Reconstructing Human-Centered Interaction Networks of the Swifterbant Culture in the Dutch Wetlands: An Example from the ArchaeoEcology Project

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- What relationships between animal and plant species and their uses by humans can we identify in the archaeological record?

- How are these relationships organized?

- What does this tell us about the role of both wild and domesticated species in Swifterbant culture?

- What does this tell us about the changes in human–environmental interactions as a consequence of the Neolithic transition?

- Can these approaches demonstrate changing socio-economic priorities with the advent of domestication?

2. Archaeological Setting

2.1. The Neolithic Transition in the Dutch Wetlands

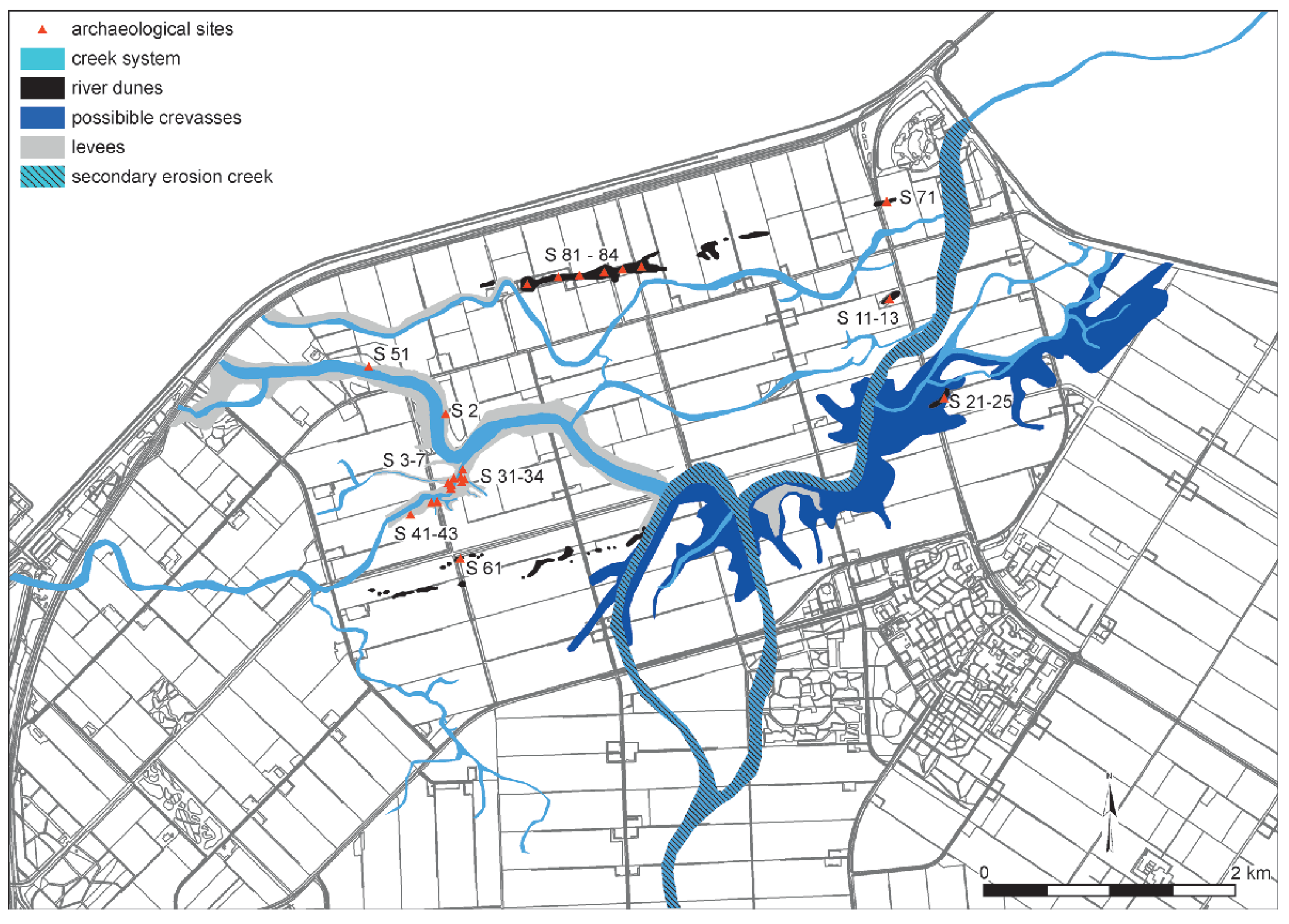

2.2. The Swifterbant Sites

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Network Analysis

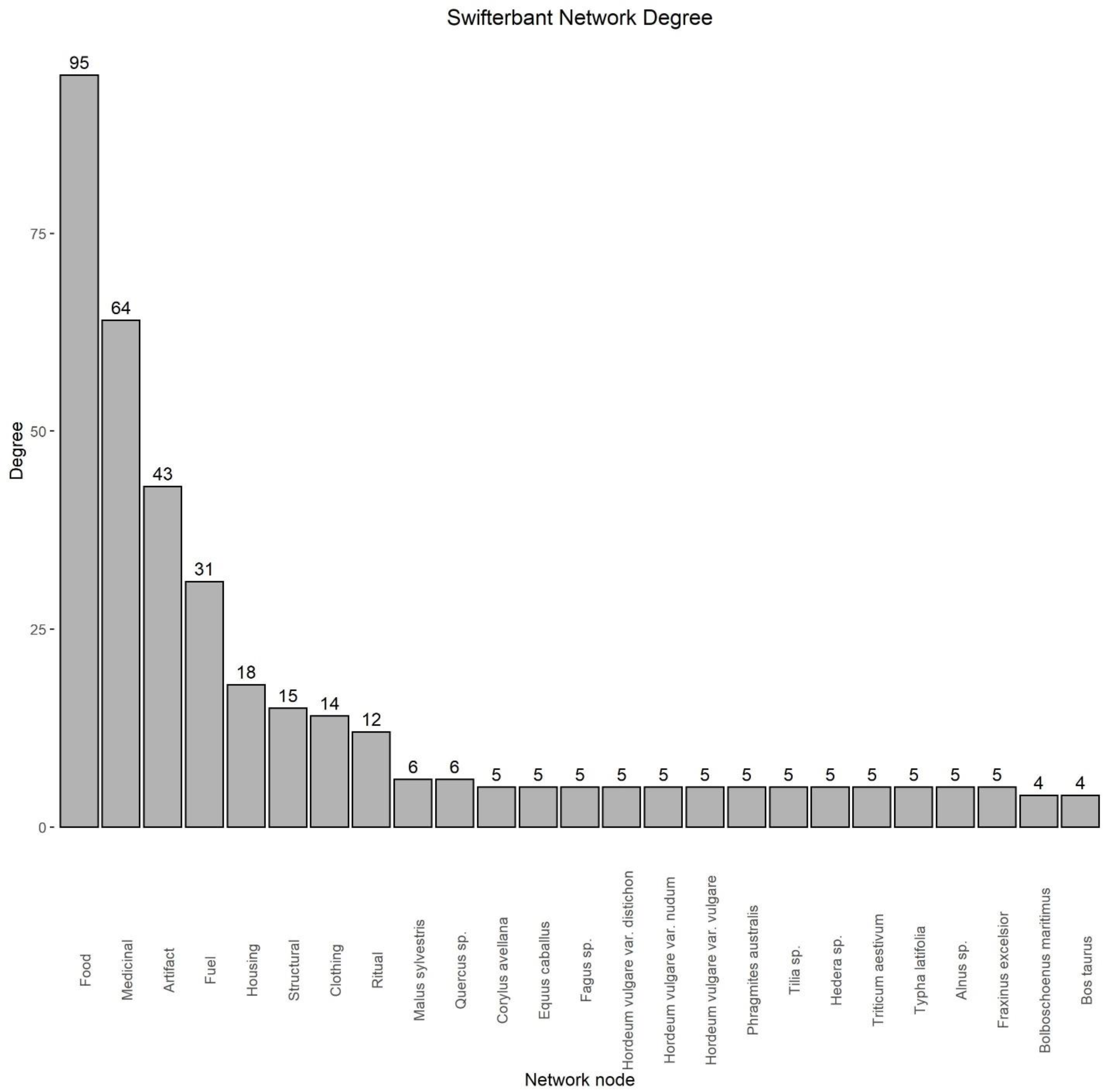

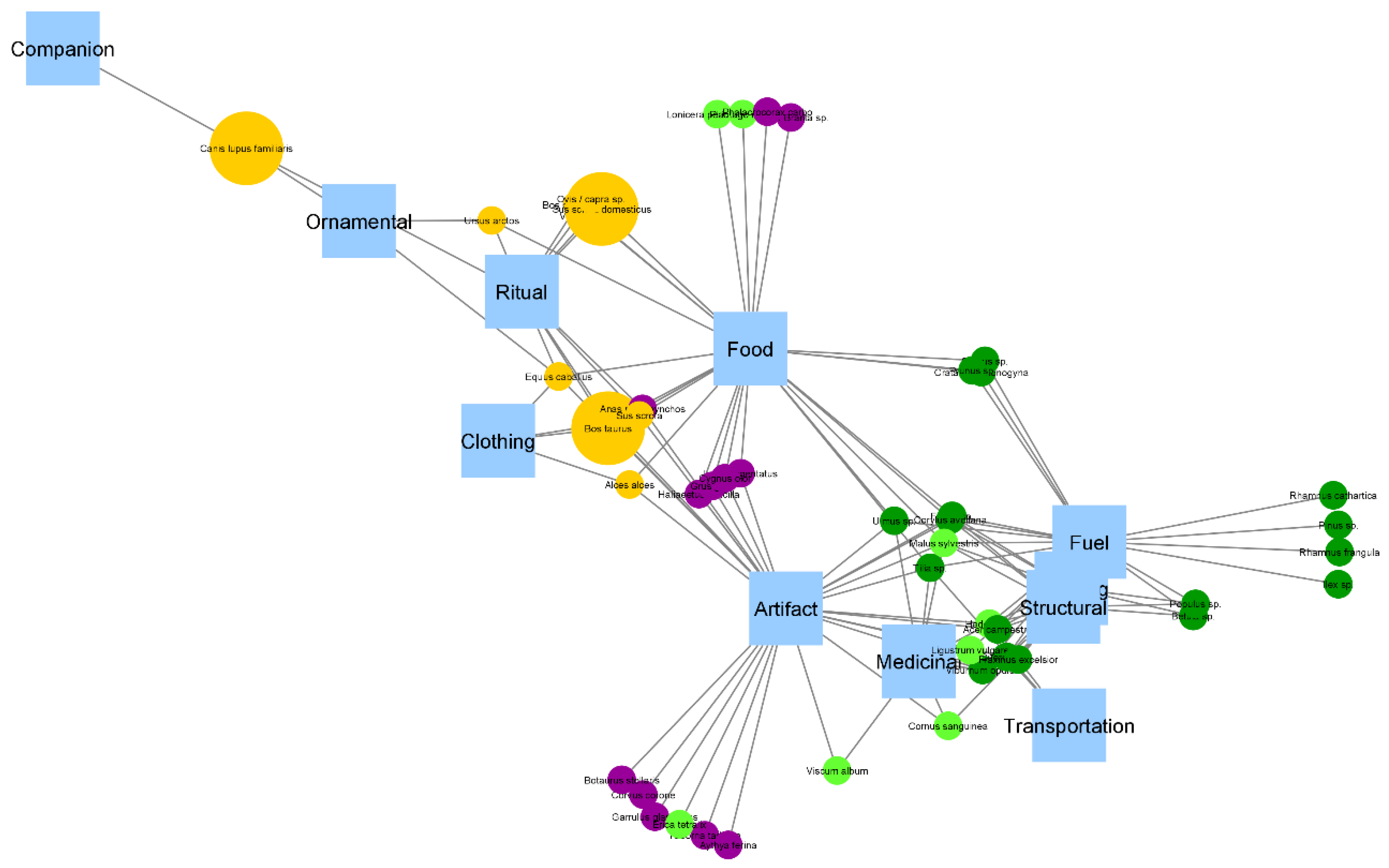

- Degree measures the number of direct connections between the nodes, so in this case, it shows the number of use categories per species and vice versa.

