Diet and Oral Health Coaching Methods and Models for the Independent Elderly

Abstract

Featured Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Physical and Mental Issues of OA That Resist Change of Attitude

3. Health and Oral Health Coaching Issues

4. Positive Data on Health Coaching

5. Methodology for Behavior Change during Coaching

6. Oral Health Coaching

6.1. Oral Health Coaching Techniques and Models for OA

6.1.1. Motivational Interviewing in the Service of Senior Oral Health Coaching

OARS Model in MI

6.1.2. Other Models and Tools for Immediate Senior Oral Health Coaching

Dental PAM (Patient Activation Measure)

Tell-Show-Do

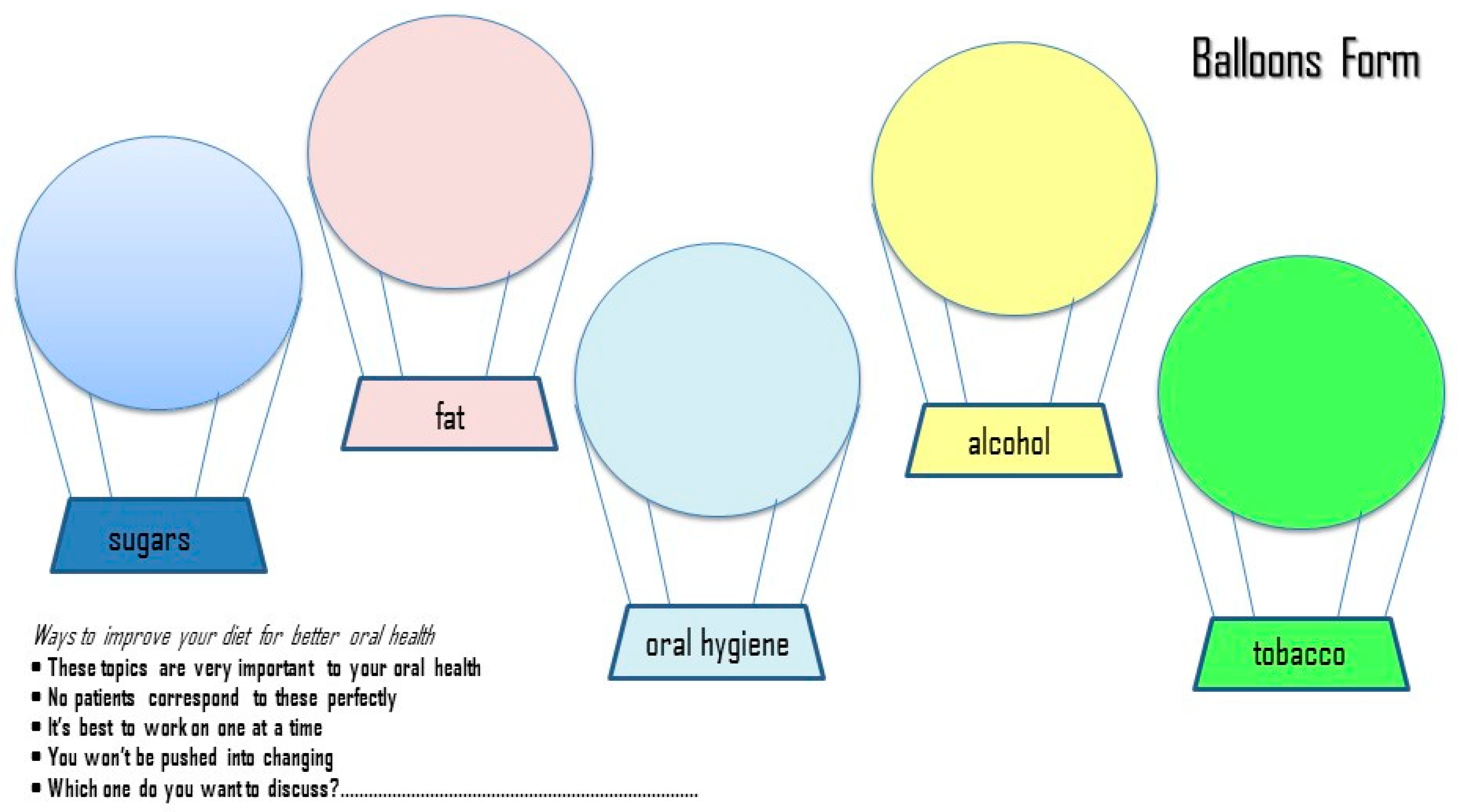

Balloons’ Diagram

Ask-Tell-Ask-Close the Loop

Rating of Change Check

Goal Setting and Action Planning

Problem-Solving Check List

Follow-Up Strategies

Laser Coaching in OA

Ask Me Three Questions Model

7. Discussion

8. Conclusions

- (1)

- There are certain mental and physical issues resisting change in habits and behavior of OA.

- (2)

- OA are more likely to benefit from a series of quick health education sessions followed by tailored feedback that is based on the absence of criticism, patience, empathy, and total acceptance by the dentist/professional coach.

- (3)

- Overcoming persistent noncompliance of OA through specific educational training can make health-behavior change one of the most rewarding and the most challenging responsibilities for dental health professionals.

- (4)

- Coaching models based on filling out forms or lists of goals, tasks, recruiting small steps, and rewarding are suggested as being more effective in OA due to their mental and physical issues.

- (5)

- Health professionals should reevaluate their role as health coaches in order to improve dietary habits and nutritional intake of the OA.

- (6)

- “Oral health coaching” will enable professionals to communicate with their senior patients in a more mentorship-based, collaborative, and inspiring way.

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Antoniadou, M.; Varzakas, T. Breaking the vicious circle of diet and oral health for the independent elderly. Appl. Sci. submitted for publication.

