Abstract

This paper presents the results of the content analysis of 139 Web of Science papers focused on collaborative innovation with external stakeholders of public administration, specifically on co-production and co-creation. The analysis included papers published between 2009 and 2018 and was based on a coding scheme consisting of 12 parameters grouped into four groups: paper descriptors, financial support of the research, methodological framework, and co-creation characteristics. The results reveal a considerable increase in researchers’ interest in co-production and co-creation in the context of public administration in the last few years. This is particularly the case in Northern and Western Europe, where Anglo-Saxon and Nordic administrative traditions dominate. Furthermore, the results show that co-creation is most often placed in the contexts of social policy and welfare, as well as health care. Over the selected period, research seldom addressed companies as a target group in the co-creation of public services—in comparison to citizens and internal users. More than three quarters of the papers observed were empirical and less than 20% were quantitative. In general, a lack of conceptual clarity was often identified through the interchangeable usage of the terms co-creation and co-creation and the low level of international comparison—the majority of the papers focused on case descriptions at a national level, even though collaborative innovation is strongly related to administrative traditions dominating in specific regions.

1. Introduction

Collaborative innovation is ‘the new black’—the new buzz concept that is expected to provide a solution to the ‘wicked’ problems the public sector is facing today (Hartley et al. 2013; Agger and Lund 2017; Torfing 2019). It refers to “a process of creative problem solving through which relevant and affected actors work across formal institutional boundaries to develop and implement innovative solutions to urgent problems” (Sørensen and Torfing 2018, p. 394). Thus, collaborative innovation implies the inclusion of a number of different actors and the exploitation of their potential (e.g., knowledge, skills, and resources) with the purpose of finding a solution to societal problems and creating public value (Agger and Lund 2017). The actors implied here are public and private subjects that are either affected by the problem or in possession of the relevant knowledge and resources to contribute to an innovative solution (Torfing 2019). In addition, collaborative innovation also implies an inherent inclination to “disturb established practices and conventional thinking in a particular domain” (Sørensen and Torfing 2017, p. 828).

This, however, does not mean that collaborative innovation automatically leads to improvement as an inevitable outcome; it rather aims to capture a process that endeavours to solve a problem in a different, i.e., new way (Van Dijck et al. 2017). Thus, the key emphasis here is placed on the goal and the intention of collaborative innovation to bring novelty, rather than on the result as such. This is due to the high contingency of the process which does not allow “any reference to outcomes” (Sørensen and Torfing 2018, p. 391).

Specifically in the context of the public sector, two types of collaborative innovations can be identified: collaborative innovation with internal stakeholders and collaboration with external stakeholders (Van Dijck et al. 2017)—the latter also known as co-production and/or co-creation (Agger and Lund 2017; Van Dijck et al. 2017; Torfing 2019). Co-production and co-creation are concrete forms of collaborative innovation that aim to instigate “novel ways of creating and providing public services” (Agger and Lund 2017, p. 17). As such, they presume the inclusion of external actors (e.g., citizens, third-sector organisations and/or business)—beyond ‘classical’ participation and consultation—implying active and substantial contribution to the work of the organisation and creation of public value. Thus, these concepts redefine the ‘monopolistic’ role of the public sector, i.e., of a public organisation, from the sole creator and provider of public services to ‘one of the many in the team.’

This paper aims to analyse the state of the art and potential research trends in the relevant literature with regard to the above two popular concepts of collaborative innovation, i.e., co-creation and co-production. They emerge as a response to the increasing political and academic interest in these two concepts—the latter being evident from the recent proliferation of research on co-creation and/or co-production in the context of public policy, public management, and public administration/administrative science, while the former is noted in the political discourse at the international level, in particular within the frameworks of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the European Union (EU).

Coincidentally (or not), in the aftermath of the economic crisis, the OECD (2011) has become the ideational ‘pioneer’ of the introduction and promotion of the idea of co-creation in the ‘mainstream’ political discourse, while the EU has established itself as the main financial sponsor of this idea. Moreover, the EU has embraced co-creation as a bottom-up approach that fosters the culture of experimentation and leads to tailor-made solutions, growth, and legitimacy (EU Commission 2012, 2013; European Committee of the Regions 2017), and has thus made significant efforts to diffuse this idea, at both international and national levels. Namely, the Union finances the work of the Observatory of Public Sector Innovation (OPSI 2019)—the main ‘culprit’ for the adoption of the OECD Declaration on Public Sector Innovation, signed by 40 countries (OECD 2019)—as well as five projects under the auspices of the Horizon 2020 programme, which are explicitly related to the idea of co-creation (Co-VAL 2018).

Hence, we find it provoking to analyse whether the academic interest in these new concepts (co-creation and/or co-production) is coincidental or linked to the general political ‘mood’; precisely, whether co-creation is a policy-driven topic (i.e., driven by national or transnational organisations and programmes) or a result of the individual research interests/ambitions of researchers. Moreover, bearing in mind the newness of these concepts, we find it important to map and evaluate the methodological frameworks of the relevant research with a view to the practical added value of its results/inputs. Also, we are interested in analysing whether there is a specific administrative tradition prone to these ideas, i.e., co-creation and/or co-production, or they are universally popular as promising concepts in different administrative contexts.

To enlighten these dilemmas, we have decided to ‘scan’ the state of the art of the relevant research on co-creation and/or co-production in the public sector. Thus, to capture the dominant trends and to better understand the context in which these concepts are analysed, we conducted a content analysis (CA) of 139 Web of Science (WoS) articles published over the past 10 years. The goal of the CA analysis was to give an answer to the research question: What is the state of research in the field of co-creation/co-production in the public administration domain after the 2008 economic crisis?

Given the general definition of our research question, we deduced five specific subquestions:

- What is the dynamic of research in the field of co-creation/co-production in terms of an increasing or decreasing trend in the number of papers focused on this topic?

- Is co-creation/co-production research policy-driven by national or transnational research institutions and programmes?

- In which regions/administrative traditions is co-creation/co-production the most current research topic?

- What are the methodological characteristics of research in the field of co-creation/co-production?

- What are the content characteristics of research in the field of co-creation/co-production in terms of public policy fields in which the concept of co-creation/co-production is studied and the target groups addressed?

To answer these questions, in the following section we discuss the concepts of co-production and co-creation based on the definitions and conceptual properties identified in the relevant literature. In the third section, the results of the content analysis of the Web of Science (WoS) papers published between 2009 and 2018 are presented. Finally, in the last section, the results are discussed, the research questions addressed, and suggestions for further research given.

