Abstract

The issue of women’s participation in top management and boardroom positions has received increasing attention in the academic literature and the press. However, the pace of advancement for women managers and directors continues to be slow and uneven. The novel framework of this study organizes the factors at the individual, organizational and public policy level that affect both career persistence and the advancement of women in top management positions; namely, factors affecting (1) career persistence (staying at the organization) and (2) career advancement or mobility (getting promoted within the organization). In the study location, Chile, only 32 percent of women “persist”, or have a career without interruptions, mainly due to issues with work–family integration and organizational environments with opaque and challenging working conditions. Women who “advanced” in their professional careers represent 30 percent of high management positions in the public sector and 18 percent in the private sector. Only 3 percent of general managers in Chile are women. Women in Chile have limited access and are still not integrated into business power networks. Our findings will enlighten business leaders and public policy-makers interested in designing organizations that retain and promote talented women in top positions.

1. Introduction

In the last decade, talent management of women has become a priority in the agendas of countries, companies and social organizations. Many women are among the half of the active workforce with a college degree. However, this level of representation is not replicated in top management or director-level positions around the globe, as well as in Latin America (Abramo 2004; Zehnder 2016; PwC 2016). As a consequence, the growth potential of companies and countries that do not take advantage of the talents and education of their whole population is reduced.

With the purpose of preventing this loss of female talent and its collaboration to social and economic development, some governments have implemented practices and policies to increase women’s participation in senior management. One of these decisions was especially disruptive: In 2008, Norway introduced a quota of 40 percent female participation in the boards of directors of publicly traded, cooperative societies and municipal enterprises.

Even though this norm met great opposition, the results obtained by the law have been quite positive so far. In his book, Aaron Dhir (2012) explains that democratization of board of directors in Norway improved decision making and governing board management culture. More precisely, he discovered that the incorporation of 40 percent women generated improvements in the process of decision-making, in prevention of the effects of groupthink, decrease of risk, an increment in the collective intelligence of government boards; it also forces the search and exploitation of women with talent to contribute to the business world in different networks, beyond the traditional corporate power network or the “old boys” (McDonald 2011).

Because of these results, many European countries have imitated or adapted this measure to their national reality. Norway’s case was a trigger for new research and a reinterpretation of the role of women in corporate senior management, and of the causes that hindered their ascent to senior management positions.

It is precisely this new context that encouraged the realization of a study exploring all the academic and professional literature on women in senior management generated since 2009. Salvaj and Kuschel’s work (Salvaj and Kuschel forthcoming) is based on a comprehensive study of the latest literature on the subject of women in top management. The first objective of their review was to open the “black box” that encloses all the factors that block the road to top management positions for women and visualize each one. From this starting point, their second objective was to map or organize these factors so women and organizations interested in the development of female talent can evaluate their weaknesses and strengths regarding each factor and focus on the design and implementation of concrete actions for the professional development and promotion of women in senior management. We will briefly describe the framework in the next section and then apply it to the Chilean context to reveal practical ways to increase women’s participation at the top levels of management (see also the executive report in Supplementary Materials).

2. Framework for Women’s Career Success

According to the recent literature review on empirical articles (published from 2009 to 2016) that supported this model, the reasons for the lack of participation of women in senior management are associated with complex and deeply-rooted aspects (Salvaj and Kuschel forthcoming).

2.1. Professional Success as Both Career Persistence and Career Advancement

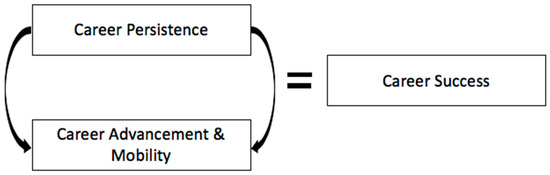

Academic evidence regarding women in senior management indicate that professional success is associated with two actions: persistence and advancement. Women who are successful in their professional lives are those who persist, i.e., do not interrupt their career and/or advance, i.e., are promoted (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Components of women’s professional success. Source: Salvaj and Kuschel (forthcoming).

