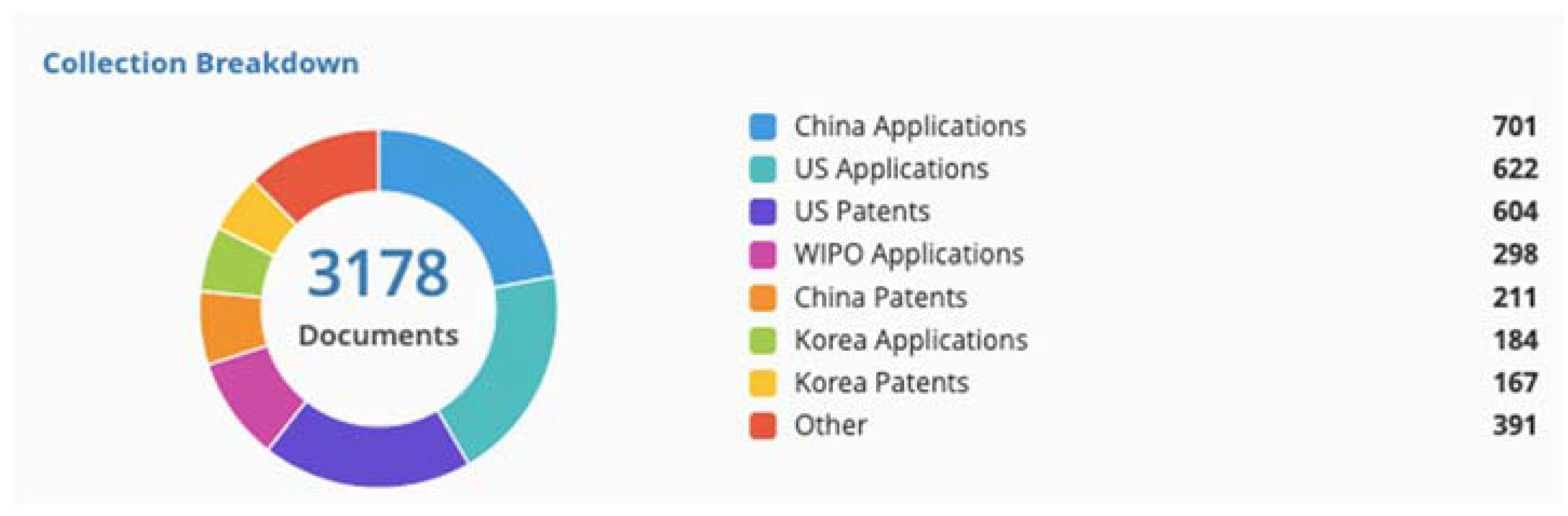

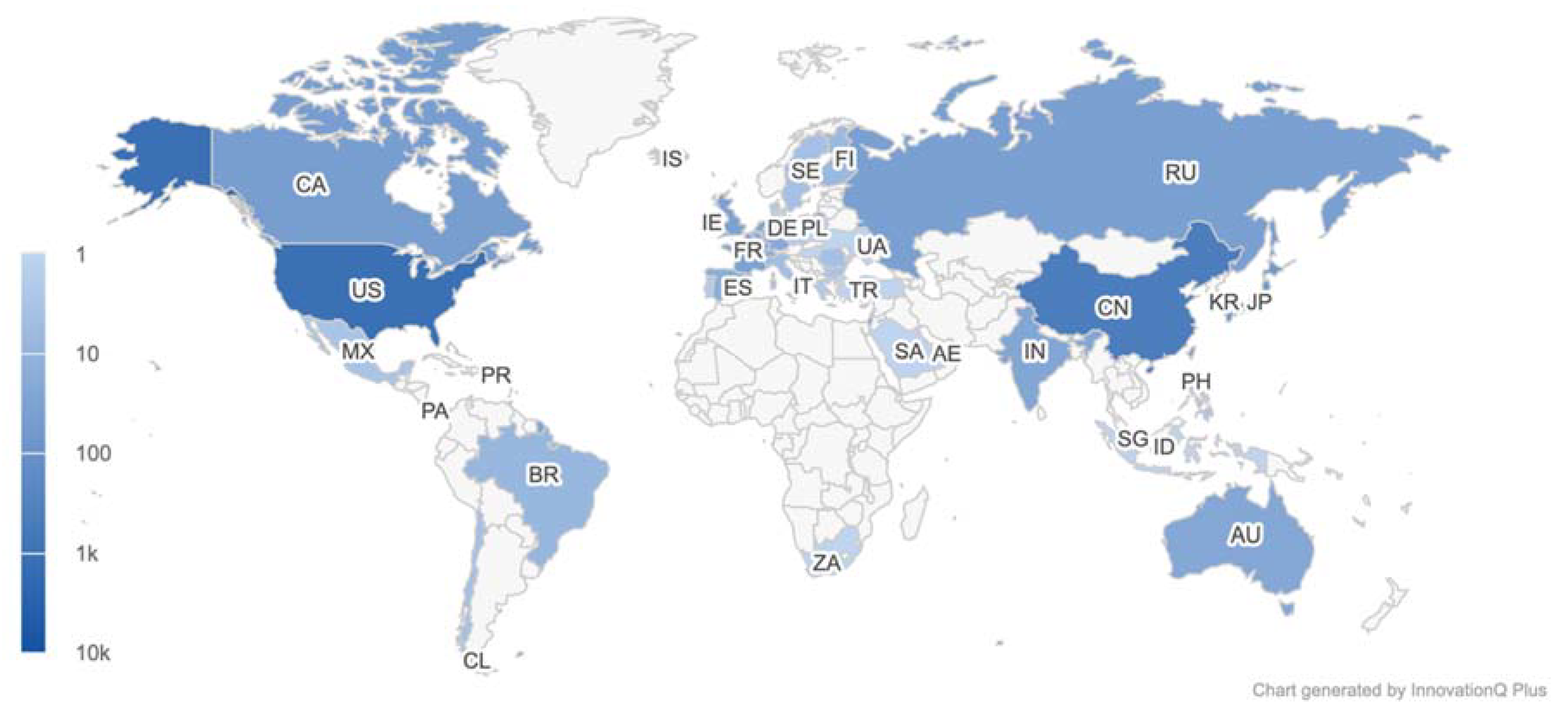

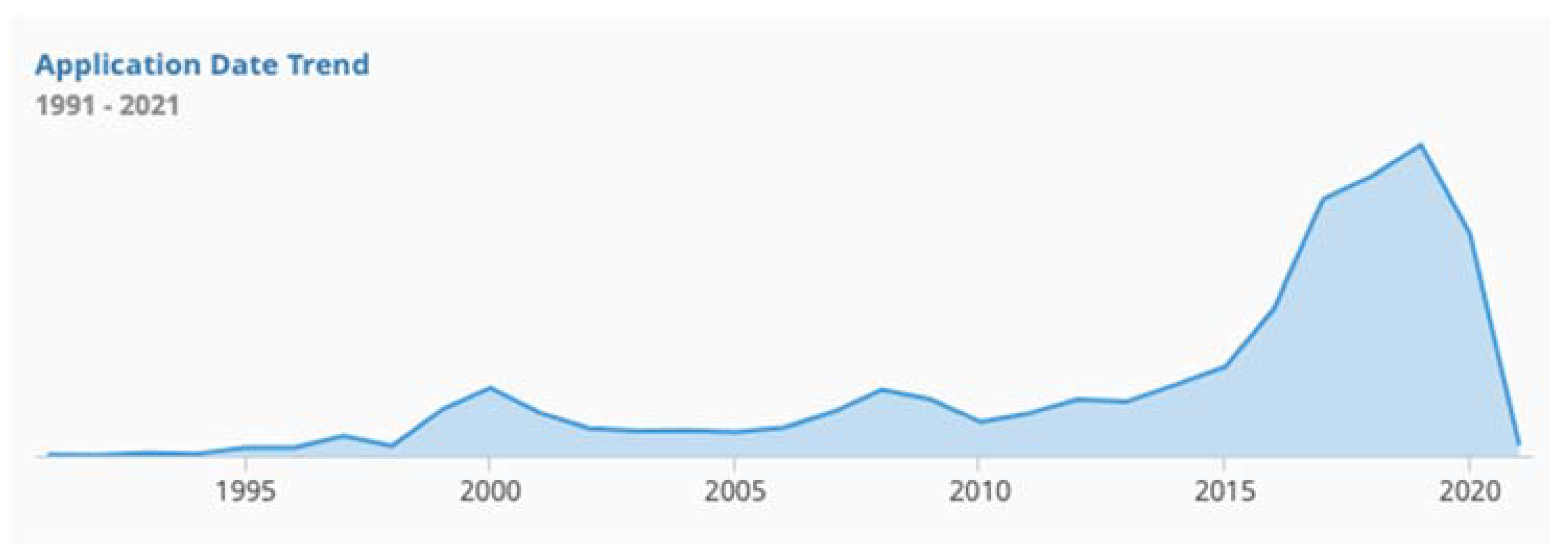

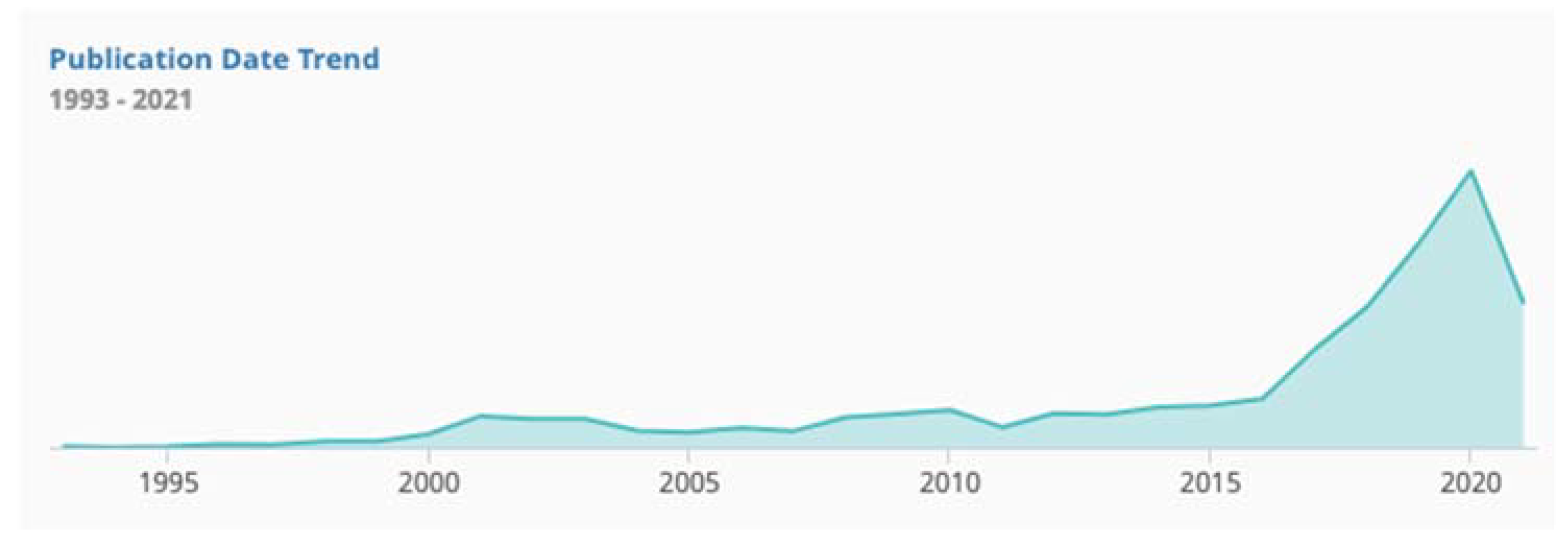

Appendix A. Visualized Patent Analysis Result

Appendix B. Survey for School Stress—VR Group Therapy Application

- Phone number: _______________

- E-mail address: ______________________________

- Are you willing to participate in a virtual reality group therapy experiment for school stress?

