Efficiency and Effectiveness of the European Parliament under the Ordinary Legislative Procedure

Abstract

1. Introductory Considerations

1.1. Purpose

1.2. General Considerations

“the “macro” effectiveness [targets] the impact of the action on the objectives of general interest to the company”

“the “micro” effectiveness (…) concerns the effects of local operations with reference to the strategy of the company”

2. Formulating the Assessment Indicators

2.1. Preliminary Considerations

2.2. Institutional Considerations

2.3. Formulating the Quantitative Indicators

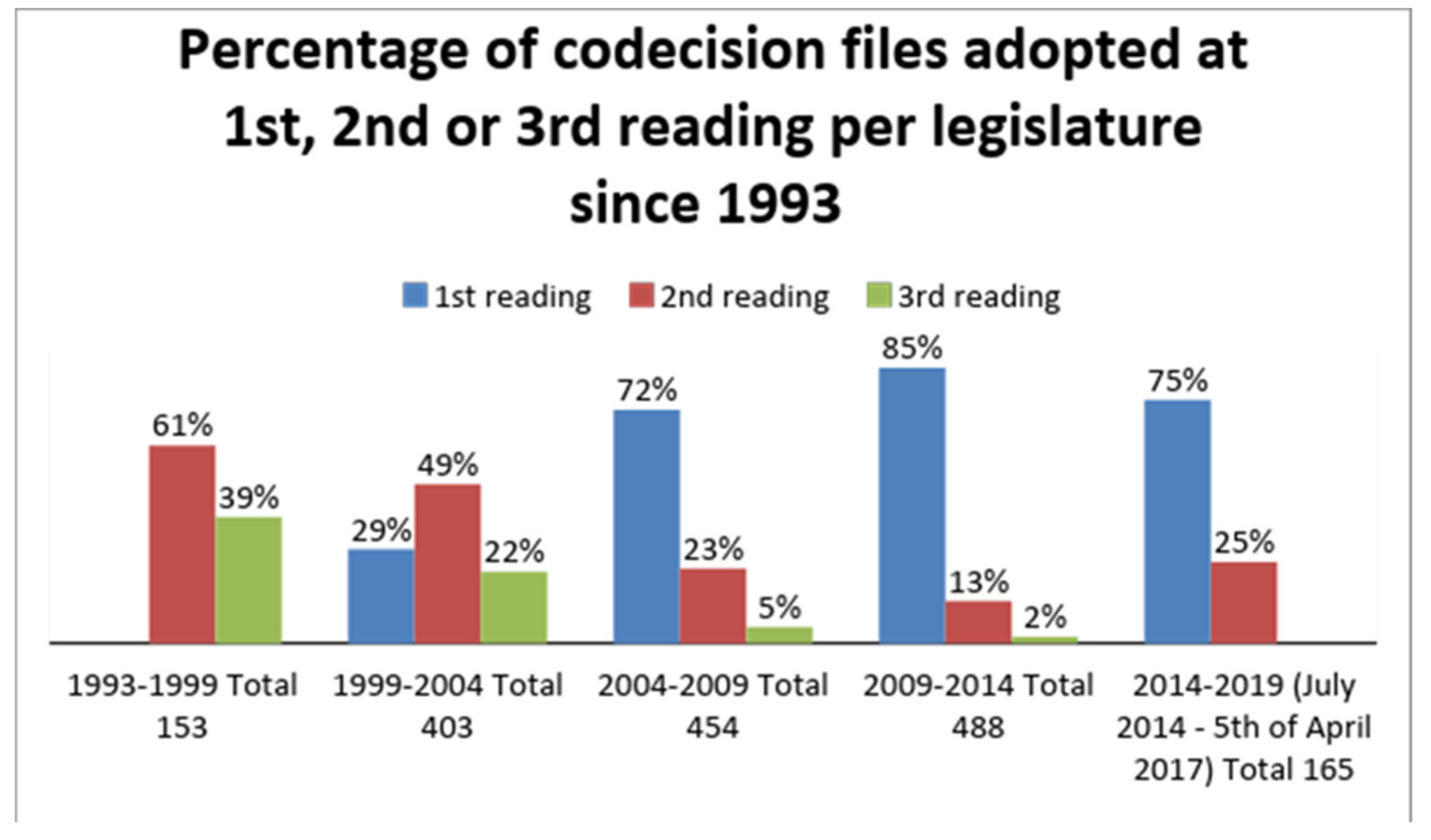

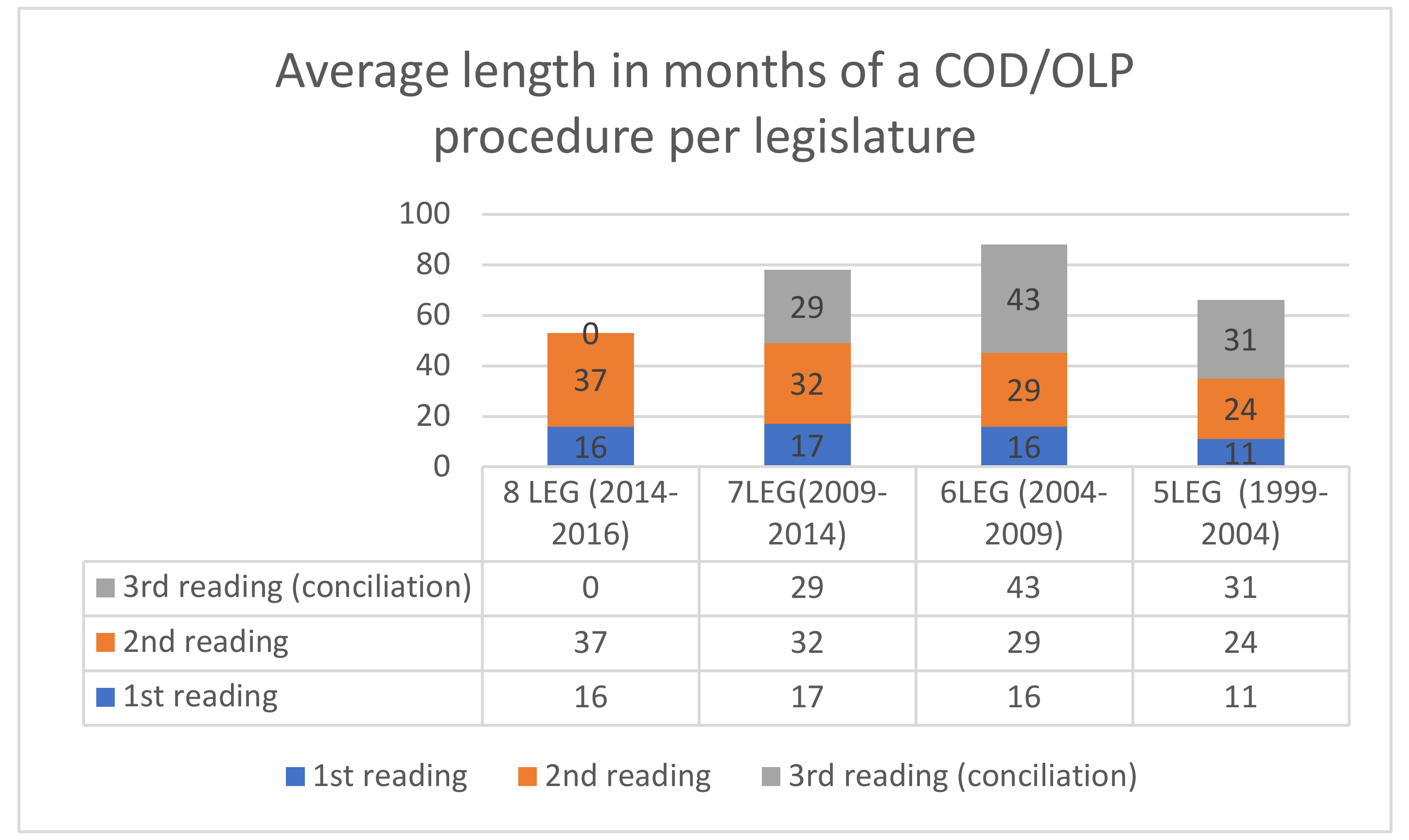

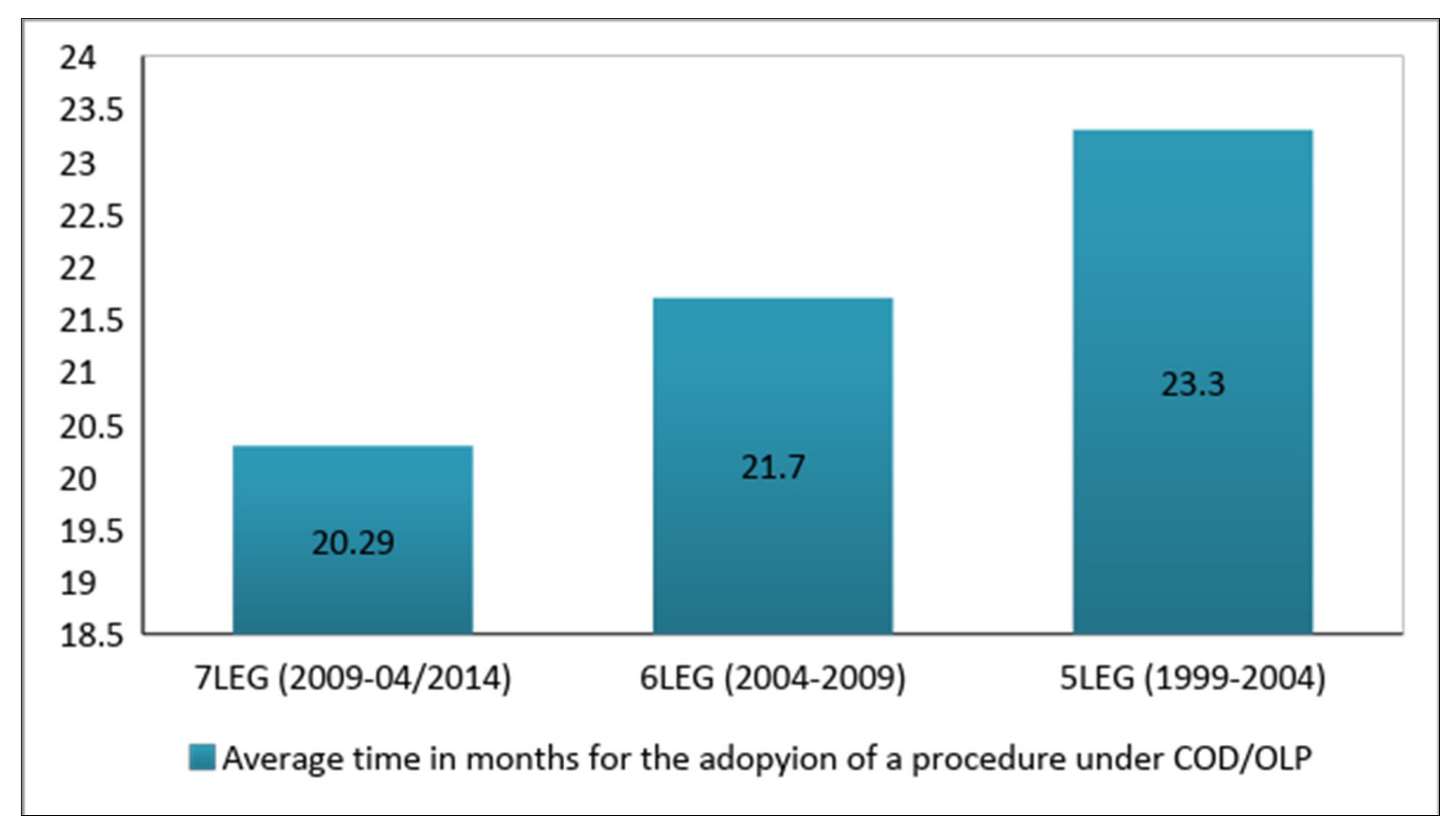

- per legislature

- per reading

- per parliamentary committee

- number of completed procedures

- number of procedures completed in the first or second reading

- decision-making time (length of procedure)

- number of obsolete or withdrawn procedures

- number of procedures with a duration of more than 10 years

- number of rejected procedures

- On the website of co-decisions and conciliations, the statistics present the procedures up to the date of signature.

