1. Introduction

From the establishment of the first universities in the 11th century in Europe until the 20th century, the mission of educating society and developing fundamental knowledge has been praised (often stressing the principles of the Humboldtian university), and the state has assumed the function of financing higher education (HE). However, since the 1980s, universities have found themselves expected to ensure that their activities cohere with the developing practical needs of society, and that they can provide services that meet market conditions, that is, that can compete for customers and generate revenue for their services (through tuition fees, contracted work, etc.). This illustrates the apparent shift of HE from a public good to a private good, or tradeable service, during the last two decades.

The concept of public goods is central to the economic analysis of the government’s role in resource allocation. Public goods are defined by two characteristics: (1) Non-excludability—it is impossible to exclude non-payers from consuming the good, and (2) non-rivalry in consumption—additional people consuming the good does not diminish the benefit to others.

However, considering the latter definition, it is evident that, in most countries, HE is no longer entirely a public good. People who do not pay for education services may be excluded; there are many countries where individuals, and not the state, cover study costs; and there are more and more paid education services. Nevertheless, the shift from public good to private good might raise the conditions of the public interest violation; however, little is known about such occurrences in practice.

The vast changes in the international HE context, especially increased competition for students and government funds, have led to the emergence of the entrepreneurial university phenomena. The literature (

Clark 1998,

2001;

Gallagher and Garrett 2012) often argues that, in order to succeed, HEIs need to develop a business model. These new models often require significant changes to university culture and procedures. Bearing in mind that universities have traditionally been resistant to change, university managers are challenged with finding ways to maintain their unaltered mission and stay true to their academic values while, at the same time, changing their operating models.

The entrepreneurial university is a self-steering, self-reliant university, and the literature has stressed that the entrepreneurial university is forward-looking and pursues opportunities beyond its available means (

Clark 1998).

When HE entrepreneurial activities are discussed, the education system is interpreted as a market. The literature argues that the entrepreneurial behaviour of a university in the local market leads to entrepreneurial activities in foreign markets. Quite often, the limitations of the local market, including those established earlier, do not allow for easy repositioning. It is far less complicated to do so in a foreign market.

This can be proved by the activities of UK universities abroad that have different markets and different images in foreign markets. A branch campus is one way of assuring a constant presence in a foreign market.

Middlesex University, for instance, has reinvented its identity through proactive internationalisation and bringing this new international identity ‘home’. In this way, it thus reinvents its image in a local market.

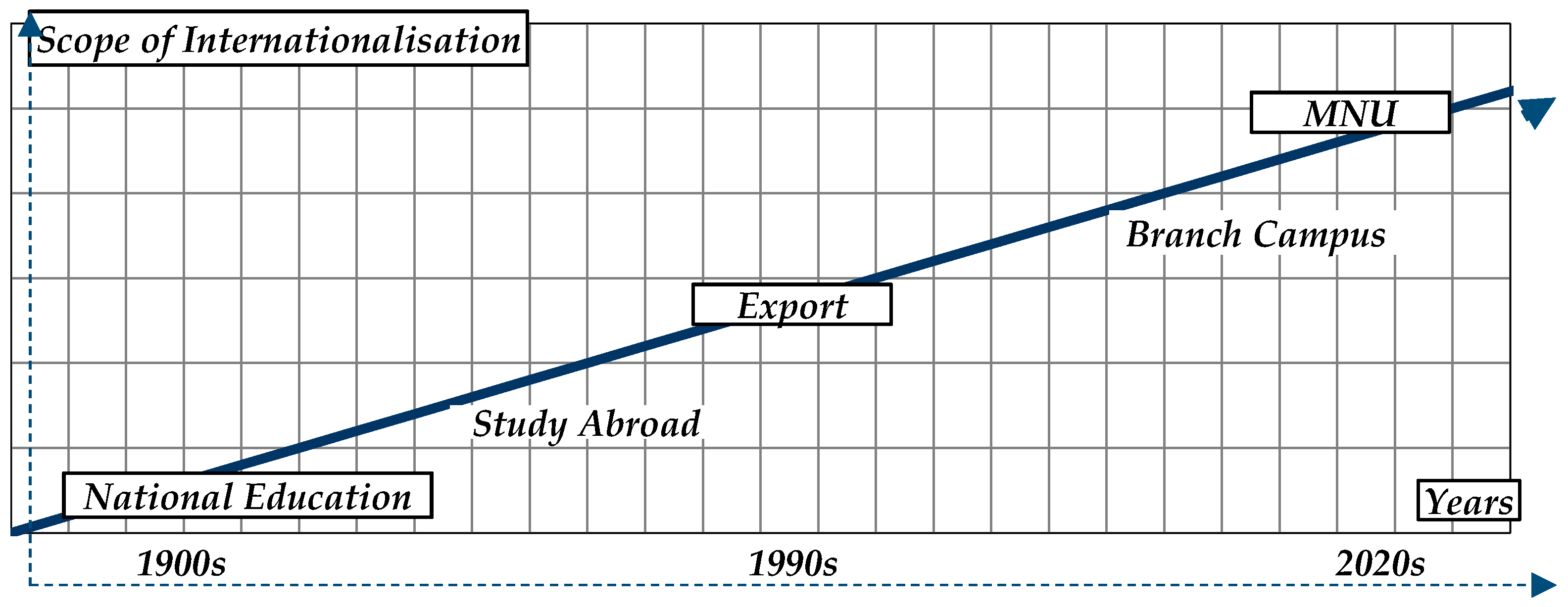

The shift from national to international and multinational status has taken place in the HE arena globally over the past century (see

Figure 1). The export of education services had already started by the time the second generation of cross-border education took place (

Knight 2003). The mobility of students grew into the mobility of programmes and, finally, the export of education evolved into a radical form: Branch campuses (first established in 1998 in the UK, and in 1997 in Russia). Finally, further development has been orientated towards the rise of multinational universities (MNUs), which multiply their institutional mobility experience and have multiple IBCs (e.g., Limkokwing University, Stenden University).

