Abstract

The current technological evolution allows us to easily and quickly obtain more information, computing capacity, communication and connectivity, in addition to allowing new forms of collaboration between disperse networks of diversified actors. This new reality not only offers enormous potential for innovation and enhanced performance for organizations but also, extends beyond the classic boundaries to affect individuals, other organizations and society in general. At the same time, this reality makes the ability of organizations to uphold their competitive advantage more challenging, since the control of the elements of their operating environment decreases drastically as they increasingly control the elements of the same environment. This is how the digital transformation of organizations becomes unavoidable, because otherwise they tend to disappear. In this context, it is necessary to infer our students’ methods for researching, identifying and taking solutions about if organizations in Portugal are already living the aforementioned digital transformation or if they are aware of the need to adapt to this new reality. The main goal of this research formatted as educational approach, is to evaluate and compare the current state of digital adoption in terms of the preparation according to the prevailing technological categories (pillars and innovation accelerators), as well as future priorities of organizations in the implementation of digital transformation in Portuguese organizations. To evaluate such objectives, a Project Based Learning (PBL) approach was used to reinforce the research and decision-making skills of undergraduate business students. Based on the results obtained, it can be concluded that organizations are aware of the need to accommodate the digital transformation not to fail and disappearing. However, it is not possible to conclude which strategy is to be adopted by the organizations, and how such a strategy will affect the organization as a whole, in particular as in respect of its business model.

1. Introduction

Over time, societies and economies have undergone complete transformations through the inclusion of new artifacts, namely the steam engine in the 18th century and railroads in the 19th century. Today digital technologies are having an impact on the transformation, entitled digital transformation (DT), of education, society and economy even deeper and more widespread than any other transformation that happened/occur in history. In order to better understand the impact that DT is having, data provided by the IDC study in 2017 shows that DT investment has tended to increase by 27% each year (2017–2020), and are projected to potentially reach around $6.3 trillion in 2020 [1]. It should be noted that, according to Westerman et al. [2], organizations that have managed to make a proper and successful DT are 26%more profitable than their non-digital competitors.

DT can be defined as a disruptive change of organizations supported by digital technologies [3]. As disruptive forces transform the different sectors of activity, many organizations are moving towards DT and embodying a more innovative mindset to thrive in this new era. Organizations who do not take advantage of this moment to evolve and transform themselves, are in danger of disappearing or being superseded by more agile organizations. In this sense, DT are also improving usability and accessibility in the educational context [4]. Technology is ever-present and allows for the incorporation and strengthening of new educational strategies, currently employed in new teaching frameworks in the last two decades [5].

DT supplies a plethora of competition, new business models, new organizational models and new services. For example, according to Chanias et al. [6], there are new business models, and existing ones need to be adapted because of digital interfaces. According to Loonam et al. [7] organizations wishing to use digital technologies to gain greater competitive advantage should also ensure that their respective business models are aligned with Information Systems (IS) which, by definition, include technologies. According to Westerman et al. [8] there are five types of reinvention of technology-driven business models: (i) reinventing the entire industry (e.g., the way AirBnB innovated in the hotel market); (ii) the replacement of products and services (e.g., Tesla has done this within the car industry, by replacing traditional cars driven by petroleum derivatives with electric cars); (iii) by creating new digital businesses with the development of new products and services (e.g., the evolution introduced by Nike+ with iPod and iPhone connections); (iv) reconfiguring value-added models, where products and services are reinvented in the value chain (e.g., Volvo reconfigured its business model to provide more direct services to its customers), and (v) rethinking value propositions (e.g., Tokio Marine Holdings has developed an app that can provide an insurance policy on the spot for skiing-, golf- and travel-related insurance).

Burberry, as discussed in Hansen and Sai [9], can be used as a quantifiable of DT’s positive experience. This organization digitally transformed its business in order to provide a perfect customer experience. This organization attributes its 30% growth during the 2008 sub-prime financial crisis largely to its Omni channel initiative, i.e., multi-channel integrated sales and marketing approach.

DT’s initiatives focus on leveraging greater customer engagement, delivering greater flexibility and agility to standardized and centralized operational processes, delivering new strategic opportunities to organizations, reconfiguring business models, creating new products and services, and in some cases, disrupting and reinventing value chains and industries [2].

As mentioned above, for DT to take place must be supported by digital technologies, and it is in this context that Uhl and Gollenia [10] argue that DT supports four technological pillars: (1) cloud computing, (2) mobile, (3) social and (4) big data-analytics. The most significant use of the pillars of DT has been driven by innovation accelerators, which include, among other solutions, IoT, robotics, 3D printing, artificial intelligence, augmented and virtual reality, cognitive systems and next generation (NextGen) security. To this extent, IDC expects that through 2021 innovation accelerator markets to grow by more than 18% [11]. However, it should be noted that the role of technology in DT, as emphasized above, goes beyond automation and optimization; technology contributes to helping organizations achieve competitive differentiation by creating additional value [12].

This article has as its main objective to evaluate and compare the current state of digital adoption in function of their preparation in relation to the prevailing technological categories including IoT, big data, social media, cloud computing, blockchain, augmented and virtual reality, among others, with future priorities of organizations in the implementation of DT, in Portuguese organizations. To achieve that, we have proposed a collaborative PBL exercise between different undergraduate management students, in order to assess their research skills, which are defined in their program. The exercise has a secondary objective: to assess the accessibility of the data that compose the state of digital adoption, by establishing a partnership with CIONET Portugal (https://www.cionet.com/cionet-portugal).

2. Background

Digital Transformation (DT) in recent years has emerged as a phenomenon that cannot be ignored by society in general, or by organizations in particular. DT encompasses profound changes occurring in society and in organizations supported by digital technologies [13]. At the organizational level, it is argued that organizations must find ways to innovate with these technologies and develop, according to Hess et al. [14], “strategies that embrace the implications of digital transformation and drive better operational performance”. In this section, we intend to introduce the topics of DT, organizational agility and organizational awareness, pivotal concepts of the research here developed.

2.1. Digital Transformation

Recent literature has contributed to a better understanding of what DT is, evidencing that it is broad and transversal to some areas of knowledge, namely: behavioral (behavior of clients or employees); organizational (types of organizations) and information systems (strategies and alignment of information systems). According to the knowledge on IT-enabled transformation, the literature shows that technology itself is only part of a complex puzzle that has to be solved in order for organizations to stay competitive in the digital age. However, according to Hausberg et al. [15], there is currently no consensual definition that provides a comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon, as well as its implications at various levels of analysis.

Although there is no formal definition of DT, some authors [16,17,18] establish the workable bases that are part of definitions that are already accepted. Thus, Oestreicher-Singer and Zalmanson [16] defined Digital Transformation as “the ongoing process of changing the existing companies to carry out their businesses”. Later Lucas et al. [17], defined DT as the “transformation precipitated by transformational information technology”, more focused on technology. Finally, Gruman [18] defines DT as “the application of digital technologies to fundamentally impact all aspects of business and society”.