- Dolan, T.A.; Atchison, K.; Huynh, T.N. Access to dental care among older adults in the United States. J. Dent. Educ. 2005, 69, 961–974. [Google Scholar]

- American Society for Geriatric Dentistry. 2010. Available online: https://www.omicsonline.org/societies/american-society-for-geriatric-dentistry/ (accessed on 4 April 2020).

- Kossioni, A.; Hajto-Bryk, J.; Janssens, B.; Maggi, S.; Marchini, L.; McKenna, G.; Müller, F.; Petrovic, M.; Schimmel, M.; Roller-Wirnsberger, R.E.; et al. Practical guidelines for physicians in promoting oral health in frail older adults. J. Am. Med. Dir. Ass. 2018, 19, 1039–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Best, H. Educational systems and the continuum of care for the older adult. J. Dent. Educ. 2010, 74, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kivelä, K.; Elo, S.; Kyngäs, H.; Kääriäinen, M. The effects of health coaching on adult patients with chronic diseases: A systematic review. Patient Educ. Couns. 2014, 97, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waldrop, D.; Nochajski, T.; Davis, E.; Fabiano, J.; Goldberg, L. Empathy in dentistry: How attitudes and interaction with older adults make a difference. Gerontol. Geriatr. Educ. 2015, 37, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmer, S.; Tubbs, I.; Whybrow, A. Health coaching to facilitate promotion of health behaviour and achievement of health-related goals. Int. J. Health Promotion Educ. 2013, 41, 91–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, E.; MacCahon, C.; Panahi, M.R.; Hamre, T.; Pohlman, K. Alliance not compliance: Coaching strategies to improve type 2 diabetes outcomes. J. Am. Acad. Nurse Pract. 2008, 20, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, W.R.; Rollnick, S. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People to Change Addictive Behaviour; Guilford Press: London, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Olsen, J.M. Health Coaching: A concept analysis. Nurs. Forum 2014, 49, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Härter, M.; Dirmaier, J.; Dwinger, S.; Kriston, L.; Herbarth, L.; Siegmund-Schultze, E.; Bermejo, I.; Matschinger, H.; Heider, D.; König, H.-H.; et al. Effectiveness of telephone- based health coaching for patients with chronic conditions: A randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0161269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hale, R.; Giese, J. Cost-effectiveness of health coaching. Prof. Case Manag. 2017, 22, 228–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, C.L.; Uddin, L.Q.; Di Martino, A.; Castellanos, F.X.; Milham, M.P.; Clare, K.C. The balance between feeling and knowing: Affective and cognitive empathy are reflected in the brain’s intrinsic functional dynamics. Soc. Cogn. Affect Neurosci. 2012, 7, 727–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- May, C.; Russell, C. Health coaching: Adding value in health care reform. Clob. Adv. Health Med. 2013, 2, 92–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knowler, W.C.; Barrett-Connor, E.; Fowler, S.E.; Hamman, R.F.; Lachin, J.M.; Walker, E.A.; Nathan, D.M. For the diabetes prevention program research group. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002, 346, 393–403. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Yank, V.; Xiao, L.; Lavori, P.W.; Wilson, S.R.; Rosas, L.G.; Stafford, R.S. Translating the diabetes prevention program lifestyle intervention for weight loss into primary care: A randomized trial. JAMA Inter. Med. 2013, 173, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djuric, Z.; Segar, M.; Orizondo, C.; Mann, J.; Faison, M.; Peddireddy, N.; Paletta, M.; Locke, A. Delivery of health coaching by medical assistants in primary care. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2017, 30, 362–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boehmer, K.R.; Barakat, S.; Sangwoo, A.; Prokop, L.J.; Erwin, P.J.; Murad, H.M. Health coaching interventions for persons with chronic conditions: A systematic review and meta-analysis protocol. Sys. Rev. 2016, 5, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krok-Schoen, J.L.; Shim, R.; Nagel, R.; Lehman, J.; Myers, M.; Lucey, C.; Post, D.M. Outcomes of a health coaching intervention for older adults with uncontrolled type 2 diabetes. Gerontol. Geriatr. Educ. 2017, 38, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johansson, I.; Torgé, C.J.; Lindmark, U. Is an oral health coaching programme a way to sustain oral health for elderly people in nursing homes? A feasibility study. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2020, 18, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ICF. Available online: https://coachfederation.org/ (accessed on 13 May 2020).