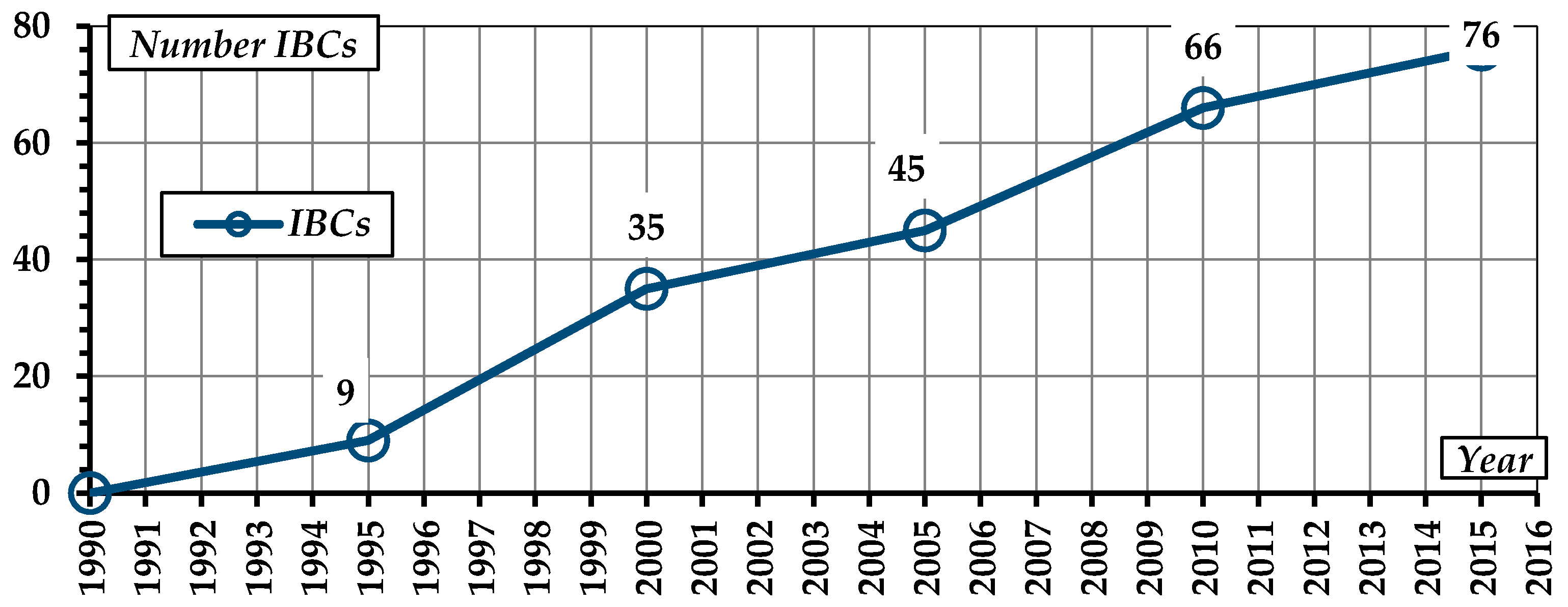

According to Garrett and co-authors (

Garrett et al. 2016), prior to 1990, there were 22 IBCs, and by 2015, the number had grown to 256. According to the Cross-Border Education Research Team (

C-BERT 2017), in 2017, there were 247 branch campuses operating globally, 22 new IBCs planned to open, and 42 were known to have closed (see

Figure 2). Different listing attempts of IBCs do not always match, and this may relate to changes and differences in the definition of what constitutes an IBC (

Lawton and Katsomitros 2012;

Kinser and Lane 2012;

Garrett et al. 2016).

For the purpose of this report, the authors use the definition established by Garrett and his research group (

Garrett et al. 2016): ‘An entity that is owned, at least in part, by a foreign HE provider; operated in the name of the foreign education provider; and provides an entire academic programme, substantially on site, leading to a degree awarded by the foreign education provider.’

The IBC has been further analysed as a structural unit to explore and penetrate foreign markets with education products and services. Such a campus is a type of business unit that is more flexible and independent (less context-embedded) in comparison to the parent institution and can generate revenue from new markets, similar to international subsidiaries of business companies.

2. Literature Review

In terms of business model transfer to HE and the theoretical framework to enhance business-like behaviour, the main fields in which business and HEI behaviour most closely resemble each other is the internationalisation of their activities, the research priority given to foreign market entry modes, their selection, and their realisation for service export.

Foreign market entry mode is an institutional arrangement that allows the entry of a company’s products and services, technology, knowledge, human capital, management, or other resources into a foreign country (

Root 1994). The choice of foreign market entry mode is an important decision that the management of a university must plan and estimate well.