2. Definition(s), Conceptual Properties, and Problems of Co-Production and Co-Creation

Although initially established in the 1970s, co-production has (re)gained prominence only after the 2008 economic crisis and the politics of austerity (OECD 2011; Sicilia et al. 2016; Nesti 2018). In this context, co-production has been ‘advertised’ as a strategy capable to improve the quality of public services, better target public services, make them more user-responsive, cut costs, create synergies between government and civil society, address the problem of the democratic deficit, and contribute to citizens’ empowerment, as well as active citizenship (Osborne et al. 2016; Sicilia et al. 2016). These expectations have emerged also as a reflection to the recent shift of the academic interest and narrative from the tenets of New Public Management to the ideas of the New Public Service approach and New Public Governance. As such, the ‘mantra’ on effectiveness, if not replaced, has been complemented with the ideas of citizens’ empowerment and ownership, as well as democratic renewal (Ryan 2012; Griffiths 2013; Cepiku and Giordano 2014; Fledderus et al. 2014; Fledderus 2015; Bartenberger and Sześciło 2016; Osborne et al. 2016; Vennik et al. 2016; Howlett et al. 2017; Kekez 2018; Nesti 2018).

However, in spite of great political and academic interest, there has been a lack of ideological clarity and consistency regarding the idea of ‘co-production.’ As Durose and Richardson (2016, p. 35) rightly observe, co-production has been “pressed into service in support of many wildly different causes.” As such, it has been used as an argument all over the ideological spectrum—by the proponents of right-wing economic policies trying to delegitimise ‘big governments,’ to the proponents of the theories of communitarianism and social capital (Durose and Richardson 2016). Thus, some authors (e.g., Fledderus et al. 2015; Selloni 2017) have warned of the danger of co-production being ‘hijacked’ by governments to justify the current status quo and dismantle the welfare state, instead of strategically renewing the public sector for the benefit of better quality of life for the majority of citizens.

These fears are not without foundation. ‘Cost reduction,’ which is considered to be one of the main advantages of co-production (Gebauer et al. 2014; Howlett et al. 2017), could at the same time represent its main weakness. It might be the only motivation for governments to embrace this concept, as a ‘fancy’ disguise of the intentional destruction of the welfare state and a ‘scientific’ argument for the shift of the costs onto users and citizens (Cepiku and Giordano 2014). These fears, however, should not be (mis)used for discarding the adoption of collaborative arrangements per se (ibid.), but they need to urge the establishment of precautionary (institutional) measures and safeguards that will prevent such a scenario. Regardless of possible pitfalls, some authors (e.g., Durose and Richardson 2016) see strong transformational, if not radical, potential in this concept. Not only it can mobilise communities and create opportunities for social action, but it “allows the possibility of ‘active subjects’ who can resist the reproduction of state power and articulate and implement alternative agendas” (Durose and Richardson 2016, p. 37).

Unfortunately, the ideological ambiguity is not the only problem that stands in the way of full realisation of the potential of this concept. Equally, if not more problematic, is the lack of conceptual clarity as to what ‘co-production’ stands for. This leads to ‘conceptual stretching’ manifested as interchangeable use of this term with the term ‘co-creation,’ as well as with related concepts designating other forms of collaboration.

Even a brief glance at the relevant literature on co-production reveals that this term covers a number of different phenomena. For the purpose of this argument (on the ‘conceptual stretching’), we have systematised these different meanings into three categories of definitions of co-production:

- General definitions;

- Definitions confined to the delivery phase of the service production process; and

- ‘All-encompassing’ definitions of co-production.

The first group of definitions (Poocharoen and Ting 2015; Bovaird et al. 2016; Farr 2016; Loeffler and Bovaird 2016; Tu 2016; Kershaw et al. 2017; Moon 2018) refers either specifically to, or can be considered a variation of, the Ostrom’s definition of co-production as a “process through which inputs used to produce a good or service are contributed by individuals who are not ’in’ the same organisation” (Kershaw et al. 2017, p. 20). Without specifying the phase of the production process, the emphasis here is placed on the actors of the process (i.e., professionals, citizens, clients, consumers, community organisations), who are making better use of each other’s assets, resources, and contributions to achieve better outcomes or improved efficiency (Poocharoen and Ting 2015; Bovaird et al. 2016, p. 49).

The second group of definitions places co-production explicitly at the delivery phase of the service production cycle (Ryan 2012; Pestoff 2014; Alford 2014; Thijssen and Van Dooren 2016; Oldfield 2017; Vennik et al. 2016; Nesti 2018), while the third group sets co-production beyond this phase, at both strategic and operational levels, within the development, design, management, delivery, and/or evaluation phase of the production process (Dunston et al. 2009; Hardyman et al. 2015; Osborne et al. 2016; Williams et al. 2016; Palumbo and Manna 2018). Also, precisely this third group of definitions creates the most confusion, which prevents us from differentiating the concept of co-production from its significantly less defined ‘counterpart’—co-creation. The problem arises from the fact that ‘co-creation,’ similarly as ‘co-production’ (in its broader meaning), aims to capture the active involvement of end-users “in various stages of the production process” (Voorberg et al. 2015, p. 1335), such as the initiation and/or design phase of public services (Nemec et al. 2017; Voorberg et al. 2017).

Despite this overlapping of definitions and the interchangeable use of these terms, there are some specific features indicating that these two concepts should not be treated as synonyms. Firstly, co-creation puts an emphasis on value creation as the main intention and result of collaboration (Gebauer et al. 2014; Farr 2016; Putro 2016; Torvinen and Haukipuro 2018). Secondly, co-creation presumes a more active relationship among actors and constructive exchanges of different types of knowledge, skills, ideas, and resources, at a higher (e.g., meta, strategic, or policy) level of change, beyond the service level usually implied in the case of co-production (Sevin 2016; Edelenbos et al. 2018; Torvinen and Haukipuro 2018; Touati and Maillet 2018). In spite of these specifics, setting clear criteria for distinguishing between these intertwined concepts has been an enormous challenge for scholars.

For instance, Voorberg et al. (2015, p. 1348) suggested “the role of the citizen” as the main criterion for differentiation between the concepts of co-production and co-creation. Accordingly, co-creation would equal citizens’ involvement at the (co-)initiator or co-design level, while co-production would refer to citizens’ involvement in the (co-)implementation of public services. Moreover, some authors (e.g., Hardyman et al. 2015) referred to co-production only as a component of the process of co-creation of value, while others (Torfing et al. 2016) recognised innovation, i.e., transformation as the key difference that distinguishes these concepts. According to the latter distinction, co-creation implies a transformation of the very understanding of a problem or task, which leads to new innovative possibilities for its solution. In contrast, the purpose of co-production is less ambitious, as the interaction between users and providers is to produce and deliver a service which, although it may be adjusted and improved, is not subject to innovation in terms of development and realisation of new disruptive ideas (Torfing et al. 2016).

