Abstract

This study aimed to explore the employment status of women in the higher educational sector and to uphold women’s productivity and commitment in executive positions of responsibility. Management tended to show preferential treatment for men in top management positions; hence, women were less engaged in the decision-making process. Women possess the potential to be transformative leaders in higher education institutions (HEI). The research purpose of this study was to speculate that some Lebanese educational institutions still practice discrimination and prefer men over women in executive positions, as well as to show that excellence in educational institutions is linked to women being in these executive positions. Currently, the higher education sector in Lebanon is under development as numerous educational developments are being implemented. The problem is that a peculiar attitude toward women in the HEI sector and specifically in top management positions still exists. In this study, the author explored women’s engagement at the top levels of higher education management and found that only 15 out of 65 Dean’s positions were filled by women and aimed to discover the factors behind the misrepresentation of women within the higher education system in Lebanon. In addition, the study found a positive relationship between the presence of women and the performance of HEIs. In this study, I aimed to focus on women’s engagement at the top management level and to emphasize the advantages of their skills and expertise, as well as to enhance the presence of women. The findings were significant and clear: There was misrepresentation, bias and stereotyping in HEIs. A clear strategic plan is needed to engage women in the decision-making process along with a well-designed incentive plan to achieve the required purpose. The aim of this study was to highlight this matter and to accentuate the benefit of women’s leadership roles in higher education in Lebanon. A qualitative strategy was used: Primary information was obtained from interviews with 12 chairpersons at six different schools. Data were gathered and analyzed to provide insightful results and recommendations.

Different studies have confirmed that women are still inadequately represented in top management positions. However, this study aimed to explore the employment status of women in the higher educational sector to shed light on and to uphold women’s productivity and commitment in executive positions of responsibility. Management tended to show preferential treatment for men in top management positions; hence, women were less engaged in the decision-making process. The negligence or under-representation of women at the executive level is still considered problematic. The intellectual capital of administrators and academics is being eliminated at a time when higher education is facing a serious challenge in an extremely competitive market. Women possess the potential to be transformative leaders in higher education institutions (HEI). Noticeably, in the Webometrics search group’s findings about the country, world, excellence and impact ranking of HEI in Lebanon, the highest ranked institutions were noticeably the ones who had achieved an approximate balance of both gender engagements at the Dean’s level post. The research purpose was to show that some Lebanese educational institutions still practice inequality and prefer men over women in their executive positions, as well as show that excellence in educational institutions is linked to women being in these executive positions. Currently, the higher education sector in Lebanon is under development, as numerous educational developments are being implemented. The problem is that a peculiar attitude toward women in the HEI sector and specifically at the top management level still exists. In this mixed study, reviewing the literature, the Webmetrics worldwide data group and interviewing 12 chairpersons from different schools, the author explored women’s engagement at the top management levels of higher education and found that only 15 out of 65 Dean’s positions were filled by women and aimed to discover the factors behind the misrepresentation of women within the higher education system in Lebanon. In addition, the study found a positive relationship between the presence of women and the performance of HEIs. In this study, I aimed to focus on women’s engagement at the top management level and to emphasize the advantages of their skills and expertise, as well as enhancing the presence of women. The findings were significant and clear: There was misrepresentation, bias and stereotyping in HEIs. A clear strategic plan is needed to engage women in the decision-making process along with a well-designed incentive plan to achieve the required purpose. The aim of this study was to highlight this matter and to accentuate the benefit of women’s leadership roles in higher education in Lebanon. A mixed methods strategy using primary information was obtained from interviews with 12 chairpersons of six different schools. Data were gathered and analyzed to provide insightful results and recommendations.

1. Introduction

The term “glass ceiling” goes back to the 1980s, which referred to the existence of barriers that were impeding qualified women. Elmer (2015), in a report about women at top management levels, stated that organizations cited a variety of barriers to the advancement and development of women, including “lingering bias and career paths that do not lead to promotions.” Later, countries such as France, Norway and Germany set quotas to reach a fair presence of women. Now, advocates argue and strive to put women in charge, and they consider hiring women in leadership positions to be not just the right thing, but indeed the smart thing to do.