- Betweenness centrality is used to measure how essential a node is to the network. In order to ‘travel’ through the network, certain nodes will be passed more often than others. In contrast to social and geographical networks, where betweenness centrality is often used to identify the persons or places that are in control of (parts of) the network, in our case betweenness centrality can be seen as a measure of how crucial a species is for connecting use categories and vice versa.

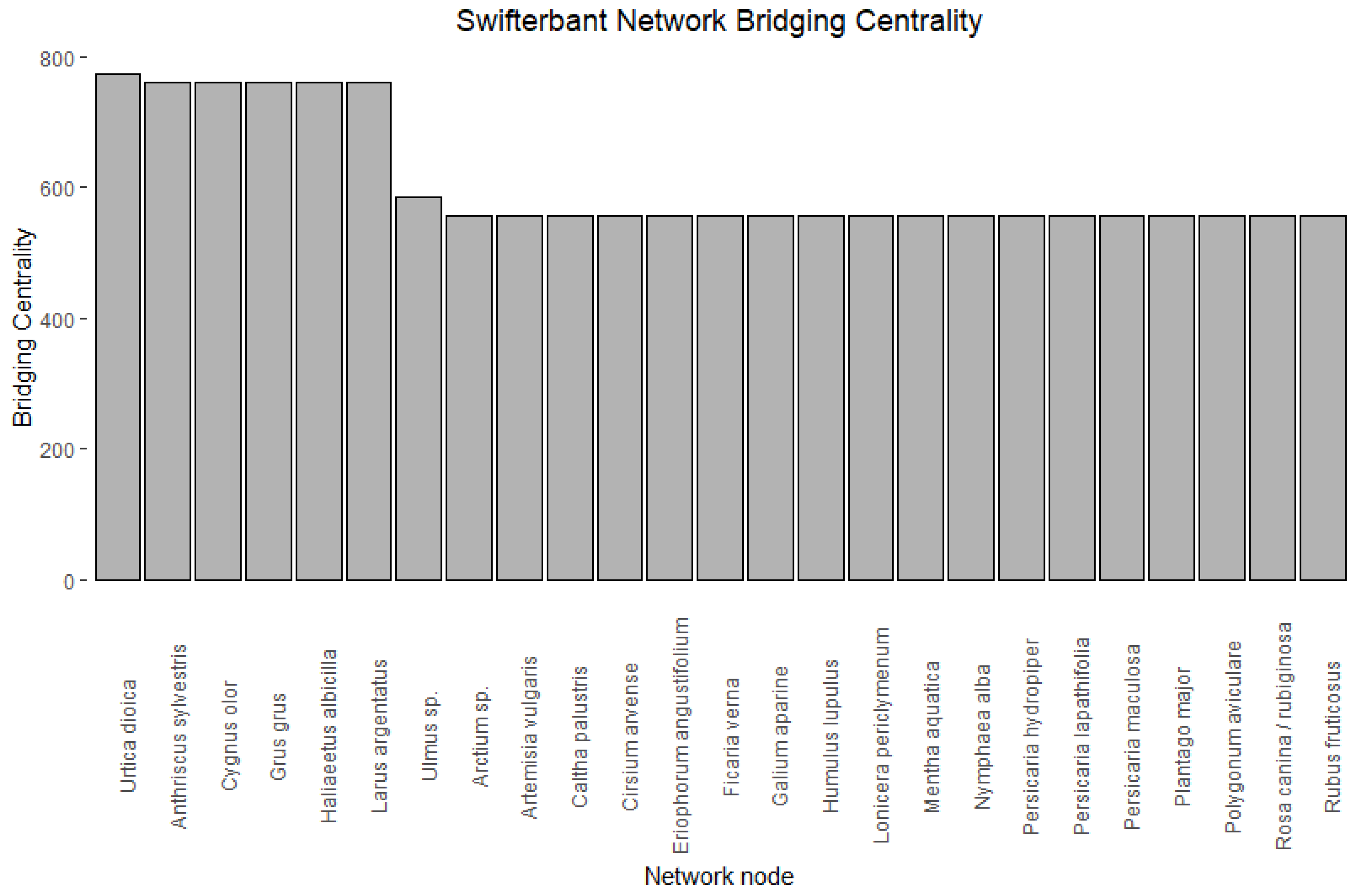

- Bridging centrality [46] combines degree and betweenness centrality: what nodes are highly connected, as well as crucial for connecting the network? Potentially, these are the nodes that connect different clusters in the network.