Finally, we need to mention co-governance and co-management as additional concepts that (could) add to the conceptual ambiguity and confusion around the terms of co-production and co-creation. In the context of creation of innovative, personalised public services, co-governance, and co-management are referred to as the framework that (dis)enables the synergy of different actors’ knowledge and resources (Lindsay et al. 2018). According to Lindsay et al. (2018), co-governance and co-management both serve as important facilitators of co-production. While co-governance features the level of definition of broad programme aims and priorities, co-management refers to the operational level, where materialisation of such broader aims occurs through joint management of resources, design, and delivery of public services. However, if these concepts—co-governance and co-management—refer to the framework and thus to the very process of collaboration, what is left for the definitions of co-production and co-creation? Does this imply that the latter concepts refer specifically to the outcome of the collaborative process—co-creation as the outcome of co-governance and co-production as a result of co-management?

Poocharoen and Ting (2015) provide some guidelines for the resolution of this dilemma by referring to co-governance and co-management as sub-concepts of co-production. Namely, in this case, co-governance and co-management are specifically referred to as arrangements that allow the third sector to participate in the planning and delivery of the service formerly or normally produced by public service professionals, while co-production is recognised as the very production of services by third-sector organisations in collaboration with government agencies. Accordingly, co-governance and co-management refer only to the organisational, i.e., structural aspect of the process, while co-production captures the process per se. However, this does not offer a satisfactory solution as it fails to refer to the place of co-creation within this setting.

Similar conceptual overlapping is noted regarding co-design (Burkett 2012), but here, the conceptual lack of clarity and the overlapping, as well as the loose basis for its establishment as a separate concept from the ‘generic’ concept ‘design,’ have not been exposed as problems (Burkett 2012; Steen 2013; Trischler et al. 2018; Zamenopoulos and Alexiou 2018). A possible interpretation is that conceptual vagueness is not necessarily bad, as it can act as a potential driver for the constant development of the concept.

Nevertheless, ‘revolutionary’ concepts such as co-production and/or co-creation are not only claimed to justify their very existence as separate concepts, but clearly show the potential for the introduction of novelty in theory and practice—which is impossible without a clear definition and differentiation of their basic conceptual properties. On this basis, we conclude that, in spite of individual efforts, the ‘conceptual mess’ cannot be addressed until the concepts of co-production and co-creation are clearly defined. Once they are defined, they need to be delimitated, initially in relation to each other and, later, vis-à-vis other ‘co-’ concepts. This paper does not aim to solve this conceptual puzzle, but to provide an informed theoretical basis for more consolidated future academic debate and contribution in this regard.

3. Co-Creation and Co-Production: Content Analysis of WoS Papers

3.1. Related Work

Content analysis (CA) is “a research technique for the objective, systematic, and quantitative description” of communication messages (Berelson 1952, p. 18). Although the use of CA can be traced back to the 18th century (Stroud and Higgins Joyce 2011), it is considered to be a relatively new method formalised and popularised between 1930 and 1940. Namely, CA established itself as a full-fledged scientific method during World War II, within the framework of a US-sponsored project on evaluation of enemy propaganda (Prasad 2008). Later, differently from its initial purpose, it was applied to different disciplines (Woodrum, in Prasad 2008), such as sociology, psychology, and business (Neuendorf 2002).

In the context of Public Administration (PA) research, CA was initially used as a tool for analysing the quality of doctoral dissertations in this field (Lee et al. 2009) and, later, as a frequent method for research of papers by many researchers. Understandably, there are different approaches to CA depending on the journal, the number of papers analysed, and the parameters observed. The goal of some CAs is to identify the characteristics of PA research in a specific region (Cheng and Lu 2009), others tend to evaluate the methodological aspects of PA research in great detail (Lee et al. 2009), while most of them try to categorise the papers in predefined topics that constitute the PA discipline (Bingham and Bowen 1994; Terry 2005; Kovač and Jukić 2016). Also, some CAs try to identify different trends in PA research in different time periods (Perry and Kraemer 1986; Henderson and Terry 2014; Walker et al. 2014).

On the other hand, a CA of co-creation in the field of PA has been weakly addressed before. According to our knowledge, only one such work was conducted, namely by Voorberg et al. (2015). They provided an ambitious systematic literature review of articles and books published in a time range of 25 years (1987 to 2013). Although they contributed significantly to our understanding of these concepts, by determining the objectives, influential factors, and outcomes of co-creation and co-production, we still recognise some limitations and ‘blind spots’ that need to be addressed. Namely, their literature review refers predominantly to a period before the effects of the economic crises were felt and before international organisations such as the OECD and the EU explicitly endorsed this concept (OECD 2011; EU Commission 2012, 2013) as an answer to present problems. We believe that context is an important factor that shapes the very idea of collaborative innovations in the public sector, i.e., its conceptual properties and objectives. Moreover, there has been a significant academic shift from the tenets of New Public Management, which enjoyed undisputed reputation during the 1990s (and to an extent in the 2000s), the period predominantly covered by the Voorberg et al. (2015) research.

Moreover, Voorberg et al. (2015) noted the problem of lack of conceptual clarity, which we believe would be interesting to revisit in a changed political context featured by active (ideational and financial) international sponsorship of these ideas. Moreover, the latter indicates an additional important aspect that was overlooked by Voorberg et al. (2015), that is, the financial source of the development and diffusion of these ideas.

Nevertheless, the CA of Voorberg et al. (2015) provides valuable insight into the situation and features of the research on collaborative innovation for a considerably long timespan. Namely, they identified the main policy sectors for co-creation/co-production practices—education and healthcare sector. Moreover, their analysis indicated some methodological limitations of our knowledge about co-creation/co-production, built predominantly on data deriving from single case studies, and thus lacking a comparative perspective. An additional problem is the lack of quantitative at the expense of qualitative research methods (e.g., interviews and document analysis). However, the main shortcoming (along with the problem of the lack of conceptual clarity) pointed out by Voorberg et al. (2015) was the lack of research interest in the outcomes, i.e., specific results of the co-creation/co-production process.

Our goal here is not to replicate the methodology of Voorberg et al. (2015), but to provide an original contribution to the literature on collaborative innovation (with special focus on co-creation and co-production) by identifying the general research trends in this area, in the period after the economic crisis to the present time (providing a relatively consistent context in ideational, political, and economic terms).

3.2. Methodological Framework

In order to analyse the research trends in relation to co-creation, we conducted a content analysis of the Web of Science (WoS) papers. The WoS database was selected for three reasons: (1) overlapping articles in WoS and Scopus databases—according to some studies (e.g., Sousa Vieira and Ferreira Gomes 2009), two-thirds of the articles are included in both databases; (2) higher impact of WoS articles (Aghaei Chadegani et al. 2013); (3) strong coverage dating back to 1990, with the majority of papers written in the English language (Aghaei Chadegani et al. 2013).

