1. Introduction

Relationships between consumers and brands encompass several dimensions that have attracted the attention of those in marketing research. Terms such as emotional attachment (

Thomson et al. 2005), brand love (

Carroll and Ahuvia 2006;

Batra et al. 2012), or engagement (

Brodie et al. 2011;

Hollebeek et al. 2014;

Vivek et al. 2014) refer, a priori, to different stages of the relationship developed between brands and individuals. They represent close notions, sharing certain features, and describe both the degree of connection and the intensity of the consumer–brand relationship. Although they share some traits, they might be different constructs in terms of their meaning, their dimensionality, items employed to define them, and the link between them.

The purpose of this paper is to shed light into these relationships, delimiting their definitions and measurement. In order to do so, the main objective of this study is to establish the links—and boundaries—between these three related concepts, by examining their relationships. A second objective, derived from the first one, is to provide the readers with a better measurement of the constructs “underlying” attachment, love, and engagement.

Therefore, the current study posed the following research questions (RQ):

- (1)

Where is the conceptual border between the three notions that allude to the consumer affection toward brands? That is,

- (2)

Are these concepts properly measured? (RQ3)

- (3)

Are they multidimensional or unidimensional? (RQ4)

The contribution of this study is threefold. First, it theoretically elucidates the understanding of consumer–brand relationships. Second, it generates a model that comprises the entire process of moving from attachment to engagement. This model is used to test a framework to provide further evidence of the (dis)similarity of the constructs. Third, the findings of this paper could also aid managers to use efficient communication strategies, not only based on the emotions, but also supported by values that produce a viral activation among consumers. Then, attachment supposes a real bond to the brand that transforms loyal consumers into brand promoters.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. First, a review of the relevant literature is provided. By defining briefly the three terms and establishing the controversial arguments and evidence in the literature, the reader will understand if these dimensions are the same or are different. Next, the studies that developed empirical analyses are examined, focusing especially on measurement. Then, an empirical model with data from a survey of 320 consumers in Spain with structural equation modeling (SEM) is tested. This improved measurement of the links between the constructs is needed to define managerial implications. The last section is devoted to the discussion, limitations, and possible directions for future research.

2. Background: The Conceptual Border between Attachment, Love, and Engagement

Three related notions were identified in the literature survey: emotional attachment, brand love, and customer engagement. Criticism regarding recent consumer–brand relationship concepts in the marketing literature, especially in the case of brand love (

Rossiter 2012;

Moussa 2015), highlights the importance of establishing the boundaries between attachment, love, and engagement. This conceptual delimitation is relevant, since the different terms may constitute either antecedents or consequences of different conceptual models that have been researched separately except for four recent studies (

Bergkvist and Bech-Larsen 2010;

Wallace et al. 2014;

Sarkar and Sreejesh 2014;

Vernuccio et al. 2015).

Most likely, the problem that creates the relative terminological confusion is that the concepts originate from different pre-existing theories in diverse fields. For instance, the conceptual development of brand love arose from social psychology (

Batra et al. 2012). In contrast, consumer engagement comes from the expanded domain of relationship marketing and the service-dominant logic perspective (

Brodie et al. 2011;

Hollebeek et al. 2014). Hence, the research tradition that shapes their theoretical frameworks and main definitions has not converged.

2.1. Definitions

Thomson et al. (

2005) provided the seminal empirical work on emotional attachment to brands (

Grisaffe and Nguyen 2011). According to the first authors, emotional attachment is an “emotion-laden target-specific bond between a person and a specific object” (p. 78). Attachments vary in strength, and stronger attachments are associated with stronger feelings of connection, affection, and passion (

Thomson et al. 2005).

Brand love represents the intimate experience of very positive emotion toward a particular brand. Nevertheless, there are two main notions for brand love in the literature. On the one hand,

Carroll and Ahuvia (

2006, p. 81) define it as “the degree of passionate emotional attachment a satisfied consumer has for a particular trade name”. On the second hand,

Batra et al. (

2012, p. 2) provide a more complete definition: “a higher-order construct including multiple cognitions, emotions, and behaviors, which consumers organize into a mental prototype”. The first definition is based on the idea that brand love is platonic in nature, and typically focuses on aspirational brands that represent a lifestyle. The second suggests that brand love must be based not only on passion, but also on a long-term relationship (

Batra et al. 2012;

Albert and Merunka 2013). Thus, it refers to an ongoing relationship over an extended period of time (

Gómez-Suárez et al. 2016). These two different conceptualizations have led to diverse conceptual and empirical models.