- The name of your institution: _________________________

- The name of your program of study: _________________________

- Your current class level is:

- 4.

- Your gender is:

- 5.

- Your age is: __________

- 6.

- How stressed do you feel on a daily basis during the academic year? Please circle your stress level:(Low) 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 (High)

- 7.

- What are the usual causes of stress in your life? (Please circle the level you feel)

| Never | Seldom | Sometimes | Often | Always | |

| Studies issues | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Financial issues | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Family issues | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Friend issues | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Issues with the significant other (partner) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Work (job-related) issues | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Health Related Issues | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Sports/Athletics activities issues | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| My involvement in clubs and organizations | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Other: _________________________ | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

- 8.

- How do you usually experience stress (in the situations selected from the list above)? Please, describe using a few words to describe the physical sensations and the feelings you encounter when you are feeling stressed.

- 9.

- What are the usual BEHAVIORAL effects of stress you’ve noticed with yourself? (Please circle the level you feel)

| Never | Seldom | Sometimes | Often | Always | |

| Change in activity levels | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Decreased efficiency and effectiveness | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Difficulty communicating | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Increased sense of humor/gallows humor | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Irritability, outbursts of anger, frequent arguments | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Inability to rest, relax or let down | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Change in eating habits | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Change in sleep patterns | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Change in activity performance | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Periods of crying | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Increased use of tobacco, alcohol, drugs, sugar or caffeine | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Hyper-vigilance about safety or the surrounding environment | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Avoidance of activities or places that trigger memories | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Accident prone | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Other: _________________________ | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

- 10.

- What are the usual PSYCHOLOGICAL or EMOTIONAL effects of stress you’ve noticed at yourself? (Please circle the level you feel)

| Never | Seldom | Sometimes | Often | Always | |

| Feeling heroic, euphoric or invulnerable | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Denial | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Anxiety or fear | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Worry about safety of self or others | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Irritability or anger | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Restlessness | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Sadness, moodiness, grief or depression | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Vivid or distressing dreams | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Guilt or “survivor guilt” | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Feeling overwhelmed, helpless or hopeless | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Feeling isolated, lost, lonely or abandoned | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Apathy | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Over-identification with survivors | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Feeling misunderstood or unappreciated | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Other: _________________________ | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

- 11.

- What are the usual PHYSICAL effects of stress you’ve noticed at yourself? (Please circle the level you feel)

| Never | Seldom | Sometimes | Often | Always | |

| Increased heart rate and respirations | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Increased blood pressure | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Upset stomach, nausea, diarrhea | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Increased or decreased appetite which may be accompanied by weight loss or gain | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Sweating or chills | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Tremors or muscle twitching | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Muffled hearing | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Tunnel vision | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Feeling uncoordinated | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Headaches | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Sore or aching muscles | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Light sensitive vision | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Lower back pain | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Feeling a “lump in the throat” | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Easily startled | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Fatigue that does not improve with sleep | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Menstrual cycle changes | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Change in sexual desire or response | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Decreased resistance to colds, flu, infections | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Flare up of allergies, asthma, or arthritis | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Hair loss | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Other: _________________________ | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

- 12.

- What are the usual COGNITIVE effects of stress you’ve noticed at yourself? (Please circle the level you feel)

| Never | Seldom | Sometimes | Often | Always | |

| Memory problems/forgetfulness | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Disorientation | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Confusion | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Slowness in thinking, analyzing, or comprehending | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Difficulty calculating, setting priorities or making decisions | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Difficulty concentrating | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Limited attention span | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Loss of objectivity | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Inability to stop thinking about the disaster or an incident | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Other: _________________________ | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

- 13.

