Egyptian Shabtis Identification by Means of Deep Neural Networks and Semantic Integration with Europeana

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Overview of Related Work

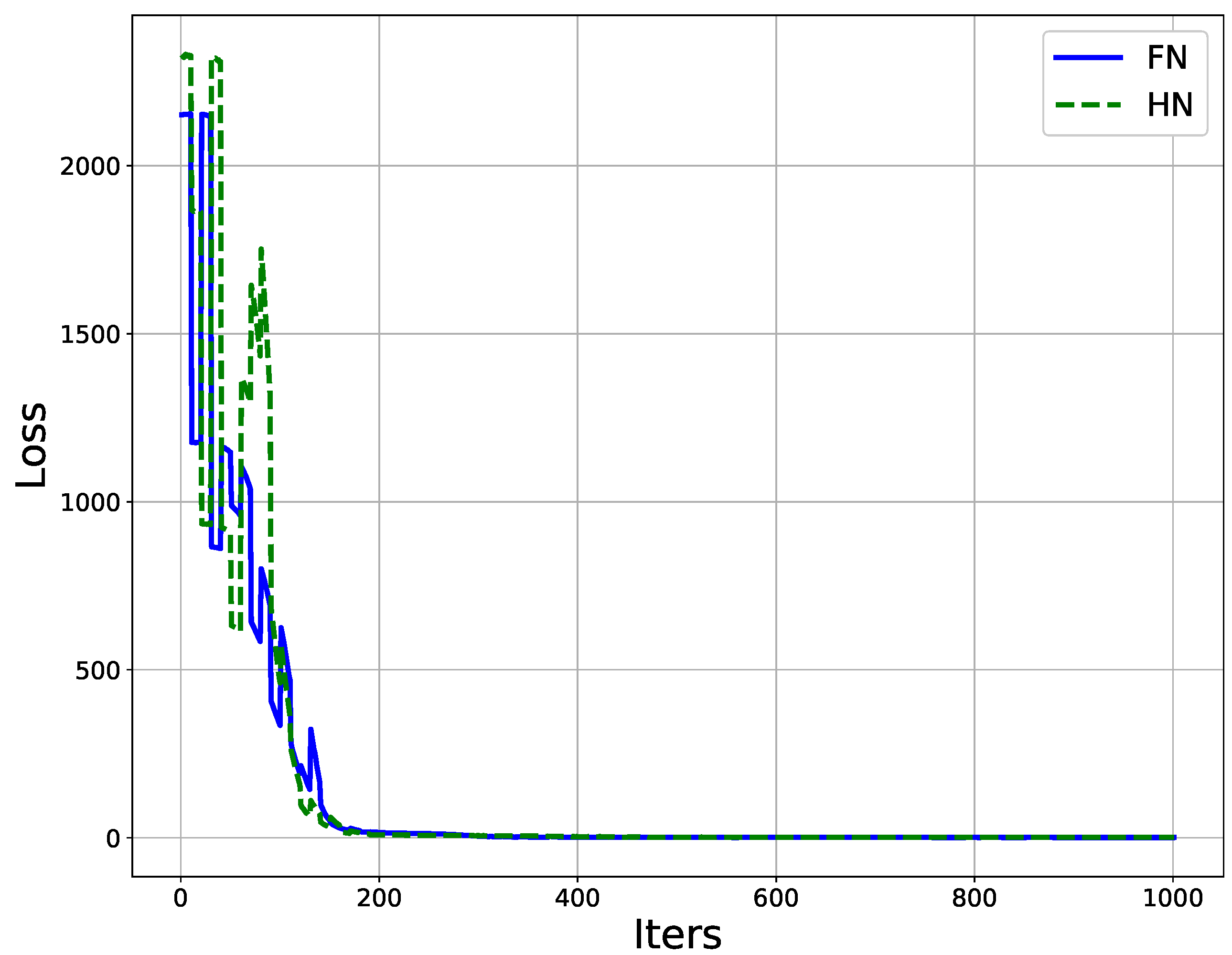

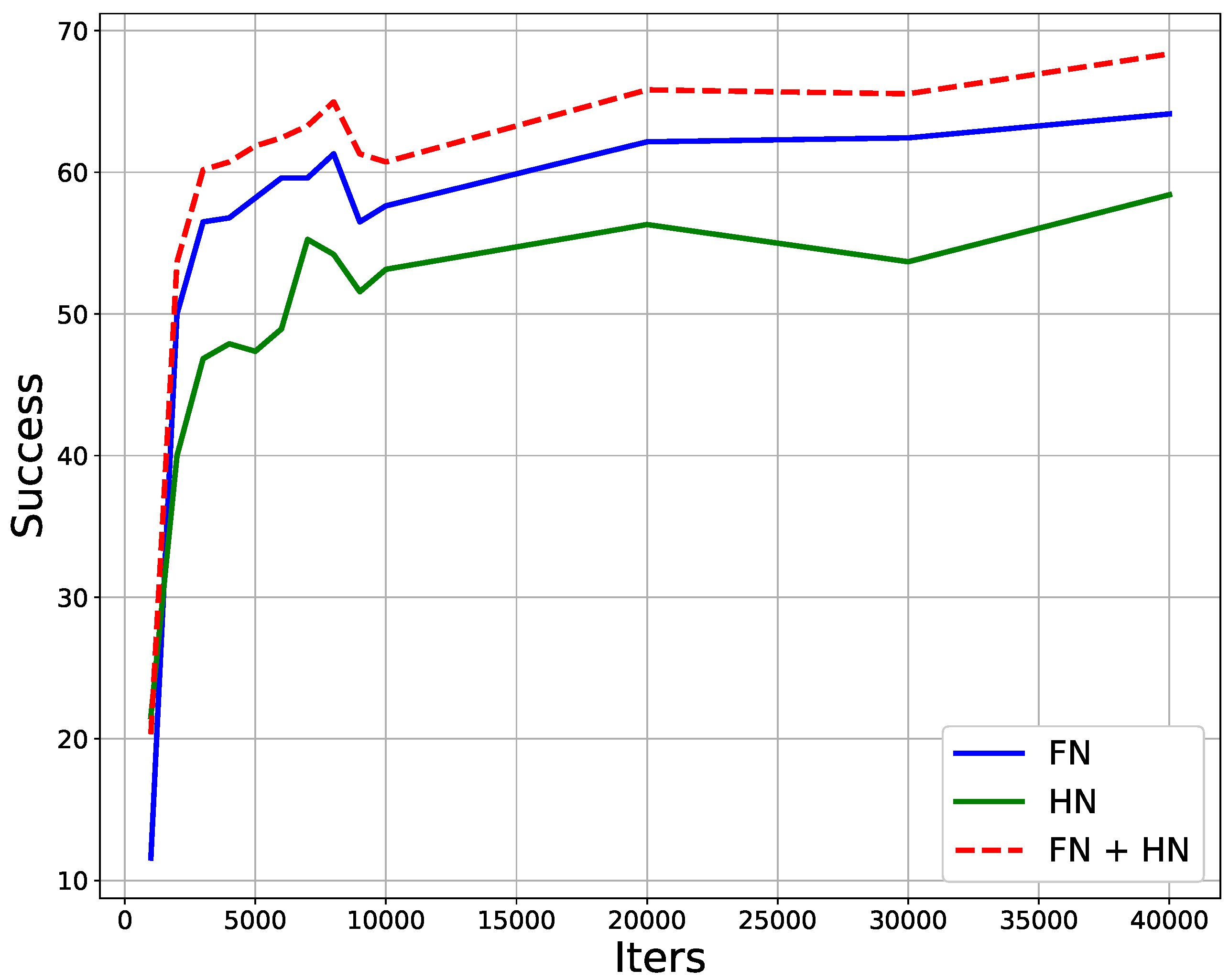