The third concept, customer engagement, is also considered in the literature as an ongoing relationship between a brand and a customer. According to

Romero (

2017), marketing researchers study customer engagement from two different perspectives: a psychological perspective, encompassing cognitive, emotional, and behavioral elements (

Brodie et al. 2011); and from a behavioral point of view, focusing on customer engagement behavioral manifestation such as word-of-mouth or co-creation. The lack of consensus pertaining to the definition of focal engagement-based concepts (

Hollebeek 2013) provides different definitions. For instance, focusing on the psychological perspective,

Brodie et al. (

2011, p. 3) define customer engagement as “a multidimensional concept comprising cognitive, emotional, and/or behavioral dimensions, [which] plays a central role in the process of relational exchange”. By contrast,

Vivek et al. (

2014, p. 401) state that it is “the level of the customer’s (or potential customer’s) interactions and connections with the brand or firm’s offerings or activities” (

Vivek et al. 2014, p. 401).

2.2. Boundaries between the Concepts: Are These Dimensions the Same or Are They Different?

For

Moussa (

2015), the concepts of brand love and brand attachment are not only composed of the same constituent elements, but are the same concept, being both “the two facets of the same single penny” (p. 79). According to this author, the two terms are distinctly delimited from a non-stop race between academics who have transferred concepts from interpersonal relationship theories into the branding literature as a consequence of the “publish or perish” mechanism, so that hardly a year goes by without some reinventions or retouching of the proposed conceptualizations for both.

Unlike Moussa, some researchers have observed some differences between brand love and attachment.

Hwang and Kandampully (

2012, p. 101) recognized that both are conceptually similar, and distinguished the two constructs based on intensity: “brand love necessitates the intensity of emotional responses towards an object, while emotional attachment does not necessarily require such intensity”.

Bergkvist and Bech-Larsen (

2010, p. 504) also considered brand love as “a facet or dimension of broader constructs such as brand relationship quality or emotional attachment”, with love being “generally regarded as quantitatively different from liking, that is, love is not extreme liking but rather a construct that is different from, but related to, liking” (p. 506).

By contrast, the differences between attachment and engagement are more evident.

Vivek (

2009, p. 32) claimed that “attachment is an affective construct strongly associated with ownership or possession of objects or products, and so is different from customer engagement. However, attachment could lead to engagement in several situations”.

Regarding the brand love and engagement relationship, there has been a fragmented interpretation depending on the research context in which they have been supported. This issue especially arises when analyzing some antecedents of both concepts. According to

Gómez-Suárez et al. (

2016), different labels refer to the same concepts. For instance, the concepts of self-expression or self-congruity—derived from branding theories—have nearly the same meaning as identity, derived from identification theory.

2.3. Measurement: An Overview of Past Empirical Studies

In order to understand the nature of these three concepts, analyses of past studies were carried out by examining 46 empirical studies. These studies, classified by countries, methods, sample, dimensions, and main constructs, are offered in the

Appendix A (

Table A1,

Table A2,

Table A3 and

Table A4).

In general, the limitations of the previous studies were due to the method by which the data were obtained. The collection method in most studies was a convenience sample, often including students (18 studies). In some cases, the sample size was very small or had biases regarding age or sex. Mainly, the studies were carried out in a single country with the United States (14 studies) being the most frequently analyzed. If the research was qualitative, the authors recognized the lack of validity without no subsequent quantitative endorsement. If it was an experiment, they required that, in later works, the brand, product, or service not be fictitious. In the case of developing several methods, as in a large part of the studies, the online selection of the sample produced a bias by sex or a number of classification variables.

Regarding dimensionality, although most of the studies that analyzed a single construct proposed a single dimension, the most recent empirical models were multidimensional. This was the case of the attachment models proposed by

Fedorikhin et al. (

2008),

Grisaffe and Nguyen (

2011), and

Jimenez and Voss (

2014). The engagement model was proposed by

Javornik and Mandelli (

2012) and the brand love models were proposed by

Carroll and Ahuvia (

2006),

Hwang and Kandampully (

2012),

Rageh and Spinelli (

2012),

Fetscherin (

2014),

Huber et al. (

2015),

Dalman et al. (

2017),

Delgado-Ballester et al. (

2017), and

Algharabat (

2017). However, the five papers that combined love and engagement (

Bergkvist and Bech-Larsen 2010;

Wallace et al. 2014;

Sarkar and Sreejesh 2014;

Vernuccio et al. 2015;

Loureiro et al. 2017) treated the concepts as unidimensional constructs.

