Abstract

This study proposes an integrated deep network consisting of a detection and identification module for person search. Person search is a very challenging problem because of the large appearance variation caused by occlusion, background clutter, pose variations, etc., and it is still an active research issue in the academic and industrial fields. Although various studies have been proposed, following the protocols of the person re-identification (ReID) benchmarks, most existing works take cropped pedestrian images either from manual labelling or a perfect detection assumption. However, for person search, manual processing is unavailable in practical applications, thereby causing a gap between the ReID problem setting and practical applications. One fact is also ignored: an imperfect auto-detected bounding box or misalignment is inevitable. We design herein a framework for the practical surveillance scenarios in which the scene images are captured. For person search, detection is a necessary step before ReID, and previous studies have shown that the precision of detection results has an influence on person ReID. The detection module based on the Faster R-CNN is used to detect persons in a scene image. For identifying and extracting discriminative features, a multi-class CNN network is trained with the auto-detected bounding boxes from the detection module, instead of the manually cropped data. The distance metric is then learned from the discriminative features output by the identification module. According to the experimental results of the test performed in the scene images, the multi-class CNN network for the identification module can provide a 62.7% accuracy rate, which is higher than that for the two-class CNN network.

1. Introduction

With the rapid development of information technology, security and surveillance systems have been installed in many places, including schools, department stores, train stations, airports, office buildings and so on, for public safety. Cameras are usually installed with non-overlap views to increase the security area and strike a balance between equipment cost and security. From the view of the data mining field, surveillance intelligence can be seen from the sequential data (videos) [1,2,3] and abnormal or specific patterns can be found; e.g., vehicle, pedestrian. Several subjects (e.g., abnormal event detection, object detection, tracking, face recognition, and person re-identification) have been explored in computer vision [4,5,6]. Person search plays an important role in the intelligent surveillance system, which was first introduced in [7]. Xu et al. [7] proposed a sliding window searching strategy based on person detection and person matching scores to find a person’s image captured by one camera (i.e., probe image) in a gallery of scene images [8,9], where probe and gallery images are captured with different viewpoints.

Person search is an extended form of person re-identification (person ReID) and is designed to find a probe person in a gallery of scene images. Large visual variations caused by changes in illumination, occlusion, background clutter, different viewpoints, and human poses pose a challenging problem [8,9]. Large intra-class variations, which include different appearances, increase the difficulty of feature representation. Besides this, the class imbalance problem is a problem in machine learning; i.e., the amount of data for one class is far less than the amount of data for another class [10]. Person search has the imbalance problem of having a set of “different” pairs (i.e., a combination of two images from different persons) while having a limited set of “same” pairs (i.e., a combination of two images from the same person). The similarity measurement is therefore difficult to learn, and data sampling techniques are often utilized during the training process [11,12]. Existing research can be roughly divided into two categories for person re-identification. One extracts the discriminative feature for a person’s image [13,14], while the other learns the metric with a form of a matrix to measure the similarity [15] between persons’ images. With the great success achieved by the deep learning network in computer vision [16,17,18], some works have recently been proposed to address person ReID with deep learning networks in an end-to-end architecture, which refers to giving input data and, with the desired output label, a system is automatically trained as a whole [19]. Three kinds of deep models are used in person ReID: Siamese networks [13,15,20], classification networks [21,22,23], and triplet networks [24,25]. Additionally, many works have focused on coping with specific issues, such as occlusion [26], misalignment [27,28,29] and over-fitting [19,23,30,31].

Although numerous works have been proposed for person ReID, the gallery or probe pedestrian images are manually cropped in most benchmarks [13,32,33,34]. Following the protocols of these benchmarks, most existing works have taken cropped pedestrian images either from manual labelling or a perfect detection assumption [9]. However, in practical applications, manual processing is time consuming and unavailable, thereby causing a gap between person ReID and practical applications [9]. Although the performance of pedestrian detection by deep learning models such as the Faster R-CNN [35], Single Shot MultiBox Detector (SSD) [36] and Person of Interest [37] is significantly better than the traditional method [38], imperfect bounding boxes, background clutter, misdetections, misalignment or false alarms are inevitable. In other words, the detection results affect the person ReID; however, most studies consider pedestrian detection and person ReID as separate issues [9]. The person search method has recently been introduced to close the gap. Person search is more challenging than person ReID because of the imprecise detection cropping and misalignment [8,9]. In 2017, Xiao et al. [9] proposed a deep learning framework to jointly optimize pedestrian detection and person ReID in a single convolutional neural network (CNN). An online instance matching loss function has been proposed to train the network. Liu et al. [39] proposed a neural search model to recursively refine the location of the target person in the scene. In 2018, Lan et al. [8] discovered that auto-detected bounding boxes often vary from traditional benchmarks in scale (resolution). Accordingly, they proposed a cross-level semantic alignment to address the multi-scale matching problem in person search.

In this study, we designed a framework for practical surveillance scenarios in which the scene images captured different viewpoints and regions, and the pedestrian matching is automatically performed in these images. Pedestrian detection is a necessary step before person matching. The computational efficiency could be improved if the extracted features in the detection step could be further used in the following ReID process. Moreover, the image variances are considered by training the ReID model from the auto-detected bounding boxes, which will increase the model tolerance in the test process. We proposed an integrated deep network consisting of a detection and identification module. Two scene images are input to the detection network. The detection module is based on the Faster R-CNN [35], which can provide a more precise bounding box. The person regions are detected and cropped. Each cropped region is further input to the identification module. In previous studies [13,15,20,40,41], person ReID was cast as a two-class classification problem, and each training pair was given the same or different class label if the two images were from the same person or not. Instead of training the identification module as a two-class classification, we apply a multi-class convolutional neural network (CNN) network to train the identification module, in which each person is considered as a class and an identity (ID) is assigned. The amount of training data for each class is almost the same. The discriminative features are then extracted in the identification module [11]. Finally, the person matching is performed by computing the similarity between the probe image and the gallery images based on the learned distance metric. After sorting the similarities, the top-k results (k is a user-defined value) are shown. Note that the ideas of the proposed system not only add a detection module before identification, but the use of shared features is considered in the system design to improve the computational efficiency. Moreover, in a practical scenario, it would not be feasible to retrain the network when a newcomer’s images are captured. Hence, a flexible system framework was designed by training a multi-class CNN for discriminative feature extraction and learning a distance metric for similarity measurement.

The remainder of this paper is organised as follows: Section 2 reviews the issues of person re-identification; Section 3 presents the proposed system consisting of two modules, person detection and person re-identification, with the details of each module also introduced; Section 4 presents the network parameters and experimental results of the proposed system and discusses the performance with various feature vectors; and finally, Section 5 concludes the paper.

