Potential for Farmers’ Cooperatives to Convert Coffee Husks into Biochar and Promote the Bioeconomy in the North Ecuadorian Amazon

Abstract

Featured Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

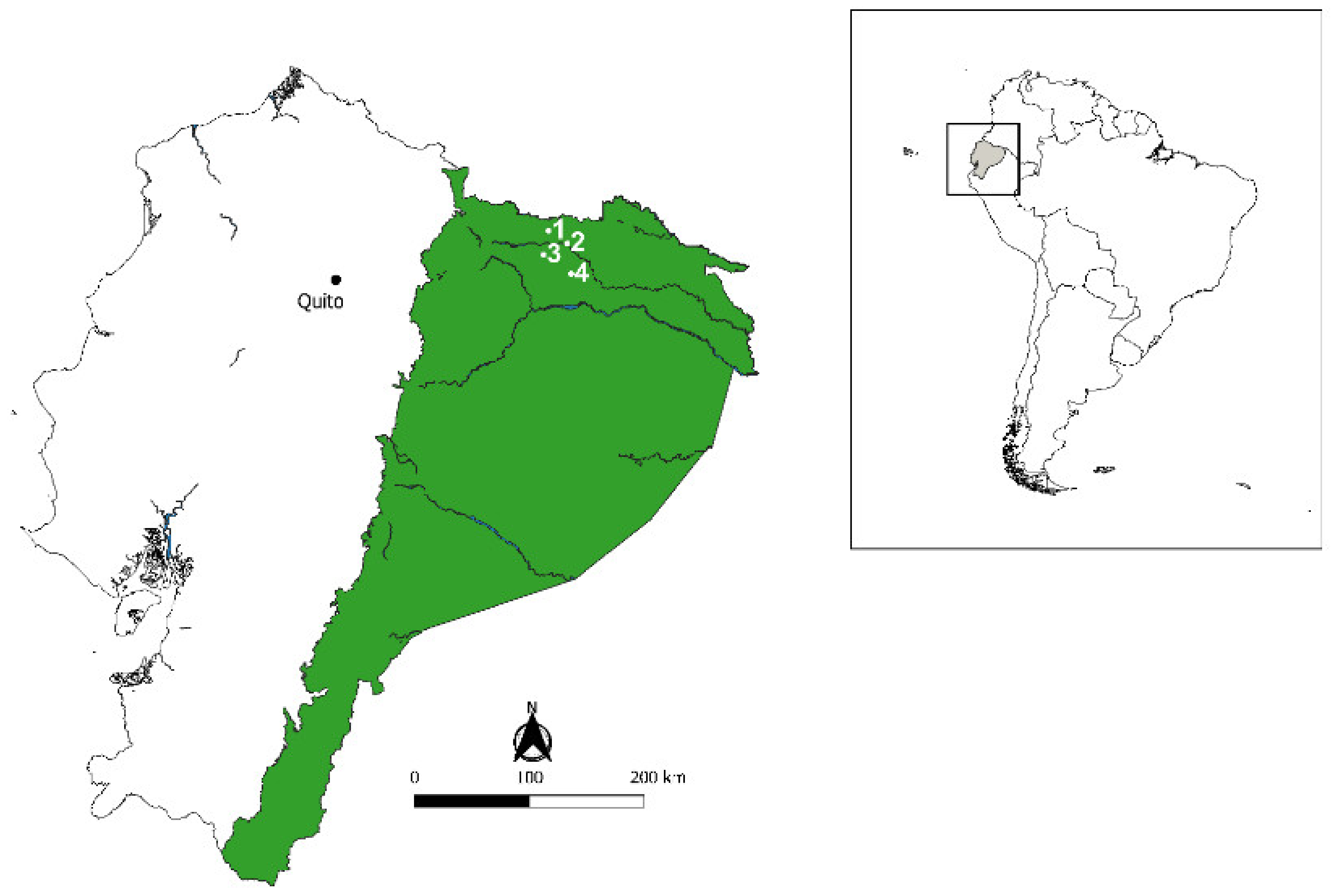

2.1. Study Region

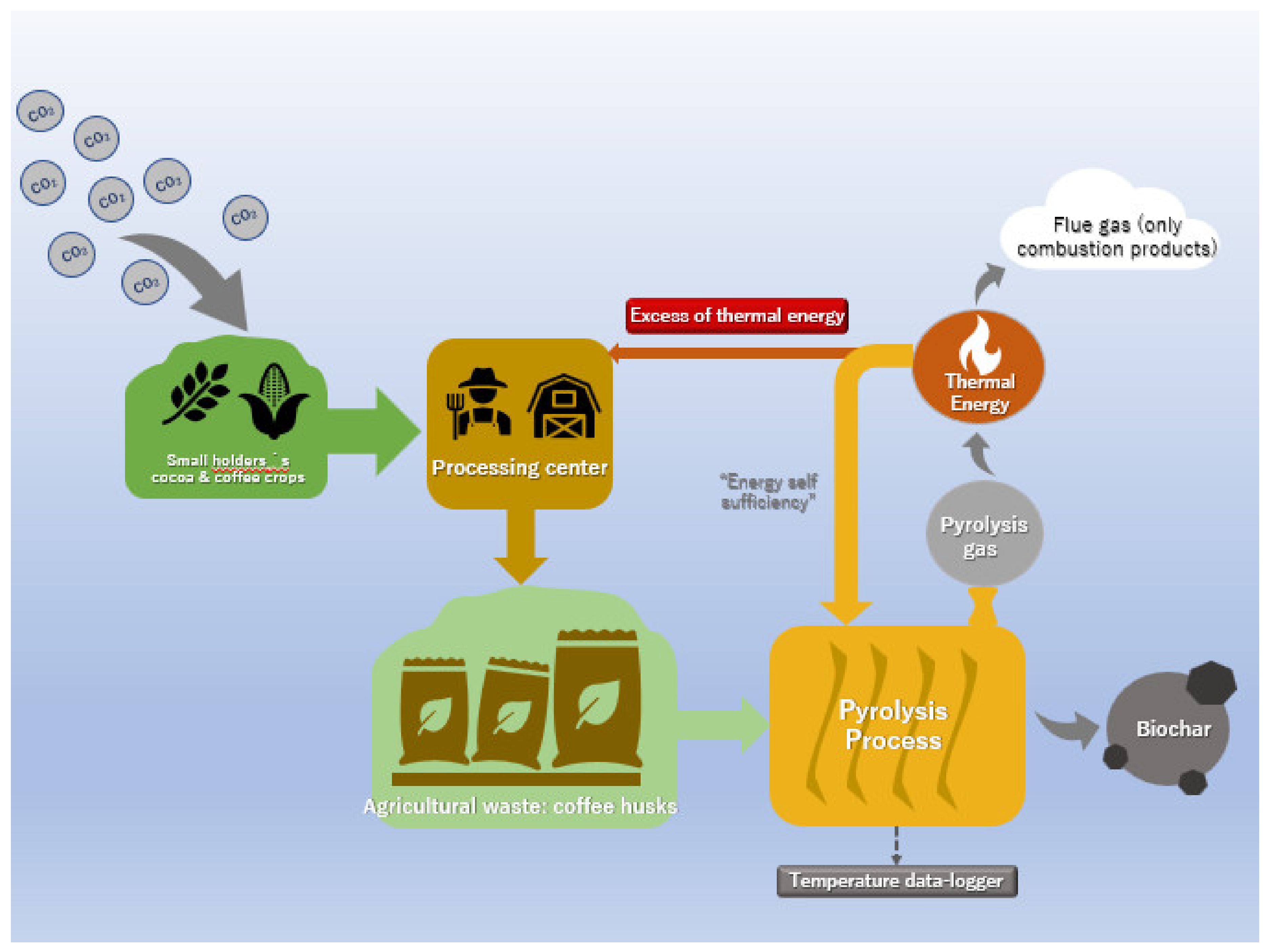

2.2. Criteria and Outline Conditions to Analyze the Adaptability of Pyrolysis Technology within the Farmers’ Cooperatives

2.3. Policy Analysis: Existing Laws Governing the Energy Conversion of Agricultural Waste in Farmers’ Cooperatives of Ecuador