3. Conceptual Proposal

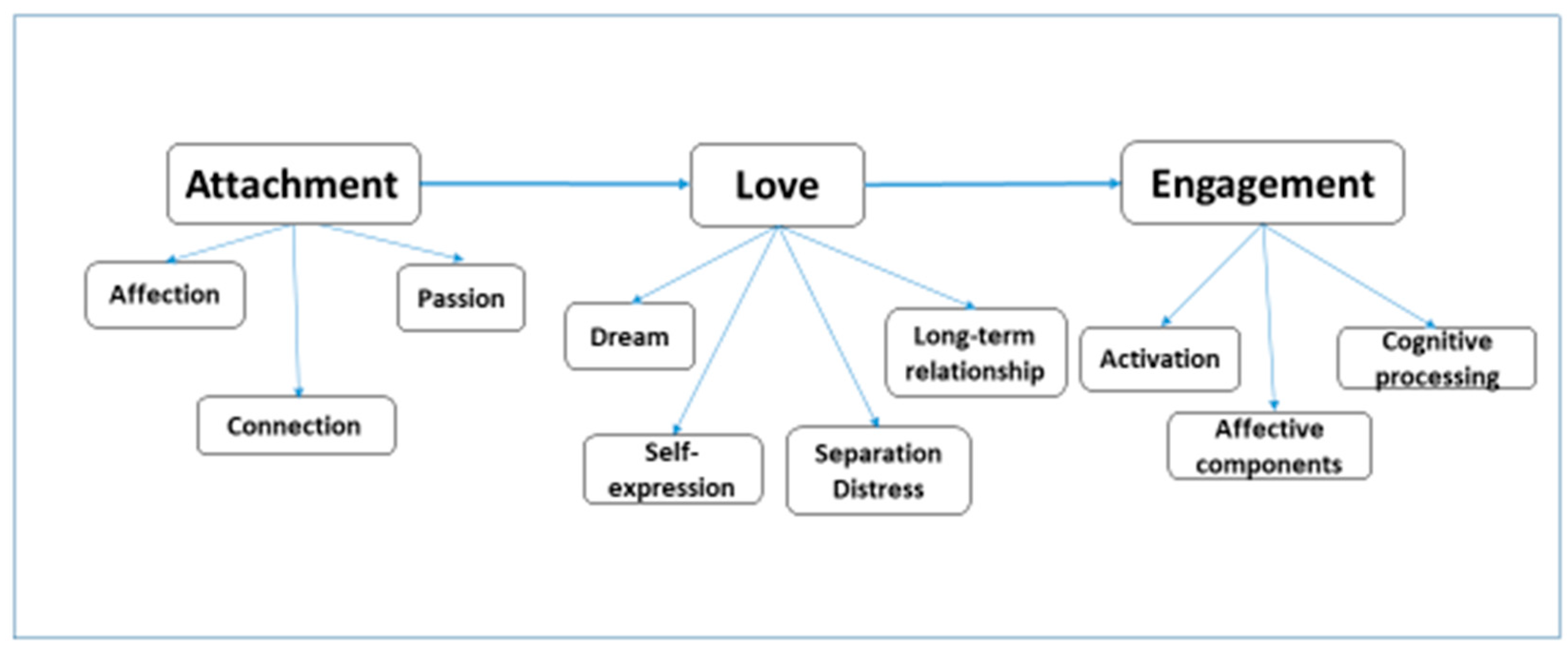

Following the definitions and models tested in empirical study, the three concepts (attachment, love, and engagement) appear to be multidimensional and reflect different constructs. Most of them reflect affective, cognitive, and behavioral dimensions. Nevertheless, they differ both in the breadth of the term and in the degree of connection with the brand. Therefore, exploring how many dimensions exist in each case and the relationships among them is a key issue for empirical analyses. The proposed model implied by these relationships is shown in

Figure 1.

Based upon the literature review explained before and the theoretical framework proposed, our main research hypotheses are as follows.