2. Related Work

Person ReID is a difficult problem caused by larger appearance variations that has been gaining a great deal of attention for decades. The mainstream approaches used to solve this problem are either to extract discriminative features or design a distance metric to measure the similarity between images. Feature representation aims to extract robust and discriminative features that are invariant to the appearance variations. Most of the previous studies have focused on hand-crafted features that are designed beforehand by human experts to extract a given set of chosen characteristics. Gray et al. [42] proposed an ensemble of localised features by extracting color and spatial features to address the viewpoint problem. Farenzena et al. [43] extracted three kinds of features—namely the weighted color histogram, maximally stable color regions, and recurrent high-structured patches—to overcome appearance variations. However, it is time-consuming to extract these three types of features [44]. Earlier studies [42,43,45] extracted the color features in the RGB or HSV space, and the performance was limited for lighting or illumination variations. In [44,46,47], the authors applied color names which were intended to relate the numerical colours in the RGB or HSV space with the corresponding semantic color names used in natural language [46] and showed that the feature of color names was more stable for illumination variations. Yang et al. also proposed the salient color names-based color descriptor (SCNCD) [44], and 16 salient colors were applied. Each image was represented as the distribution of salient colors for further similarity measurement. The SCNCD is one representative work among the early methods of extracting color features.

For the similarity measurement, metric learning [12,40,41,48,49] aims to learn a d × d matrix to calculate the Mahalanobis distance between two images, each of which is represented as a d-dimensional vector of hand-crafted features. In [40], Zheng et al. proposed a relative distance comparison and an applied logistic function to minimize the distance between the “same” pairs whilst maximizing the distance between “different” pairs. Weinberger et al. [48] considered the relation of triplets to exploit the local structure of data in the feature space. For each training datum, a local perimeter in the feature space was established by the target neighbors—i.e., the k-nearest neighbors of a datum with the same label—and the impostors are penalised. The impostor is a datum that has smaller distance to the datum than the distance between the datum and its closet target neighbour. To learn the distance metric, the objective function with the form of a mathematical equation was designed to minimize the distance between the target neighbors and the penalisation of the impostors. Davis et al. [41] presented an information–theoretic approach, called ITML, to learn the Mahalanobis distance metric. In contrast to [40,48], in which eigenvalue decomposition or semi-definite programming is applied to obtain the distance matrix, the optimization of ITML is fast and scalable [41]. Considering the growing amount of data, learning a metric on a large dataset raises the problem of providing fully supervised labels for all data points [12]. Hence, in [12], Koestinger et al. proposed the KISS method and provided data labels in the form of equivalence constraints. Inspired by the statistical inference, a simple and effective strategy was introduced to learn a distance metric with a matrix form from the equivalence constraints based on a likelihood-ratio test. The number of parameters in the matrix is large, and principal component analysis (PCA) is first applied to reduce the dimension of the feature vector. Then KISS method is performed to learn the metric in the low-dimensional PCA space [11]. However, PCA is not jointly optimized with the metric learning, and the performance is limited. Hence, in [11], Liao et al. proposed a cross-view quadratic discriminant analysis (XQDA) to jointly learn the low-dimensional space and distance metric.

In the past, most studies proposed for recognition tasks, such as object detection and person ReID, have focused on either the extraction of low and high-level features or the obtaining of a robust classifier. Low-level features are minor details of the image, such as colour, lines, dots, corners, or edges, that can be extracted by a filter (kernel) via the convolution operation SIFT [50] or HOG [51]. High-level features are more abstract and built on low-level features to detect objects and shapes. However, a few works have jointly optimized feature extraction and classification. Deep learning models can simultaneously extract low and high-level features and learn a classifier in a network. In recent years, this has achieved significant success in the computer vision field [16,17,18]. For person ReID, deep models can be roughly categorised into three kinds of approaches: Siamese networks [13,15,20], classification networks [21,22,23], and triplet networks [24,25]. Siamese networks take an image pair as an input and output a similarity score to determine whether or not the two input images depict the same person. In 2014, Yi et al. [15] were the first to jointly learn the color feature, texture feature and metric in a Siamese network. A given image pair was partitioned into three overlapped horizontal parts and put through a Siamese CNN model to measure the cosine distance for each pair of parts. In 2014, Li et al. [13] proposed a filter pairing neural network with six layers to jointly handle misalignment, photometric and geometric transforms, occlusions and background clutter. In 2015, Ahmed et al. [14] proposed a deep network by designing two novel layers: a cross-input neighbourhood difference layer to generate the difference maps by subtracting feature values across two view images, and a patch summary layer to spatially integrate these difference maps. Varior et al. [52] incorporated a long short-term memory model into a Siamese network, which could memorize the spatial information of image parts, and thus these image parts could be processed sequentially to enhance the discriminative capability of features. Classification networks [21,22,23] regard the person ReID as a multi-class recognition task that considers each person as a separate class and applies CNN to extract the discriminative features on large-scale datasets. Xiao et al. [21] designed a pipeline framework to learn deep features with the CNN on multiple domains to improve the performance. The domain-guided dropout algorithm was also proposed to improve the feature learning procedure. Zheng et al. [22] proposed ID-discriminative embedding to fine-tune the pre-trained model from ImageNet to obtain the ReID model. Triplet networks can be considered as an extension version of the Siamese network [24]. Cheng et al. [53] designed a triplet-based Siamese CNN model, which takes three pedestrian images as input and uses the triplet loss function to train the network. The proposed multi-channel CNN model can jointly learn both the global full-body and local body-parts features for input images. The extracted features were concatenated into a global representation in a fully-connected layer. The authors in [25,54] also utilized the triplet loss function for network optimization. In 2018, Wang et al. [55,56] proposed a point-to-set network (P2SNet) to jointly learn the feature representations and a point-to-set distance metric in a unified manner by utilizing the triplet loss for network training.

Although the CNN model can achieve significant improvement regarding the ReID problem, the parameters of the CNN models are complex compared to the number of training samples. An over-fitting problem might also happen, which refers to a model that is too closely fit to the training data and leads to the poor generalization of test data. Data augmentation and regularization methods that generate pseudo samples to increase the amount of training data and enrich the diversity of the training data were proposed to reduce the risk of over-fitting [23,26,30,31]. Niall et al. [30] introduced data augmentation by changing the background to generate samples. Zheng et al. [23] adopted a deep convolutional generative adversarial network (DCGAN) [31] for sample generation and assigned a uniform label distribution to these unlabelled images to regularize the network. In [49], Zhong et al. proposed a camera-style adaptation method via CycleGAN to learn the camera-aware image styles for each pair of cameras, and then new training images could be generated from the original dataset.