- Dennis, S.M.; Harris, M.; Lloyd, J.; Davies, G.P.; Faruqi, N.; Zwar, N. Do people with existing chronic conditions benefit from health coaching? A rapid review. Aust. Health Rev. 2013, 37, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, Y.H.; Chang, H.; Kim, J.; Kwak, J.S. Patient-tailored self-management intervention for older adults with hypertension in a nursing home. J. Clin. Nurs. 2013, 22, 710–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Block, G.; Azar, K.M.; Romanelli, R.J.; Block, J.T.; Hopkins, D.; Carpenter, H.A.; Dolginsky, M.S.; Hudes, H.L.; Palaniappan, L. Diabetes prevention and weight loss with a fully automated behavioral intervention by email, web and mobile phone: A randomized controlled trial among persons with prediabetes. J. Med. Internet Res 2015, 17, e240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiede, M.; Dwinger, S.; Herbart, L.; Härter, M.; Dirmaier, J. Long-term effectiveness of telephone-based health coaching for heart failure patients: A post-only randomized controlled trial. J. Telemed. Telecare 2017, 23, 716–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dwinger, S.; Dirmaier, J.; Herbarth, L.; Konig, H.H.; Eckardt, M.; Kriston, L. Telephone-based health coaching for chronically ill patients: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2013, 14, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Diet, Nutrition, Physical Activity and Cancer: A Global Perspective. Continuous Update Project Expert Report; American Institute for Cancer Research: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fogg, J. Persuasive Technology: Using Computers to Change What We Think and Do; Morgan Kaufmann Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Leahy, T.M.; Wing, R.R. A randomized controlled pilot study testing three types of health coaches for obesity treatment: Professional, peer, and mentor. Obes. Silver Spring 2013, 21, 928–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steventon, A.; Tunkel, S.; Blunt, I.; Bardsley, M. Effect of telephone health coaching (Birmingham OwnHealth) on hospital use and associated costs: Cohort study with matched controls. BMJ 2013, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morello, R.; Barker, A.; Watts, J.; Bohensky, M.; Forbes, A.; Stoelwinder, J. A telephone support program to reduce costs and hospital admissions for patients at risk of readmission: Lessons from an evaluation of a complex intervention. Popul. Health Manag. 2016, 19, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oksman, E.; Linna, M.; Hörhammer, I.; Lammintakanen, J.; Talja, M. Cost-effectiveness analysis for a tele-based health coaching program for chronic disease in primary care. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeJesus, R.S.; Breitkopf, C.R.; Rutten, L.J.; Jacobson, D.J.; Wilson, P.M.; Sauver, J.S. Incidence rate of prediabetes progression to diabetes: Modeling an optimum target group for intervention. Popul. Health Manag. 2017, 20, 216–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmittdiel, J.A.; Adams, R.A.; Goler, N.; Sanna, R.S.; Boccio, M.; Bellamy, D.J.; Brown, D.S.; Neugebauer, R.S.; Ferrara, A. The impact of telephonic wellness coaching on weight loss: A “natural experiments for translation in diabetes (NEXT-D)” study. Obesity 2017, 25, 352–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mustonen, E.; Hörhammer, I.; Absetz, P.; Patja, K.; Lammintakanen, J.; Talja, M.; Kuronen, R.; Linna, M. Eight-year post-trial follow-up of health care and long-term care costs of tele-based health coaching. Health Serv. Res. 2020, 55, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard, B.V.; Van Horn, L.; Hsia, J.; Manson, J.E.; Stefanick, M.L.; Kuller, L.H.; Langer, R.D.; Lasser, N.L.; Levis, C.E.; Margolis, K.L.; et al. Low-fat dietary pattern and risk of cardiovascular disease: The women’s health initiative randomized controlled dietary modification trial. JAMA 2006, 295, 655–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knowler, W.; Fowler, S.; Hamman, R.; Christophi, C.; Hoffman, H.; Brenneman, A.; Brown-Friday, J.; Goldberg, R.; Venditti, E.; David, M.; et al. Diabetes prevention program research group. 10-year follow-up of diabetes incidence and weight loss in the diabetes prevention program outcomes study. Lancet 2009, 374, 1677–1686. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wadden, T.A.; West, D.S.; Neiberg, R.H.; Wing, R.R.; Ryan, D.H.; Johnson, K.C.; Look AHEAD Research Group. One-year weight losses in the Look AHEAD study: Factors associated with success. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2009, 17, 713–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rock, C.L.; Doyle, C.; Demark-Wahnefried, W.; Meyerhardt, J.; Courneya, K.S.; Schwartz, A.L.; Byers, T.; Gansler, T.; Hamilton, K.K.; Bandera, E.V.; et al. Nutrition and physical activity guidelines for cancer survivors. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2012, 62, 242–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mcbride, C.M.; Clipp, E.; Peterson, B.L.; Lipkus, I.M.; Demark-Wahnefried, W. Psychological impact of diagnosis and risk reduction among cancer survivors. Psychooncology 2000, 9, 418–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demark-Wahnefried, W.; Peterson, B.; McBride, C.; Lipkus, I.; Clipp, E. Current health behaviors and readiness to pursue life-style changes among men and women diagnosed with early stage prostate and breast carcinomas. Cancer 2000, 88, 674–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coups, E.J.; Ostroff, J.S. A population-based estimate of the prevalence of behavioral risk factors among adult cancer survivors and noncancer controls. Prev. Med. 2005, 40, 702–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanchard, C.M.; Courneya, K.S.; Stein, K. American Cancer Society’s SCS-II. Cancer survivors’ adherence to lifestyle behavior recommendations and associations with health-related quality of life: Results from the American Cancer Society’s SCS-II. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008, 26, 2198–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimmons, J.; Gillespie, G.; Seymour, J.; Serdula, M.; Blanck, H.M. Fruit and vegetable intake among adolescents and adults in the United States: Percentage meeting individualized recommendations. Medscape. J. Med. 2009, 11, 26. [Google Scholar]