Previous studies have proposed a direct and positive relationship between brand attachment and brand love, being attachment an antecedent of love. Then:

By integrating all the diverse results obtained in the precedent empirical models (

Carroll and Ahuvia 2006;

Albert et al. 2008;

Batra et al. 2012;

Rauschnabel and Ahuvia 2014;

Gómez-Suárez et al. 2016), brand love could be derived into six dimensions (passion, emotional bonding, separation distress, self-expression), dream, and long-term relationship. However, brand love measure in these past studies seemed to overlap a number of other constructs related to emotional attachment. Thus, in order to minimize the risk of overlap with other brand-related constructs, passion and emotional bonding dimensions were included in the attachment construct, as an antecedent of brand love, being the hypotheses:

Regarding the components of engagement, when comparing dimensions and items, there were some similarities between some affective components. For instance, happiness or being proud, on the scale provided by

Hollebeek et al. (

2014), may be similar to positive emotional connection or positive attitude valence on the scale used by

Batra et al. (

2012). Activation, the time and effort devoted to the brand, on the scale used by

Hollebeek et al. (

2014), had a similar meaning to the long-term relationship variables on the scale used by

Batra et al. (

2012) or by

Albert et al. (

2008).

Vivek et al.’s scale (

2014) also included items related to enthused participation reminiscent of the anticipated separation distress by

Batra et al. (

2012) or social connection, which directly refers to the attachment scale by

Thomson et al. (

2005). For this research,

Hollebeek et al. (

2014) model is chosen, but refining some of the items (see

Appendix B Table A5). Therefore, the hypothesis is:

H5. Engagement is reflected into three dimensions: cognitive processing, affective components and activation (Hollebeek et al. 2014). 4. Research Methods

First, a pilot sample (27 respondents) was used to ensure the wording of the questionnaire was clear, after which some adjustments were made. This pre-test served to clarify the meaning of some confusing items, to analyze incoherent answers, and to test the validity of the scales. Data were collected from a survey of non-student adult participants. Similarly, to the study by

Carroll and Ahuvia (

2006), a cross-sectional survey of non-student adults, ages 21 and up, was carried out. Students in the last year of postgraduate study in marketing with training in market research approached to residents in Madrid (Spain) to complete a ten-minute self-administered questionnaire. These students were given extensive instructions that stressed the importance data purity (e.g., each respondent was to complete the questionnaire independently). They were also trained to meet pre-set quotas and perform adequate fieldwork. The sample was chosen through a careful stratified process according to sex, age, and occupation. Thus, no bias was produced by these sociodemographic variables. The fieldwork was conducted in January 2016. This process produced complete questionnaires from 320 adult consumers.

The questionnaire was created based on the literature review, and all measurement items were adapted from existing instruments. In order to avoid common method bias, the items and questions were prepared to be simple and concise (not including unfamiliar terms or complex syntax). The physical distance between measures was also considered, so that all items of the same construct were not right next to each other.

Common method variance (CMV) was also examined by making some previous estimations with the data. First, we carried out the procedure suggested by

Hair et al. (

2014) to check the absence of outliers. According to this procedure, we standardized each variable and analyzed their descriptive measures. The minimum and the maximum do not surpass the threshold value (4) for samples larger than 80 cases. Second, we connected each indicator to single construct in confirmatory factor analysis (i.e., factor that captures the potential common method variance) instead of separate ones, this estimation led to a significant decrease in the model’s fit (

MacKenzie and Podsakoff 2012). Therefore, CMV did not appear to be a significant problem in the present study.

There was a key previous question. Respondents named a brand for which they felt affection. The approach was similar to the brand elicitations in

Thomson et al. (

2005). Participants provided self-described reasons for this affection. No constraints on the elicitation were imposed. Respondents had the freedom to choose whatever brand they desired from any product category, without regard to preconceived classifications (e.g., goods vs. services; family brands vs. product item brands). Afterwards, they had to describe why they chose that brand, then rating their degree of agreement with a series of items related to the three concepts.

The constructs were measured using pre-developed instruments from the marketing literature.

Appendix B Table A5 provides a list of all the items. The respondents marked their responses on a Likert-type question format (where 1 = strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree).

5. Results

Regarding descriptive results, the respondents mentioned 78 different brands. The most mentioned brands were Apple (21), Coca Cola (20), Zara (18), Nike (9), and Hacendado, Mercadona’s private label for groceries (9). In terms of product category, the most mentioned was textile (20.8%), followed by food (16.5%). Other categories with a high number of mentions were electronics (11.5%), beverages (10.7%), cosmetics (9.7%), and cars (6.9%).