The absence of women’s engagement in any educational change in Lebanon is apparent, regardless of their qualifications. The literature shows that future organizations might suit women to a greater degree (Colwill and Townsend 1999); in spite of this, the presence of women in leadership positions is still limited. Women’s leadership styles and characteristics are distinct from those of men; nevertheless, institutions are not taking advantage of this diverse leadership opportunity.

The aim of this paper was to explore the situation of women in the higher education sector of Lebanon, to investigate this problem and get a clearer perspective of the sector, and to find the factors that were most affecting women’s presence at top management levels. The main research questions were as follows: Are women fairly represented in HEI top management positions or not? Why? Is there a relationship between the excellence of Lebanese institutions and the presence of women?

2. Literature Review

The mission of higher education is to provide extensive knowledge, insight and innovation, all of which are the heart of a successful society. Nevertheless, the fact remains that women are highly represented here, although they are non-existent at the executive levels. Embracing Jhon Stacey Adma’s equity theory, which states that employees strive for equity between themselves and other workers; firstly in order to be initially motivated, then to be productive and satisfied. Equity becomes achievable when the ratio of (male and female) employees’ outcomes over inputs is equal (Adams 1965). Hejase et al. (2013), in their study exploring female leadership in Lebanon, found that women still encounter a variety of obstacles in their careers, and the authors refer these obstacles to male stereotyping and discrimination. Moreover, the authors uncovered that in cases where women succeeded in reaching managerial positions, they became further subjected to continuance comparisons with their male counterparts regardless of their skills. Researchers have so far focused on technology, curricula, and students in online learning; however, few have examined faculty and administration performance or equity.

The researcher’s assumption is that HEIs still prevent women from proceeding to higher decision-making levels. These institutions’ agendas do not include “gender balance” nor take advantage of the abilities and skills of women, despite their major role and enormous development in many other sectors. Speaking globally, and regardless of the fact that getting more women onto corporate boards of directors has been attracting more attention lately, the percentage of female directors appointed to Fortune 500 boards seats declined by 2% in 2016, ending the trend of the last seven years of growth (Heidrick & Struggle 2017).

2.1. Gender Leadership

Leadership is the art and science of influencing people to perform and assign tasks willingly and effectively (Hughes et al. 2015). The practice has proven that leadership skills and abilities have improved employees’ job satisfaction and engagement, which eventually will lead to productivity. Leadership in education requires analyzing students’ requirements, observing classes and pinpointing certain potential problems, building effective teams and changing organizational structures, as well as designing, implementing and working towards reforming and improving education. Additionally, Swaffield and MacBeath (2013) initiated the “leadership for learning” (LFL) approach which focuses on the improvement of students’ learning outcomes rather than the traditional approach that focuses on making educational resources available to students. The LFL learning model is an outcomes-focused model for education, where the needs of students come first in learning. This model considers that teachers’ leadership education, through mentoring, will prioritize, improve and fulfill students’ learning needs. Nevertheless, leaders should communicate with educators, staff, families, and students. Relationship building is essential for effective educational leadership.

2.2. Leadership Styles

Leadership styles and traits are numerous, including honesty, trust and creativity, and building on these features will create great leadership. Leadership perspectives have evolved and changed over time. Until modern history, the traditional concept of the leader was a “great man”, a charismatic, heroic, and successful person who would be successful regardless of the context (Birnbaum 1989). In the past two decades, researchers have been altering how they study and see leadership. Kezar et al. (2006) state that “Moving away from stable, highly organized and neutral values, contemporary scientists have embraced dynamic, globalized and action-oriented views that emphasize intercultural understanding, cooperation and social responsibility for others.”