Meanwhile, in practice, the precision of the person detection results is a key factor for person ReID because an imperfect detection bounding box results in a misalignment. Using local features could result in fewer impacts than global features [54]. In the past, some attention selection techniques, such as patch matching [57,58] and saliency weighting [59,60], have been proposed to overcome the misalignment. Although dividing the global image into regions could cope with the misalignment, the improvement of using the fixed-body part division is limited. Deep learning methods [27,28,29] have recently been proposed to handle the matching misalignment. The common strategy is to incorporate a regional attention selection sub-network into a deep ReID model. For example, instead of using rigid parts, Li et al. [27] adopted spatial transformer networks with a given pre-defined spatial constraint to localize deformable pedestrian parts. A unified multi-class classification network was then designed to extract discriminative features from full body and body parts for person ReID. Inspired by attention models, Zhao et al. [29] designed an end-to-end part-aligning CNN network without labelling information of the human body parts to jointly locate the discriminative regions and feature representation. Su et al. [28] proposed a pose-driven deep network. A separately trained pose detection model was then integrated into a part-based ReID model. Moreover, Wei et al. [60] utilized Deepercut to detect three coarse body regions through a four-stream CNN model and learn a global-local-alignment descriptor. Instead of using hard attention models, the soft attention model was more suitable for human-part representation. Hence, Li et al. [61] formulated a joint learning scheme to model both hard and soft attention in a single ReID deep network.

3. Overview of the Deep Integrated Networks for Person Search

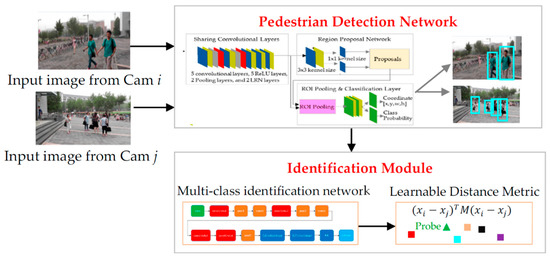

Figure 1 shows an overview of the proposed deep networks by integrating person detection and identification (IPnetwork) for person search. The IPnetwork was composed of two modules: one is the detection network, and the other one is the identification module. Two images captured by non-overlapped cameras were input to the detection network, which was based on the Faster R-CNN network [35]. The regions of a person were then detected and cropped. Each cropped region was further input to the identification module, which consists of a convolutional neural network (CNN) to extract the discriminative features. Note that, rather than casting person ReID as a two-class classification problem [13,15,20], the identification module was trained as the multi-class classification in which each person was given one ID, and the convolution layers aimed to capture discriminative features. Then, the similarity of each pair of feature vectors was calculated by XQDA [11]. In the test process, the matching results were obtained by sorting the similarities between the probe person image and gallery images in descending order, and the top-k results are shown. Note that the k value is user-defined, and if k = 1, only one gallery image with the highest similarity is shown. The detection network, which is composed of sharing convolutional layers, region proposal network (RPN) [35] and region of interest (ROI) pooling and classification, is introduced in Section 3.1. The identification module—composed of a multi-class CNN network—and the metric learning for the similarity measurement are introduced in Section 3.2 and Section 3.3, respectively.

Figure 1.

Overview of the proposed deep integrated person detection and identification system (IPnetwork).

3.1. Pedestrian Detection Network

The first module aims to perform the pedestrian detection. Several objection detection algorithms based on deep learning networks have been proposed in the recent years. These algorithms include Fast R-CNN [62], Faster R-CNN [35], SSD [36], You Only Look Once (YOLO) [63] and Mobile Net [64], which can be roughly categorised into classification-based [35,62] and regression-based methods [36,63,64]. Note that the classification-based methods apply strategies to search the candidates (i.e., proposals) in which the object might appear. Classification is then performed on these candidates for further refinement. Meanwhile, regression-based methods discard the process of searching candidates and directly obtain the object locations. The regression-based methods are generally faster than those based on classification, but the classification-based methods provide more precise detection results (i.e., most parts of objects are enclosed within a compact bounding box) [35]. Considering that the ultimate ambition is pedestrian identification, a precise detection result is practically given a higher priority. Thus, the first module was based on the Faster R-CNN [35], which can provide relatively fast detection results among the classification-based methods.

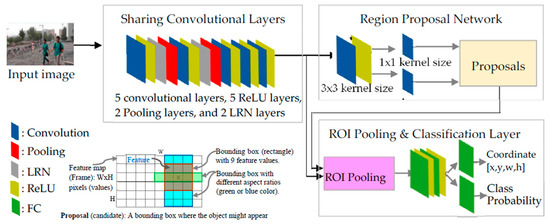

For the Faster R-CNN network configuration [35], the first module was composed of three parts: sharing convolutional layers, RPN was used to predict the proposals (i.e., candidate locations, where the pedestrians might appear in the image), and ROI pooling and classification layers were used to classify where a pedestrian exists in those proposals. Figure 2 shows the network configuration of the first module in detail. Four steps were applied to obtain the final detection result when one image was input to the first module. Firstly, the low-level features of the image were extracted by the sharing convolutional layers. The feature map of the final convolutional layer was then input to the following parts of the networks. Secondly, the RPN was used to generate proposals by performing a sliding window on the feature map. Thirdly, the feature map from the sharing convolutional layer and the generated proposals were input to the ROI pooling layer; hence, the corresponding features for each proposal could be extracted. The final classification layer output the classification result, and bounding box regression was applied to obtain a more precise object location. The network configuration and operations performed in each step are introduced in the subsections that follow.

Figure 2.

Configuration of the pedestrian detection network composed of three parts: sharing convolutional layers, region proposal network and region of interest (ROI) pooling and classification layers. LRN: local response normalization; ReLU: rectified linear unit; FC: fully-connected layer.

3.1.1. Sharing Convolutional Layers

The Zeiler and Fergus model [65] is a CNN which comprises five sharing convolutional layers with the corresponding rectified linear unit (ReLU) layer, two pooling layers and two local response normalizations (LRN) [16] which was applied in the proposed configuration. In the convolutional layers, the convolution operations are performed on the input with multiple kernels, each of which is also called a filter and refers to a rectangular array. Assuming the input size to the l-th layer is and the size of the d-th kernel is , the convolution results, which are called feature maps, have the size of and D is the number of kernels. In mathematics, the convolution result y at the spatial location in the d-th feature map can be represented as

where is the input to the l-th layer, is the element of at the location ,, , and . Note that the stride—the number of pixels a convolutional kernel moves across an image space—is 1 and no zero padding is used to pad the input with zeros around the border. The ReLU layer does not change the size of the input. In other words, the size of xl and y is the same. ReLU is an active function which is performed individually for every element in the input xl and it is formulated as [66]

where , , and .

