Developing the Marketing Experience to Increase Shopping Time: The Moderating Effect of Visit Frequency

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Sensory Experience

2.2. Intellectual Experience

2.3. Social Experience

2.4. Pragmatic Experience

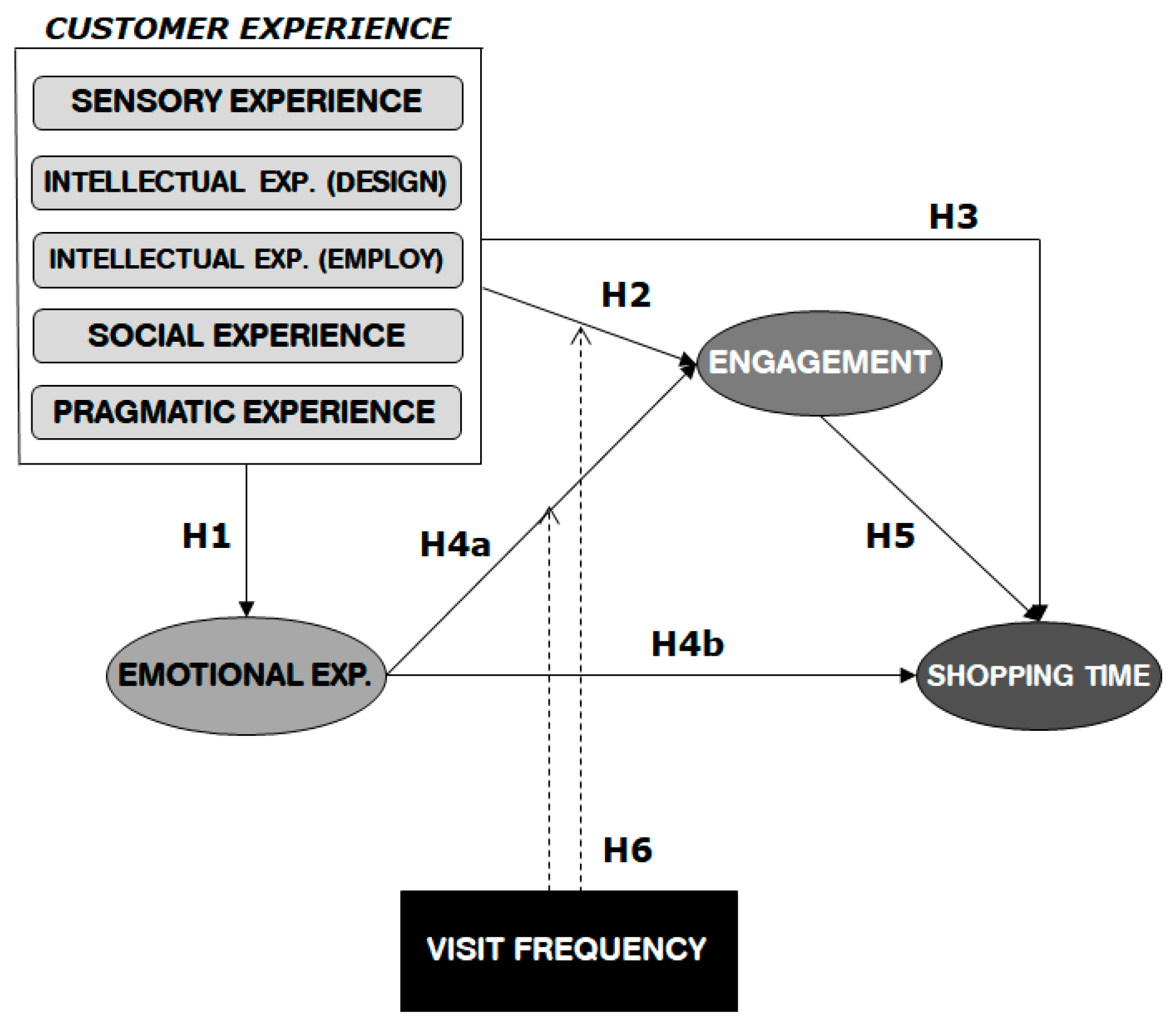

3. Research Model and Hypotheses

3.1. Effects of Experience Dimensions (Sensory, Intellectual, Social, and Pragmatic)

3.2. Consequences of Emotional Experience

3.3. Moderating Effect of Visit Frequency

4. Research Methodology

4.1. Research Scope

4.2. Research Design and Measurement Scales

5. Data Analysis

6. Results

6.1. Research Reliability and Measurement Scales

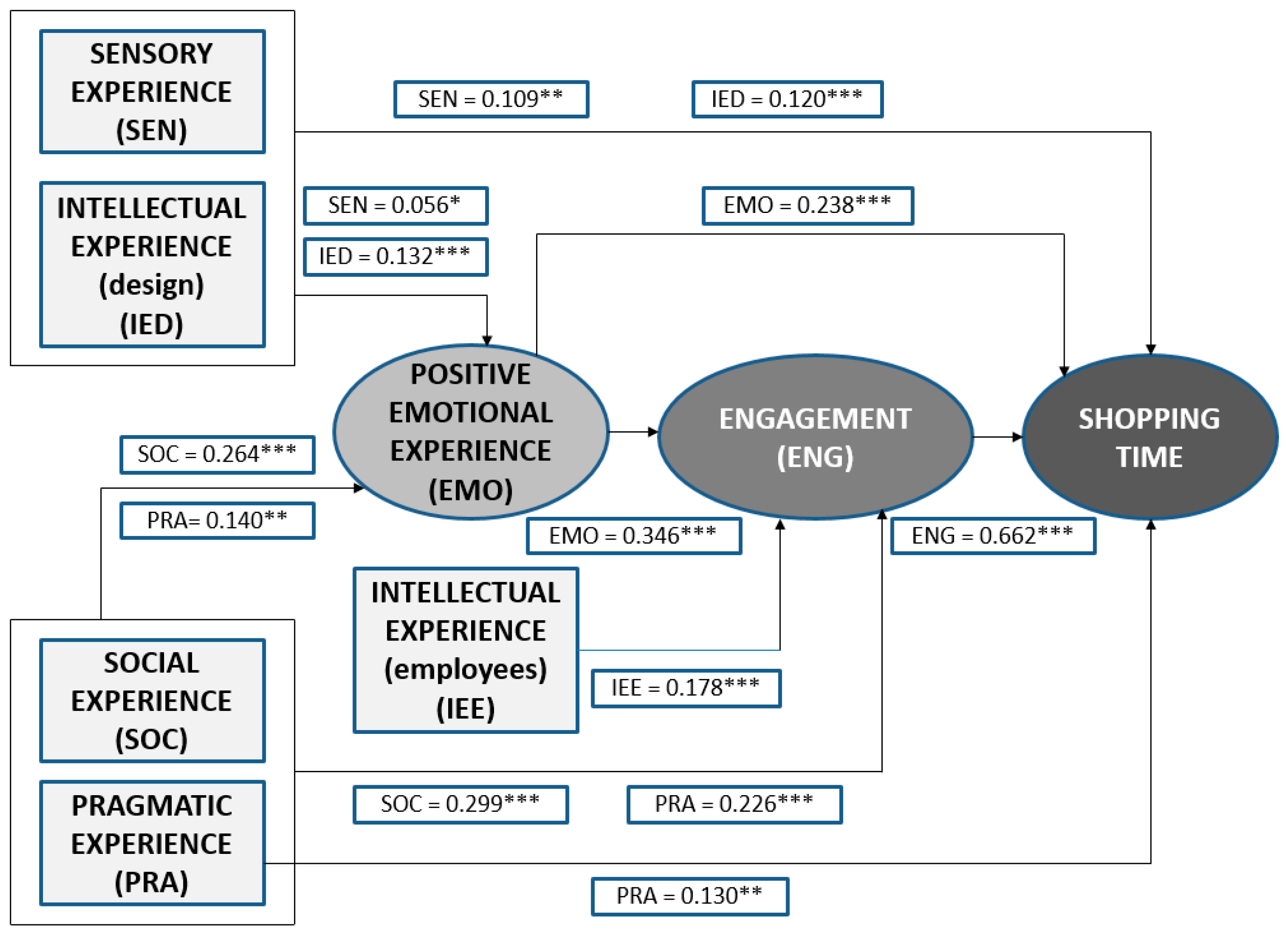

6.2. Estimation of the Structural Model

6.3. The Mediating Effect of Positive Emotional Experience

6.4. The Moderating Effect of Visit Frequency

7. Discussion

8. Conclusions

Managerial Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ackerman, Joshua M., Christopher C. Nocera, and John A. Bargh. 2010. Incidental haptic sensations influence social judgments and decisions. Science 328: 1712–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adam, Marc T., Jan Krämer, and Marius B. Müller. 2015. Auction fever! How time pressure and social competition affect bidders’ arousal and bids in retail auctions. Journal of Retailing 91: 468–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, Icek, and Martin Fishbein. 1980. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behaviour. Upper Saddle River: Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Alba, Joseph W., and Elanor F. Williams. 2013. Pleasure principles: A review of research on hedonic consumption. Journal of Consumer Psychology 23: 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaro, Elena. 2012. El ABC Del Shopping Experience. Cómo Generar Experiencias Para Vender MÁS. Madrid: Wolters Kluwer España. [Google Scholar]