Leadership emphasize group work, cooperation, empowerment, support, participation and hierarchy. However, scientists recognize that effective leadership has historically been seen in constant and persistent masculine modes (Eagly and Wood 2013). According to Folkman and Zenger (2015), differences between males and females exist physically, perceptually, rationally and emotionally.

In this study, the author has looked at the overall leadership effectiveness by age between both genders, with a large sample used in this study, a statistical significance that cannot occur by chance was found. These findings indicated that women leaders appear to change with time, and a small difference in the careers of women was realized, wherein men seemed to perceive and surpass the women. On the other hand, and at a later stage, the researcher stated that as women mature, they perceive a positive and quick improvement, which allows them to be effective. In addition, the author realized that the gap between both genders’ effectiveness diverges until the age of 60 (Folkman and Zenger 2015). In other words, it appears that women extend their time or “take their time to improve.”

This study has found that the factor behind women’s lower leadership effectiveness was the deliberate development in comparison to men’s effectiveness. Nevertheless, women by nature are responsible for many aspects in their life and that surpasses men in their responsibilities, which are numerous: Women give birth, raise and prepare their children for life, and despite the help and cooperation of men, women still prioritize their house and family. Eventually, this will affect their career development, and their leadership effectiveness, as a matter of fact, it is delayed until later on. These two gender-based styles exist in the contemporary understanding of gender leadership literature.

As Eagly and Johannesen-Schmidt (2001, pp. 3–5) have pointed out, some researchers have shown that there are considerations for the behavior of female and male leaders. Thus, this is also linked to beliefs attributed to female and masculine attitudes and values. Female and male leadership styles have always been introduced in contradictory directions in this part of the research. We can quote a large number of authors who have portrayed gender differences in leadership styles.

Eagles and Bates (1990, p. 233) refer to Luden, who dealt with the two directions and acknowledged the existence of a “masculine mode of management by qualities such as competitiveness, hierarchical authority, high control for the leader, and unemotional and analytic problem solving.” The feminine way of leading, he described as “Cooperativeness, collaboration of managers and subordinates, lower control for the leader, and problem solving based on intuition and empathy as well as rationality.” Therefore, the focus should move to the next level, which is the development of new educational strategies that optimize learning and focus on identifying and solving educational problems.

With regard to the behavior of leaders, according to Eagles and Bates (1990, p. 236), the first contradictions between the two styles were based on the criterion of sex by Bales in 1950. According to Bales, the “interpersonally-oriented style” describes women leaders and a “task-oriented style” relates to men. Similarly, Eagly and Johannesen-Schmidt (2001, p. 10) emphasize the differences identified by many authors, saying male leaders are “organizing task-relevant activities.” With regard to the “interpersonally-oriented style”, the authors understood this “as a concern with maintaining interpersonal relationships by tending to others’ morale and welfare.” They acknowledge that these differences may be related to common beliefs about female and masculine characteristics.

The authors recognize a strong link between transformational and female leadership patterns, which are part of the concept of gender leadership. Empirical studies based mainly on specific questionnaires showed that women leaders are classified as most transformed by their subordinates.

Several studies have shown that women leaders adopt more of a transformational leadership style than men. Bass (1997) conducted a study between a sample of intermediate and higher directors, and “they found that female managers were rated as more transformational than male managers by both male and female subordinates” (Bass 1997, p. 211). They also refer to a study led by Duskat in 1994 within the Roman Catholic Church where subordinates classified their superior women as surrogate and transformational. All these examples linked transformational leadership to women’s leadership, mainly because of the “Societal qualities” and “Democratic style” used by women leaders. Many studies have shown that women attribute their success and sometimes their struggles to the fact that they always have to do twice the work to get recognized (Folkman and Zenger 2015; Twale and De Luca 2008; Eagly and Wood 2013).