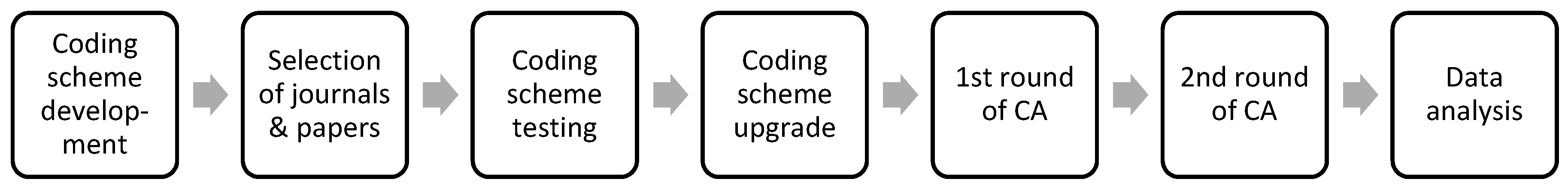

The methodological framework of the analysis consisted of seven steps (Figure 1). In the first step, we developed a coding scheme consisting of 12 parameters organised into the following categories (a detailed coding scheme is available in the Appendix A):

Figure 1.

Methodological framework of the content analysis. CA: content analysis.

- 1.

- Paper descriptors

- Journal title

- Paper title

- Year of publication

- Family names of authors

- Countries of authors’ affiliations

- 2.

- Methodological framework

- Methodological approach (theoretical/empirical)

- Type of empirical research (quantitative/qualitative)

- Data gathering methodology

- Geographical focus (national/comparative)

- 3.

- Field of co-creation/co-production implementation

- 4.

- Co-creation/co-production target group

- 5.

- Financial support of the research (funding from the EU, national institutions or other entities)

In the second step, the papers (and journals) included in the CA were identified with the following search criteria:

- 6.

- Timespan between 2009 and 2018

- 7.

- Including co-creation OR co-production

- 8.

- Published in the (WoS) public administration field.

Using these criteria, we identified 155 papers. During the analysis, we excluded 16 papers that did not address co-creation/co-production in the context of (core) public administration, leaving 139 papers to be analysed with the CA method.

In the following two steps, we tested and upgraded the coding scheme based on the (initial) CA of 25 papers. Next, the first round of the CA was conducted. In the sixth step, researchers switched papers and carried out a second round of the CA. Finally, data was analysed.

To formalise the procedure according to the CA types, we combined both manifest as well as latent CA approach in order to address the research questions appropriately. The latent CA of manifest content was necessary, both in order to get reliable and valid results, as well as to properly address the research questions of the papers. Moreover, the combination of different CA approaches and types was guaranteed also by the methodological literature focusing on CA (Krippendorff 2004; Pashakhanlou 2017).

3.3. Presentation of the Results

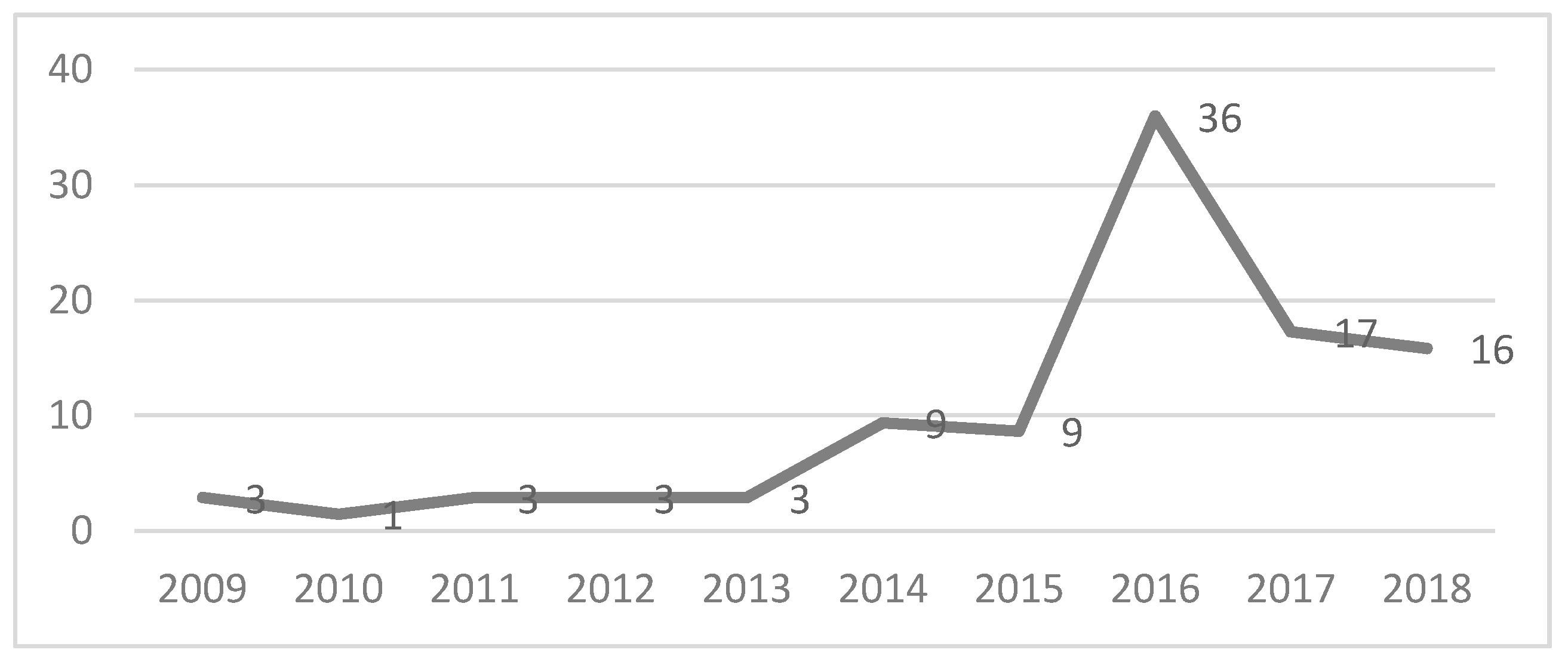

The analysis reveals that co-creation was recognised as an important mechanism in the operation of public administration in the last few years—most of the papers (69%) were published in 2016 or later (Figure 2). The reason for a high increase of papers in 2016 (36 papers published) lies in the fact that 17 papers in that year were part of the book devoted to designing public policy for co-production. This does not change the fact that co-creation/co-production is a topic that received significant attention from researchers over the last three years.

Figure 2.

Distribution of the papers based on the year of publication in % (n = 139).

Since co-creation plays an important role in the EU Horizon 2020 programme, we additionally searched for references regarding the funding of the research presented in the papers. In fact, one could argue that the topic of co-creation is policy-driven if the papers were funded by the EC or other (national) research programmes. The results show that this holds true only partially (Table 1). Namely, the EC (co-)funded only 4% of the research. This, however, is expected to change as five Horizon 2020 projects explicitly linked to co-creation are being implemented at the moment: COGOV, Citadel, TROPICO, Enlarge and CO-VAL (funded under the call CULT-COOP-2017). Therefore, in the near future, we might observe an increased percentage of EU-funded papers, indicating the EU’s (indirect) influence on the agenda and narrative on strategic renewal of the public sector.