- Andreu, Luisa, Enrique Bigné, Ruben Chumpitaz, and Valérie Swaen. 2006. How does the perceived retail environment influence consumers’ emotional experience? Evidence from two retail settings. The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research 16: 559–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, Mark J., and Kristy E. Reynolds. 2003. Hedonic shopping motivations. Journal of Retailing 79: 77–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, Richard P., Mahesh Gopinath, and Prashanth U. Nyer. 1999. The role of emotions in marketing. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 27: 184–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, Reuben M., and David A. Kenny. 1986. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 51: 1173–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beatty, Sharon E., Kristy E. Reynolds, Stephanie M. Noble, and Mary P. Harrison. 2012. Understanding the relationships between commitment and voice: Hypotheses, empirical evidence, and directions for future research. Journal of Service Research 15: 296–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, Adilson, Jean-Charles Chebat, and Barry J. Babin. 2010. Does a companion always enhance the shopping experience? Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 17: 294–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowden, Jana L. 2009. The process of customer engagement: A conceptual framework. Journal of Marketing Theory & Practice 17: 63–74. [Google Scholar]

- Brakus, J. Joško, Bernd H. Schmitt, and Lia Zarantonello. 2009. Brand experience: What is it? How is it measured? Does it affect loyalty? Journal of Marketing 73: 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodie, Roderick, Linda Hollebeek, Biljana Juric, and Ana Ilić. 2011. Customer engagement: Conceptual domain, fundamental propositions, and implications for research. Journal of Service Research 14: 252–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brun, Isabelle, Lova Rajaobelina, Line Ricard, and Bilitis Berthiaume. 2017. Impact of customer experience on loyalty: A multichannel examination. The Service Industries Journal 37: 317–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cachero, Silvia, and Rodolfo Vázquez. 2017. Living positive experiences in store: How it influences shopping experience value and satisfaction? Journal of Business Economics and Management 18: 537–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmigniani, Julie, and Borko Furht. 2011. Augmented reality: An overview. In Handbook of Augmented Reality. Edited by Borko Furht. New York: Springer, pp. 3–46. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Hyo-Jung, Molly Eckman, and Ruoh-Nan Y. Yan. 2011. Application of the Stimulus-Organism-Response model to the retail environment: The role of hedonic motivation in impulse buying behavior. The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research 21: 233–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claffey, Ethel, and Mairead Brady. 2014. A model of consumer engagement in a virtual customer environment. Journal of Customer Behaviour 13: 325–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curth, Susane, Sebastian Uhrich, and Martin Benkenstein. 2014. How commitment to fellow customers affects the customer-firm relationship and customer citizenship behavior. Journal of Services Marketing 28: 147–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ruyter, Ko, Luci Moorman, and Jos Lemmink. 2001. Antecedents of commitment and trust in customer–supplier relationships in high technology markets. Industrial Marketing Management 30: 271–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deloitte. 2016. Digital and Asociación DEC. I Estudio Nacional Sobre el Nivel de “Operativización” de la Experiencia de Cliente. Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/es/es/pages/operations/articles/OCX-estudio-operativizacion-experiencia-cliente.html (accessed on 12 May 2018).

- Evanschitzky, Heiner, Gopalkrishnan R. Iyer, Hilke Plassmann, Joerg Niessing, and Heribert Meffert. 2006. The relative strength of affective commitment in securing loyalty in service relationships. Journal of Business Research 59: 1207–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, Ronald J., Michéle Paulin, and Jasmin Bergeron. 2010. Customer sociability and the total service experience: Antecedents of positive word-of-mouth intentions. Journal of Service Management 21: 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroudi, Pantea, Zhongeqi Jin, Suraksha Gupta, TC Melewar, and Mohammad M. Foroudi. 2016. Influence of innovation capability and customer experience on reputation and loyalty. Journal of Business Research 69: 4882–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallace, Alberto, and Charles Spence. 2014. In Touch with the Future: The Sense of Touch from Cognitive Neuroscience to Virtual Reality. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gentile, Chiara, Nicola Spiller, and Giuliano Noci. 2007. How to sustain the customer experience: An overview of experience components that co-create value with the customer. European Management Journal 25: 395–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, Miriam. 2015. Haptics: The new wave of tactics for customer experience. International Journal of Information & Futuristic Research 2: 2606–11. [Google Scholar]