Two types of pooling operators are widely used: max pooling and average pooling [66]. The max pooling operation is performed on each subregion of 3 × 3 or 5 × 5 pixels and the maximum value within a subregion is preserved, while the average pooling operation is used to preserve the averaging values within a subregion. Hence, the pooling operation requires no parameter. Assume the stride in the vertical and horizontal direction are P and Q, respectively; the output size of the pooling layer will be , where , and it can be formulated as

where , , and .

The network configuration is shown in Table 1. When inputting an image frame with an arbitrary size, this would be resized to 563 × 1000 pixels. The size of the feature maps output by the fifth convolution layer was 36 × 64 × 256 pixels. More details of the network parameters are presented in Section 4.

Table 1.

Network configuration for the Zeiler and Fergus network [65].

3.1.2. Region Proposal Network

One important step for object detection algorithms is to predict where the object appears. Not only the location but also the object scale is diverse, and a pyramid was used to detect objects with various sizes by repeatedly smoothing and subsampling the original image. In [67], a sliding window was applied to classify whether or not an object exists. However, if the following classification algorithm is complex, processing and classifying each sliding window will be time-consuming. Hence, in [68], a selective search [69,70] was used to predict the object location; however, the improvement was limited. In [35], a network called RPN (Figure 2) was proposed. The RPN can predict the object coordinate. It consists of one 3 × 3 convolution layer in the front of the network and receives the feature map from the output of the fifth sharing convolutional layer. The feature maps with the size of W × H pixels were assumed after the input was processed by the 3 × 3 convolution layer. The k multiple rectangles (k = 9 in the experiments) with aspect ratios of 0.5, 1 and 2 are sliding for each pixel in the feature map, meaning that objects with different sizes may be detected. Two branches of the RPN were designed: the network branch, which classifies whether the rectangle contains the object, and the regression branch, which estimates the transformation parameters for each rectangle, respectively. Figure 2 illustrates an example of a feature map with a size of W × H pixels, a bounding box (rectangle), and a bounding box with different aspect ratios.

The network branch consisted of one 1 × 1 convolutional layer and one softmax layer to estimate the foreground (object) or background probability of rectangles. The softmax layer consists of a function that takes real numbers as an input and normalizes each number into a probability proportional to the exponentials of the input numbers. Note that the number of 1 × 1 kernels was 2k (18 in the experiment), which corresponded to the probability of the object or background for each rectangle. The object candidates (i.e., proposals) can be obtained in the following softmax layer. In contrast, the regression branch consisted of one 1 × 1 convolutional layer, and regression was applied to refine the coordinate of the rectangle. Note that the number of 1 × 1 kernels was 4k (36 in the experiment), which corresponded to the coordinate for each rectangle (i.e., the x- and y-coordinate of the centre of the rectangle) and the rectangle’s width and height. Linear regression for the bounding box [35] aims to minimize the error between the coordinates of a rectangle , and the corresponding ground truth, , which refers to the correct answer for each training sample provided by ourselves. The shift relation between A and G can be represented as follows [35]:

where and are the shift parameters in x- and y-coordinates. The scale difference can be represented as follows:

where and are the scale parameters. The linear transformation could be assumed, and Equations (4) and (5) can be modified as follows when the difference between A and G is small [35]:

The shift and scale parameters can be learned as follows via linear regression:

where L denotes the parameters of the linear regression model, is a tensor with a size of W × H × 36, and each element of the tensor corresponds to four parameters of the k rectangles. The model parameters can be obtained by minimizing the loss function to mimic the regression error between the estimated results and the ground truth [35]:

where λ is a trade-off between the regression error and the regularization term that gives a constraint for the elements of L to avoid overfitting.

After obtaining the probabilities and refined coordinates for each rectangle via two branches [49], the first 6000 rectangles were selected according to the sorted softmax score. Also, each rectangle’s coordinates in the original input image are obtained by inversely mapping according to the refined coordinate . Rectangle i is discarded if coordinates are out of the image bounds. Non-maximum suppression [16] was then applied to reduce the number of rectangles. The first 300 rectangles from the remaining rectangles based on the softmax scores were output as proposals. In short, the rectangles with unreasonable size, a low probability of an object, or which were out of image bounds were discarded, and only 300 proposals were further processed in the following layers of the pedestrian detection network.

3.1.3. ROI Pooling and Classification Layer

After the proposals were predicted, their corresponding features were extracted for further classification to obtain the final detection result. The size of the input for the classification network [16,71] is generally pre-set and fixed, which limits the aspect ratio and the scale of the input [72]. However, the scales—i.e., the width and height—of proposals varied. Fitting the proposal’s scale to the fixed size for the classification network by either cropping [16,65] or warping [68] may result in a region drop or geometric distortion [71]. Hence, inspired by Spatial Pyramid Pooling [71], one ROI pooling layer was proposed in [35], which received two kinds of information: the coordinates of the proposals and the feature map from the sharing convolution layer. The ROI pooling layer would extract the features for each proposal before classification. Three parameters—namely pool_w, pool_h and spatial_scale—were set to correspond to the output size of the ROI pooling layer in terms of the width, height and scale mapped between the proposal and feature maps to obtain a fixed-length representation. Max pooling was applied for each pooled region after mapping.

Two fully-connected (FC) layers and one softmax layer were set in the end of the pedestrian detection network. The softmax layer output the probability belonging to the pedestrian class. A proposal with a probability larger than 0.9 was kept, and linear regression for the bounding box as shown in Equations (7) and (8) was applied to obtain the refinement coordinate.

3.2. Discriminative Feature Extraction via the Multi-Class Identification Network

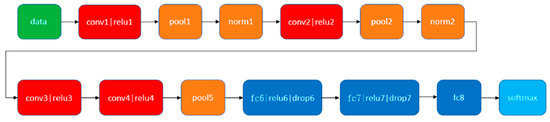

Figure 3 shows details of the identification network consisting of four convolutional layers with the ReLU function, three fully-connected (FC) layers, and one softmax layer. Based on the order in the recognition network, the convolution layers and FC layers were assigned a cardinal number. In contrast to the previous studies [13,15,20], person ReID was casted as a two-class classification and the model was trained to classify the input pair as the “same” or “different” class. However, the combination amounts of the different class are much larger than for the same class. For example, there are n distinct persons (subjects) in the training dataset, and the number of pairs for the same class is n, while there are pairs for the different class. The amount of data for the classes is unbalanced. Hence, rather than learning the features of the same or different class, in the proposed system, person ReID is viewed as a multi-class classification, and the discriminative features of different subjects were therefore learned by the network. If the network extracts two images with similar characteristics, they are in the same class with a high probability. Thus, the number of subjects in the training data set (i.e., n = 306, in our case) was the size of the softmax layer in the multi-class identification network.

Figure 3.

Identification network configuration [21].

