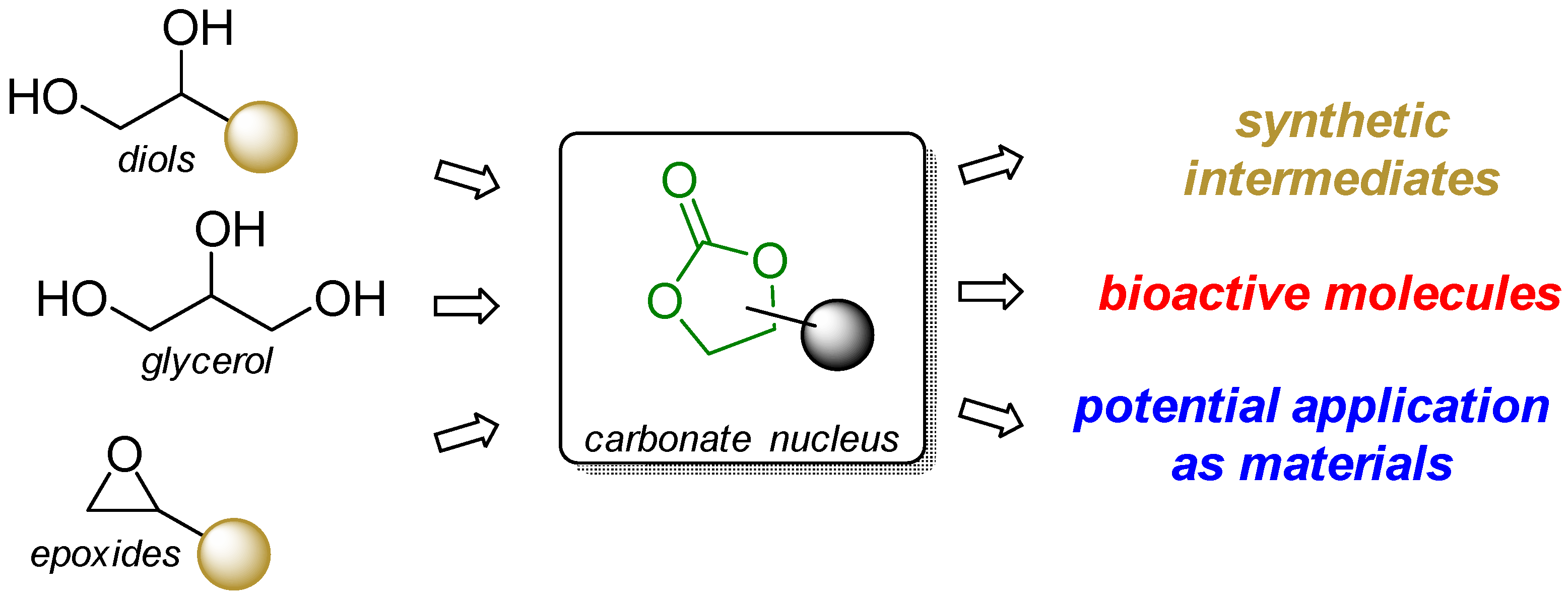

Five-Membered Cyclic Carbonates: Versatility for Applications in Organic Synthesis, Pharmaceutical, and Materials Sciences

