Abstract

The paper is a critical review of different evidence for the interpretation of an extremely important archaeological find, which is marked by some doubt. The unique find, a multiple perforated cave bear femur diaphysis, from the Divje babe I cave (Slovenia), divided the opinions of experts, between those who advocate the explanation that the find is a musical instrument made by a Neanderthal, and those who deny it. Ever since the discovery, a debate has been running on the basis of this division, which could only be closed by similar new finds with comparable context, and defined relative and absolute chronology.

1. Introduction

Discoveries that shed light, directly or indirectly, on the spiritual life of Neanderthals always attract great attention from the professional and lay public. One such find was unearthed in 1995 in Mousterian level D-1 (layer 8a), as a result of long-lasting (1979–1999) excavations in the Palaeolithic cave site of Divje babe I (DB) in western Slovenia, conducted by the ZRC SAZU Institute of Archaeology from Ljubljana. It was a left femur diaphysis, belonging to a one to two-year-old cave bear cub with holes (inventory no. 652), which resembled a bone flute (Figure 1). The object was found cemented into the breccia in the immediate vicinity of Neanderthal hearth, placed into a pit [1,2].

Figure 1.

The perforated femur diaphysis no. 652 from Divje babe I with two complete (nos. 2 and 3) and two partially preserved holes (nos. 1 and 4). Soon after discovery, the question arose whether it was a Neanderthal musical instrument or simply a bone pierced and gnawed by a carnivore (photo Tomaž Lauko, NMS).

The excavation leader, I. Turk, proposed two possible explanations soon after its discovery: An artefact or a pseudo-artefact in the form of a gnawed and teeth-pierced femur diaphysis [1]. According to the first explanation, this find would be the oldest musical instrument [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10]. The main surprise was not the great age of the find (at first 45,000 years, later 50,000–60,000 years), determined with 14C AMS, U/Th, and ESR on accompanying finds of charcoal, cave bear bones and teeth [8,9,11], but its undeniable attribution to Mousterian culture, i.e., Neanderthals. As such, it would represent significant evidence for existence of musical behaviour, long before the spread of anatomically modern humans across Europe that occurred roughly 40,000 years ago. In the last two decades, our view of Neanderthals has changed radically, but at the time of discovery, the idea of the existence of music in Neanderthal culture still seemed revolutionary.

2. Contestable Explanation of the Carnivore Origin of the Holes

The explanation of the find as a pseudo-artefact was immediately unilaterally taken over by F. d’Errico and colleagues [12], G. Albrecht and colleagues [13], P. G. Chase with A. Nowell [14], and later some others [15,16]. Thus, they negated the potential multilateral significance the find could have had for archaeology and other sciences. Advocates of the carnivore origin of the holes have not rested in the years since the discovery of specimen no. 652. They published a series of articles on the same topic. Among them, d’Errico was the only one who micro-scoped the find and explained the findings of the microscopy in accordance with his previous estimate [12], published in Antiquity in 1998 [17,18,19]. I. Turk with colleagues [10,20,21,22,23,24,25] (see also [26]) continuously argumentatively claimed that some of their statements, regarding their explanations about the origin of the holes and damages on the perforated bone, are incorrect [13,14,16,27,28,29]. To obtain more accurate explanation of the find, I. Turk and colleagues performed and published a series of experiments on perforating fresh brown bear femur diaphyses, using models of wolf, hyena, and bear dentitions (Figure 2), as well as replicas of Palaeolithic tools that were present in various Mousterian levels in DB [20,21,30,31]. Various musical tests of the find were also performed, which was reconstructed several times for this purpose [7,32,33,34,35,36,37].

Figure 2.

Experimental piercing of a fresh femur of a young brown bear using a bronze model of hyena’s dentition and the ZWICK/Z 050 machine for measuring compressive force (photo Ivan Turk, ZRC SAZU).

After I. Turk and colleagues contested the arguments for the carnivore origin of the holes in numerous publications and offered arguments for their anthropic origin, it was up to advocates of the carnivore origin to refute their findings argumentatively, which they have not done so far. Their discussion of the find is distinctly one-sided and, with one sole exception [13], included no experiments. They presented certain erroneous claims to support their explanation, e.g., about the number of holes [14,19,27], contra [20,22,23], how the holes cannot be made in any other way than by drilling [13,28], contra [10,21,30], the placement of holes on the thinnest parts of the cortical bone [13,14,16], contra [22,23,24], actual possibilities of teeth grip in connection to holes and gnawing marks [13,14,16,18,19], contra [20,24,25], the sound capabilities of the musical instrument, if that is what the find actually is [19,27], contra [7,36,37,38], the inappropriateness of a cave bear femur as a support for a musical instrument in comparison to the supports from bird bones [29], contra [7,36,37,38], and about the frequency of gnawing marks [18] (Figure 9 from Reference [18]), Ref. [19], which in certain cases can also be explained as corrosion formations [10,39]. Corrosion was found to be especially strong in the layer containing the find [10,40].