2.2. Challenge 1: Persistence

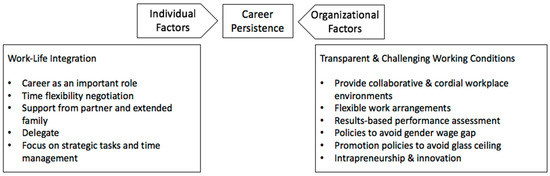

A vast group of researchers has focused on understanding the factors that allow women to persist, or avoid interrupting their professional development. Persistence1 is especially relevant for the case of women who aspire to occupy positions in senior management, since they (in contrast with men) tend to face more challenges from hostile male organizational environments (Stamarski and Hing 2015; White and Massiha 2016); extended and rigid office schedules (Goldin 2014; Griffiths and Moore 2010); difficulties in integrating family and work life, which frequently drive them to prematurely interrupt or abandon their professional careers (Kossek et al. 2016), even when they are very talented and have great potential for promotion or advancement towards senior management positions (Hewlett and Rashid 2010). Academic papers show that those women in management positions that interrupt their professional activities experience great difficulty returning to the workforce in similar positions to those they held before the interruption, and that many never manage to achieve the same level in terms of position and remuneration (Kulich et al. 2011).

From an individual perspective, women need to set career as a primary—not secondary—domain (Sandberg 2013). Seth (2014) suggested that being career-driven is not a crime and encouraged women to ask for support from their partners and extended family, hire help, delegate both at work and at home, and either reframe the old job or find a part-time job. These strategies allow women to better manage their time and focus on strategic tasks.

From an organizational point of view, the solution might be to redefine job structures and remuneration so they do not punish flexibility (Goldin 2014) to avoid providing an organizationally hostile environment (White and Massiha 2016); to provide performance evaluation systems that are perceived as gender-inclusive (Festing et al. 2015); to avoid a gender pay gap (Blau and Kahn 2000; Hejase and Dah 2014); and to create a clear path for women to advance (Grant Thornton 2015). Finally, organizations can remove barriers and provide a more flexible and inclusive culture by providing intrapreneurial opportunities (i.e., corporate entrepreneurial ventures) for women (Mattis 2000, 2004). These are the organizational factors that need to be considered if organizations seek to retain talent. The individual and organizational factors affecting persistence are synthesized in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Factors that impact persistence and retention of women in senior management. Source: Salvaj and Kuschel (forthcoming).

2.3. Challenge 2: Advancement and Promotion

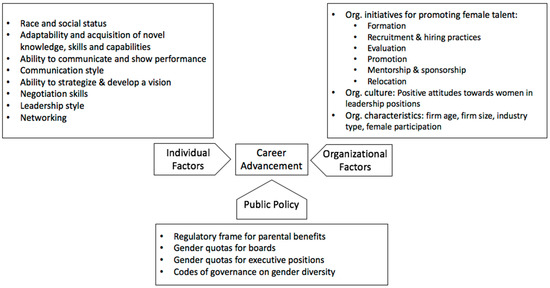

A second, larger group of studies have explored the factors that impact the professional advancement of women, i.e., their promotion towards managing positions of greater responsibility. According to the framework, there are factors or causes common to the persistence and advancement and other that are inherent to each of these components of women’s professional success. Researchers working in this second group have been more prolific, not only in the number of studies, but also in the listing of factors: individual, organizational, and public policy (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Factors that facilitate the advancement and promotion of female talent toward senior management. Source: Salvaj and Kuschel (forthcoming).

At an individual level, performance and skills are of course critical to advance in organizations. While the literature highlights the technical/business ability to strategize and develop a vision (Appelbaum et al. 2013), most of the skills typically required from those at the top are “soft skills”, such as adaptability and acquisition of novel knowledge, skills and capabilities (Ellemers et al. 2012); communication of performance (Grant and Taylor 2014; Ibarra and Obodaru 2009; Ibarra and Sackley 2011); leadership (Sheaffer et al. 2011); negotiation (Hawley 2014); and networking skills (Brands and Kilduff 2014).

At an organizational level, the culture (generally reinforced by the supervisor), size and industry of the firm all matter, because the presence of a woman on a top management team reduces the likelihood that another woman occupies a position on that team (Dezső et al. 2016). Firms can advance women’s careers by implementing diverse formal and informal organizational initiatives, from inclusive hiring practices to providing mentorship. Governments can provide the regulatory framework that can accelerate the cultural change in the attitudes towards women in senior positions.

In these two challenges, the same notions apply: (1) the factors affecting women’s success in senior management interact with each other (e.g., as stated by Ibarra (1993), culture and context affects network structure, as well as networking skills or individuals’ network development approaches or strategies for managing constraints); (2) each individual must understand how they perform or are assessed in their particular case; and (3) the importance of each of these factors and their relationships with each other are dynamic, i.e., they change constantly, so analyses of the ways in which these factors influence professional advancement must be reviewed periodically.