- Geyskens, Inge, Jan B. E. Steenkamp, Lisa K. Scheer, and Nirmalya Kumar. 1996. The effects of trust and interdependence on relationship commitment: A trans-Atlantic study. International Journal of Research in Marketing 13: 303–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, Michael J., William B. Swann, Jr., and David H. Silvera. 1998. On the genesis of confidence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 75: 1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilliand, David I., and Daniel C. Bello. 2002. Two sides to attitudinal commitment: The effect of calculative and loyalty commitment on enforcement mechanisms in distribution channels. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 30: 24–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewal, Dhruv, Michael Levy, and Vijay Kumar. 2009. Customer experience management in retailing: An organizing framework. Journal of Retailing 85: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewal, Dhruv, Anne L. Roggeveen, and Jens Nordfält. 2017. The future of retailing. Journal of Retailing 93: 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, Joseph F., William C. Black, Barry J. Babin, Rolph E. Anderson, and Ronald L. Tatham. 2010. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective, 7th ed. Upper Saddle River: Pearson Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, Andrew F. 2013. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation and Conditional Process Analysis. A Regression Based Approach. New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Helkkula, Anu. 2011. Characterising the concept of service experience. Journal of Service Management 22: 367–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, Krista, Paul W. Fombelle, and Nancy J. Sirianni. 2016. Shopping under the influence of curiosity: How retailers use mystery to drive purchase motivation. Journal of Business Research 69: 1028–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbrook, Morris B., and Elizabeth C. Hirschman. 1982. The experiential aspects of consumption: Consumer fantasies, feelings, and fun. Journal of Consumer Research 9: 132–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollebeek, Linda. 2011. Demystifying customer brand engagement: Exploring the loyality nexus. Journal of Marketing Management 27: 785–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmbeck, Grayson N. 1997. Toward terminological, conceptual and statistical clarity in the study of mediadors and moderators: Examples from the child-clinical and pediatric psychology literatures. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psycholog 65: 599–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homburg, Christian, Danijel Jozic, and Christina Kuehnl. 2017. Customer experience management: Toward implementing and evolving marketing concept. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 45: 377–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, Chieng-Lu, Chia-Chang Liu, and Yuan-Duen Lee. 2010. Effect of commitment and trust towards micro-blogs on consumer behavioral intention: A relationship marketing perspective. International Journal of Electronic Business Management 8: 292–303. [Google Scholar]

- Iacobucci, Dawn. 2008. Mediation Analysis. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- IBM. 2012. Retail 2020: Reinventando la Distribución Minorista (UNA VEZ MÁS). Available online: https://www-05.ibm.com/services/es/bcs/pdf/REW03013-ESES-01_HR.pdf (accessed on 6 November 2017).

- Iglesias, Víctor, and Rodolfo Vázquez. 2001. The moderating effects of exclusive dealing agreements on distributor satisfaction. Journal of Strategic Marketing 9: 215–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias, Oriol, Jatinder J. Singh, and Joan M. Batista-Foguet. 2011. The role of brand experience and affective commitment in determining brand loyalty. Journal of Brand Management 18: 570–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaccard, James, Choi K. Wan, and Jim Jaccard. 1996. Lisrel Approaches to Interaction Effects in Multiple Regression. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Javornik, Ana. 2016. Augmented reality: Research agenda for studying the impact of its media characteristics on consumer behaviour. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 30: 252–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Mark S., Eugene Sivadas, and Ellen Garbarino. 2008. Customer satisfaction, perceived risk and affective commitment: An investigation of directions of influence. Journal of Services Marketing 22: 353–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, Barbara E. 2017. Using visual design to improve customer perceptions of online assortments. Journal of Retailing 93: 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaltcheva, Velitchka D., and Barton A. Weitz. 2006. When should a retailer create an exciting store environment? Journal of Marketing 70: 107–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Sooyun, Geebum Park, Yeonjoo Lee, and Sunmee Choi. 2016. Customer emotions and their triggers in luxury retail: Understanding the effects of customer emotions before and after entering a luxury shop. Journal of Business Research 69: 5809–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, Aradhna. 2006. Interaction of senses: The effect of vision versus touch on the elongation bias. Journal of Consumer Research 32: 557–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, Aradhna. 2013. Customer Sense: How the 5 Senses Influence Buying Behavior. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Krishna, Aradhna, and Maureen Morrin. 2008. Does touch affect taste? The perceptual transfer of product container haptic cues. Journal of Consumer Research 34: 807–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, Aradhna, Ryan Elder, and Cindy Caldara. 2010. Feminine to smell but masculine to touch? Multisensory congruence and its effect on the aesthetic experience. Journal of Consumer Psychology 20: 410–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladhari, Riadh, Nizar Souiden, and Beatrice Dufour. 2017. The role of emotions in utilitarian service settings: The effects of emotional satisfaction on product perception and behavioral intentions. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 34: 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawton, Stuart. 2016. Exploring the meal experience: Customer perceptions of dark-dining. In Food Science, Production, and Engineering in Contemporary Economies. IGI Global: Hershey, pp. 225–44. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Jiunn-Ger T., Jai-Ok Kim, and So Young Lee. 2009. An empirical examination of perceived retail crowding, emotions, and retail outcomes. The Service Industries Journal 29: 635–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangleburg, Tamara F., Patricia M. Doney, and Terry Bristol. 2004. Shopping with friends and teens’ susceptibility to peer influence. Journal of Retailing 80: 101–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, Satya, and Dilip Soman. 2002. Managing the power of curiosity for effective web advertising strategies. Journal of Advertising 31: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, Prashant, Madhupa Bakshi, and Ramendra Singh. 2016. Impact of consumption emotions on WOM in movie consumption: Empirical evidence from emerging markets. Australasian Marketing Journal 24: 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollen, Anne, and Hugh Wilson. 2010. Engagement, telepresence and interactivity in online consumer experience: Reconciling scholastic and managerial perspectives. Journal of Business Research 63: 919–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, António C., Nuno Fortes, and Ramiro Santiago. 2017. Influence of sensory stimuli on brand experience, brand equity and purchase intention. Journal of Business Economics and Management 18: 68–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasermoadeli, Amir, Kwek C. Ling, and Farshad Maghnati. 2013. Evaluating the impacts of customer experience on purchase intention. International Journal of Business and Management 8: 128–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orth, Ulrich R., and Jochen Wirtz. 2014. Consumer processing of interior service environments: The interplay among visual complexity, processing fluency, and attractiveness. Journal of Service Research 17: 296–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penz, Elfriede, and Margaret Hogg. 2011. The role of mixed emotions in consumer behavior: Investigating ambivalence in consumers’ experiences of approach-avoidance conflicts in online and offline settings. European Journal of Marketing 45: 104–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, Andrea, and Ignacio R. Del Bosque. 2015. An integrative framework to understand how CSR affects customer loyalty through identification, emotions and satisfaction. Journal of Business Ethics 129: 571–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pine, B. Joseph, Joseph Pine, and James H. Gilmore. 1999. The Experience Economy: Work Is Theatre & Every Business a Stage. Brighton: Harvard Business Press. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, Kristopher J., and Andrew F. Hayes. 2004. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments & Computers 36: 717–31. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, Kristopher J., and Andrew F. Hayes. 2008. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods 40: 879–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quartier, Katelijn, Jan Vanrie, and Koenraad Van Cleempoel. 2014. The Mediating Role of Consumers’ Perception of Atmosphere on Emotions and Behavior. A Study to Analyze the Impact of Lighting in Food Retailing. Available online: www.academia.edu/download/13148766/final2_1.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2017).