Supporters of the anthropic origin of the holes were also mistaken; e.g., about the original number of holes [4] and the original length of the musical instrument [35]. The first reconstructions of the find intended to research its musical capabilities, which places the mouthpiece into the large notch on the distal metaphysis, and which consequentially did not consider the opposite hole (at the time supposed to be a thumb hole because of its proximity to the mouthpiece), were also erroneous [31,32,34]. Due to the wrong orientation, the capability of the find as a musical instrument was reduced, and a remnant of the straight edge sharpened from both sides on the proximal part of the diaphysis, which functions on the musical instrument as the cutting edge of the mouthpiece, was overlooked [10,37] (Figure 9 from Reference [10]). It should be noted that we are dealing here with the first example of a bevelled mouthpiece edge. A bevelled mouthpiece edge, which enables better musical performance of the instrument is not known in later Upper Palaeolithic wind instruments, which are made of mammal limb bones. At already thin bone cortex of bird bones, the additional sharpening of the mouthpiece edge is not necessary to achieve better sonority.

When defining the holes on the femur diaphysis no. 652, which are the key component of all wind instruments, we have to start from certain findings of research of all cave bear finds, acquired with wet sieving of all sediments during the excavations of I. Turk, as well as from the findings of his fresh bone piercing experiments. In DB, the main damage to the bones was, in addition to humans, made by wolves (all remains belong to 30 individuals at the most) and not cave hyenas (zero specimens and no indirect proof, such as coprolites and digested bones) [25], contra [16]. The complete and partial holes on the femur diaphysis are undoubtedly of mechanical origin. Namely, both have a funnel-shaped inner edge, which occurs during piercing with a tooth or a pointed tool. Experiments show that the compression of the diaphysis with sharp (unworn) teeth or striking it with a pointed tool result in the longitudinal cracking of the compact bone [20]. Longitudinal cracks are present on some of the fossil bones that were undoubtedly pierced by carnivores [16] (Figures 5 and 6 from Reference [16]). Thus, the femur or some other tubular bone, with removed meta- and epiphyses, usually breaks in half longitudinally during piercing and widening of the hole(s) [16] (Figure 6 from Reference [16]). This is, however, not true for compression and piercing with strongly worn teeth and blunt pointed tools. A crack on the posterior side of the femur diaphysis no. 652 (Figure 1), which zigzags longitudinally from one end to the other is only superficial, and occurs during weathering in the course of fossilization. It is significantly different from the continuous, rectilinear in-depth crack that occurred on fresh bones during experimental piercing with metal models of carnivore dentition. Since the femur diaphysis no. 652 is not cracked in this way, solely worn teeth or blunt pointed tools can be considered to have produced the holes.

Both partial holes, which advocates of the carnivore origin of the holes considered to be evidence of bites, can be explained differently. V-shaped fractures start on both ends of the diaphysis in the partial hole, meaning that the holes came first and both fractures followed (Figure 1). If the fractures had been made simultaneously with the holes, three cracks would certainly have occurred: Two connected to the fracture and the third one on the diaphysis, with its starting point in the remains of the hole [13] (Figure 10.3 and p. 8, point 4 from Reference [13]). There is no third crack on either of the partial holes. Among 550 cave bear femur diaphyses without epiphyses, similar in size to specimen no. 652 from various layers in DB, only two are pierced and none with the V-fracture and a partial hole.

Judging from the shape and size of the holes, we agree with F. d’Errico [12,18] that they could have been pierced primarily with canines (Figure 3). C. Diedrich [16] believes that all holes in the bones of cave bear from different sites were made exclusively by premolars and molars. According to the first explanation, primarily an adult cave bear is possible, while, according to the second, it would have to be an adult cave hyena which was, like all hyenas, specialised for crushing bones. Frequent in vivo damage on the canine teeth of adult cave bears indicates their rough use. Measured forces from our experiments with models of various carnivore dentitions reveal that piercing with canine teeth takes one-time greater force than piercing with molars and two-times greater force if the tip of canine tooth is blunt [20]. Such forces are on the verge of the capability of the largest carnivores [41,42]. The oval shape of one of the holes and possible antagonist canine impression on the opposite, anterior side connected to it are not in line with the grip and occlusion of canine teeth [10,24], contra [18]. Congruity with the occlusion can be achieved only if the diaphysis is placed lengthwise to the teeth line in the sagittal direction. Such a bite would be highly unlikely, if possible at all. Due to the different shape of teeth tips and shape of the holes (Figure 3) and the unusual longitudinal femur grip considering the only possible dent (pitting after d’Errico [18] (Figure 9 from Reference [18]) of the antagonist tooth [25], cave hyena and the grip with so-called crushing teeth, which is referred to by C. Diedrich [16], is not an option. As stated above, there is also no direct and indirect evidence of the presence of hyena at DB. The same as for the bite of a hyena is true for the bite of a wolf, which is the second best represented carnivore at the site, next to cave bear. The latter is represented with several thousand individuals. It is also not possible to make a partial hole and a complete hole one beneath the other and simultaneously an emphasised depression right by hole no. 3 (Figure 3f, Figure 5) with just any tooth [24], contra [16,18].