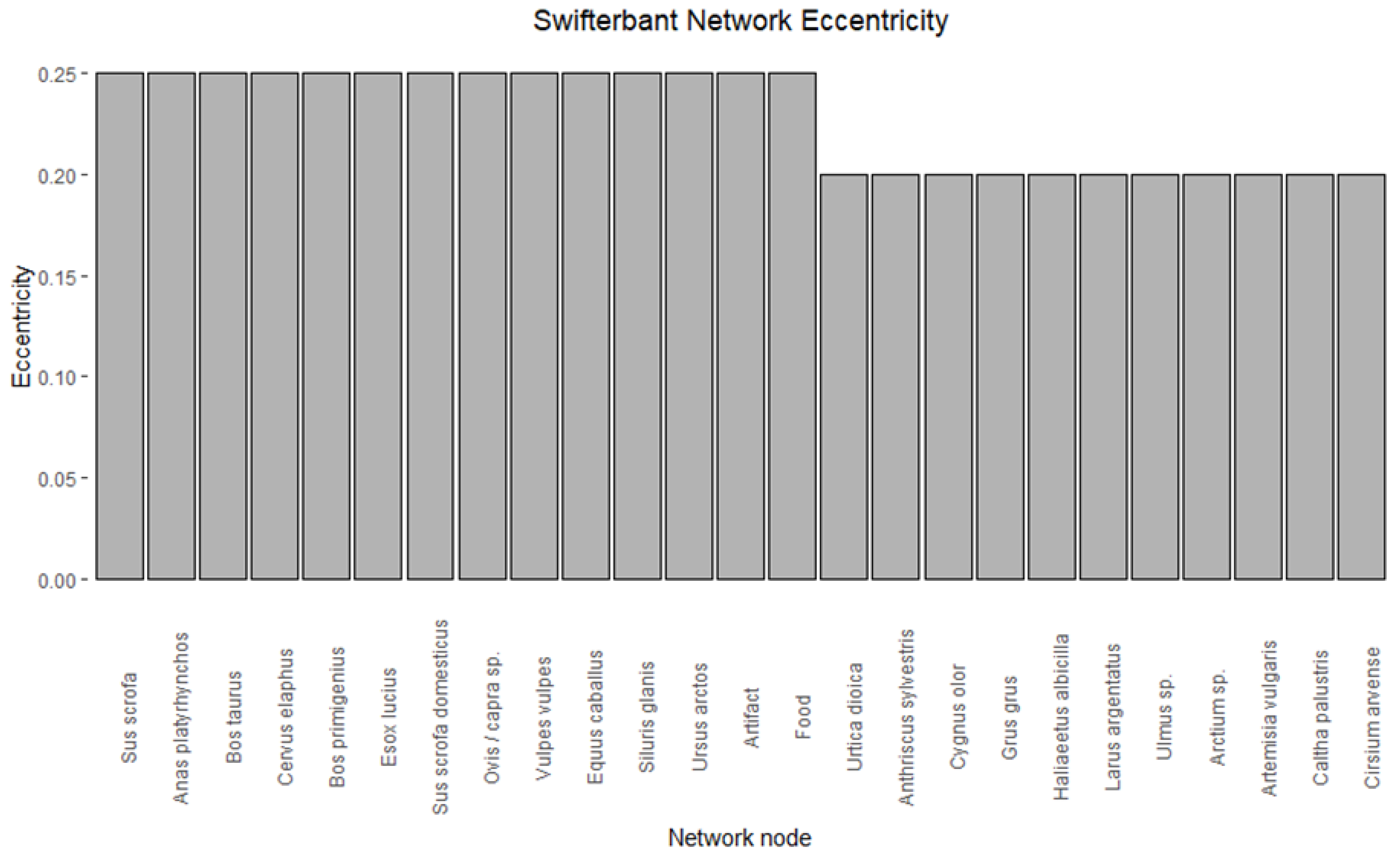

- Eccentricity will measure for each node the path distance to the node that is farthest away. A high eccentricity value for a node implies that the farthest node in the network is relatively near, so a node with a high eccentricity is one that is relatively central to the network. In our case, it can be used to understand what species are relatively well connected to different use categories.