The entry into a foreign market is likely to be complicated by several factors related to the host market, such as host government policy, culture, physical distance, etc.; therefore, market selection is important. The factors that determine the entry mode choice include the varying levels of control, resource commitment, and risk (

Anderson and Gatignon 1986;

Blomstermo et al. 2006;

Madichie and Kolo 2013;

Goi 2016).

There are various modes for service firms’ foreign market entry: Exporting, licensing, joint ventures, and wholly owned operations. One of the most discussed theories of the Nordic school–Uppsala’s internationalisation approach suggests an incremental approach. According to the traditional Uppsala model, business companies expand their operations in a foreign market gradually, choosing less complicated forms of export and beginning with entry into foreign markets that are closer to the domestic market in terms of psychic distance and similar institutional conditions before moving on to host countries differ more (

Johanson and Vahlne 1977,

2009). In this study, this theory is tested in the HE context and determines whether universities move incrementally from the recruitment of students to institutional mobility and whether they start with countries with a smaller psychic distance.

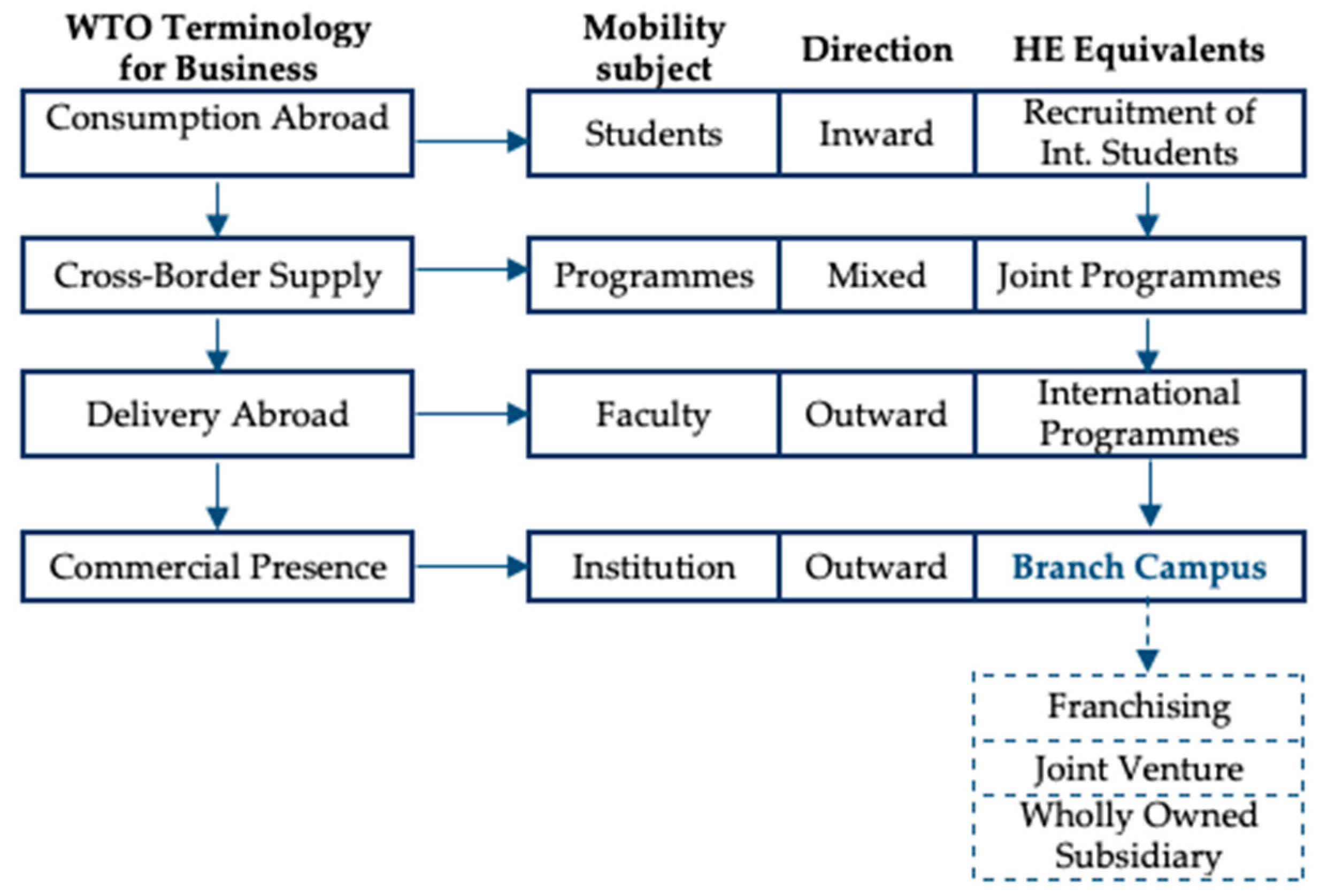

Four modes of internationalisation are listed in

Figure 3, according to the WTO typology: Consumption abroad, cross-border supply, delivery abroad, and commercial presence. The activities are listed in descending order according to the growing intensity and complexity of internationalisation. Terms that are equivalent to each other are listed horizontally on the same line.

‘Consumption abroad’ in business refers to a situation in which consumers from one country use the service supplied by another country, in other words, when the recipient of the service temporarily moves to the provider’s location. In HE, this mode corresponds to student mobility and the international movement of researchers (

Czinkota and Ronkainen 2009;

Ennew 2012). One should note that, from the perspective of a particular HEI, an example of inward mobility is when international students or researchers (consumers) come to the providing university for temporary access to particular service (studies, research).