Table 1.

Sources of funding of the research presented in the papers (n = 139).

Almost one-third (31%) of the research published in the analysed WoS papers was (co-)funded by national research institutions. This does not necessarily imply that the topic of co-creation is policy-driven, as the national research schemes are organised very differently: some in a way that the research topics are given in advance by the research funder, others in a way that researchers (research organisations) suggest the research topics. Moreover, national funding research schemes are designed either in broader terms (without specifically requiring the application of a certain theoretical concept) or are confined to a specific policy area (health, education, etc.). In any case, it is impossible to draw conclusions about the correlation between national research schemes and the promotion of the concept of co-creation (i.e., to claim that co-creation is policy-driven).

The analysis of the journals in which the 139 papers were published reveals that 19% of the papers were published in the Public Management Review. This, however, does not indicate that co-creation and co-production are most frequently addressed through the lenses of public (or strategic) management; namely, several papers do not fall strictly into the public management domain, but could, from the topical point of view, easily be published in any other public administration journal. Also, it is worth mentioning that only 12 papers contained, among the key words listed, the word “management” or derived phrases (such as transition management, dynamic performance management, neighbourhood management, management capacity, etc.). Even more so, only a few papers addressed co-production or co-creation together with public management, and not even one paper contained “strategic management” in its key words listing. This means that public/strategic management and co-production/co-creation are not focused on hand-in-hand (as indicated in the description of this special issue), but completely separately.

Regarding the geographical regions of authors’ affiliations, the CA reveals that almost two-thirds of the authors dealing with co-creation and co-production are based in Northern (41%) and Western (17%) Europe (Table 2). The concept of co-creation is often referred to as the core idea or key feature of the New Public Governance (NPG) model, which represents the upgrade or continuation of the New Public Management (NPM) model—a model that has its roots in the Anglo-Saxon administrative tradition. This is why the results (Table 2) are not surprising, as the Anglo-Saxon administrative tradition prevails in the countries in these regions. These findings also correspond to the earlier research confirming that co-production is easier to implement in countries with pluralistic administrative traditions, exemplified by the Anglo-Saxon tradition, and in countries with administrative traditions with more autonomous citizens, exemplified by the Nordic tradition of public administration (Parado et al. 2013).

Table 2.

Geographical positions of the authors in the field of co-creation and co-production (n = 324 *).

Table 3 reveals that co-creation, in the WoS research, is most frequently addressed in the fields of social policy and welfare (20%), followed by health (16%). These are the two policy areas most sensitive to societal changes. Moreover, a potential explanation for this bias might also lie in the nature of these services, which have very individualised benefits and are, as such, prone to co-creation initiatives. In this regard, if we follow more generalistic literature on co-creation (see, e.g., Prahalad and Ramaswamy 2000), the context becomes also personalisation, where the users/customers/citizens are given the possibility to become the co-creators of the content.

Table 3.

Policy fields in which co-creation and co-production are most often addressed (n = 139).

A look at target groups in the process of co-creating public policies and services shows that, in the last decade, the authors of WoS papers focused primarily on internal users (39%) and on the citizens as external users (39%) (Table 4). It seems very interesting to us that businesses as external users are focused on much more rarely (7%), although they are generally more in touch with the public administration than citizens and may be more motivated for co-creation than citizens (e.g., in the field of economic policy and tax services).

Table 4.

Co-creation and co-production target groups addressed in the WoS papers (n = 139).

What does come as a surprise, in light of this argument, is the significantly higher percentage of empirical research compared to theoretical. Namely, a new and ambiguous concept is expected to be subject to more theoretical discussion in order to address the problem of lack of clarity and thus to provide a more solid theoretical basis for future empirical research.

Nevertheless, authors were more interested in empirical research of (their own understanding of) co-creation than in clarifying the conceptual ‘mess’ and providing a unified definition on co-creation. A potential reason for this could be that clarification of conceptual properties of a new theoretical concept is a much more ambitious challenge than the empirical analysis (of a vaguely defined term). In line with this logic also stands out the observation that most empirical articles (78%) rely on qualitative methods (e.g., interviews, focus groups, literature review/document analysis, and case study analysis) in comparison to only 17% of articles relying on quantitative research (Table 5). Interestingly, only 14% of the papers included a comparative dimension of co-creation/co-production, while 65% of them focused on description of co-creation at the national level.

Table 5.

Methodological framework of the papers (left—theoretical vs. empirical, right—quantitative vs. qualitative).

4. Discussion and Suggestions for Future Research

Collaborative innovation is considered one of the main characteristics of the New Public Governance, in which citizens (and other PA stakeholders) are considered as equal partners to PA organisations. In addition, it is often considered as a potential method in overcoming societal challenges—environmental, health (ageing), social. In the past five years, strong political interest in collaborative innovation (and, more precisely, in co-creation and co-production as the two main types of collaborative innovation) was accompanied by strong academic interest as well. This is reflected in the growing number of research papers, monographs, national and EU (co-)funded projects. The first comprehensive CA in this field was conducted on the sample of 122 papers and books published between 1987 and 2013 (Voorberg et al. 2015). While our CA methodology differs from the one used by Voorberg et al. (2015), some rough comparisons (as given above) are still relevant.

At the beginning of this paper, a general research mechanism was raised “What is the state of research in the field of co-creation/co-production in the public administration domain after the 2008 economic crises?”

Given the general definition of our research question, we deduced five specific subquestions:

- 1.

- What is the dynamic of research in the field of co-creation/co-production in terms of an increasing or decreasing trend in the number of papers focused on this topic?

- 2.

- Is co-creation/co-production research policy-driven by national or transnational research institutions and programmes?

- 3.

- In which regions/administrative traditions is co-creation/co-production the most current research topic?

- 4.

- What are the methodological characteristics of research in the field of co-creation/co-production?

- 5.

- What are the content characteristics of research in the field of co-creation/co-production in terms of public policy fields in which the concept of co-creation/co-production is studied and the target groups addressed?

Regarding the first research subquestion, the CA of WoS papers published between 2009 and 2018 revealed that almost 70% of the papers were published in the last three years (i.e., in 2016 or later). The number of papers published in this field increased from 3 in 2009 to 36 in 2016 (and decreased to 17 and 16 in two subsequent years). Thus, it is evident that the topic of co-creation/co-production gained great importance in the past years.

In relation to the second research subquestion, further analysis revealed that increased interest in co-creation/co-production research is not necessarily policy-driven. Namely, while only 4% of papers observed were (co-)funded by the EU research programme(s), for those 31% funded by national institutions, it cannot be said for sure that these topics were set in advance (e.g., in calls for research proposals). However, it is expected that, in the next few years, the number of EU (co-funded) papers in the field of co-creation/co-production in the PA domain will increase due to the several projects funded under the Horizon 2020 programme, which are expected to deliver more scientific outputs in this field.