It should also be noted that, in the context of what is, and how to implement DT, Loonam et al. [7] present a framework of interest for the management of TD implementation. The proposal can be seen from two organizational perspectives: vertical perspective-operational and strategic; horizontal perspective: internally focused and externally focused. In the strategic perspective, the key points are: strategy (business model innovation) and organization. This means that the organization must have a clear vision of the intended business model and respective innovations as well as the technologies to be used/implemented in the sense of there is an alignment to the DT, which the organization proposes to achieve. On the other hand, DT cannot be seen only as a technological solution, but rather as a solution that also focuses on the business perspective. In the Operational Perspective, the key points are customers and technology. From this perspective the focus is on the customer, i.e., on meeting their needs and expectations, as well as on the inclusion of processes that allow the maintenance of existing customers and the garnering of new ones. As for horizontal vision, the Internal and External perspectives focus on the integration of technologies in order to allow the technologies to communicate with each other. Example of application, when the combination of operational perspective with externally focused is analyzed from customers’ point of view, the authors suggest, “Blending the physical and digital customer experience.” [18]

Goerzig and Bauernhansl [19] have studied the lower abstraction level of the framework developed by Loonam et al. [7], present a comparison between the enterprise architecture (EA) tools and the challenges of DT deployment. According to this comparison, for instance, when the feature used is driver, the EA has IT-focus and DT has business-focus, or if the feature is development approach, the EA has a waterfall approach, and DT has agile approaches. From the analysis of the above mentioned, it can easily be verified that traditional EA is not focused on transformation and that new tools are needed in order to contribute to the implementation and management of DT in organizations.

As mentioned above, DT is supported by four technological pillars: mobile, cloud computing, big data, and social media. However, there are other technologies, called innovation accelerators that act as DT drivers. As example of innovation accelerators have been previously referred to as IoT, robotics, 3D printing, artificial intelligence, augmented and virtual reality, cognitive systems and next generation (NextGen), security and blockchain. Nonetheless, as asserted by Lusch and Nambisan [20], such technologies cannot be used without careful consideration toward the organization’s needs and strategy.

2.2. Organizational Agility

With an increasingly digital world, organizations are being confronted with DT’s “impositions” —demanding customers, the economy of ever more dynamic markets, and technologies emerging at an uncontrollable speed—forcing organizations to work towards becomingmore agile to respond to such challenges [21].

Organizational agility is defined in the Business Dictionary (http://www.businessdictionary.com/) as “the capability of an organization to rapidly change or adapt in response to changes in the market.”

The so-called “traditional” organizations are typically hierarchical, and static, where goals and decisions flow through the hierarchy, with leadership at the top of that hierarchy. These organizations work using linear planning and control. The “skeleton” structure of the traditional organization is strong, but often rigid and slow. On the other hand, an agile organization is a network of teams with a people-centered culture. This type of organization is characterized by the existence of rapid cycles of learning and decision, enabled by technologies, guided by a strong common purpose to co-create value for all the stakeholders. The agile organization has the ability to quickly adapt to new challenges, i.e., it has a competitive advantage that translates into creating value in a stable way. An agile organization is both stable and dynamic [22,23]. Thus agile organizations, unlike traditional organizations, mobilize quickly. By analogy, and according to Aghina et al. [22], an “agile organization is a living organism” (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Traditional organization vs agile organization (adapted from [22]).

In a nutshell it can be said that a high degree of organizational agility contributes to a positive reaction, i.e., to success in the face of external “demands” such as new competitors, changes in market conditions, and the emergence of new technologies that can change how business is conducted. These changes can be analyzed through the characteristics of agility types (Customer, partnering, operational) [23,24]. In the case of the first, the technology can be used to build, enhance and maintain customers for the design, and testing of new products. The second characteristic of agility, Partnering, technology, will facilitate collaboration between organizations across collaborative platforms, etc. Finally, from the operational perspective, technology will allow the modularization and integration of processes.

In this context, and taking into account what has been presented in Section 2.1, it can be said that the commitment of an organization to DT should be undertaken in order to simplify a business and its agility. The introduction of digital technologies into the organization alone will hardly result in a successful transformation. An organization that wishes to transform itself into the logic of simply incorporating new technology will not achieve the desired/expected effects; the organization should primarily assess how each of its organizational sub-systems can improve their agility before making it the cornerstone of a DT plan [25].

In the age of the digital customer, and in the global business landscape, DT becomes one of the most viable strategies to accelerate business activities, processes, business growth, and fully leverage available opportunities. Most organizations are going through some degree of DT, however, simply adding better technologies is not, by itself, the “game changer” as demonstrated.

2.3. Organizational Awareness

The definition and implementation of a digital transformation strategy (DTS) has become a fundamental concern for many pre-digital organizations, given the transformative impact of digital technologies in an organization’s internal and external environment. Pre-digital organizations are established organizations that belong to the so-called traditional organizations (retail, healthcare, automobile industry or financial services) that were financially successful in the pre-digital economy but for which the digital economy poses a threat. Therefore, unlike digital-born organizations (Amazon (Seattle, WA, USA), Netflix (Los Gatos, CA, USA) or Uber (San Francisco, CA, USA)), pre-digital organizations often have to change the whole organization, namely the business model and processes when adopting digital technologies. However, many organizations fail to digitalize because they never consider the implications of their business model. In most digitalization, it means doing things as before, only digitally and not envisioning changes, i.e., defining a transformation strategy. This strategy is based on the one hand, the objectives that the organization intends to achieve, and on the other hand, on the study of the internal implications for the organization as a whole.

According to Hess et al. [14], digital technologies can transform the products, services, business models and operations of an organization and the competitive environment in which the organization positions itself, as well as its vision/relationship with employees, both at a structural level and at the communicational level [26]. Thus, an organization that proposes to carry out a DT, will be subject to change in its organizational structure, which is why it has to define the person in charge of DT. In addition, it must also assess and define whether new digitally supported operations should be integrated into existing organizational structures or whether they will be allocated to independent entities. Parallel to what has been presented, the organization must define whether it needs to acquire specialized know-how and/or new skills. In this context, and for the reasons given, new professions emerge to meet the specific requirements of DT in an organization, namely the Chief Digital Officer (CDO) [26].

According to Singh and Hess [27], the responsibilities of a Chief Information Officer (CIO) are the management, operationalization of IT infrastructure and the evolution of platforms. However, DT goes beyond resource digitization, resulting in value and revenue created from digital assets. Moreover, according to Singh and Hess [27], digital technologies “demand different mindsets and skill sets than previous waves of transformative technology”. As a result, in many organizations, CIOs are not the right people to take on DT in their organization, and so many organizations are creating a new leadership position—Chief Digital Officer (CDO). The CDO function can be centralized at the group level or decentralized at the subsidiary level. Regardless of their positioning, CDOs are hired to make DT a strategic priority in organizations. Thus, it is possible to gauge that an organization may have different management functions related to technologies. According to Singh and Hess [27], a CDO has the following competencies and skills: (1) Key responsibilities-(a) Digital mobilization of the whole company, (b) Initiation of digital initiatives and, (c) companywide collaboration; (2) Strategic perspective (Digital Transformation Strategy) and (3) Specialist Role (Digital Transformation Specialist). These same authors also defend that, a CDO should have the following skills and competencies: (1) Entrepreneur; (2) Digital Evangelist; and (3) Coordinator—Change Management skills.

In addition to the specific competencies already outlined, a CDO must have two competencies that are not specific to its function—IT competences and Resilience. IT competences are required for a CDO to formulate IT requirements (required by DT) and iteratively develop new digital products and services in collaboration with the CIO. Resilience is needed to deal with problems related to DT, namely responding to critical/unexpected situations that may occur and/or being able to take action to minimize problems that occur.

As already mentioned DT is successful, or fails, due to people and rather than technology. According to Singh [28], an organization that wants full DT has to undertake a reconfiguration of resources, talent management and even cultural change [29]. It is within this ambit that internal communication and collaborative work is framed. The study presented confirms that an ad hoc transformation by organizations, that is, without the definition of a digital transformation implementation strategy, and the behavior of the organization’s actors, is counterproductive leading to failure and even endangering the organization itself, as attested to by McKinsey [30].