- Roy, Abhik. 1994. Correlates of mall visit frequency. Journal of Retailing 70: 139–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachdeva, Ishita, and Sushma Goel. 2015. Role of store atmospherics on customer experience. International Journal of Multidisciplinary Approach & Studies 2: 72–83. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, Bernd. 1999. Experiential marketing. Journal of Marketing Management 15: 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, Bernd H. 2003. Customer Experience Management: A Revolutionary Approach to Connecting with Your Customers. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Scholz, Joachim, and Andrew N. Smith. 2016. Augmented reality: Designing immersive experiences that maximize consumer engagement. Business Horizons 59: 149–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Shaun, and Joe Wheeler. 2002. Managing the Customer Experience: Turning Customers into Advocates. London: Pearson Education. [Google Scholar]

- Spence, Charles. 2012. Managing sensory expectations concerning products and brands: Capitalizing on the potential of sound and shape symbolism. Journal of Consumer Psychology 22: 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, Charles, and Alberto Gallace. 2011. Multisensory design: Reaching out to touch the consumer. Psychology & Marketing 28: 267–308. [Google Scholar]

- Spence, Charles, Nancy M. Puccinelli, Dhruv Grewal, and Anne L. Roggeveen. 2014. Store atmospherics: A multisensory perspective. Psychology & Marketing 31: 472–88. [Google Scholar]

- Spinelli, Sara, Camila Masi, Gian Paolo Zoboli, John Prescott, and Erminio Monteleone. 2015. Emotional responses to branded and unbranded foods. Food Quality and Preference 42: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, Mala, and Dimple Kaul. 2014. Social interaction, convenience and customer satisfaction: The mediating effect of customer experience. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 21: 1028–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swinyard, William R. 1998. Shopping mall customer values: The national mall shopper and the list of values. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 5: 167–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tantanatewin, Warakul, and Vorapat Inkarojrit. 2016. Effects of color and lighting on retail impression and identity. Journal of Environmental Psychology 46: 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tauber, Edward M. 1972. Why do people shop? Journal of Marketing 36: 46–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsaur, Sheng-Hshiung, Yi-Ti Chiu, and Chih-Hung Wang. 2007. The visitors behavioral consequences of experiential marketing: An empirical study on Taipei Zoo. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing 21: 47–64. [Google Scholar]