Regarding the third research subquestion, our analysis revealed that most of the authors in the field of co-creation/co-production are based in Northern and Western Europe, where the Anglo-Saxon administrative tradition predominates. Only 3% of the authors are based in Eastern Europe. Since the concept of co-creation is often referred to as the core idea or key feature of the New Public Governance (NPG) model, which represents the upgrade or continuation of the New Public Management (NPM) model—a model that has its roots in the Anglo-Saxon administrative tradition—, these results were not a surprise.

Regarding the methodological frameworks of the observed papers (fourth research subquestion), our results revealed that approximately three quarters of the papers were empirical and predominantly qualitative. Only 17% of the papers were based on the results of quantitative research and only 14% included a comparative perspective. These results are in line with the results obtained by Voorberg et al. (2015).

In relation to the fifth research subquestion, the CA revealed that the majority of the papers focused on co-creation/co-production in social policy and welfare and the health area—the two most challenging public policies in Europe at the moment. The analysis conducted by Voorberg et al. (2015) revealed a predominant focus on education and the healthcare sector. A look at the target groups in the process of co-creation/co-production shows that, in the last decade, the authors of WoS papers focused primarily on internal users (39%) and on the citizens as external users (39%), while only 7% of the papers observed in our CA addressed businesses as co-creators—although they are generally more in touch with the public administration than citizens and may be more motivated for co-creation than citizens (e.g., in the field of economic policy and tax services).

Based on our results and observations, which (where relevant) are in line with the results of previous CAs (Voorberg et al. 2015), some suggestions can be drawn for future research in the field of co-creation in the PA domain. First, the observed field of collaborative innovation (still) suffers from the lack of conceptual clarity mainly observed through the interchangeable use of the terms co-creation and co-production. While conceptual clarity does not seem of crucial importance in the emerging (research) areas, we believe that the number of research outputs in the field of collaborative innovation has grown to the extent where such clarity is inevitable. Second, more quantitative studies in this field are (still) welcome. While qualitative methodological frameworks offer an in-depth insight into the research problem, quantitative methodological paths should not be neglected. Qualitative analysis of individual case studies may offer a large amount of detailed and valuable data, but it does not reveal global trends in the field of co-creation—i.e., in which countries is co-creation most frequently used? In what types of organisations? In which public services? Furthermore, large-scale quantitative research, especially international, would also provide a starting point for the preparation of practical co-creation roadmaps for different administrative traditions—which cannot be done (solely) based on individual case studies. Third, more international benchmarking is needed in this research field. These could indicate different experiences in collaborative innovation applications in different administrative traditions, but also offer other useful insights/differences among PAs in different countries. Fourth, businesses as partners in collaborative innovation need to be taken into account more often. In general, they use PA service more often than citizens and may also be more motivated for co-creation than citizens (e.g., in the field of economic policy and tax services).

We believe that the CA presented in the paper is useful for other researchers and PA organisations. For both, the results presented here offer a concise overview of a growing research field (as well as a pool for future research ideas for researchers).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.J. and S.V.; methodology, T.J., S.V., M.D. and P.P.; investigation, S.V., T.J., P.P., M.D. and J.B.; resources: T.J.; formal analysis, T.J.; data curation, T.J.; writing—original draft preparation, T.J. and S.V.; writing—review and editing, P.P., M.D. and J.B.; visualization, T.J.; supervision, T.J.; funding acquisition, T.J.

Funding

This research received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No. 770591.

Acknowledgments

The initial results of the research were presented at the NISPAcee 2019 conference and we would like to thank the participants who gave us useful feedback enabling us to improve the results presented in this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study, in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Coding Scheme for Content Analysis

Paper descriptors

1. Paper ID

2. Journal title

3. Paper title

4. Year of publication

5. Family names of authors

6. Country of authors’ affiliation

Appendix A.2. Methodological Framework

7. Methodological approach

- Theoretical

- Empirical

8. Type of empirical research

- Quantitative

- Qualitative

- NA

9. Data gathering methodology (IF empirical):

- Case study

- Literature review/CA/Qualitative analysis of relevant documents

- Survey

- Interviews/focus groups

- Other

10. Geographical focus

- National

- Comparative

- NA

11. Field of co-creation/co-production implementation

- Health

- Environment

- Public safety

- Social policy and welfare (including housing policy)

- Education

- Culture

- Other

- NA

12. Co-creation/co-production target group (multiple answers possible):

- Internal users

- External users - citizens/clients

- External users - businesses

- External users - civil society/third-sector organizations

- Other

Appendix A.3. Financial Support of the Research

13. Reference to (co-)funding of the research

- the EU

- National institutions

- Other (private foundations; or explicit statement that no financial means were received for the research)

- Not identified

References

- Agger, Annika, and Dorthe Hedensted Lund. 2017. Collaborative Innovation in the Public Sector—New Perspectives on the Role of Citizens? Scandinavian Journal of Public Administration 21: 17–37. [Google Scholar]

- Aghaei Chadegani, Arezoo, Hadi Salehi, Melor Yunus, Hadi Farhadi, Masood Fooladi, Maryam Farhadi, and Nader Ale Ebrahim. 2013. A Comparison between Two Main Academic Literature Collections: Web of Science and Scopus Databases. Asian Social Science 9: 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alford, John. 2014. The Multiple Facets of Co-Production: Building on the Work of Elinor Ostrom. Public Management Review 16: 299–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartenberger, Martin, and Dawid Sześciło. 2016. The benefits and risks of experimental co-production: The case of urban redesign in Vienna. Public Administration 94: 509–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berelson, Bernard. 1952. Content Analysis in Communication Research. Glencoe: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bingham, Richard D., and William M. Bowen. 1994. “Mainstream” Public Administration over Time: A Topical Content Analysis of Public Administration Review. Public Administration Review 54: 204–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovaird, Tony, Gerry Stoker, Tricia Jones, Elke Loeffler, and Monica Pinilla Roncancio. 2016. Activating Collective Co-production of Public Services: Influencing Citizens to Participate in Complex Governance Mechanisms in the UK. International Review of Administrative Sciences 82: 47–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkett, Ingrid. 2012. An Introduction to Co-Design; Knode. Available online: https://www.yacwa.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/An-Introduction-to-Co-Design-by-Ingrid-Burkett.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2019).

- Cepiku, Denita, and Filippo Giordano. 2014. Co-Production in Developing Countries: Insights from the community health workers experience. Public Management Review 16: 317–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Joseph YS, and Lucia Q. Lu. 2009. Public Administration Research Issues in China: Evidence from Content Analysis of Leading Chinese Public Administration Journals. Issues & Studies 1: 203–41. [Google Scholar]

- Co-VAL. 2018. Available online: http://www.co-val.eu/blog/2018/10/25/co-val-at-the-cultural-cooperation-11-cluster-and-linked-eu-egovernment-initiatives-futurgov2030-workshop/ (accessed on 1 July 2019).