Internal communication has two functions, on the one hand providing information and, on the other hand, creating community awareness within organizations. In this respect, the creation of community awareness, through communication, allows establishing relationships between the organization, supervisors and employees. Internal communication is thus an underlying influence of employee engagement. According to Karanges et al. [26], engagement translates into benefits for the organization in general, namely a positive, rewarding and work-related mood, and for employees, such as increased productivity, decreased conflict, and improved image and reputation of the organization. Thus internal communication creates working relationships based on meaning and value.

By definition, the working collaborative is the act of two or more people or organizations working together for a purpose (Cambridge dictionary (https://dictionary.cambridge.org/)). According to Patel et al. [31], a critical success factor for any community, both within and outside the work professional environment, is the extent to which that same community can coordinate to communicate and achieve common goals, i.e., collaborate. The collaborative work thus allows the organizations that drive it to create synergies between departments or with supply chain partners, making better use of their resources and knowledge and consequently obtaining, among others, cost reduction, and better decision-making. In this context, DT brings opportunities and challenges by providing more agile ways of working. With DT, work tends to be more focused on collaboration. The combination of different points of view, and the creation of a shared understanding between the different stakeholders/employees, are the foundation of creative collaborative work and give rise to new insights, ideas and artifacts. Finally, collaborative work can stimulate individual creativity because of the unique perspectives with which each individual contributes to problem solving [32].

3. State of the Art

To standardize the procedure, we need to take into account that the literature in the area of DT since 2016 is vast. For the construction of the state of the art, the B-on portal (www.b-on.pt) was used, which is an Online Library of Knowledge that provides unlimited and permanent access to thousands of international scientific journals and e-books. The research was carried out for the period of 2016–2018 with the following queries search: (i) “(Digital AND Transformation AND Portugal)”; (ii) “(DIGITAL AND TRANSFORMATION AND Portugal)”; and (iii) “(Digital AND Transformation AND PORTUGAL)”. The results obtained indicate a near absence of studies presenting which direction DT is having within Portuguese organizations. There are only two scientific papers [33,34], the first one surveys the relationships between the enablers of DT, while the second presents a benchmark of DT best practices in the tourism industry. None of the papers include a survey of the digital transformation in Portuguese organizations, independently of the activity area. In order to ensure that there are already studies performed when the search query is “(Digital AND Transformation)”, a search was conducted which detected that there were already 4250 entries, even though most of them are not directly related to the entire search query. In the more generic field of study of our proposal, we can also find previous work carried out in different countries and with very different approaches [35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49]. The works as mentioned, address proposals focused on the field of study using a wide variety of tools and methods, and open options to evaluate how they could be introduced and what scope they have in the field of study. However, based on the requirements, needs and design of our experiment, it was possible to conclude that there are no studies on digital transformation in Portuguese organizations, so a first exploratory work is addressed. This work is concerned with identifying whether in the next iteration is better to follow our proposal or replicate any of those identified in other regional or cultural areas according to references cited.

4. Research Methodology

The purpose of this section is to describe the procedures used to collect data that are the basis of this research. The main feature of the scientific method is organized research, strict control of the use of observations and theoretical knowledge. For the present study, we used quantitative research methodology, since it is more appropriate to determine the opinions of the respondents based on structured questionnaires.

We have proposed an activity to the students of degree in Management of Business-Technology, and Digital Business Design and Innovation degree (both with a duration of eight semesters, four academic years). Both type of students during their formation must understand the importance of technology, and how to manage it, if they wish to pursue new opportunities. After a first course receiving generic content, in second and following academic years they move around the class, debating, helping their classmates, and, above all, applying the course content to their projects (PBL). They work in multi-disciplinary teams, side by side with organizations to overcome challenges, and knowing the necessities to be addressed, as for example in our case study. This activity was supported by a CIONET which ensured, on the one hand, the business perspective and practical application and, on the other hand, the adaptation of the questionnaire due to compliance issues. The basic concepts needed for our proposal, are explained in the subjects of Business Communication Skills I (four credits in the 1st semester), Principles of Business Management (six credits in the 1st semester), Macroeconomics (four credits in the 2nd semester), Management Information Technologies and Systems (four credits in the 3rd semester), Marketing Management (four credits in the 3rd semester), and Methods of Decision Analysis (four credits in the 4th semester). The objective was that they could propose an adaptation of the questions based on brief discussion about its topics and implications, with the possibility that other students could to improve any individual input.

The study was based on an online questionnaire with the title “Digital Transformation (DT) in Portugal”. Before being available online, the questionnaire was subjected to an evaluation of six experts in the field, academics and CIOs. CIONET, in conjunction with an institution of higher education, ensured the dissemination of this questionnaire to organizations.

The final questionnaire was online for 60 days and 77 valid responses were received. The data collected were pooled and treated by using the IBM SPSS Statistics 24.0 software and Microsoft Excel 2016.

The questionnaire consists of three parts which include: “Organization characterization” (Part 1, with four questions), “Organization characterization regarding Digital Transformation, at present” (Part 2, with nine questions), and “Organizational future regarding Digital Transformation” (Part 3, with two questions).

The statistical analyses used for the data analysis [50,51] were Descriptive Analysis (frequency analysis, descriptive statistics and graphical representations), Inferential Analysis (Spearman’s ordinal correlation, Kruskall-Wallis nonparametric test and Wilcoxon nonparametric test for paired samples) and Multivariate Analysis (Categorical Principal Components Analysis (CATPCA) including Reliability Analysis (Cronbach’s Alpha) and Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA)).

Spearman’s correlation was used to study the relationship between variables measure on an ordinal scale. Thus, given the ordinal nature of the variables and, with the objective of evaluating differences between them we applied nonparametric tests (because the condition of the normality is not verified). Kruskall-Wallis and Wilcoxon methods are examples of application of these tests.

Categorical Principal Components Analysis (CATPCA) was used to transform correlated variables in a small set of independent variables. This is the appropriate alternative technique to Principal Component Analysis (PCA) when variables are not quantitative. In order to determine the structural relationships that link factors to variables, the appropriate multivariate technique was Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA).

According to the two most widely adopted approaches (power analysis [52] and rules of thumb [53]) for estimating the sample size, it can be considered that the sample size used is sufficient for this study. For example, for the Spearman correlation coefficient, with a sample size of 77, we found a power value of 0.999996. For the multivariate techniques, we use rules of thumb. For example, for EFA, the sample size used verifies the condition of being between 5 k and 10 k, where k is the number of variables.

5. Analysis and Discussion of the Results

The characterization of the organization (Part 1 of the questionnaire) is very succinct given the limitation imposed by the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). As a result of the four questions in this section relating to the characterization of the organization, we only had access to the answers to two of them’: A2 (“What role do you play in the organization?”) and A4 (“What is the general feeling of your organization when it comes to technological disruption?”).

In relation to the role that the respondents play in the organization (question A2) to highlight the high percentage of senior executive/manager (54.6%) as well as 15.6% of CIO. Question A4 (“What is the general feeling of your organization when it comes to technological disruption?”), for which they can chose one of four options, we find that the most chosen option was “Provides new opportunities to improve business” (61%), the other options being of little relevance “Helps in the conquest of new markets” (18.2%) and “Represents a threat to the survival of the organization” (6.5%). Finally, we should point out, the worrisome percentage (14.3%), for the option that states, “Eventually the organization will adapt”.

In Part 2 “Organization characterization regarding digital transformation, at present” we have nine questions (B1 to B9). The first three questions, B1 (“The organization has explored how Digital Transformation impacts suppliers, distributors and other partners”), B2 (“The organization’s leadership has considered the costs, savings and return on investment associated with Digital Transformation”) and B3 (“The organization has, a plan, or strategy, to implement Digital Transformation”) use a five-point Likert scale ranging from: “Strongly disagree” (1) to “Strongly Agree” (5). We found that the percentage of respondents who agree/strongly agree on all these issues varies between 62% and 69%, a result that is expected in some way, taking into account the leadership functions performed by the respondents in their respective organizations. It should also be pointed out that around 20% of responses are neutral.