Persistence and advancement in professional life are related to and feed from each other. Women who persist in their careers have better chances of achieving advancements, but once these are achieved, the challenges and demands of an executive position with greater responsibility increase the difficulty of remaining in the professional career. Thus, persistence is a necessary condition to advance, and while women progress in their profession, persistence become harder. This is demonstrated by the decreasing percentage of women—in all industries—as they climb the organizational pyramid.

3. Results: The Framework Applied to the Chilean Case

3.1. Female Participation in Higher Education and Job Market

Currently in Chile, more than half of graduates from Chilean universities are women (52%), which demonstrates a high education level comparable to that of men (GET Report 2016). However, women tend to access careers with lower social rating, which could affect their legitimacy and status in their professional advancement. Eighty-seven percent of women who have a master’s degree work, very close to the 89 percent of men. Additionally, it is estimated that 48.5 percent of women participate in the Chilean workforce (GET Report 2016).

Alarmingly, however, only 32 percent of women have a continuous career (CASEN 2013). This speaks of a low level of persistence in their professional careers because of temporary or permanent leaves. This, in part, explains why female talent only sit on and hold (approximately) 5 percent of boards2 and 10 percent of senior management positions, according to Tokman (2011).3 A recent report from the Chilean Civil Service in 2016 indicates that the percentage of positions occupied by women in public senior management reached 30 percent, while the corresponding rate in the private sector was only 18 percent.4

These values indicate that in Chile, the incorporation of women in positions of senior management is still low compared to other countries of the OECD, and even other countries in Latin America. It is worth mentioning, though, that the indicators have improved in the last few years, and that there is an important dynamism due to government commitment and the activism of organizations of women in senior management positions.

3.2. Individual Factors and Women in Senior Management Positions

Academic or professional research on the individual factors that facilitate persistence and advancement of women in senior management in Chile is exceedingly scarce. Table 1 presents a summary of the relevant existing research on the factors that affect women’s success in senior management. This paper seeks to provide impetus for further research by showing the lack and inviting researchers to investigate each of the factors identified here.

Table 1.

Summary of research on the factors that affect women’s success in senior management.

In Chile, accessing positions in organizational leadership depends (greatly) on trust relationships with stakeholders. Salvaj and Lluch (2016) described that, up until the 90s, female chairwomen were associated with the family or controlling group of the company, and that in the last 10 years, this tendency has changed; even though “family chairwomen” are still an important percentage, “professional chairwomen” make up more than 50 percent of women on the boards of the 125 biggest companies in the country. They also analyzed the contact networks of women in managing positions; the results showed that, in addition to being a minority, multiple chairwomen (or those who sit on more than one board) tend to be less common than their male counterparts. Only 30 percent of chairwomen participated in two or more boards, while 40 percent of chairmen were members of at least 2 boards. Additionally, in 2010 and 2013, no chairwoman appeared in the top ten of better-connected chairpeople linked to the board network. In essence, Salvaj and Lluch’s results suggest that, first, chairwomen represent a minority at the top levels of company management; and second, chairwomen have smaller networks or lower social capital than chairmen. Another interesting datum from that study is that the three women on the greatest number of boards in Chile in 2010 and 2013 were foreigners. The most popular chairwomen were from English-speaking countries or Colombia, and they were associated with regulated concessions and public services companies with foreign participation. They attained the chair position through their international networks, which allows us to state that none of the local or foreign women serving as chairpeople were completely integrated into the male networks, where the power is Chile is concentrated.

As described in a report made by the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) on female leadership in Chile (Gabaldón 2015), another relevant aspect is the quantity and dynamism of executive women’s networks which seek to make visible the problem of female participation in senior management positions and to support women in executive positions. These studies have yet to analyze the effectiveness of said gender associations in reference to their capacity to ease access to senior management positions.

3.3. Organizational Factors and Women in Senior Management Positions

Similar to the subject of individual aspects, there is a dearth of research papers that explore the organizational factors that affect the management of female talent in senior management in Chile (see Table 1). We only identified reports from government agencies, consultancy firms and international organisms that describe the current situation of gender inequality.

Most of the previous studies have concentrated around the topic of corporate social responsibility (CSR), human resources best practices, and time flexibility at work (Chinchilla et al. 2017). Arguments have been made for flexibility as a route to more sustainable human development in Chilean society, but it carries the risk of becoming a burden for women if it is defined as a benefit just for them. Although flexible organizational policy (telework, part-time work, etc.) does not make firms sustainable, we acknowledge that it is a good way to start to change; it definitely moves the agenda forward to improve women’s participation in the workforce. The gender equality and work-life balance certification for companies (NCh3262), Great Place to Work, and PROhumana foundation have been pushing this agenda forward.