The second mode of internationalisation in the business context, cross-border supply, corresponds to programme mobility in HE (joint programmes, distance and online learning). Both in cross-border supply and programme mobility, service is created in a country of origin, while the delivery is transferred abroad. HE research (

Naidoo 2009) has shown that Australia is the most active exporter of programme mobility. The overall intensity of Australia’s activity was 42.4 programmes per institution, compared with 12.7 programmes for UK-based institutions. Increasingly, delivery abroad and cross-border supply are combined to deliver courses by fly-in faculty combined with online resources (

Ennew 2012).

Another strategic mode of the internationalisation of service industries according to the WTO is delivery abroad, or the presence of natural persons, when the service is both created and delivered in another country. This mode is also defined as the temporary movement of the service provider to the customers’ location. In HE, this is practiced with faculty and academic mobility (

Czinkota and Ronkainen 2009;

Ennew 2012) as well as research visits, fellowships, and expert services (

Ennew 2012).

The last mode the WTO has indicated is commercial presence, when the providers of a service establish their commercial presence through subsidiaries and outlets internationally (

Czinkota and Ronkainen 2009;

Ennew 2012). In HE, this approach refers to institutional mobility. Along with franchising, there are different forms of equity-based participation; in HE, this mode takes the legal forms of joint ventures and wholly owned subsidiaries (that is, IBCs).

This paper analyses offshoring education services in the form of a branch campus as a business model transfer into HE practices.

3. Research Question

The issue of developing and managing an IBC has been addressed by other researchers (

Becker 2009;

Healey 2015;

Girdzijauskaite and Radzeviciene 2014;

Knight 2005;

Lane 2011;

Lawton and Katsomitros 2012); however, the literature review shows a lack of knowledge that is necessary for the strategic and systematic approach to IBCs as the most radical form of foreign market entry. Hence, the purpose of this paper is to investigate ways of creating and managing IBCs and elaborate the recommendations for universities when establishing a branch campus as an entry mode to foreign education market.

A closer look at the IBCs monitored by the Observatory on Borderless Higher Education (OBHE) and Cross-Border Education Research Team (C-BERT) reveals that finding a comprehensive definition of an IBC is difficult due to the relative newness of the IBC phenomenon, in addition to the uniqueness and variety of cases (

Healey 2014;

Lane and Kinser 2012). The existing definitions of IBCs different researchers and organisations have provided are listed in the

Table 1.

Nigel Martin

Healey (

2014) has claimed that, instead of constantly trying to answer what an IBC is, we should look into the question of when an IBC is. He has discussed the metaphor of a child and parent relationship in his work, ‘When is an international branch campus?’ Branch campuses start as dependent ‘infants’, strongly reliant on the mother campus (university). Later, they become ‘teenagers’, chafing at parental control and seeking autonomy. As ‘young adults’, they begin to develop their own personalities and the bond with the mother campus weakens.

In order to investigate the aspects of creating and managing IBCs and to elaborate the recommendations for universities on establishing a branch campus as an entry mode to the foreign education market, an international survey has been executed with global branch campus managers. The research question addresses how to exploit IBCs as a foreign market entry mode for the universities.

4. Methodology

In order to conduct this qualitative survey, seven cases were analysed to investigate the existing experiences. First, out of 233 IBCs established, 50 were chosen to survey. The cases were chosen to represent a wide variety in terms of size, age, form, expansion direction, etc. A semi-structured questionnaire combining multiple choice

1 and open questions were sent to the respondents. Finally, seven cases were selected as applicable and are presented in this thesis in the form of a case study. There was extended communication for information specification with experts before the final analysis. Seven cases of the universities who operate international IBCs have been analysed in order to identify the peculiarities of this foreign market entry mode. The respondents of the IBC case study are the top managers of their respective units with over 10 years of experience:

- -

Executive Director at IBC established in Australia by the HEI in USA;

- -

Deputy Managing Director at IBC established in Singapore by the HEI in USA;

- -

Director at IBC established in Qatar by the HEI in UK;

- -

Dean at IBC established in Russia by the HEI in Sweden;

- -

Head at IBC established in Finland by the HEI in Estonia;

- -

Director of International Relations at HEI in Australia;

- -

Marketing Manager for Europe and America at HEI in Malaysia.

In order to protect confidential information, the names of the institutions are not disclosed and have been codified as cases A, B, C, D, E, F, G, as agreed with the experts (

Dixon et al. 1995;

Unal 1997). Due to respondent profiles and the relatively rare occurrence of IBC in practice (0.8% of HEIs globally have IBCs), every case is of significant value to the research. Cases were selected to have diverse global coverage of different existing practices.

The empirical research aimed at analysing different cases of IBCs. Four cases out of five are of mature universities in order to gain insight into the renowned and longstanding ‘best practices’, and one latecomer was selected in order to check the applicability of the IBC mode by latecomer institutions. The cases differed in terms of IBC timing: 1997—absolute beginner in the field (claimed to be the among the first mover institutions worldwide), 2006—established in a period of time during the rise of the phenomenon, 2011—very recent practise. In addition, cases A, B, and C were chosen as examples of traditional host countries (Singapore, Qatar) and predominant providing countries (UK, USA), as well as the examples of untraditional hosts (Russia, Finland) and providing countries (Sweden, Estonia).