2.4. Biochar Applications of Relevance for the NEA: Criteria for Classification

2.5. The SWOT Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

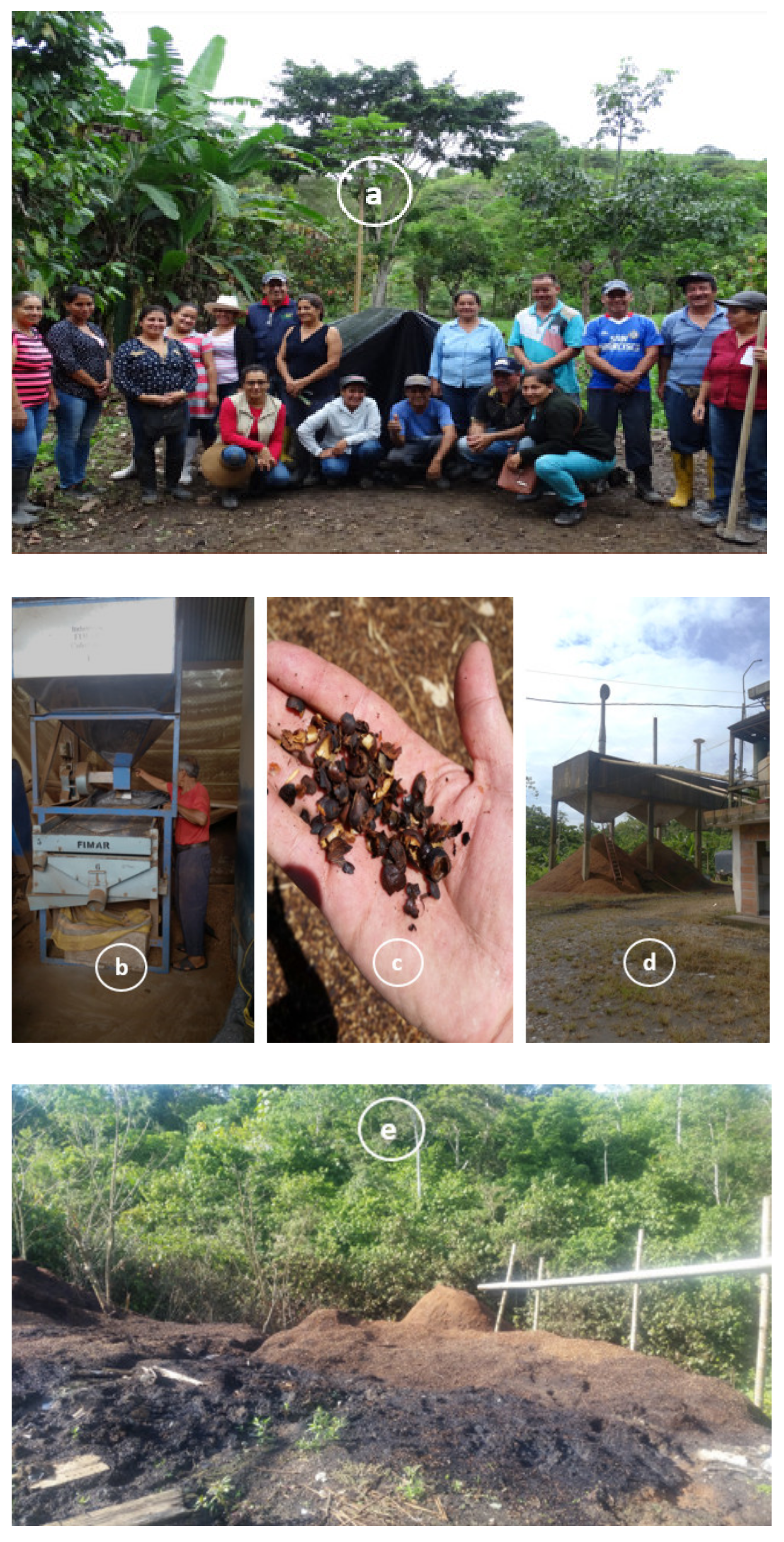

3.1. Agricultural Waste Generated in the Post-Harvest Facilities of the NEA: The Status Quo.

3.2. Policies and Standards Linked with the Energetic Use of Agricultural Waste in Ecuador

3.3. Technological Alternatives for the Conversion of Agricultural Waste into Biochar in the Studied Farmers’ Cooperatives