Given the high percentage of respondents who said they agreed with questions B1 and B3, we found it of interest to assess how well those views were aligned. For this, we calculated the Spearman’s ordinal correlation, having obtained a strong positive correlation (rs = 0.631) and significant at 0.01 level, which reveals that those who most agree that the organization has explored how DT impacts suppliers’ distributors and other partners are also those who most agree that the organization has, a plan, or strategy, to implement DT.

Questions B4 (“What is the most important goal of the Digital Transformation strategy in your organization?”), B5 (“Who leads the Digital Transformation initiative in your organization?”), B6 (“What are the main factors that currently help your organization implement Digital Transformation?”) and B7 (“What are the biggest obstacles that prevent your organization from implementing Digital Transformation?”) are on a nominal scale and the respondents could choose one or more options.

In relation to question B4, according to the role that the respondent play in the organization, the main conclusions were: for CEOs and Senior managers the most important goal of DT’s strategy is “Modernize legacy IT Systems/processes and reduce costs” (60% and 47.6% respectively); for CIO’s and Senior executive, the goal most pointed out to was reach and engage with customers more effectively (50% and 64.7% respectively). Finally, the high percentage (66.7%) attributed by the General Manager to the “Achieve better visibility to the business and increasing the income” goal should be highlighted.

Although there are organizations in which the new role of CDO begins to emerge at the level of the organization’s management, in the sample of Portuguese organizations under study, no respondents with this role were found.

When questioned regarding the main factors that help (_h) implementation of DT (question B6), the “Leadership Vision” (Leadership_h) factor pointed out by 64.9% of the organizations, stands out significantly. It can also highlight the “Culture of the organization” (Culture_h) (48.1%) and the “Technological partners” (Tec_partners_h) (40.3%) as relevant indicators. The low result (27.3%), which was surprising to us, regarding the indicator “Collaborators with knowledge” (Competences_h) it should also be mentioned.

The most referenced obstacles (_o) that prevent organization from implement DT (question B7), with approximately equal percentages are the, “Culture of the organization” (Culture_o) and “Inadequate budgets” (Budget_o) with the values, 42.9% and 40.3%, respectively.

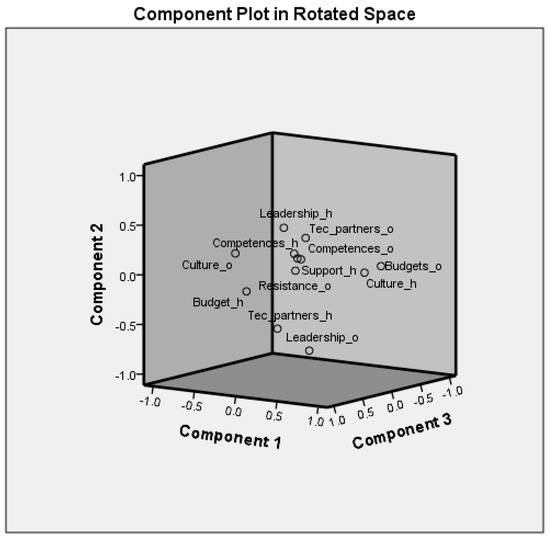

In view of these results, it is important to discover and analyze, in respect of these interrelated questions (B6 and B7) which indicators/obstacles (variables) that facilitate or disrupt DT implementation. For this and using exploratory technique EFA to determine the structural relationships that link the factors to the variables, we apply the principal components method followed by a Varimax rotation for extraction (the one that produced a more interpretable solution). This analysis produced scores that summarize the information present in the multiple indicators/obstacles in a reduced number of factors. Table 1 presents the factorial weights of each indicator/obstacle in the 3 retained factors (Kaiser’s criterion and Scree plot criteria). Factorial weights higher than 0.4 in absolute value are highlighted in bold.

Table 1.

Features Rotated component matrix.

The first factor has high factorial weights in “Culture_h”, “Culture_o”, and “Budgets_o”. The second factor has high factorial weights in “Tec_partners_h”, “Leadership_h”, and “Leadership_o”. Finally, the third factor has a high factorial weight in “Budget_h” and moderate in “Budgets_o”. Thus, the first factor can be designated as “Culture of the organization”, the ‘second’ as “Vision of leadership” and, finally, the third factor can be called “Budget”.

Table 1 and Figure 2 together allow us to obtain in detail the conclusions that follow. In Factor 1 (“Culture of the organization”), culture of the organization is a very important indicator to implement the DT in the organization and its shortage works as one of the biggest obstacles that prevent the organization from implementing DT. In this factor, it is also worth noting, the important weight of the inadequate budget as an obstacle. In Factor 2 (“Leadership Vision”), refers to being confused about what to do is a more significant obstacle to implementing the DT in the organization than a strong vision of leadership. On the other hand, respondents who think it is more important to have a vision of leadership as an aid to the implementation of DT, are the ones that least value the existence of technological partners. Finally, Factor 3 (“Budget”) shows that for the respondents, it is very important for the organization to have an adequate budget, as support in the implementation of the DT. Interestingly, the shortage of budget, although relevant, does not have as much weight when considered as an obstacle.

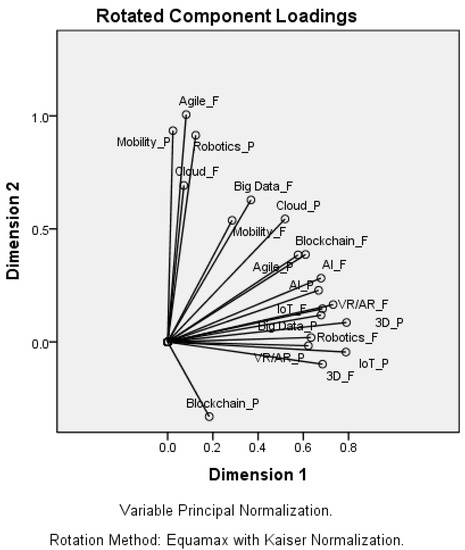

Figure 2.

Component plot in the rotated space.

For questions B8 (“Evaluate the state of the organization’s current digital adoption for the following technology categories”) and B9 (“Classify the various departments of the organization based on their ability to adapt to technological change”) the respondents must classify ten technological categories (categories 1–10) and nine departments within a specific ordinal scale. Therefore, in question B8, the scale used for each of the categories was: (1) “Nothing prepared”, (2) “Unprepared”, (3) “Prepared”, (4) “Fully prepared” and (N/A) “Not applicable”, and for question B9 the following scale was used for each department of the organization: (1) “Not agile”, (2) “Not very agile”, (3) “Agile”, (4) “Extremely agile” and (N/A) “Not applicable”.

Thus, starting with a detailed analysis of the answers obtained for question B8, it is worth noting the large number of respondents who pointed out that “Blockchain” and “IoT Technology/Sensors” are technological categories that are not yet applied in their organization (N/A) (“Not Applicable”).

It should be noted that these categories are examples of innovation accelerators (see Section 2.2) and they should not be used without careful analysis of the organization’s needs and strategy, such constraints mean that most Portuguese organizations still do not apply them.

In relation to categories with which the organizations have a greater degree of preparation, it has been verified that the one for which the organizations are more prepared are the 4 pillars of DT (“Agile Collaboration Tools” (category 8), “Mobility” (category 1), “Cloud Solutions” (category 2), and “Big Data & Analytics” (category 3) and also the categories “Robotics/Automation” (category 7) and “Virtual reality/Augmented reality” (category 6).