- What are the usual SOCIAL effects of stress you’ve noticed at yourself? (Please circle the level you feel)

| Never | Seldom | Sometimes | Often | Always | |

| Withdrawing or isolating from people | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Difficulty listening | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Difficulty sharing ideas | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Difficulty engaging in mutual problem solving | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Blaming | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Criticizing | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Intolerance of group process | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Difficulty in giving or accepting support or help | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Impatient with or disrespectful to others | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Other: _________________________ | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

- 14.

- What are your personal methods to relieve stress? (Please circle the level you feel)

| Never | Seldom | Sometimes | Often | Always | |

| Eating | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Sleeping | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Drinking | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Drugs | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Sports/Exercise | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Talking with someone | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Shopping | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Computer Games | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Social Media | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Other: _________________________ | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

- 15.

- How able do you feel to handle stress when you are experiencing it? Please circle your coping skills level:

- 16.

- What are the most pressing stress factors in your current academic context (related to this program of study)? (Please circle the level you feel)

| Never | Seldom | Sometimes | Often | Always | |

| Study workload | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Grades | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Financial pressure (e.g., tuition, living costs) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Work (and Study)—Life balance | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Relationship with (some) faculty members | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Relationship with other students | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Campus social life | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Other: _________________________ | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

- 17.

- What is something that our university could do to help lower your stress?

| In the Past Month, How Much Were You Bothered by: (Please Circle the Level You Felt) | Not at All | A Little Bit | Moderately | Quite a Bit | Extremely |

| 1. Repeated, disturbing, and unwanted memories of the stressful experience? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 2. Repeated, disturbing dreams of the stressful experience? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 3. Suddenly feeling or acting as if the stressful experience were actually happening again (as if you were actually back there reliving it)? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 4. Feeling very upset when something reminded you of the stressful experience? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 5. Having strong physical reactions when something reminded you of the stressful experience (for example, heart pounding, trouble breathing, sweating)? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 6. Avoiding memories, thoughts, or feelings related to the stressful experience? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 7. Avoiding external reminders of the stressful experience (for example, people, places, conversations, activities, objects, or situations)? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 8. Trouble remembering important parts of the stressful experience? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 9. Having strong negative beliefs about yourself, other people, or the world (for example, having thoughts such as: I am bad, there is something seriously wrong with me, no one can be trusted, the world is completely dangerous)? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 10. Blaming yourself or someone else for the stressful experience or what happened after it? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 11. Having strong negative feelings such as fear, horror, anger, guilt, or shame? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 12. Loss of interest in activities that you used to enjoy? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 13. Feeling distant or cut off from other people? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 14. Trouble experiencing positive feelings (for example, being unable to feel happiness or have loving feelings for people close to you)? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 15. Irritable behavior, angry outbursts, or acting aggressively? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 16. Taking too many risks or doing things that could cause you harm? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 17. Being super alert or watchful or on guard? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 18. Feeling jumpy or easily startled? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 19. Having difficulty concentrating? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 20. Trouble falling or staying asleep? | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

References

- Lee, M.B. Report of the National Suicide Prevention Center in 2019. Available online: https://dep.mohw.gov.tw/domhaoh/lp-4905-107.html/ (accessed on 20 May 2021).

- Student Guide to Surviving Stress and Anxiety in College and Beyond. Available online: https://www.learnpsychology.org/student-stress-anxiety-guide/ (accessed on 10 May 2021).

- Yeh, Y.X. Survey of Life Changes and Mood during the COVID-19 Epidemic. Available online: http://www.etmh.org/CustomPage/HtmlEditorPage.aspx?MId=1346&ML=3/ (accessed on 20 May 2021).