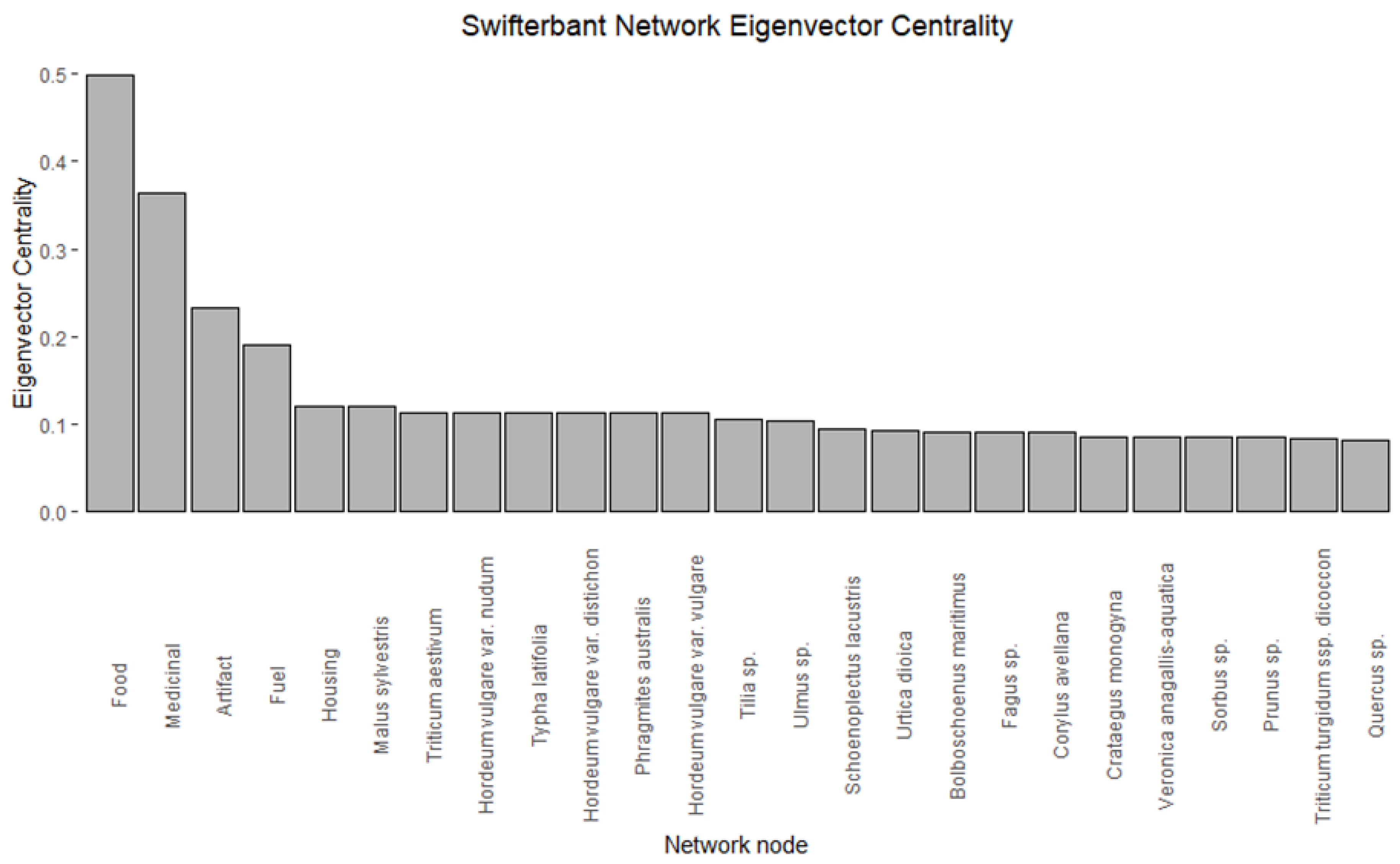

- Eigenvector centrality, finally, can be used to understand the hierarchy of the network by identifying the most influential nodes. Nodes with high eigenvector centrality have a large number of connections, but are also connected to other nodes to a high degree.

3. Results

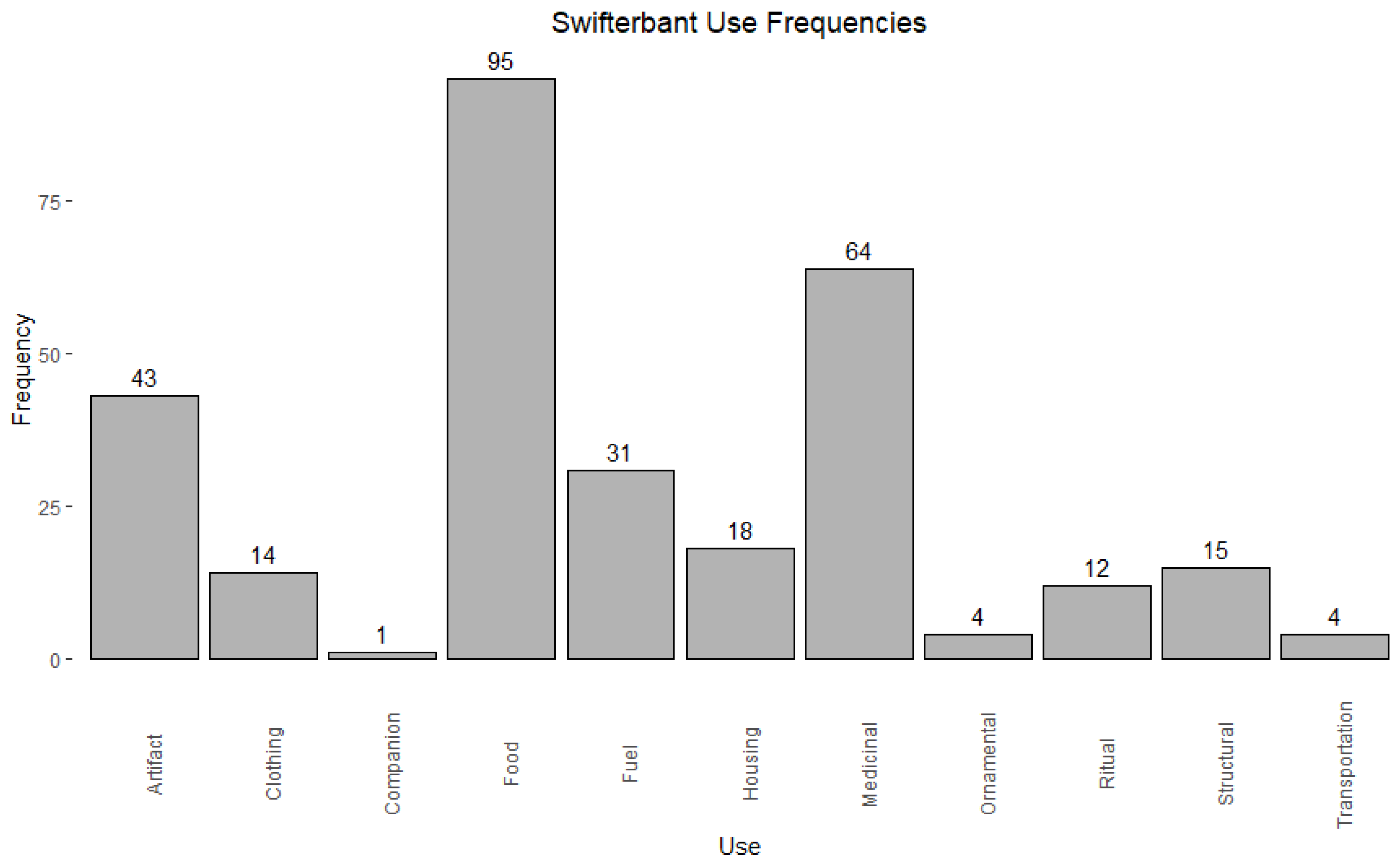

3.1. Degree

3.2. Betweenness Centrality

3.3. Bridging Centrality

3.4. Eccentricity

3.5. Eigenvector Centrality

4. Discussion

4.1. Network Structure

4.2. Cereals

4.3. Animal Husbandry

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Odling-Smee, J.; Erwin, D.H.; Palkovacs, E.P.; Feldman, M.W.; Laland, K.N. Niche Construction Theory: A Practical Guide for Ecologists. Q. Rev. Biol. 2013, 88, 3–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Crabtree, S.A.; Vaughn, L.J.; Crabtree, N.T. Reconstructing Ancestral Pueblo food webs in the southwestern United States. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2017, 81, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zvelebil, M. (Ed.) Hunters in Transition: Mesolithic Societies of Temperate Eurasia and Their Transition to Farming; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Bakels, C.C. The Western European Loess Belt. In The Western European Loess Belt; Springer Science and Business Media LLC: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bocquet-Appel, J.-P. Explaining the Neolithic Demographic Transition. In The Neolithic Demographic Transition and its Consequences; Bocquet-Appel, J.-P., Bar-Yosef, O., Eds.; Springer Science and Business Media LLC: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 35–55. [Google Scholar]