Abstract

1. Introduction

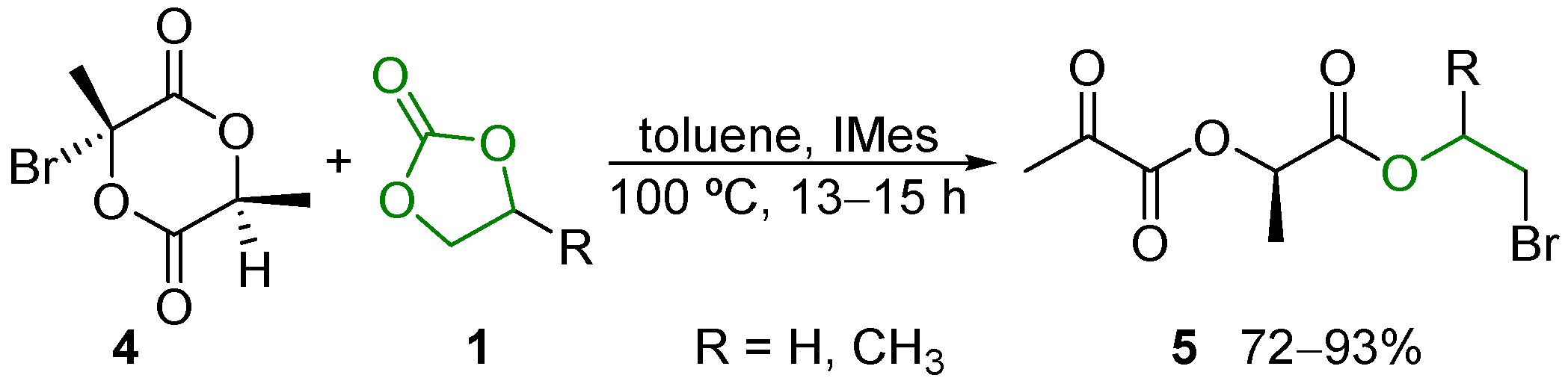

2. Applications in Chemistry

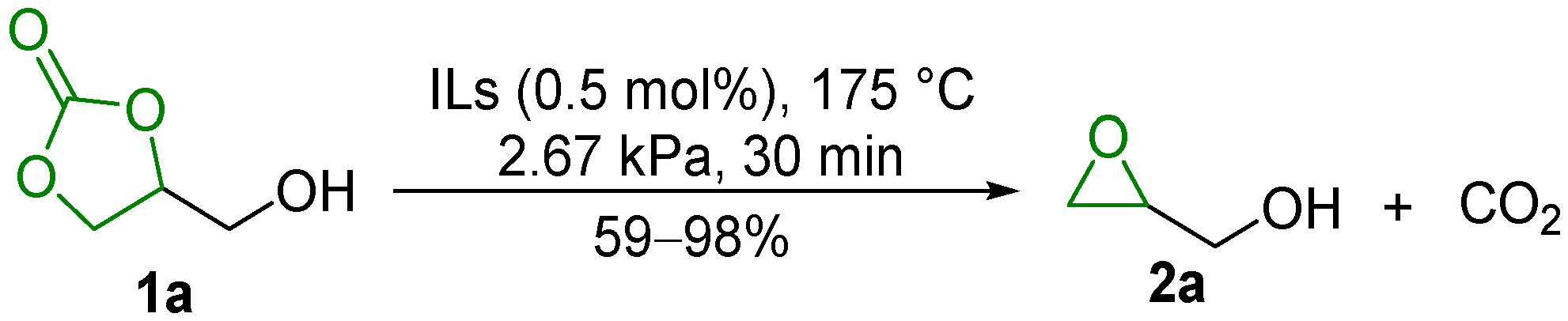

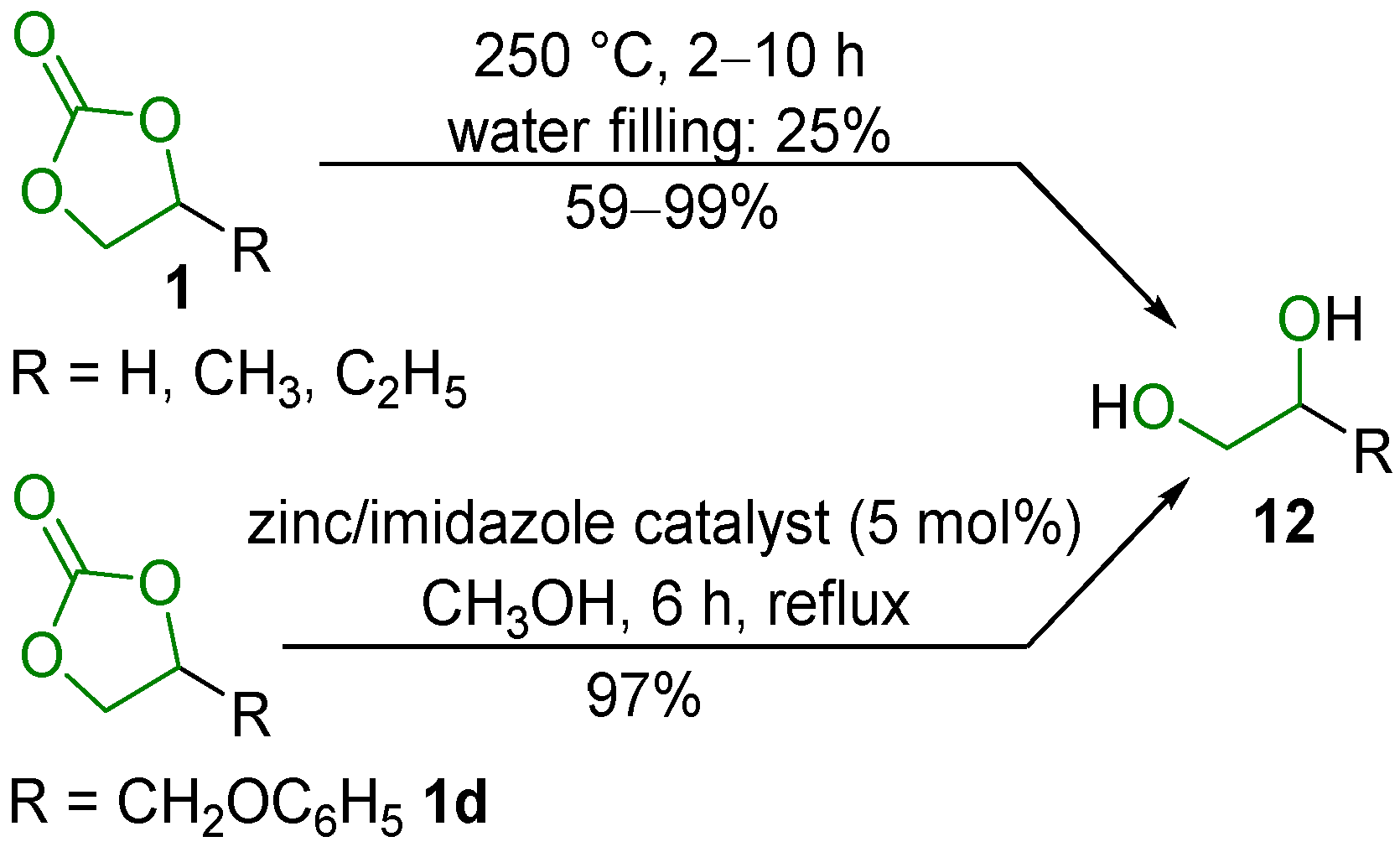

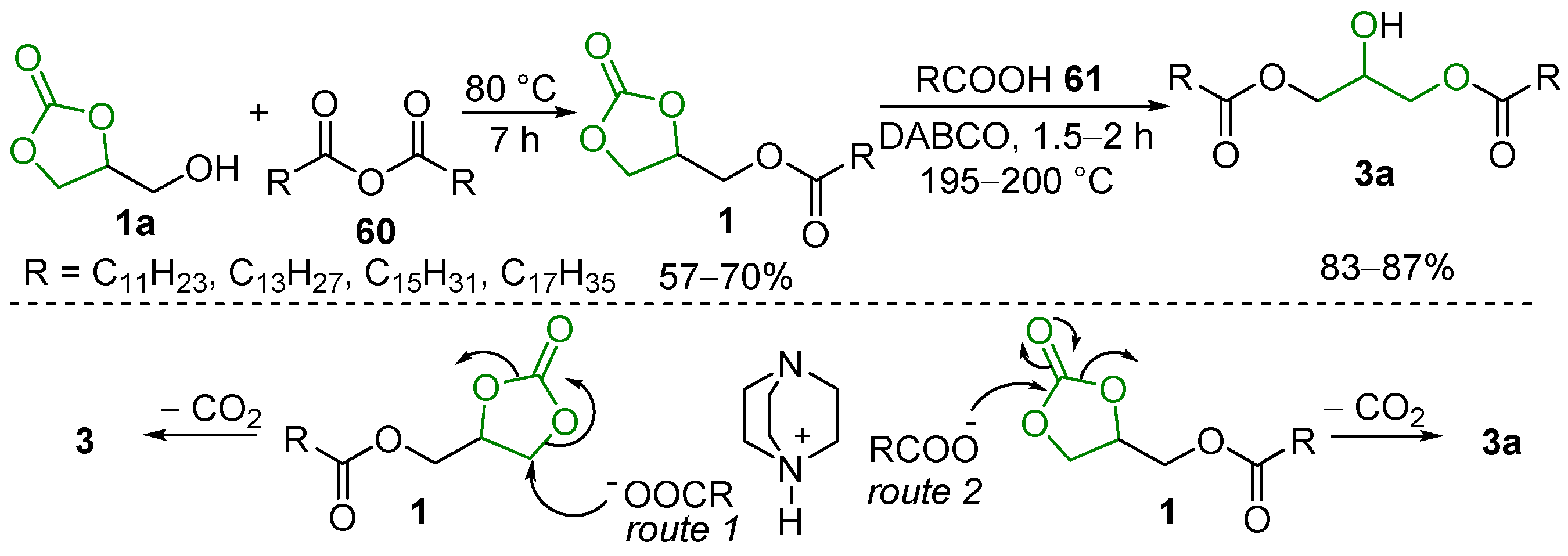

2.1. Decarboxylation of Cyclic Carbonates

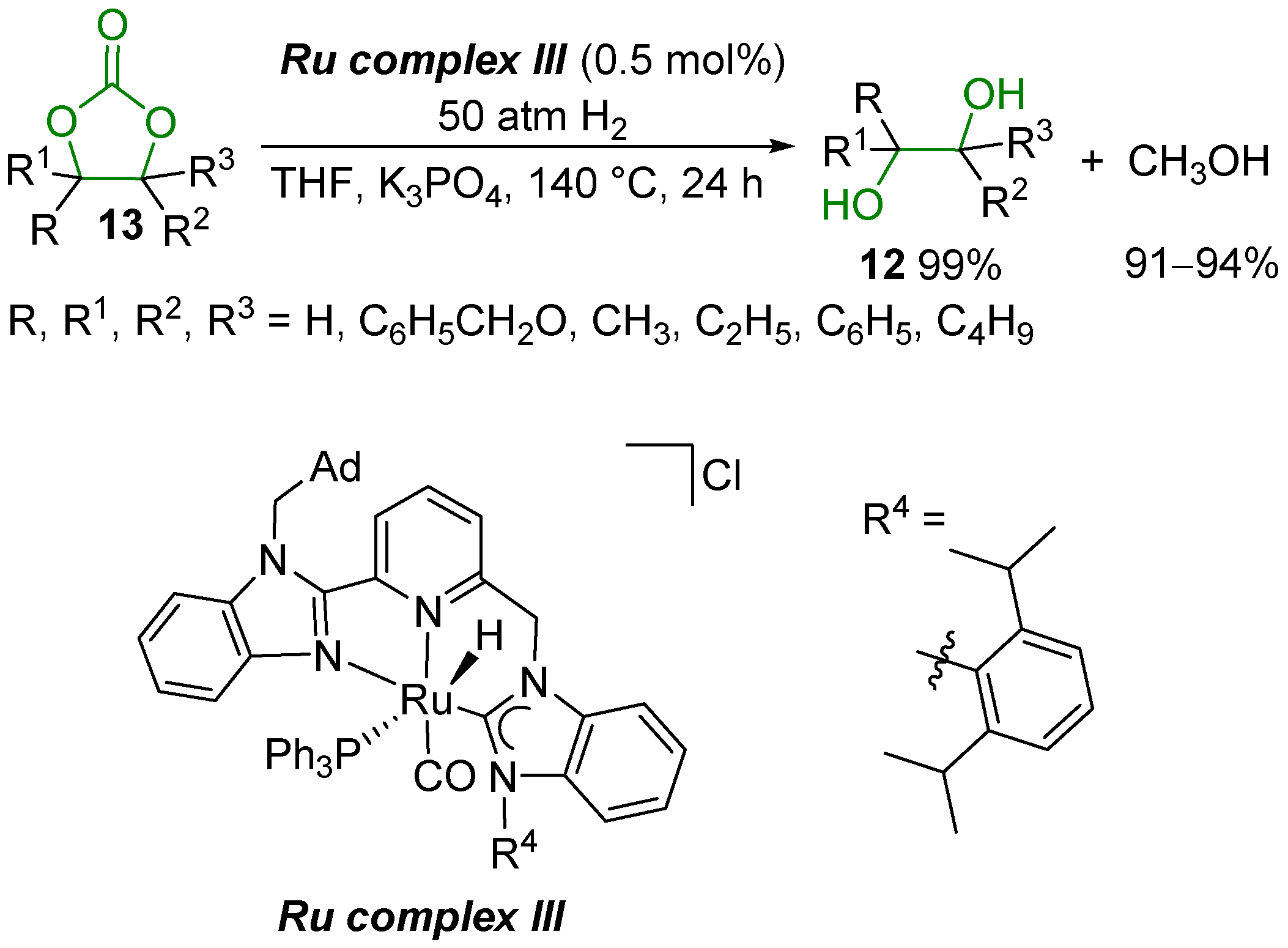

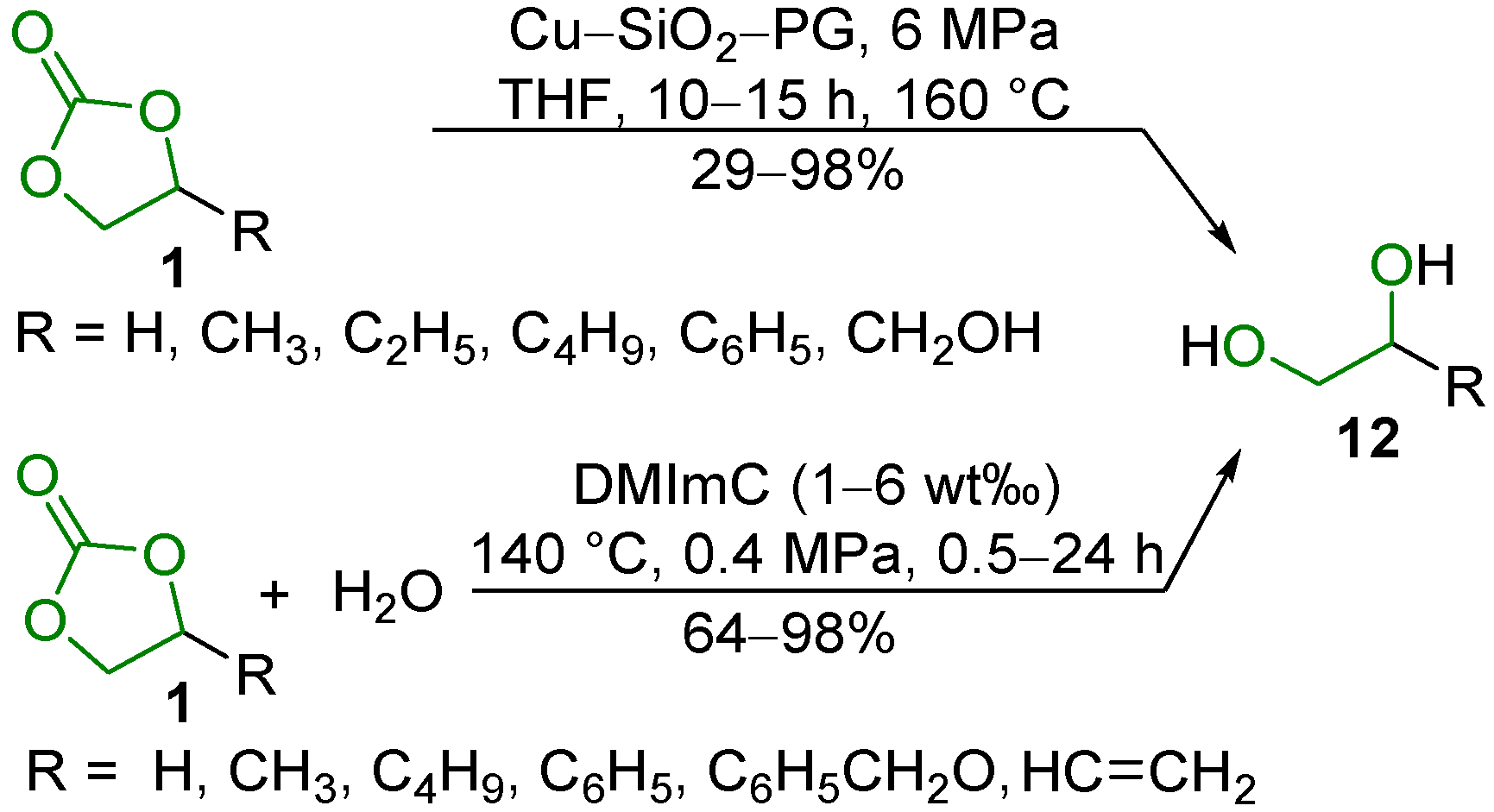

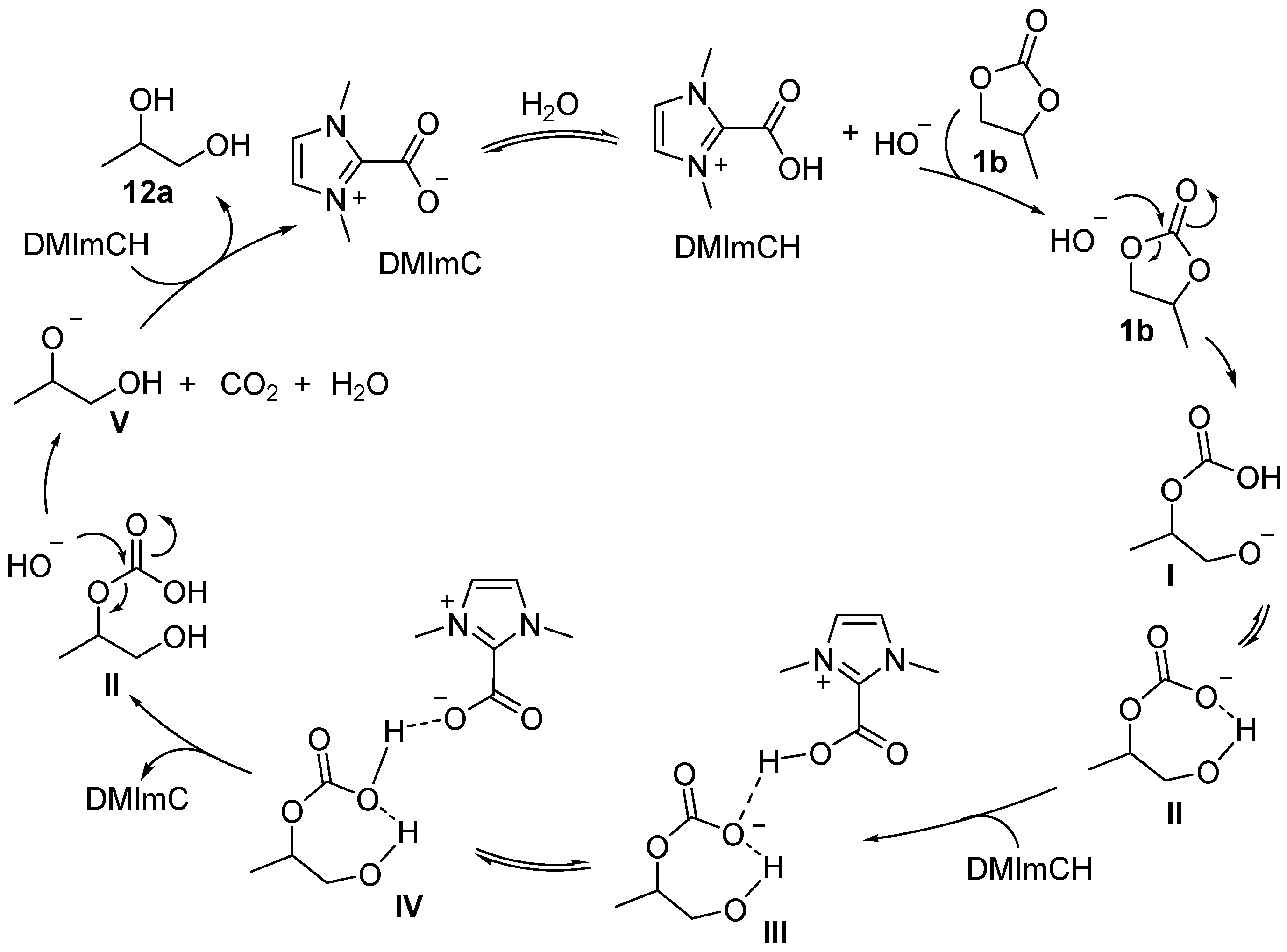

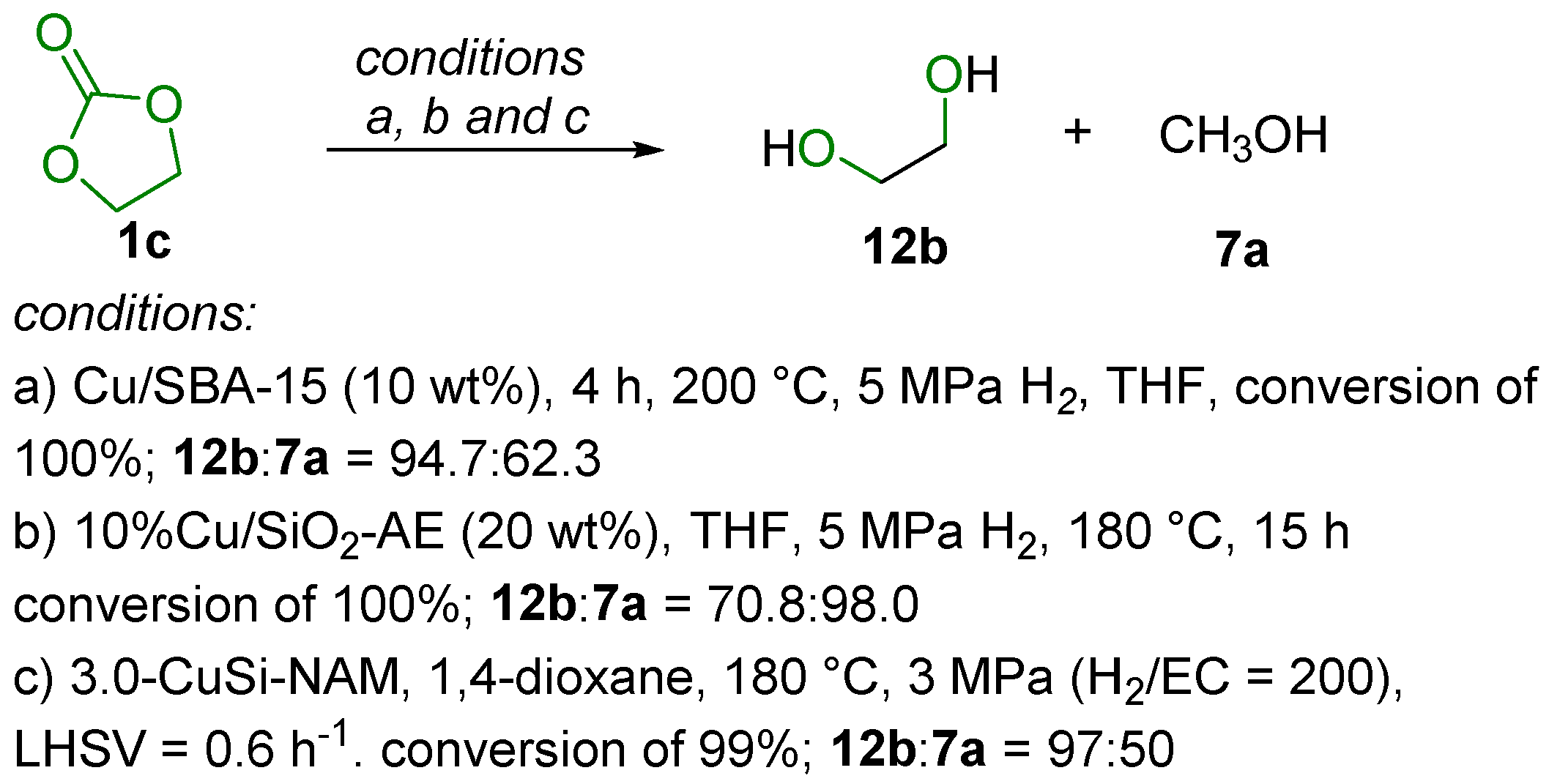

2.2. Hydrogenation Reaction

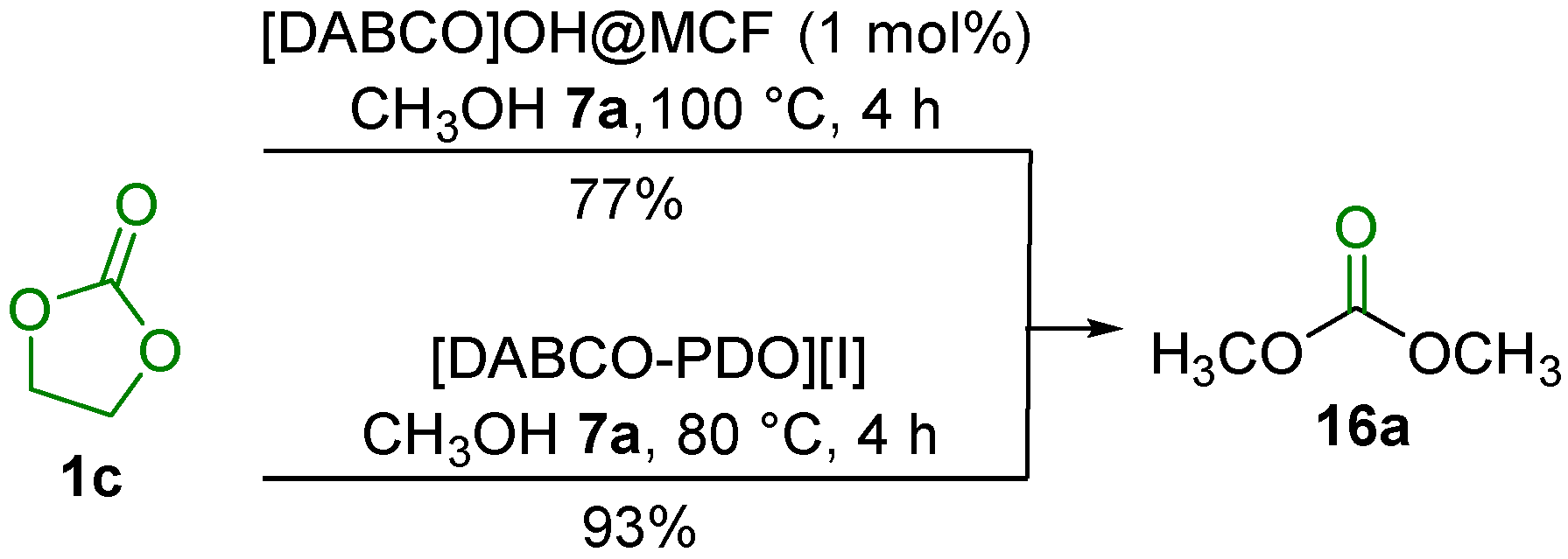

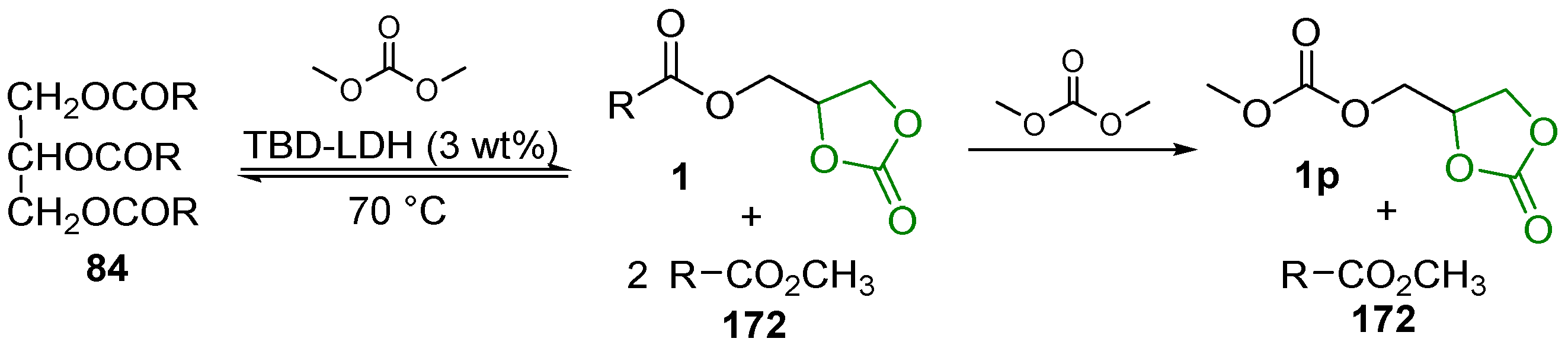

2.3. Transesterification of Cyclic Carbonates

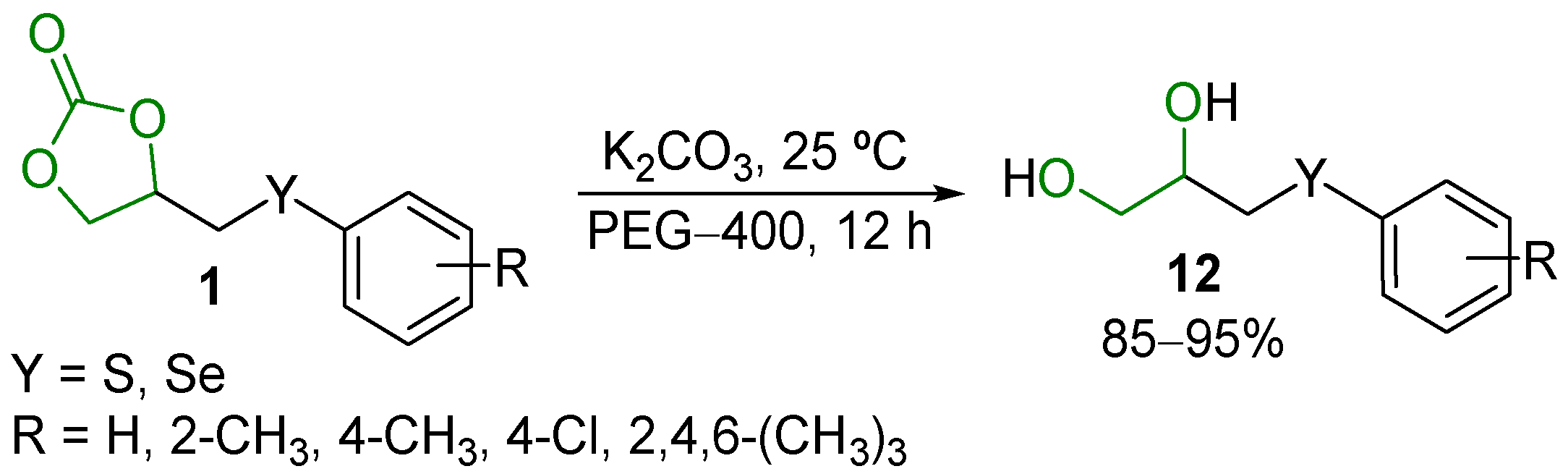

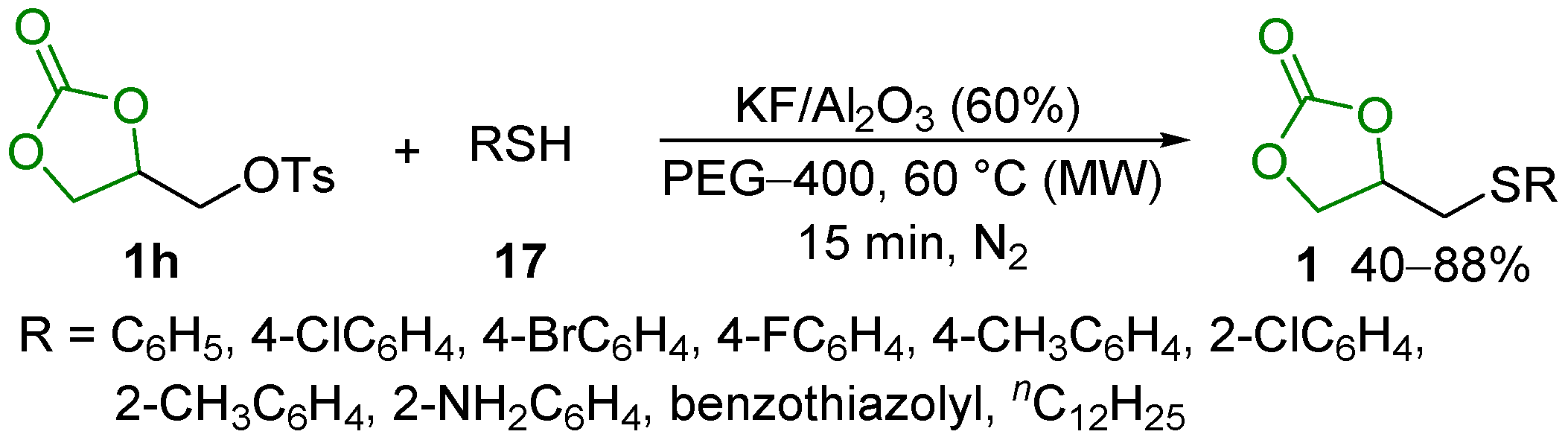

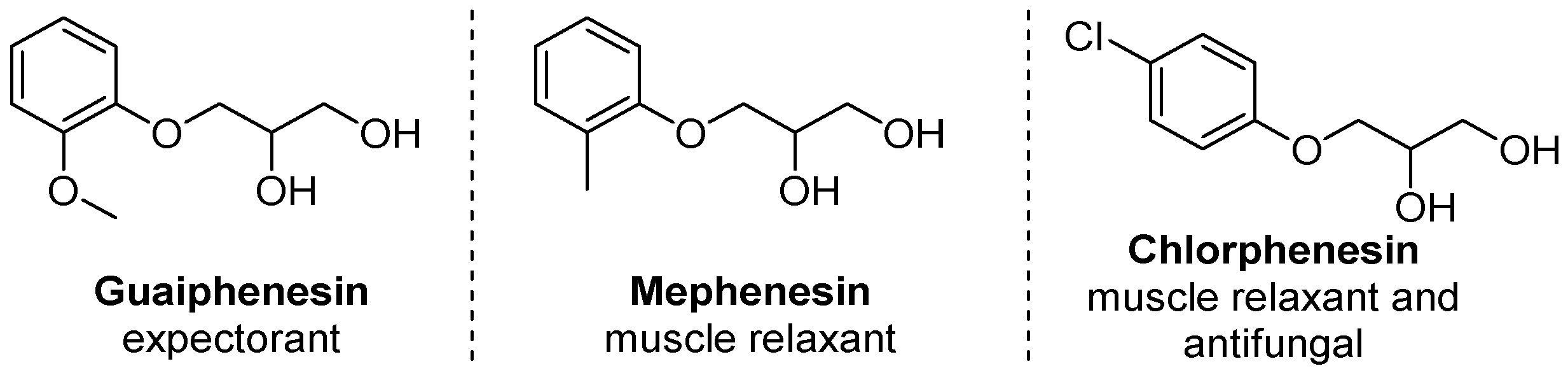

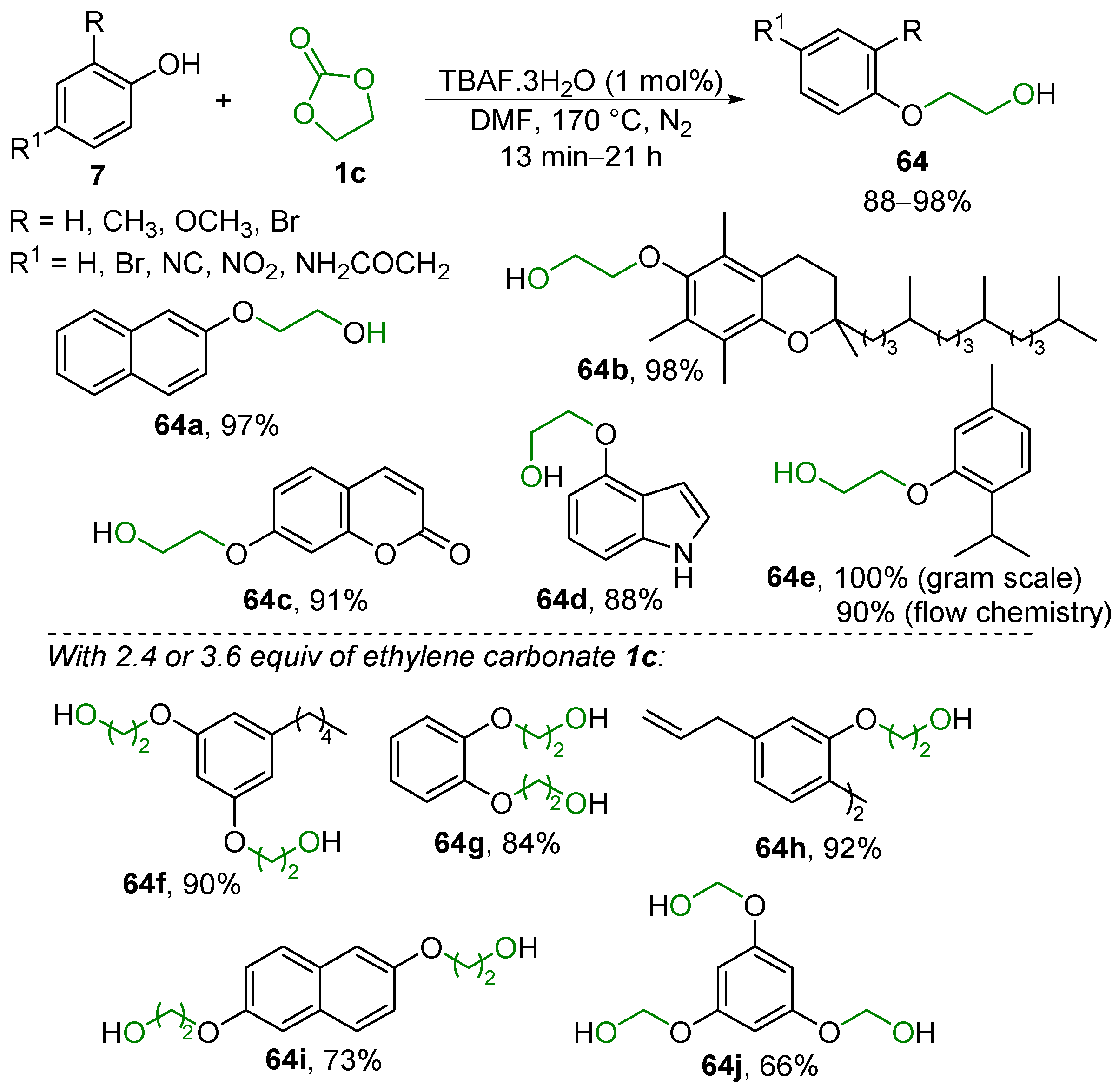

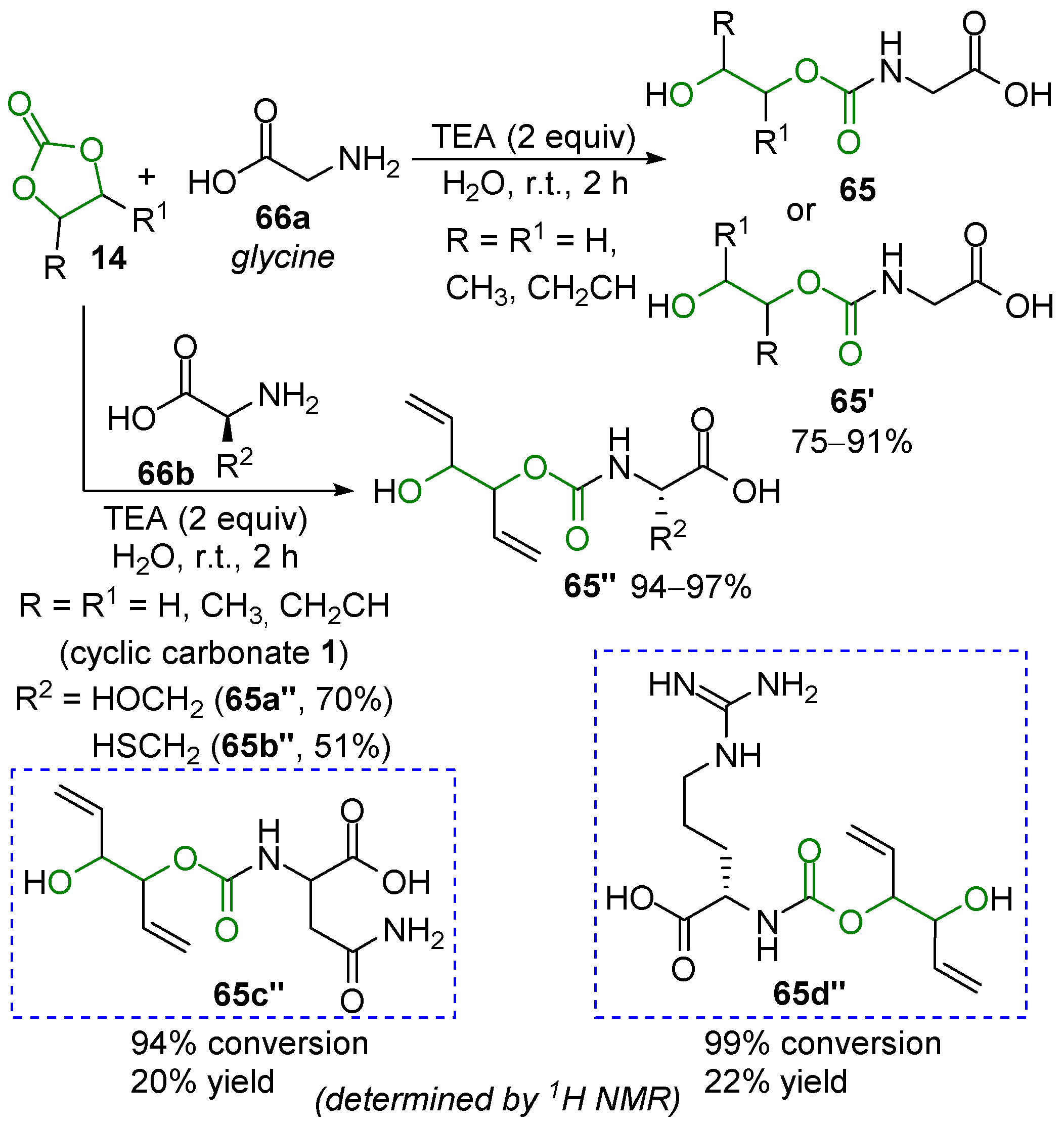

2.4. Substitution Reaction