- Tsiotsou, Rodoula. 2006. Using visit frequency to segment ski resorts customers. Journal of Vacation Marketing 12: 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoef, Peter C., Katherine N. Lemon, Ananthanarayanan Parasuraman, Anne Roggeveen, Michael Tsiros, and Leonard A. Schlesinger. 2009. Customer experience creation: Determinants, dynamics and management strategies. Journal of Retailing 85: 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, Valter A., and Claudio V. Torres. 2014. The effect of motivational orientation over arousal-shopping response relationship. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 21: 158–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivek, Shiri D., Sharon E. Beatty, Vivek Dalela, and Robert M. Morgan. 2014. A generalized multidimensional scale for measuring customer engagement. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice 22: 401–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, Gianfranco, Edward Shiu, Louise M. Hassan, Nina Michaelidou, and Sharon E. Beatty. 2011. Emotions, store-environmental cues, store-choice criteria, and marketing outcomes. Journal of Business Research 64: 737–44. [Google Scholar]

- Wedel, Michel, and Rik Pieters. 2015. The buffer effect: The role of color when advertising exposures are brief and blurred. Marketing Science 34: 134–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiener, Hillary J., and Tanya L. Chartrand. 2014. The effect of voice quality on ad efficacy. Psychology & Marketing 31: 509–17. [Google Scholar]

- Zaltman, Gerald, and Nancy Puccinelli. 2000. Strategic Use of Music in Marketing: A Selective Review [Case Study]. Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Zielke, Stephan. 2011. How store lightning influences store atmosphere, price and quality perceptions and shopping intention. Paper present at the European Marketing Academy Conference, Ljubljana, Slovenia, May 24–27. [Google Scholar]

| Sense | Author | Descriptions |

|---|---|---|

| Visual | Sachdeva and Goel (2015); Orth and Wirtz (2014); Kahn (2017); Wedel and Pieters (2015); Zielke (2011); Tantanatewin and Inkarojrit (2016) | This type of experience focuses on colors, shapes, distance, article size, lighting, or digital merchandising. It is the most direct way to provide information to consumers, either offline, online, or through advertising exhibitions, attracting them to the shop and trying to get the consumer to remember and “record” in their mind. Designing a good visual experience is decisive for a retailer, given that 90% of the information received by the brain is visual. The most studied factor is the impact of color as a trigger in the decision to shop and choose a brand. |

| Scent | Spence et al. (2014); Krishna (2013) | The stimulation of smell is a marketing tool of great potential, since it allows the retailer to generate affective states, promote a product, positioning a brand, or to assign “exclusive aromas” to a retailer and to differentiate it from the competition. In addition, it is also used to stimulate impulse-buying at store. For the scent experience to produce greater positive effects, there needs to be congruence between the smell, the desired environment for a retailer, the product offered, and/or the profile of the target buyer. |

| Auditory | Zaltman and Puccinelli (2000); Wiener and Chartrand (2014) | The sense of hearing is constantly active, making it an interesting point of attention for retailers who wish to apply sensory marketing to their store. It is not just about experiencing the sound, but trying to create, through music and the voice, a link with the consumer, facilitating the representation of the brand in the consumers’ minds, and creating associations that activate emotions and experiences. The review of the literature places special emphasis on the use of music as a tool to create the store image in the consumer’s mind, as well as the identity of the brand. In addition, it can help to change the mood and to create sensations that help customers to extend their shopping time. |

| Taste | Lawton (2016); Krishna (2013) | The sense of taste has been studied in the field of food and beverage products. The responses to different flavors are programmed genetically, instead of being learned or linked to experience, but they are highly influenced by the rest of the senses, so that taste can be considered as a mix of the rest of the senses, since these can affect the perception of the consumer’s taste. This raises many possibilities of action to retailers that offer food and drink products, since they can link their products with certain scents to modify the behavior of consumers. |

| Tactile | George (2015); Gallace and Spence (2014); Ackerman et al. (2010) | Touching a product is fundamental when generating consumer information, given that the integration of these tactile perceptions in their behavior facilitates the purchase decision. Being able to touch the products and to experiment with them, intentionally or not, makes the customer–product relationship much closer, thus favoring the possibility of purchase. Although we have tactile sensors in all parts of our body, marketing research has focused on the hands as a primary source of the perceptual system: they are the “outer brain” of a person. |

| Multisensory | Krishna et al. (2010); Spence and Gallace (2011); Spence et al. (2014); Krishna (2006); Krishna and Morrin (2008); Spence (2012) | The review of the literature recognizes and identifies different sensory modalities, since consumers rarely process information using only one sense. There are, therefore, multisensory interactions, whose responses are more positive than if only one of the senses was used. Thus, the study of these interactions is of great interest, since they can facilitate consumer perceptions, attitudes, and preferences. |