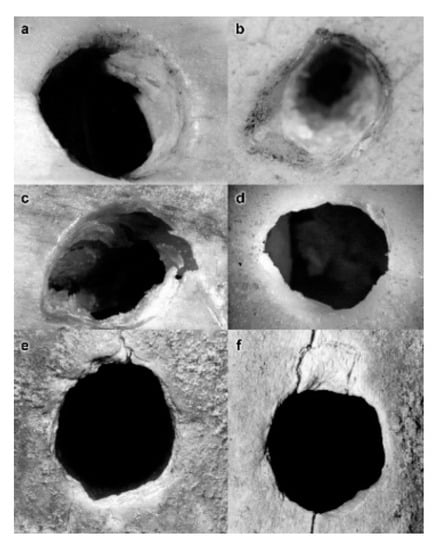

Figure 3.

Experimental holes on juvenile femur diaphysis of brown bear made by: (a) a bear’s canine tooth, hole size 8.2 × 8.2 mm; (b) a hyena’s lower canine tooth, hole size 6.5 × 8.3 mm; (c) a hyena’s 3rd upper premolar, hole size 6.5 × 9.0 mm; (d) a hole made by a pointed stone tool and bone punch, size 6.0 × 7.4 mm (e,f) complete holes no. 2 (size 8.2 × 9.7 mm) and 3 (size 8.7 × 9.0 mm) on the femur from DB no. 652 (ZRC SAZU, Archive of Institute of Archaeology).

Many juvenile femur diaphyses, and other tubular bones of extremities in DB and elsewhere have a bigger distal or proximal semi-circular notch, which is typical carnivore damage. Such a notch also occurs on the distal metaphysis of femur no. 652 from DB (Figure 1). Considering the circumstances, it can be attributed to a wolf, with which P.G. Chase and A. Nowel also agree [14]. Undisputable traces of gnawing on both ends of the diaphysis cannot be linked with certainty to the occurrence of both complete holes and at least one partial hole [10,24], contra [18]. Since it was possible for carnivores to damage Palaeolithic osseous artefacts and leave traces of teeth on them, which is proven by some of the gnawed osseous points [20] (Figure 20 from Reference [20]), ([43] p. 257, Photo 1), this could have happened to femur diaphysis no. 652 at some later time. Most probably, it was at that time that both V-fractures with the starting point in the hole, from which only a partial hole could have remained both times, could have been made.

3. Anthropic Origin of the Holes

Due to the shortcomings the explanation of F. d’Errico and his colleagues regarding the carnivore origin of the holes and damage on femur diaphysis no. 652, more attention is warranted to the alternative explanation of the find and findings connected to it, which are based on the results of appropriate experiments and on indirect evidence from archaeological finds in Mousterian levels of DB.

When piercing bones Neanderthals could imitate carnivores and use pointed tools and the dynamic force of strikes, instead of the compression force of teeth. Holes can be carved into the diaphysis with pointed stone tools [30] found in the Mousterian levels of DB [44]. The bone does not crack during this procedure. The edge of such holes is irregular and serrated, just as with holes on the specimen no. 652, while the edge of holes made by a tooth is generally smooth, depending on the thickness of the cortical bone (Figure 3). Clearly recognisable tool marks are not always present as was attested by F. d’Errico. Namely, six experimentally carved holes were put under microscopic examination. Tool marks were detected on only half of them [19]. However, characteristic damage, such as a broken tip and other fractures, does occur on the tools. Such damage is also present on some of the Mousterian tools from DB [10,20,31] (Figure 4). Holes can also be made with a blunt ad hoc bone punch, struck with a wooden hammer, if a dent has previously been carved into the cortical bone. The holes produced by this technique are morphologically identical to the holes on the specimen no. 652 and completely lack the conventional manufacture marks [21].

Figure 4.

Tools suitable for perforating cortical bone: Pointed stone tools (the first on the right has a broken tip) and bone punches from the Mousterian layers of Divje babe I (photo Tomaž Lauko, NMS).

Whether the bone will crack depends on the shape of the punch point (blunt or sharp). In Mousterian levels of DB, beside rare undisputable fragments of bone and antler points, some ad hoc punches with rounded tips were found [23,45] (Figure 4).