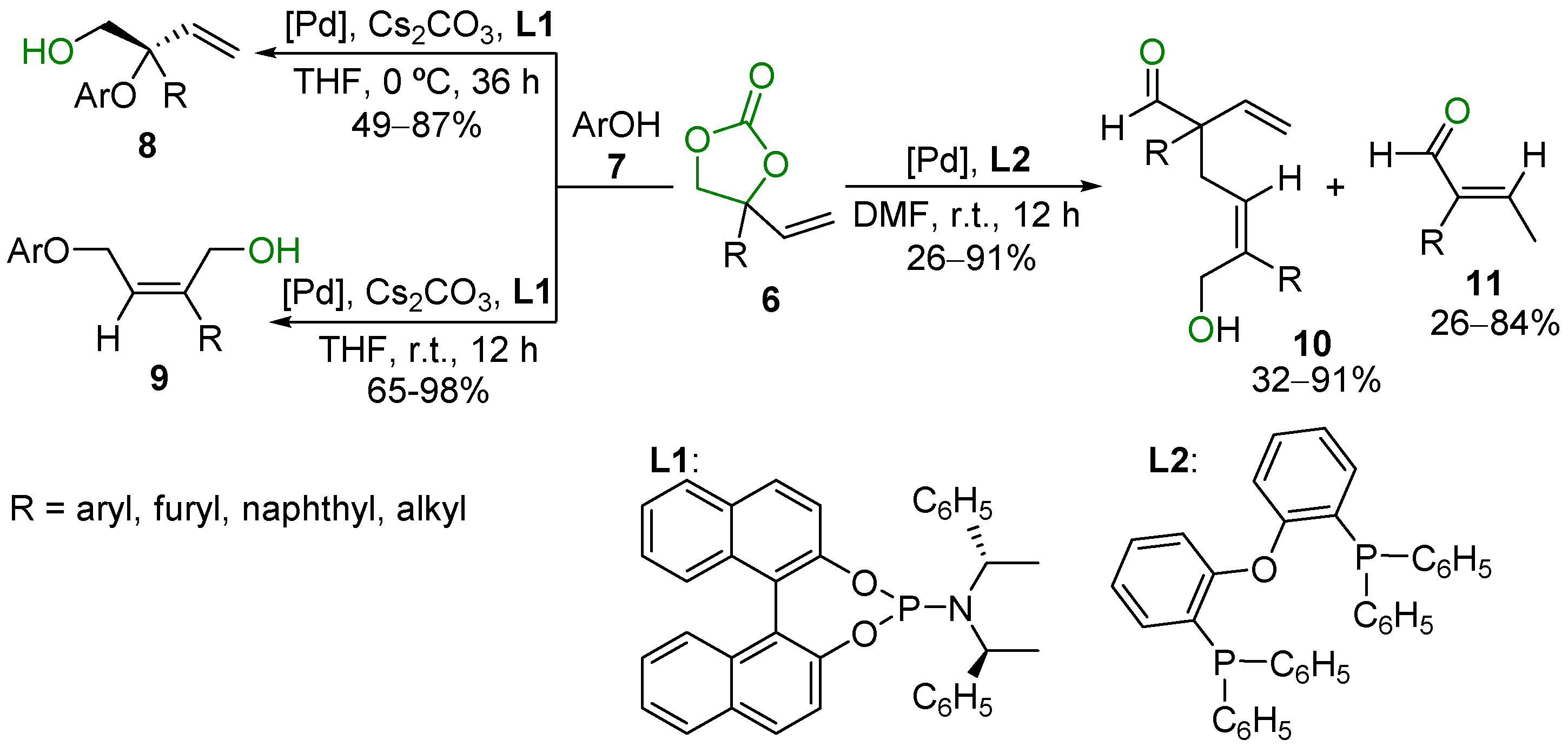

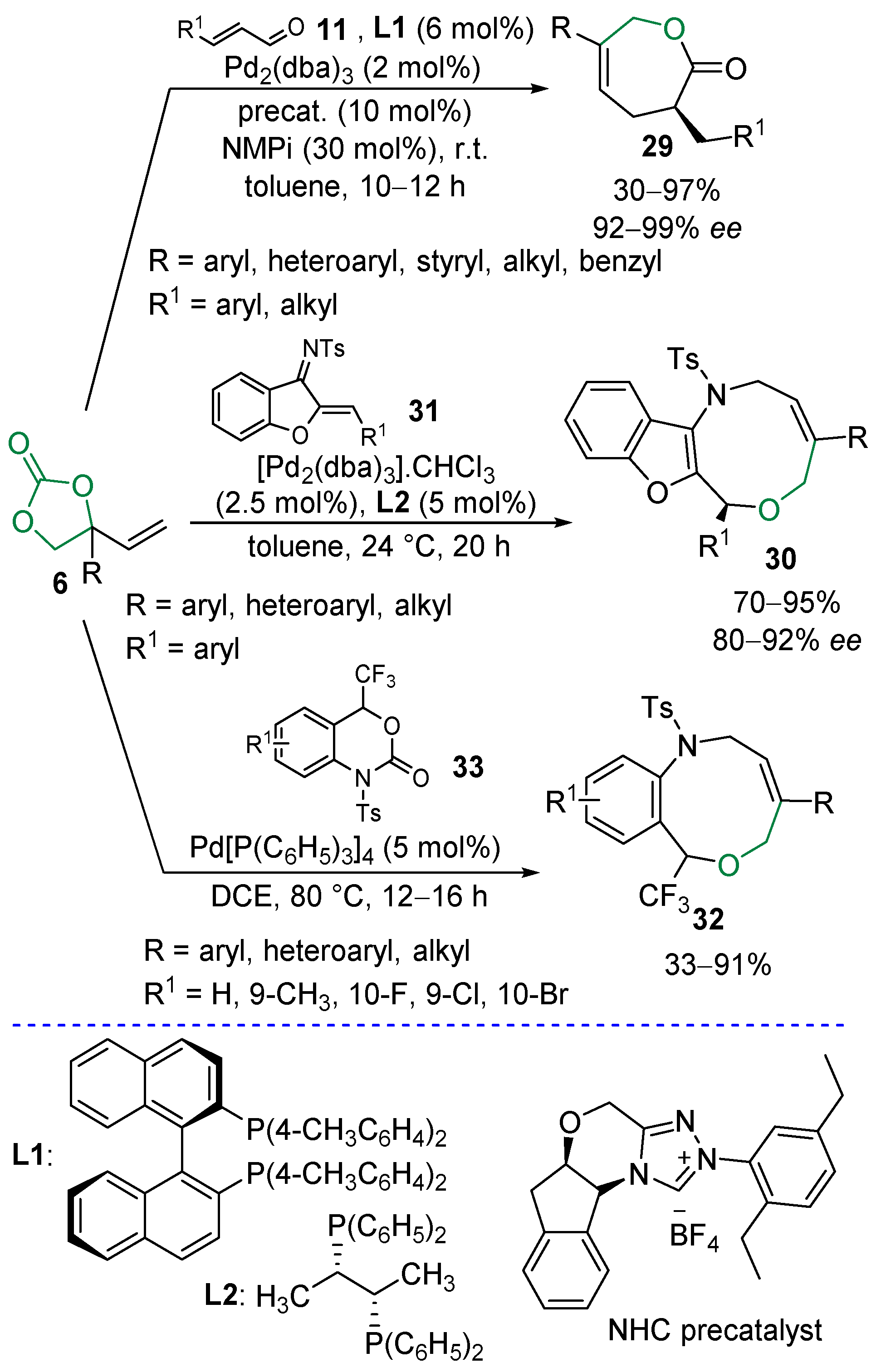

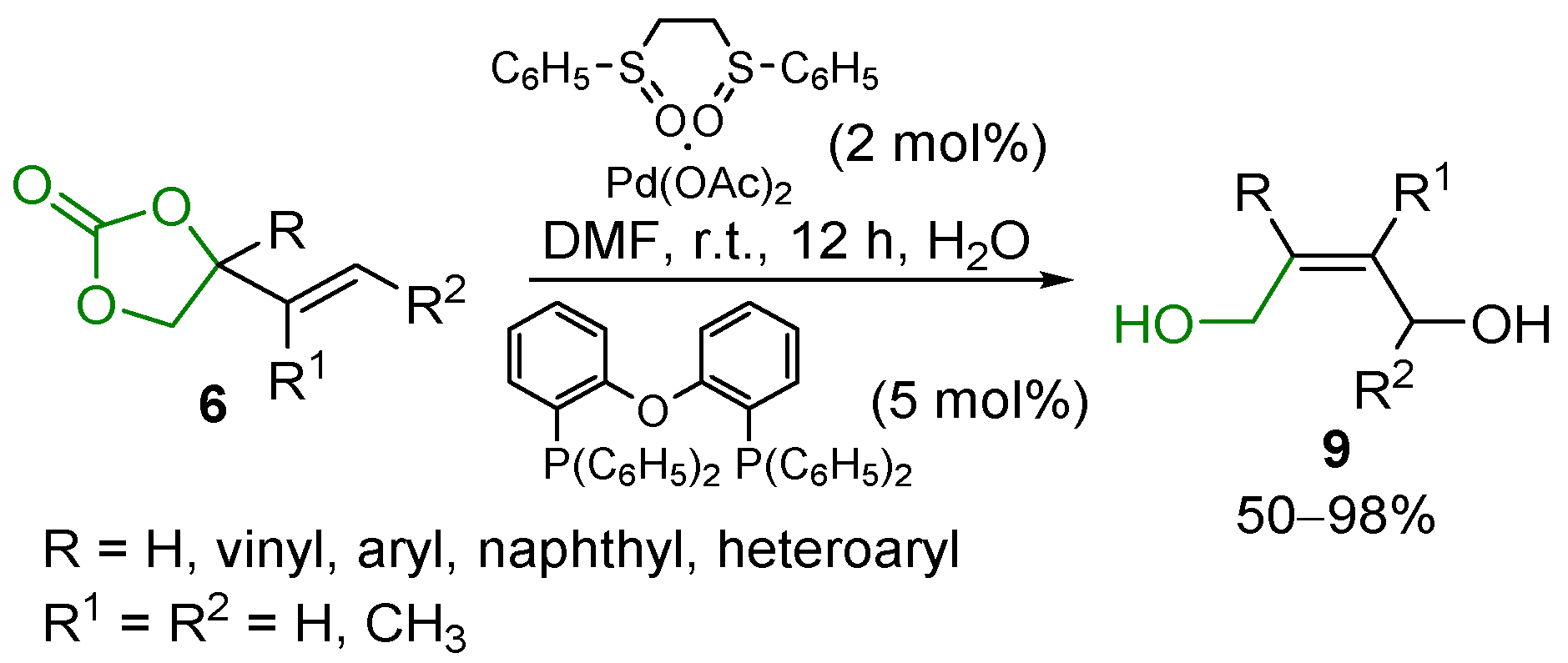

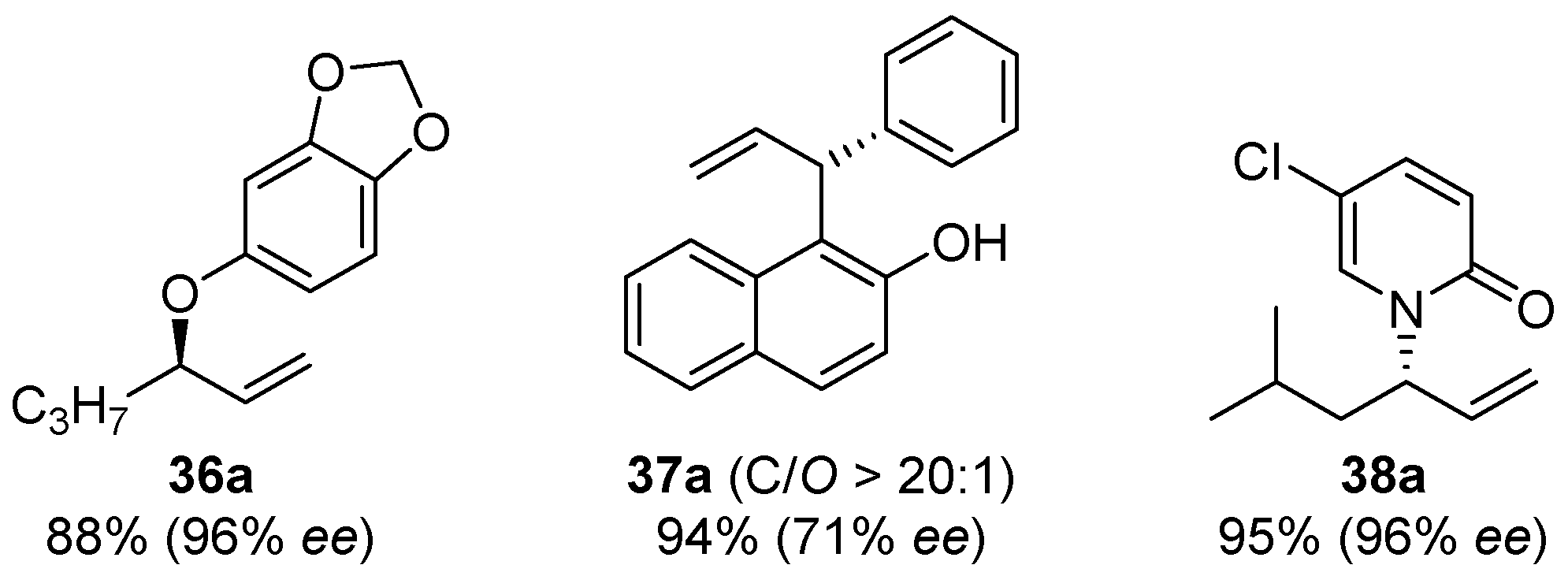

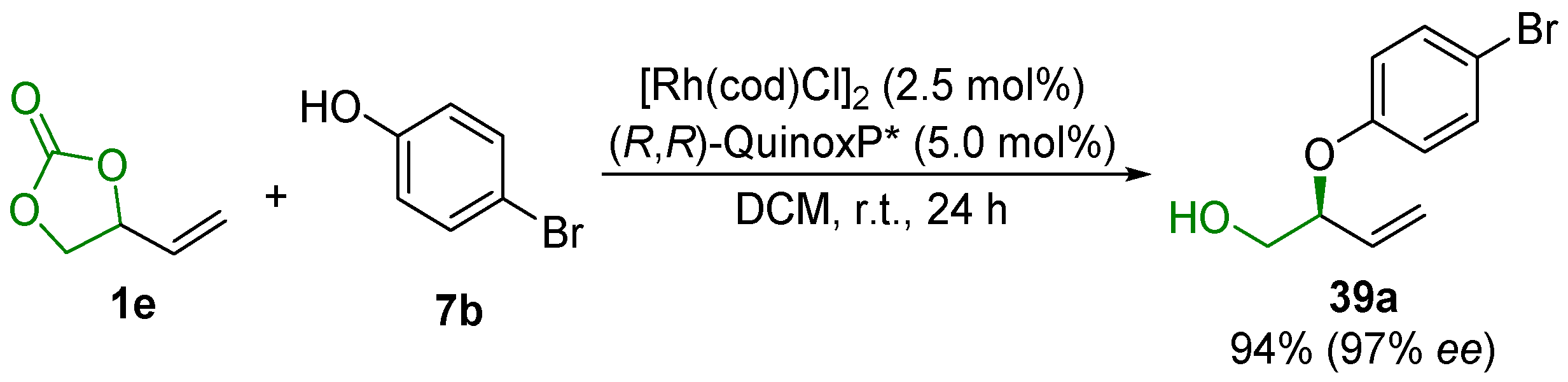

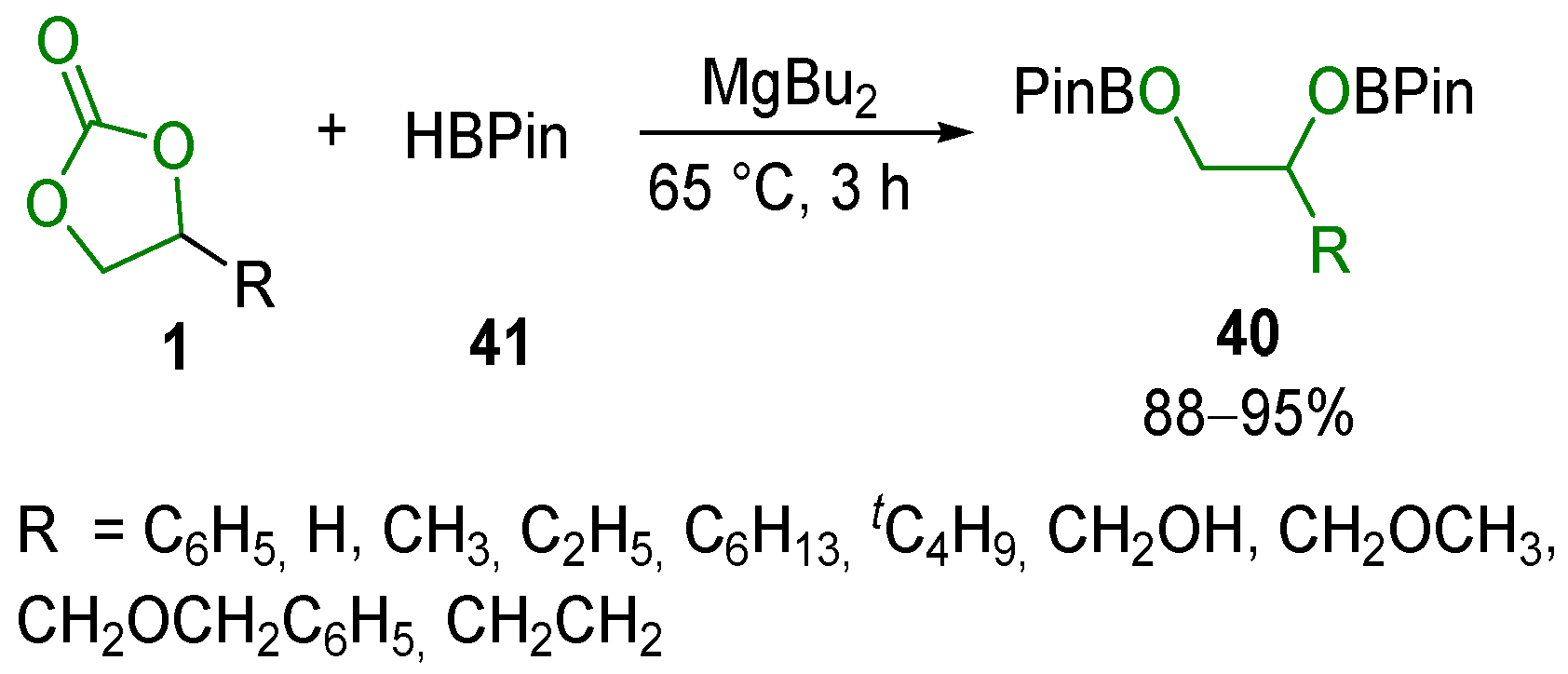

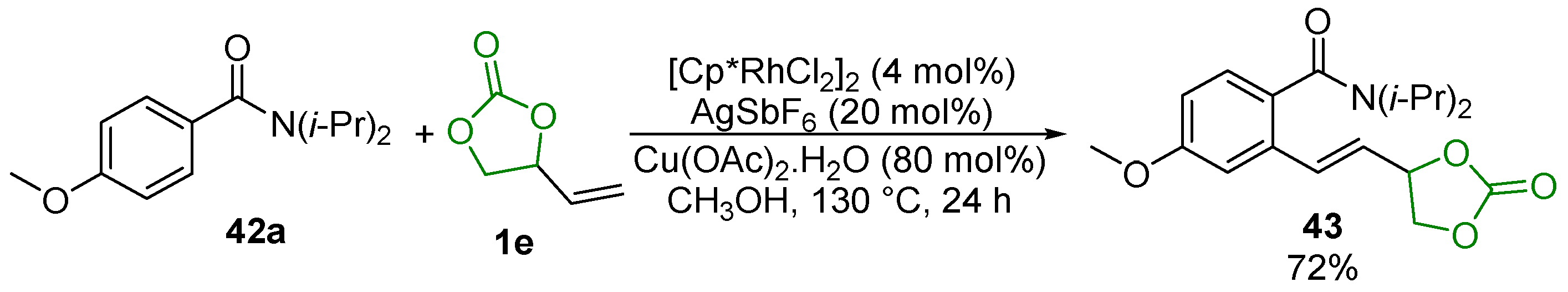

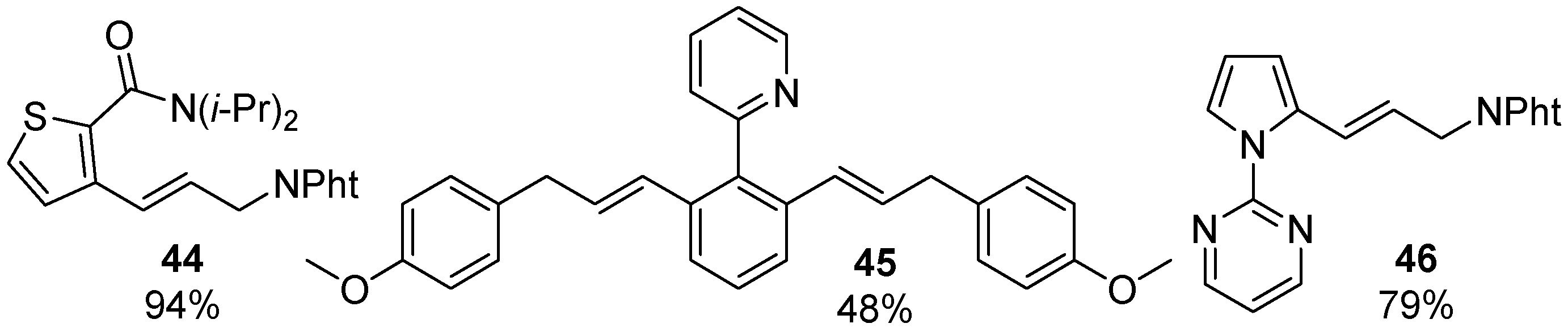

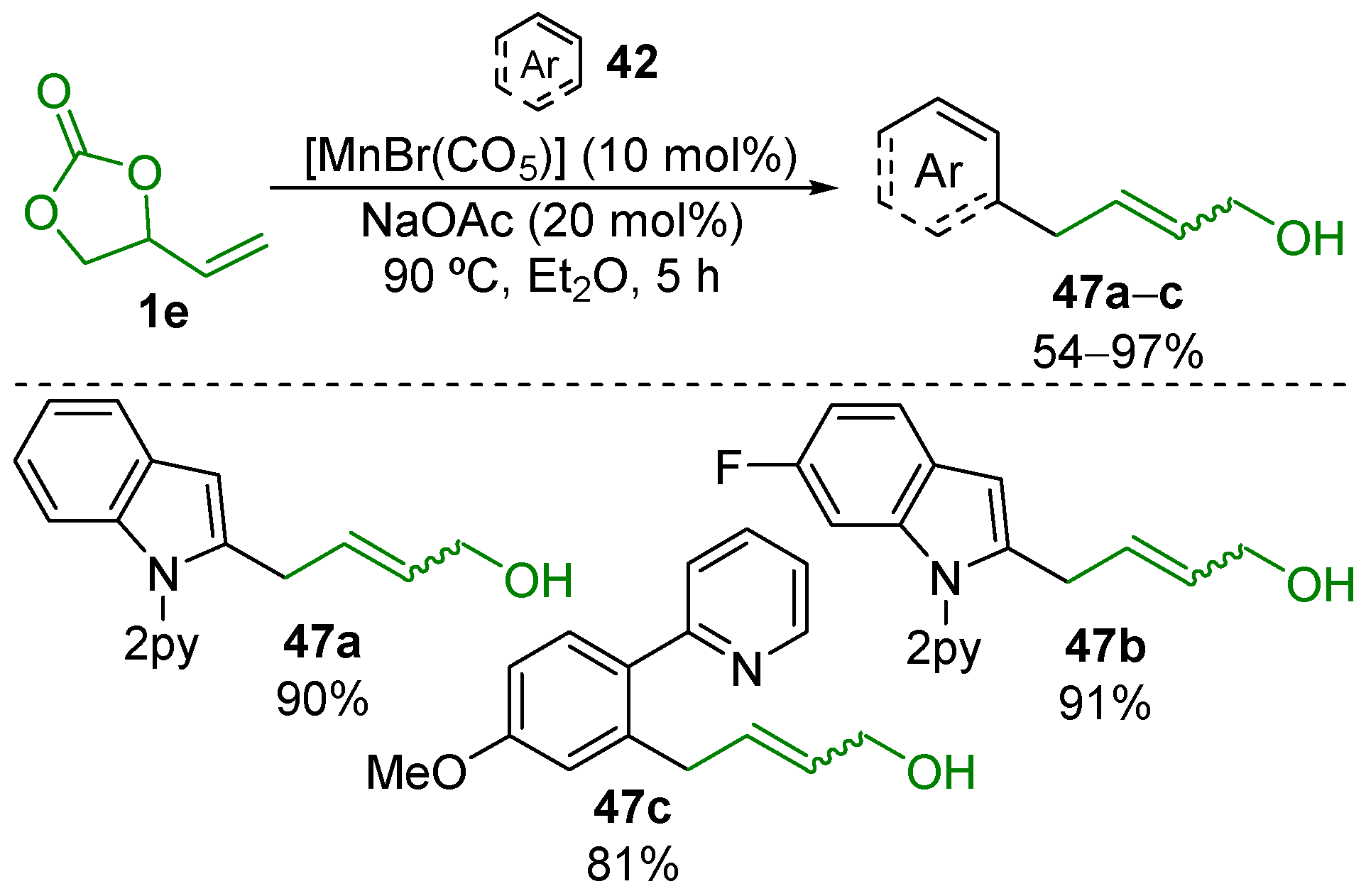

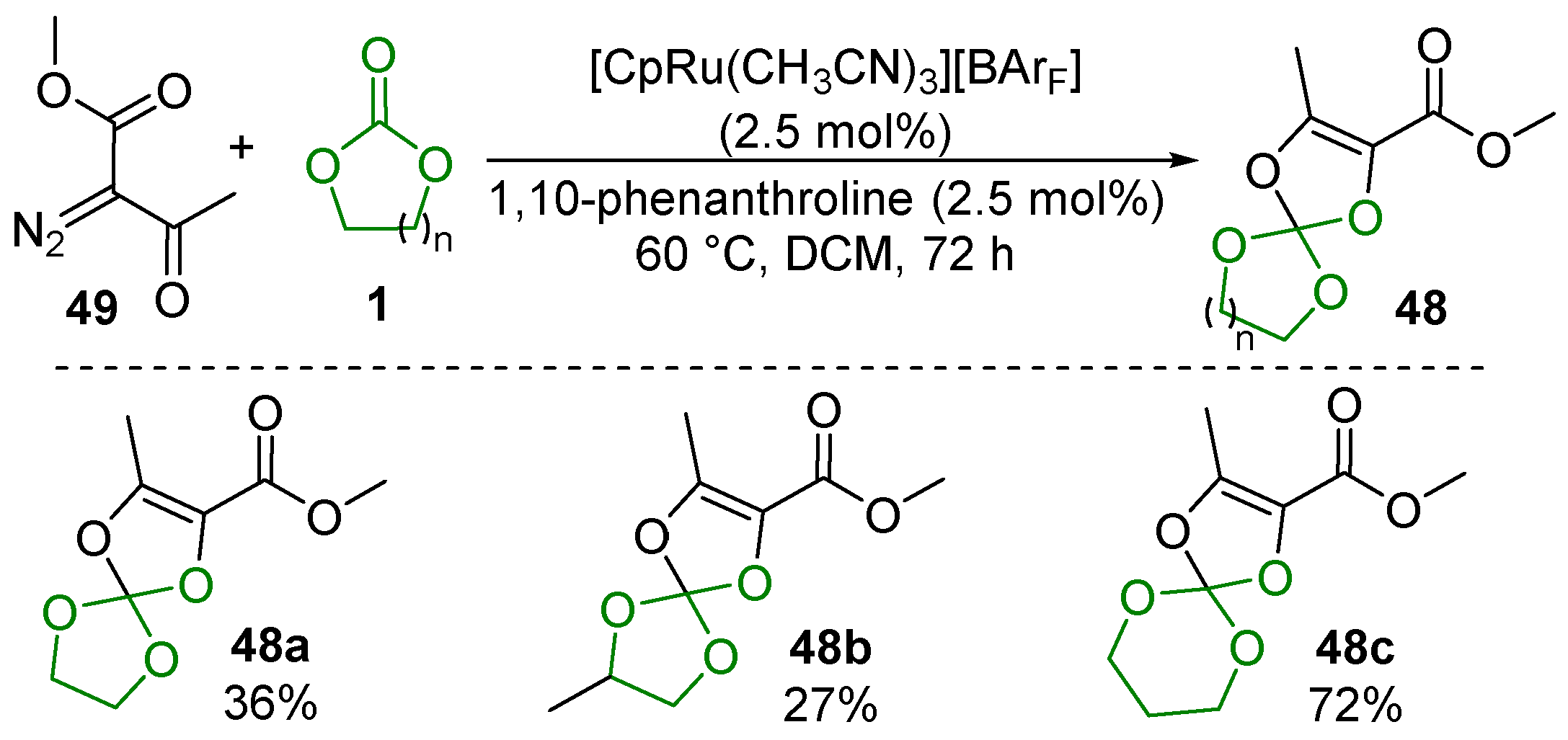

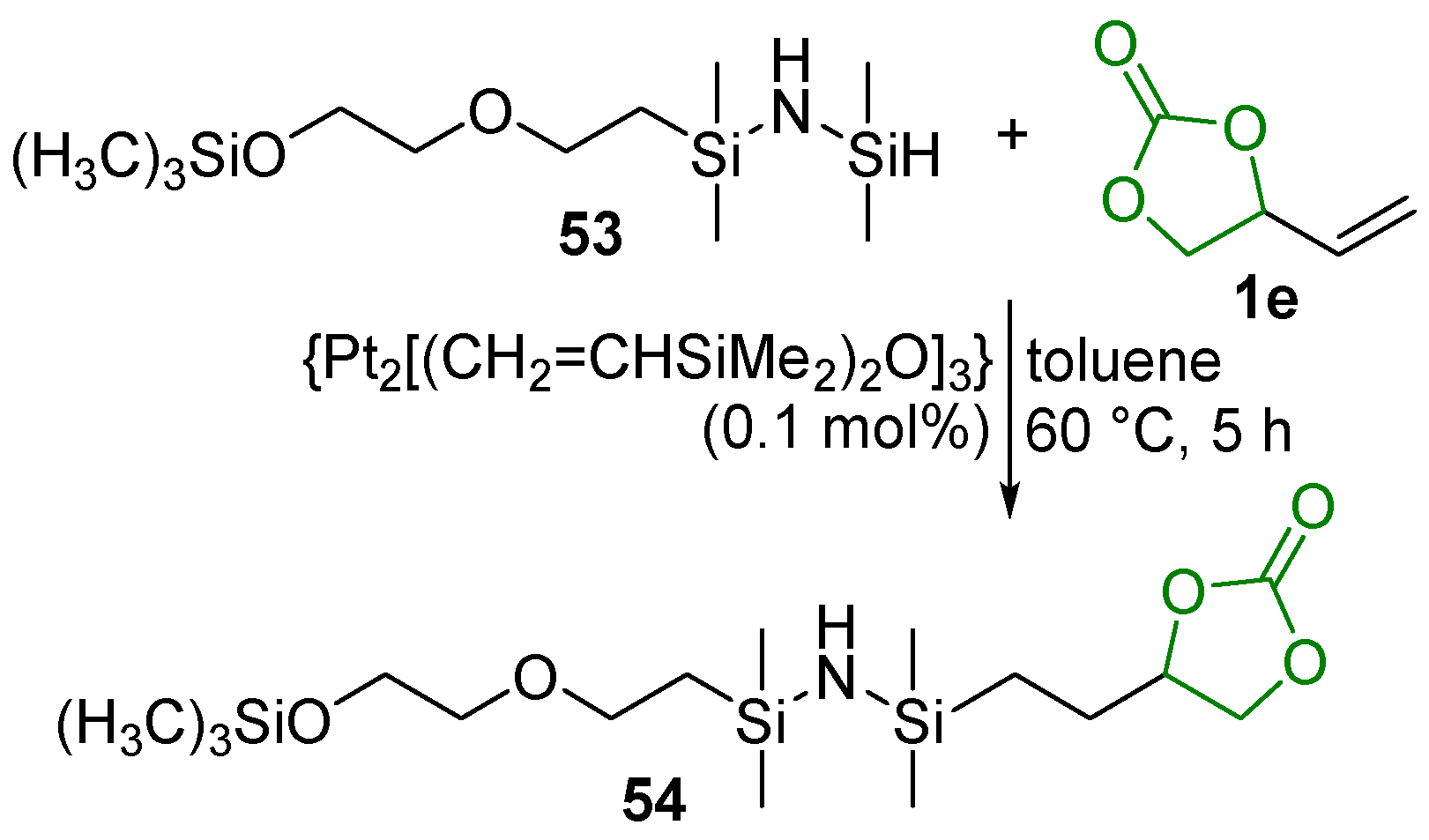

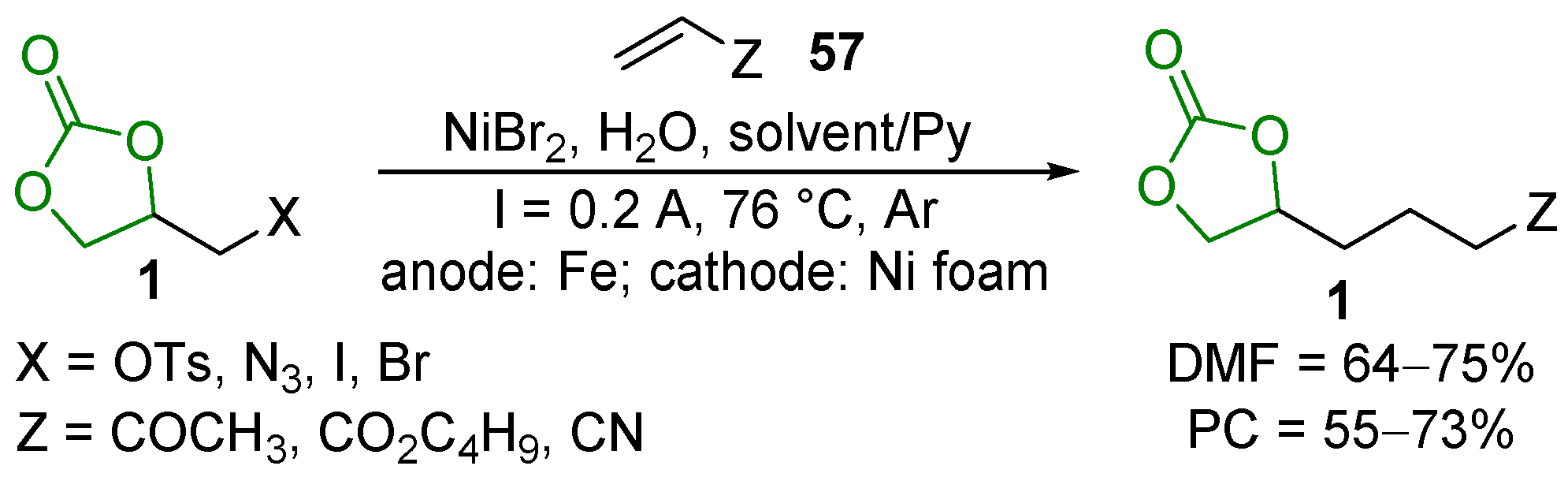

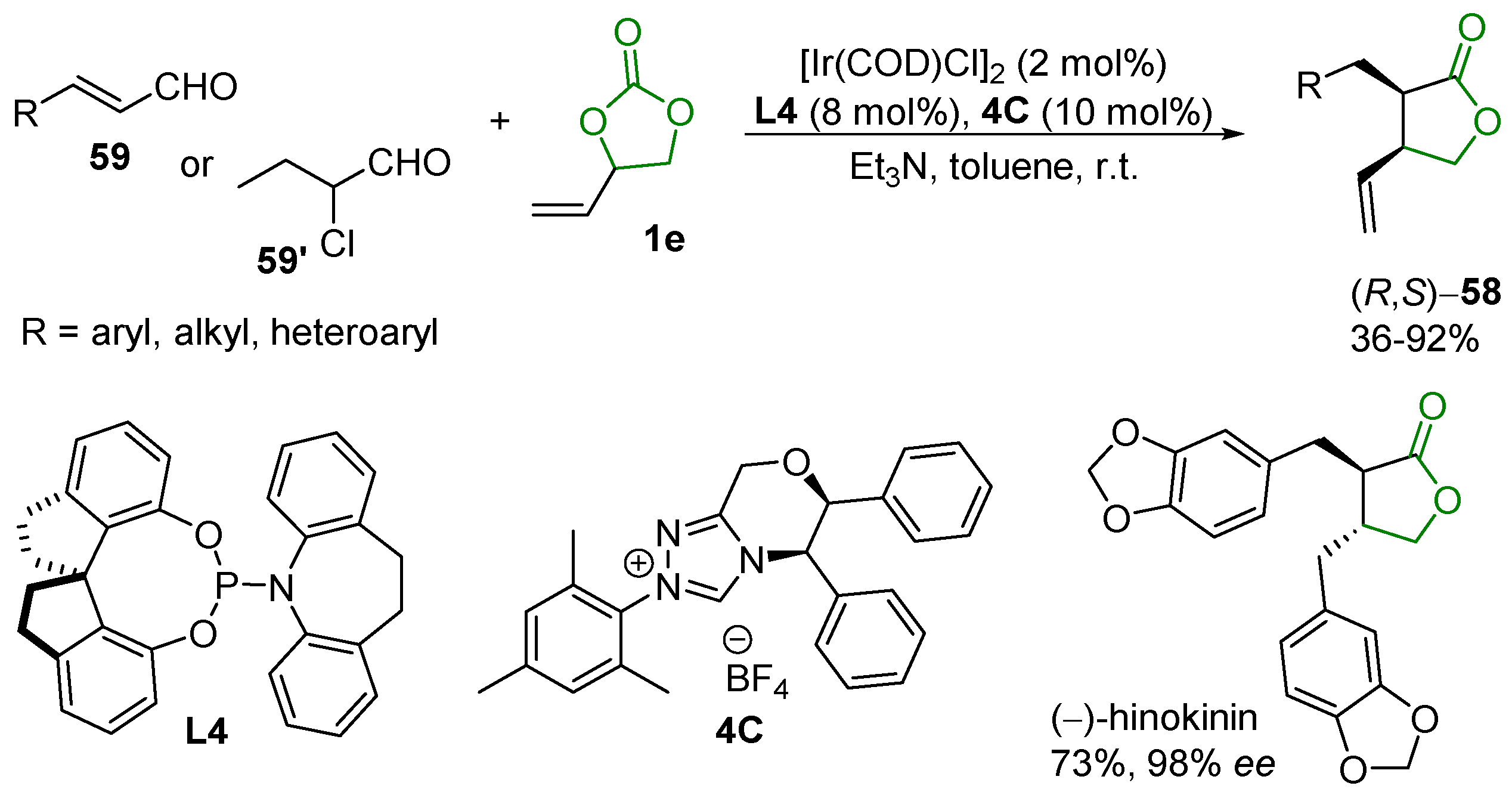

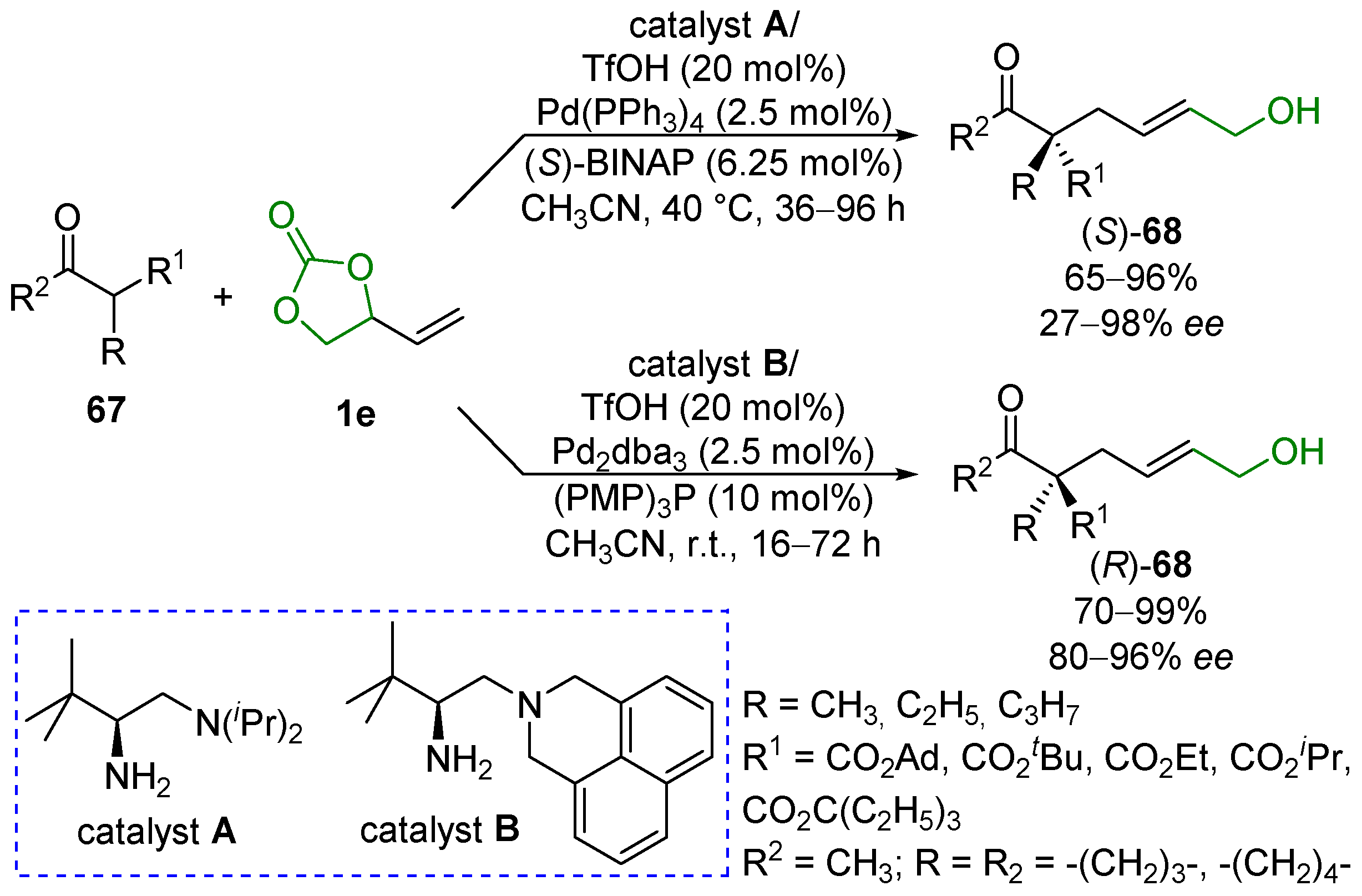

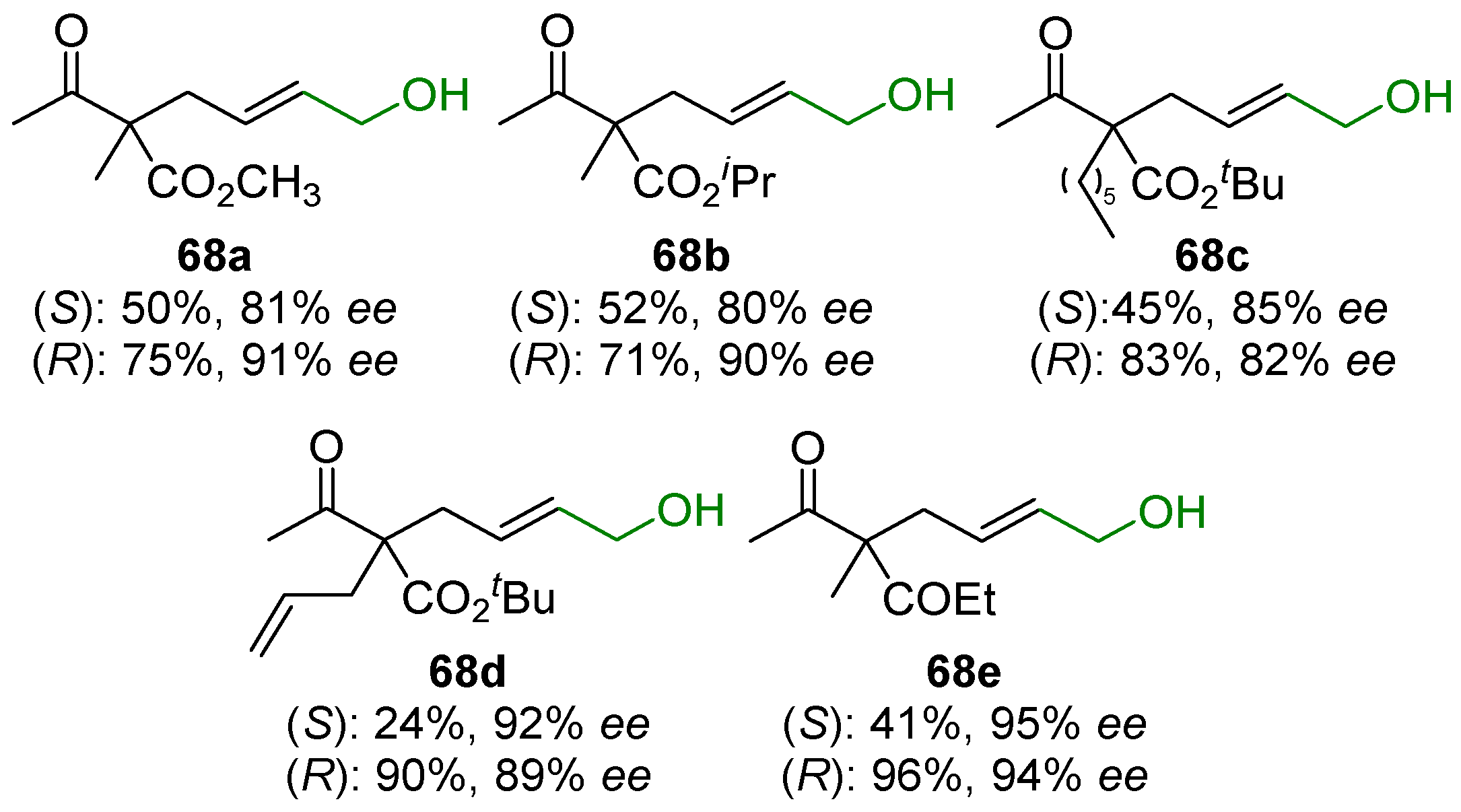

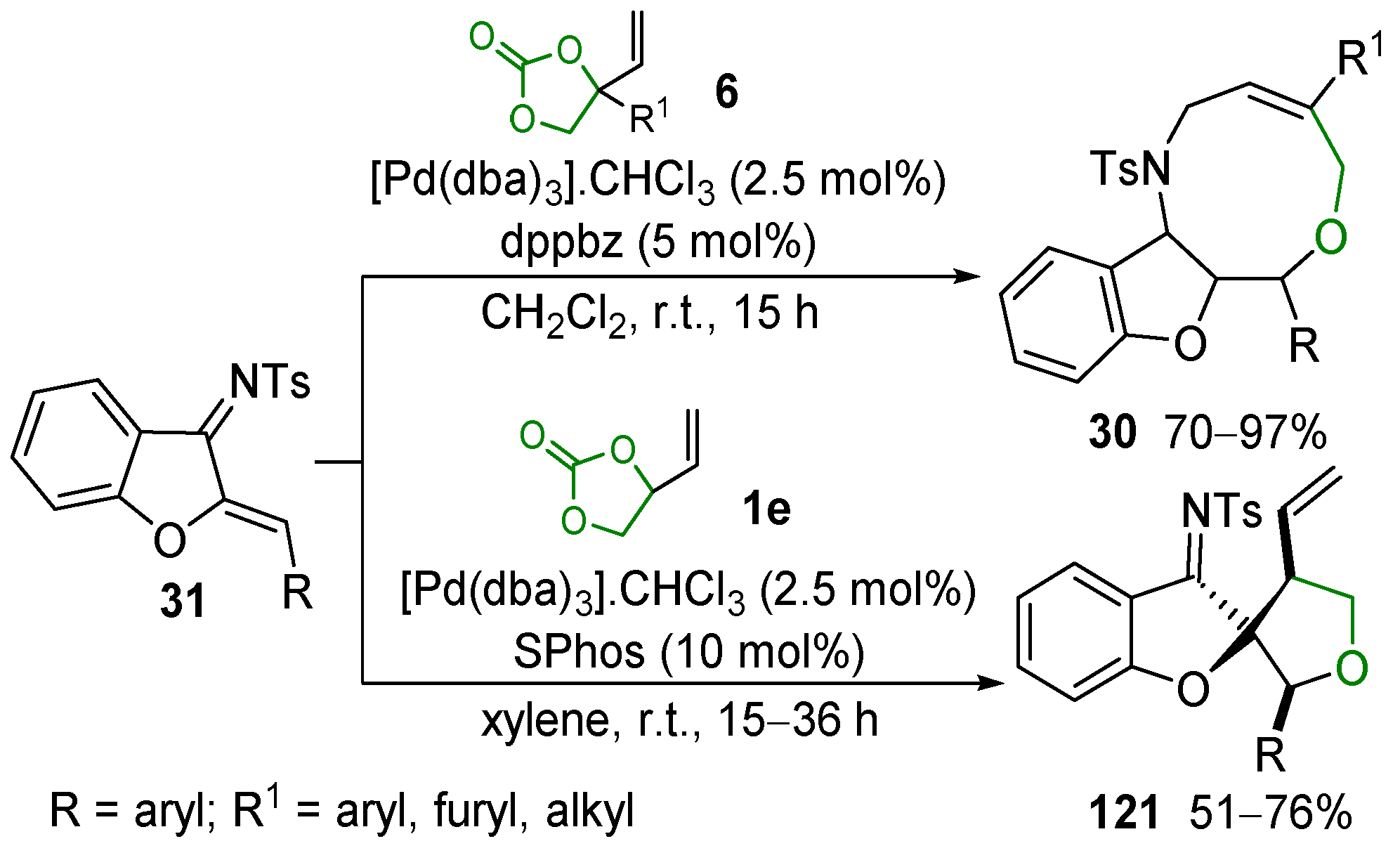

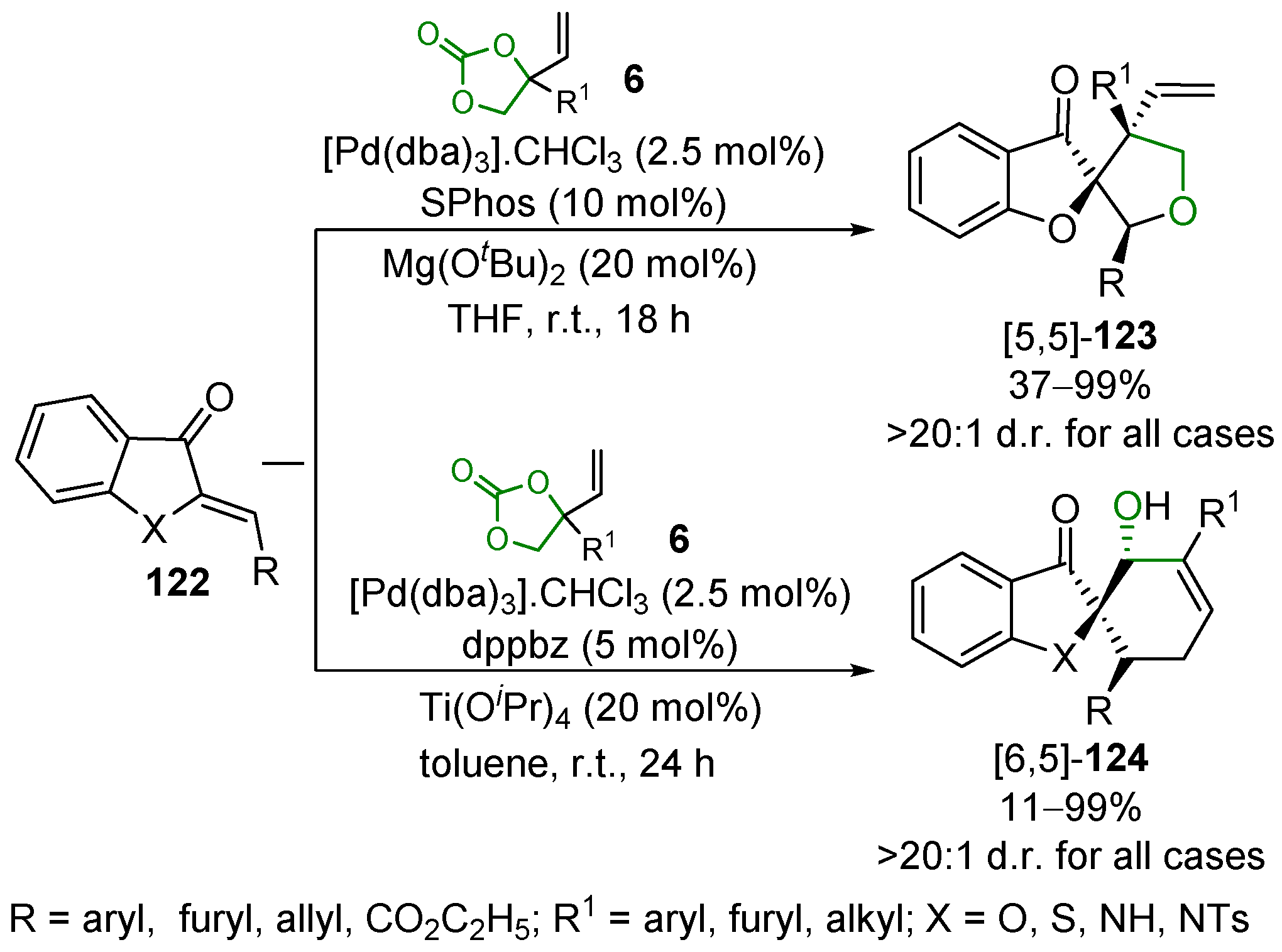

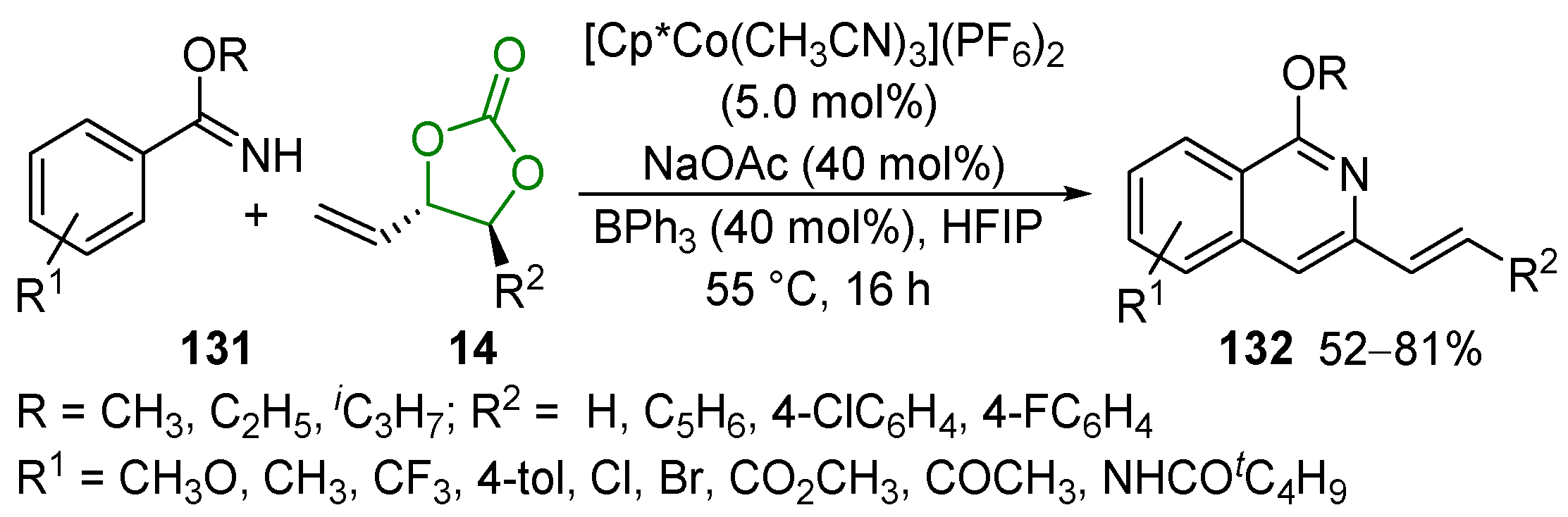

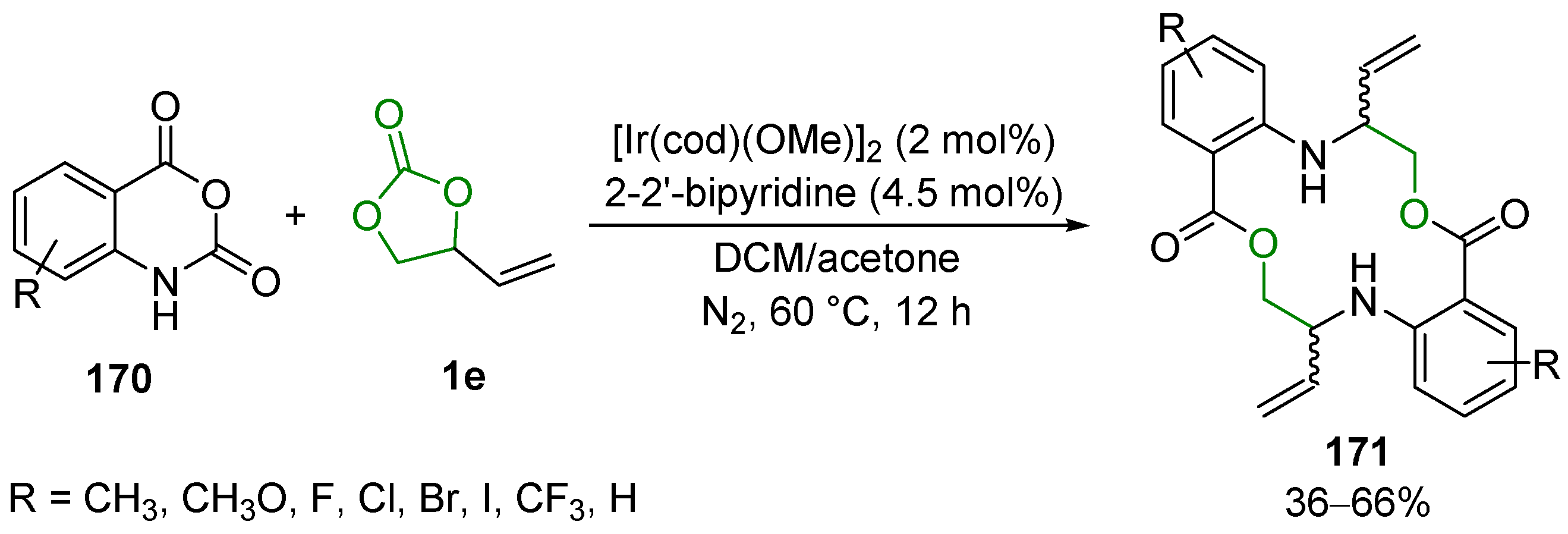

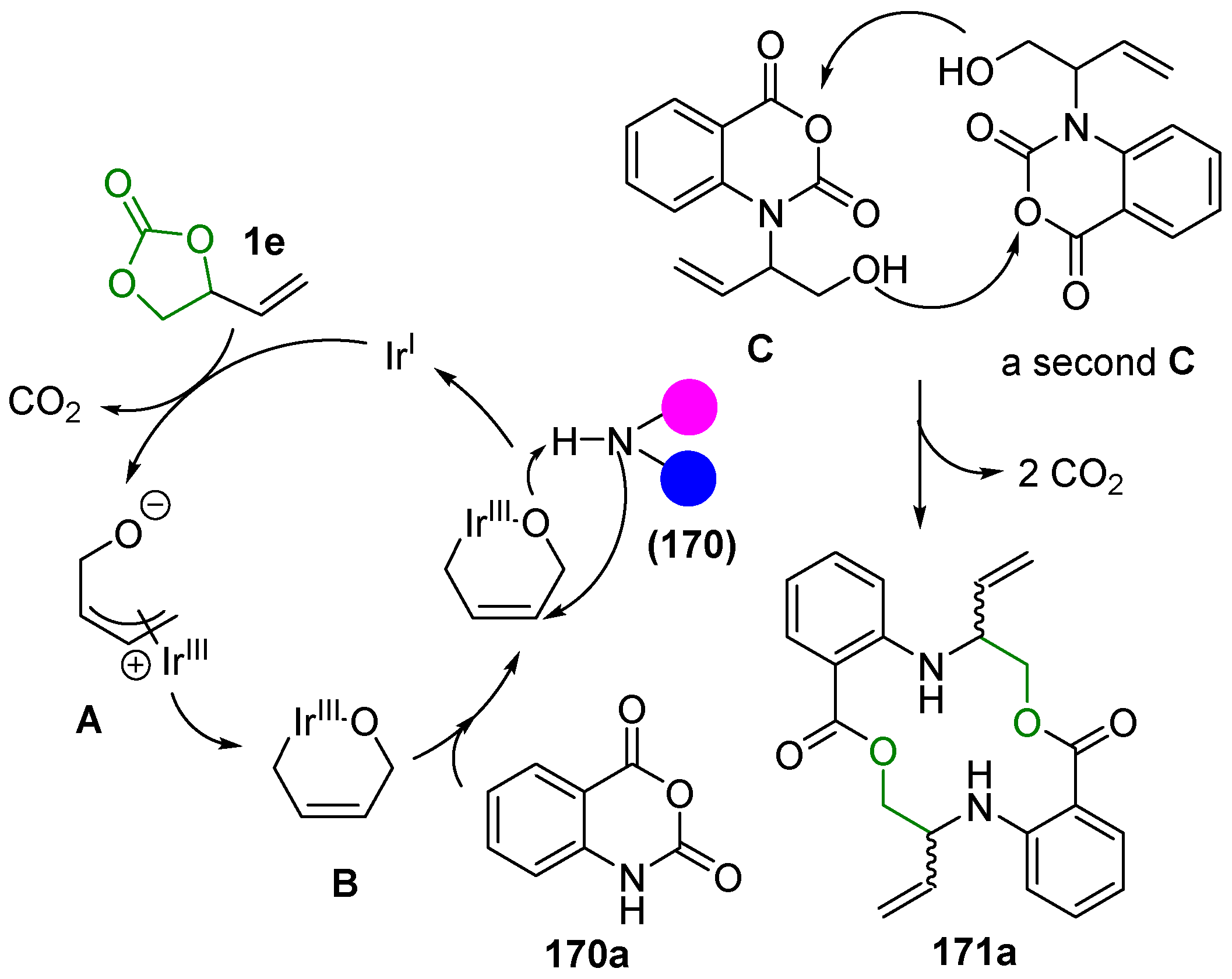