2.3. Lebanese Higher Education System

The Lebanese higher education system has experienced numerous changes, and many are still needed. Education managers from Arab countries have struggled to develop systems for higher education (Samoff 2003; UNESCO 2003). Moreover, these education managers from specified countries were permitted to build educational systems to grow their societies and help them to flourish. In a short time, the education leaders from Arab countries, and significantly Lebanon, have rapidly established a greater number of universities (UNESCO 2003, as cited in Mohamed (2005)). It should be noted that higher education institutions have noticed a remarkable increase in enrollment because of the growing public demand for education, in addition to the enlarged population and governmental commitment to make higher education more available.

The Ministry of Education and Higher Education governs Lebanese higher education. HEIs counted around 199,679 students in 2016, or 45% of the total national enrollments. The gross enrollment for ages 20 to 24 was 30%. Two types of educational institutions exist that provide higher education: The public Lebanese University (LU) and the private universities. The LU has its own regulations and an independent structure (Khalaf 2007). The private sector follows the main law issued in 1961, whereby a council for HEI was initiated via licensing.

All universities have at least one campus, usually starting operations within the capital of Beirut; however, after significant enrollment and funding, they started gradually operating outside the capital in different Lebanese regions. Branches are managed by academic staff and are directly related to the main campus (Saleh 2008). Leaders of HEIs usually follow and adopt their own quality standards, with some of these institutions acquiring accreditation by external educational organizations from the United States and Europe (Saleh 2008). The leaders of regional and international organizations have mentioned the aforementioned educational problem. In a 2008 report by the Education Reforms in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), noted that a consideration for changing the alternatives of education development in the region existed (MENA 2008). The report emphasized the need to change the educational system. The staff described HEIs as institutions that should prepare students for the contemporary world, with issues ranging from globalization to technology developments.

2.4. Dean and Academic Director Positions in Higher Institutions

A key point in this study was the dean’s positions in higher education, which were used to measure the gender balance in HEIs. The dean’s position can go beyond strategic planning, budgeting, the curriculum and research to be a key participant in the external relations of the university, franchising, alumni relations, economic development, political and public relations, as well as hiring capable academic chairs, directors, and staff and engaging in a key discussion of the institutional planning. The fundamental role of the dean is to support and promote the highest quality of the university’s educational programs. In addition to this, the dean is the one responsible for collegiate planning, educational plans, research, and activities. The dean’s competency includes creating a high-quality working environment. He or she has a key role-playing in program review and accreditation. The dean’s position is central in developing and improving the mission of the educational institution, and it has been considered that the dean’s position is the chief role for higher education.

In addition, the review was conducted regarding the chief academic officers or provost positions and found that there were no women in these positions. The provost, sometimes called the chancellor, has responsibility for planning, development, and administration for both the educational programs and services. The provost ensures integrity and supports innovation in the university. He or she provides leadership, vision, and direction to meet educational goals. Moreover, the provost brings or forwards on recommendations concerning cooperative ventures and communication. He or she participates in the organizational strategic planning, policy formulation, decisions and problem solving and provides advice. While the vice president has a major function, which is recommending to the president the appointment of deans and associate deans, both positions are considered the ultimate authority in interpreting the academic rule and regulations of the university. As for the women who held both positions, there were no female provosts or vice presidents in all 30 institutions.

2.5. Higher Institution Ranking Comparison

Reviewing the literature, interesting data was obtained from Webometrics, a ranking database that focuses on worldwide universities and is an initiative of the Cybermetrics Lab, a research group belonging to the Consejo Superior de Investigacions Cientificas (CSIC), distributed throughout Spain. CSIC is among the largest public research bodies in Spain. In 2006, the CSIC consisted of 126 centers and institutes distributed throughout Spain. The main objective of the CSIC is to collaborate with other Spanish institutions, R&D systems, social, economic, national and foreign agents to promote scientific research in order to improve the educational level of the country, which contributes to increasing the welfare of the citizens.

3. Methodology

The problem is that women are still under-represented in higher education institutions, and the main questions were the following: Are women fairly represented in HEIs’ top management positions or not? Why?