At first glance, such artificially made holes on the diaphysis resemble holes made with teeth. The latter are almost always in the vicinity of the epiphyses and only exceptionally on juvenile diaphyses of the approximately same size, such as specimen no. 652 [16]. This is conditioned with the ability of large carnivores, i.e., physical restriction regarding the grip and muscle strength, and with the thinner cortical bone near epiphyses. Unlike animals, man was able to pierce holes along the entire femur diaphysis, regardless of the thickness of the cortical bone. While puncturing bones, people could choose among significantly more methods than animals, which instinctively always do exactly the same. Therefore, in the case of the artefact, it is easier to substantiate the problematic damage, including the above-mentioned depression near hole no. 3 on the posterior side of the diaphysis. Namely, in its vicinity, there are two parallel micro-scores on the abraded surface of the cortical bone (Figure 5), which could be interpreted as cut marks made by stone tools. These micro-scores are never mentioned by advocates of the carnivore origin of the holes. The possibility that people used a femur, the distal end of which was previously damaged by carnivores, is not ruled out. Regarding the absence of other microscopic traces related to manufacture, they could have been erased due to extremely strong corrosion in the layer comprising the find. Only the more distinct scores were preserved, as well as the dent(s) (pitting after F. d’Errico [18]) made by teeth, which, considering their position, cannot be connected with certainty to the production of holes by compression and piercing with teeth. Due to their orientation and shape, all scores and dents, recognized by d’Errico and colleagues, cannot be attributed to carnivores. Carnivores make scores with their teeth that are perpendicular or slightly oblique to the axis of the diaphysis. They are not able to make a score subparallel to the axis of the diaphysis with their bites [10] (Figure 9 from Reference [10]). Some of the dents must have been made by corrosion, which was not considered by d’Errico and colleagues [39]. At least one longitudinal score could be a tool mark.

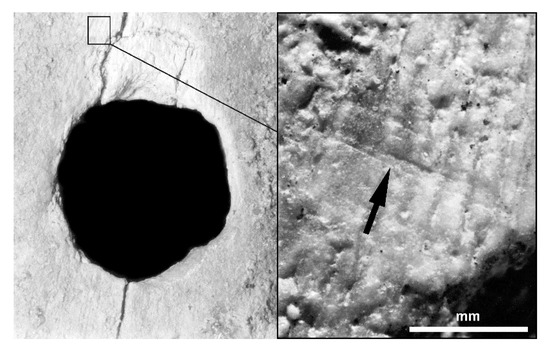

Figure 5.

Depression near hole no. 3 on the posterior side of the diaphysis and location of two parallel micro-scores on the abraded surface of cortical bone (marked with an arrow) (ZRC SAZU, Archive of Institute of Archaeology).

The strongest argument for the thesis that, the DB perforated femur is indeed a deliberately crafted musical instrument, comes from experimental musical research on a reconstructed find. It was determined that the artificially transformed juvenile diaphysis is ideal in shape and length for the performance of music using a special playing technique [36,37]. Following the directions of I. Turk [22], in 2010, the missing parts, and both partial holes of the original, were reconstructed on the left cave bear juvenile femur of the size of the original (Figure 6). Due to practical reasons, the mouthpiece of the reconstructed musical instrument was made on the straight edge of the widened part of medullary cavity. This edge fits lips better than the edge of the narrowed part. Later, professional musician L. Dimkaroski established that on the original, the remnant of the straight part of this edge is bevelled on both sides of the cortical bone and could as such function as the perfected cutting edge of the mouthpiece [37]. Considering the position of the edge of the mouthpiece and torsion of the diaphysis, the diaphysis of the left femur is also handier for a right-handed musician, while a right femur diaphysis would be more suitable for a left-handed player. All contemporary music genres can be played on the thus reconstructed musical instrument. The comparative acoustic analysis and tests revealed its great musical capability. With a musical capability of 3½ octaves [37] (a CD in the appendix), the reconstructed musical instrument from Divje babe I surpasses the musical capability of reconstructed Aurignacian osseous wind instruments, made from the bones of large birds [38,46,47].

Figure 6.

Reconstruction of the Neanderthal musical instrument from Divje babe I. The reconstructed parts are in white plaster. The position of the bevelled cutting edge of the mouthpiece is marked by an arrow (photo Tomaž Lauko, NMS).