2.5. Metal-Catalyzed Miscellaneous Reactions

2.6. Other Reactions

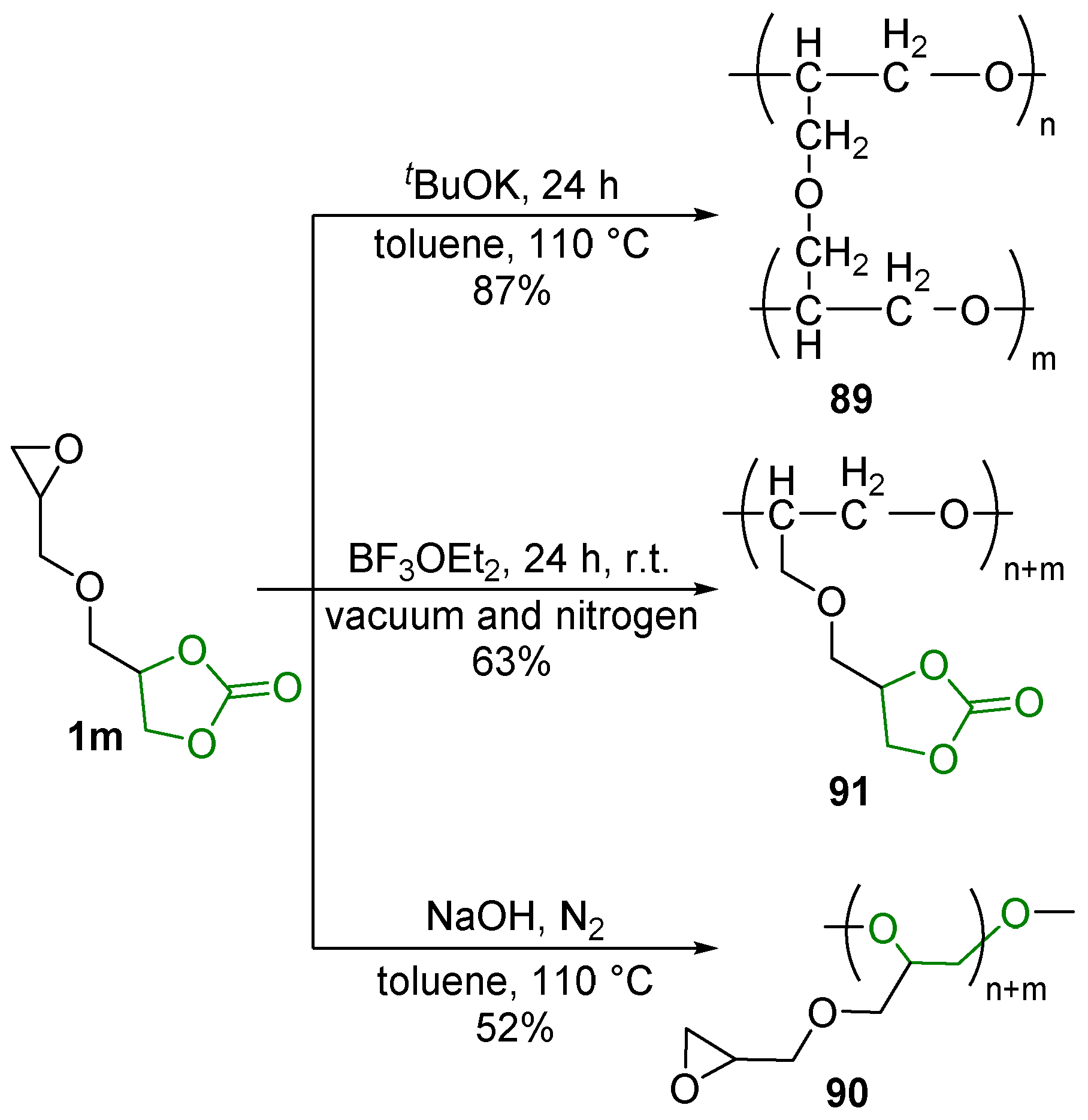

2.7. Alkene Polymerization

2.8. Ring-Opening Polymerization

3. Potential Applications in Biological Studies

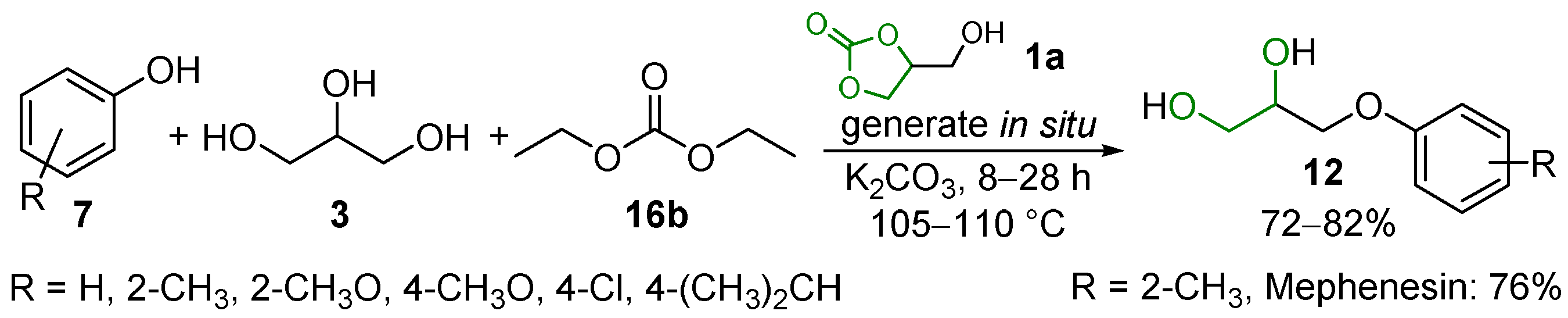

3.1. Raw Material Derivatives

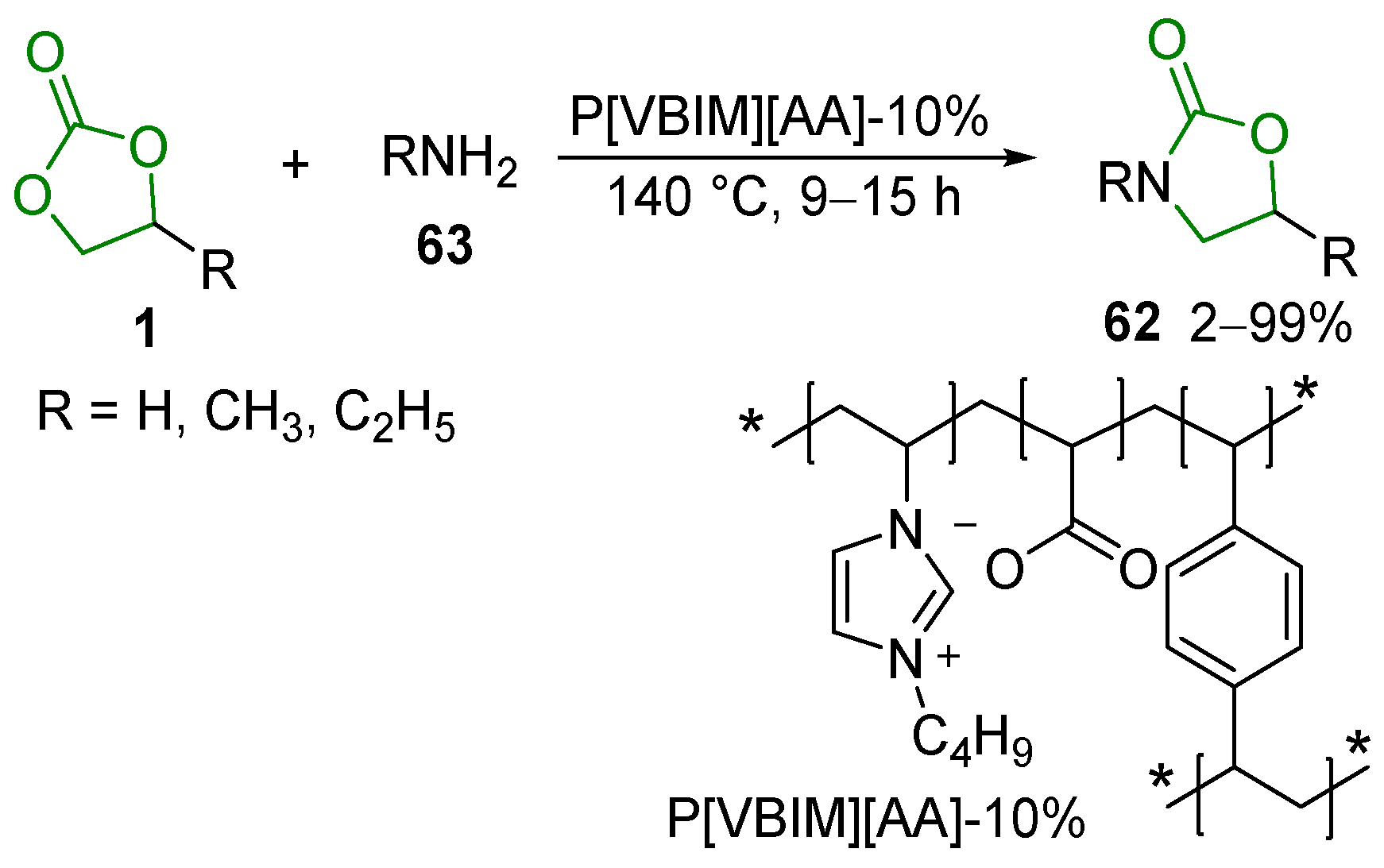

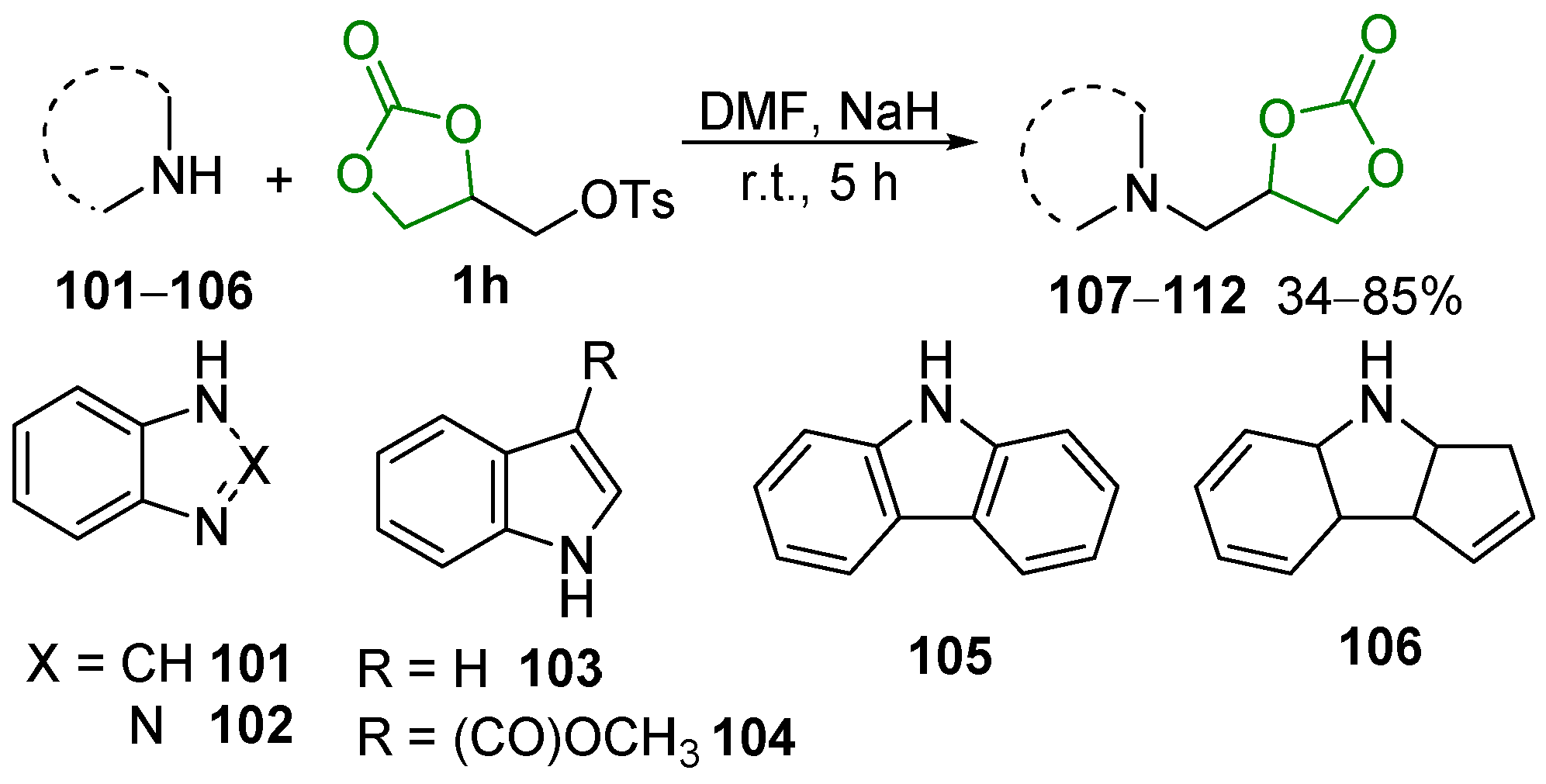

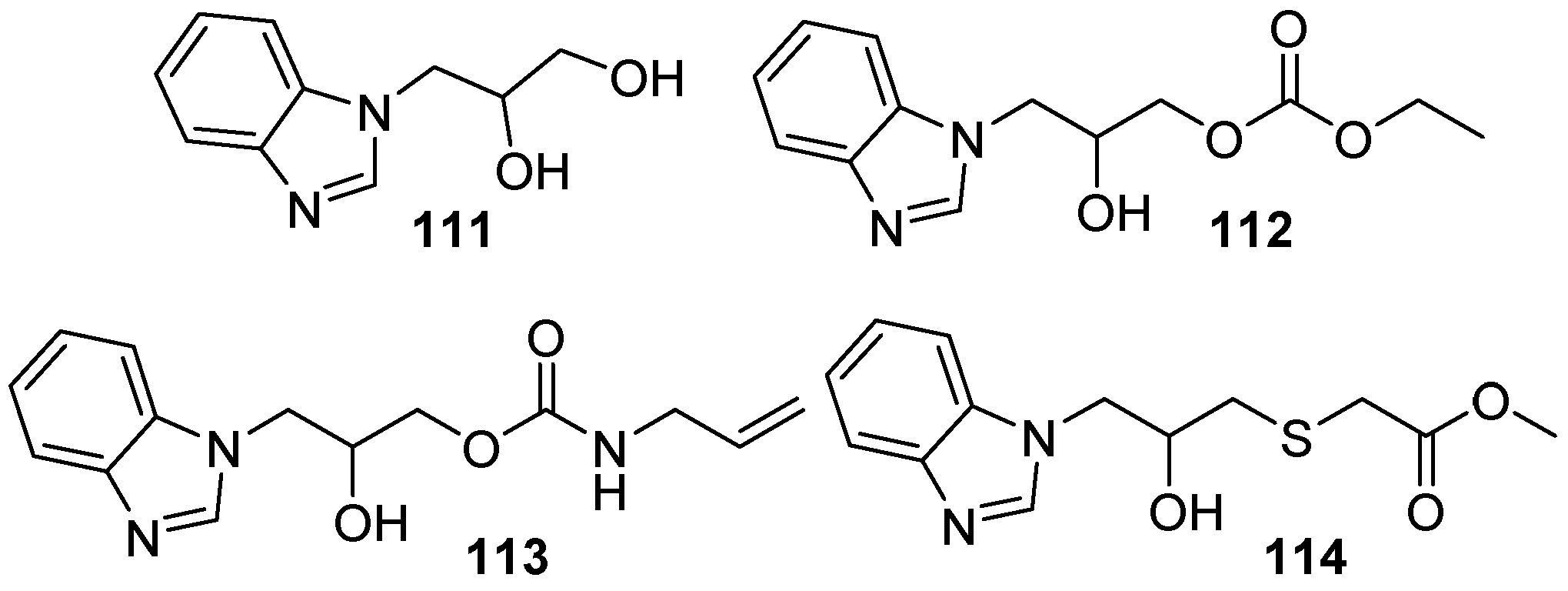

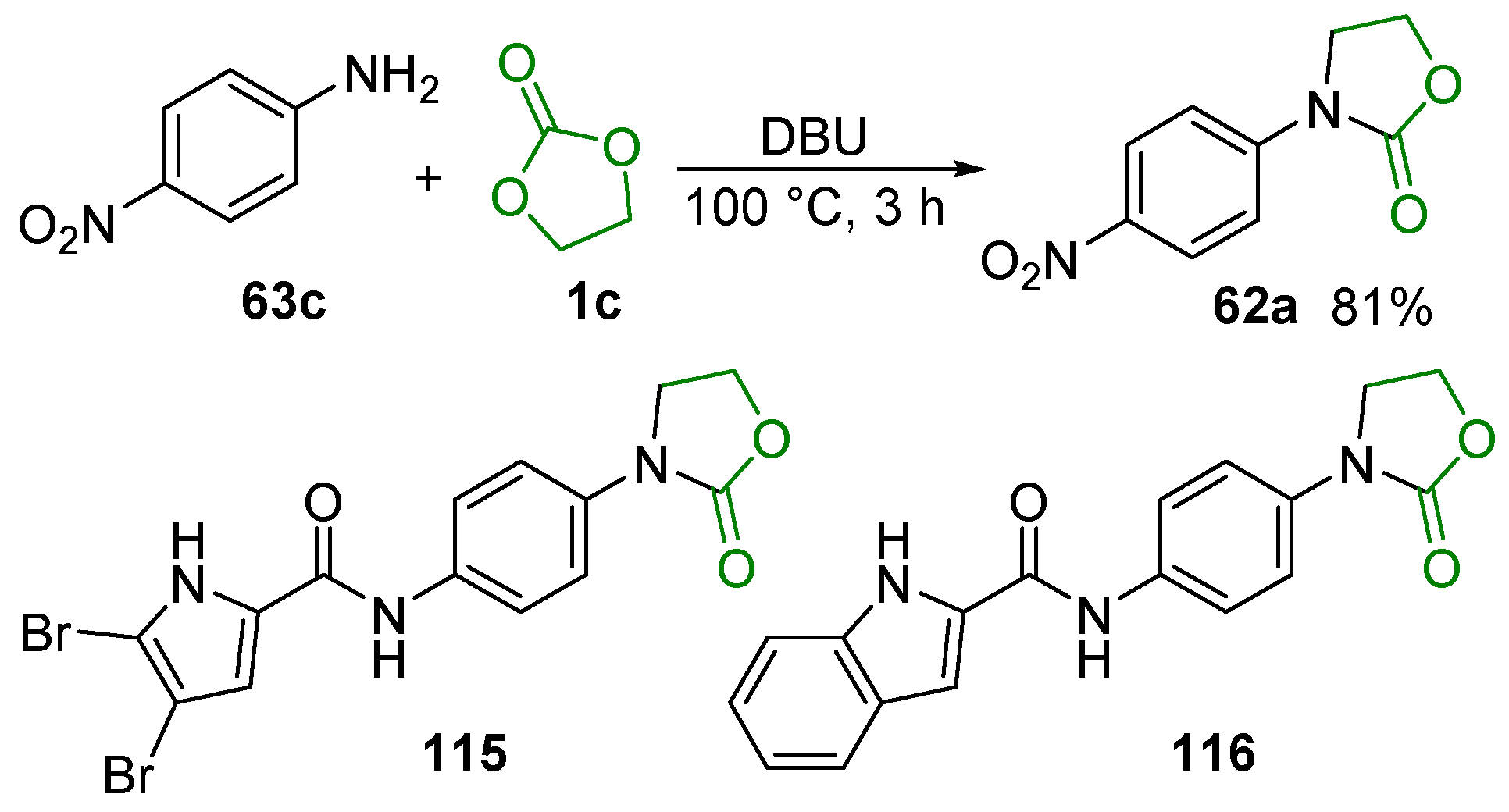

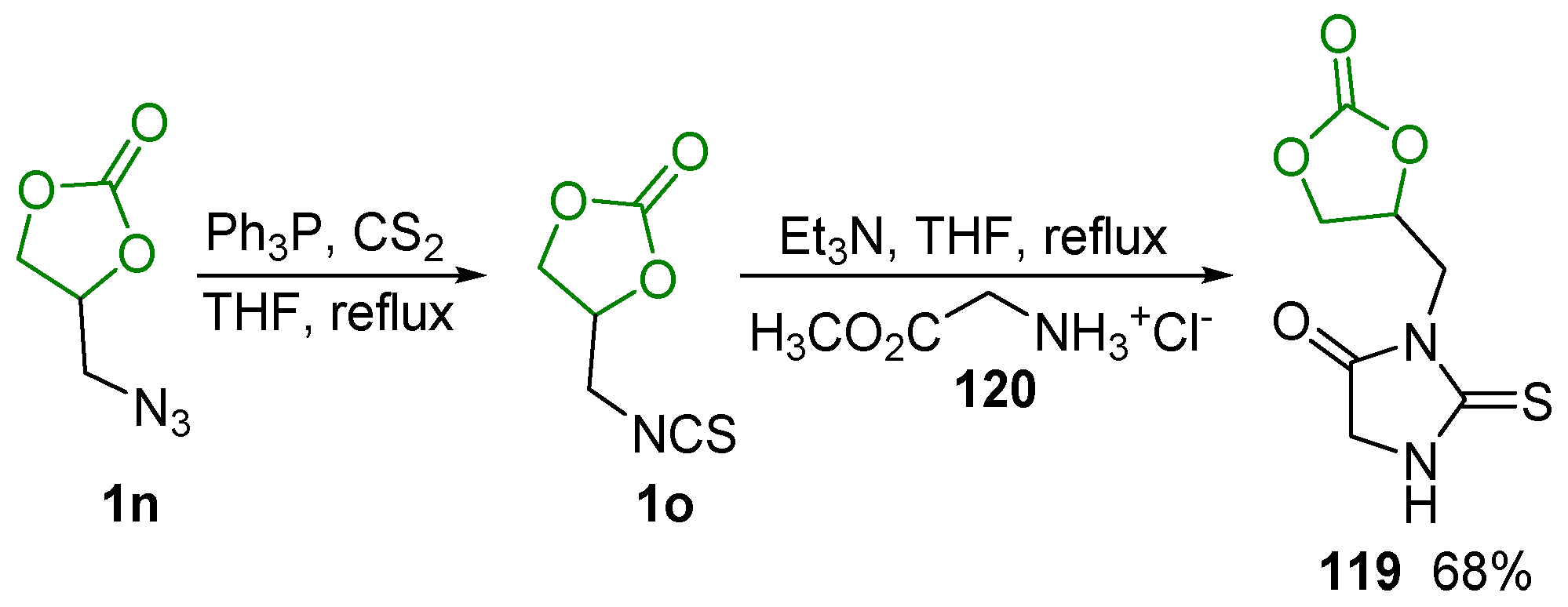

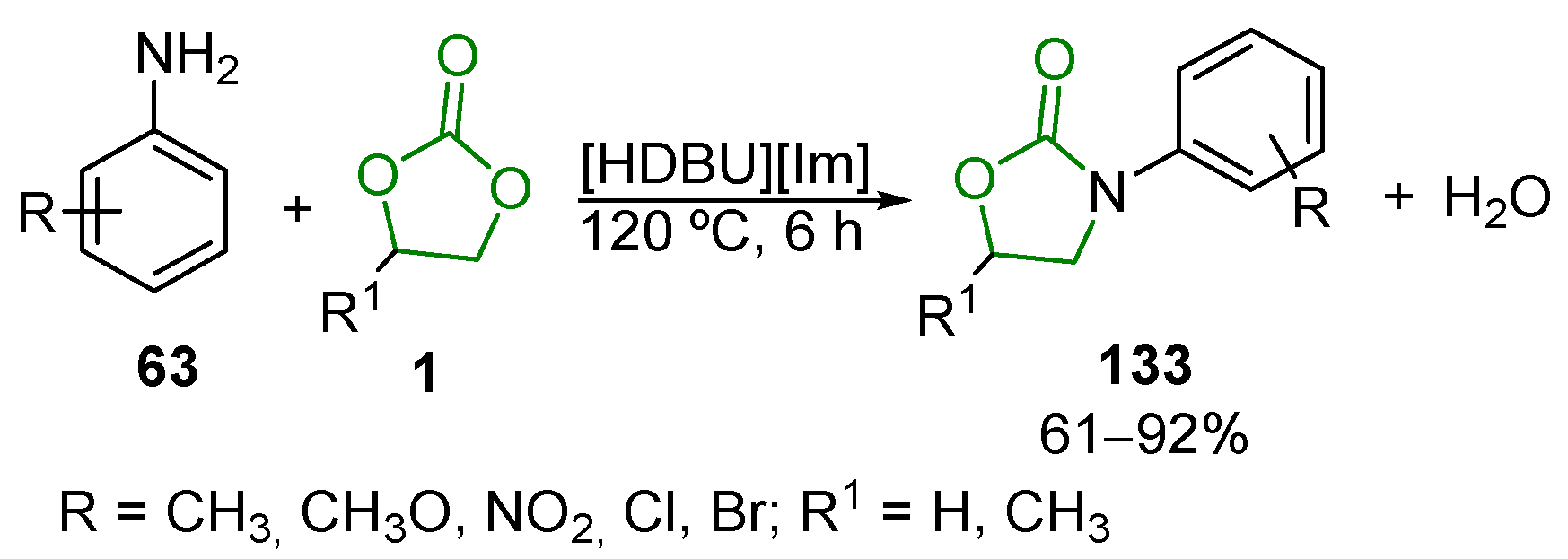

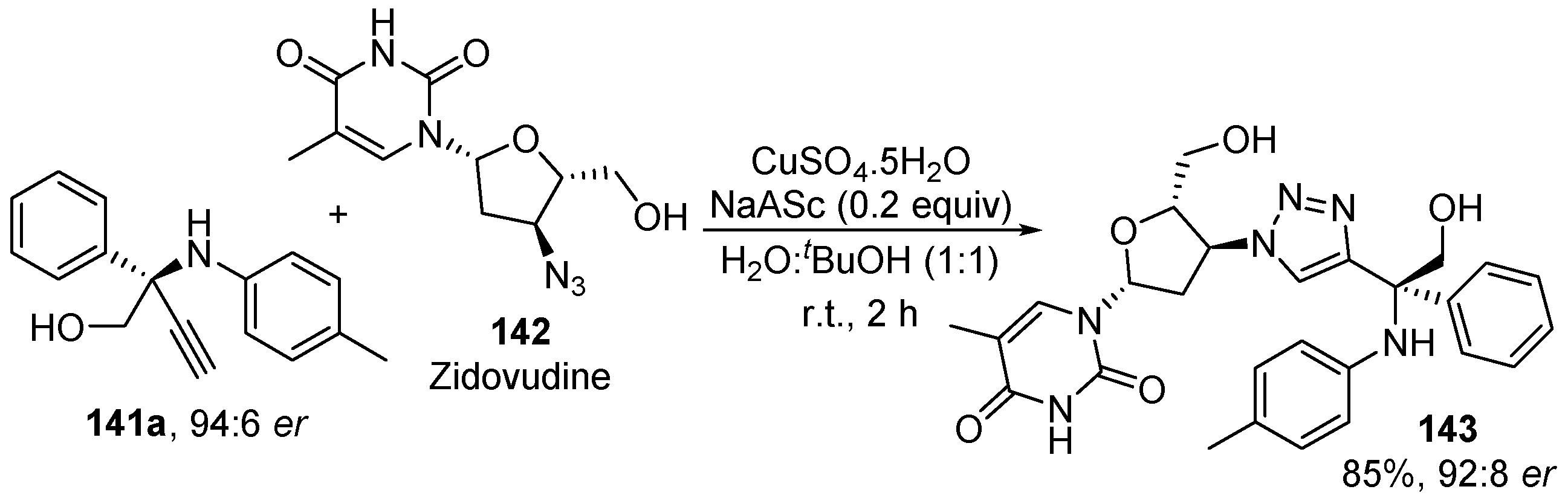

3.2. Heterocyclic Compounds

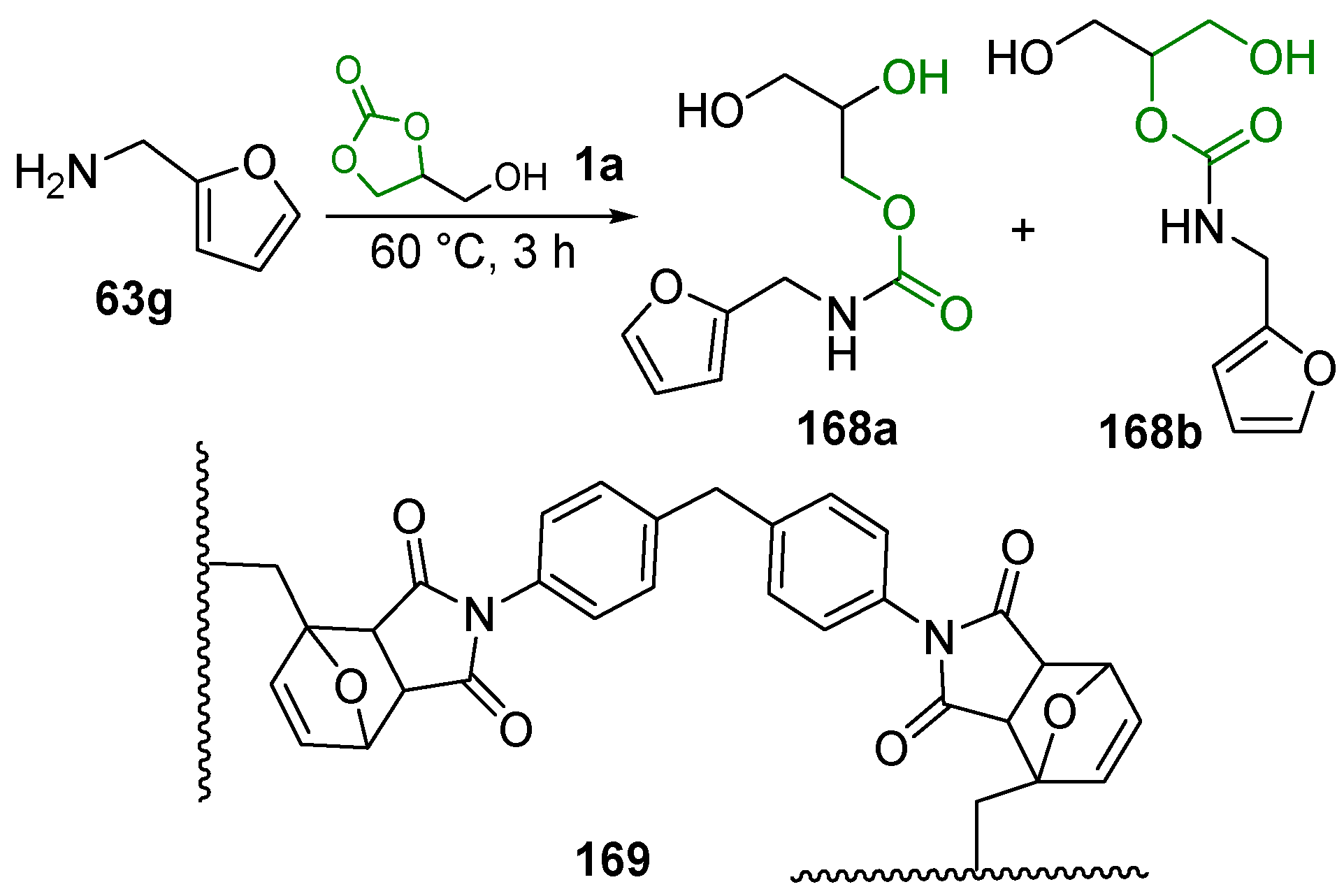

3.3. Bioactive Urethanes and Derivatives

3.4. Other Compounds with Biological Activity

4. Precursors to Materials

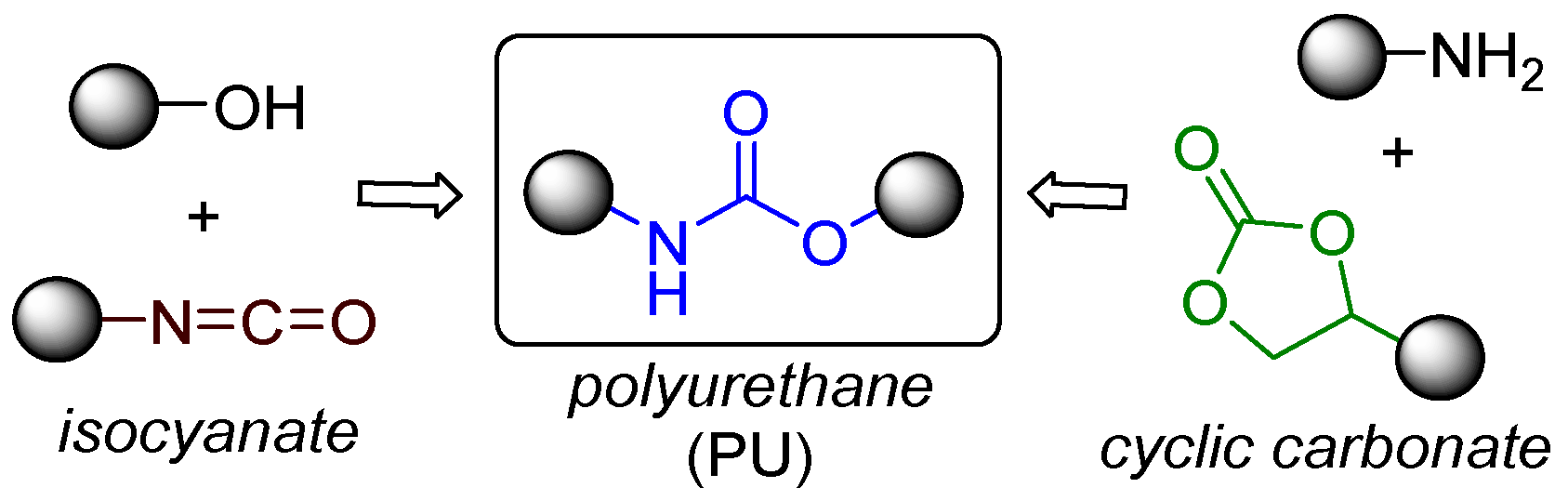