- Burnette, C.; Ramchand, R.; Ayer, L. Gatekeeper training for suicide prevention: A theoretical model and review of the empirical literature. Rand Health Q. 2015, 5, 16. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Treanor, M.; Craske, M.G. Exposure therapy. In Encyclopedia of Mental Health, 2nd ed.; Friedman, H.S., Ed.; Academic Press: Oxford, UK, 2016; pp. 181–185. [Google Scholar]

- German, R.E.; DeRubeis, R.J. Cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy. In Encyclopedia of Mental Health, 2nd ed.; Friedman, H.S., Ed.; Academic Press: Oxford, UK, 2016; pp. 297–306. [Google Scholar]

- Arch, J.J.; Ayers, C.R.; Baker, A.; Almklov, E.; Dean, D.J.; Craske, M.G. Randomized clinical trial of adapted mindfulness-based stress reduction versus group cognitive behavioral therapy for heterogeneous anxiety disorders. Behav. Res. Ther. 2013, 51, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krisnanda, V.D. Effectiveness of managing emotion techniques in group counseling to prevent aggressiveness of high school students. Sosio e-Kons 2019, 11, 108–114. [Google Scholar]

- Dami, Z.A.; Setiawan, I.; Sudarmanto, G.; Lu, Y. Effectiveness of group counseling on depression, anxiety, stress and components of spiritual intelligence in student. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Res. 2019, 8, 236–243. [Google Scholar]

- Putrikita, K.A.; Sari, E.P. Group counseling to reduce academic stress in senior high school students. Konselor 2020, 9, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taufik, T. Implementing group counseling to change student’s insight pattern about learning in the COVID-19 pandemic. JELITA 2021, 2, 59–68. [Google Scholar]

- Lent, R.W.; Hackett, G. Career self-efficacy: Empirical status and future directions. J. Vocat. Behav. 1987, 30, 347–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackett, G.; Betz, N.E. Self-efficacy perceptions and the career-related choices of college students. In Student Perceptions in the Classroom; Schunk, D.H., Meece, J.L., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1992; pp. 229–246. [Google Scholar]

- Aliem, N.; Sugiharto, D.Y.P.; Awalya, A. Group counseling with cognitive restructuring technique to improve the self-efficacy and assertiveness of students who experienced advanced study anxiety. J. Bimbing. Konseling 2019, 8, 106–112. [Google Scholar]

- Persky, S. Employing immersive virtual environments for innovative experiments in health care communication. Patient Educ. Couns. 2011, 82, 313–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhang, Q.; Karunanithi, M.; Kang, C. Immersive augmented reality (I am real)—Remote clinical consultation. In 2019 IEEE EMBS International Conference on Biomedical & Health Informatics (BHI); IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Trappey, A.; Trappey, C.V.; Chang, C.M.; Tsai, M.C.; Kuo, R.R.; Lin, A.P. Virtual reality exposure therapy for driving phobia disorder (2): System refinement and verification. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czech, O.; Wrzeciono, A.; Rutkowska, A.; Guzik, A.; Kiper, P.; Rutkowski, S. Virtual reality interventions for needle-related procedural pain, fear and anxiety—A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 3248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piech, J.; Czernicki, K. Virtual reality rehabilitation and exergames—Physical and psychological impact on fall prevention among the elderly—A literature review. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 4098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamkuimo, S.A.; Girard, B.; Menelas, B.-A.J. A narrative review of virtual reality applications for the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 6683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darcy, A.; Daniels, J.; Salinger, D.; Wicks, P.; Robinson, A. Evidence of human-level bonds established with a digital conversational agent: Cross-sectional, retrospective observational study. JMIR Form. Res. 2021, 5, e27868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzpatrick, K.K.; Darcy, A.; Vierhile, M. Delivering cognitive behavior therapy to young adults with symptoms of depression and anxiety using a fully automated conversational agent (Woebot): A randomized controlled trial. JMIR Ment. Health 2017, 4, e7785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, M. A study of chatbot personality based on the purposes of chatbot. J. Korea Contents Assoc. 2018, 18, 319–329. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, J.; Chen, Z.; Zhou, K.; Yu, C. A deep learning based chatbot for campus psychological therapy. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1910.06707. [Google Scholar]