| Survey type | Structured questionnaire |

| Universe | Customers of offline stores that have recently made a purchase in the sectors selected for the study |

| Geographical scope | Spain |

| Sampling procedure | By sex and age |

| Sampling size | 527 valid surveys |

| Sampling error | ±4.27% |

| Desire level of confidence | 95%; p = q = 0.5 |

| Factors | λ Stand. | CR | AVE | α Cronbach |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Emotional Experience | 0.946 | 0.746 | 0.945 | |

| Happy | 0.878 | |||

| Excited | 0.877 | |||

| Entertaining | 0.828 | |||

| Animated | 0.880 | |||

| Enthusiastic | 0.904 | |||

| Surprised (favorably) | 0.811 | |||

| Sensory Experience | 0.894 | 0.587 | 0.891 | |

| Temperature is suitable, activating the shopping experience | 0.684 | |||

| Cleanliness and good condition, stimulating the shopping experience | 0.816 | |||

| Lighting is motivating, making the shopping experience pleasant | 0.849 | |||

| Color of the walls and floor provide a shopping experience in a pleasant environment | 0.853 | |||

| Music (tempo, volume, and type) provides a very pleasant shopping experience | 0.692 | |||

| Smells provides a very pleasant shopping experience | 0.680 | |||

| Intellectual Experience (Design) | 0.904 | 0.574 | 0.903 | |

| Design (furniture, decoration and equipment) stimulates consumer curiosity | 0.784 | |||

| Section design stimulates the shopping experience and interactions with the product | 0.761 | |||

| Communication materials (display) stimulate imagination and consumer creativity | 0.761 | |||

| Store layout stimulates curiosity | 0.828 | |||

| Shop-window offers an attractive presentation (artistic, creative) | 0.719 | |||

| Store has a pleasant entry (spacious and inviting) | 0.727 | |||

| Outside of the store design invites you to enter | 0.717 | |||

| Intellectual Experience (Employees) | 0.868 | 0.628 | 0.869 | |

| Employees are always willing to help (provide information, support decision-making) and answer all customer questions | 0.882 | |||

| Employees have great knowledge of what they sell and the experiences that the products provide | 0.902 | |||

| There are enough employees to offer personalized services and to explain the experiences provided by the use of products | 0.749 | |||

| Payment for the items purchased is fast, avoiding negative experiences | 0.600 | |||

| Social Experience | 0.808 | 0.587 | 0.797 | |

| Shopping at this store gives me the opportunity to experience the feeling of status (interactions with other customers) | 0.760 | |||

| Shopping at this store allows me to obtain information and experiences on trends that are consistent with my lifestyle | 0.862 | |||

| Going to this store allows me to spend a pleasant time with my family/friends | 0.663 | |||

| Pragmatic Experience | 0.743 | 0.492 | 0.866 | |

| Price | 0.764 | |||

| Product | 0.684 | |||

| Promotion | 0.651 | |||

| Engagement | 0.932 | 0.822 | 0.931 | |

| I am very proud to be a customer of this store | 0.899 | |||

| I feel like I identify with the values and objectives of this company | 0.920 | |||

| I am loyal to this company because I like the relationship that I have with it | 0.900 | |||

| Extended Shopping Time | 0.839 | 0.635 | 0.837 | |

| Spending more time searching for information in this store is a good idea | 0.768 | |||

| If I had more time I would extend my stay in the store | 0.791 | |||

| The time I’ve spent in this store has been worth it | 0.830 | |||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Positive emotional experience | 0.746 ᴬ | |||||||

| 2. Sensory experience | 0.047 ᴮ | 0.587 | ||||||

| 3. Intellectual (design) experience | 0.090 | 0.448 | 0.574 | |||||

| 4. Intellectual (employees) experience | 0.052 | 0.121 | 0.160 | 0.628 | ||||

| 5. Social experience | 0.150 | 0.315 | 0.480 | 0.336 | 0.587 | |||

| 6. Pragmatic experience | 0.109 | 0.260 | 0.320 | 0.329 | 0.357 | 0.492 | ||

| 7. Engagement | 0.259 | 0.072 | 0.123 | 0.202 | 0.316 | 0.277 | 0.822 | |

| 8. Extended shopping time | 0.386 | 0.059 | 0.149 | 0.145 | 0.300 | 0.304 | 0.425 | 0.635 |

| Structural Relationships | Standardized Coef. | t-Value |

|---|---|---|

| H1a: Sensory experience → Positive emotional experience | 0.056 | 1.948 * |

| H1b: Intellectual experience (design) → Positive emotional experience | 0.132 | 3.045 *** |

| H1c: Intellectual experience (employees) → Positive emotional experience | ns | ns |