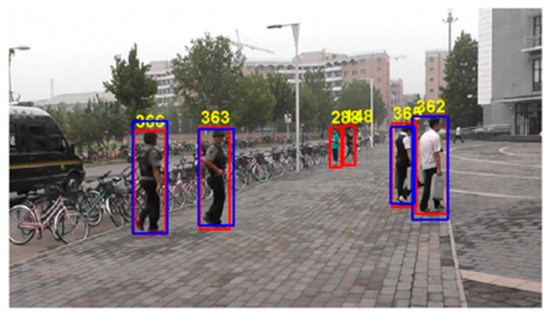

Most of the previous studies focused on either person detection or ReID and viewed them as separate applications [9]. For ReID, the input pair of pedestrian images in the training or test process was human-cropped and labeled before being input to the identification module. However, for practical applications, the precision of the detection result (e.g., the size of the bounding box) would affect the ReID performance. Hence, in our work, the training data for the identification network were obtained from the detection network. If the intersection of overlap (IOU) between the detected bounding box and the ground truth is larger than the threshold (i.e., 0.5, in our case), confidence is assumed to give the detected bounding box the same class label (ID) with the ground truth automatically. This is done without a manual check process. Those labelled bounding boxes are used in the identification module training process, and in the following training process, the remaining unlabelled boxes are omitted. Figure 4 shows an example of the detection result (blue color) and the ground truth (red color). Note that the output of the FC6 layer was extracted as a feature vector for the input bounding box, and the similarity between the two feature vectors was measured via the learnable distance metric.

Figure 4.

Example of the detected bounding box (blue color) and the ground truth (red color). The class label (ID) is annotated above the ground truth. The bounding box with the corresponding ID is used in the training process of the identification module if the intersection of overlap (IOU) is larger than 0.5.

3.3. Similarity Measure with a Learnable Distance Metric

The similarity between the vectors is measured and the results are sorted after extracting the feature vector for each bounding box. Studies have showed that the Mahalanobis distance can obtain better results than the Euclidean distance, and many learnable metrics have been proposed [12,40,41,48,49]. Among them, KISSME [12] can easily obtain the metric based on the statistic models and . The log likelihood ratio is given as follows:

where is the pairwise difference. Thus, a higher value of means that the probability of pair being negative is larger. Furthermore, statistic models and can be modelled as a multi-dimensional Gaussian model, and the mean is a zero vector (i.e., and ). Therefore, Equation (10) can be rewritten as follows [12]:

After the log function, the log likelihood can be represented as follows [12]:

The and terms are constant; hence, Equation (12) can be simplified and represented as follows:

where is the Mahalanobis distance between two points and xj. Since the distance cannot be negative, the matrix M must satisfy the positive semidefinite constraint [43]; in other words, all the eigenvalues of M are non-negative. However, in Equation (13), is a symmetric matrix but would semidefinitely not be positive. Hence, in order to enforce the constraint to the matrix M, one method is to resort to the eigenvalues of M and construct matrix using those vectors with a positive eigenvalue [48]. The dimension reduction was first applied for using the PCA to ensure that inverse matrices and exist [12]. However, the discriminate features would be discarded via dimensional reduction. In [11], the authors were inspired by the linear discriminant analysis (LDA) and proposed a transformation w to enlarge the distance between dissimilar pairs while shortening the distance between the same pairs, as follows:

where w is a projected matrix that can be resolved by the eigenvalue decomposition that can factorize a matrix into a form of eigenvalues and eigenvectors. Thus, Equation (14) can be reformulated as follows to maximise [11]:

4. Experimental Results

We evaluated the performance of the proposed identification system with different feature combinations. The network parameters and experimental setup are first introduced, including the dataset and the computing environment. The feature combinations and experiments are then introduced. Finally, the performance measurement and quantitative results are shown.

4.1. Experimental Setup and Dataset

In the pedestrian detection network, when one image frame with an arbitrary size is input, it would be resized to 563 × 1000 pixels. The detailed parameters of sharing convolutional layers were set as follows: 96 kernels with a kernel size of 7 × 7 pixels, two pixels of the stride size, and three pixels of padding were used in the first convolutional layer. Hence, feature maps with a size of 282 × 500 × 96 could be obtained. The feature map size was unchanged after the LRN layer and downsampled to 142 × 251 × 96 after max pooling layer with a kernel size of 3 × 3 pixels, two pixels of the stride size and one pixel of padding. The size of the feature maps output by the fifth convolutional layer was 36 × 64 × 256 pixels. In the ROI pooling layer, the parameters of pool_w and pool_h were set to 6, and spatial_scale was 6 × 6 for all the proposals. Besides this, in the identification network, the input size was 227 × 227 × 3. The output sizes of FC6, FC7 and FC8 were 4096, 4096 and 2048, respectively.

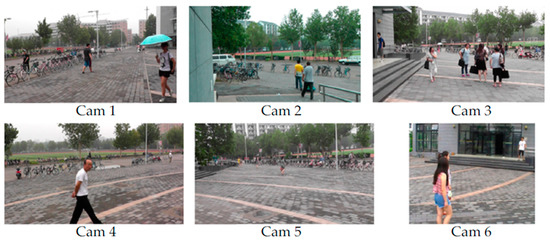

In order to evaluate the system performance, several benchmarks have been used for person re-identification. Among them, the dataset PRW [70] is a challenging dataset that includes images captured by the six cameras with different scene views (Figure 5); hence, the poses of the pedestrian images varied. The image resolution captured by the sixth camera was 720 × 576 pixels and 1920 × 1080 pixels for the other five cameras. The PRW comprised 11,816 RGB images, and 43,110 bounding boxes were manually labelled. Among them, 34,304 bounding boxes were assigned with 932 person IDs, and the remaining boxes for which the models were unsure about a person’s ID were assigned an ID of −2. Each bounding box contained five pieces of information [i.e., x, y, w, h and s], where (x, y) is the left-corner coordinate of the bounding box, (w, h) denotes the width and height of the bounding box, and s is the person ID.

Figure 5.

Example images captured by six cameras in the PRW dataset [70].

4.2. Experiments with Various Features

All the pedestrian images in the PRW dataset are automatically cropped by the detection module. Three kinds of experiments were applied to investigate the identification module configuration. Table 2 lists the experimental settings in detail. Note that the training images in all the experiments were obtained from cameras 1 to 6, the probe images in the test process were from camera 2, and the gallery images were from camera 3. We divided the dataset into the training and test sets with different person IDs. Note that to simulate the real scenario, in which several images are often captured by cameras, and to understand how the probe and gallery size would affect the ReID performance, the scene images captured by cameras 2 and 3 were used for the test set because, in the PRW dataset, the numbers of matching subjects in the combination of cameras 2 and 3 were more than in other camera combinations.