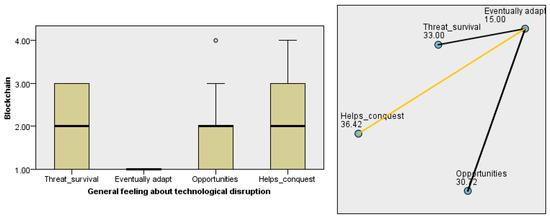

In order to evaluate if the general feeling of the organization when it comes to technological disruption (question A4) had a significant influence on the opinion of the degree of preparation of the current digital adoption in relation to the ten technological categories (question B8), we used Kruskal-Wallis’s non-parametric test for each of the categories. According to the results obtained, we conclude that question A4 only has a significant influence on the opinion of the respondents regarding the degree of preparation of “Blockchain” (category 10), as shown in Table 2 (p-value (Sig.) = 2.3% <5%).

Table 2.

Results of Kruskal-Wallis test.

However, the Kruskal-Wallis test does not indicate which of the feelings (question A4) had a significant effect on the respondents’ opinion of the degree of preparation in category 10. Therefore, to perform this identification process proceeded on to multiple comparison of the order using the Dunn test statistic [46,47]. Using the unadjusted asymptotic p-value (Sig.) (Table 3), we can conclude that the significant differences occur between the general feeling “Eventually the organization will adapt” and “Helps in the conquest of new markets” and between “Eventually the organization will adapt” and “Provides new opportunities to improve business” (p-value = 0.3% and 1, 2%, respectively).

Table 3.

Results of Dunn’s test.

Moreover, observing Figure 3, we can also conclude that all the respondents who expressed as a general feeling of the organization “Eventually the organization will adapt” as an option, present as to the degree of preparation of the category “Blockchain”, distribution significantly different from the others that affirmed there is another feeling. It should also be noted that in this option all organizations are unprepared. We also found, as revealed in Figure 4, that the options in question A4 that most influenced the evaluation of the respondents regarding the degree of preparation of the “Blockchain” are “Eventually the organization will adapt” and “Helps in the conquest of new markets” (boxplot and yellow line).

Figure 3.

Boxplot and pairwise comparisons of “Blockchain” for “General feeling…” (A4).

Figure 4.

Position of the original departments after CATPCA, in the two retained dimensions.

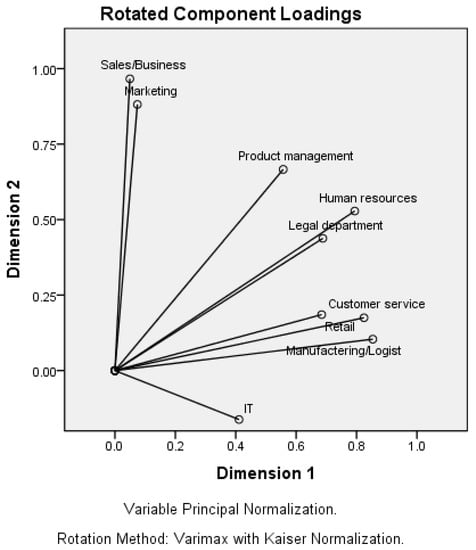

Regarding the most relevant results associated with question B9—Part 2 of the questionnaire—these were: 58% of respondents indicated that this question does not apply to the “Retail” department; the departments that have a greater degree of agility in the adaptation to technological change are “IT”, followed by “Marketing”.

In order to summarize the information presented in question B9, we use the CATPCA with the Varimax rotation method (the one that produced a more interpretable solution) and Kaiser Normalization [50,51]. For component retention we use the rule of eigenvalue greater than 1 and percentage of explained variance higher than 70%. The internal consistency of the two components/dimensions (Table 4) was measured with Cronbach’s Alpha [51] (0.813 and 0.743, which shows a good internal consistency).

Table 4.

Model summary rotation.

Table 5 shows that the most agile departments in their ability to adapt to technological change (departments that are strongly related related to Dimension 1) are “Manufacturing/Logistics”, “Customer Service” and “Human Resources”. Departments of “Marketing” and “Sales/Business” are very strongly associated with Dimension 2 (second major component). Additionally, despite the lower relevance, we can state that the “Legal” and “IT” departments are correlated with Dimension 1. Finally, it should be noted that the weights obtained for the “Product management” department in both dimensions reflect the fact that the department’s ability to adapt to technological changes is explained simultaneously by both. Thus, we can conclude that Dimension 1 is the “Product/Customer” component and Dimension 2 is the “Marketing/Sales” component.

Table 5.

Principal components extracted from CATPCA.

Combining the analysis of Table 5 with observation of Figure 4, we can also distinguish four groups within organizations according to their adaptability (greater or less agility in adaptation) to the technological changes of the various departments of the organization: Business Group (Sales/Business and Marketing), Personal Group (Human resources and Legal department), Customer Group (Manufacturing/Logistics and Customer service) and Technological Group (IT).

In order to evaluate the future of the organization in relation to DT (“Organization future regarding Digital Transformation”—Part 3), given the accelerated pace of technological change, we began by investigating the organization’s adaptability over the next three years (Question C1). With the results obtained, we conclude that the majority (66.2%) of respondents think that their organizations are capable or very capable of implementing adequate adaptation, although a significant segment of 27.3% of the respondents think that their organizations are incapable or quite incapable.

For question C2 (“Evaluate (next 12–18 months) the priorities in the implementation of DT in the organization”), for the same technology categories of question B8, the respondents must classify the ten technologies within the following scale ranging: “No priority” (1), “Low priority” (2), “Strong priority” (3), “Total priority” (4) and (N/A) “Not applicable”.

The technological category that the respondents pointed out more frequently as a response to “Not applicable (N/A)” is “3D printing”. In relation to technological categories that the respondents of organizations evaluate as high priority to the implementation of DT in their organization, we conclude that these are the 4 pillars of DT (“Agile Collaboration Tools”, “Mobility”, “Cloud Solutions” and “Big Data & Analytics”).

Finally, with the objective of evaluating and comparing the current state of digital adoption in respect of the preparation of these in relation to the prevailing technological categories, with the future priorities of the organizations in the implementation of DT in Portuguese organizations we started by comparing the importance of technological categories, both in Present and in the Future (Questions B8 and C2). For this purpose, we applied the CATPCA with Equamax rotation (Table 6 and Figure 5) and also the graphical representation of the average degrees assigned to each of the technological categories, in the present and the future (Figure 6), as this was the descriptive measure which was more discriminating in the comparison of categories. Table 6 and Figure 5 show that the technological categories most closely related to Dimension 1 are:

Table 6.

Principal components extracted from CATPCA.

Figure 5.

Position of the original variables (B8 and C2) after CATPCA in the two retained dimensions.

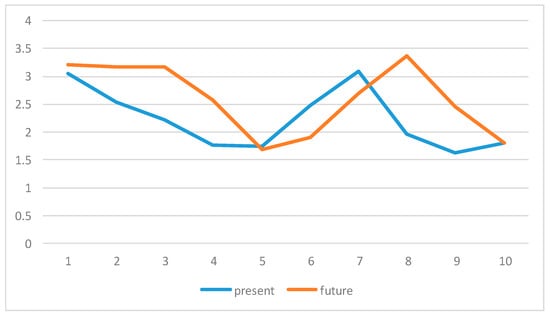

Figure 6.

State of adoption (present)/priority (future) in implementation of the ten technology categories (1-Mobility, 2-Cloud solutions, 3-Big Data Analytics, 4-IoT/Sensors, 5-3D printing, 6-VR/AR, 7-Robotics/Automation, 8-AI, 9-Agile tools and 10-Blockchain).

- In the present (P): “IoT/Sensors”, “3D printing”, “Big Data/Analytics”, “AI”, “VR/AR” and “Agile tools”.