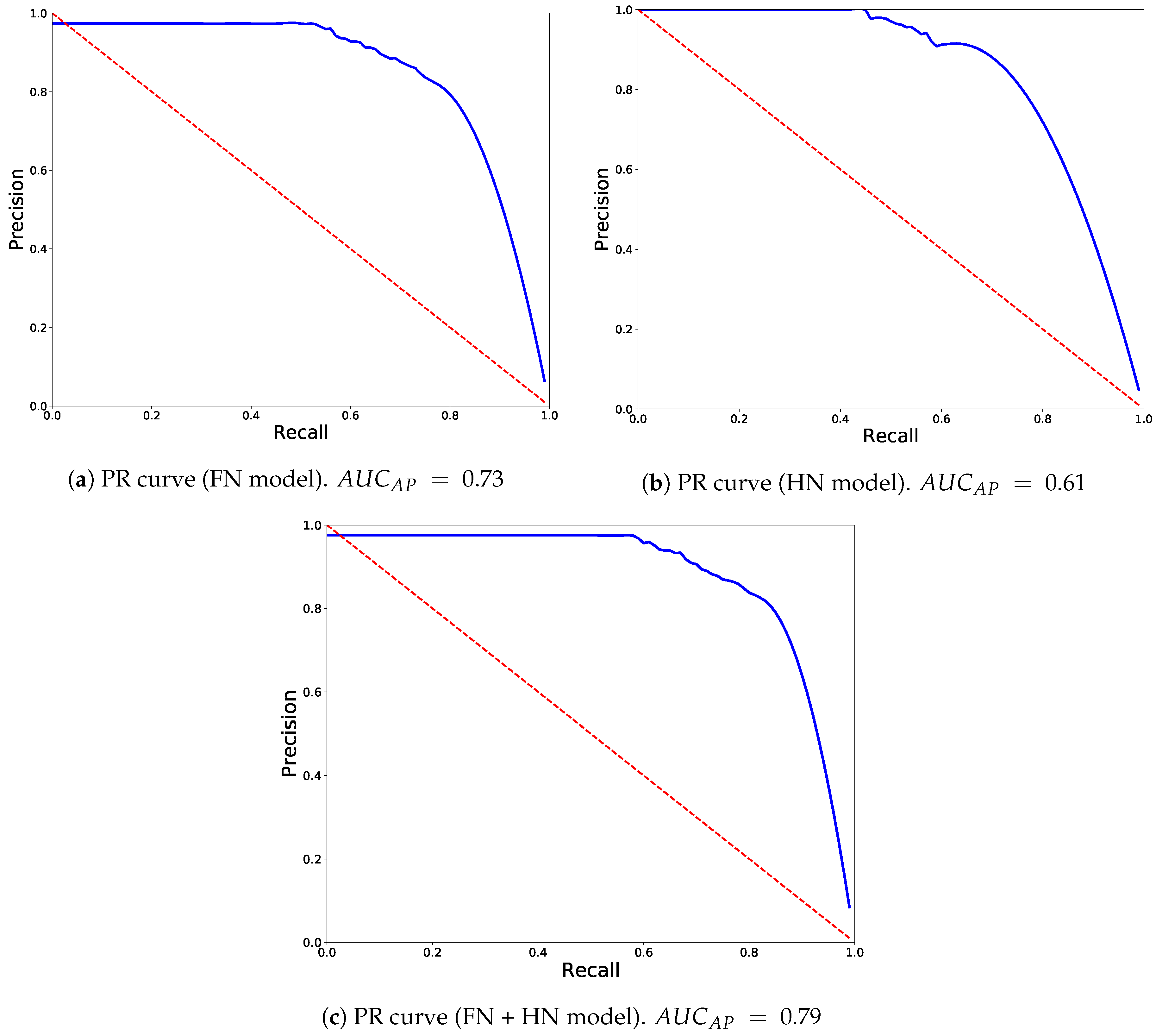

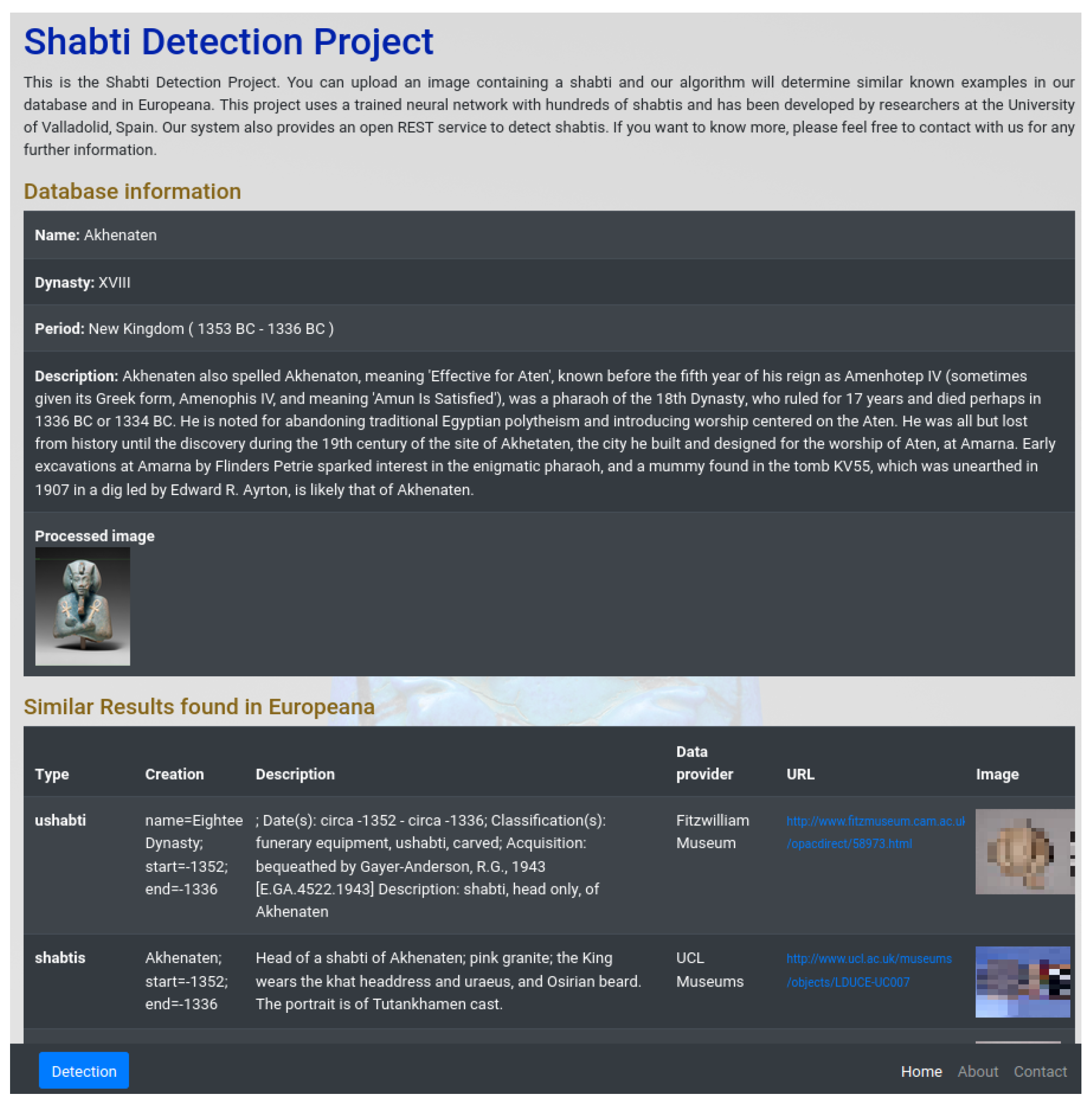

3. Analysis of the System

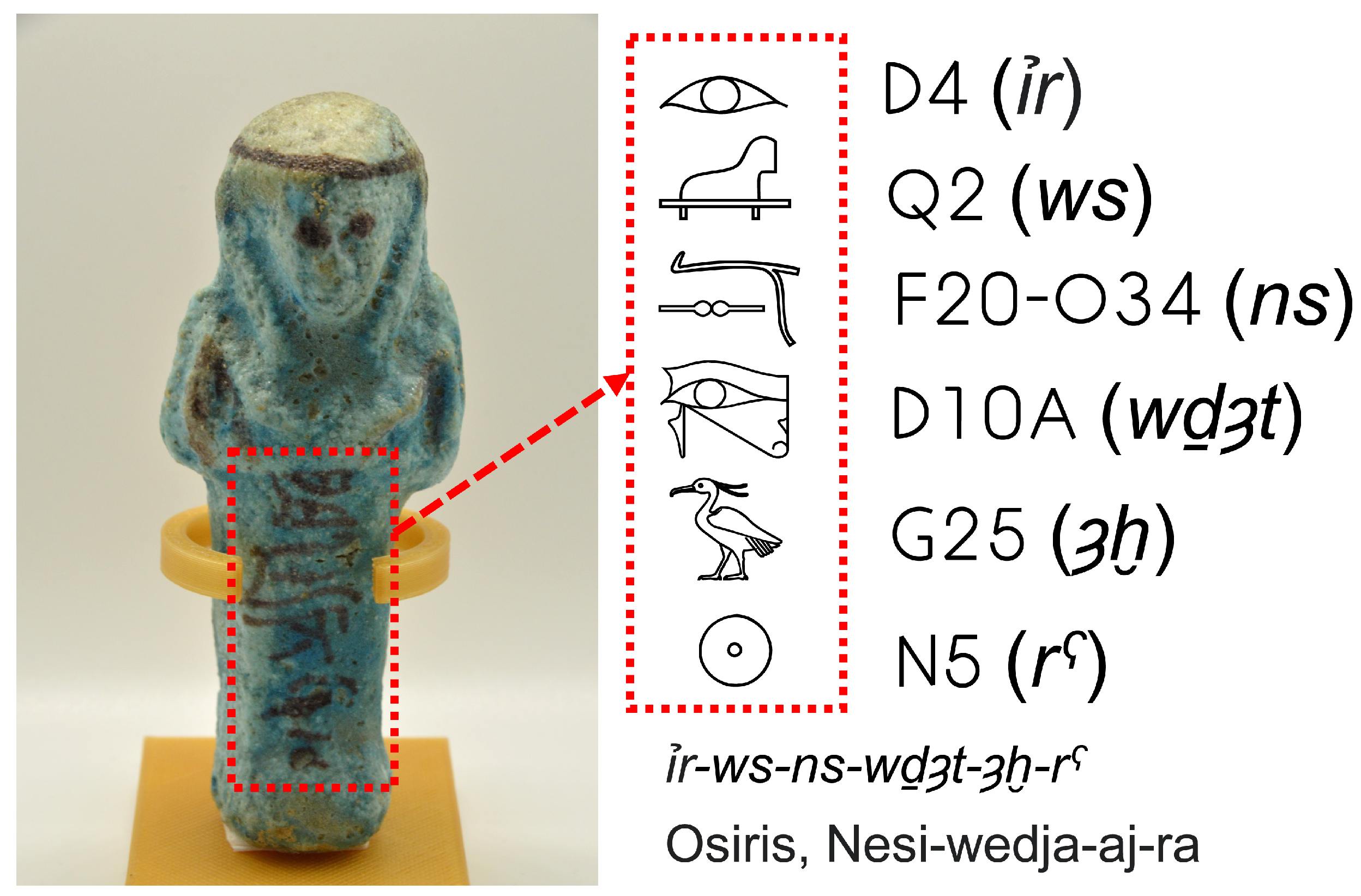

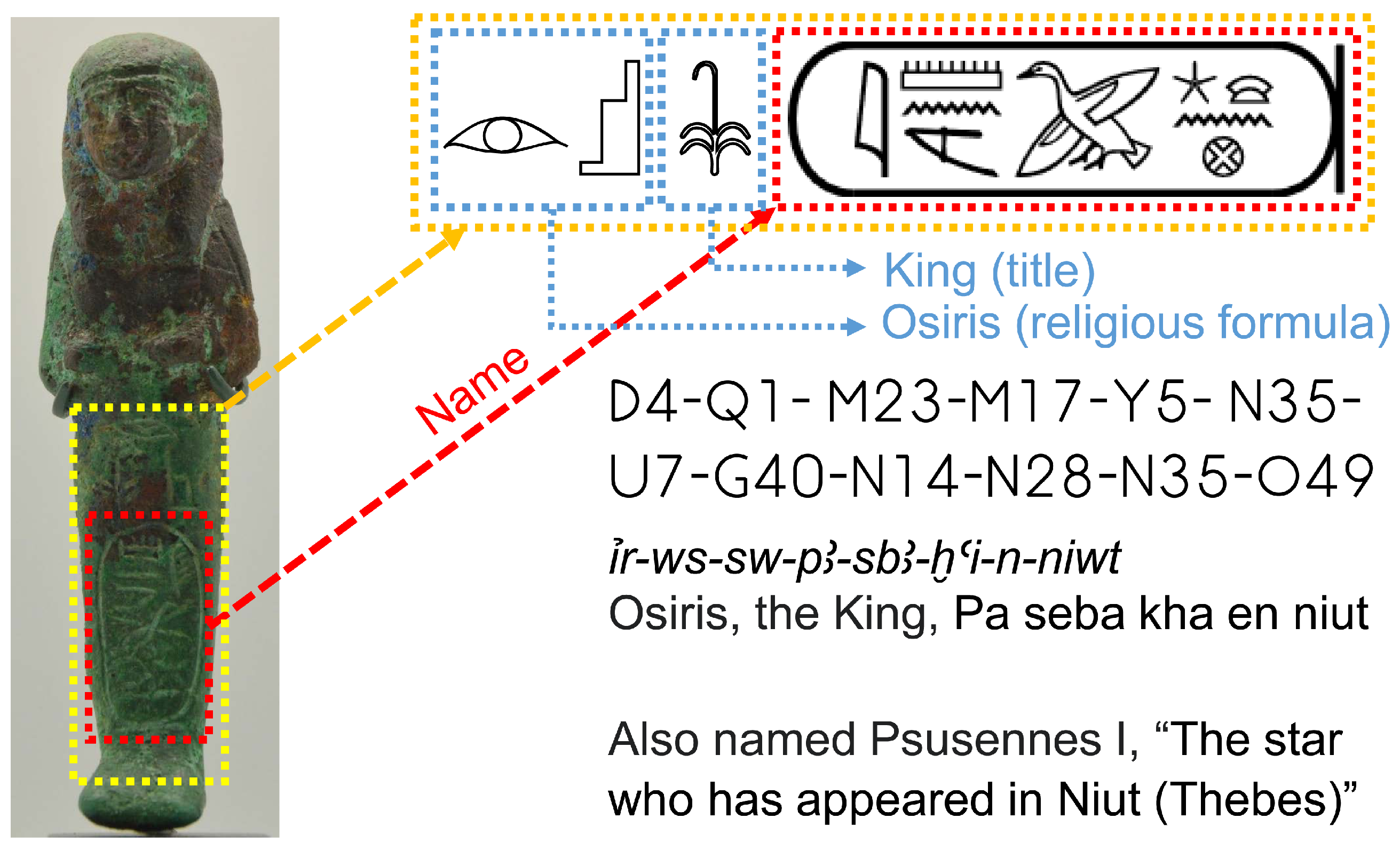

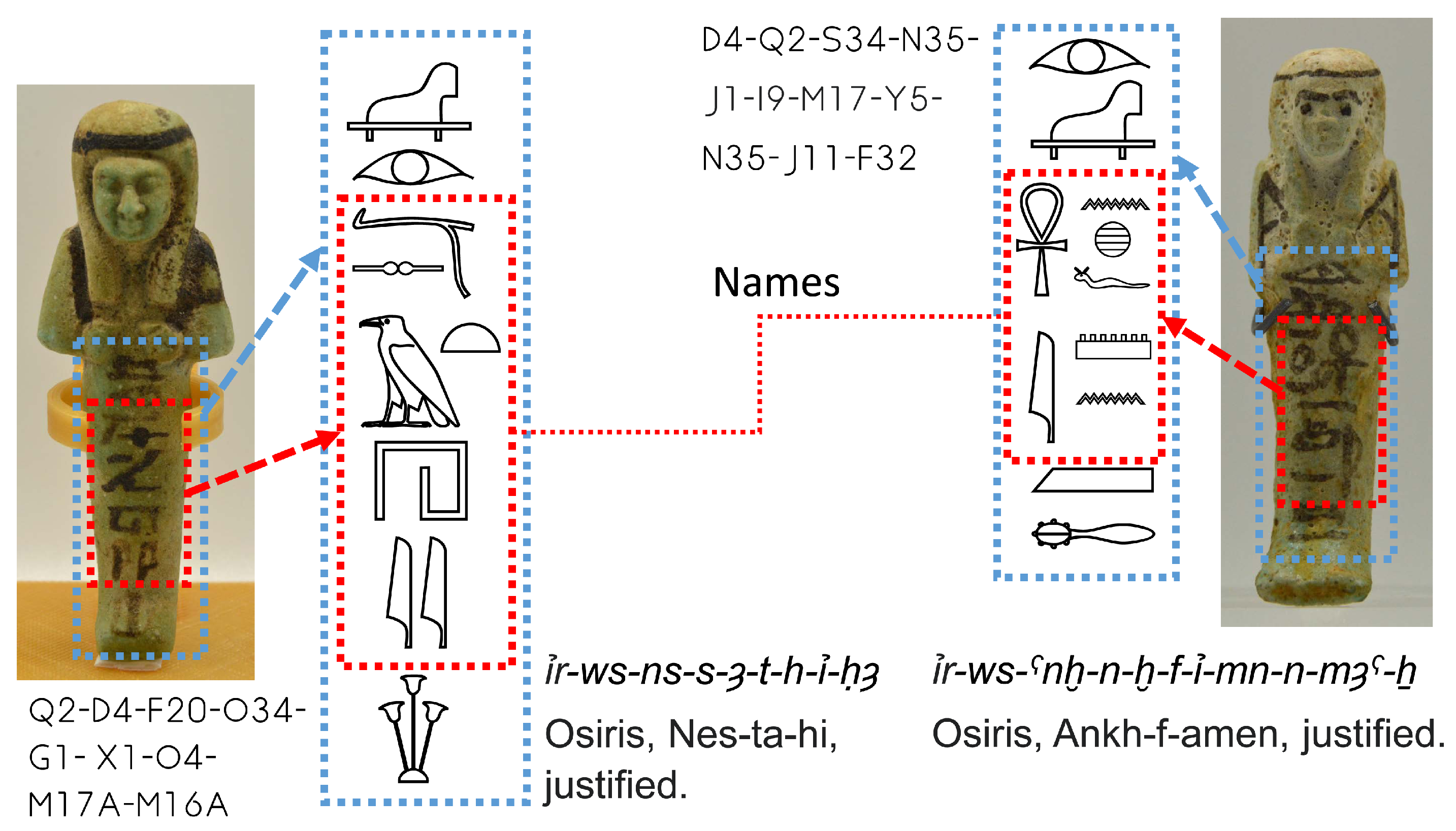

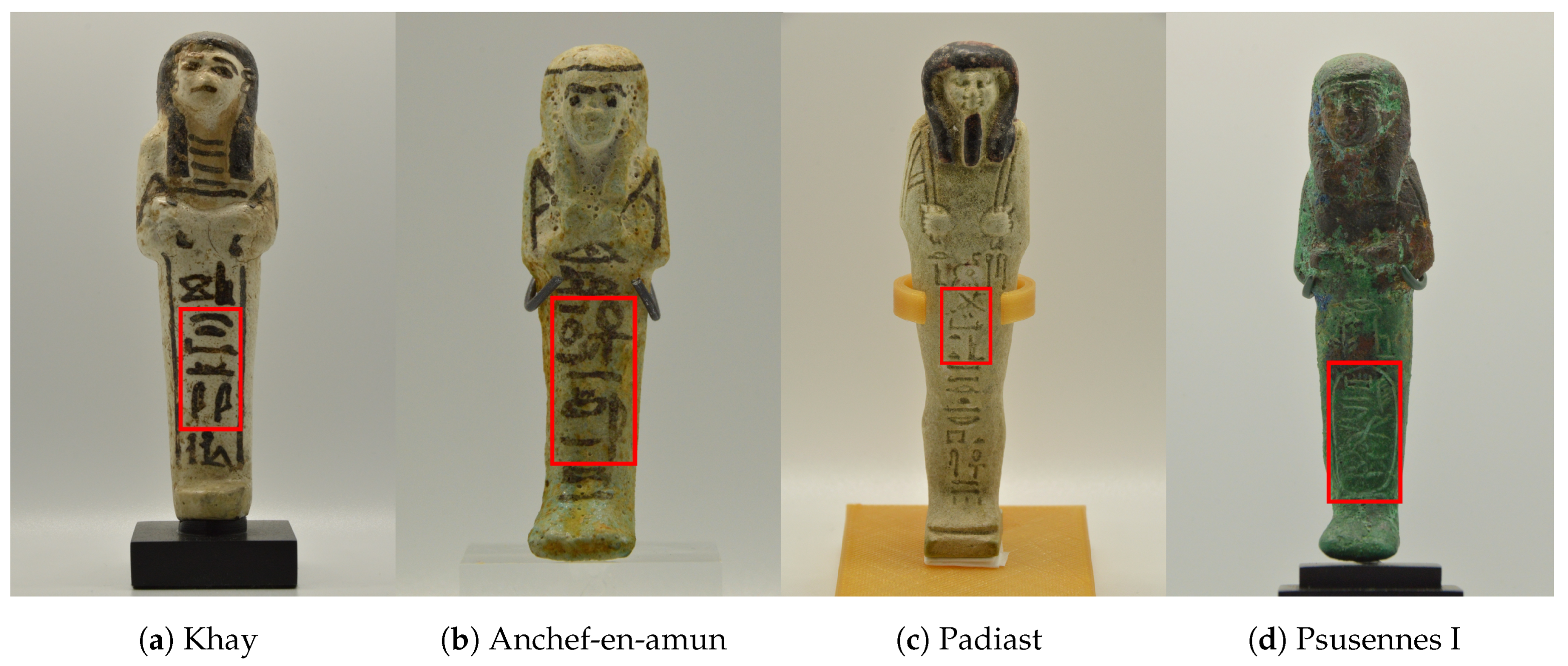