- Inoue-Choi, M.; Robien, K.; Lazovich, D. Adherence to the WCRF/AICR guidelines for cancer prevention is associated with lower mortality among older female cancer survivors. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2013, 22, 792–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellizzi, K.M.; Rowland, J.H.; Jeffery, D.D.; McNeel, T. Health behaviors of cancer survivors: Examining opportunities for cancer control intervention. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005, 23, 8884–8893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LeMasters, T.J.; Madhavan, S.S.; Sambamoorthi, U.; Kurian, S. Health behaviors among breast, prostate, and colorectal cancer survivors: A US population-based case-control study, with comparisons by cancer type and gender. J. Cancer Surviv. 2014, 8, 336–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tollosa, D.N.; Tavener, M.; Hure, A.; James, E.L. Adherence to multiple health behaviours in cancer survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Cancer Surviv. 2019, 13, 327–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koutoukidis, D.A.; Lopes, S.; Fisher, A.; Williams, K.; Croker, H.; Beeken, R.J.; Winkler, M.; Hall, R.; Simon, M.; Merkel, D. Lifestyle advice to cancer survivors: A qualitative study on the perspectives of health professionals. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e020313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chlebowski, R.T.; Blackburn, G.L.; Thomson, C.A.; Nixon, D.W.; Shapiro, A.; Hoy, M.K.; Goodman, M.T.; Giuliano, A.E.; Karanja, N.; McAndrew, P.; et al. Dietary fat reduction and breast cancer outcome: Interim efficacy results from the Women’s Intervention Nutrition Study. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2006, 98, 1767–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierce, J.P.; Stefanick, M.L.; Flatt, S.W.; Natarajan, L.; Sternfeld, B.; Madlensky, L.; Parker, B.A.; Newman, V.A.; Rock, C.L.; Caan, B.; et al. Greater survival after breast cancer in physically active women with high vegetable-fruit intake regardless of obesity. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007, 25, 2345–2351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kima, Μ.Τ.; Kimb, K.B.; Nguyenc, T.H.; Koa, J.; Zaborad, J.; Jacobse, E.; Levinef, D. Motivating people to sustain healthy lifestyles using persuasive technology: A pilot study of Korean Americans with prediabetes and type 2 diabetes. Patient. Educ. Couns. 2019, 102, 709–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiMatteo, M.R.; Giordani, P.J.; Lepper, H.S.; Croghan, T.W. Patient adherence and medical treatment outcomes: A meta-analysis. Med. Care 2002, 40, 794–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fishbein, M. The role of theory in HIV prevention. Aids Care 2000, 12, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Margolius, D.; Bodenheimer, T.; Bennett, H.; Wong, J.; Ngo, V.; Padilla, G.; Thom, D.H. Health coaching to improve hypertension treatment in a low-income, minority population. Ann. Fam. Med. 2012, 10, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.S.; O’Connor, E.A.; Evans, C.V.; Senger, C.A.; Rowland, M.G.; Groom, H.C. Behavioral counseling to promote a healthy lifestyle for cardiovascular disease prevention in persons with cardiovascular risk factors: An updated systematic evidence review for the U.S. Preventive Services. Task Force. In Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); Report No. 13-05179-EF-1.36; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Isola, G.; Alibrandi, A.; Rapisarda, E.; Matarese, G.; Williams, R.C.; Leonardi, R. Association of vitamin D in patients with periodontitis: A cross-sectional study. J. Perodontal. Res. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willard-Grace, R.; Chen, E.H.; Hessler, D.; DeVore, D.; Prado, C.; Bodenheimer, T.; Thom, D.H. Health coaching by medical assistants to improve control of diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia in low-income patients: A randomized controlled trial. Ann. Fam. Med. 2015, 13, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isola, G.; Matarese, G.; Ramaglia, L.; Pendullà, E.; Rapisarda, E.; Iorio-Siciliano, V. Association between periodontitis and glycosylated haemoglobin before diabetes onset: A cross-sectional study. Clin. Oral Investig. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, Y.H.; Chang, H.K. Effect of a health coaching self-management program for older adults with multimorbidity in nursing homes. Patient Prefer. Adher. 2014, 8, 959–970. [Google Scholar]

- Wong-Rieger, D.; Rieger, F.P. Health coaching in diabetes: Empowering patients to self-manage. Can. J. Diabetes 2013, 37, 41–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benzo, R.P.; Abascal-Bolado, B.; Dulohery, M.M. Self-management and quality of life in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): The mediating effects of positive affect. Patient Educ. Couns. 2016, 99, 617–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olsen, J.M.; Nesbitt, B.J. Health coaching to improve healthy lifestyle behaviors: An integrative review. Am. J. Health Promot. 2010, 25, e1–e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, M.M.; Bradley, K.L.; Jenkins, S.M.; Mettler, E.A.; Larson, B.G.; Preston, H.R.; Riley, B.A.; Olsen, K.D.; Douglas, K.S.V.; Hagen, P.T.; et al. The effectiveness of wellness coaching for improving quality of life. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2014, 89, 1537–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, M.M.; Bradley, K.L.; Jenkins, S.M.; Mettler, E.A.; Larson, B.G.; Preston, H.R.; Riley, B.A.; Olsen, K.D.; Douglas, K.S.V.; Hagen, P.T.; et al. Improvement in health behaviors, eating self-efficacy and goal-setting skills following participation in wellness coaching. Am. J. Health Promot. 2016, 30, 458–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liddy, C.; Johnston, S.; Nash, K.; Ward, N.; Irving, H. Health coaching in primary care: A feasibility model for diabetes care. BMC Fam. Pract. 2014, 15, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neuner-Jehle, S.; Schmid, J.; Gruninger, U. The health coaching programme: A new patient-centered and visually supported approach for health behavior change in primary care. BMC Fam. Pract. 2013, 14, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, M.A.; Brett, C.E.; Johnson, W.; Deary, I.J. Personality Stability From Age 14 to Age 77 Years. Psychol. Aging 2016, 31, 862–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arends, J.; Bachmann, P.; Baracos, V.; Barthelemy, N.; Bertz, H.; Bozzetti, F.; Krznaric, Z.; Larson, M.; Ravasco, P.; Laviano, A.; et al. ESPEN guidelines on nutrition in cancer patients. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 36, 11–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stacey, F.G.; James, E.L.; Chapman, K.; Courneya, K.S.; Lubans, D.R. A systematic review and meta-analysis of social cognitive theory-based physical activity and/or nutrition behavior change interventions for cancer survivors. J. Cancer Surviv. 2015, 9, 305–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glanz, K.; Bishop, D.B. The role of behavioral science theory in development and implementation of public health interventions. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2010, 31, 399–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michie, S.; Wood, C.E.; Johnston, M.; Abraham, C.; Francis, J.; Hardeman, W. Behaviour change techniques: The development and evaluation of a taxonomic method for reporting and describing behaviour change interventions (a suite of five studies involving consensus methods, randomised controlled trials and analysis of qualitative data). Health Technol. Assess 2015, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Playdon, M.; Thomas, G.; Sanft, T.; Harrigan, M.; Ligibel, J.; Irwin, M. Weight loss intervention for breast cancer survivors: A systematic review. Curr. Breast Cancer Rep. 2013, 5, 222–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoedjes, M.; de Kruif, A.; Mols, F.; Bours, M.; Beijer, S.; Winkels, R.; Westerman, M.J.; Seidell, J.C.; Kampman, E. An exploration of needs and preferences for dietary support in colorectal cancer survivors: A mixed-methods study. PLoS ONE 2017, 8, e0189178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social cognitive theory of self-regulation. Organiz. Behav. Hum. Dec. Proc. 1991, 50, 248–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, L.G.; Wasson, J.H. The ideal medical practice model: Improving efficiency, quality and the doctor-patient relationship. Fam. Pr. Manag. 2007, 14, 20–24. [Google Scholar]