4. Conclusions

If the holes on femur no. 652 are not equated with the obvious and frequent impressions of teeth, i.e., punctures with the impressed cortical bone [16] (Figure 4: 9b–11b; Figure 7: 2b from Reference [16]) – on meta- and epi-physes from cave bear sites, as is done by d’Errico and some of his adherents, the find does not have a suitable comparison in collections of pierced limb bones of cave bear [16,48]. The exception is the diaphysis of a juvenile femur with three holes from the Aurignacian cave site Istállóskő in Hungary [6,49], which is currently not considered to be a potential musical instrument, due to numerous more convincing new finds of Aurignacian wind instruments in cave sites of the Swabian Jura [50] and the French Pyrenees [51].

Currently, this unique find fulfils all conditions on the basis that it can be defined as the oldest known musical instrument. These are: clear archaeological and stratigraphic context [44], dating [8,9,11], explanation of manufacturing [21], musical verification [36,37], ([47] (p. 458), contra [19] p. 55), and good comparisons in later periods [52]. In a preserved state, the find is not suitable for playing music. Playing was enabled by the reconstruction based on concrete data and the well-founded assumption that the reconstructed parts were removed by a wolf, prior to cementation. Similarly damaged is the Upper Palaeolithic musical instrument from the loess layer in the open-air site Grubgraben (Austria) [52] (Figures 2 and 3 form the Reference [52]). Due to the fine texture of the loess, the damage on the Grubgraben flute could have occurred exclusively prior to its inclusion into the sediment. Presumably, it was damaged by a wolf occasionally feeding on the remains of the prey of Palaeolithic hunters.

The find of the Mousterian musical instrument from DB has certain advantages in relation to other, declaratively the oldest similar instruments from the sites in the Swabian Jura, in regards to context, stratigraphy, reconstruction, and morphometric characteristics. The context and stratigraphy, supported by indirect 14C AMS, U/TH, and ESR dates [8,9,11], are indisputable because the find, firmly cemented into the breccia, could not move within the sediment or be mixed with older finds due to detected gaps in sedimentation. One of them occurred above the cemented part of layer 8, where the musical instrument was found [53].The leading Aurignacian artefact – the point with the split base – found in the youngest Pleistocene combined layer 2–3, two metres higher, enables the cultural paralleling of Aurignacian level with sites of the Swabian Jura and simultaneously indisputably proves the greater relative age of specimen no. 652, in comparison to the finds of musical instruments in the Swabian Jura and elsewhere [50].

The reconstruction of the DB musical instrument is more reliable than the reconstructions of Swabian finds, in which either the length or the mouthpiece are not preserved [46,47,50,54]. The morphometric characteristics of the DB musical instrument are such that, even on the basis of physical laws, despite the smaller length, they enable a greater musical capability in comparison to Swabian finds. Excuses of everything being dependent on the interpreter are only partly valid. This has also been confirmed by the unpublished musical experiments of professional musician L. Dimkaroski (personal communication) with the replica of Swabian wind instrument GK 1 and comparative acoustic calculations of F. Z. Horusitzky [38] for Swabian instruments GK 1 and GK 3.

The musical instrument from Divje babe I, which predates 50 ka, firmly supported with a Mousterian (Neanderthal) context and chronology, remains the strongest material evidence so far for Neanderthal musical behaviour. According to the present knowledge and archaeological context of the find, there are no obstacles for the find to be interpreted as a Neanderthal musical instrument.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.T. and I.T.; methodology, I.T.; investigation, I.T. and M.T.; writing—original draft preparation, M.T., I.T. and M.O.; writing—review and editing, M.T.; supervision, M.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors acknowledge the financial support from the Slovenian Research Agency (P6-0283 and P6-0064). We also thank ZRC SAZU Institute of Archaeology for part-financing from its current assets.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Turk, I.; Dirjec, J.; Kavur, B. The oldest musical instrument in Europe discovered in Slovenia? Razpr. 4. Razreda Sazu 1995, 36, 287–293. [Google Scholar]

- Turk, I.; Dirjec, J.; Kavur, B. Description and explanation of the origin of the suspected bone flute. In Mousterian «Bone Flute» and Other Finds from Divje Babe I Cave Site, Slovenia; Turk, I., Ed.; Opera Instituti Archaeologici Sloveniae 2: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 1997; pp. 157–175. [Google Scholar]

- Lau, B.; Blackwell, B.A.B.; Schwarcz, H.P.; Turk, I.; Blickstein, J.I. Dating a flautist? Using ESR (Electron spin resonance) in the Mousterian cave deposits at Divje babe I, Slovenia. Geoarchaeology 1997, 12, 507–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otte, M. On the suggested bone flute from Slovenia. Curr. Anthropol. 2000, 41, 271–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otte, M. La mobilité rapide, caractère propre au Paléolithique supérieur d’Eurasie. In Modes de Contacts et de Déplacements au Paléolithique Euroasiatique/Modes of Contact and Mobility during the Eurasian Palaeolithic; Otte, M., Ed.; 28-31 mai 2012. ERAUL 140; Actes du Colloque International de la Commission 8 de l’UISPP, Université de Liège: Liège, Belgium, 2014; pp. 693–706. [Google Scholar]