The purification process was based on a sequence of principal components analysis (PCA) with oblimin rotation. This process was undertaken to study the relationships between the different elements of each construct and to determine the items to be included in the confirmatory analyses (CFA). The accumulated variance of the final PCA model was 73.7%. Descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation) and PCA results are presented in

Table 1. Communality and reliability examinations—Cronbach’s alpha—indicated that the final number of items to be included in the CFA model was 11. The dimensions relating to separation distress, self-expression, cognitive processing, and affective engagement did not fulfill the required criteria, either for communality or for reliability. Consequently, they were not included in the next confirmatory model. The PCA model included three factors: attachment (with five items from the connection and affection dimensions), passion (with three items from the dream and passion dimensions), and engagement (three items, two from the activation dimension—engagement, and one from long-term relationship—love).

Next, sequential CFA were run in order to determine psychometric properties and an accurate goodness of fit. These tests were performed using Amos 22.0. (Armonk, NY, USA), according to a maximum likelihood procedure. After four estimations, the achieved final model with three dimensions (attachment, passion, and engagement) lacked discriminant validity (all results can be provided to the readers upon request). Two procedures to test discriminant validity were used: the square inter-construct correlation and the average variance extracted (AVE) comparison (

Fornell and Larcker 1981) (

Table 2); and a comparison of the goodness of fit indexes for two models—free correlations and correlations restricted to the unit (

Anderson and Gerbing 1988) (

Table 3). Both showed a lack of discriminant validity for the passion and attachment constructs that appeared to participate in the same dimension.

An alternative CFA model was then tested (

Table 4). This model had two related dimensions: attachment and engagement. Therefore, the model joined the initial two constructs from attachment and love into a single dimension. To fulfill convergent validity, the item “surprised” from the passion dimension was not included. Next, attachment, a first-order unidimensional construct, comprised four items from those initially proposal by

Thomson et al. (

2005): two from affection, one from connection, and one from passion.

Table 3 shows the parameters and the psychometric properties of this model.

The final structural model is shown in

Table 5. Attachment (λ = 0.404) positively and directly influenced engagement. In addition, attachment was reflected in AFF1 affection (λ = 0.716), AFF2 friendship (λ = 0.724), bonded CON2 (λ = 0.879), and PAS4 captivated (λ = 0.726). Engagement was reflected in the items AC2 (“Whenever I am choosing among various products, it is the brand that I use”; λ = 0.705), and PS7 (“It is the brand that I will use in the future”; λ = 0.776).

6. Discussion and Implications

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first attempt to integrate three different dimensions proposed in the past literature to understand the consumer–brand relationship: attachment, love, and engagement. A better conceptualization of the phenomenon was provided to delimit these terms, providing a simple and integrative scheme.

Related to the research hypotheses,

Table 6 summarizes the main results of our empirical model. Following this table, summarized answers to the research questions are as follows. The conceptual border between the three concepts is not as clear as it initially appeared. In order to answer RQ1—do these dimensions represent the same concept or are they different?—the alternative model shows that there are two dimensions (and not three) that comprised the consumer–brand relationship: attachment and active engagement. Brand love is not a dimension, being actually part of the two other related constructs: attachment and engagement. Passion participates in the attachment dimension, and long-term relationship participates in the engagement dimension. Related to RQ2, whose items define each construct, the number of items is less than expected. Attachment reflects in four items (affection, friendship, bond, captivation) and engagement (activation) reflects in two items (chosen and used, using in the future). Therefore, in relation to RQ3, the three concepts have not been properly measured in the past. When integrating all the dimensions, some constructs and items are not included in the final alternative model. Regarding to RQ4, the two final constructs were both unidimensional instead of multidimensional.

From a managerial point of view, brand managers need to be aware of the importance of understanding certain traits of their target audience to guide the design of those activities aimed at developing affection and a more effective administration of the emotional bond with brands. Therefore, the manufacturers of leading brands must show values and benefits related to the items that help reinforce the affective bond, such as passion or friendship.

The emotional attachment that the consumer can feel towards a brand is represented then by a connection that goes beyond the mere satisfaction of the client and that is built from emotions that generate captivation. For all this, it is convenient that leader companies reinforce the positive values of their brands and, as far as possible, arouse positive and lasting feelings in the consumer. For instance, Coca-Cola associated its brand with happiness, and Danone with the nostalgia of childhood. More recently, the global campaigns of Apple are based on this kind of captivation claim.