- Trappenburg, J.; Jonkman, N.; Jaarsma, T.; van Os-Medendorp, H.; Kort, H.; de Wit, N.; Hoeas, A.; Schuurmans, M. Self-management: One size does not fit all. Patient Educ. Couns. 2013, 92, 134–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thom, D.H.; Hessler, D.; Willard-Grace, T.R.; Bodenheimer, A.; Najmabadi, C.; Araujo, E.; Chen, H. Does health coaching change patients’ trust in their primary care provider? Patient Educ. Couns. 2014, 96, 135–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Position Paper. Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Total Diet Approach to Healthy Eating. 2011. Available online: https://jandonline.org/article/S2212-2672 (accessed on 4 April 2020).

- Lorig, K.R.; Sobel, D.S.; Stewart, A.L.; Brown, B.W., Jr.; Bandura, A.; Ritter, P.; Holman, H.R.; Ritter, P. Evidence suggesting that a chronic disease self-management program can improve health status while reducing hospitalization: A randomized trial. Med. Care 1999, 37, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norris, S.L.; Lau, J.; Smith, S.J.; Schmid, C.H.; Engelgau, M.M. Self-management education for adults with type 2 diabetes: A meta-analysis of the effect on glycemic control. Diabetes Care 2002, 25, 1159–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeJesus, R.S.; Clark, M.M.; Finney Rutten, L.J.; Jacobson, R.M.; Croghan, I.T.; Wilson, P.M.; Jacobson, D.J.; Link, S.M.; Fan, C.; Sauver., J.L.S. Impact of a 12-week wellness coaching on self-care behaviors among primary care adult patients with prediabetes. Prev. Med. Rep. 2018, 10, 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berg, J.; Tichacek, M.J.; Theodorakis, R. Evaluation of an educational program for adolescents with asthma. J. Sch. Nurs. 2004, 20, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, E.; Karen, K.A. From the sidelines: Coaching as a nurse practitioner strategy for improving health outcomes. J. Am. Acad. Nurse Pr. 2007, 19, 555–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marks, R.; Allegrante, J.P.; Lorig, K. A review and synthesis of research evidence for self-efficacy-enhancing interventions for reducing chronic disability: Implications for health education practice (part II). Health Promot. Pract. 2005, 6, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiClemente, R.J. Planning models are critical for facilitating the development, implementation, and evaluation of dental health promotion interventions. J. Public Health Dent. 2011, 71 (Suppl. 1), S16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Birtwhistle, R.V.; Godwin, M.S.; Delva, M.D.; Casson, R.I.; Lam, M.; MacDonald, S.E.; Rühland, L.; Seguin, R. Randomised equivalence trial comparing three month and six month follow up of patients with hypertension by family practitioners. BMJ 2004, 328, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hojat, M. (Ed.) Empathy in Patient Care: Antecedents, Development, Measurement and Outcomes; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hojat, M. Ten approaches for enhancing empathy in health and human services cultures. J. Health Hum. Serv. Admin. 2009, 31, 412–450. [Google Scholar]