Table 2.

List of experimental settings for the identification module evaluation. CNN: convolutional neural network.

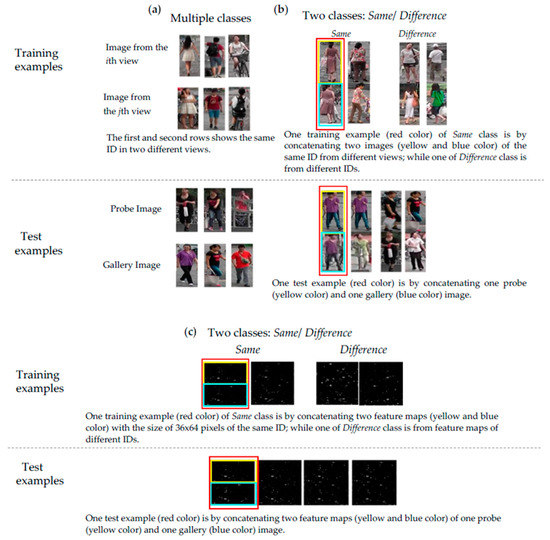

As stated in Section 3, the identification configuration was implemented in Experiment 1, and the network was trained in 306 pedestrian IDs with 7508 RGB images. Figure 6a shows the example images. The network configuration of two-class CNN in Experiment 2 was evaluated. The network was trained with only two classes: same and different. Hence, the training images used in Experiment 1 were sampled and vertically concatenated to form the training data pairs. The pair numbers of the different class (different IDs) were 87,363 and 29,226 for the same class. (same ID). The test images were concatenated to form the test set with 28,224 pairs. Figure 6b shows the example images used in Experiment 2. As in Experiment 2, Experiment 3 was also designed to evaluate the network configuration of two-class CNN; the only difference was that, rather than using RGB images, the feature maps for each image output from the fifth sharing convolutional layer are vertically concatenated in Experiment 3. Hence, the numbers of training and test pairs were the same as Experiment 2. Figure 6c illustrates the example images used in Experiment 3.

Figure 6.

Training and test examples in (a) Experiment 1, (b) Experiment 2 and (c) Experiment 3.

4.3. Performance Metrics and Experimental Results

The pedestrian detection performance was measured by the detection rate and false alarm rates. For the detection rate, the bounding box was correctly detected if the overlapped area between the bounding box and the ground truth was larger than the pre-set threshold :

where I [] is an indicator function; N is the test image number; is the number of ground truth boxes in the tth image; and are the kth ground truth and the detected box in the tth image, respectively; and is the IOU. If the IOU is smaller than , the bounding box is incorrect, and will be shown as a false alarm. The higher the detection rate and the lower the false alarm rate, the better the detection performance. Table 3 shows the detection results using the images captured by cameras 2 and 3. The threshold was set to = 0.5 and 0.7. The detection performance was better when was set to 0.5.

Table 3.

Detection results with different IOU thresholds.

The performance evaluation metrics of ReID are the cumulative matching characteristic (CMC, top-K), in which a correct matching is counted if there is at least one of the top-k gallery images with the same identity as the probe image. In Experiment 1, three test sets (i.e., TSet1, TSet 2 and TSet 3) containing different numbers of images for each test subject were used. In TSet 1, for each subject (168 subjects are in Experiment 1, as shown in Table 2), one image is randomly selected from the scene images captured by camera 3 to form the gallery set, while in TSet 2, two images are randomly selected. In TSet 3, all images for each of the 168 subjects captured by camera 3 are used. Hence, it is expected that each test identifies more images in the gallery and can achieve a higher identification rate. Note that, in our work, the pedestrian images in the probe and gallery sets are detected and cropped automatically in the detection module. Table 4 lists the top, top-5, top-10 and top-20 identification rates with different feature vectors and distance metric. As shown, TSet 3 was better compared to TSet 1 and TSet 2, and for each subject, more images in the gallery set improved performance. To investigate the detection effects in a real-world application, instead of using the detected bounding box, a multi-class CNN was trained by the manual-labelled ground-truth (GT) bounding box. In the test process, all the probe and gallery pedestrian images used the ground-truth bounding box and input this to the newly trained multi-class CNN to extract the feature vectors from the FC6 layer. For TSet 3, the identification rate using the GT bounding box is presented in the last two rows of Table 4. Approximately an identification rate difference of 11.1% in the top set between the auto-detected results and manual labelling was observed. Hence, in practical applications, the results of the pedestrian detection indeed influence the identification results, and closing this gap is an important issue.

Table 4.

Identification rate with different feature vectors and distance metric.

Experiment 2 and Experiment 3 are used to investigate the network configuration. The input to the network in Experiment 2 and Experiment 3 was the concatenated RGB image or feature map, respectively. The softmax layer output the probability of the image being the same class. The higher the output value, the higher the probability that the input will be formed by the same identity datum. In addition, for Experiment 2, and Experiment 3, a two-class CNN was trained individually to determine whether the input belonged to the same or different class. The hyperparameter, specifying the network configuration such as the layer number, kernel size and kernel number, was the same as used for Experiment 1, except for the number of output nodes in the softmax layer. In the test process, 168 gallery images were concatenated with the probe image for each probe image. The resulting 168 probability values were sorted. The probe image was correctly verified if the concatenation of the probe and gallery images with the same ID was retrieved in the top-k results. Table 5 lists the identification rate with the top value in Experiment 2 and Experiment 3. Note that the results of the best performance in Experiment 1 were listed to compare the feature extraction performances. The results show that the performance of Experiment 3 was the worst. The top identification rate was very low (i.e., only 4.76%). We believe this is because the input in Experiment 3 was the concatenated feature maps from the fifth sharing convolutional layer in the detection network, and hence the feature maps contained little and insufficient subject information for identification, as shown in Figure 6c. For Experiment 2 and Experiment 3, the amount of data from combining different images from either the same or different class is large, and the contents of combination are diverse, which resulted in learning difficulties for the two-class CNN models. The performance of the multi-class identification network (Experiment 1) was significantly higher than the two-class CNN network (Experiment 2) in analysing the network configuration for the identification module. The experimental results with different training/test settings from other studies [16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66] are listed below Table 5.

Table 5.

List of the identification rate in Experiment 1, Experiment 2 and Experiment 3 for the PRW dataset.