- In the search engine of the Legislative Observatory (OEIL), those procedures whose acts have already been published or are awaiting publication in the Official Journal are considered complete.

- Various reports of the EP do not clearly specify when a COD/OLP is considered complete.

2.4. Formulating the Qualitative Indicators

- nature of the files

- quality of the legislation

- amendments tabled by the EP and taken over in the final text of the legislative acts

- technical on the substance and of substantial nature (relating to the strictly technical areas de facto regulated at the level of expert groups)

- technical on the form and of formal nature (in the case of codifying, consolidating or repealing legislative acts in the framework of the Strategy for better regulation)

- (a)

- Files of alignment to comitology consisting of adapting the existing legislation to the ‘regulatory procedure with scrutiny’

- (b)

- Files consisting of strictly technical adaptations, such as extending a certain transitional period (European Parliament 2009b, p. 7)

- (a)

- Purely political dossiers such as the Climate package (consisting of files such as the Regulation on the reduction of CO2 emissions produced by cars, the Emissions trading scheme, and the Regulation on cosmetics)

- (b)

- Sensitive files from a political point of view (such as LIFE+, Inspire, concluded on the third reading)

- (c)

- Generally, more-sensitive files from a political point of view, usually concluded on the second reading such as the Pesticides package or the two famous REACH pieces of legislation (the regulation and the directive)

3. Assessment of the Legislative Work of the European Parliament in COD/OLP

3.1. Quantitative-Qualitative Assessment of the EP’s Legislative Activity

- (1)

- Environment: public’s right of access to information, right to participate in decision-making and right to justice (Aarhus Convention-2003/0246 (COD))

- (2)

- Travel services: indirect taxation (VAT), administrative cooperation-2003/0057 (COD)

- (3)

- Oil pollution: fund for damage compensation in European waters, Erika II package-2000/0326 (COD)

3.2. Assessing the Qualitative-Quantitative Legislative Activity of the European Parliament

- (a)

- 46 of the 83 dossiers concluded by Committee on Legal Affairs (JURI) were legal codifications concluded on first reading (European Parliament 2009b, pp. 8, 11).

- (b)

- 54 dossiers concerned the comitology alignment (to the new regulatory procedure with scrutiny).

- (c)

- 6 were repealing dossiers (European Parliament 2009b, p. 9).

- (1)

- on the one hand, to the disastrous consequences for public opinion from the crises that have marked food safety and public health (such as mad cow disease and the avian flu), causing intense legislative activity in these areas, and

- (2)

- on the other hand, particularly during the fifth and the sixth legislature legislatures, to the emergence of themes related to environment and energy and to the need to promote a ‘Europe of concrete projects.’

4. Final Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bărbulescu, I.G. 2015. Noua Europă [The New Europe]. Iaşi: Polirom. [Google Scholar]

- Bousta, Rhita. 2010. Essai sur la Notion de Bonne Administration en Droit Public. Paris: l’Harmattan. [Google Scholar]

- Ciora, Cristina. 2013. 20 Years of European codecision. Evolution and assessment. In Annals of the Constantin Brâncuşi University Juridical Sciences Series. Tartu: Academica Brancusi Press, vol. 3, pp. 201–20. [Google Scholar]

- Corduban, C. 2015. Abordare Managerială a Procedurii Legislative Ordinare Europene. Managerial Approach of the European Ordinary Legislative Procedure. Ph.D. Thesis, NSPSPA, Bucharest, Romania. [Google Scholar]

- Craig, Paul, and Grainne De Burca. 2011. EU Law: Text, Cases, and Materials. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dehousse, Franklin R. 2011. The Reform of the EU Courts: The Need of a Management Approach; Egmont Paper, No. 53. Brussels: Academia Press. Available online: http://www.egmontinstitute.be/paperegm/ep53.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2018).

- Drucker, P. 1994. Eficienţa Factorului Decizional. Deva: Ed. Destin. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. 2001. The White Paper on European Governance. Available online: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/site/en/com/2001/com2001_0428en01 (accessed on 21 March 2018).

- European Commission. 2009. Analysis and Statistics of the 2004–2009 Legislature. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/codecision/statistics/docs/report_statistics_public_draft.pdf (accessed on 18 March 2018).