- Hojat, M.; Vergare, M.J.; Maxwell, K.; Brainard, G.; Herrine, S.K.; Isenberg, G.A.; Gonnella, J.S. The devil is in the third year: A longitudinal study of erosion of empathy in medical school. Acad. Med. 2009, 84, 1182–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hojat, M.; Louis, D.Z.; Markham, F.W.; Wender, R.; Rabinowitz, C.; Gonnella, J.S. Physicians’ empathy and clinical outcomes for diabetic patients. Acad. Med. 2011, 86, 359–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hojat, M.; Mangione, S.; Gonnella, J.S.; Nasca, T.; Veloski, J.J.; Kane, G. Empathy in medical education and patient care. Acad. Med. 2001, 76, 669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherman, J.J.; Cramer, A. Measurement of changes in empathy during dental school. J. Dent. Educ. 2005, 69, 338–345. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fabiano, J.A.; Waldrop, D.P.; Nochajski, T.H.; Davis, E.L.; Goldberg, L.J. Understanding dental students’ knowledge and perceptions of older people: Toward a new model of geriatric dental education. J. Dent. Educ. 2005, 69, 419–433. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Waldrop, D.P.; Fabiano, J.A.; Nochajski, T.H.; Zittel-Palamara, K.; Davis, E.L.; Goldberg, L.J. More than a set of teeth: Assessing and enhancing dental students’ perceptions of older adults. Geront. Geriatr. Educ. 2006, 27, 37–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nochajski, T.; Davis, E.; Waldrop, D.; Fabiano, J.; Goldberg, L. Dental students’ attitudes about older adults: Do type and amount of contact make a difference? J. Dent. Educ. 2011, 75, 1329–1332. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vernon, L.T.; Howard, A.R. Advancing health promotion in Dentistry: Articulating an integrative approach to coaching oral health behavior change in the dental setting. Curr. Oral. Health Rep. 2015, 2, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orji, R.; Vassileva, J.; Mandryk, R.L. Modeling the efficacy of persuasive strategies for different gamer types in serious games for health, User Model. User Adapt. Interact. 2014, 24, 453–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, A.R. Coaching to vision versus coaching to improvement needs: A preliminary investigation on the differential impacts of fostering positive and negative emotion during real time coaching sessions. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Wagner, T.; Willard-Grace, R.; Chen, E.; Bodenheimer, T.; Thom, D. Costs of a health coaching intervention for chronic care management. Am. J. Manag. Care 2016, 22, e141–e146. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Carey, J.A.; Madill, A.; Manogue, M. Communications skills in dental education: A systematic research review. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2010, 14, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, T.C.; Wilson, N.C.; Singh, P.P.; Lemanu, D.P.; Hawken, S.J.; Hill, A.G. Medical students-as-teachers: A systematic review of peer-assisted teaching during medical school. Adv. Med. Educ. Pr. 2011, 2, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, J.; Arteaga, S.; D’Ambrosio, J.; Hodge, C.; Ioannidou, E.; Pfeiffer, C.A.; Reisine, S. Dental students’ attitudes toward treating diverse patients: Effects of a cross-cultural patient-instructor program. J. Dent. Educ. 2008, 72, 1128–1134. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gordon, N.F.; Salmon, R.D.; Wright, B.S.; Faircloth, G.C.; Reid, K.S.; Gordon, T.L. Clinical effectiveness of lifestyle health coaching. Case study of an evidence-based program. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2017, 11, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levinson, W.; Kao, A.; Kuby, A.; Thisted, R. Not all patients want to participate in decision making. A National Study of Public Preferences. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2005, 20, 531–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheerman, J.F.M.; van Meijel, B.; van Empelen, P.; Verrips, G.H.W.; van Loveren, C.; Twisk, J.W.R.; Pakpour, A.H.; van den Braak, M.C.T.; Kramer, G.J.C. The effect of using a mobile application (“WhiteTeeth”) on improving oral hygiene: A randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2020, 18, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yarnall, A.J.; Breen, D.P.; Duncan, G.W.; Khoo, T.K.; Coleman, S.Y.; Firbank, M.J.; Nombela, C.; Winder-Rhodes, S.; Evans, J.R.; Rowe, J.B.; et al. Characterizing mild cognitive impairment in incident Parkinson disease: The ICICLE-PD study. Neurology 2014, 82, 308–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glanz, K.; Rimer, B.K.; Viswanath, K. (Eds.) Chapter 2: Theory, research and practice in health behavior and health education. In Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research and Practice, 4th ed.; Jossey-Bass–A Wiley Imprint: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Rothman, A.J. Is there nothing more practical than a good theory? Why innovations and advances in health behavior change will arise if interventions are used to test and refine theory. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2004, 1, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riddle, M.; Clark, D. Behavioral and social intervention research at the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR). J. Public Health Dent. 2011, 71 (Suppl. 1), S123–S129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartholomew, L.K.; Mullen, P.D. Five roles for using theory and evidence in the design and testing of behavior change interventions. J. Public Health Dent. 2011, 71 (Suppl. 1), S20–S33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McAllister, A.L.; Perry, C.L.; Parcel, C.S. Chapter 8: How individuals, environments and health behaviors interact: Social cognitive theory. In Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research and Practice, 4th ed.; Glanz, K., Ed.; Jossey-Bass–A Wiley Imprint: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Champion, V.L.; Skinner, C.S. Chapter 3: The health belief model. In Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research and Practice, Glanz, K., Ed.; Jossey-Bass–A Wiley Imprint: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Montano, D.E.; Kasprzyk, D. Chapter 4: Theory of reasoned action, theory of planned behavior, and the integrated behavioral model. In Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research and Practice; Glanz, K., Ed.; Jossey-Bass–A Wiley Imprint: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein, N.D.; Sandman, P.M.; Blalock, S.J. Chapter 6. The precaution adoption process model. In Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research and Practice, 4th ed.; Glanz, K., Ed.; Jossey-Bass–A Wiley Imprint: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Chapple, I.L.C.; Hill, K. Getting the message across to periodontitis patients: The role of personalized biofeedback. Int. Dent. J. 2008, 58, 294–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prochaska, J.O.; Velicer, W.F. The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. Am. J. Health Promot. 1997, 12, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fishbein, M.; Capella, J.N. The role of theory in developing effective health communications. J. Commun. 2006, 56, S1–S17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A.; McClelland, D.C. Social Learning Theory; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Ramseier, C.; Suvan, J. Health Behavior Change in the Dental Practice; Wiley & Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman-Novakofski, K.; Karduck, J. Improvement in knowledge, social cognitive theory variables, and movement through stages of change after a community-based diabetes education program. J. Am. Diet Assoc. 2005, 105, 1613–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Noia, J.; Prochaska, J. Mediating variables in a Transtheoretical model dietary intervention program. Health Educ. Behav. 2009, 37, 753–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brug, J.; Conner, M.; Harre, N.; Kremers, S.; McKellar, S.; Whitelaw, S. The Transtheoretical Model and stages of change: A critique observations by five commentators on the paper by Adams, J. and White, M. (2004) why don’t stage-based activity promotion interventions work? Health Educ. Res. 2005, 20, 244–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenlee, H.; Santiago-Torres, M.; McMillen, K.K.; Ueland, K.; Haase, A.M. Helping patients eat better during and beyond cancer treatment continued nutrition management throughout care to address diet, malnutrition, and obesity in cancer. Cancer J. 2019, 25, 320–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inglehart, M.; Tedesco, L.A. Behavioral research related to oral hygiene Practices: A new century model of oral helath promotion. Periodontol. 2000 1995, 8, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fortheringham, M.J.; Owies, D.; Leslie, E.; Owen, N. Interactive health communication in preventive medicine: Internet-based strategies in teaching and research. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2000, 19, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brukiene, V.; Aleksejūniene, J. An overview of oral health promotion in adolescents. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2009, 19, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoham, V.; Insel, T.R. Rebooting for whom? Portfolios, technology, and personalized interventions. Assoc. Psychol. Sci. 2011, 6, 478–482. [Google Scholar]