New research is emerging to fill gaps. The ESE Business School is studying the profile of women in leadership positions in Chile (Bosch 2017; Bosch and Riumalló 2017a) and the impact of quotas (Bosch and Riumalló 2017b). Even in light of an “equal pay for equal work” law enacted in Chile (Law 20.348 of 20095), the pay gap between men and women with the same responsibilities is still a reality in all the levels of organizations and in all job categories. It was still on the order of about 30 percent in the higher salary ranks as of 2015, according to estimates by the Dirección de Trabajo del Gobierno de Chile (Directorate of Labor of the Chilean Government) (Dirección del Trabajo 2015). According to the OECD (2018) the gender pay gap between individuals with higher education is 35 percent (OECD average is 26 percent), leaving Chile in 37th place, i.e., last among the OECD countries. In the Chilean public administration, the gender pay gap is 10.4 percent (ILO 2017). Law 20.348 of 2009 for equal remuneration for work of equal value has had little effect, and the rate of official complaints of differences in salary to the Directorate of Labor of the Chilean Government has been low.

In addition to the existence of an important wage gap, Chile also presents low indicators of female participation in senior management. Women in senior management make up only around 6 percent of working women (cf. the OECD average, 20 percent). Women occupy 6 percent of CEO positions, and approximately 12 percent in service management sector. In total, around 22 percent of management positions are held by women. Nevertheless, 36.6 percent of corporate governments still have no female participation (GET Report 2016).

The proportion of women on the boards of the most important companies (IPSA or Top 100 by size) is also very low. The ratio of female representation is never reported as higher than 8 percent (in 2018 it was 6.4 percent: 21 women in the 327 IPSA board of director positions). The report by Egon Zehnder (2016) based on a sample of publicly held companies revealed that approximately half the boards of companies of the IPSA have at least one woman on their board; this could be perceived as progress, but it is far from a perfect situation: These companies may be adopting the strategy of “tokenism”. The concept of tokenism refers to the policy and practice of making a superficial gesture towards the inclusion of members of underprivileged or minority groups (King et al. 2010; Oakley 2000). In this context, an effort to include women on the board usually has the intention of creating the appearance of gender diversity, thereby deflecting accusations of discrimination.

Despite these low indicators, currently, there are no publicly held companies in Chile that have implemented programs or special policies to promote women to management positions (Zehnder 2016). This is in contrast with the cases of Argentina or Colombia, where 43 and 38 percent of companies (respectively) indicate they implement practices to develop female talent for promotion to senior management (Zehnder 2016). The lack of policies in the private sector6 to ease or support the arrival of women to senior management is in line with Gabaldón’s (2015) report on the opinion of Chilean businessmen who were inclined toward the voluntary and progressive option of women in senior management, but did not define how they would exploit this process.

3.4. Public Policy Initiatives

There is also a dearth of research papers that explore the effectiveness of and ways in which public policy initiatives affect the management of female talent in senior management in Chile (Table 1). We only identify reports that describe the actions undertaken by the government and the prevailing situation of gender inequality.

The government of Chile has an explicit commitment to the advancement of women in senior management. Demonstrating this commitment, they set up the creation of a Ministerio de la Mujer y Equidad de Género (Ministry of Women and Gender Equality) as well as the Primer Plan de Acción de Responsabilidad Social 2015–2018 (First Action Plan of Social Responsibility 2015–2018) which incorporated concrete measures for the incorporation of gender dimension in companies according to the guidelines of the OECD.

In this framework, and with the objective of leading by example, an initiative that establishes a quota or goal for participation of women in the boards of Empresas del Sistema de Empresas Públicas (SEP) (Companies in the System of Public Companies) of 40 percent—as was done in several European countries (as described by Heemskerk and Fennema 2014) and as proposed by the norms of the EU—is being pushed. In 2015, the percentage reached 29.3 percent in SEP, while in non-SEP public companies, women’s participation reached 25 percent (Pulso 2016).

Additionally, the Superintendency of Securities and Insurance (Superintendencia de Valores y Seguros—SVS) adopted measures (norm 386) that demand transparency regarding the number of women sitting on private companies’ boards (SVS 2015). Among the changes to corporate government norms are the incorporation of data on the following aspects: diversity on the board (gender, nationality, age and seniority); diversity in general management and other managements that report to this management or to the board; diversity in the organization (gender, nationality, age, seniority); and pay gap by gender. Norm 385 also calls for firms to publicly report the adoption of the aforementioned policies to the diversity of the composition of the board and in the designation of the main executives of the society.