- Golitko, M.; Keeley, L.H. Beating ploughshares back into swords: Warfare in theLinearbandkeramik. Antiquity 2007, 81, 332–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittle, A.W.R.; Cummings, V. (Eds.) Going Over: The Mesolithic-Neolithic Transition in North-West Europe; Proceedings of the British Academy; The British Academy: Oxford, UK, 2007; Volume 144. [Google Scholar]

- Verhoeven, M. The Birth of a Concept and the Origins of the Neolithic: A History of Prehistoric Farmers in the Near East. Paléorient 2011, 37, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zvelebil, M. The agricultural transition and the origins of Neolithic society in Europe. Doc. Praehist. 2001, 28, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooijmans, L.P.L. The gradual transition to farming in the Lower Rhine Basin. In Going Over: The Mesolithic-Neolithic Transition in North-West Europe; Whittle, A.W.R., Cummings, V., Eds.; Proceedings of the British Academy; The British Academy: Oxford, UK, 2007; Volume 144, pp. 287–309. [Google Scholar]

- Marchand, G. Neolithic fragrances: Mesolithic-Neolithic interactions in western France. In Going Over: The Mesolithic-Neolithic Transition in North-West Europe; Proceedings of the British Academy: Oxford, UK, 2007; Volume 144, pp. 224–242. [Google Scholar]

- Dunne, J.A.; Maschner, H.; Betts, M.W.; Huntly, N.; Russell, R.; Williams, R.J.; Wood, S.A. The roles and impacts of human hunter-gatherers in North Pacific marine food webs. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 21179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crabtree, S.A.; Bird, D.W.; Bird, R.B. Subsistence Transitions and the Simplification of Ecological Networks in the Western Desert of Australia. Hum. Ecol. 2019, 47, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raemaekers, D.C.M. The Articulation of a ‘New Neolithic’. The Meaning of the Swifterbant Culture for the Process of Neolithisation in the Western Part of the North European Plain (4900-3400 BC); Archaeological Studies Leiden University; University of Leiden: Leiden, The Netherlands, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Oversteegen, J.H.S.; van Wijngaarden-Bakker, L.H.; Maliepaard, C.H.; van Kolfschoten, T. Zoogdieren, vogels en reptielen. In Hardinxveld-Giessendam De Bruin. Een kampplaats uit het Laat-Mesolithicum en het Begin van de Swifterbant-Cultuur (5500-4450 v. Chr.); Louwe-Kooijmans, L.P., Ed.; Rapportage Archeologische Monumentenzorg; Rijksdienst voor het Oudheidkundig Bodemonderzoek: Amersfoort, The Netherlands, 2001; pp. 209–298. [Google Scholar]

- Çakırlar, C.; Breider, R.; Koolstra, F.; Cohen, K.M.; Raemaekers, D.C.M. Dealing with domestic animals in the fifth millennium cal BC Dutch wetlands: New insights from old Swifterbant assemblages. In Farmers at the Frontier. A Pan European Perspective on Neolithisation; Gron, K.J., Sørensen, L., Rowley-Conwy, P., Eds.; Oxbow Books: Oxford, UK, 2020; pp. 263–287. [Google Scholar]

- Cappers, R.T.J.; Raemaekers, D.C.M. Cereal Cultivation at Swifterbant? Neolithic Wetland Farming on the North European Plain. Curr. Anthropol. 2008, 49, 385–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louwe-Kooijmans, L.P. Wetland Exploitation and Upland Relations of Prehistoric Communities in The Netherlands. In Flatlands and Wetlands: Current Themes in East Anglian Archaeology; Gardiner, J., Ed.; East Anglian Archaeology Report; Scole Archaeological Committee for East Anglia: Norwich, UK, 1993; pp. 71–116. [Google Scholar]

- Dusseldorp, G.L.; Amkreutz, L.W.S.W. A Long Slow Goodbye—Re-Examining the Mesolithic—Neolithic Transition (5500–2500 BCE) in the Dutch Delta. Analecta Praehist. Leiden. 2020, 50, 121–142. [Google Scholar]

- Kamjan, S.; Gillis, R.E.; Çakırlar, C.; Raemaekers, D.C.M. Specialized cattle farming in the Neolithic Rhine-Meuse Delta: Results from zooarchaeological and stable isotope (δ18O, δ13C, δ15N) analyses. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0240464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huisman, D.; Jongmans, A.; Raemaekers, D.C.M. Investigating Neolithic land use in Swifterbant (NL) using micromorphological techniques. Catena 2009, 78, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huisman, D.; Raemaekers, D. Systematic cultivation of the Swifterbant wetlands (The Netherlands). Evidence from Neolithic tillage marks (c. 4300–4000 cal. BC). J. Archaeol. Sci. 2014, 49, 572–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Out, W.A. Growing habits? Delayed introduction of crop cultivation at marginal Neolithic wetland sites. Veg. Hist. Archaeobotany 2008, 17, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Raemaekers, D.; de Roever, J.P. The Swifterbant pottery tradition (5000-3400 BC): Matters of fact and matters of interest. In Pots, Farmers and Foragers. Pottery Traditions and Social Interaction in the Earliest Neolithic of the Lower Rhine Area; Vanmontfort, B., Louwe Kooijmans, L.P., Amkreutz, L., Verhart, L.B.M., Eds.; ASLU; Leiden University Press: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 135–149. [Google Scholar]

- Raemaekers, D.C.M. Cutting a long story short? The process of neolithization in the Dutch delta re-examined. Antiquity 2003, 77, 740–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raemaekers, D.C.M. Taboo? The process of Neolitisation in the Dutch wetlands re-examined (5000–3400 cal BC). In Contacts, Boundaries & Innovation. Exploring Developed Neolithic Societies in Central Europe and Beyond; Gleser, R., Hofmann, D., Eds.; Sidestone Press: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 91–102. [Google Scholar]

- van der Waals, J.D.; Waterbolk, H.T. Excavations at Swifterbant—Discovery, Progress, Aims, and Methods (Swifterbant Contribution 1). Helinium 1976, 16, 4–14. [Google Scholar]