- Yevlahova, D.; Satur, J. Models for individual oral health promotion and their effectiveness: A systematic review. Aust. Dent. J. 2009, 54, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simmons, L.A.; Wolever, R.Q.; Bechard, E.M.; Snyderman, R. Patient engagement as a risk factor in personalized health care: A systematic review of the literature on chronic disease. Genome. Med. 2014, 6, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ismail, A.I.; Ondersma, S.; Willem Jedele, J.M.; Little, R.J.; Lepkowski, J.M. Evaluation of a brief tailored motivational intervention to prevent early childhood caries. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2011, 39, 433–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peacock, S.; Konrad, S.; Watson, E.; Nickel, D.; Muhajarine, N. Effectiveness of home visiting programs on child outcomes: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jönsson, B.; Ohrn, K.; Oscarson, N. The effectiveness of an individually tailored oral health educational programme on oral hygiene behaviour in patients with periodontal disease: A blinded randomized-controlled clinical trial (one-year follow-up). J. Clin. Periodontol. 2009, 36, 1025–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Association for Coaching. The Global Code of Ethics. Available online: https://www.associationforcoaching.com/page/AboutCodeEthics (accessed on 25 March 2020).

- MacGregor, K.; Handley, M.; Wong, S.; Sharifi, C.; Gjeltema, K.; Schillinger, D.; Bodenheimer, T. Behavior-change action plans in primary care: A feasibility study of clinicians. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2006, 19, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, S. Rational coaching: A cognitive behavioural approach. The coaching psychologist 2009, 5, 12–18. [Google Scholar]

- Simmons, L.A.; Wolever, R.Q. Integrative health coaching and motivational interviewing: Synergistic approaches to behavior change in healthcare. Glob. Adv. Health Med. 2013, 2, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, R.; Rollnick, S. (Eds.) Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People for Change, 2nd ed.; The Guilford Press: Guilford, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Rollnick, S.; Miller, W.R.; Butler, C. Motivational Interviewing in Healthcare: Helping Patients Change Behaviour; Guilford Press: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Huffman, M.H. Health coaching: A fresh, new approach to improve quality outcomes and compliance for patients with chronic conditions. Home Healthc. Nurse. 2009, 27, 490–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antoniadou, M. Delivering health outcomes using the patient activation measure method-Prospects for the dentistry field. Adv. Dent. Oral Health 2020, 12, 5558333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s New Health Partnerships Web Site. Available online: http://www.newhealthpartnerships.org/. (accessed on 2 April 2020).

- Asimakopoulou, B. Human Resources Expertise, Coaching Skills & Tools in Practice: Athens, Greece, Unpublished data. 2020.

- Stott, N.C.; Rollnick, S.; Rees, M.R.; Pill, R.M. Innovation in clinical method: Diabetes care and negotiating skills. Fam Pr. 1995, 12, 413–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schillinger, D.; Piette, J.; Grumbach, K.; Wang, F.; Wilson, C.; Daher, C.; Leong-Grotz, K.; Castro, C.; Bindman, A.B. Closing the loop: Physician communication with diabetic patients who have low health literacy. Arch. Intern. Med. 2003, 163, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wasson, J.; Hays, R.; Rubenstein, L.; Nelson, E.; Leaning, J.; Johnson, D.; Rosenkrans, C.; Landgraf, J. The short-term effect of patient health status assessment in a health maintenance organization. Qual. Life Res. 1992, 1, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeBusk, R.F.; Miller, N.H.; Superko, H.R.; Dennis, C.A.; Thomas, R.J.; Lew, H.T.; Berger, W.E., III; Heller, R.S.; Rompf, J.; Gee, D.; et al. A case-management system for coronary risk factor modification after acute myocardial infarction. Ann. Intern. Med. 1994, 120, 721–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinberger, M.; Kirkman, M.S.; Samsa, G.P.; Shortliffe, E.A.; Landsman, P.B.; Cowper, P.A.; Simel, D.L.; Feussner, J.R. A nurse-coordinated intervention for primary care patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus: Impact on glycemic control and health-related quality of life. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 1995, 10, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikolaidou, E. Laser Coaching Model; Moving Minds PC ed, Athens, Greece, Unpublished data. 2020.

- Michalopoulou, G.; Falzarano, P.; Arfken, C.; Rosenberg, D. Implementing Ask Me 3 to improve African American patient satisfaction and perceptions of physician cultural competency. J. Cult. Divers. 2010, 17, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Stenman, J.; Lundgren, J.; Wennström, J.L.; Ericsson, J.S.; Abrahamsson, K.H. A single session of motivational interviewing as an additive means to improve adherence in periodontal infection control: A randomized controlled trial. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2012, 39, 947–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butterworth, S.W. Influencing patient adherence to treatment guidelines. J. Manag. Care Pharm. 2008, 14 Suppl. B), 21–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, L.M.; Ziegelmann, J.P.; Schüz, B.; Wurm, S.; Tesch-Römer, C.; Schwarzer, R. Maintaining autonomy despite multimorbidity: Self-efficacy and the two faces of social support. Eur. J. Ageing 2011, 8, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffin, S.J.; Kinmonth, A.L.; Veltman, M.W.; Gillard, S.; Grant, J.; Stewart, M. Effect on health-related outcomes of interventions to alter the interaction between patients and practitioners: A systematic review of trials. Ann. Fam. Med. 2004, 2, 595–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simmons, L.; Baker, N.J.; Schaefer, J.; Miller, D.; Anders, S. Activation of patients for successful self-management. J. Ambulat. Care Manag. 2009, 32, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roter, D.; Hall, J. Studies of Doctor-patient Interaction. Ann. Rev. Public Health 1989, 10, 163–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safeer, R.S.; Keenan, J. Health literacy: The gap between physicians and patients. Am. Fam. Physician 2005, 72, 463–468. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tarn, D.M.; Heritage, J.; Paterniti, D.A.; Hays, R.D.; Kravitz, R.L.; Wenger, N.S. Physician communication when prescribing new medications. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1855–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Locker, D.; Jokovic, A.; Tompson, B. Health-related quality of life of children aged 11 to 14 years with orofacial conditions. Cleft Palate Craniofac. J. 2005, 42, 260–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mason, J.; Pearce, M.S.; Walls, A.W.; Parker, L.; Steele, J.G. How do factors at different stages of the life course contribute to oral-health-related quality of life in middle age for men and women? J. Dent. Res. 2006, 85, 257–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitlock, E.; Ensaff, H. On your own: Older adults’ food choice and dietary habits. Nutrients 2018, 10, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics 2012. Older Americans 2012: Key Indicators of well-being. Available online: http://www.agingstats.gov/agingstatsdotnet/Main_Site/Data/2012_Documents/Docs/EntireChartbook.pdf (accessed on 27 March 2020).