- Horusitzky, F.Z. Les flûtes paléolithiques: Divje Babe I, Istállóskő, Lokve, etc. Point de vue des experts et des contestataires (Critique de l’appréciation archéologique du spécimen no. 652 de Divje Babe I, et arguments pour la défence des spécimens Pb 51/20 et Pb 606 de MNM de Budapest). Arheol. Vestn. 2003, 54, 45–66. [Google Scholar]

- Horusitzky, F.Z. Analyse acoustique de la flûte avec souffle proximal. In Divje babe I. In Upper Pleistocene Palaeolithic Site in Slovenia. Part 2: Archaeology; Turk, I., Ed.; Opera Instituti Archaeologici Sloveniae 29: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2014; pp. 223–233. [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell, B.A.B.; Yu, E.S.K.; Skinner, A.R.; Turk, I.; Blickstein, J.I.B.; Turk, J.; Yin, V.S.W.; Lau, B. ESR-Dating at Divje babe I, Slovenia. In Divje Babe I: Upper Pleistocene Palaeolithic site in Slovenia, Part 1: Geology and Palaeontology; Turk, I., Ed.; Opera Instituti Archaeologici Sloveniae 13: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2007; pp. 123–157. [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell, B.A.B.; Yu, E.S.K.; Skinner, A.R.; Turk, I.; Blickstein, J.I.B.; Skaberne, D.; Turk, J.; Lau, B. Dating and paleoenvironmental interpretation of the Late Pleistocene archaeological deposits at Divje Babe I, Slovenia. In The Mediterranean from 50 000 to 25 000 BP: Turning Points and New Directions; Calbet, M., Szmidt, C., Eds.; Oxbow Books: Oxford, UK, 2009; pp. 179–210. [Google Scholar]

- Turk, M.; Turk, I.; Dimkaroski, L.; Blackwell, B.A.B.; Horusitzky, F.Z.; Otte, M.; Bastiani, G.; Korat, L. The Mousterian musical instrument from the Divje babe I cave (Slovenia): Arguments on the material evidence for Neanderthal musical behaviour. L’anthropologie 2018, 122, 679–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, D.E. Radiocarbon dating of bone and charcoal from Divje babe I cave. In Mousterian «Bone Flute» and Other Finds from Divje Babe I Cave site, Slovenia; Turk, I., Ed.; Opera Instituti Archaeologici Sloveniae 2: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 1997; pp. 51–64. [Google Scholar]

- d’Errico, F.; Villa, P.; Pinto Llona, A.C.P.; Idarraga, R.R.A. Middle Palaeolithic origin of music? Using cave-bear bone accumulations to assess the Divje Babe I bone “flute”. Antiquity 1998, 72, 65–79. [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht, G.; Holdermann, C.S.; Kerig, T.; Lechterbeck, J.; Serangeli, J. “Flöten” aus Bärenknochen—Die frühesten Musikinstrumente? Archäologisches Korresp. 1998, 28, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Chase, P.G.; Nowell, A. Taphonomy of a suggested Middle Paleolithic bone flute from Slovenia. Curr. Anthropol. 1998, 39, 549–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morley, I. The Prehistory of Music; University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013; pp. 1–280. [Google Scholar]

- Diedrich, C.G. ‘Neanderthal bone flutes’: Simply products of Ice Age spotted hyena scavenging activities on cave bear cubs in European cave bear dens. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2015, 2, 140022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- d’Errico, F. Just a bone or flute? The contribution of taphonomy and microscopy to the identification of prehistoric pseudo-musical instruments. In The Archaeology of Sound: Origin and Organisation; Hickmann, E., Kilmer, A.D., Eichmann, R., Eds.; Studien zur Musikarchäologie, 3, Orient-Archäologie, 10: Rahden/Westf., Germany, 2002; pp. 89–90. [Google Scholar]

- d’Errico, F.; Henshilwood, C.; Lawson, G.; Vanhaeren, M.; Tillier, A.M.; Soressi, M.; Bresson, F.; Maureille, B.; Nowell, A.; Lakarra, J.; et al. Archaeological evidence for the emergence of language, symbolism, and music: An alternative multidisciplinary perspective. J. World Prehistory 2003, 17, 1–70. [Google Scholar]

- d’Errico, F.; Lawson, G. The sound paradox: How to assess the acoustic significance of archaeological evidence? In Archaeoacoustics; Lawson, G., Scarre, C., Eds.; McDonald Institute Monographs: Cambridge, UK, 2006; pp. 41–57. [Google Scholar]