3.4. Potential Applications of Biochar in the NEA

3.5. SWOT Analysis: Challenges and Opportunities Associated with the Integration of Pyrolysis Facilities in Farmers’ Cooperatives of the NEA

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Merloti, L.F.; Mendes, L.W.; Pedrinho, A.; de Souza, L.F.; Ferrari, B.M.; Tsai, S.M. Forest-to-agriculture conversion in Amazon drives soil microbial communities and N-cycle. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2019, 137, 107567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viteri, O. Evaluación de la Sostenibilidad de los Cultivos de Café y Cacao en las Provincias de Orellana y Sucumbíos. Ph.D. Thesis, Universitat Autónoma de Barcelona, Bellaterra, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Handelman, H. Ecuadorian Agrarian Reform: The Politics of Limited Change. Polit. Agrar. Chang. Asia Lat. Am. 1980, 49, 63–81. [Google Scholar]

- Salazar, O.V.; Ramos-Martín, J. Organizational structure and commercialization of coffee and cocoa in the northern Amazon region of Ecuador. Rev. NERA 2017, 35, 266–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viteri, O.; Ramos-martín, J.; Lomas, P.L. Livelihood sustainability assessment of coffee and cocoa producers in the Amazon region of Ecuador using household types. J. Rural Stud. 2018, 62, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasco, C.; Torres, B.; Pacheco, P.; Griess, V. The socioeconomic determinants of legal and illegal smallholder logging: Evidence from the Ecuadorian Amazon. For. Policy Econ. 2017, 78, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldekop, J.A.; Holmes, G.; Harris, W.E.; Evans, K.L. A global assessment of the social and conservation outcomes of protected areas. Conserv. Biol. 2016, 30, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A.; Redford, K. Conservation and displacement: An overview. Conserv. Soc. 2009, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, R.; Brockington, D. Forests: Time series to guide restoration. Nature 2019, 569, 630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chazdon, R.L. Protecting intact forests requires holistic approaches. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2018, 2, 915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medina, J.D.C.; Magalhães, A.I.; Zamora, H.D.; Melo, J.D.Q. Oil palm cultivation and production in South America: Status and perspectives. Biofuels Bioprod. Biorefining 2019, 13, 1202–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INEC Población y Demografía. Available online: https://www.ecuadorencifras.gob.ec/censo-de-poblacion-y-vivienda/ (accessed on 3 April 2020).

- Erbaugh, J.T.; Pradhan, N.; Adams, J.; Oldekop, J.A.; Agrawal, A.; Brockington, D.; Pritchard, R.; Chhatre, A. Global forest restoration and the importance of prioritizing local communities. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presidencia de la República. Reglamento a La Ley Orgánica de la Economía Popular y Solidaria; Superintendencia de Economía Popular y Solidaria: Ecuador, Quito, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bajo, C.S. Research on cooperatives in Latina America, an overview of the state of the art and contributions. Rev. Int. Co-operation 2017, 104, 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Cheney, G.; Santa Cruz, I.; Peredo, A.M.; Nazareno, E. Worker cooperatives as an organizational alternative: Challenges, achievements and promise in business governance and ownership. Organization 2014, 21, 591–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heras-Saizarbitoria, I.; Basterretxea, I. Do co-ops speak the managerial lingua franca? An analysis of the managerial discourse of Mondragon cooperatives. J. Co-op. Organ. Manag. 2016, 4, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, P.; Martínez, L. Local alternatives to private agricultural certification in Ecuador: Broadening access to “new markets”? J. Rural Stud. 2016, 45, 292–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Superintendencia de Economía Popular y Solidaria Actualidad y cifras EPS Diciembre 2019. Available online: https://www.seps.gob.ec/documents/20181/888238/Plan_Estratégico_2019-2022.pdf/25fe5f5f-5424-4a79-a235-115c7902d8f5?version=1.0 (accessed on 22 January 2020).

- UNDP Integrated Management of Multiple-Use Landscapes and High-Value Conservation Forests. Available online: https://drive.google.com/file/d/10aNtgNxLA-icungcCiwLT68mQYjA38WA/view (accessed on 6 February 2020).

- OECD/FAO. OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2019–2028; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2019; Volume 52, ISBN 9789264312456. [Google Scholar]

- FAO; CEPAL; IICA. The outlook for agriculture and rural development in the Americas: A perspective on Latin America and the Caribbean 2019–2020; IICA: San José, Costa Rica, 2019; ISBN 9789292488666. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, P.; Ata-Ul-Karim, S.T.; Singh, B.P.; Wang, H.; Wu, T.; Liu, C.; Fang, G.; Zhou, D.; Wang, Y.; Chen, W. A scientometric review of biochar research in the past 20 years (1998–2018). Biochar 2019, 1, 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panwar, N.L.; Pawar, A.; Salvi, B.L. Comprehensive review on production and utilization of biochar. SN Appl. Sci. 2019, 1, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, D.C.; Gorogantu, S.; Cartensen, H.H.; Almeida Streinwieser, D.; Marin, G.B.; Van Geem, K. Product Distribution from Fast Pyrolysis of Ten Ecuadorian Agricultural Residual Biomass Samples. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Chemical Kinetics (ICCK), Chicago, IL, USA, 21 May 2017. [Google Scholar]

- López, J.E.; Builes, S.; Heredia Salgado, M.A.; Tarelho, L.A.C.; Arroyave, C.; Aristizábal, A.; Chavez, E. Adsorption of Cadmium Using Biochars Produced from Agro-Residues. J. Phys. Chem. C 2020, 124, 14592–14602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paz-Ferreiro, J.; Nieto, A.; Méndez, A.; Askeland, M.P.J.; Gascó, G. Biochar from biosolids pyrolysis: A review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Biochar Foundation Guidelines for a Sustainable Production of Biochar v4.5E. Eur. Biochar Found. 2018, v4.5, 1–22. [CrossRef]

- Mario, A. Heredia Salgado Biomass Thermochemical Conversion in Small Scale Facilities. Ph.D. Thesis, Aveiro University, Aveiro, Portugal, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Constitucional, C. Registro Oficial del Ecuador. Available online: https://www.registroficial.gob.ec/ (accessed on 27 March 2021).