The sequence of incremental steps of foreign market entry has been analysed along with the rationales behind and paths to IBC establishment. The hypothesis concerning the possible coherence of the IBC establishment practices with the Uppsala internationalisation model used in international business practices has also been verified.

The expert survey consisted of 23 questions (see

Supplementary Materials), 14 of which were dedicated to obtaining statistical and strategic data about the IBC (students and staff numbers, market entry model, expansion direction, etc.), and nine questions were dedicated to analysing the expert opinions on the strategic rationales of establishing and managing an IBC: Push and pull factors, competitive advantage, government support, sequence of internationalisation steps, product adaptation, challenges, consumer behaviour, risk management, and further market exploration. These are analysed in more detail in the

Findings chapter.

5. Findings

After executing the global expert survey, the key data has been gathered on seven cases, and the key data describing the cases is provided in

Table 2.

The IBCs analysed were founded between 1997 and 2011. One was initiated by the host country government, two were initiated by the founding HEI itself, and four were initiated by other bodies in the host country. The IBCs were founded by HEIs from the USA, the UK, Sweden, Malaysia, Australia, and Estonia in the following host countries: Australia, Singapore, Qatar, Russia, Finland, Vietnam, and Cambodia. The expansion direction moved from developing to developed countries in four cases, and from more saturated to less saturated markets in four cases. The founding HEI profiles varied from latecomer to mature and from private to public. Four of the cases chosen already have multiple IBCs operating in foreign markets.

Various market entry models were chosen for the IBCs in the following cases: Fully owned subsidiaries, strategic alliances, and a joint venture with a partner or agent in a host country. Most partners proved to be HEIs; case C was the exception with a non-HEI partner in a strategic alliance. The initial number of students varied from 20 to 200, and the initial staff number varied from four to 30. The largest growth has been seen in case F, a branch campus founded by an Australian HEI in Vietnam. The student number has grown from 36 in 2001 to 4929 in 2013. The fields of the IBCs include IT (information technology), public policy, international business management (IBM), hospitality management, and archaeology.