- European Commission. 2012. “Regulatory Fitness”: Making the Best of EU Law in Difficult Times, Press Release, IP/12/1349, Brussels, 12/12/2012. Available online: http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-12-1349_en.htm (accessed on 19 March 2018).

- European Commission. 2017. Public Opinion in the European Union, First Results. Standard Eurobarometer 88—Autumn 2017. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/commfrontoffice/publicopinion/pdf (accessed on 18 March 2018).

- European Parliament. 2004. Activity Report of the Delegations to the Conciliation Committee on 1 May 1999 to 30 April 2004 (5th Parliamentary Term), Brussels. Available online: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/code/information/activity_reports/activity_report_1999_2004_en.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2018).

- European Parliament. 2007a. Conciliere și codecizie. In Ghid Privind Activitatea de Colegiferare a Parlamentului, [Conciliation and Codecision. Guideline Regarding EP Co-Regulative Activity]. Brussels: European Parliament. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament. 2007b. Conciliations and Codecision. Activity Report of the Delegations to the Conciliation Committee, July 2004 to December 2006 (6th Parliamentary Term. First Half-Term), Brussels. Available online: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/code/information/activity_reports/activity_report_2004_2006_en.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2018).

- European Parliament. 2009a. Activity Report of the Committee on the Environment, Public Health and Food Safety. 2004–2009. Brussels. Available online: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/meetdocs/2009_2014/documents/envi/dv/200/200907/20090716_envi_act_rep_en.pdf (accessed on 16 May 2019).

- European Parliament. 2009b. Activity Report of the Delegations to the Conciliation Committee, 1 May 2004 to 13 July 2009 (6th Parliamentary term), Brussels. Available online: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/code/information/activity_reports/activity_report_2004_2009_en.pdf (accessed on 16 May 2019).

- European Parliament. 2012. Raportul de activitate 14 iulie 2009—31 decembrie 2011 (A șaptea legislatură) al delegațiilor la comitetul de conciliere Parlamentul European, Brussels. Available online: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/code/information/activity_reports/activity_report_2009_2011_ro.pdf (accessed on 13 May 2018).

- European Parliament. 2013. Challenges of Multi-Tier Governance in the European Union. Effectiveness, Efficiency and Legitimacy, Directorate General for Internal Policies. Available online: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/activities/committees/studies.do?language=EN (accessed on 16 September 2018).

- European Parliament. 2014a. Conciliations and Codecision, Statistics on Concluded Codecision Procedures. Available online: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/code/about/statistics_en.htm (accessed on 18 September 2018).

- European Parliament. 2014b. OEIL. Available online: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/oeil/home/home.do (accessed on 18 September 2018).

- European Parliament. 2014c. Activity Report on Codecision and Conciliation 14 July 2009–30 June 2014 (7th Parliamentary Term), Brussels. Available online: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/code/information/activity_reports/activity_report_2009_2014_en.pdf (accessed on 18 September 2018).

- European Parliament. 2017. Activity Report on the Ordinary Legislative Procedure 4 July 2014–31 December 2016 (8th Parliamentary Term), Brussels. Available online: http://www.epgencms.europarl.europa.eu/cmsdata/upload/7c368f56-983b-431e-a9fa-643d609f86b8/Activity-report-ordinary-legislative-procedure-2014-2016-en.pdf (accessed on 16 May 2019).

- European Parliament. 2019a. European Elections. Available online: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/at-your-service/en/be-heard/elections (accessed on 15 July 2019).

- European Parliament. 2019b. European Elections Results, 3.07.2019. Available online: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/press-room/elections-press-kit/0/european-elections-results (accessed on 15 July 2019).

- European Parliament. 2019c. Statistics. Legislative Observatory. Available online: https://oeil.secure.europarl.europa.eu/oeil/home/home.do (accessed on 15 July 2019).

- European Parliament. n.d. The New Parliament and the New Commission. Members, Bodies and Activities. Available online: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/portal/en (accessed on 16 March 2018).

- European Union. n.d. The Codecision Procedure. Glossary. Available online: http://europa.eu/legislation_summaries/glossary/codecision_procedure_en.htm (accessed on 16 March 2018).