- Environmental and Water Ministry. Codigo Orgánico Del Ambiente; Registro Oficial: Aveiro, Portugal, 2017; pp. 1–92.

- Environmental and Water Ministry. Texto Unificado de Legislacion Secundaria de Medio Ambiente (TULSMA); Registro Oficial: Aveiro, Portugal, 29 March 2017; pp. 1–407.

- Ministerio de Ambiente. Norma de Emisiones al Aire Desde Fuentes Fijas de Combustion; Registro Oficial: Quito, Ecuador, 2015; pp. 1–18.

- Presidencia De La República del Ecuador. Decreto Ejecutivo No.1054; Registro Oficial: Aveiro, Portugal, 2020; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Masson-Delmotte, V.; Zhai, P.; Pörtner, H.-O.; Roberts, D.; Skea, J.; Shukla, P.R.; Pirani, A.; Moufouma-Okia, W.; Péan, C.; Pidcock, R.; et al. Summary for Policymakers. Global Warming of 1.5 °C. An IPCC Special Report on the Impacts of Global Warming of 1.5 °C above Pre-Industrial Levels. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/ (accessed on 4 January 2021).

- Helms, M.M.; Nixon, J. Exploring SWOT analysis where are we now?: A review of academic research from the last decade. J. Strateg. Manag. 2010, 3, 215–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franca, A.S.; Oliveira, L.S. Coffee Processing Solid Wastes: CURRENT Uses and Future Perspectives; Nova Science Publishers Inc.: Lancaster, UK, 2009; ISBN 9781607413059. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, L.S.; Franca, A.S. An Overview of the Potential Uses for Coffee Husks. In Coffee in Health and Disease Prevention; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 281–291. ISBN 9780124095175. [Google Scholar]

- Murthy, P.S.; Naidu, M.M. Sustainable management of coffee industry by-products and value addition A review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2012, 66, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency. Methane Tracker 2021; IEA: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Woolf, D.; Amonette, J.E.; Street-Perrott, F.A.; Lehmann, J.; Joseph, S. Sustainable biochar to mitigate global climate change. Nat. Commun. 2010, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashidi, N.A.; Yusup, S. A review on recent technological advancement in the activated carbon production from oil palm wastes. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 314, 277–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manrique, R.; Vásquez, D.; Ceballos, C.; Chejne, F.; Andrés, A. Evaluation of the Energy Density for Burning Disaggregated and Pelletized Coffee Husks. ACS OMEGA 2019, 4, 2957–2963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saenger, M.; Hartge, E.; Werther, J. Combustion of coffee husks. Renew. Energy 2001, 23, 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaffitzel, F.; Jakob, M.; Soria, R.; Vogt-Schilb, A.; Ward, H. Can Government Transfers Make Energy Subsidy Reform Socially acceptable? A case study on Ecuador. Energy Policy 2019, 137, 111120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chicaiza, D.; Navarrete, P.V.; López, C.C.; Ángel Ortiz, C. Evaluation of municipal solid waste management system of Quito Ecuador through life cycle assessment approach. Rev. Latino-Americana em Avaliação do Ciclo Vida 2020, 4, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Ambiente Programa Nacional para la Gestión Integral de Desechos Sólidos PNGIDS ECUADOR. Available online: https://www.ambiente.gob.ec/programa-pngids-ecuador/ (accessed on 18 February 2020).

- Margallo, M.; Ziegler-Rodriguez, K.; Vázquez-Rowe, I.; Aldaco, R.; Irabien, Á.; Kahhat, R. Enhancing waste management strategies in Latin America under a holistic environmental assessment perspective: A review for policy support. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 689, 1255–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Electricidad y Energía Renovable Plan Maestro de Electricidad 2016–2025. Available online:https://www.celec.gob.ec/hidroagoyan/images/PME2016-2025.pdf (accessed on 17 January 2021).

- Ministerio de Ambiente. Normas Técnicas Ambientales para la Prevención y Control de la Contaminación Ambiental para los Sectores de Infraestructura: Eléctrico, Telecomunicaciones y Transporte (Puertos y Aeropuertos); Registro Oficial: Quito, Ecuador, 2007; Volume 41, pp. 22–27.

- Forte, B.; Coleman, M.; Metcalfe, P.; Weaver, M. The Case for the PYREG Slow Pyrolysis Process in Improving the Efficiency and Profitability of Anaerobic Digestion Plants in the UK. Available online: http://www.wrap.org.uk/sites/files/wrap/DIADINeueAgfeasibilityreport.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2020).

- Garcia-Nunez, J.A.; Pelaez-Samaniego, M.R.; Garcia-Perez, M.E.; Fonts, I.; Abrego, J.; Westerhof, R.J.M.; Garcia-Perez, M. Historical Developments of Pyrolysis Reactors: A Review. Energy Fuels 2017, 31, 5751–5775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, T.; Braghini Junior, A. Technological prospecting in the production of charcoal: A patent study. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 111, 170–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, S.D.F.d.O.M.; Pierkarski, C.M.; Ugaya, M.L.; Donato, D.B.; Júnior, A.B.; De Francisco, A.C.; Carvalho, A.M.M.L. Life Cycle Analysis of Charcoal Production in Masonry Kilns with and without Carbonization Process Generated Gas Combustion. Sustainability 2017, 8, 1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelissen, G.; Pandit, N.R.; Taylor, P.; Pandit, B.H.; Sparrevik, M.; Schmidt, H.P. Emissions and char quality of flame-curtain “Kon Tiki” kilns for farmer-scale charcoal/biochar production. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0154617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparrevik, M.; Adam, C.; Martinsen, V.; Cornelissen, G. Emissions of gases and particles from charcoal/biochar production in rural areas using medium- sized traditional and improved “retort” kilns. Biomass Bioenergy 2015, 72, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Torres-Rojas, D.; Burford, M.; Whitlow, T.H.; Lehmann, J.; Fisher, E.M. Fuel sensitivity of biomass cookstove performance. Appl. Energy 2018, 215, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Kumar, S.; Tyagi, S.K. Design, development and technological advancement in the biomass cookstoves: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 26, 265–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandit, N.R.; Mulder, J.; Hale, S.E.; Schmidt, H.P.; Cornelissen, G. Biochar from “Kon Tiki” flame curtain and other kilns: Effects of nutrient enrichment and kiln type on crop yield and soil chemistry. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0176378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Liu, B.; Liu, G.; Cai, Z.; Zhang, C. Potential Toxic Compounds in Biochar: Knowledge Gaps Between Biochar Research and Safety; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; ISBN 9780128117293. [Google Scholar]