Finally, there is a developed regulatory framework related to gender in Chile. Exceptionally, and leading among American countries, Chile contemplated the “Law of Parental leave of 6 months”, in force since 2011. Law 20.545 of 20117 modifies the norms on maternity protection and incorporates parent post-birth leave and allows Chilean mothers (and later fathers) to increase the time to be spent with newborn children. During this extension of 12 weeks (for a total of 24), mothers receive a maternity subsidy, financed by the State, which covers their remuneration during this time, for a maximum of 66 UF8 monthly. Some companies cover the difference so leave pay matches the salary of women in executive positions with a greater salary. Normally, medium-sized organizations have explicit organization policy regarding how the rest should be covered. In smaller companies, this is open to negotiation between the employee and the employer.

4. Conclusions

This article highlights and integrates the most important factors that affect (allow or hinder) the persistence and advancement of women in top management positions. We map such factors with the intention of providing a practical guide for people interested in managing women’s managerial talent within organizations; the factors are presented at the individual, organizational and institutional or government level.

The literature has shown that poor performance is not the reason women do not persist or advance in their professional careers, since companies with female executives in senior management positions present, in general, better financial results (Hoobler et al. 2018; Terjesen et al. 2016).

The real factors that would explain the success (or lack thereof) of women on their road to senior management are associated with aspects intrinsic to culture. Culture can change to take advantage of the value provided by female talent. However, all cultural changes require leaders who inspire and allow the advancement of women and can modify the application of policies and practices that aim to close gender gap as well as affirmative actions from both organizations and the government.

4.1. The Model as a Guide of Self-Assesment

This map of factors that impact women’s professional development aims to help in self-evaluation (both on the personal and organizational level), identify aspects that could be obstructing female talent development, and aid in the development of design strategies for improvement. It is important to point out that the factors identified here are not all equally relevant in a specific moment, and that for each situation, the combination of factors that explain the difficulty to persist or move forward in professional development is different.

Organizations interested in managing their female talent can self-evaluate and identify the reasons why women leave their jobs prematurely or do not advance professionally. There are diverse organizational factors that affect the retention and promotion of female talent in each company. Therefore, it falls to women individually, as well as to individual organizations, to identify what factors have the greatest impact in each case, and to design practices or policies from the results of this analysis.

4.2. Future Research Opportunities

The existing research gaps in the literature on women’s careers in Chile are highlighted in Table 1. Most of the relevant literature regarding Chile addresses the organizational level; there is a huge opportunity to explore the individual factors affecting women’s ability to persist and advance in Chilean organizations, and make women’s voice visible with more qualitative studies (Undurraga 2013).

Future academic research should close the gap of our understanding on the disadvantages women face at the entry level—especially with the introduction of (a) the gender equality and work-life balance certificate (NCh3262); (b) gender quotas for boards of directors; (c) the future law for universal access to early childhood education, and (d) retirement—with the future modification of retirement age.

It would be useful to address how specific contexts might affect women’s development within organizations. For example, how women design their careers in STEM, and homosocial, i.e., male-dominated industries (Amon 2017; Holgersson 2013); what barriers women face when leading their own high-growth ventures (Kuschel and Labra 2018); how certain leadership perceptions have evolved over time (Appelbaum et al. 2013); and awareness of how situational factors such as tokenism (King et al. 2010) or the “glass cliff” phenomenon (Bruckmüller and Branscombe 2010) can artificially increase women’s participation in senior positions.

4.3. Recommendations for the Chilean Actors

For the case of Chile, it is important to point out that the government is not the only actor that can help reduce gender gap in company leadership. Companies, through concrete actions and practices, play a fundamental role in addressing the current situation. This study shows dynamism in the public sector as well as organizations for women executives. Such efforts are not perceived to be made by companies, perhaps because of a lack of documentation. The lack of management of female talent is depicted in the lack of policies in large companies that ease the arrival of women in senior management would indicate a passive and uninterested position in generating change.

To achieve a greater ratio of women who persist, changes must be made in two directions: (1) facilitation of women’s work–life integration; and (2) generation of challenging and interesting environments for them. Without women who persist in an organization, especially in mid-level and high-level positions, women will not be able to reach senior management positions or serve on boards.

Female talent management, necessary to increase economic and social development, must be understood as a process that starts the moment a woman enters a company and continues throughout her work life. Due to factors that affect the development of female talent at the individual, organizational and government levels, multiple actors must coordinate and contribute to this process.