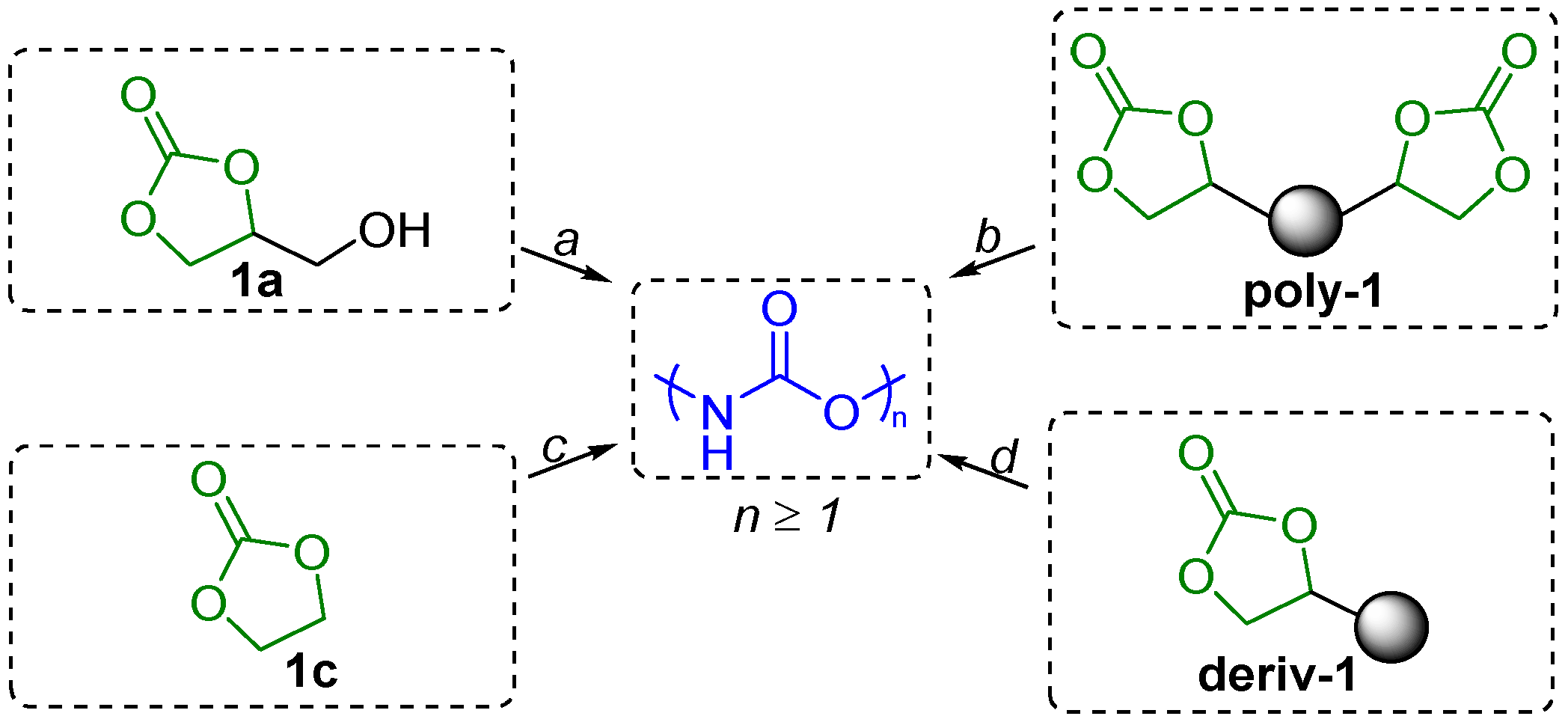

4.1. Urethanes and Polyurethanes

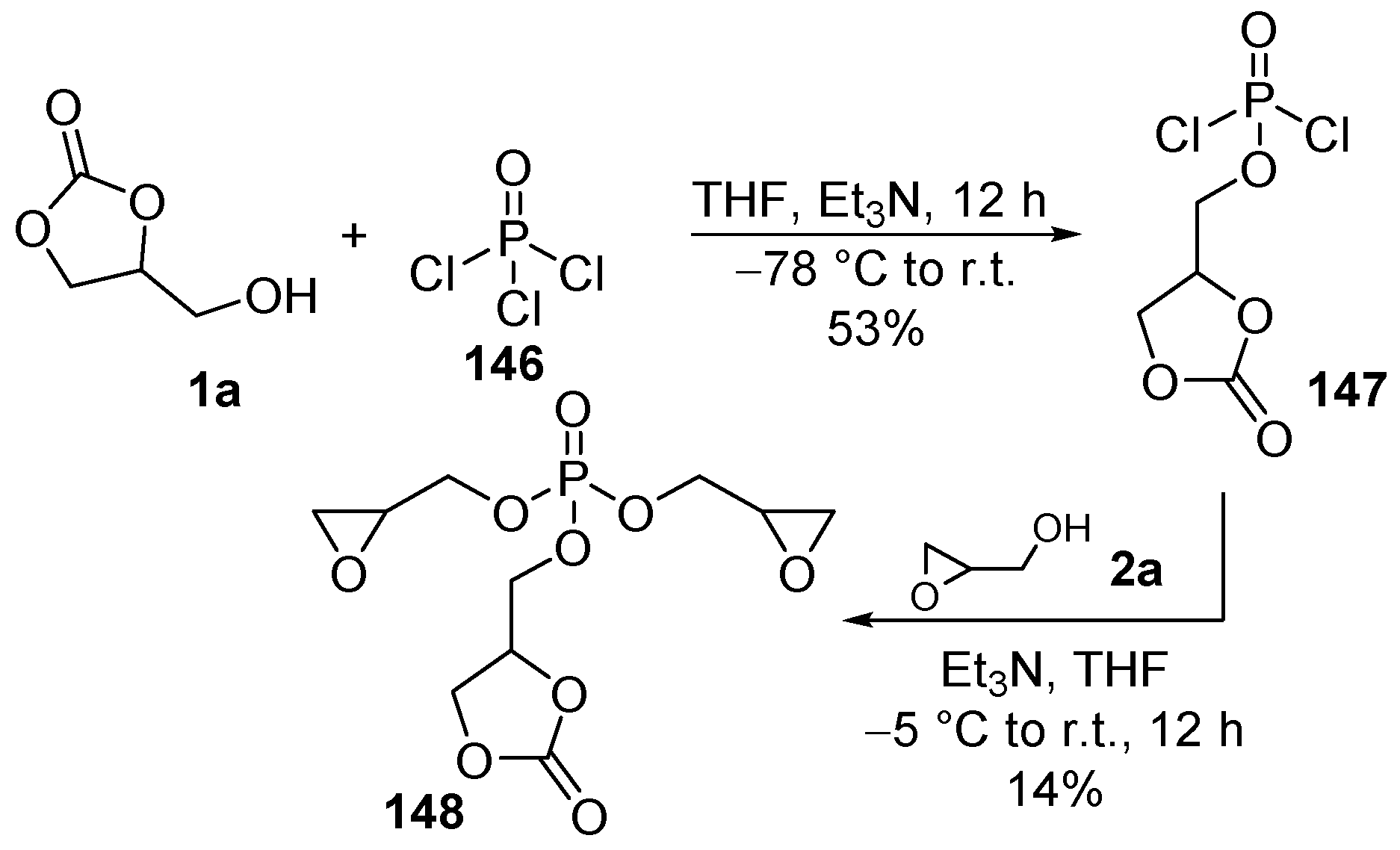

4.2. Flame Retardants

4.3. Energy and Electronics

4.4. Non-Ionic Surfactants

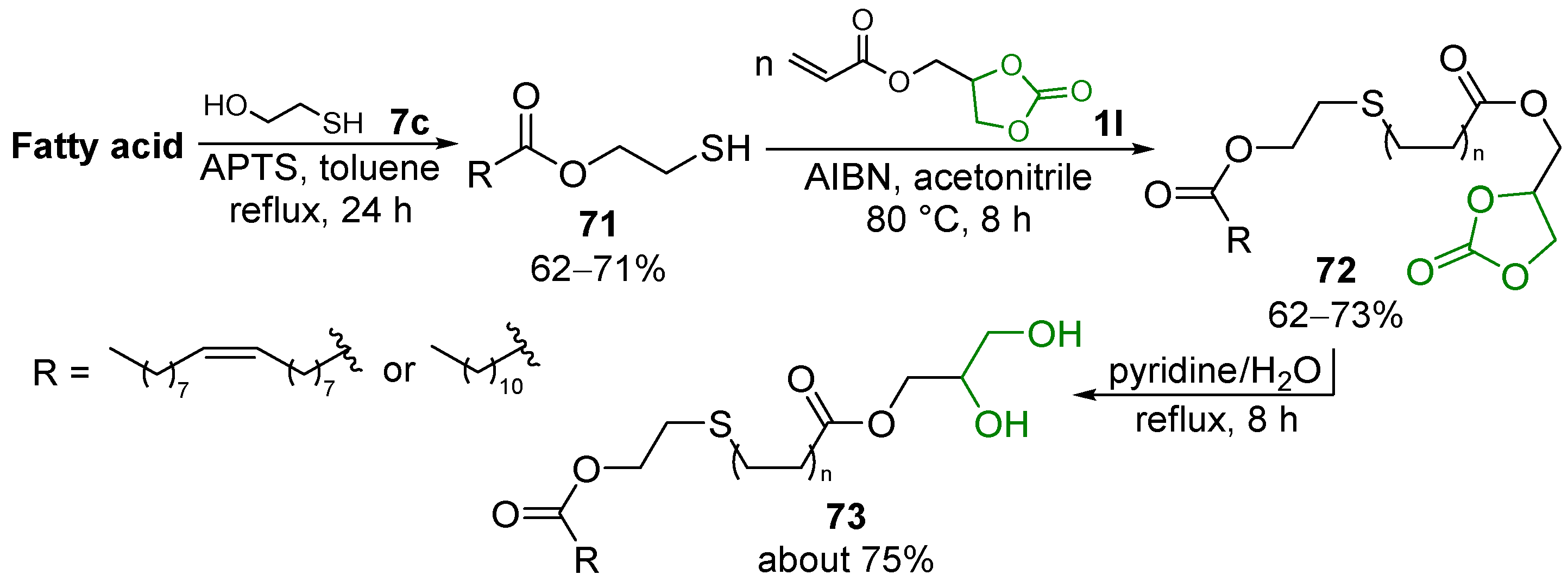

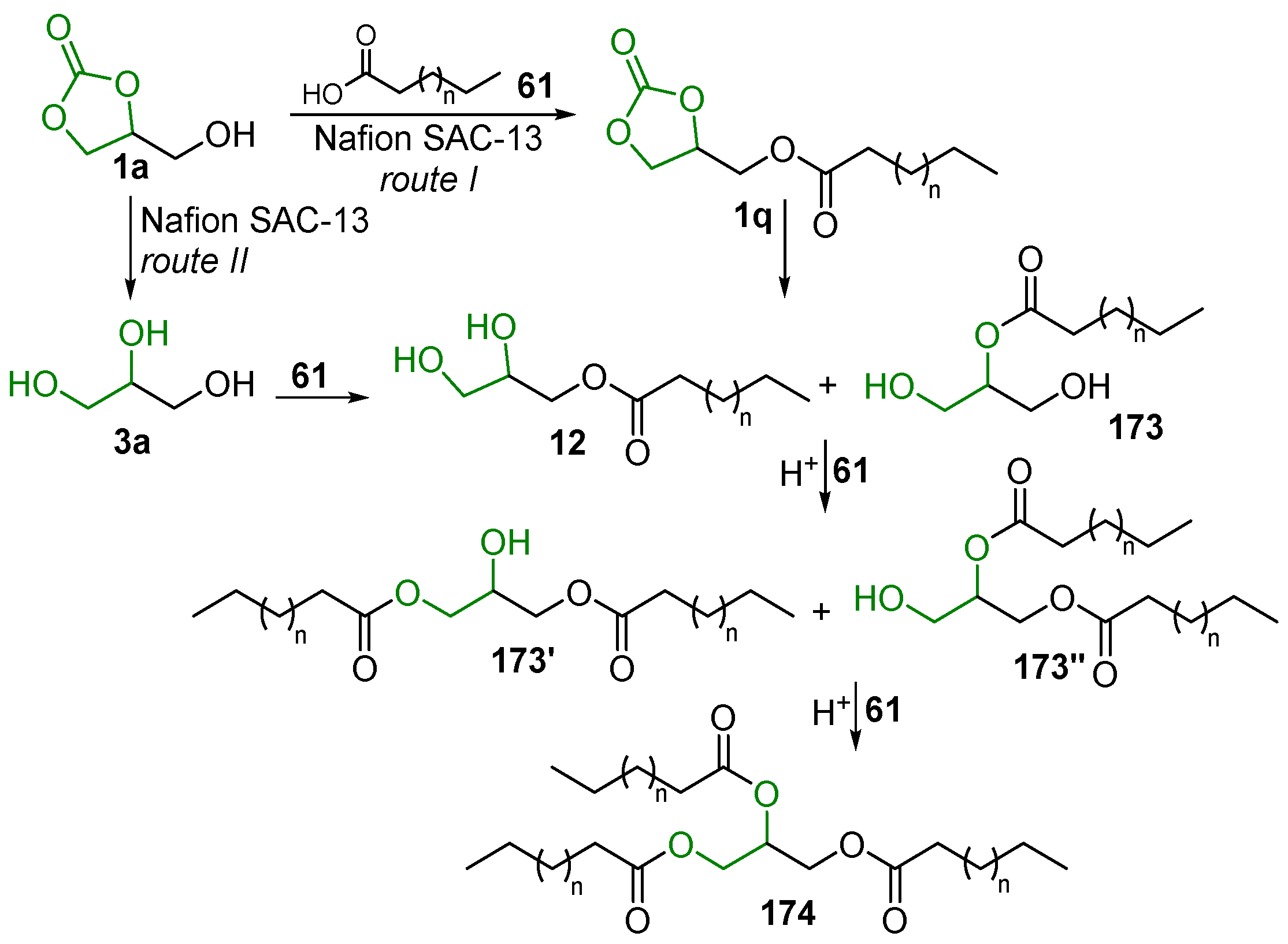

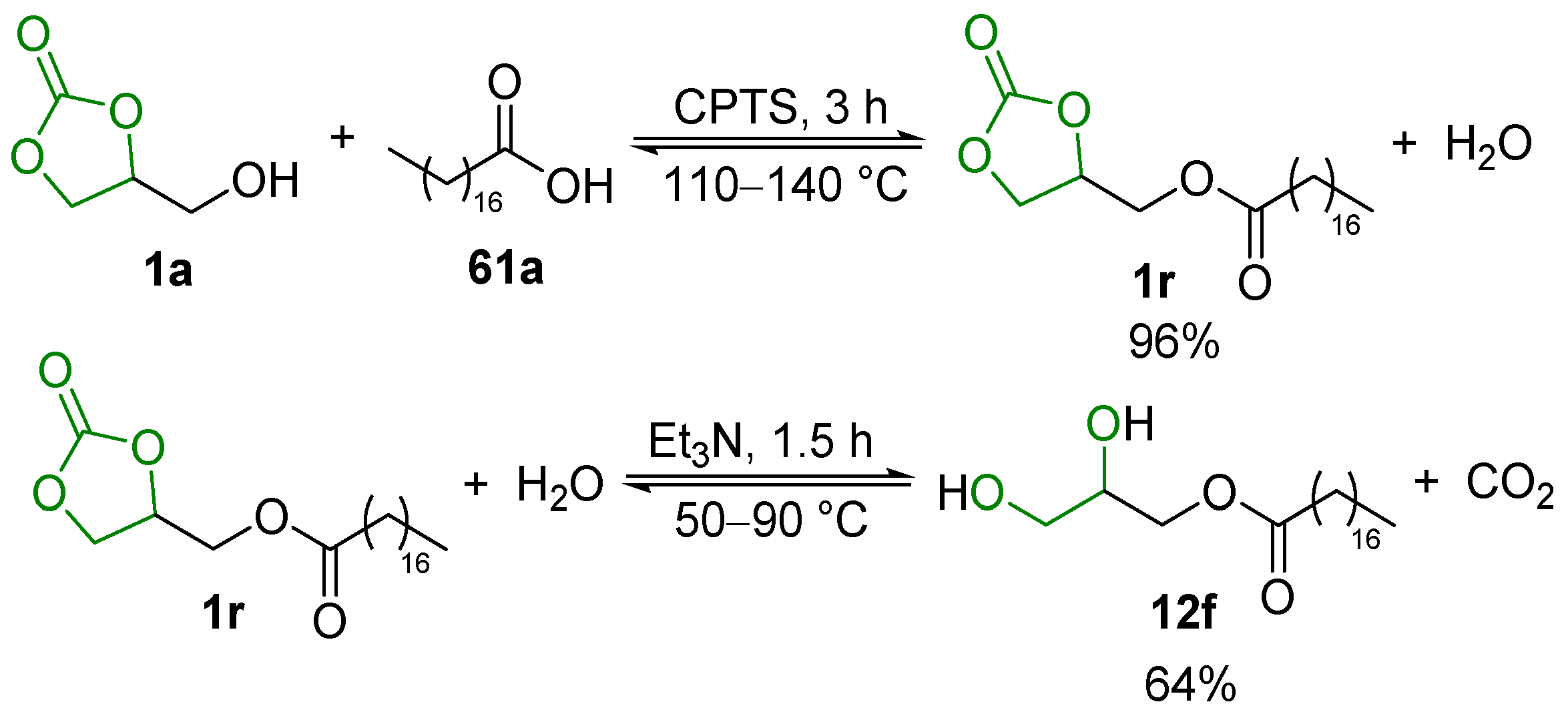

- −

- GC 1a and the acid 61 firstly react under acid catalysis to give the GC carboxylate 1q; this intermediate is subsequently decarbonylated to form two isomeric monoglycerides, 12 and 173, which can further undergo stepwise esterification to provide diglycerides 173′ and 174″ and the triglyceride 174 (Scheme 81, route I);

- −

- Firstly, 1a undergoes hydrolysis to glycerol, which similarly reacts with 58 to yield monoglycerides 174 and 12, diglycerides 173′ and 173″, and triglyceride 174 (Scheme 81, route II).