- Lyu, H.; He, Y.; Tang, J.; Hecker, M.; Liu, Q.; Jones, P.D.; Codling, G.; Giesy, J.P. Effect of pyrolysis temperature on potential toxicity of biochar if applied to the environment. Environ. Pollut. 2016, 218, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campuzano, F.; Brown, R.C.; Martínez, J.D. Auger reactors for pyrolysis of biomass and wastes. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 102, 372–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masek, O.; Buss, W.; Roy-poirier, A.; Brownsort, P. Consistency of biochar properties over time and production scales: A characterization of standard materials. Keywords. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2018, 132, 200–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Chang, F.; Wang, C.; Jin, Z.; Wu, J.; Zuo, J.; Wang, K. Pyrolysis and subsequent direct combustion of pyrolytic gases for sewage sludge treatment in China. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2018, 128, 464–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunnigan, L.; Ashman, P.J.; Zhang, X.; Wai, C. Production of biochar from rice husk: Particulate emissions from the combustion of raw pyrolysis volatiles. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 1639–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørmo, E.; Silvani, L.; Thune, G.; Gerber, H.; Peter, H.; Botnen, A.; Cornelissen, G. Waste timber pyrolysis in a medium-scale unit: Emission budgets and biochar quality. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 718, 137335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shackley, S.; Clare, A.; Joseph, S.; McCarl, B.A.; Schmidt, H.-P. Economic evaluation of biochar systems: Current evidence and challenges. In Biochar for Environmental Management Science, Technology and Implementation; Earthscan: London, UK, 2015; pp. 813–852. [Google Scholar]

- Adam, J.C. Improved and more environmentally friendly charcoal production system using a low-cost retort-kiln (Eco-charcoal). Renew. Energy 2009, 34, 1923–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, H.; Taylor, P. Kon-Tiki flame cap pyrolysis for the democratization of biochar production. Ithaka J. biochar Mater. Ecosyst. Agric. 2015, IJ-bea, 338–348. [Google Scholar]

- Woolf, D.; Lehmann, J.; Joseph, S.; Campbell, C.; Christo, F.C.; Angenent, L.T. An open-source biomass pyrolysis reactor. Biofuels, Bioprod. Biorefining 2017, 11, 945–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, M.; Gutzwiller, S.; Zellweger, H. Pulpa Pyro Peru Clean Generation of Biochar and Energy from Coffee Pulp; Okozentrum: Langenbruck, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, J.; Cui, H.; Grace, J.R. Biomass feeding for thermochemical reactors. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2012, 38, 716–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heredia Salgado, M.A.; Coba, S.J.A.; Tarelho, L.A.C. Simultaneous production of biochar and thermal energy using palm oil residual biomass as feedstock in an auto-thermal prototype reactor. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 266, 121804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgado, M.A.H.; Tarelho, L.A.C.; Rivadeneira-Rivera, D.A.; Ramirez, V.; Sinche, D. Energetic valorization of the residual biomass produced during Jatropha curcas oil extraction. Renew. Energy 2019, 146, 1640–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomczyk, A.; Sokołowska, Z.; Boguta, P. Biochar physicochemical properties: Pyrolysis temperature and feedstock kind effects. Rev. Environ. Sci. Biotechnol. 2020, 19, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, K.; Kumar, A.; Zhang, H.; Bellmer, D.; Huhnke, R. Recent advances in utilization of biochar. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 42, 1055–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, O.Y.; Raichle, B.; Sink, S. Impact of biochar on the water holding capacity of loamy sand soil. Int. J. Energy Environ. Eng. 2013, 4, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, J.; Rillig, M.C.; Thies, J.; Masiello, C.A.; Hockaday, W.C.; Crowley, D. Biochar effects on soil biota A review. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2011, 43, 1812–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Jia, M.; Christie, P.; Ali, S.; Wu, L. Use of a hyperaccumulator and biochar to remediate an acid soil highly contaminated with trace metals and/or oxytetracycline. Chemosphere 2018, 204, 390–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xiao, X.; Xu, Y.; Chen, B. Environmental Effects of Silicon within Biochar (Sichar) and Carbon-Silicon Coupling Mechanisms: A Critical Review. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasucka, P.; Pan, B.; Sik Ok, Y.; Mohan, D.; Sarkar, B.; Oleszczuk, P. Engineered biochar A sustainable solution for the removal of antibiotics from water. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 405, 126926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, S.H.; Lam, S.S.; Yek, P.N.Y.; Liew, R.K.; Ma, N.L.; Osman, M.S.; Wong, C.C. Self-purging microwave pyrolysis: An innovative approach to convert oil palm shell into carbon-rich biochar for methylene blue adsorption. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2019, 94, 1397–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilomuanya, M.O.; Nashiru, B.; Ifudu, N.D.; Igwilo, C.I. Effect of pore size and morphology of activated charcoal prepared from midribs of Elaeis guineensis on adsorption of poisons using metronidazole and Escherichia coli O157:H7 as a case study. J. Microsc. Ultrastruct. 2017, 5, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, L.; Zhongsheng, Z.; Zhe, L.; Haitao, W. Removal of nitrogen and phosphorus pollutants from water by FeCl 3 impregnated biochar. Ecol. Eng. 2020, 149, 105792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Ye, S.; Zeng, Z.; Zeng, G.; Tan, X.; Xiao, R. Utilization of biochar for resource recovery from water: A review. Chem. Eng. Process. 2020, 397, 125502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, S.M.; Sembres, T.; Roberts, K.; Whitman, T.; Wilson, K.; Lehmann, J. Biochar Systems for Smallholders in Developing Countries:Leveraging Current Knowledge and Exploring Future Potential for Climate-Smart Agriculture; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-0-8213-9525-7. [Google Scholar]