- Turk, I.; Dirjec, J.; Bastiani, G.; Pflaum, M.; Lauko, T.; Cimerman, F.; Kosel, F.; Grum, J.; Cevc, P. New analyses of the »flute« from Divje babe I (Slovenia). Arheol. Vestn. 2001, 52, 25–79. [Google Scholar]

- Turk, I.; Bastiani, G.; Blackwell, B.A.B.; Horusitzky, F.Z. Putative Mousterian flute from Divje babe I (Slovenia): Pseudoartefact or true flute, or who made the holes? Arheol. Vestn. 2003, 54, 67–72. [Google Scholar]

- Turk, I.; Pflaum, M.; Pekarovič, D. Results of computer tomography of the oldest suspected flute from Divje babe I (Slovenia): Contribution to the theory of making holes in bones. Arheol. Vestn. 2005, 56, 9–36. [Google Scholar]

- Turk, I.; Blackwell, B.A.B.; Turk, J.; Pflaum, M. Results of computer tomography of the oldest suspected flute from Divje babe I (Slovenia) and its chronological position within global palaeoclimatic and palaeoenvironmental change during Last Glacial. L’Anthropologie 2006, 110, 293–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turk, I.; Dirjec, J.; Turk, M. Flute (musical instrument) 19 years after its discovery. Critique of the taphonomic interpretation of the find. In Divje babe I. Upper Pleistocene palaeolithic site in Slovenia. Part 2: Archaeology; Turk, I., Ed.; Opera Instituti Archaeologici Sloveniae 29: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2014; pp. 235–268. [Google Scholar]

- Turk, I.; Turk, M.; Toškan, B. Could a cave hyena have made a musical instrument? A reply to Cajus G. Diedrich. Arheol. Vestn. 2016, 67, 401–407. [Google Scholar]

- Niţu, E.C. Some observations on the supposed natural origin of the Divje babe I flute. Ann. D’université Valahia Targovistesection D’archéologie Et D’histoire 2015, 17, 33–44. [Google Scholar]

- Nowell, A.; Chase, P.G. Is a cave bear bone from Divje Babe, Slovenia, a Neanderthal flute? In The Archaeology of Early Sound: Origin and Organization; Hickmann, E., Eichmann, R., Eds.; Studien zur Musikarchäologie, 4, Orient-Archäologie, 12: Rahden/Westf., Germany, 2002; pp. 69–81. [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht, G.; Holdermann, C.S.; Serangeli, J. Towards an archaeological appraisal of specimen N° 652 from Middle-Palaeolithic level D/(Layer 8) of the Divje babe I. Arheol. Vestn. 2001, 52, 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Holdermann, C.S.; Serangeli, J. Einige Bemerkungen zur Flöte von Divje babe I (Slowenien) und deren Vergleichsfunde aus dem österreichischen Raum und angrenzenden Gebieten. Archäologie Österreichs 1998, 9, 31–38. [Google Scholar]

- Bastiani, G.; Turk, I. Results from the experimental manufacture of a bone flute with stone tools. In Mousterian “Bone Flute” and Other Finds from Divje Babe I Cave Site in Slovenia; Turk, I., Ed.; Opera Instituti Archaeologici Sloveniae 2: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 1997; pp. 176–178. [Google Scholar]

- Kunej, D.; Turk, I. New perspectives on the beginning of music: Archaeological and musicological analysis of a Middle Palaeolithic Bone «Flute». In The Origins of Music; Wallin, N.L., Merker, B., Brown, S., Eds.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA; London, UK, 2000; pp. 235–268. [Google Scholar]

- Omerzel-Terlep, M. Bone flutes. The beginning of the history of instrumental music in Slovenia, Europe and the world. Etnolog 1996, 6, 292–294. [Google Scholar]

- Omerzel-Terlep, M. A typology of bone whistles, pipes and flutes and presumed palaeolithic wind instruments in Slovenia. In Mousterian «Bone Flute» and Other Finds from Divje Babe I Cave Site, Slovenia; Turk, I., Ed.; Opera Instituti Archaeologici Sloveniae 2: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 1997; pp. 199–218. [Google Scholar]

- Kunej, D. Acoustic findings on the basis of the reconstruction of a presumed bone flute. In Mousterian «Bone Flute» and Other Finds from Divje Babe I Cave Site, Slovenia; Turk, I., Ed.; Opera Instituti Archaeologici Sloveniae 2: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 1997; pp. 185–197. [Google Scholar]

- Fink, B. Neanderthal Flute. Oldest Musical Instrument’s 4 Notes Matches 4 of do, re, Mi scale. Musicological Analysis. 1997. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20070219094811/http://www.greenwych.ca:80/fl-compl.htm (accessed on 3 February 2020).