3.1. The Classification of Shabtis

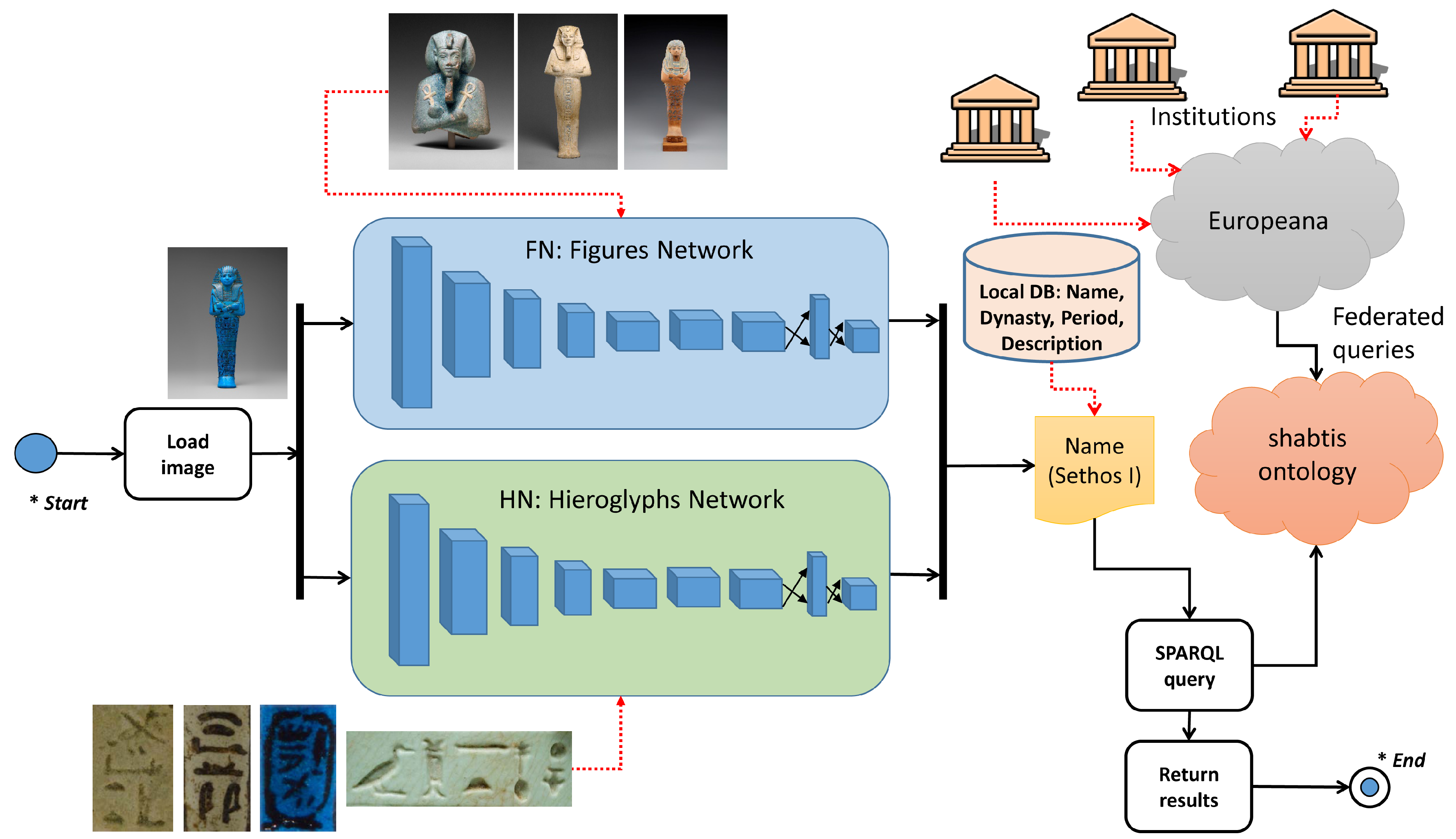

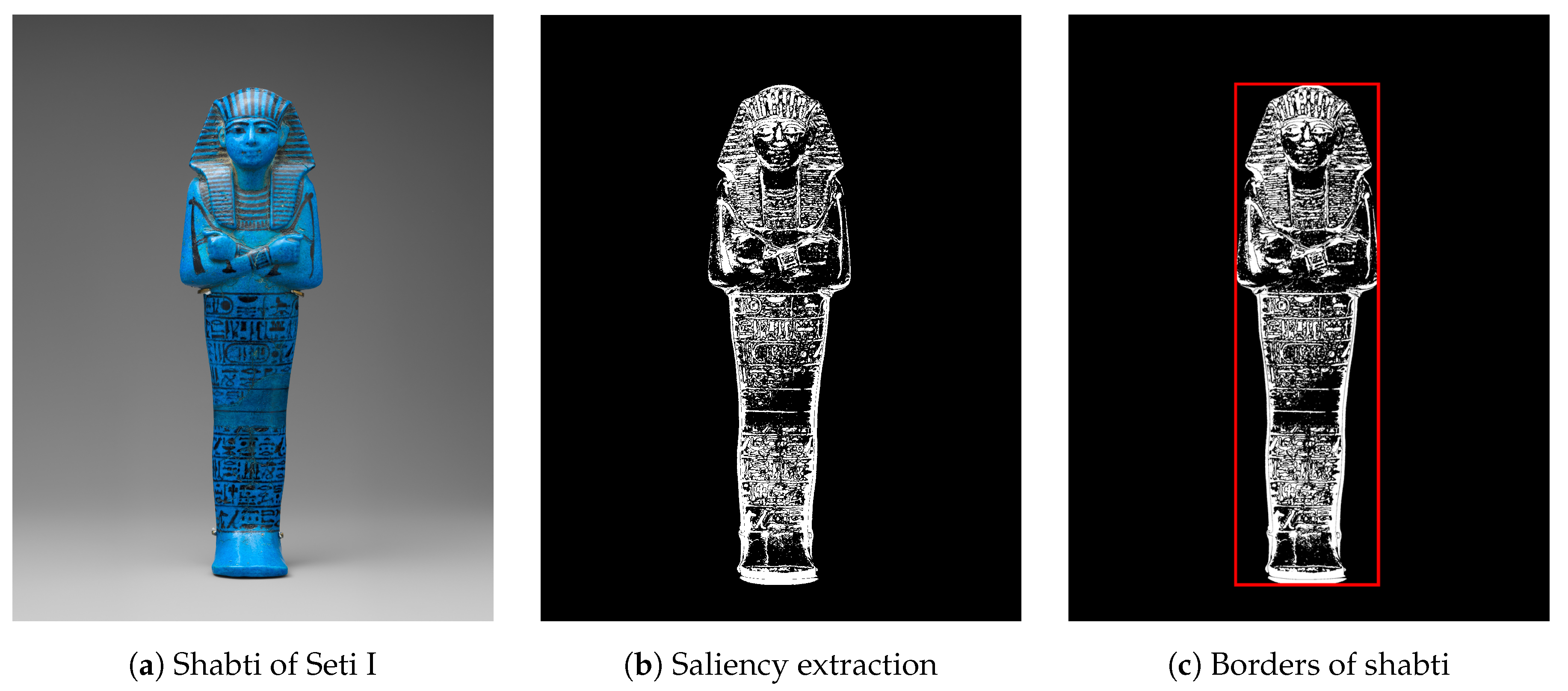

3.2. The System to Detect Shabtis

- An input image is introduced in the two YOLO networks.

- If the FN model returns some detections (, ,..., ), the class with the highest confidence, , is selected after applying non-maxima suppression to suppress weak, overlapping bounding boxes.

- If the HN model returns some detections (, ,..., ), the class with the highest confidence, , is selected after applying non-maxima suppression to suppress weak, overlapping bounding boxes.

- If both models have returned detections, is selected when , and otherwise. If the bounding box is not inside the bounding box , the non-selected class is also shown to the user as another possibility whenever the class is different.