- Man, K.Y.; Chow, K.L.; Man, Y.B.; Mo, W.Y.; Wong, M.H. Use of biochar as feed supplements for animal farming. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirheidari, A.; Torbatinejad, N.M.; Shakeri, P.; Mokhtarpour, A. Effects of biochar produced from different biomass sources on digestibility, ruminal fermentation, microbial protein synthesis and growth performance of male lambs. Small Rumin. Res. 2019, 183, 106042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, H.; Hagemann, N.; Draper, K.; Kammann, C. The use of biochar in animal feeding. PeerJ 2019, 7, 7373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaini, I.N.; Gomez-Rueda, Y.; García López, C.; Ratnasari, D.K.; Helsen, L.; Pretz, T.; Jönsson, P.G.; Yang, W. Production of H2-rich syngas from excavated landfill waste through steam co-gasification with biochar. Energy 2020, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agirre, I.; Griessacher, T.; Rösler, G.; Antrekowitsch, J. Production of charcoal as an alternative reducing agent from agricultural residues using a semi-continuous semi-pilot scale pyrolysis screw reactor. Fuel Process. Technol. 2013, 106, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, L.; Deng, Y.F.; Wang, F.; Davaritouchaee, M.; Yao, Y.Q. A review on biochar-mediated anaerobic digestion with enhanced methane recovery. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 115, 109373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuoppamäki, K.; Lehvävirta, S. Mitigating nutrient leaching from green roofs with biochar. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2016, 152, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, S.K.; Valenca, R.; Berger, A.W.; Yu, I.K.M.; Xiong, X.; Saunders, T.M.; Tsang, D.C.W. Plenty of room for carbon on the ground: Potential applications of biochar for stormwater treatment. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 625, 1644–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, C.; Cao, C.T.N.; Farrell, C.; Kristiansen, P.E.; Rayner, J.P. Biochar makes green roof substrates lighter and improves water supply to plants Biochar makes green roof substrates lighter and improves water supply to plants. Ecol. Eng. 2014, 71, 368–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez-Riera, D.; Restuccia, L.; Ferro, G.A. The use of Biochar to reduce the carbon footprint of cement-based. Procedia Struct. Integr. 2020, 26, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Kua, H.W. Factors Determining the Potential of Biochar As a Carbon Capturing and Sequestering Construction Material: Critical Review. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2017, 29, 04017086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praneeth, S.; Saavedra, L.; Zeng, M.; Dubey, B.K.; Sarmah, A.K. Biochar admixtured lightweight, porous and tougher cement mortars: Mechanical, durability and micro computed tomography analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 750, 142327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, H.P.; Anca-Couce, A.; Hagemann, N.; Werner, C.; Gerten, D.; Lucht, W.; Kammann, C. Pyrogenic carbon capture and storage. GCB Bioenergy 2019, 11, 573–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, J.; Gaunt, J.; Rondon, M. Biochar sequestration in terrestrial ecosystems a review. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Chang. 2006, 11, 403–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matuštík, J.; Hnátková, T.; Kočí, V. Life cycle assessment of biochar-to-soil systems: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 259, 120998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, C.; Schmidt, H.P.; Gerten, D.; Lucht, W.; Kammann, C. Biogeochemical potential of biomass pyrolysis systems for limiting global warming to 1.5 °C. Environ. Res. Lett. 2018, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duque-Acevedo, M.; Belmonte-Ureña, L.J.; Plaza-Úbeda, J.A.; Camacho-Ferre, F. The management of agricultural waste biomass in the framework of circular economy and bioeconomy: An opportunity for greenhouse agriculture in Southeast Spain. Agronomy 2020, 10, 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masullo, A. Organic wastes management in a circular economy approach: Rebuilding the link between urban and rural areas. Ecol. Eng. 2017, 101, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassilev, S.V.; Baxter, D.; Andersen, L.K.; Vassileva, C.G. An overview of the chemical composition of biomass. Fuel 2010, 89, 913–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tubana, B.S.; Babu, T.; Datnoff, L.E. A Review of Silicon in Soils and Plants and Its Role in US Agriculture: History and Future Perspectives. Soil Sci. 2016, 181, 393–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bier, H.; Gerber, H.; Huber, M.; Junginger, H.; Kray, D.; Lange, J.; Lerchenmüller, H.; Nilsen, P.J. Biochar-Based Carbon Sinks to Mitigate Climate Change; European Biochar Industry Consortium e.V. (EBI): Freiburg, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Vartia, A. Compensate. Available online: https://www.compensate.com/ (accessed on 12 February 2020).

- Nori LLC The NORI Carbon Removal Marketplace. Available online: https://nori.com/ (accessed on 29 October 2020).

- Junginger, H. Carbon Future. Available online: https://carbonfuture.earth/ (accessed on 1 October 2020).

- Schmidt, H.; Kammann, C.; Hagemann, N. Certification of the Carbon Sink Potential of Biochar; Ithaka Institute: Arbaz, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Verra Soil Carbon Quantification Methodology. Available online: https://verra.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/VM0021-Soil-Carbon-Quantification-Methodology-v1.0.pdf (accessed on 29 October 2020).

- WWF Gold Standard. Available online: https://www.goldstandard.org/ (accessed on 17 September 2020).

- Puro PURO.Earth. Available online: https://puro.earth/ (accessed on 15 January 2020).

- Roth, J. Carbon Instead. Available online: http://carboninstead.de/ (accessed on 14 August 2020).

- Raviv, O.; Broitman, D.; Ayalon, O.; Kan, I. A regional Optimization Model for Waste-To-Energy Generation Using Agricultural Vegetative Residuals. Waste Manag. 2016, 73, 546–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Perez, M.; Garcia-Nunez, J.A.; Samaniego, M.R.P.; Kruger, C.E.; Fuchs, M.R.; Flora, G.E. Sustainability, business models, and techno-economic analysis of biomass pyrolysis technologies. In Innovative Solutions in Fluid-Particle Systems and Renewable Energy Management; Tannous, K., Ed.; IGI Global: Campinas, Brazil, 2015; pp. 298–343. ISBN 978-1-4666-8712-7. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Nunez, J.A.; Rodriguez, D.T.; Fontanilla, C.A.; Ramirez, N.E.; Silva Lora, E.E.; Frear, C.S.; Stockle, C.; Amonette, J.; Garcia-Perez, M. Evaluation of alternatives for the evolution of palm oil mills into biorefineries. Biomass Bioenergy 2016, 95, 310–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wunder, S.; Albán, M. Decentralized payments for environmental services: The cases of Pimampiro and PROFAFOR in Ecuador. Ecol. Econ. 2008, 65, 685–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schieb, P.A.; Lescieux-Katir, H.; Thénot, M.; Clément-Larosière, B. An original business model: The integrated biorefinery. In Biorefinery 2030: Future Prospects for the Bioeconomy; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 1–123. ISBN 9783662473740. [Google Scholar]

- Horonjeff, J.; Wiener, J.; Scholz, A. When Co-ops and Venture Capital Meet. Available online: https://www.colorado.edu/lab/medlab/2020/04/16/when-co-ops-and-venture-capital-meet (accessed on 18 November 2020).