6. Discussion

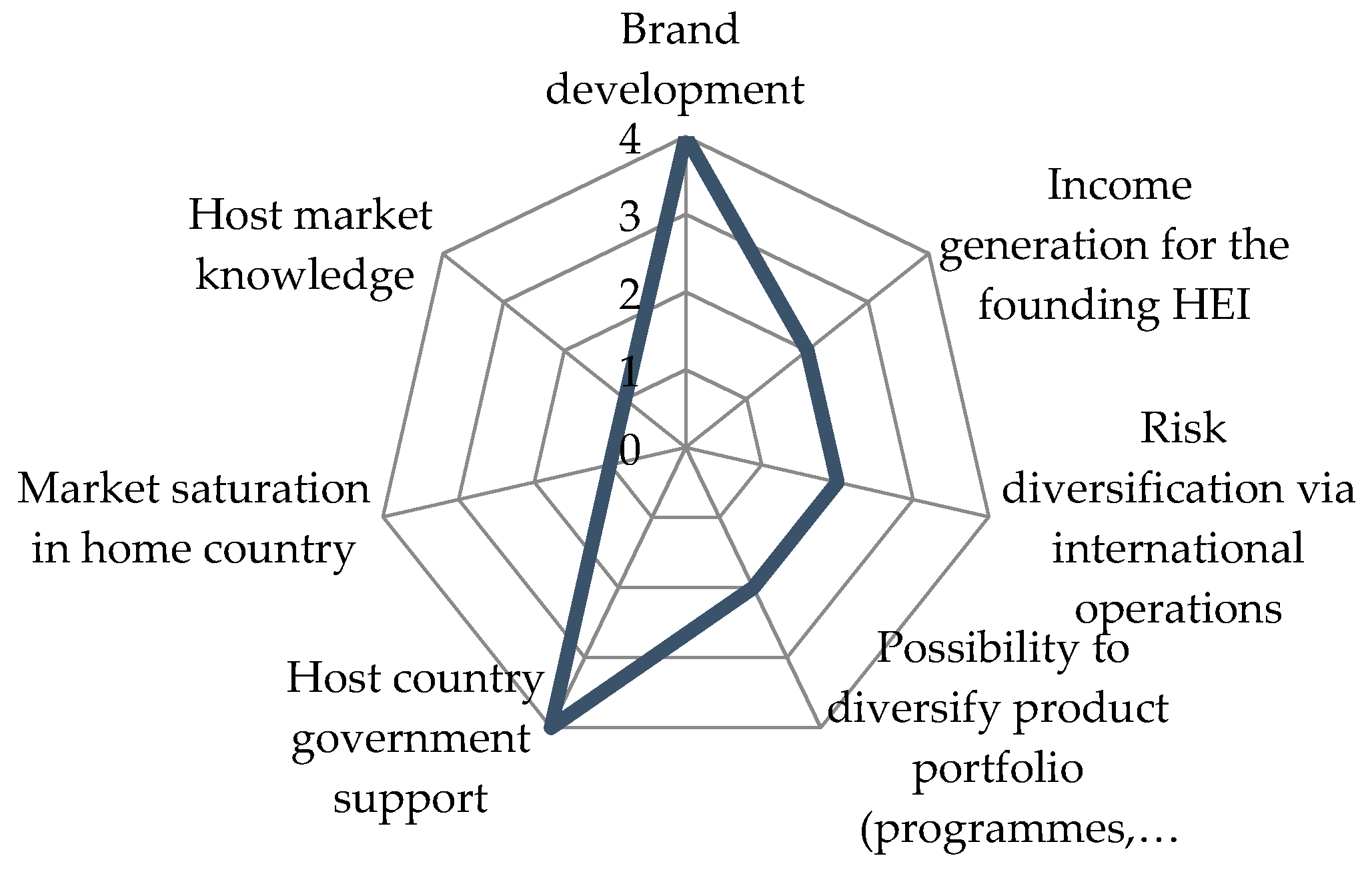

The respondents’ answers to the reasons of the founding university when establishing an IBC in a multiple-choice questionnaire illustrate the high importance of brand development and host country government support (four respondents found it relevant). It is interesting to note that host market knowledge and the market saturation in the home country are seen having low relevance in most cases (only one respondent found it relevant). This might mean that institutions have already gathered knowledge through other international activities in particular markets before establishing an IBC. Only two respondents marked income generation for the founding HEI, risk diversification via international operations, and the possibility of diversifying the product portfolio as important (see the

Figure 4). This suggests that the IBCs do not have a strong emphasis on the economic factor, and it supports the hypothesis that brand development might be even more important when establishing an IBC.

As a result of research, we can state that both the international reputation of the founding HEI and the reputation of the national education system are some of the most important factors that determine successful entry of IBC implementation. This is also supported by the global branch campus analysis, which shows that most IBCs are established by universities from countries with strong education brands (e.g., the USA, the UK, France).

Another factor the experts noted as a competitive edge is a unique product in a market (e.g., study programme, course, degree). One of the unique product examples experts provided was Western education in a Russian context, which is highly relevant for European latecomer HEIs (i.e., in CEE countries) who plan to offer degree education recognised in the EU for students of non-EU countries. Having adequate knowledge of NIC countries and a product, such as a degree that is recognised in the European labour market, creates a competitive edge for educational service export for universities of CEE countries.

The following are the factors that determine the IBC success indicated by case respondents. The results were obtained from an open question. Four experts (A, C, D, F) indicated that international reputation and the ranking of the university are the key factors that determine the IBC’s success. Expert D also added differentiation in the local market (i.e., Western education in a Russian context). This is quite strong data given that no options were suggested and more than half of the respondents nevertheless provided the same answers. Expert B elaborated on the success factors as follows: ‘Matching demand and supply, i.e., matching economic growth projections of the host country with the education offered by the providing university (“country emphasis on tourism development, although limited availability of programmes on hospitality management, and strong reputation of U.S.-based hotel college in hospitality management”)’. Expert E emphasised flexibility, being proactive, and agile behaviour: ‘Being a respectively small, privately owned university, we can adapt, decide, and implement decisions quickly; the offered study programmes have good balance of academic and practical (real business) part; the offered programme in branch was a module-study BA programme, which was unique in the host country’. Expert G thought that the reason their IBC succeeded was the fact that it was the first foreign university in the market and thus had product differentiation.

In five out of seven analysed cases, support was received from the host country government. In two cases (E and F), it was received both from home and host countries. As HE belongs to the government regulation area, given that it is a strategic sector for national development, in many countries, the host country’s protectionism might have a key impact (positive or negative) on this initiative and successful operations later.

According to the experts, the political environment is a key determinant when establishing an IBC in a foreign market. In fact, in most cases, government support was evaluated as a top reason to establish an IBC. An average evaluation of eight was assigned equally in both stages of establishing and operating an IBC. The importance of a host market’s economic growth is also high according to the experts and differs slightly at stages of IBC establishment (7.6) and operating (8) on a 1–10 scale.

When asked whether there was any activity in the host country before establishing an IBC, there were four negative (two latecomers, two mature) and three positive (all mature HEIs) answers. This illustrates that the stepwise gathering of knowledge to enter foreign markets (as supposed by the Uppsala internationalisation model) is not necessarily applied in IBC cases. Some institutions can skip the processes of gaining sequential market knowledge, which, in a way contradicts the classic assumptions of the Uppsala internationalisation model.

The average evaluation (on a 1–10 scale) of the extent to which consumer behaviour is similar in the home and host education market was 3.4. If the Uppsala theory application is to be verified, the answers of HEIs who have only one IBC are especially relevant in this case, since HEIs that own multiple IBCs are further along with internationalisation and are not entirely eligible for the beginning phase analysis. The analysis of expert views (A, B, F) shows that the Uppsala theory is not applied when choosing the market in HE. This is the difference of practice in business when markets with little psychic difference are the priority markets for internationalisation.