- If only the FN model has returned detections, is selected.

- If only the HN model has returned detections, is selected.

- Local data and data retrieved from Europeana are shown for the selected class.

- Batch normalization, to help regularize the model and reduce overfitting.

- High resolution images, passing from small input images of 224 × 224 to 448 × 448.

- Anchor boxes, to predict more bounding boxes per image.

- Fine-grained features, which helps to locate small objects while being efficient for large objects.

- Multi-scale training, randomly changing the image dimensions during training to detect small objects. The size is increased from a minimum of 320 × 320 to a maximum of 608 × 608.

- Modifications to the internal network, using a new classification model as a backbone classifier.

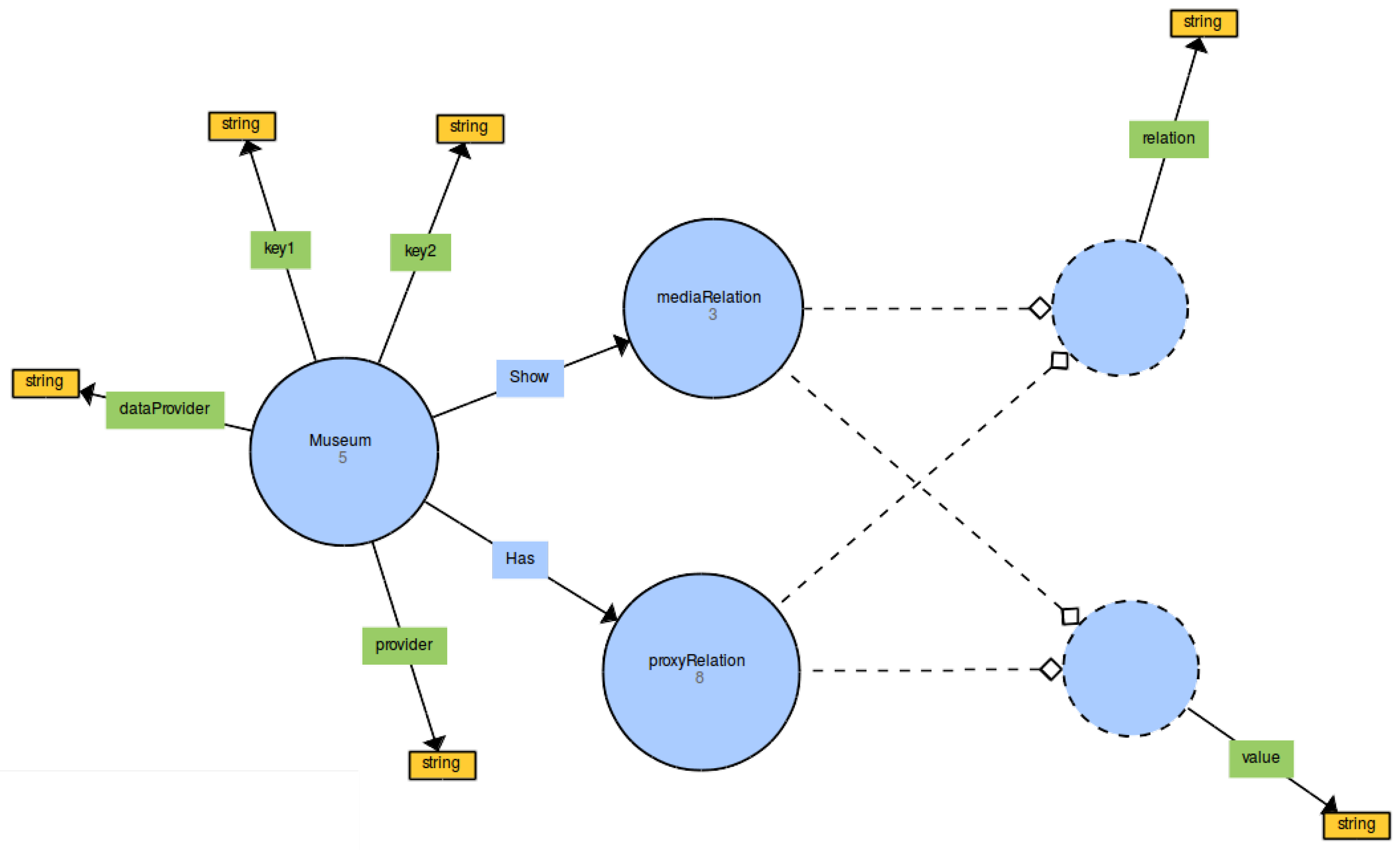

3.3. New Ontology

4. Experiments and Results Discussion

PREFIX shabt i s : <http://www.amenofis.com/shabtis.owl#> PREFIX dc : <http://purl.org/dc/elements/1.1/> PREFIX dc_e : <http://purl.org/dc/terms/> PREFIX edm: <http://www.europeana.eu/schemas/edm/> PREFIX rdf : <http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22–rdf–syntax–ns#> PREFIX ore : <http://www.openarchives.org/ore/terms/> PREFIX skos : <http://www.w3.org/2004/02/skos/core#> PREFIX rdf s : <http://www.w3.org/2000/01/rdf–schema#> SELECT DISTINCT (GROUP_CONCAT(DISTINCT CONCAT( ? value , " : " , s t r ( ? val ) ) ; SEPARATOR=" ; ; ; " ) AS ? r e l a t ionVa lue s ) (GROUP_CONCAT(DISTINCT CONCAT( ? sValue , " : " , s t r ( ? sVal ) ) ; SEPARATOR=" ; ; ; " ) AS ? showValues ) ?ProvidedCHO ? dataProvider ? provider WHERE { ?museum shabt i s : provider ? provider . ?museum shabt i s : dataProvider ? dataProvider . ?museum shabt i s : key1 ? key1 . BIND( IRI ( ? key1 ) AS ?k1 ) . ?museum shabt i s : key2 ? key2 . BIND( IRI ( ? key2 ) AS ?k2 ) . ?museum shabt i s :Has ? pRelat ion . ? pRelat ion shabt i s : r e l a t i o n ? r e l a t i o n . BIND( IRI ( ? r e l a t i o n ) AS ? r e l ) . ? pRelat ion shabt i s : value ? value . ?museum shabt i s : Show ? sRe l a t ion . ? sRe l a t ion shabt i s : r e l a t i o n ? showRelation . BIND( IRI ( ? showRelation ) AS ? sRel ) . ? sRe l a t ion shabt i s : value ? sValue . SERVICE <http://sparql.europeana.eu> { ?ProvidedCHO edm: dataProvider ? dataProvider . ?ProvidedCHO edm: provider ? provider . ?proxy ore : proxyIn ?ProvidedCHO. ?proxy ?k1 ?v1 . ?proxy ?k2 ?v2 . ?proxy ? r e l ? val . ?ProvidedCHO ? sRel ? sVal . FILTER (CONTAINS( ? v1 , " habt i " ) && CONTAINS( ? v2 , "Akhenaten " ) ) . } } GROUP BY ?ProvidedCHO ? dataProvider ? provider

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Quibell, J. Note on a tomb found at Tell er Roba. In Annales du Service des Antiquités de l’Égypte; Conseil Suprême des Antiquités Égyptiennes: Cairo, Egypt, 1902; Volume 3, pp. 245–249. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, H.D. Shabtis: An Introduction to the History of Ancient Egyptian Funerary Statuettes with a Catalogue of the Collection of Shabtis in the National Museum of Antiquities at Leiden: Collections of the National Museum of Antiquities at Leiden; Rijksmuseum van Oudheden: Leiden, The Netherlands, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, H.M. Egyptian Shabtis; Osprey Publishing: Oxford, UK, 1995; Volume 23. [Google Scholar]