- Raemaekers, D.C.M.; Devriendt, I.; Cappers, R.T.J.; Prummel, W. Het Nieuwe Swifterbant Project. Nieuw Onderzoek Aan de Mesolithische En Neolithische Vindplaatsen Nabij Swifterbant (Provincie Flevoland, Nederland). Notae Praehistoricae 2005, 25, 119–127. [Google Scholar]

- Clason, A.T. Worked Bone, Antler and Teeth. A Preliminary Report (Swifterbant Contribution 9). Helinium 1978, 18, 83–86. [Google Scholar]

- Clason, A.T.; Brinkhuizen, D.C. Swifterbant, Mammals, Birds, Fishes. Preliminary Report (Swifterbant Contribution 8). Helinium 1978, 18, 69–82. [Google Scholar]

- Kranenburg, H.; Prummel, W. The use of domestic and wild animals. In Swifterbant S4 (the Netherlands): Occupation and Exploitation of a Neolithic Levee Site (c. 4300-4000 cal. BC); Raemaekers, D.C.M., de Roever, J.P., Eds.; Groningen Archaeological Studies; Barkhuis Publishing: Eelde, The Netherlands, 2020; Volume 36, pp. 76–94. [Google Scholar]

- Casparie, W.A.; Mook-Kamps, B.; Palfenier-Vegter, R.M.; Struijk, P.C.; van Zeist, W. The Paleobotany of Swifterbant (Swifterbant Contribution 7). Helinium 1977, 17, 28–55. [Google Scholar]

- Van Zeist, W.; Palfenier-Vegter, R. Seeds and Fruits from the Swifterbant S3 Site. Final Rep. Swifterbant IV Palaeohistoria 1981, 23, 105–168. [Google Scholar]

- Schepers, M. Wet, Wealthy Worlds: The Environment of the Swifterbant River System during the Neolithic Occupation (4300–4000 Cal BC). J. Archaeol. Low Ctries. 2014, 5, 79–106. [Google Scholar]

- Schepers, M.; Bottema-Mac, G.N. The vegetation and exploitation of plant resources. In Swifterbant S4 (The Netherlands): Occupation and Exploitation of a Neolithic Levee Site (c. 4300–4000 cal. BC); Raemaekers, D.C.M., de Roever, J.P., Eds.; Groningen Archaeological Studies; Barkhuis Publishing: Eelde, The Netherlands, 2020; Volume 36, pp. 51–75. [Google Scholar]

- Devriendt, I. Swifterbant Stones: The Neolithic Stone and Flint Industry at Swifterbant (the Netherlands): From Stone Typology and Flint Technology to Site Function; Groningen Archaeological Studies; Barkhuis/Groningen University Library: Groningen, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Raemaekers, D.; Smits, L.; Molthof, H.M. The Textbook “dealing with Death” from the Neolithic Swifterbant Culture (5000–3400 BC), The Netherlands. Ber. Römisch-Ger. Komm. 2009, 88, 479–500. [Google Scholar]

- Raemaekers, D.C.M.; Geuverink, J.; Woltinge, I.; van der Laan, J.; Maurer, A.; Scheele, E.E.; Sibma, T.; Huisman, D.J. Swifterbant-S25 (Gemeente Dronten, Provincie Flevoland). Een Bijzondere Vindplaats van de Swifterbant-Cultuur (ca. 4500-3700 Cal. BC). Palaeohistoria 2014, 56, 1–56. [Google Scholar]

- Ente, P.J. The Geology of the Northern Part of Flevoland in Relation to the Human Occupation in the Atlantic Time. Helinium 1976, 16, 15–35. [Google Scholar]

- Price, T.D. Swifterbant, Oost Flevoland, Netherlands: Excavations at the River Dune Sites, S21–S24, 1976: Final Reports on Swifterbant III. Palaeohistoria 1981, 75–104. [Google Scholar]

- Dormann, C.F.; Gruber, B.; Fründ, J. Introducing the Bipartite Package: Analysing Ecological Networks. Interaction 2008, 8, 8–11. [Google Scholar]

- Dormann, C.F.; Frund, J.; Bluthgen, N.; Gruber, B. Indices, Graphs and Null Models: Analyzing Bipartite Ecological Networks. Open Ecol. J. 2009, 2, 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dormann, C.F.; Strauss, R. A method for detecting modules in quantitative bipartite networks. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2013, 5, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bennett, A.E.; Evans, D.M.; Powell, J.R. Potentials and pitfalls in the analysis of bipartite networks to understand plant–microbe interactions in changing environments. Funct. Ecol. 2019, 33, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scardoni, G.; Petterlini, M.; Laudanna, C. Analyzing biological network parameters with CentiScaPe. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 2857–2859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Baruah, A.K.; Bora, T. Bridging Centrality: Identifying Bridging Nodes in Transportation Network. IJANA 2018, 9, 3669–3673. [Google Scholar]

- Borgatti, S.P.; Everett, M.G. Network analysis of 2-mode data. Soc. Netw. 1997, 19, 243–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latapy, M.; Magnien, C.; del Vecchio, N. Basic notions for the analysis of large two-mode networks. Soc. Netw. 2008, 30, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opsahl, T. Triadic closure in two-mode networks: Redefining the global and local clustering coefficients. Soc. Netw. 2013, 35, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Taheri, S.M.; Mahyar, H.; Firouzi, M.; Ghalebi, E.; Grosu, R.; Movaghar, A. HellRank: A Hellinger-based centrality measure for bipartite social networks. Soc. Netw. Anal. Min. 2017, 7, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Opsahl, T.; Panzarasa, P. Clustering in weighted networks. Soc. Netw. 2009, 31, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, M.E.J. Scientific collaboration networks. II. Shortest paths, weighted networks, and centrality. Phys. Rev. E 2001, 64, 016132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zeiler, J.T. Hunting, Fowling and Stock-Breeding at Neolithic Sites in the Western and Central Netherlands; University of Groningen: Groningen, The Netherlands, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Smits, L.; van der Plicht, H. Mesolithic and Neolithic Human Remains in the Netherlands: Physical Anthropological and Stable Isotope Investigations. J. Archaeol. Low Ctries. 2009, 1, 55–85. [Google Scholar]