Supplementary Materials

Executive Report (in Spanish: Abriendo la “caja negra”: Factores que impactan en la travesía de las mujeres hacia la alta dirección) available online at http://www.redmad.cl/images/estudios/estudio13.pdf.

Author Contributions

K.K. and E.S. contributed to the design and implementation of the research, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of the results and to the writing of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Red Mujeres para la Alta Dirección (Women Top Executives Network) in Chile. http://www.redmad.cl/.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Abramo, Laís. 2004. ¿Inserción laboral de las mujeres en América Latina: Una fuerza de trabajo secundaria? Revista Estudos Feministas 12: 224–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amon, Mary J. 2017. Looking through the glass ceiling: A qualitative study of STEM women’s career narratives. Frontiers in Psychology 8: 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Appelbaum, Steven H., Barbara T. Shapiro, Katherine Didus, Tanya Luongo, and Bethsabeth Paz. 2013. Upward mobility for women managers: Styles and perceptions: Part two. Industrial & Commercial Training 45: 110–18. [Google Scholar]

- Blau, Francine D., and Lawrence M. Kahn. 2000. Gender Differences in Pay. Journal of Economic Perspectives 14: 75–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, María Jose. 2017. Women in management in Chile. In Women in Management Worldwide: Signs of Progress. Edited by Ronald J. Burke and Astrid M. Richardsen. New York: Routledge, pp. 249–67. [Google Scholar]

- Bosch, María-José, and María-Paz Riumalló. 2017a. Liderazgo Femenino. Santiago: Cuaderno ESE. [Google Scholar]

- Bosch, María-José, and María-Paz Riumalló. 2017b. Ley de Cuota. Santiago: Cuaderno ESE. [Google Scholar]

- Bosch, María José, Carlos J. García Toledo, Marta Manríquez, and Gabriel Valenzuela. 2018. Macroeconomía y conciliación familiar: El impacto económico de los jardines infantiles. El Trimestre Económico 85: 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brands, Raina A., and Martin Kilduff. 2014. Just like a woman? Effects of gender-biased perceptions of friendship network brokerage on attributions and performance. Organization Science 25: 1530–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruckmüller, Susanne, and Nyla R. Branscombe. 2010. The glass cliff: When and why women are selected as leaders in crisis contexts. Social Pscychology 49: 433–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CASEN. 2013. Encuesta de Caracterización Socioeconómica Nacional; Santiago: Ministerio de Desarrollo Social.

- Chinchilla, Nuria, Mireia Las Heras, María-José Bosch, and María-Paz Riumalló. 2017. Responsabilidad Familiar Corporativa. Estudio IFREI Chile. Santiago: ESE. [Google Scholar]

- Dezső, Cristian L., David Gaddis Ross, and José Uribe. 2016. Is there an implicit quota on women in top management? A large-sample statistical analysis. Strategic Management Journal 37: 98–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhir, Aaron. 2012. Challenging Boardroom Homogeneity. Corporate Law, Governance, and Diversity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dirección del Trabajo. 2015. La desigualdad salarial entre hombres y mujeres. Alcances y limitaciones de la Ley Nº 20.328 para avanzar en justicia de género. Available online: http://www.dt.gob.cl/portal/1629/articles-105461_recurso_1.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2018).

- Ellemers, Naomi, Floor Rink, Belle Derks, and Michelle K. Ryan. 2012. Women in high places: When and why promoting women into top positions can harm them individually or as a group (and how to prevent this). Research in Organizational Behavior 32: 163–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festing, Marion, Lena Knappert, and Angela Kornau. 2015. Gender-Specific Preferences in Global Performance Management: An Empirical Study of Male and Female Managers in a Multinational Context. Human Resource Management 54: 55–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabaldón, Patricia. 2015. Chile. Liderazgo Femenino en el Sector Privado. Washington, DC: Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo. [Google Scholar]

- GET Report. 2016. Gender, Education and Labor. A Persistent Gap. Santiago: Comunidad Mujer. [Google Scholar]

- Goldin, Claudia. 2014. A Grand Gender Convergence: Its Last Chapter. American Economic Review 104: 1091–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, Anett D., and Amanda Taylor. 2014. Communication essentials for female executives to develop leadership presence: Getting beyond the barriers of understating accomplishment. Business Horizons 57: 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant Thornton. 2015. Mujeres directivas: En el camino hacia la alta dirección. London: Grant Thornton International Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, Marie, and Karenza Moore. 2010. Disappearing Women: A Study on Women Who Walked Away from their ICT Careers. Journal of Technology Management and Innovation 5: 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawley, Stacey. 2014. Rise to the Top: How Woman Leverage Their Professional Persona to Earn More and Rise to the Top. Pompton Plains: Career Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heemskerk, Eelke M., and Meindert Fennema. 2014. Women on bard: Female board membership as a form of elite democratization. Enterprise and Society 15: 252–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hejase, Ale, and Abdallah Dah. 2014. An Assessment of the Impact of Sticky Floors and Glass Ceilings in Lebanon. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences 109: 954–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewlett, Sylvia Ann, and Ripa Rashid. 2010. The Battle for Female Talent in Emerging Markets. Harvard Business Review 88: 101–8. [Google Scholar]