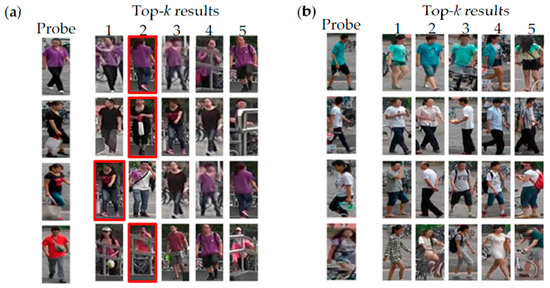

Figure 7 and Figure 8 show the successful and failure cases in Experiment 1 and Experiment 2, respectively. In the failure case in Figure 7, no instance of the same identity is retrieved in the top-k results, while in Figure 8, the same pair is not retrieved in the top-k results.

Figure 7.

Examples of the identification results in Experiment 1 (identification network): (a) successful and (b) failure cases.

Figure 8.

Examples of the identification results in Experiment 2 (identification network): (a) successful and (b) failure cases.

5. Conclusions

Person search is a practical application which includes two kernel parts, person detection and re-identification, and it is more challenging than person ReID because most existing ReID studies have only processed and classified input pedestrian images enclosed within a bounding box, but have ignored the fact that an imperfect bounding box or background clutter is inevitable. For practical surveillance scenarios, where scene images are captured by two or multiple cameras, this study proposed an integrated network consisting of a detection and identification module to implicitly consider the effect of the detection results. Two images captured by non-overlapped cameras were input to the Faster R-CNN detection network. A multi-class CNN network was trained with the auto-detected bounding boxes from the detection module instead of manually cropped data to extract discriminative features. Hence, the FC layers of the multi-class CNN can be utilized as the discriminative features, and the similarity of the two feature vectors are calculated via a learnable distance metric. In addition, the proposed framework is more flexible; when one new person is detected, the feature vector is then extracted by the multi-class CNN and compared with other images in the dataset without retraining the network. The experimental result show that the multi-class CNN network for the identification module can provide a 62.7% accuracy, which is significantly higher than that in the two-class CNN network. Moreover, more experiments have been designed to apply sharing features to improve the computational efficiency. However, the results of the identification are not satisfactory because the feature maps of the detection network contained less and unclear information about subjects. In the future, we would like to design a search strategy for real-world applications and re-design the network configuration such that the detection and identification module can utilize shared convolution feature maps for computational efficiency.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.-F.W., J.-C.C. and C.-H.C.; Methodology, C.-F.W. and J.-C.C.; Software, C.-H.C. and C.-R.L.; Writing—original draft, C.-F.W.; Writing—review & editing, J.-C.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology of Taiwan, R.O.C., under grant No. 108-2221-E-992-032-.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Gan, W.; Lin, J.C.W.; Fournier-Viger, P.; Chao, H.C.; Yu, P.S. HUOPM: High-utility occupancy pattern mining. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2019, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.C.W.; Yang, L.; Fournier-Viger, P.; Hong, T.P. Mining of skyline patterns by considering both frequent and utility constraints. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2019, 77, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, W.; Lin, J.C.W.; Fournier-Viger, P.; Chao, H.C.; Yu, P.S. A survey of parallel sequential pattern mining. ACM Trans. Knowl. Discov. Data (TKDD) 2019, 13, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Z.; Shi, Z.; Guo, Y.; Ye, J. Object detection in 20 years: A survey. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1905.05055. [Google Scholar]

- Bouindour, S.; Snoussi, H.; Hittawe, M.M.; Tazi, N.; Wang, T. An on-line and adaptive method for detection abnormal events in videos using spatio-temporal convent. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Deng, W. Deep face recognition: A survey. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1804.06655. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Ma, B.; Huang, R.; Lin, L. Person search in a scene by jointly modeling people commonness and person uniqueness. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Orlando, FL, USA, 3–7 November 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lan, X.; Zhu, X.; Gong, S. Person search by multi-scale matching. In European Conference on Computer Vision; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 536–552. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, T.; Li, S.; Wang, B.; Lin, L.; Wang, X. Joint detection and identification feature learning for person search. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 3415–3424. [Google Scholar]

- Buda, M.; Maki, A.; Mazurowski, M.A. A systematic study of the class imbalance problem in convolutional neural networks. Neural Netw. 2018, 106, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, S.; Hu, Y.; Zhu, X.; Li, S.Z. Person re-identification by local maximal occurrence representation and metric learning. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015; pp. 2197–2206. [Google Scholar]

- Koestinger, M.; Hirzer, M.; Wohlhart, P.; Roth, P.M.; Bischof, H. Large scale metric learning from equivalence constraints. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Providence, RI, USA, 16–21 June 2012; pp. 2288–2295. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Zhao, R.; Xiao, T.; Wang, X. Deepreid: Deep filter pairing neural network for person re-identification. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Columbus, OH, USA, 23–28 June 2014; pp. 152–159. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, E.; Jones, M.; Marks, T.K. An improved deep learning architecture for person re-identificatio. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015; pp. 3908–3916. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, D.; Lei, Z.; Liao, S.; Li, S.Z. Deep metric learning for person re-identification. In Proceedings of the 2014 22nd International Conference on Pattern Recognition, Stockholm, Sweden, 24–28 August 2014; pp. 34–39. [Google Scholar]

- Krizhevsky, I.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. Imagenet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, T.; Do, T.; Tan, D.; Cheung, N. Selective deep convolutional features for image retrieval. In Proceedings of the 25th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Mountain View, CA, USA, 23–27 October 2017. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Glasmachers, T. Limits of end-to-end learning. Mach. Learn. Res. 2017, 77, 17–32. [Google Scholar]

- Varior, R.R.; Haloi, M.; Wang, G. Gated Siamese convolutional neural network architecture for human reidentification. In European Conference on Computer Vision; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, T.; Li, H.; Ouyang, W.; Wang, X. Learning deep feature representations with domain guided dropout for person re-identification. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, L.; Yang, Y.; Hauptmann, A.G. Person reidentification: Past, present and future. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1610.02984. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Z.; Zheng, L.; Yang, Y. Unlabeled samples generated by gan improve the person re-identification baseline in vitro. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuo, J.; Chen, Z.; Lai, J.; Wang, G. Occluded person reidentification. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.02792. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; You, Y.; Zou, X.; Chen, V.; Li, S.; Huang, G.; Hariharan, B.; Weinberger, K.Q. Resource aware person re-identification across multiple resolutions. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 8042–8051. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, Z.; Zheng, L.; Kang, G.; Li, S.; Yang, Y. Random erasing data augmentation. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1708.04896. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, K. Learning deep context-aware features over body and latent parts for person re-identification. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Su, C.; Li, J.; Zhang, S.; Xing, J.; Gao, W.; Tian, Q. Pose-driven deep convolutional model for person re-identification. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, L.; Li, X.; Wang, J.; Zhuang, Y. Deeply-learned part-aligned representations for person re-identification. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017. [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin, N.; del Rincon, J.M.; Miller, P. Data augmentation for reducing dataset bias in person reidentification. In Proceedings of the 2015 12th IEEE International Conference on Advanced Video and Signal Based Surveillance (AVSS), Karlsruhe, Germany, 25–28 August 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Radford, A.; Metz, L.; Chintala, S. Unsupervised representation learning with deep convolutional generative adversarial networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, San Juan, Puerto Rico, 2–4 May 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, D.; Brennan, S.; Tao, H. Evaluating appearance models for recognition, reacquisition, and tracking. Int. Workshop Perform. Eval. Track. Surveill. 2007, 3, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Hirzer, M.; Beleznai, C.; Roth, P.M.; Bischof, H. Person re-identification by descriptive and discriminative classification. In Image Analysis; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Wang, X. Locally aligned feature transforms across views. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Portland, OR, USA, 23–28 June 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2017, 39, 1137–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Szegedy, C.; Reed, S.; Fu, C.Y.; Berg, A.C. SSD: Single shot multibox detector. In European Conference on Computer Vision; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 21–37. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, F.; Li, W.; Li, Q.; Liu, Y.; Shi, X.; Yan, J. Poi: Multiple object tracking with high performance detection and appearance feature. In European Conference on Computer Vision; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 36–42. [Google Scholar]