Is there a relationship between institutional excellence and the presence of women? It was assumed that the delay of higher education was related to the misrepresentation of women. However, according to the Webometrics group data, a worldwide information system that observes educational institutions around the world, Lebanese institutions were ranked as ensuring gender balance and positioned higher than those who totally ignored women’s representation in their top management positions. Using the pragmatic research approach, a mixed of qualitative and qualitative instruments helped answer the main questions of this study as stated above. The interview and questionnaire instruments were used to explore the opinions and attitudes of participants on gender balance and obtain subjective data from faculties.

In addition to the percentages derived from the questionnaire, the numerical data provided by the Webometrics reports, along with the data collected from 30 institutions on the number of women appointed to the dean position, were used to test the relationship between excellence and the presence of women.

The reason behind choosing the dean’s position was that this position encounters unlimited and diverse tasks and responsibilities, both administrative and academic. The dean’s role varies depending on the college or the school, yet this role is vital, and it can affect the organization from a holistic perspective. Thus, testing the presence of women at this position was essential to exploring the presence of women in this sector.

A review of the literature, scholarly written articles, books and other relevant sources related to the area of research and a critical evaluation in relation to the research problem was performed. Second, primary information was used from a questionnaire that was distributed to a convenient sample of 30 faculty members to explore their insights about women’s representation. In addition, 12 interviews were conducted with chairpersons from 6 different schools to investigate the factors behind the impediment of women’s representation.

The questionnaires were distributed to 30 instructors using the random sampling type, and the interview method was applied to 12 chairpersons from different schools as a means of collecting information that was common and useful. Both instruments allowed the researcher to obtain detailed information. As Gray (2004) stated, many reasons exist for the use of interviews to collect data; for example, interviews provide personalized data. As an opportunity to investigate the case of HEIs in Lebanon, interviews were used to allow the participants the opportunity to get involved and discuss their views freely (Cohen et al. 2000). In this way, data was collected and new knowledge could be gained from the participants. Moreover, the interchange of knowledge and views improved the research data. Consent was included in the questionnaire that ensured confidentiality, besides obtaining institutional approval to conduct the surveys and interviews.

In this study paper, the intention was to use multiple resources, questionnaires, literature, interviews and a public research group. Patton (2012) agreed on triangulation as a way to strengthen the study, which happens by combining many methods. Triangulation is used in qualitative research to establish validity by analyzing the central question from different perspectives. The goal of triangulation is to get consistency across data sources (Patton 2012). At the time of data collection, the participants of the present study were faculty members, with different backgrounds and experiences.

4. Analysis and Findings

The main question was the following: Are women fairly represented in HEI top management positions or not? Why? Is there a relationship between the excellence of an institution and the presence of women?

The questionnaire’s findings were as follows: 92% of participants (from both genders) agreed that there was an imbalance of women in leadership roles. The findings also indicated that 89% of participants considered that men held more senior positions than women. Moreover, 87% of faculty and administration felt deprived when asked about their feelings toward the organization’s efforts to achieve an equal balance of men and women at senior level positions. When asked about the importance of development programs for women leaders, the majority showed interest. A shocking finding was that most of the participants did not see a strategy in place to develop women leaders. In addition, when asked about the competencies that would be most valuable for the organization to focus on when creating women’s leadership development, work-life balance scored the highest.

As for the interview, two of the interviewees addressed this concern, saying “In order to get the same recognition and rewards, I need to do twice the work, never make a mistake and constantly demonstrate my competence.” In addition, “We must perform twice as well to be thought half as good.” This absolutely matched the literature review, which showed that women attributed their success and sometimes their struggles to the fact they always have to do twice the work to get recognized (Folkman and Zenger 2015; Twale and De Luca 2008; Eagly and Wood 2013).