4.5. Miscellaneous

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ricapito, N.G.; Ghobril, C.; Zhang, H.; Grinstaff, M.W.; Putnam, D. Synthetic Biomaterials from Metabolically Derived Synthons. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 2664–2704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, W.; Gómez, J.E.; Cristòfol, À.; Xie, J.; Kleij, A.W. Catalytic Transformations of Functionalized Cyclic Organic Carbonates. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 13735–13747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäffner, B.; Schäffner, F.; Verevkin, S.P.; Borner, A. Organic Carbonates as Solvents in Synthesis and Catalysis. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 4554–4581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gérardy, R.; Estager, J.; Luis, P.; Debecker, D.P.; Monbaliu, J.-C.M. Versatile and Scalable Synthesis of Cyclic Organic Carbonates under Organocatalytic Continuous Flow Conditions. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2019, 9, 6841–6851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pescarmona, P.P. Cyclic Carbonates Synthesised from CO2: Applications, Challenges and Recent Research Trends. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2021, 29, 100457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marciniak, A.A.; Lamb, K.J.; Ozorio, L.P.; Mota, C.J.A.; North, M. Heterogeneous Catalysts for Cyclic Carbonate Synthesis from Carbon Dioxide and Epoxides. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2020, 26, 100365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoye, P.U.; Hammed, B.H. Review on Recent Progress in Catalytic Carboxylation and Acetylation of Glycerol as a Byproduct of Biodiesel Production. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev. 2016, 53, 558–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samoilov, V.O.; Ramazanov, D.N.; Nekhaev, A.I.; Maximov, A.L.; Bagdasarov, L.N. Heterogeneous Catalytic Conversion of Glycerol to Oxygenated Fuel Additives. Fuel 2016, 172, 310–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokicki, G.; Rakoczy, P.; Parzuchowski, P.; Sobiecki, M. Hyperbranched Aliphatic Polyethers Obtained from Environmentally Benign Monomer: Glycerol Carbonate. Green Chem. 2005, 7, 529–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maisonneuve, L.; Lamarzelle, O.; Rix, E.; Grau, E.; Cramail, H. Isocyanate-Free Routes to Polyurethanes and Poly(hydroxy Urethane)s. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 12407–12439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simão, A.-C.; Lynikaite-Pukleviciene, B.; Rousseau, C.; Tatibouët, A.; Cassel, S.; Šačkus, A.; Rauter, A.P.; Rollin, P. 1,2-Glycerol Carbonate: A Versatile Renewable Synthon. Lett. Org. Chem. 2006, 3, 744–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, J.; Rousseau, C.; Lynikaitė, B.; Šačkus, A.; de Leon, C.; Rollin, P.; Tatibouët, A. Tosylated Glycerol Carbonate, a Versatile Bis-electrophile to Access New Functionalized Glycidol Derivatives. Tetrahedron 2009, 65, 8571–8581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balieu, S.; Zein, A.E.; Sousa, R.; Jèrôme, F.; Tatibouët, A.; Gatard, S.; Pouilloux, Y.; Barrault, J.; Rollin, P.; Bouquillon, S. One-Step Surface Decoration of Poly(propyleneimines) (PPIs) with the Glyceryl Moiety: New Way for Recycling Homogeneous Dendrimer-Based Catalysts. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2010, 352, 1826–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilkauskaitė, G.; Krikštolaitytė, S.; Paliulis, O.; Rollin, P.; Tatibouët, A.; Šačkus, A. Use of Tosylated Glycerol Carbonate to Access N-Glycerylated Aza-aromatic Species. Tetrahedron 2013, 69, 3721–3727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, P.D.; Monge, S.; Lapinte, V.; Raoul, Y.; Robin, J.J. Various Radical Polymerizations of Glycerol-based Monomers. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2013, 115, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Grinstaff, M.W. Recent Advances in Glycerol Polymers: Chemistry and Biomedical Applications. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2014, 35, 1906–1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa-Gómez, J.R.; Gómez-Jiménez-Aberasturi, O.; Ramírez-López, C.; Belsué, M. A Brief Review on Industrial Alternatives for the Manufacturing of Glycerol Carbonate, a Green Chemical. Org. Process. Res. Dev. 2012, 16, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnati, M.O.; Amigoni, S.; Givenchy, E.P.T.; Darmanin, T.; Choulet, O.; Guittard, F. Glycerol Carbonate as a Versatile Building Block for Tomorrow: Synthesis, Reactivity, Properties and Applications. Green Chem. 2013, 15, 283–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besse, V.; Camara, F.; Voirin, C.; Auvergne, R.; Caillol, S.; Boutevin, B. Synthesis and applications of unsaturated cyclocarbonates. Polym. Chem. 2013, 4, 4545–4561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duval, A.; Avérous, L. Cyclic Carbonates as Safe and Versatile Etherifying Reagents for the Functionalization of Lignins and Tannins. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 7334–7343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabanelli, T.; Giliberti, C.; Mazzoni, R.; Cucciniello, R.; Cavani, F. An Innovative Synthesis Pathway to Benzodioxanes: The Peculiar Reactivity of Glycerol Carbonate and Catechol. Green Chem. 2019, 21, 329–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagliaro, M.; Rossi, M. The Future of Glycerol, New Usages for a Versatile Raw Material; RSC Green Chemistry Book Series; RSC Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2010; p. 108. [Google Scholar]

- Jérôme, F.; Pouilloux, Y.; Barrault, J. Rational Design of Solid Catalysts for the Selective Use of Glycerol as a Natural Organic Building Block. ChemSusChem 2008, 1, 586–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchings, G.J.; Lee, D.F.; Minihan, A.R. Epoxidation of Allyl Alcohol to Glycidol Using Titanium Silicalite TS-1: Effect of the Reaction Conditions and Catalyst Acidity. Catal. Lett. 1996, 39, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.S.; Simanjuntaka, F.S.H.; Oh, J.H.; Lee, K.I.; Lee, S.D.; Cheong, M.; Kim, H.S.; Lee, H. Ionic-liquid-catalyzed decarboxylation of glycerol carbonate to glycidol. J. Catal. 2013, 297, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, X.; Wang, L.; Cao, J.; Cao, Y.; He, P.; Zhou, J.; Li, H. Efficient Synthesis of Epoxybutane from Butanediol via a Two-step Process. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 10072–10080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolívar-Diaz, C.L.; Calvino-Casilda, V.; Rubio-Marcos, F.; Fernández, J.F.; Beñares, M.A. New Concepts for Process Intensification in the Conversion of Glycerol Carbonate to Glycidol. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2013, 129, 575–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, J.H.; Kim, J.S.; Kim, M.H.; Lee, K.Y.; Lee, M.S. Synthesis of Glycidol by Decarboxylation of Glycerol Carbonate Over Zn–La Catalysts with Different Molar Ratio. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2016, 16, 10898–10902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.; Reddy, B.; Ganesh, A.; Mahajani, S. Zinc/Lanthanum Mixed-Oxide Catalyst for the Synthesis of Glycerol Carbonate by Transesterification of Glycerol. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2014, 53, 18786–18795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endah, Y.K.; Kim, M.S.; Choi, J.; Jae, J.; Lee, S.D.; Lee, H. Consecutive Carbonylation and Decarboxylation of Glycerol with Urea for the Synthesis of Glycidol via Glycerol Carbonate. Catal. Today 2017, 293–294, 136–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.-B.; Tang, X.; Falivene, L.; Caporaso, L.; Cavallo, L.; Chen, E.Y.-X. Organocatalytic Coupling of Bromo-Lactide with Cyclic Ethers and Carbonates to Chiral Bromo-Diesters: NHC or Anion Catalysis? ACS Catal. 2017, 7, 3929–3933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Guo, W.; Cai, A.; Escudero-Adán, E.C.; Kleij, A.W. Pd-Catalyzed Enantio- and Regioselective Formation of Allylic Aryl Ethers. Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 6388–6391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, W.; Kuniyil, R.; Gómez, J.E.; Maseras, F.; Kleij, A.W. A Domino Process toward Functionally Dense Quaternary Carbons through Pd-Catalyzed Decarboxylative C(sp3)–C(sp3) Bond Formation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 3981–3987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balaraman, E.; Fogler, E.; Milstein, D. Efficient Hydrogenation of Biomass-derived Cyclic Di-esters to 1,2-Diols. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 1111–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balaraman, E.; Gunanathan, C.; Zhang, J.; Shimon, L.J.W.; Milstein, D. Efficient Hydrogenation of Organic Carbonates, Carbamates and Formates Indicates Alternative Routes to Methanol Based on CO2 and CO. Nat. Chem. 2011, 3, 609–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Rong, L.; Wu, J.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Z.; Ding, K. Catalytic Hydrogenation of Cyclic Carbonates: A Practical Approach from CO2 and Epoxides to Methanol and Diols. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 13041–13045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Ji, L.; Ji, Y.; Elageed, E.H.M.; Gao, G. Hydrogenation of Ethylene Carbonate Catalyzed by Lutidine-bridged N-Heterocyclic Carbene Ligands and Ruthenium Precursors. Catal. Commun. 2016, 85, 57–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhu, H.; Chen, J.; Le, Z.-G.; Tu, T. Synthesis, Characterization and Catalytic Application of Pyridine-Bridged N-Heterocyclic Carbene–Ruthenium Complexes in the Hydrogenation of Carbonates. Chem. Asian J. 2017, 12, 2809–2812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Huang, Z.; Han, Z.; Ding, K.; Liu, H.; Xia, C.; Chen, J. Efficient Production of Methanol and Diols via the Hydrogenation of Cyclic Carbonates using Copper–Silica Nanocomposite Catalysts. Green Chem. 2015, 17, 4281–4290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Yao, X.; Cheng, W.; Zhang, S. 1,3-Dimethylimidazolium-2-carboxylate: A Zwitterionic Salt for the Efficient Synthesis of Vicinal Diols from Cyclic Carbonates. Green Chem. 2014, 16, 3297–3304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Wang, L.; Han, X.; He, P.; Cao, Y.; Li, H. Influence of Support on the Performance of Copper Catalysts for the Effective Hydrogenation of Ethylene Carbonate to Synthesize Ethylene Glycol and Methanol. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 45894–45906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Wang, L.; Han, X.; Cao, Y.; He, P.; Li, H. Selective Hydrogenation of Ethylene Carbonate to Methanol and Ethylene Glycol over Cu/SiO2 Catalysts Prepared by Ammonia Evaporation Method. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2017, 42, 2144–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Shi, Y.; Ma, K.; Tang, S.; Liu, C.; Yue, H.; Liang, B. Nanoarray Cu/SiO2 Catalysts Embedded in Monolithic Channels for the Stable and Efficient Hydrogenation of CO2-Derived Ethylene Carbonate. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2018, 57, 1924–1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Jiang, N.; Ren, D.; Song, Z.; Li, L.; Huo, Z. Hydrothermal Conversion of Ethylene Carbonate to Ethylene Glycol. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2016, 41, 9118–9122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakatake, D.; Yazaki, R.; Matsushima, Y.; Ohshima, T. Transesterification Reactions Catalyzed by a Recyclable Heterogeneous Zinc/Imidazole Catalyst. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2016, 358, 2569–2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

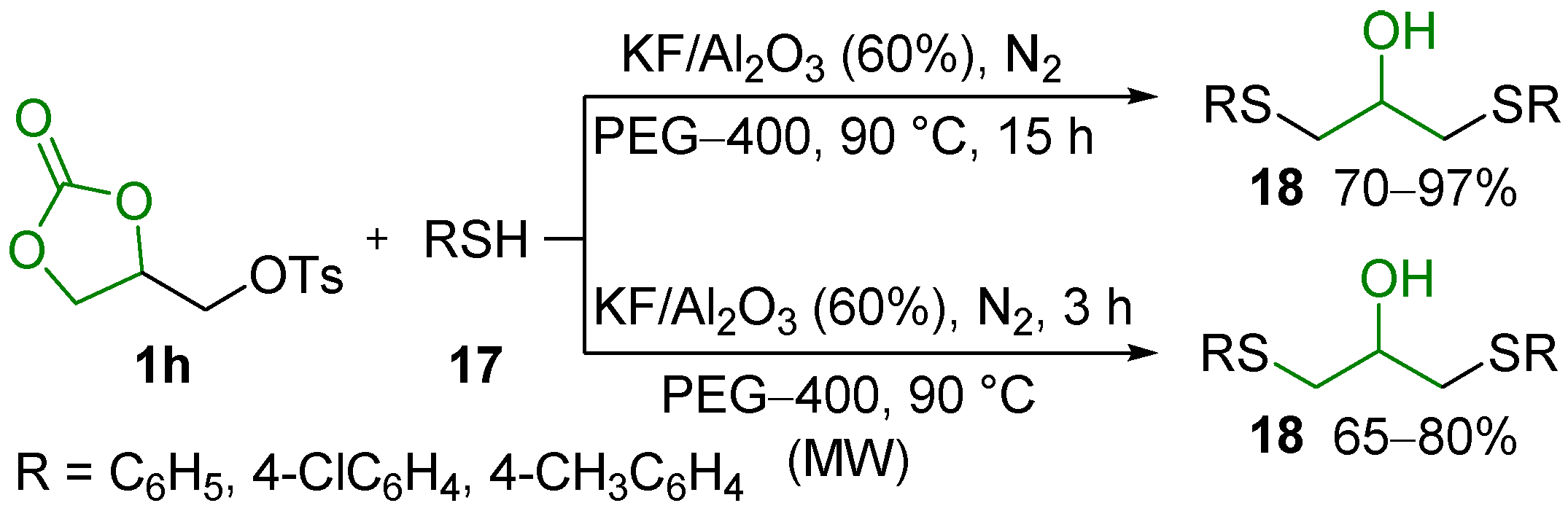

- Perin, G.; Silva, C.M.; Borges, E.L.; Goulart, H.A.; Silva, R.B.; Jacob, R.G.; Silva, M.S.; Alves, D.; Schumacher, R.F. Selective Synthesis of 4-Chalcogenylmethyl-1,3-dioxolan-2-ones and 1,3-Bis(organylchalcogenyl)propan-2-ols from 3-O-Tosyl Glycerol 1,2-Carbonate. ChemistrySelect 2016, 1, 6238–6242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pongrácz, P.; Kollár, L. Asymmetric Hydroformylation of 4-Vinyl-1,3-dioxolan-2-one. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2017, 54, 1430–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Vries, G.J.; Werner, T. Transfer Hydrogenation of Cyclic Carbonates and Polycarbonate to Methanol and Diols by Iron Pincer Catalysts. Green Chem. 2019, 21, 5248–5255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Yan, B.; Wang, S.; Ma, X. Recent Advances in Dialkyl Carbonates Synthesis and Applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 3079–3116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.-H.; Lee, S.; Shin, D.; Hahm, H.-S. Dimethyl Carbonate Synthesis via Transesterification of Ethylene Carbonate and Methanol using Ionic Liquid Catalysts Immobilized on Mesoporous Cellular Foams. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2016, 42, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saptal, V.B.; Bhanage, B.M. Bifunctional Ionic Liquids for the Multitask Fixation of Carbon Dioxide into Valuable Chemicals. ChemCatChem 2016, 8, 244–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagodzinski, T.S. Thioamides as Useful Synthons in the Synthesis of Heterocycles. Chem. Rev. 2003, 103, 197–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beletskaya, I.P.; Ananikov, V.P. Transition-Metal-Catalyzed C−S, C−Se, and C−Te Bond Formation via Cross-Coupling and Atom-Economic Addition Reactions. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 1596–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeni, G.; Lüdtke, D.S.; Panatieri, R.B.; Braga, A.L. Vinylic Tellurides: From Preparation to Their Applicability in Organic Synthesis. Chem. Rev. 2006, 106, 1032–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirth, T. Organoselenium Chemistry in Stereoselective Reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2000, 39, 3740–3749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santi, C.; Santoro, S.; Battistelli, B. Organoselenium Compounds as Catalysts in Nature and Laboratory. Curr. Org. Chem. 2010, 14, 2442–2462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, S.; Hazra, A.; Chakrabarty, R.; Fun, H.-K. Recognition of Carboxylate Anions and Carboxylic Acids by Selenium-Based New Chromogenic Fluorescent Sensor: A Remarkable Fluorescence Enhancement of Hindered Carboxylates. Org. Lett. 2009, 11, 4350–4353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasale, D.B.; Maity, I.; Das, A.K. In Situ Generation of Redox Active Peptides Driven by Selenoester Mediated Native Chemical Ligation. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 11397–11400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahuja, B.L.; Raykar, V.; Joshi, R.; Tiwari, S.; Talreja, S.; Choudhary, G. Electronic Properties and Momentum Densities of Tin Chalcogenides: Validation of PBEsol Exchange-Correlation Potential. Phys. B 2015, 465, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trost, B.M.; Waser, J.; Meyer, A. Total Synthesis of (−)-Pseudolaric Acid B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 14556–14557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wever, W.J.; Bogart, J.W.; Baccile, J.A.; Chan, A.N.; Schroeder, F.C.; Bowers, A.A. Chemoenzymatic Synthesis of Thiazolyl Peptide Natural Products Featuring an Enzyme-Catalyzed Formal [4+2] Cycloaddition. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 3494–3497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perin, G.; Barcellos, A.M.; Luz, E.Q.; Borges, E.L.; Jacob, R.G.; Lenardão, E.J.; Sancineto, L.; Santi, C. Green Hydroselenation of Aryl Alkynes: Divinyl Selenides as a Precursor of Resveratrol. Molecules 2017, 22, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perin, G.; Silva, C.M.; Borges, E.L.; Duarte, J.E.G.; Goulart, H.A.; Silva, R.B.; Schumacher, R.F. Selective Synthesis of 4-Thiomethyl-1,3-dioxolan-2-ones under Microwave Irradiation using an Environmentally Benign KF/Al2O3/PEG-400 System. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2016, 42, 5873–5885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenardão, E.J.; Soares, L.K.; Barcellos, A.M.; Perin, G. KF/Al2O3 as a Green System for the Synthesis of Organochalcogen Compounds. Curr. Green Chem. 2016, 3, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miralles, N.; Gómez, J.E.; Kleij, A.W.; Fernández, E. Copper-Mediated SN2′ Allyl–Alkyl and Allyl–Boryl Couplings of Vinyl Cyclic Carbonates. Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 6096–6099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Khan, S.; Zhao, C.; Mao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.J. Enantioselective Construction of Tertiary C–O Bond via Allylic Substitution of Vinylethylene Carbonates with Water and Alcohols. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 10733–10741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.F.; Neumann, H.; Beller, M. Synthesis of Heterocycles via Palladium-Catalyzed Carbonylations. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinchilla, R.; Najera, C. Chemicals from Alkynes with Palladium Catalysts. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 1783–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musaev, D.G.; Figg, T.M.; Kaledin, A.L. Versatile Reactivity of Pd-Catalysts: Mechanistic Features of the Mono-N-protected Amino Acid Ligand and Cesium-Halide Base in Pd-Catalyzed C–H Bond Functionalization. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 5009–5031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperger, T.; Sanhueza, I.A.; Kalvet, I.; Schoenebeck, F. Computational Studies of Synthetically Relevant Homogeneous Organometallic Catalysis Involving Ni, Pd, Ir, and Rh: An Overview of Commonly Employed DFT Methods and Mechanistic Insights. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 9532–9586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, L.; Liu, T.; Chang, X.; Guo, W. An Update of Transition Metal-Catalyzed Decarboxylative Transformations of Cyclic Carbonates and Carbamates. Molecules 2019, 24, 3930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fürstner, A. From Understanding to Prediction: Gold- and Platinum-Based π-Acid Catalysis for Target Oriented Synthesis. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014, 47, 925–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakati, N.; Maiti, J.; Lee, S.H.; Jee, S.H.; Viswanathan, B.; Yoon, Y.S. Anode Catalysts for Direct Methanol Fuel Cells in Acidic Media: Do We Have Any Alternative for Pt or Pt–Ru? Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 12397–12429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nie, Y.; Li, L.; Wei, Z. Recent Advancements in Pt and Pt-Free Catalysts for Oxygen Reduction Reaction. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 2168–2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, G.; Wang, F.; Li, X. C–C, C–O and C–N Bond Formation via Rhodium(III)-Catalyzed Oxidative C–H Activation. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 3651–3678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etayo, P.; Vidal-Ferran, A. Rhodium-Catalysed Asymmetric Hydrogenation as a Valuable Synthetic Tool for the Preparation of Chiral Drugs. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 728–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, B.; Cramer, N. Chiral Cyclopentadienyls: Enabling Ligands for Asymmetric Rh(III)-Catalyzed C–H Functionalizations. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48, 1308–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, W.; Wang, W.; Lu, K.; Yao, W.; Xue, F.; Ma, M. Magnesium-Catalyzed Hydroboration of Organic Carbonates, carbon Dioxide and Esters. Dalton Trans. 2020, 49, 2776–2780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

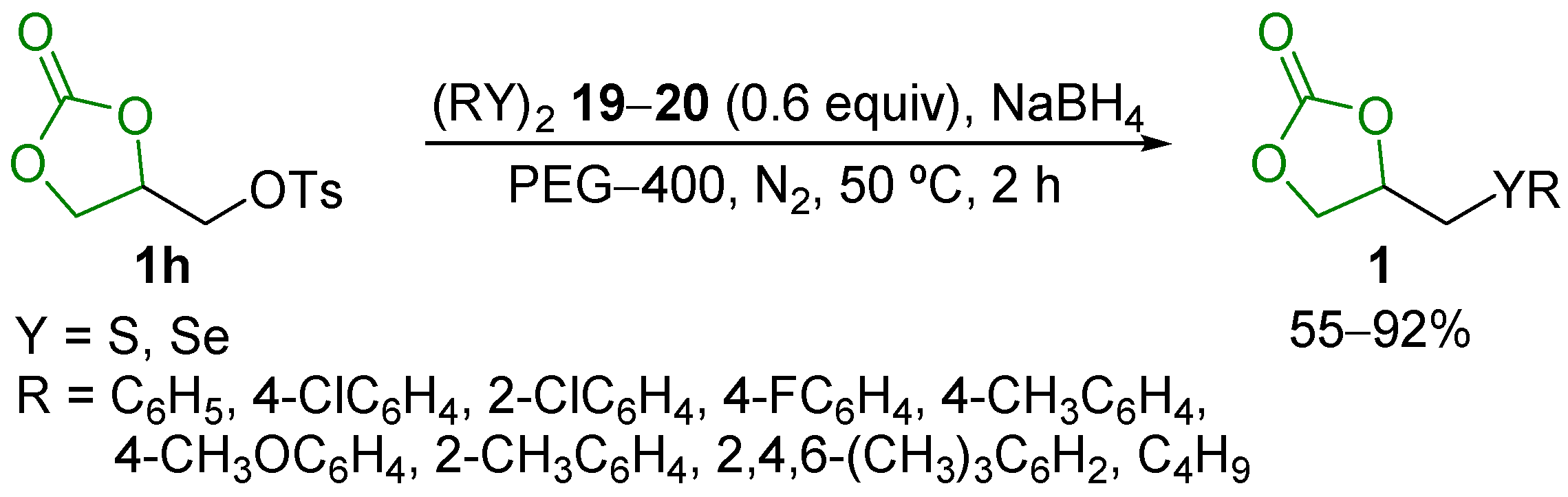

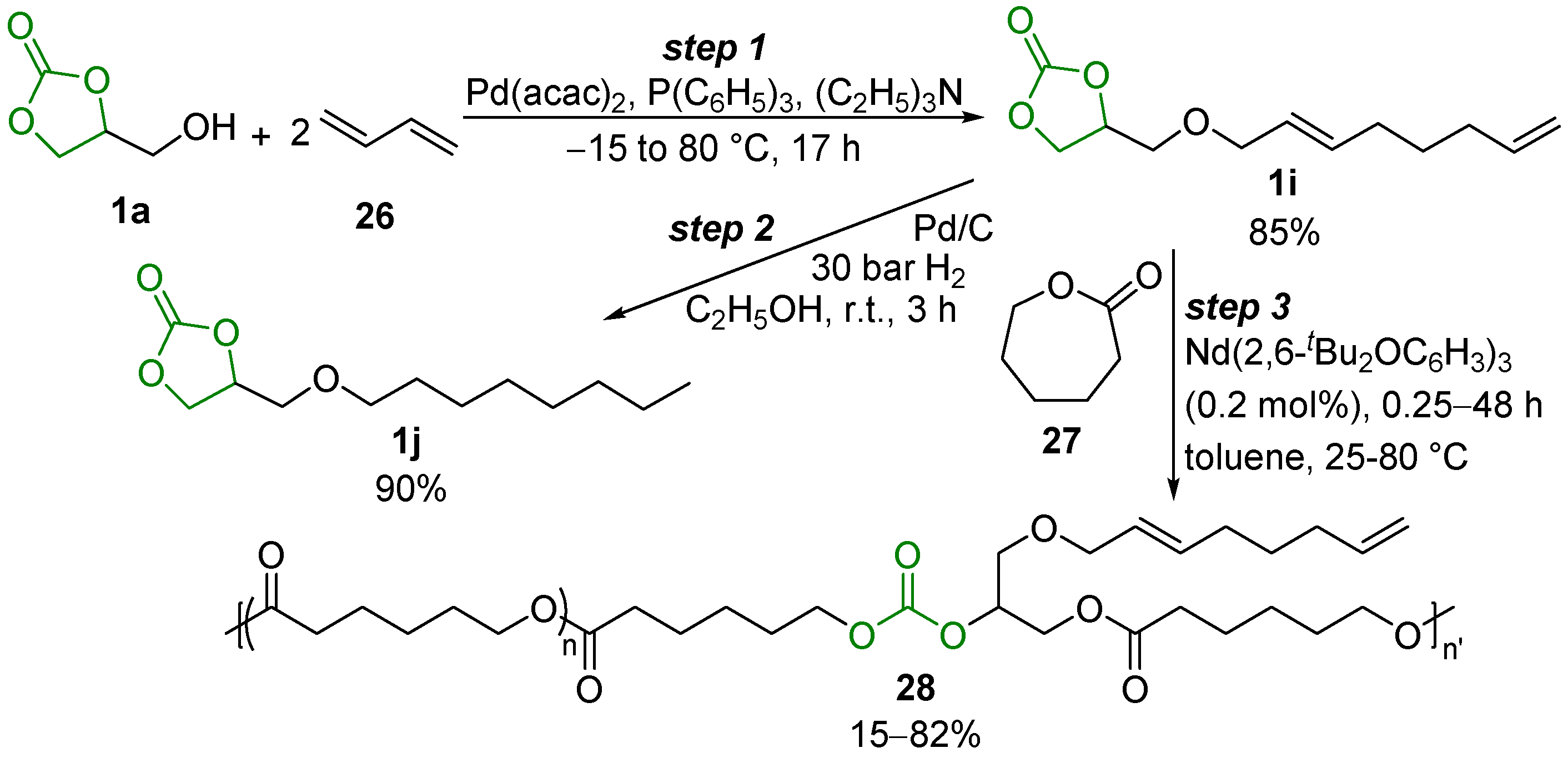

- Ibn El Alami, M.S.; Suisse, I.; Fadlallah, S.; Sauthier, M.; Visseaux, M.C.R. Telomerization of 1,3-Butadiene with Glycerol Carbonate and Subsequent Ring-Opening Lactone Co-polymerization. Chimie 2016, 19, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Liu, T.-X.; Ru, Y.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, G. Palladium-Catalyzed Decarboxylative Heterocyclizations of [60]Fullerene: Preparation of Novel Vinyl-substituted [60]Fullerene-fused Tetrahydrofurans/Pyrans/Quinolines. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 14498–14501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singha, S.; Patra, T.; Daniliuc, C.G.; Glorius, F. Highly Enantioselective [5+2] Annulations through Cooperative N-Heterocyclic Carbene (NHC) Organocatalysis and Palladium Catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 3551–3554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, Z.-Q.; Yang, L.-C.; Liu, S.; Yu, Z.; Wang, Y.-N.; Tan, Z.Y.; Huang, R.-Z.; Lan, Y.; Zhao, Y. Nine-Membered Benzofuran-Fused Heterocycles: Enantioselective Synthesis by Pd-Catalysis and Rearrangement via Transannular Bond Formation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 15304–15307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, C.; Shah, B.H.; Khan, I.; Kan, Y.; Zhang, Y. Enantioselective Synthesis of Isoxazoline N-Oxides via Pd-Catalyzed Asymmetric Allylic Cycloaddition of Nitro-Containing Allylic Carbonates. J. Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 9045–9049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, C.; Khan, I.; Zhang, Y.J. Enantioselective Total Synthesis of Furofuran Lignans via Pd-Catalyzed Asymmetric Allylic Cycloadditon of Vinylethylene Carbonates with 2-Nitroacrylates. Chem. Commun. 2020, 56, 12431–12434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, P.; Gondo, S.; Nagender, P.; Uno, H.; Tokunaga, E.; Shibata, N. Access to Benzo-fused Nine-membered Heterocyclic Alkenes with a Trifluoromethyl Carbinol Moiety via a Double Decarboxylative Formal Ring-Expansion Process under Palladium Catalysis. Chem. Sci. 2018, 9, 3276–3281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Martínez-Rodríguez, L.; Martin, E.; Escudero-Adán, E.C.; Kleij, A.W. Highly Efficient Catalytic Formation of (Z)-1,4-But-2-ene Diols Using Water as a Nucleophile. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 11037–11040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Breit, B. Rhodium-Catalyzed Dynamic Kinetic Asymmetric Allylation of Phenols and 2-Hydroxypyridines. Chem. Eur. J. 2016, 22, 14655–14663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szewczyk, M.; Magre, M.; Zubar, V.; Rueping, M. Reduction of Cyclic and Linear Organic Carbonates Using a Readily Available Magnesium Catalyst. ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 11634–11639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, X.; Xu, J.; Zhang, L.; Xu, C.; Pan, Y.; Xu, L.; Li, H.; Zhang, W. Rhodium(III)-Catalyzed Direct C-H Olefination of Arenes with Aliphatic Olefins. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2016, 358, 573–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Klauck, F.J.R.; Glorius, F. Manganese-Catalyzed Allylation via Sequential C–H and C–C/C–Het Bond Activation. Chem. Sci. 2017, 8, 3379–3383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tortoreto, C.; Achard, T.; Egger, L.; Guénée, L.; Lacour, J. Synthesis of Spiro Ketals, Orthoesters, and Orthocarbonates by CpRu-Catalyzed Decomposition of α-Diazo-β-ketoesters. Org. Lett. 2016, 18, 240–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annunziata, L.; Fouquay, S.; Michaud, G.; Simon, F.; Guillaume, S.M.; Carpentier, J.-F. Mono- and Di-cyclocarbonate Telechelic Polyolefins Synthesized from ROMP Using Glycerol Carbonate Derivatives as Chain-transfer Agents. Polym. Chem. 2013, 4, 1313–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yagci, Y.; Nuyken, O.; Graubner, V.-M. Encyclopedia of Polymer Science and Technology. In Telechelic Polymers; Wiley Online Library: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuciński, K.; Szudkowska-Frątczak, J.; Hreczycho, G. Pt-Catalyzed Synthesis of Functionalized Symmetrical and Unsymmetrical Disilazanes. Chem. Eur. J. 2016, 22, 13046–13049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, X.; Chen, J.; Zhu, W.; Zhu, W.; Cheng, K.; Liu, Y.; Su, W.-K.; Yu, C.J. Cobalt(III)-Catalyzed Fast and Solvent-Free C–H Allylation of Indoles Using Mechanochemistry. Org. Chem. 2017, 82, 10665–10672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bensemhoun, J.; Condon, S. Valorization of Glycerol 1,2-Carbonate as a Precursor for the Development of New Synthons in Organic Chemistry. Green Chem. 2012, 14, 2595–2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singha, S.; Serrano, E.; Mondal, S.; Daniliuc, C.G.; Glorius, F. Diastereodivergent Synthesis of Enantioenriched α,β-Disubstituted γ-Butyrolactones via Cooperative N-Heterocyclic Carbene and Ir Catalysis. Nat. Catal. 2020, 3, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kargar, M.; Hekmatshoar, R.; Ghandi, M.; Mostashari, A. Use of Glycerol Carbonate in an Efficient, One-Pot and Solvent Free Synthesis of 1,3-sn-Diglycerides. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2012, 90, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Antonietti, M. Poly(ionic liquid)s: Polymers Expanding Classical Property Profiles. Polymer 2011, 52, 1469–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Mecerreyes, D.; Antonietti, M. Poly(ionic liquid)s: An Update. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2013, 38, 1009–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, B.; Elageed, E.H.M.; Qin, L.; Ni, B.; Liu, X.; Gao, G. Swelling Poly(ionic liquid)s: Synthesis and Application as Quasi-Homogeneous Catalysts in the Reaction of Ethylene Carbonate with Aniline. ACS Macro Lett. 2016, 5, 435–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truscello, A.M.; Gambarotti, C.; Lauria, M.; Auricchio, S.; Leonardi, G.; Shisodia, S.U.; Citterio, A. One-pot synthesis of aryloxypropanediols from glycerol: Towards valuable chemicals from renewable sources. Green Chem. 2013, 15, 625–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, S.-C.; Lin, Y.-C.; Ryu, I.; Wu, Y.-K. Revisiting Hydroxyalkylation of Phenols with Cyclic Carbonates. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2019, 361, 3639–3644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsén, P.; Oschmann, M.; Johnston, E.V.; Åkermark, B. Synthesis of Highly Functional Carbamates Through Ring-Opening of Cyclic Carbonates with Unprotected α-Amino Acids in Water. Green Chem. 2018, 20, 469–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chai, J.; You, C.; Zhang, J.; Mi, X.; Zhang, L.; Luo, S. π-Coordinating Chiral Primary Amine/Palladium Synergistic Catalysis for Asymmetric Allylic Alkylation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 3184–3195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tillet, G.; Boutevin, B.; Ameduri, B. Chemical Reactions of Polymer Crosslinking and Post-crosslinking at Room and Medium Temperature. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2011, 36, 191–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, P.D.; Monge, S.; Lapinte, V.; Raoul, Y.; Robin, J.J. Glycerol-based Co-oligomers by Free-radical Chain Transfer Polymerization: Towards Reactive Polymers bearing Acetal and/or Carbonate Groups with Enhanced Properties. Eur. Polym. J. 2017, 95, 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rotta, J.; Pham, P.D.; Lapinte, V.; Borsali, R.; Minatti, E.; Robin, J.-J. Synthesis of Amphiphilic Polymers Based on Fatty Acids and Glycerol-Derived Monomers—A Study of Their Self-Assembly in Water. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2014, 215, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamiye, R.; Alaaeddine, A.; Awada, M.; Campagne, B.; Caillol, S.; Guillaume, S.M.; Ameduri, B.; Carpentier, J.-F. From Glycidyl Carbonate to Hydroxyurethane Side-groups in Alternating Fluorinated Copolymers. Polym. Chem. 2014, 5, 5089–5099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheen, U.; Turney, T.W.; Saito, K.; Gates, W.P.; Patti, A.F. Pendant Cyclic Carbonate-polymer/Na-Smectite Nanocomposites via In Situ Intercalative Polymerization and Solution Intercalation. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 2016, 54, 2421–2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