- Dunston, Roger, Alison Lee, David Boud, Pat Brodie, and Mary Chiarella. 2009. Co-Production and Health System Reform—From Re-Imagining to Re-Making Roger. Australian Journal of Public Administration 68: 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durose, Catherine, and Liz Richardson. 2016. Co-Productive Policy Design. In Designing Public Policy for Co-Production: Theory, Practice and Change. Edited by Catherine Durose and Liz Richardson. Bristol: Policy Press, pp. 33–50. [Google Scholar]

- Edelenbos, Jurian, Ingmar van Meerkerk, and Todd Schenk. 2018. The Evolution of Community Self-Organization in Interaction with Government Institutions: Cross-Case Insights from Three Countries. The American Review of Public Administration 48: 52–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EU Commission. 2012. Commission Staff Working Document Digital Agenda for Europe—A Good Start and Stakeholder Feedback Accompanying the Document. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions Digital Agenda for Europe—Driving European Growth Digitally/* SWD/2012/0446 Final */. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/en/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52012SC0446 (accessed on 27 June 2019).

- EU Commission. 2013. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions EU Quality Framework for Anticipation of Change and Restructuring/* COM/2013/0882 Final */. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/ EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52013DC0882 (accessed on 27 June 2019).

- European Committee of the Regions. 2017. Opinion of the European Committee of the Regions on Social Innovation as a New Tool for Addressing Societal Challenges (2017/C 306/06). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52016IR6945&from=EN (accessed on 27 June 2019).

- Farr, Michelle. 2016. Co-Production and Value Co-Creation in Outcome Based Contracting in Public Services. Public Management Review 18: 654–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fledderus, Joost, Taco Brandsen, and Marlies Elisabeth Honingh. 2015. User Co-production of Public Service Delivery: An Uncertainty Approach. Public Policy and Administration 30: 145–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fledderus, Joost, Taco Brandsen, and Marlies Honingh. 2014. Restoring Trust through the Co-Production of Public Services: A Theoretical Elaboration. Public Management Review 16: 424–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fledderus, Joost. 2015. Does User Co-Production of Public Service Delivery Increase Satisfaction and Trust? Evidence from a Vignette Experiment. International Journal of Public Administration 38: 642–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebauer, Heiko, Mikael Johnson, and Bo Enquist. 2014. Service Innovations for Enhancing Public Transit Services. In Framing Innovation in Public Service Sectors. Edited by Lars Fuglsang, Rolf Rønning and Bo Enquist. New York: Taylor & Francis, pp. 41–62. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, Mary. 2013. Empowering Citizens: A Constructivist Assessment of the Impact of Contextual and Design Factors on Shared Governance. In E-Government Success Factors and Measures: Theories, Concepts, and Methodologies. Edited by J. Ramon Gil-Garcia. Hershey: IGI Global, pp. 124–41. [Google Scholar]

- Hardyman, Wendy, Kate L. Daunt, and Martin Kitchener. 2015. Value Co-Creation through Patient Engagement in Health Care: A Micro-Level Approach and Research Agenda. Public Management Review 17: 90–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartley, Jean, Eva Sørensen, and Jacob Torfing. 2013. Collaborative Innovation: A Viable Alternative to Market Competition and Organizational Entrepreneurship. Public Administration Review 73: 821–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, Alexander C., and Larry D. Terry. 2014. Unpacking the Global Perspective: Examining NISPAcee Region-Focused Public Administration Research in American Scholarly Journals. International Journal of Public Administration 37: 353–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howlett, Michael, Anka Kekez, and Ora-orn Poocharoen. 2017. Understanding Co-Production as a Policy Tool: Integrating New Public Governance and Comparative Policy Theory. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice 19: 487–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kekez, Anka. 2018. Public Service Reforms and Clientelism: Explaining Variation of Service Delivery Modes in Croatian Social Policy. Policy and Society 37: 386–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kershaw, Anne, Kerrie Bridson, and Melissa A. Parris. 2017. Encouraging Writing on the White Walls: Co-production in Museums and the Influence of Professional Bodies. Australian Journal of Public Administration 77: 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovač, Polonca, and Tina Jukić. 2016. Development of public administration and its research in Slovenia through the lenses of content analysis of the International Public Administration Review. Mednarodna Revija za Javno Upravo 14: 75–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krippendorff, Klaus. 2004. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology, 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Geon, Jennifer Benoit-Bryan, and Timothy P. Johnson. 2009. Survey Methods in Public Administration Research: A Content Analysis of Journal Publications. Paper Presented at the 10th National Public Management Research Conference, Columbus, OH, USA, October 13. [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay, Colin, Sarah Pearson, Elaine Batty, Anne Marie Cullen, and Will Eadson. 2018. Co-production as a Route to Employability: Lessons from Services with Lone Parents. Public Administration 96: 318–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loeffler, Elke, and Tony Bovaird. 2016. User and Community Co-Production of Public Services: What Does the Evidence Tell Us? International Journal of Public Administration 39: 1006–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, M. Jae. 2018. Evolution of Co-production in the Information Age: Crowdsourcing as a Model of Web-based Co-production in Korea. Policy and Society 37: 294–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemec, Juraj, Mária Murray Svidroňová, Beáta Mikušová Meričková, and Daniel Klimovský. 2017. Co-Creation as a Social Innovation in Delivery of Public Services at Local Government Level: The Slovak Experience. In Handbook of Research on Sub-National Governance and Development. Edited by Eris Schoburgh and Roberta Ryan. Hershey: IGI Global, pp. 281–303. [Google Scholar]

- Nesti, Giorgia. 2018. Co-production for Innovation: The Urban Living Lab Experience. Policy and Society 37: 310–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuendorf, Kimberly A. 2002. The Content Analysis Guidebook. Thousand Oaks: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. 2011. Together for Better Public Services: Partnering with Citizens and Civil Society. Available online: https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/governance/together-for-better-public-services-partnering-with-citizens-and-civil-society_9789264118843-en#page3 (accessed on 15 April 2019).

- OECD. 2019. Declaration on Public Sector Innovation. Available online: https://oecd-opsi.org/wp-content/uploads/ 2018/11/OECD-Declaration-on-Public-Sector-Innovation-English.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2019).

- Oldfield, Chrissie. 2017. In Favour of Co-production. In Developing Public Managers for a Changing World. Edited by Klaus Majgaard, Jens Carl Ry Nielsen, Bríd Quinn and John W. Raine. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing LTD, pp. 83–102. [Google Scholar]

- OPSI. 2019. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/governance/observatory-public-sector-innovation/h2020/ (accessed on 27 June 2019).