- Holgersson, Charlotte. 2013. Recruiting Managing Directors: Doing Homosociality. Gender, Work & Organization 20: 454–66. [Google Scholar]

- Hoobler, Jenny M., Courtney R. Masterson, Stella M. Nkomo, and Eric J. Michel. 2018. The business case for women leaders: Meta-analysis, research critique, and path forward. Journal of Management 44: 2473–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarra, Herminia. 1993. Personal Networks of Women and Minorities in Management: A Conceptual Framework. The Academy of Management Review 18: 56–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarra, Herminia, and Otilia Obodaru. 2009. Women and the vision thing. Harvard Business Review 87: 62–70, 117. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ibarra, Herminia, and Nicole Sackley. 2011. Charlotte Beers at Ogilvy & Mather Worldwide (A). Case Study. Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- ILO. 2017. Chile: Acortando las brechas de la desigualdad salarial en el sector público. Available online: http://www.ilo.org/santiago/sala-de-prensa/WCMS_555061/lang--es/index.htm (accessed on 20 October 2018).

- Kelly, Ciara, Chidiebere Ogbonnaya, and María-José Bosch. 2018. Integrating FSSB with flexibility I-deals: The role of context and domain-related outcomes. Academy of Management Proceedings 2018: 11722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, Eden B., Michelle R. Hebl, Jennifer M. George, and Sharon F. Matusik. 2010. Understanding tokenism: Antecedents and consequences of a psychological climate of gender inequity. Journal of Management 36: 482–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossek, Ellen Ernst, Rong Su, and Lusi Wu. 2016. “Opting Out” or “Pushed Out”? Integrating Perspectives on Women’s Career Equality for Gender Inclusion and Interventions. Journal of Management 20: 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulich, Clara, Grzegorz Trojanowski, Michelle K. Ryan, S. Alexander Haslam, and Luc Renneboog. 2011. Who gets the carrot and who gets the stick? Evidence of gender disparities in executive remuneration. Strategic Management Journal 32: 301–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuschel, Katherina, and Juan-Pablo Labra. 2018. Developing Entrepreneurial Identity among Start-ups’ Female Founders in High-Tech: Policy Implications from the Chilean Case. In A Research Agenda for Women and Entrepreneurship: Identity through Aspirations, Behaviors, and Confidence. Edited by P. G. Greene and C. G. Brush. Boston: Edward Elgar, pp. 27–44. [Google Scholar]

- Las Heras, Mireia, María-José Bosch, and Anneloes M. L. Raes. 2015. Sequential mediation among family friendly culture and outcomes. Journal of Business Research 68: 2366–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattis, Mary C. 2000. Women entrepreneurs in the United States. In Women in Management: Current Research Issues. Edited by M. J. Davidson and R. J. Burke. Thousand Oaks: Sage, vol. II, pp. 53–68. [Google Scholar]

- Mattis, Mary C. 2004. Women entrepreneurs: Out from under the glass ceiling. Women in Management Review 19: 154–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, Steve. 2011. What’s in the “old boys” network? Accessing social capital in gendered and racialized networks. Social Networks 33: 317–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakley, Judith G. 2000. Gender-based barriers to senior management positions: Understanding the scarcity of female CEOs. Journal of Business Ethics 27: 321–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. 2018. Education at a Glance 2018. OECD: Available online: http://www.oecd.org/education/education-at-a-glance/ (accessed on 20 October 2018).

- Pezoa, Alvaro, María-Paz Riumalló, and Karin Becker. 2011. Conciliación Familia-Trabajo en Chile. Santiago: ESE Business School y Grupo Security. [Google Scholar]

- Pulso. 2016. Presencia femenina en directorios de empresas públicas bordeó el 30% en 2015. Date 2016-02-11. Available online: http://www.pulso.cl/economia-dinero/presencia-femenina-en-directorios-de-empresas-publicas-bordeo-el-30-en-2015/ (accessed on 20 October 2018).