| H1d: Social experience → Positive emotional experience | 0.264 | 5.398 *** |

| H1e: Pragmatic experience → Positive emotional experience | 0.140 | 2.764 ** |

| H2a: Sensory experience → Engagement | ns | ns |

| H2b: Intellectual experience (design) → Engagement | ns | ns |

| H2c: Intellectual experience (employees) → Engagement | 0.178 | 4.510 *** |

| H2d: Social experience → Engagement | 0.299 | 6.671 *** |

| H2e: Pragmatic experience → Engagement | 0.226 | 4.515 *** |

| H3a: Sensory experience → Shopping time | 0.109 | 3.053 ** |

| H3b: Intellectual experience (design) → Shopping time | 0.120 | 3.536 *** |

| H3c: Intellectual experience (employees) → Shopping time | ns | ns |

| H3d: Social experience → Shopping time | ns | ns |

| H3e: Pragmatic experience → Shopping time | 0.130 | 3.154 ** |

| H4a: Positive emotional experience → Engagement | 0.346 | 6.932 *** |

| H4b: Positive emotional experience → Shopping time | 0.238 | 5.518 *** |

| H5: Engagement → Shopping time | 0.662 | 11.571 *** |

| Relationship between Factors | Significant Effect | Mediation of Positive Emotional Experience |

|---|---|---|

| Sensory experience → Engagement | Only indirect (through positive emotions) | Total |

| Intellectual experience (design) → Engagement | Only indirect (through positive emotions) | Total |

| Intellectual experience (employees) → Engagement | YES (only direct) | No |

| Social experience → Engagement | YES (direct) YES (indirect) (through positive emotions) | Partial |

| Pragmatic experience → Engagement | YES (direct) YES (indirect) (through positive emotions) | Partial |

| Type of Experience | Effect of Each Type of Experience on Engagement | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct | Indirect | Totals | |

| Sensory | NO | Sensory → Positive emotional experience Positive emotional experience → Engagement (0.056)(0.346) = 0.019 | 0.019 |

| Intellectual (design) | NO | Intellectual (design) → Positive emotional experience Positive emotional experience → Engagement (0.132)(0.346) = 0.046 | 0.046 |

| Intellectual (employees) | 0.178 | NO | 0.178 |

| Social | 0.299 | Social → Positive emotional experience Positive emotional experience → Engagement (0.264)(0.346) = 0.091 | 0.390 |

| Emotional | 0.346 | NO | 0.346 |

| Pragmatic | 0.226 | Pragmatic → Positive emotional experience Positive emotional experience → Engagement (0.140)(0.346) = 0.048 | 0.274 |

| Causal Relationships | High Visit Frequency (N = 206) | Low Visit Frequency (N = 321) |

|---|---|---|

| β (t-Student) | β (t-Student) | |

| Sensory experience → Engagement | NS | NS |

| Intellectual experience (design) → Engagement | NS | NS |

| Intellectual experience (employees) → Engagement | 0.210 (3.571) | 0.175 (3.159) |

| Social experience → Engagement | 0.377 (5.190) | 0.254 (4.533) |

| Pragmatic experience → Engagement | 0.284 (3.458) | 0.166 (2.746) |

| Positive emotional experience → Engagement | 0.353 (4.213) | 0.302 (5.322) |

| Fit of Goodness | BBNNFI = 0.873; CFI = 0.892; RMSEA = 0.053 | |

| Causal Relationships | df | χ2 Differences between High and Low Visit Frequency | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensory experience → Engagement | 1 | 0.049 | 0.825 |

| Intellectual experience (design) → Engagement | 1 | 0.144 | 0.704 |

| Intellectual experience (employees) → Engagement | 1 | 1.107 | 0.293 |

| Social experience → Engagement | 1 | 4.666 | 0.033 |

| Pragmatic experience → Engagement | 1 | 3.847 | 0.050 |

| Positive emotional experience → Engagement | 1 | 5.400 | 0.023 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cachero-Martínez, S.; Vázquez-Casielles, R. Developing the Marketing Experience to Increase Shopping Time: The Moderating Effect of Visit Frequency. Adm. Sci. 2018, 8, 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci8040077

Cachero-Martínez S, Vázquez-Casielles R. Developing the Marketing Experience to Increase Shopping Time: The Moderating Effect of Visit Frequency. Administrative Sciences. 2018; 8(4):77. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci8040077

Chicago/Turabian StyleCachero-Martínez, Silvia, and Rodolfo Vázquez-Casielles. 2018. "Developing the Marketing Experience to Increase Shopping Time: The Moderating Effect of Visit Frequency" Administrative Sciences 8, no. 4: 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci8040077

APA StyleCachero-Martínez, S., & Vázquez-Casielles, R. (2018). Developing the Marketing Experience to Increase Shopping Time: The Moderating Effect of Visit Frequency. Administrative Sciences, 8(4), 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci8040077