- Felzenszwalb, P.F.; Girshick, R.B.; McAllester, D.; Ramanan, D. Object detection with discriminatively trained part-based models. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2010, 32, 1627–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Feng, J.; Jie, Z.; Jayashree, K.; Zhao, B.; Qi, M.; Jiang, J.; Yan, S. Neural person search machines. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, W.S.; Gong, S.; Xiang, T. Re-identification by relative distance comparison. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2013, 35, 653–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, J.V.; Kulis, B.; Jain, P.; Sra, S.; Dhillon, I.S. Information-theoretic metric learning. In Proceedings of the 24th International Conference on Machine Learning, Corvalis, OR, USA; 2007; pp. 209–216. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, D.; Tao, H. Viewpoint invariant pedestrian recognition with an ensemble of localized features. In European Conference on Computer Vision; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; Volume 5302, pp. 262–275. [Google Scholar]

- Farenzena, M.; Bazzani, L.; Perina, A.; Murino, V.; Cristani, M. Person re-identification by symmetry-driven accumulation of local features. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–18 June 2010; pp. 2360–2367. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Yang, J.; Yan, J.; Liao, S.; Yi, D.; Li, S.Z. Salient color names for person re-identification. Eur. Conf. Comput. Vis. 2014, 8689, 536–551. [Google Scholar]

- Kviatkovsky, I.; Adam, A.; Rivlin, E. Color invariants for person reidentification. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2013, 35, 1622–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, D.; Lu, G.; Ma, W.Y. Region-based image retrieval with high-level semantic color names. In Proceedings of the 11th International Multimedia Modelling Conference, Melbourne, Australia, 12–14 January 2005; pp. 180–187. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo, C.H.; Khamis, S.; Shet, V. Person re-identification using semantic color names and rankboost. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE Workshop on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Tampa, FL, USA, 15–17 January 2013; pp. 281–287. [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger, K.Q.; Saul, L.K. Fast solvers and efficient implementations for distance metric learning. In Proceedings of the 25th International Conference on Machine Learning, Helsinki, Finland, 5–9 July 2008; pp. 1160–1167. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, Z.; Zheng, L.; Zheng, Z.; Li, S.; Yang, Y. Camera style adaptation for person re-identification. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1711.10295. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe, D.G. Distinctive image features from scale-invariant keypoints. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2004, 60, 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalal, N.; Triggs, B. Histograms of oriented gradients for human detection. In Proceedings of the 2005 IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR’05), San Diego, CA, USA, 20–25 June 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Varior, R.R.; Shuai, B.; Lu, J.; Xu, D.; Wang, G. A siamese long short-term memory architecture for human reidentification. In European Conference on Computer Vision; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, D.; Gong, Y.; Zhou, S.; Wang, I.; Zheng, N. Person re-identification by multi-channel parts-based cnn with improved triplet loss function. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 1335–1344. [Google Scholar]

- Hermans, L.B.; Leibe, B. In defense of the triplet loss for person re-identification. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1703.07737. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.C.; Lai, J.H.; Xie, X.H. P2snet: Can an image match a video for person re-identification in an end-to-end way? IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2017, 28, 2777–2787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Chen, Y.-C.; Li, X.; Wu, A.C.; You, J.J.; Zheng, W.S. An enhanced deep feature representation for person re-identification. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Lake Placid, NY, USA, 7–10 March 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Y.; Lin, W.; Yan, J.; Xu, M.; Wu, J.; Wang, J. Person re-identification with correspondence structure learning. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Santiago, Chile, 7–13 December 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, W.S.; Li, X.; Xiang, T.; Liao, S.; Lai, J.; Gong, S. Partial person re-identification. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Santiago, Chile, 7–13 December 2015; pp. 4678–4686. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, R.; Ouyang, W.; Wang, X. Unsupervised salience learning for person re-identification. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Portland, OR, USA, 23–28 June 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, L.; Zhang, S.; Yao, H.; Gao, W.; Tian, Q. Glad: Global-local-alignment descriptor for pedestrian retrieval. In Proceedings of the 25th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Mountain View, CA, USA, 23–27 October 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Zhu, X.; Gong, S. Harmonious attention network for person re-identification. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; p. 2285. [Google Scholar]

- Girshick, R. Fast R-CNN. In International Conference on Computer Vision; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 779–788. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, A.G.; Zhu, M.; Chen, B.; Kalenichenko, D.; Wang, W.; Weyand, T.; Andreetto, M.; Adam, H. MobileNets: Efficient convolutional neural networks for mobile vision applications. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1704.04861. [Google Scholar]

- Zeiler, M.D.; Fergus, R. Visualizing and understanding convolutional neural networks. In European Conference on Computer Vision; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 818–833. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J. Introduction to Convolutional Neural Networks; National Key Lab for Novel Software Technology: Nanjing, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, B. Generic Object Detection Using Adaboost; Department of Computer Science University of California: Santa Cruz, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Girshick, R.; Donahue, J.; Darrell, T.; Malik, J. Rich feature hierarchies for accurate object detection and semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Columbus, OH, USA, 23–28 June 2014; pp. 580–587. [Google Scholar]

- Uijlings, J.R.; van de Sande, K.E.; Gevers, T.; Smeulders, A.W. Selective search for object recognition. Int. Conf. Comput. Vis. 2013, 104, 154–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Zhang, H.; Sun, S.; Chandraker, M.; Yang, Y.; Tian, Q. Person re-identification in the wild. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Spatial pyramid pooling in deep convolutional networks for visual recognition. ECCV 2015, 37, 1904–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1409.1556. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).