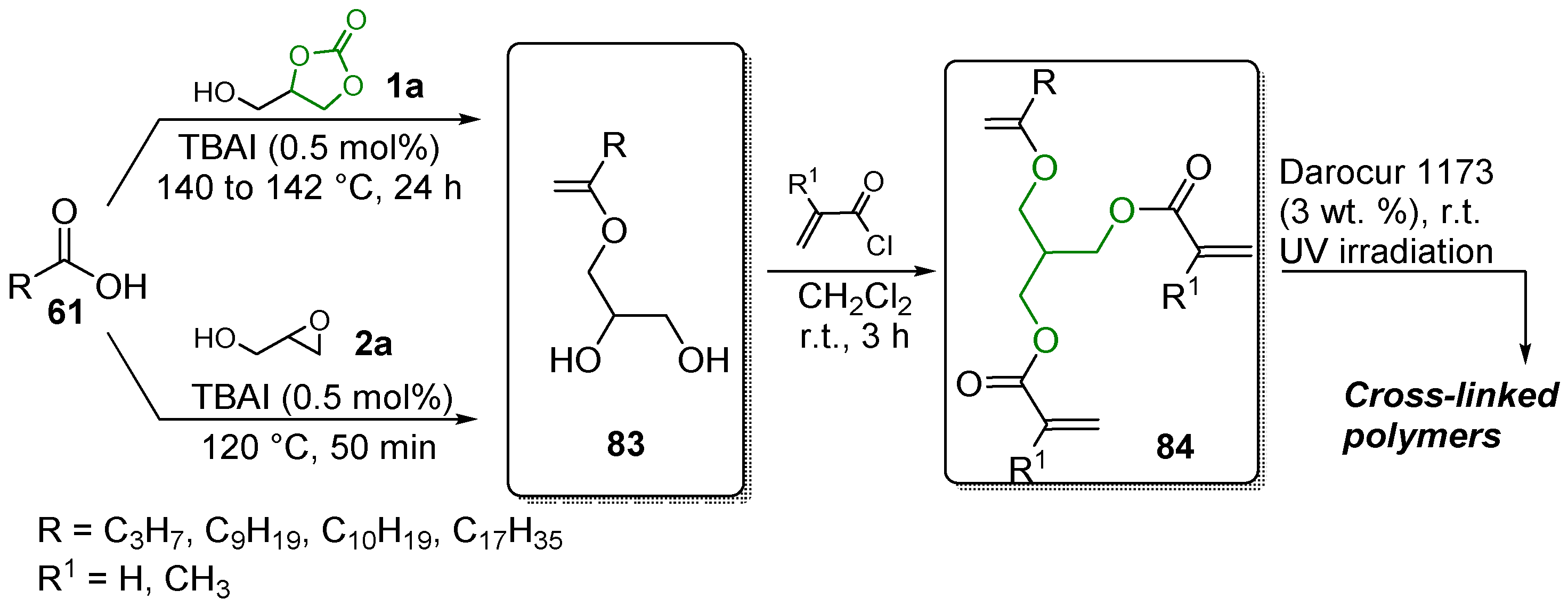

- Mhanna, A.; Sadaka, F.; Boni, G.; Brachais, C.-H.; Brachais, L.; Couvercelle, J.-P.; Plasseraud, L.; Lecamp, L. Photopolymerizable Synthons from Glycerol Derivatives. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2014, 91, 337–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, P.; Coulembier, O.; Raquez, J.-M. Handbook of Ring-Opening Polymerization; WILEY-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Clements, J.H. Reactive Applications of Cyclic Alkylene Carbonates. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2003, 42, 663–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, N.; Seidi, F.; Crespy, D.; D’Elia, V. Polymers Based on Cyclic Carbonates as Trait d’Union Between Polymer Chemistry and Sustainable CO2 Utilization. ChemSusChem 2019, 12, 724–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, R.M.; Hong, H.; Chai, C.L.L.; Ghanwat, A.A.; Ganugapati, S.; Gnaneshwar, R. Synthesis and Characterization of α-(Cyclic Carbonate), ω-Hydroxyl/Itaconic Acid Asymmetric Telechelic Poly(ε-caprolactone). Polym. Bull. 2015, 72, 2489–2501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapiti, G.; Keul, H.; Möller, M. Functional PEG Building Blocks via Copolymerization of Ethylene Carbonate and tert-Butyl Glycidyl Ether. Polym. Chem. 2016, 7, 5050–5059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, K.E.; Navarro, R.; Ramírez-Hernández, F.; Marcos-Fernández, Á. New Routes to Difunctional Macroglycols Using Ethylene Carbonate: Reaction with Bis-(2-hydroxyethyl) Terephthalate and Degradation of Poly(Ethylene Terephthalate). Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2017, 144, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, P.S.; Aroua, M.K.; Daud, W.M.A.W. Conversion of Crude and Pure Glycerol into Derivatives: A Feasibility Evaluation. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 63, 533–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, A.G.; Gandini, A. Turning Polysaccharides into Hydrophobic Materials: A Critical Review. Part 2. Hemicelluloses, Chitin/Chitosan, Starch, Pectin and Alginates. Cellulose 2010, 17, 1045–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akil, Y.; Lorenz, D.; Lehnen, R.; Saake, B. Safe and Non-toxic Hydroxyalkylation of Xylan Using Propylene Carbonate. Eur. Polym. J. 2016, 77, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akil, Y.; Lehnen, R.; Saake, B. Novel Synthesis of Hydroxyvinylethyl Xylan Using 4-Vinyl-1,3-dioxolan-2-one. Tetrahedron Lett. 2016, 57, 4200–4202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

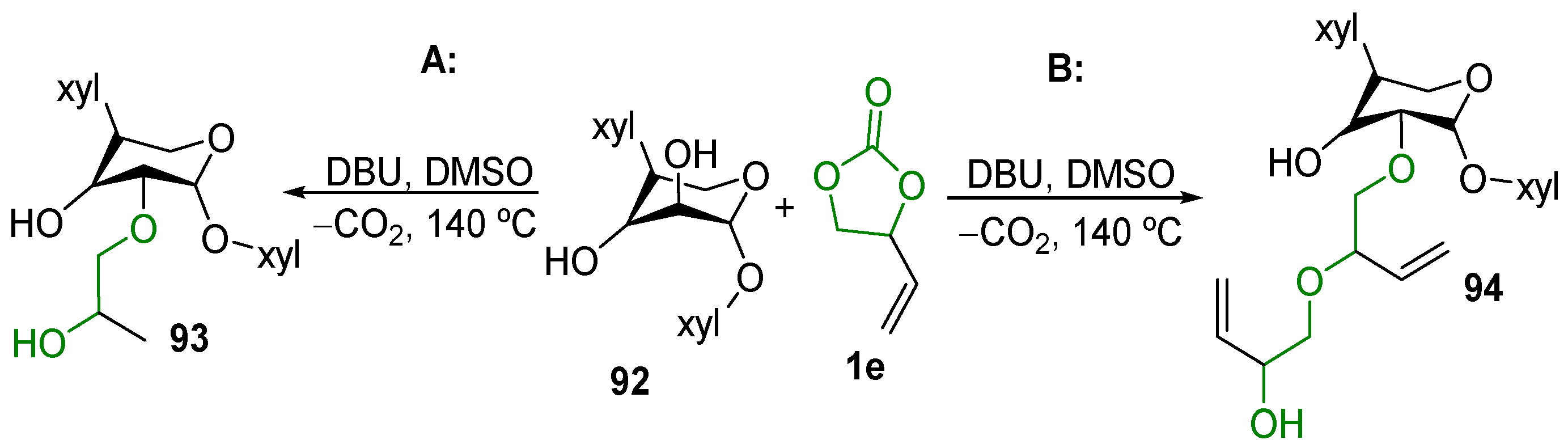

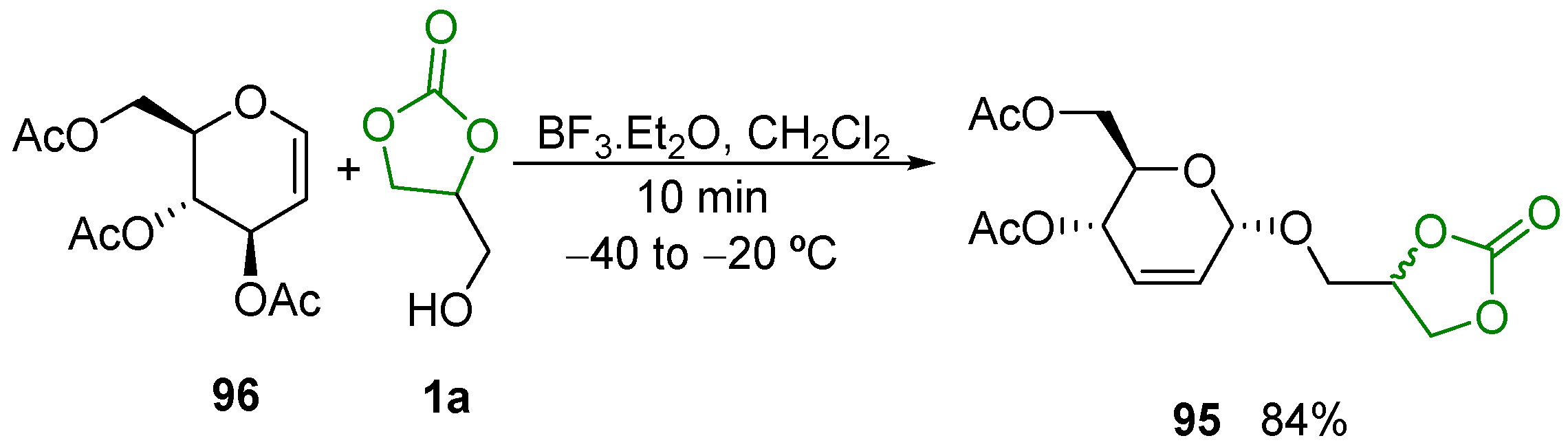

- Costa, P.L.F.; Melo, V.N.; Guimarães, B.M.; Schuler, M.; Pimenta, V.; Rollin, P.; Tatibouët, A.; Oliveira, R.N. Glycerol Carbonate in Ferrier Reaction: Access to New Enantiopure Building Blocks to Develop Glycoglycerolipid Analogues. Carbohydr. Res. 2016, 436, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitaku, E.; Smith, D.T.; Njardarson, J.T. Analysis of the Structural Diversity, Substitution Patterns, and Frequency of Nitrogen Heterocycles among U.S. FDA Approved Pharmaceuticals. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 10257–10274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neha; Dwivedi, A.R.; Kumar, R.; Kumar, V. Recent Synthetic Strategies for Monocyclic Azole Nucleus and Its Role in Drug Discovery and Development. Curr. Org. Synth. 2018, 15, 321–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eicher, T.; Hauptmann, S. The Chemistry of Heterocycles; Wiley/VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2003. [Google Scholar]

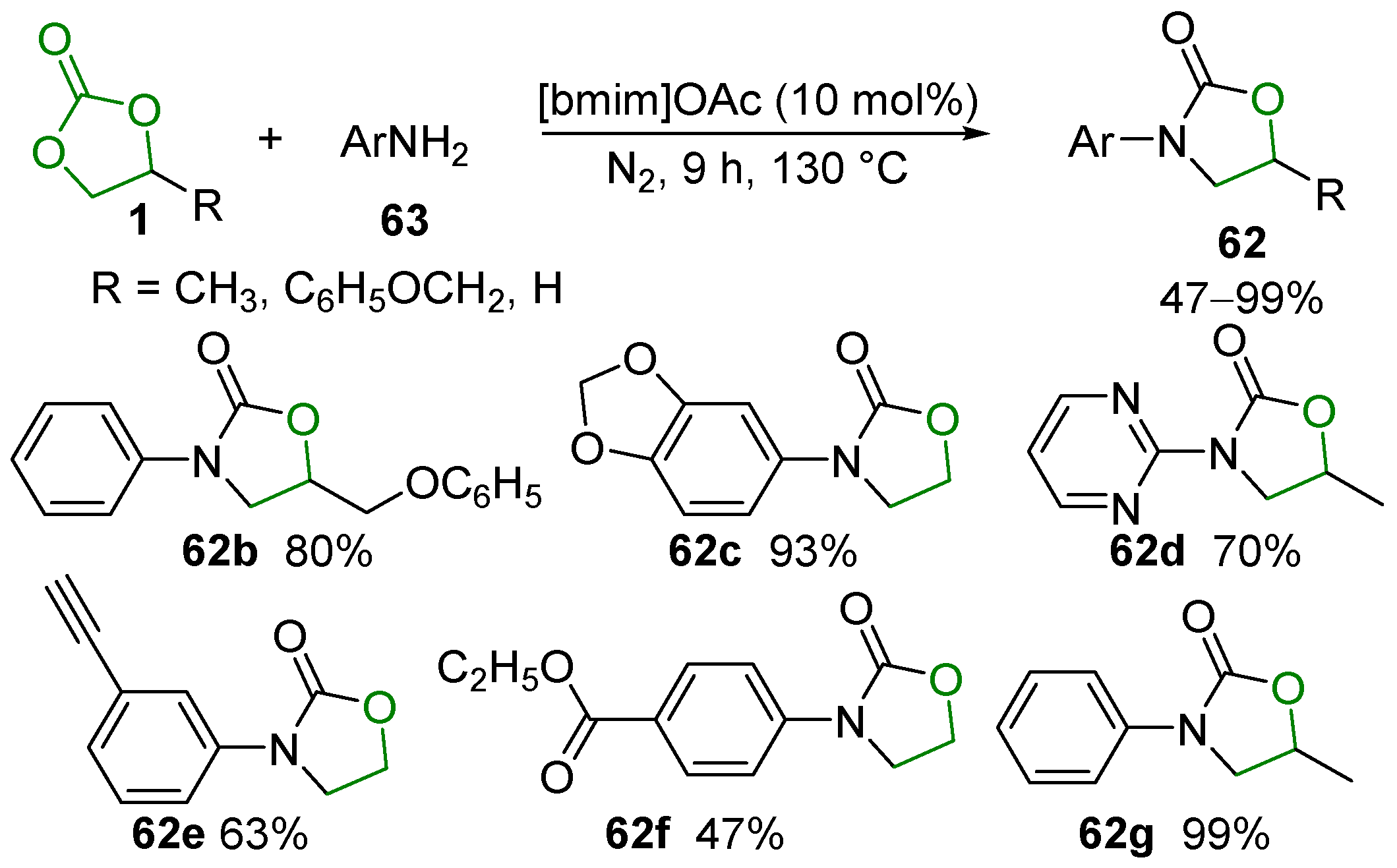

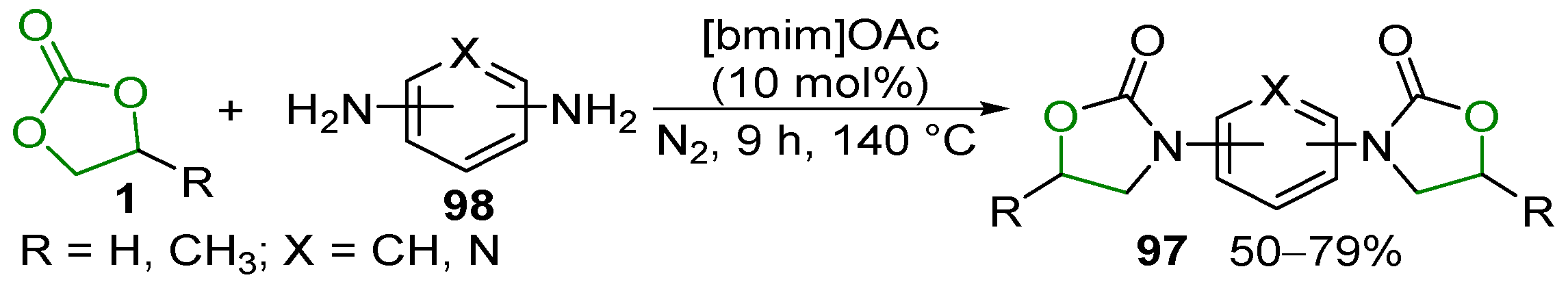

- Wang, B.; Yang, S.; Min, L.; Gu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, X.; Zhang, L.; Elageed, E.H.M.; Wu, S.; Gao, G. Eco-Efficient Synthesis of Cyclic Carbamates/Dithiocarbonimidates from Cyclic Carbonates/Trithiocarbonate and Aromatic Amines Catalyzed by Ionic Liquid BmimOAc. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2014, 356, 3125–3134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

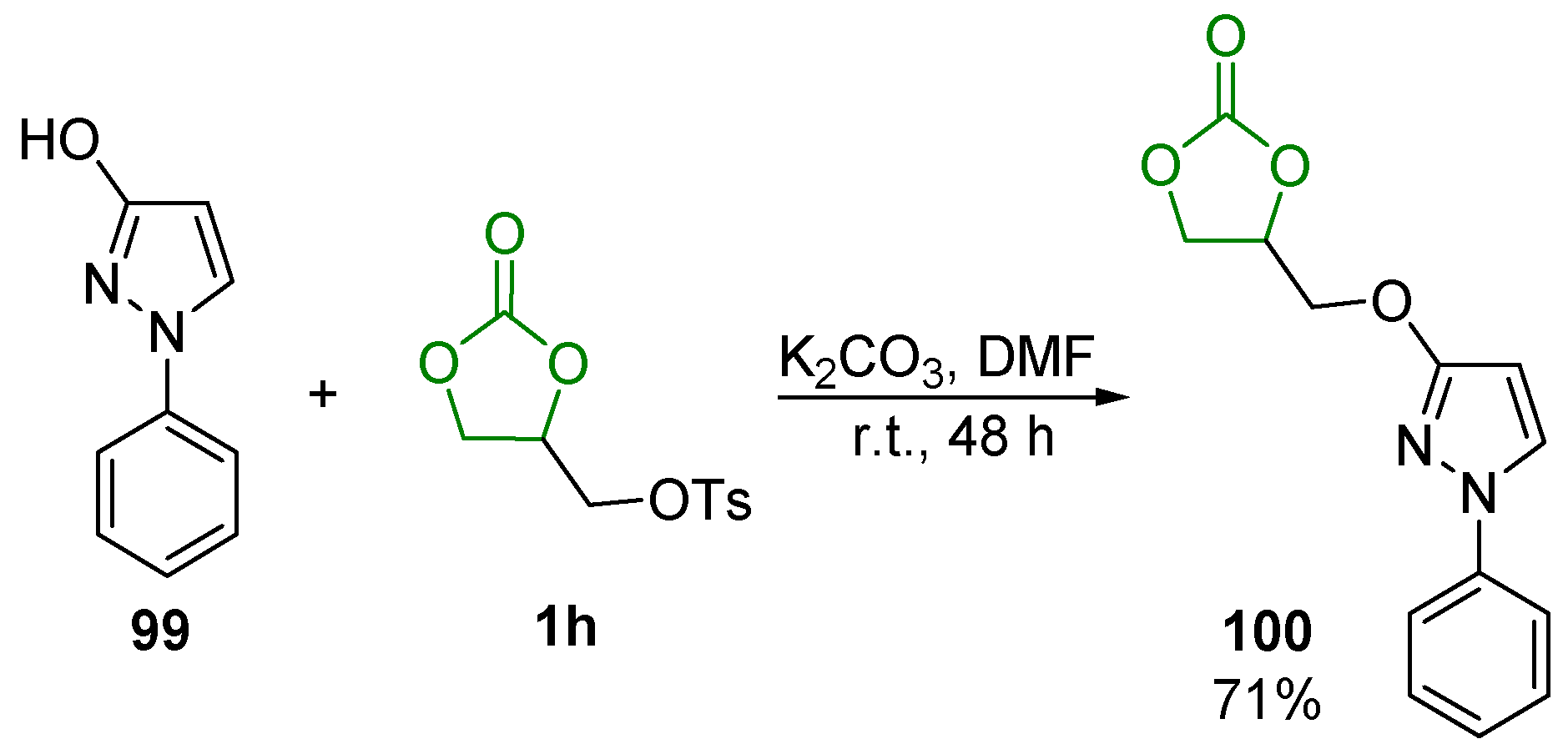

- Vilkauskaitė, G.; Holzer, W.; Šačkus, A. 4-{[(1-Phenyl-1H-pyrazol-3-yl)oxy]methyl}-1,3-dioxolan-2-one. Molbank 2012, 2012, M786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zidar, N.; Tomašič, T.; Macut, H.; Sirc, A.; Brvar, M.; Montalvão, S.; Tammela, P.; Ilaš, J.; Kikelj, D. New N-Phenyl-4,5-dibromopyrrolamides and N-Phenylindolamides as ATPase Inhibitors of DNA Gyrase. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 117, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, H.; Han, S.; Park, J.; Choi, M.; Han, S.H.; Jeong, T.; Lee, S.-Y.; Kwak, J.H.; Jung, Y.H.; Kim, I.S. Rhodium(III)-Catalyzed Heteroatom-directed C–H Allylation with Allylic Phosphonates and Allylic Carbonates at Room Temperature. Tetrahedron 2016, 72, 571–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosling, S.; El Amri, C.; Tatibouët, A. Staudinger Condensation for the Preparation of Thiohydantoins. Synthesis 2014, 46, 1079–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.-C.; Rong, Z.-Q.; Wang, Y.-N.; Tan, Z.Y.; Wang, M.; Zhao, Y. Construction of Nine-Membered Heterocycles through Palladium-Catalyzed Formal [5+4] Cycloaddition. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 2927–2931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.-C.; Tan, Z.Y.; Rong, Z.-Q.; Liu, R.; Wang, Y.-N.; Zhao, Y. Palladium-Titanium Relay Catalysis Enables Switch from Alkoxide-pAllyl to Dienolate Reactivity for Spiro-Heterocycle Synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 7860–7864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, C.; Wu, Y.; Wang, D.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, C.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, C.; Song, B.; Guo, H. Formal [5+3] Cycloaddition of Zwitterionic Allylpalladium Intermediates with Azomethine Imines for Construction of N,O-Containing Eight-Membered Heterocycles. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2018, 360, 652–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Lorion, M.M.; Ackermann, L. Air-Stable Manganese(I)-Catalyzed C-H Activation for Decarboxylative C-H/C-O Cleavages in Water. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 6339–6342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Lorion, M.M.; Ackermann, L. Domino C–H/N–H Allylations of Imidates by Cobalt Catalysis. ACS Catal. 2017, 7, 3430–3433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, X.-D.; Li, Z.-M.; He, L.-N. Protic Ionic Liquid-Catalyzed Synthesis of Oxazolidinones Using Cyclic Carbonates as both CO2 Surrogate and Sustainable Solvent. Catal. Today 2019, 324, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

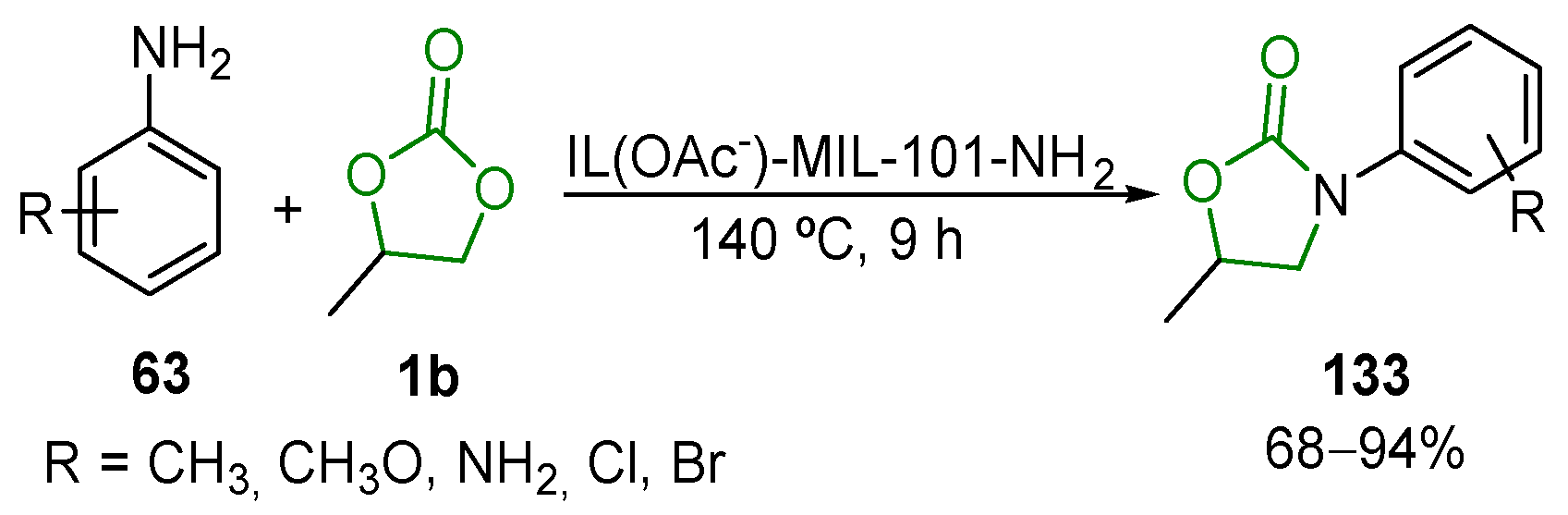

- Ji, M.; Lv, H.Y.; Cheng, L.C.; Wang, T.T.; Chong, S.Y. Metal-Organic Framework MIL-101-NH2-Supported Acetate-Based Butylimidazolium Ionic Liquid as a Highly Efficient Heterogeneous Catalyst for the Synthesis of 3-Aryl-2-oxazolidinones. Langmuir 2019, 35, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

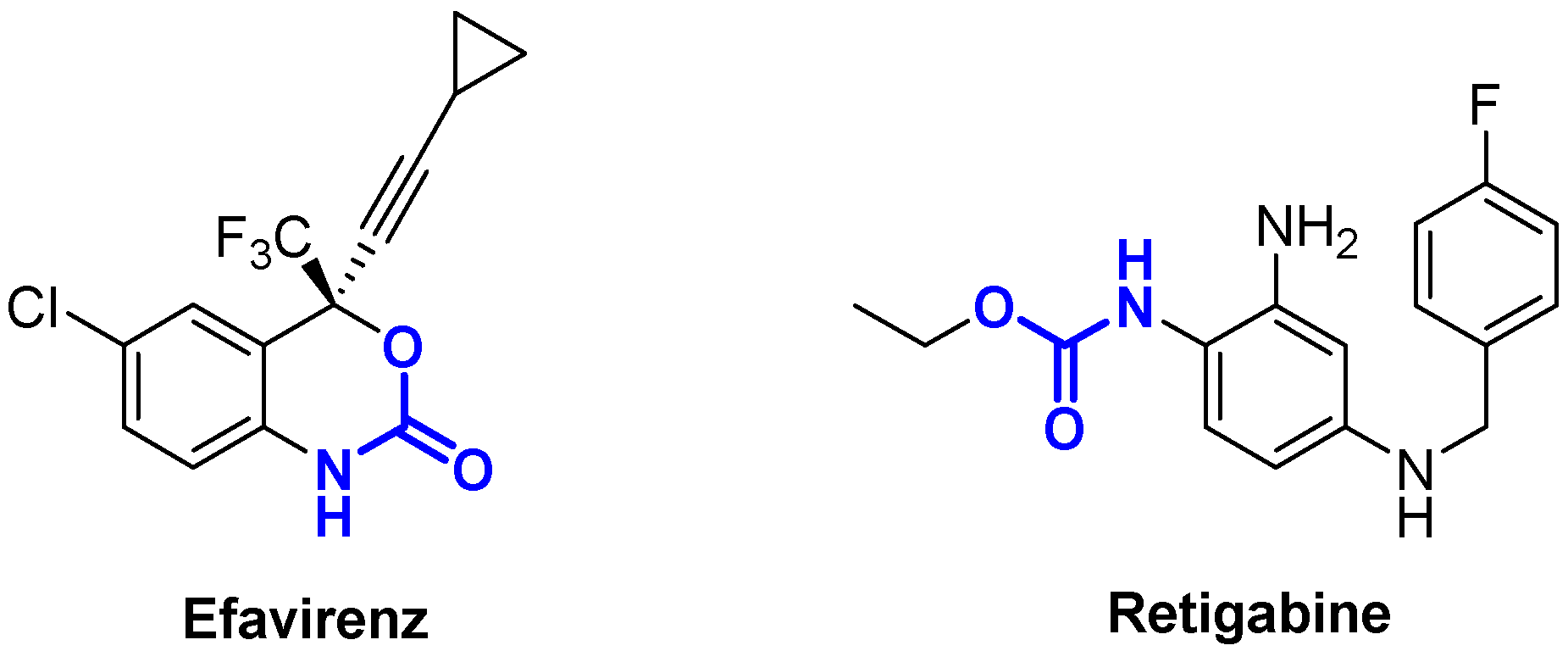

- Rakhmaninam, N.Y.; van den Anker, J.N. Efavirenz in the Therapy of HIV Infection. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2010, 6, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Splinter, M.Y. Ezogabine (Retigabine) and its Role in the Treatment of Partial-onset Seizures: A Review. Clin. Ther. 2012, 34, 1845–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, S.L.; Guan, J. Advances in Polyurethane Biomaterials; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2016; ISBN 9780081006221. [Google Scholar]