- Infoeuropa. 2007. Procedura de Co-Decizie în Uniunea Europeană, Glosar de Termeni. Teme Europene, No. 34/2007. Bucureşti: Ed. Economică. [Google Scholar]

- Kurpas, Sebastian, Caroline Grøn, and Piotr Kaczyński. 2008. The European Commission after Enlargement: Does More Add up to Less. Special Report CEPS. Brussels: UNSPECIFIED. [Google Scholar]

- Lamassoure, A. 2008. L’évolution du Rôle du Parlement Européen et la Question de sa Représentativité. Entretien avec Hervé Bribosia, CVCE. Available online: http://www.ena.lu/interview_alain_lamassoure_evolution_role_parlement_europeen_question_representativite_paris_septembre_2008-2-30740 (accessed on 10 January 2018).

- Matei, Ani, and Lucica Matei. 2010. European Administration. Normative Fundaments and Systemic Models. Available online: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1651782 (accessed on 10 January 2018).

- Matei, Ani, and Tatiana-Camelia Dogaru. 2012. The Rationality of Public Policies. An Analytical Approach. Norderstedt: GRIN Verlag GmbH. [Google Scholar]

- Matei, Lucica. 2006. Management Public. Bucureşti: Ed. Economică. [Google Scholar]

- Matei, Lucica. 2009. Decizia în uniunea Europeană. Caiete Jean Monnet. Bucureşti: Ed Economică. [Google Scholar]

- Neyer, Jürgen. 2010. Explaining the unexpected: Efficiency and effectiveness in European decision-making. Journal of European Public Policy 11: 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, Heiner, and Thomas Konig. 2000. Institutional reform and decision-making efficiency in the European union. American Journal of Political Science 44: 653–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shackleton, Michael, and Tapio Raunio. 2003. Codecision since Amsterdam: A laboratory for institutional innovation and change. Journal of European Public Policy 10: 171–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleseat. n.d. Facts and Figures. Available online: http://www.singleseat.eu/10.html (accessed on 14 July 2019).

- Torres, Francisco. 2003. How efficient is joint decision-making in the EU? Environmental policies and the co-decision procedure. Intereconomics 38: 312–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of Procedures | The Fifth Legislature (1999–2004) Measured in 2014 and 2019 | The Sixth Legislature (2004–2009)Measured in 2014 and 2019 | The Seventh Legislature (2009–2014) | The Eighth Legislature (2014–2019) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Completed procedures | 495 | 495 | 527 | 527 | 558 | 383 |

| Lapsed or withdrawn procedures | 68 | 71 | 26 | 56 | 67 | 7 |

| On-going procedures | 3 | 0 | 31 | 1 | 28 | 140 |

| Rejected procedures | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | - | |

| Total procedures | 569 | 569 | 586 | 586 | 653 | 530 |

| Agreement on | 1999–2004 Legislature | 2004–2009 Legislature | The Shortest and Longest Procedure (2004–2009) |

|---|---|---|---|

| First Reading | 13.8 | 15.2 | 1.8/47.9 |

| Second reading | 25.1 | 31.3 | 11.9/108.1 |

| Conciliation | 31.9 | 43.7 | 28.8/159.4 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Matei, A.; Ciora, C.; Dumitru, A.S.; Ceche, R. Efficiency and Effectiveness of the European Parliament under the Ordinary Legislative Procedure. Adm. Sci. 2019, 9, 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci9030070

Matei A, Ciora C, Dumitru AS, Ceche R. Efficiency and Effectiveness of the European Parliament under the Ordinary Legislative Procedure. Administrative Sciences. 2019; 9(3):70. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci9030070

Chicago/Turabian StyleMatei, Ani, Cristina Ciora, Adrian Stelian Dumitru, and Reli Ceche. 2019. "Efficiency and Effectiveness of the European Parliament under the Ordinary Legislative Procedure" Administrative Sciences 9, no. 3: 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci9030070

APA StyleMatei, A., Ciora, C., Dumitru, A. S., & Ceche, R. (2019). Efficiency and Effectiveness of the European Parliament under the Ordinary Legislative Procedure. Administrative Sciences, 9(3), 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci9030070