- In the future (F): “VR/AR”, “3D printing”, “IoT/Sensors”, “AI”, “Robotics/Automation” and “Blockchain”.

For Dimension 2 they are:

- In the present (P): “Mobility”, “Robotics/Automation” and “Cloud Solutions”.

- In the future (F): “Agile tools”, “Cloud Solutions”, “Big Data/Analytics” and “Mobility”.

It should also be noted that in Dimension 2, the “Blockchain” technological category in the Present, although with a moderate weight in this dimension and negative, is in contrast to the “Mobility”, “Robotics/Automation” and “Cloud Solutions” categories with positive weights.

Figure 6 shows the evolution of the results for the ten technological categories in present and future.

Associating the information from Table 6 with Figure 5 and Figure 6, we can state that, in Dimension 1, the technological categories identified as preponderant in the Present are those that the respondents consider to be less prepared in their organizations. On the other hand, the technological categories identified as predominant in the Future, in this dimension, are those considered by them as less important than for the implementation of DT. Regarding Dimension 2, we verified that the technological categories with the greatest weight in the dimension were those that the respondents pointed out as being the best prepared categories in their organization regarding digital adoption in the Present. In the opinion of the respondents regarding the degree of priority of implementation in the Future, it was verified that the technological categories with greater weight, in this dimension, are those evaluated by them as being of priority.

More explicitly, we can conclude that, in relation to the technological categories that constitute the four pillars of DT (categories 1, 2, 3 and 8), the respondents evaluated their organizations as:

- well prepared in relation to digital adoption in the Present for all categories, except for the “Agile tools” category (only with moderate preparation—category 8);

- the categories are all priorities in relation to the implementation of DT in the Future, with particular relevance in the “Agile tools” category where the largest increase occurred.

Finally, there was a significant decrease in the degree of priority in the future implementation of “Robotics”, “VR/AR” and “3D printing” categories.

Summarizing, Dimension 1 can be designated by the technological categories with “Less preparation (P)/priority (F)” and Dimension 2 by “Greater preparation (P)/priority (F)”.

In order to verify if there are significant differences in the organizations’ evaluations, before and after (P/F), for each of the technological categories, we used Wilcoxon nonparametric tests (suitable for paired samples). We found that, in the “Mobility”, “3D printing” and “Blockchain” categories (categories 1, 5 and 10), there were no significant differences (p-values > 0.5) in the evaluations of organizations in Present and Future, conclusions which confirm the previous exploratory analysis.

6. Research Limitations

In the present research, a comparative evaluation of the current adoption and future priorities was carried out, in relation to the technological pillars and the accelerators of transformation and digital innovation in Portuguese organizations using an approach of a pre-designed collaborative PBL exercise to select the main indicators to evaluate, with the with the eventual collaboration of 15 undergraduate management students. The present research work is relevant since there are no significant inputs of this nature and scope in the existing literature.

As the area we are exploring is relatively unexplored territory, this research has encountered some limitations. The first concerns the number of responses obtained: although the study was released in a large number of organizations (CIONET’s online survey), the number of responses obtained was relatively low. Even though this limitation conditions, in a certain way, the generalization of our results, the data gathered is sufficient (see Section 4) to reach the objectives proposed in this work. Furthermore, the need to define research avenues has been identified, to define future research lines that can use the results already obtained and continue the research in DT in its various aspects.

Second, given the legal constrictions imposed by the GPRD, it was not possible to define and analyze the results by business domain or by size of the organization. These two limitations may generate some bias in the analysis and in the overall discussion of the results obtained.

Third, the literature shows that DT is a very active research area and focuses on several areas of knowledge, namely the Behavioral and Information Systems areas. This means that investigation should also be extended to those fields of scientific knowledge.

The global results obtained are good in general, but not realistic. In comparison with previous international studies, for example Kane et al. [25], affirm that: “only the 15% of responses obtained from companies at the early stages in processes of DT, affirms that their organizations have a clear and coherent digital strategy”. Spremic [54], suggest that IT governance should be strategically focused in the organizations for a successful DT development, and for their implementation, companies should rely on skillful employees, as for example talent management, or systematically raising people’s competences with a continuous learning. Similar findings were identified by Reis et al. [55], who affirm that managers should adapt their business strategy to a new digital reality, something that also affects the scholars, who are also facing changes, as prior research may not have identified all the opportunities and challenges of DT.

Our paper is one-step more in a currently widely strategy for identifying and compare the critical success factors in the DT and business strategy. Holotiuk and Beimborn [56] work with a Digital Business Strategy framework (DBS), based on a structured review of 21 industry reports. From their analysis, they yield eight generic dimensions with 40 critical success factors, also called CSFs. This approach can be complementary to our study, and in a future extended study a possible system to use and compare. Libert, Beck and Wind [57], present seven questions to ask before a new DT. In front of the assumption that the companies have about their preparation for DT, they have estimated that DT have a failures range from 66% to 84%. In addition, their proposal can be adapted in a future study incorporating their questions in a more complex survey to identify the real state of the DT in organizations.

From an educational perspective, our approach helped the students to identify the main types of data that can support their learning and support making decision systems. Extracting information from data to ultimately turn it into knowledge can contribute to drawing a complete picture of student learning which can empower them in their professional future, as well as stakeholders and policymakers who study such contexts. The project gave the students valuable date to follow an improve different subjects and educate them on the management of tools available to gather, organize, visualize, and analyze these data as well as methods for improving its accessibility, availability, usability, and understanding.

Finally, our objective of assessing the current position and future perspectives of the Portuguese organizations regarding DT was used a broader approach rather than an in-depth approach. Meaning that the complexity of the relations that should be studied in future research target on the subject and thus the specific relationships that emerge from the analysis will be deepened, both at the national level and in the international context.

7. Conclusions

Digital Transformation is becoming, more and more a common expression, due to its relevance to the life of organizations. DT, as discussed, may be considered essential for organizations to be competitive. However, this transformation cannot be undertaken through an ad hoc process but by a strategically defined and planned process as its results an impact throughout the organization, from processes and activities to business models. Organizations that do not adopt DT may disappear from the market. In order to understand the perception of Portuguese organizations regarding the adoption of DT, our team created a questionnaire.

The results presented and discussed in Section 5, have shown a set of important findings that contribute to the understanding of the present and future position of the Portuguese organizations with regard to DT. Regarding the general feeling of the organization when it comes to technological disruption, we found that the most chosen option was “Provides new opportunities to improve business”. The results obtained are in line with the study presented in [49], where 29 European countries are analyzed, which show that “… the feedback effects of the process are also worth considering, since the niche markets generated, greater competition, access to new markets, etc., all motivate entrepreneurs to introduce more innovations and corresponding digital transformations.”

In addition, we found that over 60% of respondents agree/strongly agree that their organizations: (i) explore how DT impacts suppliers, distributors and other partners, (ii) considered the costs, savings and return on investment associated with DT and that (iii) the organization has a plan, or strategy, to implement DT. We also conclude that the respondents that most agree that the organization has explored how DT impacts suppliers’ distributors and other partners are those who most agree that organization has, a plan or strategy, to implement DT. These results allowed us to have a perception of DT in Portugal, similar to those presented in [35] related to a study applied in South Africa.

Related to indicators/obstacles that help or disrupt DT implementation, “Culture of the organization” is a very important indicator to implement the DT in the organization and its shortage works as one of the biggest obstacles that prevent the organization from implementing DT. Another factor (indicator) considered fundamental for digital transformation is “Leadership vision” (64%). This finding is reinforced by [47] indicating that “… effective governance has been considered by some researchers as a critical lever for organizations to drive successful digital transformation.”