- PwC. 2016. International Women’s Day: PwC Women in Work Index. London: PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP. [Google Scholar]

- Salvaj, Erica, and Katherina Kuschel. Forthcoming. Opening the ‘black box’. Factors affecting women’s journey to senior management positions. A literature review. In The New Ideal Worker: Organizations between Work-Life Balance, Women and Leadership. Edited by Mireia Las Heras, Nuria Chinchilla and Marc Grau. Barcelona: IESE Publishing.

- Salvaj, Erica, and Andrea Lluch. 2016. Women and corporate power: A historical and comparative study in Argentina and Chile (1901–2010). Paper presented at LAEMOS 2016, Viña del Mar, Chile, April 6–9. [Google Scholar]

- Sandberg, Sheryl. 2013. Lean in: Women, Work, and the Will to Lead. New York: Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Seth, Reva. 2014. The Momshift: Women Share Their Stories of Career Success after Having Children. Toronto: Random House Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Sheaffer, Zachary, Ronit Bogler, and Samuel Sarfaty. 2011. Leadership attributes, masculinity and risk taking as predictors of crisis proneness. Gender in Management: An International Journal 26: 163–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamarski, Cailin Susan, and Leanne S. Son Hing. 2015. Gender inequalities in the workplace: The effects of organizational structures, processes, practices, and decision makers’ sexism. Frontiers in Psychology 6: 1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SVS. 2015. Norma de carácter general Nº 386. Available online: http://www.cmfchile.cl/normativa/ncg_386_2015.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2018).

- Taser Erdogan, Didem, Maria Jose Bosch, Jakob Stollberger, Yasin Rofcanin, and Mireya Las Heras. 2018. Family motivation of supervisors: Exploring the impact on subordinate work performance. Academy of Management Proceedings 2018: 10750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terjesen, Siri, Eduardo Barbosa Couto, and Paulo Morais Francisco. 2016. Does the presence of independent and female directors impact firm performance? A multi-country study of board diversity. Journal of Management & Governance 20: 447–83. [Google Scholar]

- Tokman, Andrea. 2011. Mujeres en puestos de responsabilidad empresarial. Gobierno: Servicio Nacional de la Mujer. [Google Scholar]

- Undurraga, Rosario. 2013. Mujer y trabajo en Chile: ¿qué dicen las mujeres sobre su participación en el mercado laboral? In Desigualdad en Chile: La continua relevancia del género. Edited by C. Mora. Santiago: Ediciones Universidad Alberto Hurtado, pp. 113–41. [Google Scholar]

- Undurraga, Rosario, and Emmanuelle Barozet. 2015. Pratiques de recrutement et formes de discrimination des femmes diplômées—le cas du Chili. L’Ordinaire des Amériques. 219. Available online: http://journals.openedition.org/orda/2357 (accessed on 20 October 2018).

- White, Jeffry L., and G. H. Massiha. 2016. The retention of Women in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics: A framework for persistence. International Journal of Evaluation and Research in Education 5: 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zehnder, Egon. 2016. 2016 Egon Zehnder Latin American Board Diversity Analysis. Zurich: Egon Zehnder International, Inc. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | When assessing the obstacles to persistence that women face in their professional lives, we find that only 32 percent of women manage to continue, uninterrupted, in the work market, according to data from Casen Survey 2013, Chile. |

| 2 | This value varies according to the sample size analyzed by the different studies. The most pessimistic are around 3 percent, while optimistic values are closer to 8 percent. |

| 3 | |

| 4 | |

| 5 | Equal remuneration for work of equal value (Law 20.348 of 2009) available at: https://www.leychile.cl/Navegar?idNorma=1003601. |

| 6 | This observation is based in the non-existence of research that provide precise data on practices and policies in the private sector. However, it is worth mentioning that, from our experience, we know that there are some companies implementing CSR practices, family-friendly organizational culture, networking programs and non-discriminatory HR practices. Some examples are Movistar, BCI and Grupo Security. There are also programs to equalize female representation in senior management positions in multinational companies with branches in Chile, e.g., Adidas Chile. |

| 7 | Modifies the norms on maternity protection and incorporates parental leave (Law 20.545 of 2011) available at: https://www.leychile.cl/Navegar?idNorma=1030936. |

| 8 | UF stands for Unidad de Fomento, a unit of account used in Chile. The exchange rate between the UF and the Chilean peso is constantly adjusted for inflation (http://www.hacienda.cl/glosario/uf.html) so that the value of the Unidad de Fomento remains constant on a daily basis during low inflation. 1 UF = 39.92 USD (18 October 2018). |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).