- Osborne, Stephen P., Zoe Radnor, and Kirsty Strokosch. 2016. Co-Production and the Co-Creation of Value in Public Services: A Suitable Case for Treatment? Public Management Review 18: 639–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palumbo, Rocco, and Rosalba Manna. 2018. What if Things Go Wrong in Coproducing Health Services? Exploring the Implementation Problems of Health Care Co-production. Policy and Society 37: 368–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parado, Salvador, Gregg G. Van Ryzin, Tony Bovaird, and Elke Loeffler. 2013. Correlates of Co-production: Evidence from a Five-Nation Survey of Citizens. International Public Management Journal 16: 85–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pashakhanlou, Arash Heydarian. 2017. Fully integrated content analysis in International Relations. International Relations 31: 447–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, James L., and Kenneth L. Kraemer. 1986. Research Methodology in the Public Administration Review, 1975–1984. Public Administration Review 46: 215–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pestoff, Victor. 2014. Collective Action and the Sustainability of Co-Production. Public Management Review 16: 383–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poocharoen, Ora-orn, and Bernard Ting. 2015. Collaboration, Co-Production, Networks: Convergence of theories. Public Management Review 17: 587–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahalad, Coimbatore K., and Venkatram Ramaswamy. 2000. Co-opting Customer Competence. Harvard Business Review 78: 79–87. [Google Scholar]

- Prasad, Devi. 2008. Content Analysis—A method in Social Science Research. In Research Methods for Social Work. Edited by D.K. Lal Das and Vanila Bhaskaran. New Delhi: Rawat, pp. 173–93. [Google Scholar]

- Putro, Utomo Sarjono. 2016. Value Co-Creation Platform as Part of an Integrative Group Model-Building Process in Policy Development in Indonesia. In Systems Science for Complex Policy Making: A Study of Indonesia. Edited by Kuntoro Mangkusubroto, Utomo Sarjono Putro, Santi Novani and Kyoichi Kijima. Tokyo: Springer, pp. 17–28. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, Bill. 2012. Co-Production: Option or Obligation? Australian Journal of Public Administration 71: 314–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selloni, Daniela. 2017. New Forms of Welfare: Relational Welfare, Second Welfare, Co-production. In CoDesign for Public-Interest Services. Edited by Emilio Bartezzaghi and Giampio Bracchi. Gewerbestrasse: Springer International Publishing, pp. 27–36. [Google Scholar]

- Sevin, Efe. 2016. Branding Cities in the Age of Social Media: A Comparative Assessment of Local Government Performance. In Social Media and Local Governments: Theory and Practice. Edited by Mehmet Zahid Sobaci. Berlin: Springer, pp. 301–20. [Google Scholar]

- Sicilia, Mariafrancesca, Enrico Guarini, Alessandro Sancino, Martino Andreani, and Renato Ruffini. 2016. Public Services Management and Co-Production in Multi-Level Governance Settings. International Review of Administrative Sciences 82: 8–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, Eva, and Jacob Torfing. 2017. Metagoverning Collaborative Innovation in Governance Networks. American Review of Public Administration 47: 826–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, Eva, and Jacob Torfing. 2018. Co-initiation of Collaborative Innovation in Urban Spaces. Urban Affairs Review 54: 388–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa Vieira, Elizabeth, and José Ferreira Gomes. 2009. A comparison of Scopus and Web of Science for a typical university. Scientometrics 81: 587–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steen, Marc. 2013. Co-Design as a Process of Joint Inquiry and Imagination. Design Issues 29: 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroud, Natalie Jomini, and Vanessa D. M. Higgins Joyce. 2011. Content analysis. In Research Methods in Communication, 2nd ed. Edited by David Sloan and Shuhua Zhou. Northport: Vision Press, pp. 123–43. [Google Scholar]

- Terry, Larry D. 2005. Reflections and Assessment: Public Administration Review, 2000–05. Public Administration Review 65: 643–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thijssen, Peter, and Wouter Van Dooren. 2016. Who You Are/Where You Live: Do Neighbourhood Characteristics Explain Co-Production? International Review of Administrative Sciences 82: 88–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torfing, Jacob, Eva Sørensen, and Asbjørn Røiseland. 2016. Transforming the Public Sector into an Arena for Co-Creation: Barriers, Drivers, Benefits, and Ways Forward. Paper Presented at the EGPA 2016, Utrecht, The Netherlands, April 24–26. [Google Scholar]

- Torfing, Jacob. 2019. Collaborative innovation in the public sector: The argument. Public Management Review 21: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torvinen, Hannu, and Lotta Haukipuro. 2018. New Roles for End-users in Innovative Public Procurement: Case Study on User Engaging Property Procurement. Public Management Review 20: 1444–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touati, Nassera, and Lara Maillet. 2018. Co-creation within Hybrid Networks: What Can be Learnt from the Difficulties Encountered? The Example of the Fight against Blood- and Sexually-Transmitted Infections. International Review of Administrative Sciences 84: 469–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trischler, Jakob, Simon J. Pervan, Stephen J. Kelly, and Don R. Scott. 2018. The Value of Codesign: The Effect of Customer Involvement in Service Design Teams. Journal of Service Research 21: 75–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dijck, Charlotte, Vidar Stevens, Tom Langbroek, Cécile Riche, Koen Verhoest, Trui Steen, David Aubin, and Stéphane Moyson. 2017. Public Sector Innovation through Collaboration. Explaining Antecedents for Collaborative Innovation. Paper Presented at the 21st International Research Society on Public Management Conference, Budapest, Hungary, April 19–21. [Google Scholar]

- Vennik, Femke D., Hester M. van de Bovenkamp, Kim Putters, and Kor J. Grit. 2016. Co-production in Healthcare: Rhetoric and Practice. International Review of Administrative Sciences 82: 150–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voorberg, William H., Viktor J. J. M. Bekkers, and Lars G. Tummers. 2015. A Systematic Review of Co-Creation and Co-Production: Embarking on the Social Innovation Journey. Public Management Review 17: 1333–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voorberg, William, Victor Bekkers, Sophie Flemig, Krista Timeus, Piret Tõnurist, and Lars Tummers. 2017. Does Co-Creation Impact Public Service Delivery? The Importance of State and Governance Traditions. Public Money & Management 37: 365–72. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, Richard M., Gene A. Brewer, and Yujin Choi. 2014. Public Administration Research in East and Southeast Asia: A Review of the English Language Evidence, 1999–2009. American Review of Public Administration 44: 131–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, Brian N., Seong-Cheol Kang, and Japera Johnson. 2016. (Co)-Contamination as the Dark Side of Co-Production: Public Value Failures in Co-production Processes. Public Management Review 18: 692–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Xuan. 2016. Conditions for the Co-Production of New Immigrant Services in Hong Kong. International Journal of Public Administration 39: 1067–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamenopoulos, Teodore, and Katerina Alexiou. 2018. Co-Design as Collaborative Research. Bristol: University of Bristol/AHRC Connected Communities Programme. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).