When organisational leadership is unsure how to proceed this presents a more significant obstacle to implementing the DT in the organization than a strong leadership vision. On the other hand, respondents who think it is more important to have a vision of leadership as an aid to the implementation of DT, are the ones that least value the existence of technological partners. For the respondents, it is very important for the organization to have an adequate budget, as support in the implementation of the DT. It can also highlight the “Technological partners” as relevant factor that help DT implementation. The results obtained are in agreement with the study presented in [35], since the authors concluded that “The high number of factors identified by the participants suggested that organizational factors were dominant in their opinion when considering the adoption of digital transformation…”.

In respect of the departments with the highest degree of agility in the adaptation to technological change, the most chosen was “IT” followed by “Marketing”. Technological categories which the organizations point out as having a great degree of preparation were the 4 pillars of DT (“Agile Collaboration Tools” (category 8), “Mobility” (category 1), “Cloud Solutions” (category 2), and “Big Data & Analytics” (category 3)), “Robotics/Automation” (category 7) and “Virtual reality/Augmented reality” (category 6). Moreover, for these technological categories, organizations have been evaluated as well-prepared for all of them, with the exception of the “Agile tools” category. However, they are all a priority in the future with special emphasis (associated with the greatest increase) precisely in the “Agile tools” category. In the “Robotics”, “VR/AR” and “3D printing” categories there has been a decrease in the level of priority concerning future implementation. Finally, regarding technological categories, it should be noted that there are no significant differences in the present and future evaluations for the categories “Mobility”, “3D printing” and “Blockchain”. It should also be noted that the results obtained in the study are in agreement with those presented in [35,42].

Regarding the most relevant results associated with ability, of the various departments of the organizations, to adapt to technological changes, we found that the most agile departments are Manufacturing/Logistics, Customer Service and Human Resources in the “Product/Customer” dimension (Dimension 1). For the dimension Marketing/Sales (Dimension 2), the most agile departments are Marketing and Sales/Business. A more detailed analysis of these results allowed us to identify four groups within organizations according to their adaptability to technological changes: Business, Customer, Personal and Technological.

An additional point of note is that although there are organizations in which the new role of CDO begins to emerge at the level of the organization’s management, in the sample of Portuguese organizations under study, no respondents with this function were found. Notwithstanding the result obtained for Portuguese organizations, CDO has a major role in companies, citing [46] “CDO is both a bridge and a separator between business units and IT that ensures smooth project development and implementation.”

The completed research presented here confirms that digital transformation to succeed on the one hand must have a strategy and, on the other hand, leads to the transformation of the business model of the organization. However, the results obtained are not sufficiently enlightening to establish the implications for strategy and business models. In this context, the study confirms that an ad hoc transformation by organizations, i.e., without defining a digital transformation implementation strategy, and the behavior of actors at all hierarchical levels, namely CIOs, is counterproductive leading to failure and even endangers the organization itself.

Further studies are required by sector of activity to assess whether their business models are similar, which implies the existence of a more generic or sector-specific framework (e.g., Retail sector [58]), while respecting the individuality of the intrinsic model of the organization [7].

Although it has been found that Portuguese organizations are aware of the need to accommodate digital transformation, the study presented in [48] found that Portugal, compared to the other 26 European Union countries, is relatively efficient in digital transformation.

This study has implications for both business and the academy. In an academic perspective, the study provides an exploratory review of the literature on digital transformation concepts, giving a conceptual structure of the main aspects of digital transformation in organizations that are still in a pre-digital phase and others already in transformation. This approach provides an initial perspective on how to manage the key factors to be addressed in order to carry out successful digital transformations. From a practical/practitioner point of view, the research gives us some valuable insights of the current situation of Portuguese organizations in the DT context, and despite the limitations already discussed in the previous section it points out potential outcomes in a near future.

Author Contributions

The present paper is the result of a widely collaboration between Portucalense and Ramon Llull universities for the realization of multidisciplinary educational projects and research. Over the past five years, the research coordinators F.M. and D.F. have identified educational projects with a clear digital transformation component in order to be applied across different fields of knowledge (engineering, architecture, business, etc.) Once the base of each project is established, the case of the study is transferred to one of the groups for its development using and combining different components, skills and necessities of both entities. In this paper, the second phase was coordinated by C.S.P. with the support of N.D. and the supervision of M.J.F. For the present work, the completely distribution of tasks are the following: C.S.P.—Conceptualization; Investigation; N.D.—Formal Analysis; Resources; D.F.—Funding Acquisition; Visualization; Writing—review and editing; M.J.F.—Methodology; Supervision; F.M.—Visualization; Writing—original draft; Writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Secretaria d’Universitats i Recerca of the Department of Business and Knowledge of the Generalitat de Catalunya, grant number 2017 SGR 934.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Tomić, D. IDC Reveals Worldwide Digital Transformation Predictions. Available online: http://www.ictbusiness.biz/analysis/idc-reveals-worldwide-digital-transformation-predictions (accessed on 15 June 2019).

- Westerman, G.; Bonnet, D.; McAfee, A. The Digital Transformation People. Available online: https://www.thedigitaltransformationpeople.com/channels/the-case-for-digital-transformation/leadingdigital-a-summary/ (accessed on 15 June 2019).

- Schuelke-Leech, B. A model for understanding the orders of magnitude of disruptive technologies. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2018, 129, 261–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, D.; Conde, M.Á.; García-Peñalvo, F.J. Improving the information society skills: Is knowledge accessible for all? Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2017, 17, 229–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dede, C. Emerging influences of information technology on school curriculum. J. Curric. Stud. 2000, 32, 281–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanias, S.; Myers, M.D.; Hess, T. Digital transformation strategy making in pre-digital organizations: The case of a financial services provider. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2019, 28, 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loonam, J.; Eaves, S.; Kumar, V.; Parry, G. Towards digital transformation: Lessons learned from traditional organizations. Strateg. Chang. 2018, 27, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerman, G.; Bonnet, D.; McAfee, A. Leading Digital: Turning Technology into Business Transformation, 1st ed.; Harvard Business Review Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, R.; Sai, S.K. Hummel’s digital transformation toward omnichannel retailing: Key lessons learned. MIS Q. Exec. 2015, 14, 51–66. [Google Scholar]

- Uhl, A.; Gollenia, L. Digital Enterprise Transformation: A Business-Driven Approach to Leveraging Innovative It; Routledge Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- IDC. Third Platform. Available online: http://www.idc.com/promo/thirdplatform (accessed on 20 June 2019).

- Melian-Gonzalez, S.; Bulchand-Gidumal, J. A model that connects information technology and hotel performance. Tour. Manag. 2016, 53, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vial, G. Understanding digital transformation: A review and a research agenda. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2019, 28, 118–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, T.; Matt, C.; Benlian, A.; Wiesboeck, F. Options for formulating a digital transformation strategy. MIS Q. Exec. 2016, 15, 123–139. [Google Scholar]

- Hausberg, J.; Liere-Netheler, K.; Packmohr, S.; Pakura, S.; Vogelsang, K. Digital Transformation in Business Research: A Systematic Literature Review and Analysis. In Proceedings of the DRUID, Copenhagen Business School, Copenhagen, Denmark, 11–13 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Oestreicher-Singer, G.; Zalmanson, L. Paying for Content or Paying for Community? The Effect of Social Computing Platforms on Willingness to Pay in Content Websites’. Available online: http://ftp.zew.de/pub/zew-docs/veranstaltungen/SEEK2011/papers/OestreicherZalmanson.pdf (accessed on 24 June 2019).

- Lucas, H.; Agarwal, R.; Clemons, E.; El Sawy, O.; Weber, B. Impactful research on transformational information technology: An opportunity to inform new audiences. MIS Q. 2013, 37, 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruman, G. What Digital Transformation Really Means. Available online: http://www.infoworld.com/article/3080644/it-management/what-digital-transformationreally-means.html (accessed on 25 June 2019).