- Ochiai, B.; Koda, K.; Endo, T. Branched Cationic Polyurethane Prepared by Polyaddition of Chloromethylated Five-Membered Cyclic Carbonate and Diethylenetriamine in Molten Salts. J. Polym. Sci. A Polym. Chem. 2012, 50, 47–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Heine, E.; Keusgen, N.; Keul, H.; Möller, M. Synthesis and Characterization of Amphiphilic Monodisperse Compounds and Poly(Ethylene Imine)s: Influence of their Microstructures on the Antimicrobial Properties. Biomacromolecules 2012, 13, 612–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

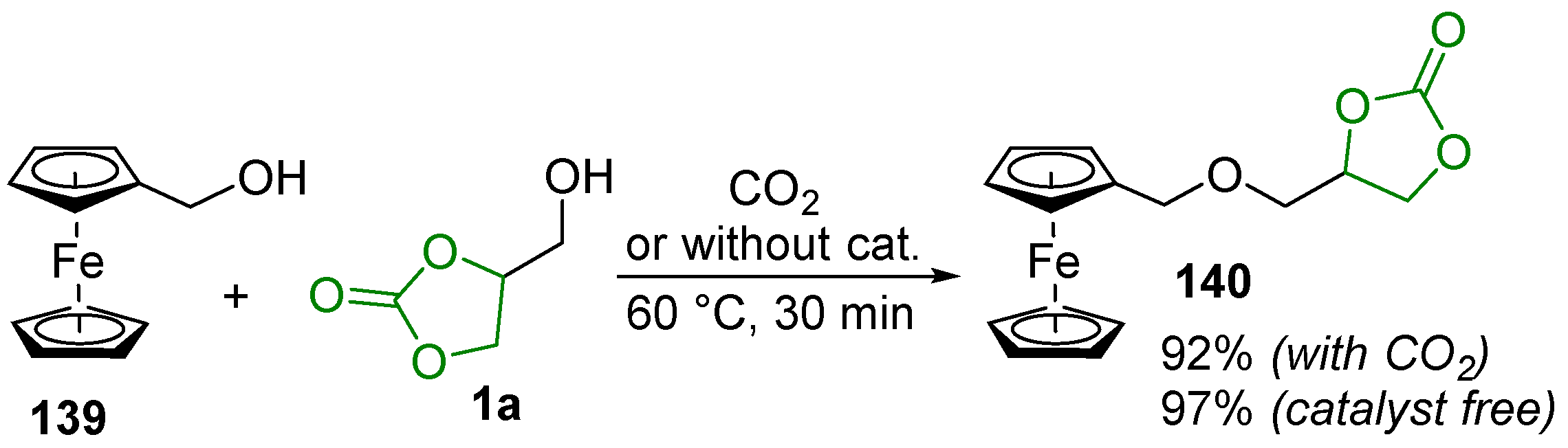

- Shisodia, S.U.; Auricchio, S.; Citterio, A.; Grassi, M.; Sebastiano, R. New Examples of Template Catalysis based Processes: Glycerol-like Units as Efficient Promoters for Dehydrative Nucleophilic Substitutions of Ferrocenylmethanol. Tetrahedron Lett. 2014, 55, 869–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Gong, L.; Zhang, X. Copper-Catalyzed Enantioselective Synthesis of β-Amino Alcohols Featuring Tetrasubstituted Tertiary Carbons. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2018, 360, 2055–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinch, M.S.; Patridge, E. An Analysis of FDA-Approved Drugs for Infectious Disease: HIV/AIDS Drugs. Drug Discov. Today 2014, 19, 1510–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemitson, I. Castable Polyurethane Elastomers; CRC Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Suryawanshi, Y.; Sanap, P.; Wani, V. Advances in the Synthesis of Non-isocyanate Polyurethanes. Polym. Bull. 2018, 76, 3233–3246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnenschein, M.F. Polyurethanes—Science, Technology, Markets and Trends; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ghasemlou, M.; Daver, F.; Ivanova, E.P.; Adhikari, B. Bio-based Routes to Synthesize Cyclic Carbonates and Polyamines Precursors of Non-isocyanate Polyurethanes: A review. Eur. Polym. J. 2019, 118, 668–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monie, F.; Grignard, B.; Thomassin, J.-M.; Mereau, R.; Tassaing, T.; Jerome, C.; Detrembleur, C. Chemo- and Regioselective Additions of Nucleophiles to Cyclic Carbonates for the Preparation of Self-Blowing Non-Isocyanate Polyurethane Foams. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 17033–17041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nohra, B.; Candy, L.; Blanco, J.F.; Raoul, Y.; Mouloungui, Z. Synthesis of Five and Six-membered Cyclic Glycerilic Carbonates bearing Exocyclic Urethane Functions. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2013, 115, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassam, N.; Laure, C.; Jean-François, B.; Yann, R.; Zephirin, M. Aza-Michael versus Aminolysis Reactions of Glycerol Carbonate Acrylate. Green Chem. 2013, 15, 1900–1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nohra, B.; Candy, L.; Blanco, J.-F.; Raoul, Y.; Mouloungui, Z. Aminolysis Reaction of Glycerol Carbonate in Organic and Hydroorganic Medium. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2012, 89, 1125–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardo, V.M.; Dhulst, E.A.; Leitsch, E.K.; Wilmot, N.; Heath, W.H.; Gies, A.P.; Miller, M.D.; Torkelson, J.M.; Scheidt, K.A. Cooperative Catalysis of Cyclic Carbonate Ring Opening: Application Towards Non-Isocyanate Polyurethane Materials. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 2015, 2791–2795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Velthoven, J.L.J.; Gootjes, L.; Van Es, D.S.; Noordover, B.A.J.; Meuldijk, J. Poly(Hydroxy Urethane)s Based on Renewable Diglycerol Dicarbonate. Eur. Polym. J. 2015, 70, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blain, M.; Yau, H.; Jean-Gérard, L.; Auvergne, R.; Benazet, D.; Schreiner, P.R.; Caillol, S.; Andrioletti, B. Urea- and Thiourea- Catalyzed Aminolysis of Carbonates. ChemSusChem 2016, 9, 2269–2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Saito, R. Polyurethane-Silica Nanocomposites Provided from Perhydropolysilazane: Polymerization Mechanism. Polymer (Guildf) 2018, 135, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annunziata, L.; Diallo, A.K.; Fouquay, S.; Michaud, G.; Simon, F.; Brusson, J.M.; Carpentier, J.F.; Guillaume, S.M. α,ω-Di(glycerol arbonate) Telechelic Polyesters and Polyolefins as Precursors to Polyhydroxyurethanes: An Isocyanate-free Approach. Green Chem. 2014, 16, 1947–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aricò, F.; Bravo, S.; Crisma, M.; Tundo, P. 1,3-Oxazinan-2-ones via Carbonate Chemistry: A Facile, High Yielding Synthetic Approach. Pure Appl. Chem. 2016, 88, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, C.; Zhao, Y.; Zou, K.; Cao, C.; Pang, G.; Shi, Y. Synthesis of N-Aryl-2-oxazolidinones from Cyclic Carbonates and Aromatic Amines Catalyzed by Bio-catalyst. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2018, 44, 2179–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blain, M.; Jean-Gérard, L.; Auvergne, R.; Benazet, D.; Caillol, S.; Andrioletti, B. Rational Investigations in the Ring Opening of Cyclic Carbonates by Amines. Green Chem. 2014, 16, 4286–4291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mommer, S.; Lamberts, K.; Keul, H.; Möller, M. A Novel Multifunctional Coupler: The Concept of Coupling and Proof of Principle. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 3288–3290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Legros, V.; Taing, G.; Buisson, P.; Schuler, M.; Bostyn, S.; Rousseau, J.; Sinturel, C.; Tatibouët, A. Activated Glycerol Carbonates, Versatile Reagents with Aliphatic Amines: Formation and Reactivity of Glycidyl Carbamates and Trialkylamines. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 2017, 5032–5043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magliozzi, F.; Chollet, G.; Grau, E.; Cramail, H. Benefit of the Reactive Extrusion in the Course of Polyhydroxyurethanes Synthesis by Aminolysis of Cyclic Carbonates. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 17282–17292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quérette, T.; Fleury, E.; Sintes-Zydowicz, N. Non-isocyanate Polyurethane Nanoparticles Prepared by Nanoprecipitation. Eur. Polym. J. 2019, 114, 434–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quienne, B.; Kasmi, N.; Dieden, R.; Caillol, S.; Habibi, Y. Isocyanate-Free Fully Biobased Star Polyester-Urethanes: Synthesis and Thermal Properties. Biomacromolecules 2020, 21, 1943–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pyo, K.-h.; Lee, D.H.; Kim, Y.; Kim, J.-W. Extremely Rapid and Simple Healing of a Transparent Conductor Based on Ag Nanowires and Polyurethane with a Diels-Alder Network. J. Mater. Chem. C 2016, 4, 972–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaratrotkamjorn, R.; Nourry, A.; Pasetto, P.; Choppé, E.; Panwiriyarat, W.; Tanrattanakul, V.; Pilard, J.-F. Synthesis and Characterization of Elastomeric, Biobased, Nonisocyanate Polyurethane from Natural Rubber. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2017, 134, 45427–45439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rix, E.; Grau, E.; Chollet, G.; Cramail, H. Synthesis of Fatty Acid-based Non-isocyanate Polyurethanes, NIPUs, in Bulk and Mini-Emulsion. Eur. Polym. J. 2016, 84, 863–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y.M.; Shen, G.R.; He, J.; Li, Y.S. Water-soluble Hyperbranched Poly(Ester Urethane)s Based on D,L-Alanine: Isocyanate-free Synthesis, Post-functionalization and Application. Green Chem. 2012, 14, 2243–2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besse, V.; Camara, F.; Méchin, F.; Fleury, E.; Caillol, S.; Pascault, J.P.; Boutevin, B. How to Explain Low Molar Masses in PolyHydroxyUrethanes (PHUs). Eur. Polym. J. 2015, 71, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Nelson, A.M.; Talley, S.J.; Chen, M.; Margaretta, E.; Hudson, A.G.; Moore, R.B.; Long, T.E. Non-isocyanate Poly(Amide-hydroxyurethane)s from Sustainable Resources. Green Chem. 2016, 18, 4667–4681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambeth, R.H.; Rizvi, A. Mechanical and Adhesive Properties of Hybrid Epoxy-Polyhydroxyurethane Network Polymers. Polymer 2019, 183, 121881–121888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Wu, Z.; Tang, L.; Qu, J. Preparation of Five-membered Bis(Cyclic Carbonate)s at Atmospheric Pressure for Polyhydroxyurethane Coatings. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2019, 136, 47957–47965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Tang, L.; Dai, J.; Qu, J. Synthesis and Properties of Aqueous Cyclic Carbonate Dispersion and Nonisocyanate Polyurethanes under Atmospheric Pressure. Prog. Org. Coat. 2019, 136, 105209–105217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duval, C.; Kébir, N.; Jauseau, R.; Burel, F. Organocatalytic Synthesis of Novel Renewable Non-isocyanate Polyhydroxyurethanes. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 2016, 54, 758–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleischer, M.; Blattmann, H.; Mülhaupt, R. Glycerol-, Pentaerythritol- and Trimethylolpropane-based Polyurethanes and their Cellulose Carbonate Composites Prepared via the Non-isocyanate Route with Catalytic Carbon Dioxide Fixation. Green Chem. 2013, 15, 934–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carré, C.; Zoccheddu, H.; Delalande, S.; Pichon, P.; Avérous, L. Synthesis and Characterization of Advanced Biobased Thermoplastic Nonisocyanate Polyurethanes, with Controlled Aromatic-Aliphatic Architectures. Eur. Polym. J. 2016, 84, 759–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tryznowski, M.; Świderska, A.; Zołek-Tryznowska, Z.; Gołofit, T.; Parzuchowski, P.G. Facile Route to Multigram Synthesis of Environmentally Friendly Non-isocyanate Polyurethanes. Polymer (Guildf) 2015, 80, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benyahya, S.; Habas, J.P.; Auvergne, R.; Lapinte, V.; Caillol, S. Structure–Property Relationships in Polyhydroxyurethanes Produced from Terephthaloyl Dicyclocarbonate with Various Polyamines. Polym. Int. 2012, 61, 1666–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Lee, D.S. Self-Healing and Rheological Properties of Polyhydroxyurethane Elastomers Based on Glycerol Carbonate Capped Prepolymers. Macromol. Res. 2019, 27, 460–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wazarkar, K.; Kathalewar, M.; Sabnis, A. Development of Epoxy-Urethane Hybrid Coatings via Non-isocyanate Route. Eur. Polym. J. 2016, 84, 812–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, L.; Tan, T.; Fong, H. Nonisocyanate Biobased Poly(ester urethanes) with Tunable properties synthesized via an environment-friendly route. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2016, 4–5, 2762–2770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tale, N.V.; Jagtap, R.N.; Tathe, D.S. An Efficient Approach for the Synthesis of Thermoset Polyurethane Acrylate Polymer and its Film Properties. Des. Monomers Polym. 2014, 17, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mamiński, M.Ł.; Szymański, R.; Parzuchowski, P.; Antczak, A.; Szymona, K. Hyperbranched Polyglycerols with Bisphenol A Core as Glycerol-derived Components of Polyurethane Wood Adhesives. BioResources 2012, 7, 1440–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Dolci, E.; Michaud, G.; Simon, F.; Boutevin, B.; Fouquay, S.; Caillol, S. Remendable Thermosetting Polymers for Isocyanate-free Adhesives: A Preliminary Study. Polym. Chem. 2015, 6, 7851–7861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitsch, E.K.; Heath, W.H.; Torkelson, J.M. Polyurethane/Polyhydroxyurethane Hybrid Polymers and their Applications as Adhesive Bonding Agents. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2016, 64, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, Y.H.; Lee, H.-J.; Han, C.J.; Lee, C.-R.; Kim, Y.; Kim, J.-W. Water-responsive Pressure-sensitive Adhesive with Reversibly Changeable Adhesion for Fabrication of Stretchable Devices. Mater. Des. 2020, 195, 108995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weil, E.D.; Levchik, S.V. Flame Retardants for Plastics and Textiles; Hanser Publishers: Munich, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Dufton, P.W. Flame Retardants for Plastics Market. Report; Rapra Technology Limited: West Midlands, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Benin, V.; Gardelle, B.; Morgan, A.B. Heat Release of Polyurethanes Containing Potential Flame Retardants Based on Boron and Phosphorus Chemistries. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2014, 106, 108–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benin, V.; Cui, X.; Morgan, A.B.; Seiwert, K.J. Synthesis and Flammability Testing of Epoxy Functionalized Phosphorous-based Flame Retardants. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2015, 132, 42296–42305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnenschein, M.F.; Virgili, J.M.; Babb, D.A.; Bell, B.M.; Nickless, B.C. Synthesis and Flame Retardant Potential of Polyols Based on Bisphenol-S. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 2016, 54, 2102–2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisele, A.; Kyriakos, K.; Bhandary, R.; Schönhoff, M.; Papadakis, C.M.; Rieger, B. Structure and Ionic Conductivity of Liquid Crystals having Propylene Carbonate Units. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 2942–2953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Einset, A.G.; Yang, C.-Y.; Chen, W.-X.; Wnek, G.E. Synthesis of Polysiloxanes Bearing Cyclic Carbonate Side Chains. Dielectric Properties and Ionic Conductivities of Lithium Triflate Complexes. Macromolecules 1994, 27, 4076–4079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.H.; Heo, G.; Pyo, K.; Kim, Y.; Kim, J.-W. Mechanically Robust and Healable Transparent Electrode Fabricated via Vapor-Assisted Solution Process. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 8129–8136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, W.; Wang, L.; Yang, Z.; Shen, J.-S.; Tang, F.; Zhang, J.; Cui, X. Facile Access to Versatile Aza-macrolides Through Iridium-Catalysed Cascade Allyl-amination/Macrolactonization. Chem. Commun. 2020, 56, 960–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mollaeian, K.; Wei, S.; Islam, M.R.; Dickerson, B.; Holmes, W.E.; Benson, T.J. Development of an Online Raman Analysis Technique for Monitoring the Production of Biofuels. Energy Fuels 2016, 30, 4112–4117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steber, J. Handbook for Cleaning/Decontamination of Surfaces: The Ecotoxicity of Cleaning Product Ingredients; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Castro, M.J.L.; Ojeda, C.; Cirelli, A.F. Advances in Surfactants for Agrochemicals. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2014, 12, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorella, G.; Strukul, G.; Scarso, A. Recent Advances in Catalysis in Micellar Media. Green Chem. 2015, 17, 644–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Climent, M.J.; Corma, A.; Iborra, S.; Martínez-Silvestre, S.; Velty, A. Preparation of Glycerol Carbonate Esters by using Hybrid Nafion-Silica Catalyst. ChemSusChem 2013, 6, 1224–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauritz, K.A.; Moore, R.B. State of Understanding of Nafion. Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 4535–4586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, L.; Wang, T. Preparation of Glycerol Monostearate from Glycerol Carbonate and Stearic Acid. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 34137–34145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campagne, B.; David, G.; Améduri, B.; Jones, D.J.; Rozière, J.; Roche, I. New Semi-IPN PEMFC Membranes Composed of Crosslinked Fluorinated Copolymer bearing Triazole Groups and sPEEK for Operation at Low Relative Humidity. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2015, 40, 16797–16813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

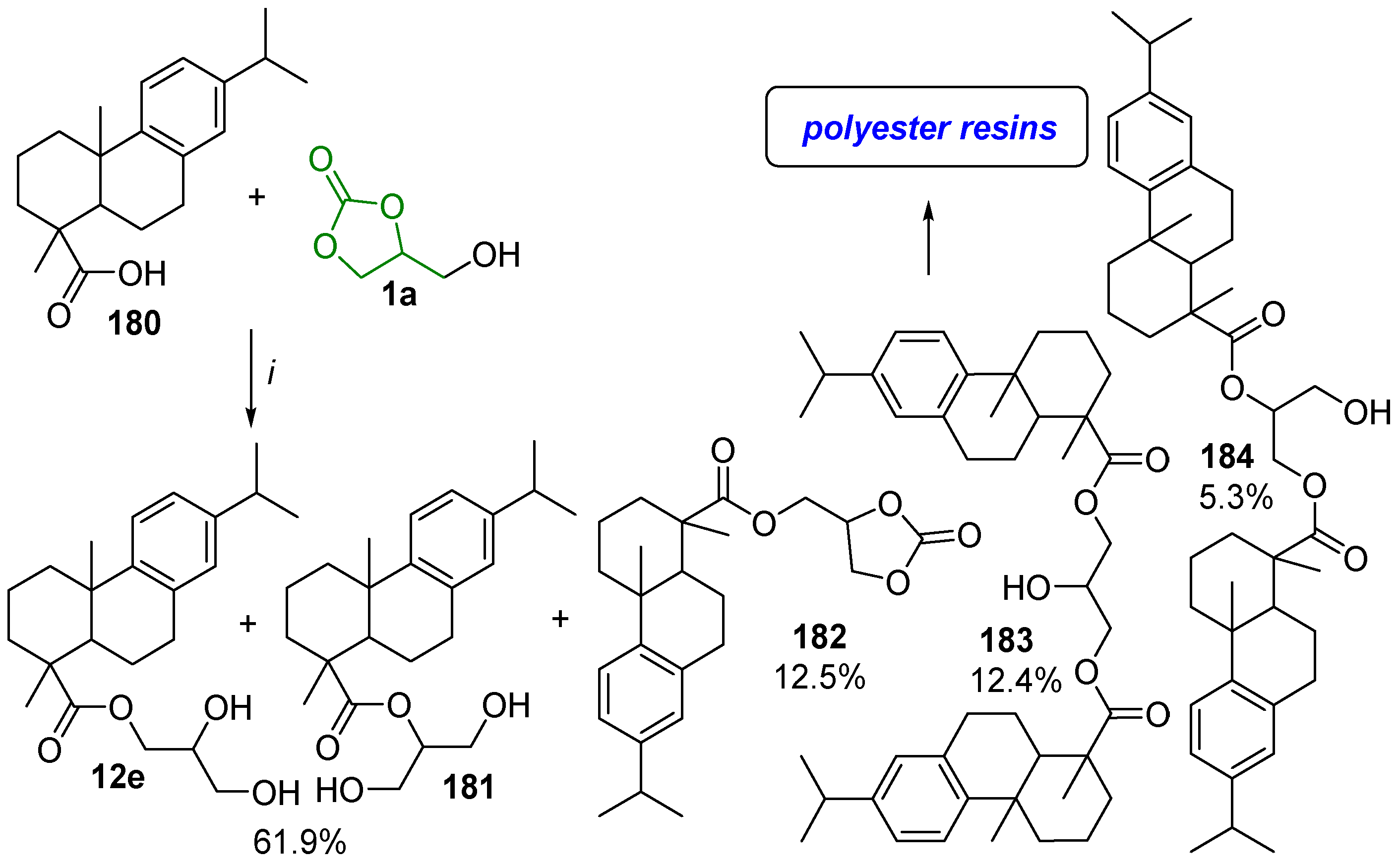

- Sacripante, G.G.; Zhou, K.; Farooque, M. Sustainable Polyester Resins Derived from Rosins. Macromolecules 2015, 48, 6876–6881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

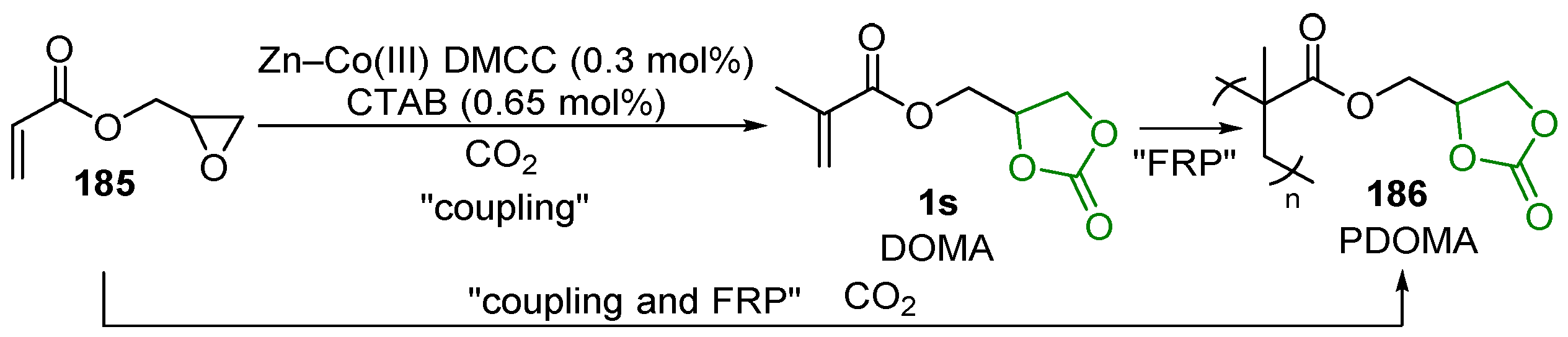

- Liu, B.; Zhang, Y.-Y.; Zhang, X.-H.; Du, B.-Y.; Fan, Z.-Q. Fixation of carbon dioxide concurrently or in tandem with free radical polymerization for highly transparent polyacrylates with specific UV absorption. Polym. Chem. 2016, 7, 3731–3739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

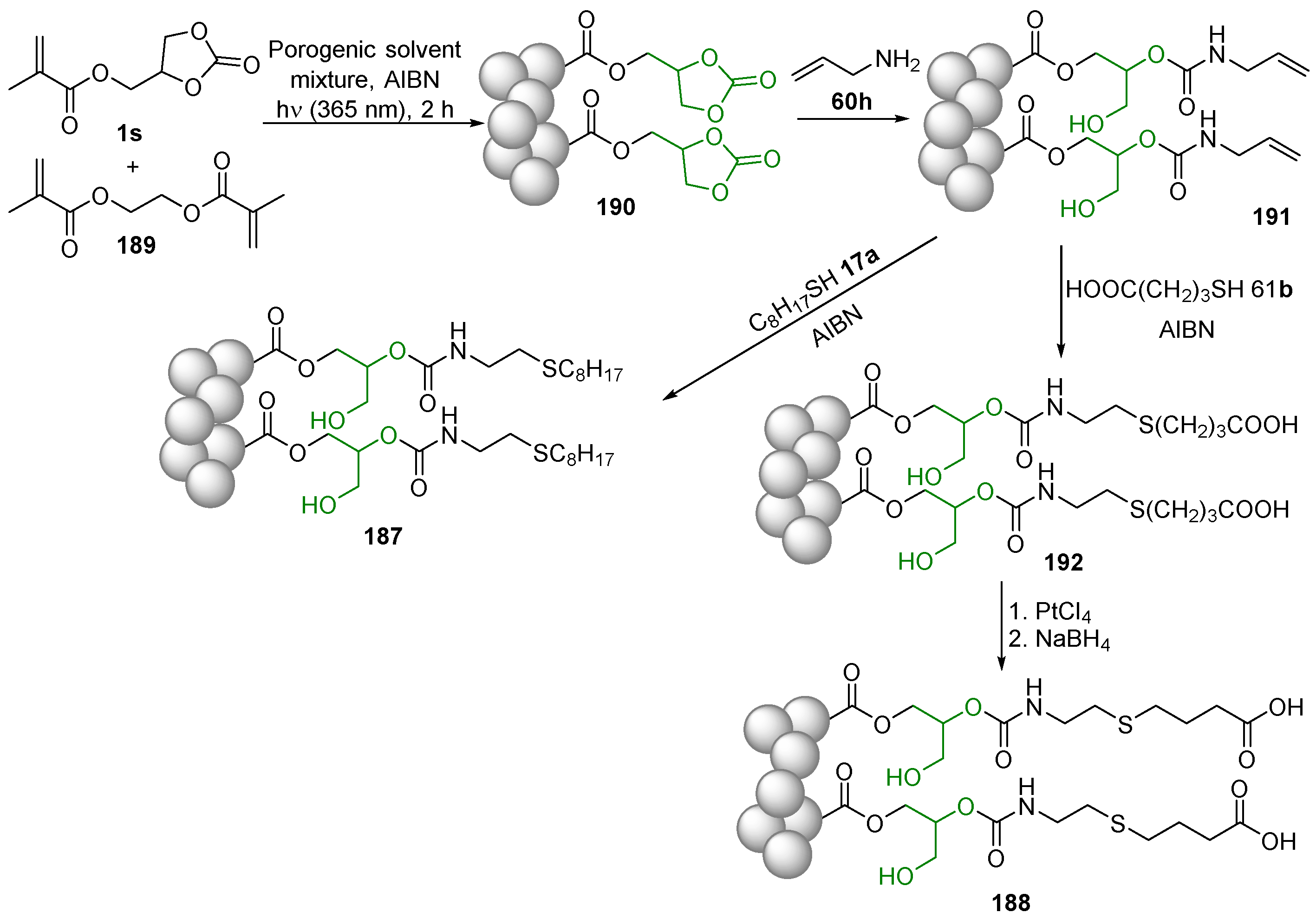

- Poupart, R.; Houda, D.N.E.; Chellapermal, D.; Guerrouache, M.; Carbonnier, B.; Droumaguet, B.L. Novel In-capillary Polymeric Monoliths Arising from Glycerol Carbonate Methacrylate for Flow-through Catalytic and Chromatographic Applications. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 13614–13617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

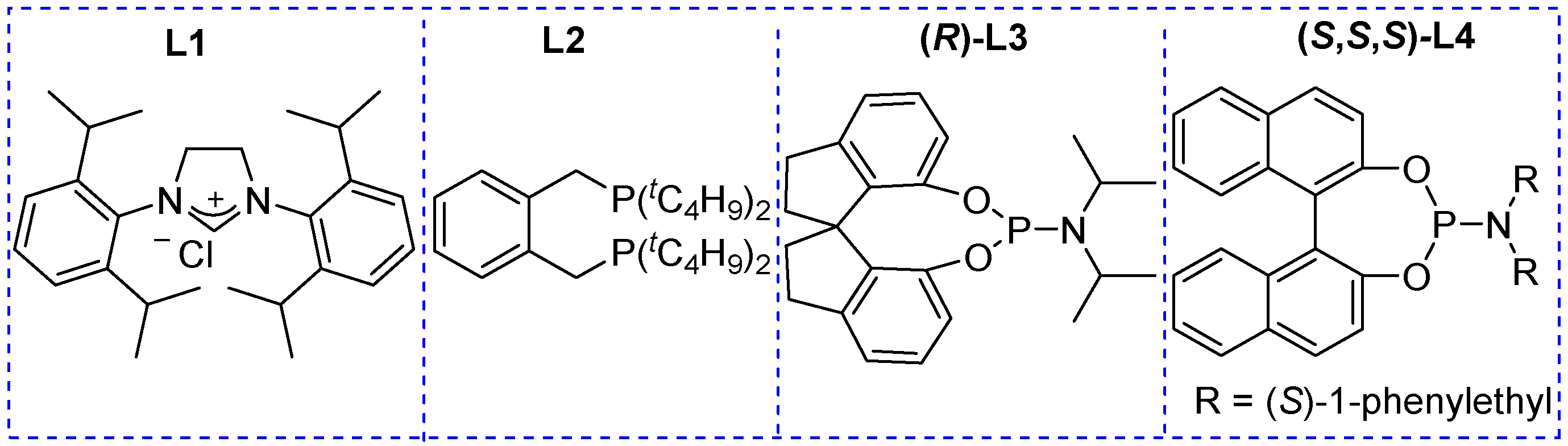

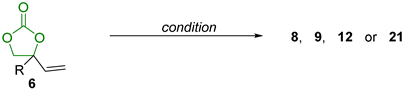

| ||||

| Entry | Condition | R | Product | Yield (%) |

| 1 | B2pin2 22 (1.2 equivalent) CuCl (9 mol%)/ L1 (13 mol%), Cs2CO3 (15 mol%), CH3OH, r.t., 16 h | aryl |  | 33–65 |

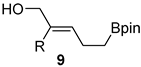

| 2 | Bpin(CH2)Bpin 23, (1.2 equivalent) CuCl (9 mol%), Cs2CO3 (50 mol%), CH3OH, r.t., 16 h | aryl, heteroaryl, vinyl |  | 48–82 |

| 3 | B2pin2 22 (1.2 equivalent) CuCl (9 mol%)/ L2 (13 mol%), Cs2CO3 (15 mol%), CH3OH, r.t., 16 h | alkyl, aryl, heteroaryl |  | 37–55 |

| 4 | Pd2(dba)3.CHCl3 (2.5 mol%) C6H5B(OH)2 24 (20 mol%), (R)-L3 (10 mol%), THF H2O (10 equivalent), 16 h, 40 °C | aryl, heteroaryl |  | 82–98% (80–98% ee) |

| 5 | Pd2(dba)3.CHCl3 (2.5 mol%) B(C2H5)3 25 (10 mol%), (S,S,S)-L4 (10 mol%), THF H2O (10 equivalent), 24 h, 20 °C | alkyl, benzyl, heteroalkyl |  | 61–87% (80–98% ee) |

| 6 | R1OH 7, Pd2(dba)3.CHCl3 (2.5 mol%), B(C2H5)3 25 (5 mol%), (R)-L3 (10 mol%), 40 °C toluene, 4Å MS, 16 h | R = alkyl, aryl, heteroaryl, heteroalkyl R1 = alkyl, benzyl, heteroalkyl, allyl |  | 56–97% (37–99% ee) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rollin, P.; Soares, L.K.; Barcellos, A.M.; Araujo, D.R.; Lenardão, E.J.; Jacob, R.G.; Perin, G. Five-Membered Cyclic Carbonates: Versatility for Applications in Organic Synthesis, Pharmaceutical, and Materials Sciences. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 5024. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11115024

Rollin P, Soares LK, Barcellos AM, Araujo DR, Lenardão EJ, Jacob RG, Perin G. Five-Membered Cyclic Carbonates: Versatility for Applications in Organic Synthesis, Pharmaceutical, and Materials Sciences. Applied Sciences. 2021; 11(11):5024. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11115024

Chicago/Turabian StyleRollin, Patrick, Liane K. Soares, Angelita M. Barcellos, Daniela R. Araujo, Eder J. Lenardão, Raquel G. Jacob, and Gelson Perin. 2021. "Five-Membered Cyclic Carbonates: Versatility for Applications in Organic Synthesis, Pharmaceutical, and Materials Sciences" Applied Sciences 11, no. 11: 5024. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11115024

APA StyleRollin, P., Soares, L. K., Barcellos, A. M., Araujo, D. R., Lenardão, E. J., Jacob, R. G., & Perin, G. (2021). Five-Membered Cyclic Carbonates: Versatility for Applications in Organic Synthesis, Pharmaceutical, and Materials Sciences. Applied Sciences, 11(11), 5024. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11115024