- Andrews, A.M. Five Ways Co-Ops Can Access More Capital While Staying True to the Principles. Available online: https://www.thenews.coop/94133/sector/five-ways-co-ops-can-access-more-capital-while-staying-true-to-the-principles/ (accessed on 18 November 2020).

- Jones, E.C. Wealth-based trust and the development of collective action. World Dev. 2004, 32, 691–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, M.L. A life cycle explanation of cooperative longevity. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deloitte Financer l’avenir: Èvolution des stratégies de financement et de capitalisation des coopératives. In Proceedings of the Sommet international des coopératives 2012; PortailCoop, Ed.; HEC Montreal: Québec, QC, Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Soeiro, S.; Ferreira Dias, M. Energy cooperatives in southern European countries: Are they relevant for sustainability targets? Energy Rep. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łapniewska, Z. Cooperatives governing energy infrastructure: A case study of Berlin’s grid. J. Co-op. Organ. Manag. 2019, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heras-Saizarbitoria, I.; Sáez, L.; Allur, E.; Morandeira, J. The emergence of renewable energy cooperatives in Spain: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 94, 1036–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, P. Neo-developmentalism and a “vía campesina” for rural development: Unreconciled projects in Ecuador’s Citizen’s Revolution. J. Agrar. Chang. 2016, 17, 348–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelms, T.C. “The problem of delimitation”: Parataxis, bureaucracy, and Ecuador’s popular and solidarity economy. J. R. Anthropol. Inst. 2015, 21, 106–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, A.G.; Rodrigues, M.; Sotomayor, O. Towards a sustainable bioeconomy in Latin America and the Caribbean: Elements for a regional vision. In Natural Resources and Development series No 193; Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), Ed.; United Nations: Santiago, Chile, 2019; pp. 1–52. ISBN 2664-4541. [Google Scholar]

- Donner, M.; Gohier, R.; de Vries, H. A new circular business model typology for creating value from agro-waste. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 716, 137065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Criteria | Objectives | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | The pyrolysis facility makes effective use of pyrolytic gases to produce thermal energy. | Avoid the direct release of harmful pyrolysis gases and particulate matter emissions to the environment. |

| 2 | The carbonization temperature is continuously recorded and does not fluctuate more than 20%. | Guarantee homogeneity, reproducibility, quality, and traceability of the produced biochar. |

| 3 | The combustion of the pyrolysis gas supports an energy-autonomous carbonization process and fulfills the local/international flue gas composition regulations. | Prevent the use of subsidized fossil fuels to supply the heat required for carbonization and avoid the release of incomplete combustion products within the flue gas stream of the pyrolysis facility. |

| 4 | The external energy used for preheating and to operate the reactor (e.g., electricity, fossil fuels) does not exceed 8% of the agricultural waste’s calorific value. | Minimize the use of subsidized fossil fuels in the post-harvesting facilities. Lower heating value of the coffee husks: 17.8 MJ/kg [29]. |

| 5 | The excess heat produced during the carbonization process is recycled or integrated. | Use the waste heat from the pyrolysis process to provide the thermal energy consumed during the post-harvesting processes, which can promote the replacement of subsidized fossil fuels currently used in, e.g., drying processes. |

| 6 | The physicochemical properties of the produced biochar do not fluctuate more than 15%. Carbon content > 50 wt.%db. H/Corg molar ratio < 0.7. O/Corg molar ratio < 0.4. | Guarantee homogeneity, reproducibility, and quality of the produced biochar. |

| Policies and Standards | Reference | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | The Unified Text of Secondary Environmental Legislation (TULSMA, Texto Unificado de Legislación Secundaria de Medio Ambiente) | [32] |

| 2 | Standard for Gaseous Emissions to the Atmosphere from Stationary Sources of Combustion | [33] |

| 3 | Presidential Decrees 1054 and 1158 | [34] |

| 4 | The National Program for the Integral Management of Solid Waste (PNGIDS, Programa Nacional de Gestión Integral de Desechos Sólidos) | [47] |

| 5 | Environmental technical standards for the prevention and control of environmental pollution for the infrastructure sectors: electric, telecommunications, and transportation (ports and airports) | [50] |

| 6 | The Organic Code of the Environment | [31] |

| Pyrolysis Technology | Selection Criteria | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| Masonry kilns and mud kilns | 🗶 | 🗶 | 🗶 | 🗶 | 🗶 | ✓ |

| Retorts and converters a | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 🗶 | ✓ | ✓ |

| Flame curtain kilns a | 🗶 | 🗶 | 🗶 | ✓ | 🗶 | 🗶 d |

| Top-lit updraft stoves (TLUDs) b | ✓ | 🗶 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 🗶 d |

| Auger-type reactors and rotary kilns c | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ e | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Open source: Cornell University Retort and Pulpa-pyro Reactor f | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ e | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Category | Benefits of the Use of Biochar (1) | References |

|---|---|---|

| Soil | - Increases water-holding capacity, cation exchange capacity, and organic matter content. Reduces irrigation water consumption. - Alters soil pH, especially if the soil is overly acidic. - Provides a suitable medium for the reproduction and maintenance of soil microorganisms. - Reduces bioavailability and ecotoxicological impacts of heavy metals (Cu, Ni, Cd, Pb). - Retains natural and added soil nutrients (N, P, K, Si, Ca) against leaching, such that they can be absorbed again by plants. Increases crop yields. - Improves the organic waste composting process. | [23,26,27,76,77,78,79,80] |

| Water | - Adsorptive removal of chemicals including pharmaceuticals and antibiotics, inks (e.g., methylene blue), and other inorganic pollutants from water. - Prevents the eutrophication of aquatic environments when applied on land, by keeping the nutrients there. It can be also used in filtering bags in the river runoff. | [42,76,81,82,83,84,85] |