In addition to the qualitative findings, the investigation of the presence of women in the dean’s position at the Lebanese HEIs by sourcing the latest organizational structure available from each institution showed that, from 30 institutions with a total of 163 dean’s positions, only 34 were women. It was shown that out of 65 dean’s positions in 30 private institutions, there were only 15 women who held the dean’s position (see Table 1). It should be noted that at middle and lower management levels there was no gap between men and women. Besides this, the academic director positions were entirely filled by males.

Table 1.

Webometrics Ranking/Women Presence.

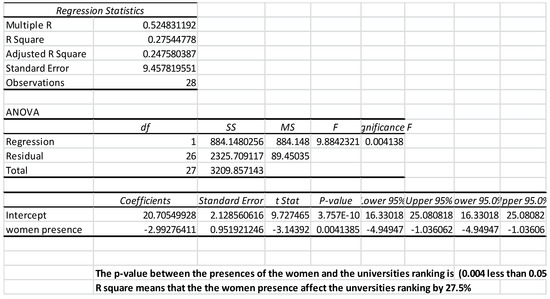

Using the Webometrics search group findings about the country, world, excellence and impact ranking of HEIs in Lebanon (Table 1), the highest ranked institutions were noticeably the ones who had achieved an approximate balance of both genders’ engagement at the dean’s level post, such as the American University of Beirut, Lebanese University and Arab University. Using the five top-ranked institutions and running a correlation between excellence and the presence of women, a significant positive correlation was found. In other words, the top-five ranked institutions were the ones who had engaged women at their senior management levels, and specifically at the dean’s position. Thus, the author has established that there is a basic relationship between HE institutions’ quality improvement and the institutions’ policies toward embracing women’s engagement (Figure 1). Indeed, more data is needed and in-depth studies are required in order to confirm this correlation.

Figure 1.

Regression Test.

5. Conclusions and Recommendation

The findings were clear: There is an insufficient presence of women in senior executive positions. However, things are slowly changing: The rate of women in senior executive positions has increased over the past decade. Efforts by public institutions to promote equity have been made within organizations. Even if the situation develops slowly, the rate of women in senior executive positions increases each year. Women’s organizations in Lebanon have a long history of struggle towards gender equality. Perceptions concerning the achievements and status of women in Lebanese society suggests relative progress on issues related to rights and gender equality. The problem is a gender imbalance in the HEIs, and the answer to the main question of this study about whether there is fair representation in HEIs’ top management positions was a definite no. In addition, according to the interviewee and questionnaire participants, women always need to do double the work to get recognized.

As for the relationship between the excellence of Lebanese institutions and the presence of women, running a regression test between the ranking derived from the Webmetrics data base and the data retrieved from the 30 institutions structure provided online, a significant correlation between institutional excellence and the presence of women was found.

It is apparent that HEIs require a major adjustment in their strategy toward women’s presence and engagement within the roles of organizational leadership. The literature has shown the importance of women’s roles, and worldwide pressure has been established to take the required actions. As mentioned in the introduction, the Lebanese higher education sector encounters major competition locally and internationally, and the only way to stay competitive is to provide a clear strategy based upon gender equilibrium. The leaders of regional and international organizations have mentioned the aforementioned educational problems. A significant and clear gender gap, bias, occupational choices, and working conditions nonetheless remain in the educational sector. A clear strategic plan is needed to engage women in the decision-making process along with a well-designed incentive plan to achieve the required equality.

The presence of women is a competitive advantage for the educational sector. A strong action plan is needed in both the public and private sector to remove the persistent inequality in education, with the commitment and contribution of all organizational and educational members with responsibility. Determining career progression experiences and challenges that women face in major research institutions could greatly benefit the next generation of women. Finally, future research might consider conducting more studies similar to the present study, perhaps in a four-year private research higher education institution to determine the experiences and challenges faced by women in such an institution.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Adams, J. Stacy. 1965. Inequality in Social Exchange in Advances in Experimental Psychology. Edited by L. Berkowitz. New York: Academic Press, pp. 267–99. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, Bernard M. 1997. Does the transactional-transformational leadership paradigm transcend organizational and national boundaries? American Psychologist 52: 130–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birnbaum, Robert. 1989. The implicit leadership theories of college and university presidents. The Review of Higher Education 12: 125–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Louis, Lawrence Manion, and Keith Morrison. 2000. Research Methods in Education. London: Routledge Falmer. [Google Scholar]