- Tsaramirsis, G.; Buhari, S.M.; Al-Shammari, K.O.; Ghazi, S.; Nazmudeen, M.S.; Tsaramirsis, K. Towards simulation of the classroom learning experience: Virtual reality approach. In Proceedings of the 2016 3rd International Conference on Computing for Sustainable Global Development (INDIACom), New Delhi, India, 16–18 March 2016; pp. 1343–1346. [Google Scholar]

- Dibitonto, M.; Leszczynska, K.; Tazzi, F.; Medaglia, C.M. In Chatbot in a campus environment: Design of LiSA, a virtual assistant to help students in their university life. In Human-Computer Interaction. Interaction Technologies. HCI 2018; Kurosu, M., Ed.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 103–116. [Google Scholar]

- Stanica, I.; Dascalu, M.I.; Bodea, C.N.; Moldoveanu, A.D.B. VR job interview simulator: Where virtual reality meets artificial intelligence for education. In Proceedings of the 2018 Zooming Innovation in Consumer Technologies Conference (ZINC), Novi Sad, Serbia, 30–31 May 2018; pp. 9–12. [Google Scholar]

- 18 Student Stress Survey Questions For Questionnaire + Template. Available online: https://www.questionpro.com/survey-templates/student-stress/ (accessed on 13 April 2021).

- PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) 2018. Available online: https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assessment/adult-sr/ptsd-checklist.asp/ (accessed on 20 May 2021).

- Morrison, K.; Su, S.; Keck, M.; Beidel, D.C. Psychometric properties of the PCL-5 in a sample of first responders. J. Anxiety Disord. 2021, 77, 102339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iacobucci, D.; Posavac, S.S.; Kardes, F.R.; Schneider, M.J.; Popovich, D.L. The median split: Robust, refined, and revived. J. Consum. Psychol. 2015, 25, 690–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stress in College Students for 2019: (How to Cope). Available online: https://www.stress.org/stress-in-college-students-for-2019-how-to-cope/ (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- Manage Stress: Strengthen Your Support Network. Available online: https://www.apa.org/topics/stress/manage-social-support/ (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- Lessen Your Stress. Available online: https://bewell.stanford.edu/lessen-your-stress/ (accessed on 30 August 2021).

- Healthy Relationships—Strategies to Cope with Family Stress. Available online: https://www.canr.msu.edu/news/strategies_to_cope_with_family_stress/ (accessed on 30 August 2021).

| Domain: Virtual Reality Immersive Technology and Group Counseling | |

|---|---|

| Keyword combinations | Virtual reality + Group counseling (442 outcomes) Virtual reality + Group consultation (711 outcomes) Virtual reality + Psychological service (2412 outcomes) |

| Number of patents | 3178 |

| IPC | G06F, G06Q, A61B, G09B, G06T, A61M |

| Application years | 1991~2021 |

| Patent database | Innovation Q+ |

| Source of Stress | Suggestions |

|---|---|

| Studies | Focus on getting your education instead of getting certain grades. Get enough sleep. Work on time management skills. |

| Financial | Always keep in mind why you want to pursue a degree in the first place, and remind yourself that it can lead to better job opportunities after you graduate. Experts and employers still believe that college is worth the investment. |

| Family | Take time to do something that is meaningful, relaxing and fun to you and your family. Consider the emotional needs of your family members. Focus on your health and the health of others in your family. |

| Friends | Make an effort to only befriend people whose company you enjoy. Spend time with people with whom you have a good relationship. |

| Work | Establish some work-life boundaries for yourself. That might mean making a rule not to check email from home in the evening or not answering the phone during dinner. |