When it is possible to reach this state of connection, the consumer considers that the brand has integrated into their life, identifies with it and its values, and likes to show it socially. To achieve these affective bonds with their customers, companies must be willing to offer exclusive experiences, in order to make position themselves as market benchmarks.

In our view, two main drivers can help to develop a strong link between attachment and engagement: consumer experience and coordinated communication strategies, using traditional mass campaigns combined with an accurate personalization.

The sense of captivation is more difficult to develop in mass-market products. However, a brand that provides happiness, pleasure, or positive emotions is probably creating this sensation. These intrinsic rewards are commonplace among brands that adapt to the customer through offers or personalized communication. The brand adopts a dimension of uniqueness based on communication that gives the consumer something else, for instance, offering exclusive care, personalized information, and even a sense of romance. This strategy is particularly intense in the fashion market for luxury brands (Chanel, Dior, Louis Vuitton, Armani, etc.)

Finally, the framework proposed for the consumer–brand relationship is based on the global Marketing 4.0 perspective that emerged by the end of 2016. Its goal is to help organizations reach and engage consumers more fully than in previous years by analyzing shifts in consumers’ behaviors (

Kotler et al. 2017). Thus, Marketing 4.0 emphasizes the need to consider, simultaneously, the “new” and the “old” marketing, to turn consumers into brand main promoters (

Martínez-Ruiz et al. 2017).

The case of Toyota can be used to illustrate this new perspective. Its re-positioning in Europe is based on this kind of connection between the brand and its potential customers. Toyota cars, widely recognized for their reliability, were not leaders in the European markets because this attribute was not appealing for consumers. In 2017, the company decided to change their differentiation pattern by focusing on two different attributes: mobility and ecological motors. Communication managers in Spain decide to risk with a very different message “Drive as you think”, emphasizing the bond with the consumer based on ecological values: Toyota hybrid cars help to conserve the planet. Some ads were even risking the sale of their brand since they urge drivers to park the Yaris Hybrid car and take the bus. This campaign—appealing to emotions and connecting with the new millennial consumer—has been a great success, activating the consumers’ wish for this brand. Those loyal to the brand before changed from gasoline to hybrid Toyota cars. Those new in the market chose this brand or will choose it in the future. The global ad campaign in Spain is winning advertisement prizes, and the social networks made the slogan viral, with very positive comments that showed the consumers’ admiration. This produced a multiplying presence of Toyota everywhere, with news in traditional media (magazines, newspapers, or TV). This finally has turned into sales, since half of the hybrid models were sold by Toyota in 2018. In market share terms, this brand has occupied the first place in sales, surpassing Volkswagen, the traditional leader in the Spanish market.

7. Limitations and Future Research

The present study has several limitations, specifically in its exploratory nature, the use of a small sample, and the need to establish a better control of different possible segments a priori. Although participants were consumers, non-student adults, and carefully chosen through a stratification process, the sample was chosen by convenience; therefore, caution should be taken when generalizing the results. In addition, the final model lost many initial items in the purification process through PCA and CFA, in order to fulfill all the requirements for psychometric properties. The reduction in the number of items may seem drastic, but this was the only method that could possibly reproduce an accurate statistical SEM model. Furthermore, as the study was conducted among consumers in Spain, it should be tested further, using participants from a variety of cultures and locations, to enhance the validity and reliability of the results. However, studies on consumer–brand relationships have been completed in cultural environments that differ from the Spain. Thus, considering the cultural determinants, this research provides new empirical evidence about the Spanish context.

Future studies could further employ qualitative and quantitative methods that enhance the robustness and generalizability of the findings, such as in-depth interviews, longitudinal studies, or experiments. For instance, the last method will allow the comparison of different segments, such as groups of “traditional” and “social media” consumers, both in high/low involvement consumption contexts. Maybe these groups perceive attachment or engagement differently, and a new model could better explain their perceptions.

Furthermore, there is a need to investigate the managerial relevance related to the identification of actionable variables for these constructs. Self-congruity or identification could represent antecedents for attachment. Further research could assess the relative strength of the constructs that compose the output of the process, such as word-of-mouth, loyalty, trust, and commitment. Such an assessment would provide both academic researchers and practitioners with valuable results.