- Smits, E.; Millard, A.R.; Nowell, G.; Pearson, D.G. Isotopic Investigation of Diet and Residential Mobility in the Neolithic of the Lower Rhine Basin. Eur. J. Archaeol. 2010, 13, 5–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Devriendt, I. “Diamonds are a girl’s best friend”. Neolithische kralen en hangers uit Swifterbant. Westerheem 2008, 57, 384–397. [Google Scholar]

- Prummel, W.; Sanden, W.A.B. Runderhoorns Uit de Drentse Venen. Drentse Volksalm. 1995, 112, 8–55. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Dor, M.; Sirtoli, R.; Barkai, R. The evolution of the human trophic level during the Pleistocene. Am. J. Phys. Anthr. 2021, 24247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brinkhuizen, D.C. Preliminary Notes on Fish Remains from Archaeological Sites in the Netherlands. Palaeohistoria 1979, 21, 83–90. [Google Scholar]

- Huisman, D.; Ngantillard, D.; Tensen, M.; Laarman, F.; Raemaekers, D. A question of scales: Studying Neolithic subsistence using micro CT scanning of midden deposits. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2014, 49, 585–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Out, W.A. Integrated archaeobotanical analysis: Human impact at the Dutch Neolithic wetland site the Hazendonk. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2010, 37, 1521–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schepers, M.; Cappers, R.T.J.; Bekker, R.M. A review of prehistoric and early historic mainland salt marsh vegetation in the northern-Netherlands based on the analysis of plant macrofossils. J. Coast. Conserv. 2013, 17, 755–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schepers, M. Reconstructing Vegetation Diversity in Coastal Landscapes; Barkhuis: Eelde, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Out, W.A. Selective use of Cornus sanguinea L. (red dogwood) for Neolithic fish traps in the Netherlands. Environ. Archaeol. 2008, 13, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooijmans, L.P.L. Peddelen over de plassen. In Boomstamkano’s, Overnaadse Schepen en Tuigage. Inleidingen Gehouden Tijdens Het Tiende Glavimans Symposion Lelystad, 20 April 2006; Oosting, R., van den Akker, J., Eds.; Glavimans Stichting: Amersfoort, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 26–37. [Google Scholar]

- Serjeantson, D. Review of Animal Remains from the Neolithic and Bronze Age of Southern Britain (4000BC–1500BC). Environmental Studies Report; Research Department Report Series; English Heritage: Fort Cumberland, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kubiak-Martens, L. Botany: Local vegetation and plant use. In A Kaleidoscope of Gathering at Keinsmerbrug (The Netherlands). Late Neolithic Behavioural Variability in a Dynamic Landscape; Smit, B.I., Brinkkemper, O., Kleijne, J.P., Lauwerier, R.C.G.M., Theunissen, E.M., Eds.; Nederlandse Archeologische Rapporten; Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands: Amersfoort, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 81–100. [Google Scholar]

- Bakels, C. Neolithic Plant Remains from the Hazendonk, Province of Zuid-Holland, the Netherlands. Z. Archäologie 1981, 15, 141–148. [Google Scholar]

| Class | Number of Species |

|---|---|

| bird | 13 |

| fish | 15 |

| fungus | 2 |

| mammal | 20 |

| moss | 18 |

| plant | 99 |

| tree | 19 |

| total | 186 |

| Category | Explanation |

|---|---|

| artifact | anything used to make portable artifacts such as tools, bowls, utensils |

| clothing | includes personal adornment such as garlands and perfume |

| companion | commensal animals and pets such as dogs |

| food | anything ingested for nutrition, including spices |

| fuel | anything used for heat, cooking, illumination |

| housing | anything used for timber, thatch, mats, posts, etc. |

| medicinal | anything ingested or applied for health reasons |

| ornamental | any taxa used for secular aesthetic reasons beyond personal adornment |

| ritual | includes tribute and religious use, monuments, shrines |

| structural | for constructing structures aside from houses |

| trade | anything used as a trade/exchange good, or that was traded/exchanged in from elsewhere |

| transportation | anything used to move across the land/sea such as boats, horses, etc. |

| Category | Count | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| artifact | 43 | 14.3% |

| clothing | 14 | 4.7% |

| companion | 1 | 0.3% |

| food | 95 | 31.6% |

| fuel | 31 | 10.3% |

| housing | 18 | 6.0% |

| medicinal | 64 | 21.3% |

| ornamental | 4 | 1.3% |

| ritual | 12 | 4.0% |

| structural | 15 | 5.0% |

| trade | 0 | 0.0% |

| transportation | 4 | 1.3% |

| total | 301 | 100.0% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Verhagen, P.; Crabtree, S.A.; Peeters, H.; Raemaekers, D. Reconstructing Human-Centered Interaction Networks of the Swifterbant Culture in the Dutch Wetlands: An Example from the ArchaeoEcology Project. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 4860. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11114860

Verhagen P, Crabtree SA, Peeters H, Raemaekers D. Reconstructing Human-Centered Interaction Networks of the Swifterbant Culture in the Dutch Wetlands: An Example from the ArchaeoEcology Project. Applied Sciences. 2021; 11(11):4860. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11114860

Chicago/Turabian StyleVerhagen, Philip, Stefani A. Crabtree, Hans Peeters, and Daan Raemaekers. 2021. "Reconstructing Human-Centered Interaction Networks of the Swifterbant Culture in the Dutch Wetlands: An Example from the ArchaeoEcology Project" Applied Sciences 11, no. 11: 4860. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11114860

APA StyleVerhagen, P., Crabtree, S. A., Peeters, H., & Raemaekers, D. (2021). Reconstructing Human-Centered Interaction Networks of the Swifterbant Culture in the Dutch Wetlands: An Example from the ArchaeoEcology Project. Applied Sciences, 11(11), 4860. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11114860