| Health | If a particular illness is going around your campus or community, try your best to avoid contact with anyone who is contagious and wash your hands frequently. Everyone gets sick on occasion. Accept that you might get ill even though you try not to. If you do catch something, take care of yourself and rest as much as possible before resuming your normal activities. |

| Activity | Pursue a new hobby. |

| In the Past Month, How Much Were You Bothered by: | Avg. | S.D. | Number of Participants ≥ 3 Points |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Repeated, disturbing, and unwanted memories of a stressful experience? | 1.29 | 1.13 | 18 |

| 2. Repeated, disturbing dreams of a stressful experience? | 0.97 | 1.09 | 12 |

| 3. Suddenly feeling or acting as if the stressful experience were actually happening again (as if you were actually back there reliving it)? | 1.18 | 1.09 | 16 |

| 4. Feeling very upset when something reminded you of the stressful experience? | 1.79 | 1.09 | 30 |

| 5. Having strong physical reactions when something reminded you of the stressful experience (for example, heart pounding, trouble breathing, sweating)? | 1.00 | 1.11 | 16 |

| 6. Avoiding memories, thoughts, or feelings related to the stressful experience? | 1.58 | 1.12 | 25 |

| 7. Avoiding external reminders of the stressful experience (for example, people, places, conversations, activities, objects, or situations)? | 1.54 | 1.17 | 23 |

| 8. Trouble remembering important parts of the stressful experience? | 0.61 | 0.85 | 6 |

| 9. Having strong negative beliefs about yourself, other people, or the world (for example, having thoughts such as: I am bad, there is something seriously wrong with me, no one can be trusted, the world is completely dangerous)? | 1.38 | 1.29 | 27 |

| 10. Blaming yourself or someone else for the stressful experience or what happened after it? | 1.30 | 1.14 | 22 |

| 11. Having strong negative feelings such as fear, horror, anger, guilt, or shame? | 1.52 | 1.16 | 22 |

| 12. Loss of interest in activities that you used to enjoy? | 1.04 | 1.10 | 13 |

| 13. Feeling distant or cut off from other people? | 1.15 | 1.17 | 18 |

| 14. Trouble experiencing positive feelings (for example, being unable to feel happiness or feeling love for people close to you)? | 1.12 | 1.18 | 18 |

| 15. Irritable behavior, angry outbursts, or acting aggressively? | 0.96 | 1.12 | 15 |

| 16. Taking too many risks or doing things that could cause you harm? | 0.57 | 1.12 | 4 |

| 17. Being super-alert or watchful or on guard? | 0.86 | 1.07 | 11 |

| 18. Feeling jumpy or easily startled? | 0.85 | 1.08 | 12 |

| 19. Having difficulty concentrating? | 1.38 | 1.10 | 16 |

| 20. Trouble falling or staying asleep? | 1.48 | 1.26 | 27 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lin, A.P.C.; Trappey, C.V.; Luan, C.-C.; Trappey, A.J.C.; Tu, K.L.K. A Test Platform for Managing School Stress Using a Virtual Reality Group Chatbot Counseling System. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 9071. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11199071

Lin APC, Trappey CV, Luan C-C, Trappey AJC, Tu KLK. A Test Platform for Managing School Stress Using a Virtual Reality Group Chatbot Counseling System. Applied Sciences. 2021; 11(19):9071. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11199071

Chicago/Turabian StyleLin, Aislyn P. C., Charles V. Trappey, Chi-Cheng Luan, Amy J. C. Trappey, and Kevin L. K. Tu. 2021. "A Test Platform for Managing School Stress Using a Virtual Reality Group Chatbot Counseling System" Applied Sciences 11, no. 19: 9071. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11199071

APA StyleLin, A. P. C., Trappey, C. V., Luan, C.-C., Trappey, A. J. C., & Tu, K. L. K. (2021). A Test Platform for Managing School Stress Using a Virtual Reality Group Chatbot Counseling System. Applied Sciences, 11(19), 9071. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11199071