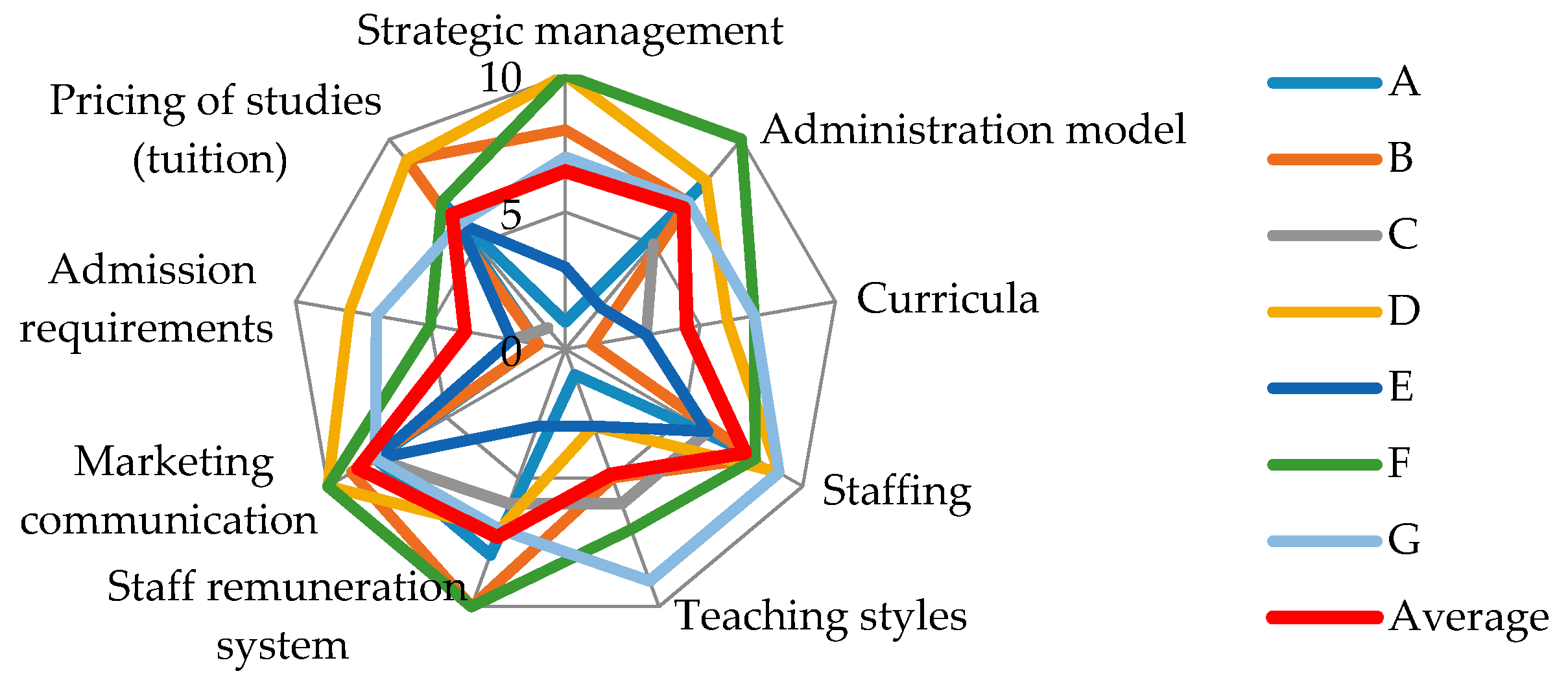

Out of nine factors evaluated, marketing communication requires the most extreme adaptation, followed by strategic management, the administration model, staffing and the staff remuneration system, and pricing of studies (see

Figure 5). As expected, teaching style is hardly an object for adaptation, nor are curricula and admission requirements. This is where institutions keep their uniqueness and quality assurance policy.

In most cases, the best practices are transferred to a low extent; only the E and G cases noted the ‘constant exchange of practices between home and host locations’. This seems to be an unexplored opportunity for institutions. The practices are more likely to be transferred further to other IBCs, rather than back home, for multinational universities with several IBCs (e.g., Limkokwing University, Stenden University).