- Goerzig, D.; Bauernhansl, T. Enterprise architectures for the digital transformation in small and medium-sized enterprises. Procedia CIRP 2018, 67, 540–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusch, R.F.; Nambisan, S. Service innovation: A service-dominant logic perspective. MIS Q. 2015, 39, 155–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, C.; Hess, T. Becoming Agile in the Digital Transformation: The Process of a Large-Scale Agile Transformation. In Proceedings of the Thirty-Ninth International Conference on Information Systems, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–16 December 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Aghina, W.; Smete, A.D.; Weerda, K. Agility: It Rhymes with Stability. McKinsey Q. 2015, 51, 2–9. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/organization/our-insights/agility-it-rhymes-with-stability (accessed on 25 June 2019).

- McKinsey. How to Create an Agile Organization. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/organization/our-insights/how-to-create-an-agile-organization (accessed on 4 June 2019).

- Sambamurthy, V.; Bharadwaj, A.; Grover, V. Shaping Agility through Digital Options: Reconceptualizing the Role of Information Technology in Contemporary Firms. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 237–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, G.C.; Palmer, D.; Phillips, A.N.; Kiron, D.; Buckley, N. Strategy, not technology, drives digital transformation—Becoming a Digitally Mature Enterprise. In MIT Sloan Management Review; Deloitte University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Karanges, E.; Johnston, K.; Beatson, A.; Lings, I. The influence of internal communication on employee engagement: A pilot study. Public Relat. Rev. 2015, 41, 129–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Hess, T. How chief digital officers promote the digital transformation of their companies. MIS Q. Exec. 2017, 16, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A. Role of HR in digital transformation. HR Future 2019, 4, 16–17. [Google Scholar]

- Mergel, I.; Edelmann, N.; Haug, N. Defining digital transformation: Results from expert interviews. Gov. Inf. Q. 2019, 36, 101385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinsey. The ‘How’ of Transformation. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/retail/our-insights/the-how-of-transformation (accessed on 4 September 2019).

- Patel, H.; Pettitt, M.; Wilson, J.R. Factors of collaborative working: A framework for a collaboration model. Appl. Ergon. 2012, 43, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolou, D.; Zachos, K.; Maiden, N.; Agell, N.; Sanchez-Hernandez, G.; Taramigkou, M.; Star, K.; Wippoo, M. Facilitating Creativity in Collaborative Work with Computational Intelligence Software. IEEE Comput. Intell. Mag. 2016, 11, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Mendonca, C.; de Andrade, A. Microfoundations of dynamic capabilities and their relations with elements of digital transformation in Portugal. In Proceedings of the 13th CISTI, Caceres, Spain, 13–16 June 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, N. Digital Transformation at Turismo de Portugal. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal, 30 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- van Dyk, R.; Van Belle, J.P. Factors Influencing the Intended Adoption of Digital Transformation: A South African Case Study. In Proceedings of the 2019 Federated Conference on Computer Science and Information Systems (FedCSIS), Leipzig, Germany, 1–4 September 2019; pp. 519–528. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann, A.; Schmidt, R.; Sandkuhl, K.; Jugel, D.; Bogner, J.; Möhring, M. Evolution of enterprise architecture for digital transformation. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 22nd International Enterprise Distributed Object Computing Workshop (EDOCW), Stockholm, Sweden, 16–19 October 2018; pp. 87–96. [Google Scholar]

- Ershova, T.V.; Hohlov, Y.E. Digital Transformation Framework Monitoring of Large-Scale Socio-Economic Processess. In Proceedings of the 2018 Eleventh International Conference “Management of large-scale system development” (MLSD), Moscow, Russia, 1–3 October 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zulfikar, M.W.; bin Hashim, A.I.; bin Ahmad Umri, H.U.; Dahlan, A.R. A Business Case for Digital Transformation of a Malaysian-Based University. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Information and Communication Technology for the Muslim World (ICT4M), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 23–25 July 2018; pp. 106–109. [Google Scholar]

- Azarenko, N.Y.; Mikheenko, O.V.; Chepikova, E.M.; Kazakov, O.D. Formation of Innovative Mechanism of Staff Training in the Conditions of Digital Transformation of Economy. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference Quality Management, Transport and Information Security, Information Technologies (IT&QM&IS), St. Petersburg, Russia, 24–28 September 2018; pp. 764–768. [Google Scholar]

- Ebert, C.; Duarte, C.H.C. Digital Transformation. IEEE Softw. 2018, 35, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guinan, P.J.; Parise, S.; Langowitz, N. Creating an innovative digital project team: Levers to enable digital transformation. Bus. Horiz. 2019, 62, 717–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, M.J.; Rocha, Á. Digital learning: Developing skills for digital transformation of organizations. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2019, 91, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, N.C. Managing for competency with innovation change in higher education: Examining the pitfalls and pivots of digital transformation. Bus. Horiz. 2019, 62, 761–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J. Digital transformation in higher education: Critiquing the five-year development plans (2016–2020) of 75 Chinese universities. Distance Educ. 2019, 40, 515–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrigoni, G.; Schofield, T.; Trujillo, P.D. Framing collaborative processes of digital transformation in cultural organisations: From literary archives to augmented reality. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 2019, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivančić, L.; Vukšić, V.B.; Spremić, M. Mastering the digital transformation process: Business practices and lessons learned. Technol. Innov. Manag. Rev. 2019, 2, 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhlungu, N.S.; Chen, J.Y.; Alkema, P. The underlying factors of a successful organisational digital transformation. S. Afr. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 21, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İnel, M. An empirical study on measurement of efficiency of digital transformation by using data envelopment analysis. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2019, 9, 549–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galindo-Martin, M.-A.; Castano-Martinez, M.-S.; Mendez-Picazo, M.-T. Digital transformation, digital dividends and entrepreneurship: A quantitative analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 101, 522–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroco, J. Análise Estatística com o SPSS, 7th ed.; ReportNumber; Lda: Lisboa, Portugal, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Pestana, M.; Gageiro, J. Análise de Dados para Ciências Sociais. A Complementaridade do SPSS, 6th ed.; Edições Sílabo: Lisboa, Portugal, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavior Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Association: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, M.; Hill, A. Investigação por questionário. Edições Sílabo, 2nd ed.; Lda: Lisboa, Portugal, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Spremic, M. Governing Digital Technology–How Mature IT Governance can help in Digital Transformation? Int. J. Econ. Manag. Syst. 2017, 2, 214–223. [Google Scholar]

- Reis, J.; Amorim, M.; Melão, N. Matos PDigital Transformation: ALiterature Review Guidelines for Future Research. In Trends and Advances in Information Systems and Technologies; Rocha, Á., Adeli, H., Reis, L.P., Costanzo, S., Eds.; Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; p. 745. [Google Scholar]

- Holotiuk, F.; Beimborn, D. Critical Success Factors of Digital Business Strategy. Available online: https://aisel.aisnet.org/wi2017/track09/paper/5/ (accessed on 8 January 2020).

- Libert, B.; Beck, M.; Wind, Y. Questions to Ask before Your Next Digital Transformation. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2016, 60, 11–13. Available online: http://docs.media.bitpipe.com/io_13x/io_137680/item_1538075/7%20Questions%20to%20Ask%20Before%20Your%20Next%20Digital%20Transformation.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2020).

- Ferreira, M.J.; Moreira, F.; Pereira, C.S.; Durão, N. The Digital Transformation at organizations—The case of retail sector. In Proceedings of the WorldCist’20—8th World Conference on Information Systems and Technologies, Budva, Montenegro, 7–10 April 2020. Accepted for publication. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).