| Animal husbandry | - Supplements feed for ruminants (cattle and goats), pigs, poultry (chicken and duck), and fish. - Improves ruminal fermentation and feed efficiency. - Positively affects growth performance, blood profiles, egg yield, abdominal fat weight, meat quality, carcass weight, and nutrient excretion. - Can also be used as bedding material in stables. | [86,87,88,89] |

| Energy | - Source of thermal energy in the production of iron or steel. - Fuel in boilers and cogeneration facilities. - Cooking fuel, barbecue charcoal. - Increases methane yield when used as an additive in anaerobic digestion systems. | [53,54,90,91,92] |

| Green infrastructure | - When used as a substrate in rooftop and vertical gardens, decreases the weight and corresponding load of these infrastructures. - Preserves the ecosystems services linked to urban greenery (when used as a soil conditioner). - Improves the water retention of rain gardens and helps to control stormwater runoff. - When used as a soil conditioner in urban greenery, as well as vertical and rooftop gardens, reduces infiltration and inflow of rainwater controlling sanitary sewer overflow. | [93,94,95] |

| Gray infrastructure: cement and mortars | - The addition of small fractions of biochar (<5 wt.%) increases the strength and toughness of the cement and mortar, as well as the flexural strength. - Decreases density of cement mortar, making it more porous and lightweight). - Reduces thermal conductivity. - Reduces carbon footprint of infrastructures made with cement. - Turns gray infrastructure into long-term carbon sinks. | [96,97,98] |

| Carbon sequestration | - Biochar is recalcitrant in the soils turning them into a long-term carbon sink with several co-benefits for crops (see soil above). - Transfers carbon from the atmosphere into the soils. | [41,99,100,101,102] |

| Strengths | Weaknesses | |

| Internal | - Availability of dry feedstock with a homogeneous particle size stored in a single location. - Farmers’ cooperatives are likely to receive support and non-reimbursable financial aid from NGOs and international forest conservation initiatives. - Sufficient physical space available within processing centers. - Ample distribution network for soil application of biochar on the farms of the members. - Members have experience in the use of organic soil amendments. - Associative values (solidarity, cooperation) are complementary to carbon sequestration services, the circular economy, and the bioeconomy. - Farmers’ cooperatives already have contacts with international customers potentially interested in reducing their carbon footprint. | - Farmers’ cooperatives have a life cycle that depends on qualitative dynamics between the members (e.g., trust, wellbeing perception). - Continuous changes in leadership hinder long-term planning of projects. - Difficulty in access to bank loans and services. - The associative model is rigid and restricts access to external investors or joint ventures. - Difficulty in assembling competent people to manage, operate, or provide maintenance of new technologies. Lack of experience with pyrolysis. - Lack of structured learning or research processes to innovate with pyrolysis technology or biochar applications. - Lack of experience in developing alternative sources of income or new business models beyond the sale of coffee and cocoa. - Farmers’ cooperatives are influenced by the flaws/weaknesses in the People’s Solidarity Economy Law. The level of government support is dependent on political ideology in power. |

| Opportunities | Threats | |

| External | - Emerging carbon marketplaces may help to monetize carbon sequestration services provided by farmers. - There are companies abroad with climate strategies, as well as interested in reducing their carbon footprint and promoting social impact. - There are low-cost, open-source designs for biochar production. - There is research and experience in pyrolysis technology and biochar uses in Ecuador. - Progressive removal of subsidies and rising prices of fossil fuels should spark interest in alternative energy sources, including agricultural waste. - There is still time to be the first innovators in this field in the region. - Synergies can be established in the intersection of carbon sequestration, forest conservation initiatives, the green and gray infrastructure sector, and the animal husbandry sector. - Pyrolysis kilns could carbonize other agricultural waste (e.g., corn cobs, palm oil kernels) to add value. - Potential implementation of new cooperative cycles, for instance, the creation of energy cooperatives to manage pyrolysis facilities. - Partnerships with the academic sector could result in novel carbon-based products and services. - Creation of new jobs and nonfarm sources of income in the agro-industry sector and rural areas. | - Unexpected policy restrictions in the future: at present, there are no specific regulations for biochar production or for its application in soils in Ecuador. - Currently, biochar is not a product within the domestic market of agriculture or animal feed supplements. - The need for high-cost certifications from external/private companies to monetize carbon sequestration services. - Unclear initial investment costs and unavailability of technical support. There are no sales representatives of international manufacturers of pyrolysis equipment in Ecuador. - Pyrolysis technologies adapted to the use of residual forest biomass may not be able to process tropical agricultural waste, such as coffee husks. - Use of biochar in domains other than the soil may break the carbon cycle and the ability to recycle soil nutrients. - Market dynamics, e.g., the higher price of barbecue charcoal compared to the price of biochar for use in agriculture may stimulate its use for energy purposes. - High international demand for biochar may stimulate its exportation, breaking the circular local economy model. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Heredia Salgado, M.A.; Säumel, I.; Cianferoni, A.; Tarelho, L.A.C. Potential for Farmers’ Cooperatives to Convert Coffee Husks into Biochar and Promote the Bioeconomy in the North Ecuadorian Amazon. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 4747. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11114747

Heredia Salgado MA, Säumel I, Cianferoni A, Tarelho LAC. Potential for Farmers’ Cooperatives to Convert Coffee Husks into Biochar and Promote the Bioeconomy in the North Ecuadorian Amazon. Applied Sciences. 2021; 11(11):4747. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11114747

Chicago/Turabian StyleHeredia Salgado, Mario A., Ina Säumel, Andrea Cianferoni, and Luís A. C. Tarelho. 2021. "Potential for Farmers’ Cooperatives to Convert Coffee Husks into Biochar and Promote the Bioeconomy in the North Ecuadorian Amazon" Applied Sciences 11, no. 11: 4747. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11114747

APA StyleHeredia Salgado, M. A., Säumel, I., Cianferoni, A., & Tarelho, L. A. C. (2021). Potential for Farmers’ Cooperatives to Convert Coffee Husks into Biochar and Promote the Bioeconomy in the North Ecuadorian Amazon. Applied Sciences, 11(11), 4747. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11114747