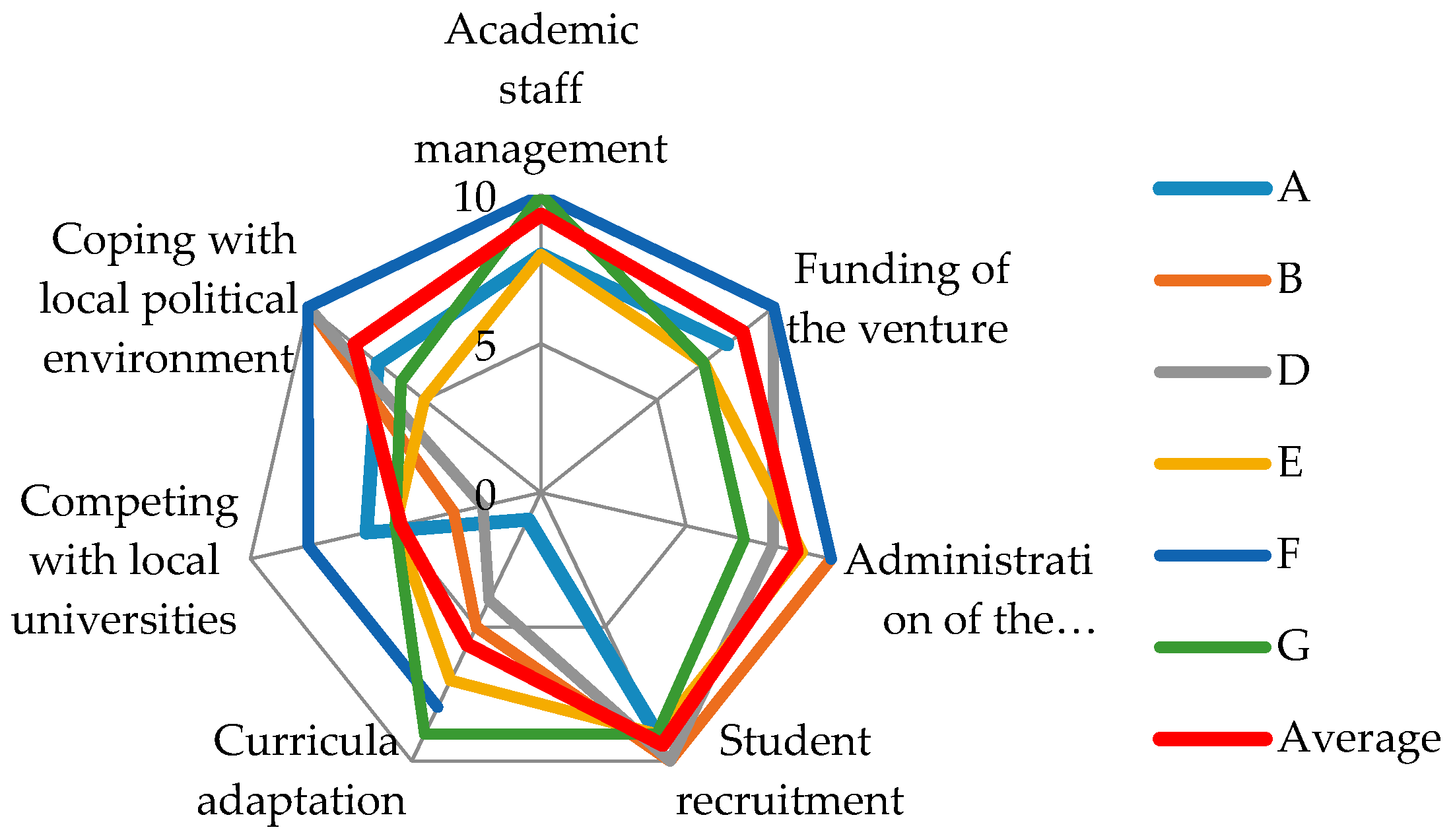

According to the representative experts, the largest challenges when running a branch campus are student recruitment, academic staff management, funding of the venture, and coping with the local political environment (see

Figure 6). Curricula adaptation is a lower challenge, since it is not an object for adaptation. However, it is interesting that experts do not think of competing with local players as a challenge, which contradicts the statement that student recruitment is one of the most significant challenges indicated.

The validity of the hypothesis, ‘An independent branch campus operated by a providing university is riskier than a joint venture’ was evaluated at a three on a 1–10 scale. This is a rather unexpected answer; due to theory analysis, the primary conclusions differ, but the variance of notions can be an unconsidered factor. Even though resources, especially financial ones, are at lower risk in a joint venture due to shared liabilities, a joint venture is a contracted activity terminated in time, which makes the venture inflexible and dependent on a partner. This limits quick reactions and independent risk management decisions such as reorganisation, location change, or a shut down.

When asked about the possibility of entering a new foreign market in the near future, a positive trend emerged in the cases results, as expected: Five out of seven stated that the multiplication of the same market entry could be explored in the future.

7. Conclusions

The analysis showed that an IBC is applicable as a foreign market entry mode by mature as well as latecomer institutions of HE. In the form of joint ventures, IBCs are treated as riskier modes than was initially assumed due to contractual agreements and high partner dependency. The study showed that, in order to exploit the IBC as a market entry mode in HE, the following aspects must be taken into account.

The most important factors when establishing an international IBC proved to be brand development and government support. A favourable political environment and economic growth in the host country are important both when establishing and operating an IBC. In addition, international reputation and having a unique product serve as a competitive advantage when establishing IBC.

This also suggests an interesting notion: While business theory and practice are applicable in IBC development, there is a significant difference in the motivating factors. Interestingly, IBC as a market entry mode is not aimed at increasing the income of HEIs; it is more for strengthening the brand and positioning it in certain markets. This is what differentiates HEIs form business firms and IBCs from foreign direct investment. However, income generation is still an important part of sustaining the business model of an IBC and keeping it sustainable.

According to the representative experts, the largest challenges when running a branch campus are student recruitment, academic staff management, funding of the venture, and coping with the local political environment. Foreign rivals’ existence in a foreign market is not determining when establishing an international IBC; local competitors seem to be ignored or treated as less influential when sharing the market.

Marketing communication may be the most extreme adaptation when offshoring educational services, followed by strategic management, the administration model, staffing and the staff remuneration system, and the pricing of studies.

The hypothesis of the possible coherence of the IBC establishment practices with the Uppsala internationalisation model used in international business practices has been verified in this research. While there were many promising signs of coherence, in the end, the research results do not provide an unambiguous confirmation of the hypothesis. Apparently, some institutions can skip the process of gaining sequential market knowledge, and the Uppsala model seems to be applicable for latecomer HEIs only to a certain extent.

However, we noticed that the role of a local partnership (government, agents) is highly recognised; we believe that, potentially, there is a possibility of higher coherence between the IBC establishment practices and the revisited Uppsala internationalisation model, which is based on relationships and market commitment. This could be a continuation of this research, perhaps followed by the testing of OLI theory and the linkage, leverage, learning (LLL) algorithm elaborated by J. A. Mathews in HE internationalisation (

Mathews 2002,

2006). It would be interesting to verify the sustainable establishment in the market.