- Petrie, S.W.M.F. Shabtis: Illustrated by the Egyptian Collection in University College, London; Aris & Phillips: London, UK, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Janes, G.; Bangbala, T. Shabtis, A Private View: Ancient Egyptian Funerary Statuettes in European Private Collections; Cybèle: Paris, France, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Aubert, J.F.; Aubert, L. Statuettes égyptiennes: Chaouabtis, Ouchebtis; Librairie d’Amérique et d’Orient: Paris, France, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- de Araújo, L.M. Estatuetas Funerárias Egípcias da XXI Dinastia; Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian: Lisboa, Portugal, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Newberry, P.E. Funerary Statuettes and Model Sarcophagi; Catalogue général des Antiquités Égyptiennes du Musée du Caire; Institut français d’archéologie orientale, Service des Antiquités de l’Égypte: Cairo, Egypt, 1930. [Google Scholar]

- Bovot, J.L. Les Serviteurs Funéraires Royaux et Princiers de L’ancienne Egypte; Réunion des Musées Nationaux: Paris, France, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Brodbeck, A.; Schlogl, H. Agyptische Totenfiguren aus Offentlichen und Privaten Sammlungen der Schweiz; OBO SA; Universitätsverlag Freiburg Schweiz, Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht Göttingen: Fribourg, Switzerland, 1990; Volume 7. [Google Scholar]

- Janes, G. The Shabti Collections: West Park Museum, Macclesfield; Olicar House Publications: Cheshire, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Janes, G.; Gallery, W.M.A. The Shabti Collections. 2. Warrington Museum & Art Gallery; Olicar House Publications: Cheshire, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Janes, G.; Moore, A. The Shabti Collections: Rochdale Arts & Heritage Service; Olicar House Publications: Cheshire, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Janes, G.; Cavanagh, K. The Shabti Collections: Stockport Museums; Olicar House Publications: Cheshire, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Manchester University Museum; Janes, G. The Shabti Collections: A Selection from Manchester Museum; Olicar House Publications: Cheshire, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- World Museum Liverpool; Janes, G. The Shabti Collections: A Selection from World Museum, Liverpool; Olicar House Publications: Cheshire, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zambanini, S.; Kampel, M. Coarse-to-fine correspondence search for classifying ancient coins. In Proceedings of the Asian Conference on Computer Vision, Daejeon, Korea, 5–9 November 2012; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2012; pp. 25–36. [Google Scholar]

- Aslan, S.; Vascon, S.; Pelillo, M. Ancient coin classification using graph transduction games. In Proceedings of the 2018 Metrology for Archaeology and Cultural Heritage (MetroArchaeo), Cassino FR, Italy, 22–24 October 2018; pp. 127–131. [Google Scholar]

- Aslan, S.; Vascon, S.; Pelillo, M. Two sides of the same coin: Improved ancient coin classification using Graph Transduction Games. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2020, 131, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, H.; Zambanini, S.; Kampel, M.; Vondrovec, K. Ancient coin classification using reverse motif recognition: Image-based classification of roman republican coins. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 2015, 32, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirza-Mohammadi, M.; Escalera, S.; Radeva, P. Contextual-guided bag-of-visual-words model for multi-class object categorization. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computer Analysis of Images and Patterns, Münster, Germany, 2–4 September 2009; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2009; pp. 748–756. [Google Scholar]

- Anwar, H.; Anwar, S.; Zambanini, S.; Porikli, F. CoinNet: Deep Ancient Roman Republican Coin Classification via Feature Fusion and Attention. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1908.09428. [Google Scholar]

- Llamas, J.; M Lerones, P.; Medina, R.; Zalama, E.; Gómez-García-Bermejo, J. Classification of architectural heritage images using deep learning techniques. Appl. Sci. 2017, 7, 992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makridis, M.; Daras, P. Automatic classification of archaeological pottery sherds. J. Comput. Cult. Herit. (JOCCH) 2013, 5, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdia, K.M.; Ghasemi, H.; Zhuang, X.; Alajlan, N.; Rabczuk, T. Computational machine learning representation for the flexoelectricity effect in truncated pyramid structures. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2019, 59, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdia, K.M.; Ghasemi, H.; Bazi, Y.; AlHichri, H.; Alajlan, N.; Rabczuk, T. A novel deep learning based method for the computational material design of flexoelectric nanostructures with topology optimization. Finite Elem. Anal. Des. 2019, 165, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, D.G. Object recognition from local scale-invariant features. In Proceedings of the Seventh IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Kerkyra, Greece, 20–27 September 1999; Volume 99, pp. 1150–1157. [Google Scholar]

- Bay, H.; Ess, A.; Tuytelaars, T.; Van Gool, L. Speeded-up robust features (SURF). Comput. Vis. Image Underst. 2008, 110, 346–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rublee, E.; Rabaud, V.; Konolige, K.; Bradski, G. ORB: An efficient alternative to SIFT or SURF. In Proceedings of the 2011 International Conference on Computer Vision, Barcelona, Spain, 6–13 November 2011; pp. 2564–2571. [Google Scholar]

- Redmon, J.; Farhadi, A. YOLOv3: An Incremental Improvement. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.02767. [Google Scholar]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 779–788. [Google Scholar]

- Redmon, J.; Farhadi, A. YOLO9000: Better, Faster, Stronger. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1612.08242. [Google Scholar]

- Russakovsky, O.; Deng, J.; Su, H.; Krause, J.; Satheesh, S.; Ma, S.; Huang, Z.; Karpathy, A.; Khosla, A.; Bernstein, M.; et al. Imagenet large scale visual recognition challenge. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2015, 115, 211–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaac, A.; Haslhofer, B. Europeana linked open data (data.europeana.eu). Semant. Web 2013, 4, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, T.R. Toward principles for the design of ontologies used for knowledge sharing. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 1995, 43, 907–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guber, T. A Translational Approach to Portable Ontologies. Knowl. Acquis. 1993, 5, 199–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Wide Web Consortium. OWL 2 Web Ontology Language Document Overview; World Wide Web Consortium (W3C), Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT): Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Baader, F. The Description Logic Handbook: Theory, Implementation and Applications; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lassila, O.; Swick, R.R. Resource Description Framework (RDF) Model and Syntax Specification; World Wide Web Consortium (W3C), Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT): Cambridge, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner, A.H. Egyptian Grammar. Being an Intr. to the Study of Hieroglyphs; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Montabone, S.; Soto, A. Human detection using a mobile platform and novel features derived from a visual saliency mechanism. Image Vis. Comput. 2010, 28, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VOCUS FTS. A Visual Attention System for Object Detection and Goal Directed Search. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Bonn, Bown, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Itti, L.; Koch, C.; Niebur, E. A model of saliency-based visual attention for rapid scene analysis. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 1998, 20, 1254–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szegedy, C.; Liu, W.; Jia, Y.; Sermanet, P.; Reed, S.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Vanhoucke, V.; Rabinovich, A. Going deeper with convolutions. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Szegedy, C.; Vanhoucke, V.; Ioffe, S.; Shlens, J.; Wojna, Z. Rethinking the inception architecture for computer vision. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 2818–2826. [Google Scholar]

- Knublauch, H.; Horridge, M.; Musen, M.A.; Rector, A.L.; Stevens, R.; Drummond, N.; Lord, P.W.; Noy, N.F.; Seidenberg, J.; Wang, H. The Protege OWL Experience; OWLED: Galway, Ireland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Apache Jena Server. Apache. Available online: https://jena.apache.org/ (accessed on 11 September 2020).