- Colwill, Jenni, and Jill Townsend. 1999. Women, leadership and information technology: The impact of women leaders in organizations and their role in integrating information technology with corporate strategy. Journal of Management Development 18: 207–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagles, E. H., and Johnson Bates. 1990. Gender and Leadership Style: A Meta-Analysis University of Conneticut. p. 233. Available online: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1010&context=chip (accessed on 12 September 2018).

- Eagly, Alice H., and Mary C. Johannesen-Schmidt. 2001. The leadership styles of men and women. Journal of Social Issues 57: 781–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, Alice H., and Wendy Wood. 2013. The nature-nurture debate: 25 years of challenges in the psychology of gender. Perspectives on Psychological Science 8: 340–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elmer, Vickie. 2015. Women in Top Management. Available online: http://businessresearcher.sagepub.com/sbr-1645-95535-2666211/20150427/women (accessed on 12 September 2018).

- Folkman, Joseph, and Jack Zenger. 2015. Why Women Are More Effective Leaders Than Men. Harvard Business Review, March 15. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, David E. 2004. Doing Research in the Real World. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Heidrick & Struggle. 2017. Board Diversity at an Impasse? Board Monitor 2017, Knowledge Center. Heidrick & Struggle. Available online: http://www.flcc.edu/pdf/hr/provost-job-description.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2018).

- Hejase, Hussin, Ziad Haddad, Bassam Hamdar, Rasha Massoud, and George Farha. 2013. Female Leadership: An exploratory Research from Lebanon. Available online: Researchgate.net (accessed on 12 September 2018).

- Hughes, Richard L., Robert Ginnett, and Gordon Curphy. 2015. Leadership: Enhancing the Lesson of Experience. New York: Mc Graw-Hill Education. [Google Scholar]

- Kezar, Adrianna, Rozana Carducci, and Melissa Contreras-McGavin. 2006. Rethinking the “l” Word in Higher Education: The Revolution of Research on Leadership. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Khalaf, Malek Khalil. 2007. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Education in Lebanon. Beirut: American University of Beirut. [Google Scholar]

- MENA (Middle East and North Africa). 2008. The Road not Travelled. Education Reforms in the Middle East and North Africa. Available online: http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTMENA/Resources/EDU_Flagship_Full_ENG (accessed on 4 December 2018).

- Mohamed, Amel. 2005. Distance higher education in the Arab Region: The need for quality assurance frameworks. Online Journal for Distance Learning Administration Content 8: 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, Michael Quinn. 2012. Essentials of Utilization-Focused Evaluation. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Saleh, Hanadi Kassem. 2008. Computer self-efficacy of university faculty in Lebanon. Educational Technology Research and Development 56: 229–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samoff, Joel. 2003. Institutionalizing international influence. Safundi: The Journal of South African and American Comparative Studies 4: 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaffield, Sue, and John MacBeath. 2013. Leadership for learning. In Leading Professional Practice in Education. Edited by Christine Wise, Marion Cartwright, Pete Bradshaw and M. Cartwright. London: Sage, pp. 9–24. [Google Scholar]

- Twale, Darla, and Barbara M. De Luca. 2008. Faculty Incivility: The Rise of the Academic Bully Culture and What to Do about It. New York: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO (The United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization). 2003. Higher Education in the Arab Region 1998–2003, Meeting of Higher Education Partners. Paper presented at UNESCO Regional Bureau for Education in the Arab States, Paris, France, June 23–25; Available online: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0013/001303/130341e.pdf (accessed on 4 December 2018).

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).