- Dimkaroski, L. Musikinstrument der Neanderthaler. Zur Diskussion um die moustérienzaitliche Knochenflöte aus Divje babe I, Slowenien, aus technischer und musikologischer Sicht. Mittelungen Der Berl. Ges. Für Anthropol. Ethnol. Und Urgescichte 2011, 32, 45–54. [Google Scholar]

- Dimkaroski, L. Musical research into the flute. From suspected to contemporary musical instrument. In Divje Babe I. Upper Pleistocene Palaeolithic site in Slovenia. Part 2: Archaeology; Turk, I., Ed.; Opera Instituti Archaeologici Sloveniae 29: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2014; pp. 215–222. [Google Scholar]

- Horusitzky, F.Z. Comparaison Musicale De L’instrument De Divje Babe Avec Les Trouvailles de la Montagne De Souabe; Archive of ZRC SAZU Institute of Archaeology: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2017; pp. 1–11, Unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Tuniz, C.; Bernardini, F.; Turk, I.; Dimkaroski, L.; Mancini, L.; Dreossi, D. Did Neanderthals play music? X-ray computed microtomography of the Divje babe ‘flute’. Archaeometry 2012, 54, 581–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turk, I.; Skaberne, D.; Blackwell, B.A.B.; Dirjec, J. Assessing humidity in the Upper Pleistocene karst environment. Palaeomicroenvironments at Divje babe I, Slovenia. In Water and Life in a Rocky Landscape. Kras; Mihevc, A., Ed.; ZRC Publishing: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2005; pp. 173–198. [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen, P.; Adolfssen, J.S. Bite forces, canine strength and skull allometry in carnivores (Mammalia, Carnivora). J. Zool. 2005, 266, 133–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiansen, P.; Wroe, S. Bite forces and evolutionary adaptations to feeding ecology of carnivores. Ecology 2007, 88, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Bayón, I.; Straus, L.G.; Léotard, J.-M.; Lacroix, P.; Teheux, E. L’industrie osseuse du Magdalenien du Bois Laiterie. In La grotte du Bois Laiterie; Otte, M., Straus, L.G., Eds.; ERAUL 80: Liège, Belgium, 1997; pp. 257–277. [Google Scholar]

- Turk, I. (Ed.) Divje Babe I. Upper Pleistocene Palaeolithic site in Slovenia. Part 2: Archaeology; Opera Instituti Archaeologici Sloveniae 29: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2014; pp. 1–456. [Google Scholar]

- Turk, M.; Košir, A. Mousterian osseous artefacts? The case of Divje babe I, Slovenia. Quat. Int. 2016, 450, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potengowski, A.F.; Münzel, S.C. Die musikalische »Vermessung« paläolithischeer Blasinstrumente der Schwäbischen Alb anhand von Rekonstruktionen. Anblastechniken, Tonmaterial und Klangwelt. Mitt. Der Ges. Für Urgesch. 2015, 24, 173–191. [Google Scholar]

- Conard, N.J.; Malina, M.; Münzel, S.C. Eine Mammutelfenbeinflöte aus dem Aurignacien des Geissenklösterle. Neue Belege für eine musikalische Tradition im frühen Jungpaläolithikum auf der Shwäbischen Alb. Archäologisches Korresp. 2004, 34, 447–462. [Google Scholar]

- Brodar, M. Fossile Knochendurchlochungen. In Ivan Rakovec Volume; Grafenauer, S., Pleničar, M., Drobne, K., Eds.; Razprave 4. Razreda SAZU: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 1985; Volume 26, pp. 29–48. [Google Scholar]

- Horusitzky, F.Z. Eine Knochenflöte aus der Höhle von Istállóskő. Acta Archeol. Acad. Sci. Hung. 1955, 5, 133–140. [Google Scholar]

- Conard, N.J.; Malina, M.; Münzel, S.C. New flutes document the earliest musical tradition in southwestern Germany. Nature 2009, 460, 737–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buisson, D. Les flûtes paléolithiques d’Isturitz (Pyrénées-Atlantiques). Bull. De La Société Préhistorique Française 1990, 87, 420–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einwögerer, T.; Käfer, B. Eine Jungpaläolitische Knochenflöte aus der Station Grubgraben bei Kammern, Niederösterreich. Archäologisches Korresp. 1998, 28, 21–30. [Google Scholar]

- Skaberne, D.; Turk, I.; Turk, J. The Pleistocene clastic sediments in the Divje babe I cave, Slovenia, Palaeoclimate (part 1). Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2015, 438, 395–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Münzel, S.; Seeberger, F.; Hein, W. The Geissenklösterle Flute—Discovery, Experiments, Reconstruction. Studien zur Musikarchäologie III: Archäologie früher Klangerzeugung und Tonordnung. Musikarchäologie in der Ägäis und Anatolien; Orient-Archäologie 10: Rahden/West, Germany, 2002; pp. 107–118. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).