- Prud’hommeaux, E.; Buil-Aranda, C. SPARQL 1.1 federated query. W3C Recomm. 2013, 21, 113. [Google Scholar]

- Noble, F.K. Comparison of OpenCV’s feature detectors and feature matchers. In Proceedings of the 2016 23rd International Conference on Mechatronics and Machine Vision in Practice (M2VIP), Nanjing, China, 28–30 November 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Merkel, D. Docker: Lightweight linux containers for consistent development and deployment. Linux J. 2014, 2014, 2. [Google Scholar]

| Institution | Data Property | Value |

|---|---|---|

| UCL_Museum | dataProvider | “UCL Museums” |

| UCL_Museum | provider | “AthenaPlus” |

| UCL_Museum | key1 | “http://purl.org/dc/elements/1.1/type” |

| UCL_Museum | key2 | “http://purl.org/dc/elements/1.1/description” |

| Institution | Assertion | Object Property | Data Properties |

|---|---|---|---|

| UCL_Museum | Has | Relation1 | relation = “http://purl.org/dc/elements/1.1/identifier” value = “id” |

| UCL_Museum | Has | Relation2 | relation = “http://purl.org/dc/elements/1.1/title” value = “title” |

| UCL_Museum | Has | Relation3 | relation = “http://purl.org/dc/elements/1.1/description” value = “description” |

| UCL_Museum | Has | Relation4 | relation = “http://purl.org/dc/terms/created” value = “creation” |

| UCL_Museum | Has | Relation6 | relation = “http://purl.org/dc/elements/1.1/type” value = “type” |

| UCL_Museum | Show | Media1 | relation = “http://www.europeana.eu/schemas/edm/isShownBy” value = “mediaURL” |

| UCL_Museum | Show | Media2 | relation = “http://www.europeana.eu/schemas/edm/isShownAt” value = “URL” |

| Ahmose | Akhenaten | Akheqa | Amen-em-hat-pa-mesha | Amen-em-ipet | Amen-em-wiya | Amen-hotep | Amen-niwt-nakht |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amenemipt | Amenemope | Amenophis II | Amenophis III (Limestone) | Amenophis III (Wood) | Anchef-en-amun | Ankh-hor | Ankh-wahibre |

| Anlamani | Apries | Artaha | Aspelta | Ast-em-khebit | Ay | Bak-en-renef | Chemay |

| Denitptah | Djed-hor | Djed-khonsu | Djed-khonsu-iwef-ankh | Djed-montu-iwef-ankh | Djed-mut | Djed-mut-iwef-ankh | Djed-ptah-iwef-ankh |

| Hatshepsut | Heka-em-saf | Hem-hotep | Henut-tawy | Henut-tawy (Queen) | Henut-wedjat | Henut-wert | Henutmehyt |

| Her-webkhet | Hor | Hor-em-heb | Hor-ir-aa | Hor-Wedja | Horkhebit | Horudja | Huy (Faience) |

| Huy (Stone) | Iset-em-Khebit | Isis | Iy-er-niwt-ef | Kemehu | Khaemweset | Khay | Maa-em-heb |

| Maatkara | Madiqan | Mahuia | Masaharta | May | Mehyt-weskhet | Merneptah | Mery-Sekhmet |

| Mut-nefret | Nakht-nes-tawy | Necho II | Nectabeno I | Nectabeno II | Nefer-hotep | Neferibre-saneith | Nefertity |

| Neferu-Ptah | Nepherites-I | Nes-Amen-em-Opet | Nes-ankhef-en-Maat | Nes-ba-neb-djed | Nes-pa-heran | Nes-pa-ka-shuty | Nes-pa-nefer-her |

| Nes-ta-hi | Nes-ta-neb-tawy | Nes-ta-nebt-Isheru | Nesy-Amun | Nesy-Khonsu | Nesy-per-nub | Osorkon II | Pa-di-Amen-nesut-tawy |

| Pa-di-hor-Mehen | Pa-di-Neith | Pa-hem-neter | Pa-her-mer | Pa-kharu | Pa-khonsu | Pa-nefer-nefer | Pa-shed-Khonsu |

| Pa-shen | Padiast | Padimayhes | Pakhaas | Pamerihu | Paser | Pashed | Pashedu |

| Pedi-Shetyt | Pen-amun | Petosiris | Pinudjem I | Pinudjem II | Psamtek | Psamtek I | Psamtek Iahmes |

| Psamtek-mery-ptah | Psusennes I (Bronze) | Psusennes I (Faience) | Qa-mut | Qenamun | Ramesses II | Ramesses III (Alabaster) | Ramesses III (Stone) |

| Ramesses III (Wood) | Ramesses IV | Ramesses IX | Ramesses VI | Ramesses-heru | Ramessu | Sa-iset | Sati |

| Sedjem-ash-Hesymeref | Senkamanisken | Sennedjem | Sety I (Faience) | Sety I (Wood) | Shed-su-Hor | Siptah | Suneru |

| Ta-shed-amun | Ta-shed-khonsu | Tabasa | Taharqa | Takelot I | Tayu-heret | Tent-Osorkon | Thutmose III |

| Thutmose IV | Tjai-hor-pa-ta | Tjai-ne-hebu | Tjai-nefer | Tjay | Tutankhamen (Faience) | Tutankhamen (Wood) | User-hat-mes |

| User-maat-re-nakht | Wahibre | Wahibre-em-kheb | Wedja-Hor | Wendjebauendjed | Yuya |

| Detected | XII | XVIII | Late XVIII | XVIII-XIX | Early XIX | XIX | XIX-XX | XX | XX-XXI | XXI | XXI-XXII | XXII | XXV | Early XXVI | XXVI | XXVI-XXX | XXIX | XXX | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Real | |||||||||||||||||||

| XII | 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| XVIII | 0.0 | 0.92 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.08 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| late XVIII | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| XVIII-XIX | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| early XIX | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| XIX | 0.0 | 0.05 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.84 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.09 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.02 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| XIX-XX | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| XX | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.22 | 0.0 | 0.67 | 0.0 | 0.11 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| XX-XXI | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| XXI | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.02 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.01 | 0.9 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.02 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| XXI-XXII | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| XXII | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.06 | 0.0 | 0.94 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| XXV | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| early XXVI | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| XXVI | 0.0 | 0.02 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.88 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.0 | |

| XXVI-XXX | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| XXIX | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 | |

| XXX | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.25 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.75 | |

| Detected | Middle Kingdom | New Kingdom | Third Intermediate Period | Late Period | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Real | |||||

| Middle Kingdom | 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| New Kingdom | 0.0 | 0.91 | 0.06 | 0.03 | |

| Third Intermediate Period | 0.0 | 0.01 | 0.97 | 0.01 | |

| Late Period | 0.0 | 0.01 | 0.0 | 0.99 | |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Duque Domingo, J.; Gómez-García-Bermejo, J.; Zalama, E. Egyptian Shabtis Identification by Means of Deep Neural Networks and Semantic Integration with Europeana. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 6408. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10186408

Duque Domingo J, Gómez-García-Bermejo J, Zalama E. Egyptian Shabtis Identification by Means of Deep Neural Networks and Semantic Integration with Europeana. Applied Sciences. 2020; 10(18):6408. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10186408

Chicago/Turabian StyleDuque Domingo, Jaime, Jaime Gómez-García-Bermejo, and Eduardo Zalama. 2020. "Egyptian Shabtis Identification by Means of Deep Neural Networks and Semantic Integration with Europeana" Applied Sciences 10, no. 18: 6408. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10186408

APA StyleDuque Domingo, J., Gómez-García-Bermejo, J., & Zalama, E. (2020). Egyptian Shabtis Identification by Means of Deep Neural Networks and Semantic Integration with Europeana. Applied Sciences, 10(18), 6408. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10186408