- Tsakos, G. Inequalities in oral health of the elderly: Rising to the public health challenge? J. Dent. Res. 2011, 90, 689–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hojat, M.; Gonnella, J.S.; Nasca, T.J.; Mangione, S.; Vergare, M.; Magee, M. Physician empathy: Definition, components, measurement, and relationship to gender and specialty. Am. J. Psychiatry 2002, 159, 1563–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Physical and Mental Issues of OA | Symptoms | Results |

|---|---|---|

| Memory lapses or forgetfulness | Memory loss, language difficulty, poor judgment, absence of communication, problems concentrating impaired visual perception | Bad relationships Accidents Need of repetition Loss of orientation |

| Low mood or depression | Changes in sleep, appetite, energy level, denial and difficulty in oral and body hygiene | Unsocialized behavior, isolation, denial, estrangement from family |

| Sudden changes in mood | Apathy, confusion, agitation, fear, anger, breakdown | Difficulty or denial in supporting one’s needs Social/role limiting |

| Discouragement or anger | Emotional or verbal abuse | Feeling of loneliness and fatality |

| Decline in short memory | Longer period of learning, Lengthening of response time Repetitive questioning | Loss of information, neglect of basic survival habits |

| Low resilience to pain and death | Lack of social life, estrangement from family, eating by oneself, loss of smiling and talking, loneliness | No visits to doctors & dentists, uncontrolled systematic diseases, high stress, bad oral health, anorexia |

| Lack of cooking skills and physical impairment | Difficulty in getting foods, eating only snacks | Malnutrition, bad oral hygiene |

| Loss of economic independence | Frustration, fear of the near future | Poverty, difficulty in getting foods, no access to health services |

| Recommendations for OA during Health Coaching | |

|---|---|

| 1 | Know how and when to call for help |

| 2 | Learn about the condition and set goals |

| 3 | Take medicines/nutrients correctly |

| 4 | Get recommended tests and services |

| 5 | Act to keep the condition well controlled |

| 6 | Make lifestyle changes and reduce risks |

| 7 | Build on strengths and overcome obstacles |

| 8 | Follow-up with specialists and appointments |

| Model | Method | Type of OA | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| OARS | Open-ended questions, affirmations, reflections, summary | OA who like talking and communicating with others | Discovery of goals, clarification of wishes, acknowledgement of contradictions, strengthening patient’ own motivation |

| Dental PAM | 13-questions Questionnaire | Ambivalent, fearful, uncertain, reluctant to change, untrusting OA | Evaluation of knowledge, skills and confidence Stratification of patients according to activation level |

| Tell-Show-Do | 3 simple and quick steps: share information, show how to do it, let patient do it | OA with physical impairments or with short memory loss | Quick evaluation of perceived information, achieving results through often repetition and exercise |

| Balloons Diagram | Balloons form | OA with hearing or other physical difficulties, optical way of learning | Sudden realization, visualization, metaphorical release of problematic situations and habits |

| Ask-Tell-Ask-Close the Loop | Ask for permission, give information through written materials, brochures, etc., ask for understanding and rephrase goals | OA with sensitivities, depression, negative feelings, isolated, strong-minded, unwilling to accept age impairments | Specification of goals, feeling trusted and accepted |

| Rating of Change Check | Change Check List | OA who likes numbers and numerology | Determination for achieving small steps, summarization of change |

| Goal setting and Action Planning | Action Planning Form | OA who still can write, with good vision but memory loss, those who like order and organization | Stratification and empowerment of goals, strengthening of motivation |

| Problem Solving | Problem-Solving Check List | Impatient, stressed, economic dependent OA | Lower guilty behavior and stress |

| Follow-ups | Follow-up Check List | Lonely OA with memory loss or fear of incompetence | Self-acceptance and lower stress |

| Laser Coaching | Short, compact communication based on reward | For OA who need recompense and like prizes, bonus, presents and gifts | Giving responsibility, feelings of self-realization and value |

| Ask-Me-3-Questions | The patient makes the questions and the answers | For reluctant OA | Accountability |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Antoniadou, M.; Varzakas, T. Diet and Oral Health Coaching Methods and Models for the Independent Elderly. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 4021. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10114021

Antoniadou M, Varzakas T. Diet and Oral Health Coaching Methods and Models for the Independent Elderly. Applied Sciences. 2020; 10(11):4021. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10114021

Chicago/Turabian StyleAntoniadou, Maria, and Theodoros Varzakas. 2020. "Diet and Oral Health Coaching Methods and Models for the Independent Elderly" Applied Sciences 10, no. 11: 4021. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10114021

APA StyleAntoniadou, M., & Varzakas, T. (2020). Diet and Oral Health Coaching Methods and Models for the Independent Elderly. Applied Sciences, 10(11), 4021. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10114021